Abstract

The Rasch model has the desirable property that item parameter estimation can be separated from person parameter estimation. This implies that no assumptions about the ability distribution are required when estimating item difficulties. Pairwise estimation approaches in the Rasch model exploit this principle by estimating item difficulties solely from sample proportions of respondents who answer item i correctly and item j incorrectly. A recent contribution by Tutz introduced Tutz’s pairwise separation estimator (TPSE) for the more general class of homogeneous monotone (HM) models, extending the idea of pairwise estimation to this broader setting. The present article examines the asymptotic behavior of the TPSE within the Rasch model as a special case of the HM framework. It should be emphasized that both analytical derivations and a numerical illustration show that the TPSE yields asymptotically biased item parameter estimates, rendering the estimator inconsistent, even for a large number of items. Consequently, the TPSE cannot be recommended for empirical applications.

1. Introduction

In the social sciences, cognitive tests or questionnaires are often administered that yield binary (i.e., dichotomous) random variables for . These variables are frequently analyzed using item response theory (IRT; [1,2,3,4,5]) models, which reduce the dimensionality of the item responses to a unidimensional or multidimensional latent variable . Unidimensional IRT models [6] are particularly appealing because they summarize the I item responses into a single latent variable .

The earliest development in IRT was the Rasch model [7,8,9,10,11], which models the dichotomous item response of person n on item i as

where denotes the ability of person n and the difficulty of item i. Note that the item response function (IRF) in the Rasch model employs the logistic link function .

The IRF in (1), which relies on the logistic link function , can be replaced by any smooth monotone link function F, yielding item response probabilities of the form

The IRT model in (2) is also referred to as a homogeneous monotone (HM; [5,12,13]) model.

The Rasch model defined in (1) has the advantage, compared with the IRT model in (2), that the sum score is a sufficient statistic for when the Rasch model is estimated by maximum likelihood [14]. In addition, estimators of item difficulties can be constructed without simultaneously estimating the ability parameter . Unfortunately, this property is often conflated with concepts of parameter separability or specific objectivity in the Rasch model [15,16]. Conditional maximum likelihood estimation [9,14] and pairwise estimation approaches [17,18,19,20,21] both build on this idea.

To illustrate the conditioning principle, consider the ratio

It is evident from (3) that the ability parameter cancels out, implying that item parameters can be estimated independently of person parameters in an estimation framework based on such ratios. Furthermore, it follows (see, e.g., [22]) that

The identities in (3) and (4) allow for the estimation of item difficulties from probabilities for item pairs in samples of persons. The row averaging estimation approach of Choppin [17] relies on the pairwise estimation principle and uses log-transformed ratios of sample proportions (see (4)) as

Hence, estimates of the probabilities can be used to estimate item difficulties.

In a recent paper, Tutz [23] (see also [5,24]) proposed Tutz’s pairwise separation estimator (TPSE) for estimating item difficulties in the more general HM model defined in (2). The TPSE is motivated by the idea that person and item parameter estimation can be separated. Following this reasoning, the estimator uses sample proportion estimates of and constructs item difficulty estimates based on pairwise differences. However, Tutz [5,23] did not provide conditions under which the TPSE yields consistent item parameter estimates, that is, the asymptotic behavior was not examined. The original reference [23] included a simulation study, but it relied on small samples and limited variation in item and person parameter distributions, as well as a small number of items. In particular, the simulation study did not offer evidence regarding the consistency of the TPSE.

The present article investigates the statistical properties of the TPSE in greater depth. The focus lies on the asymptotic case, that is, on determining the bias of the TPSE in infinite sample sizes. Attention is restricted to the Rasch model, because this model permits more tractable derivations of the bias, and the expressions involved in the TPSE simplify under this well-studied HM model compared to the general HM specification with an arbitrary smooth monotone link function F. It is shown in the present article that the TPSE generally produces biased item parameter estimates and therefore cannot be recommended as a reliable estimator in the Rasch model. As a consequence, item parameter estimates in the HM model are also biased. Although the formulation of the TPSE based on the parameter separability principle in [23] may have some aesthetic appeal, it is not useful as a reliable estimation technique.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the TPSE as introduced in Tutz [23]. Section 3 examines the bias of the TPSE item difficulty estimates in the Rasch model using analytical derivations. A Numerical Illustration is presented in Section 4 to confirm the analytical findings. An empirical example is additionally provided in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 provides a concluding discussion.

2. Tutz’s Pairwise Separation Estimator

In this section, the TPSE as proposed in [23] is presented. Assume that the HM IRT model with link function F holds. If the item response probabilities were available, one could compute the difference

By conditioning on the same person n in (6), the ability parameter is removed. Hence, the estimation of is separated from the estimation of .

However, only binary observations are available instead of the probabilities . Consequently, the difference in (6) cannot be applied directly to the binary data because the ability values are unknown. To address this issue, ref. [23] introduced pseudo-observations defined as

An incorrect item response is replaced by in the pseudo-observation , while a correct response becomes . The unknown probabilities in (6) are thus replaced by the pseudo-observations , leading to

where and . According to Tutz [23], the right-hand side of (8) serves as an empirical approximation of . The parameter difference in (8) now has an explicit notation that indicates its dependence on person n.

By defining , it follows from (8)

Thus, according to Tutz [23], the difference is intended to estimate by aggregating contributions across persons n:

where is the proportion of persons who responded correctly to item i and incorrectly to item j and thus estimates population probabilities . By the law of large numbers, it follows that are consistent estimators of . For symmetric link functions F, it holds that .

The TPSE estimate of is finally defined in [23] as

This construction yields , meaning that the first item serves as the reference item with fixed difficulty 0.

It should be emphasized that the pseudo-observations are introduced by Tutz [23] solely to derive the TPSE. The pseudo-observations are not explicitly used in the estimation procedure; instead, only a relationship between and the sample proportions is derived.

The dependence of the item parameter estimates obtained from the TPSE in (11) on the nuisance parameter is explicit. Tutz proposes several data-driven criteria for determining optimal values of the nuisance parameter . Note that an optimal value must be estimated in an additional step to obtain item difficulty estimates with the most favorable properties [23].

The following Section 3 investigates the bias of the item difficulty estimate produced by the TPSE as a function of and discusses the optimal choice of this parameter to minimize bias in the estimated item difficulties. The focus is not on determining optimal values in concrete samples; instead, an optimistic best-case choice of that minimizes the average absolute bias in item parameter estimates is considered. It is shown that even in this best-case scenario, the TPSE yields substantially biased item parameter estimates, rendering the estimator rarely suitable for empirical research.

3. Bias Derivation of the Tutz’s Pairwise Separation Estimator (TPSE) in the Rasch Model

In this section, the bias in the estimated item difficulties obtained from the TPSE is examined. The asymptotic properties of the TPSE were not thoroughly investigated in [23]. Furthermore, the original source did not provide a convincing simulation study demonstrating satisfactory asymptotic behavior of the proposed estimator. Instead, the TPSE was introduced in a largely heuristic manner.

This section derives the bias in the case of the logistic link function , which corresponds to the Rasch model. If satisfactory statistical properties cannot be obtained in this setting, similar issues can be expected for other link functions in HM models. In the following derivation, the bias in item parameter estimates is assumed to be derived under the condition that follows an unknown distribution under random sampling [25]; that is, is integrated out. The item difficulty estimate in (11) depends critically on the quantities for item pairs . These quantities, in turn, rely on the sample proportions (see (10)), representing the proportion of persons who answered item i correctly and item j incorrectly.

Assume that the sample proportions converge to the corresponding population probabilities . Further assume that these probabilities are obtained in the Rasch model for persons with identical ability . Then, the corresponding population quantity can be expressed as

where the function H is introduced for convenience. Note that .

Using the notation , the TPSE expression in (10) becomes, for the Rasch model,

The quantity is intended to estimate the difference . Hence, it is essential to evaluate the right-hand side of (13) and determine how it deviates from the target quantity . Importantly, there cannot exist a unique value of such that the right-hand side of (13) equals . Otherwise, there would exist a value of for which for all real values of x, which is impossible because tanh does not have a constant derivative.

To gain further insight into the emergence of bias in the item parameter estimates of the TPSE, a Taylor expansion of H around up to third order based on the tanh function is employed. Terms up to third order are used to simplify the presentation and to highlight the main contributors to the bias when item difficulty differences do not deviate too strongly from 0. The Taylor approximation of H is given by

To quantify the bias in , the biasing term in the item-pair estimate for pair is defined as

Using the Taylor expansion in (14) gives

The expression in (16) can now be used to derive the bias in the estimated item difficulties of the TPSE. From (11),

Hence, the bias simplifies to

which further reduces, using , to

where for denote the first two moments of the distribution of true item difficulties .

The bias Formula (19) highlights the factors that influence the bias. Because is larger than 0 for , this component of the bias occurs whenever differs from 0; that is, when the average item difficulty is not equal to 0. This contribution can be reduced by selecting a reference item with such that becomes 0. This is likely achieved by choosing an item with medium item difficulty. Under the condition , must be chosen to balance the effects of and in (19). However, it becomes clear that no universal choice of can produce a bias of 0 for for all possible values of .

Assuming in (19) gives

A possible strategy for selecting in a given test is to minimize

where the expectation is interpreted as averaging across a (hypothetical) distribution of item parameters.

If all item difficulties are substantially smaller than 1 in absolute value, the linear term in (20) dominates. In this case,

3.1. Bias of the TPSE Under a Uniform Distribution of Item Difficulties

To illustrate (22), assume that the true item difficulties follow a uniform distribution on . Then and , which yields . For , this gives and . For , the values are and . For , the values are and . For , the result is and .

Now consider the more general case in which the term in (20) cannot be neglected, while still assuming that . The bias in the estimated difficulties is again illustrated under the assumption that item difficulties follow a uniform distribution on . Further assume that . Define and consider the range . Under these conditions, the average absolute bias takes the form

The optimal value of is given by

with . The minimum value of the average absolute bias is

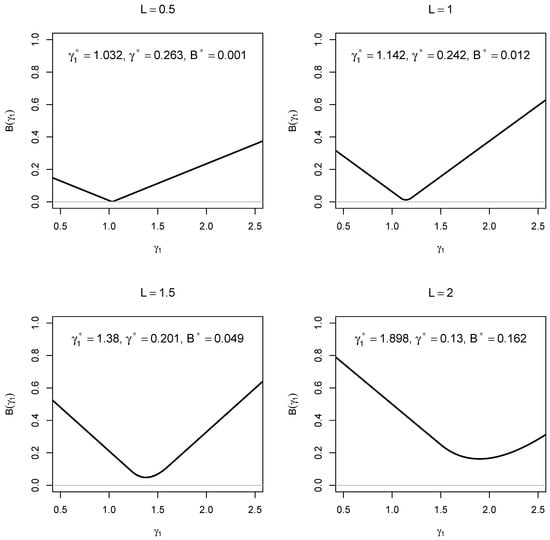

Evaluating (25) yields the following numerical values. For , the results are , , and . For , the values are , , and . For , the results are , , and . For , the values are , , and .

To validate the analytical derivations, was also evaluated numerically to identify optimal values. Figure 1 presents the corresponding average absolute bias as a function of , and the numerical optimization of with respect to coincided with the analytical results.

3.2. A Modified TPSE

A slight modification of the TPSE is now introduced that eliminates the bias component arising when the constraint is not satisfied. The core issue is that selecting the reference item such that the first item difficulty is essential for ensuring compliance with this sum constraint.

The modified TPSE is defined as

where the estimated item difficulties correspond to those obtained from the original TPSE as defined in (11). Using (26) yields

This modified TPSE guarantees and removes the bias component introduced by violating the sum constraint under an arbitrary choice of the item-difficulty metric.

3.3. Summary

The analytical derivation shows that item difficulties in the Rasch model can be biased when applying the TPSE, even if optimal values of the nuisance parameter (and equivalently ) are selected. Choosing an item with average item difficulty as the reference item, with , is essential to ensure that the average item difficulty equals 0, a condition that is preferable for achieving the least biased estimates. In addition, the appropriate value of depends critically on the distribution of item difficulties. For more dispersed distributions, smaller values of are required, and the resulting TPSE-based item difficulty estimates exhibit greater bias. Importantly, no universal value of can yield unbiased item difficulty estimates for all possible values of the true item difficulties. This limitation reduces the appeal of the TPSE for use in empirical research.

4. Numerical Illustration

In this Numerical Illustration, the performance of the TPSE under essentially infinite sample sizes is examined. This setup allows an investigation of whether TPSE estimates are consistent.

4.1. Method

The Rasch model served as the data-generating model for examining the TPSE. The ability variable was assumed to follow a normal distribution with mean and standard deviation . The mean was set to 0, 0.5, or 1.0, and the standard deviation was set to either 1 or 0.0001. The latter choice resulted in a distribution concentrated at the point .

The simulation study included items. The average item difficulty was varied as 0, 0.4, and 0.8. In the condition , the item difficulties were specified as 0.000, −1.500, −1.125, −0.750, −0.375, 0.000, 0.375, 0.750, 1.125, and 1.500. For the conditions and , the item difficulties for all items except the first were obtained by adding to the previously listed values to ensure the desired average difficulty, with the first item difficulty fixed at .

The sample size was fixed at , representing an approximation to the population. This setup renders the simulation essentially a numerical experiment for assessing bias of the TPSE under (almost) infinite sample sizes.

In each of the 3 (mean ) × 2 (standard deviation ) × 3 (average item difficulty ) simulation conditions, 3000 replications were conducted. Using this large number of replications and the very large sample size results in negligible Monte Carlo error in the simulation. The TPSE was applied for values between 0.005 and 0.495 in steps of 0.005. For all values, the bias of the item parameter estimates was computed. Consistent with the data-generating model, the first item difficulty was fixed at 0, so the first item served as the reference item. To summarize bias across items, the average absolute bias in the estimated item difficulties was calculated. An optimal value, denoted by , was determined separately for each simulation condition by selecting such that the average absolute bias in the estimated item difficulties was minimized. Consequently, the TPSE parameter estimates were obtained under a highly optimistic best-case scenario in which sampling variability does not affect the parameter choice. Under empirical conditions, a data-driven choice of cannot be expected to improve the performance of the TPSE.

All analyses in this Numerical Illustration were carried out in the statistical software R (Version 4.4.1; [26]). A custom R function was used to compute the TPSE. Replication material for this Numerical Illustration is available at https://osf.io/ef8nm (accessed on 21 November 2025).

4.2. Results

The results of the TPSE item parameter estimates for this Numerical Illustration are now presented.

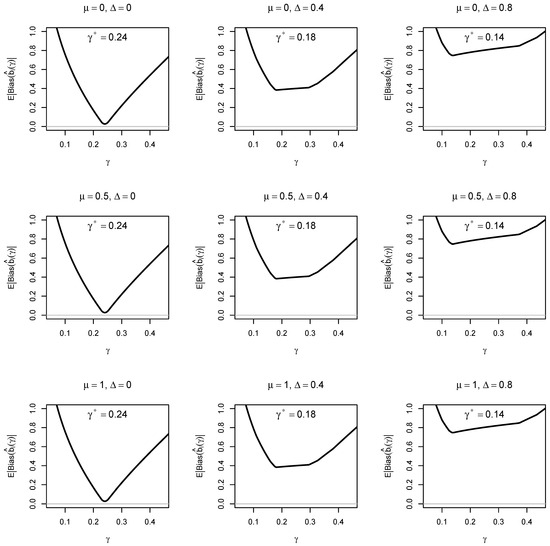

Figure 2 displays the average absolute bias in item difficulties as a function of , the mean , and the average item difficulty , for a standard deviation of 1. The average absolute bias was close to 0 when the average item difficulty equaled 0. The dependence on the mean was negligible. An optimal value of was obtained, yielding . The resulting average absolute bias was 0.026, which is small but still notably greater than 0.

Figure 2.

Numerical Illustration: Average absolute bias of estimated item difficulties as a function of for different means , true average item difficulties for . The minimal value is denoted by .

When the average item difficulty differed from 0, substantial biases occurred, and the search for an optimal did not yield practically unbiased estimates. These results align with the bias derivation in Section 3, which highlights the importance of fixing the reference item difficulty at 0 in such a way that the average item difficulty equals 0.

Table 1 reports the bias in item difficulties for the optimal parameters that minimized the average absolute bias. The estimated item difficulties show only small biases in the conditions with . However, even in this best-case scenario, an absolute bias of 0.056 occurred for item difficulties −1.500 and 1.500. The bias increased substantially in the conditions with , where the average item difficulty differed from 0. In these situations, the TPSE has almost no practical value for empirical applications. The general pattern of results in Table 1 is essentially independent of the mean and the standard deviation of the ability variable .

Table 1.

Numerical Illustration: Bias in estimated item difficulties using optimal values as a function of mean , true average item difficulties , and standard deviation .

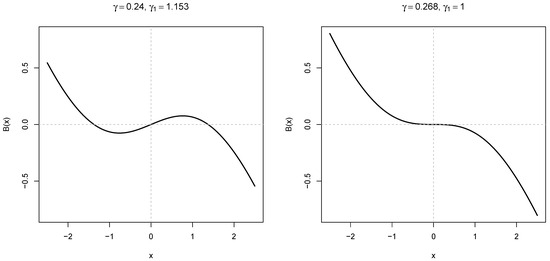

For the best-case scenarios with , Table 1 shows positive and negative biases for negative item difficulties, suggesting at first glance that no consistent pattern exists. This behavior can be understood by examining the bias function B (see its definition in (15)) presented in Section 3. This function is central to the TPSE because it characterizes the bias in differences of estimated item difficulties.

Figure 3 displays the function B for the optimal value . The curve oscillates, with negative bias for slightly negative values of x and positive bias for more strongly negative values of x. This pattern aligns precisely with the bias structure observed in Table 1 for the condition.

Figure 3.

Bias function B (see definition in (15)) for two different (and ) values.

5. Empirical Example

In this section, item parameter estimates from the TPSE for the Rasch model are compared with alternative parameter estimation methods using an empirical example. The dataset MathExamp14W, included in the R package psychotools (Version 0.7-5; [27]), is analyzed. It contains item response data from 729 students on 13 items from a written introductory mathematics examination (i.e., the course “Math 101”) [28].

The Rasch model was fitted using several estimation methods. Marginal maximum likelihood (MML; [9]) estimation was conducted with the tam.mml() function in the R package TAM (Version 4.3-25; [29]). Conditional maximum likelihood (CML; [9]) estimation was implemented using the immer_cml() function in the R package immer (Version 1.5-13; [30,31]). Composite conditional maximum likelihood (CCML; [21,32]), another approach based on a pairwise estimation principle, was specified using the immer_ccml() function, also included in the R package immer (Version 1.5-13; [30]). The row averaging (RA; [17]) approach was implemented with the pair() function in the R package pairwise (Version 0.6.2-0; [33]). The TPSE used the item implicit as the reference item and was evaluated over a discrete grid of values ranging from 0.10 to 0.40 in increments of 0.005. All item parameters are reported using centering; that is, the item difficulties sum to zero. The optimal value for the TPSE was selected by minimizing the average absolute difference in item parameter estimates between the CML and TPSE methods.

Standard errors for all item parameters were obtained using a nonparametric bootstrap [34], with the standard deviation of the estimates across bootstrap samples used as the standard error estimator. The bootstrap approach was also applied to compute standard errors for differences in item parameter estimates across estimation methods [35]. These standard errors were further used to assess whether item parameters differed significantly from zero for two estimation methods. Note that the bootstrap approach automatically accounts for the fact that model parameter estimates are obtained from the same dataset, which induces dependence among the parameter estimates.

Table 2 presents the item parameter estimates together with their standard errors for the example dataset. The CML and MML estimates were very close to each other, with the exception of the eighth item (“payflow”). Notably, the correlations of item parameter estimates among the CML, MML, CCML, and RA methods all exceeded 0.9995. In contrast, the correlations between TPSE item parameter estimates and those from the other estimation methods ranged from 0.9934 to 0.9962. Although these correlations are still relatively high, they are substantially lower than the correlations observed among the other estimation methods. The optimal parameter for the TPSE was estimated as 0.235.

Table 2.

Empirical Example: Item parameter estimates and standard errors.

The standard errors of the TPSE item parameter estimates were, on average, slightly larger than those for CML and MML, indicating that no efficiency gains are achieved with the TPSE. The largest difference between TPSE and CML was observed for the eighth item, payflow, and this item parameter difference was also statistically significant. Overall, 8 out of 13 items exhibited significant parameter differences between the CML and TPSE estimates. In contrast, although the parameter differences between CML and MML were very small, the corresponding standard errors were also small, reflecting the high correlation between item parameter estimates from the two methods.

Overall, with the exception of one item, the TPSE estimates do not differ strongly from those obtained with competing estimators. Nevertheless, the question remains why the biased and inconsistent TPSE should be used in empirical research, given that it also does not reduce variance.

6. Discussion

Recently, Tutz proposed the Tutz’s pairwise separation estimator (TPSE; [23]), which builds on the idea that person and item parameters can be separated in HM IRT models. However, ref. [23] provided neither a consistency proof nor a convincing large-sample simulation study demonstrating adequate statistical properties of the estimator in HM models.

This article shows that the TPSE does not offer a meaningful generalization of existing pairwise estimation methods in the Rasch model, which represents a special case of HM models. Analytical and numerical evidence for the Rasch model indicates that the TPSE will generally be biased in large samples, implying that the estimator does not yield consistent parameter estimates. The bias in estimated item difficulties depends critically on the choice of the reference item whose difficulty is fixed at 0. This reference item must be selected so that the average item difficulty equals 0; otherwise, substantial bias occurs. Even in this best-case scenario, the bias increases as the distribution of true item difficulties becomes wider. As a result, the TPSE is least suited for tests that include both very easy and very difficult items. It should be noted that, due to the inconsistency property, the usefulness of the TPSE is questionable. In the HM model, marginal maximum likelihood or Bayesian estimation of item parameters may be preferred. For the Rasch model, these estimators can also be applied or if approaches that do not require specification of the distribution are preferred, conditional maximum likelihood or pairwise estimation approaches [22].

It should be emphasized that this paper critiques only the use of the TPSE and not pairwise estimation approaches for the Rasch model in general. The literature has shown that consistent item parameter estimators in the Rasch model can be obtained using alternative estimators, such as those presented in the empirical example in Section 5.

This study was limited to dichotomous items, whereas [23] also considered polytomous items. Nevertheless, it is unlikely that the unsatisfactory behavior of the TPSE in the dichotomous case would fail to carry over to polytomous items.

The analytical derivation relied on a Taylor approximation up to third order for the tanh function involved in the bias of estimated item difficulties. Precision could be increased by including additional terms in the Taylor expansion. However, it remains impossible to select a universal value of the nuisance parameter that yields unbiasedness for all possible values of the true item difficulties. The derivation presented in the present paper should therefore be viewed as a rough approximation of the bias, intended to provide insight into the general behavior of the TPSE. Nevertheless, the analytical results obtained from the approximation were supported by an Numerical Illustration that does not rely on any approximation.

Importantly, the inconsistency of the TPSE item parameter estimates also persists when the number of items tends to infinity. The TPSE continues to rely on ratios of sample proportions for item pairs, and the analytical derivations presented in this article do not depend on the number of items. As a result, the conclusions remain valid even in the limit of an infinite item set.

It cannot be expected that the bias disappears in more general HM models. The substitution of unknown item probabilities by pseudo-observations in the TPSE becomes even more critical when asymmetric link functions F are used. This conclusion follows from the behavior of the TPSE in the Rasch model for items with extreme positive or negative difficulties.

Pairwise estimation approaches are often motivated by the appealing feature that no distributional assumption for the variable is required, nor is a simultaneous estimation of person and item parameters. However, HM models can also be estimated using marginal maximum likelihood methods, and the distribution can be specified in a semiparametric manner (e.g., as in [36,37,38,39]) for a known link function F in the HM model.

Tutz [23] noted in the original paper on the TPSE that

[…] To this end an estimator is derived that uses pseudo observations and can be derived as a smoothing estimator. We do not claim that this is the only possible or best estimator. There might be much better ones that estimate parameters without reference to the other group of parameters.

He even concedes that the TPSE were the “best” estimator. This statement represents a notable understatement given the poor statistical performance of the TPSE in the simplest case of the Rasch model, as demonstrated in the present article. Because the TPSE performed unsatisfactorily even under the Rasch model, satisfactory properties for more complex HM models appear unlikely. Consequently, this estimator cannot be generally recommended for empirical research. Based on these findings, no plausible scenarios in empirical research can be identified in which the TPSE would be preferred over alternative estimators. It remains an open question for future research whether an estimator with satisfactory statistical properties based on the principle of parameter separation can be derived for the HM model, although I am skeptical that this is feasible.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank three anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments that helped improve the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCML | composite conditional maximum likelihood |

| CML | conditional maximum likelihood |

| HM | homogeneous monotone |

| IRF | item response function |

| IRT | item response theory |

| MML | marginal maximum likelihood |

| RA | row averaging |

| TPSE | Tutz’s pairwise separation estimator |

References

- Bock, R.D.; Gibbons, R.D. Item Response Theory; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Ying, Z. Item response theory—A statistical framework for educational and psychological measurement. Stat. Sci. 2025, 40, 167–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, F.M.; Novick, R. Statistical Theories of Mental Test Scores; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Lord, F.M. Applications of Item Response Theory to Practical Testing Problems; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutz, G. A Short Guide to Item Response Theory Models; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linden, W.J. Unidimensional logistic response models. In Handbook of Item Response Theory, Volume 1: Models; van der Linden, W.J., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; pp. 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Rasch, G. Probabilistic Models for Some Intelligence and Attainment Tests; Danish Institute for Educational Research: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, B.D.; Stone, M.H. Best Test Design; Mesa Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1979; Available online: https://bit.ly/38jnLMX (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Fischer, G.H.; Molenaar, I.W. (Eds.) Rasch Models: Foundations, Recent Developments, and Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linacre, J.M. Understanding Rasch measurement: Estimation methods for Rasch measures. J. Outcome Meas. 1999, 3, 382–405. Available online: https://bit.ly/2UV6Eht (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- von Davier, M. The Rasch model. In Handbook of Item Response Theory, Volume 1: Models; van der Linden, W.J., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; pp. 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, H. Consequences of using the Rasch model for educational assessment. Brit. Educ. Res. J. 1979, 5, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, H.; Wood, R. Five decades of item response modelling. Brit. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 1989, 42, 139–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, G.H. Rasch models. In Handbook of Statistics, Vol. 26: Psychometrics; Rao, C.R., Sinharay, S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 515–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballou, D. Test scaling and value-added measurement. Educ. Financ. Policy 2009, 4, 351–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linden, W.J. Fundamental measurement and the fundamentals of Rasch measurement. In Objective Measurement: Theory Into Practice; Wilson, M., Ed.; Ablex Publishing Corporation: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1994; Volume 2, pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Choppin, B. A fully conditional estimation procedure for Rasch model parameters. Eval. Educ. 1982, 9, 29–42. Available online: https://bit.ly/3gFGQ0v (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Garner, M. An eigenvector method for estimating item parameters of the dichotomous and polytomous Rasch models. J. Appl. Meas. 2002, 3, 107–128. Available online: https://bit.ly/3gKp8ZN (accessed on 21 November 2025). [PubMed]

- Heine, J.H.; Tarnai, C. Pairwise Rasch model item parameter recovery under sparse data conditions. Psychol. Test Assess. Model. 2015, 57, 3–36. Available online: https://bit.ly/3sUICzC (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Heine, J.H.; Robitzsch, A. Evaluating the effects of analytical decisions in large-scale assessments: Analyzing PISA mathematics 2003–2012. Large-Scale Assess. Educ. 2022, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwinderman, A.H. Pairwise parameter estimation in Rasch models. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1995, 19, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robitzsch, A. A comprehensive simulation study of estimation methods for the Rasch model. Stats 2021, 4, 814–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutz, G. Invariance of comparisons: Separation of item and person parameters beyond Rasch models. J. Math. Psychol. 2024, 122, 102876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutz, G. Invariance of comparisons: Separation of item and person parameters beyond Rasch models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.03048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, P.W. On the sampling theory foundations of item response theory models. Psychometrika 1990, 55, 577–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2024. Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Zeileis, A.; Strobl, C.; Wickelmaier, F.; Komboz, B.; Kopf, J.; Schneider, L.; Debelak, R. psychotools: Psychometric Modeling Infrastructure, 2025. R Package Version 0.7-5. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/psychotools/index.html (accessed on 21 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zeileis, A. Examining exams using Rasch models and assessment of measurement invariance. Austrian J. Stat. 2025, 54, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robitzsch, A.; Kiefer, T.; Wu, M. TAM: Test Analysis Modules, 2025. R Package Version 4.3-25. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/TAM/index.html (accessed on 28 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Robitzsch, A.; Steinfeld, J. immer: Item Response Models for Multiple Ratings, 2024. R Package Version 1.5-13. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/immer/index.html (accessed on 21 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Robitzsch, A.; Steinfeld, J. Item response models for human ratings: Overview, estimation methods, and implementation in R. Psychol. Test Assess. Model. 2018, 60, 101–138. Available online: https://bit.ly/3mFnn3U (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- van der Linden, W.J.; Eggen, T.J.H.M. An empirical Bayesian approach to item banking. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1986, 10, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, J.H. pairwise: Rasch Model Parameters by Pairwise Algorithm, 2025. R Package Version 0.6.2-0. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pairwise/index.html (accessed on 12 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Efron, B.; Tibshirani, R.J. An Introduction to the Bootstrap; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robitzsch, A.; Lüdtke, O. Mean comparisons of many groups in the presence of DIF: An evaluation of linking and concurrent scaling approaches. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 2022, 47, 36–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leeuw, J.; Verhelst, N. Maximum likelihood estimation in generalized Rasch models. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 1986, 11, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolucci, F. A class of multidimensional IRT models for testing unidimensionality and clustering items. Psychometrika 2007, 72, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, B.; Clogg, C.C.; Grego, J. Semiparametric estimation in the Rasch model and related exponential response models, including a simple latent class model for item analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1991, 86, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Davier, M. A general diagnostic model applied to language testing data. Brit. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2008, 61, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.