Abstract

Ensuring optimal food hygiene is essential for food safety and preventing foodborne illness, although the importance of food hygiene is often overlooked in the household kitchen setting. Adequate, good hygiene practices in the domestic environment are equally important as their implementation in any other food preparation environment, like in the food industry. The current review encompasses research data on the prevalence and isolation of major foodborne pathogenic bacteria (Campylobacter, Salmonella, Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli pathotypes, and Clostridium perfringens) from household kitchen equipment, as well as food cleaning utensils used in the kitchen, such as sponges, brushes, dishcloths, and hand towels. The most common bacterial pathogen present in the domestic environment is S. aureus. The latter can be transmitted orally, either via direct hand contact with contaminated kitchen surfaces and/or cleaning utensils, or indirectly through the consumption of contaminated food due to cross-contamination during food preparation (e.g., portioning prepared meat on the same cutting board surface and with the same knife previously used to cut fresh leafy vegetables). Moreover, research findings on the hygiene of food cleaning utensils demonstrate that (i) sponges have the highest microbial load compared to all other cleaning utensils, (ii) brushes are less contaminated and more hygienic than sponges, thus safer for cleaning cutlery and kitchen utensils, and (iii) kitchen dishcloths and hand towels positively contribute to cross-contamination since they are frequently used for multiple purposes at the same time (e.g., drying hands and wiping/removing excess moisture from dishes). Finally, the present review clearly addresses the emerging issue of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in bacterial pathogens and the role of the domestic kitchen environment in AMR dissemination. These issues add complexity to foodborne risk management, linking household practices to broader AMR stewardship initiatives.

1. Introduction

Foodborne diseases represent a major global public health challenge, contributing to substantial morbidity, mortality, and socioeconomic losses worldwide [1,2]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 600 million people suffer from foodborne illnesses annually, leading to approximately 420,000 deaths, with children under five years of age disproportionately affected [3] (p. 72). The most recent assessment by the WHO Foodborne Disease Burden Epidemiology Reference Group (FERG) further highlights that foodborne diseases remain pervasive globally, accounting for millions of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and continuing to pose a considerable strain on public health systems [4]. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recently updated their 2011 estimates [5], reporting that six major pathogens (Norovirus, Campylobacter spp., Salmonella spp., Clostridium perfringens, Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli, STEC, and Listeria monocytogenes) are responsible for millions of illnesses annually, including hospitalizations and deaths, stressing the persistent burden of foodborne disease even in settings with advanced surveillance capacity and food safety infrastructures [6]. Furthermore, pan-European surveillance data from the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) [7] and the joint European Food Safety Authority and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (EFSA & ECDC) annual zoonoses report [8], consistently identify microbial hazards such as Salmonella, L. monocytogenes, and pathogenic E. coli in foods, demonstrating the ongoing challenge at the regional level. National agencies like the French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health and Safety (ANSES) have compiled datasheets specifically on domestic hygiene, recognizing the home as a critical place for control of foodborne biological hazards [9]. International organizations, including the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and WHO of the United Nations (UN), state that foodborne disease is not confined to acute gastrointestinal illness but also has long-term consequences, such as malnutrition, developmental impairments, and increased vulnerability to other infections [10]. To this end, the Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC) has long emphasized the necessity of fostering a proactive character in hygiene practices followed from primary production through to final consumption, thus preventing cross-contamination at any stage during food manufacturing/production or food preparation. In its basic texts for food hygiene, CAC has adopted this approach by highlighting, among others, the importance of interventions at the consumer level to minimize the risks for consumers of contracting foodborne diseases [11].

While much attention has been directed toward improving safety standards in food processing and retail, the domestic kitchen remains an overwhelmingly critical but often overlooked environment in the food chain [12,13,14,15]. Pathogens of global concern include Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., Clostridium perfringens, E. coli O157:H7, L. monocytogenes, and Staphylococcus aureus, all of which are commonly detected in domestic settings [3,16,17,18]. Additionally, other pathogenic bacteria closely related to the home kitchen environment, but to a lesser extent isolated from it, also include Bacillus cereus, which can produce emetic and diarrheal toxins in a variety of starch foods like rice and pasta [19,20,21,22], and Vibrio parahaemolyticus, which is of great concern in seafoods and can spread via cross-contamination on kitchen surfaces [23,24]. Studies increasingly recognize the home as a high-risk environment, where unsafe consumer behaviors and contaminated equipment contribute to the persistence and spread of foodborne pathogens [16,25]. Cross-contamination within kitchens, involving both food-contact and non-food-contact surfaces, has been identified as one of the most important routes of pathogen transmission to ready-to-eat (RTE) foods [26,27].

The microbial ecology of domestic kitchens is characterized by diversity, persistence, and adaptability of microorganisms. High-throughput sequencing techniques have revealed a complex bacterial community inhabiting kitchen surfaces, utensils, and cleaning tools, reflecting frequent interactions between humans, food, and the surrounding environment [28,29]. Importantly, pathogenic bacteria like Salmonella spp., L. monocytogenes, and S. aureus have been shown to persist in these environments due to their ability to survive desiccation, attach to surfaces, and form biofilms [30,31,32]. These adaptive mechanisms reduce the efficacy of routine household cleaning and disinfection, enabling pathogens to persist in abiotic surfaces (e.g., cutting boards, sink drains, dish sponges) [33,34].

The persistence of foodborne pathogens in domestic environments also highlights the problem of risk perception among consumers; while many individuals express awareness of foodborne risks, there is often a disconnect between knowledge and observed behavior [35]. Observational and survey-based studies reveal that poor hygiene practices are widespread, including inadequate handwashing, improper separation of raw and RTE foods, and reliance on visual cleanliness as a proxy for hygiene [36,37,38]. For example, sponges and dishcloths are frequently reused across multiple cleaning tasks, inadvertently spreading bacteria between food-contact surfaces and utensils [39,40,41]. Similarly, improper storage practices in domestic refrigerators, such as overloading of shelves with food products, infrequent cleaning, and operation at non-recommended temperatures, have been strongly linked to the persistence of L. monocytogenes and other psychrotrophic and psychrophilic pathogens [42,43,44]. Comparable concerns apply to B. cereus and Vibrio species, which can tolerate chilling temperatures, persist on surfaces, and contaminate stored foods [45,46].

Furthermore, the domestic kitchen has been increasingly recognized as a potential reservoir for antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Several studies have detected antibiotic-resistant bacteria and resistance genes in household refrigerators, sponges, and surfaces, raising concerns about the contribution of domestic environments to the dissemination of AMR [47,48,49]. This is reinforced by global trade and changing consumption patterns, which can introduce resistant strains from diverse geographical origins into the kitchen environment [50]. This emerging dimension adds complexity to foodborne risk management, linking household hygiene practices to broader antimicrobial stewardship initiatives [51].

Taken together, the domestic kitchen is not merely a passive setting for food preparation but rather an active “arena” in the transmission of foodborne pathogens. The persistence of bacteria in household equipment, coupled with unsafe consumer practices, creates a conducive environment prone to contamination and cross-infections [52,53]. While substantial progress has been made in improving food safety across production and retail sectors, the home preparation environment remains the final and often weakest link in the food chain [12,54], where the need for consumer-level interventions into broader food safety strategies, behavioral change, household hygiene, and innovations in kitchen equipment and design is always present [55,56].

This review, therefore, examines bacterial foodborne pathogens prevalent in the domestic environment, the household kitchen equipment that harbors them, and the implications of these findings for public health by synthesizing evidence from microbiology, epidemiology, and consumer behavior.

2. Bacterial Foodborne Pathogens Prevalent in the Domestic Environment

Domestic kitchens comprise the reservoirs for not only well-known foodborne pathogenic bacteria, but also of emerging and opportunistic bacteria [27,28], as shown in Table 1. Bacterial persistence and resistance profiles suggest that household environments may contribute to the spread of AMR, further complicating food safety management at the consumer level [48,49].

Table 1.

Major bacterial foodborne pathogens in domestic kitchens: sources, reservoirs, and consumer-related risk factors for pathogen transmission.

2.1. Campylobacter spp.

Campylobacter spp. is among the leading causes of bacterial foodborne illness and has been frequently implicated in contamination events in domestic environments. Surveys have shown that raw poultry is the primary reservoir, and cross-contamination during handling and preparation in household kitchens plays a crucial role in the pathogenic species transmission [18,57]. The bacteria are capable of transferring from raw chicken to hands, utensils, cutting boards, and other surfaces, or even cooking salt used for seasoning, thereby contaminating RTE foods prepared in the same environment [17,58]. Contraindicated consumer practices, such as washing raw poultry meat in the kitchen sink or using the same utensils for raw and cooked RTE food without proper sanitation (i.e., cleaning and disinfection) of the latter, have been identified as significant contributors to cross-contamination incidents [59,73].

Temperature management is another important factor that must be given consideration in the control of campylobacters. Even if refrigeration significantly retards bacterial growth, it does not eliminate Campylobacter spp., which can persist in cold storage and contribute to the risk of infection when cross-contamination occurs [55,74]. Furthermore, research indicates that consumer knowledge of proper handling is often insufficient to prevent contamination events [41,75].

2.2. Clostridium Perfringens

C. perfringens is a leading cause of foodborne illness, frequently linked to cooked meat and poultry products that have undergone improper cooling in domestic and retail settings [5,76]. The bacterium is a spore-former, and its spores can survive cooking temperatures. Upon cooling, unless the temperature decrease is rapid, spores can germinate, and the resulting vegetative cells can easily multiply within the temperature danger zone (between 5 °C and 60 °C) [61,77]. This risk is particularly acute in home kitchens where large portions of food like stews, gravies, and roasted meats are prepared and then stored in inadequate refrigeration conditions [60]. C. perfringens Type A is the primary agent of food poisoning, with the enterotoxin gene (cpe) located on either the chromosome or a plasmid [78,79]. The pathogen has been detected in home kitchen environments, including kitchen surfaces, indicating its potential for introduction into the food preparation area [62].

2.3. Escherichia coli Pathotypes

E. coli is a diverse bacterial species with several pathogenic phenotypes implicated in foodborne diseases. The most prominent are STECs, with enterohemorrhagic E. coli serotype O157:H7 being well-recognized for causing a serious blood disorder (hemolytic uremic syndrome), leading to kidney failure. Other syndromes manifested by E. coli pathotypes include urinary tract infections, different forms of diarrhea (e.g., bloody, watery, traveler’s diarrhea), and systemic infections (e.g., sepsis, meningitis), depending on the E. coli strain and location of the infection [80]. Cross-contamination in domestic kitchens has been identified as a major transmission pathway for these bacterial strains [63,81,82].

Research demonstrates that pathogenic E. coli O157:H7 can be transferred from contaminated vegetables and raw meats to kitchen surfaces, sponges, and cloths, where it can persist for extended periods [34,40]. Practices such as reusing kitchen sponges and dishcloths for multiple tasks contribute additionally to the persistence of E. coli in home kitchens [39,83]. The presence of antibiotic-resistant E. coli in frozen foods further complicates the issue, raising public health concerns regarding resistant strains in household environments [47]. The risks posed by E. coli presence in the domestic environment further enlarge the importance of safe handling, adequate cleaning, and disinfection of utensils and surfaces, and consumer awareness for cross-contamination pathways in food preparation at home [14,16].

2.4. Salmonella spp.

Salmonella spp. represents one of the most significant bacterial pathogens associated with foodborne outbreaks and has been repeatedly isolated from domestic environments [16,18]. Poultry, eggs, and raw meat products are common reservoirs of salmonellae, and handling these products in kitchens introduces substantial risks [84,85]. Studies have documented the persistence of Salmonella on cutting boards, dishcloths, and sponges, with evidence of recurrent cross-contamination events from raw to RTE food products [26,72].

Poor consumer practices, for instance, improper sanitation of utensils and inadequate cooking, exacerbate the risk of salmonellosis in the home [86,87]. Besides, as already known, refrigeration does not eliminate Salmonella, resulting in domestic refrigerators contaminated with the pathogen [69,88]. Field surveys also demonstrate that Salmonella biofilms can form on surfaces, enhancing persistence and complicating any control efforts in the domestic setting [31,89].

2.5. Staphylococcus aureus

S. aureus represents part of the natural microbiota encountered in the human skin and body cavities of people. Hence, S. aureus is the most prevalent bacterial species in domestic environments [43,90], due to the usual direct hand contact of food surfaces, equipment, and utensils occurring in homes, whereas it is a major pathogen of concern because of its ability to produce enterotoxins responsible for food poisoning incidents [70,91]. Different studies have shown that coagulase-positive staphylococci and S. aureus can persist on surfaces, dishcloths, sponges, and within refrigerators, with isolates often carrying genes associated with toxin production [32,71,72].

Cross-contamination occurs both directly, through contact with contaminated surfaces, and indirectly, via human carriers who frequently transfer S. aureus through hand contact during food preparation [53,92]. The ability of the pathogen to form biofilms further increases its persistence and survivability on domestic surfaces and utensils [93,94]. In addition, studies indicate that poor household cleaning practices are insufficient to eliminate S. aureus, particularly when sponges and dishcloths are reused without prior disinfection [39,41].

2.6. Listeria monocytogenes

L. monocytogenes is a psychrotrophic pathogen capable of surviving and multiplying at refrigeration temperatures. The organism is rather prevalent in domestic kitchens. In that context, several studies have documented for many years the presence of Listeria spp. and L. monocytogenes in domestic refrigerators, demonstrating widespread contamination in consumer households [64,65,67,95]. Temperature fluctuations and inadequate cleaning of refrigerators contribute significantly to the pathogen’s persistence [42,66].

The microorganism’s ability to form biofilms allows for pathogenic Listeria spp. to colonize refrigerator surfaces, cutting boards, and countertops, where they can persist despite any cleaning attempts [30,96,97]. L. monocytogenes presence in RTE products further amplifies the risks in domestic environments [97,98]. Vulnerable populations such as the elderly and immunocompromised are especially at risk, as improper domestic practices may result in listeriosis outbreaks [99,100].

2.7. Other Bacterial Pathogens

In addition to the major pathogens, several other bacterial genera have been identified in domestic environments, species of which appear as opportunistic or emerging pathogens mostly associated with certain food categories. B. cereus is a significant spore-forming bacterium frequently linked to foodborne outbreaks, particularly associated with cooked rice, pasta, and other starchy foods that are often stored inadequately in domestic settings [19,20,21,22]. The spores produced by B. cereus are highly resistant and can survive cooking processes. Subsequent storage of cooked foods at ambient temperatures allows for spore germination and toxin production, leading to either emetic or diarrheal syndromes [19,45]. This risk is particularly acute in home kitchens where temperature control of prepared foods may be inconsistent. The pathogen has been detected in a wide range of food matrices, including spices and cooked rice from retail sources, confirming its relevance to the consumer level [22,101,102]. Furthermore, pathogenic Vibrio species, particularly V. parahaemolyticus, are primarily associated with seafood and represent a cross-contamination risk in kitchens during the handling of raw fish and shellfish [23,24]. This pathogen has been implicated in outbreaks originating from the contamination of kitchen surfaces and utensils after preparing seafood products [23,103]. Additionally, it can adhere to and form biofilms on surfaces, enhancing persistence, while resistance traits have been identified in isolates from seafood, raising further concern for domestic settings [104,105]. Although more commonly associated with powdered infant formula, Arslan & Ertürk [106] have recovered Cronobacter spp. from a variety of RTE foods. Thence, the possibility of detecting strains of the pathogen in the home kitchen setting should not be disregarded. Arcobacter spp. are considered emerging pathogens and have been linked to poultry products, and thus, they may contaminate household environments during the preparation of poultry meat [107,108]. Acinetobacter spp. are opportunistic bacteria with antimicrobial-resistant potential that have been isolated from food and water [109], further promoting the microbial diversity capacity encountered in home kitchens. Finally, the potential presence of Helicobacter pylori on raw vegetables and in water also indicates the kitchen’s role in the transmission of this widespread gastric pathogen [110,111,112].

3. Household Kitchen Equipment That Harbors Foodborne Pathogenic Bacteria

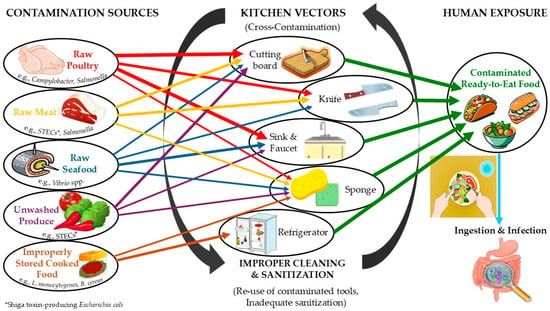

The major bacterial foodborne pathogens in descending order of prevalence, most commonly isolated from household kitchens, are S. aureus, Salmonella spp., and STECs. Other notable pathogens detected in the domestic environment include Campylobacter spp., C. perfringens, and L. monocytogenes. These bacteria can contaminate various kitchen surfaces, including sinks, countertops, and cutting boards, posing a risk for cross-contamination and foodborne illness (Table 2). A schematic representation of the aforementioned routes of contamination is depicted in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Household kitchen equipment harboring major bacterial foodborne pathogens and the associated consumer-related risk factors for pathogen transmission.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of contamination routes for foodborne pathogenic bacteria in the domestic environment. arrows with the same color represent the same contamination source.

Past and current research has demonstrated that a plethora of environmental conditions (e.g., microorganism species, surface moisture, contact surface type, surface material composition) influence bacterial survival and inactivation on kitchen equipment. Wooden surfaces may absorb and retain pathogens, resulting generally in fewer recoveries compared to surfaces made of plastic or stainless steel [119,120]. However, pathogens may remain viable on dry stainless-steel surfaces and comprise a contamination hazard for a considerable period of time, dependent on the contamination levels and microorganism species [40,121]. Novel surface modifications are being investigated nowadays for their potential to reduce microbial contamination [122,123,124,125,126].

3.1. Cutting Boards

Cutting boards are one of the most frequently reported kitchen items involved in bacterial cross-contamination incidents. Studies have consistently revealed that raw poultry, fresh or frozen meat, and fresh-cut produce prepared on cutting board surfaces can introduce, on the board and then in food, pathogenic bacteria like Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., and E. coli pathotypes [18,40,127,128,129,130]. The porous nature of wooden boards and the presence of extensive cracks and knife scars on plastic cutting boards, relevant to the use status of the board, provide space for bacterial attachment and biofilm formation, reducing in that way the efficacy of routine cleaning and disinfection procedures [113,131,132]. The suitability of wood against plastic, recommended as the appropriate material for crafting cutting boards for food preparation, has long been debated, primarily due to hygienic concerns related to the porous structure and hygroscopic nature of wood. Research suggests that wooden cutting boards from certain hardwoods (white ash, black cherry, red oak, sugar maple wood) possess bactericidal properties, leading to reduced microbial loads compared to plastic cutting boards [133,134]. Besides, research findings indicate that inadequate sanitation between uses can allow for persistence of microbial pathogens onto cutting boards and subsequent transfer to RTE foods, highlighting the latter as a major contamination source in household kitchens [16,26].

3.2. Kitchen Countertops and Other Surfaces

Countertops and surrounding surfaces play a central role in domestic food preparation and are frequently contaminated by raw food residues and cleaning tools as well. Bacterial survival on these surfaces is enhanced by biofilm formation and resistance to desiccation [30,31]. Research has shown that Salmonella spp., L. monocytogenes, and S. aureus can survive for extended periods on kitchen surfaces, posing risks when these areas are used for preparing RTE foods [13,15,18]. Visual cleanliness has been assessed as a poor indicator of microbial contamination [38], whereas the frequent use of dishcloths and sponges to wipe countertops increases contamination levels, often redistributing bacteria rather than mechanically removing them [34,39].

3.3. Kitchen Sink and Faucet

The sink and faucet in the kitchen are high-risk areas due to their frequent contact with raw food products, dishwashing water, contaminated hands, and utensils. In several studies, sinks have been identified as reservoirs for Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., and L. monocytogenes, particularly when raw poultry meat is washed prior to cooking [18,57]. Studies have also revealed that washing raw poultry directly in the sink results in extensive contamination of surrounding surfaces because of the splash dispersal of microbial droplets [59]. Faucets and drainage areas harbor biofilms that protect microbial pathogens against common cleaning and disinfection practices, contributing to their persistence and recontamination capacity [31,131].

3.4. Domestic Refrigerators

Given its psychrotrophic character, the bacterial pathogen reportedly found in domestic refrigerators is L. monocytogenes. The manifestation of the disease caused by this microorganism (listeriosis) confers serious complications (e.g., meningitis, sepsis) to human health or even death at a later stage. Other pathogens like S. aureus and various coliforms are also frequently isolated from domestic refrigerators.

Although the scope of domestic refrigerators is food preservation by controlling microbial growth and preventing food spoilage, numerous studies have reported microbial harborage of pathogens in the refrigerators due to inadequate refrigeration temperatures, poor hygienic status of the refrigerators themselves, and cross-contamination between raw and RTE stored foods [64,65,67]. Investigations in Europe and elsewhere have revealed that a significant proportion of household refrigerators operate above the recommended temperatures, allowing for an increased microbial growth rate, especially for psychrotrophic pathogens like L. monocytogenes [32,42,43,44]. Contamination by Salmonella spp. and S. aureus has also been documented, often associated with poor cleaning of the refrigerator and direct contact of raw, with RTE food inside the refrigerator [53,69,90].

As foods are often stored for prolonged periods and domestic refrigerators are rarely cleaned thoroughly or frequently, this further highlights the hygiene and safety issues that exist with the latter [135,136]. Additionally, resistant bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes have been isolated and detected in domestic refrigerators, highlighting their role as overlooked reservoirs with broader public health implications [48,49].

3.5. Food Cleaning Utensils

Food cleaning utensils include sponges, dishcloths, hand towels, and brushes, all of which have consistently been identified as the most contaminated items in household kitchens. Sponges in particular harbor dense and diverse microbial communities, among others, E. coli, S. aureus, and Salmonella spp. [117,118]. Their porous structure, constant exposure to moisture and storage under increased humidity, as well as nutrient residues absorbed on them, create an ideal environment for bacterial growth and persistence [33,34]. Sponges are more unhygienic than brushes due to the faster drying and reduced bacterial survival in brushes [41]. The design of cleaning brushes is also important, as brushes with hard bristles may introduce a risk of cross-contamination due to the splashing of bacteria into the air during cleaning [137]. When it comes to the hygiene of sponges, however, the use of polyurethane compared to cellulose sponges seems to have a better effect on reducing exposure to enterobacteria in the kitchen [138].

Dishcloths and hand towels also contribute significantly to cross-contamination, as their repeated use for drying hands, wiping surfaces, and cleaning dishes allows pathogens to spread widely across the kitchen [39,83,114]. Studies demonstrate that bacterial levels on dishcloths and towels increase significantly with prolonged use and inadequate laundering [115,116,118]. Although disinfection methods such as microwaving or chemical cleaning can reduce microbial loads, inconsistent consumer adoption of these practices limits their effectiveness [139,140].

3.6. Other Kitchen Appliances and Utensils

Communal kitchen environments have shown high levels of microbial contamination on shared appliances, pointing out risks in multi-user settings [141,142]. Additionally, knives, forks, blenders, bowls, and other utensils that come into direct contact with raw food have also been identified as potential vectors of cross-contamination when not adequately cleaned [75,117].

4. Discussion

Food hygiene is the cornerstone of food safety. Maintaining an appropriate level of food hygiene in terms of controlling cross-contamination in the food preparation environment is of paramount importance in assuring food safety. The present review demonstrates how the domestic kitchen environment can contribute to the development of persistence and the transmission of bacterial foodborne pathogens, with implications that extend far beyond individual households and signify broader public health outcomes. In the scientific literature, Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., coliform strains (e.g., E. coli O57:H7), L. monocytogenes, and S. aureus are repeatedly reported and consistently emerge as the most prevalent bacterial pathogens detected in domestic kitchens [16,17,18]. Besides these, bacteria like B. cereus, associated with cooked starchy foods, and V. parahaemolyticus, linked to seafood, present significant risks due to specific consumer handling practices [19,23]. Their ability to withstand and survive adverse environmental conditions under variable household practices (e.g., refrigeration of foods, mild or no disinfection of surfaces) underlines the importance of recognizing the domestic setting as an integral part of the food safety chain [14,15].

4.1. Food Consumer Behavior

One of the most consistent themes across studies is the role of consumer behavior in shaping microbiological risks. Practices such as washing raw poultry under running water in kitchen sinks, reusing sponges and dishcloths for multiple purposes, create favorable conditions for cross-contamination to occur [39,59,75]. Even when consumers express awareness of hygiene risks, observed behavior in domestic kitchens often contradicts stated knowledge, pointing to a gap between food safety awareness and its practical application [35,37]. Especially, regarding the handling practice of raw poultry, there is a common paradox concerning risk mitigation behavior in household kitchens stating that the higher consumer awareness might be about microbiological hazards, the more increased is the likelihood of washing raw poultry for these consumers [143].Therefore, effective consumer education programs that move beyond knowledge transfer to actually influencing and sustaining behavior change [144,145] need to be addressed by interventions that target consumer practices, including educational campaigns and behavior-focused strategies.

4.2. Hygienic Status of Food Cleaning Utensils and Kitchen Appliances

Another key issue highlighted herein is the persistence of pathogens in household equipment and kitchen appliances. Food cleaning utensils repeatedly appear as the most contaminated items, harboring diverse microbial populations; bacterial pathogens and food spoilage organisms among others [56,118,119]. The structural properties of those cleaning utensils and their frequent humid storage and use, as well as their organic load from food residues, allow bacteria to thrive, with sponges showing particularly high microbial loads when compared to brushes or towels [41,138]. Similarly, refrigerators have been identified as hotspots for contamination due to inadequate temperature control and poor cleaning frequency [43,64,135]. Studies indicate that refrigerators frequently operate above recommended storage temperatures, enabling the survival and even growth of psychrotrophic microbial pathogens [42,66,146,147,148,149].

4.3. Persistence of Foodborne Bacterial Pathogens in Home Kitchens

The capacity of foodborne pathogens to persist in the home kitchen environment is closely related to their adaptive mechanisms, which include biofilm formation and resistance to sanitizers, among others. Biofilm-associated persistence has been documented for L. monocytogenes, Salmonella spp., and S. aureus, making it difficult to eradicate these pathogens from household surfaces and utensils [30,94,96].

The frequent detection of microbial pathogens in cleaning tools, despite regular consumer washing of these tools, supports the importance of biofilm-mediated persistence [33,34]. Chmielewski & Frank [30] described how microbial pathogens attach to a variety of food-contact surfaces, form complex biofilm structures, and thereby gain protection from chemical and physical removal, which explains why biofilm-associated cells often persist at the expense of the more easily inactivated planktonic cells. In the case of L. monocytogenes, Norwood & Gilmour [150] observed robust biofilm formation on food contact surfaces, while Pan et al. [151] demonstrated that food-derived listerial strains readily establish biofilms that enhanced their resistance to cleaning and disinfection procedures. Rodríguez et al. [152] confirmed that Listeria biofilms displayed significant tolerance to disinfectants that are routinely applied in industrial sanitation protocols, regardless of surface roughness and stainless steel finish, whereas Ferreira et al. [96] further demonstrated that persistent isolates frequently possessed enhanced biofilm-forming abilities, allowing them to survive through repeated sanitation cycles and contribute to recurring contamination events. Most importantly, in alignment with previous data regarding interstrain variation in adherence [150], Borucki et al. [153] emphasized the fact that the biofilm-forming ability in L. monocytogenes varied by genetic lineage, indicating that Listeria lineage II possesses markedly greater adhesion capacity for surface colonization than other lineages, a genetic trait linked directly to the long-term persistence of L. monocytogenes strains of serotypes 1/2a and 1/2c (PCR-serogroups IIa and IIc) in food processing facilities. The biofilm-forming ability of S. aureus also represents an important persistence mechanism for the microorganism. Miao et al. [94] examined the stages of S. aureus biofilm development and described how biofilm-embedded cells displayed increased resistance to disinfectants and environmental stressors compared to their planktonic counterparts, hindering eradication efforts and facilitating survival on food-contact materials and domestic utensils. Smyth et al. [71] provided further evidence by identifying S. aureus isolates from Irish domestic refrigerators that not only carried novel enterotoxin genes but also exhibited clonal biofilm-forming capacity, linking virulence with persistence in household environments. For Salmonella spp., Lianou & Koutsoumanis [154] demonstrated strain variability on the biofilm-forming ability of Salmonella which was affected by three environmental parameters tested (pH, cell concentration, temperature), while Shi & Zhu [155] reported that Salmonella and E. coli biofilms formed on biotic and abiotic surfaces were more resistant to antimicrobials and environmental stressors than planktonic cells, underpinning the protective effect of biofilm matrices on pathogen survivability.

While biofilm formation is a critical persistence strategy for many pathogens, other bacteria, notably Clostridium and Bacillus species, rely on a fundamentally different and highly effective mechanism: the formation of metabolically dormant endospores. This strategy allows them to survive environmental extremes that would readily eliminate vegetative cells and biofilm-embedded populations. The persistence of Clostridium spp., particularly C. perfringens and C. botulinum, is primarily mediated by their ability to form highly resistant endospores, a protective, multi-layered coat that allows them to withstand harsh environmental conditions, including the high temperatures of cooking processes [156]. When these spores contaminate raw ingredients or are deposited on kitchen surfaces and utensils, they can survive and later be transferred to cooked foods. The critical control failure occurs during the subsequent cooling and storage phase [61,77]. For C. perfringens, this leads to high numbers of vegetative cells that, upon consumption, can produce enterotoxin in the human intestine. The strain’s resilience is further influenced by the genetic location of its enterotoxin gene (cpe), with chromosomal and plasmid-borne variants exhibiting different levels of resistance to environmental stresses like heat and osmosis, which can affect their survival on contaminated surfaces and in food residues [157,158]. Similarly, B. cereus employs spore formation to persist in the kitchen environment [20,45,102]. Like Clostridium spores, they can survive cooking; at ambient temperatures, the spores germinate, and the vegetative cells multiply, leading to the production of emetic or diarrheal toxins [20,45,102].

Mattick et al. [34] showed that during dishwashing practices taking place, pathogens transferred to sponges and kitchen surfaces were able to persist irrespective of the repeated character of cleaning, with biofilm formation likely enabling survival under conditions where non-adherent cells would otherwise be eliminated. Likewise, Kusumaningrum et al. [33] found that foodborne pathogens inoculated into domestic sponges survived exposure to antibacterial dishwashing liquid and co-existed with competitive microbiota, suggesting that biofilm structures facilitated the maintenance of diverse microbial populations under antimicrobial pressure. The aforementioned findings echo the conclusions of Ferreira et al. [96] that once biofilms are established in the food-associated environment, conventional cleaning measures applied fail to achieve full eradication. These findings are mirrored in studies on chlorine-based treatments. Singh et al. [159] evaluated peracetic acid, a chlorine-derived agent, on fresh produce surfaces and proved that while effective in reducing microbial loads, pathogens such as Salmonella and L. monocytogenes could persist under certain conditions, hence limiting the reliability of chlorine disinfection. Recently, Cuggino et al. [160] tested chlorine and peroxyacetic acid washes on Salmonella cells inoculated in fresh-cut lettuce and found that although initial reductions were achieved, surviving cells of the pathogen were capable of regrowth, demonstrating the adaptive capacity of foodborne pathogens to recover even after exposure to widely used commercial disinfectants.

4.4. AMR in the Domestic Environment

An emerging concern is the role of domestic kitchens in AMR dissemination, as bacterial persistence creates opportunities for the development and maintenance of AMR and antimicrobial resistance gene (ARG) transfer. Studies have identified antibiotic-resistant bacteria apart from foods, also in sponges, refrigerators, and kitchen surfaces, indicating the potential for household environments to act as reservoirs for resistance genes [47,48,49]. Baek et al. [47] reported that L. monocytogenes, Salmonella, and S. aureus isolates from frozen foods displayed significant resistance traits, with Salmonella exhibiting resistance to tetracycline and ampicillin, while certain L. monocytogenes strains were resistant to erythromycin. Extending this scope, Arslan & Ertürk [106] demonstrated that Cronobacter spp. from RTE foods were resistant to ampicillin, tetracycline, and cefotaxime, with β-lactamase genes detected as a genetic basis for the noted resistance. Márquez et al. [85] further reported AMR to tetracycline, ampicillin, and streptomycin, for Salmonella strains isolated from hen eggshells, with notable correlations among the different AMRs, suggesting the existence of cross-resistance mechanisms. In the domestic environment, Smyth et al. [71] identified S. aureus strains isolated from refrigerators in Ireland that were resistant to penicillin and erythromycin, while, at the same time, they notably carried novel enterotoxin genes. Scott et al. [91] provided one of the most characteristic examples of resistance to penicillins for staphylococci, by isolating methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) from domestic kitchens, noticeably pointing out that while some households showed no detectable contamination, others exhibited persistent MRSA strains across multiple surfaces. More recently, Soltanzadeh et al. [161] examined bacterial isolates from hospital refrigerators in Tehran, Iran, reporting resistance of E. coli strains to ciprofloxacin and ceftazidime, as well as resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae to imipenem and cefotaxime. Moreover, extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) genes were detected, confirming that these opportunistic pathogens not only resisted treatment with antibiotics but also carried transferable resistance determinants. A recent study on C. perfringens isolates from retail meat in Vietnam revealed significant multidrug resistance, including high-level resistance to clindamycin, erythromycin, and tetracycline [162]. While comprehensive data on specific ARGs in food-derived B. cereus is still emerging, strains have been frequently reported to exhibit resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics (e.g., ampicillin, penicillin) due to the production of beta-lactamases such as Bla1 and BlaZ, and occasionally to tetracycline mediated by tet genes [102].

The emergence and persistence of AMR in the domestic kitchen are significantly influenced by external factors, including global trade, importation of food products, and evolving consumer trends [50]. International trade in food commodities can introduce bacterial strains and resistance genes from diverse geographical origins and agricultural practices into home kitchens, challenging local containment efforts [8]. Furthermore, the growing consumer demand for varied, exotic, or minimally processed foods can increase exposure risks, as for example, RTE sprouts, salads, and microgreens that are often consumed raw, have been identified as vehicles for enteropathogenic bacteria, including resistant strains [163,164]. The rise in seafood consumption brings an associated risk of introducing resistant Vibrio species into the kitchen environment [104]. The domestic kitchen must therefore be recognized as a significant potential reservoir for AMR and ARGs, a threat amplified by its role at the convergence of global food supply chains and local consumption practices [8,47,48,49,50].

4.5. Towards Effective Consumer Awareness, Risk Management, and Guidelines for Food Hygiene Implementation

The cross-contamination pathways within kitchens represent a unifying mechanism that explains much of the persistence and distribution of bacterial pathogens in the domestic environment. Cross-contamination occurs when the pathogen’s microbial cells are transferred from raw food to RTE products, surfaces, or utensils, either directly or indirectly through hand contact, cloths, or sponges [26,165]. Evidence suggests that the majority of contamination incidents in kitchens are preventable, provided that consumers adopt simple but consistent hygiene measures; for instance, separating raw and RTE foods, cleaning utensils between uses, and maintaining adequate refrigeration [14,136].

Scientific literature also points to variability across households, with differences in contamination levels and consumer practices influenced by cultural, demographic, and socioeconomic factors. The persistence of unsafe practices across different cultural and socioeconomic contexts suggests that barriers to behavior change extend beyond knowledge deficits and may involve convenience, habit, or misperceptions of risk [36,166]. Older adults, for example, have been shown to engage in riskier storage and handling practices, increasing their vulnerability to listeriosis [99,100]. Similarly, households with children or multiple family members may face greater challenges in maintaining consistent hygiene due to frequent food preparation and shared appliance use [167].

The repeated observation of a gap between food consumer knowledge and its behavior in practice points out the critical need for effective, evidence-based education programs [35,37]. Successful interventions must be targeted, practical, and repetitive, moving beyond knowledge transfer to directly influence and sustain behavior change [144,145]. Effective strategies should focus on key risk factors, such as proper handwashing, rigorous separation of raw and RTE foods, maintenance of adequate cooking and cooling temperatures, and the correct use and sanitization of high-risk tools like sponges and cutting boards. Studies demonstrate that targeted cleaning and disinfection programs, improved refrigeration temperature control, and safer utensil design can substantially reduce contamination risks in household kitchens [131,137,148,168]. Disinfecting sponges through microwaving, frequent replacement, or replacing them with brushes, using antibacterial dishwashing liquids, and improving consumer awareness of high-risk behaviors are all alternative promising practices contributing to the reduction in microbial loads in the kitchen environment [33,139,140]. Furthermore, ergonomic considerations, including kitchen layout, equipment accessibility, and surface design, may indirectly influence consumer practices and enhance food safety outcomes [127,167,169]. These interventions suggest that household kitchens can be modified to reduce microbial risks through a combination of consumer behavior change and improved equipment design. Educational content must also evolve to include awareness of AMR risks associated with improper food handling. These messages should be disseminated through multiple ways, including digital media, packaging labels, and point-of-sale information, to reinforce safe food handling practices and foster a sustained culture of food safety in the home environment [9].

While formal Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) systems are mandated in industry, the home kitchen lacks such structured oversight and monitoring, placing the onus of risk management on the consumer itself [9,12,54]. The principles of risk analysis, however, can be adapted to inform domestic hygiene strategies. This involves a structured three step approach necessitating firstly to identify specific hazards (e.g., pathogenic bacteria on raw chicken, AMR bacteria on produce), then to assess for exposure routes (e.g., cross-contamination via cutting boards and sponges, undercooking) (Figure 1), and finally to characterize the health risk in order to determine the most critical control points (CCPs) in the home kitchen setting. National agencies, like the French ANSES, have developed detailed datasheets applying this risk-based approach to domestic hygiene, translating complex risk assessments into practical, prioritized advice for the public [9]. Communicating these CCPs clearly by emphasizing, for instance, the cleaning of surfaces after preparing raw poultry or the proper storage of cooked rice, can empower consumers to focus actions on practices that have the greatest impact on minimizing foodborne outbreaks.

As is already well known, household-level food safety depends largely on individual consumer practices rather than formal legislation, with those practices often being inconsistent and difficult to regulate [37,52]. Nevertheless, several authoritative national and international bodies provide science-based guidelines to direct consumer behavior. The WHO’s “Five Keys to Safer Food” (keep clean, separate raw and cooked food, cook thoroughly, keep food at safe temperatures, use safe water and raw materials) provides a foundational, internationally recognized framework [3]. The CAC also provides basic texts on food hygiene that underscore the importance of consumer-level interventions [11]. At a national level, agencies like ANSES offer more detailed guidance [9]. These resources, alongside reports from the RASFF and the EFSA & ECDC, which inform on emerging risks, should form the cornerstone of public health initiatives aimed at strengthening the final link in the food safety chain [7,8]. The goal is to provide consumers with clear, actionable, and authoritative advice to compensate for the lack of regulatory oversight in the domestic environment.

5. Conclusions

The existing literature reviewed herein underscores the importance of the domestic kitchen as a key, nonetheless underestimated, environment in the epidemiology of foodborne diseases. Despite significant technological advances in food production and processing, the persistence of microbial pathogens in households continues to compromise food safety at the consumer level [13,15]. Hence, pathogens like Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., pathogenic E. coli, S. aureus, and L. monocytogenes are constantly being isolated from the domestic environment, with their survival supported basically by the biofilm-forming ability of the bacteria and the poor consumer hygiene practices and/or the application of inadequate food hygiene measures [16,17,18].

Household equipment and cleaning utensils, namely sponges, dishcloths, cutting boards, countertops, sinks, and refrigerators, represent prominent reservoirs of bacterial prevalence and cross-contamination hotspots [33,39,43]. Especially the aforementioned utensils are repeatedly identified as the most contaminated items in kitchens, harboring dense microbial populations, many times hosting bacterial pathogens such as the ones previously reported, thus serving as vectors for bacterial spread [118,119] (Figure 1). Specifically, sponges present the highest microbial load compared to all other cleaning utensils, while brushes (with soft or medium bristles) are more hygienic than sponges and safer for cleaning kitchen cutlery and utensils [41,137]. Therefore, it is better to use brushes with soft bristles than sponges as food cleaning utensils in the kitchen. It is also noteworthy that kitchen dishcloths and hand towels are frequently used multiple times for more than one use (e.g., hand drying and cleaning/removing excess moisture from the dishes at the same time). It is preferable to replace hand drying in the kitchen with drying using only paper towels. Moreover, inadequate hygiene conditions and poor temperature control in domestic refrigerators have been strongly associated with the presence of L. monocytogenes and other bacterial pathogens in consumer households [44,64,66,170]. To this end, proper cleaning and the use of a thermometer in the fridge are highly recommended.

The repeatedly observed unsafe consumer practices of washing raw poultry in the kitchen sink, using sponges for wiping spills on the kitchen countertop, placing raw foods above RTE products in the refrigerator, and storing foods at improper temperatures [32,35,37,41,131,147,170] are often encountered in the home kitchen setting and should be avoided at all costs. Besides that, the detection of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in household environments adds urgency to efforts aimed at improving food hygiene at the consumer level, as domestic kitchens may contribute to the dissemination and the horizontal transfer of ARG in bacteria [47,48,49].

Conclusively, as it was evidenced from all the above, domestic kitchens represent a major front line in the prevention of foodborne diseases. The domestic environment has been recognized as an overlooked but critical component of the food safety chain. Findings from this review suggest opportunities for intervention through consumer-oriented hygiene measures. The presence of bacterial pathogens on kitchen surfaces, utensils, and equipment, in addition to risky behaviors by the food consumers, indicates the need for consumer awareness and adoption of safe practices, including targeted hygiene interventions, consumer education, and improved household equipment design [137,145,166,167,169].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.D.A.; methodology, A.M. and N.D.A.; formal analysis, A.M.; investigation, A.M., R.A., Z.-E.C. and N.D.A.; resources, N.D.A.; data curation, A.M. and N.D.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M., R.A., Z.-E.C. and N.D.A.; writing—review and editing, A.M., O.M. and N.D.A.; visualization, A.M. and N.D.A.; supervision, N.D.A.; project administration, A.M., O.M. and N.D.A.; funding acquisition, N.D.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Newell, D.G.; Koopmans, M.; Verhoef, L.; Duizer, E.; Aidara-Kane, A.; Sprong, H.; Opsteegh, M.; Langelaar, M.; Threfall, J.; Scheutz, F.; et al. Food-borne diseases—The challenges of 20 years ago still persist while new ones continue to emerge. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 139, S3–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odeyemi, O. Public health implications of microbial food safety and foodborne diseases in developing countries. Food Nutr. Res. 2016, 60, 29819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO/FERG (World Health Organization/Foodborne Disease Burden Epidemiology Reference Group). WHO Estimates of the Global Burden of Foodborne Diseases; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 1–254. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/199350/9789241565165_eng.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- WHO/FERG (World Health Organization/Foodborne Disease Burden Epidemiology Reference Group). WHO Foodborne Disease Burden Epidemiology Reference Group for 2021–2024: Second Meeting Report, 19 October–2 November 2021; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–23. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/379327/9789240100510-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Scallan, E.; Hoekstra, R.M.; Angulo, F.J.; Tauxe, R.V.; Widdowson, M.-A.; Roy, S.L.; Jones, J.L.; Griffin, P.M. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—Major pathogens. Emerg. Inf. Dis. 2011, 17, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scallan Walter, E.J.; Cui, Z.; Tierney, R.; Griffin, P.M.; Hoekstra, R.M.; Payne, D.C.; Rose, E.B.; Devine, C.; Namwase, A.S.; Mirza, S.A.; et al. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—Major pathogens, 2019. Emerg. Inf. Dis. 2025, 31, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DG SANTE (Directorate General for Health and Food Safety). 2024 Annual Report Alert & Cooperation Network; European Union: Luxembourg, 2025; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority); ECDC (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control). The European Union One Health 2023 zoonoses report. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e9106. [Google Scholar]

- Data Sheet on Foodborne Biological Hazards: “Domestic Hygiene”. Available online: https://www.anses.fr/en/content/data-sheet-foodborne-biological-hazards-domestic-hygiene (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations); WHO (World Health Organization). General Principles of Food Hygiene; Codex Alimentarius Code of Practice, No. CXC 1-1969; FAO: Rome, Italy; WHO: Rome, Italy, 2023; pp. 1–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations); WHO (World Health Organization). Food Hygiene (Basic Texts), 4th ed.; FAO: Rome, Italy; WHO: Rome, Italy, 2009; pp. 1–125. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/a1552e/a1552e00.htm (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Jones, M.V. Application of HACCP to identify hygiene risks in the home. Int. Biodeter. Biodegrad. 1998, 41, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beumer, R.R.; Kusumaningrum, H. Kitchen hygiene in daily life. Int. Biodeter. Bidegrad. 2003, 51, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd-Bredbenner, C.; Berning, J.; Martin-Biggers, J.; Quick, V. Food safety in home kitchens: A synthesis of the literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 4060–4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taché, J.; Carpentier, B. Hygiene in the home kitchen: Changes in behaviour and impact of key microbiological hazard control measures. Food Control 2014, 14, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrusso, P.A.; Quinlan, J.J. Prevalence of pathogens and indicator organisms in home kitchens and correlation with unsafe food handling practices and conditions. J. Food Prot. 2017, 80, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, M.J.; Ferreira, V.; Truninger, M.; Maia, R.; Teixeira, P. Cross-contamination events of Campylobacter spp. in domestic kitchens associated with consumer handling practices of raw poultry. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 338, 108984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, R.; Bloomfield, S.; Adley, C.C. A study of cross-contamination of food-borne pathogens in the domestic kitchen in the Republic of Ireland. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2002, 76, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agata, N.; Ohta, M.; Yokoyama, K. Production of Bacillus cereus emetic toxin (cereulide) in various foods. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2002, 73, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirhonen, T.I.; Andersson, M.A.; Jääskeläinen, E.L.; Salkinoja-Salonen, M.S.; Honkanen-Buzalski, T.; Johansson, T.M.L. Biochemical and toxic diversity of Bacillus cereus in a pasta and meat dish associated with a food-poisoning case. Food Microbiol. 2005, 22, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirkell, C.E.; Sloan-Gardner, T.S.; Kacmarek, M.C.; Polkinghorne, B. An outbreak of Bacillus cereus toxin-mediated emetic and diarrhoeal syndromes at a restaurant in Canberra, Australia 2018. Commun. Dis. Intell. 2019, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Yu, P.; Wang, J.; Li, C.; Guo, H.; Liu, C.; Kong, L.; Yu, L.; Wu, S.; Lei, T.; et al. A study on prevalence and characterization of Bacillus cereus in ready-to-eat foods in China. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.-W. A foodborne outbreak of gastroenteritis caused by Vibrio parahaemolyticus associated with cross-contamination from squid in Korea. Epidemiol. Health 2019, 40, e2018056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcolm, T.T.H.; Chang, W.S.; Loo, Y.Y.; Cheah, Y.K.; Radzi, C.W.J.W.M.; Kantilal, H.K.; Nishibuchi, M.; Son, R. Simulation of improper food hygiene practices: A quantitative assessment of Vibrio parahaemolyticus distribution. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 284, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, I.; Albano, H.; Silva, J.; Teixeira, P. Food safety in the domestic environment. Food Control 2014, 37, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, E.; Morales-Rueda, A.; García-Gimeno, R.M. Cross-contamination and recontamination by Salmonella in foods: A review. Food Res. Int. 2012, 45, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, R.R.; Fierer, N.; Henley, J.B.; Leff, J.W.; Menninger, H.L. Home life: Factors structuring the bacterial diversity found within and between homes. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.; Bateman, A.C.; Bik, H.M.; Meadow, J.F. Microbiota of the indoor environment: A meta-analysis. Microbiome 2015, 3, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, G.E.; Bates, S.T.; Caporaso, J.G.; Lauber, C.L.; Leff, J.W.; Knight, R.; Fierer, N. Diversity, distribution and sources of bacteria in residential kitchens. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 15, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmielewski, R.A.N.; Frank, J.F. Biofilm formation and control in food processing facilities. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2003, 2, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaouris, E.; Heir, E.; Hébraud, M.; Chorianopoulos, N.; Langsrud, S.; Møretrø, T.; Habimana, O.; Desvaux, M.; Renier, S.; Nychas, G.-J. Attachment and biofilm formation by foodborne bacteria in meat processing environments: Causes, implications, role of bacterial interactions and control by alternative novel methods. Meat Sci. 2014, 97, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andritsos, N.D.; Stasinou, V.; Tserolas, D.; Giaouris, E. Temperature distribution and hygienic status of domestic refrigerators in Lemnos island, Greece. Food Control 2021, 127, 108121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumaningrum, H.D.; van Putten, M.M.; Rombouts, F.M.; Beumer, R.R. Effects of antibacterial dishwashing liquid on foodborne pathogens and competitive microorganisms in kitchen sponges. J. Food Prot. 2002, 65, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattick, K.; Durham, K.; Domingue, G.; Jørgensen, F.; Sen, M.; Schaffner, D.W.; Humphrey, T. The survival of foodborne pathogens during domestic washing-up and subsequent transfer onto washing-up sponges, kitchen surfaces and food. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2003, 85, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, E.W.; Redmond, E.C. Behavioral observation and microbiological analysis of older adult consumers’ cross-contamination practices in a model domestic kitchen. J. Food Prot. 2018, 81, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sakkaf, A. Domestic food preparation practices: A review of the reasons for poor home hygiene practices. Health Promot. Int. 2015, 30, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmond, E.C.; Griffith, C.J. Consumer food handling in the home: A review of food safety studies. J. Food Prot. 2003, 66, 130–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møretrø, T.; Martens, L.; Teixeira, P.; Ferreira, V.B.; Maia, R.; Maugesten, T.; Langsrud, S. Is visual motivation for cleaning surfaces in the kitchen consistent with a hygienically clean environment? Food Control 2020, 111, 107077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, A.C.; Austin, E. The kitchen dishcloth as a source of and vehicle for foodborne pathogens in a domestic setting. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2000, 10, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumaningrum, H.D.; Riboldi, G.; Hazeleger, W.C.; Beumer, R.R. Survival of foodborne pathogens on stainless steel surfaces and cross-contamination to foods. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2003, 85, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møretrø, T.; Moen, B.; Almli, V.L.; Teixeira, P.; Ferreira, V.B.; Asli, A.W.; Nilsen, C.; Langsrud, S. Dishwashing sponges and brushes: Consumer practices and bacterial growth and survival. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 337, 108928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, V.; Garćia-Jalón, I.; Vitas, A.I. Temperature distribution in Spanish domestic refrigerators and its effect on Listeria monocytogenes growth in sliced ready-to-eat ham. Food Control 2010, 21, 896–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, V.; Blair, I.S.; McDowell, D.A.; Kennedy, J.; Bolton, D.J. The incidence of significant foodborne pathogens in domestic refrigerators. Food Control 2007, 18, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccato, A.; Uyttendaele, M.; Membré, J.-M. Analysis of domestic refrigerator temperatures and home storage time distributions for shelf-life studies and food safety risk assessment. Food Res. Int. 2017, 96, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, M.D.; Barker, G.C.; Goodburn, K.E.; Peck, M.W. Risk presented to minimally processed chilled foods by psychrotrophic Bacillus cereus. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 93, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.W.; Hong, Y.J.; Jo, J.I.; Ha, S.D.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, H.J.; Rhee, M.S. Raw ready-to-eat seafood safety: Microbiological quality of the various seafood species available in fishery, hyper and online markets. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, E.; Lee, D.; Jang, S.; An, H.; Kim, M.; Kim, K.; Lee, K.; Ha, N. Antibiotic resistance and assessment of food-borne pathogenic bacteria in frozen foods. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2009, 32, 1749–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Xu, F.; Guo, H.; Cui, L. Domestic refrigerators: An overlooked breeding ground of antibiotic resistance genes and pathogens. Environ. Int. 2022, 170, 107647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, B.M.; Robleto, E.; Dumont, T.; Levy, S.B. The frequency of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in homes differing in their use of surface antibacterial agents. Curr. Microbiol. 2012, 65, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniça, M.; Manageiro, V.; Abriouel, H.; Moran-Gilad, J.; Franz, C.M.A.P. Antibiotic resistance in foodborne bacteria. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 84, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillard, J.-Y.; Bloomfield, S.F.; Courvalin, P.; Essack, S.Y.; Gandra, S.; Gerba, C.P.; Rubino, J.R.; Scott, E.A. Reducing antibiotic prescribing and addressing the global problem of antibiotic resistance by targeted hygiene in the home and everyday life settings: A position paper. Am. J. Infect. Control 2020, 48, 1090–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrusso, P.; Quinlan, J.J. Development and piloting of a food safety audit tool for the domestic environment. Foods 2013, 2, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, E.W.; Redmond, E.C. Domestic kitchen microbiological contamination and self-reported food hygiene practices of older adult consumers. J. Food Prot. 2019, 82, 1326–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ropkins, K.; Beck, A.J. HACCP in the home: A framework for improving awareness of hygiene and safe food handling with respect to chemical risk. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2000, 11, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langsrud, S.; Sørheim, O.; Skuland, S.E.; Almli, V.L.; Jensen, M.R.; Grøvlen, M.S.; Ueland, Ø.; Møretrø, T. Cooking chicken at home: Common or recommended approaches to judge doneness may not assure sufficient inactivation of pathogens. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moen, B.; Langsrud, S.; Berget, I.; Maugesten, T.; Møretrø, T. Mapping the kitchen microbiota in five European counties reveals a set of core bacteria across countries, kitchen surfaces, and cleaning utensils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e0026723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Boer, A.; Hahné, M. Cross-contamination with Campylobacter jejuni and Salmonella spp. from raw chicken products during food preparation. J. Food Prot. 1990, 53, 1067–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Ferreira, N.; Alves, A.; Cardoso, M.J.; Langsrud, S.; Malheiro, A.R.; Fernandes, R.; Maia, R.; Truninger, M.; Junqueira, L.; Nicolau, A.I.; et al. Cross-contamination of lettuce with Campylobacter spp. via cooking salt during handling raw poultry. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Didier, P.; Nguyen-The, C.; Martens, L.; Foden, M.; Dumitrascu, L.; Mihalache, A.O.; Nicolau, A.I.; Skuland, S.E.; Truninger, M.; Junqueira, L.; et al. Washing hands and risk of cross-contamination during chicken preparation among domestic practitioners in five European countries. Food Control 2021, 127, 108062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedeen, N.; Smith, K. Restaurant practices for cooling food in Minessota: An interventional study. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2020, 17, 758–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalinowski, R.M.; Tompkin, R.B.; Bodnaruk, P.W.; Payton Pruett, W., Jr. Impact of cooking, cooling, and subsequent refrigeration on the growth and survival of Clostridium perfringens in cooked meat and poultry products. J. Food Prot. 2003, 66, 1227–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sayeed, S.; McClane, B.A. Prevalence of enterotoxigenic Clostridium perfringens isolates in Pittsburgh (Pennsylvania) area soils and home kitchens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 7218–7224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Rosas, J.; Cerna-Cortés, J.F.; Méndez-Reyes, E.; Lopez-Hernandez, D.; Gómez-Aldapa, C.; Estrada-Garcia, T. Presence of faecal coliforms, Escherichia coli and diarrheagenic E. coli pathotypes in ready-to-eat salads, from an area where crops are irrigated with untreated sewage water. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 156, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, I.; Regalo, M.; Mena, C.; Almeida, G.; Carneiro, L.; Teixeira, P.; Hogg, T.; Gibbs, P.A. Incidence of Listeria spp. in domestic refrigerators in Portugal. Food Control 2005, 16, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T.C.; Acuff, G.R.; Lucia, L.M.; Prasai, R.K.; Benner, R.A.; Terry, C.T. Survey of residential refrigerators for the presence of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Food Prot. 1993, 56, 874–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitraşcu, L.; Nicolau, A.I.; Neagu, C.; Didier, P.; Maître, I.; Nguyen-The, C.; Skuland, S.E.; Møretrø, T.; Langsrud, S.; Truninger, M.; et al. Time-temperature profiles and Listeria monocytogenes presence in refrigerators from households with vulnerable consumers. Food Control 2020, 111, 107078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergelidis, D.; Abrahim, A.; Sarimvei, A.; Panoulis, C.; Karaioannoglou, P.; Genigeorgis, C. Temperature distribution and prevalence of Listeria spp. in domestic, retail and industrial refrigerators in Greece. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1997, 34, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A.; Villarruel-López, A.; Navarro-Hidalgo, V.; Martínez-González, N.E.; Torres-Vitela, M.R. Salmonella and Shigella in freshly squeezed orang juice, fresh oranges, and wiping cloths collected from public markets and street booths in Guadalajara, Mexico: Incidence and comparison of analytical routes. J. Food Prot. 2006, 69, 2595–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janjic, J.; Ivanovic, J.; Glamoclija, N.; Boskovic, M.; Baltic, T.; Glisic, M.; Baltic, M.Z. The presence of Salmonella spp. in Belgrade domestic refrigerators. Procedia Food Sci. 2015, 5, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanassova, V.; Meindl, A.; Ring, C. Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus and staphylococcal enterotoxins in raw pork and uncooked smoked ham–a comparison of classical culturing detection and RFLP-PCR. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2001, 68, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smyth, D.S.; Kennedy, J.; Twohig, J.; Miajlović, H.; Bolton, D.; Smyth, C.J. Staphylococcus aureus isolates from Irish domestic refrigerators possess novel enterotoxin end enterotoxin-like genes and are clonal in nature. J. Food Prot. 2006, 69, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, R.D.; Pradella, F.; Turatti, M.A.; Amaro, E.C.; da Silva, A.R.; Farias, A.S.; Pereira, J.L.; Khaneghah, A.M. Evaluation of Staphylococcus spp. in food and kitchen premises of Campinas, Brazil. Food Control 2018, 84, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millman, C.; Rigby, D.; Edward-Jones, G.; Lighton, L.; Jones, D. Perceptions, behaviours and kitchen hygiene of people who have and have not suffered campylobacteriosis: A case control study. Food Control 2014, 41, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufrenne, J.; Ritmeester, W.; Delfgou-van Asch, E.; van Leusden, F.; de Jonge, R. Quantification of the contamination of chicken and chicken products in the Netherlands with Salmonella and Campylobacter. J. Food Prot. 2001, 64, 538–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Gibney, S.; Nolan, A.; O’Brien, S.; McMahon, M.A.S.; McDowell, D.; Fanning, S.; Wall, P.G. Identification of critical points during domestic food preparation: An observational study. Br. Food J. 2011, 113, 766–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittry, B.C.; Holst, M.M.; Anderberg, J.; Hedeen, N. Operational antecedents associated with Clostridium perfringens outbreaks in retail food establishments, United States, 2015–2018. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2022, 19, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taormina, P.J.; Dorsa, W.J. Growth potential of Clostridium perfringens during cooling of cooked meats. J. Food Prot. 2004, 67, 1537–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornillot, E.; Saint-Joanis, B.; Daube, G.; Katayama, S.-I.; Granum, P.E.; Canard, B.; Cole, S.T. The enterotoxin gene (cpe) of Clostridium perfringens can be chromosomal or plasmid-borne. Mol. Microbiol. 1995, 15, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, K.; Wen, Q.; McClane, B.A. Multiplex PCR genotyping assay that distinguishes between isolates of Clostridium perfringens Type A carrying a chromosomal enterotoxin gene (cpe) locus, a plasmid cpe locus with an IS1470-like sequence, or a plasmid cpe locus with an IS1151 sequence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 1552–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. coli Infection. Available online: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/16638-e-coli-infection (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Bolívar, A.; Saiz-Abajo, M.J.; García-Gimeno, R.M.; Petri-Ortega, E.; Díez-Leturia, M.; González, D.; Vitas, A.I.; Pérez-Rodríguez, F. Cross-contamination of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in fresh-cut leafy vegetables: Derivation of a food safety objective and other risk management metrics. Food Control 2023, 147, 109599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuan, C.H.; Lim, L.W.K.; Ting, T.W.; Rukayadi, Y.; Ahmad, S.H.; Radzi, C.W.J.W.M.; Thung, T.Y.; Ramzi, O.B.; Chang, W.S.; Loo, Y.Y.; et al. Simulation of decontamination and transmission of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella Enteritidis, and Listeria monocytogenes during handling of raw vegetables in domestic kitchens. Food Control 2017, 80, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavatte, N.; Baré, J.; Lambrecht, E.; Van Damme, I.; Vaerewijck, M.; Sabbe, K.; Houf, K. Co-occurrence of free-living protozoa and foodborne pathogens on dishcloths: Implications for food safety. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 191, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A. Isolation of Salmonella from liquid whole eggs sold in retail outlets in Egypt, Bangladesh and not in Japan. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2014, 2, 390–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez, M.L.F.; Burgos, M.J.G.; Pulido, R.P.; Gálvez, A.; López, R.L. Correlations among resistances to different antimicrobial compounds in Salmonella strains from hen eggshells. J. Food Prot. 2018, 81, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bremer, V.; Bocter, N.; Rehmet, S.; Klein, G.; Breuer, T.; Ammon, A. Consumption, knowledge, and handling of raw meat: A representative cross-sectional survey in Germany, March 2001. J. Food Prot. 2005, 68, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luber, P. Cross-contamination versus undercooking of poultry meat or eggs—Which risks need to be managed first? Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 134, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, M.; Sakagami, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Inoue, R.; Jojima, T. Analysis of the relationship of microbial contamination with temperature and cleaning frequency and method of domestic refrigerators in Japan. J. Food Prot. 2020, 83, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamas, A.; Regal, P.; Vázquez, B.; Miranda, J.M.; Cepeda, A.; Franco, C.M. Salmonella and Campylobacter biofilm formation: A comparative assessment from farm to fork. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 4014–4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macías-Rodríguez, M.E.; Navarro-Hidalgo, V.; Linares-Morales, J.R.; Olea-Rodríguez, M.A.; Villaruel-López, A.; Castro-Rosas, J.; Gómez-Aldapa, C.A.; Torres-Vitela, M.R. Microbiological safety of domestic refrigerators and the dishcloths used to clean them in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico. J. Food Prot. 2013, 76, 984–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, E.; Duty, S.; Callahan, M. A pilot study to isolate Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus from environmental surfaces in the home. Am. J. Infect. Control 2008, 36, 458–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, E.C.D.; Greig, J.D.; Bartleson, C.A.; Michaels, B.S. Outbreaks where food workers have been implicated in the spread of foodborne disease. Part 3. Factors contributing to outbreaks and description of outbreak categories. J. Food Prot. 2007, 70, 2199–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czarnecka, C.; Jensen, M.R.; Astorga, A.; Zaród, M.; Stępień, K.; Gewartowska, M.; Møretrø, T.; Sabała, I.; Heir, E.; Jagielska, E. Staphylococcus spp. eradication from surfaces by the engineered bacteriolytic enzymes. Food Control 2025, 167, 110795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Liang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Li, B.; Li, L.; Chen, D.; Xu, Z. Formation and development of Staphylococcus biofilm: With focus on food safety. J. Food Saf. 2017, 37, e12358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, L.J.; Kleiss, T.; Cordier, J.L.; Cordellana, C.; Konkel, P.; Pedrazzini, C.; Beumer, R.; Siebenga, A. Listeria spp. in food processing, non-food and domestic environments. Food Microbiol. 1989, 6, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.; Wiedmann, M.; Teixeira, P.; Stasiewicz, M.J. Listeria monocytogenes persistence in food-associated environments: Epidemiology, strain characteristics, and implications for public health. J. Food Prot. 2014, 77, 150–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lianou, A.; Sofos, J.N. A review of the incidence and transmission of Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat products in retail and food service environments. J. Food Prot. 2007, 70, 2172–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci, A.; Allende, A.; Bolton, D.; Chemaly, M.; Davies, R.; Escámez, P.S.F.; Girones, R.; Herman, L.; Koutsoumanis, K.; Nørrung, B.; et al. Listeria monocytogenes contamination of ready-to-eat foods and the risk for human health in the EU. EFSA J. 2018, 16, e05134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, E.W.; Redmond, E.C. Analysis of older adults’ domestic kitchen storage practices in the United Kingdom: Identification of risk factors associated with listeriosis. J. Food Prot. 2015, 78, 738–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaivalappil, A.; Young, I.; Paco, C.; Jeyapalan, A.; Papadopoulos, A. Food safety and the older consumer: A systematic review and meta-regression of their knowledge and practices at home. Food Control 2020, 107, 106782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessim, A.I.; Fakhry, S.S.; Alwash, S.J. Detection and determination of Bacillus cereus in cooked rice and some types of spices with ribosomal 16SrRNA gene selected from Iraqi public restaurants. Int. J. Bio-Resour. Stress Manag. 2017, 8, 382–387. Available online: https://ojs.pphouse.org/index.php/IJBSM/article/view/1122 (accessed on 23 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Navaneethan, Y.; Effarizah, M.E. Prevalence, toxigenic profiles, multidrug resistance, and biofilm formation of Bacillus cereus isolated from ready-to-eat cooked rice in Penang, Malaysia. Food Control 2021, 121, 107553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]