Abstract

Chlorella is a valuable object of biotechnology with high productivity of biomass and metabolites. The use of Chlorella for CO2 binding in autotrophic metabolism is also discussed. Various types of stress are used to increase the yield of valuable metabolites. One of the effective approaches may be dark stress. However, there is insufficient data to fully understand the effect of dark stress on productivity, biochemical parameters, the antioxidant system, and the rate of CO2 fixation by Chlorella during the transfer from autotrophic culture to aphotic conditions. To study these processes, we used two-step cultivation. In the second step, the biomass was grown for 96 h on a BBM medium under standard lighting and in aphotic conditions. According to the results of the study, the metabolic systems of the studied strain of Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 specifically react to cultivation under aphotic conditions. The greatest response was found in lipid–protein metabolism and the antioxidant defense system, which determines an increase in the overall antioxidant status of cells. At the same time, productivity, CO2 absorption characteristics, and pigment composition of the photosynthetic system did not change after 96 h of darkening. In general, this approach is a promising strategy for increasing biotechnological productions efficiency.

1. Introduction

The biological diversity of microalgae is extensive, encompassing species with unique properties and metabolic capabilities [1]. Numerous studies confirm the significant potential of using microalgae to produce various biologically active compounds. These compounds are in high demand by the food and feed industries, as well as in the production of pharmaceutical and cosmetic preparations [2]. Microalgae have also found applications in solving environmental problems, such as wastewater treatment and soil bioremediation [3,4,5]. Recent studies have shown the significant potential of microalgae in addressing global climate change caused by greenhouse gases [6,7]. Microalgae offer promising prospects for their use in technologies that absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The biomass obtained in this process is also a source of valuable compounds, including amino acids, antioxidants, carotenoids, vitamins, and polyunsaturated fatty acids, as well as a raw material for the production of biofuels, biogas, and biochar [8]. Such an integrated approach to the use of biomass can serve as the basis for reviewing the cost of products produced from microalgae. Many sources from the literature indicate that the main obstacle to the widespread use of microalgae biomass in various fields of production is the high cost of the products obtained from it. The costs of lighting, mixing, isolation, and purification of the product, as well as the low productivity of the biomass from the strain, result in a high price for the final product [9]. Traditional cost reduction strategies are primarily based on the search for new highly productive microalgae species and strains, altering microalgae metabolism, and increasing the yield of valuable compounds through abiotic stress, metabolic, and genetic engineering [10,11].

Obviously, the sequestration effect can become an additional parameter for assessing the economic profitability of industries that use microalgae biomass. Tracking the processes of carbon uptake by microalgae, as well as the duration of its storage in biomass or the resulting products, may become a separate area of research and contribute to mitigating the effects of climate change. In general, this aligns with the principles of nature-like technologies and the efficient use of natural resources.

Chlorella Beyerinck [Beijerinck] species have great biotechnological potential [6,12]. They are known for producing lipids, proteins, carotenoids, vitamins, valuable polyunsaturated fatty acids, and other commercially valuable compounds. Current research focuses on identifying factors that will increase the productivity of Chlorella species, including nutritional stress, exposure to light of varying intensity, changes in pH and temperature, and the use of various wastewaters for cultivation [6,10,13,14,15]. Many researchers are also discussing the use of Chlorella to absorb carbon dioxide [6,16,17], which may contribute to the advancement of Chlorella cultivation technologies. Researchers attach great importance to the ability of Chlorella to fix CO2 during autotrophic metabolism, as well as the use of organic carbon compounds in mixotrophic and heterotrophic growth [6,14].

The question of the priority of using carbon from CO2 during photosynthesis or from organic compounds in mixotrophic cultivation remains open. Mousavi et al. [18] suggested both the possibility of simultaneous photosynthesis and heterotrophic growth, as well as the preferred use of CO2 in mixotrophic cultivation. These observations suggest that dark stress may reduce the cost of biomass in an intensively growing autotrophic Chlorella culture. The use of lighting at the first stage of cultivation allows for the rapid accumulation of biomass, and subsequent exposure to darkness initiates metabolic rearrangements, producing biomass with a more valuable biochemical composition. The analysis of data from the literature demonstrates that the available data are insufficient to fully understand the changes in the productivity and biochemical composition of Chlorella under the influence of dark stress on cultures growing in autotrophic conditions, as well as the degree of oxidative stress manifestation in aphotic growth conditions. It is also unclear whether the CO2-sequestration effect achieved through autotrophic metabolism will persist with further culture growth under aphotic conditions.

The purpose of this work was to investigate, using the example of a model strain of Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145, the possibility of using acute aphotic stress for the induced accumulation of biotechnologically valuable compounds against the background of activation of the strain’s antioxidant system and preservation of the achieved sequestration effect.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microalgae Material

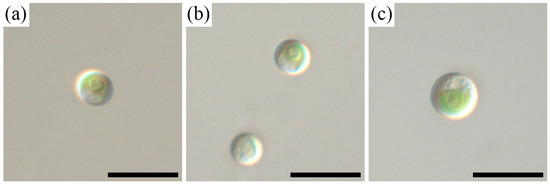

The soil strain of Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 (Figure 1) was isolated from the soil (pH 6.8, humus 6.1%) of a forest (Quercus robur L. plantation) near Aderbiyevka (Gelendzhik district, Krasnodar region, Russia). The monoclonal strain Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145, isolated by micropipetting from a soil culture with fouling glasses, was the material used for research [19]. Light microscopic observations were performed with a Zeiss Axio Scope A1 (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Göttingen, Germany) microscope equipped with an oil immersion objective (Plan-apochromatic ×100/n.a.1.4, Nomarski differential interference contrast, DIC) and a Zeiss Axio Cam ERc 5s camera (Carl Zeiss NTS Ltd., Oberkochen, Germany).

Figure 1.

Nomarski interference micrographs of the strain Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 in culture. Scale bar = 10 μm. Young vegetative cells, 2 weeks of age (a,b). Mature vegetative cell, 4 weeks of age (c).

The Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 strain was deposited in the Algae collection of Molecular systematics of aquatic plants at K.A. Timiryazev Institute of Plant Physiology RAS and the Collection of algae at Melitopol state university CAMU (WDCM1158) as unialgal cultures. The strain was stored at 15.0 ± 2.0 °C in vials illuminated by white diodes with a light intensity of 120 lx and a light mode of 16:8 h (light/dark) in a BBM medium [20].

A culture in the exponential phase was used for the two-step experiments. In the first stage, Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 biomass was inoculated in 150.0 mL of fresh BBM so that the initial cell concentration was 2.75 × 105 cells mL−1. The cell concentration was measured using an automatic cell counter C100 (RWD Life Science, Shenzhen, China). After 15 days of growth, this culture was used for introduction into experimental media (second step).

2.2. Experimental Design

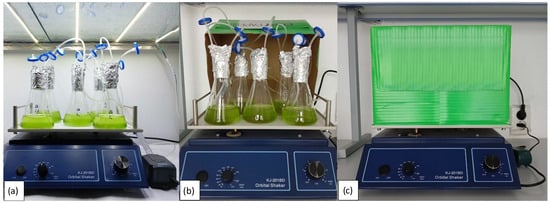

As reactors, we used flat-bottomed 250 mL flasks with sealed lids and a system that ensures the consistency of the composition of the gas–air mixture in the flask (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The cultivation system. Reactors with a gas exchange and contamination prevention system on a shaker under standard lighting (group A) (a), and under aphotic conditions (group B) (b,c).

The Hailea ACO-308 aquarium compressor (Hailea, Chaozhou, China) supplied air for the aeration of cell cultures. The air was supplied through a tube with an inner diameter of 4 mm at a rate of 0.1 L min−1. The air was taken from a constantly ventilated room. The volume fraction of carbon dioxide in the air was maintained at 549–565 ppm (Table 1). The carbon dioxide volume fraction in the air was monitored using an AZ7752 gas analyzer (AZ Instrument, Taichung, Taiwan). To prevent bacterial contamination of the culture, we used a bacterial ventilation filter (GSV, Bologna, Italy) with a diameter of 40 mm (pore size—0.22 µm). The filter was located in the gap between the compressor and the tube and at the outlet of the reactor. The strain was grown at a temperature of 23.0 ± 2.0 °C. The light intensity was 5000 ± 170 lx (70.0 ± 0.46 µM photons s−1 m−2) and the lighting mode was 16:8 (light/dark) (Table 1). These lighting conditions are accepted in this work as standard [20]. The light intensity were measured using the Hopoocolor OHSP-350P lighting analyzer (Hangzhou Hopoo Light and Colour Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China). Cell cultures were cultured by constant shaking at a frequency of 60 rpm using a KJ-201 BD orbital shaker (Pioway Medical Lab Equipment, Nanjing, China). In the second step, the biomass, grown under standard lighting conditions (the first step of cultivation), was diluted with fresh BBM medium and used for a 96 h cultivation in Erlenmeyer flasks under different conditions: group A—cultivation under standard lighting; group B—cultivation under aphotic conditions. Five experimental repetitions were used for each group. Group A was the control group. The biomass density in the experimental groups was 0.30 ± 0.01 g L−1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the air and light supplied to the culture reactor in group A and group B (M ± SD, n = 3).

2.3. Growth Assessment and Rate of CO2 Biofixation

The growth was observed for 96 h. The growth of microalgae was estimated by measuring dry weight (DW). The DW of the biomass was estimated gravimetrically. To do this, we filtered 10 mL of the culture through a «blue ribbon» filter with a 2–3 µm pore size (LLC «Melior XXI», Moscow, Russia). The filter was pre-weighed on an analytical scale AS220.R2 (RADWAG, Radom, Poland) and aged for 6 h at 105 °C in a Bios BO-50N drying cabinet (JSC «Labtex», Moscow, Russia). After the filtration, the biomass-containing filter was dried at 105 °C for 12 h and then weighed. The measured dry weight is expressed in g L−1. Biomass productivity (P, g L−1 day−1) was estimated using the following equation:

where x2 (g L−1) is the concentration of the biomass at the end of the cultivation time t2 (day) and x1 (g L−1) is the concentration of the biomass at the beginning of the cultivation time t1 (day) [21].

P (g L−1 day−1) = (x2 − x1) (t2 − t1)−1

The rate of CO2 biofixation (F, g CO2 L−1 day−1) was calculated for biomass productivity (P) according to the following equation [22]:

where P is the productivity of biomass (g L−1 day−1).

F (g CO2 L−1 day−1) = 1.88 P

2.4. Biochemical Parameters Measured

Biochemical characteristics like ascorbic acid, phenolic compounds, chlorophyll a (Chl a), chlorophyll b (Chl b), carotenoids (Car), astaxanthin content (Astx.), lipids, protein, thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBA-active substances) content in homogenate before (TBARS) and after Fe2+ lipid peroxidation initiating (TBARSin), and lipids hydrogen peroxides (Hpx) content were carried out according to the scheme presented in our previous studies [23]. Also, the coefficient of antioxidant activity (KAAC) was calculated according to the protocol described in our previous work [23].

To analyze the enzyme activity, we prepared an enzyme extract beforehand. To do this, 0.1 g of biomass was separated from the medium by centrifugation (10 min at 3000 rpm), then 0.9 mL of phosphate buffer (0.01 M; pH 7.4) was added to the biomass and homogenized for 30 s using a JY92-IIN ultrasonic homogenizer (Scientz Biotechnology, Ningbo, China) (horn diameter 6 mm, power 65 W, frequency 25 kHz) at a constant temperature of 2–4 °C. The resulting homogenate was centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 rpm, and the resulting supernatant was used to analyze enzyme activity on the same day.

The catalase activity (CAT) (EC 1.11.1.6) was determined using the Hamza and Hadwan [24] method, with our modification. The volume of the reaction medium was 3 mL. To start the reaction, 0.05 mL of the supernatant was added to 2 mL of hydrogen peroxide (10 mM) and incubated for 10 min at 30 °C. After 10 min, 1 mL of the working reagent (0.04 M aniline sulfate, 0.125 M hydroquinone, 0.04 M ammonium molybdate) was added to the medium and kept at room temperature for 10 min, and then the spectrophotometric measurement was taken at 550 nm. The concentration of reacted hydrogen peroxide, used to measure activity, was determined by the calibration curve of the interaction of hydrogen peroxide of the known concentration with the working solution.

Glutathione peroxidase activity (GPx) (EC 1.11.1.9) was determined by the Sattar et al. [25] method, with some modifications. The reaction medium contained 1.5 mL of phosphate buffer (0.01 M; pH 7.4), 0.2 mL of reduced glutathione (2 mM), and 0.05 mL of a supernatant. The reaction was started by adding 0.2 mL of hydrogen peroxide (2.1 mM) and incubating for 60 min. After that, we added 3 mL of sodium hydrophosphate and 1 mL of Elman’s reagent and we kept the samples for 10 min at 37 °C. The optical density of the solution was measured at 412 nm. To calculate the concentration of reacted glutathione and express enzyme activity, the molar extinction coefficient of the glutathione complex with Elman’s reagent was used [24].

Superoxide dismutase activity (SOD) (EC 1.15.1.1) was determined using the Sirota [26] method. To determine the enzyme activity, we prepared a reaction mixture that contained 2 mL of carbonate buffer (0.2 M; pH 10.5), nitroblue tetrazolium (50 µM), and 0.05 mL of a supernatant. The reaction was started by adding epinephrine chloride (0.23 mM) to the incubation medium and incubating for 3 min at 25 °C. The optical density was measured at 560 nm before and 3 min after adding adrenaline chloride. The activity was calculated using the equation in the method followed in [26].

2.5. Determination of the Cultivation Media Parameters

The parameters of the cultivation medium (concentration of dissolved oxygen (O2), pH, content of dissolved salts (Salts) in the initial BBM medium and after 96 h of cultivation) were determined using an AZ-86031 multimonitor of water quality (AZ Instrument, Taichung, Taiwan).

2.6. Data Analysis

Statistics were obtained in Microsoft Excel ver. 1903 software using single-factor dispersion analysis (ANOVA) [27]. The reliability of the differences between the indicators was calculated using the Tukey–Kramer posterior test. The differences at p ≤ 0.05 were considered reliable. The initial measurement data is provided in the link.

3. Results

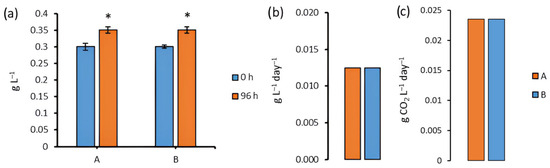

When cultivating a strain of Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145, we observed increased biomass concentration by 17% under aphotic conditions after 96 h of cultivation and by 17% relative to the initial amount under standard lighting conditions (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Biomass concentration (a), biomass productivity (b), and CO2 biofixation (c) of Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 under various conditions after 96 h of cultivation. Note: * The difference is significant relative to group A and B at 0 h of cultivation, at p < 0.05. A is BBM medium, standard lighting; B is BBM medium, aphotic conditions (M ± SD, n = 5).

After 96 h, there were no significant differences in biomass concentration and biomass productivity between the groups (Figure 3b).

Carbon dioxide biofixation remained at a constant level of 0.0235 g CO2 L−1 day−1 during cultivation for 96 h under both lighting and aphotic conditions (Figure 3c).

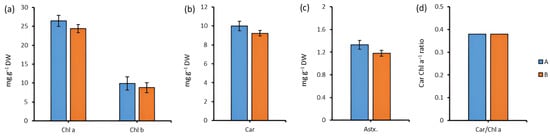

The content of Chl a and Chl b did not significantly change during cultivation in the dark relative to the control (Figure 4a), nor did total carotenoids (Figure 4b) or astaxanthin (Figure 4c). The ratio (Car/Chl a) determining the physiological status of the cell did not differ (Figure 4d).

Figure 4.

The content of Chl a, Chl b (a), Car (b), Astx. (c), and the ratio of Car/Chl a (d) for Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 under various cultivation conditions for 96 h. Note: A—BBM medium, standard lighting; B—BBM medium, aphotic conditions (M ± SD, n = 5).

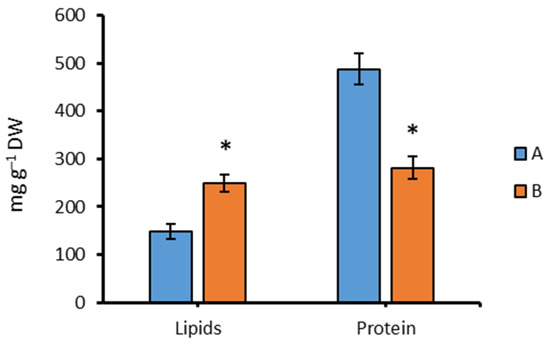

The total lipid content increased significantly when the strain grew for 96 h under aphotic conditions (B), increasing by 68.7% compared with group A (Figure 5). In contrast, the protein content decreased by 42.3% relative to group A after 96 h of cultivation in the dark.

Figure 5.

Lipids and protein content in Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 under various cultivation conditions for 96 h. Note: * The difference is significant relative to group A at the level of p < 0.05. A—BBM medium, standard lighting; B—BBM medium, aphotic conditions (M ± SD, n = 5).

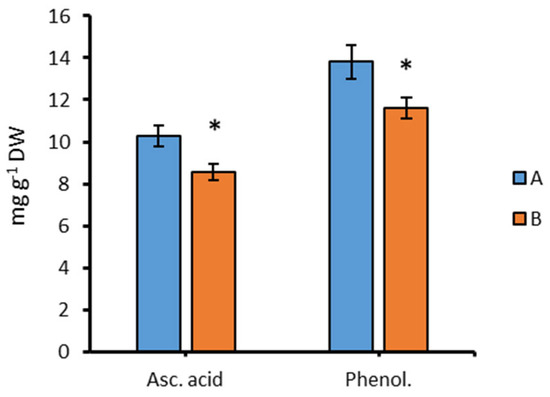

The content of ascorbic acid and phenolic compounds after 96 h of cultivation in the dark (B) significantly decreased relative to group A (Figure 6) by 17% and 16%, respectively.

Figure 6.

The content of ascorbic acid (Asc. acid) and phenolic compounds (Phenol.) in Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 under various cultivation conditions for 96 h. Note: * The difference is significant relative to group A at the level of p < 0.05. A—BBM medium, standard lighting; B—BBM medium, aphotic conditions (M ± SD, n = 5).

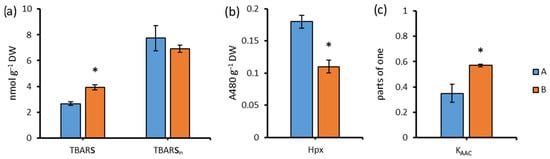

Under darkening conditions, peroxide oxidation increased for 96 h. The content of TBA-reactive substances increased by 47.4% when cultivated in the dark (Figure 7a). When activated by Fe2+ ions (Fenton reaction) in lipid peroxidation, the content of TBA-reactive substances did not differ between the groups cultivated in light and in the dark.

Figure 7.

The content of TBA-active products (a), Hpx (b), and the coefficient of antioxidant activity (c) in Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 under various cultivation conditions for 96 h. Note: * The difference is significant relative to group A at the level of p < 0.05. A—BBM medium, standard lighting; B—BBM medium, aphotic conditions (M ± SD, n = 5).

The content of Hpx decreased 1.6-fold relative to group A when cultured in the dark (B) (Figure 7b).

The antioxidant activity of the strain’s cells increased by 62.9% when cultured in the dark (B), compared to group A (Figure 7c).

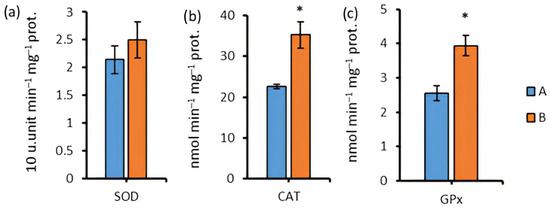

The enzymatic activity of the antioxidant system reacted specifically to darkening. SOD-activity did not significantly change (Figure 8a). CAT-activity increased by 56.2% after 96 h of cultivation under aphotic conditions (Figure 8b), and GPx-activity increased by 54.5% relative to group A (Figure 8c).

Figure 8.

SOD-activity (a), CAT-activity (b), and GPx-activity (c) in the biomass of Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 under various cultivation conditions for 96 h. Note: * The difference is significant relative to group A at the level of p < 0.05. A—BBM medium, standard lighting; B—BBM medium, aphotic conditions (M ± SD, n = 5).

The cultivation medium parameters did not differ within the group at the beginning and after 96 h of cultivation, and between the groups A and B (Table 2).

Table 2.

Parameters of the cultivation medium at the beginning and after 96 h of cultivation (M ± SD, n = 3).

4. Discussion

Microalgae exhibit high photosynthetic efficiency and a CO2 absorption rate that exceeds that of higher aquatic plants [28]. This determines the high interest in photoautotrophic microalgae cultivation systems. One of the significant disadvantages of this cultivation technology is an increase in cell self-shading as the culture grows, resulting in a subsequent decrease in biomass productivity [14]. Using high-intensity light to overcome this limitation can lead to photodamage of cells, especially those located near the light source, and consequently reduce productivity. It also increases the cost of providing lighting, which most affects the price of microalgae compounds [29]. Technologies for the mixotrophic cultivation of microalgae, as well as the utilization of the heterotrophic growth capabilities of certain types of microalgae, can enhance the efficiency of utilizing light energy [30]. Yun et al. [31] reported that mixotrophic and heterotrophic cultivation can increase the biomass productivity of Chlorella species. According to Qin et al. [32], an increase in biomass productivity is not always associated with an increase in the yield of valuable compounds, especially those associated with photosynthesis. Also, with mixotrophic and heterotrophic cultivation, there is a risk of bacterial and fungal contamination, which requires additional costs to maintain culture axenicity [33,34]. This suggests the need for further research on various modes of microalgae cultivation and the exploration of optimal options.

Xiao et al. [35] reported good results for biomass productivity and lutein accumulation in Auxenochlorella protothecoides (Krüger) Kalina & Puncochárová under heterotrophic–photoautotrophic cultivation. For this purpose, the authors initially obtained large volumes of biomass during heterotrophic growth (lasting 6 days), followed by further growth of the cell culture in a photoautotrophic medium for 5 days, resulting in the accumulation of lutein in large quantities. Fan et al. [36] successfully used a similar strategy to induce lipid synthesis by three Chlorella species. The authors called this strategy «Sequential heterotrophy–dilution–photoinduction cultivation», which consisted of three consecutive stages: heterotrophic cultivation, culture dilution, and transfer to a daylight environment for photoinduction. In our experiment, the photoautotrophic growth of Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 changed to heterotrophic under aphotic conditions. As a result, the growth and division of Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 cells continued for 96 h of observation during cultivation under aphotic conditions. The amount of biomass in the culture increased by 17% in both light and dark conditions. This indicated the successful switching of the strain from autotrophy to heterotrophy without loss of biomass productivity. For the cultivation of the Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 strain, we used the BBM mineral medium; accordingly, heterotrophic growth occurred due to extracellular organic compounds that Chlorella cells excreted into the nutrient medium during photoautotrophic growth. Barboríková et al. [37] previously reported that microalgae, including Chlorella, excrete a considerable amount of various organic compounds into the nutrient medium during cultivation. According to the same work by Barborikova et al. [37], these organic compounds of the Chlorella vulgaris P13/199 strain consist mainly of extracellular polysaccharides (EPSs) and a small amount of protein (7.8% by weight). The analysis showed that EPS contains monosaccharides such as galactose (36.5 wt%), arabinose (27.6 wt%), rhamnose (14.7 wt%), mannose (7.4 wt%), glucose (5.7 wt%), xylose (3.0 wt%), methylated derivatives of these monosaccharides, and hexose derivatives of unknown configuration [37]. Liu and co-authors [38] noted that biotechnological industries usually use cellular biomass but do not use large residual volumes of nutrient medium with high concentrations of various biologically active compounds. And, typically, biotechnological industries dump this residual medium into the environment. Such use of biomass is not rational and requires the development of technologies that allow the use of extracellular metabolites for the production of various valuable products. The alternation of photoautotrophic and heterotrophic cultivation used in our experiment is a promising strategy for extracting extracellular metabolites from the culture medium while saving on lighting costs.

It is known that manipulating the duration of periods of illumination (photoperiod) and darkness is a well-known strategy for changing the growth of microalgae and the production of valuable compounds [39]. The traditional approach is based on varying the periods of light and dark within a 24 h range (24:0 h; 18:6 h; 16:8 h; 12:12 h (light/dark)). A modification of this strategy is the use of pulsed light or flashing lighting. In pulsed light, the duration of the light/dark periods is microseconds (µs). It is evident that periodic illumination of microalgae cultures in the time range of the traditional scheme, and pulsed illumination even more so, does not trigger the switching of autotrophy to heterotrophy and vice versa in cells. Future research will enable the description of critical points in such switching and the mechanisms underlying these processes.

Researchers typically estimate the sequestration effect in the photoautotrophic cultivation of microalgae based on the increase in biomass and carbon content within microalgae cells [19,22]. Methodological approaches to directly determining CO2 uptake by microalgae cells have not yet been fully resolved [30]. Therefore, current studies demonstrate a high variability of this indicator for different species and strains of Chlorella: from 0.149 to 0.430 mg L−1 d−1, for example, according to Jain et al. [6], to 0.02–0.14 g L−1 d−1 in the experiments of Hariz et al. [40]. In our experiment, the CO2 fixation rate for Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 was at the level of 0.0235 g CO2 L−1 day−1 both during cultivation in the light and in the dark. Thus, the sequestration effect of Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 was the same in cultures with photoautotrophic and photoautotrophic–heterotrophic growth. Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 successfully utilized CO2 carbon, as well as Extracellular Metabolite carbon, and possibly carbon in bicarbonate (HCO3−), carbonate (CO32−), and carbonic acid (H2CO3), which typically accumulate in the nutrient medium during photoautotrophic carbon assimilation [41]. The cells overcame the expected CO2 losses during the heterotrophic process by actively absorbing extracellular metabolites.

Thus, photoautotrophic carbon assimilation followed by heterotrophic carbon uptake may be a promising strategy for producing microalgae biomass, carbon deposition, and cost savings in lighting.

Current research has demonstrated that abiotic stresses, such as exposure to high-intensity light, nutrient restriction, changes in pH, and temperature, among others, have a significant impact on the metabolism of microalgae [42,43,44,45]. They lead to changes in the composition and quantity of metabolic products, as well as activate the cell’s antioxidant system to protect it from oxidative damage [20,23,42,44,46]. These changes, in turn, are markers of the degree of damaging effects, as well as the ability of cells to withstand stress. The results of this work indicate that the cultivation of Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 has become a trigger of oxidative stress in aphotic conditions.

During 96 h exposure of the strain under aphotic conditions, we found an increase in the concentration of TBA-reactive substances in the initial homogenate (TBARS) relative to the control group. This increase may be due to the breakdown of organic peroxides, and the decrease in Hpx content confirms this. The overall antioxidant status of Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 cells increased under aphotic conditions, and the KAAC value confirms this. This increase correlates well with a decrease in the concentration of lipid hydroperoxides. This indicates the activation of antioxidant protection components that neutralize this type of peroxide oxidation products. One such component is peroxidases. In the case of Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145, GPx-activity increased. Overbaugh and Fall [47], using the example of Astasia longa Pringsheim (=Euglena longa (Pringsheim) Marin & Melkonian) and Euglena gracilis G.A.Klebs, established specific GPx-activity relative to organic and inorganic peroxides. Accordingly, the established synchronous increase in CAT- and GPx-activity may indicate an increase in the content of hydrogen peroxide in the cell, which these enzymes neutralize [48]. At the same time, SOD-activity did not significantly differ between the experimental groups studied, although this enzyme is an indicator of the stress effects of abiotic factors [48]. It is SOD that ensures the conversion of superoxide into hydrogen peroxide and, according to Ma et al. [49], an increase in CAT-activity is possible only under conditions of effective superoxide dismutation by superoxide dismutase, which is associated with the inhibitory effect of superoxide on CAT. The high increase in CAT- and GPx-activity indicates the greatest contribution of these systems to the formation of antioxidant resistance of the strain. Portune et al. [50] confirm this in their work. They found that for marine representatives of the Raphidophyceae class, the antioxidant enzymes SOD and CAT play a crucial role in neutralizing reactive oxygen species at the stage of logarithmic growth. Since the SOD-activity of cells did not significantly differ between the groups, it is likely that most of the H2O2 generation occurs in other parts of the metabolic pathways, for example, in the Krebs cycle or the mitochondrial electron transport chain. Given this, we can assume that Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 has «identified» photoautotrophic growing conditions as preferred.

Aphotic stress most affected lipid and protein metabolism: the lipid content in the biomass of Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 increased by 68.7%, and protein decreased by 42.3% compared to similar indicators when growing in the light. An increase in lipid concentration during cultivation in the dark was also previously found for Chlorella vulgaris Beijerinck UTEX 259 and Chlorella sorokiniana Shihira & R.W.Krauss AARL G015, but under heterotrophic conditions [51,52]. At the same time, growth in the dark depletes the biomass of microalgae into compounds that are directly related to photosynthesis [32]. The results of this study show that the amount of protein decreases especially rapidly. The content of photosynthetic pigments in Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 did not significantly change after cultivation under aphotic conditions for 96 h. This indicates the high stability of the photosynthetic system of Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 to the effect of shading. In general, the effect of prolonged shading on photosynthesis remains poorly understood; however, the rapid recovery of photosynthesis after shading is well-documented [53,54]. In addition, Chlorella vulgaris cells are able to switch the type of photosynthesis depending on the spectral composition and light intensity [55].

One of the signs of stress is an increased accumulation of secondary carotenoids [42,56]. In Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145, aphotic stress during 96 h of cultivation did not cause carotenogenesis. At the same time, during the experiment, we observed a change in the content of low-molecular antioxidants, such as ascorbic acid and phenolic compounds. Growing in the dark reduced their concentration in Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145. This decrease may be related to the antioxidant properties of the compounds [57] and their ability to inactivate reactive oxygen species.

We note that the metabolic systems of the studied strain of Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 specifically respond to cultivation under aphotic conditions. We found the greatest response from the lipid–protein metabolism and the antioxidant defense system, which determines an increase in the overall antioxidant status of cells. At the same time, the productive, CO2-sequestration characteristics and pigment composition of the photosynthetic system did not change, although in the classical view, the reaction of the photosynthetic apparatus to insufficient lighting is an increase in the concentration of chlorophylls, and most stresses initiate carotenogenesis. In this regard, further study of Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 with prolonged exposure to aphotic conditions is required. This will help to understand the biochemical mechanisms behind the observed metabolic changes.

5. Conclusions

Biomass productivity of Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 exhibited the same behavior during photoautotrophic growth and in a two-step culture, where there was a sequential transition from photoautotrophic cultivation to growth in the dark. Photoautotrophic carbon assimilation, at the first step of cultivation, switched to heterotrophic carbon uptake at the aphotic stage due to the active uptake of extracellular metabolites.

Aphotic stress resulted in a 68.7% increase in lipid content in the biomass and a 42.3% decrease in protein compared to similar indicators in Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 when growing in the light. The content of photosynthetic pigments did not exhibit significant changes.

Antioxidant status of Chlorella sp. CAMU G–145 was higher under aphotic stress than in cultures with photoautotrophic growth. The concentration of low-molecular-weight antioxidants (ascorbic acid, phenolic compounds) decreased. In contrast, the activity of antioxidant enzymes and the concentration of lipid degradation products increased in cells under aphotic stress.

In general, the photoautotrophic growth of Chlorella sp. culture. CAMU G–145, followed by heterotrophic carbon uptake during aphotic stress, may be a promising strategy for producing microalgae biomass and inducing lipid synthesis. This strategy enables carbon deposition, including through the active absorption of extracellular metabolites, and reduces lighting costs. This helps to increase the efficiency of biotechnological production.

Author Contributions

A.Y.: supervision, biochemical analysis. I.M.: conceptualization, data curation, writing—original draft. A.K.: methodology and formal analysis. Y.M.: conceptualization, writing—original draft. E.L.: investigation, visualization. E.S.: formal analysis, performed experiments. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication is based on research carried out with financial support from the Russian Science Foundation (project number 24-74-00132, https://rscf.ru/project/24-74-00132/, accessed on 1 November 2025); the percentage contribution is 80%. The determination of carbon dioxide biofixation was maintained under the theme “Sequestration potential of microalgae and cyanobacteria of anthropogenically transformed ecosystems of the Zaporozhye region under conditions of increasing climate aridization” (FRRS-2024-0003; No 124040100028-6); the percentage contribution was 10%. The isolation of the algal strain and the manuscript design were performed within the state assignment of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (theme 124052200012-7 No. FFES-2024-0001); the percentage contribution was 10%.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sathasivam, R.; Radhakrishnan, R.; Hashem, A.; Abd_Allah, E.F. Microalgae metabolites: A rich source for food and medicine. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, P.; Kumar, R.; Neha, Y.; Srivatsan, V. Microalgae as next generation plant growth additives: Functions, applications, challenges and circular bioeconomy-based solutions. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1073546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, N.; Sarwar, Z.; Abideen, Z.; Saleem, F.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Siddiqui, Z.S.; El-Keblawy, A. Algae-based bioremediation of soil, water, and air: A solution to polluted environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 21338–21357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Jayant, K.; Mehra, A.; Bhutani, S.; Kaur, T.; Kour, D.; Suyal, D.C.; Singh, S.; Rai, A.K.; Yadav, A.N. Bioremediation—Sustainable tool for diverse contaminants management: Current scenario and future aspects. J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Sharma, R.; Pant, D.; Malaviya, P. Engineered algal biochar for contaminant remediation and electrochemical applications. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 774, 145676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, D.; Ghonse, S.S.; Trivedi, T.; Fernandes, G.L.; Menezes, L.D.; Damare, S.R.; Mamatha, S.S.; Kumar, S.; Gupta, V. CO2 fixation and production of biodiesel by Chlorella vulgaris NIOCCV under mixotrophic cultivation. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 273, 672–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassey, V.E.J.; Walcker, R.; Kardol, P.; Geisen, S.; Heger, T.; Lamentowicz, M.; Hamard, S.; Lara, E. Contribution of soil algae to the global carbon cycle. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwer, A.; Hamed, S.M.; Osman, A.I.; Jamil, F.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.H.; Alhajeri, N.S.; Rooney, D.W. Algal biomass valorization for biofuel production and carbon sequestration: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 2797–2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafa, N.; Ahmed, S.F.; Badruddin, I.A.; Mofijur, M.; Kamangar, S. Strategies to produce cost-effective third-generation biofuel from microalgae. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 749968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratomski, P.; Hawrot-Paw, M. Influence of nutrient-stress conditions on Chlorella vulgaris biomass production and lipid content. Catalysts 2021, 11, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.-M.; Ren, L.-J.; Zhao, Q.-Y.; Ji, X.-J.; Huang, H. Enhancement of lipid accumulation in microalgae by metabolic engineering. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)–Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2019, 1864, 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, I.T.K.; Sung, Y.Y.; Jusoh, M.; Wahid, M.E.A.; Nagappan, T. Chlorella vulgaris: A perspective on its potential for combining high biomass with high value bioproducts. Appl. Phycol. 2020, 1, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, M.F.; Kokabian, B.; Gude, V.G. Light and growth medium effect on Chlorella vulgaris biomass production. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheirsilp, B.; Torpee, S. Enhanced growth and lipid production of microalgae under mixotrophic culture condition: Effect of light intensity, glucose concentration and fed-batch cultivation. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 110, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y. Growth medium screening for Chlorella vulgaris growth and lipid production. J. Adv. Microbiol. 2017, 6, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayatollahi, S.Z.; Esmaeilzadeh, F.; Mowla, D. Integrated CO2 capture, nutrients removal and biodiesel production using Chlorella vulgaris. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 104763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhou, J.; Liu, G.; Gui, B. Selection of microalgae for high CO2 fixation efficiency and lipid accumulation from ten Chlorella strains using municipal wastewater. J. Environ. Sci. 2016, 46, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.; Najafpour, G.D.; Mohammadi, M.; Seifi, M.H. Cultivation of newly isolated microalgae Coelastrum sp. in wastewater for simultaneous CO2 fixation, lipid production and wastewater treatment. Bioprocess. Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 41, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltsev, Y.; Gusev, E.; Maltseva, I.; Kulikovskiy, M.; Namsaraev, Z.; Petrushkina, M.; Filimonova, A.; Sorokin, B.; Golubeva, A.; Butaeva, G.; et al. Description of a new species of soil algae, Parietochloris grandis sp. nov., and study of its fatty acid profiles under different culturing conditions. Algal Res. 2018, 33, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakoviichuk, A.; Krivova, Z.; Maltseva, S.; Kochubey, A.; Kulikovskiy, M.; Maltsev, Y. Antioxidant status and biotechnological potential of new Vischeria vischeri (Eustigmatophyceae) soil strains in enrichment cultures. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Morais, M.G.; Costa, J.A.V. Carbon dioxide fixation by Chlorella kessleri, C. vulgaris, Scenedesmus obliquus and Spirulina sp. cultivated in flasks and vertical tubular photobioreactors. Biotechnol. Lett. 2007, 29, 1349–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Roy, A.S.; Mohanty, K.; Ghoshal, A.K. Enhanced CO2 sequestration by a novel microalga: Scenedesmus obliquus SA1 isolated from bio-diversity hotspot region of Assam, India. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 143, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakoviichuk, A.V.; Kochubey, A.V.; Maltseva, I.; Matsyura, A.; Cherkashina, S.V.; Lysova, E.A. Biochemical and antioxidant characteristics of the soil strain Chlorococcum oleofaciens (Chlorophyceae, Chlorophyta) grown in light, dark and bicarbonate conditions. Acta Biol. Sib. 2025, 11, 411–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, T.A.; Hadwan, M.H. New spectrophotometric method for the assessment of catalase enzyme activity in biological tissues. Curr. Anal. Chem. 2020, 16, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, A.A.; Matin, A.A.; Hadwan, M.H.; Hadwan, A.M.; Mohammed, R.M. Rapid and effective protocol to measure glutathione peroxidase activity. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2024, 48, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirota, T.V. Use of nitro blue tetrazolium in the reaction of adrenaline autooxidation for the determination of superoxide dismutase activity. Biochem. Suppl. Ser. B Biomed. Chem. 2012, 6, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, G.P.; Keough, M.J. Experimental Design and Data Analysis for Biologists, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; ISBN 978-1-139-56817-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butti, S.K.; Venkata Mohan, S. Photosynthetic and lipogenic response under elevated CO2 and H2 conditions—High carbon uptake and fatty acids unsaturation. Front. Energy Res. 2018, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liyanaarachchi, V.C.; Nishshanka, G.K.S.H.; Premaratne, R.G.M.M.; Ariyadasa, T.U.; Nimarshana, P.H.V.; Malik, A. Astaxanthin accumulation in the green microalga Haematococcus pluvialis: Effect of initial phosphate concentration and stepwise/continuous light stress. Biotechnol. Rep. 2020, 28, e00538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, W.; Kong, J.; Ma, J.; Lyu, H.; Feng, S.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, P.; Shen, B. Chlorella vulgaris cultivation in simulated wastewater for the biomass production, nutrients removal and CO2 fixation simultaneously. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 284, 112070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, H.-S.; Kim, Y.-S.; Yoon, H.-S. Effect of different cultivation modes (photoautotrophic, mixotrophic, and heterotrophic) on the growth of Chlorella sp. and biocompositions. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 774143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Wang, K.; Gao, F.; Ge, B.; Cui, H.; Li, W. Biotechnologies for bulk production of microalgal biomass: From mass cultivation to dried biomass acquisition. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2023, 16, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Occhipinti, P.S.; Del Signore, F.; Canziani, S.; Caggia, C.; Mezzanotte, V.; Ferrer-Ledo, N. Mixotrophic and heterotrophic growth of Galdieria sulphuraria using buttermilk as a carbon source. J. Appl. Phycol. 2023, 35, 2631–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleissner, D.; Lindner, A.V.; Ambati, R.R. Techniques to control microbial contaminants in nonsterile microalgae cultivation. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 192, 1376–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; He, X.; Ma, Q.; Lu, Y.; Bai, F.; Dai, J.; Wu, Q. Photosynthetic accumulation of lutein in Auxenochlorella protothecoides after heterotrophic growth. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Huang, J.; Li, Y.; Han, F.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Li, S. Sequential heterotrophy–dilution–photoinduction cultivation for efficient microalgal biomass and lipid production. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 112, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barboríková, J.; Šutovská, M.; Kazimierová, I.; Jošková, M.; Fraňová, S.; Kopecký, J.; Capek, P. Extracellular polysaccharide produced by Chlorella vulgaris—Chemical characterization and anti-asthmatic profile. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 135, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Pohnert, G.; Wei, D. Extracellular metabolites from industrial microalgae and their biotechnological potential. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltsev, Y.; Maltseva, K.; Kulikovskiy, M.; Maltseva, S. Influence of light conditions on microalgae growth and content of lipids, carotenoids, and fatty acid composition. Biology 2021, 10, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariz, H.B.; Takriff, M.S.; Ba-Abbad, M.M.; Mohd Yasin, N.H.; Mohd Hakim, N.I.N. CO2 fixation capability of Chlorella sp. and its use in treating agricultural wastewater. J. Appl. Phycol. 2018, 30, 3017–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beardall, J.; Raven, J.A. Carbon acquisition by microalgae. In The Physiology of Microalgae; Borowitzka, M.A., Beardall, J., Raven, J.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 89–99. ISBN 978-3-319-24943-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltseva, I.; Yakoviichuk, A.; Maltseva, S.; Cherkashina, S.; Kulikovskiy, M.; Maltsev, Y. Biochemical and antioxidant characteristics of Chlorococcum oleofaciens (Chlorophyceae, Chlorophyta) under various cultivation conditions. Plants 2024, 13, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltseva, S.Y.; Kulikovskiy, M.S.; Maltsev, Y.I. Functional state of Coelastrella multistriata (Sphaeropleales, Chlorophyta) in an enrichment culture. Microbiology 2022, 91, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliwal, C.; Mitra, M.; Bhayani, K.; Bharadwaj, S.V.V.; Ghosh, T.; Dubey, S.; Mishra, S. Abiotic stresses as tools for metabolites in microalgae. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 244, 1216–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Zhu, R.; Lu, J.; Lei, A.; Zhu, H.; Hu, Z.; Wang, J. Effects of different abiotic stresses on carotenoid and fatty acid metabolism in the green microalga Dunaliella salina Y6. Ann. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Cai, Y.; Wakisaka, M.; Yang, Z.; Yin, Y.; Fang, W.; Xu, Y.; Omura, T.; Yu, R.; Zheng, A.L.T. Mitigation of oxidative stress damage caused by abiotic stress to improve biomass yield of microalgae: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 896, 165200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overbaugh, J.M.; Fall, R. Detection of glutathione peroxidases in some microalgae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1982, 13, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezayian, M.; Niknam, V.; Ebrahimzadeh, H. Oxidative damage and antioxidative system in algae. Toxicol. Rep. 2019, 6, 1309–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Deng, D.; Chen, W. Inhibitors and activators of SOD, GSH-Px, and CAT. In Enzyme Inhibitors and Activators; Senturk, M., Ed.; InTech: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-953-51-3057-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portune, K.J.; Craig Cary, S.; Warner, M.E. Antioxidant enzyme response and reactive oxygen species production in marine Raphidophytes. J. Phycol. 2010, 46, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jareonsin, S.; Mahanil, K.; Phinyo, K.; Srinuanpan, S.; Pekkoh, J.; Kameya, M.; Arai, H.; Ishii, M.; Chundet, R.; Sattayawat, P.; et al. Unlocking microalgal host—exploring dark-growing microalgae transformation for sustainable high-value phytochemical production. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1296216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Sarkany, N.; Cui, Y. Biomass and lipid productivities of Chlorella vulgaris under autotrophic, heterotrophic and mixotrophic growth conditions. Biotechnol. Lett. 2009, 31, 1043–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, D.W.; Lewis, L.A.; Cardon, Z.G. Photosynthetic recovery following desiccation of desert green algae (Chlorophyta) and their aquatic relatives. Plant Cell Environ. 2007, 30, 1240–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, B.; Peters, J.; Van Beusekom, J.E.E. The effect of constant darkness and short light periods on the survival and physiological fitness of two phytoplankton species and their growth potential after re-illumination. Aquat. Ecol. 2017, 51, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysenko, V.; Kosolapov, A.; Usova, E.; Tatosyan, M.; Varduny, T.; Dmitriev, P.; Rajput, V.; Krasnov, V.; Kunitsina, A. Chlorophyll fluorescence kinetics and oxygen evolution in Chlorella vulgaris Cells: Blue vs. red light. J. Plant Physiol. 2021, 258–259, 153392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chini Zittelli, G.; Lauceri, R.; Faraloni, C.; Silva Benavides, A.M.; Torzillo, G. Valuable pigments from microalgae: Phycobiliproteins, primary carotenoids, and fucoxanthin. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2023, 22, 1733–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coulombier, N.; Jauffrais, T.; Lebouvier, N. Antioxidant compounds from microalgae: A review. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).