Abstract

Nucleic acid-based gene interfering and editing molecules, such as antisense oligonucleotides, ribozymes, small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), and CRISPR-Cas9-associated guide RNAs, are promising gene-targeting agents for therapeutic applications. Cancer’s heterogeneous and diverse nature demands gene-silencing technologies that are both specific and adaptable. RNase P ribozymes, called M1GS RNAs, are engineered constructs that link the catalytic M1 RNA from bacterial RNase P to a programmable guide sequence. This guide sequence directs the M1GS ribozyme to base-pair with a target RNA, inducing it to fold into a structure resembling pre-tRNA. Catalytic activity can be enhanced through in vitro selection strategies. In this review, we will discuss the application of M1GS ribozymes in targeting cancer-associated RNAs, focusing on the BCR-ABL transcript in leukemia, the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) of hepatitis C virus (HCV), and the replication and transcription activator (RTA) of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV). Together, these examples highlight the versatility of M1GS ribozymes across both viral and cellular oncogenic targets, underscoring their potential as a flexible synthetic biology platform for cancer therapy.

1. Introduction

Cancer is a highly multifaceted disease, characterized by abnormal and uncontrolled cell division. It can arise in various ways, including point mutations, chromosomal translocations, epigenetic changes, and viral infections [1]. Cancers are generally patient-specific and highly heterogeneous between different tumors, and even between cells within the same tumor [2]. Although no two cancers are identical, they can all be unified by hallmarks. These hallmarks include increased cell proliferation, evasion of growth suppressors, resistance to apoptosis, induction of angiogenesis, acquisition of replicative immortality, and the ability to metastasize. However, cancers do not always exhibit all of them at once, acquiring them in varying combinations over the course of their progression [3].

Current cancer treatments are generally limited by specificity or a lack thereof. Traditional cancer treatments typically include chemotherapy and radiation therapy, which mainly target rapidly dividing cells regardless of whether they are cancerous or not [4]. These therapies can be toxic due to the indiscriminate nature of the treatment. Patients may experience hair loss due to these treatments because cells in hair follicles divide rapidly and are targeted by these therapies [5]. More targeted therapies, such as small-molecule inhibitors, immunotherapies, and monoclonal antibodies, among others, are often too specific and limit the treatments to a particular mutation or abnormal protein [4,6]. Although treatments are plentiful on both sides of the spectrum, broadly targeting agents may be highly toxic as they indiscriminately destroy rapidly dividing cells, whereas narrowly targeted therapies are prone to resistance and cannot be used across a variety of cancer types.

Due to the limitations of current cancer treatments, there is a growing need for therapeutics that are both programmable to accommodate the diversity of cancer and modular in design, ensuring both precision and adaptability. A promising strategy involves repurposing the catalytic RNA subunit of eubacterial ribonuclease P (RNase P), an enzyme responsible for processing precursor tRNAs [7,8]. The M1GS ribozyme is constructed by attaching a guide sequence (GS) to the catalytic RNA subunit of RNase P in E. coli (also called M1 RNA) [9]. M1GS ribozymes require precise base pairing to force the target RNA into a part of a pre-tRNA structure, allowing it to recognize and cleave [7,8]. This approach enables silencing at the RNA level without genomic alteration, and its modular design allows the GS to be easily reprogrammed to target different mRNAs or accommodate variations that may arise [9]. These properties position RNase P ribozymes as a class of exciting RNA therapeutics within the field of synthetic biology, capable of adapting to the shifting landscape of cancer complexity and therapeutic resistance.

2. Current Approaches in Gene Therapy

Advances in gene therapy have introduced powerful tools capable of silencing or altering gene expression at both the DNA and RNA levels. RNA interference (RNAi) targets mRNA transcripts for degradation by guiding the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to complementary sequences, preventing translation [10]. While RNAi is highly programmable and relatively easy to design, challenges, such as off-target effects caused by oversaturation of the cell’s RNAi machinery, remain [11,12]. In contrast, zinc finger nucleases (ZFN), transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), meganucleases, and Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein (Cas) complexes operate at the DNA level, inducing double-stranded breaks to disrupt or correct genes [13]. The CRISPR-Cas system introduces double-stranded breaks at specific loci through base pairing between the target DNA and the guide RNA [14]. Due to CRISPR working at the DNA level, safety concerns arise for therapeutic applications, as off-target effects can result in permanent genomic alterations [14]. To address these concerns, strategies utilizing Cas9 variants have been successful in increasing precision by recognizing longer Proto-spacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequences [14,15]. However, this precision comes at a cost of therapeutic effectiveness. Increasing precision narrows the range of accessible genomic sites, where single-nucleotide mutations in the target site may prevent recognition, allowing variants to escape treatment [16,17]. In contrast, protein-guided nucleases such as ZFNs, TALENs, and meganucleases exhibit low off-target activity due to their engineered DNA-binding domains. However, their complex design and large size make them less flexible for re-targeting and pose challenges for delivery [18,19].

M1GS ribozymes offer a highly programmable alternative by combining sequence-specific recognition of the guide sequences (GS) with the catalytic activity of M1 RNA, the RNA subunit of bacterial RNase P, a pre-tRNA maturation enzyme [8,9]. M1GS ribozymes function entirely at the RNA level, without the need for delivery of exogenous proteins [20]. M1GS, similar to RNAi, has multi-turnover potential, allowing one M1GS to cleave multiple RNA substrates [7,21]. Unlike traditional antisense strategies that may tolerate partial mismatches or hairpins and other unintended secondary structures, M1GS ribozymes require base pairing to force the target RNA into a pre-tRNA-like structure, ensuring that matched sequences are cleaved [7,9,22]. It is the combination of high specificity and flexibility that makes the M1GS ribozyme an exciting prospect for therapies. In this review, we will discuss M1GS’s potential in targeting cancer-associated transcripts, examining its design, optimization, and applications for anticancer therapy.

3. RNase P and Its Catalytic RNA

RNase P (ribonuclease P) is an enzyme responsible for cleaving the 5′ leader sequence from tRNA precursors and other small RNAs [7,23,24]. RNase P can contain different compositions in nature, ranging from RNA-based holoenzymes to fully proteinaceous human mitochondrial RNase P [7,25]. RNase P, found in all domains of life, may consist of a catalytic RNA subunit and protein cofactor [7,26]. The RNase P holoenzyme typically contains 1 protein subunit in Bacteria, 4 protein subunits in Archaea, and up to 10 protein subunits in Eukaryotes. RNase P from Escherichia coli comprises a 377-nucleotide-long M1 RNA and a 14 kDa, 119 amino acid-long C5 protein cofactor [8]. Both the RNA subunit and protein cofactor are required in vivo. Structural analysis of the M1 RNA–protein interaction, utilizing crystallography, cryo-EM, mutational, and phylogenetic studies, supports our current understanding that the protein subunit is responsible for stabilizing and correctly folding M1 RNA into its active form [7,8,23,27,28]. The sequences of the bacterial RNase P RNA subunits corresponding to the catalytic core regions are highly conserved among different bacterial species as they are important for the folding and maintaining of the active conformations and for catalysis. Stabilization and proper folding of M1 RNA by C5 protein is believed to promote RNase P’s preferential binding to pre-tRNA over mature tRNA, possibly through pre-organizing metal ion binding sites [20,29,30,31,32,33,34,35].

Early in vitro studies on RNase P confirmed that under high concentrations of , M1 RNA could cleave pre-tRNA substrates in the absence of C5 protein [20]. Follow-up studies have shown that M1 RNA can function in human cells, albeit at a reduced level, limited by the ability of the human RNase P protein (Rpp) to compensate for the absence of the C5 protein [36,37,38]. These findings confirmed the catalytic ability of M1 RNA and the structural and regulatory functions of the protein cofactors. This insight, along with RNA’s modularity and ease of synthesis, shifted the focus to engineering RNA-only constructs, leading to the development of EGS and M1GS ribozymes.

4. RNase P Substrate Recognition and Engineering of Gene-Targeting Ribozymes from RNase P RNA

4.1. External Guide Sequences (EGS)

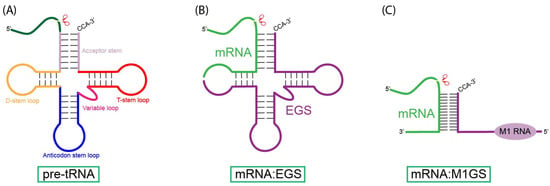

Unlike sequence-specific endonucleases such as restriction enzymes, RNase P recognizes and cleaves substrates based on shared structural motifs [9,39,40]. These structures include the T-stem/loop, acceptor stem-like elements, and unpaired 5′ leader regions (Figure 1), which allow RNase P to cleave pre-tRNAs, 4.5S RNA precursors, and other small structured RNAs [8,9,39,40]. To determine the minimal structural elements required for RNase P recognition and cleavage, researchers determined that cleavage mediated by M1 RNA would occur as long as the substrate included the acceptor stem, T-stem/loop, and the 3′ CCA sequence [39,40]. These findings suggest that RNase P and M1 RNA cleavage can be redirected to cleave target substrates that mimic the structure of the natural substrate. Building on these findings, researchers developed external guide sequences (EGS), short antisense oligonucleotides that bind to target RNAs through Watson–Crick interactions. Once base-paired, the resulting hybrid adopts a pre-tRNA structure that either human RNase P or an M1 RNA can detect and subsequently cleave (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Substrates for RNase P and M1 RNA. (A) The natural substrate for RNase P, pre-tRNA, contains structural elements including the acceptor stem, T-stem loop, variable loop, D-stem loop, and the anticodon stem loop. RNase P cleaves at the CCA-3′ tail of the acceptor stem. (B) External guide sequences (EGS) base-pair with the target mRNA, forming analogous structures to the pre-tRNA substrate, which allows for detection and subsequent cleavage by RNase P. (C) The M1GS ribozyme binds to a target mRNA substrate through complementary base pairing of its guide sequence (GS), enabling the covalently linked M1 RNA to cleave the mRNA substrate.

One of the most exciting aspects of EGS technology is its programmable specificity. By simply altering the EGS sequence, researchers can redirect RNase P cleavage to virtually any RNA target, utilizing the endogenous RNase P machinery present throughout all stages of the cell cycle [41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. Additionally, the relatively small size of EGS expands the range of viable delivery strategies, such as lipid nanoparticles, which are often unsuitable for bulky RNA-targeting systems. EGS stability and susceptibility to degradation have been reduced through 2′-O-methylation and other chemical modifications [48,49]. While reliance on endogenous RNase P is a key strength of EGS technology, it can also present itself as a vulnerability. Similar to RNAi, EGSs in high concentrations could potentially saturate cellular machinery, interfering with normal RNA processing. Furthermore, the efficiency of RNase P-mediated cleavage may decrease at high EGS concentrations due to limited RNase P availability. Thus, improving delivery methods, stability, optimal dosage, and long-term effects remains a critical area of research for advancing EGS technology towards clinical application.

4.2. M1GS Ribozyme

Building on the target specificity and induced structural mimicry of EGS, the M1GS ribozyme was created by covalently linking a guide sequence (GS) to the catalytic subunit of RNase P, M1 RNA (Figure 2). The linkage of M1 RNA with the GS allows the M1GS ribozyme to function independently from host RNase P. Research has shown that induced proximity improves cleavage efficiency and substrate binding, where the M1GS outperforms the RNase P-EGS system at low concentrations, better reflecting in vivo conditions [21,35,36,50]. M1GS ribozyme activity can be improved in the presence of C5 protein. It can also rely on human RNase P proteins (Rpp) to compensate for the lack of C5 protein, where Rpp proteins enhance activity about 5-fold compared to the 30-fold enhancement provided by C5 [36,37,38]. Although Rpp proteins still enhance M1GS activity, the substantially greater effect seen with C5 indicates that the M1GS is not operating at its full catalytic potential, leaving room for future research on optimizing compatibility between M1GS ribozymes and Rpp proteins.

Figure 2.

Interaction of an M1GS ribozyme with its target mRNA. The M1GS ribozyme consists of a guide sequence (GS) covalently linked to the catalytic M1 RNA from Escherichia coli. When M1GS binds to the target mRNA, it reshapes the mRNA into a portion of a pre-tRNA-like structure through which the M1 RNA detects and subsequently cleaves.

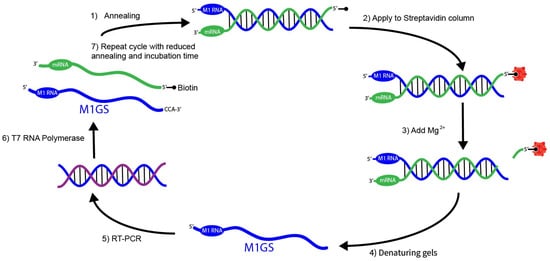

In vitro selection strategies have been successfully used to improve the catalytic efficiency and binding affinity of M1GS ribozymes (Figure 3) [51,52,53,54]. A randomized pool of M1GS variants is generated through mutagenesis. These variants are then incubated with a 5′ biotinylated RNA substrate, allowing properly folded ribozymes to anneal (Figure 3). This mixture is then passed through a streptavidin column that tightly binds to the biotinylated RNA substrate. The column retains the substrate-bound complexes while the unbound or misfolded ribozymes are washed away (Figure 3). Next, ions are introduced, allowing the catalytically active M1GS variants to cleave the substrate, releasing it from the column. These variants are recovered, reverse-transcribed, PCR-amplified, and subjected to additional rounds of selection with progressively shorter annealing and incubation times (Figure 3). This process is repeated until no further improvements are measured. Using this method, researchers evolved M1GS ribozymes targeting a herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) mRNA [53,55]. The resulting variants exhibited a 20-fold increase in catalytic activity and a more than 50-fold increase in binding affinity compared to the wild-type M1GS construct. This variant was tested in infected cells, where its expression led to a 99% reduction in HSV-1 RNA levels and a 98% decrease in the expression levels of the corresponding viral protein [53]. These results not only validate the power of in vitro selection to improve M1GS activity but also confirm that these optimized M1GS ribozymes can retain high activity in human cells.

Figure 3.

In vitro selection of mRNA-cleaving M1GS ribozymes. The in vitro selection procedure for engineering RNase P ribozymes (M1GS) variants that target an mRNA substrate more efficiently begins by generating a randomized ribozyme pool annealed to a biotinylated target mRNA at 37 °C (step 1). This complex is then bound to a streptavidin column (step 2), and activated by the addition of (step 3). Under these in vitro conditions, high concentrations allow the M1 RNA to fold into its catalytic 3D structure without its protein cofactor. Active ribozymes are recovered from denaturing gels (step 4), reverse-transcribed and PCR-amplified (step 5), then transcribed back into M1GS RNA (step 6). The M1GS RNA is reintroduced into subsequent rounds with reduced annealing and incubation times to increase selection stringency (step 7).

5. Application of RNase P to Oncogenic Pathways

5.1. Hepatitis C Virus (HCV)

Hepatitis C (HCV) is one of the leading causes of liver disease [56]. There are over 70 million people worldwide who are chronically infected with HCV, and there are approximately 400,000 deaths per year from HCV-related liver diseases [57]. HCV is a member of the Flavivirus family, which consists of enveloped viruses with positive-sense single-stranded RNA genomes. The genome of HCV consists of a single ~9.5 kb open reading frame, which results in the production of a polyprotein ~3000 amino acids long once translated [56]. The polyprotein is then cleaved into 10 different structural and nonstructural proteins by viral and cellular proteases [58]. HCV exists as a quasispecies, characterized by a population of genetically diverse, closely related variants [59,60]. Despite high sequence variability among the genotypes, structural elements such as the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) remain among the most conserved regions of the HCV genome [60]. Within the UTR of HCV, pre-tRNA-like structures have been identified and shown to be cleaved by host RNase P [60,61,62]. These structures appear to have no measurable impact on the HCV lifecycle, suggesting that they may serve no functional role beyond their resemblance to pre-tRNA [60,61,62]. Nevertheless, RNase P recognition of HCV remains an area of research, with speculation that the tRNA mimicry and cleavage could be involved in viral translation. Importantly, the demonstrated susceptibility of the conserved regions within the HCV genome to RNase P cleavage provides a basis for targeting other conserved RNA regions with M1GS.

The translation of the HCV genome is driven by the highly conserved UTR containing an Internal Ribosome Entry Site (IRES), which allows for cap-independent initiation of translation. The IRES consists of 341 nucleotides, and its secondary structures are formed by domains II and III of the 5′ UTR [63]. The IRES directly recruits the 40S ribosomal subunit and other necessary translation factors, such as eIF3, forgoing the need for an m7G cap [64]. The ability of the HCV IRES to manipulate the host ribosome renders it both essential and highly conserved across all HCV genotypes, making IRES a prime target for antiviral intervention.

Infection with HCV is associated with the development of various types of cancer [56]. For example, it is one of the leading causes of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). HCV core protein is capable of dysregulating various pathways involved in the progression of the cell cycle, promoting cell growth, cell proliferation, and apoptosis, as well as influencing oxidative stress and lipid metabolism [56]. Specifically for the progression of HCC, the pathways of transforming growth factor β (TGF--β), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), Wnt/β--catenin (WNT), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX--2), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) may all be altered by HCV core protein, as well as nonstructural proteins, NS3, NS5A, and NS5B [58]. Chronic infections of HCV can lead to the development of an oncogenic liver environment due to the genetic instability caused by the derailment of pathways due to viral protein expression and other factors, such as persistent liver inflammation [65]. Given IRES’s central role in translation, targeting IRES presents an opportunity to intercept the production of multiple oncogenic HCV proteins at once.

In a study investigating the inhibition of the Hepatitis C virus, researchers designed an M1GS construct targeting the highly conserved internal ribosome entry site (IRES) (Table 1) [66]. By targeting the 5′ untranslated region (UTR), which contains the IRES responsible for initiating translation of HCV’s single mRNA transcript, researchers aimed to suppress the translation of all viral proteins at their shared entry point. The M1GS-HCV/ ribozyme was designed to bind and cleave the IRES along with a catalytically inactive control [66]. After confirming in vitro cleavage, these constructs were expressed in Huh7.5.1 cells (a human hepatoma cell line model for HCV replication). Expression of M1GS-HCV/ led to an ~85% reduction in the expression levels of HCV proteins and a ~1,000-fold decrease in viral growth [66]. These results confirm M1GS’s ability to inhibit HCV replication by intercepting translation, thereby inhibiting a pathway central to HCV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma.

5.2. Kaposi’s Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus (KSHV)

Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), which was discovered more than 30 years ago [67], is a gamma herpesvirus that infects endothelial and B cells [68]. KSHV is the causative agent of several malignancies, including Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), primary effusion lymphoma (PEL), and multicentric Castleman disease (MCD) [67,69]. Characteristic of many herpesviruses, KSHV establishes lifelong latency in host cells, with reactivation triggered by the lytic cycle of the virus [70]. This switch between latency and reactivation is highly regulated, and factors such as cellular stress and immune suppression have been shown to trigger lytic reactivation [48,68]. During lytic replication, KSHV expresses a range of genes that promote angiogenesis, inflammation, and proliferation, all of which contribute to the initiation and progression of tumors [70].

An essential regulator of this switch from latency to lytic reactivation is the immediate-early transcription factor, RTA (replication and transcription activator, also known as ORF50) [71]. RTA is a multifunctional viral transcription factor that activates the expression of viral lytic genes and modulates host pathways involved in apoptosis, immune signaling, and cell cycle control [69,72]. RTA’s essential role in reactivation, along with its contribution to lytic gene expression that facilitates tumorigenesis, makes RTA an ideal target for therapeutic interventions aimed at preventing or suppressing KSHV-associated cancers [68].

In a study aimed at suppressing KSHV lytic gene expression and replication, researchers engineered M1GS ribozymes to cleave RTA mRNA, the initiator of the lytic cycle (Table 1) [73]. Researchers began by identifying accessible regions in the RTA mRNA using dimethyl sulfate (DMS) mapping. After identifying single-stranded, structurally open regions of RTA mRNA, two M1GS constructs were designed for the selected site: F-RTA (catalytically active) and C-RTA (catalytically inactive negative control) [73]. After confirming the in vitro cleavage activity of F-RTA against RTA mRNA, these constructs were tested in human cell lines, BCBL-1 cells (KSHV-infected primary effusion lymphoma cell line) [74]. When expressed in infected cells, F-RTA suppressed RTA levels by 92–94% and viral production by around 250-fold compared to cells expressing C-RTA and M1-TK (sequence specificity control) [73]. These results support the potential of the M1GS ribozyme as a therapeutic target to suppress KSHV reactivation, a critical step in the development and progression of KSHV-associated cancers.

Table 1.

Summary of M1GS Studies.

Table 1.

Summary of M1GS Studies.

| Target | Target RNA Region | Model System | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCV | 5′ UTR containing IRES | Huh7.5.1 cells | 85% reduction in HCV protein level and ~1000-fold decrease in viral growth [66] |

| KSHV | RTA mRNA | BCBL-1 cells | Suppression of RTA levels by 92–94% and viral production by 250-fold [73] |

| BCR-ABL | Fusion junction region of BCR-ABL mRNA | IL-3-dependent Ba/F3cells (BCR-ABL positive) | 91–95% reduction in cell viability [22] |

5.3. BCR-ABL Oncogene in Leukemias

The BCR-ABL oncogene is a prevalent mutation found in patients with leukemia, most commonly in those with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) [75]. The oncogene generates the BCR-ABL fusion protein, due to the reciprocal translocation of segments between chromosomes 9 and 22 [75]. More specifically, the segment containing the ABL gene on chromosome 9 is translocated to the breakpoint cluster region (BCR) gene on chromosome 22. The resulting chimeric chromosome is known as the Philadelphia chromosome (Ph) [75].

The BCR-ABL fusion protein exhibits abnormally elevated tyrosine kinase activity. This constitutively active tyrosine kinase induces numerous downstream effects that promote cell proliferation, resistance to apoptosis, genomic instability, and altered cell differentiation and adhesion [76,77]. The kinase activity in BCR-ABL results in the autophosphorylation of Tyr177, located in BCR, which is a major binding site for GRB2, a significant component of the RAS and PI3K pathways. This promotes proliferation and reduces apoptosis, respectively [75].

In a study aimed at targeting the BCR-ABL oncogene, researchers constructed M1GS ribozymes designed to target the unique mRNA junctions created by the BCR-ABL fusion (Table 1) [22]. Two M1GS ribozymes, p190 and p210, were designed to target the exon-exon junctions specific to the major BCR-ABL fusion transcripts (e1a2 in p190 and b2a2 or b3a2 in p210) [22,78]. These ribozymes were expressed in IL-3-dependent Ba/F3 cells engineered to express either the p190 or p210 BCR-ABL fusion protein. In this model, cell survival was dependent on BCR-ABL’s kinase activity. Ribozyme efficiency was evaluated based on the loss of cell viability, which reflects the successful knockdown of BCR-ABL. Expression of the M1GS constructors reduced cell viability by ~95% in p190-expressing cells and ~91% in p210-expressing cells [22]. These findings confirm the M1GS ribozyme’s ability to selectively cleave BCR-ABL fusion transcripts, resulting in a decrease in leukemia cell viability.

6. Advantages and Disadvantages

M1GS ribozymes offer a highly specific, modular, and efficient strategy for targeting oncogenic transcripts. M1GS relies on precise base pairing between a customizable guide sequence and the target RNA to form a pre-tRNA-like structure that can be recognized and cleaved by M1 RNA (Table 2) [9,22]. This structural requirement offers high specificity and minimizes off-target cleavage, a significant advantage over RNase H and other antisense approaches, which can tolerate mismatches arising from non-Watson–Crick base pairing, transient secondary structures, or short stretches of partial complementarity [79,80,81]. Therapeutic potency is enhanced due to M1GS’s catalytic nature, allowing each ribozyme to cleave multiple targets without being consumed in the process. Lastly, the most compelling strength of M1GS is their adaptability, as they can be readily retargeted to diverse transcripts, as demonstrated by their effectiveness against the cellular BCR-ABL oncogene and viral transcripts from HCV and KSHV [22,66,73].

Table 2.

Advantages and Disadvantages of M1GS.

Several limitations remain when considering the clinical application of M1GS ribozymes (Table 2). M1GS activity depends on the accessibility of the target RNA and the correct folding of the resulting M1GS and target RNA complex. Both processes can be disrupted by physiological conditions such as pH, ion concentrations, or target site mutations. Due to M1GS’s reliance on secondary and tertiary structural mimicry, common chemical modifications used to enhance RNA stability in other nucleic acid therapeutics must be carefully considered to avoid impairing catalytic activity [80,82]. Additionally, the relatively large size of the M1GS ribozyme poses a significant challenge for delivery. Current studies and research have used plasmid-based expression in cultured cells, an approach that may not be translatable to clinical settings [21,83]. As a result, in vivo applications often depend on viral vectors or tailored strategies to the disease context. For example, past studies have shown that Salmonella can be used as a vector for macrophage-targeted M1GS delivery against human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infection [84]. Such tailored delivery methods undermine the broad adaptability that makes M1GS a compelling candidate as a platform for diverse therapeutic applications.

7. Future Direction and Challenges

First, future studies should prioritize optimizing the compatibility between the M1GS ribozymes and human RNase P protein (RPPs). Currently, catalytic effectiveness is limited by the ability of RPPs to functionally compensate for the bacterial C5 protein that stabilizes M1 RNA and enhances substrate recognition [36,37,38]. This could be approached using in vitro selection strategies, as discussed in earlier sections, to identify M1GS variants that function more effectively with RPPs [53,54].

Another key direction in M1GS research is improving delivery. Given that delivery is a common challenge shared across the field of synthetic biology, advances in related RNA-based therapeutics may similarly accelerate the development of effective delivery strategies for M1GS. For example, past work with external guide sequences has demonstrated that substituting nuclease-resistant 2′-O-methyl oligoribonucleotides at all positions except the critical residues in the loop yields oligomers that remain stable in 50% human serum for 24 h [49]. M1GS constructs use a similar guide sequence structure, and because M1GS are essentially formed by covalently linking an EGS to M1 RNA, these same chemical modifications may apply to M1GS designs without disrupting function. If successful, these modifications could improve resistance to degradation. However, experiments need to be conducted to confirm that these modifications would not substantially affect M1GS catalytic activity. Beyond chemical stabilization, the delivery challenges of M1GS constructs could be addressed by developing new delivery methods. This may include novel, broad delivery methods or context-specific strategies that utilize tissue targeting or design vectors tailored to the cellular environment of a particular cancer. Another approach is to reduce the overall size of the M1GS constructs. Previous studies have defined optimal guide sequence lengths, suggesting that minimization of M1 RNA may be possible [36]. However, reducing M1 RNA size could impair its catalytic activity and essential interactions with RPPs, so any such modifications must be carefully evaluated in cultured human cells.

Next, future studies should investigate the potential of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) as viable targets for M1GS. Many ncRNAs regulate a variety of biological processes, including gene expression, chromatin architecture, metabolism, and RNA processing [85]. These ncRNAs can become cancer-associated either through mutations that alter structure and function or through dysregulation in expression [85]. Future studies could investigate M1GS constructs that directly target oncogenic or overexpressed ncRNAs. Importantly, therapeutic strategies targeting ncRNAs have already been demonstrated to be effective. Miravirsen, an ASO designed to inhibit the liver-specific microRNA miR-122, demonstrated antiviral activity against HCV by targeting miR-122, an ncRNA necessary for HCV replication [86]. Miravirsen establishes a strong precedent for M1GS as an ncRNA inhibitor. Cancer cells, compared to normal cells, are more reliant on metabolic processes to support their rapid growth and survival [87]. Many cancer therapeutics have been developed to exploit these heightened metabolic processes in cancer cells. For example, 2-Deoxy-D-glucose, a glucose analog, has been used to inhibit glycolysis and induce cell death in leukemic cell lines [88]. M1GS constructs could be developed similarly to target non-mutated ncRNAs that cancer cells are disproportionately reliant on. One such target is HULC, an ncRNA that enhances glycolysis by stabilizing lactate dehydrogenase A and pyruvate kinase M2 [89].

Finally, future studies should explore targeting oncogenic transcripts beyond those explored in HCV, KSHV, and BCR-ABL, as well as other cancer-associated RNAs that could be suitable for M1GS intervention. For example, many malignancies are driven by aberrant splicing of key regulatory genes such as DNMT3B, BRCA1, and KLF6 [90]. These aberrant transcripts represent promising targets for M1GS-mediated silencing, as they can be selectively cleaved without affecting normal gene expression. Different cancers and individual tumors may have unique splicing profiles, allowing for the use of M1GS ribozymes to provide tailored therapies that selectively target patient-specific oncogenic transcripts. The adaptability of M1GS positions it as a versatile tool not only for combinational knockdowns aimed at disrupting multiple oncogenic pathways but also for investigating the roles of specific transcripts in cancer initiation, progression, and resistance.

8. Conclusions

In this review, we have discussed the design, mechanism, and therapeutic potential of M1GS ribozymes as a tool for targeting transcripts in cancer. We have highlighted the gene-targeting activity of the engineered RNase P ribozyme and how it can be optimized through in vitro selection. We highlighted key studies demonstrating the effectiveness of M1GS constructs against the BCR-ABL oncogene and viral transcripts from HCV and KSHV, illustrating the versatility of these constructs across diverse cancer contexts. M1GS operates solely at the RNA level, offering catalytic turnover, minimal off-target effects, and ease of engineering. Despite these advantages, challenges such as delivery limitations, reduced effectiveness in the absence of C5 protein, and stability issues must be addressed before clinical applications can be realized. We have discussed future directions in research, including improving compatibility with human RNase P proteins, optimizing chemical stability, exploring new delivery strategies, and expanding the range of targets. Ultimately, M1GS represents a promising synthetic biology platform capable of serving both as a precision therapeutic and a powerful tool for probing transcripts in cancer biology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.S., E.O. and F.L.; methodology, T.S., E.O. and F.L.; validation, T.S., E.O. and F.L.; formal analysis, T.S., E.O. and F.L.; investigation, T.S., E.O. and F.L.; data curation, T.S., E.O. and F.L.; writing—original draft preparation, T.S., E.O. and F.L.; writing—review and editing, T.S., E.O. and F.L.; supervision, F.L.; project administration, F.L.; funding acquisition, F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We would also like to thank Robert and Colleen Haas for their generous support. T.S. is a Fellow of the Haas Scholars Program. The study has been supported by a Start-Up Fund (University of California at Berkeley).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Phong Trang for critical comments, insightful discussions, and editorial assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| M1GS | M1 RNA with a guide sequence |

| RNase P | Ribonuclease P |

| tRNA | Transfer RNA |

| GS | Guide Sequence |

| siRNA | Small interfering RNAs |

| RNAi | RNA interference |

| ZFN | Zinc finger nucleases |

| TALENs | Transcription activator-like effector nucleases |

| CRISPR/Cas9 | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats/CRISPR-associated protein |

| PAM | Protospacer Adjacent Motif |

| Rpp | Human RNase P protein |

| EGS | External Guide Sequences |

| ASO | Antisense oligonucleotides |

| HSV-1 | Herpes simplex virus 1 |

| HCV | Hepatitis C Virus |

| UTR | Untranslated region |

| IRES | Internal Ribosome Entry Site |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| TGFβ | Transforming growth factor β |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| WNT | Wnt/β-catenin |

| PPARα | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α |

| KSHV | Kaposi’s Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus |

| KS | Kaposi’s Sarcoma |

| PEL | Primary effusion lymphoma |

| MCD | Multicentric Castleman disease |

| RTA | Replication and transcription activator |

| DMS | Dimethyl sulfate |

| BCR-ABL | Breakpoint Cluster Region gene fused with the Abelson gene |

| CML | Chronic myeloid leukemia |

| Ph | Philadelphia Chromosome |

| ncRNA | Noncoding RNAs |

| miRNA | microRNA |

References

- Brown, J.S.; Amend, S.R.; Austin, R.H.; Gatenby, R.A.; Hammarlund, E.U.; Pienta, K.J. Updating the Definition of Cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 2023, 21, 1142–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaneda, M.; den Hollander, P.; Kuburich, N.A.; Rosen, J.M.; Mani, S.A. Mechanisms of cancer metastasis. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 87, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruebo, M.; Vilaboa, N.; Sáez-Gutierrez, B.; Lambea, J.; Tres, A.; Valladares, M.; González-Fernández, A. Assessment of the evolution of cancer treatment therapies. Cancers 2011, 3, 3279–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, I.S.; Smart, E. Chemotherapy-Induced Hair Loss: The Use of Biomarkers for Predicting Alopecic Severity and Treatment Efficacy. Biomark. Insights 2019, 14, 1177271919842180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuel, S.L. Targeted cancer therapies: Clinical pearls for primary care. Can. Fam. Physician 2022, 68, 515–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopalan, V.; Vioque, A.; Altman, S. RNase P: Variations and uses. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 6759–6762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirsebom, L.A.; Liu, F.; McClain, W.H. The discovery of a catalytic RNA within RNase P and its legacy. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 107318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Liu, F. Inhibition of gene expression in human cells using RNase P-derived ribozymes and external guide sequences. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1769, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wooddell, C.I.; Rozema, D.B.; Hossbach, M.; John, M.; Hamilton, H.L.; Chu, Q.; Hegge, J.O.; Klein, J.J.; Wakefield, D.H.; Oropeza, C.E.; et al. Hepatocyte-targeted RNAi therapeutics for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Mol. Ther. 2013, 21, 973–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffrey, D.R.; Zhao, J.; Song, Z.; Schaffer, M.E.; Haney, S.A.; Subramanian, R.R.; Seymour, A.B.; Hughes, J.D. siRNA off-target effects can be reduced at concentrations that match their individual potency. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scacheri, P.C.; Rozenblatt-Rosen, O.; Caplen, N.J.; Wolfsberg, T.G.; Umayam, L.; Lee, J.C.; Hughes, C.M.; Shanmugam, K.S.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Meyerson, M.; et al. Short interfering RNAs can induce unexpected and divergent changes in the levels of untargeted proteins in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 1892–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maepa, M.B.; Roelofse, I.; Ely, A.; Arbuthnot, P. Progress and Prospects of Anti-HBV Gene Therapy Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 17589–17610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modell, A.E.; Lim, D.; Nguyen, T.M.; Sreekanth, V.; Choudhary, A. CRISPR-based therapeutics: Current challenges and future applications. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 43, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Zhang, P.; Yan, Y.; Yu, C.; Jiang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, D. Expanding the range of CRISPR/Cas9-directed genome editing in soybean. aBIOTECH 2022, 3, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelling, M.A.; Nguyen, G.T.; Sashital, D.G. CRISPR-Cas effector specificity and cleavage site determine phage escape outcomes. PLoS Biol. 2023, 21, e3002065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, S.; Kang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Yi, M. Harnessing the evolving CRISPR/Cas9 for precision oncology. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, N.; Li, L.; Wang, X. Molecular mechanisms, off-target activities, and clinical potentials of genome editing systems. Clin. Transl. Med. 2020, 10, 412–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M.G.; Smekalova, E.; Combe, E.; Gregoire, F.; Zoulim, F.; Testoni, B. Gene Editing Technologies to Target HBV cccDNA. Viruses 2022, 14, 2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrier-Takada, C.; Gardiner, K.; Marsh, T.; Pace, N.; Altman, S. The RNA moiety of ribonuclease P is the catalytic subunit of the enzyme. Cell 1983, 35, 849–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Zhang, I.; Trang, P.; Liu, F. Engineering of RNase P Ribozymes for Therapy against Human Cytomegalovirus Infection. Viruses 2024, 16, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobaleda, C.; Sánchez-García, I. In vivo inhibition by a site-specific catalytic RNA subunit of RNase P designed against the BCR-ABL oncogenic products: A novel approach for cancer treatment. Blood 2000, 95, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, D.N.; Pace, N.R. Ribonuclease P: Unity and diversity in a tRNA processing ribozyme. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998, 67, 153–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Scott, F.; Fierke, C.A.; Engelke, D.R. Eukaryotic ribonuclease P: A plurality of ribonucleoprotein enzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2002, 71, 165–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatta, A.; Dienemann, C.; Cramer, P.; Hillen, H.S. Structural basis of RNA processing by human mitochondrial RNase P. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2021, 28, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarrous, N.; Liu, F. Human RNase P: Overview of a ribonuclease of interrelated molecular networks and gene-targeting systems. RNA 2023, 29, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, N.J.; Osterman, A.; Torres-Larios, A.; Swinger, K.K.; Pan, T.; Mondragón, A. Structure of a bacterial ribonuclease P holoenzyme in complex with tRNA. Nature 2010, 468, 784–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Huang, W.; Zhao, J.; Huynh, L.; Taylor, D.J.; Harris, M.E. Structural and mechanistic basis for recognition of alternative tRNA precursor substrates by bacterial ribonuclease P. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crary, S.M.; Niranjanakumari, S.; Fierke, C.A. The protein component of Bacillus subtilis ribonuclease P increases catalytic efficiency by enhancing interactions with the 5′ leader sequence of pre-tRNAAsp. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 9409–9416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalan, V.; Baxevanis, A.D.; Landsman, D.; Altman, S. Analysis of the functional role of conserved residues in the protein subunit of ribonuclease P from Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 1997, 267, 818–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, J.; Andrews, A.J.; Fierke, C.A. Roles of protein subunits in RNA-protein complexes: Lessons from ribonuclease P. Biopolymers 2004, 73, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.J.; Kilani, A.F.; Zhan, X.; Altman, S.; Liu, F. The protein cofactor allows the sequence of an RNase P ribozyme to diversify by maintaining the catalytically active structure of the enzyme. RNA 1997, 3, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kurz, J.C.; Niranjanakumari, S.; Fierke, C.A. Protein component of Bacillus subtilis RNase P specifically enhances the affinity for precursor-tRNAAsp. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 2393–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niranjanakumari, S.; Stams, T.; Crary, S.M.; Christianson, D.W.; Fierke, C.A. Protein component of the ribozyme ribonuclease P alters substrate recognition by directly contacting precursor tRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 15212–15217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhof, E.; Wesolowski, D.; Altman, S. Mapping in three dimensions of regions in a catalytic RNA protected from attack by an Fe(II)-EDTA reagent. J. Mol. Biol. 1996, 258, 600–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, F.; Altman, S. Inhibition of viral gene expression by the catalytic RNA subunit of RNase P from Escherichia coli. Genes. Dev. 1995, 9, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.; Ben-Asouli, Y.; Schein, A.; Moussa, S.; Jarrous, N. Eukaryotic RNase P: Role of RNA and Protein Subunits of a Primordial Catalytic Ribonucleoprotein in RNA-Based Catalysis. Mol. Cell 2003, 12, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharin, E.; Schein, A.; Mann, H.; Ben-Asouli, Y.; Jarrous, N. RNase P: Role of distinct protein cofactors in tRNA substrate recognition and RNA-based catalysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 5120–5132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, A.C.; Altman, S. External guide sequences for an RNA enzyme. Science 1990, 249, 783–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClain, W.H.; Guerrier-Takada, C.; Altman, S. Model substrates for an RNA enzyme. Science 1987, 238, 527–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Wesolowski, D.; Alonso, D.; Deitsch, K.W.; Ben Mamoun, C.; Altman, S. Targeting protein translation, RNA splicing, and degradation by morpholino-based conjugates in Plasmodium falciparum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 11935–11940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrier-Takada, C.; Li, Y.; Altman, S. Artificial regulation of gene expression in Escherichia coli by RNase P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 11115–11119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesolowski, D.; Alonso, D.; Altman, S. Combined effect of a peptide–morpholino oligonucleotide conjugate and a cell-penetrating peptide as an antibiotic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 8686–8689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinney, J.; Guerrier-Takada, C.; Wesolowski, D.; Altman, S. Inhibition of Escherichia coli viability by external guide sequences complementary to two essential genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 6605–6610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinney, J.S.; Zhang, H.; Kubori, T.; Galán, J.E.; Altman, S. Disruption of type III secretion in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium by external guide sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 848–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesolowski, D.; Tae, H.S.; Gandotra, N.; Llopis, P.; Shen, N.; Altman, S. Basic peptide-morpholino oligomer conjugate that is very effective in killing bacteria by gene-specific and nonspecific modes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 16582–16587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Hwang, E.S.; Altman, S. Targeted cleavage of mRNA by human RNase P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 8006–8010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Trang, P.; Kim, K.; Zhou, T.; Deng, H.; Liu, F. Effective inhibition of Rta expression and lytic replication of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus by human RNase P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 9073–9078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Benimetskaya, L.; Lebedeva, I.; Dignam, J.; Takle, G.; Stein, C.A. Intracellular mRNA cleavage induced through activation of RNase P by nuclease-resistant external guide sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000, 18, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guerrier-Takada, C.; Altman, S. Targeted cleavage of mRNA in vitro by RNase P from Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 3185–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, G.F. Directed molecular evolution. Sci. Am. 1992, 267, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szostak, J.W. In vitro genetics. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1992, 17, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilani, A.F.; Trang, P.; Jo, S.; Hsu, A.; Kim, J.; Nepomuceno, E.; Liou, K.; Liu, F. RNase P ribozymes selected in vitro to cleave a viral mRNA effectively inhibit its expression in cell culture. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 10611–10622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, P.; Zhang, I.; Liu, F. In Vitro Amplification and Selection of Engineered RNase P Ribozyme for Gene Targeting Applications. Methods Mol. Biol. 2024, 2822, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, H.; Lee, J.; Kilani, A.F.; Kim, K.; Trang, P.; Kim, J.; Liu, F. Engineered RNase P ribozymes increase their cleavage activities and efficacies in inhibiting viral gene expression in cells by enhancing the rate of cleavage and binding of the target mRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 32063–32070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chigbu, D.I.; Loonawat, R.; Sehgal, M.; Patel, D.; Jain, P. Hepatitis C Virus Infection: Host-Virus Interaction and Mechanisms of Viral Persistence. Cells 2019, 8, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negro, F. Natural History of Hepatic and Extrahepatic Hepatitis C Virus Diseases and Impact of Interferon-Free HCV Therapy. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2020, 10, a036921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudvand, S.; Shokri, S.; Taherkhani, R.; Farshadpour, F. Hepatitis C virus core protein modulates several signaling pathways involved in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, E.; Perales, C. Viral quasispecies. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1008271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadal, A.; Martell, M.; Lytle, J.R.; Lyons, A.J.; Robertson, H.D.; Cabot, B.; Esteban, J.I.; Esteban, R.; Guardia, J.; Gómez, J. Specific cleavage of hepatitis C virus RNA genome by human RNase P. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 30606–30613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, A.J.; Robertson, H.D. Detection of tRNA-like structure through RNase P cleavage of viral internal ribosome entry site RNAs near the AUG start triplet. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 26844–26850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piron, M.; Beguiristain, N.; Nadal, A.; Martínez-Salas, E.; Gómez, J. Characterizing the function and structural organization of the 5′ tRNA-like motif within the hepatitis C virus quasispecies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 1487–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, H.; Collier, M.; Loerke, J.; Ismer, J.; Schmidt, A.; Hilal, T.; Sprink, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Mielke, T.; Bürger, J.; et al. Molecular architecture of the ribosome-bound Hepatitis C Virus internal ribosomal entry site RNA. Embo J. 2015, 34, 3042–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukavsky, P.J. Structure and function of HCV IRES domains. Virus Res. 2009, 139, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virzì, A.; Roca Suarez, A.A.; Baumert, T.F.; Lupberger, J. Oncogenic Signaling Induced by HCV Infection. Viruses 2018, 10, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Li, X.; Mao, X.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, W.; Wu, J.; Li, G. Inhibition of hepatitis C virus by an M1GS ribozyme derived from the catalytic RNA subunit of Escherichia coli RNase P. Virol. J. 2014, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Cesarman, E.; Pessin, M.S.; Lee, F.; Culpepper, J.; Knowles, D.M.; Moore, P.S. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. Science 1994, 266, 1865–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damania, B.; Cesarman, E. Kaposi’s Sarcoma Herpesvirus. In Fields Virology: DNA Viruses, 7th ed.; Knipe, D.M., Howley, P., Eds.; Wolters Kluwer Health, Lippincott and Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 513–572. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, K.W.; Damania, B. Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV): Molecular biology and oncogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2010, 289, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganem, D. KSHV infection and the pathogenesis of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2006, 1, 273–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, R.; Lin, S.F.; Gradoville, L.; Yuan, Y.; Zhu, F.; Miller, G. A viral gene that activates lytic cycle expression of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 10866–10871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purushothaman, P.; Uppal, T.; Sarkar, R.; Verma, S.C. KSHV-Mediated Angiogenesis in Tumor Progression. Viruses 2016, 8, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.C.; Yan, B.; Liu, F. Suppressing Kaposi’s Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Lytic Gene Expression and Replication by RNase P Ribozyme. Molecules 2023, 28, 3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renne, R.; Zhong, W.; Herndier, B.; McGrath, M.; Abbey, N.; Kedes, D.; Ganem, D. Lytic growth of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) in culture. Nat. Med. 1996, 2, 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, M.; Griffin, J.D. Molecular mechanisms of transformation by the BCR-ABL oncogene. Semin. Hematol. 2003, 40, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintás-Cardama, A.; Cortes, J. Molecular biology of bcr-abl1-positive chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood 2009, 113, 1619–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaraj, P.; Singh, H.; Niu, N.; Chu, S.; Holtz, M.; Yee, J.K.; Bhatia, R. Effect of mutational inactivation of tyrosine kinase activity on BCR/ABL-induced abnormalities in cell growth and adhesion in human hematopoietic progenitors. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 5322–5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, S.S.; Greene, J.M.; McConnell, T.S.; Willman, C.L. Pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia with b3a2 (p210) and e1a2 (p190) BCR-ABL fusion transcripts relapsing as chronic myelogenous leukemia with a less differentiated b3a2 (p210) clone. Leukemia 1999, 13, 2007–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Scherer, L.J.; Rossi, J.J. Approaches for the sequence-specific knockdown of mRNA. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 1457–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparmann, A.; Vogel, J. RNA-based medicine: From molecular mechanisms to therapy. EMBO J. 2023, 42, e114760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, C.A.; Cheng, Y.C. Antisense oligonucleotides as therapeutic agents—Is the bullet really magical? Science 1993, 261, 1004–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Eckstein, F. Modified oligonucleotides: Synthesis and strategy for users. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998, 67, 99–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnett, J.C.; Rossi, J.J. RNA-based therapeutics: Current progress and future prospects. Chem. Biol. 2012, 19, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Li, H.; Vu, G.-P.; Gong, H.; Umamoto, S.; Zhou, T.; Lu, S.; Liu, F. Salmonella-mediated delivery of RNase P-based ribozymes for inhibition of viral gene expression and replication in human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 7269–7274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Dragomir, M.P.; Yang, C.; Li, Q.; Horst, D.; Calin, G.A. Targeting non-coding RNAs to overcome cancer therapy resistance. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottosen, S.; Parsley Todd, B.; Yang, L.; Zeh, K.; van Doorn, L.-J.; van der Veer, E.; Raney Anneke, K.; Hodges Michael, R.; Patick Amy, K. In Vitro Antiviral Activity and Preclinical and Clinical Resistance Profile of Miravirsen, a Novel Anti-Hepatitis C Virus Therapeutic Targeting the Human Factor miR-122. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 59, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tufail, M.; Jiang, C.H.; Li, N. Altered metabolism in cancer: Insights into energy pathways and therapeutic targets. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, N.V.; Knudsen, J.H.; Laustsen, C.; Bertelsen, L.B. The effect of 2-Deoxy-D-glucose on glycolytic metabolism in acute myeloblastic leukemic ML-1 cells. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Yan, S.; Wang, H.; Shao, X.; Xiao, M.; Yang, B.; Qin, G.; Kong, R.; Chen, R.; et al. Interactome analysis reveals that lncRNA HULC promotes aerobic glycolysis through LDHA and PKM2. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fackenthal, J.D.; Godley, L.A. Aberrant RNA splicing and its functional consequences in cancer cells. Dis. Model. Mech. 2008, 1, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).