Seismic Response Evaluation of Isolated Bridges Equipped with Fluid Inerter Damper

Abstract

1. Introduction

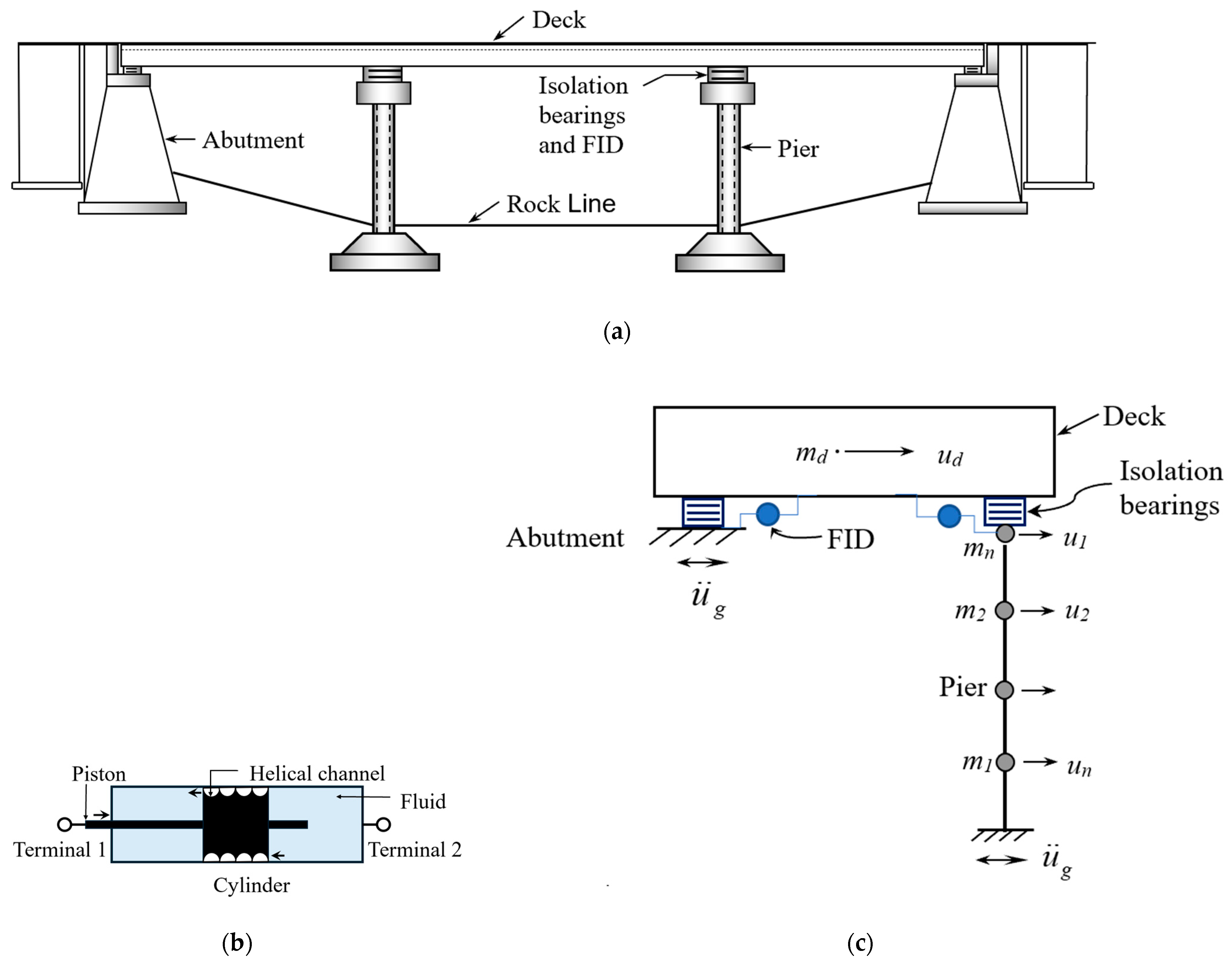

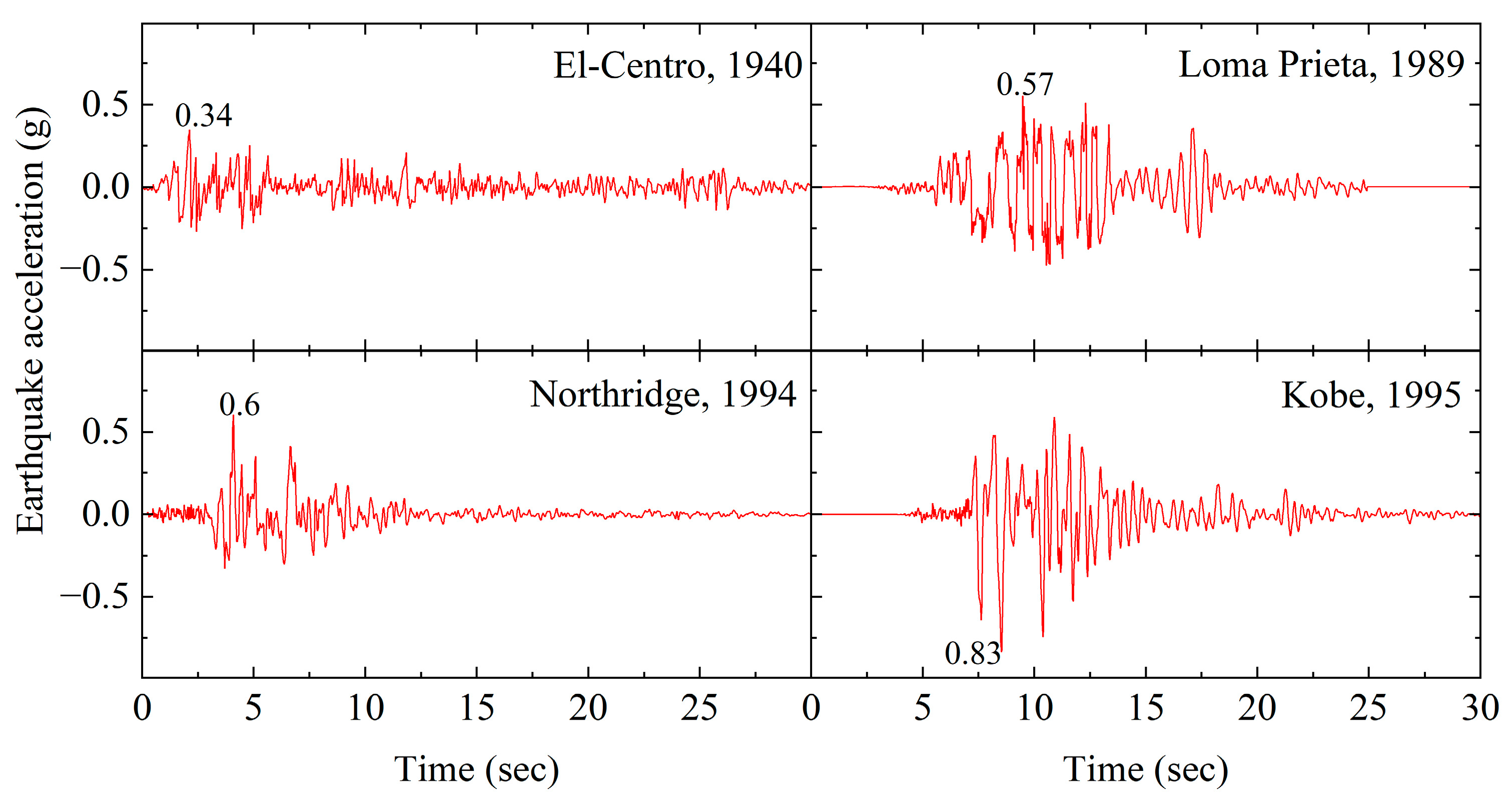

2. Analytical Modelling of Isolated Bridge System Integrated with FID

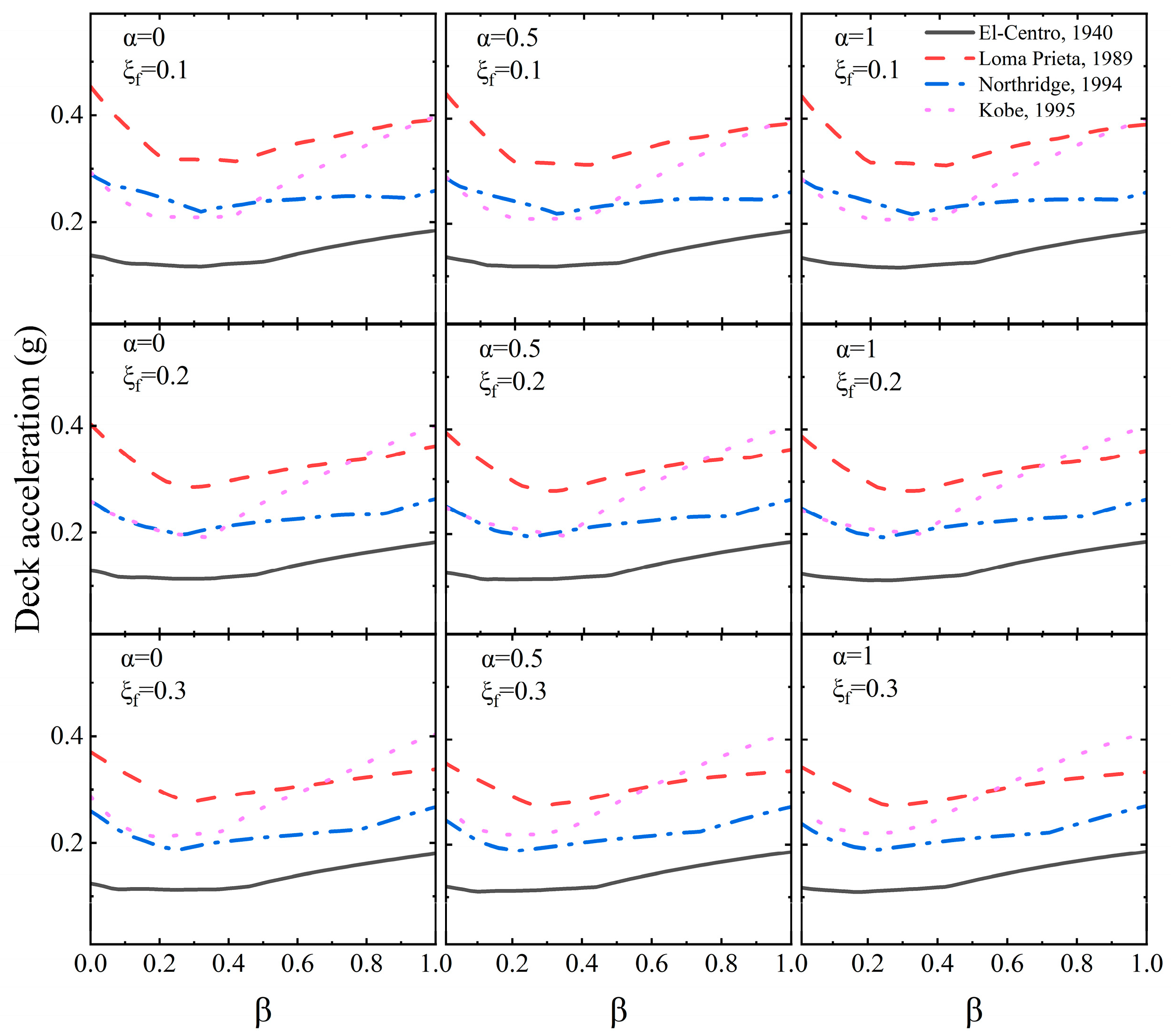

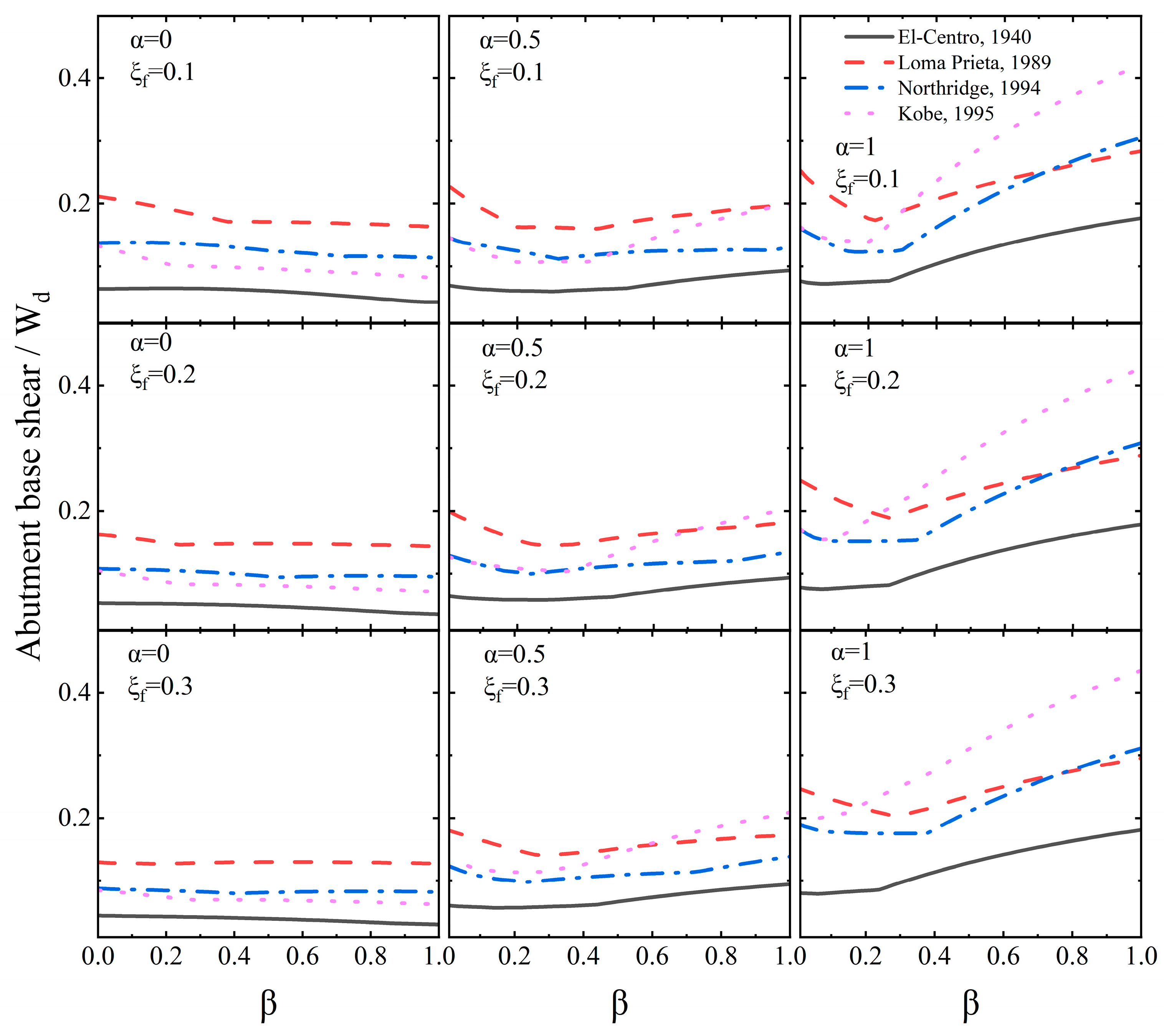

3. Seismic Response Results of the Isolated Bridge Equipped with FID

4. Conclusions

- Deck acceleration decreases with increasing inertance ratio up to an optimum range between 0.2 and 0.5, beyond which further increase results in amplification. The influence of inerter damping and placement factor remains comparatively limited across the examined earthquake records.

- Pier bearing displacement decreases with increasing inertance and is further reduced at higher inerter damping levels. At larger damping values, the response control becomes predominantly governed by damping effects, while the placement factor exerts negligible influence across the examined earthquake records.

- For pier-level placement of FID, the abutment base shear decreases steadily with increasing inertance and is further reduced at higher inerter damping. Conversely, for abutment-level placement, the abutment base shear decreases up to an optimum inertance and then increases, remaining largely insensitive to variations in inerter damping.

- For abutment-level placement of FID, the pier base shear remains largely insensitive to variations in inertance, although the effect of inerter damping becomes more pronounced at this location. For pier-level or combined placements, the pier base shear initially decreases with increasing inertance and subsequently increases at higher inertance values. These fluctuations are attributed to the dynamic interaction between the pier and the deck.

- The distribution of seismic forces is highly sensitive to the placement of FID, and achieving balanced performance requires the joint optimization of inertance, inerter damping, and placement configuration. Abutment placement is generally more effective for reducing pier base shear due to the greater stiffness of the abutments.

- For the considered cases, the FID consistently outperforms both conventional viscous dampers and the base-isolated bridge alone, consistently minimizing deck acceleration, limiting bearing displacement, and lowering base shear demands at both the abutments and piers, regardless of earthquake input or device placement. This performance advantage is further corroborated by the time-history response analyses for all cases.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Priestley, M.J.N.; Seible, F.; Calvi, G.M. Seismic Design and Retrofit of Bridges; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Madhekar, S.; Matsagar, V. Passive Vibration Control of Structures; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardoulias, A.; Arailopoulos, A.; Seventekidis, P. From binary to multi-class: Neural networks for structural damage classification in bridge monitoring under static and dynamic loading. Dynamics 2024, 4, 786–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.M.; Skinner, R.I.; Heine, A.J. Mechanisms of energy absorption in special devices for use in earthquake resistant structures. Bull. N. Z. Soc. Earthq. Eng. 1972, 5, 63–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, W.H. Lead-rubber hysteretic bearings suitable for protecting structures during earthquakes. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1982, 10, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, C. Seismic performance of tall pier bridges retrofitted with lead rubber bearings and rocking foundation. Eng. Struct. 2020, 212, 110529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsopelas, P.; Constantinou, M.C.; Kim, Y.S.; Okamoto, S. Experimental study of FPS system in bridge seismic isolation. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1996, 25, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.M. Aseismic base isolation: Review and bibliography. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 1986, 5, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soneji, B.B.; Jangid, R.S. Effectiveness of seismic isolation for cable-stayed bridges. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 2006, 06, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warn, G.P.; Ryan, K.L. A review of seismic isolation for buildings: Historical development and research needs. Buildings 2012, 2, 300–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, J.D.; Rodriguez-Marek, A. Characterization of forward-directivity ground motions in the near-fault region. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2004, 24, 815–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettis, A.; Di Mucci, V.M.; Ruggieri, S.; Uva, G. Seismic fragility and risk assessment of isolated bridges subjected to pre-existing ground displacements. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2025, 194, 109335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, B.F.; Nagarajaiah, S. State of the art of structural control. J. Struct. Eng. 2003, 129, 845–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappalardo, C.M.; Isola, G.; Donadio, A.; La Regina, R.; Berardi, V.P.; Guida, D. Technical design and virtual testing of a dynamic vibration absorber for the vibration control of a flexible structure. Dynamics 2025, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobarah, A.; Ali, H.M. Seismic performance of highway bridges. Eng. Struct. 1988, 10, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makris, N.; Kampas, G. Seismic protection of structures with supplemental rotational inertia. J. Eng. Mech. 2016, 142, 04016089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.C. Synthesis of mechanical networks: The inerter. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2002, 47, 1648–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, C.; Smith, M.C. Laboratory experimental testing of inerters. In Proceedings of the 44th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, Seville, Spain, 15 December 2005; pp. 3351–3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, C.; Houghton, N.E.; Smith, M.C. Experimental testing and analysis of inerter devices. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 2009, 131, 011001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangid, R.S. Performance and optimal design of base-isolated structures with clutching inerter damper. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2022, 29, e3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Domenico, D.; Ricciardi, G. Optimal design and seismic performance of tuned mass damper inerter (TMDI) for structures with nonlinear base isolation systems. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2018, 47, 2539–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangid, R.S. Seismic performance of a clutched inerter for structures with curved surface sliders. Structures 2023, 49, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Domenico, D.; Ricciardi, G. An enhanced base isolation system equipped with optimal tuned mass damper inerter (TMDI). Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2018, 47, 1169–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangid, R.S. Response of structures with clutching inertial system under near-fault motions. J. Struct. Des. Constr. Pract. 2026, 31, 04025109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.Z.Q.; Hu, Y. Inerter and Its Application in Vibration Control Systems; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagg, D.J. A review of the mechanical inerter: Historical context, physical realisations and nonlinear applications. Nonlinear Dyn. 2021, 104, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Bi, K.; Hao, H. Inerter-based structural vibration control: A state-of-the-art review. Eng. Struct. 2021, 243, 112655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makris, N.; Moghimi, G. Displacements and forces in structures with inerters when subjected to earthquakes. J. Struct. Eng. 2019, 145, 04018260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; De Domenico, D.; Li, C. Seismic resilient design of rocking tall bridge piers using inerter-based systems. Eng. Struct. 2023, 281, 115819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matin, A.; Elias, S.; Matsagar, V. Distributed multiple tuned mass dampers for seismic response control in bridges. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Struct. Build. 2020, 173, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Qiao, H.; De Domenico, D. Seismic protection of reinforced concrete continuous girder bridges with inerter-based vibration absorbers. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 164, 107526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangid, R.S. Seismic performance assessment of clutching inerter damper for isolated bridges. Pract. Period. Struct. Des. Constr. 2022, 27, 04021078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Domenico, D.; Deastra, P.; Ricciardi, G.; Sims, N.D.; Wagg, D.J. Novel fluid inerter based tuned mass dampers for optimised structural control of base-isolated buildings. J. Frankl. Inst. 2019, 356, 7626–7649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jiang, J.Z.; Titurus, B.; Harrison, A. Model identification methodology for fluid-based inerters. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2018, 106, 479–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, S.J.; Smith, M.C.; Glover, A.R.; Papageorgiou, C.; Gartner, B.; Houghton, N.E. Design and modelling of a fluid inerter. Int. J. Control 2013, 86, 2035–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.C.; Hong, M.F.; Lin, T.C. Designing and testing a hydraulic inerter. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2011, 225, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, N.D.; Wagg, D.; Tipuric, M.; Deastra, P. Semi-active inerters using magnetorheological fluid: A feasibility study. In Active and Passive Smart Structures and Integrated Systems XII; Erturk, A., Ed.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2018; p. 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.S.; Sheng, L.H. Equivalent elastic seismic analysis of base-isolated bridges with lead-rubber bearings. Eng. Struct. 1994, 16, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicleli, M.; Albhaisi, S.; Mansour, M.Y. Static soil–structure interaction effects in seismic-isolated bridges. Pract. Period. Struct. Des. Constr. 2005, 10, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonari, S.; Nicoletti, V.; Martini, R.; Gara, F. Dynamics of bridges during proof load tests and determination of mass-normalized mode shapes from OMA. Eng. Struct. 2024, 310, 118111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheibani, M.; Ghorbani-Tanha, A.K. Obtaining mass normalized mode shapes of motorway bridges based on the effect of traffic movement. Structures 2021, 33, 2253–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnini, L.C.; Solari, G. Stochastic analysis of the linear equivalent response of bridge piers with aseismic devices. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1999, 28, 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Tan, P.; Nagarajaiah, S.; Zhang, J. Benchmark structural control problem for a seismically excited highway bridge-part I: Phase I problem definition. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2009, 16, 509–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clough, R.W.; Penzien, J. Dynamics of Structures, 3rd ed.; Computers and Structures: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

| El-Centro, 1940 | ||||||||

| (g) | (mm) | Va/Wd | Vp/Wd | |||||

| BIS | 0.155 | 146.3 | 0.078 | 0.093 | ||||

| FID | VD | FID | VD | FID | VD | FID | VD | |

| BIS + FID (α = 0, = 0.15, β = 0.45) | 0.121 | 0.132 | 102.4 | 108.3 | 0.055 | 0.058 | 0.083 | 0.091 |

| BIS + FID (α = 0.5, = 0.2, β = 0.25) | 0.114 | 0.127 | 94.2 | 97.0 | 0.058 | 0.064 | 0.068 | 0.078 |

| BIS + FID (α = 1, = 0.1, β = 0.2) | 0.118 | 0.135 | 120.2 | 118.1 | 0.075 | 0.076 | 0.073 | 0.078 |

| Loma Prieta, 1989 | ||||||||

| (g) | (mm) | Va/Wd | Vp/Wd | |||||

| BIS | 0.558 | 530.4 | 0.283 | 0.258 | ||||

| FID | VD | FID | VD | FID | VD | FID | VD | |

| BIS + FID (α = 0, = 0.15, β = 0.45) | 0.311 | 0.425 | 299.6 | 344.2 | 0.159 | 0.184 | 0.215 | 0.266 |

| BIS + FID (α = 0.5, = 0.2, β = 0.25) | 0.288 | 0.393 | 275.1 | 296.8 | 0.147 | 0.199 | 0.184 | 0.208 |

| BIS + FID (α = 1, = 0.1, β = 0.2) | 0.316 | 0.443 | 351.4 | 386.1 | 0.176 | 0.253 | 0.198 | 0.193 |

| Northridge, 1994 | ||||||||

| (g) | (mm) | Va/Wd | Vp/Wd | |||||

| BIS | 0.353 | 339.5 | 0.180 | 0.197 | ||||

| FID | VD | FID | VD | FID | VD | FID | VD | |

| BIS + FID (α = 0, = 0.15, β = 0.45) | 0.224 | 0.272 | 209.5 | 228.9 | 0.111 | 0.121 | 0.146 | 0.180 |

| BIS + FID (α = 0.5, = 0.2, β = 0.25) | 0.195 | 0.253 | 192.6 | 200.5 | 0.100 | 0.129 | 0.133 | 0.141 |

| BIS + FID (α = 1, = 0.1, β = 0.2) | 0.242 | 0.284 | 253.4 | 254.5 | 0.123 | 0.160 | 0.139 | 0.144 |

| Kobe, 1995 | ||||||||

| (g) | (mm) | Va/Wd | Vp/Wd | |||||

| BIS | 0.340 | 317.0 | 0.172 | 0.181 | ||||

| FID | VD | FID | VD | FID | VD | FID | VD | |

| BIS + FID (α = 0, = 0.15, β = 0.45) | 0.232 | 0.275 | 165.0 | 215.3 | 0.089 | 0.117 | 0.171 | 0.192 |

| BIS + FID (α = 0.5, = 0.2, β = 0.25) | 0.206 | 0.251 | 155.3 | 186.7 | 0.107 | 0.126 | 0.150 | 0.158 |

| BIS + FID (α = 1, = 0.1, β = 0.2) | 0.208 | 0.285 | 189.5 | 237.9 | 0.139 | 0.162 | 0.136 | 0.153 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meena, S.L.; Jangid, R.S. Seismic Response Evaluation of Isolated Bridges Equipped with Fluid Inerter Damper. Dynamics 2025, 5, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/dynamics5040052

Meena SL, Jangid RS. Seismic Response Evaluation of Isolated Bridges Equipped with Fluid Inerter Damper. Dynamics. 2025; 5(4):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/dynamics5040052

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeena, Sunder Lal, and Radhey Shyam Jangid. 2025. "Seismic Response Evaluation of Isolated Bridges Equipped with Fluid Inerter Damper" Dynamics 5, no. 4: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/dynamics5040052

APA StyleMeena, S. L., & Jangid, R. S. (2025). Seismic Response Evaluation of Isolated Bridges Equipped with Fluid Inerter Damper. Dynamics, 5(4), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/dynamics5040052