Abstract

Purpose: Cross-sectional analysis using open data has revealed an association between the traditional Japanese diet score (TJDS) and healthy life expectancy (HALE). This study aimed to clarify the association of the TJDS with the HALE and average life expectancy (LE) via a longitudinal analysis. Methods: Data regarding the food supply and total energy were extracted from the database of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, and data regarding HALE and LE were obtained from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The supply of items consumed frequently (rice, fish, soybeans, vegetables, and eggs) and less frequently (wheat, milk, and red meat) in the Japanese diet were scored (total: −8 to 8 points) and stratified into tertiles by country. The gross domestic product, aging rates, years of education, smoking rate, physical activity, and obesity rate were used as covariates. Longitudinal analyses were conducted for 143 countries, using the HALE and LE for each country from 2010 to 2019 as dependent variables and the 2010 TJDS as an independent variable. Results: The fixed effects (standard errors) were HALE 0.424 (0.102) and LE 0.521 (0.119), indicating significance (p < 0.001). Conclusion: The nine-year longitudinal analysis using international data suggests that the traditional Japanese diet based on rice may prolong the HALE and LE.

1. Introduction

Japanese food was registered as an intangible cultural heritage by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 2012 [1]. The Minister’s Award, which honors individuals who have made outstanding contributions to introducing and spreading Japanese cuisine and its agricultural and marine products to the rest of the world, was established by the Japanese government to promote the Japanese diet. Interest in traditional Japanese food has been increasing worldwide, for several reasons [2]. One of them is the nutritional balance it ensures, supporting a healthy diet, which was one of the key factors for its registration as a UNESCO intangible cultural heritage [1].

Japan achieved the world’s longest record in healthy life expectancy (HALE) and average life expectancy (LE) in 2013, and these parameters have continued to increase [3]. The Japanese diet has become richer and more diverse after periods of high economic growth, and this has contributed to the HALE and LE [4]. Studies using nationwide Japanese cohort data have shown that dietary patterns with higher intakes of fruits, vegetables, fish, and dietary fiber; lower intakes of salt; and a low sodium-to-potassium ratio; are associated with a lower risk of Cardiovascular Diseases (CVD) mortality [5]. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the Japanese population revealed that the Japanese-style diet and characteristic Japanese foods may reduce the mortality associated with CVD [6] and that increased consumption of vegetables, fruits, fish, green tea, milk, and dairy products decrease the risk ratio for CVD, stroke, and heart disease mortality.

The systematic reviews of the Japanese-style diet and the mortality associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) only included Japan in the analysis [6]. Indicators of the health advantages of the Japanese diet have not been established on a global scale. Notably, studies examining the superiority of Japanese-style diets have been limited to cohort studies that utilized scores created via statistical methods, such as factor analysis [7,8], or studies that scored each unique category of the Japanese diet, such as staple foods, main dishes, and side dishes [9,10,11]. In China and South Korea, where rice is also a staple food, diet scores have been developed based on their respective national dietary guidelines [12,13,14,15]. This scoring methodology follows the healthy eating index (HEI) in the United States, and the final scores are country-specific. However, these developed HEI is not universally applicable to regions where rice is the staple food. There is a lack of research on dietary scores representing Asian diets, which are based on rice consumption, as well as on dietary scores representing healthy diets in other regions [16].

Many studies have evaluated dietary patterns, such as the Mediterranean diet [17,18,19,20] and the HEI, that have significant effects on health [21,22,23]. Moreover, some studies have also evaluated the superiority of several food patterns [23,24,25]. Organizations, such as the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Statistics Division database (FAOSTAT) and the Global Burden of Disease (GBD), have started providing open data in recent years, resulting in an increase in the number of international ecological evaluations of the relationship between diet and health events [26,27,28]. The studies using these open data have revealed associations between national and regional health characteristics and status. Although FAOSTAT data represents the food supply, which has inherent limitations, these data can be utilized to estimate country-level food intake [29,30]. Further ecological studies using open data may benefit policy-making [31]. Therefore, we developed the TJDS and examined its association with health outcomes using FAOSTAT data. Our previous study, an ecological study conducted using international open data, indicated that food diversity shows positive associations with the HALE and LE [32]. The traditional Japanese diet score (TJDS) was created in this cross-sectional study, and open data were used to examine the association between TJDS and obesity, HALE, and ischemic heart disease (IHD) [33]. Evaluating the advantages of consuming a Japanese-style diet revealed that the TJDS showed associations with breast cancer [34], all-cause mortality [35], suicide [36], and SDGs [37]. However, this study was cross-sectional; consequently, the longitudinal association between the TJDS and the HALE could not be examined. The purpose of this study was to verify the association between the TJDS, HALE, and LE, using a longitudinal analysis that provides a higher level of evidence.

2. Methods

2.1. Variables

Food: The FAOSTAT provides food and agriculture data encompassing all Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) regional groupings [38]. The food supply data from 2010 to 2019 were used in this study, and duplicate food items were excluded. The average food supply per capita per day (kg/capita/day) and energy supply (1000 kcal/person/day) by country were obtained, excluding the losses between production and households.

Traditional Japanese diet score: the TJDS was created using the Mediterranean diet score, a diet score created by Trichopoulou et al. [39] that has been used widely, as the reference. The details are as previously reported, but we selected food groups from FAOSTAT that are supplied more in Japan, less supplied, and those considered as important of the dietary pattern. From these, we ultimately chose the food groups that could structure a scoring system capable of expressing the features of the Japanese diet, where rice is the staple food. Eight food components characteristic of the traditional Japanese diet, were selected from the database. Calculations were performed for the supply amount per 1000 kcal. The highest, second highest, and lowest tertiles for the supply of beneficial food components of the traditional Japanese diet (rice, fish, soybeans, vegetables, and eggs) were assigned values of 1, 0, and −1, respectively. Components that are not commonly used in the Japanese diet (wheat, milk, and red meat) were scored in the opposite direction (1, 0, and −1). The total score ranged from −8 to 8, with higher scores indicating higher adherence to the traditional Japanese diet.

HALE and LE: The GBD 2019 is the most comprehensive source of the burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors, including the HALE and LE, on global, regional, and national scales [40]. The Sullivan method, which draws on age-specific death rates and years of life lived with disability per capita, was used to estimate the HALE [41].

Covariables: We acquired the following data as co-variates available from reliable open data sources and included them as adjustment variables. The age-standardized education years (education), current smoking rate (smoking), activity (MetS/week), and obesity rate (%), which were obtained from the GBD database, were used as open data covariables [40]. Data regarding the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita (1000 USD/person), total population in millions (population), and percentage of the population aged > 65 years (aging rate) were obtained from the World Bank database [42]. Data for the period between 2010 and 2019 were extracted. All data were downloaded from the official website and structured into the analysis dataset. The created dataset is hosted on a cloud server and managed with a password, and access is limited to collaborative researchers. The analysis data contained no missing data.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

A total of 143 countries with populations of >1 million with available data were included in the analysis. The longitudinal associations between the HALE and LE from 2010 to 2019 were examined using the 2010 TJDS as the baseline. The TJDS, food groups constituting the TJDS, HALE, LE, and the lifestyle and socioeconomic variables in 2010 are presented as percentiles. The associations of the TJDS with the HALE and LE at baseline (2010) were evaluated using a general linear regression model. The dependent and independent variables were mean-centered to prevent multicollinearity between the covariates. A model adjusted for GDP, aging, education, energy supply, smoking, activity, and obesity was selected, and the coefficient of determination (R2) was obtained.

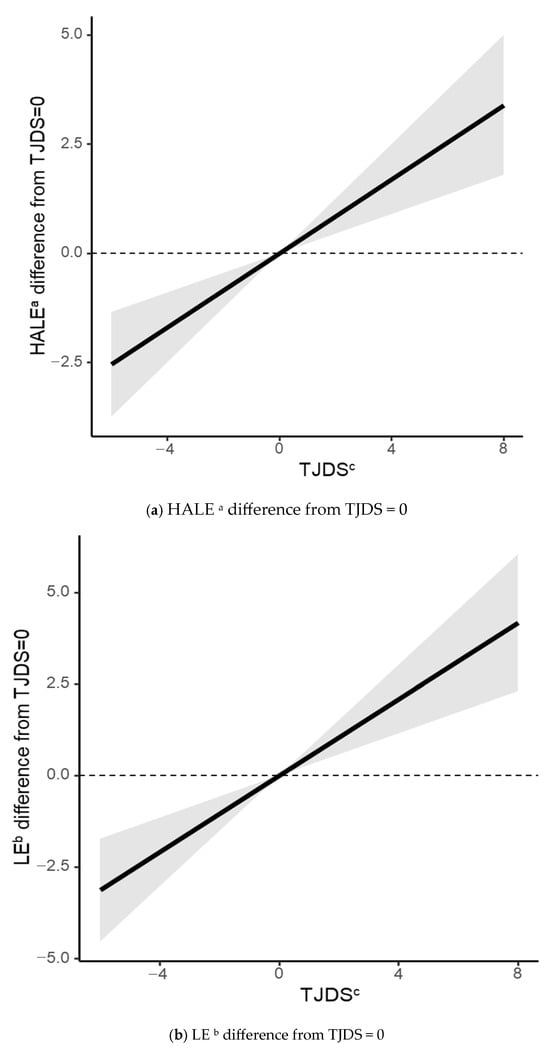

A longitudinal analysis was conducted using a linear mixed model with the HALE and LE for each country from 2010 to 2019 as dependent variables and the 2010 TJDS as an independent variable. The dependent variable and covariates were centered and adjusted for the 2010 covariates. The random effects in the model included country-specific intercepts and year-specific slopes. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.3.1 [43]. The generalized linear mixed model was fitted using the ‘lme’ function of the ‘nlme’ package [44]. The statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The changes in the slope of the TJDS to the HALE or LE and differences in the HALE or LE from the TJDS scored zero are shown in the figures.

3. Results

Table 1 presents the TJDS, food groups constituting the TJDS, HALE, LE, lifestyle, and socioeconomic characteristics in 2010. The mean, SD, and median values were as follows: TJDS, −0.4, 2.8, and 0.0; HALE, 61.2, 7.7, and 63.4; and LE, 70.2, 9.2, and 71.9, respectively. The highest TJDS was six points for Malaysia; five points for six countries, including Indonesia, Thailand, and China; and four points for Japan. The rankings of the Japanese food groups that contributed to the score were; rice at twenty-fifth (58.3 g/day), fish at second (38.0 g/day), soybeans at first (5.5 g/day), and eggs at second (27.2 g/day), all belonging to the highest tertile. Conversely, vegetables were ranked 83rd (13.1 g/day), wheat 87th (32.7 g/day), dairy products 82nd (67.6 g/day), and meat 60th (21.9 g/day), all belonging to the second tertile (Supplementary Table S1). The results for 2019 are almost the same as those for 2010. (Supplementary Table S2). The HALE and LE, at 72.7 and 83.3 years, respectively, were the highest in Japan. The regional annual changes in the TJDS, HALE, and LE from 2010 to 2019 are shown in the Supplementary Data (Supplementary Figure S1). The annual changes were consistent across all regions, respectively.

Table 1.

The characteristics of TJDS a, HALE b, LE c, life style, and socioeconomic variables in 2010.

Table 2 presents the results of the cross-sectional analysis of the association of the TJDS with the HALE and LE using 2010 data, revealing that the fixed effects (standard errors) were significant (p < 0.001) in the model adjusted for all covariates: HALE, 0.571 (0.163), and LE, 0.674 (0.190). The R2 values for the HALE and LE were 0.634 and 0.646, respectively.

Table 2.

Cross-sectional analysis of the association of TJDS a with HALE b and LE c using 2010 data.

Table 3 presents the results of the longitudinal analyses. The fixed effects (standard errors) of the longitudinal analysis of the association of the TJDS with the HALE and LE in the model adjusted for all covariates (p < 0.001) were as follows: HALE, 0.424 (0.102), and LE, 0.521 (0.119). The R2 values for HALE and LE were 0.506 and 0.546, respectively. When the interaction between the TJDS and year was included in the analysis, the interaction term was not statistically significant, and the association between the TJDS and the HALE or LE (Supplementary Table S3).

Table 3.

Longitudinal analysis of the association of TJDS a with HALE b and LE c using data from 2010 to 2019.

Figure 1 shows the estimated HALE, LE, and differences in HALE and LE from the TJDS scored zero according to the TJDS. The HALE and LE positive associations with the TJDS. The HALE and LE were about 2.5 and 3 years longer, respectively, when the TJDS was eight points compared with those when the TJDS was zero points. The HALE and LE were about 2.5 years shorter when TJDS was −4 points.

Figure 1.

HALE a differences from Traditional Japanese Dietary Score (TJDS) = 0 (a) and LE b differences from TJDS = 0 (b) by TJDS c using a linear mixed model controlling for covariates. Gray area represented 95% confidence interval. a, Healthy Life Expectancy. b, Average life expectancy. c, Traditional Japanese Diet Score.

4. Discussion

4.1. Association of the TJDS with the HALE and LE Based on Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Analyses

Evaluation of the association of the TJDS with the HALE and LE using international open data from 2010 to 2019 revealed that the TJDS showed significant positive associations with the HALE and LE in the cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. The R2 value was lower in the longitudinal analysis. However, the difference was small. The interaction between the TJDS and year was not significant, indicating that the association between the TJDS and HALE or LE did not change between 2010 and 2019. Previous studies demonstrating a positive association between the TJDS and HALE used FAOSTAT 2013 and GBD 2015 [33]. Diets are expected to change over time [5]. However, according to the FAOSTAT 2010–2019 data, only small changes in dietary patterns were observed across countries, and the impact of changes in dietary patterns may be small on a country-by-country basis. The advantages of the Japanese diet for health outcomes observed in the present study are consistent with the findings of other studies [3,4,5,8,9,10,11,32] and our previous studies [32,33,34,35,36]. The FAOSTAT collects food supply data for countries worldwide in accordance with FAO standards, ensuring the collection of high-quality data. Several publications have examined the association between the FAOSTAT food supply and health outcomes [29,45,46]. Some research has suggested a discrepancy between the food supply and actual consumption [47], though, it may not significantly affect the ranking of a country. As a precaution, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using food waste rate data by country and the food group from Chen et al. [48], defining the food intake amount as the food supply minus the food wastes. The results showed no substantial difference, and the level of significance also remained unchanged. (Supplementary Tables S4–S6). Furthermore, utilizing open data, we compared Japan’s FAOSTAT food supply amount with the intake amount reported in the National Health and Nutrition Survey (NHNS) [49]. This comparison indicated that the influence of the difference between the Japanese FAOSTAT supply amount and the NHNS intake amount per 1000 kcal was not statistically significant.

4.2. Temporal Changes in the TJDS, HALE, and LE

However, this score does not represent the current Japanese diet, which has become more Westernized in recent years, resulting in an increased intake of wheat and meat. Nevertheless, Japan remains in the second quartile in the world regarding the supply of these food groups. According to a study analyzing the Global Dietary Database from 1990 to 2018, people’s diets have not changed over 30 years. [28]. Similarly to Japan, the Westernization of diets is progressing globally, and international analyses suggest there is little change over time. Moderate meat intake may be effective in extending the HALE and LE [50]. Measures to facilitate the adequate intake of one of the food groups in the minimum tertile, for instance, meat, might extend the HALE and LE. Our analysis revealed that a TJDS score of eight points may extend the HALE and LE by 3 and 2.5 years, respectively, compared with that at a score of zero. Thus, it may be necessary to suggest a suitable intake of the food groups that make up the TJDS, such as the HEI derived from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) [51].

4.3. The Utility of TJDS

The HALE and LE in Japan rank first in the world. Preventing obesity and the spread of non-communicable diseases that lead to premature death aids in prolonging the HALE; similarly, diet is highly involved [3]. However, it is clear that a well-balanced diet, such as the Mediterranean diet and HEI, can prolong the HALE. The TJDS, which includes food groups common to these scores, also revealed an increase in the HALE and LE. Thus, the Japanese diet is also likely to lengthen the HALE, and the TJDS can be used globally to score for Japanese diets. In Western countries, carbohydrates are primarily consumed as wheat, which is why wheat is the central grain in diet scores, including the Mediterranean Diet Score (MDS) and the HEI. However, in paddy field areas such as Japan, rice is the main staple grain. Similarly to Japan, South Korea and China, which also base their diets on rice, have created dietary scores based on their national dietary guidelines and data from their national health and nutrition surveys, utilizing a similar concept to the HEI [13,14]. Consequently, the scoring criteria include components such as saturated fatty acids, sodium, and added sugars, requiring detailed nutrient intake data for calculation. Unlike the TJDS, which can be easily calculated from food group consumption, these scores cannot be simply derived, and none of them were created for international use. Therefore, the TJDS has the potential for global application as a score for evaluating Japanese and other rice-based diets. It will be necessary to conduct research comparing the TJDS’s health-contributing effects with those of the MDS, HEI, and other dietary scores to confirm its superiority as a dietary score.

This study had some limitations. First, national panel data were used in this study, and it was not possible to analyze the data according to sex or age. Moreover, it is un-clear whether the findings of this study are applicable to individuals. It will be necessary to confirm whether the TJDS can be utilized using cohort data. Second, the TJDS was calculated based on the average food supply data. Comparison of the differences between food supply and consumption [49] revealed that the impact of the difference between food supply and consumption per 1000 kcal was not significant, though it was limited to Japanese data. Third, the TJDS does not indicate the quantitative adequacy of each food group. Further studies must be conducted to evaluate the quantitative adequacy of food. However, given the existence of several studies [29,45,46], it might be possible to examine food consumption in various countries using the FAOSTAT. Fourth, since this study collected data from reliable open data sources, it is possible that necessary confounding factors for the analysis were absent.

The present study provided the first evidence that the TDJS shows significant positive correlations with the HALE and LE using longitudinal global international data over nine years. Thus, the rice-based Japanese diet may prolong the HALE and LE.

5. Conclusions

The TJDS and the findings of the nine-year longitudinal analysis using international data suggest that the rice-based traditional Japanese diet may prolong the HALE and LE.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jal6010003/s1, Table S1: Supplemental Table S1. Rankings and values of TJDS, foodgroups constituting the TJDS, HALE, and LE for each country (2010); Table S2: Supplemental Table S2. Rankings and values of TJDS, foodgroups constituting the TJDS, HALE, and LE for each country (2019); Figure S1: Supplemental Figure S1. The regional annual changes in TJDS, HALE, and LE from 2010 to 2019; Table S3: Supplemental Table S3. Longitudinal analysis of the association of TJDS a with HALE b and LE c using data from 2010 to 2019; Table S4: Supplemental Table S4. The characteristics of TJDS a, HALE b, LE c, life style, and socioeconomic variables in 2019; Table S5: Supplemental Table S5. Cross-sectional analysis of the association of TJDS a with HALE b and LE c using 2010 data; Table S6: Supplemental Table S6. Longitudinal analysis of the association of TJDS a with HALE b and LE c using data from 2010 to 2019.

Author Contributions

T.I. organized the data, devised the study design, performed data analysis, interpreted the results, drafted the initial manuscript, and was primarily responsible for the final content; C.A. collected the data, devised the study design, interpreted the results, and contributed to the discussion; A.S., K.M., F.K., Y.S. (Yoshiro Shirai), M.S., A.I., N.S., T.H., Y.S. (Yuta Sumikama) and S.N. interpreted the results and contributed to the discussion; and H.S. was the senior author, supervised the study, collected data, devised the study design, interpreted the results, and contributed to the discussion. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the 2023 DWCLA on-campus research grant (Individual and Encouragement).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Because of the use of open data, this study design did not require approval from an ethics review board.

Informed Consent Statement

We used country-level open data that is publicly available, such as the FAOSTAT.

Data Availability Statement

The data associated with this study are available from the organizations listed in the text or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Yoshiro Shirai was employed by the company Digital Therapeutics and Business Implementation Group, Life Science Laboratories, Co-creation Division, KDDi Re-search, Inc., Tokyo, Japan. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

TJDS: Traditional Japanese diet score; HALE: Healthy life expectancy; LE: Average life expectancy; FAOSTAT: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Statistics Division; GBD: Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study; GDP: Gross domestic product; UNESCO: United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization; HEI: Hearty eating index; CVD: Cardiovascular diseases; IHD: Ischemic heart disease; SDGs: Sustainable development goals; FAO: The Food and Agriculture Organization; Education: Age-standardized education years; Smoking: Current smoking rate; Population: Total population in millions; Aging rate: Population over 65 years old; R2: the Coefficient of determination; SD: Standard deviation; NHANES: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

References

- Government of Japan. Tokyo WASHOKU Traditional Dietary Cultures of the Japanese. 2024. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/e/data/publish/attach/pdf/index-20.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. The Winners of the Minister′s Awards for Overseas Promotion of Japanese Food. 2024. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/e/policies/market/award/index.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Tokudome, S.; Hashimoto, S.; Igata, A. Life expectancy and healthy life expectancy of Japan: The fastest graying society in the world. BMC Res. Notes 2016, 9, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katanoda, K.; Kim, H.S.; Matsumura, Y. New Quantitative Index for Dietary Diversity (QUANTIDD) and its annual changes in the Japanese. Nutrition 2006, 22, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, K.; Miura, K.; Okamura, T.; Okayama, A.; Ueshima, H. Dietary Factors, Dietary Patterns, and Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Representative Japanese Cohorts: NIPPON DATA80/90. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2023, 30, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirota, M.; Watanabe, N.; Suzuki, M.; Kobori, M. Japanese-Style Diet and Cardiovascular Disease Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuyama, S.; Sawada, N.; Tomata, Y.; Zhang, S.; Goto, A.; Yamaji, T.; Iwasaki, M.; Inoue, M.; Tsuji, I.; Tsugane, S.; et al. Association between adherence to the Japanese diet and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: The Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 1327–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, S.; Zhang, S.; Tomata, Y.; Tsuduki, T.; Sugawara, Y.; Tsuji, I. Japanese diet and survival time: The Ohsaki Cohort 1994 study. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurotani, K.; Akter, S.; Kashino, I.; Goto, A.; Mizoue, T.; Noda, M.; Sasazuki, S.; Sawada, N.; Tsugane, S. Japan Public Health Center based Prospective Study Group. Quality of diet and mortality among Japanese men and women: Japan Public Health Center based prospective study. BMJ 2016, 352, i1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, E.; Nakamura, K.; Ukawa, S.; Wakai, K.; Date, C.; Iso, H.; Tamakoshi, A. The Japanese food score and risk of all-cause, CVD and cancer mortality: The Japan Collaborative Cohort Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 120, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oba, S.; Nagata, C.; Nakamura, K.; Fujii, K.; Kawachi, T.; Takatsuka, N.; Shimizu, H. Diet Based on the Japanese Food Guide Spinning Top and Subsequent Mortality among Men and Women in a General Japanese Population. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 1540–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.F.; Zhang, R.; Chan, H.M. Identification of Chinese dietary patterns and their relationships with health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2024, 27, e209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.L.; Li, C.; Zou, S.; Li, Y.; Gong, E.; He, Z.; Shao, S.; Jin, X.; Hua, Y.; Gallis, J.A.; et al. Healthy eating and all-cause mortality among Chinese aged 80 years or older. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2022, 19, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, S.; Park, S.; Yook, S.-M.; Kim, K.; Shim, J.E.; Hwang, J.-Y.; Oh, K. Development of the Korean Healthy Eating Index for adults, based on the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2022, 16, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, A.-R.; Hwang, T.-Y. Relationship between Dietary Patterns and Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Korean Older Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klonizakis, M.; Bugg, A.; Hunt, B.; Theodoridis, X.; Bogdanos, D.P.; Grammatikopoulou, M.G. Assessing the Physiological Effects of Traditional Regional Diets Targeting the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials Implementing Mediterranean, New Nordic, Japanese, Atlantic, Persian and Mexican Dietary Interventions. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Peláez, S.; Fito, M.; Castaner, O. Mediterranean Diet Effects on Type 2 Diabetes Prevention, Disease Progression, and Related Mechanisms. A Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, L.A.; Izuora, K.; Basu, A. Mediterranean Diet and Its Association with Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, L.J.; Di Bella, G.; Veronese, N.; Barbagallo, M. Impact of Mediterranean Diet on Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases and Longevity. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guasch--Ferré, M.; Willett, W.C. The Mediterranean diet and health: A comprehensive overview. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 290, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Steffen, L.M.; Selvin, E.; Rebholz, C.M. Diet quality, change in diet quality and risk of incident CVD and diabetes. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; He, J.; Wu, S.; Zhang, R.; Qiao, Z.; Bian, X.; Wang, H.; Dou, K. Trends in dietary patterns over the last decade and their association with long-term mortality in general US populations with undiagnosed and diagnosed diabetes. Nutr. Diabetes 2023, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Kang, M.; Shvetsov, Y.B.; Setiawan, V.W.; Boushey, C.J.; Haiman, C.A.; Wilkens, L.R.; Le Marchand, L. Diet quality and all-cause and cancer-specific mortality in cancer survivors and non-cancer individuals: The Multiethnic Cohort Study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepandi, M.; Parastouei, K.; Samadi, M. Diet Quality Indices in Relation to Cardiovascular Risk Factors in T2DM Patients: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2022, 13, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayanama, K.; Theou, O.; Godin, J.; Cahill, L.; Shivappa, N.; Hébert, J.R.; Wirth, M.D.; Park, Y.M.; Fung, T.T.; Rockwood, K. Relationship between diet quality scores and the risk of frailty and mortality in adults across a wide age spectrum. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benziger, C.P.; Roth, G.A.; Moran, A.E. The Global Burden of Disease Study and the Preventable Burden of NCD. Glob. Heart 2016, 11, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadnes, L.T.; Økland, J.M.; Haaland, Ø.A.; Johansson, K.A. Estimating impact of food choices on life expectancy: A modeling study. PLoS Med. 2022, 19, e1003889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, V.; Webb, P.; Cudhea, F.; Shi, P.; Zhang, J.; Reedy, J.; Erndt-Marino, J.; Coates, J.; Mozaffarian, D.; Global Dietary Database. Global dietary quality in 185 countries from 1990 to 2018 show wide differences by nation, age, education, and urbanicity. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarnamali, H.; Jayawardena, R.; Chourdakis, M.; Ranasinghe, P. Is the proportion of per capita fat supply associated with the prevalence of overweight and obesity? an ecological analysis. BMC Nutr. 2022, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senior, A.M.; Nakagawa, S.; Raubenheimer, D.; Simpson, S.J. Global associations between macronutrient supply and age-specific mortality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 30824–30835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokdad, A.H.; Mensah, G.A.; Krish, V.; Glenn, S.D.; Miller-Petrie, M.K.; Lopez, A.D.; Murray, C.J.L. Global, Regional, National, and Subnational Big Data to Inform Health Equity Research: Perspectives from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Ethn. Dis. 2019, 29, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, K.; Kawase, F.; Imai, T.; Sezaki, A.; Shimokata, H. Dietary diversity and healthy life expectancy—An international comparative study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 73, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, T.; Miyamoto, K.; Sezaki, A.; Kawase, F.; Shirai, Y.; Abe, C.; Fukaya, A.; Kato, T.; Sanada, M.; Shimokata, H. Traditional Japanese Diet Score—Association with Obesity, Incidence of Ischemic Heart Disease, and Healthy Life Expectancy in a Global Comparative Study. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2019, 23, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, C.; Imai, T.; Sezaki, A.; Miyamoto, K.; Kawase, F.; Shirai, Y.; Sanada, M.; Inden, A.; Kato, T.; Shimokata, H. A longitudinal association between the traditional Japanese diet score and incidence and mortality of breast cancer—An ecological study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 75, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, C.; Imai, T.; Sezaki, A.; Miyamoto, K.; Kawase, F.; Shirai, Y.; Sanada, M.; Inden, A.; Kato, T.; Sugihara, N.; et al. Global Association between Traditional Japanese Diet Score and All-Cause, Cardiovascular Disease, and Total Cancer Mortality: A Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Ecological Study. J. Am. Nutr. Assoc. 2022, 42, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanada, M.; Imai, T.; Sezaki, A.; Miyamoto, K.; Kawase, F.; Shirai, Y.; Abe, C.; Suzuki, N.; Inden, A.; Kato, T.; et al. Changes in the association between the traditional Japanese diet score and suicide rates over 26 years: A global comparative study. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 294, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, T.; Miyamoto, K.; Sezaki, A.; Kawase, F.; Shirai, Y.; Abe, C.; Sanada, M.; Inden, A.; Sugihara, N.; Honda, T.; et al. Traditional Japanese diet score and the sustainable development goals by a global comparative ecological study. Nutr. J. 2024, 23, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAOSTAT. FAOSTAT. 2024. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Trichopoulou, A.; Costacou, T.; Bamia, C.; Trichopoulos, D. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 2599–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019). Data Resources|GHDx. 2024. Available online: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2019 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- WHO. WHO Methods for Life Expectancy and Healthy Life Expectancy Uncertainty Analysis. 2024. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/67748/a78510.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- World Bank Open Data. Data. 2024. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. 2024. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Nlme Package. 2024. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/nlme/index.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Grasgruber, P.; Sebera, M.; Hrazdira, E.; Hrebickova, S.; Cacek, J. Food consumption and the actual statistics of cardiovascular diseases: An epidemiological comparison of 42 European countries. Food Nutr. Res. 2016, 60, 31694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, C.J.; Raubenheimer, D.; Simpson, S.J.; Senior, A.M. Associations between national plant-based vs animal-based protein supplies and agespecific mortality in human populations. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Gobbo, L.C.; Khatibzadeh, S.; Imamura, F.; Micha, R.; Shi, P.; Smith, M.; Myers, S.S.; Mozaffarian, D. Assessing global dietary habits: A comparison of national estimates from the FAO and the Global Dietary Database. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 1038–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chaudhary, A.; Mathys, A. Nutritional and environmental losses embedded in global food waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 160, 104912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, K.; Shimokata, H. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations database (FAOSTAT) and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey—Comparative study of the 50-year change. Nagoya J. Nutr. Sci. 2017, 3, 1–10. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- You, W.; Henneberg, R.; Saniotis, A.; Ge, Y.; Henneberg, M. Total Meat Intake is Associated with Life Expectancy: A Cross-Sectional Data Analysis of 175 Contemporary Populations. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2022, 15, 1833–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institutes of Health. Developing the Healthy Eating Index. 2024. Available online: https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/hei/developing.html#2015c (accessed on 18 July 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.