Abstract

Root cause analysis (RCA) identifies the faults and vulnerabilities underlying software failures, informing better design and maintenance decisions. Earlier approaches typically framed RCA as a classification task, predicting coarse categories of root causes. With recent advances in large language models (LLMs), RCA can be treated as a generative task that produces natural language explanations of faults. We introduce RCEGen, a framework that leverages state-of-the-art open-source LLMs to generate root cause explanations (RCEs) directly from bug reports. Using 298 reports, we evaluated five LLMs in conjunction with human developers and LLM judges across three key aspects: correctness, clarity, and reasoning depth. Qwen2.5-Coder-Instruct achieved the strongest performance (correctness ≈ 0.89, clarity ≈ 0.88, reasoning ≈ 0.65, overall ≈ 0.79), and RCEs exhibited high semantic fidelity (CodeBERTScore ≈ 0.98) to developer-written references despite low lexical overlap. The results demonstrated that LLMs achieve high accuracy in root cause identification from bug report titles and descriptions, particularly when reports contained error logs and reproduction steps.

1. Introduction

Developers begin the debugging process of resolving an issue by identifying the root cause. Root cause analysis (RCA) provides a structured approach to addressing this fundamental aspect of software defect resolution. RCA is the method of identifying the underlying cause of the defects or faults from bug reports [1]. It is an essential step toward identifying and resolving software defects during the Software Development Lifecycle [2,3]. Bug reports contain evidence of failure and provide sufficient context for fault localization and corrective changes [4]. Typically, developers attempt to identify the underlying cause of an issue from bug reports.

Root cause analysis is performed before a developer delves into bug resolution [5]. Typical RCA is manual, tedious, and time-consuming for developers. The manual RCA relies heavily on the expertise of the assigned developer and often falls short in terms of accuracy and efficiency due to the increasing volume of bugs in large-scale software systems. Bug reports are issued by end users who typically lack the technical expertise and insights about software defects, which sometimes makes bug reports harder for developers to interpret [6]. Additionally, developers are responsible for specific components of the system and possess varying levels of programming and domain expertise, which makes it challenging for a particular developer [7] to scrutinize all kinds of bugs and be aware of all aspects of a software system. Thus, manual RCA is slow and impedes development efforts, which usually introduce more bug triaging and delays software maintenance [8]. Automated bug root cause analysis can accelerate the RCA process by reducing the need for manual intervention from developers, thus making the RCA faster and more accurate by saving many development hours.

Researchers have conducted several studies on different approaches to automating bug root cause analysis [9,10,11,12,13]. Different approaches, such as supervised machine learning, deep learning, and various ensemble techniques, have been studied, where RCA is formulated as a classification task [10,11], in which broad categories of root causes are identified. The categories are often limited in expressing the actual underlying cause of the bugs, and introduce ambiguity in identifying the root causes. Sometimes, developers need to perform manual inspections to dispel the ambiguity. Bug root causes, localization, and fixes vary widely across bug reports [14], which makes coarse automated RCA outputs inadequate for effective bug resolution by developers. We advocate for a per-report approach to provide a detailed and specific root cause, enabling precise developer actionability. Therefore, we reframe automated RCA as a generative task to produce context-specific root-cause identification that better facilitates bug resolution.

This study investigates the application of LLMs for the automated analysis of software bug reports. We propose a novel root cause analysis framework that can automatically analyze and generate Root Cause Explanations (RCEs) based on the provided bug report as input. The proposed framework leverages state-of-the-art open-source LLMs to scrutinize bug report metadata and produce an actionable RCE. Our study addresses three major research questions, as stated below.

RQ1: To what extent is RCEGen effective at producing correct, clear, and actionable root causes, and which LLM performs best?

With this RQ, we aim to evaluate the effectiveness of the root cause explanations generated by the RCEGen framework and determine which LLM yields the most acceptable results. Since bug reports often combine code and natural language, we compare multiple LLMs to determine which one produces the most accurate and useful explanations for developers.

RQ2: To what extent are independent LLM judges reliable when scoring RCE quality (correctness, clarity, and depth of reasoning)?

With this RQ, we assess the reliability of automated evaluation by measuring inter-rater agreement among LLM judges. We evaluate how consistently different LLMs rate the quality of root cause explanations across three dimensions: correctness, clarity, and depth of reasoning, which helps establish the trustworthiness of automated judgments of explanation quality.

RQ3: To what extent do RCEGen’s explanations align with developer-authored root-cause analyses?

With this RQ, we want to validate the practical utility of our framework by comparing automated explanations against real developer analyses. We engage human experts with strong programming backgrounds to evaluate LLM-generated explanations, using developer-provided root cause analyses as ground truth to measure alignment and identify areas for improvement.

RQ4: To what extent does the quality of a bug report’s title and description impact RCEGen’s accuracy in finding root causes?

With this RQ, we want to understand whether bug report metadata alone provides sufficient context for accurate root cause identification. We analyze how variations in title and description quality affect the RCEGen framework’s performance, investigating whether these summary elements contain enough information for LLMs to identify underlying problems without additional developer input. The main contributions of the paper are below:

- RCEGen: A novel LLM-based framework for generating evidence-grounded root cause explanations (RCEs) from bug reports.

- Comparative evaluation: A systematic comparison of multiple state-of-the-art LLMs using unified zero-shot prompting.

- LLM-as-Judge evaluation framework: A ranking-based scoring system that assesses RCE quality using Correctness, Clarity, and Depth of Reasoning metrics validated through inter-rater agreement analysis.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews relevant literature, Section 3 describes the methodology including dataset preparation and selection of LLMs, Section 4 outlines the experimental setup, prompt engineering and execution, Section 5 presents the results, Section 6 discusses the findings, Section 7 examines the threats to validity, Section 8 discusses limitations, Section 9 outlines future work, and Section 10 concludes.

2. Related Work

In software defect identification and bug resolution, bug reports play a vital role as both a communication channel between end users and developers and as a historical record of issues, symptoms, and resolutions. Developers analyze these reports to identify the underlying causes of defects during the root cause analysis (RCA) phase. Many researchers leverage bug reports from sources such as GitHub Issues and open-source bug repositories in automated RCA studies because of their richness and importance. This section outlines two aspects of related research and highlights the gaps between existing studies and our work.

2.1. Automated RCA as a Classification Problem with Supervised and Deep Learning Approaches

Prior studies have conceptualized automated bug root cause analysis as a classification problem using bug reports as the primary data source. Ferdin et al. [15] undertook one of the earliest studies in this field by proposing a classical ML approach using a Support Vector Machine (SVM) to predict three case-based root cause categories: “Null Check Not Performed”, “Exception Not Thrown”, and “Method Not Called”. They utilized historical bug reports along with fixed code changes’ DiffCat [16] as training features. Lal et al. [9] applied a semi-supervised machine learning technique, Label Propagation, to predict root cause categories such as configuration errors, incorrect implementations, and misuse of interfaces. Zhen et al. [17] conducted bug root cause analysis using a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) with Bayesian Learning and SVM to classify the historically fixed bugs into equivalent bug causes. The authors manually investigated 2000 historical fixed bugs and labeled them into six cause categories following orthogonal defect classification criteria [18]. They utilized lexical code tokens and types with AST-level structures [19], which were vectorized using the TBCNN vector representation method for model training. Their proposed model only predicts semantic defects. Thomas et al. [11] classified bug reports using multiple supervised learning algorithms, including Multinomial Naive Bayes (MNB), Linear SVM (LSVC), SGD-based Linear SVM (SGDC), Random Forest (RFC), and Logistic Regression (LRC). However, their approach is slightly different as they incorporated bug reports with bug-fixed code AST diff using Gumtree [20] for the training set with manual labeling of 18 sub-categories from previous studies [10,14,21].

Hafiza et al. [22] developed the CaPBug framework that can categorize bug reports automatically into a constant set of six categories using NLP and performed comparative analysis of four supervised machine learning algorithms, Naive Bayes (NB), Random Forest (RF), Decision Tree (DT), and Logistic Regression (LR). The categories are optimized toward bug prioritization. Nadia et al. [23] used ML models to classify security-oriented issues and apply the SMOTE technique to balance the dataset. Another study [12] applied an ensemble machine learning-based classifier to predict the nature of bugs from bug reports from a fixed set of bug natures, which is not applicable if the model encounters a new category of bug. Other studies [24,25,26] have explored RCA as an unsupervised learning approach to categorize root causes using Hierarchical Dirichlet Processes (HDP) and Expectation-Maximization (EM) clustering algorithms to discover patterns in bug reports without prior knowledge. Nevertheless, the resultant categories represent generic terms from bug titles rather than the primitive causes [25]. Prior studies primarily rely on historical bug reports to predict root cause categories, where issues have already been resolved and the root cause can be identified from fixed code, commit messages, and bug report discussions. In contrast, our study focuses on unsolved bug reports, which are more aligned with the real needs of software development.

2.2. Automated RCA Through Large Language Models (LLMs)

Most studies in this field have conceptualized bug root cause analysis as classification tasks with a very specific set of coarse-grained root causes as categories [27]. While such categories can be helpful for developers, they often still require manual inspection, and constructing large training datasets for classical ML models is infeasible due to the need for manual annotation [10,21]. In contrast, recent advances in large language models (LLMs) open the possibility of approaching root cause analysis as a generative task, finding fine-grained and specific causes without limiting them to predefined categories [28].

In recent years, large language models (LLMs) have been widely applied to software engineering tasks, such as code summarization, program repair, and test case generation [14,29,30]. Still, their potential for automated root cause analysis (RCA) remains largely unexplored. Laura et al. [31] studied the feasibility of LLMs like ChatGPT (version 3.5) in elucidating bug reports and generating bug-reproducing test cases, where 50% of the generated test cases were executable and 30% of them were valid bug-reproducible tests where they applied zero-shot prompting on the popular Defect4J dataset. Bangmeng et al. [32] proposed SumLLaMA, an LLM-based approach for automated bug summarization using CodeLLaMA with fine-tuning strategies using Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA). The calculated metrics (BLEU and ROUGE-L) represent word-to-word comparison with the LLM-generated summary and user-reported bug title, which does not reveal the bug cause in most cases. Xuchao et al. [33] applied vanilla GPT-4 with an in-context learning approach to experiment with production incident logs, where they summarized the root cause in a behavioral format for customers, which did not address the software developer perspective. Xiaoting et al. [34] experimented with a Pre-trained Language Model (PLM) GPT to comprehend bug reports and predict bug types for bug reports from three deep learning frameworks, including TensorFlow, MXNet, and PaddlePaddle. Their study indicated the F-measure range of predictions obtained through GPT-4 falls between 53.12% and 58.39%. However, the bug types are generalized based on fault activation and/or error propagation conditions: the Bohrbug (BOH), an aging-related bug (ARB), and a non-aging-related bug (NAM), as well as specific bugs related to deep learning frameworks. Abished et al. [35] experimented from a unique perspective of utilizing LLMs as evaluators for bug report summarization, and GPT-4o indicated promising results as an evaluator. While earlier work explored test-case generation and summarization from bug reports, which is encouraging, it does not directly focus on automated root-cause analysis. Our study seeks to bridge this gap by introducing a novel RCA framework that leverages large language models (LLMs).

3. Methodology

3.1. RCEGen Framework Overview

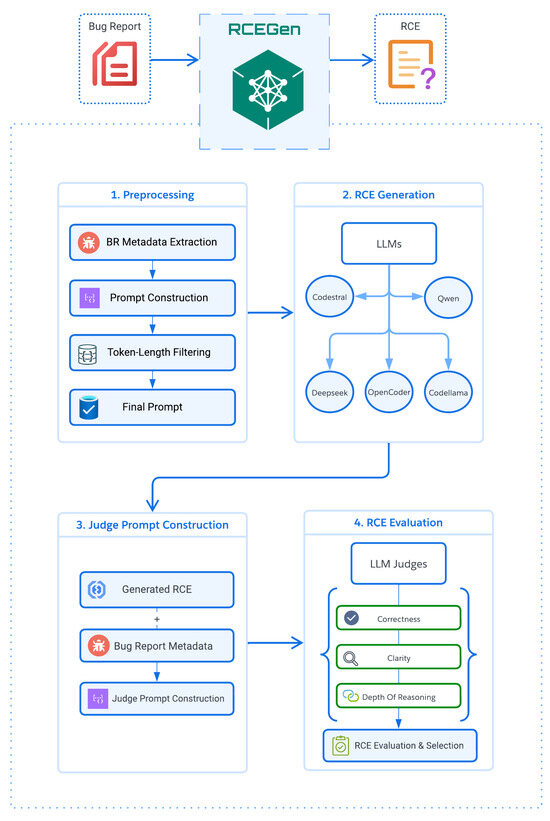

Figure 1 outlines the stages RCEGen framework which comprises four major phases: Pre-processing, RCE generation, Judge prompt construction and RCE evaluation.

Figure 1.

The high-level architecture of the RCEGen framework.

In the pre-processing phase, we extract key metadata from each bug report and use it to build an initial prompt tailored for code explanation tasks. During the root cause explanation (RCE) generation step, the prompt is passed as-is to a set of LLMs, and each model returns its explanation of what caused the bug. For every explanation received, we construct a judge prompt by combining the original bug report with the generated explanation, creating a kind of peer-review setup where a second LLM evaluates the quality of the reasoning. In the final evaluation phase, two powerful evaluator models: GPT-4o and DeepSeek-V3 assess each explanation based on the criteria outlined in the RCEGen framework. The scores are then aggregated to rank the performance of the generator models for each bug report. Ultimately, the explanation with the highest quality score is selected and presented to the developer as the result of the automated root cause analysis.

3.2. Pre-Processing Phase

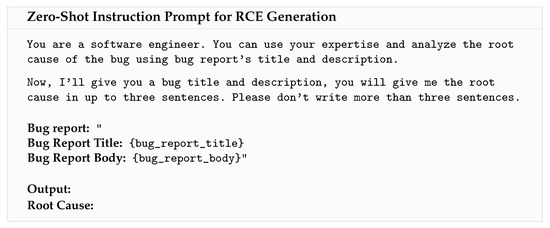

We started by pre-processing a received bug report, where each report includes a title and a description and any embedded stack trace. Following best practice for zero-shot instructional prompting, we adopt a single template that frames the task to identify the most probable root cause. A sample prompt used for generating root cause explanations is illustrated in Figure 2. Since the selected LLMs have input length limits and our hardware had its own constraints, we had to filter out any reports whose prompts turned out too long to feed into a particular LLM. As detailed in Section 3.1, we kept only those that were concise but still carried enough context to be meaningful, favoring quality content over bulk since longer bug reports are not inherently better [6]. After this process, we ended up with a clean set of metadata, paired with a prompt ready to be evaluated by the models. To make this practical, we enforced a conservative token budget: among our selected models, one has an 8192-token context window, so we targeted inputs where the concatenated title + body was ≤3000 tokens for that model; during inference we also observed occasional echoing of the input (e.g., reproducing snippets or traces) before the three-sentence summary, which could push the running context beyond 5000 tokens. Because context-window limits are hard constraints and because smaller-capacity models tend to hallucinate when fed very long inputs we excluded longer reports, especially those dominated by large stack traces or verbose logs, and prioritized high-signal fields (titles, steps to reproduce, error messages) to keep prompts within budget and maintain grounded outputs.

Figure 2.

A simple Instruction Prompt Template to ask the model to act like a software engineer and, using the bug’s title and description, state the root cause in up to three sentences.

3.3. RCE Generation

For the RCE Generation phase, we selected five models based on their performance on the EvalPlus leaderboard [36], with a particular focus on the rankings that use HumanEval as the benchmark. We chose four instruction-tuned code models that ranked highly and had parameter sizes below 35 billion, intentionally avoiding smaller variants of much larger models. Our goal was to evaluate models where the largest available version falls within our computational constraints. We also aimed to avoid selecting earlier or overlapping versions of the same model family to minimize redundancy. For instance, since we included Qwen2.5-Coder-Instruct, we did not include CodeQwen1.5-7B-Chat, as it represents an earlier iteration of the Qwen code models.

In addition to these, we included the well-known CodeLlama-34B model due to its strong performance and popularity in code generation, opting not to use the 70B variant because of hardware limitations.

3.3.1. Qwen 2.5 Coder 32B Instruct

Qwen2.5-Coder-32B-Instruct [37] is the largest instruction-tuned model in the Qwen2.5-Coder family. Trained on a vast mix of code, natural language, and synthetic data, it excels at tasks like code generation and bug fixing across 40 programming languages. It supports long context window and performs competitively with top proprietary models like GPT-4o on major benchmarks.

3.3.2. DeepSeek Coder 33B Instruct

DeepSeek-Coder-33B-Instruct [38] is a large code generation model designed to understand and follow prompts effectively. Trained on a massive mix of code and natural language, it handles tasks like code completion and bug fixing with ease. Its long context window and fill-in-the-blank training make it especially useful for working with large codebases.

3.3.3. Codestral 22B

Codestral-22B-v0.1 [39], developed by Mistral AI, is a strong open-source model for code generation. Trained on a wide range of programming languages, it handles tasks like code completion, test generation, and infilling with ease. It is trained on dataset spanning 80+ languages and has a long context window.

3.3.4. CodeLlama 34B Instruct

CodeLlama-34B-Instruct [40] is Meta’s instruction-tuned model built for a variety of code tasks like generation, completion, and infilling. Part of the Code Llama family, it’s especially strong in Python and designed to follow natural language instructions effectively. Based on the same foundation as Llama-2, it handles long context inputs and performs well on coding benchmarks like HumanEval and MBPP.

3.3.5. OpenCoder 8B Instruct

OpenCoder-8B-Instruct [41], developed by Infly, is an instruction-tuned model built for code generation in both English and Chinese. Trained on a large mix of code and instructions, it performs well on benchmarks like HumanEval and MBPP.

3.4. Prompt Template Design

We kept our prompt design simple, using a zero-shot template that included only the bug report’s title and description, with no additional context or examples. This straightforward approach mirrors how people typically ask questions to LLMs in everyday situations.

The exact template we used is shown in Figure 2. It begins with a brief role assignment: ”You are a software engineer”, so that the model interprets the task from a developer’s perspective. The prompt then asks the model to analyze the given bug report and provide the root cause in up to three sentences. We explicitly restrict the response length to ensure concise and focused reasoning, making the outputs more comparable across models. The placeholders {bug_report_title} and {bug_report_body} are dynamically replaced with the respective fields from each report during evaluation.

This design achieves a balance between structure and generality. The short and direct instruction helps the model understand what is expected while avoiding unnecessary prompt complexity. Keeping the template minimal is also important in practice, since many open-source models have limited input length and some bug reports can be quite long. Using longer prompts often leads to truncated inputs or increases the risk of hallucination, so a compact template helps maintain reliable and grounded reasoning.

We deliberately avoided few-shot examples, reasoning chains, or additional context to maintain a clean and reproducible setup. This allows us to evaluate each model’s intrinsic ability to interpret and reason about bug reports without the influence of external cues or handcrafted demonstrations.

Figure 2 illustrates the overall format used in all our experiments. The consistent structure across all inputs made it easier to analyze how different models interpret identical bug information under identical prompting conditions. Overall, this simple zero-shot template provides a transparent and controlled baseline for measuring LLMs’ ability to understand and reason about bug reports in realistic settings.

3.5. RCE Evaluation

The RCE Evaluation phase consists of two important steps: assessing the root cause explanation produced by the generation phase, and second, selecting the highest-scoring RCE for each bug report based on different evaluation criteria.

3.5.1. LLM Judge Model Selection

We selected our evaluator LLMs based on a combination of benchmarking results and task-specific performance. GPT-4o was chosen for its strong alignment with human judgments in recent “LLM-as-judge” benchmarks, its proven effectiveness in code-related tasks, and its large 128K token context window—ideal for handling both bug reports and candidate explanations. For the second evaluator, we selected DeepSeek-V3 not strictly based on the initial selection criteria, but because of its superior performance on SWE-benchmarks. Together, GPT-4o and DeepSeek-V3 offer complementary strengths, helping to reduce single-model bias and produce robust, cross-validated evaluation scores.

GPT-4o: OpenAI’s latest flagship model combines advanced natural-language reasoning with solid code comprehension, achieving around 67% pass@1 on HumanEval [42]. Its 128K token context and multilingual support allow it to grade long, mixed-format responses consistently, and prior work shows its ratings align closely with expert evaluations [43,44].

DeepSeek-V3: DeepSeek-V3 [45] is a powerful 671B parameter Mixture-of-Experts model trained on a massive dataset spanning text, code, and math. It performs on par with leading proprietary models in both code generation and reasoning tasks. By pairing DeepSeek-V3 with GPT-4o as an evaluator, we gain a strong and independent second opinion, which helps boost the reliability of our results through agreement-based validation.

3.5.2. RCE Selection

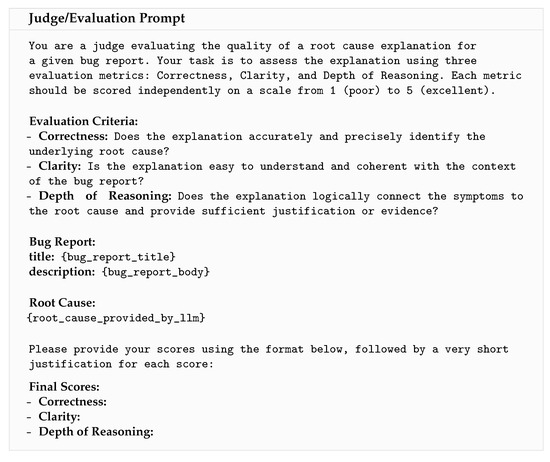

The evaluator LLMs judge each RCE produced by different LLMs in generation phase based on three criteria-correctness, clarity and depth of reasoning of LLM responses on a five-point Likert scale indicating poor to excellent rating (see Figure 3). Combining the scores we have converged overall quality of a RCE where correctness was deemed most important followed by depth of reasoning and clarity stated in Equation (1). is weighted overall-quality score, where C, L, D represents correctness, clarity and depth of reasoning, respectively, and are their weights. Equal weights were used to prevent arbitrary bias, as no empirical rationale supported differential weighting. The score was normalized using min-max normalization to fall within the [0, 1] interval.

Figure 3.

Evaluation Prompt Template-the judge reads a bug report and a proposed root cause, then gives quick 1–5 scores for correctness, clarity, and reasoning depth, with a one-line note for each.

We average across the two judges; the explanation with the highest mean score is selected as the final RCE for that bug report, with ties broken by the GPT-4o rating. This procedure yields a single, high-confidence explanation for each report while preserving a full ranking of the generator models for subsequent analysis.

For each bug report, we compute across the two judges’ scores. The root cause explanation with the highest mean becomes the report’s final RCE. In case of two explanations tie, we retain the one preferred by GPT-4o, whose ratings have shown a slightly stronger correlation with human judgments [43]. This selection process yields a single, high-confidence explanation per report while still preserving a complete ranking of all generator models for subsequent analysis.

4. Experiment

4.1. Dataset

In our study, we used the original 361 training bug reports from the dataset by Hirsch et al. [11], which were initially labeled for a classification task. However, our approach was different as we treated the problem as a generative task, aiming to have LLMs produce root cause explanations. We did not use the original labels; instead, we created prompts using just the titles and descriptions from each bug report to generate the root cause of the bugs. Due to GPU/hardware limitations, we had to filter out samples that were too long, which gave us a final set of 298 bug reports for our experiment.

4.2. Experimental Setup

We ran our experiments on a server with an NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPU that has 48 GB of GDDR6 memory. This setup let us comfortably work with large language models of up to 35 billion parameters, balancing performance with our hardware limits.

The dataset was saved in CSV format, which made it simple to load bug reports into the models consistently across all runs. After each experiment, we collected and saved all the outputs and evaluation results to analyze them thoroughly later on.

4.3. LLM Judges

The quality of the root cause explanation is crucial when software developers rely on LLM-generated insights during their bug-resolution process. To evaluate both the accuracy and overall quality of the explanations, we enlisted software developers to analyze and generate RCEs from the bug reports and then compare these with the RCEs produced by the generator LLMs.

We focused on three key qualities that make root cause explanations truly helpful for developers:

- Correctness: The explanation should clearly and precisely identify the actual root cause.

- Clarity: It needs to be easy for developers to understand and fit well within the context of the bug report.

- Depth of Reasoning: The explanation should connect the observed symptoms to the root cause logically, providing solid evidence to support the diagnosis.

Our human evaluators used these criteria to guide their assessments and ensure meaningful feedback.

5. Results

In this section, we show our experimental results and explain the research questions.

RQ1:

To what extent is RCEGen effective at producing correct, clear, and actionable root causes, and which LLM performs best?

In our experiment, we have evaluated a sample of 298 bug reports as explained in the Dataset Section 5 to judge the quality of LLM-produced Root Cause Explanation (RCE). We have employed five state-of-the-art Large Language Models (LLMs) mentioned above to generate RCEs. Each RCE was then evaluated using LLM judges such as DeepSeek-V3 and GPT-4o based on three criteria - correctness, clarity, and depth of reasoning of LLM responses on a 5-point Likert scale indicating poor to excellent rating. Combining the scores, we have converged on the overall quality of an RCE where correctness was deemed most important, followed by depth of reasoning and clarity, as stated in Equation (1). We have computed the overall quality () score using the Equation (1).

Table 1 summarizes the mean () and standard deviation () of judge scores of RCEs across different LLMs. Both evaluators, DeepSeek-V3 and GPT-4o, showed strong agreement in their assessments, with Qwen2.5-Coder-32B-Instruct emerging as the top performer. It received the highest average scores from both judges ( and ), reflecting its consistent ability to generate high-quality root cause explanations. Codestral-22B-v0.1 followed closely behind, earning solid scores ( and ), and securing the second-best performance overall. On the other end of the spectrum, OpenCoder-8B-Instruct ranked lowest with both judges, suggesting that its explanations may lack clarity, correctness, or depth. Overall, the close alignment between the two evaluators gives us confidence in the reliability of these rankings and highlights Qwen2.5-Coder-32B-Instruct and Codestral-22B-v0.1 as the most effective models in our evaluation.

Table 1.

Performance comparisons of LLM-generated RCEs across LLMs (mean ± SD).

Correctness: Qwen2.5-Coder-Instruct was able to produce more accurate RCEs as rated by both judges. Qwen2.5-Coder-Instruct, Codestral-22B-v0.1 and CodeLlama-34B-Instruct, these three models provided mostly correct root causes on average that are roughly corresponding to “good” to “excellent” correctness. On the other hand, DeepSeek-Coder-33B-Instruct and OpenCoder-8B-Instruct were less reliable in terms of correctness, 0.74–0.78 and 0.75–0.73, which suggests these models missed the underlying root cause more often. Hence, lower-ranked LLMs [36] often fail to identify the underlying root cause substantially more often than the top-tier LLMs.

Clarity: Codestral-22B-v0.1 and Qwen2.5-Coder-Instruct produced the most readable and clear explanations with average clarity scores around 0.88-0.82. CodeLlama-34B-Instruct followed closely behind. On the other hand, OpenCoder-8B-Instruct had the lowest clarity score, 0.68–0.51, which implies that its explanations were often vague or difficult to understand for developers. Interestingly, DeepSeek-Coder-33B-Instruct managed fairly clear explanations with mean scores of 0.84–0.78 even though its factual accuracy was weaker, highlighting that writing fluently doesn’t necessarily mean the content is correct.

Depth of reasoning: Depth of Reasoning was the weakest aspect across all models. Even the best models in this criterion achieved moderate depth scores, ranging from 0.61 to 0.66. Codestral-22B-v0.1 and Qwen2.5-Coder-Instruct have shown a similar type of depth of reasoning as per GPT-4o (Judge), and the scores are around 0.65–0.66. This suggests that even when these models correctly identified a bug’s root cause, their explanations lacked detail or deeper insight into the root cause. DeepSeek-Coder-33B-Instruct and OpenCoder-8B-Instruct performed worse, scoring between 0.51–0.56 as per GPT-4o judge and 0.52–0.54 as per DeepSeek-V3 judge, reflecting explanations that were often superficial and offered little insight into how exactly the identified cause led to the observed problem.

When we looked at the overall score , which combines Correctness, Clarity, and Depth of Reasoning, we found that Qwen2.5-Coder-32B-Instruct delivered the strongest performance in analyzing the root cause of bugs from bug reports. Codestral-22B followed closely behind, even outperforming a larger model like DeepSeek-Coder-33B-Instruct. On the other hand, smaller models such as OpenCoder-8B-Instruct struggled to keep up in this task.

Overall, these results suggest that larger, instruction-tuned models are better suited for root-cause analysis of bug reports, providing reliable correctness and clarity, though reasoning depth remains a limitation across the board.

RQ2:

To what extent are independent LLM judges reliable when scoring RCE quality (correctness, clarity, and depth of reasoning)?

To answer RQ2, we examined how closely the two LLM judges agreed in their evaluations. Table 2 reports inter-rater agreement using weighted Cohen’s kappa (), where values closer to 1 indicate stronger agreement beyond chance. Overall, the judges exhibited substantial agreement on correctness, moderate agreement on depth of reasoning, and low agreement on clarity.

Table 2.

Inter-rater reliability between LLM judges (weighted Cohen’s ).

Correctness: Agreement was consistently strong, with across models. For instance, correctness agreement reached for DeepSeek-Coder-33B-Instruct and for Codestral-22B-v0.1, showing that both DeepSeek-V3 and GPT-4o generally concurred on whether a generated explanation correctly identified the underlying root cause. This substantial consistency underscores the reliability of correctness judgments, which is particularly important since accurate fault identification is the primary objective of RCE generation.

Depth of reasoning: Agreement was moderate, with ranging from 0.53 to 0.65. The highest consistency was observed for DeepSeek-Coder-33B-Instruct (), while other models yielded slightly lower agreement (0.53–0.56). These results suggest that while judges usually shared similar views on the thoroughness of reasoning, some subjectivity remained in assessing how well explanations connected faults to their observable effects.

Clarity: In contrast, clarity exhibited the weakest agreement. For most models, values were very low, such as 0.122 for CodeLlama-34B-Instruct, 0.146 for Codestral-22B-v0.1, and 0.216 for Qwen2.5-Coder-Instruct, indicating frequent disagreement on readability and style. The only exception was OpenCoder-8B-Instruct (), where judges consistently rated explanations as unclear, resulting in higher agreement. This pattern highlights the inherent subjectivity of clarity assessments, suggesting that fluency and readability are more difficult to evaluate consistently compared to factual accuracy or reasoning depth.

In summary, the inter-rater analysis reveals that LLM judges provide stable and reliable assessments for correctness and depth of reasoning. However, Clarity exhibits low agreement (Cohen’s ), signalling that it is unreliable under our LLM-as-judge setting. To prevent this unstable dimension from distorting our primary ranking, we redefine the overall score Equation (1) to exclude Clarity:

We report the updated results in Table 3 alongside the original score in Table 1. The top models remain essentially unchanged, where Qwen2.5 Coder 32B retains the highest overall score under both judges, followed closely by Codestral 22B, while the lower ranks shift slightly.

Table 3.

Comparison overall scores of LLM-generated RCEs (mean ± SD).

RQ3:

To what extent do RCEGen’s explanations align with developer-authored root-cause analyses?

To address RQ3, we asked two senior developers to prepare reference root cause explanations for a stratified subset of 75 bug reports, as producing ground-truth summaries is highly labor-intensive. This sample size was determined using Yamane’s finite-population formula [46], which for 95% confidence and precision yields from our population of , which is adequate for validation. We then compared RCEGen outputs against these human-written explanations along two dimensions. First, we measured semantic similarity using CodeBERTScore, a widely adopted embedding-based metric for software-engineering text (range [0, 1]). Second, we assessed lexical similarity with ROUGE-L, which captures the longest common subsequence overlap.

As shown in Table 4, all top-tier models achieved strong semantic alignment with developer-written explanations. Qwen2.5-Coder-Instruct achieved the highest CodeBERTScore (0.989 ± 0.005), followed closely by Codestral-22B-v0.1 (0.987 ± 0.006) and CodeLlama-34B-Instruct (0.987 ± 0.006). DeepSeek-Coder-33B-Instruct also performed well (0.978 ± 0.009), while OpenCoder-8B-Instruct scored noticeably lower (0.947 ± 0.013), reinforcing its weaker performance observed in earlier analyses.

Table 4.

Similarity between LLM-generated and human-written root-cause explanations.

Lexical similarity revealed sharper distinctions. CodeLlama-34B-Instruct achieved the highest ROUGE-L score (0.183 ± 0.086), followed by Codestral-22B-v0.1 (0.165 ± 0.079) and DeepSeek-Coder-33B-Instruct (0.153 ± 0.063). By contrast, Qwen2.5-Coder-Instruct, despite leading in semantic similarity, produced a relatively lower ROUGE-L (0.134 ± 0.057), indicating that it conveyed the same meaning but with greater paraphrasing. OpenCoder-8B-Instruct again trailed substantially, with a negligible ROUGE-L of 0.017 ± 0.027.

Taken together, these findings show that RCEGen’s strongest models, Qwen2.5-Coder-Instruct, Codestral-22B-v0.1, and CodeLlama-34B-Instruct which achieve high semantic fidelity. The key distinction lies in style: Qwen2.5-Coder-Instruct prioritizes paraphrasing, while CodeLlama-34B-Instruct remains closer to the original wording. This suggests that high-quality RCEs may diverge lexically from human-written explanations without loss of semantic fidelity, highlighting the importance of embedding-based evaluation over surface-level overlap.

RQ4:

To what extent does the quality of a bug report’s title and description impact RCEGen’s accuracy in finding root causes?

To address RQ4, we examined how the quality of bug report titles and descriptions affects the ability of LLMs to generate accurate and useful root cause explanations. We adopted a quantitative, error-focused approach: after completing the primary evaluation in RQ1, we ranked RCEs by their overall score and closely inspected those with the lowest and highest ratings. This allowed us to identify recurring weaknesses in underperforming reports and recurring strengths in highly rated ones.

Weaknesses in low-scoring reports: Analysis of the weakest RCEs revealed several recurring deficiencies in the corresponding bug reports. These included vague or overly short titles that failed to establish context, missing or incomplete reproduction steps, and descriptions that lacked concrete evidence such as error messages, logs, or stack traces. For instance, reports with titles such as “Crash in RateLimiter delete” provided insufficient information for LLMs to ground their reasoning, often resulting in speculative or superficial explanations. These findings suggest that when critical diagnostic cues are absent, LLMs default to plausible but weakly supported hypotheses, reducing both correctness and depth of reasoning.

Strengths in high-scoring reports: By contrast, the best-performing RCEs were consistently associated with reports that contained at least three key diagnostic cues: (i) a specific error message that pinpointed the failure mode, (ii) a minimal reproduction snippet that provided concrete execution context, and (iii) a clear statement of expected versus actual behavior. Together, these elements disambiguated the defect, allowing the LLMs to anchor their explanations in observable evidence. In these cases, models not only identified the fault correctly but also articulated deeper reasoning chains that linked symptoms to underlying causes.

- 1.

- Under-specification: Short titles/descriptions lacking both context and reproduction cues yielded shallow, speculative explanations. The canonical case is shown in Figure 4. With only the two-word title “RRateLimiter delete” and a minimal code snippet, CodeLlama-34B-Instruct conjectured that “the client attempts to delete a rate-limiter” whereas the true defect was that delete() fails to remove all Redis keys allocated by the rate-limiter. Without signals about the observable evidence the LLM defaulted to a generic interpretation.

Figure 4. Example of an Under-specified Bug Report.

Figure 4. Example of an Under-specified Bug Report. - 2.

- Missing cross-checks: Even when a stack trace was provided, the absence of “expected vs. actual” text led models into symptom chasing. They recited the top frame of the trace as the “cause” instead of reasoning about why the exception was thrown.

- 3.

- Ambiguous scope: Reports describing multi-component workflows, for example, front-end and backend API, but omitting module boundaries, caused hallucinated fixes that touched the wrong subsystem. Titles naming only a high-level feature like Search page fails provided no steer on which layer was responsible.

Interpretation: These results reinforce the analogy between LLM-based and human-led debugging. Just as developers rely on structured, evidence-rich bug reports to efficiently diagnose defects, LLMs excel when provided with clear, unambiguous signals. Conversely, when reports lack these signals, even state-of-the-art models revert to shallow reasoning. This finding highlights that improvements in LLM-based RCA cannot rely solely on model scaling or prompting strategies, but also require attention to the quality and structure of the input data.

Implications for RCA workflows: Based on these observations, we propose two avenues for improving RCA workflows. First, automated diagnostics could be integrated into issue trackers to flag low-quality bug reports—such as those with short titles, missing “Steps to Reproduce,” or absent expected/actual fields—before RCA is attempted. This would ensure that LLMs (and human developers) operate on reports with sufficient grounding. Second, interactive prompting mechanisms could enable LLMs to request missing details from reporters, thereby transforming RCA into a more collaborative process. Both strategies would not only enhance the quality of model outputs but also align automated RCA more closely with established software engineering practices.

6. Discussion

Across our corpus, RCEGen consistently generated useful root–cause explanations (RCEs). As shown in Table 1, Qwen-2.5-Coder-32B achieved the strongest balance between correctness and depth of reasoning, while Codestral-22B-v0.1 produced the most readable and developer-friendly narratives. All evaluated models reached acceptable levels of clarity. However, the main limitation remains the depth of reasoning: explanations frequently identified a fault but often failed to articulate the causal chain linking observed symptoms to violated invariants. This limitation can be attributed to the lack of grounding in many bug reports, which frequently omit reproduction steps and supporting artifacts such as logs or stack traces. Without such evidence, models struggle to justify their conclusions with sufficient depth.

Inter-rater agreement scores in Table 2 further support these observations. The two state-of-the-art LLM judges demonstrated substantial consistency in assessing correctness and moderate agreement on depth, but their agreement on clarity was notably weaker. Given this low agreement (Cohen’s ), we exluded Clarity from the primary Equation (1) to avoid propagating instability into the ranking. Specifically, we computed the revised overall score as Equation (2) and reported the results in Table 3 alongside the original score in Table 1. The revised ranking preserves the top two positions and slightly compresses gaps among mid-tier models, indicating that prior differences attributable to stylistic presentation were amplifying totals despite low reliability. Weighted Cohen’s indicates that factual accuracy and reasoning depth can be evaluated stably across models, whereas clarity assessments remain more sensitive to prompt design and evaluation criteria. To strengthen future evaluations, we recommend: (i) refining clarity metrics to prioritize structure, terminology precision, and conciseness, and (ii) aggregating results across multiple judges, either by majority vote or confidence-weighted averaging. Practically, this suggests that when accurate fault identification is the primary goal, RCEGen can be configured to favor Qwen-2.5-Coder-Instruct, whereas for ticket-ready explanations requiring minimal editing, Codestral-22B-v0.1 may be preferable.

As shown in Table 4, LLM-generated RCEs are semantically very close to developer-written explanations, while exhibiting relatively low lexical overlap. This indicates that models paraphrase faithfully rather than replicate verbatim, confirming that evaluation pipelines based solely on lexical similarity measures (e.g., ROUGE-L) underestimate explanation quality. Root cause explanations with low Depth of Reasoning scores typically lacked concrete evidence links, such as reproduction steps or contextual logs. For instance, in the “RRateLimiter delete” (see Figure 4) bug report, the reporter provided insufficient context in the title and no failure evidence in the bug description, such as logs or stack traces, limiting the explanation’s grounding. A more comprehensive evaluation stack should therefore combine semantic similarity metrics (e.g., CodeBERT) with judge-based scoring of correctness and reasoning depth. We also observed that under-specified bug reports consistently reduced explanation quality. Reports with short or vague titles, missing reproduction steps, or absent expected/actual behavior often led to fluent but weakly supported hypotheses, lowering both correctness and depth scores. The “RRateLimiter delete” case exemplifies this phenomenon. To address this, we propose structured bug report templates that require a clear title, detailed environment information, reproducible steps, annotated code or log snippets, and scope hints such as recent changes. Automated linting tools that flag missing elements could further improve both LLM-generated RCEs and human-led triage.

Our experiments were intentionally conducted under constrained conditions: stock LLMs, zero-shot prompting, and a hard limit of three sentences per RCE. While these choices ensured readability and comparability across models, they restricted the space available to articulate full chains of evidence. Moreover, since no retrieval or external tools were used and RCA focused on pre-fix bug triage, models relied solely on the information contained in bug reports, and the inputs were limited to title and description. When reproduction steps or stack traces were absent in description, both correctness and reasoning depth declined, while clarity remained comparatively stable. These design choices help explain the patterns observed in Table 1 and Table 2: strong clarity, moderate reasoning depth, and higher cross-judge agreement on factual and analytic aspects compared to stylistic ones.

Overall, our findings demonstrate that state-of-the-art open-source LLMs can produce root cause explanations that are generally correct, clear, and actionable, while also underscoring the need for richer inputs and refined evaluation methods to achieve greater reasoning depth.

Study Takeaways

The results of our evaluation provide not only quantitative evidence of model performance but also broader insights into the opportunities and limitations of employing large language models for automated root cause analysis. While metrics such as correctness, clarity, and reasoning depth capture performance at a granular level, synthesizing these findings into higher-level takeaways offers a clearer understanding of their practical implications. By reflecting on how our results align with or diverge from prior research, we identify where generative approaches extend beyond traditional classification-based methods, pinpoint current limitations, and outline how future work can address these gaps. The following takeaways summarize the key lessons learned from this study and highlight directions for both researchers and practitioners seeking to integrate LLMs into bug triaging and debugging workflows.

To contextualize our findings within the broader body of research, we summarize them into the following key takeaways, which highlight the study’s insights, limitations, and implications:

- Generative RCA surpasses classification-based approaches. Previous studies largely conceptualized automated RCA as a classification task, predicting coarse-grained categories of root causes [9,10,11]. While useful for bug triaging, these models often produced ambiguous results that still required manual inspection [17]. Our findings confirm concerns raised by Catolino et al. [28] that “not all bugs are the same,” and that fixed categories cannot capture the diversity of root causes. By reframing RCA as a generative task, RCEGen enables LLMs to produce detailed, context-specific explanations, thereby addressing the lack of fine-grained outputs that prior classification-based methods struggled to deliver.

- Qwen2.5-Coder-Instruct and Codestral-22B deliver the strongest performance. Consistent with earlier findings that larger, instruction-tuned models outperform smaller models in software engineering tasks [32,33], we observed that Qwen2.5-Coder-Instruct and Codestral-22B generated the most accurate and useful root cause explanations. These results extend work of Plein et al. [31], who found that LLMs like ChatGPT could generate useful test cases from bug reports, but only when sufficient capacity and training breadth were present. In contrast, lightweight models such as OpenCoder-8B underperformed, reinforcing earlier observations by Hirsch et al. [10] that smaller models fail to capture the complexity of real-world bug reports.

- Correctness is strong, but reasoning depth remains limited. While models in our study achieved high correctness (≈0.89), their reasoning depth remained moderate (0.65). This mirrors findings by Du et al. [34] that pre-trained models achieve reasonable accuracy in bug prediction but fail to capture deeper semantic chains. Similarly, Jin et al. [30] showed in program repair tasks that LLMs often propose correct patches but struggle to justify their correctness with deeper reasoning. Our results extend these insights by showing that in RCA, correctness without depth produces explanations that identify a fault but fail to connect it to observable symptoms—limiting their diagnostic value.

- Evaluator LLMs provide stable, complementary judgments. Our use of GPT-4o and DeepSeek-V3 as independent evaluators aligns with recent work demonstrating that LLMs can serve as reliable judges in software engineering tasks [43,44]. We found substantial agreement on correctness ( 0.70), similar to Wang et al.’s (2025) observation that LLM-judges align closely with human evaluators on factual dimensions. However, low agreement on clarity echoes concerns raised by Kumar et al. [35], who found that readability and stylistic attributes are more subjective and less consistently judged by LLMs. This suggests that hybrid pipelines, which combine LLM and human judgments, may remain necessary.

- Semantic alignment with developer analyses is high. We observed strong semantic similarity (CodeBERT ≈ 0.98) between LLM-generated and developer-written explanations, even though lexical overlap (ROUGE-L < 0.27) was low. This finding complements work [32] on bug summarization, which showed that LLMs can paraphrase bug descriptions faithfully without exact word matches. Similarly, Plein et al. [31] demonstrated that LLMs generate semantically meaningful but lexically different reproducing test cases. Our results confirm that semantic alignment, rather than surface similarity, is a more faithful metric for evaluating RCA outputs.

- Bug report quality strongly influences model effectiveness. Our findings reinforce Bettenburg et al.’s [6] seminal study showing that bug report quality strongly affects triaging and resolution outcomes. In our evaluation, vague titles or missing expected/actual behavior consistently led to speculative and shallow explanations, a pattern consistent with Tan et al. [14], who showed that defect characteristics influence developers’ ability to localize faults. By contrast, reports with error messages and reproduction steps enabled LLMs to produce accurate and actionable root cause explanations. This highlights the continued importance of structured bug reporting templates, echoing Baysal et al. [8] and Hirsch et al. [10], who argued that report quality is a central determinant of debugging efficiency.

- Future improvements require richer inputs and adaptive prompting. Earlier studies have emphasized the value of augmenting RCA with richer contextual signals, such as execution logs or code diffs [15]. Jin et al. [30] similarly showed that external signals improve program repair quality, while Du et al. [34] found that bug prediction benefits from contextual metadata. Our results suggest that adaptive prompting, where LLMs request missing details from reporters, could complement these approaches. This aligns with Zhang et al. [33], who proposed interactive, in-context learning for cloud incident RCA. Together, these studies suggest hybrid frameworks where generative RCA is enhanced by additional context and adaptive clarification mechanisms.

7. Threats to Validity

7.1. Internal Validity

Several validity concerns may influence our findings, and we discuss both their implications and our mitigation strategies. First, the evaluation of bug reports relied on manual assessment, which can introduce subjectivity. To enhance reliability, we employed multiple independent reviewers and reconciled differences through structured discussion, thereby reducing individual bias. Second, our dataset emphasizes memory, concurrency, and semantic bugs from widely used GitHub projects. This focus is valuable because these bug categories are both prevalent in practice and difficult to address. Yet, they could inadvertently skew performance estimates by over-representing them relative to other defect classes (e.g., user-interface errors, configuration issues, or documentation-related defects). If left unbalanced, the models may appear more effective than they would in a broader, more heterogeneous bug population. To mitigate this, we adopted stratified sampling procedures to preserve representation of additional bug types where possible, and we made the remaining distributional imbalance explicit in our reporting. This transparency enables readers to interpret the results with an understanding of which categories are better supported by our data and where generalization may be limited. Third, potential overlap in training data between the generator and evaluator LLMs may lead to correlated errors. To mitigate this, we used two architecturally distinct evaluator models and measured inter-rater agreement, ensuring that results are not solely dependent on a single model’s behavior. Finally, RCE evaluation metrics (correctness, depth of reasoning, clarity) were scored by a closed LLM-as-Judge loop without direct human evaluation of the full RCE set, due to resource and time constraints. While we partially mitigate this through inter-judge agreement analysis and semantic similarity comparison against a sample human evaluation, these measures do not fully eliminate the concern. Accordingly, we identify the LLM-based evaluation as a significant limitation to internal validity.

7.2. External Validity

Our study is limited to bug reports from Java open-source projects hosted on GitHub, so the results may not generalize to other languages or proprietary codebases. Furthermore, the dataset excludes very long, in-depth tickets due to prompt token-length limits, meaning that verbose or poorly structured reports, common in industrial settings, are underrepresented. Consequently, the generalizability of the RCEGen framework’s effectiveness to closed-source or multi-language environments remains to be confirmed in future work.

8. Limitations

Our study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, we rely primarily on an LLM-as-judge evaluation, with only limited human assessment. While we took care to calibrate prompts and scoring criteria, this setup introduces a risk to internal validity. Second, the evaluation corpus is focused solely on Java bug reports from open-source GitHub repositories. As a result, the findings may not generalize to other programming languages, development ecosystems, or proprietary environments.

Third, we excluded particularly long or verbose bug tickets due to context length constraints. In practice, this led to a smaller dataset: although we began with a larger pool, filtering and resource limits, especially GPU memory and token budgets, reduced the final sample to 298 reports.

On the methodology side, we deliberately adopted a constrained prompting setup: all models were evaluated in a zero-shot setting, with a strict three-sentence response cap and no access to retrieval or external tools. This design prioritizes comparability across models but likely underestimates their full potential. Additionally, the bug type distribution in our dataset is skewed toward memory, concurrency, and semantic issues. This may bias the results away from categories like UI, configuration, or documentation-related bugs.

Finally, due to compute constraints and cost, our evaluation focused exclusively on small open-source models. Proprietary or closed-weight systems were not included, which limits broader generalization. These factors, taken together, affect both the absolute performance scores and the validity of cross-model comparisons.

9. Future Work

Future extensions focus on scale, integrated context, and stronger evaluation. On scale, the framework will be extended to larger and more diverse bug datasets spanning multiple programming languages and issue trackers, including longer, multi-paragraph tickets that better reflect real-world practice. For context, the current zero-shot setup is replaced with a single retrieval-and-reflection loop: a lightweight retriever gathers related bug reports or issues, preferably those with brief explanations, small diffs, traces, or logs, and the model uses this material to draft an initial root-cause explanation, critique it, and revise it over a small number of iterations. To ensure consistent use of retrieved context, prompts instruct the model to cite the items it relied on (e.g., issue IDs, file or function names, diff lines) and to return a compact structure capturing the fault location, trigger, propagation, and a brief fix hint, useful for auditing the correctness of LLM-generated responses.

Beyond retrieval, we also plan to explore models with longer context windows and lightweight fine-tuning (e.g., instruction tuning or LoRA) of smaller code models to better support the RCA task while keeping costs manageable. For explainability, our goal is traceable reasoning: each statement in the root-cause explanation should be backed by some part of the input context. To evaluate this, we will measure both rubric-based scores (e.g., correctness, depth) and how well the explanation aligns with the retrieved evidence.

To support adoption and replication, we will release sanitized data slices, prompt templates, scoring scripts, and configuration files, along with a lightweight plug-in for project-specific retrieval, enabling others to extend RCEGen in real-world engineering settings.

10. Conclusions

This study introduces RCEGen, an LLM-based framework that leverages code-oriented LLMs to generate root-cause explanations from bug reports and then ranks those explanations with two independent LLM judges. On our benchmark, Qwen2.5-Coder-Instruct delivered the strongest results, reaching an overall quality of ≈0.80 and a correctness score of 0.89. Codestral-22B-v0.1 (overall ≈ 0.78, correctness 0.87) and CodeLlama-34B-Instruct (overall ≈ 0.69) formed the next tier, while the remaining models lagged. Judge agreement was substantial for correctness () and moderate for depth (), supporting the stability of these rankings, but much lower for clarity ( for most models), indicating that readability remains difficult to score automatically. A qualitative review corroborated these findings, which showed that bug reports that included concrete error messages, reproduction steps, and an explicit comparison of expected and actual behavior consistently produced higher-quality explanations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.H.M. and A.D.; Methodology, R.H.M., A.D. and W.A.; Software, R.H.M.; Validation, R.H.M., A.D., A.H.M. and W.A.; Formal analysis, R.H.M., A.D. and W.A.; Investigation, R.H.M.; Resources, R.H.M. and A.H.M.; Data curation, A.D. and A.H.M.; Writing—original draft, R.H.M., A.D. and W.A.; Writing—review & editing, R.H.M. and W.A.; Visualization, R.H.M. and A.D.; Supervision, W.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these datasets. The data are not publicly available at this time as they form part of an ongoing study. Data are, however, available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rooney, J.J.; Heuvel, L.N.V. Root cause analysis for beginners. Qual. Prog. 2004, 37, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Van Moll, J.; Jacobs, J.; Freimut, B.; Trienekens, J. The importance of life cycle modeling to defect detection and prevention. In Proceedings of the 10th International Workshop on Software Technology and Engineering Practice, Montreal, QC, Canada, 6–8 October 2002; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 144–155. [Google Scholar]

- Adeel, K.; Ahmad, S.; Akhtar, S. Defect prevention techniques and its usage in requirements gathering-industry practices. In Proceedings of the 2005 Student Conference on Engineering Sciences and Technology, Karachi, Pakistan, 27 August 2005; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, S.; Roper, M. What’s in a bug report? In Proceedings of the 8th ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement, Torino, Italy, 18–19 September 2014; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, X.; Lo, D.; Wang, X.; Zhou, B. Accurate developer recommendation for bug resolution. In Proceedings of the 2013 20th Working Conference on Reverse Engineering (WCRE), Koblenz, Germany, 14–17 October 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bettenburg, N.; Just, S.; Schröter, A.; Weiss, C.; Premraj, R.; Zimmermann, T. What makes a good bug report? In Proceedings of the 16th ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Foundations of Software Engineering, Atlanta, GA, USA, 9–14 November 2008; pp. 308–318. [Google Scholar]

- Dalal, S.; Chhillar, R.S. Empirical study of root cause analysis of software failure. ACM SIGSOFT Softw. Eng. Notes 2013, 38, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baysal, O.; Holmes, R.; Godfrey, M.W. Revisiting bug triage and resolution practices. In Proceedings of the 2012 First International Workshop on User Evaluation for Software Engineering Researchers (USER), Zurich, Switzerland, 5 June 2012; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, H.; Pahwa, G. Root cause analysis of software bugs using machine learning techniques. In Proceedings of the 2017 7th International Conference on Cloud Computing, Data Science & Engineering-Confluence, Noida, India, 12–13 January 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, T.; Hofer, B. Root cause prediction based on bug reports. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Software Reliability Engineering Workshops (ISSREW), Coimbra, Portugal, 12–15 October 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 171–176. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, T.; Hofer, B. Using textual bug reports to predict the fault category of software bugs. Array 2022, 15, 100189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaedi, S.A.; Noaman, A.Y.; Gad-Elrab, A.A.; Eassa, F.E. Nature-based prediction model of bug reports based on Ensemble Machine Learning Model. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 63916–63931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, C.; Ma, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, X. LLM-BRC: A large language model-based bug report classification framework. Softw. Qual. J. 2024, 32, 985–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Liu, C.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhai, C. Bug characteristics in open source software. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2014, 19, 1665–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thung, F.; Lo, D.; Jiang, L. Automatic recovery of root causes from bug-fixing changes. In Proceedings of the 2013 20th Working Conference on Reverse Engineering (WCRE), Koblenz, Germany, 14–17 October 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kawrykow, D.; Robillard, M.P. Non-essential changes in version histories. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Software Engineering, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–28 May 2011; pp. 351–360. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, Z.; Li, B.; Sun, X.; Chen, T.; Tang, B.; Shi, X. Analyzing bug fix for automatic bug cause classification. J. Syst. Softw. 2020, 163, 110538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chillarege, R.; Bhandari, I.S.; Chaar, J.K.; Halliday, M.J.; Moebus, D.S.; Ray, B.K.; Wong, M.Y. Orthogonal defect classification-a concept for in-process measurements. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 1992, 18, 943–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluri, B.; Wursch, M.; PInzger, M.; Gall, H. Change distilling: Tree differencing for fine-grained source code change extraction. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2007, 33, 725–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falleri, J.R.; Morandat, F.; Blanc, X.; Martinez, M.; Monperrus, M. Fine-grained and accurate source code differencing. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Automated Software Engineering, Vsters, Sweden, 15–19 September 2014; pp. 313–324. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.; Neamtiu, I.; Gupta, R. Predicting concurrency bugs: How many, what kind and where are they? In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, Nanjing, China, 27–29 April 2015; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, H.A.; Bawany, N.Z.; Shamsi, J.A. Capbug-a framework for automatic bug categorization and prioritization using nlp and machine learning algorithms. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 50496–50512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, N.; Namoun, A.; Alyas, T.; Tufail, A.; Taqi, M.; Kim, K.H. Classification of bugs in cloud computing applications using machine learning techniques. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limsettho, N.; Hata, H.; Monden, A.; Matsumoto, K. Automatic unsupervised bug report categorization. In Proceedings of the 2014 6th International Workshop on Empirical Software Engineering in Practice, Osaka, Japan, 12–13 November 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Limsettho, N.; Hata, H.; Monden, A.; Matsumoto, K. Unsupervised bug report categorization using clustering and labeling algorithm. Int. J. Softw. Eng. Knowl. Eng. 2016, 26, 1027–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xu, Z.; Yang, D.; Yan, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, H.; Xue, L.; Fan, M. An unsupervised cross project model for crashing fault residence identification. IET Softw. 2022, 16, 630–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Std 1044-2009; IEEE Standard Classification for Software Anomalies. IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Catolino, G.; Palomba, F.; Zaidman, A.; Ferrucci, F. Not all bugs are the same: Understanding, characterizing, and classifying the root cause of bugs. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.11031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Pai, K.S.; Devanbu, P.; Barr, E. Automatic semantic augmentation of language model prompts (for code summarization). In Proceedings of the IEEE/ACM 46th International Conference on Software Engineering, Lisbon, Portugal, 14–20 April 2024; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, M.; Shahriar, S.; Tufano, M.; Shi, X.; Lu, S.; Sundaresan, N.; Svyatkovskiy, A. Inferfix: End-to-end program repair with llms. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM Joint European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering, San Francisco, CA, USA, 3–9 December 2023; pp. 1646–1656. [Google Scholar]

- Plein, L.; Bissyandé, T.F. Can llms demystify bug reports? arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.06310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, B.; Shao, Y. SUMLLAMA: Efficient Contrastive Representations and Fine-Tuned Adapters for Bug Report Summarization. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 78562–78571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ghosh, S.; Bansal, C.; Wang, R.; Ma, M.; Kang, Y.; Rajmohan, S. Automated root causing of cloud incidents using in-context learning with GPT-4. In Proceedings of the Companion Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on the Foundations of Software Engineering, Porto de Galinhas, Brazil, 15–19 July 2024; pp. 266–277. [Google Scholar]

- Du, X.; Li, C.; Ma, X.; Zheng, Z. How Does Pre-trained Language Model Perform on Deep Learning Framework Bug Prediction? In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/ACM 46th International Conference on Software Engineering: Companion Proceedings, Lisbon, Portugal, 14–20 April 2024; pp. 346–347. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Haiduc, S.; Das, P.P.; Chakrabarti, P.P. LLMs as Evaluators: A Novel Approach to Evaluate Bug Report Summarization. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.00630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xia, C.S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L. Is your code generated by chatgpt really correct? rigorous evaluation of large language models for code generation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 21558–21572. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, B.; Yang, J.; Cui, Z.; Yang, J.; Liu, D.; Zhang, L.; Liu, T.; Zhang, J.; Yu, B.; Lu, K.; et al. Qwen2.5-Coder Technical Report. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.12186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Zhu, Q.; Yang, D.; Xie, Z.; Dong, K.; Zhang, W.; Chen, G.; Bi, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.K.; et al. DeepSeek-Coder: When the Large Language Model Meets Programming—The Rise of Code Intelligence. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.14196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AI, M. Codestral: A State-of-the-Art Code Language Model. 2024. Available online: https://mistral.ai/news/codestral/ (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Rozière, B.; Gehring, J.; Gloeckle, F.; Sootla, S.; Gat, I.; Tan, X.E.; Adi, Y.; Liu, J.; Sauvestre, R.; Remez, T.; et al. Code Llama: Open Foundation Models for Code. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2308.12950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Cheng, T.; Liu, J.K.; Hao, J.; Song, L.; Xu, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, C.; Chai, L.; et al. OpenCoder: The Open Cookbook for Top-Tier Code Large Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2411.04905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, A.; Lerer, A.; Goucher, A.P.; Perelman, A.; Ramesh, A.; Clark, A.; Ostrow, A.; Welihinda, A.; Hayes, A.; Radford, A. GPT-4o System Card. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.21276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Guo, J.; Gao, C.; Fan, G.; Chong, C.Y.; Xia, X. Can llms replace human evaluators? an empirical study of llm-as-a-judge in software engineering. Proc. ACM Softw. Eng. 2025, 2, 1955–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Zhuang, S.; Montgomery, K.; Tang, W.Y.; Cuadron, A.; Wang, C.; Popa, R.A.; Stoica, I. Judgebench: A benchmark for evaluating llm-based judges. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.12784. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.; Feng, B.; Xue, B.; Wang, B.; Wu, B.; Lu, C.; Zhao, C.; Deng, C.; Zhang, C.; Ruan, C. DeepSeek-V3 Technical Report. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2412.19437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, T. Statistics: An Introductory Analysis; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA; Evanston: London, UK; John Weatherhill, Inc.: Tokyo, Japan, 1973. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).