Abstract

Period poverty refers to the lack of access to or affordability of menstrual hygiene supplies such as sanitary products and the inaccessibility of washing facilities, waste disposal and educational materials. Period poverty can significantly affect menstruating individuals’ physical, mental, and reproductive health and emotional wellbeing; negatively impact educational outcomes; cause financial strain; result in absenteeism from work and school; create barriers to healthcare access; and perpetuate poor health outcomes for generations. Barriers to menstrual equity include lack of access to period support, cost, poor sanitary facilities, lack of education, social and cultural stigma, and legal restrictions. Therefore, it is crucial to actively advocate for initiatives to increase access to menstrual hygiene products, raise public awareness, and educate individuals on safe menstrual practices. Approximately 500 million girls and women worldwide and an estimated 16.9 million people in the United States experience period poverty, with the issue being particularly common among marginalized groups such as Black or Hispanic menstruating individuals and those who are homeless, living in poverty, of low income, or attending college. This article investigates the physical, psychological, educational and social impacts of inequitable access to menstrual products, menstrual education, and sanitation facilities among menstruating individuals who are Black, Hispanic or of low income within the United States. We examine the threat this poses to health equity and propose recommendations to address this pervasive issue.

1. Introduction

Menstruation as defined by the National Library of Medicine is a natural biological process where the inner lining of the uterus, known as the endometrium, is shed through the vagina; this typically occurs on a monthly basis amongst people of reproductive age who were assigned female at birth [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) insists that menstruation be treated as a broader matter of health and human rights instead of merely being treated as a hygiene issue [2]. This therefore includes ensuring that there is access to adequate and accurate information on menstruation, menstrual products and clean sanitation for cleanup and disposal during menstruation.

The American Medical Women’s Association defines period poverty as the lack of accessibility or affordability of menstrual hygiene tools and educational material, such as sanitary products, washing facilities, and waste management [3]. The lack of access to resources such as vital education, essential menstrual hygiene products, and adequate sanitation during menstruation by those affected is encompassed by the term “period poverty” [4,5]. This can significantly affect the physical, mental and reproductive health, emotional wellbeing and educational outcomes of those afflicted by period poverty [6,7,8]. There are also environmental impacts of menstrual supplies that implore the need to develop sustainable, cost-effective menstrual products within the United States [4,9]. It is therefore essential to promote programs that aim to expand access to menstrual hygiene products, raise awareness, and educate people about safe menstrual practices among menstruating individuals who are Black, Hispanic or of low income within the United States. Expanded access can help ensure that menstrual products are affordable, available, accessible, and acceptable.

Since many low-income individuals who menstruate may not have easy access to products, period poverty disproportionately affects menstruating individuals of low income in the United States [10,11,12,13,14,15]. Moreover, structural factors such as health care access and healthy food availability can fuel reproductive health disparities that disproportionately affect persons racialized as Black or Hispanic and interfere with menstrual health [16]. Period poverty in the U.S. disproportionately affects members of racial and ethnic minoritized communities, and Black or Hispanic menstruating individuals are more likely to experience this burden [11,17,18,19].

Persons racialized as Black or Hispanic and individuals living in low-income communities often miss school, feel ashamed, and face social stigma because of the existing gap in access menstrual hygiene care, all of which only reinforce the deeper patterns of gender inequality and poverty that exist within the United States. To make matters worse, essential menstrual products are not typically covered by public assistance programs such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program, making them unaffordable for many low-income individuals [17].

Worldwide, nearly 500 million menstruating individuals experience period poverty [18]. In the United States, it is estimated that around 16.9 million people experience period poverty, with the issue especially prevalent among marginalized groups, including those living in poverty, experiencing homelessness, or attending college [19]. Research shows that nearly two-thirds of menstruating individuals from low-income backgrounds have struggled to afford menstrual products, sometimes even being forced to choose between buying these necessities versus food. Menstrual products are expensive in the United States as shown by a national survey of 1000 menstruating teens; results indicated that 1 in 5 struggled to afford period products and 4 in 5 either were or knew someone who missed class time because they did not have access to period products [10].

It is alarming to note that one in four teenage girls in the U.S have reported missing school due to lack of menstrual supplies [20]. Despite growing awareness, the absence of a cohesive national policy highlights the existence of persistent gender disparities in both health care and educational policies.

The growing widespread effects of period poverty among menstruating individuals who are Black, Hispanic or of low income within the United States, ranging from reduced academic performance to diminished physical and mental health of persons affected; this makes it a concerning public health and social justice issue. Combating it will require a combination of legislative reforms, increased funding, and widespread education. Ultimately, addressing period poverty is not only about hygiene, but also about ensuring dignity, equality, and opportunity for all who menstruate. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic compounded the issue of period poverty due to increased unemployment, job losses and fiscal barriers to accessing needed menstrual products, with Black and Hispanic menstruators particularly affected [21].

This paper investigates the physical, psychological, educational and social impacts of inequitable access to menstrual products, education, and sanitation facilities and the threat this poses to health equity. This paper also proposes recommendations to address this pervasive issue.

2. Impact of Period Poverty

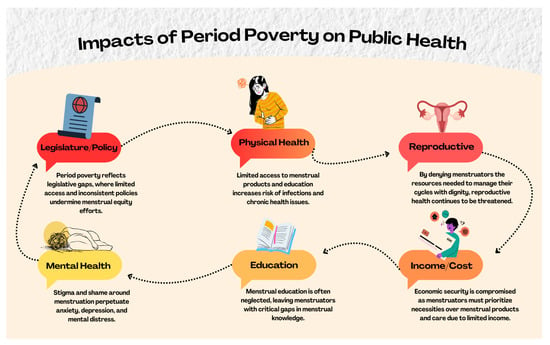

Period poverty is a multifaceted challenge faced by menstruating individuals who are Black, Hispanic, or from low-income communities, and it significantly influences multiple areas of daily life. Its effects extend beyond the inability to afford menstrual products, impacting physical health, school attendance and academic performance, emotional and mental wellbeing, participation in social and community activities, and overall economic stability (Figure 1). As these burdens accumulate, they deepen existing inequalities and create long-term barriers to health and opportunity.

Figure 1.

Impacts of period poverty on public health.

2.1. Physical Health

The lack of access to safe, hygienic menstrual products forces many menstruators—especially those who are Black, Hispanic, homeless, incarcerated, or low-income—to resort to using unsafe alternatives like unclean cloth, paper, or even coconut husks [22]. These practices increase the risk of various health complications, such as:

Urogenital Infections: Using unsanitary or reused menstrual materials for extended periods can increase the risk of infections such as urinary tract infections (UTIs), bacterial vaginosis, and other reproductive health issues [23]. Studies have shown that women who use disposable pads are less likely to experience these infections than those who rely on reusable pads without adequate cleaning and hygiene practices [24].

Skin Irritation and Vaginal Health Issues: A significant number of women experience vaginal itching, irritation, and unusual discharge because of using unsuitable or overly worn menstrual products [25].

Maternal Health Risks: It has been reported that in extreme situations, some women intentionally become pregnant to escape the challenges of menstruation, which can lead to serious maternal health risks caused by inadequate spacing between pregnancies [26].

Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS) and Other Chronic Conditions: The use of menstrual products or wearing them longer than advised can result in severe and potentially life-threatening conditions like toxic shock syndrome (TSS) and may also increase the risk of developing reproductive health issues such as endometriosis and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) [6].

These various health challenges caused by period poverty may lead to reproductive disorders that affect a person’s ability to conceive or give birth safely [27].

2.2. Education Disruptions and Academic Inequities

Lack of education significantly worsens period poverty by limiting knowledge about menstrual health, proper hygiene practices, and available resources. Many students, especially in under-resourced schools, feel embarrassed or ashamed due to stigma, and they lack accurate information about menstruation [28]. Period poverty impacted roughly one in four American high school students in 2021, with Black, Brown, and low-income adolescents experiencing the greatest impact [29]. This leads to poor menstrual hygiene management, increased school absenteeism, poor grade, school dropout or a lack of interest in school, a low-level job, low status and negative emotional experiences [30]. A report from UNESCO supports this finding, noting that one out of every ten menstruating adolescents misses school during their cycle due to limited access to necessary menstrual supplies and support [6]. As these interruptions continue, they gradually create deficits in learning, diminish academic success, and limit involvement in extracurricular programs. Without adequate education, harmful myths and taboos persist, contributing to shame, isolation, and long-term impacts on girls’ health, confidence, and educational opportunities, causing declines in academic success and negatively impacting their prospects for good employment after graduation [27].

2.3. Mental Health

The mental health effects of period poverty are serious and far-reaching. Stigma and shame around menstruation often prevent open conversation, leaving menstruators without support [28]. The lack of access to hygiene products can lead to anxiety, depression, and social withdrawal [8]. Fear of leaks or embarrassment causes many to miss school or work, lowering self-esteem. In extreme cases, especially among incarcerated or displaced individuals, the need for menstrual products may lead to exploitation, further harming mental wellbeing and dignity [22]. In U.S. Black, Hispanic, and low-income communities, menstrual stigma and poor access to hygienic products and private, sanitary facilities often lead to stress, isolation, depression, and anxiety, making it harder to manage menstruation safely. Data from the 2018 American College Health Assessment show that 63% of college students struggled with overwhelming anxiety, while 12.7% had serious thoughts of suicide in the same year [31].

2.4. Social Wellbeing

Period poverty profoundly affects social wellbeing. It often results in feelings of shame and isolation, contributing to mental health issues like anxiety and depression [6]. This can cause individuals to miss school or work and reduce their involvement in social activities. Harmful myths about menstruation persist—such as the belief that tampons affect virginity or that menstruating people spoil food—and stigma remains widespread, with 58% of menstruating individuals in the U.S. feeling ashamed of their periods and 51% of men thinking periods should not be discussed at work [6].

2.5. Economic

Economic instability greatly contributes to period poverty, as the high cost of menstrual products strains limited household budgets, especially in low- and middle-income communities. Many menstruating individuals resort to using unsafe alternatives like unclean rags, leading to health problems. The tampon tax drives up the cost of menstrual supplies and disproportionately affects women who cannot easily afford them, with U.S. studies confirming that this tax intensifies period poverty and negatively impacts quality of life (Singh et al., 2020) [32]. This financial burden often forces individuals to sacrifice other essentials like food or education, worsening the cycle of poverty [28].

3. Health Equity

Menstrual equity is the notion that everyone who experiences menstruation should have access to menstrual products that are safe, reasonably priced, and easily available, as well as education and safe environments like bathroom facilities and clean water to help them manage their periods and attend school, work, and engage in life with dignity [33]. It also refers to the efforts to combat the stigma that surrounds menstruation. It covers the social and cultural background of menstruation as well as the practical aspects of managing menstrual hygiene. Key elements of menstrual equity include accessibility and affordability, education and awareness, safe and supportive environments, addressing period poverty or unmet menstrual hygiene needs among menstruating individuals [20], and challenging stigma, myths and misconceptions surrounding menstruation [33].

Moreover, menstrual equity is important because it is a major public health issue and a fundamental human right [34]. Lack of access to menstrual products and safe environments can adversely impact physical and mental health, overall wellbeing, education and employment and is directly related to human dignity. Menstrual equity is a neglected public health issue because reduced product access for a natural biological process can lead to economic hardship, missed school, misinformation, physical and mental health problems, social discrimination and exclusion [35]. Only recently has period poverty gained more attention for its public health, social and economic impacts [36]. Moreover, the intersectional experience of racism and sexism is illustrated in menstrual health where disproportionate access to healthy foods and healthcare has contributed to racial disparities in reproductive outcomes [16,37]. Research shows that people who menstruate racialized as Black and Latinx have earlier menarche [38,39,40]. One hypothesized theory for the observed racial disparities in age of menarche is discrimination faced by Black women in the USA [41]. People who menstruate racialized as LatinX also have longer and more varied cycle lengths compared to those racialized as white [42]. Difference in age at menstruation is associated with risk for chronic diseases and affect menstrual health over the life course [16].

4. Barriers to Menstrual Equity

4.1. Access

In shaping access to period support, factors such as income, disability, gender identity, and race not only inform how access is defined and experienced but also reflect the systemic inequities in the U.S. that impede progress towards menstrual equity. Income is a fortifying barrier to access as it contributes to the quality of menstrual health management.

Between 2023 and 2024, income trends in the U.S. revealed widening disparities across racial and gender lines. While Asian and Hispanic households saw median income gains of 5.1% and 5.5% respectively, Black households experienced a 3.3% decline. White individuals working full-time year-round saw a 2.7% increase in earnings, whereas earnings for Black and Asian full-time workers remained statistically unchanged. Gender disparities persisted as well: men’s median earnings rose to $71,090 with a 3.7% increase, while women’s earnings stagnated at $57,520 [43]. These disparities highlight the multifaceted effects of racial and gender-based income inequality, with Black women experiencing some of the most persistent economic disadvantages among U.S. demographic groups.

It is frequently noted that wealthier households are much more likely to have access to sanitary spaces compared to less affluent households, which are less likely to have access to water, soap, and private, secure spaces that provide dignity for menstruators [44,45]. As these limitations account for the millions of menstruating individuals by household, it overlooks the limitations faced by those without a home. Collections of studies have highlighted how people experiencing homelessness (PEHs) face struggles in managing menstruation through access to products, adequate sanitation spaces, and social stigma. Service providers for shelters even express a dire lack of products, dispensary medications, and care available for menstruators seeking assistance [12,46].

Given that such experiences occur among housed and unhoused menstruators, access also serves as an equity barrier among those with disabilities. Data from the CDC’s 2018 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) revealed that 17.4 million adults with disabilities reported frequent mental distress, with a prevalence rate (32.9%) more than four times higher than among adults without disabilities (7.2%). Those with both cognitive and mobility impairments reported the highest levels of distress (55.6%), and individuals facing additional health-related challenges. Furthermore, adults with disabilities living below the federal poverty line reported mental distress 70% more often than those in higher-income households [47].

A systematic review of conducted studies revealed that current approaches to menstrual health for people with disabilities reveal critical gaps in care and support. There is no consistent, evidence-based guidance available for caregivers, and menstrual education and resources tailored to individuals with intellectual disabilities remain limited. Researchers have also noted a lack of data on how people with intellectual impairments experience menstrual symptoms, making it difficult to design responsive interventions. Additionally, menstrual products are often expensive and rarely adapted to meet the physical needs of those with mobility challenges [48,49]. These shortcomings in professional standards and product design contribute to systematic barriers that undermine menstrual equity for disabled individuals.

While menstrual health initiatives often center on women and girls, they can unintentionally exclude individuals whose gender identities fall outside this binary, creating substantial barriers to access of menstrual support resources. As UNICEF partners with various countries, they have identified a lack of legal representation for those who are nonconforming and transgender. UNICEF notes that this group of menstruating individuals is less likely to gain access to education, services, and infrastructural spaces designed explicitly for menstrual hygiene [50].

4.2. Cost

The cost of menstrual products affects the ability of individuals managing their periods to do so affordably and effectively. In what produces financial strain, the cost of sanitary products creates an altitude of stress as menstruators face the dilemma of how to ration their income on necessities other than menstrual products. The estimated annual costs a menstruator pays, depending on their geographical location and menstrual flow, range from $70 to $120. Over a menstruator’s lifespan, this range can add up to more than $5000, excluding taxation on these products, which increases the total by a few hundred dollars [51].

Because of the high cost of sanitary products combined with economic instability, many menstruators resort to less expensive products that are neither hygienic nor adequate for menstrual management [52]. A 2019 study of low-income women aged 18 years old revealed that among 10 nonprofit organizations, 2/3 of these women were unable to afford products at some point during the year. The study highlighted the universal struggle menstruators experience when unable to afford products. Menstruating individuals who are unable to afford quality menstrual sanitary products often resort to less adequate substitutes, such as cloths, rags, and tissue paper [12].

4.3. Inadequate Sanitation Facilities

Rather than being a passive contributor to discomfort, inadequate sanitation functions as a structural barrier to dignified menstrual care. To maintain adequate menstrual hygiene, sanitation facilities must be properly suited for menstruators. Facilities lacking menstrual hygiene management resources often exhibit a recurring pattern in areas with poor infrastructure, resulting in inadequate sanitation. Infrastructural limitations imposed include the absence of doors, running water, toilets, and proper disposal [44,53].

This barrier is further evidenced by national disparities in household plumbing access. As of 2020, an estimated 2.2 million individuals in the U.S. lacked running water at home. A study by DigDeep and the US Water Alliance identified poverty as a key driver of this gap, with race emerging as the strongest predictor of whether a household has complete plumbing. Native American families were nineteen times more likely than white households to lack essential facilities such as hot and cold water, a sink, a shower, and a toilet, while Black and Latino households were nearly twice as likely [54]. These inequities directly obstruct safe, private menstrual care at home.

In schools, similar barriers persist. Research conducted across New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago found that Black and Latina students faced significant challenges managing menstruation due to poor bathroom design and maintenance. Participants described short stall doors, wide gaps that compromised privacy, inconsistent access to trash bins, and the absence of menstrual product dispensers [55]. These infrastructural flaws not only create a discomfort but also function as systemic barriers to menstrual equity in educational settings.

Furthermore, as these inadequate sanitation facilities do not address such absence, challenges such as attendance, academic performance, and privacy are amplified among adolescents in rural and urban communities, and those with disabilities [45].

4.4. Lack of Education

Serving as another primary barrier, lack of education on menstrual health contributes not only to misinformation but also to habitual social stigma. In what is currently the only continuous, open-access study tracking the impact that period poverty imposes on adolescents within the U.S., the State of the Period study has punctuated this very barrier through its latest findings from 2023. Where it is noted that adolescents express a desire for extensive menstrual health education in schools, “58% of teens agree the world is not set up for them to manage their periods with full confidence” [56] (p. 2). Considering this, healthcare systems play a critical role in advancing menstrual health education by shaping how menstruators access accurate information and support. However, this responsibility is often overlooked within academic settings, revealing a significant gap in institutional priorities.

In the history of menstrual education, it often took the form of commercial advertisements that sponsored and promoted sanitary products. The Kotex brand predominantly took this role, creating informational advertisements that more often glamorized their products and gave an underwhelming depiction of menstruation. A constant struggle for school nurses is the constraints on delivering menstrual and reproductive health curricula and care in schools. The National Association of School Nurses calculated that only 40% of all U.S. schools have a full-time nurse [55,57]. Such insufficiency highlights the shortcomings of learning about menstruation, as female students voice frustration that female reproductive curricula are not cohesive with menstruation [58]. Approximately 4 out of 5 (78%) students reported feeling that the biology of animals, such as frogs, is taught more frequently than the anatomy of the female body [56].

4.5. Societal/Cultural Stigma

Societal and cultural stigma surrounding menstruation poses a significant barrier to achieving equity as it suppresses discussions about periods and affects menstruators’ willingness to seek support. The State of the Period study highlights that both adolescents and adults in the U.S. feel shame and negative associations when discussing their periods [34].

Across various cultural and societal perspectives, menstruation is often viewed as sacred, impure, or dirty, leading to shame associated with the experience. In the religious context, these perceptions are often reinforced through doctrine, tradition, or a lack of explicit discussion. In what is one of the largest followed religions in the U.S., according to the 2024 PRRI Census of American Religion, two-thirds of Americans (65%) continue to affiliate with Christianity, among white, Black, and Hispanic people aged 18 and over [59]. While Christianity is the most widely practiced religion in the U.S., there is limited research on how its teachings directly influence menstrual stigma. As there is an incline of Religiously unaffiliated at 28%, the remaining 6% of Americans are affiliated with Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Unitarian Universalism, or other world religions [59]. These statistics offer a demographic snapshot of religious affiliation in the U.S., helping to contextualize how faith-based cultural norms intersect with other aspects of society. For Black and Brown communities, religious norms may compound existing barriers to menstrual support, especially when paired with generational silence.

Within Judaism, Islam, and Hinduism, three of the most widely practiced non-Christian religions in the U.S., certain menstrual-related customs may contribute to the isolation of menstruating individuals. For example, Orthodox Jewish traditions may restrict physical contact and ritual participation during menstruation. In Islam, menstruating individuals are often exempt from prayer and fasting, which can reinforce notions of impurity. Hindu practices in some communities may prohibit menstruating women from entering temples or the kitchen, further embedding exclusion into daily life. While these practices vary widely by denomination and cultural interpretation, they share a common thread: the positioning of menstruation as a condition requiring separation or silence [60,61,62].

Nonetheless, the isolation these beliefs curate is particularly pronounced among girls, as sharing the news of their first period often instills worry and fear about being treated differently or perceived as more mature by adults [28,36]. Consequently, seeking guidance becomes a source of secrecy and stress for many young menstruators at school, in their homes, and in public spaces. The culture of silence and stigma surrounding menstruation remains an under-researched barrier and addressing it requires attentiveness to enforce understanding enough to lead to meaningful policy reforms that support menstruating individuals.

4.6. Legislative Barriers

Current legislatures often neglect equity in discussions about product tax and public distribution, failing to address the more profound implications of menstrual health regulation. Widely recognized menstrual products, such as pads and tampons, receive institutional recognition. However, without comprehensive legislation rooted in menstrual health, these same products pose significant risks to menstruators when manufactured and marketed. Since there is no national sales tax in the United States, taxation of sanitary products is specified through individual state tax codes [51]. As of 15 May 2025, 18 out of the 50 states still charge sales tax on sanitary products. The range for these sales taxes varies from four to seven percent [63].

Furthermore, nearly two decades ago, the FDA developed a guidance document that is still commonly used to assist the industry in preparing pre-market 510(k) submissions. In Section 6 of this document, the FDA lists the identified risks to health arising from these products, which include adverse tissue reaction, vaginal injury, vaginal infection, and toxic shock syndrome [64]. This legislation, though an effort to promote clarity in requiring the disclosure of product risk to the public, also falls short by allowing the continued public distribution and sale of these items that compromise menstruators’ health and income.

Legislative efforts across regions often spotlight menstrual equity by mandating free product distribution in schools and public buildings, reflecting a commitment to combating period poverty [12,65]. However, the absence of critical components such as school protocols for menarche, adequate funding, and health literacy infrastructure reveals persistent structural oversights within the mandates [46,57]. In the US, schools may offer products but often lack the staffing, training, and inclusive policies needed to support students, as mandated by legislatures like Title IX, and neglectful of the word “menstruation” [57]. On a global scale, countries like Sierra Leone and Kenya promote access to education yet fail to establish menstrual-friendly environments or endorse menstrual equity as a given right, unlike Scotland, which has implemented the Free Provision Act of 2021 [27,36]. Such disparity in policy framing entails the misalignment between health equity goals and institutional realities [55]. These dualities illustrate how equity is both superficially addressed and fundamentally neglected within existing policy frameworks, as evidenced by legislatures aimed at tackling period poverty, an acknowledged public health issue that ultimately displaces deeper systemic barriers and jeopardizes initiatives to establish menstrual equity as a universal right.

5. Advocacy and Solutions/Recommendations

In addressing the issues of period poverty within the United States, a scientific, data-driven, and cross-sectional approach must be adopted. Efforts to increase advocacy around period poverty must primarily focus not only on improving access to menstrual products but must also address the systemic inequities that are endemic within the United States and that disproportionately affect menstruating individuals who are Black, Hispanic or of low-income endemic within the United States. Below are achievable potential solutions, that, if adopted, could help eradicate period poverty within the United States.

5.1. Policy Reforms and Governmental Action

Federal and State governments are well positioned to break down systemic barriers affecting this population from the past that inhibit access to menstrual hygiene products. One of such existing gaps is that menstrual hygiene products are still taxed as non-essential items in many states, commonly known as the “tampon tax.” In 2022, 21 of the 51 US states (including Washington D.C.) (41.1%) had taxation on menstrual products, ranging from 4.0% in Alabama, Georgia, and Wyoming to 7.0% in Indiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee [66].

To make matters worse, menstrual products are excluded from federal public assistance programs such as SNAP and WIC, making them inaccessible to millions of low-income menstruators. Amending these essential programs to include menstrual hygiene products would directly alleviate the economic burden for vulnerable populations [17]. The following policy recommendation if implemented would go a long way to reduce period poverty within this population in the United States. The first recommendation is to mandate free menstrual products in all public schools, shelters, and correctional facilities. A second approach is to immediately eliminate the draconian “tampon Tax” nationwide. Finally, there is a need to expedite the amendment of federal benefit programs to include menstrual hygiene products.

5.2. School Based Approach

The lack of access to menstrual products within schools contributes to absenteeism, stigma, and reduced academic performance. Research has shown that 1 in 4 teenage girls in the U.S. missed class due to inadequate access to menstrual supplies [67]. Therefore, making menstrual products freely and readily available in restrooms but not just through the nurse’s offices can normalize menstruation and remove potential logistical barriers.

School based strategic recommendations should firstly mandate that all public and private educational institutions especially those in low-income communities to provide free menstrual products in all school restrooms. Secondly, there should be immediate incorporation of menstrual health education into the academic curricula within schools, preferably beginning in middle schools nationwide. Finally, there should be strategic training of staff to reduce stigma and improve the response to students’ menstrual health needs within schools, making it a more conducive environment for persons experiencing menstruation. Some states, such as California, New York, and Illinois, have already implemented school-based legislation requiring access to free period products, a model that should be expanded across all states [31].

5.3. Access Within Public Institutions

Spaces open to the public such as libraries, transit stations, community centers, shelters, and correctional facilities should ensure the availability of menstrual products, just as they all make provisions for toilet paper and soap. It is important to address racially disparate outcomes, with Black women being approximately 6.5 to 8 times more likely to be imprisoned than non-Black women within the USA [68]. Often, incarcerated individuals who are Black, Hispanic and living within low-income communities face harsh limitations in accessing menstrual supplies, sometimes being forced to use makeshift alternatives [69].

Recommendations to improve period poverty within public institutions should include mandating all federal and state institutions to have menstrual products in public buildings and correctional facilities. Additionally, there should be consistent allocation of funds for homeless shelters and public health programs to stock period products. Finally, there must be implementation of oversight mechanisms to ensure compliance and equitable distribution of such resources.

5.4. Awareness Creation, Public Sensitization and Destigmatization

The perception and understanding of the general public on menstruation remains low, often encouraging the reinforcement of shame and silence towards menstruating individuals. Some religious and traditional beliefs of people living in the U.S concerning menstruation deepen the stigma associated with menstruation. In some religions, women are not allowed to worship or pray or even sleep in the same room with their partners whiles experiencing menstruation. Such beliefs go a long way to deepen the culture of silence surrounding menstruation. It is therefore important that awareness campaigns target and focus on such beliefs in order to normalize the conversation around menstruation. This, when done right, would highlight existing inequities, to drive home the needed change we desire to see.

Some initiatives have already started making an impact such as the 2019 award-winning Netflix documentary “Period. End of Sentence.” It was initiated by The Pad Project to draw attention to the issues associated with period poverty. Another such initiative is the social media movement #EndPeriodPoverty that centers youth voices and personal stories in the fight against period poverty.

Some recommendations to create needed awareness include the development of strategic partnerships with various social media influencers, health care professionals and educators to develop messaging aimed at addressing the numerous myths and barriers associated with menstruation. By breaking these myths and barriers, proper menstrual equity can then be promoted within the society. However, these public messaging campaigns should aim to be culturally sensitive, inclusive and multilingual in nature to accommodate the diverse menstruating experiences that exist to achieve a greater impact.

5.5. Inclusive Approach

Period poverty generally burdens people of color, LGBTQ+, low-income individuals, those living with disabilities, and people incarcerated or experiencing homelessness [46,70]. The intersection of race, gender identity, socioeconomic status and disability should be thoroughly explored so as to develop an effective response to the period poverty needs of these individuals.

The following recommendations are proposed to help in the adoption of inclusive approaches in the fight against period poverty. First is to include the recognition that not all who menstruate identify as women therefore ensuring the use of language and policies that are gender inclusive. Additionally, symbiotic partnerships with community-based organizations that serve marginalized groups can be developed to co-design inclusive interventions that help address period poverty. Finally, promote the development of programs that address structural racism and economic inequality which are the root causes of period poverty. These policies would achieve maximum effect by basing solutions in equity and inclusion, policy and advocacy which can reach those most affected while fostering systemic change.

5.6. Healthcare Integration

Menstrual health is primarily a healthcare issue, yet it is often overlooked in both policy and clinical practice within the United States. Uterine fibroids occur more frequently in Black menstruators compared to white menstruators, and Black women experience worse outcomes overall with fibroids and endometriosis management (Malini et al. 2023) [71].Many menstruators, especially those experiencing abnormal cycles, painful, or heavy menstrual bleeding, do not often receive timely medical evaluation or treatment due to societal stigma and limited provider education on menstrual disorders [72]. For example, conditions like endometriosis and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) are commonly misdiagnosed or dismissed, leading to long-term health impacts on the patient.

It is important therefore that, menstrual health be recognized as a basic aspect of preventive care within the healthcare settings of the United States. Community health clinics and reproductive health providers are well positioned to offer menstrual education, distribute products, and refer individuals to appropriate services. Unfortunately, these essential services are inconsistently available and often underfunded.

Recommendations for improving healthcare integration include the training of healthcare professionals to discuss menstruation routinely and sensitively with patients within their settings. Additionally, menstrual health assessment should be included in pre- employment checkups and annual checkups, especially for adolescents and young adults. There should also be an expansion in insurance coverage and Medicare/Medicaid to include menstrual hygiene products.

5.7. Workplace and Employment Protections

Many menstruating individuals often spend their working lives whiles experiencing menstruation as the average age of menopause within the United States is 52 [73]. Many people who experience menstruation therefore face challenges managing their periods at work due to the lack of access to private restrooms, menstrual supplies, and flexibility of schedules for health-related needs. This is especially problematic for individuals in low-wage or manual labor jobs, who may not be able to take unscheduled breaks or afford to miss work due to menstrual discomfort [74].

Menstrual needs should be treated as a workplace equity issue, particularly under occupational health and safety regulations. Inclusive workplace practices can therefore help reduce absenteeism, improve morale, and ensure that menstruation does not interfere with employment opportunities.

The following recommendations are proposed to increase workplace and employment protection for those experiencing menstruation. First, employers should be required to stock menstrual products in restrooms, like soap or toilet paper within the workplace. Additionally, they should implement workplace policies that accommodate for severe menstrual symptoms under existing labor protections. Finally, labor unions and employee resource groups should be encouraged to advocate for menstrual equity policies for their members.

5.8. Innovation and Sustainability in Product Design

Period poverty has a direct intersection with environmental sustainability due to the high volume of menstrual products used annual. Only 18% of women from a 11,455-cohort used renewable cup for collecting their menstrual blood whiles the remaining preferred to use single-use products [75]. Single-use products such as pads and tampons generate significant waste, and their recurring cost places a financial burden on low-income individuals. Reusable menstrual products such as cups, reusable pads, and period underwear offer more sustainable and cost-effective alternatives, but barriers remain in the adoption of such products. These barriers include cultural stigma, access to clean water and sanitation, and lack of education on the use of reusable sanitary products [76].

Innovation in the development of menstrual product design particularly focusing on affordable, biodegradable, and reusable options must be paired with education to ensure acceptance. Programs that aim to increase adoption of reusable menstrual products must also consider barriers peculiar to people in rural or underserved urban areas where access to clean water may be limited. The following recommendation would be idle in improving innovation and sustainability in product design to help combat period poverty. First is to create an avenue for increased public and private investment in the development and distribution of sustainable menstrual products by developing strategic tax incentives, easy access to funding for start-ups focused on the development of sustainable and environmentally friendly products. Secondly, ensuring all federal and states agencies purchase reusable product kits for schools, shelters, and healthcare facilities. Finally, to create and launch culturally sensitive educational campaigns on product safety, use, and maintenance within the community to encourage adoption and use of these alternative products.

5.9. Data Collection and Research

The role of research and accurate data collection cannot be over emphasized in the quest to address period poverty within the United States. It is however unfortunate that most national health surveys fail to capture menstrual health indicators resulting in lack of visibility in both policy and funding currently being experienced. Without concrete data, assessing the scope of period poverty becomes difficult as one is unable to effectively identify its affected population, or even measure the effectiveness of existing interventions.

Developing a strong evidence base goes a long way in addressing the challenges of period poverty by allowing for better informed decision making and focused advocacy for change by policy makers. By sorting out data into age, race, gender identity, income level and geographic location, policy makers would be better equipped in designing targeted interventions aimed at eradicating period poverty.

It is therefore recommended that menstrual health indicators be included in federal surveys such as NHANES and the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. Additionally, both federal and states should make available funds for research into menstrual equity through agencies like the NIH and CDC. Finally, both federal and state governments must encourage academic institutions and grassroots organizations to collect community level data to support research on period poverty.

5.10. Emergency and Disaster Response Preparedness

During the unfortunate events of emergencies such as natural disasters, humanitarian displacement, and health crises, the menstrual health needs of most affected individuals are often neglected. During the COVID-19 pandemic, a UNESCO report on school closures concluded that supply chain disruptions made it significantly harder for many to access menstrual products [77]. Emergency shelters, usually setup during emergencies, often are under stocked with menstrual hygiene products for use by affected individuals and this can often lead to unsanitary practices that can result in serious health implications such as genitourinary infections. During these unfortunate periods of emergency and disaster response, the reproductive health needs of women are often not the focus or sometimes even forgotten or neglected as they are not usually considered essential as compared to food, shelter, and water. Federal and State emergency preparedness plans must account for menstrual health as part of basic dignity and hygiene needs. This is especially vital for displaced populations, including migrants, refugees, and victims of domestic violence. It is therefore recommended that both federal and state governments include menstrual products in FEMA emergency relief supply lists and public shelter provisions. Additionally, partnership should be developed with humanitarian relief organizations to ensure that menstrual health education and menstrual hygiene needs are met during crisis response.

6. Conclusions

In summary, “period poverty” refers to the inability to obtain resources including necessary education, menstrual hygiene products, and proper sanitation during menstruation. For afflicted individuals, period poverty can have a major impact on their physical, mental, reproductive and emotional health; adversely affect educational outcomes; pose economic strain; lead to absenteeism from school and work; create barriers to healthcare access; and perpetuate poor health outcomes across generations. Barriers to menstrual equity or access to safe, affordable, accessible menstrual products, education and environments, include lack of access to period support, cost, inadequate sanitation facilities, lack of education, societal and cultural stigma and legislative barriers.

To address this issue, it is crucial to actively advocate initiatives that seek to increase access to menstrual hygiene products, increase public awareness, and educate individuals on safe menstruation habits. We recommend policy reforms through federal and state governmental action, school-based approaches that incorporate menstrual health education into the academic curricula and the strategic training of staff, increased access to menstrual products in public institutions, creating awareness and destigmatizing the culture of silence surrounding menstruation and adopting inclusive approaches in the fight against period poverty. We also propose integrating menstrual health into policy and clinical practice, treating menstrual health as a workplace equity and occupational health and safety issue, promoting the design of innovative and sustainable menstrual products, adopting scientific, data-driven, and cross-sectional approaches and accounting for menstrual health as part of emergency and disaster response preparedness plans. These measures can help mitigate the adverse impacts of unequal access to sanitary facilities, education, and menstruation products and help promote menstrual equity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.-H. and S.T.; methodology, M.A.-H., S.T., A.N. and K.G.; validation, A.N., M.A.-H., S.T. and K.G.; formal analysis, M.A.-H., S.T. and A.N.; investigation, M.A.-H., S.T., K.G. and A.N.; resources, A.N.; data curation, M.A.-H., S.T., K.G. and A.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.-H., K.G., S.T. and A.N.; writing—review and editing, A.N., M.A.-H., K.G. and S.T.; visualization, A.N.; supervision, A.N.; project administration, A.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- National Library of Medicine Menstruation. Available online: https://medlineplus.gov/menstruation.html (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- WHO Statement on Menstrual Health and Rights. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/22-06-2022-who-statement-on-menstrual-health-and-rights (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Period Poverty—American Medical Women’s Association. Available online: https://www.amwa-doc.org/period-poverty/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Harrison, M.E.; Tyson, N. Menstruation: Environmental Impact and Need for Global Health Equity. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 160, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennegan, J.; Sol, L. Confidence to Manage Menstruation at Home and at School: Findings from a Cross-Sectional Survey of Schoolgirls in Rural Bangladesh. Cult. Health Sex. 2020, 22, 146–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, H.; Ismail, S.Y.; Azzeri, A. Period Poverty: A Neglected Public Health Issue. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2023, 44, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, J.; Mettler, A.; Schönenberger, S.; Gunz, D. Period Poverty: Why It Should Be Everybody’s Business. J. Glob. Health Rep. 2022, 6, e2022009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohatgi, A.; Dash, S. Period Poverty and Mental Health of Menstruators during COVID-19 Pandemic: Lessons and Implications for the Future. Front. Glob. Womens Health 2023, 4, 1128169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peberdy, E.; Jones, A.; Green, D. A Study into Public Awareness of the Environmental Impact of Menstrual Products and Product Choice. Sustainability 2019, 11, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crays, A. Menstrual Equity and Justice in the United States. Sex. Gend. Policy 2020, 3, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacca, L.; Lobaina, D.; Burgoa, S.; Jhumkhawala, V.; Rao, M.; Okwaraji, G.; Zerrouki, Y.; Sohmer, J.; Knecht, M.; Mejia, M.C.; et al. Period Poverty and Barriers to Menstrual Health Equity in U.S. Menstruating College Students: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, M.; Mason, D.J. Period Poverty and Promoting Menstrual Equity. JAMA Health Forum 2021, 2, e213089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedrick, B.S.; Hamilton, S.; Sufrin, C. Assessment of Menstrual Material Needs as a Measure of Health and Menstrual Equity in the Postpartum Period. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2025, 44, 101108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, J.; Courtney, R.; Edwards, B. Advancing Women’s Health Equity and Empowerment: Exploring Period Poverty and Menstrual Hygiene. Health Mark. Q. 2024, 41, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, M.; Phillips-Howard, P.A.; Gruer, C.; Schmitt, M.L.; Nguyen, A.-M.; Berry, A.; Kochhar, S.; Gorrell Kulkarni, S.; Nash, D.; Maroko, A.R. Menstrual Product Insecurity Resulting From COVID-19—Related Income Loss, United States, 2020. Am. J. Public Health 2022, 112, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, L.C.; Adkins-Jackson, P.B. Mixed-Method, Multilevel Clustered-Randomized Control Trial for Menstrual Health Disparities. Prev. Sci. 2024, 25, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Period Poverty: The Public Health Crisis We Don’t Talk About|PolicyLab. Available online: https://policylab.chop.edu/blog/period-poverty-public-health-crisis-we-dont-talk-about (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Harrison, M.E.; Davies, S.; Tyson, N.; Swartzendruber, A.; Grubb, L.K.; Alderman, E.M. NASPAG Position Statement: Eliminating Period Poverty in Adolescents and Young Adults Living in North America. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2022, 35, 609–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacca, L.; Markham, C.M.; Gupta, J.; Peskin, M. Editorial: Period Poverty. Front. Reprod. Health 2023, 5, 1140981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebert Kuhlmann, A.; Palovick, K.A.; Teni, M.T.; Hunter, E. Period Product Resources and Needs in Schools: A Statewide Survey of Missouri’s School Nurses. J. Sch. Health 2023, 93, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casola, A.R.; Luber, K.; Riley, A.H.; Medley, L. Menstrual Health: Taking Action Against Period Poverty. Am. J. Public Health 2022, 112, 374–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philipp, J. Reducing Period Poverty in Malaysia. The Borgen Project. 2020. Available online: https://borgenproject.org/period-poverty-in-malaysia/ (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Mann, S.; Byrne, S.K. Period Poverty from a Public Health and Legislative Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 7118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, V.; Nabwera, H.M.; Sosseh, F.; Jallow, Y.; Comma, E.; Keita, O.; Torondel, B. A Rite of Passage: A Mixed Methodology Study about Knowledge, Perceptions and Practices of Menstrual Hygiene Management in Rural Gambia. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, P.; Baker, K.K.; Dutta, A.; Swain, T.; Sahoo, S.; Das, B.S.; Panda, B.; Nayak, A.; Bara, M.; Bilung, B.; et al. Menstrual Hygiene Practices, WASH Access and the Risk of Urogenital Infection in Women from Odisha, India. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soeiro, R.E.; Rocha, L.; Surita, F.G.; Bahamondes, L.; Costa, M.L. Period Poverty: Menstrual Health Hygiene Issues among Adolescent and Young Venezuelan Migrant Women at the Northwestern Border of Brazil. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godlove Aka, B. Period Poverty in the United States of America: A Socio-Economic Policy Analysis. J. Glob. Health Econ. Policy 2025, 5, e2025017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Tohit, N.F.; Haque, M. Breaking the Cycle: Addressing Period Poverty as a Critical Public Health Challenge and Its Relation to Sustainable Development Goals. Cureus 2024, 16, e62499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.; Darien, K.; Pennotti, R.; McGlone, N. Medley Achieving Equitable Access to Menstrual Health Care and Products for Adolescents and Young Adults. Available online: https://policylab.chop.edu/issue-briefs/achieving-equitable-access-menstrual-health-care-and-products-adolescents-and-young (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Jewitt, S.; Ryley, H. It’s a Girl Thing: Menstruation, School Attendance, Spatial Mobility and Wider Gender Inequalities in Kenya. Geoforum 2014, 56, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, L.F.; Scolese, A.M.; Hamidaddin, A.; Gupta, J. Period Poverty and Mental Health Implications among College-Aged Women in the United States. BMC Womens Health 2021, 21, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Zhang, J.; Segars, J. Period Poverty and the Menstrual Product Tax in the United States [29F]. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 135, 68S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rome, E.S.; Tyson, N. Menstrual Equity. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2024, 51, 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menstrual Health Is a Fundamental Human Right. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/15-08-2024-menstrual-health-is-a-fundamental-human-right (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Regional Health–Americas, T.L. Menstrual Health: A Neglected Public Health Problem. Lancet Reg. Health—Am. 2022, 15, 100399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraes, M.F.R.C.D.; Nunes, R.; Duarte, I. Period Poverty in Brazil: A Public Health Emergency. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoku, A.; Evans, M.; Nimo-Sefah, L.; Bailey, J. Listen to the Whispers before They Become Screams: Addressing Black Maternal Morbidity and Mortality in the United States. Healthcare 2023, 11, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Asokan, G.; Onnela, J.-P.; Baird, D.D.; Jukic, A.M.Z.; Wilcox, A.J.; Curry, C.L.; Fischer-Colbrie, T.; Williams, M.A.; Hauser, R.; et al. Menarche and Time to Cycle Regularity Among Individuals Born Between 1950 and 2005 in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2412854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikanth, N.; Xie, L.; Francis, J.; Messiah, S.E. Association of Social Determinants of Health, Race and Ethnicity, and Age of Menarche among US Women Over 2 Decades. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2023, 36, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reagan, P.B.; Salsberry, P.J.; Fang, M.Z.; Gardner, W.P.; Pajer, K. African-American/White Differences in the Age of Menarche: Accounting for the Difference. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 1263–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, T.N.; Rosinger, A.Y. Reproductive Health Disparities in the USA: Self-Reported Race/Ethnicity Predicts Age of Menarche and Live Birth Ratios, but Not Infertility. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2021, 8, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Study Updates | Apple Women’s Health Study|Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. 2024. Available online: https://hsph.harvard.edu/research/apple-womens-health-study/ (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- US Census Bureau Income in the United States: 2024. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2025/demo/p60-286.html (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Rossouw, L.; Ross, H. Understanding Period Poverty: Socio-Economic Inequalities in Menstrual Hygiene Management in Eight Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF Strategy for Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 2016–2030|UNICEF. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/documents/unicef-strategy-water-sanitation-and-hygiene-2016-2030 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- DeMaria, A.L.; Martinez, R.; Otten, E.; Schnolis, E.; Hrubiak, S.; Frank, J.; Cromer, R.; Ruiz, Y.; Rodriguez, N.M. Menstruating While Homeless: Navigating Access to Products, Spaces, and Services. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cree, R.A.; Okoro, C.A.; Zack, M.M.; Carbone, E. Frequent Mental Distress Among Adults, by Disability Status, Disability Type, and Selected Characteristics—United States, 2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1238–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips-Howard, P.A. What’s the Bleeding Problem: Menstrual Health and Living with a Disability. Lancet Reg. Health—West. Pac. 2022, 19, 100349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilbur, J.; Morrison, C.; Iakavai, J.; Shem, J.; Poilapa, R.; Bambery, L.; Baker, S.; Tanguay, J.; Sheppard, P.; Banks, L.M.; et al. “The Weather Is Not Good”: Exploring the Menstrual Health Experiences of Menstruators with and without Disabilities in Vanuatu. Lancet Reg. Health—West. Pac. 2022, 18, 100325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidance on Menstrual Health and Hygiene | UNICEF. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/documents/guidance-menstrual-health-and-hygiene (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Weiss, M.C.; Wang, L.; Sargis, R.M. Hormonal Injustice. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 52, 719–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.A.; Farley, M.; Reji, J.; Obeidi, Y.; Kelley, V.; Herbert, M. Understanding Period Poverty and Stigma: Highlighting the Need for Improved Public Health Initiatives and Provider Awareness. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2024, 64, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, M.; Sahin, M. Overcoming the Taboo: Advancing the Global Agenda for Menstrual Hygiene Management for Schoolgirls. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 1556–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGraw, G. The United States Needs Its Own WASH Sector. Available online: https://philanthropynewsdigest.org/features/ssir-pnd/the-united-states-needs-its-own-wash-sector (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Schmitt, M.L.; Hagstrom, C.; Nowara, A.; Gruer, C.; Adenu-Mensah, N.E.; Keeley, K.; Sommer, M. The Intersection of Menstruation, School and Family: Experiences of Girls Growing up in Urban Cities in the U.S.A. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2021, 26, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State of the Period 2023. Available online: https://www.thinx.com/blogs/periodical/state-of-the-period-2023 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Bergen, S.; Maughan, E.D.; Johnson, K.E.; Cogan, R.; Secor, M.; Sommer, M. The History of US Menstrual Health, School Nurses, and the Future of Menstrual Health Equity. Am. J. Public Health 2024, 114, 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WASH in Schools Empowers Girls’ Education in Freetown, Sierra Leone: An Assessment of Menstrual Hygiene Management in Schools—Coalition for Adolescent Girls (CAG). Available online: https://coalition-for-adolescent-girls.org/wash-in-schools-empowers-girls-education-in-freetown-sierra-leone-an-assessment-of-menstrual-hygiene-management-in-schools/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- 2024 PRRI Census of American Religion—PRRI. Available online: https://prri.org/spotlight/2024-prri-census-of-american-religion/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Anthony, N. Menstrual Taboos: Religious Practices That Violate Women’s Human Rights. Int. Hum. Rights Law Rev. 2020, 9, 291–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, I. Menstruation and Religion: Developing a Critical Menstrual Studies Approach. In The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies; Bobel, C., Winkler, I.T., Fahs, B., Hasson, K.A., Kissling, E.A., Roberts, T.-A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 115–129. ISBN 978-981-15-0613-0. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, D.S.J.; Aguilar, S.X.J.; Feijo, M.E.; Crespo, B.V. Beliefs-Related Menstruation: A Review Based on Scientific Evidence. Ginecol. Obstet. México 2025, 93, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampon Tax—Alliance for Period Supplies. Available online: https://allianceforperiodsupplies.org/tampon-tax/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Menstrual Tampons and Pads: Information for Premarket Notification Submissions (510(k)s)—Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/menstrual-tampons-and-pads-information-premarket-notification-submissions-510ks-guidance-industry (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Bildhauer, B.; Røstvik, C.M.; Vostral, S.L. Introduction: The Period Products (Free Provision) (Scotland) Act 2021 in the Context of Menstrual Politics and History. Open Libr. Humanit. 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Villarreal, A. Taxing Women’s Bodies: The State of Menstrual Product Taxes in the Americas. Lancet Reg. Health—Am. 2024, 29, 100637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvard Public Health Magazine; Burtka, A.T. “It’s a Dignity Issue”: Inside the Movement Tackling Period Poverty in the U.S. Harvard Public Health Magazine. 2023. Available online: https://theemancipator.org/2023/08/09/topics/health-equity/its-dignity-issue-inside-movement-tackling-period-poverty-us/ (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Heimer, K.; Malone, S.E.; De Coster, S. Trends in Women’s Incarceration Rates in US Prisons and Jails: A Tale of Inequalities. Annu. Rev. Criminol. 2023, 6, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darivemula, S.; Knittel, A.; Flowers, L.; Moore, S.; Hall, B.; Kelecha, H.; Li, X.; Ramaswamy, M.; Kelly, P.J. Menstrual Equity in the Criminal Legal System. J. Womens Health 2023, 32, 927–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queering Menstruation | Centers for Educational Justice & Community Engagement. Available online: https://cejce.berkeley.edu/centers/gender-equity-resource-center/resources/womens-resources/advocacy-issues/menstrual-equity-1 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Ramaiyer, M.; Lulseged, B.; Michel, R.; Ali, F.; Liang, J.; Borahay, M.A. Menstruation in the USA. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2023, 10, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byams, V.R.; Miller, C.H.; Bethea, F.M.; Abe, K.; Bean, C.J.; Schieve, L.A. Bleeding Disorders in Women and Girls: State of the Science and CDC Collaborative Programs. J. Womens Health 2022, 31, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What Is Menopause? | National Institute on Aging. Available online: https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/menopause/what-menopause (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Casola, A.R.; Luber, K.; Riley, A.H. Period Poverty: An Epidemiologic and Biopsychosocial Analysis. Health Promot. Pract. 2025, 26, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Peebles, E.; Baird, D.D.; Jukic, A.M.Z.; Wilcox, A.J.; Curry, C.L.; Fischer-Colbrie, T.; Onnela, J.-P.; Williams, M.A.; Hauser, R.; et al. Menstrual Product Use Patterns in a Large Digital Cohort in the United States: Variations by Sociodemographic, Health, and Menstrual Characteristics. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2025, 233, 184.e1–184.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobel, C.; Winkler, I.T.; Fahs, B.; Hasson, K.A.; Kissling, E.A.; Roberts, T.-A. (Eds.) The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies; Springer: Singapore, 2020; ISBN 978-981-15-0613-0. [Google Scholar]

- When Schools Shut: Gendered Impacts of COVID-19 School Closures. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379270 (accessed on 25 July 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).