1. Introduction

The world population is aging at an increasing rate [

1] and it has sparked significant global concerns, particularly in developing countries, where the growing number and proportion of older adults have become a major issue [

2,

3]. In addition, the aging population has resulted in a rise in chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and obesity, as well as various mental health issues such as depression, which pose serious public health problems [

4,

5]. Most of the chronic diseases, by restricting the individual’s ability to live, can lead to the worsened general health of patients, limited performance, reduced health related quality of life, and increased healthcare costs [

6].

As life expectancy increases, it becomes increasingly important to ensure that these additional years are lived with a good quality of life (QoL), even in the presence of chronic illnesses [

7]. Consequently, there is a growing societal emphasis on preventing disability among aging adults to improve their QoL [

8]. In today’s world, improving QoL is widely recognized as a fundamental prerequisite for social progress and a central objective of state policy across countries, regardless of their economic development [

9]. Maintaining QoL is considered one of the most important outcomes of care services for older adults [

1]. Furthermore, promoting QoL in later life is an internationally recognized priority that requires valid and reliable measurement tools [

10]. As a result, assessing QoL has become a key component in the comprehensive care of institutionalized older adults [

11]. There is a multitude of questionnaires for evaluation of QoL, some of which have been developed specifically for older adults [

1].

One of the new instruments available to measure quality of life of elderly people is the Older People’s Quality of Life Questionnaire (OPQOL-35) [

12]. This instrument is of potential value in the outcome assessment of health and social interventions, which can have a multidimensional impact on people’s lives [

13] and is composed of 35 questions divided into eight dimensions that assess life overall (1–4), health (5–8), social relationships (9–13), independence, control over life, freedom (14–17), home and neighborhood (18–21), psychological and emotional well-being (22–25), financial circumstances (26–29), and leisure activities (30–35) [

10]. The OPQOL-35 questionnaire is valuable for assessing the overall QoL in older adults, regardless of their health status. It is particularly well-suited for individuals with normal cognitive function and has also demonstrated applicability for those with mild to moderate dementia [

14].

To our knowledge, the OPQOL-35 has been translated and validated for use in Switzerland [

1], Iran [

12], the Czech Republic [

14], Britain [

15], Slovakia [

16], India [

17], Nigeria [

18], and the OPQOL-35 brief in Norway [

7], Turkey [

19], Persia [

20], Arabia [

21], Spain [

22], China [

23] and Australia [

24]. Unfortunately, this valid instrument has not yet been cross-culturally adapted and validated in Albanian language, which undermines the possibility of using it in Albanian contexts and performing cross-national research regarding quality of life in elderly people. This study was therefore designed to translate, cross-culturally adapt, and psychometrically evaluate the OPQOL-35 among the Albanian older adult population in the city of Vlore.

2. Materials and Methods

Initially, on 10 December 2023, permission was requested for the translation and use of the OPQOL-35 instrument on the eProvide website (

https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org (accessed on 10 December 2023)), and ethical approval from Mapi Research Trust is associated with request number 2320067.

For the linguistic validation and cultural adaptation of the Albanian version of the OPQOL-35 instrument (AL-OPQOL-35), which measures the quality of life of older people, several structured and important steps were followed in January 2024.

A committee of 6 experts with backgrounds in the field of health, education, and scientific research was selected.

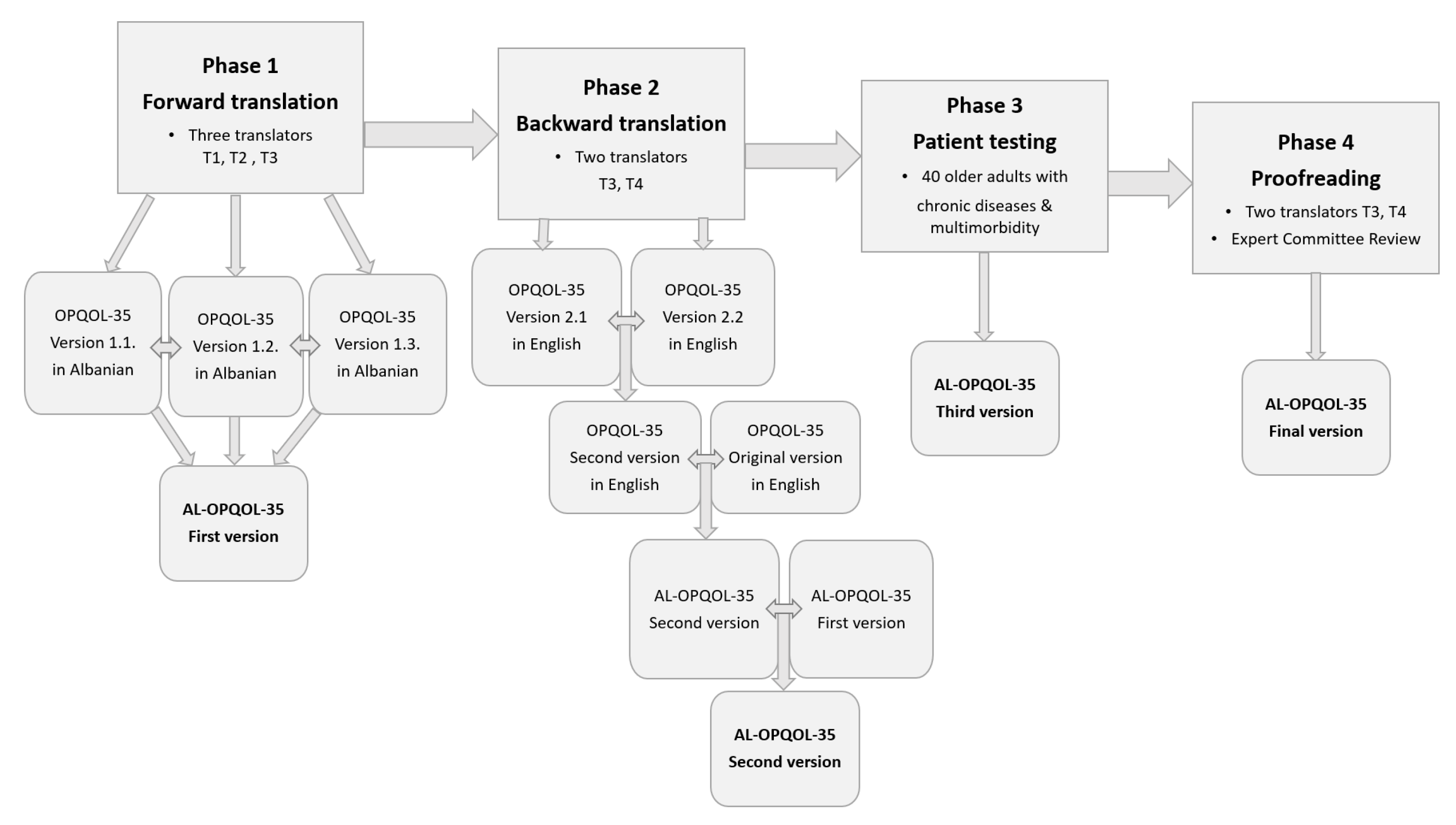

Linguistic and cultural validation was based on the Mapi Research Trust manual which included 4 phases: forward translation, backward translation, patient testing, and proofreading.

2.1. Forward Translation

This first phase included the translation of the OPQOL-35 questionnaire into Albanian (target language) from English (source language) by three professional translators independently, fluent in both Albanian and English.

2.2. Backward Translation

The second phase included the translation of the first version of AL-OPQOL-35 instrument from Albanian into English by two translators, fluent in both Albanian and English, without having access to the original version of the instrument in English.

2.3. Patient Testing

The third phase included pilot testing of the second version of the AL-OPQOL-35 questionnaire (obtained in phase 2) on a small sample from the target population to determine whether it is acceptable, whether it is understood as intended, and whether the language used is simple and appropriate.

The second version of the AL-OPQOL-35 questionnaire was digitized using Google Forms and subjected to cognitive debriefing as well as pilot comprehension and feasibility testing with the same group of 40 older adults.

The subjects recruited for the testing were all native speakers of Albanian language. Participants were fully informed about the study’s purpose, nature, safety, and benefits. They were assured voluntary participation, anonymity, data protection, and the right to withdraw at any time. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants aged 65 and above, who took part in the pilot testing of the instrument. During the individual interviews, they were asked about their age, the number of chronic diseases they experience, any difficulties they encountered while reading the items of the AL-OPQOL-35 instrument, suggested improvements, and their opinions on how the third version should be structured.

Following the revisions made to the second version of the AL-OPQOL-35 instrument based on participant feedback, a third version was finalized. This version was then transferred to Google Forms and prepared for use in a larger population to assess its psychometric properties.

2.4. Proofreading

The fourth phase included proofreading of the third version of the AL-OPQOL-35 questionnaire to avoid any typing, spelling, or grammatical mistakes in the most recent version.

Proofreading of the third version of the AL-OPQOL-35 questionnaire by a proofreader was performed by an English translator whose native language is Albanian language.

The stages of the process of linguistic validation and cultural adaptation of the AL-OPQOL-35 questionnaire are shown in

Figure 1.

The validation process included a cross-sectional study enrolling a convenience sample of 40 older adults with chronic diseases and multimorbidity. Croncach’s alpha was calculated to evaluate the internal consistency and reliability of the total scale and each of its subscales.

3. Results

3.1. Forward Translation

Together, the three translators produced a synthesis of the three translations, resulting in a first Albanian version of the questionnaire. This step ensured terminology consistency, clarity, and cultural relevance.

The most discussed questions regarding the translation into the Albanian language and their use in everyday life was Question 4 and 15, while the translation of other questions had no problems regarding their translation and meaning.

Regarding the Question number 4, with the consent of all the members of the group of translators, the option: ‘Jeta më ka mundur’ (Life has defeated me) was chosen among the three options close to the answers: ‘Jeta më ka rrëzuar’ (Life has knocked me down), ‘Jeta më ka mundur’ (Life has defeated me), and ‘Jeta më ka vënë poshtë’ (Life gets me down).

Regarding the Question number 15, with the consent of all the members of the group of translators, the option ‘Jam i/e kënaqur me atë që bëj’ (I am satisfied with what I do) was chosen between the two options close to the answers: ‘Mund ta kënaq veten me ato që bëj’ (I can please myself with what I do), and ‘Jam i/e kënaqur me atë që bëj’ (I am satisfied with what I do).

3.2. Backward Translation

The two back-translated versions of the questionnaire (from Albanian to English), performed by two translators, were compared with the original English OPQOL-35 and found to match in content and meaning. This comparison led to the creation of a second English version. Therefore, after the committee of experts reviewed the semantic equivalence, idiomatic expressions, and conceptual and cultural relevance, the second version of OPQOL-35 in Albanian remained the same as the first version of AL-OPQOL-35.

3.3. Patient Testing

Individual interviews were used to conduct cognitive debriefing as well as pilot comprehension and feasibility testing. Participants were asked to comment on the clarity and comprehensibility of the questionnaire items, any difficulties experienced during completion, the overall practicality of the instrument, and their interpretation of each item. The average time to complete the questionnaire was 8 min.

The questions that were difficult to understand by the interviewed participants were questions 3, 4, 10, 13, 17, 33, 34, and 35.

The participants proposed the following alternatives:

Question 3 from ‘I pres gjërat me padurim’ (I look forward to things) was changed to ‘I mirëpres situatat e jetës’ (I welcome life situations).

Question 4 from ‘Jeta më ka mundur’ (Life has defeated me) was changed to ‘Jeta më ka zhgënjyer’ (Life has disappointed me).

Question 10 from ‘Do të doja më shumë shoqëri’ (I would like more companionship or contact with other people) was changed to ‘Do të doja të kisha më shumë shoqëri’ (I wish I had more company).

Question 13 from ‘Kam fëmijët e mi afër dhe kjo është e rëndësishme’ (I have my children around which is important) was changed to ‘Të kem fëmijët afër është gjëja më e rëndësishme’ (Having the children close is the most important thing).

Question 17 from ‘Kam shumë kontroll mbi gjërat e rëndësishme të jetës time’ (I have a lot of control over the important things in my life) was changed to ‘Di ti menaxhoj mirë situatat e jetës time’ (I know how to manage my life situations well).

Question 33 from ‘Kam përgjegjësi ndaj të tjerëve, gjë që kufizon veprimtarinë time shoqërore ose të kohës së lirë’ (I have responsibilities to others that restrict my social or leisure activities) was changed to ‘Përgjegjësitë që kam ndaj të tjerëve më kufizojnë aktivitetet e mia shoqërore apo të kohës së lirë’ (My responsibilities to others limit my social or leisure activities).

Question 34 from ‘Feja, besimi ose filozofia janë të rëndësishme për cilësinë e jetës time’ (Religion, belief or philosophy is important to my quality of life) was changed to ‘Të jem pjesë e një besimi fetar apo të besoj është e rëndësishme për cilësinë e jetës time’ (Being part of a religious faith or belief is important to the quality of my life).

Question 35 from ‘Aktivitetet e ndryshme kulturore apo fetare janë të rëndësishme për ciësinë e jetës time’ (Cultural/religious events/festivals are important to my quality of life) was changed to ‘Pjesëmarrja në aktivitete të ndryshme kulturore apo fetare është e rëndësishme për ciësinë e jetës time’ (Participation in various cultural or religious activities is important to the quality of my life).

The feasibility test used data collection methods and participant feedback to identify and revise items that presented comprehension difficulties. Based on this input, the final version of the AL-OPQOL-35 questionnaire was developed.

Table 1 presents demographic and health-related characteristics from 40 elderly participants in the pilot test.

Of these, 75% were female and 25% male. The majority (72.5%) were aged 65–74, followed by 20% aged 75–84, and 7.5% aged over 85. In terms of health status, 25% had a single chronic disease, while 75% were living with multimorbidity.

Table 2 and

Table 3 present information on the internal consistency and reliability of the scale used in the analysis.

The Cronbach’s α of 0.848 indicates good internal consistency and suggests that the scale is a reliable measure of the construct it is intended to assess.

Chronbach’s alpha values for the subscales ranged from 0.645 to 0.875. Most dimensions demonstrated acceptable to good internal consistency, with particularly strong reliability in the health and home and neighborhood domains. However, social relationships and independence, control over life, and freedom showed moderate internal consistency, indicating a need for further item refinement.

3.4. Proofreading

After the cognitive debriefing, the final version of the AL-OPQOL-35 questionnaire was reviewed by a proofreader and confirmed to be free of any typographical, spelling or grammatical errors. This version was subsequently approved by the expert committee (see

Table S1—Supplementary Materials).

4. Discussion

This study is crucial for refining the tools used to assess the quality of life in older adults, particularly those living with chronic diseases and multiple chronic conditions.

As the global population ages, the growing number of older individuals is expected to drive a rapid increase in the demand for healthcare services [

25].

This research presents the first validated and culturally adapted version of the AL-OPQOL-35 questionnaire, specifically designed to assess the quality of life among older populations. Given the increasing elderly population in Albania and other Albanian-speaking regions, this study addresses an urgent need for reliable and culturally relevant tools to measure quality of life and inform age-specific public health interventions.

Translating the OPQOL-35 questionnaire into Albanian is essential to ensure that elderly Albanian speakers can fully engage with healthcare providers when discussing their quality of life. This translation enhances clinical practice by enabling healthcare professionals to deliver more accurate, personalized care, support research efforts, and improve communication with older adult patients in Albania and Albanian-speaking communities.

In accordance with our study, other studies have shown that the OPQOL demonstrates good internal consistency across various settings, aligning with previously reported values in the Czech, Italian, and Sri Lankan versions [

18].

From a public health perspective, the validated AL-OPQOL-35 fills a critical gap by allowing healthcare professionals, researchers, and policymakers to collect reliable data on the well-being of older adults. This can lead to more targeted health policies, better allocation of resources, and stronger support systems tailored to the unique needs of this population. Furthermore, the availability of this tool facilitates cross-cultural research and comparisons in geriatric care across the Balkan region and beyond. Ultimately, the AL-OPQOL-35 promotes improved health outcomes and supports a more inclusive healthcare environment for aging populations.

5. Conclusions

After the evaluation by the expert committee and pilot testing, the OPQOL-35 instrument, translated and culturally adapted into Albanian (AL-OPQOL-35), proved clear and understandable for older adults with chronic diseases and multimorbidity. The Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale was α = 0.848, which indicates good internal consistency and suggests that the scale is a reliable measure of the construct it is intended to assess.

6. Recommendation

It is recommended to use the Albanian version of the OPQOL-35 instrument in a larger population and evaluate its psychometric properties.

7. Study Limitations

While the pilot testing provided valuable insight into the clarity and cultural appropriateness of the questionnaire, its small sample size and limited diversity may restrict the generalizability of the finding. Additionally, the lack of statistical power limits the reliability of preliminary psychometric results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S. and F.K.; writing—original draft preparation, B.S.; writing—review and editing, B.S., F.K., G.S., V.P., E.K. and R.L.; supervision, F.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by Regional Directorate of the Operator of Health Care Services of Vlora (protocol code 358/1, approval date 28 February 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| OPQOL | The Older People’s Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| AL-OPQOL | Albanian version of the Older People’s Quality of Life Questionnaire |

References

- Carrard, S.; Mooser, C.; Hilfiker, R.; Mittaz Hager, A.G. Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Swiss French version of the Older People’s Quality of Life questionnaire (OPQOL-35-SF). Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2022, 20, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggersdorfer, M.; Akobundu, U.; Bailey, R.L.; Shlisky, J.; Beaudreault, A.R.; Bergeron, G.; Blancato, R.B.; Blumberg, J.B.; Bourassa, M.W.; Gomes, F.; et al. Hidden hunger: Solutions for America’s aging populations. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menyhárt, O.; Fekete, J.T.; Győrffy, B. Demographic shift disproportionately increases cancer burden in an aging nation: Current and expected incidence and mortality in Hungary up to 2030. Clin. Epidemiol. 2018, 10, 1093–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maresova, P.; Javanmardi, E.; Barakovic, S.; Barakovic Husic, J.; Tomsone, S.; Krejcar, O.; Kuca, K. Consequences of chronic diseases and other limitations associated with old age–a scoping review. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, S170–S182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, M.; Merchant, R.A.; Morley, J.E.; Anker, S.D.; Aprahamian, I.; Arai, H.; Aubertin-Leheudre, M.; Bernabei, R.; Cadore, E.L.; Cesari, M.; et al. International exercise recommendations in older adults (ICFSR): Expert consensus guidelines. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2021, 25, 824–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siboni, F.S.; Alimoradi, Z.; Atashi, V.; Alipour, M.; Khatooni, M. Quality of life in different chronic diseases and its related factors. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 10, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugan, G.; Drageset, J.; André, B.; Kukulu, K.; Mugisha, J.; Utvær, B.K.S. Assessing quality of life in older adults: Psychometric properties of the OPQoL-brief questionnaire in a nursing home population. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, X. Aging and chronic disease: Public health challenge and education reform. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1175898. [Google Scholar]

- Guliyeva, A. Measuring quality of life: A system of indicators. Econ. Political Stud. 2022, 10, 476–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, A.; Hankins, M.; Windle, G.; Bilotta, C.; Grant, R. A short measure of quality of life in older age: The performance of the brief Older People’s Quality of Life questionnaire (OPQOL-brief). Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2013, 56, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. People-Centred and Integrated Health Services: An Overview of the Evidence; Interim Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nikkhah, M.; Heravi-Karimooi, M.; Montazeri, A.; Rejeh, N.; Sharif Nia, H. Psychometric properties the Iranian version of older People’s quality of life questionnaire (OPQOL). Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, A.; Stenner, P. Which measure of quality of life performs best in older age? A comparison of the OPQOL, CASP-19 and WHOQOL-OLD. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2011, 65, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mares, J.; Cigler, H.; Vachkova, E. Czech version of OPQOL-35 questionnaire: The evaluation of the psychometric properties. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2016, 14, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, A. The Psychometric Properties of the Older People’s Quality of Life Questionnaire, Compared with the CASP-19 and the WHOQOL-OLD. Curr. Gerontol. Geriatr. Res. 2009, 2009, 298950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kačmárová, M. Psychometric Properties of Subjective Assessment of Quality of Life Questionnaire on Sample of Seniors: A Pilot Study. Hum. Aff. 2015, 25, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, T.; Barman, M.P.; Bora, J.; Gogoi, K. Measuring Quality of Life of Elderly People: A Fuzzy Approach. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Innov. Res. 2022, 9, 497–507. [Google Scholar]

- Mgbeojedo, U.G.; Ekigbo, C.C.; Okoye, E.C.; Ekechukwu, E.N.; Justina Okemuo, A.; Ikele, C.N.; Akosile, C.O. Igbo version of the Older People’s Quality of Life Questionnaire (OPQOL-35) is valid and reliable: Cross-cultural adaptation and validation. J. Health Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2022, 59, 00469580221126290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caliskan, H.; Aycicek, G.S.; Ozsurekci, C.; Dogrul, R.T.; Balci, C.; Sumer, F.; Ozcan, M.; Karabulut, E.; Halil, M.; Cankurtaran, M.; et al. Turkish validation of a new scale from older people’s perspectives: Older people’s quality of life-brief (OPQOL-brief). Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 83, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feizi, A.; Heidari, Z. Persian version of the brief Older People’s Quality of Life questionnaire (OPQOL-brief): The evaluation of the psychometric properties. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.I.; Hallit, S.; Fekih-Romdhane, F.; Bitar, Z.; Shaala, R.S.; Mousa, E.F.; Menessy, R.F.; Elnakeeb, M. Psychometric Properties of an Arabic Translation of the older people’s quality of life-brief (OPQOL-brief) scale. Aging Ment. Health 2024, 28, 1532–1539. [Google Scholar]

- Perogil-Barragán, N.; Gomez-Paniagua, S.; Rojo-Ramos, J.; González-Becerra, M.J.; Barrios-Fernández, S.; Gianikellis, K.; Castillo-Paredes, A.; Carvajal-Gil, J.; Muñoz-Bermejo, L. Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Psychometric Properties of the Spanish Version of the OPQOL-Brief. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Hicks, A.; While, A.E. Validity and reliability of the modified Chinese version of the Older People’s Quality of Life Questionnaire (OPQOL) in older people living alone in China. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2014, 9, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milte, C.M.; Walker, R.; Luszcz, M.A.; Lancsar, E.; Kaambwa, B.; Ratcliffe, J. How important is health status in defining quality of life for older people? An exploratory study of the views of older South Australians. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2014, 12, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joling, K.J.; Van Eenoo, L.; Vetrano, D.L.; Smaardijk, V.R.; Declercq, A.; Onder, G.; Van Hout, H.P.; van der Roest, H.G. Quality indicators for community care for older people: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).