1. Introduction

The design of sensory atmospheres in the built environment has increasingly attracted scholarly and professional interest, particularly within retail, hospitality, and cultural spaces [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. The built environment is understood here as comprising all human-made physical surroundings, from architecture to interior spaces, within which sensory dimensions interact to construct identity and meaning [

2]. Within this context, atmospheres denote the perceptual and affective quality of a space as experienced by the body, encompassing light, color, texture, sound, and scent [

3]. Sensory design is thus conceived as a multidisciplinary approach that deliberately engages the human senses to shape perception and emotion through material, spatial, and experiential decisions [

1]. Although the visual dimension has long dominated design practice, olfaction has emerged as a critical yet underexplored sensory layer capable of influencing perception, emotion, and memory [

4,

5,

13,

14]. Smell, often marginalized in design education and professional practice, is increasingly recognized as a powerful vector of multisensory coherence, brand identity, and affective engagement [

4,

9].

In parallel, artificial intelligence (AI) has begun to transform creative and design processes, offering new ways to explore semantic associations, generate correspondences across modalities, and test design hypotheses [

15,

16,

17,

18]. In the field of sensory design, AI should not be conceived as a replacement for human authorship but as a tool for expanding the creative search space, visualizing relationships across modalities, and highlighting ambiguities that require human interpretation [

15,

17,

18]. Despite the growing acknowledgement of smell’s importance in shaping user experience, its use in the design of atmospheres within the built environment remains fragmented. In many cases, olfactory interventions rely on intuition, marketing trends, or isolated artistic experiments rather than on structured methodologies. This limitation became particularly evident when a literature review was conducted to determine whether tools currently exist to guide olfactory design in the built environment [

19,

20].

The results of that review indicate that, although there is substantial research on the effects of ambient scent on perception, emotion, and well-being, no study proposes a concrete, systematic tool to support olfactory design in practice. The existing literature tends either to privilege experiential description or empirical measurement, without integrating these domains into actionable approaches for designers. A clear gap therefore emerges: even with the growing recognition of smell’s influence and the expanding discourse on multisensory design, there is still no methodological tool that operationalizes olfactory design through crossmodal correspondences, understood here as systematic associations between stimuli from different senses (e.g., colors and odors) that shape perception and behavior [

8,

9,

10,

21,

22,

23,

24].

In response to this gap, the present article introduces the Olfactory Attribution Circle (OAC), a conceptual and methodological tool developed through the integration of literature, practice-based insights, and AI-assisted exploration. Rather than framing the inquiry as a binary yes/no question, the study advances a multi-layered analytical agenda structured around the following research questions:

RQ1: How can olfactory design be guided through the systematic alignment of linguistic attributes, colors, and aromas to create coherent multisensory experiences?

RQ2: What role can artificial intelligence play in creating such a tool?

RQ3: How congruent are AI-generated correspondences with existing knowledge from psychology, color theory, perfumery, and crossmodal research?

RQ4: What opportunities and limitations emerge when comparing AI-driven mappings to expert insights and real-world applications?

The built environment constitutes a critical arena for exploring these questions, since architectural spaces do not function as neutral containers but as active mediators of identity and atmosphere. Through materials, spatial layouts, and lighting, they communicate multisensory information that engages smell, vision, and touch in concert [

1,

2,

3]. From this perspective, olfaction cannot be treated as an isolated sensory layer; it must be understood as an integral component of spatial identity, here referring not to brand positioning in a broad marketing sense, but to the multisensory personality of the space, namely (a) the emotional tone it should convey, (b) the sensory cues that should express this tone, and (c) the cultural meanings attached to them. Accordingly, this article does not aim to empirically test the tool in practice; rather, it introduces and examines the OAC as a conceptual pilot for aligning olfaction, color, and semantic attributes, developed with the support of artificial intelligence. It further situates this proposal within a broader understanding of olfactory design as the intentional configuration of smell within spatial experience in coherence with other sensory modalities and with the identity of the space.

3. Theoretical Foundation

The literature review revealed consistent evidence that crossmodal correspondences—systematic associations between olfaction, color and language—play a fundamental role in creating coherent and emotionally resonant multisensory experiences [

8,

9,

10,

23]. However, the review also showed that existing knowledge on olfactory design remains fragmented across disciplines, which made it necessary to consolidate insights from diverse fields to construct a robust theoretical foundation for the OAC.

Building on the patterns identified in the review, four interconnected strands of literature were synthesized to inform the OAC. First, the historical evolution of olfactory classifications was examined to understand how scent taxonomies emerged and how they shaped the perception and organization of odors over time. Second, semantic approaches to sensory meaning were explored to address the symbolic and communicative dimensions of smell—an area in which perfumery taxonomies alone are insufficient. Third, the review identified the relevance of synesthesia and material agency, emphasizing that olfactory experience is multisensory and materially embedded rather than isolated from other perceptual modalities. Finally, a substantial body of empirical studies on crossmodal correspondences between odor and color provided evidence of recurring perceptual patterns that support the alignment proposed in the OAC.

Together, these four strands form a coherent theoretical scaffolding that moves from classification, meaning, material embodiment, and finally to crossmodal integration. This progression allowed the OAC to be positioned not only as a conceptual construct, but also as a methodological tool capable of guiding design decisions that align olfaction, color, and language within the built environment.

3.1. Historical Evolution of Olfactory Classifications

Since antiquity, scholars have tried to impose order on the elusive domain of smell. From Aristotle’s natural groupings to Kant’s dismissal of olfaction as the “poorest” sense, philosophy often reinforced its marginalization [

30,

31]. In the nineteenth century, Piesse (1857) sought analogies with music; in the twentieth century, Henning’s Olfactory Prism (1916) and Jellinek’s (1951) psychological axes proposed geometric or affective orderings, but these proved fragile under scrutiny [

32,

33,

34,

35]. Within perfumery, classification took more durable forms (see

Figure 2): the Drom Fragrance Wheel (1911) and Michael Edwards’ Fragrance Wheel (1983) grouped perfumes into families such as Floral, Oriental, Woody, and Fresh, and remain widely used as communicative tools for consumers [

31]. Their clarity and usability explain their persistence, yet their taxonomic and market-driven nature limits explanatory power: they do not address underlying perceptual mechanisms or cultural and crossmodal dynamics. Contemporary initiatives such as McLean’s Urban Smellscape Aroma Wheel (2017) show how odors can be collaboratively mapped in cities, but again rely on visual or metaphorical translations. Taken together, these representations provide historical baselines and help clarify the communicative legacy on which the OAC builds, while underscoring the need for a tool that supports sensory design reasoning [

31].

3.2. Semantic Approaches for Structuring Sensory Meaning

If taxonomies sought to stabilize smell, semantic research reframed it as a language. Krippendorff’s Semantic Turn (2006) is pivotal here: design is understood as a communicative act in which descriptors function as semantic units, encoding perceptual, cultural, and affective meanings [

36,

37]. Classen, Howes, and Synnott (1994) showed that odors act as cultural signs shaping social relations, while Pastorelli (2003, 2006) and Martone (2019) developed grammars of perfume consistent with this linguistic view [

28,

38,

39,

40]. Similarly, Santos (2009) and Santaella (2018) demonstrated how product languages can be systematically structured through semantic approaches [

41,

42]. Broader semantic and cultural theories confirm that both odors and colors carry layered symbolic codes mediating identity, emotion, and memory across cultures [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50].

Architecture and design research reinforced this communicative perspective. Pallasmaa (2005) emphasized the phenomenology of sensory atmospheres, and Henshaw et al. (2017), together with Lupton and Lipps (2018), highlighted smell as an active design element shaping spatial and product experiences [

2,

21,

31]. Desmet and Hekkert (2007) linked emotional design to affective mappings between meaning and materiality, while Velasco and Spence (2019) extended this to multisensory coherence [

7,

51]. Within this trajectory, Boeri (2019) validated a system of twelve semantic attributes—Delicate/Strong, Dynamic/Static, Fragile/Solid, Light/Heavy, Soft/Hard, Tidy/Messy—showing their inclusivity and neutrality compared with stereotypical commercial categories such as “masculine” or “feminine” [

52,

53].

Building on these precedents, the OAC operationalizes Krippendorff’s linguistic model by organizing sensory meaning into a closed grammar of twelve attributes. This structure ensures coherence and interpretability while remaining open to contextual and cultural adaptation. A concrete illustration of scent’s linguistic potential appears in Dolce & Gabbana’s exhibition Dal Cuore alle Mani (From the Heart to the Hands), presented in Milan in 2024. Rose was chosen as the central essence for its embodiment of Italian craftsmanship—delicate yet strong, deeply rooted in Mediterranean culture. Through this curatorial choice, the exhibition showed how olfaction can function as a semantic medium, articulating identity, tradition, and aesthetic coherence through atmosphere.

3.3. Synesthesia and Material Agency

Synesthesia—understood as the involuntary and consistent blending of sensory modalities—has long been used as a metaphor to describe multisensory perception and aesthetic experience [

11]. While neurological synesthesia remains a rare condition, its conceptual interpretation has enriched design research by revealing how the senses interact to generate meaning and emotion. In the context of sensory design, this perspective emphasizes that perception is inherently multimodal: vision, smell, touch, and hearing are not isolated channels but overlapping dimensions of an embodied system of sense-making [

8,

9,

54]. Within this approach, materiality emerges as a key agent in shaping sensory experience.

Bennett (2010) introduced the notion of

vibrant matter to describe how materials exert agency—affecting perception, behavior, and atmosphere. In design practice, this perspective invites recognition of materials not as passive carriers but as active participants in sensory communication [

55]. Surfaces, textures, and substances emit multisensory cues—olfactory, tactile, visual, and even auditory—that together construct spatial identity and emotional resonance.

Aesop’s The Second Skin at Milan’s Fuorisalone in 2025 exemplified this principle by demonstrating the agency of materials as olfactory and tactile communicators (see

Figure 3). Cedarwood, a central element in the brand’s formulations, permeated the installation both as structure and aroma, engaging visitors through its scent, texture, and the subtle sound it emitted upon touch.

Matter itself thus became expressive, communicating through its multisensory affordances rather than through symbolic representation alone [

56]. From a

phenomenological standpoint, this convergence of senses reveals that

perception is not a sequential process but a synthesis of co-present modalities. As Merleau-Ponty (1945) and Böhme (1993) argued, atmosphere arises from this unity: when color, scent, and texture resonate in tone, intensity, and semantic valence, they generate a sense of perceptual rightness—a pre-reflective harmony that stabilizes emotion and deepens spatial awareness [

54,

56]. In this view, material agency and crossmodal interaction are inseparable dimensions of experience, where design becomes the art of orchestrating relations among matter, sensation, and meaning.

3.4. Crossmodal Correspondences Between Odor and Color

Empirical research confirms that smell and vision are not perceived in isolation but interact systematically [

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78]. Gilbert, Martin, and Kemp (1996, 2008) identified stable hue–odor correspondences (e.g., citrus–yellow, floral–pink), and Kemp and Gilbert (1997) showed that odor intensity aligns with color value, with stronger odors linked to darker tones [

57,

58,

59]. Morrot, Brochet, and Dubourdieu (2001) demonstrated that wine aroma judgements can be shifted by color alone, while Schifferstein and Tanudjaja (2004) found consistent pairings of fruity aromas with bright warm colors and woody aromas with darker, desaturated hues [

60,

61].

Demattè, Sanabria, and Spence (2006) highlighted the mediating role of semantics, and Stevenson, Prescott, and Boakes (1999) distinguished perceptual, semantic, and hedonic pathways for congruence [

62,

63]. Herz (2004, 2007, 2016) further showed how odors, memory, and affect are tightly linked, underscoring the emotional dimension of crossmodal mappings [

63,

64,

65,

66]. Levitan et al. (2014) reviewed cross-cultural evidence, confirming both robustness and variability, while Spence (2011, 2020) emphasized their applied relevance in branding, packaging, and retail design [

8,

9,

24,

67,

68].

Color psychology reinforces these findings: lighter, less saturated hues tend to be perceived as delicate, calm, or fragile, whereas darker, more saturated tones communicate solidity, heaviness, or strength [

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78]. Boeri (2019) confirmed the semantic stability of such associations in design education. Overall, crossmodal congruence emerges as systematic rather than incidental: when odor and color are aligned, perception becomes clearer, affective responses intensify, and memorability increases; when they are misaligned, multisensory experiences can become noisy or confusing [

52,

53].

Here, semantic attributes become crucial. By translating perceptual qualities into descriptors such as Delicate/Strong, Fragile/Solid, Light/Heavy, or Soft/Hard, designers gain a shared language for aligning odor and color with greater precision. These attributes bridge abstract identity and material execution, allowing congruence to be deliberately designed rather than left to chance. The literature converges on three insights: (1) color and odor are semantically loaded, though culturally mediated; (2) their crossmodal correspondences are systematic and design-relevant; and (3) semantic attributes provide a validated way to secure congruence in practice. What remains missing is a methodology that integrates these strands into a tool for branding and spatial atmospheres.

4. Empirical Foundation: Interviews and Case Study

4.1. Semi-Structured Interviews: Academia and Industry

As introduced in

Section 2. (

Methodology), the semi-structured interviews yielded seven thematic axes that informed the subsequent analysis: (1)

Materiality; (2)

Inclusivity; (3)

Feasibility and

SMEs; (4)

Intensity; (5)

AI Role; (6)

Strategic potential; and (7)

Sustainability. To support clarity in this section,

Table 3 revisits these axes and synthesizes key convergences and divergences across academic and industry perspectives, forming the analytical frame for the discussion that follows. A fundamental convergence across all participants was that olfactory design cannot be reduced to the diffusion of added fragrances. Materials themselves—woods, leathers, textiles, metals, paints, and finishes—possess intrinsic odors that actively shape atmospheres.

As the academic specialist in sensory architecture noted, “The scent of a space is never neutral; materials breathe.” This insight reinforces the notion of material agency: matter itself exerts influence, communicating multisensory information through its olfactory, tactile, and visual properties. The industry consultant echoed this, observing that “materials can act as base notes in the olfactory composition of a brand space.” Within the logic of the OAC tool, this reinforces that olfaction must not be treated as an external “plug-in” but as a dimension inherently tied to materiality and crossmodal coherence. Another major point of consensus was inclusivity. Both academic and industry participants criticized the fragrance market’s reliance on gendered and generational stereotypes—florals as “feminine,” woody notes as “masculine,” fresh accords as “youthful.” The academic and the color specialist particularly emphasized that such categories limit creative freedom and reinforce cultural biases. Divergences emerged most clearly around economic feasibility and scalability.

When the author inquired about the potential for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to implement olfactory strategies—a question motivated by the practical constraints often observed in design consultancies—the responses revealed a structural divide between large-scale and small-scale operations. The representative from manufacturing expressed skepticism, noting that “for smaller brands, scenting often feels like a luxury rather than a strategy,” citing the costs of equipment, maintenance, and compliance. Conversely, the independent consultant argued that emerging diffusion technologies—such as programmable smart diffusers connected via mobile applications—are already lowering barriers, making sensory strategies more accessible and adaptable. These discussions underscored that democratizing olfactory design requires scalable, low-cost tools that translate conceptual richness into feasible application. The issue of intensity control was unanimously emphasized. Across both academic and industrial perspectives, respondents warned that diffusion must be calibrated: excessive concentration risks sensory fatigue or rejection, while low intensity results in perceptual absence.

When questioned about sustainability, participants responded to a provocation from the author regarding the relationship between ethical sourcing, sensory authenticity, and brand perception. This line of questioning revealed an important contemporary shift: beyond regulatory compliance, sustainability is increasingly perceived as a sensory value. The manufacturing representative observed that “sustainability smells like authenticity—people can perceive when materials are real.” This sentiment was echoed by the academic interviewee, who linked sensory sustainability to phenomenological presence: the ability of natural or crafted materials to communicate care, permanence, and embodied ethics.

Practices such as refillable systems, local sourcing, and visible craftsmanship were cited as contributing not only to ecological responsibility but also to richer, more authentic sensory experiences. Despite shared values, divergent perspectives persisted on the role of artificial intelligence. The academic and manufacturing representatives approached AI with skepticism, questioning its ability to interpret cultural nuance or emotional complexity, while the consultant and color specialist viewed it as a potential catalyst for creative exploration and methodological consistency. This polarity mirrors the broader tension within design research between computational reasoning and embodied expertise. For the OAC, it reaffirmed that AI should serve as a creative collaborator—a tool for generating connections and hypotheses that must be validated and refined by human interaction.

4.2. Case Study: EveryHuman’s Algorithmic Perfumery

The Copenhagen unit of Every Human (see

Figure 4), inaugurated in 2024, provided the setting for this study and served as a living laboratory for observing how computational systems mediate between individual attributes, crossmodal associations, and olfactory outputs. The observational approach with active participation allowed the author to engage in the full user journey.

This approach included completing the online questionnaire, experiencing the AI-driven generation of fragrances, interacting with the store and its technological interface, and documenting each stage through detailed notes and photographs [

27]. Such an approach ensured firsthand understanding of both the human–machine interaction and the sensory outputs produced, situating the case within broader discussions of human-centered design in multisensory environments [

4,

5,

6]. A distinctive feature of the process was the comprehensive questionnaire, structured into 22 sections covering demographic, lifestyle, and personality descriptors, as well as abstract associations such as the “Bouba/Kiki” test and self-perception along axes like “realist” or “dreamer.”

Particularly significant was the integration of an interactive color wheel, which enabled users to select from an expansive chromatic spectrum. This step underscored the importance of color in olfactory attribution: warm hues such as reds and oranges often aligned with gourmand or spicy accords, while cooler hues like blues and greens tended to correspond with aquatic or herbal compositions. These findings resonate with prior crossmodal research, which consistently demonstrates perceptual linkages between visual and olfactory modalities [

7,

8,

9,

61,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73]. Once the questionnaire was completed, the AI processed the data and produced three distinct fragrance options. Each option included a breakdown of top, heart, and base notes, a chromatic representation that reflected the inferred identity, and semantic mappings that linked linguistic descriptors and personality traits to olfactory families. For instance, participants who described themselves as “energetic” were directed toward citrus and aldehydic accords; those who identified as “dreamers” or “artsy” were associated with floral–woody nuances, while individuals selecting “dark” as a defining attribute received resinous or smoky formulations.

These mappings illustrated the underlying principle of attribution: the transformation of verbal and chromatic input into olfactory output. The experience culminated in the physical preparation of the perfume, where robotic installations blended the chosen formula with visible mechanical precision. The process was complemented by the personalization of labels and packaging, as well as the opportunity for iterative refinement. A dedicated “scent exploration table” allowed participants to test individual fragrance notes, compare them with the generated blends and request adjustments. This stage emphasized the role of human agency: while AI generated the initial formulations, refinement required judgment, negotiation, and cultural interpretation by both staff and users.

The study revealed several key insights: (1) the system demonstrated a notable capacity to translate abstract attributes into coherent olfactory formulations, supporting the notion that semantic descriptors and chromatic choices can serve as reliable inputs for fragrance design; (2) the incorporation of color confirmed the importance of crossmodal congruence, reinforcing existing literature that highlights the systematic alignment of brightness, saturation, and hue with odor intensity, volatility, and weight; and (3) the case underscored that AI cannot operate independently of human authorship. Human actors remained essential in calibrating intensity, fine-tuning accords, and ensuring cultural and contextual relevance.

In terms of implications for the OAC tool, the Every Human case demonstrates that the combination of language attributes and chromatic cues offers a viable pathway for structuring olfactory design. It also shows that effective sensory environments require iterative refinement between computational systems and human interpretation, rather than automated generation alone. Moreover, the case highlights the importance of controlling intensity and dosage—a concern raised by interviewees and noted in sensory design literature [

1] —to ensure that fragrances enrich rather than overwhelm an atmosphere. Finally, the study affirms the position that AI functions as an augmentation tool: it broadens the creative search space and reveals patterns of correspondence, but the ultimate responsibility for coherence and cultural resonance rests with the designer.

5. Results

The divergences identified in the interviews—particularly regarding the role of artificial intelligence in olfactory design—together with insights from the Every Human case study and the literature on crossmodal correspondences, color theory, semantics, psychology, and perfumery, informed the development of the OAC. Conceived as a hybrid tool, the OAC combines AI-assisted exploration with authorial design judgment to test whether artificial intelligence can coherently align aromas, colors, and linguistic attributes while acknowledging its cultural and visual limitations. The results are presented in two parts: first, the AI-assisted construction of the OAC, and second, its proposed application as a step-by-step tool for olfactory design in the built environment.

5.1. Creation of the OAC

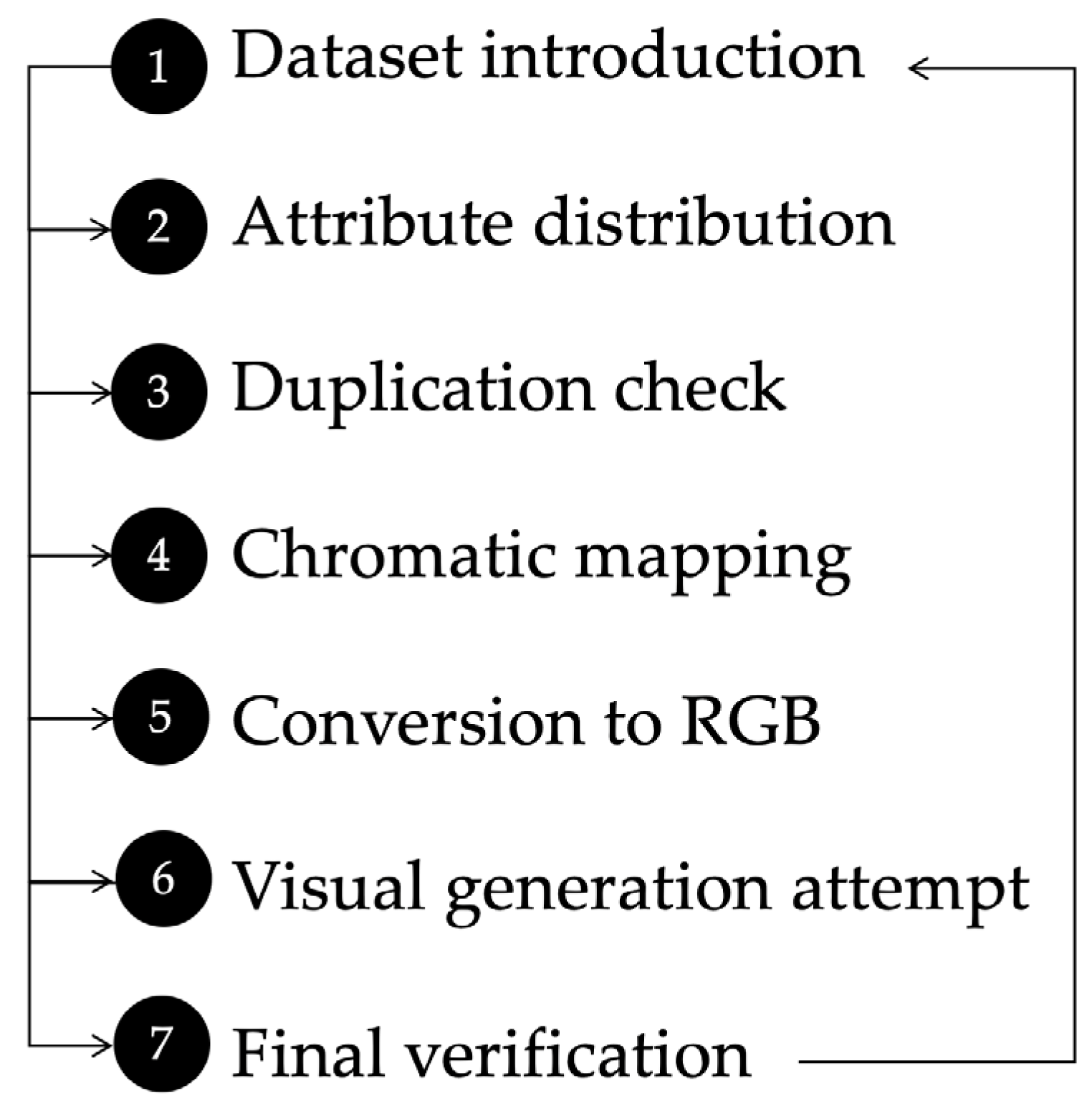

The creation of the Olfactory Attribution Circle (OAC), as previously presented in

Section 2 (Methodology), consisted of seven sequential and iterative steps: (1) Dataset introduction; (2) Attribute distribution; (3) Duplication check; (4) Chromatic mapping; (5) Conversion to RGB; (6) Visual generation attempt; and (7) Final verification.

Table 4 presents this procedure, describing the main action and purpose of each step.

The process began with a dataset of 60 essences/essential oils, each labeled with common and scientific names and classified into established olfactory families (

Floral,

Fruity,

Woody,

Amber/

Oriental,

Aromatic,

Citrus,

Musky). Curated by the author, drawing on Martone (2019), this taxonomy aligned the dataset with perfumery literature and increased input reliability; scientific nomenclature reduced ambiguity from culturally variable common names and grounded the dataset academically [

28].

To link essences to semantic dimensions, they were mapped to twelve attributes validated in design/color research—Delicate/Strong, Dynamic/Static, Fragile/Solid, Light/Heavy, Soft/Hard, Tidy/Messy—selected for robustness, neutrality, and inclusivity [

7,

51,

52,

53]. The AI was then engaged through an iterative prompting sequence designed by the author: first prompt—ingesting the 60 essences (tagged by family); second prompt—introducing the twelve attributes; subsequent prompts—instructing the model to distribute essences evenly (five per attribute) and to eliminate duplicates. Early outputs exhibited duplicates (e.g., Rose under both “Soft” and “Solid”; Pomegranate under “Soft” and “Messy”), which reflected polysemy in olfactory semantics and the model’s difficulty with cultural nuance. Without authorial semantic intervention, iterative prompting and constraint tightening produced a balanced, duplication-free distribution.

Next, a prompt asked the AI to associate each essence with a color—initially in the

Natural Color System (NCS) and then translated to RGB for digital representation. Results echoed documented crossmodal correspondences (e.g., citrus with bright/luminous hues; woody/resinous with darker/heavier tones) [

7,

61]. NCS—widely used in architecture and environmental design—enabled precise specification of hue, saturation, and brightness in built environments, while RGB ensured continuity with computational and visualization tools. The convergence between these outputs and prior empirical findings supported the plausibility of the model’s semantic reasoning.

Limitations emerged—one semantic and one visual. Semantically, ambiguity persisted (e.g., Rose between “Soft” and “Solid”; Labdanum as “Heavy” and “Static”), underscoring the challenge of reconciling cultural/semantic complexity. Visually, when prompted to generate the OAC diagram, the model repeatedly failed to segment the circle into twelve equal sectors and apply the provided color codes faithfully, revealing difficulty in integrating structured design constraints into a coherent graphic output and delineating the boundaries of its applicability. Consequently, the author manually constructed the final OAC diagram and consultation table, ensuring conceptual integrity and usability while maintaining all AI-generated correspondences intact.

The final consultation table (see

Appendix B) includes the categories: (a)

Essential Oil; (b)

Scientific Name; (c)

Olfactory Family; (d)

Language or

Semantic Attribute; (e)

Meaning; (f)

Color (

NCS Code); (g)

Color (

RGB Code); and (h)

Color Description. This format provides a transparent reference for design applications and future validation studies. The visual OAC diagram (see

Figure 5) was organized as a circle divided into sixty equal segments, each representing one essence identified by its RGB color and grouped under the twelve semantic attributes (five essences per attribute). The outer ring displays the attributes, forming the conceptual perimeter, while inner connections link each attribute to its associated essences and colors. These generate a multisensory palette, where chromatic and olfactory nuances interact as complementary layers—much like top, heart, and base notes in perfumery. In the same way, semantic attributes are layered rather than singular, capturing the complexity and nuance of atmosphere construction.

The diagram also follows a geometric symmetry: each attribute’s opposite occupies a diametrically opposed position (e.g., Delicate opposite Strong, Light opposite Heavy). This mirrored configuration enhances cognitive legibility and visual balance, allowing designers to perceive contrasts and affinities across the sensory spectrum briefly. By aligning opposites spatially, the OAC fosters comparative reasoning and aids in evaluating congruence and tension among olfactory, chromatic, and linguistic dimensions. In this sense, while AI functioned as a generative partner, surfacing associations and ambiguities, the construction of both the consultation table and the diagram required human authorship for formatting, organization, and visualization—without altering the semantic or chromatic relationships produced by the system. The result is a replicable and transparent process that combines computational logic with human sensibility, establishing the OAC as a methodological and interpretive tool for multisensory design.

5.2. Implementation of the OAC

The implementation of the Olfactory Attribution Circle (OAC) follows a methodology inspired by established design process models, structured into four iterative and interdependent phases—Investigate, Attribute, Designate, and Test. Each phase guides designers from the exploration of identity and perception to the materialization and evaluation of sensory coherence. (see

Table 5) [

79,

80].

The OAC is proposed as a structured tool that assists designers, architects, brand managers, and consultants in systematically integrating olfaction into spatial and brand experiences. Its application is particularly relevant in fields such as retail, hospitality, cultural exhibitions, and brand activations, where the built environment acts as a communicative medium and sensory elements profoundly influence perception, identity, and memory. The OAC provides an approach that bridges conceptual and operational dimensions of design, transforming abstract emotional or semantic intentions into tangible olfactory, chromatic, and material expressions. Each phase connects identity-driven narratives to sensory and material decisions, ensuring coherence, inclusivity, contextual grounding, and feasibility within real project constraints.

5.2.1. Investigate

The process begins with defining the sensory–spatial identity of the project—that is, the intended atmospheric character of the environment and the way the experience should be perceived, felt, and interpreted by its users. In this context, identity refers not to brand positioning in a broad marketing sense, but specifically to the multisensory personality of the space: (a) the emotional tone it should convey, (b) the sensory cues that should express this tone, and (c) the cultural meanings attached to them.

To articulate this identity, the process examines three interconnected layers that converge through language-based reasoning: (1) Users—identifies needs, expectations, perceptual tendencies, and emotional responses to sensory cues, generating initial descriptive terms that later inform the semantic vocabulary of the project. (2) Built environment—analyzes spatial layout, materiality, lighting, circulation, and architectural affordances that condition how sensory stimuli are perceived and interpreted. Here, materials and spatial conditions act as sensory carriers that shape meaning. (3) Narrative—defines what is being communicated (e.g., products, services, or immersive activations) in explicitly semantic terms. The narrative provides the linguistic foundation for the atmosphere, guiding the choice and clustering of words into the twelve bipolar attributes of the OAC.

This phase relies on ethnographic and observational methods—such as field studies and semi-structured interviews—to ensure that the identity is grounded in lived experience rather than defined solely by aesthetic aspiration. Consistent with multisensory research, the Investigate phase highlights that identity mapping must consider not only material and functional attributes, but also the cultural and symbolic repertoires through which colors, aromas, and atmospheres acquire meaning [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

5.2.2. Attribute

In the second phase, descriptors of the intended identity are elicited through workshops or focus groups involving diverse stakeholders—designers, clients, brand managers, and architects. Participants are encouraged to freely generate words describing the atmosphere, personality, or emotional tone they wish to convey. This initial stage is intentionally open and intuitive, capturing affective and perceptual expressions without categorical restrictions. Once the vocabulary is collected, a semantic clustering process organizes these terms into relational groups. Through facilitation, participants identify affinities in tone, mood, and sensory connotation—grouping words that “speak the same emotional language.” This collective interpretation progressively leads to the twelve semantic attributes validated in design and color research (Delicate/Strong, Dynamic/Static, Fragile/Solid, Light/Heavy, Soft/Hard, and Tidy/Messy) [

7,

51,

52,

53].

For instance, words such as calm, serene, translucent, and gentle may converge in the Delicate cluster, associated with harmony and refinement, often corresponding to light color values and olfactory notes. In contrast, terms like dense, mechanical, and robust gravitate toward Hard, evoking persistence and structure, linked to darker palettes and heavier aromatic accords such as smoky or resinous tones. This phase is interpretive rather than algorithmic: it values resonance over consensus. Participants negotiate nuances, translating perceptions into shared semantic categories. It also reinforces inclusivity, as these attributes are gender- and age-neutral, allowing cultural reinterpretation. Once finalized, the OAC diagram is introduced as a visual and cognitive mediator, prompting reflection on how linguistic intentions can be embodied through congruent combinations.

5.2.3. Designate

The

Designate phase focuses on material and sensory articulation, translating abstract attributes into coherent design strategies. Fragrance composition follows the logic of perfumery: (a)

Top notes (e.g., citrus, herbs) introduce brightness and vitality; (b)

Heart notes (florals, fruits) sustain atmosphere; (c)

Base notes (woody, resinous) provide depth and persistence. Materiality also plays an active role, as architectural materials function as olfactory agents (Bennett, 2010) [

55]. Woods such as cedar or oak, as well as leathers and textiles, release intrinsic odors that merge with added essences, forming a holistic olfactory identity. The color palette complements this structure—pastels and high-value tones express Delicate or Fragile, while darker, saturated hues evoke Strong or Heavy. Feasibility and sensory control are central. Programmable diffusers connected to mobile apps enable precise and economical aroma dispersion, ensuring balance, consistency, and sustainability. As Malnar and Vodvarka (2004) argue, overexposure leads to fatigue, while underexposure compromises perception [

1]. Finally, this phase integrates economic and environmental responsibility. Olfactory design must operate within material, budgetary, and maintenance constraints, aligning with Mozota’s (2006) view of design as a strategic function bridging creativity and organizational reality [

79].

5.2.4. Test

The Test phase evaluates whether the designed sensory experience successfully communicates the intended identity. The assessment examines perceptual congruence—whether aromas, colors, and brand values align to produce a coherent and memorable atmosphere. Evaluation tools may include experience diaries, post-experience interviews, affective scales such as SAM or PAD, and behavioral measures (e.g., dwell time). Research consistently shows that crossmodal congruence enhances recognition, engagement, and purchase intention [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Through testing, designers refine both sensory balance and narrative expression, ensuring that olfactory strategies remain perceptible yet subtle, distinctive yet inclusive.

Taken together, these four sequential and iterative phases (see

Figure 6) demonstrate how the OAC functions as a methodological bridge between linguistic expression, chromatic perception, and olfactory experience. By grounding sensory design in validated semantic attributes and aligning it with available resources, technologies, and evaluation tools, the OAC establishes a process that is

inclusive (avoiding stereotypes and enabling participation),

strategic (balancing creativity with feasibility), and

empirically grounded (supported by design theory and multisensory research). Ultimately, the OAC operates as both a creative compass and a decision-making tool, guiding the development of atmospheres that are congruent, memorable, and emotionally resonant.

6. Discussion

The OAC illustrates one possible way of organizing crossmodal correspondences between language, color, and aroma within a design workflow. The outputs indicate a degree of coherence with existing research and with reflections from both academic and industry participants, while also highlighting constraints associated with the use of AI in sensory design. Observed correspondences—such as Delicate, Fragile, Light, and Soft aligning with high-value, low-chroma palettes and floral or fruity essences—are consistent with patterns frequently reported in crossmodal and color–emotion studies [

8,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78]. In this regard, the OAC consolidates such relations into a structured format that can support reasoning across perceptual, semantic, and cultural dimensions.

At the same time, several interpretive tensions emerged, suggesting that the tool requires careful application. For example, the AI did not assign essences to neutral or “non-color” categories such as greys, despite their frequent use in spatial design to modulate atmospheres—indicating a potential computational limitation. Similarly, allocations such as Vanilla under Heavy or Pomegranate under Soft disrupted the circular balance. These points illustrate the variability and cultural nuance inherent to olfactory semantics. Accordingly, the OAC may be more appropriately understood as a heuristic rather than a prescriptive model—supporting reflection and adaptation rather than fixed mappings.

Insights from the interviews further contextualized these findings. Participants emphasized that materials act as inherent sensory carriers: woods, leathers, textiles, and metals release intrinsic odors that interact with added essences, influencing spatial identity. This view is consistent with the notion of material agency [

55] and aligns with the Designate phase of the OAC, where atmosphere is conceived as a layered composition integrating both designed scents and material emissions. Temporary installations in commercial contexts, such as The Second Skin, illustrate how materiality and olfaction can operate in concert to produce multisensory effects. Interviewees also commented positively on the use of neutral semantic attributes within the OAC, noting their potential to reduce reliance on gendered or generational stereotypes and to allow broader interpretive participation.

Intensity was a recurrent concern among interviewees. Excessive diffusion may overwhelm occupants, while insufficient diffusion may render the olfactory layer imperceptible: echoing the principle of sensory balance widely discussed in environmental and sensory studies [

1]. The OAC attempts to integrate this consideration by recommending programmable diffusion technologies to support consistency, moderation, and potential reductions in waste. Sustainability was also raised as a concern, with participants highlighting ethical issues associated with certain natural essences (e.g., sourcing and biodiversity). Future applications of the OAC may therefore benefit from incorporating sustainability-related decision criteria, for example, favoring certified or renewable alternatives (e.g., IFRA, FSC, Ecocert).

Although examples referenced in this research—such as Aesop installations and branded olfactory strategies—demonstrate the expressive potential of multisensory work, they largely reflect practices within premium or culturally influential sectors. This may reinforce a perception that sensorially coherent olfactory strategies are predominantly adopted by organizations with significant financial, cultural, or technological resources. The OAC was conceived partly in response to this condition, aiming to provide a more structured yet approachable method that could be adapted by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) as well as independent studios. While further empirical validation is required, its modularity suggests potential to support more accessible applications of olfactory and crossmodal design beyond luxury contexts.

Divergent perspectives also emerged regarding the role of artificial intelligence. Participants acknowledged the value of AI for broadening the exploratory space and enabling rapid association-building; however, reservations were expressed about its capacity to account for cultural nuance, emotion, and situated interpretation. The OAC reflects this tension: the AI was effective in generating preliminary essence–attribute–color mappings aligned with crossmodal literature, yet was unable to produce a usable visual diagram, highlighting limitations in managing spatial, perceptual, and aesthetic considerations. Human curation was required to refine the AI outputs into the consultation table and circular diagram, suggesting that AI may currently be better positioned as a generative support rather than an autonomous design agent.

From a phenomenological standpoint, crossmodal congruence extends beyond perceptual alignment and contributes to the formation of an integrated field of experience. Rather than being processed as discrete sensory inputs, sensory impressions interact and co-constitute atmosphere [

54,

56]. When color, smell, and language resonate in tone and intensity, they may evoke a sense of perceptual coherence that supports orientation and emotional engagement; intentional incongruence, in contrast, may be used to create friction or prompt curiosity. Within this view, the OAC may be seen as offering one possible approach for supporting aesthetic intentionality in the arrangement of multisensory cues. Taken together, the findings suggest that multisensory design may benefit from approaches that are both systematic and interpretive. The OAC does not aim to define correct solutions but to provide a structure for examining how olfactory, chromatic, and linguistic dimensions might be considered in relation to one another. In this respect, it contributes to ongoing discussions on how design methods might engage more critically with the sensory constitution of atmosphere within the built environment.

The interpretation of findings was strengthened through a triangulated comparison of four evidence sources (see

Table 6)—literature, semi-structured interviews, the

EveryHuman case study, and AI-generated outputs. This triangulation enabled the identification of areas of convergence (e.g., crossmodal congruence, material agency, intensity control, inclusivity) and divergence (e.g., cultural ambiguity of semantic attributes, limits of AI visualization) and informed the development of the Olfactory Attribution Circle (OAC). Comparing evidence across sources also reduced the risk of over-reliance on any single perspective by enabling AI-assisted correspondences to be examined in relation to theoretical research and practice-based accounts.

7. Conclusions

This research set out to explore whether olfactory design can be systematically guided by linguistic attributes and chromatic associations to create coherent multisensory experiences. The findings confirm that this alignment is both feasible and conceptually meaningful. The Olfactory Attribution Circle (OAC) consolidates language, color, and scent into a structured, inclusive, and replicable tool for multisensory branding and environmental design, bridging theoretical, technical, and experiential dimensions of sensory practice.

In response to (RQ1), the study demonstrates that olfactory design can indeed be guided through the systematic alignment of linguistic attributes, colors, and aromas by means of a structured process. The four phases of the OAC—Investigate, Attribute, Designate, and Test—translate abstract identity descriptors into sensory configurations, connecting meaning, emotion, and materiality. By organizing these relations through twelve semantic attributes, the OAC establishes a shared vocabulary that avoids gendered or generational bias and supports interpretive flexibility across cultural contexts.

Concerning (

RQ2), artificial intelligence played a significant yet clearly delimited role in mediating the construction of the tool. The AI-generated mappings between essences, attributes, and chromatic codes revealed both the potential and the limitations of computational reasoning. While it successfully exposed underlying crossmodal correspondences and aided in the organization of semantic data, it struggled with polysemy and ambiguity, confirming that human interpretation remains indispensable in achieving conceptual clarity, cultural resonance, and aesthetic refinement. As for (

RQ3), the AI-generated correspondences showed strong consistency with existing empirical knowledge from psychology, color theory, perfumery, and crossmodal research. The alignment of citrus essences with luminous hues and woody or resinous notes with darker tones echoed established studies [

57,

61,

62,

67,

68]. This convergence validated the semantic logic underpinning the OAC, even as certain ambiguities—such as the treatment of neutral tones—revealed areas where computational reasoning remains insufficient.

Finally, (RQ4) addressed the relationship between AI-driven mappings, expert insight, and real-world practice. The interviews confirmed that olfactory design requires interpretive and ethical awareness, as designers must consider material behavior, sustainability, and the environmental impact of fragrances. Experts emphasized that olfactory identity arises from both designed essences and the intrinsic odors of materials, reaffirming the agency of matter in sensory composition. They also highlighted the need for responsible sourcing and ecological transparency, encouraging the use of renewable or certified ingredients in accordance with IFRA, FSC, and Ecocert guidelines. Through these discussions, the OAC emerges not merely as a creative system but as a tool that integrates ethical responsibility, environmental awareness, and design intentionality.

Overall, the research demonstrates that congruent multisensory combinations enhance emotional resonance, memorability, and spatial coherence, whereas incongruent pairings often generate confusion or cognitive dissonance. The OAC advances this understanding by providing a structured approach through which sensory correspondences can be reasoned, articulated, and tested—ensuring that olfactory and chromatic decisions remain perceptually grounded, culturally contextualized, and conceptually coherent. It should, however, be understood as a conceptual pilot: an initial methodological approach open to refinement and empirical validation rather than a finalized or prescriptive model.

The study’s outputs are summarized below (see

Table 7), highlighting the OAC’s methodological, ethical, and creative contributions to multisensory design.

7.1. Limitations

Several constraints qualify the interpretation of these findings. First, the interview base is intentionally small (four individual interviews), favoring analytic depth over breadth; as a result, the evidence cannot be assumed to represent the wider field. Second, all interviewees self-identified as women. While this lends a valuable gendered vantage point on sensory practice, it narrows the range of social and professional perspectives captured. Third, the empirical component relies on a single, information-rich case study, which provides thick description but limits transferability to other organizational models, market segments, and cultural settings. Taken together, these factors suggest caution in generalizing the results and indicate clear priorities for subsequent work: enlarging and diversifying the interview sample, incorporating multiple contrasting cases, and testing the OAC across varied contexts to examine robustness and external validity.

7.2. Future Research Directions

Building on the conceptual foundation of this study, three main research paths are proposed: (1) Cross-cultural validation should test whether attribute–aroma–color correspondences remain stable or shift across different sensory repertoires; (2) Architectural and experiential integration can be examined through real-world applications in retail, hospitality, and exhibition design, evaluating how the OAC performs in complex sensory contexts; (3) Longitudinal and cognitive studies should explore how olfactory–chromatic congruence affects memory, emotion, and well-being over time, providing empirical grounding for the tool’s broader use in multisensory design research.

Beyond olfactory design, the methodological logic of the OAC may extend to other sensory domains. Attributes such as Soft/Hard could guide material and tactile selection; Delicate/Fragile might inform sound or light modulation; and flavor could be explored alongside color and scent to generate crossmodal coherence. In this sense, the OAC operates as an evolving orientation rather than a fixed system—an interpretive method that enables reasoned, inclusive, and context-sensitive sensory composition.

Ultimately, this study indicates that sensory design can mature from intuitive practice into a reflective, evidence-informed methodology. By uniting computational reasoning with human interpretation, the OAC advances a mode of design that is both systematic and attentive to lived experience—recognizing atmosphere as a site of embodied meaning where color, aroma, and language converge. It invites designers and researchers to approach multisensory composition not as decoration but as a disciplined, ethically attuned practice capable of shaping environments that are coherent, memorable, and genuinely human-centered.