First Metagenomic Shotgun Sequencing Report on the Microbiome of Local Goat and Sheep Raw Milk in Benin for Dairy Valorization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Sample Collection

2.2. Metagenomic DNA Extraction

2.3. Library Preparation and Next Generation Sequencing

2.4. Data Analysis

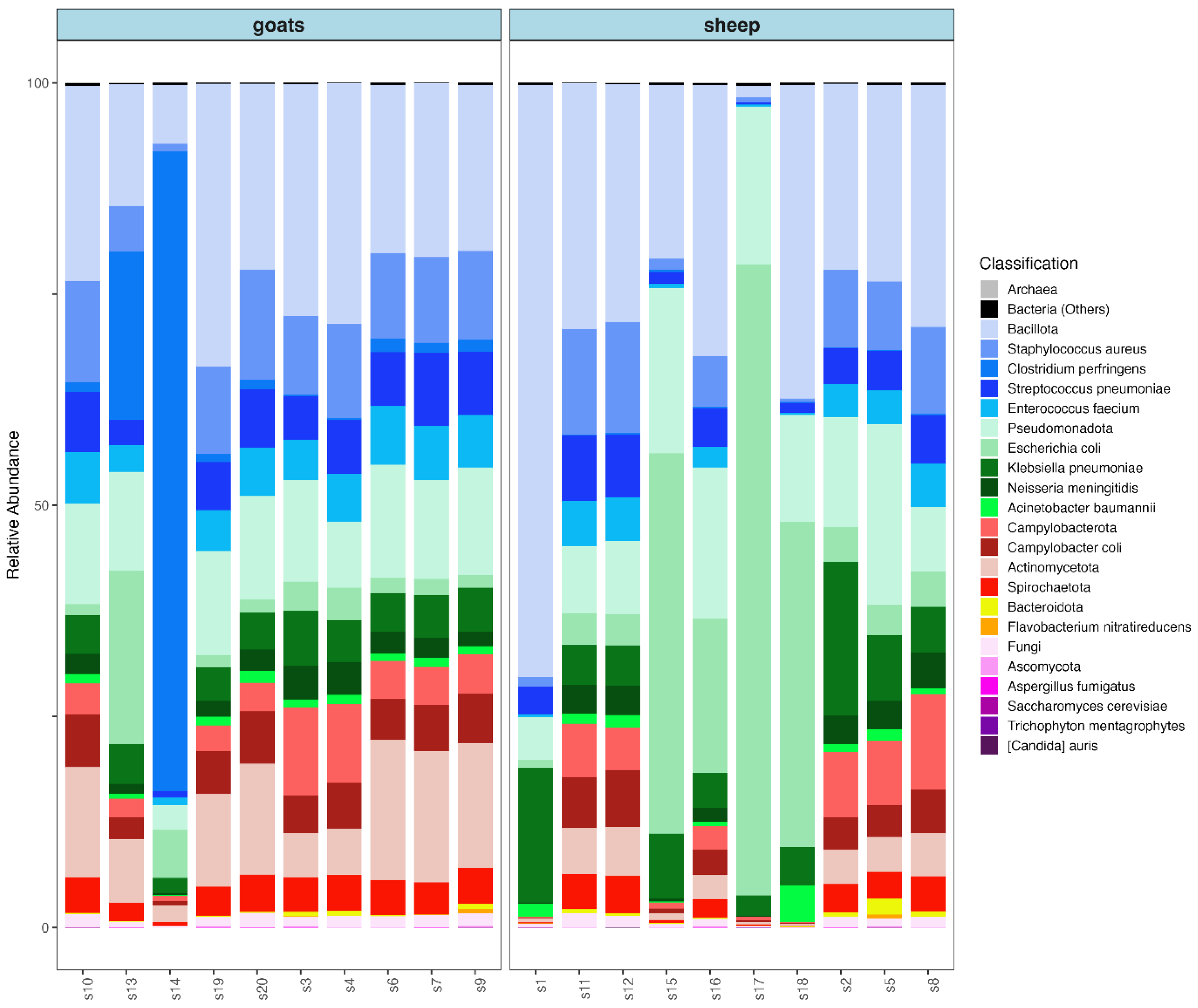

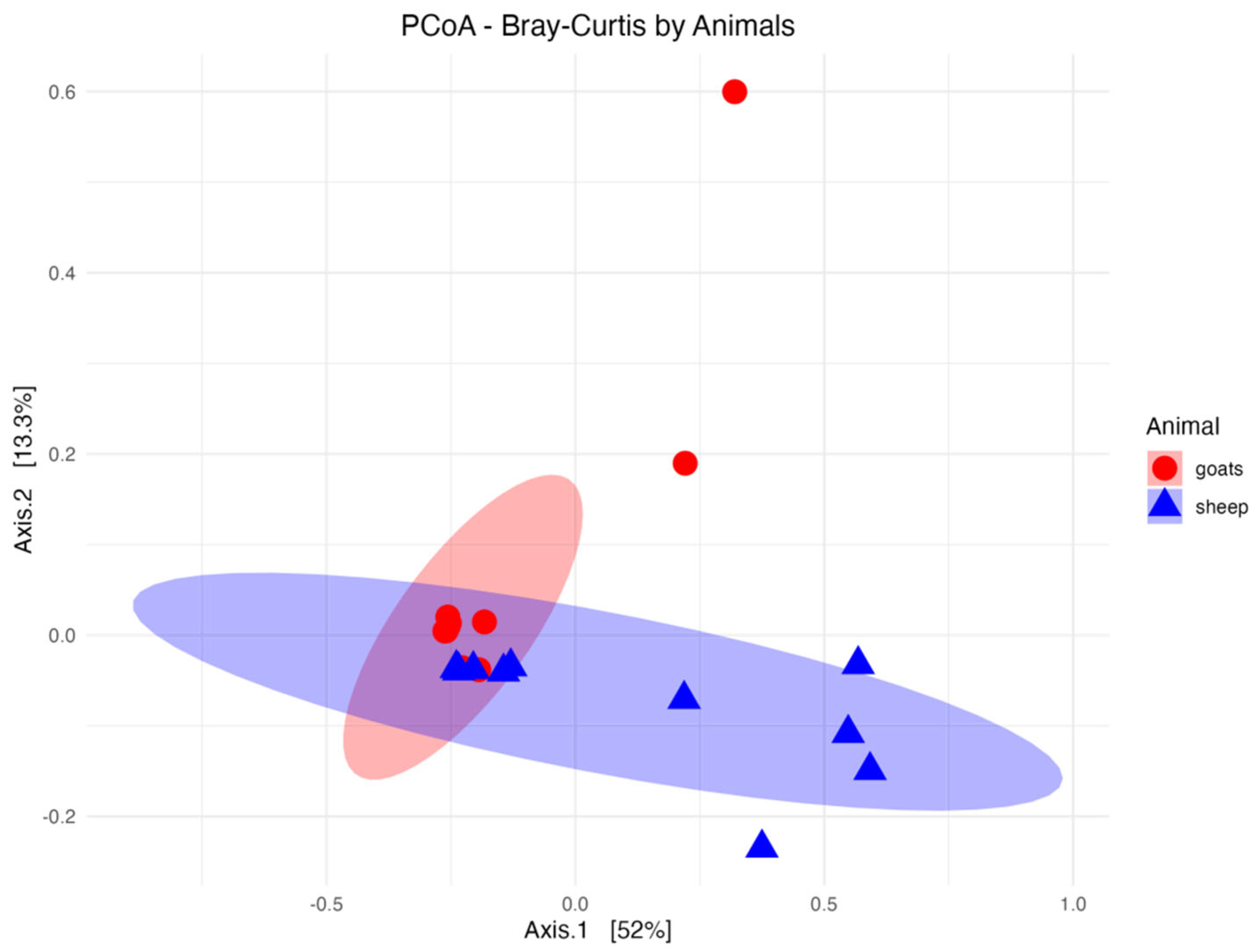

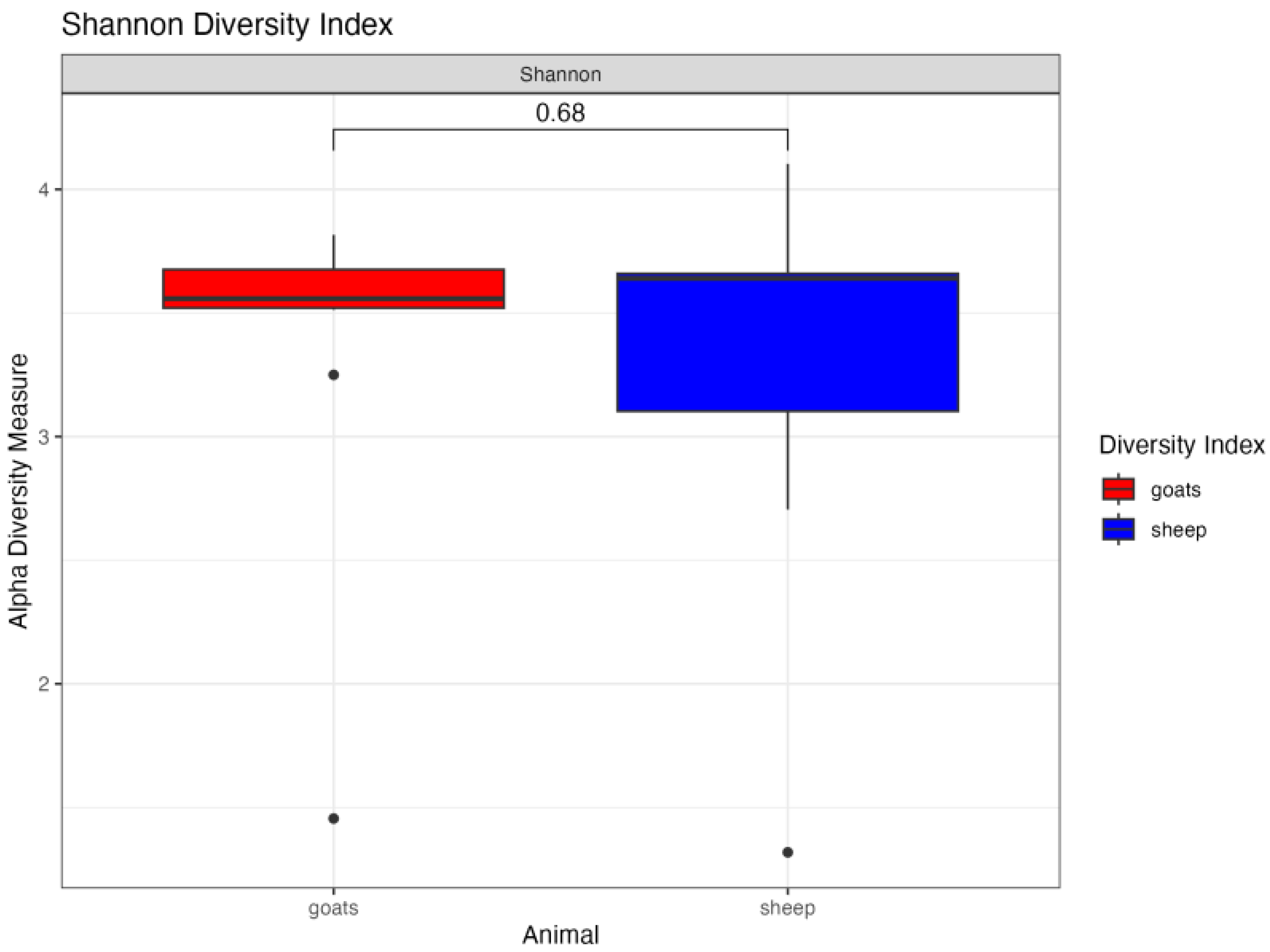

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Safety of the Investigated Milk Samples

4.2. Technological Potential and Beneficial Microorganisms Identified from Studied Milk Samples

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Komagbe, G.S.; Dossou, A.; Seko Orou, B.M.-T.; Sessou, P.; Azokpota, P.; Youssao, I.; Hounhouigan, J.; Scippo, M.-L.; Clinquart, A.; Mahillon, J.; et al. State of the art of breeding, milking, and milk processing for the production of curdled milk and Wagashi Gassirè in Benin: Practices favoring the contamination of its dairy products. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 6, 1050592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossou, A.; Seko, B.M.T.; Komagbe, G.; Sessou, P.; Youssao, A.K.I.; Farougou, S.; Hounhouigan, J.; Mongbo, R.; Poncelet, M.; Madode, Y.; et al. Processing and preservation methods of Wagashi Gassirè, a traditional cheese produced in Benin. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icoutchika, K.-L.M.; Ahozonlin, M.C.; Mitchikpe, C.E.S.; Bouraima, O.F.; Aboh, A.B.; Dossa, L.H. Socio-Economic Determinants of Goat Milk Consumption by Rural Households in the Niger Valley of Benin and Implications for the development of a smallholder dairy goat program. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 901293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. Données sur la Production Animale. 2024. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Prosser, C.G. Compositional functional characteristics of goat milk relevance as a base for infant formula. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALKaisy, Q.H.; Al-Saadi, J.S.; Al-Rikabi, A.K.J.; Altemimi, A.B.; Hesarinejad, M.A.; Abedelmaksoud, T.G. Exploring the health benefits and functional properties of goat milk proteins. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 5641–5656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Bagnicka, E.; Chen, H.; Shu, G. Health potential of fermented goat dairy products: Composition comparison with fermented cow milk, probiotics selection, health benefits and mechanisms. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 3423–3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allais-Bonnet, A.; Richard, C.; André, M.; Gelin, V.; Deloche, M.-C.; Lamadon, A.; Morin, G.; Mandon-Pepin, B.; Canon, E.; Thepot, D.; et al. CRISPR/Cas9-editing of PRNP in Alpine goats. Vet. Res. 2025, 56, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyahia, F.A.; Bouali, A.; Meghzili, B.; Foufou, E.; Saadi, S.; El-Mechta, L.; Zitoun, O.A. Review of the main traditional cheese-making in the Mediterranean basin. J. Ethn. Food 2025, 12, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnoli, D.; Pannella, G.; Vergalito, F.; Coppola, F.; Messia, M.C.; Succi, M. Influence of the Mefite D’Ansanto Valley on the chemical characteristics and microbial consortia of raw sheep milk for the production of Pecorino Carmasciano cheese. Food Biosci. 2025, 66, 106254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, F.X.; Wendorff, W.L. Goat and sheep production in the United States (USA). Small Rumin. Res. 2011, 101, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challaton, K.P.; Boko, K.C.; Akouedegni, C.G.; Alowanou, G.G.; Houndonougbo, P.V.; Hounzangbé-Adoté, M.S. Elevage traditionnel des caprins au Bénin: Pratiques et contraintes sanitaires. Rev. Elev. Méd. Vét. Pays Trop. 2022, 75, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anihouvi, D.G.H.; Henriet, O.; Kpoclou, Y.E.; Scippo, M.L.; Hounhouigan, D.J.; Anihouvi, V.B.; Mahillon, J. Bacterial diversity of smoked smoked-dried fish from West Africa: A metagenomic approach. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e15919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavicchioli, V.Q.; Scatamburlo, T.M.; Yamazi, A.K.; Pieri, F.A.; Nero, L.A. Occurrence of Salmonella, Listeria monocytogenes, and enterotoxigenic Staphylococcus in goat milk from small and medium-sized farms located in Minas Gerais State, Brazil. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 8386–8390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijada, N.M.; Schmitz-Esser, S.; Zwirzitz, B.; Guse, C.; Strachan, C.R.; Wagner, M.; Wetzels, S.U.; Selberherr, E.; Dzieciol, M. Austrian Raw-Milk Hard-Cheese Ripening Involves Successional Dynamics of Non-Inoculated Bacteria and Fungi. Foods 2020, 9, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biçer, Y.; Telli, A.E.; Sönmez, G.; Telli, N.; Uçar, G. Comparison of microbiota and volatile organic compounds in milk from different sheep breeds. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 12303–12311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteban-Blanco, C.; Gutiérrez-Gil, B.; Puente-Sánchez, F.; Marina, H.; Tamames, J.; Acedo, A.; Arranz, J.J. Microbiota characterization of sheep milk and its association with somatic cell count using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 2020, 137, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Wang, Y.; You, C.; Ren, J.; Chen, W.; Zheng, H.; Liu, Z. Variation in Raw Milk Microbiota Throughout 12 Months and the Impact of Weather Conditions. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taghizadeh, M.; Nematollahi, A.; Bashiry, M.; Javanmardi, F.; Mousavi, M.; Hosseini, H. The global prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in milk: Asystematic review meta-analysis. Int. Dairy J. 2022, 133, 105423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, Z.; Lei, F.; Wang, B.; Jiang, S.; Peng, Q.; Zhang, J.; Shao, Y. Bacterial diversity in goat milk from the Guanzhong area of China. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 7812–7824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Dong, F.; Liu, Y.; Du, J.; Sun, H.; Ni, Y.; Zhang, Y. Insights into the microbiota of raw milk from seven breeds animals distributing in Xinjiang China. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1382286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamilari, E.; Anagnostopoulos, D.A.; Papademas, P.; Efthymiou, M.; Tretiak, S.; Tsaltas, D. Snapshot of Cyprus Raw Goat Milk Bacterial Diversity via 16S rDNA High-Throughput Sequencing; Impact of Cold Storage Conditions. Fermentation 2020, 6, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauková, A.; Micenková, L.; Grešáková, Ľ.; Maďarová, M.; Simonová, M.P.; Focková, V.; Ščerbová, J. Microbiome Associated with Slovak Raw Goat Milk, Trace Minerals, and Vitamin E Content. Int. J. Food Sci. 2022, 30, 4595473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales-Barron, U.; Gonçalves-Tenório, A.; Rodrigues, V.; Cadavez, V. Foodborne pathogens in raw milk and cheese of sheep and goat origin: A meta-analysis approach. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2017, 18, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepahvand, F.; Rashidian, E.; Jaydari, A.; Rahimi, H. Prevalence of Listeria monocytogenes in raw milk of healthy sheep and goats. Vet. Med. Int. 2022, 3206172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.I.; Cappato, L.P.; Guimarães, J.T.; Balthazar, C.F.; Rocha, R.S.; Franco, L.T.; da Cruz, A.G.; Corassin, C.H.; de Oliveira, C.A.F. Listeria monocytogenes in Milk: Occurrence and Recent Advances in Methods for Inactivation. Beverages 2019, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwafemi, Y.D.; Igere, B.E.; Ekundayo, T.C.; Ijabadeniyi, O.A. Prevalence of Listeria monocytogenes in milk in Africa: A generalized logistic mixed-effects and meta-regression modelling. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Brom, R.; de Jong, A.; van Engelen, E.; Heuvelink, A.; Vellema, P. Zoonotic risks of pathogens from sheep and their milk borne transmission. Small Rumin. Res. 2020, 189, 106123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebadifar, A.M.; Jaydari, A.; Shams, N.; Rahimi, H. Prevalence of Listeria monocytogenes in raw milk of healthy cattle in Lorestan Province (Iran) by PCR. J. Adv. Biomed. Sci. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accettulli, A.; d’Amelio, A. Spoilage of milk and dairy products. In The Microbiological Quality of Food, 2nd ed.; Bevilacqua, A., Corbo, M.R., Sinigaglia, M., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2025; pp. 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaidat, M.M.; AlShehabat, I.A. High multidrug resistance of Listeria monocytogenes and association with water sources in sheep and goat dairy flocks in Jordan. Prev. Vet. Med. 2023, 215, 105922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfraz, M.; Ashraf, Y.; Ashraf, S. A review: Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility profile of Listeria species in milk products. Matrix Sci. Med. 2017, 1, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grispoldi, L.; Karama, M.; Armani, A.; Hadjicharalambous, C.; Cenci-Goga, B.T. Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin in food of animal origin and staphylococcal food poisoning risk assessment from farm to table. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 20, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amagliani, G.; Petruzzelli, A.; Carloni, E.; Tonucci, F.; Foglini, M.; Micci, E.; Ricci, M.; Di Lullo, S.; Rotundo, L.; Brandi, G. Presence of Escherichia coli O157, Salmonella spp., and Listeria monocytogenes in raw ovine milk destined for cheese production and evaluation of the equivalence between the analytical methods applied. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2016, 13, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibessa, Z.A. Review on epidemiology and public health importance of goat tuberculosis in Ethiopia. Vet. Med. Int. 2020, 2020, 8898874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, L.; Gray, D.M.; Botha, M.; Nel, M.; Chaya, S.; Jacobs, C.; Workman, L.; Nicol, M.P.; Zar, H.J. The long-term impact of early-life tuberculosis disease on child health: A prospective birth cohort study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 207, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, S.; Arinaminpathy, N.; Atun, R.; Goosby, E.; Reid, M. Economic impact of tuberculosis mortality in 120 countries and the cost of not achieving the Sustainable Development Goals tuberculosis targets: A full-income analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e1372–e1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, E.; Kazemi Kheirabadi, E. Detection of Helicobacter pylori in bovine, buffalo, camel, ovine, and caprine milk in Iran. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2012, 9, 453–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momtaz, H.; Dabiri, H.; Souod, N.; Gholami, M. Study of Helicobacter pylori genotype status in cows, sheep, goats and human beings. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014, 14, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaglia, N.C.; Dambrosio, A.; Normanno, G.; Parisi, A.; Patrono, R.; Ranieri, G.; Rella, A.; Celano, G.V. High occurrence of Helicobacter pylori in raw goat, sheep and cow milk inferred by glmM gene: A risk of food-borne infection? Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 124, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaei, R.; Souod, N.; Momtaz, H.; Dabiri, H. Milk of livestock as a possible transmission route of Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2015, 8 (Suppl. 1), S30–S36. [Google Scholar]

- Furmančíková, P.; Šťástková, Z.; Navrátilová, P.; Bednářová, I.; Vořáčková, M.D. Prevalence and detection of Helicobacter pylori in raw cows’ and goats’ milk in selected farms in the Czech Republic. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2022, 61, 192–197. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, V.E. Helicobacter pylori and Its Role in Gastric Cancer. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayez, M.; El-Ghareeb, W.R.; Elmoslemany, A.; Alsunaini, S.J.; Alkafafy, M.; Alzahrani, O.M.; Mahmoud, S.F.; Elsohaby, I. Genotyping and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Clostridium perfringens and Clostridioides difficile in Camel Minced Meat. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogarol, C.; Marchino, M.; Scala, S.; Belvedere, M.; Renna, G.; Vitale, N.; Mandola, M.L. Seroprevalence and Risk Factors Associated with Chlamydia abortus Infection in Sheep and Goats in North-Western Italy. Animals 2024, 14, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turin, L.; Surini, S.; Wheelhouse, N.; Rocchi, M.S. Recent advances and public health implications for environmental exposure to Chlamydia abortus: From enzootic to zoonotic disease. Vet. Res. 2022, 53, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Jin, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhou, J.; Tong, D. Seroprevalence of Chlamydia abortus and Brucella spp. and risk factors for Chlamydia abortus in pigs from China. Acta Trop. 2023, 248, 107050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sornchuer, P.; Saninjuk, K.; Amonyingcharoen, S.; Ruangtong, J.; Thongsepee, N.; Martviset, P.; Chantree, P.; Sangpairoj, K. Whole Genome Sequencing Reveals Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Genes of Both Pathogenic and Non-Pathogenic B. cereus Group Isolates from Foodstuffs in Thailand. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehling-Schulz, M.; Koehler, T.M.; Lereclus, D. The Bacillus cereus Group: Bacillus Species with Pathogenic Potential. Microbiol. Spectr. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monareng, N.J.; Ncube, K.T.; van Rooi, C.; Modiba, M.C.; Mtileni, B. A Systematic Review on Microbial Profiling Techniques in Goat Milk: Implications for Probiotics and Shelf-Life. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, D.; Bianco, A.; Manzulli, V.; Castellana, S.; Parisi, A.; Caruso, M.; Fraccalvieri, R.; Serrecchia, L.; Rondinone, V.; Pace, L.; et al. Antimicrobial and Phylogenomic Characterization of Bacillus cereus Group Strains Isolated from Different Food Sources in Italy. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olani, A.; Galante, D.; Lakew, M.; Wakjira, B.S.; Mekonnen, G.A.; Rufael, T.; Teklemariam, T.; Kumilachew, W.; Dejene, S.; Woldemeskel, A.; et al. Identification of Bacillus anthracis Strains from Animal Cases in Ethiopia and Genetic Characterization by Whole-Genome Sequencing. Pathogens 2025, 14, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Shahid, M.A.H.; Nazir, K.H.M.N.H. Molecular Characterization of Bacillus anthracis from Selected Districts of Bangladesh. Acta Microbiol. Hell. 2025, 70, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. About Anthrax. 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/anthrax/about/index.html (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Logue, C.M.; Barbieri, N.L.; Nielsen, D.W. Pathogens of food animals: Sources, characteristics, human risk, and methods of detection. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2017, 82, 277–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, R.A.N.; Abdel-Nour, J.; McAuley, C.; Moore, S.C.; Fegan, N.; Fox, E.M. Clostridium perfringens associated with dairy farm systems show diverse genotypes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 382, 109933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katani, R.; Schilling, M.A.; Lyimo, B.; Eblate, E.; Martin, A.; Tonui, T.; Cattadori, I.M.; Francesconi, S.C.; Estes, A.B.; Rentsch, D.; et al. Identification of Bacillus anthracis, Brucella spp., and Coxiella burnetii DNA signatures from bushmeat. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salauddin, M. Chapter 8—Anthrax. In Neglected Zoonoses and Antimicrobial Resistance: Impact on One Health and Sustainable Development Goals; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025; pp. 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.X.; Ye, T.; Zhang, Q.M.; Zhang, M.; Chen, X.T.; Tang, L.Y.; Yang, M.T.; Jiang, J.; Zhao, Q. Prevalence of Clostridium perfringens in sheep (Ovis aries) and goat (Capra hircus) populations across Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Res. Vet. Sci. 2025, 187, 105605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohiuddin, M.; Iqbal, Z.; Siddique, A.; Liao, S.; Salamat, M.K.F.; Qi, N.; Din, A.M.; Sun, M. Prevalence, Genotypic and Phenotypic Characterization and Antibiotic Resistance Profile of Clostridium perfringens Type A and D Isolated from Feces of Sheep (Ovis aries) and Goats (Capra hircus) in Punjab, Pakistan. Toxins 2020, 12, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Moein, K.A.; Hamza, D.A. Occurrence of human pathogenic Clostridium botulinum among healthy dairy animals: An emerging public health hazard. Pathog. Glob. Health 2016, 110, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ocejo, M.; Oporto, B.; Hurtado, A. Occurrence of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli in Cattle and Sheep in Northern Spain and Changes in Antimicrobial Resistance in Two Studies 10-years Apart. Pathogens 2019, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wareth, G.; Neubauer, H. The Animal-foods-environment interface of Klebsiella pneumoniae in Germany: An observational study on pathogenicity, resistance development and the current situation. Vet. Res. 2021, 52, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakali, E.; Tsantes, A.G.; Houhoula, D.; Laliotis, G.P.; Batrinou, A.; Halvatsiotis, P.; Tsantes, A.E. The Detection of Bacterial Pathogens, including Emerging Klebsiella pneumoniae, Associated with Mastitis in the Milk of Ruminant Species. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.S.; Hung, Y.P.; Lee, J.C.; Syue, L.S.; Hsueh, P.R.; Ko, W.C. Clostridioides difficile infection: An emerging zoonosis? Expert. Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2021, 19, 1543–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Werkhoven, C.H.; Ducher, A.; Berkell, M.; Mysara, M.; Lammens, C.; Torre-Cisneros, J.; Rodriguez-Bano, J.; Herghea, D.; Cornely, O.A.; Biehl, L.M.; et al. Incidence and predictive biomarkers of Clostridioides difficile infection in hospitalized patients receiving broad-spectrum antibiotics. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2240–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, W.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Meng, L.; Yang, J. Clostridioides difficile contamination in the food chain: Detection, prevention and control strategies. Food Biosci. 2024, 58, 103680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmaseda, A.; Rozès, N.; Bordons, A.; Reguant, C. Simulated lees of different yeast species modify the performance of malolactic fermentation by Oenococcus oeni in wine-like medium. Food Microbiol. 2021, 99, 103839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toraño, P.; Oyón-Ardoiz, M.; Manjón, E.; Escribano-Bailón, M.T.; Bordons, A.; García-Estévez, I.; Rozès, N.; Reguant, C. Different composition of mannoprotein extracts and their beneficial effects on Oenococcus oeni and wine malolactic fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2025, 442, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristof, I.; Ledesma, S.C.; Apud, G.R.; Vera, N.R.; Aredes Fernández, P.A. Oenococcus oeni allows the increase of antihypertensive and antioxidant activities in apple cider. Helyon 2023, 9, e16806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Hong, X.; Xu, Z.; Liu, S.; Shi, K. Bioprospecting Indigenous Oenococcus oeni Strains from Chinese Wine Regions: Multivariate Screening for Stress Tolerance and Aromatic Competence. Foods 2025, 14, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantachote, D.; Ratanaburee, A.; Sukhoom, A.; Sumpradit, T.; Asavaroungpipop, N. Use of γ-aminobutyric acid producing lactic acid bacteria as starters to reduce biogenic amines and cholesterol in Thai fermented pork sausage (Nham) and their distribution during fermentation. LWT 2016, 70, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anumudu, C.K.; Miri, T.; Onyeaka, H. Multifunctional Applications of Lactic Acid Bacteria: Enhancing Safety, Quality, and Nutritional Value in Foods and Fermented Beverages. Foods 2024, 13, 3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, H.; Beresford, T.P.; Cotter, P.D. Health Benefits of Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) Fermentates. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Goat | Sheep | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Microorganisms | N = 10 | N = 10 | p-Value |

| Clostridioides difficile | 2.00 (0.96) a | 1.17 (1.18) a | 0.089 |

| Campylobacter coli | 2.69 (1.26) a | 1.52 (1.55) a | 0.089 |

| Chlamydia abortus | 0.01 (0.01) a | 0.00 (0.00) a | 0.6 |

| Campylobacter jejuni | 0.15 (0.09) a | 0.08 (0.08) a | 0.12 |

| Campylobacter lari | 0.08 (0.04) a | 0.04 (0.04) a | 0.029 |

| Clostridium botulinum | 0.43 (0.14) a | 0.27 (0.29) a | 0.2 |

| Clostridium perfringens | 3.39 (2.00) a | 0.05 (0.04) b | <0.001 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 2.53 (0.86) a | 2.82 (2.00) a | 0.7 |

| Escherichia coli | 1.97 (2.22) a | 6.14 (7.03) b | 0.029 |

| Listeria monocytogenes | 0.05 (0.03) a | 0.03 (0.02) a | 0.2 |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 0.05 (0.03) a | 0.03 (0.02) a | 0.089 |

| Levilactobacillus namurensis | 0.43 (0.21) a | 0.25 (0.24) a | 0.089 |

| Oenococcus oeni | 0.60 (1.01) a | 0.97 (1.06) a | 0.8 |

| Helicobacter pylori | 0.36 (0.66) a | 0.62 (0.61) a | 0.7 |

| Lactobacillus agrestimuris | 0.05 (0.03) a | 0.03 (0.03) a | 0.3 |

| Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus | 0.02 (0.02) a | 0.01 (0.01) a | 0.3 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 3.31 (1.64) a | 1.92 (1.71) a | 0.2 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 6.40 (3.10) a | 5.17 (2.37) a | 0.089 |

| Salmonella enterica | 0.26 (0.10) a | 0.22 (0.08) a | 0.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adje, Y.; Sessou, P.; Tegopoulos, K.; Hounmanou, Y.M.G.; Siskos, N.; Farmakioti, I.; Azokpota, P.; Farougou, S.; Baba-Moussa, L.; Skavdis, G.; et al. First Metagenomic Shotgun Sequencing Report on the Microbiome of Local Goat and Sheep Raw Milk in Benin for Dairy Valorization. DNA 2025, 5, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/dna5040058

Adje Y, Sessou P, Tegopoulos K, Hounmanou YMG, Siskos N, Farmakioti I, Azokpota P, Farougou S, Baba-Moussa L, Skavdis G, et al. First Metagenomic Shotgun Sequencing Report on the Microbiome of Local Goat and Sheep Raw Milk in Benin for Dairy Valorization. DNA. 2025; 5(4):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/dna5040058

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdje, Yvette, Philippe Sessou, Konstantinos Tegopoulos, Yaovi Mahuton Gildas Hounmanou, Nikistratos Siskos, Ioanna Farmakioti, Paulin Azokpota, Souaïbou Farougou, Lamine Baba-Moussa, George Skavdis, and et al. 2025. "First Metagenomic Shotgun Sequencing Report on the Microbiome of Local Goat and Sheep Raw Milk in Benin for Dairy Valorization" DNA 5, no. 4: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/dna5040058

APA StyleAdje, Y., Sessou, P., Tegopoulos, K., Hounmanou, Y. M. G., Siskos, N., Farmakioti, I., Azokpota, P., Farougou, S., Baba-Moussa, L., Skavdis, G., & Grigoriou, M. E. (2025). First Metagenomic Shotgun Sequencing Report on the Microbiome of Local Goat and Sheep Raw Milk in Benin for Dairy Valorization. DNA, 5(4), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/dna5040058