Unpacking Shifts of Spatial Attributes and Typologies of Urban Identity in Heritage Assessment Post COVID-19 Using Chinatown, Melbourne, as a Case Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Heritage Assessment, a Value-Based Approach for Heritage Conservation

Urban-Heritage-Assessment Methods

2.2. Heritage Assessment: A Value-Based Approach for Heritage Conservation

Components of Urban Identity

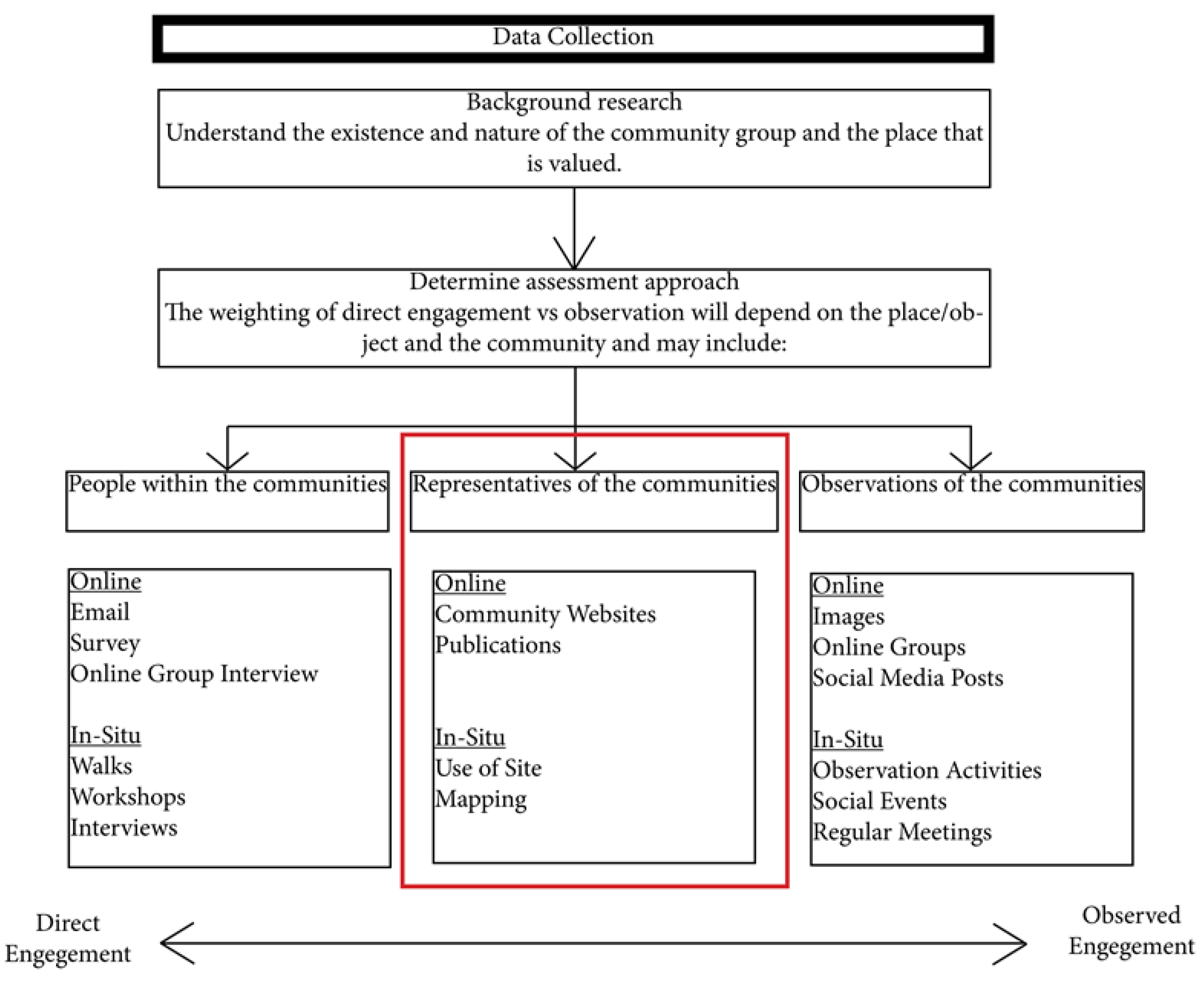

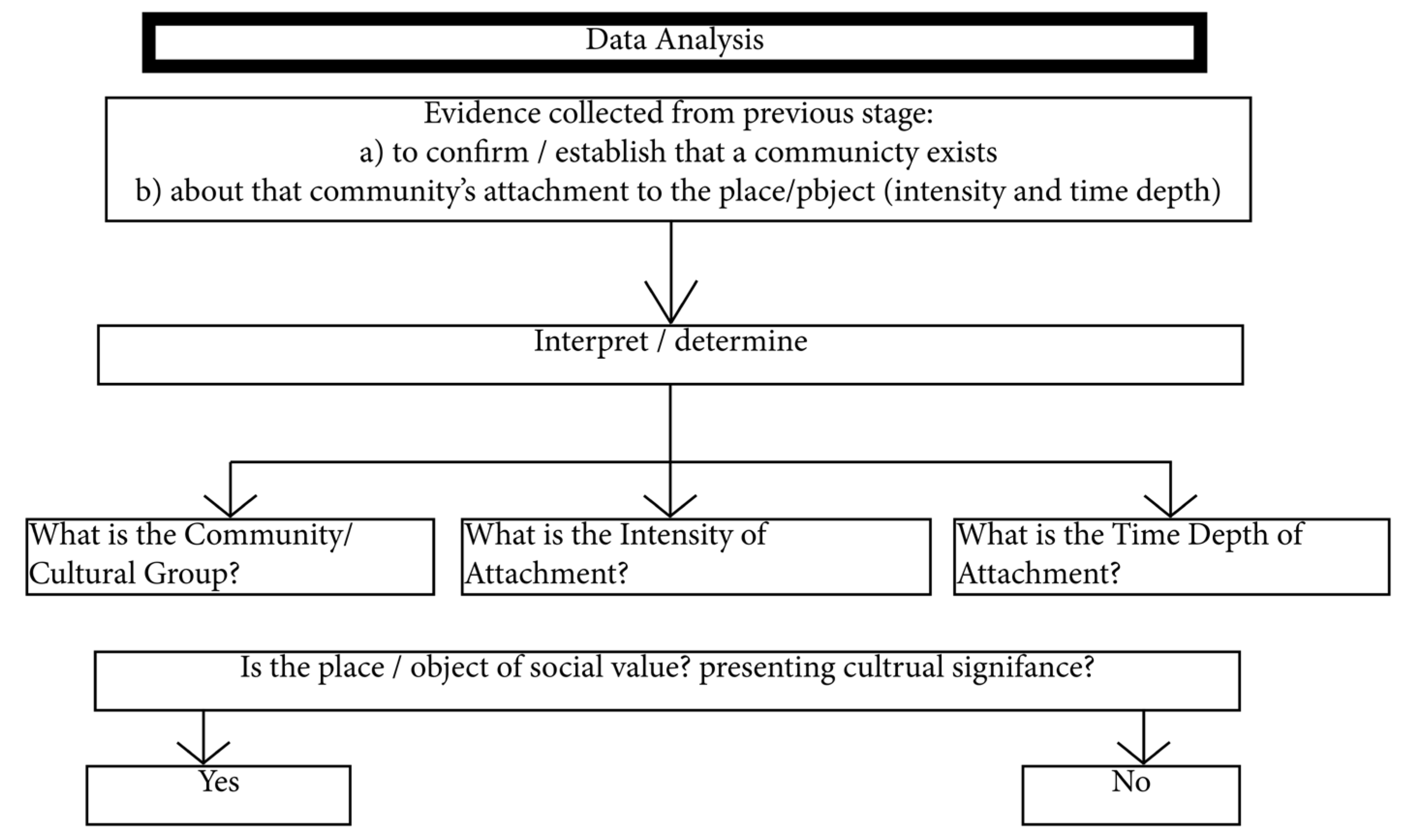

3. Materials and Methods

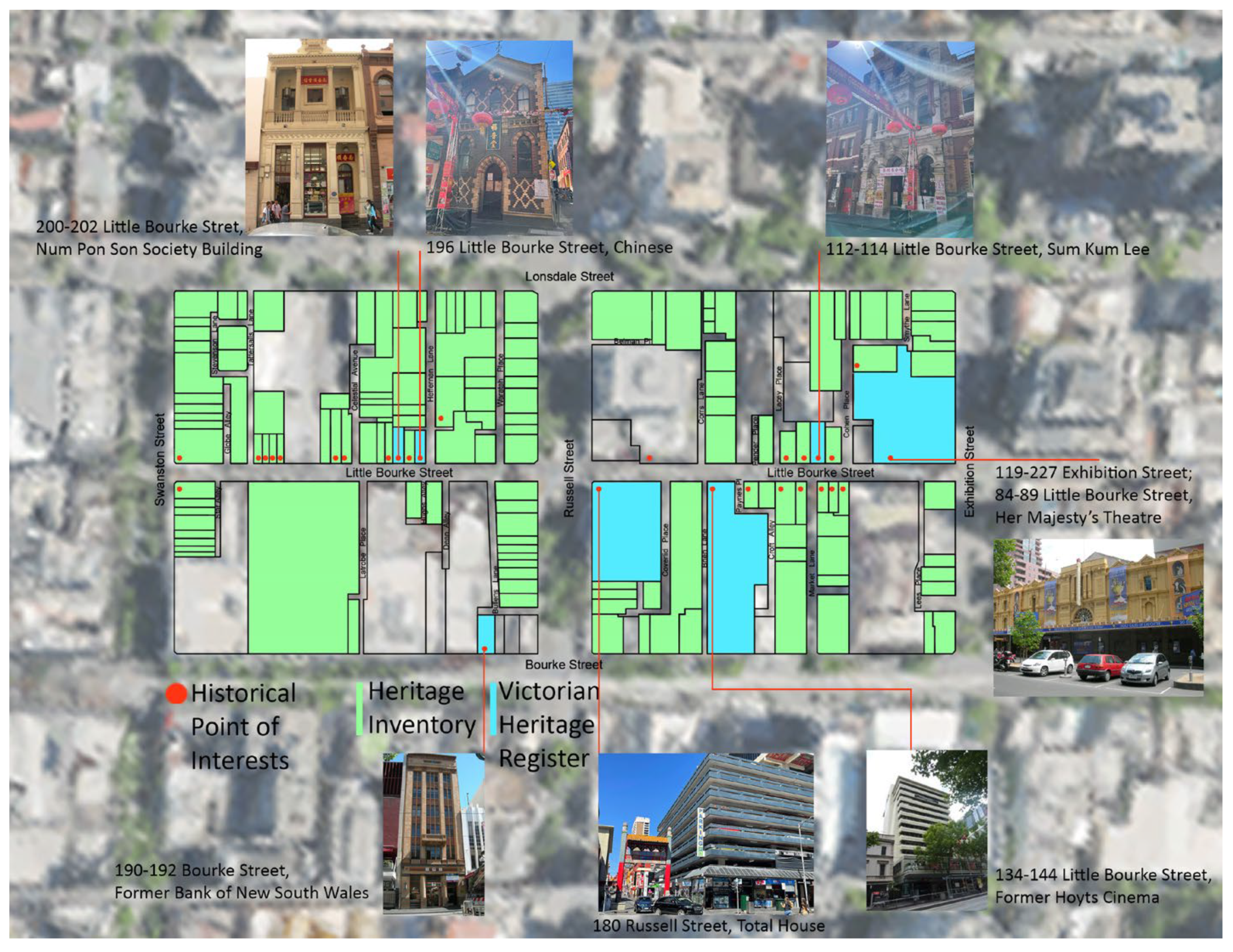

4. Case Study Results

4.1. What Is the Community/Cultural Group in the Precinct?

4.2. What Is the Intensity of Attachment?

4.3. What Is the Time Depth of Attachment?

5. Discussion

5.1. The Precinct’s Value and Identity Based on the HCV Framework

5.2. Aspects That the Current Framework Fails to Capture

5.3. A Magnifying Factor of the Identity Crisis of Chinatown, Melbourne: COVID-19

5.4. Suggestions for Future Framework

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gür, E.A.; Heidari, N. Challenge of Identity in the Urban Transformation Process: The Case of Celiktepe, Istanbul. A/Z ITU J. Fac. Archit. 2019, 16, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’ovo, M.; Dell’anna, F.; Simonelli, R.; Sdino, L. Enhancing the Cultural Heritage through Adaptive Reuse. A Multicriteria Approach to Evaluate the Castello Visconteo in Cusago (Italy). Sustainability 2021, 13, 4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linaki, E.; Serraos, K. Recording and Evaluating the Tangible and Intangible Cultural Assets of a Place through a Multicriteria Decision-Making System. Heritage 2020, 3, 1483–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrak, I. A Methodological Framework Based on the Dynamic-Evolutionary View of Heritage. Sustainability 2013, 5, 3992–4023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mualam, N.; Alterman, R. Architecture Is Not Everything: A Multi-Faceted Conceptual Framework for Evaluating Heritage Protection Policies and Disputes. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2020, 26, 291–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noardo, F.; Spanò, A. Towards a Spatial Semantic Management for the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Int. J. Herit. Digit. Era 2015, 4, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredheim, L.H.; Khalaf, M. The Significance of Values: Heritage Value Typologies Re-Examined. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2016, 22, 466–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolff, B. ‘Intangible’ and ‘Tangible’ Heritage—A Topology of Culture in Contexts of Faith. 2006. Available online: https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/76351468/34-libre.pdf?1639558481=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DIntangible_and_tangible_heritage.pdf&Expires=1701334972&Signature=ScVeLO3M17WGW9d1BBy0mp3LqJwkIre2I8LUDlRwbQdumw--seedqqGAQrnU2axIhfPUpb~YkQHr2t3A31MgW-zLoFpF0HYlK9Teh1iPJn3CBluBXsdrhrk70qnGVrtr6aSitz8cQ-tvCOK4O~O8eJ51FZ2s8xTSwTVhfxEAIXgk9rliLYEMMm~DAplyuSdA6TtMGTE6NfRSDxHQWeFyjSYanuHHLnLXaWuG-3REinnP1ieR1sfQ5piK07G03fQxeMp-Zh07XjFZD0D1DOnWAVUyngXUgTCJSJkShfT240oUDS58LHFMXeQ39NZTmyjlzq8DQm4HzGRUhKXYkMb~Ew__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Spennemann, D.H.R. The Shifting Baseline Syndrome and Generational Amnesia in Heritage Studies. Heritage 2022, 5, 2007–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Heritage in Urban Contexts: Impacts of Development Projects on World Heritage Properties in Cities; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Reher, G.S. What Is Value? Impact Assessment of Cultural Heritage. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 10, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, R. Assessing Values in Conservation Planning: Methodological Issues and Choices. In Assessing the Values of Cultural Heritage; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 6–30. [Google Scholar]

- Schuyler, J. Value-Focused Thinking: A Path to Creative Decisionmaking by Ralph L. Keeney Book Review. Informs 1993, 23, 140–142. [Google Scholar]

- Australia ICOMOS. The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance; Australia ICOMOS: Melbourne, Australia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Australia ICOMOS. The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance; Australia ICOMOS: Melbourne, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bandarin, F.; van Oers, R. The Historic Urban Landscape: Managing Heritage in an Urban Century; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; ISBN 9780470655740. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira Roders, A. Monitoring Cultural Significance and Impact Assessments. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual Meeting of the International Association for Impact Assessment, Calgary, AB, Canada, 13–16 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. The Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tutchener, D.; Kurpiel, R.; Smith, A.; Ogden, R. Taking Control of the Production of Heritage: Country and Cultural Values in the Assessment of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Significance. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2021, 27, 1310–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldpaus, L.; Pereira Roders, A.; Colenbrander, B. Urban Heritage: Putting the Past into the Future. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2013, 4, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, J. The Cultural Values Model: An Integrated Approach to Values in Landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 84, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, J. Time Honored: A Global View of Architectural Conservation; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Teutonico, J.M.; Palumbo, G. Management Planning for Archaeological Sites; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2002; Volume 43, ISBN 9780892366910. [Google Scholar]

- Girard, L.F.; Vecco, M. The “Intrinsic Value” of Cultural Heritage as Driver for Circular Human-centered Adaptive Reuse. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australia ICOMOS. The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance—Code on the Ethics of Co-Existence; Australia ICOMOS: Melbourne, Australia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Robles, L.G. A Methodological Approach Towards Conservation. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2010, 12, 146–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulios, I. Moving Beyond a Values-Based Approach to Heritage Conservation. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2010, 12, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, N. From Values to Narrative: A New Foundation for the Conservation of Historic Buildings. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2014, 20, 634–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanik, N.; Aalders, I.; Miller, D. Towards an Indicator-Based Assessment of Cultural Heritage as a Cultural Ecosystem Service—A Case Study of Scottish Landscapes. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 95, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Conceptualizing a Methodology for Cultural Heritage Futures: Using Futurist Hindsight to Make ‘Known Unknowns’ Knowable. Heritage 2023, 6, 548–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyke, J. Defining the Aesthetic Values of the Great Barrier Reef; Context Pty Ltd.: Melbourne, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dümcke, C.; Gnedovsky, M. The Social and Economic Value of Cultural Heritage: Literature Review by Cornelia Dümcke and Mikhail Gnedovsky. Eur. Expert Netw. Cult. 2013, 1, 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Djabarouti, J. Listed Buildings as Socio-Material Hybrids: Assessing Tangible and Intangible Heritage Using Social Network Analysis. J. Herit. Manag. 2020, 5, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, S.; Ostergren, G. Developing an Historic Thematic Framework to Assess the Significance of Twentieth-Century Cultural Heritage: An Initiative of the ICOMOS International Scientific Committee on Twentieth-Century Heritage. An Expert Meet. Hosted by Getty Conserv. Institute, Los Angeles, CA, May 10-11, 2011; Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Karlström, A. Urban Heritage; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; ISBN 9781441904652. [Google Scholar]

- Phetsuriya, N.; Heath, T. Defining the Distinctiveness of Urban Heritage Identity: Chiang Mai Old City, Thailand. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, N.; Davis, P. How Culture Shapes Nature: Reflections on Ecomuseum Practices Nunzia Borrelli and Peter Davis. Nat. Cult. 2012, 7, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, H.; Smith, C. Vestiges of Colonialism; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; ISBN 9780813034607. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. What Actually Is a Heritage Conservation Area? A Management Critique Based on a Systematic Review of New South Wales (Australia) Planning Documents. Heritage 2023, 6, 5270–5304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, G.T. Place-Making or Place-Claiming? Creating a “latino Quarter” in Oakland, California. Urban Des. Int. 2013, 18, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manahasa, E.; Manahasa, O. Defining Urban Identity in a Post-Socialist Turbulent Context: The Role of Housing Typologies and Urban Layers in Tirana. Habitat Int. 2020, 102, 102202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshmehzangi, A. Identity of Cities and City of Identities; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 85–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. The Image of The City. 1960. Available online: https://www.miguelangelmartinez.net/IMG/pdf/1960_Kevin_Lynch_The_Image_of_The_City_book.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture; Rizzoli: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Relph, E. Place and Placelessness; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, G. Concise Townscape; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Canter, D. V The Psychology of Place; Archit. Press Ltd.: London, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Hummon, D.M. City Mouse, Country Mouse: The Persistence of Community Identity. Qual. Sociol. 1986, 9, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshansky, H.M.; Fabian, A.K.; Kaminoff, R. Place-Identity: Physical World Socialization of the Self. J. Environ. Psychol. 1983, 3, 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauge, Å.L. Identity and Place: A Critical Comparison of Three Identity Theories. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2007, 50, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshmehzangi, A. Introduction to the Notion of Identity; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; ISBN 9789811539633. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Zoabi, A.Y. The Residents’ “images of the Past” in the Architecture of Salt City, Jordan. Habitat Int. 2004, 28, 541–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussaa, D. Urban Regeneration and the Search for Identity in Historic Cities. Sustainability 2017, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gospodini, A. Urban Morphology and Place Identity in European Cities: Built Heritage and Innovative Design. J. Urban Des. 2004, 9, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.J.C.; Xiang, B. Native Place, Migration and the Emergence of Peasant Enclaves in Beijing; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; Volume 155, pp. 546–581. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, P. Heritage Conservation in Australia: A Frame in Flux. J. Archit. Conserv. 2000, 6, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaymaz, I. Urban Landscapes and Identity. In Advances in Landscape Architecture; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ziyaee, M. Assessment of Urban Identity through a Matrix of Cultural Landscapes. Cities 2018, 74, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, J. Making a City: Urbanity, Vitality and Urban Design. J. Urban Des. 1998, 3, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punter, J. Developing Urban Design as Public Policy: Best Practice Principles for Design Review and Development Management. J. Urban Des. 2007, 12, 167–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. The Place-Shaping Continuum: A Theory of Urban Design Process. J. Urban Des. 2014, 19, 2–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jigyasu, R. The Intangible Dimension of Urban Heritage. In Reconnecting the City: The Historic Urban Landscape Approach and the Future of Urban Heritage; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Valera, S. Public Space and Social Identity. In Urban Regeneration—A Challenge for Public Art; Remesar, A., Ed.; Universitat de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, A. The Study of Spatial Quality. J. Aesthetic Educ. 1970, 4, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidance on Identifying Places and Objects of State-Level Social Value in Victoria. Available online: https://heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Guidance_IdentifyingStatelevelSocialValue-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Assessing the Cultural Heritage Significance of Places and Objects for Possible State Heritage Listing: The Victorian Heritage Register Criteria and Threshold Guidelines. Available online: https://heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/VHRCriteriaandThresholdsGuidelines_2019Final.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Geng, S.; Chau, H.-W.; Jamei, E.; Vrcelj, Z. Urban Characteristics, Identities, and Conservation of Chinatown Melbourne. J. Archit. Urban. 2023, 47, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, S.; Beynon, D. Master Planned Estates in Point Cook–the Role of Developers in Creating the Built-Environment. Aust. Plan. 2017, 54, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, S.; Beynon, D. Changing Neighbourhood Character in Melbourne: Point Cook a Case Study. J. Urban Des. 2018, 23, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, H.; Dupre, K.; Xu, B. Melbourne Chinatown as an Iconic Enclave. In Proceedings of the 13th Australasian Urban History Planning History Conference, Gold Coast, Australia, 31 January–3 February 2016; Bosman, C., Dedekorkut-Howes, A., Eds.; Australasian Urban History/Planning History Group and Griffith University: Gold Coast, Australia, 2016; pp. 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, K. ‘Chinatown Re-oriented’: A Critical Analysis of Recent Redevelopment Schemes in a Melbourne and Sydney Enclave. Aust. Geogr. Stud. 1990, 28, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, D.; Rahamathulla, M.; Pawar, M. The Impact and Implications of COVID-19: An Australian Perspective. Int. J. Community Soc. Dev. 2020, 2, 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, S.; Chau, H.W.; Jamei, E.; Vrcelj, Z. Understanding the Street Layout of Melbourne’s Chinatown as an Urban Heritage Precinct in a Grid System Using Space Syntax Methods and Field Observation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shircliff, J.E. Is Chinatown a Place or Space? A Case Study of Chinatown Singapore. Geoforum 2020, 117, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinatown Melbourne. Available online: https://chinatownmelbourne.com.au/ (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Major Chinatown Investment Enhances the Precinct. 2022. Available online: https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/news-and-media/Pages/Major-Chinatown-investment-enhances-the-precinct.aspx (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Hil, G.; Lawrence, S.; Smith, D. Remade Ground: Modelling Historical Elevation Change across Melbourne’s Hoddle Grid. Aust. Archaeol. 2021, 87, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnane, G. Fare Thee Well, Hoddle Grid; Clouds of Magellan: Melbourne, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Victorian Heritage Database. Available online: https://www.heritage.vic.gov.au/heritage-listings/is-my-place-heritage-listed (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Stobart, A.; Duckett, S. Australia’s Response to COVID-19. Health Econ. Policy Law 2022, 17, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacReadie, I. Reflections from Melbourne, the World’s Most Locked-down City, through the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond. Microbiol. Aust. 2022, 43, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Liu-Lastres, B. Consumers’ Dining Behaviors during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Application of the Protection Motivation Theory and the Safety Signal Framework. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 51, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kombanda, K.T.; Margerison, C.; Booth, A.; Worsley, A. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Young Australian Adults’ Food Practices. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2022, 6, nzac009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, L.M.; Hart, E.; McAleese, A.; Bastable, A.; Pettigrew, S. Factors Associated with Ordering Food via Online Meal Ordering Services. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 5704–5709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duval, M.; Smith, B.; Hœrlé, S.; Bovet, L.; Khumalo, N.; Bhengu, L. Towards a Holistic Approach to Heritage Values: A Multidisciplinary and Cosmopolitan Approach. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2019, 25, 1279–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elewa, A. Conserving Historical Areas through the Roles of Main Cities: Urban Identity in the Era of Globalisation. In Cities’ Identity Through Archit. Arts; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criterion A | Importance to the course, or pattern, of Victoria’s cultural history |

| Criterion B | Possession of uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of Victoria’s cultural history |

| Criterion C | Potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of Victoria’s cultural history |

| Criterion D | Importance in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of cultural places and objects |

| Criterion E | Importance in exhibiting particular aesthetic characteristics |

| Criterion F | Importance in demonstrating a high degree of creative or technical achievement at a particular period |

| Criterion G | Strong or special association with a particular present-day community or cultural group for social, cultural, or spiritual reasons |

| Criterion H | Special association with the life or works of a person, or group of persons, of importance in Victoria’s history |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Geng, S.; Chau, H.-W.; Jamei, E.; Vrcelj, Z. Unpacking Shifts of Spatial Attributes and Typologies of Urban Identity in Heritage Assessment Post COVID-19 Using Chinatown, Melbourne, as a Case Study. Architecture 2023, 3, 753-772. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture3040041

Geng S, Chau H-W, Jamei E, Vrcelj Z. Unpacking Shifts of Spatial Attributes and Typologies of Urban Identity in Heritage Assessment Post COVID-19 Using Chinatown, Melbourne, as a Case Study. Architecture. 2023; 3(4):753-772. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture3040041

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeng, Shiran, Hing-Wah Chau, Elmira Jamei, and Zora Vrcelj. 2023. "Unpacking Shifts of Spatial Attributes and Typologies of Urban Identity in Heritage Assessment Post COVID-19 Using Chinatown, Melbourne, as a Case Study" Architecture 3, no. 4: 753-772. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture3040041

APA StyleGeng, S., Chau, H.-W., Jamei, E., & Vrcelj, Z. (2023). Unpacking Shifts of Spatial Attributes and Typologies of Urban Identity in Heritage Assessment Post COVID-19 Using Chinatown, Melbourne, as a Case Study. Architecture, 3(4), 753-772. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture3040041