Abstract

The cannabinoid receptor type 2 (CB2) is increasingly recognized as a crucial regulator of neuroimmune balance in the brain. In addition to its well-established role in immunity, the CB2 receptor has been identified in specific populations of neurons and glial cells throughout various brain regions, and its expression is dynamically increased during inflammatory and neuropathological conditions, positioning it as a potential non-psychoactive target for modifying neurological diseases. The expression of the CB2 gene (CNR2) is finely tuned by epigenetic processes, including promoter CpG methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs, which regulate receptor availability and signaling preferences in response to stress, inflammation, and environmental factors. CB2 signaling interacts with TRP channels (such as TRPV1), nuclear receptors (PPARγ), and orphan G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs, including GPR55 and GPR18) within the endocannabinoidome (eCBome), influencing microglial characteristics, cytokine production, and synaptic activity. We review how these interconnected mechanisms affect neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders, underscore the species- and cell-type-specificities that pose challenges for translation, and explore emerging strategies, including selective agonists, positive allosteric modulators, and biased ligands, that leverage the signaling adaptability of the CB2 receptor while reducing central effects mediated by the CB1 receptor. This focus on the neuro-centric perspective repositions the CB2 receptor as an epigenetically informed, context-dependent hub within the eCBome, making it a promising candidate for precision therapies in conditions featuring neuroinflammation.

1. Introduction

It is now accepted that the endocannabinoid system (ECS) is a sophisticated and evolutionarily preserved lipid signaling network that regulates various physiological and pathological processes, encompassing immune surveillance, inflammation, energy balance, emotional regulation, pain perception, and synaptic transmission. Throughout history, cannabis has been utilized by ancient civilizations for its pain-relieving and therapeutic benefits. However, it was only in the mid-20th century that the compounds derived from cannabis were identified structurally, leading to the structure elucidation of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) as the primary active components of Cannabis sativa [1,2]. A pivotal advancement occurred with the uncovering of endogenous cannabinoids anandamide (N-arachidonoyl-ethanolamine; AEA) and 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol (2-AG), alongside their corresponding receptors, CB1 receptor and CB2 receptor, as well as the enzymes responsible for their synthesis and degradation, such as N-acyl phosphatidylethanolamine-specific phospholipase D (NAPE-PLD), diacylglycerol lipase (DAGLα/β), fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH), and monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) (reviewed in [3,4]). CB1 receptors are highly represented in the central nervous system (CNS), primarily mediating the psychoactive effects of THC and regulating neurotransmitter release [5,6]. Conversely, the CB2 receptor was initially cloned in the myelocytic cell line HL60 and identified as a peripheral receptor in immune tissues, such as the spleen, tonsils, and circulating leukocytes [5,7,8]. This system functions as a precisely regulated homeostatic network, activated as needed in response to stress, injury, or immune challenges [3]. The CB2 receptor has attracted significant interest due to its non-psychoactive characteristics and diverse immunomodulatory roles (reviewed in [9,10]). In basic and translational studies, researchers are actively investigating its functions in inflammation, immune cell movement, mood regulation, neurodegeneration, and cancer immunity.

As the understanding of CB2 receptor dynamics deepens, including its inducible expression, cell-type specificity, and distinct signaling capabilities, there is growing interest in leveraging its potential for therapeutic intervention. Although several excellent reviews cited above have addressed the CB2 receptor in the context of inflammation or cancer, none have systematically synthesized how epigenetic and transcriptional regulation intersect with disease-specific immune contexts. Accordingly, this review outlines the biology and regulation of the CB2 receptor, then synthesizes its roles in immune modulation, disease contexts (including autoimmune, neuropsychiatric, and cancer), and emerging checkpoint-like functions, before discussing therapeutic strategies. It uniquely emphasizes how genetic, epigenetic, and environmental cues converge to shape CB2 receptor expression and function, positioning it as a context-sensitive hub. By consolidating findings from transcriptomic studies, knockout models, and emerging pharmacological tools, this article aims to reframe the CB2 receptor as a precision-modulated therapeutic target within the broader endocannabinoidome (eCBome) network.

2. Molecular Biology of the CB2 Receptor

The CB2 receptor is encoded by the CNR2 gene in humans, which is located on chromosome 1p36 [8,11]. The typical isoform consists of a protein composed of 360 amino acids, featuring seven transmembrane α-helices that are characteristic of class A GPCRs, with an extracellular N-terminus that plays a role in ligand binding and an intracellular C-terminal domain essential for signaling and receptor trafficking. The CB2 receptor shares around 44% sequence homology with the CB1 receptor but displays expression patterns and pharmacological characteristics that vary by tissue and species [8]. Notably, the CB2 receptor exhibits 82% sequence similarity between humans and rodents; however, there are species-specific differences in expression and function that must be considered when interpreting preclinical results [11,12,13]. Recently, a comprehensive transcriptomic analysis of human peripheral leukocytes revealed that CB2 receptor mRNA is significantly expressed in granulocytes (neutrophils and eosinophils) and PBMCs (monocytes, B and T lymphocytes) [5,7]. This receptor can also be found in stem cells derived from bone marrow and various epithelial and endothelial tissues. In the brain, the CB2 receptor has been identified in particular regions, including the hippocampus, substantia nigra, cortex, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex [14,15,16].

3. Epigenetic and Transcriptional Regulation of the CB2 Receptor

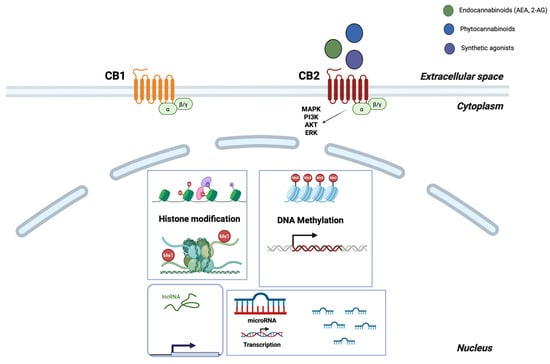

The regulation of the CNR2 gene through epigenetic processes is crucial for modulating CB2 receptor expression in response to cellular stimuli. Different layers of epigenetic control, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs, regulate the accessibility and transcriptional activity of the CNR2 region. These processes not only calibrate receptor expression but also enable the CB2 receptor to adjust its roles in line with physiological demands [17,18,19].

A key mechanism influencing CB2 receptor expression is the methylation of DNA at CpG-rich regions within the CNR2 promoter. In the absence of inflammation, DNA methyltransferases (DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B) add methyl groups to cytosines in these CpG islands [20,21,22,23]. This methylation inhibits gene transcription primarily through two means: (1) it directly obstructs transcription factor binding, and (2) it recruits methyl-CpG-binding proteins (MeCP) like methyl-CpG-binding protein 2(MeCP2). MeCP2 then acts as a platform to attract histone deacetylases (HDACs) and chromatin remodeling complexes, which compact the chromatin and maintain a transcriptionally inactive state [24,25,26,27,28,29]. Environmental factors, such as inflammation, infection, psychological stress, or exposure to cannabinoids, can also trigger ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes (TET1, TET2, and TET3), which convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. This modification promotes a shift toward a more open chromatin state, creating a permissive environment for gene transcription, which may include reactivation of the CNR2 gene under appropriate cellular conditions [23,30].

Enhancing histone marks, such as acetylation of histone H3 at lysine 9 (H3K9ac) and trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 (H3K4me3), are closely linked to open chromatin and active gene transcription. These activating changes are facilitated by enzymes such as CREB-binding protein/E1A binding protein p300 (CBP/p300), a group of transcriptional coactivators crucial for regulating gene expression, and mixed lineage leukemia (MLL) family methyltransferases, also known as the lysine methyltransferase 2 (KMT2) family [31,32]. Their activity is frequently stimulated by pro-inflammatory signals, immune activation, or engagement of the CB2 receptor, which kick-starts downstream signaling pathways such as mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (PKB, also known as AKT) [20]. These pathways further enhance the recruitment of co-activators and transcription factors to the CNR2 promoter, boosting gene expression [33,34]. Conversely, repressive histone marks, such as Histone H3 lysine 9 dimethylation (H3K9me2) and Histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3), are introduced by histone methyltransferases, such as histone H3 Lys-9 methyltransferase (G9a) and Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2), respectively, the primary components of the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) [35]. Non-coding RNAs add a layer of regulatory complexity to the expression of the CB2 receptor. MicroRNAs (miRNAs), such as miR-139 and miR-665, have been identified as binders to the 3′ untranslated region (3′ UTR) of CNR2 mRNA, inhibiting translation under resting conditions (Figure 1) [36].

Figure 1.

The epigenetic overview of CB2 receptor regulation. Ligand-activated CB2 (CB1 is shown for reference only) couples to Gi/βγ, engaging the MAPK/ERK and PI3K-AKT pathways. CNR2 expression is regulated in the nucleus by histone modifications (activating versus repressive marks), promoter CpG methylation, and non-coding RNAs (miRNA/lncRNA), which control transcription and mRNA stability. Endocannabinoids (green), phytocannabinoids (blue), and synthetic agonists (purple) are depicted at the receptor, and arrows represent activation or regulatory directionality. Created in BioRender. Kalkan, H. (2025) https://BioRender.com/oyx2kwj.

In cases of chronic heart failure, there is a notable increase in CB2 receptor expression within human heart muscle tissue, indicating a possible adaptive mechanism involving the endocannabinoid system. Weis et al. (2010) found that levels of CB2 receptor mRNA were significantly elevated in the myocardium of left ventricular failure, while CB1 receptor expression showed a slight decline [37]. This shift in receptor expression was correlated with a considerable increase in circulating endocannabinoids, indicating an overall activation of the endocannabinoid system. Similarly, Möhnle et al. (2014) demonstrated that miR-665 functions as a post-transcriptional regulator of the CB2 receptor [38]. Their research indicated that miR-665 was notably downregulated in heart tissue samples from patients with heart failure and predicted to target the 3′ UTR of CNR2 mRNA. The negative correlation observed between miR-665 and CB2 receptor expression suggests a regulatory mechanism in which lower levels of miR-665 may alleviate the translational inhibition of CB2 receptor, thereby promoting increased receptor expression. Collectively, these results highlight a coordinated mechanism in which modulation of miRNA and heightened endocannabinoid activity may facilitate CB2 receptor-mediated responses as a compensatory adaptation in the failing heart.

4. CB2 Receptor Pharmacology

The pharmacological and signaling heterogeneity associated with cannabinoid receptors, particularly the CB2 subtype, underscores the complexity of predicting biological outcomes based solely on receptor binding affinity. Selective CB2 agonists, such as dimethylbutyl-deoxy-delta-8-THC (JWH-133), JWH-015, Onternabez (HU-308), and WIN55,212-2, exemplify this diversity, as do mixed cannabinoid agonists and endogenous mediators. Variations in potency and efficacy observed across different experimental assays and cellular contexts may be attributed to the inherent flexibility of the CNR2 locus, alongside the capacity of downstream transcriptional machinery to activate CB2-receptor-dependent signaling pathways effectively. This intricacy underscores the necessity for a nuanced understanding of cannabinoid pharmacology, particularly in relation to various tissues and pathological states (Table 1).

Table 1.

Representative CB1 and CB2 receptor ligands with binding affinities and pharmacological profiles. This table highlights commonly used synthetic and endogenous ligands at CB1 and CB2 receptors. Selective agonists such as JWH-133, JWH-015, and HU-308 are key tools for CB2-receptor focused studies, while WIN55,212-2 (WIN) serves as a non-selective reference agonist. Endogenous ligands AEA and 2-AG are included as physiological benchmarks, despite their rapid enzymatic breakdown.

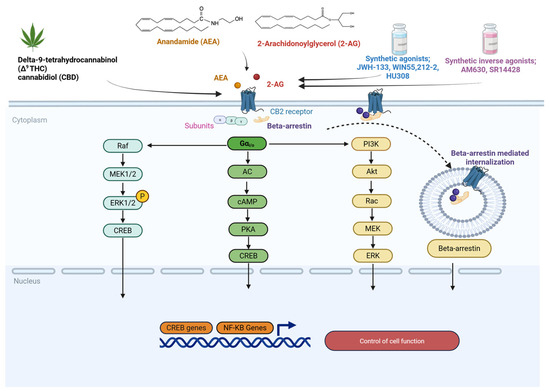

When activated by endogenous ligands (AEA, 2-AG) or synthetic compounds such as JWH-133, WIN, and/or HU-308, CB2 receptors associate with G protein alpha subunit (Gαi/o) proteins, leading to the inhibition of adenylyl cyclase, decreased cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) synthesis, and subsequent suppression of Protein Kinase A (PKA) [14]. Beyond traditional G protein signaling, CB2 receptors also interact with β-arrestin pathways, which are responsible for receptor internalization, desensitization, and alternative signaling routes, including ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, and PI3K/Akt, and activate transcription of cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-KB) genes to control cellular functions (Figure 2 and [9]). Evidence of ligand-biased signaling has shown that different ligands can preferentially engage either G protein or β-arrestin pathways, allowing for pharmacological fine-tuning. Allosteric modulation is another mechanism modulating CB2 receptor activity selectively [44]. PAMs, such as the 2-oxopyridine-3-carboxamide derivative (EC21a) and endogenous peptides like RVD-hemopressin (Pepcan-12), increase the sensitivity of CB2 receptors to endogenous cannabinoids without acting as direct agonists, thereby preserving physiological signaling dynamics [44,45,46]. Conversely, negative allosteric modulators (NAMs) can diminish receptor activity and may provide therapeutic advantages in conditions involving excessive CB2 receptor activation [47]. CB2 receptors also undergo post-translational modifications, including glycosylation and phosphorylation, which influence receptor transport, localization, and the accuracy of signaling. G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) and β-arrestins regulate receptor desensitization and recycling. In contrast, receptor dimerization with the CB1 receptor or other GPCRs introduces another layer of functional complexity.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of CB2 receptor structure, distribution, and signaling pathways. CB2 activation is associated with Gαi/o-dependent inhibition of AC and Gβγ-mediated activation of MAPK signaling cascades, which regulate immune responses, inflammation, and gene expression. Endocannabinoids (AEA, 2-AG), phytocannabinoids (Δ9-THC, CBD), synthetic agonists, and inverse agonists are shown in distinct colors for clarity, and arrows denote the direction of signaling flow or regulatory effects. Kalkan, H. (2025) https://BioRender.com/1drpvb8.

5. The Role of CB2 Receptor in Immune Regulation

The CB2 receptor serves as a crucial modulator of both innate and adaptive immune responses. The activation of the CB2 receptor results in the inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), while it encourages the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-10 and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) [6]. Additionally, the CB2 receptor influences inflammasome activation and the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which contributes to its documented anti-inflammatory characteristics [9,10]. CB2 receptor signaling promotes the macrophage phenotype 2 (M2) in monocytes and macrophages over the macrophage phenotype 1 (M1) [48]. M2 macrophages that CB2 receptor agonists stimulate display increased phagocytic ability and diminished antigen presentation, both of which are vital for resolving inflammation and conducting tissue repair [49]. In dendritic cells (DCs), activation of the CB2 receptor decreases the expression of major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) and co-stimulatory molecules, cluster of differentiation 80 and 86 (CD80, CD86), which hinders maturation and reduces their capacity to activate naïve T cells [50]. These consequences produce a tolerogenic DC phenotype that lessens T-cell activation and promotes immune resolution. The ability of CB2 receptors to inhibit the migration of dendritic cells to lymph nodes through the downregulation of CC chemokine receptor type 7 (CCR7) and changes in cytoskeletal structures further limits immune amplification. T lymphocytes exhibit low baseline expression of the CB2 receptor, but this expression can increase upon activation. In the latter study, it has been demonstrated that CB2 receptor signaling in CD4 + T helper cells (CD4 + T cells) appears to restrict proliferation and differentiation into T helper 1 cells (Th1) and T helper 17 cells (Th17) subsets while encouraging the development of regulatory T cells (Tregs) [51]. This immunosuppressive action is partially facilitated by reducing the secretion of interleukin-2 (IL-2), IFN-γ, and interleukin-17 (IL-17), as well as modulating transcription factors like T-box expressed in T cells (T-bet) and RAR-related orphan receptor gamma t (RORγt) [52,53,54]. In conclusion, the CB2 receptor orchestrates a complex immunoregulatory program, and precisely targeting the CB2 receptor with selective modulators, PAMs, or biased ligands presents a novel strategy for adjusting immune function without broadly suppressing host immunity.

6. CB2 Receptor and Microglia in Neuroinflammation

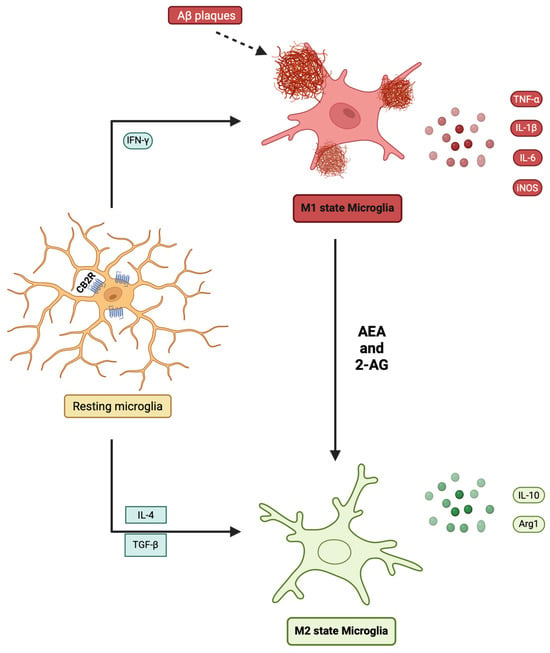

Microglia, the brain’s resident macrophages, are crucial for preserving CNS homeostasis and managing immune responses during injury and disease. In a healthy brain, microglia exhibit a surveying state characterized by branching shapes and minimal expression of inflammatory proteins [55]. When faced with pathological triggers such as infection, trauma, or neurodegeneration, microglia quickly transform morphologically and functionally into reactive states, such as M1 or M2. Although this M1/M2 classification is somewhat simplistic, it serves as a helpful conceptual framework for understanding immune polarization in the CNS. Notably, the CB2 receptor participates in regulating this polarization process [56]. Mechanistically, activating the CB2 receptor can prevent the nuclear translocation of NF-κB, diminish MAPK pathway activation, and modulate the production of ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), thereby dampening the pro-inflammatory signaling cascade at several levels [57].

Recent studies conducted both in vivo and in vitro support the role of the CB2 receptor in modulating the microglial phenotype, for instance, activation of the CB2 receptor, as evidenced by decreased expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and increased levels of arginase-1 (Arg-1) (Figure 3) [58,59,60,61]. In models of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), traumatic brain injuries, and stroke, pharmacological stimulation of CB2 receptors has lessened neuroinflammation, reduced neuronal death, improved cognitive functioning, and minimized gliosis [62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70]. In conditions like neuropathic pain and multiple sclerosis (MS), CB2 receptor signaling has been found to reduce neurotoxicity caused by microglia and promote remyelination. Consistent with a microglia-centric view of CB2 in CNS inflammation, two reporter/knockout studies in Alzheimer’s models localize the inducible CB2 pool to plaque-associated microglia and probe its functional impact. Using CB2EGFP/f/f reporter mice (Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (EGFP) under the CNR2 promoter) and 5xFAD mice co-expressing five familial Alzheimer’s Disease mutations, crossing (CB2EGFP/f/f/5xFAD), López et al. (2018) showed that the CB2 signal is low in the healthy brain but robustly upregulated by intense inflammation and amyloid deposition in microglia clustered around amyloid plaques; significantly, global CB2 deletion in CB2−/−/5xFAD mice reduced plaque burden and glial reactivity, indicating that disease-induced CB2 is not uniformly protective in vivo [71].

Figure 3.

Endocannabinoid-mediated regulation of microglial polarization. Resting microglia can be activated toward an M1 state by stimuli such as IFN-γ or Aβ plaques, leading to the secretion of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and iNOS, which exacerbate neuroinflammation. Alternatively, microglia may polarize toward an M2 state under the influence of IL-4 and TGF-β, characterized by increased IL-10 and Arg1, which promotes the resolution of inflammation. Endocannabinoids, including AEA and 2-AG, acting via CB2 receptors, facilitate the shift from the M1 phenotype toward the M2 phenotype. Created in BioRender. Kalkan, H.(2025) https://BioRender.com/nhx8d66.

Extending this, Esteban S. et al. in 2022 combined CB2EGFP/f/f, CB2−/−, and 5xFAD lines (CB2EGFP/f/f/5xFAD and CB2−/−/5xFAD) using microglia, and demonstrated that loss of CB2 blunts microglial phagocytosis and p38-MAPK activation in vitro, alters plaque-proximal microglial phenotypes in vivo, and, consistent with López et al., is accompanied by fewer methoxy-X04+ plaques in 5xFAD/CB2−/− brains [72]. The authors highlighted a crucial function of cannabinoid CB2 receptors in microglial activities and the metabolism of β-amyloid peptide (Aβ) within an animal model of AD (5xFAD). They discovered that the lack of CB2 receptors reduces both the overall number of microglial cells and their capacity to engulf Aβ, as well as having a regulatory effect on the build-up of the insoluble form of this harmful peptide. Their findings imply that microglial CB2 receptors might be continually activated in the context of Alzheimer’s Disease, as evidenced by the phosphorylation state of p38 MAPK.

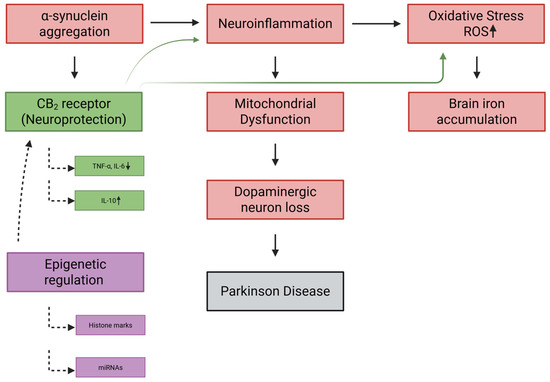

In Parkinson’s disease, the CB2 receptor has been repeatedly implicated in neuroinflammation and dopaminergic neuron protection, and elevated levels of brain iron [73,74,75]. Experimental models demonstrate that the CB2 receptor is markedly upregulated in activated microglia of the substantia nigra, and its stimulation reduces neurotoxin-induced damage [76]. For example, in MPTP-treated mice, selective CB2 receptor agonists decreased microglial activation and preserved dopaminergic neurons, whereas CB2 receptor deletion exacerbated neuronal loss and motor impairment [77]. Similar neuroprotection has been observed with CB2 receptor activation in 6-OHDA and Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) models of Parkinson’s disease, where treatment suppressed pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β) and enhanced anti-inflammatory mediators, such as IL-10 [78]. Positron emission tomography studies using CB2 receptor ligands have further confirmed the dynamic upregulation of CB2 receptors in microglial populations during Parkinson’s disease progression, reinforcing its translational relevance [79]. Although direct evidence linking CB2 receptor signaling to epigenetic regulation in Parkinson’s disease is still scarce, emerging data from related neuroinflammatory contexts point to potential mechanisms. Together, these findings suggest that CB2 receptor contributes to Parkinson’s disease pathology not only via receptor signaling but also potentially through epigenetic feedback loops that govern inflammatory and neuroprotective gene programs (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

CB2 receptor and epigenetic regulation in Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Pathological hallmarks of Parkinson’s disease include α-synuclein aggregation, neuroinflammation, oxidative stress (↑ ROS), mitochondrial dysfunction, brain iron accumulation, and progressive dopaminergic neuron loss. These processes form a feed-forward cascade culminating in neurodegeneration and disease manifestation. The CB2 receptor exerts neuroprotective actions by dampening microglial activation (↓ TNF-α, IL-6; ↑ IL-10), reducing oxidative stress, preserving mitochondrial function, and limiting neuronal injury. Epigenetic mechanisms, including histone modifications and miRNAs, regulate CB2 receptor expression and inflammatory gene programs, providing an additional layer of control. Together, CB2 signaling and its epigenetic modulation represent a therapeutic axis that may counteract key drivers of Parkinson’s disease’s progression. Created in BioRender. Kalkan, H. (2025) https://BioRender.com/jm31uj9.

7. CB2 Receptor in Depression and Psychiatric Disorders

Depression is increasingly acknowledged as a complex disorder involving the neuroimmune system, marked by a subtle interaction between chronic inflammation, improper stress response regulation, reduced neuroplasticity, and altered microglial cell activity. Elevated concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, are frequently found in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid of individuals with depression [80]. These cytokines interfere with neurotransmission by decreasing serotonin production through the indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO-mediated metabolism of tryptophan), hindering neurogenesis in the hippocampus, and enhancing excitotoxicity [81]. Furthermore, chronic stress triggers the activation of microglia and immune cells, leading to a systemic inflammatory response that worsens neurobiological impairments. Research has shown increased levels of CB2 receptor expression in brain tissues and immune cells of animal models and humans with major depressive disorder [82]. Activation of the CB2 receptor has been found to alleviate excessive hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis activity, likely by reducing both central and peripheral inflammation. CB2 receptor signaling diminishes the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines that typically contribute to hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis hyperactivity [83]. Importantly, CB2 receptors may serve a dual role by regulating cytokine release from immune cells and inhibiting neuronal hyperexcitability in stress-sensitive regions such as the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex [84]. Pharmacological stimulation of CB2 receptors has been shown to normalize serum corticosterone levels, diminish glial reactivity, and restore expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), all of which are crucial for mood regulation and synaptic plasticity [85].

Transcription factors such as nuclear erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF-2), NF-κB, and Activator Protein-1 (AP-1) have been associated with the regulation of the CB2 receptor gene. NRF-2 connects oxidative stress responses with the activation of the CB2 receptor [86]. When exposed to stress, the translocation of these transcription factors to the nucleus can trigger the transcription of CNR2, suggesting a dynamic interaction among redox status, inflammation, and cannabinoid signaling [29]. MeCP2 plays a key role in maintaining the CNR2 gene in a transcriptionally repressed state under homeostatic conditions [87]. This binding is crucial for the action of inhibitors (SNRIs), which modulate the inflammatory environment and thereby diminish the effectiveness of monoamines [88]. Overall, the CB2 receptor acts as a link between the immune system and CNS functions by modulating inflammation, releasing stress hormones, synaptic adaptability, and glial responsiveness.

8. CB2 Receptor in Chronic Pain and Neuropathy

Chronic pain is a complex condition affecting millions around the world, often resulting from prolonged tissue damage, nerve injury, or disrupted neuroimmune signaling. It includes various types, such as inflammatory pain, pain related to cancer, and neuropathic pain [89]. Neuropathic pain occurs due to injuries or dysfunctions in the somatosensory system and often proves resistant to traditional pain relievers like nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or opioids [89,90]. After a nerve injury, peripheral immune cells, such as macrophages and neutrophils, move into the site of injury, releasing pro-inflammatory substances like IL-6, TNF-α, and prostaglandins. These mediators make nociceptors more sensitive by altering ion channels and increasing receptor expression at the peripheral ends [91]. At the same time, microglia and astrocytes in the spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia (DRG) become active, and this interaction between glial and neuronal cells maintains central sensitization and allodynia. Significantly, following peripheral nerve injury, CB2 receptor expression rises in DRG macrophages, spinal microglia, and astrocytes [92,93,94,95,96,97,98]. This increase makes the CB2 receptor a potential molecular regulator that can help control excessive neuroimmune activation, as previously suggested [99]. Studies conducted in preclinical settings using CB2 receptor agonists, such as JWH-133, AM1241, and BCP, have exhibited significant reductions in mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia [39,90,100,101,102]. In both spinal cord slices and in vivo models, the administration of CB2 receptor agonists or the overexpression of the CB2 receptor has been shown to decrease excitatory neurotransmission by inhibiting glutamate release and restricting synaptic facilitation at dorsal horn neurons [83]. Concurrently, CB2 receptor activation boosts inhibitory GABAergic and glycinergic signaling, thereby restoring the excitatory-inhibitory balance disrupted in chronic pain conditions. Notably, inhibiting MAGL not only increases the levels of 2-AG but also reduces the production of prostaglandins, thereby further enhancing pain relief [103]. Strategies that combine CB2 receptor agonists with FAAH inhibitors have shown enhanced analgesic effects, highlighting the significance of endogenous ligand support for the control mediated by CB2 receptor. Phytocannabinoids, such as CBD and cannabigerol (CBG), exhibit anti-inflammatory and pain-relieving effects, which are often partially mediated through CB2 receptor signaling [104]. CBG functions as a weak antagonist of the CB1 receptor and a partial agonist of the CB2 receptor while also interacting with TRP channels and α2-adrenergic receptors [105,106,107]. In models of neuropathic pain, CBG alleviates hypersensitivity and mitigates the effects of microglial activation, which are reversed by CB2 receptor antagonists, indicating its dependence on CB2 receptors. The combination of CBD and CBG exhibits synergistic effects, likely resulting from their joint action on CB2 receptors and TRP channels, as well as the suppression of cytokine release. Clinical investigations of balanced THC:CBD formulations such as nabiximols (Sativex®) have demonstrated effectiveness in treating neuropathic pain associated with multiple sclerosis, although the roles of the CB2 receptor compared to the CB1 receptor continue to be explored [108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116]. There is a scarcity of clinical trials targeting the CB2 receptor for pain management; however, selective ligands are beginning to undergo early-phase assessments. The limited expression of the CB2 receptor in disease-activated cells and the absence of CNS side effects underscore its potential as an appealing target for next-generation analgesics [117].

9. CB2 Receptor in Schizophrenia and Dopaminergic Circuits

Schizophrenia is a multifaceted neuropsychiatric condition marked by positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and cognitive impairments [118]. Studies in rodents have demonstrated that the CB2 receptor is present in both the tyrosine hydroxylase-positive neurons of the ventral tegmental area and medium spiny neurons expressing dopamine receptor 1 (D1) or dopamine receptor 2 (D2) in the nucleus accumbens [119,120,121,122]. The activation of CB2 receptors in these areas leads to decreased neuronal excitability and reduced dopamine release, indicating a role in regulating dopaminergic tone. The agonism of the CB2 receptor results in neuronal hyperpolarization within dopaminergic circuits, which is diminished after depolarization in key regions, such as the striatum and prefrontal cortex. Preclinical research utilizing a selective CB2 receptor agonist, JWH-133, has demonstrated that the activation of CB2 receptors inhibits the hyperactivity of ventral tegmental area’s dopamine neurons both in vitro and in vivo [121,122,123,124,125,126]. Microdialysis investigations indicate that the administration of CB2 receptor agonists into the nucleus accumbens significantly decreases extracellular dopamine levels, while CB2 receptor antagonist iodopravadoline (AM630) enhances dopaminergic activity [120,125]. These effects do not occur in CB2 receptor knockout mice, confirming the receptor specificity of the impact. This bidirectional modulation implies that CB2 receptor signaling likely establishes a negative feedback mechanism within mesolimbic circuits. As hyperdopaminergic activity in the striatum is linked to psychotic symptoms, the attenuation by CB2 receptor may serve to balance dopaminergic overactivity, presenting a potential mechanism for antipsychotic-like effects without the motor side effects associated with D2 antagonists.

Genetic research has further indicated the role of the CB2 receptor in schizophrenia [127]. Variations in the CNR2 gene, specifically single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), have been linked to an increased risk of psychosis, decreased CB2 receptor expression, and altered inflammatory gene networks [128,129]. For example, the gene variation rs35761398 (Q63R) polymorphism has been associated with reduced functionality of the CB2 receptor and increased susceptibility to stress-related behavioral traits [128,130,131]. In patients with schizophrenia, notable changes in DNA methylation patterns and histone modifications are observed at the CNR2 gene locus due to epigenetic factors [132,133,134,135,136,137]. Environmental stressors, infections, and toxins can also be recognized as risk factors for schizophrenia, which can trigger epigenetic alterations in CB2 receptor expression within the CNS. Also, elevated levels of IL-6 and TNF-α and activated microglia have been observed in both postmortem studies and in vivo imaging of individuals with schizophrenia [138,139,140]. In cases where the CB2 receptor is absent, studies in mice have shown worsened inflammatory reactions and behavioral abnormalities like those seen in schizophrenia, such as reduced prepulse inhibition, altered social behavior, and heightened locomotor activity in response to psychostimulants [141,142,143].

On the other hand, activating the CB2 receptor pharmacologically has been shown to reverse prepulse inhibition deficits caused by dizocilpine (MK-801) and restore abnormal dopamine signaling in models of schizophrenia [144]. In these models, the levels of 2-AG are frequently found to be increased, and the dysregulation of enzymes such as MAGL and FAAH leads to circuit imbalances [145,146,147]. Using biased CB2 receptor ligands or PAMs, for instance, EC21a, selectively promotes CB2 receptor-mediated anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive effects without fully activating the receptor, thereby minimizing potential side effects [148,149,150]. Considering the multifaceted causes of schizophrenia, approaches that target multiple pathways could prove to be effective. The convergence of cannabinoid signaling, immune system regulation, and synaptic plasticity positions the CB2 receptor as the most promising candidate in the field of psychopharmacology.

10. Crosstalk Within the eCBome

The eCBome, particularly the CB2 receptor, holds significant promise for developing innovative therapies targeting neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative conditions [66,67,83,122,151,152,153,154,155]. Targeting the CB2 receptor could help reestablish equilibrium in both neuronal and glial cells, thereby reducing degenerative and inflammatory damage. Consequently, modulating the CB2 receptor may represent a promising strategy for addressing complex neurodegenerative disorders and their effects in a dynamic epigenetic landscape, where current studies are limited [156]. The activity of CB2 receptors within the expanding concept of the eCBome does not function independently but collaborates with various signaling mechanisms, including TRP ion channels, nuclear receptors, and GPCRs [157]. This interconnected signaling framework captures the complexity of the roles of CB2 receptors across neuroimmune disorders.

One of the most significant interactions occurs between the CB2 receptor and TRPV1, a calcium-permeable ion channel that plays a vital role in pain signaling, oxidative stress, and immune response (reviewed in [158,159,160]). The CB2 receptor and TRPV1 are co-expressed in microglia, peripheral macrophages, and sensory neurons [77,161,162]. Evidence suggests that CB2 receptor activation can mitigate TRPV1-driven neuroinflammation by reducing calcium influx, ROS generation, and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α, in the progression of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s disease [77,163,164,165]. Additionally, phytocannabinoids such as CBD and CBG, which exhibit weak binding to the CB2 receptor, also act on TRP channels, displaying agonistic effects at TRPV1 and antagonistic effects at transient receptor potential melastatin subtype 8 (TRPM8), thereby enhancing the CB2 receptor’s contribution to an overarching anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory pathway [166,167]. This collaborative action underscores the potential for dual targeting of CB2 receptor and TRPV1 in developing innovative pain management strategies and neuroprotective treatments.

The CB2 receptor also exhibits a synergistic regulatory relationship with PPARγ, which regulates the expression of anti-inflammatory genes and mediates metabolic change [168]. Both endogenous and plant-derived cannabinoids, including AEA, palmitoylethanolamide (PEA), and oleoylethanolamide (OEA), interact with the CB2 receptor and PPARγ to shift macrophages toward the M2 phenotype, increase IL-10 levels, and inhibit NF-κB signaling [169,170,171,172,173]. In microglia, the interaction between the CB2 receptor and PPARγ supports neuroprotection by limiting excitotoxicity and facilitating the clearance of phagocytic debris [174,175].

Moreover, the CB2 receptor signaling interacts with orphan GPCRs, such as GPR55 and GPR18, which share endogenous ligands with the CB2 receptor [176]. GPR55 is a cannabinoid-responsive GPCR incorporated into the eCBome and engaged most robustly by the lysophospholipid lysophosphatidylinositol (LPI) [177]. In the brain, GPR55 is detected in neurons and microglia across the striatum, hippocampus, forebrain, cortex, and cerebellum [178,179]. In Alzheimer’s Disease tissues and models, GPR55 immunostaining is strongest in neurons, and exposure to Aβ42 increases neuronal GPR55 expression, providing evidence that the receptor is dynamically regulated in neurodegeneration [178]. At the mechanistic level, LPI-GPR55 drives RhoA-dependent Ca2+/NFAT signaling, providing a well-described route to transcriptional changes relevant to neuroinflammation and plasticity [180]. On the other hand, GPR18 has emerged as a microglia-facing GPCR within the broader eCBome, as it is expressed in microglia and other CNS cells [181]. It can be engaged by endogenous lipids derived from the endocannabinoid pathway, positioning it to couple immune tone with neuronal viability [182]. In organotypic hippocampal slice cultures subjected to NMDA excitotoxicity, the endogenous anandamide derivative N-arachidonoyl-glycine reduced neuronal damage, and this neuroprotection was prevented by pharmacological blockade of GPR18; the same study detected GPR18 mRNA/protein in microglia, astrocytes, and neurons and reported that N-arachidonoyl-glycine modulated glial activation states, indicating a glia-neuron mechanism of action [183]. In cultured microglia and heterologous GPR18 systems, N-arachidonoyl-glycine also drives directed migration and MAPK signaling at low nanomolar concentrations, responses consistent with a role in microglial motility [181]. Collectively, the CB2 receptor stands out as a crucial signaling hub within the eCBome, integrating immune, metabolic, and neuronal signals through various receptor interactions. Its actions in regulating immunity are amplified and refined through interactions with TRP channels, PPARs, and orphan GPCRs, creating a dynamic network that can finely adjust inflammation and immune resolution in the brain [184,185].

11. Conclusions

This review provides a detailed and integrative examination of the CB2 receptor, emphasizing its crucial role within the eCBome and its substantial contributions to neuroimmune regulation. Moving beyond the conventional perception of the CB2 receptor as merely a peripheral immune receptor, we emphasize its dynamic and inducible expression across microglia and its context-dependent upregulation within neuronal cells, underscoring its adaptability across both immune and non-immune landscapes. The CB2 receptor is notable for its inducible characteristics and the intricate regulatory frameworks that govern its expression, especially in the settings of immune activation, inflammation, and neuroimmune signaling. Its transcriptional control is tuned by a multilayered network of DNA- and RNA-based mechanisms, including promoter methylation, histone modifications, and the activity of non-coding RNAs. Understanding the specific epigenetic pathways involved could be crucial for grasping how endocannabinoids and cannabinoids affect inflammation in both neurological diseases. By identifying the exact epigenetic mechanisms that cannabinoids utilize to reduce inflammatory responses, scientists may discover new targets for preventing and treating a range of inflammatory and neurological disorders. This investigation not only enhances our understanding of the effects of cannabinoids on epigenetics but also has the potential to transform therapeutic approaches in addressing these complex conditions. The discussed epigenetic processes ensure CB2 receptor expression is precisely modulated in response to physiological demands or pathological stress, enabling it to shape immune cell behavior and inflammatory outcomes with high specificity. Beyond transcriptional control, CB2 receptor signaling exhibits functional versatility through mechanisms such as biased agonism, receptor dimerization, and interaction with complementary pathways. This signaling plasticity positions the CB2 receptor as a regulatory hub within the broader eCBome network. Framed within multiple pathological contexts, including neuroinflammation, depression, chronic pain, schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease, this review highlights how the CB2 receptor modulates the immune landscape by promoting regulatory over effector responses, reprogramming macrophage and microglial phenotypes, altering cytokine profiles, and influencing cell trafficking.

While preclinical studies provide strong evidence for the therapeutic potential of CB2 receptors, clinical translation faces several challenges, including species-specific differences in CB2 receptor biology, limited pharmacological selectivity, and the absence of predictive biomarkers for patient stratification. Nonetheless, emerging strategies such as allosteric modulation, biased ligand design, and polypharmacological approaches, particularly the co-targeting of CB2 receptor-PPARγ and CB2 receptor-TRPV1, are paving the way for more precise and effective therapeutic interventions.

In conclusion, the CB2 receptor functions as an inducible, epigenetically regulated node within the eCBome, serving as a precise and adaptable mechanism to adjust immune-neuronal interactions in the diseased brain. Significantly, the expression and coupling of CNR2 are influenced by chromatin status (including DNA methylation and histone modifications) and by the surrounding network, emphasizing that effective treatments need to consider both epigenetic factors and the eCBome. Collectively, these findings enhance our understanding of the CB2 receptor as a target not only for peripheral inflammatory modulation but also as a promising candidate for innovative therapies targeting immune-mediated and neurological disorders.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.K. and N.F.; investigation, H.K. and N.F.; resources, H.K. and N.F.; writing—original draft preparation, H.K. and N.F.; writing—review and editing, H.K. and N.F.; funding acquisition, H.K. and N.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant to N.F. from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (RGPIN-2021-03777). A post-doctoral fellowship from IUCPQ supported H.K.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 2-AG | 2-Arachidonoylglycerol |

| AEA | Anandamide (N-Arachidonoyl-Ethanolamine) |

| AKT/PKB | Protein Kinase B |

| Aβ | β-Amyloid Peptide |

| CB1 | Cannabinoid Receptor Type 1 |

| CB2 | Cannabinoid Receptor Type 2 |

| CBG | Cannabigerol |

| CBD | Cannabidiol |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| DAGLα | Diacylglycerol Lipase Alpha |

| DAGLβ | Diacylglycerol Lipase Beta |

| DRG | Dorsal Root Ganglia |

| EGFP | Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein |

| ERK | Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase |

| ECS | Endocannabinoid System |

| eCBome | Endocannabinoidome |

| FAAH | Fatty Acid Amide Hydrolase |

| GPCRs | G Protein-Coupled Receptors |

| GRKs | G Protein-Coupled Receptor Kinases |

| Gαi/o | G Protein Alpha Subunits Gi/Go |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-Gamma |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 Beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| MAGL | Monoacylglycerol Lipase |

| M1 | Macrophage Phenotype 1 |

| M2 | Macrophage Phenotype 2 |

| MeCP | Methyl-CpG-Binding Proteins |

| MeCP2 | Methyl-CpG-Binding Protein 2 |

| miRNAs | MicroRNAs |

| NAMs | Negative Allosteric Modulators |

| NAPE-PLD | N-Acyl Phosphatidylethanolamine-Specific Phospholipase D |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa-Light-Chain-Enhancer of Activated B Cells |

| PAMs | Positive Allosteric Modulators |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-Gamma |

| PPARs | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| TET1/2/3 | Ten-Eleven Translocation Enzymes 1/2/3 |

| THC | Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha |

| TRP | Transient Receptor Potential Channels |

| TRPM8 | Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin Subtype 8 |

| TRPV1 | Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 |

References

- Gaoni, Y.; Mechoulam, R. Isolation, Structure, and Partial Synthesis of an Active Constituent of Hashish. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 1646–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechoulam, R.; Shvo, Y. Hashish—I: The structure of Cannabidiol. Tetrahedron 1963, 19, 2073–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcotte, C.; Chouinard, F.; Lefebvre, J.S.; Flamand, N. Regulation of inflammation by cannabinoids, the endocannabinoids 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol and arachidonoyl-ethanolamide, and their metabolites. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2015, 97, 1049–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simard, M.; Archambault, A.-S.; Lavoie, J.-P.C.; Dumais, É.; Di Marzo, V.; Flamand, N. Biosynthesis and metabolism of endocannabinoids and their congeners from the monoacylglycerol and N-acyl-ethanolamine families. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2022, 205, 115261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galiegue, S.; Mary, S.; Marchand, J.; Dussossoy, D.; Carriere, D.; Carayon, P.; Bouaboula, M.; Shire, D.; Le Fur, G.; Casellas, P. Expression of central and peripheral cannabinoid receptors in human immune tissues and leukocyte subpopulations. Eur. J. Biochem. 1995, 232, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, L.A.; Lolait, S.J.; Brownstein, M.J.; Young, A.C.; Bonner, T.I. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature 1990, 346, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simard, M.; Rakotoarivelo, V.; Di Marzo, V.; Flamand, N. Expression and Functions of the CB2 Receptor in Human Leukocytes. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 826400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, S.; Thomas, K.L.; Abu-Shaar, M. Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature 1993, 365, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakotoarivelo, V.; Mayer, T.Z.; Simard, M.; Flamand, N.; Di Marzo, V. The Impact of the CB2 Cannabinoid Receptor in Inflammatory Diseases: An Update. Molecules 2024, 29, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcotte, C.; Blanchet, M.-R.; LaViolette, M.; Flamand, N. The CB2 receptor and its role as a regulator of inflammation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 4449–4470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.M.; Wager-Miller, J.; Mackie, K. Cloning and molecular characterization of the rat CB2 cannabinoid receptor. Biochim. Biophys. 2002, 1576, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shire, D.; Calandra, B.; Rinaldi-Carmona, M.; Oustric, D.; Pessegue, B.; Bonnin-Cabanne, O.; Le Fur, G.; Caput, D.; Ferrara, P. Molecular cloning, expression and function of the murine CB2 peripheral cannabinoid receptor. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Gene Struct. Expr. 1996, 1307, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, G.; Tao, Q.; Abood, M.E. Cloning and pharmacological characterization of the rat CB(2) cannabinoid receptor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000, 292, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannotti, F.A.; Di Marzo, V.; Petrosino, S. Endocannabinoids and endocannabinoid-related mediators: Targets, metabolism and role in neurological disorders. Prog. Lipid Res. 2016, 62, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olabiyi, B.F.; Schmoele, A.-C.; Beins, E.C.; Zimmer, A. Pharmacological blockade of cannabinoid receptor 2 signaling does not affect LPS/IFN-γ-induced microglial activation. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabon, W.; Ruiz, A.; Gasmi, N.; Degletagne, C.; Georges, B.; Belmeguenai, A.; Bodennec, J.; Rheims, S.; Marcy, G.; Bezin, L. CB2 expression in mouse brain: From mapping to regulation in microglia under inflammatory conditions. J. Neuroinflamm. 2024, 21, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloman, B.L.; Nagarkatti, M.; Nagarkatti, P. Epigenetic Regulation of Cannabinoid-Mediated Attenuation of Inflammation and Its Impact on the Use of Cannabinoids to Treat Autoimmune Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börner, C.; Martella, E.; Höllt, V.; Kraus, J. Regulation of Opioid and Cannabinoid Receptor Genes in Human Neuroblastoma and T Cells by the Epigenetic Modifiers Trichostatin A and 5-Aza-2′-Deoxycytidine. Neuroimmunomodulation 2012, 19, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, K.; Zhang, G.-F.; Chen, H.; Chen, S.-R.; Pan, H.-L. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors are upregulated via bivalent histone modifications and control primary afferent input to the spinal cord in neuropathic pain. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 101999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meccariello, R.; Santoro, A.; D’Angelo, S.; Morrone, R.; Fasano, S.; Viggiano, A.; Pierantoni, R. The Epigenetics of the Endocannabinoid System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weizman, N.F.; A Wyse, B.; Szaraz, P.; Defer, M.; Jahangiri, S.; Librach, C.L. Cannabis alters epigenetic integrity and endocannabinoid signalling in the human follicular niche. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 36, 1922–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.C.; Sershen, H.; Janowsky, D.S.; Lajtha, A.; Grieco, M.; Gangoiti, J.A.; Gertsman, I.; Johnson, W.S.; Marcotte, T.D.; Davis, J.M. Changes in Expression of DNA-Methyltransferase and Cannabinoid Receptor mRNAs in Blood Lymphocytes After Acute Cannabis Smoking. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 887700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innocenzi, E.; De Domenico, E.; Ciccarone, F.; Zampieri, M.; Rossi, G.; Cicconi, R.; Bernardini, R.; Mattei, M.; Grimaldi, P. Paternal activation of CB2 cannabinoid receptor impairs placental and embryonic growth via an epigenetic mechanism. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nan, X.; Ng, H.-H.; Johnson, C.A.; Laherty, C.D.; Turner, B.M.; Eisenman, R.N.; Bird, A. Transcriptional repression by the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 involves a histone deacetylase complex. Nature 1998, 393, 386–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, A. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, P.L.; Veenstra, G.J.C.; Wade, P.A.; Vermaak, D.; Kass, S.U.; Landsberger, N.; Strouboulis, J.; Wolffe, A.P. Methylated DNA and MeCP2 recruit histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nat. Genet. 1998, 19, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouzarides, T. Histone methylation in transcriptional control. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2002, 12, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuks, F.; Hurd, P.J.; Wolf, D.; Nan, X.; Bird, A.P.; Kouzarides, T. The methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 links DNA methylation to histone methylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 4035–4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basavarajappa, B.S.; Subbanna, S. Molecular Insights into Epigenetics and Cannabinoid Receptors. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguado, T.; Carracedo, A.; Julien, B.; Velasco, G.; Milman, G.; Mechoulam, R.; Alvarez, L.; Guzmán, M.; Galve-Roperh, I. Cannabinoids Induce Glioma Stem-like Cell Differentiation and Inhibit Gliomagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 6854–6862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, M.; Morita, S.; Wakamori, M.; Sato, S.; Uchikubo-Kamo, T.; Suzuki, T.; Dohmae, N.; Shirouzu, M.; Umehara, T. Epigenetic mechanisms to propagate histone acetylation by p300/CBP. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Cooper, S.; Brockdorff, N. The interplay of histone modifications—Writers that read. EMBO Rep. 2015, 16, 1467–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghare, S.S.; Joshi-Barve, S.; Moghe, A.; Patil, M.; Barker, D.F.; Gobejishvili, L.; Brock, G.N.; Cave, M.; McClain, C.J.; Barve, S.S. Coordinated histone H3 methylation and acetylation regulates physiologic and pathologic Fas Ligand gene expression in human CD4+ T cells. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Milne, T.A.; Tackett, A.J.; Smith, E.R.; Fukuda, A.; Wysocka, J.; Allis, C.D.; Chait, B.T.; Hess, J.L.; Roeder, R.G. Physical association and coordinate function of the H3 K4 methyltransferase MLL1 and the H4 K16 acetyltransferase MOF. Cell 2005, 121, 873–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozzetta, C.; Pontis, J.; Fritsch, L.; Robin, P.; Portoso, M.; Proux, C.; Margueron, R.; Ait-Si-Ali, S. The Histone H3 Lysine 9 Methyltransferases G9a and GLP Regulate Polycomb Repressive Complex 2-Mediated Gene Silencing. Mol. Cell 2014, 53, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yang, W.; Wang, W.; Wang, Z.; Pu, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, F.; Qian, J. Involvement of miR-665 in protection effect of dexmedetomidine against Oxidative Stress Injury in myocardial cells via CB2 and CK. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 115, 108894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weis, F.; Beiras-Fernandez, A.; Sodian, R.; Kaczmarek, I.; Reichart, B.; Beiras, A.; Schelling, G.; Kreth, S. Substantially altered expression pattern of cannabinoid receptor 2 and activated endocannabinoid system in patients with severe heart failure. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2010, 48, 1187–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Möhnle, P.; Schütz, S.V.; Schmidt, M.; Hinske, C.; Hübner, M.; Heyn, J.; Beiras-Fernandez, A.; Kreth, S. MicroRNA-665 is involved in the regulation of the expression of the cardioprotective cannabinoid receptor CB2 in patients with severe heart failure. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 451, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashiesh, H.M.; Sharma, C.; Goyal, S.N.; Jha, N.K.; Ojha, S. Pharmacological Properties, Therapeutic Potential and Molecular Mechanisms of JWH133, a CB2 Receptor-Selective Agonist. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 702675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murataeva, N.; Mackie, K.; Straiker, A. The CB2-preferring agonist JWH015 also potently and efficaciously activates CB1 in autaptic hippocampal neurons. Pharmacol. Res. 2012, 66, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hanuš, L.; Breuer, A.; Tchilibon, S.; Shiloah, S.; Goldenberg, D.; Horowitz, M.; Pertwee, R.G.; Ross, R.A.; Mechoulam, R.; Fride, E. HU-308: A specific agonist for CB2, a peripheral cannabinoid receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 14228–14233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Peigneur, S.; Tytgat, J. WIN55,212-2, a Dual Modulator of Cannabinoid Receptors and G Protein-Coupled Inward Rectifier Potassium Channels. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertwee, R.G.; Howlett, A.C.; Abood, M.E.; Alexander, S.P.H.; Di Marzo, V.; Elphick, M.R.; Greasley, P.J.; Hansen, H.S.; Kunos, G.; Mackie, K.; et al. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXIX. Cannabinoid Receptors and Their Ligands: Beyond CB1 and CB2. Pharmacol. Rev. 2010, 62, 588–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polini, B.; Cervetto, C.; Carpi, S.; Pelassa, S.; Gado, F.; Ferrisi, R.; Bertini, S.; Nieri, P.; Marcoli, M.; Manera, C. Positive Allosteric Modulation of CB1 and CB2 Cannabinoid Receptors Enhances the Neuroprotective Activity of a Dual CB1R/CB2R Orthosteric Agonist. Life 2020, 10, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrucci, V.; Chicca, A.; Glasmacher, S.; Paloczi, J.; Cao, Z.; Pacher, P.; Gertsch, J. Pepcan-12 (RVD-hemopressin) is a CB2 receptor positive allosteric modulator constitutively secreted by adrenals and in liver upon tissue damage. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gado, F.; Mohamed, K.A.; Meini, S.; Ferrisi, R.; Bertini, S.; Digiacomo, M.; D’aNdrea, F.; Stevenson, L.A.; Laprairie, R.B.; Pertwee, R.G.; et al. Variously substituted 2-oxopyridine derivatives: Extending the structure-activity relationships for allosteric modulation of the cannabinoid CB2 receptor. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 211, 113116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, P.; Roy, K.K.; Doerksen, R.J. Negative Allosteric Modulators of Cannabinoid Receptor 2: Protein Modeling, Binding Site Identification and Molecular Dynamics Simulations in the Presence of an Orthosteric Agonist. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2019, 38, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzeczycki, P.; Rasner, C.; Lammlin, L.; Junginger, L.; Goldman, S.; Bergman, R.; Redding, S.; Knights, A.; Elliott, M.; Maerz, T. Cannabinoid receptor type 2 is upregulated in synovium following joint injury and mediates anti-inflammatory effects in synovial fibroblasts and macrophages. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2021, 29, 1720–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarique, A.A.; Evron, T.; Zhang, G.; Tepper, M.A.; Morshed, M.M.; Andersen, I.S.; Begum, N.; Sly, P.D.; Fantino, E. Anti-inflammatory effects of lenabasum, a cannabinoid receptor type 2 agonist, on macrophages from cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2020, 19, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffal, E.; Kemter, A.M.; Scheu, S.; Dantas, R.L.; Vogt, J.; Baune, B.; Tüting, T.; Zimmer, A.; Alferink, J. Cannabinoid Receptor 2 Modulates Maturation of Dendritic Cells and Their Capacity to Induce Hapten-Induced Contact Hypersensitivity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, S.; Kocieda, V.P.; Yen, J.-H.; Tuma, R.F.; Ganea, D. Signaling through cannabinoid receptor 2 suppresses murine dendritic cell migration by inhibiting matrix metalloproteinase 9 expression. Blood 2012, 120, 3741–3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, W.; Li, H.; Tuma, R.F.; Ganea, D. Selective CB2 receptor activation ameliorates EAE by reducing Th17 differentiation and immune cell accumulation in the CNS. Cell. Immunol. 2014, 287, 3741–3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sido, J.M.; Nagarkatti, P.S.; Nagarkatti, M. Production of endocannabinoids by activated T cells and B cells modulates inflammation associated with delayed-type hypersensitivity. Eur. J. Immunol. 2016, 46, 1472–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.; Alliger, K.; Weidinger, C.; Yerinde, C.; Wirtz, S.; Becker, C.; Engel, M.A. Functional Role of Transient Receptor Potential Channels in Immune Cells and Epithelia. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, V.H.; Teeling, J. Microglia and macrophages of the central nervous system: The contribution of microglia priming and systemic inflammation to chronic neurodegeneration. Semin. Immunopathol. 2013, 35, 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabon, W.; Rheims, S.; Smith, J.; Bodennec, J.; Belmeguenai, A.; Bezin, L. CB2 receptor in the CNS: From immune and neuronal modulation to behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 150, 105226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallelli, C.A.; Calcagnini, S.; Romano, A.; Koczwara, J.B.; De Ceglia, M.; Dante, D.; Villani, R.; Giudetti, A.M.; Cassano, T.; Gaetani, S. Modulation of the Oxidative Stress and Lipid Peroxidation by Endocannabinoids and Their Lipid Analogues. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Sackett, S.; Zhang, Y. Endocannabinoid Modulation of Microglial Phenotypes in Neuropathology. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, V.R.; Shafiee-Nick, R. The protective effects of β-caryophyllene on LPS-induced primary microglia M1/M2 imbalance: A mechanistic evaluation. Life Sci. 2019, 219, 40–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Niu, W.; Lv, J.; Jia, J.; Zhu, M.; Yang, S. PGC-1α-Mediated Mitochondrial Biogenesis is Involved in Cannabinoid Receptor 2 Agonist AM1241-Induced Microglial Phenotype Amelioration. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 38, 1529–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, N.; Popiolek-Barczyk, K.; Mika, J.; Przewlocka, B.; Starowicz, K. Anandamide, Acting via CB2 Receptors, Alleviates LPS-Induced Neuroinflammation in Rat Primary Microglial Cultures. Neural Plast. 2015, 2015, 130639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuic, B.; Milos, T.; Tudor, L.; Konjevod, M.; Perkovic, M.N.; Jembrek, M.J.; Erjavec, G.N.; Strac, D.S. Cannabinoid CB2 Receptors in Neurodegenerative Proteinopathies: New Insights and Therapeutic Potential. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aso, E.; Juvés, S.; Maldonado, R.; Ferrer, I. CB2 Cannabinoid Receptor Agonist Ameliorates Alzheimer-Like Phenotype in AβPP/PS1 Mice. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2013, 35, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Dorado, J.; Villalba, N.; Prieto, D.; Brera, B.; Martín-Moreno, A.M.; Tejerina, T.; de Ceballos, M.L. Vascular Dysfunction in a Transgenic Model of Alzheimer’s Disease: Effects of CB1R and CB2R Cannabinoid Agonists. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köfalvi, A.; Lemos, C.; Martín-Moreno, A.M.; Pinheiro, B.S.; García-García, L.; Pozo, M.A.; Valério-Fernandes, Â.; Beleza, R.O.; Agostinho, P.; Rodrigues, R.J.; et al. Stimulation of brain glucose uptake by cannabinoid CB2 receptors and its therapeutic potential in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropharmacology 2016, 110 Pt A, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.-M.; Zheng, Q.-X.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.-T.; Gong, L.-P.; Zeng, Y.-C.; Liu, S. N-linoleyltyrosine exerts neuroprotective effects in APP/PS1 transgenic mice via cannabinoid receptor-mediated autophagy. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 147, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Santisteban, R.; Lillo, A.; Lillo, J.; Rebassa, J.-B.; Contestí, J.S.; Saura, C.A.; Franco, R.; Navarro, G. N-Methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and cannabinoid CB2 receptors form functional complexes in cells of the central nervous system: Insights into the therapeutic potential of neuronal and microglial NMDA receptors. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2021, 13, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Shi, J.; Wang, B.; Li, J.; Jia, H. CB2 cannabinoid receptor agonist ameliorates novel object recognition but not spatial memory in transgenic APP/PS1 mice. Neurosci. Lett. 2019, 707, 134286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Bie, B.; Yang, H.; Xu, J.J.; Brown, D.L.; Naguib, M. Activation of the CB2 receptor system reverses amyloid-induced memory deficiency. Neurobiol. Aging 2013, 34, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Hocevar, M.; Foss, J.F.; Bie, B.; Naguib, M. Activation of CB2 receptor system restores cognitive capacity and hippocampal Sox2 expression in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 811, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, A.; Aparicio, N.; Pazos, M.R.; Grande, M.T.; Barreda-Manso, M.A.; Benito-Cuesta, I.; Vázquez, C.; Amores, M.; Ruiz-Pérez, G.; García-García, E.; et al. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors in the mouse brain: Relevance for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroinflamm. 2018, 15, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteban, S.R.d.M.; Benito-Cuesta, I.; Terradillos, I.; Martínez-Relimpio, A.M.; Arnanz, M.A.; Ruiz-Pérez, G.; Korn, C.; Raposo, C.; Sarott, R.C.; Westphal, M.V.; et al. Cannabinoid CB2 Receptors Modulate Microglia Function and Amyloid Dynamics in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 841766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, P.B.; Hare, D.J.; Double, K.L. A brief history of brain iron accumulation in Parkinson disease and related disorders. J. Neural Transm. 2022, 129, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibret, B.G.; Ishiguro, H.; Horiuchi, Y.; Onaivi, E.S. New Insights and Potential Therapeutic Targeting of CB2 Cannabinoid Receptors in CNS Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.C.; Cinquina, V.; Palomo-Garo, C.; Rábano, A.; Fernández-Ruiz, J. Identification of CB2 receptors in human nigral neurons that degenerate in Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2015, 587, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concannon, R.M.; Okine, B.N.; Finn, D.P.; Dowd, E. Upregulation of the cannabinoid CB2 receptor in environmental and viral inflammation-driven rat models of Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 283, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wi, R.; Chung, Y.C.; Jin, B.K. Functional Crosstalk between CB and TRPV1 Receptors Protects Nigrostriatal Dopaminergic Neurons in the MPTP Model of Parkinson’s Disease. J. Immunol. Res. 2020, 2020, 5093493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Liu, X.; Chen, B.; Vickstrom, C.R.; Friedman, V.; Kelly, T.J.; Bai, X.; Zhao, L.; Hillard, C.J.; Liu, Q.-S. The Neuroprotective Effects of the CB2 Agonist GW842166x in the 6-OHDA Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Cells 2021, 10, 3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, R.; Mu, L.; Ametamey, S. Positron emission tomography of type 2 cannabinoid receptors for detecting inflammation in the central nervous system. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2018, 40, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, R.K.; Asghar, K.; Kanwal, S.; Zulqernain, A. Role of inflammatory cytokines in depression: Focus on interleukin-1β. Biomed. Rep. 2016, 6, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sălcudean, A.; Bodo, C.-R.; Popovici, R.-A.; Cozma, M.-M.; Păcurar, M.; Crăciun, R.-E.; Crisan, A.-I.; Enatescu, V.-R.; Marinescu, I.; Cimpian, D.-M.; et al. Neuroinflammation—A Crucial Factor in the Pathophysiology of Depression—A Comprehensive Review. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, M.; Rachayon, M.; Jirakran, K.; Sughondhabirom, A.; Almulla, A.F.; Sodsai, P. Role of T and B lymphocyte cannabinoid type 1 and 2 receptors in major depression and suicidal behaviours. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2023, 36, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gutiérrez, M.S.; Manzanares, J. Overexpression of CB2 cannabinoid receptors decreased vulnerability to anxiety and impaired anxiolytic action of alprazolam in mice. J. Psychopharmacol. 2010, 25, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stempel, A.V.; Stumpf, A.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Özdoğan, T.; Pannasch, U.; Theis, A.-K.; Otte, D.-M.; Wojtalla, A.; Rácz, I.; Ponomarenko, A.; et al. Cannabinoid Type 2 Receptors Mediate a Cell Type-Specific Plasticity in the Hippocampus. Neuron 2016, 90, 795–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, E.-S.; Kim, H.-B.; Lee, S.; Kim, M.-J.; Kim, K.-J.; Han, G.; Han, S.-Y.; Lee, E.-A.; Yoon, J.-H.; Kim, D.-O.; et al. Antidepressant-like effects of β-caryophyllene on restraint plus stress-induced depression. Behav. Brain Res. 2020, 380, 112439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán-Ganga, M.; del Río, R.; Jiménez-Moreno, N.; Díaz-Guerra, M.; Lastres-Becker, I. Cannabinoid CB2 Receptor Modulation by the Transcription Factor NRF2 is Specific in Microglial Cells. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 40, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Daksh, R.; Khanna, S.; Mudgal, J.; Lewis, S.A.; Arora, D.; Nampoothiri, M. Microglial cannabinoid receptor 2 and epigenetic regulation: Implications for the treatment of depression. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 995, 177422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallego-Landin, I.; García-Baos, A.; Castro-Zavala, A.; Valverde, O. Reviewing the Role of the Endocannabinoid System in the Pathophysiology of Depression. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 762738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzanares, J.; Julian, M.D.; Carrascosa, A. Role of the Cannabinoid System in Pain Control and Therapeutic Implications for the Management of Acute and Chronic Pain Episodes. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2006, 4, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guindon, J.; Hohmann, A.G. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors: A therapeutic target for the treatment of inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 153, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.M.; Deng, H.; Zvonok, A.; Cockayne, D.A.; Kwan, J.; Mata, H.P.; Vanderah, T.W.; Lai, J.; Porreca, F.; Makriyannis, A.; et al. Activation of CB2 cannabinoid receptors by AM1241 inhibits experimental neuropathic pain: Pain inhibition by receptors not present in the CNS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 10529–10533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curto-Reyes, V.; Boto, T.; Hidalgo, A.; Menéndez, L.; Baamonde, A. Antinociceptive effects induced through the stimulation of spinal cannabinoid type 2 receptors in chronically inflamed mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 668, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownjohn, P.; Ashton, J. Spinal cannabinoid CB2 receptors as a target for neuropathic pain: An investigation using chronic constriction injury. Neuroscience 2012, 203, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, J.C.; Glass, M. The Cannabinoid CB2 Receptor as a Target for Inflammation-Dependent Neurodegeneration. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2007, 5, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiue, S.-J.; Peng, H.-Y.; Lin, C.-R.; Wang, S.-W.; Rau, R.-H.; Cheng, J.-K. Continuous Intrathecal Infusion of Cannabinoid Receptor Agonists Attenuates Nerve Ligation–Induced Pain in Rats. Reg. Anesthesia Pain Med. 2017, 42, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beltramo, M.; Bernardini, N.; Bertorelli, R.; Campanella, M.; Nicolussi, E.; Fredduzzi, S.; Reggiani, A. CB2 receptor-mediated antihyperalgesia: Possible direct involvement of neural mechanisms. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006, 23, 1530–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racz, I.; Nadal, X.; Alferink, J.; Baños, J.E.; Rehnelt, J.; Martín, M.; Pintado, B.; Gutierrez-Adan, A.; Sanguino, E.; Manzanares, J.; et al. Crucial Role of CB2 Cannabinoid Receptor in the Regulation of Central Immune Responses during Neuropathic Pain. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 12125–12135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Sandoval, A.; Nutile-McMenemy, N.; DeLeo, J.A. Spinal microglial and perivascular cell cannabinoid receptor type 2 activation reduces behavioral hypersensitivity without tolerance after peripheral nerve injury. Anesthesiology 2008, 108, 722–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, S.S.; Hayes, J.P.; Fiore, N.T.; Moalem-Taylor, G. The cannabinoid system and microglia in health and disease. Neuropharmacology 2021, 190, 108555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, B.B.; Hsieh, G.C.; Frost, J.M.; Fan, Y.; Garrison, T.R.; Daza, A.V.; Grayson, G.K.; Zhu, C.Z.; Pai, M.; Chandran, P.; et al. In vitro and in vivo characterization of A-796260: A selective cannabinoid CB2 receptor agonist exhibiting analgesic activity in rodent pain models. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 153, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Taylor, B.K. Activation of Cannabinoid CB2 receptors Reduces Hyperalgesia in an Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis Mouse Model of Multiple Sclerosis. Neurosci. Lett. 2015, 595, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klauke, A.-L.; Racz, I.; Pradier, B.; Markert, A.; Zimmer, A.; Gertsch, J.; Zimmer, A. The cannabinoid CB2 receptor-selective phytocannabinoid beta-caryophyllene exerts analgesic effects in mouse models of inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014, 24, 608–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura, D.K.; Morrison, B.E.; Blankman, J.L.; Long, J.Z.; Kinsey, S.G.; Marcondes, M.C.G.; Ward, A.M.; Hahn, Y.K.; Lichtman, A.H.; Conti, B.; et al. Endocannabinoid hydrolysis generates brain prostaglandins that promote neuroinflammation. Science 2011, 334, 809–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristino, L.; Bisogno, T.; Di Marzo, V. Cannabinoids and the expanded endocannabinoid system in neurological disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 16, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Petrocellis, L.; Ligresti, A.; Moriello, A.S.; Allarà, M.; Bisogno, T.; Petrosino, S.; Stott, C.G.; Di Marzo, V. Effects of cannabinoids and cannabinoid-enriched Cannabis extracts on TRP channels and endocannabinoid metabolic enzymes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 163, 1479–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, G.; Varani, K.; Reyes-Resina, I.; Sánchez de Medina, V.; Rivas-Santisteban, R.; Sánchez-Carnerero Callado, C.; Vincenzi, F.; Casano, S.; Ferreiro-Vera, C.; Canela, E.I.; et al. Cannabigerol Action at Cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 Receptors and at CB1–CB2 Heteroreceptor Complexes. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernail, V.L.; Bingaman, S.S.; Silberman, Y.; Raup-Konsavage, W.M.; Vrana, K.E.; Arnold, A.C. Acute Cannabigerol Administration Lowers Blood Pressure in Mice. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 871962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killestein, J.; Hoogervorst, E.L.; Reif, M.; Kalkers, N.F.; van Loenen, A.C.; Staats, P.G.; Gorter, R.W.; Uitdehaag, B.M.; Polman, C.H. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of orally administered cannabinoids in MS. Neurology 2002, 58, 1404–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zajicek, J.P.; Sanders, H.P.; E Wright, D.; Vickery, P.J.; Ingram, W.M.; Reilly, S.M.; Nunn, A.J.; Teare, L.J.; Fox, P.J.; Thompson, A.J. Cannabinoids in multiple sclerosis (CAMS) study: Safety and efficacy data for 12 months follow up. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2005, 76, 1664–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaney, C.; Heinzel-Gutenbrunner, M.; Jobin, P.; Tschopp, F.; Gattlen, B.; Hagen, U.; Schnelle, M.; Reif, M. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of an orally administered cannabis extract in the treatment of spasticity in patients with multiple sclerosis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Mult. Scler. J. 2004, 10, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, D.T.; Makela, P.M.; House, H.; Bateman, C.; Robson, P. Long-term use of a cannabis-based medicine in the treatment of spasticity and other symptoms in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2006, 12, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, C.; Davies, P.; Mutiboko, I.K.; Ratcliffe, S.; for the Sativex Spasticity in MS Study Group. Randomized controlled trial of cannabis-based medicine in spasticity caused by multiple sclerosis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2007, 14, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novotna, A.; Mares, J.; Ratcliffe, S.; Novakova, I.; Vachova, M.; Zapletalova, O.; Gasperini, C.; Pozzilli, C.; Cefaro, L.; Comi, G.; et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, enriched-design study of nabiximols* (Sativex®), as add-on therapy, in subjects with refractory spasticity caused by multiple sclerosis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2011, 18, 1122–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, D.T.; Makela, P.; Robson, P.; House, H.; Bateman, C. Do cannabis-based medicinal extracts have general or specific effects on symptoms in multiple sclerosis? A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study on 160 patients. Mult. Scler. J. 2004, 10, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, C.; Ehler, E.; Waberzinek, G.; Alsindi, Z.; Davies, P.; Powell, K.; Notcutt, W.; O’Leary, C.; Ratcliffe, S.; Nováková, I.; et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study of Sativex, in subjects with symptoms of spasticity due to multiple sclerosis. Neurol. Res. 2010, 32, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, R.M.; Mares, J.; Novotna, A.; Vachova, M.; Novakova, I.; Notcutt, W.; Ratcliffe, S. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study of THC/CBD oromucosal spray in combination with the existing treatment regimen, in the relief of central neuropathic pain in patients with multiple sclerosis. J. Neurol. 2012, 260, 984–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, M.; Calabrò, R.S.; Naro, A.; Sessa, E.; Rifici, C.; D’aLeo, G.; Leo, A.; De Luca, R.; Quartarone, A.; Bramanti, P. Sativex in the Management of Multiple Sclerosis-Related Spasticity: Role of the Corticospinal Modulation. Neural Plast. 2015, 2015, 656582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trépanier, M.O.; Hopperton, K.E.; Mizrahi, R.; Mechawar, N.; Bazinet, R.P. Postmortem evidence of cerebral inflammation in schizophrenia: A systematic review. Mol. Psychiatry 2016, 21, 1009–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]