Abstract

The static topology of surface characteristics and active sites in catalysis overlooks a crucial element: the dynamic processes of optimal pattern formation over time and the creation of intermediate structures that enhance reactions. Nature’s principle of coupling reaction and motion in catalytic processes by enzymes or higher organisms offers a new perspective. This work explores a novel theoretical approach by adding the time dimension to optimise topological variations using the Maximum Entropy Production (MEP) assumption. This approach recognises that the catalyst surface is not an unchanging energy landscape but can change dynamically. The time-dependent transport problem of molecules is here interpreted by a non-equilibrium model used for modelling and predicting dynamic pattern formation in excitable media, a class of active matter requiring an activation threshold. We present a nonlocal reaction–cross-diffusion (RXD) formulation of catalytic reactions that can capture the catalyst’s interaction with the target molecule in space and time. The approach provides a theoretical basis for future deep learning models and multiphysics upscaling of catalysts and their support structures across multiphysics fields. The particular advantage of the RXD approach is that it allows each scale to investigate dynamic pattern-forming processes using linear and nonlinear stability analysis, thus establishing a rule base for developing new catalysts.

1. Introduction

Current catalysts research optimizes the static topology of surface properties and active sites through rational design involving (i) physicochemical techniques to analyze catalyst structure, composition, and interaction with target molecules; (ii) computational simulation of reaction processes and catalyst behaviour; and (iii) machine learning algorithms to identify patterns and relationships between catalyst properties and performance [1]. Novel research is also directed toward high-throughput methodologies that allow for the rapid evaluation of catalyst libraries. However, these methods are still facing challenges in library design and the incorporation of complex factors into computational models. Another new trend is the development of bioinspired catalysts in which porous crystalline materials such as metal–organic frameworks and covalent organic frameworks mimic enzymes. Nonetheless, they still struggle to replicate their complex structures and functionalities [2] precisely.

We address these problems by exploring a novel theoretical approach by adding the time dimension to optimising topological variations using the Maximum Entropy Production (MEP) assumption. The vital role of the spatial dynamics of the catalytic reaction has already been explored in one-step catalytic reactions in enzymes [3]. By adding the time dimension to optimising topological variations, this approach acknowledges that the catalyst surface is not an unchanging energy landscape but can change dynamically. Accordingly, in the biological equivalent, enzymatic reactions can generate significant feedback from enzyme transport [3]. These biocatalysts form spontaneous spatial patterns that bind to target molecules, weaken existing bonds, and position them favourably for the reaction, reducing the energy required for bond breakage and rearrangement during the reaction. Given this, spontaneous pattern formation processes may also be involved in forming intermediates, where catalysts participate in the reaction by forming temporary chemical bonds with the target molecules. This preorganisation is known as synergistic catalytic reactions. Synergistic catalysis combines two distinct cocatalysts that work together to carry out a reaction that would not be possible using either cocatalyst alone. These intermediate complexes could hold the target molecules in a configuration that facilitates bond breaking and formation, lowering the activation energy. For example, 190 times better turnover has been reported for DNA-scaffold synergistic catalysts [4]. Once the reaction is complete, the catalyst eventually releases the products and is free to bind to new target molecules, acting like a reusable key.

The rates and mechanisms of catalytic reactions depend on these dynamic processes, including how strongly and in what orientation the target molecules bind to the surface. A dynamic approach must answer how reactants move across the surface to encounter active sites. Another question is how the product molecules leave the surface after the reaction. We hypothesise that the static topology of surface properties and active sites in catalysis misses an important aspect: the dynamic transport processes of optimal pattern formation that occur over time and the formation of intermediate structures that accelerate the reactions. Answering these questions may help resolve some of the issues we face in rational catalysis design. The future might also hold discoveries about the role of specific dynamic patterns, as reported for the biological equivalent [3]. Data-driven models provide the training set for deep learning in machine learning algorithms and have achieved excellent predictive performance for the case of optimising cross-coupling reactions for the catalysis of carbon-carbon bonds [5]. In this paper, we develop the idea further and propose a fundamental theory for spatio-temporal pattern forecasting based on a reaction–diffusion formulation. Thus, we can define rules based on the Maximum Entropy Production (MEP) principle, which governs how the system evolves using the reaction and diffusion coefficients. This simple mathematical framework allows one to investigate catalytic pattern-forming processes using linear and weakly nonlinear stability analysis [6,7]. The approach supplies a theoretical basis for future deep learning models and computational upscaling of the catalyst’s molecular dynamics and density functional models.

2. Materials and Methods

An Active-Matter-Inspired Approach

The current research on rational design uses a static concept of catalysts with fixed active sites and surface properties where reactions can occur. The focus is on optimising the properties of these sites to enhance the reaction rates and selectivity and lower the activation threshold for reactions to occur. The concept of intermediate catalytic products with self-healing or self-assembly is also considered in synergistic catalysis; however, their dynamic evolution still lacks a comprehensive theoretical basis.

Biomimicry, inspired by nature’s efficient enzymes, offers a path forward. New experiments have shown that enzymes exhibit active matter features, meaning that they can move independently and influence their surroundings [8]. High-resolution microscopy revealed that enzymes undergo rapid, ballistic leaps for a few microseconds when actively converting the substrate molecule they work on. This observation makes their overall movement super-diffusive during the short jumps, increasing the effective diffusion over longer time scales. Interestingly, these enzyme jumps are more frequent at high substrate concentrations but propel the enzymes toward areas with lower substrate levels. This active directional jump behaviour works as a chemo-repellent, in the opposite direction to chemo-attraction, which describes the regular interaction between cells of organisms and the gradient of substrate molecules upon which they work. These cells regularly prefer regions with a higher concentration of their substrates (chemotaxis). In the case of enzymes, their biased random walk allows them to encounter and bind with their targets in the opposite direction (antichemotaxis) more efficiently, facilitating catalytic reactions. The finding of the tight coupling of chemical reactions and movement of the catalyst increases the overall reaction rate with the substrate molecule, suggesting that reaction–motion coupling is a general principle of catalysis. The biased random walk of catalysts is a well-known feature of active matter composed of self-propelled or responsive components that can convert energy into motion at the microscopic scale.

Active matter defines a broad class of non-equilibrium systems composed of microscopic, self-propelled, self-assembling, and energy-consuming components. Examples include swimming bacteria, bird flocks, people movement, synthetic microbots, and gels [9]. Their inherent activity can lead to continuous interactions and collective motion by constantly exchanging energy with their surroundings. The unexpected jump-like behaviour of enzymes towards lower concentrations of the target molecules [8] exemplifies the non-equilibrium behaviour. However, the detailed mechanism of the biased random walk of enzymes toward their chemo-attractants differs from that of swimming bacteria. The latter have chemo-receptors and use them in their random walk to frequently change direction towards these chemo-attractors through a whip-like motion of their hair-like appendages (flagella). In the case of enzymes, biased random motion is more direct and is directly coupled to the catalytic cross-reactions with their targets and the self- and cross-diffusion of the substrate they work upon. These chemical conversions give rise to new stochastic trajectories [10].

Additionally, the required activation of a chemical reaction and the unusual non-equilibrium behaviour of enzymes suggest that catalysis requires a threshold-based excitation level before turning into a subclass of active matter and acting as a classical excitable medium, constantly exchanging energy with their surroundings to maintain their active state [11]. Excited matter can exhibit spreading or standing waves of excitation under specific conditions. The mathematical theory for modelling the rich excitation wave phenomena in the excitable matter is based on a reaction–diffusion Ansatz. In addition to the classical dynamic pattern-forming mechanism of reaction–self-diffusion systems, it incorporates the effect of cross-diffusion between the gradient of one species and the flux of the other, including the reverse feedback. The role of reaction–cross-diffusion (RXD) mass-transfer for pattern-forming processes has initially been identified in theoretical biology where it was found that a simple catalytic reaction, when associated with a small cross-diffusion phenomenon, can lead to the formation of new patterns [12].

The cross-diffusion theory describes dynamic pattern-forming mechanisms in living systems. A generalisation of the approach to non-biological chemical systems (and other systems, e.g., social systems) has also been suggested [13]. The work led to renewed interest and started a systematic investigation of the cross-diffusion phenomenon, which allowed the identification of the rich solution space, including the identification of cross-diffusion waves as a new class of excitation waves [14,15]. The original analysis for chemical systems [13] used a Fickian reaction–diffusion formulation of the following generic form:

where the vector consists of the concentrations of the N species, is the reaction term (not necessarily linear), and is the self-diffusion coefficient of the ith species and represent the cross-diffusion coefficients.

3. Multiphysics for Upscaling of Catalytic Reactions

The industrial-scale use of carbon-based catalysts may allow us to address the current climate crisis, which requires efficient processes to handle diverse chemical components. Biomimicry seeks inspiration for energy-efficient catalytic processes at lower temperatures and pressures, drawing inspiration from enzymes. However, enzymes might not be practical for large-scale use. Instead, new catalyst designs based on enzyme principles will be crucial, and advanced techniques are needed to create catalytic structures networked over multiple scales, mimicking enzyme reaction environments for efficient and selective conversion of target molecules. The study of how enzymes lower the energy needed for reactions suggests a general principle: catalysts might move towards target molecules to optimise their efficiency. Inspired by nature’s selection, this approach could lead to new catalyst designs; however, the current catalyst design theory appears inadequate. Current models based on individual atoms (bottom–up) do not match well with experiments looking at larger scales (top–down); accordingly, the challenge for theory development is to provide mesoscopic models that offer a middle ground between atomic and experimental scales [16]. These mesoscale models can help us develop catalysts that work effectively under different conditions beyond the limitations of static energy considerations.

The mesoscopic RXD model offers a link, trading off integration for accuracy and detail. Although not capturing fine-grained details, RXD excels in handling the space–time interactions of catalytic structures by accounting for flexible structures, nonlocal diffusion between distant molecules, and reactions with surrounding molecules. This focus on entropy makes the RXD approach particularly valuable for scaling-up catalyst support structures from the molecular level to industrial applications. Across these scales, hierarchical catalyst structures experience multiphysics loads (thermal, hydraulic, mechanical, chemical, and electrical, THMCE) with varying diffusion lengths. These loads can be described as generalised thermodynamic forces, and their interaction with diffusive fluxes determines the entropy production. The RXD approach allows for the calculation of these external factors, which is crucial for optimising catalyst reactions across multiple scales. This optimisation is achieved by applying RXD equations at different scales, from the molecular level to industrial processes. This multiscale approach considers various physical forces (THMCE). It can potentially replicate optimal catalyst structures across different scales, which paves the way for designing catalysts from the atomic level of electron interactions to large-scale industrial applications. The approach is based on extending the Onsager Theorem for nonlocal far-from-equilibrium processes.

Extending Onsager Theorem for Excitable Media

Building on the concept of thermodynamic potentials (e.g., thermal, hydraulic, mechanical, chemical, electrical), Onsager [17] explored the connection between the gradient of a generalised thermodynamic force, , and the resulting generalized flux . This framework reproduces established laws such as Fourier’s law (thermal), Darcy’s law (hydraulic), Stokes’ law (hydromechanical), Fick’s law (chemical), and Ohm’s law (electrical), each characterised by a specific diffusion coefficient. Experiments verify Onsager’s observation in systems at local equilibrium for nearly a century. Moreover, it captures the intriguing phenomenon of cross effects between the different THMCE processes. The generalised thermodynamic flux for multiphysics processes is defined as

The corresponding Onsager conductance matrix , also known as the matrix of kinetic coefficients for THMCE processes, is

Each matrix element represents a specific kinetic coefficient that describes the efficiency with which a particular force drives a specific flow. The product of thermodynamic force times the thermodynamic flux defines the entropy production of the non-equilibrium relaxed system, where the stability condition for local equilibrium, also widely known as the Onsager reciprocity relations [17], is

Although Onsager’s local equilibrium approach may allow some flexibility in modelling systems that behave at near-local equilibrium, with slight violation of the reciprocal principles, we do not think it is appropriate because of the motility and comparably fast kinetics of catalysts. Therefore, it is unlikely that catalytic systems operate in a near-local equilibrium; the enzyme example [8] suggests, for instance, significant spatial or temporal variations. Additionally, long-range interactions and fast cross-diffusion compared to self-diffusion processes can lead to nonlocal equilibrium conditions. Cross-reactions and cross-diffusion over the mesoscopic gradient zones are expected to cause significant spatial or temporal variations in properties like temperature, pressure, and concentration. A single set of equilibrium values cannot describe these variations. Non-equilibrium transport processes involve complex interactions that occur over space and time.

Observations from nonlocal hydrodynamic systems [18] show that these interactions cannot be separated and analysed independently. The key point is that non-equilibrium processes often have different characteristic lengths and timescales. This can lead to the formation of dynamic structures under the following conditions: (i) uneven distribution of constituents across space, leading to areas with more or less particles, and (ii) significant nonlocal transport processes. These factors, acting in irreversible processes, can permanently change the arrangement of internal constituents within the material, essentially freezing the dynamic structure into a new, stable internal structure. The suggested alternative existence of dynamic structures that operate under near nonlocal thermodynamic equilibrium is not new. It is used as an empirical concept to correct nonlocal effects in infrared atmospheric sounding interferometer data for weather forecasting [19]. Incorporating mesoscale and nonlocal dynamics expands the study of synergetic effects in materials [20], for which the separation of process scales was initially considered a crucial requirement for self-organisation to occur. A potential large-scale pattern formation process is attributed to THMC feedback mechanisms, which regulate the rate of network-forming fractures in solids caused by chemical reactions and the resulting volume changes [21]. Such diffusion-controlled fracture patterns may promote or impede the catalytic process on a larger scale, depending on whether the catalyst can be transported faster through the network or whether it is more efficient to achieve a pervasive reaction. This will again be controlled by the diffusion of the reaction product or by the reaction rate [22]. The RXD approach allows multiscale coupling of THMCE processes when cast into a tensor network, considering both options for the propagation of the fracture network. The tensor network connects two coupled RXD equations in a bilinear general vector space of individual T-H, T-M, T-C, and T-E couples to construct new binary and higher couples (e.g., next scale-up TH-TM couples, etc.). These binary couples are connected in a Riemann sheet structure as a hierarchical tensor tree [23]. The connection between the different multiscale levels is characterised by entangler operations that either increase or decrease (disentangle) the entanglement between the individual scales within a specific level of the hierarchy.

We propose that each binary couple develops towards an idealised nonlocal equilibrium state [24] based on Meixner’s [25] finding that, when dealing with chemical diffusion of paramagnetic gases under an applied magnetic field, Onsager’s reciprocity assumption breaks down. The cross-coupling of chemical diffusion to an applied magnetic field breaks the symmetry, causing the diffusion process to become nonlocal. This necessitates extending Onsager’s approach by considering a sign change in the Onsager coefficients when the magnetic field direction is reversed, as shown by Casimir [26]. This extension, known as the Onsager–Casimir reciprocal theorem, in which the antisymmetry of the Onsager coefficients describes the nonlocal equilibrium condition, reads as follows:

4. Discussion

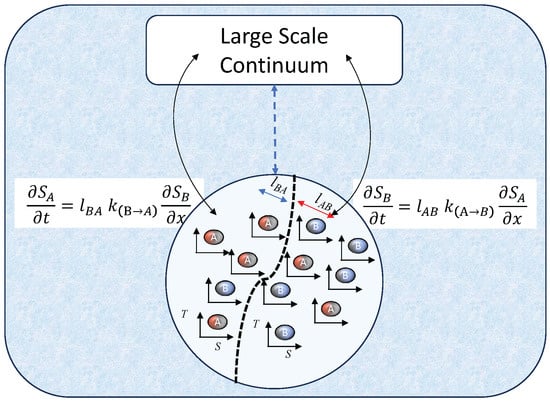

We examined the concept that enzymes or bacteria constitute active matter. Along with the substrate they interact with, they form an excitable bipartite continuum (i.e., consisting of at least two cross-coupled interacting species, as depicted in Figure 1), which under critical applied thermodynamic forces can enhance mass transport, as described by RXD equations [24]. Integrating this non-equilibrium growth presents exciting opportunities for creating functional, active materials and designing highly efficient catalysts. This new design strategy draws on nature’s example of multiscale and multiphysics interactions that can cause significant deviations from local equilibrium due to dynamics associated with nonlocal, nonlinear cross-couplings at a mesoscopic level. We have investigated this as a specific case study. These mesoscale interactions promote internal mass transfer between a reactant and a product due to catalysis. The catalysts are motile and can move on their substrate. They are attracted to specific regions of target molecule concentrations, thereby facilitating a catalytic reaction with the input of an external energy source (e.g., photons). Traditionally, it is assumed that the effect of species A’s concentration gradient on species B’s flux is equal and opposite to species B’s concentration gradient on species A’s flux. This reciprocal mass transfer allows these phases to be considered single entities and aggregated into a unified local equilibrium.

Figure 1.

Mesoscopic entropy production model of catalysis. This model depicts a reaction–diffusion (RXD) framework for a catalytic process with reactants A and products B. In the absence of a catalyst (dashed blue arrow), local equilibrium holds, and the entropy production of individual mesoscopic RXD processes amounts to a single large-scale continuum. The exothermic reaction (clockwise, S-T diagram) is preferred without a catalyst. The catalyst drives the endothermic reaction (anticlockwise), requiring work to increase product entropy. This work comes from the highly mobile catalyst (e.g., photosynthesis), which influences the distribution of the reactant/product. This high catalyst mobility can lead to complex patterns (stripes, spirals, or spots) due to the interplay between reaction rates, advection, and diffusion. Pattern formation is driven by maximum entropy production on the mesoscopic scale, minimizing the free-energy landscape (separating a pattern shown by the dashed, curvy black line). Due to the catalytic reaction, the model necessitates mapping both partial entropies () as black arrows. These partial entropies are calculated using cross-diffusion lengths (), reaction rates (), and their respective partial entropy gradients.

A unified equilibrium complies with Onsager’s original theorem, and nonlocal fluid and mass-exchange processes in the porous medium can be simplified to a local formulation. Onsager’s local equilibrium effectively explains pattern formation in chemical and biological systems when the diffusion rates of A and B differ. This difference is crucial for pattern formation. When the self-diffusion coefficients of A and B are similar, any local concentration fluctuations quickly even out, maintaining system uniformity. However, if the diffusion rates differ, small, random fluctuations in reactant concentration A can initiate localised production of B. The difference in self-diffusion creates a depletion zone for A around the initial increase of B. The specific reaction rates and diffusion coefficients determine whether this initial fluctuation is amplified (leading to a stable pattern) or dampened (returning to uniformity). A particular self-diffusion range rate is necessary for these patterns to form, known as an activator–inhibitor system, which creates a stable self-organising spatial Turing pattern. However, observations suggest other solutions [27]. The necessity of including cross-diffusion effects to capture the acceleration of catalytic processes by mesoscale interactions of enzymes is well documented [28]. Some enzymes are reported to be superdiffusive and increase motility by active pumping action [28]. This behaviour is represented in Figure 1 by the thermodynamic cycle of species A in the S-T diagram that performs the work by improving the entropy of species B, which requires work input. This active advection is captured through the cross-advection terms in Equation (6), where and are the concentration of the reactant A and product B, respectively [29].

Here, represent the self-advection velocity and with the cross-advection velocities of the enzyme. Double symmetric cross-advection can be reduced to the same characteristic equation as a system with cross-diffusion in only one equation, simplifying the solution [30]. However, when antisymmetric cross-diffusion and cross-advection terms are present, a double spiral pattern appears in the phase plot between the two species.

Stepping away from the abstract view of energy and entropy evolution, the novelty of the RXD approach for catalysts lies in mathematically addressing the reaction–diffusion–advection transport problem. While traditional methods focus on reaching minimal equilibrium energy states, the RXD approach can potentially manipulate these non-equilibrium processes to achieve a wider variety of structures by triggering an excitation phenomenon. In the excited state, catalysts could potentially improve the transport of reactants within the catalyst structure by moving around or stirring the reaction mixture to preferred sites. This could lead to more efficient collisions between the reactants and the catalyst’s active sites. Excited states might be designed to move reactants to specific locations within their structure, promoting desired reaction pathways and reducing unwanted side reactions. Another potential benefit of the excitation phenomenon is that the catalysts can repair or reconfigure themselves. This could be beneficial in designing catalysts that are more resistant to degradation or deactivation over time. Controlling non-equilibrium growth offers exciting possibilities for creating functional, active materials and designing highly efficient catalysts.

5. Conclusions

This paper has explored the theoretical aspects of bio-inspired catalysts, which may assist in replicating the design and control of active matter catalysts at both the molecular and larger scales. However, the practical implementation of specific biomimicking reactions remains a considerable challenge. Integrating active matter components with conventional catalyst materials requires a complete overhaul of catalyst design. The RXD approach offers a straightforward mathematical framework and enables examining dynamic pattern-forming processes through linear and nonlinear stability analysis, establishing a foundational rule for creating new catalysts. Additionally, the potential to layer the catalyst design and their support structures across multiple scales with various energy sources for catalytic reactions presents a novel option for catalyst design. These energy sources could include a combination of external thermodynamic forces such as temperature gradients, pressure differences, and chemical and electrical potential variations, each acting on catalytic support structures at their respective scales. These prospects offer exciting possibilities for the future of catalyst design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, K.R.-L.; methodology, K.R.-L. and ARC Group Researchers; validation, K.R.-L., V.C., M.H., H.T.C., B.Y., E.P.Z. and ARC Group Researchers; formal analysis, K.R.-L.; original draft preparation, K.R.-L.; review and editing, K.R.-L., V.C., M.H., H.T.C., B.Y. and E.P.Z.; visualisation, K.R.-L.; funding acquisition, K.R.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Australian Research Council partially funded this work via the Australian Centre of Excellence Scheme for the “CoE Carbon Science and Innovation” ARC Project ID: CE230100032.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This work exclusively used data from publicly available sources cited in the reference list.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support through their host institutions providing in-kind time commitment to the CoE.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RXD | Reaction–Cross-Diffusion Equation |

| MEP | Maximum Entropy Production |

| THMCE | Thermo-Hydro–Mechanical–Chemical–Electric |

References

- Coval, K. Basic Research Needs for Catalysis Science; Report; USDOE Office of Science: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Haghshenas, Y.; Yiran Jiao, P.K.; Catlow, R.; Yakobson, B.; Roy, A.; Jiao, Y.; Regenauer-Lieb, K.; Nguyen, D.; Xia, Z. Design Principles and AI-Guided Discovery of Earth-Abundant Catalysts for Clean Energy and Green Chemistry. Adv. Mater. 2024. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Giunta, G.; Seyed-Allaei, H.; Gerland, U. Cross-diffusion induced patterns for a single-step enzymatic reaction. Commun. Phys. 2020, 3, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, E.B.; Peters-Clarke, T.M.; Coon, J.J.; Martell, J.D. DNA-Scaffolded Synergistic Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 21402–21409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilter, O.; Vaucher, A.; Schwaller, P.; Laino, T. Designing catalysts with deep generative models and computational data. A case study for Suzuki cross coupling reactions. Digit. Discov. 2023, 2, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zemskov, E.P.; Vanag, V.K.; Epstein, I.R. Amplitude equations for reaction-diffusion systems with cross diffusion. Phys. Rev. E 2011, 84, 036216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemskov, E.P.; Kassner, K.; Hauser, M.J.B.; Horsthemke, W. Turing space in reaction-diffusion systems with density-dependent cross diffusion. Phys. Rev. E 2013, 87, 032906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jee, A.Y.; Cho, Y.K.; Granick, S.; Tlusty, T. Catalytic enzymes are active matter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E10812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gompper, G.; Winkler, R.G.; Speck, T.; Solon, A.; Nardini, C.; Peruani, F.; Löwen, H.; Golestanian, R.; Kaupp, U.B.; Alvarez, L.; et al. The 2020 motile active matter roadmap. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2020, 32, 193001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, C.H.; Pham, P.; Afif, S.A.; Goodman, M.F. Random-walk enzymes. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin Soft. Matter Phys. 2015, 92, 032717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, J.M.; Hastings, S.P. Spatial Patterns for Discrete Models of Diffusion in Excitable Media. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 1978, 34, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almirantis, Y.; Papageorgiou, S. Cross-diffusion effects on chemical and biological pattern formation. J. Theor. Biol. 1991, 151, 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanag, V.K.; Epstein, I.R. Cross-diffusion and pattern formation in reaction–diffusion systems. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009, 11, 897–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsyganov, M.A.; Biktashev, V.N.; Brindley, J.; Holden, A.V.; Ivanitsky, G.R. Waves in systems with cross-diffusion as a new class of nonlinear waves. Phys.-Uspekhi 2007, 50, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsyganov, M.A.; Biktashev, V.N. Classification of wave regimes in excitable systems with linear cross diffusion. Phys. Rev. E 2014, 90, 062912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Speybroeck, V. Challenges in modelling dynamic processes in realistic nanostructured materials at operating conditions. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2023, 381, 20220239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onsager, L. Reciprocal Relations in Irreversible Processes. Phys. Rev. 1931, 38, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khantuleva, T.; Shalymov, D. Nonlocal hydrodynamic modeling high-rate shear processes in condensed matter. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1560, 012057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricardi, M.; López-Puertas, M.; Funke, B. Modeling of Nonlocal Thermodynamic Equilibrium Effects in the Classical and Principal Component-Based Version of the RTTOV Fast Radiative Transfer Model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2018, 123, 5741–5761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, T.; Matsuda, T.; Takahashi, T.; Ichimiya, M.; Ashida, M.; Furukawa, Y.; Nakayama, M.; Ishihara, H. Synergetic Enhancement of Light-Matter Interaction by Nonlocality and Band Degeneracy in ZnO Thin Films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 157401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakobson, B.I. Morphology and rate of fracture in chemical decomposition of solids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1991, 67, 1590–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malthe-Sorenssen, A.; Jamtveit, B.; Meakin, P. Fracture patterns generated by diffusion controlled volume changing reactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 245501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regenauer-Lieb, K.; Hu, M. Understanding earthquake precursors: From subcritical instabilities to catastrophic events. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 055019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regenauer-Lieb, K.; Hu, M. Emergence of precursor instabilities in geo-processes: Insights from dense active matter. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meixner, J. Zur Thermodynamik der Thermodiffusion. Ann. Phys. 1941, 431, 333–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casimir, H. On Onsager’s Principle of Microscopic Reversibility. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1945, 17, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landge, A.N.; Jordan, B.M.; Diego, X.; Muller, P. Pattern formation mechanisms of self-organizing reaction-diffusion systems. Dev. Biol. 2020, 460, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Somasundar, A.; Sen, A. Enzymes as Active Matter. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2021, 12, 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemskov, E.P.; Tsyganov, M.A.; Ivanitsky, G.R.; Horsthemke, W. Solitary pulses and periodic wave trains in a bistable FitzHugh-Nagumo model with cross diffusion and cross advection. Phys. Rev. E 2022, 105, 014207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zemskov, E.P.; Kassner, K.; Tsyganov, M.A.; Hauser, M.J.B. Wavy fronts in reaction-diffusion systems with cross advection. Eur. Phys. J. B 2009, 72, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).