Abstract

KCTD (K-potassium Channel Tetramerization Domain-containing) proteins form an emerging class of proteins involved in a wide range of physiological and pathological processes. The involvement of these proteins in diverse biological functions is often a characteristic shared within family clades. Among them, the multifunctional roles of the cluster members 1B, which include KCTD1 and KCTD15, are particularly intriguing. Several studies have shown that these proteins participate in various signaling pathways and are linked to diseases such as cancer, genetic disorders, and obesity. In this proceedings paper, after a brief review of recent findings on the various (mis)functional roles of these proteins, we analyze available structural data and illustrate how such data have helped uncover structure-function relationships. A summary of the key open questions in the field is also included.

1. Introduction

Proteins are typically classified into families whose members share an evolutionary relationship, descending from a common ancestor. Proteins within a family generally present significant similarities at the sequence, structure, and functional levels [1]. Proteins may be further grouped into superfamilies when structural similarities are observed, but not sequence similarities. Conversely, a single family may be split into subfamilies by clustering members that have highly similar or identical functions.

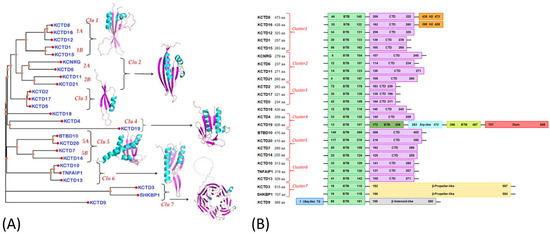

In the vast universe of proteins, KCTDs—proteins containing the (K)potassium Channel Tetramerization Domain—represent an emerging family whose members are involved in a multitude of physiological and pathological processes [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. The primary characteristic of this protein family is the presence, in all members, of closely related BTB/POZ (broad-complex, tramtrack, and Bric a brac/poxvirus and zinc finger) domains [14], hereafter denoted as BTB, which share significant sequence similarity with the T1 tetramerization domain of the subfamilies of potassium channels such as Kv1–Kv4 [15]. These versatile domains typically facilitate intermolecular interactions that can result in either homo- or hetero-oligomerization. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that BTB domains, through self-interaction, can exhibit a wide range of oligomeric states, ranging from monomers to polymers [16]. In addition to the BTB, which is generally near the N-terminus, KCTDs have a C-terminal domain that shows significant sequence similarities only within members of the same clade. Meanwhile, they are unrelated among members of different clades. This commonly accepted picture of the KCTD organization has been recently revisited by comparing the structure of the C-terminal domains [17] generated using AlphaFold (version 2), a powerful machine learning-based approach for protein structure prediction using only sequence information [18,19,20]. Notably, this study has shown that, despite the lack of any significant sequence similarity, the C-terminal domains of KCTDs belonging to different clades share a similar structural organization characterized by a single β-sheet that is surrounded by one or two helices (Figure 1). The quantification of these similarities, performed using the DALI server [21], led to the definition of a structure-based pseudo-phylogenetic tree that uncovered previously undetected similarities among the protein family [17], thereby providing a new tool for the structural interpretation of the functional analogies and diversities within the family. Applying structural prediction methods to this protein family also addressed the previous lack of structural data for these proteins. In fact, using AlphaFold (version 2), it was possible to determine the three-dimensional structures of all family members [22]. The application of AlphaFold (version 2) proved to be effective in distinguishing family members capable of interacting with Cullin 3 and providing the structural basis for these interactions [23]. It is foreseeable that all this information will soon be exploited for defining structure–function relationships in this family.

Figure 1.

(A) DALI dendrogram generated from the structures of the KCTD C-terminal domains. Shown are representative three-dimensional models of the folded domains in the C-terminal region. (B) Schematic diagram of the KCTD protein domain organization. Cluster numbers are indicated in red. The standard BTB domains are in green. The domains of the C-terminal regions that follow the BTB are displayed in different colors. The figures are taken from ref. [17].

One of the most intriguing properties of KCTDs is their involvement in multiple, often unrelated, physiological and pathological contexts [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. The dysregulation of these proteins is a key factor in severe human pathologies that include many cancers, neurodevelopmental disorders, obesity, and genetic diseases. In principle, the diversified roles of these proteins may be attributed to the differences observed in their C-terminal regions. However, it is often observed that members of the same clade or even a single KCTD can play a crucial role in unrelated biological processes. A typical example of this is the highly similar proteins KCTD1/KCTD15, which constitute cluster 1b (Figure 1). As described below, their dysregulations have been linked to several pathological states. In the present proceedings paper, we will outline the results achieved by our laboratory and other groups in defining structure–function relationships in this cluster.

2. Methods

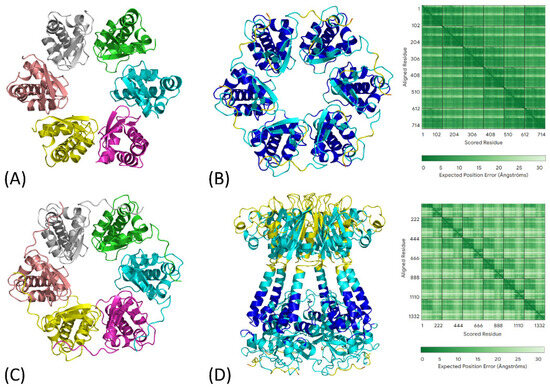

Most of the information used in this proceedings paper was retrieved from the literature and mining the Protein Data Bank (PDB) structural database. However, we integrated this information by performing a new prediction of the hexameric structure of the G88D mutant of KCTD15, which has been recently shown to be potentially implicated in a distinctive frontonasal dysplasia syndrome [24]. Structural models of KCTD15 (UniProtKB code: Q96SI1) hexameric assemblies, encompassing either the region containing the pre-BTB and BTB domains (residues 44–162) or the full-length protein lacking the disordered N- and C-terminal regions (residues 44–265), were generated using the AlphaFold3 (AF3) algorithm (https://alphafoldserver.com/, accessed on 16 October 2025) with default parameters [25]. The G88D mutant was modeled, as the available crystallographic structure of the hexameric form (PDB ID: 8PNM) corresponds to this variant [24]. Among the five models produced by AF3, the top-ranked model (model 0) was considered. The reliability of these predicted structures was evaluated by inspecting the Predicted Aligned Error (PAE) matrices and the per-residue Local Distance Difference Test (pLDDT) scores. Figures of the structural models were generated using PyMOL (version 2.0; Schrödinger, LLC).

3. Roles of KCTD1/KCTD15 in Physio-Pathological Contexts

The involvement of these proteins in diversified biological contexts has been documented in several literature studies. They belong to the KCTD subgroups that are unable to bind Cullin 3 and therefore are not part of CRL ligases of the ubiquitination process [26,27]. However, they are involved in many physiological processes. KCTD1 and KCTD15 have been identified as repressors of the transcription factor AP-2α, which is inhibited by the selective binding of BTB domains of these proteins [28,29,30]. These findings suggest a role for these proteins in the Wnt signaling pathway. It has also been shown that KCTD15 plays a key role in cardiac outflow tract development, while KCTD1 regulates distal nephron function. Moreover, the combined inactivation of KCTD1 and KCTD15 in keratinocytes results in abnormal skin appendages [31]. These two proteins have been found to perform key and partially overlapping roles in neural crest cell formation [29,31,32]. Moreover, KCTD1 plays an active role in adipogenesis [30], while genome-wide association studies have linked KCTD15 to a higher risk of obesity [33]. Additionally, KCTD15 has been found to physically interact with GRP78, a key factor in adipogenesis [34]. Finally, KCTD1 is connected to GPCR signaling through stabilizing the protein levels of the cAMP-synthesizing enzyme Adenylyl Cyclase type 5 (AC5) [35]. However, the interaction between KCTD1 and G proteins remains to be clarified [36]. KCTD1/15 are also involved in pathological states such as cancer and genetic diseases, which are briefly reviewed in the paragraphs below.

The involvement of these proteins in cancer has been reviewed by Angrisani et al. [37]. They extensively described the role of up- and downregulation in the insurgence and progression of this disease. In this framework, they report the dysregulation of KCTD1 in ovarian, endometrial, pancreatic, and lung cancers. Recent studies have indicated that this protein is involved in colorectal cancer [38], T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia [39], medulloblastoma [40], and hepatocellular cancer [41]. Several studies have also shown the involvement of KCTD15 in leukemias [42,43,44]. Furthermore, this protein plays a role in medulloblastoma [45], ovarian cancer [46], adenocarcinoma [47], and colorectal cancer [48].

Heterozygous missense mutations in KCTD1 have been identified as the cause of Scalp-Ear-Nipple (SEN) syndrome, a rare autosomal-dominant disorder [49]. The clinical features of this disease include scalp aplasia cutis congenita and other ectodermal abnormalities. More recently, naturally occurring mutants of KCTD15 have been shown to cause a distinctive frontonasal dysplasia syndrome with clinical features resembling those seen in SEN syndrome [24]. Furthermore, additional studies have demonstrated that KCTD1/KCTD15 complexes are essential regulators of ectodermal and neural crest cell functions, and that aplasia cutis congenita is a neurocristopathy [31,50].

4. Structure–Function Relationships in KCTD1/KCTD15 Proteins

4.1. The BTB Domain of KCTD1/KCTD15

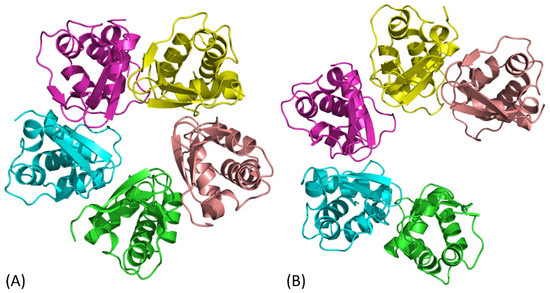

Initial structural characterizations were performed on the BTB domain of KCTD1 [27]. The crystallographic structures of this domain showed two possible arrangements: a close and an open pentamer (Figure 2). The pentameric organization of the BTB was a clear indication of the preferred pentameric state of this protein, in line with what was observed for KCTD5 [51] and other family members [52]. The occurrence of an open pentamer was likely caused by protein truncation and the crystallization condition, as molecular dynamics simulations on this structure suggest its tendency to shift toward a closed state [53]. Although these structures reported only a portion of KCTD1, they constitute the template to define the structural basis of the mutations causing the SEN syndrome found in this domain. Extensive in vitro biophysical characterizations were conducted on the mutants KCTD1_H33P, KCTD1_G62D, KCTD1_D69E, and KCTD1_H74P, and KCTD1_P20S [54]. This study demonstrated that in all cases, the mutation induced a significant destabilization of the protein, which was accompanied by a high propensity to form amyloid-like aggregates. This observation could explain the dominant effects of these mutations, as the aggregates formed by the mutated protein might serve as a template for the precipitation of the wild-type form that was present in heterozygous individuals [54]. The destabilization and precipitation completely eliminated the mutants’ ability to bind the transcription factor AP-2α, a functional partner of KCTD1 and KCTD15 [28,29,55,56,57]. The inspection of the PDB structures of the domain provided a straightforward explanation for the observed destabilization of the protein in all but one case. Indeed, for most of them (KCTD1_H33P, KCTD1_G62D, KCTD1_D69E, and KCTD1_H74P), the mutation site is close to the intermolecular interface of the pentamer. Conversely, the protein destabilization and the disease caused by the P20S mutation remain puzzling, as the mutated residue is located in the region that precedes the BTB domain (pre-BTB), which was not present in the crystallographic structure and is assumed to be unfolded. This mystery was resolved by determining the structure of the full-length wild-type protein [58] and the mutant KCTD1_P20S [59].

Figure 2.

Crystal structures of the pentameric KCTD1 BTB domain are shown in cartoon representation: (A) closed conformation (PDB ID: 5BXB) and (B) open conformation (PDB ID: 5BXD). Each chain is differently colored for clarity.

Very recently, it has been reported that KCTD15 is a new human disease gene whose mutations have been associated with a distinct frontonasal dysplasia as well as cutis aplasia or sparse hair reminiscent of the phenotypes observed in SEN [24]. Also in this case, the two mutations (D104H and G88D) were found in the BTB domain. The biophysical characterization of these mutants revealed that KCTD15_D104H was monomeric and partially unfolded, whereas KCTD15_G88D formed unexpected symmetrical hexamers (Figure 3A). The authors convincingly concluded that these mutants caused the disease by destabilizing the functional pentamer, leading to the formation of monomeric and higher oligomeric species. Interestingly, AlphaFold (version 3) correctly predicts the hexameric assembly of the BTB domain of the G88D mutant of KCTD15 (Figure 3B,C) and suggests that it is compatible with the full-length structure of the protein (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

(A) Crystal structure of the hexameric BTB domain of the KCTD15 G88D mutant (PDB ID: 8PNM) colored by chain. (B) AF3-predicted model of the KCTD15 G88D mutant encompassing the region containing the pre-BTB and BTB domains (residues 44–162), along with the corresponding PAE matrix. This model is shown colored by chain in (C). (D) AF3-predicted model of the KCTD15 G88D mutant full-length protein lacking the disordered N- and C-terminal regions (residues 44–265) with its corresponding PAE matrix. The models in panels (B,D) are colored according to the AlphaFold 3 per-residue confidence metric (pLDDT) as follows: blue for pLDDT > 90, cyan for 70 < pLDDT ≤ 90, yellow for 50 < pLDDT ≤ 70, and orange for pLDDT < 50.

4.2. The Structure of the Full-Length KCTD1 and of the Mutant KCTD1_P20S

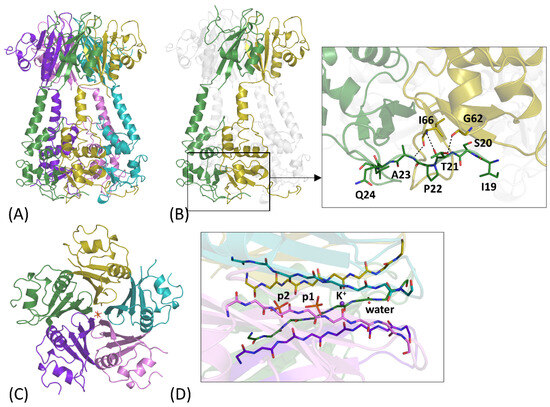

In the last few years, three different crystal structures of KCTD1 comprising both the BTB and the C-terminal domain have been reported [58,59]. The first structure reported in the PDB (PDB ID: 6S4L) was a truncated form of the full-length protein in which the pre-BTB region was missing [58]. Subsequently, the full-length structures of the wild-type (PDB ID: 9FOI) [58] and the P20S mutant (PDB ID: 9FQ1) [59] of KCTD1 have been determined. These models have demonstrated that the global structure of the protein is stabilized by an extended domain swapping in which the BTB domain of one chain interacts with the C-terminal domain and the pre-BTB region of an adjacent chain (Figure 4A,B). Interestingly, these interdomain contacts depend on rather unusual interactions. In fact, the BTB-preBTB interaction is based on a polyproline (PPII)-PPII recognition motif (Figure 4B), while the BTB-CTD contacts are mediated by an unusual (+/−) helix discontinuous association [59]. The structural characterization of the full-length KCTD1 also explained the puzzling effect of the SEN syndrome-causing mutation P20S. In fact, the observation that the pre-BTB region is not unfolded but adopts a polyproline II structure that binds to the BTB domain (Figure 4B) and stabilizes the pentamer suggests that replacing proline 20 weakens this region’s tendency to form a PPII structure. This finding has been supported by molecular dynamics studies [59].

Figure 4.

(A) Crystal structure of the pentameric assembly of the KCTD1 P20S mutant (PDB ID: 9FQ1) colored by chain. (B) Interdomain preBTB-BTB interface that stabilizes the domain-swapped pentamer in the crystal structure. Residues of the preBTB region and those involved in hydrogen bonding interactions at the interdomain interface are shown as sticks. (C) Top view of the CTD domain of KCTD1 P20S mutant, colored by chain. (D) Ligands in the central channel, including a potassium ion (K+), a water molecule, and two phosphate groups (denoted p1 and p2), are shown.

5. Conclusions

Investigations conducted over the past decade have provided important clues about the structural basis of the (mal)functioning of KCTD1 and KCTD15. Notably, the interpretation of how disease-causing mutations affect these proteins is particularly significant. The dominant effects of diseases caused by these mutations have been tentatively linked to the tendency of these proteins to form amyloid-like aggregates, which, in heterozygous individuals, may sequester the wild-type form of the protein [54]. Structural studies have highlighted the importance of intermolecular interactions that stabilize the KCTD1 domain-swapping structure in maintaining the protein’s integrity. These studies have also shown the role that mixed KCTD1/KCTD15 structural states play in some functional contexts [31].

There are, however, several other aspects of the functioning of KCTD1/KCTD15 that require further investigation. In particular, the structural basis of the partnerships of these proteins, including those involved with the transcription factors of the class AP, is largely unknown.

Author Contributions

L.V.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Validation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing; N.B.: Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by PNRR MUR—CN00000013 “National Centre for HPC, Big Data and Quantum Computing—Spoke 8” and by the Italian Ministry of Health (grant “Ricerca Corrente”).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The coordinates of the AF3-predicted models here described are available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Maurizio Amendola, Luca De Luca, Massimiliano Mazzocchi, and Giorgio Varriale for their technical support. We acknowledge the CINECA award under the ISCRA initiative (ISCRA B project KCTD-CTD ID HP10BBY7W1 and ISCRA C project AF-Koli ID HP10C52U80), for the availability of high-performance computing resources and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Orengo, C.; Bateman, A. (Eds.) Protein Families: Relating Protein Sequence, Structure, and Function, 1st ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-470-62422-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kloeber, J.A.; Chen, B.; Sun, G.; King, C.S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Wu, Z.; Zhu, S.; Zhao, F.; Qin, H.; et al. KCTD10 Is a Sensor for Co-Directional Transcription–Replication Conflicts. Nature 2025, 648, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, C.; Liu, P.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, K.; Li, X.; Li, G.; Cheng, J.; Bu, M.; Chen, H.; et al. KCTD10 p.C124W Variant Contributes to Schizophrenia by Attenuating LLPS-Mediated Synapse Formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2400464121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lospinoso Severini, L.; Loricchio, E.; Navacci, S.; Basili, I.; Alfonsi, R.; Bernardi, F.; Moretti, M.; Conenna, M.; Cucinotta, A.; Coni, S.; et al. SALL4 Is a CRL3REN/KCTD11 Substrate That Drives Sonic Hedgehog-Dependent Medulloblastoma. Cell Death Differ. 2024, 31, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Yu, H.; Chen, Y.; Ren, J.; Lu, Y.; Sun, Y. The CRL3KCTD10 Ubiquitin Ligase–USP18 Axis Coordinately Regulates Cystine Uptake and Ferroptosis by Modulating SLC7A11. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2320655121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Wang, Z.; Tang, M.; Zhang, W.; Li, G.; Tan, S.; Mu, C.; Hu, M.; Zhang, D.; Jia, X.; et al. KCTD10 Regulates Brain Development by Destabilizing Brain Disorder–Associated Protein KCTD13. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2315707121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, J.; Ke, P.; Guo, H.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Tian, X.; Huang, Z.; Xu, X.; Xu, D.; Ma, Y.; et al. KCTD13-Mediated Ubiquitination and Degradation of GluN1 Regulates Excitatory Synaptic Transmission and Seizure Susceptibility. Cell Death Differ. 2023, 30, 1726–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; Abreu, N.; Levitz, J.; Kruse, A.C. Structural Basis for KCTD-Mediated Rapid Desensitization of GABAB Signalling. Nature 2019, 567, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla, C.O.; Filonova, I.; Walker, A.K.; Xuan, Z.X.; Holehonnur, R.; Espinosa, F.; Liu, S.; Thyme, S.B.; López-García, I.A.; Mendoza, D.B.; et al. Kctd13 Deletion Reduces Synaptic Transmission via Increased RhoA. Nature 2017, 551, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockmann, M.; Blomen, V.A.; Nieuwenhuis, J.; Stickel, E.; Raaben, M.; Bleijerveld, O.B.; Altelaar, A.F.M.; Jae, L.T.; Brummelkamp, T.R. Genetic Wiring Maps of Single-Cell Protein States Reveal an off-Switch for GPCR Signalling. Nature 2017, 546, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golzio, C.; Willer, J.; Talkowski, M.E.; Oh, E.C.; Taniguchi, Y.; Jacquemont, S.; Reymond, A.; Sun, M.; Sawa, A.; Gusella, J.F.; et al. KCTD13 Is a Major Driver of Mirrored Neuroanatomical Phenotypes of the 16p11.2 Copy Number Variant. Nature 2012, 485, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenk, J.; Metz, M.; Zolles, G.; Turecek, R.; Fritzius, T.; Bildl, W.; Tarusawa, E.; Kulik, A.; Unger, A.; Ivankova, K.; et al. Native GABAB Receptors Are Heteromultimers with a Family of Auxiliary Subunits. Nature 2010, 465, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canettieri, G.; Di Marcotullio, L.; Greco, A.; Coni, S.; Antonucci, L.; Infante, P.; Pietrosanti, L.; De Smaele, E.; Ferretti, E.; Miele, E.; et al. Histone Deacetylase and Cullin3–RENKCTD11 Ubiquitin Ligase Interplay Regulates Hedgehog Signalling through Gli Acetylation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stogios, P.J.; Downs, G.S.; Jauhal, J.J.; Nandra, S.K.; Privé, G.G. Sequence and Structural Analysis of BTB Domain Proteins. Genome Biol. 2005, 6, R82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, C. An Overview of the Potassium Channel Family. Genome Biol. 2000, 1, reviews0004.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, P.M.C.; Park, J.; Brown, J.; Hunkeler, M.; Roy Burman, S.S.; Donovan, K.A.; Yoon, H.; Nowak, R.P.; Słabicki, M.; Ebert, B.L.; et al. Polymerization of ZBTB Transcription Factors Regulates Chromatin Occupancy. Mol. Cell 2024, 84, 2511–2524.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, L.; Balasco, N.; Smaldone, G.; Berisio, R.; Ruggiero, A.; Vitagliano, L. AlphaFold-Predicted Structures of KCTD Proteins Unravel Previously Undetected Relationships among the Members of the Family. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirdita, M.; Schütze, K.; Moriwaki, Y.; Heo, L.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Steinegger, M. ColabFold: Making Protein Folding Accessible to All. Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senior, A.W.; Evans, R.; Jumper, J.; Kirkpatrick, J.; Sifre, L.; Green, T.; Qin, C.; Žídek, A.; Nelson, A.W.R.; Bridgland, A.; et al. Improved Protein Structure Prediction Using Potentials from Deep Learning. Nature 2020, 577, 706–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, L. Dali Server: Structural Unification of Protein Families. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W210–W215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, L.; Balasco, N.; Vitagliano, L. Alphafold Predictions Provide Insights into the Structural Features of the Functional Oligomers of All Members of the KCTD Family. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasco, N.; Esposito, L.; Smaldone, G.; Salvatore, M.; Vitagliano, L. A Comprehensive Analysis of the Structural Recognition between KCTD Proteins and Cullin 3. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, K.A.; Cruz Walma, D.A.; Pinkas, D.M.; Tooze, R.S.; Bufton, J.C.; Richardson, W.; Manning, C.E.; Hunt, A.E.; Cros, J.; Hartill, V.; et al. BTB Domain Mutations Perturbing KCTD15 Oligomerisation Cause a Distinctive Frontonasal Dysplasia Syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 2024, 61, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate Structure Prediction of Biomolecular Interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaldone, G.; Pirone, L.; Balasco, N.; Di Gaetano, S.; Pedone, E.M.; Vitagliano, L. Cullin 3 Recognition Is Not a Universal Property among KCTD Proteins. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, A.X.; Chu, A.; Nielsen, T.K.; Benlekbir, S.; Rubinstein, J.L.; Privé, G.G. Structural Insights into KCTD Protein Assembly and Cullin3 Recognition. J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 428, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Luo, C.; Zhou, J.; Zhong, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhou, F.; Ren, K.; Gan, L.; He, A.; Zhu, J.; et al. The Interaction of KCTD1 with Transcription Factor AP-2α Inhibits Its Transactivation. J. Cell. Biochem. 2009, 106, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarelli, V.E.; Dawid, I.B. Inhibition of Neural Crest Formation by Kctd15 Involves Regulation of Transcription Factor AP-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 2870–2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirone, L.; Smaldone, G.; Spinelli, R.; Barberisi, M.; Beguinot, F.; Vitagliano, L.; Miele, C.; Di Gaetano, S.; Raciti, G.A.; Pedone, E. KCTD1: A Novel Modulator of Adipogenesis through the Interaction with the Transcription Factor AP2α. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA—Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2019, 1864, 158514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymundo, J.R.; Zhang, H.; Smaldone, G.; Zhu, W.; Daly, K.E.; Glennon, B.J.; Pecoraro, G.; Salvatore, M.; Devine, W.A.; Lo, C.W.; et al. KCTD1/KCTD15 Complexes Control Ectodermal and Neural Crest Cell Functions, and Their Impairment Causes Aplasia Cutis. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e174138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, X.; Aouacheria, A.; Lionnard, L.; Metz, K.A.; Soane, L.; Kamiya, A.; Hardwick, J.M. KCTD: A New Gene Family Involved in Neurodevelopmental and Neuropsychiatric Disorders. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2019, 25, 887–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamero-Villarroel, C.; González, L.M.; Rodríguez-López, R.; Albuquerque, D.; Carrillo, J.A.; García-Herráiz, A.; Flores, I.; Gervasini, G. Influence of TFAP2B and KCTD15 Genetic Variability on Personality Dimensions in Anorexia and Bulimia Nervosa. Brain Behav. 2017, 7, e00784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smaldone, G.; Pirone, L.; Capolupo, A.; Vitagliano, L.; Monti, M.C.; Di Gaetano, S.; Pedone, E. The Essential Player in Adipogenesis GRP78 Is a Novel KCTD15 Interactor. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 115, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Muntean, B.S. KCTD1 Regulation of Adenylyl Cyclase Type 5 Adjusts Striatal cAMP Signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2406686121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Muntean, B.S. Pathogenic Variants in KCTD1 Disrupt cAMP Signaling and Cellular Communication Associated with Developmental Pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 110813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrisani, A.; Di Fiore, A.; De Smaele, E.; Moretti, M. The Emerging Role of the KCTD Proteins in Cancer. Cell Commun. Signal. 2021, 19, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaldone, G.; Pecoraro, G.; Pane, K.; Franzese, M.; Ruggiero, A.; Vitagliano, L.; Salvatore, M. The Oncosuppressive Properties of KCTD1: Its Role in Cell Growth and Mobility. Biology 2023, 12, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buono, L.; Iside, C.; Pecoraro, G.; De Matteo, A.; Beneduce, G.; Penta De Vera d’Aragona, R.; Parasole, R.; Mirabelli, P.; Vitagliano, L.; Salvatore, M.; et al. A Comprehensive Analysis of the Expression Profiles of KCTD Proteins in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Evidence of Selective Expression of KCTD1 in T-ALL. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fiore, A.; Bellardinelli, S.; Pirone, L.; Russo, R.; Angrisani, A.; Terriaca, G.; Bowen, M.; Bordin, F.; Besharat, Z.M.; Canettieri, G.; et al. KCTD1 Is a New Modulator of the KCASH Family of Hedgehog Suppressors. Neoplasia 2023, 43, 100926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, Z.; Chen, L.; Li, L.; Ouyang, M.; Zhou, H.; Xiao, K.; Lin, L.; Chu, P.K.; Zhou, C.; et al. Exosomes Delivering miR-129-5p Combined with Sorafenib Ameliorate Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression via the KCTD1/HIF-1α/VEGF Pathway. Cell Oncol. 2025, 48, 743–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, L.; Baselice, S.; Messina, F.; Giannatiempo, R.; Farina, A.; Vitagliano, L.; Smaldone, G.; Salvatore, M. KCTD15 Is Overexpressed in her2+ Positive Breast Cancer Patients and Its Silencing Attenuates Proliferation in SKBR3 CELL LINE. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smaldone, G.; Coppola, L.; Pane, K.; Franzese, M.; Beneduce, G.; Parasole, R.; Menna, G.; Vitagliano, L.; Salvatore, M.; Mirabelli, P. KCTD15 Deregulation Is Associated with Alterations of the NF-κB Signaling in Both Pathological and Physiological Model Systems. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smaldone, G.; Beneduce, G.; Incoronato, M.; Pane, K.; Franzese, M.; Coppola, L.; Cordella, A.; Parasole, R.; Ripaldi, M.; Nassa, G.; et al. KCTD15 Is Overexpressed in Human Childhood B-Cell Acute Lymphoid Leukemia. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiombi, E.; Angrisani, A.; Fonte, S.; De Feudis, G.; Fabretti, F.; Cucchi, D.; Izzo, M.; Infante, P.; Miele, E.; Po, A.; et al. KCTD15 Inhibits the Hedgehog Pathway in Medulloblastoma Cells by Increasing Protein Levels of the Oncosuppressor KCASH2. Oncogenesis 2019, 8, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cheng, C.; Tang, B. Mechanistic Insights Into the Tumor-Driving and Diagnostic Roles of KCTD Family Genes in Ovarian Cancer: An Integrated In Silico and In Vitro Analysis. Cancer Med. 2025, 14, e71147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.-X.; Zhang, W.-D.; Dai, P.-H.; Deng, J.; Tan, L.-H. Comprehensive Analysis of KCTD Family Genes Associated with Hypoxic Microenvironment and Immune Infiltration in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.-Y.; Wu, L.; Zhang, T.-N.; Chen, H.-H. KCTD15 Acts as an Anti-Tumor Factor in Colorectal Cancer Cells Downstream of the Demethylase FTO and the m6A Reader YTHDF2. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marneros, A.G.; Beck, A.E.; Turner, E.H.; McMillin, M.J.; Edwards, M.J.; Field, M.; de Macena Sobreira, N.L.; Perez, A.B.A.; Fortes, J.A.R.; Lampe, A.K.; et al. Mutations in KCTD1 Cause Scalp-Ear-Nipple Syndrome. Am. J. Human. Genet. 2013, 92, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marneros, A.G. Aplasia Cutis Congenita Pathomechanisms Reveal Key Regulators of Skin and Skin Appendage Morphogenesis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2024, 144, 2399–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dementieva, I.S.; Tereshko, V.; McCrossan, Z.A.; Solomaha, E.; Araki, D.; Xu, C.; Grigorieff, N.; Goldstein, S.A.N. Pentameric Assembly of Potassium Channel Tetramerization Domain-Containing Protein 5. J. Mol. Biol. 2009, 387, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaldone, G.; Pirone, L.; Pedone, E.; Marlovits, T.; Vitagliano, L.; Ciccarelli, L. The BTB Domains of the Potassium Channel Tetramerization Domain Proteins Prevalently Assume Pentameric States. FEBS Lett. 2016, 590, 1663–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasco, N.; Smaldone, G.; Vitagliano, L. The Structural Versatility of the BTB Domains of KCTD Proteins and Their Recognition of the GABAB Receptor. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smaldone, G.; Balasco, N.; Pirone, L.; Caruso, D.; Di Gaetano, S.; Pedone, E.M.; Vitagliano, L. Molecular Basis of the Scalp-Ear-Nipple Syndrome Unraveled by the Characterization of Disease-Causing KCTD1 Mutants. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Chen, L.; Yang, L.; Ye, Z.; Huang, W.; Li, X.; Liu, Q.; Qiu, J.; Ding, X. KCTD1 Mutants in Scalp-ear-nipple Syndrome and AP-2α P59A in Char Syndrome Reciprocally Abrogate Their Interactions, but Can Regulate Wnt/β-catenin Signaling. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 22, 3895–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senapati, B.; Raymundo, J.R.; Makkar, J.; Driskell, R.R.; Marneros, A.G. KCTD1/KCTD15-Mediated Repression of AP-2α/AP-2β Is Required for Proper Skin Appendage Development and Epidermal Homeostasis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marneros, A.G. AP-2β/KCTD1 Control Distal Nephron Differentiation and Protect against Renal Fibrosis. Dev. Cell 2020, 54, 348–366.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkas, D.M.; Bufton, J.C.; Hunt, A.E.; Manning, C.E.; Richardson, W.; Bullock, A.N. A BTB Extension and Ion-Binding Domain Contribute to the Pentameric Structure and TFAP2A Binding of KCTD1. Structure 2024, 32, 1586–1593.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasco, N.; Ruggiero, A.; Smaldone, G.; Pecoraro, G.; Coppola, L.; Pirone, L.; Pedone, E.M.; Esposito, L.; Berisio, R.; Vitagliano, L. Structural Studies of KCTD1 and Its Disease-Causing Mutant P20S Provide Insights into the Protein Function and Misfunction. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).