Abstract

Climate change education (CCE) is increasingly recognized as a key lever for responding to the climate crisis, yet its implementation in schools often remains fragmented and weakly transformative. This review synthesizes international research on CCE in secondary education, focusing on four interconnected domains: students’ social representations of climate change (SRCC), curricular frameworks, teaching practices and teacher professional development, and emerging pathways towards transformative, justice-oriented CCE. A narrative review of empirical and theoretical studies reveals that students’ SRCC are generally superficial, fragmented and marked by persistent misconceptions, psychological distance and low perceived agency. Curricular frameworks tend to locate climate change mainly within natural sciences, reproduce deficit-based and behaviorist models and leave social, political and ethical dimensions underdeveloped. Teaching practices remain predominantly transmissive and science-centered, while teachers report limited training, time and institutional support, especially for addressing the affective domain and working transdisciplinarily. At the same time, the literature highlights promising directions: calls for an “emergency curriculum” and deeper curricular environmentalization, the potential of socio-scientific issues and complexity-based approaches, narrative and arts-based strategies, school gardens and community projects, and growing attention to emotions, hope and climate justice. Drawing on a narrative and integrative review of empirical and theoretical studies, the article identifies recurrent patterns and gaps in current CCE research and outlines priorities for future inquiry. The review argues that bridging the knowledge–action gap in schools requires aligning curriculum, pedagogy and teacher learning around four key principles—climate justice, collective agency, affective engagement and global perspectives—and outlines implications for policy, practice and research to support more transformative and socially just CCE.

1. Introduction

Climate change (CC) is now widely recognized as a global, multidimensional and interconnected threat that affects ecological, social, economic and cultural systems in deeply uneven ways [1,2]. It is often described as a “wicked problem”, characterized by scientific uncertainty, multiple causes and stakeholders, and the absence of simple, technical solutions [3]. The crisis has also been described as a “triple helix” of scientific, political and social dimensions, a framing that underscores both its global reach and the need for responses that move beyond technological innovation [4]. Beyond its biophysical and techno-scientific dimensions, CC is increasingly understood as a systemic crisis—one rooted in cultural values, identity, and anthropocentric worldviews—requiring deep shifts in how societies imagine human–nature relationships and envision alternative futures [5,6]. Since the Paris Agreement explicitly called for education, public awareness and capacity building as key pillars of climate action, climate change education (CCE) has emerged as a distinct field within educational research and practice [7].

Within this context, CCE is increasingly framed as a societal mission that must be complexity-oriented, intergenerational and interdisciplinary [8,9]. Rather than focusing only on transmitting climate science, CCE is expected to support an ecosocial transition and nurture sustainable “good living”, linking climate literacy with values, participation and cultural change [8,10]. When CCE presents the issue as a set of decontextualized facts, its ethical and political meaning is diminished [11]. Consistent with this, research in different countries shows that knowing about CC does not automatically lead to coherent practices: young people often report high levels of concern but only limited behavioral change, revealing a persistent knowledge–action gap [12,13,14]. Large-scale surveys also show that environmental knowledge and attitudes predict pro-sustainability behavior only weakly [15]. This tension is particularly acute in adolescence, when secondary students are intensively constructing their identities, are highly exposed to news and social media, and begin to socialize climate-related knowledge among peers, so that school learning becomes only one of several, and sometimes conflicting, sources of meaning.

However, environmental concern is shaped by social trust, media exposure and direct experience of climate impacts, while contrasting effects of secondary and tertiary education point to cultural polarization and technophilic optimism [16]. To address this gap, CCE must therefore work on motivation, ethics and action, reducing psychological distance, fostering critical reflection and emotional engagement, strengthening civic empowerment, and rethinking curricular approaches accordingly [17,18,19,20].

These demands resonate with broader debates, which call for pedagogies that are explicitly transformative and promote complexity-oriented, systemic, critical and creative thinking [21]. Sustainability itself is understood as a sophisticated educational construct that should be connected, through knowledge, values and practices, to equity, future-oriented thinking and social justice, rather than reduced to generic environmental awareness [22]. From this standpoint, CCE combines two interrelated dimensions: educating about climate—grounded in rigorous scientific literacy—and educating for change, which brings ethical, civic and participatory dimensions into dialogue with scientific knowledge [23,24]. Rather than privileging one over the other, effective CCE requires weaving together conceptual understanding and holistic pedagogies that foster critical citizenship. In line with this, the literature increasingly converges on four key pillars for CCE: critical understanding of climate systems and drivers, cooperative and collective action, ecosocial ethics [8,25] and the capacity to adapt and build community resilience [10,26].

Several global and regional reviews have attempted to map this emerging field. They highlight, among other aspects, the importance of analyzing student attributes and representations, pedagogical approaches and teacher knowledge as interconnected dimensions of CCE [20]. More recent syntheses emphasize the need for interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary approaches, as well as stronger curricular integration across subjects and school levels [9,27]. At the same time, they point to enduring tensions and controversies: between individual behavior change and structural transformation, between “neutral” scientific teaching and explicitly justice-oriented education, and between policy discourses that promote CCE and the limited support actually provided to schools and teachers [4,8].

Building on this body of work, the present review focuses specifically on CCE in school settings and examines four interrelated domains: students’ social representations of climate change (SRCC), curricular frameworks, teaching practices and teacher professional development, and emerging pathways towards transformative, justice-oriented CCE and eco-citizenship. Secondary education is a particularly strategic level for this analysis, as it is a period in which young people’s increasing autonomy, digital connectivity and civic awareness intersect with intensified exposure to climate information and with the knowledge–action gap outlined above. It identifies recurring gaps across these domains: superficial and often distorted student understandings, fragmented and weakly implemented curricular provisions, predominantly transmissive, science-centered pedagogies, and insufficient institutional support for teachers. In doing so, this review extends and complements recent systematic and scoping syntheses by concentrating especially on CCE at the secondary level and by analyzing how these four domains, often examined separately, jointly contribute to, and may help address, the persistent knowledge–action gap highlighted above.

Rather than conducting an exhaustive systematic review, we adopted a narrative and integrative approach, combining systematic search procedures with iterative, theory-driven selection in order to construct a conceptually rich but manageable corpus. We focused on empirical and conceptual contributions on CCE and closely related fields (environmental education and education for sustainable development) in school settings, with particular emphasis on secondary education, while also including relevant research on initial and in-service teacher education, published mainly between 2000 and 2025.

The literature was identified through iterative keyword searches in major education and interdisciplinary databases (Web of Science Core Collection, Scopus, ERIC, and Google Scholar), complemented by backward and forward citation tracking and targeted retrieval of key policy documents and competence frameworks. Search strings combined terms such as climate change education, education for sustainable development, environmental education, secondary education, teacher education, social representations, curriculum, teaching practices, and climate justice. This identification stage yielded 256 records (Table 1). Following the removal of duplicates, titles and abstracts were screened to exclude purely technical climate science publications, narrowly sectoral studies, and sources with only tangential educational relevance or outside the four focal domains of the review. This screening stage resulted in the exclusion of 180 records. The remaining 134 publications were assessed through full-text reading to determine their substantive empirical or theoretical contribution to at least one of the focal domains (students’ social representations of climate change, curriculum frameworks, teaching practices, or teacher education). Based on this eligibility assessment, 21 sources were excluded due to limited analytical depth or insufficient thematic fit. The final corpus therefore comprised 114 sources, including peer-reviewed journal articles and scholarly book chapters, which were prioritized for evidentiary claims, as well as a smaller set of policy reports and competence frameworks used primarily for contextual and analytical framing.

Table 1.

Search and selection overview.

Geographically, the corpus is dominated by studies conducted in Europe and Latin America, with a smaller number of contributions from other world regions. This reflects both the concentration of CCE research in these contexts and the language filters applied, and it constitutes a limitation that is taken up in the discussion and conclusions below.

2. SRCC Among Secondary School Students

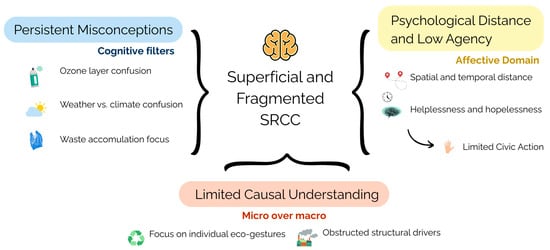

Research on the SRCC among secondary school students is crucial for understanding how young people make sense of a complex and highly mediatized scientific phenomenon, and how this meaning-making shapes their willingness to act [28,29,30]. Cross-cultural studies reveal a notable homogeneity in the structure of these SRCC despite sociocultural differences [31,32], as well as a superficial, fragmented, and insufficient level of knowledge for informed decision-making [29,32,33].

Overall, students tend to learn about CC as a global environmental problem reduced to extreme atmospheric events and their visible consequences [34,35,36]. This hegemonic representation privileges isolated biophysical aspects and omits both the social perspective and the systemic ecological functioning of climate-related processes [28,30,32]. Students generally attribute CC consequences to individual behaviors—use of plastics, waste production, generic “pollution”—while macro-level drivers linked to economic or energy systems remain blurred [29,34,37]. This micro-level focus reflects a lack of systemic thinking that limits students’ understanding of climate complexity [32,38].

SRCC are also characterized by the widespread and persistent presence of alternative conceptions, shared by both students and teachers [39]. The most recurrent include confusion between CC and ozone depletion [29,35,38], often associated with skin cancer risk [32,39]; attributing CC to simple waste accumulation [37]; identifying CC with daily weather variation [28,36,38]; conceiving the greenhouse effect as either exclusively harmful or as identical to CC [38,40]; and linking it to unrelated phenomena such as tectonic activity, acid rain or specific diseases [32,38]. Such persistence shows that pre-existing beliefs act as assimilation filters that limit the integration of scientific knowledge [29,34], making the explicit correction of these misconceptions—particularly in teacher education—a critical priority [22,41].

Beyond cognitive aspects, SRCC incorporate affective and evaluative components that shape risk perception and emotional responses [40]. CC is represented as a global threat, or even as a deadly “beast” [37], yet simultaneously perceived as a distant phenomenon in time and space [28,36,42]. This psychological distance—strongly documented among both students and teachers—reinforces the belief that impacts will be more severe for future generations than for themselves [39,43]. These emotional responses are often intensified by the lack of structured opportunities in schools to acknowledge and work through climate-related feelings, which contributes to students’ sense of overwhelm and disengagement [25].

As a result, many students perceive individual action as irrelevant and externalize responsibility to governments, companies or more polluting countries [28,32,34,44]. This lack of agency is reinforced by feelings of helplessness and hopelessness [36,42], which reduce proposed responses to low-impact individual pro-environmental gestures [29,34,42]. Figure 1 summarizes patterns repeatedly reported in the literature on secondary students’ social representations of climate change.

Figure 1.

Conceptual architecture of Secondary Students’ Social Representation of Climate Change (SRCC).

Formal education contributes only marginally to transforming these representations. Thus, the media, which are the main source of climate information for young audiences [45,46], often simplify the phenomenon through emotionally charged imagery or catastrophic narratives that, over time, generate fatigue and disengagement [46]. Media practices can also dilute scientific consensus when “balance” leads to the inclusion of skeptical or denialist voices [47]. These dynamics raise the question of how far formal curriculum frameworks are able—or unable—to counteract such fragmented representations and support more critical, systemic understandings of CC. Research consistently shows that schooling has minimal influence on SRCC and students’ willingness to act, largely because a deficit-based model and a tendency to promote simplified, individualized eco-gestures prevail, prioritizing decontextualized personal actions while avoiding engagement with the socio-structural roots of CC [4]. SRCC also vary by academic track—with differences between science and humanities students—and are strongly shaped by external sources such as media and youth activism [38].

3. Curriculum Frameworks and the Structural Limits of CCE

Current curricular frameworks have integrated sustainability and CC slowly and only in a fragmented manner, often through isolated “capsules” that fail to transform the underlying structure of the curriculum [21,48]. School systems largely maintain a scientific-literacy logic centered on technical content, with CC located mainly within natural sciences and sustained by a deficit model that assumes more scientific information will generate more responsible behavior [4,45,49]. This configuration restricts opportunities to address social, economic, and political dimensions of the phenomenon [4,25]. Within this framework, CCE remains concentrated primarily in science subjects and struggles to build solid links with social sciences or citizenship education, while classroom practice tends to prioritize positivist knowledge transmission [9,25,38].

This configuration risks generating a form of “paradigmatic blindness” that obscures the less visible structural roots of CC and limits the curriculum’s capacity to question the dominant development model based on unlimited growth and fossil fuels [25,45]. Consequently, various authors call for deeper curricular environmentalization processes, moving beyond the accumulation of projects towards a comprehensive reorientation of educational aims, content, and assessment criteria [8,21,48].

Against this backdrop, the notion of an “emergency curriculum” has been proposed—one that positions the climate and ecological crisis at the center of educational priorities and redefines curricular frameworks in line with the Paris Agreement [4,7]. Such a curriculum would need to address the socio-ecological complexity of the crisis and integrate scientific, political and ethical dimensions, moving beyond purely informational approaches towards social transformation and critical eco-citizenship [8,23,25]. From this perspective, approaching the climate crisis through the curriculum becomes not only an environmental issue, but also a matter of global justice and human rights, requiring curricular orientations that link local and global scales and confront inequalities and historical responsibilities [25,45]. In practice, this kind of emergency curriculum is exemplified by whole-school projects where a concrete local issue becomes the organizing focus for cross-curricular work. For instance, conservation projects that combine scientific study of local biodiversity with persuasive writing to community actors and concrete interventions in the school or neighborhood illustrate how disciplinary learning can be tightly coupled with justice-oriented climate action [50]. Recent proposals insist that CCE cannot remain confined to science and call for an “environmental lens” across all subjects so that each area clarifies its contribution to knowledge, values and competences for sustainability [9,50]. This aligns with international frameworks such as GreenComp, which defines four interconnected competence areas—embracing sustainability values, understanding complexity, envisioning sustainable futures and acting for sustainability—shifting the focus from conceptual understanding to the capacity to act [51]. Curriculum reorientation therefore requires a competence-based, transdisciplinary approach that integrates scientific, epistemological and psychosocial dimensions, articulating CC complexity through ecological balance, planetary boundaries and sociopolitical controversies [20,25,52,53,54].

CCE research also examines how curricular frameworks support cross-cutting, interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary integration, highlighting significant tensions between discourse and practice [25,27]. At the policy level, CCE is often framed as interdisciplinary and cross-curricular, yet in practice this frequently translates into isolated, low-status activities that are attached to a single subject, remain weakly assessed and do not substantially reshape the core curriculum [55,56]. Conversely, some whole-school or project-based initiatives adopt holistic, action-oriented pedagogies but engage only superficially with disciplinary knowledge on climate and sustainability, limiting students’ capacity to develop rigorous and systemic understandings [57]. When CC remains confined to natural sciences, it becomes difficult to connect with geographical, economic, historical or philosophical knowledge—fields essential for addressing territorial, economic and political dimensions of the crisis [9,34]. Recent studies show that CC is often approached descriptively and through physical processes, while students’ SRCC continue to overlook structural roots and socio-spatial inequalities [25,58]. Complementarily, mitigation is commonly framed in curricular materials through economic dimensions—production, consumption, energy markets—and political dimensions—regulation, governance and international agreements—yet these elements are rarely integrated into a systemic reading that connects lifestyles, productive models and regulatory frameworks [4,59].

Research into CCE indicates that teachers rely heavily on curricular guidance when attempting interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary work; where curricula explicitly position sustainability as a structuring axis, it is more likely that bridges between subject areas emerge and that learning sequences link scientific knowledge with socio-economic analysis and civic participation [27,54]. Conversely, the absence of clear guidelines reinforces the gap between the official curriculum and the “parallel curriculum” young people construct through media and social networks, deepening the disconnect between formal schooling and the societal urgency of the climate crisis [4,25,46]. Altogether, the literature points to the need for curricular environmentalization processes that position CC as a complex socio-ecological problem shared across all disciplines and that make explicit the interdependence of ecological, economic, political and cultural dimensions within and beyond school [21,23,48].

4. Teaching Practices and Professional Development in CCE

Teachers generally acknowledge CC as a serious global problem, yet tend to approach it mainly through an ecological and scientific lens that emphasizes environmental protection while relegating social, economic and ethical dimensions to a secondary level [37,60]. Although teachers’ conceptions are often complex and multidimensional, their practices frequently rely on simpler conservationist and resource-oriented approaches focused on the 3Rs (reduce, reuse, recycle) [61], thereby reinforcing the deficit-based model already described above [62]. Resulting practices privilege biophysical causes and environmental impacts, while rarely framing CC as a matter of justice, rights or power, as proposed in ecosocial approaches [4,8,25]. Many teachers value critical thinking and evidence-based instruction but tend to avoid political, ethical or values-based dimensions, keeping CCE largely cognitive and weakly oriented towards collective action [63].

At the same time, students identify teachers as one of the most trusted sources of information on CC, ranking them above media and social networks, which highlights their potential role as rigorous environmental leaders in the classroom [64]. Some teachers argue that their role should explicitly incorporate climate justice and civic participation, pointing towards a more openly eco-citizenship-oriented professional identity [65].

A major cause of stagnation in this direction is the lack of systematic training in CC and sustainability. Both in-service and pre-service teachers report insufficient preparation—scientifically and pedagogically—and professional learning is often self-taught [22,39,66] and dependent on highly committed individuals rather than on structured institutional policies [67]. Additional constraints such as limited time, scarce resources and weak organizational support further prevent teachers from moving beyond a superficial treatment of basic concepts toward approaches that address human causes, social implications and possible solutions [66,68]. Research therefore emphasizes the need for initial and ongoing training that strengthens climate literacy, addresses alternative conceptions and builds didactic competences for teaching complex problems [22,39,58]. Importantly, research also stresses that effective CCE does not require teachers to master every scientific aspect of CC, but rather to collaborate, engage in interdisciplinary dialogue and understand how each disciplinary contribution enriches students’ overall comprehension of the issue [55].

In this context, training in active methodologies emerges as a key field: teachers often show greater interest in learning pedagogical strategies than in deepening specific climate content, signaling an opportunity to connect methodological innovation with CCE [1]. Collaboration between researchers and teachers—through co-designed projects, shared materials and reflective spaces—has been identified as a promising path for strengthening teacher confidence and embedding CC in the curriculum in a stable way [39,48,69].

Regarding teaching practices, several studies highlight the strong potential of socio-scientific issues (SSI) approaches for CCE, as they integrate scientific knowledge, values, controversy and decision-making in authentic contexts [34,70]. However, the lack of time, curricular pressure and discomfort with controversy remain obstacles to sustained SSI implementation [34,66]. In parallel, complexity-based approaches encourage placing students in real socio-environmental problem situations, using controversies, interdisciplinary work and tools such as the “Vector Idea” to shift worldviews and interpretive frameworks among both teachers and learners [52]. Inquiry and modeling also show strong potential in teacher education, naturally aligning with the teaching of SSI and socio-ecological complexity [71]. More broadly, active and experiential methodologies that combine personal relevance, hands-on learning and community or school action projects appear particularly effective for fostering action competences and promoting sustained behavioral change [54,72]. Within this family of approaches, gamified and challenge-based activities can also strengthen students’ motivation and engagement in sustainability actions [73]. School gardens are frequently cited as powerful learning environments for sustainability, agency and care, and for anchoring learning in everyday contexts [74,75]. Other experiences explore the use of art to design and assess CC modules, generating strong emotional, creative and reflective engagement among students [76]. Moreover, arts and humanities offer an underused potential for CCE, enabling engagement that ranges from simple communication to critical dialogue and, at its deepest, transformative meaning-making [77].

The use of narrative-based strategies—shown to be effective in science education [78,79]—is essential in CCE to help close the “action gap” and move beyond approaches centered on information deficits and catastrophist narratives [80,81]. Structured, solution-focused stories have been found to be more effective than purely informational messages in promoting pro-environmental behavior, as they support experiential processing, reduce feelings of helplessness and are associated with higher motivation for climate action [80,82]. To strengthen students’ agency, it is particularly valuable to provide narratives of people taking positive steps in concrete contexts, since actions can influence beliefs through self-persuasion processes [83]. Intergenerational and cross-cultural storytelling further helps to integrate diverse family experiences—especially from migrant backgrounds—supporting critical understandings of climate justice and fostering empathy [84].

Moreover, complexity-oriented CCE requires the inclusion of indigenous [85] and traditional [86] knowledge and cultural practices, which can support resilience and collective action capacities. Participatory storytelling focused on community adaptation and resilience promotes mutual learning and offers emotional “containers” to engage with climate topics in an emotionally intelligent way [87]. Tools such as scientific comics, which combine visual storytelling with science communication devices (maps, diagrams), have proven effective in improving understanding, content retention and environmental concern by depicting stakeholder actions in an integrated way [88]. Finally, narrative interventions oriented toward the future—such as imagining a carbon-neutral city—can reduce psychological distance and increase action competence [89], using narrative frameworks to balance paradigmatic (logical-scientific) thinking with narrative (experiential-causal) thinking and foster more complex understandings [90].

Teaching practices and teacher training also vary across disciplines, with notable differences between chemistry, biology and physics teachers—an aspect with important implications for designing disciplinary and transversal sustainability education programs [50,63]. Within this context, teachers require curricular frameworks that legitimize an “environmental lens” across subjects and guide curricula towards an emergency response to the socio-ecological crisis [45,67].

Finally, the affective dimension emerges as critical in both practice and teacher education: many teachers feel unprepared to address emotions such as sadness, eco-anxiety or fatalism associated with CC, despite recognizing their importance in students’ responses [25]. Research shows that explicitly attending to emotions can enhance engagement and the capacity to sustain difficult conversations, provided they are approached constructively and with an orientation towards hope [71]. Teachers’ differing beliefs about emotions strongly shape whether they avoid, minimize or actively work with students’ climate-related feelings [91]. Yet, while critical thinking and community participation are widely emphasized in sustainability education, affective and transformative capacities remain largely overlooked in teacher professional development [92]. Recent contributions also outline concrete modules that teacher education can adopt to work explicitly with eco-anxiety and hope. These include meta-emotion activities in which teachers examine their own beliefs about “negative” emotions and practice validating students’ distress before moving towards action; inquiry and modelling sequences that deliberately link learning climate science with guided reflection on how increased understanding can reduce paralysis and build confidence; structured strategies for naming emotions, cultivating critical (rather than naïve) hope and using artistic expression as a space for processing climate-related feelings; and transformative projects in which future teachers collaborate with local actors on real sustainability problems, using the discomfort and frustration that emerge as starting points for critical reflection and collective action [8,71,91,92]. Consequently, professional development in CCE should include not only scientific content and didactic strategies but also tools to address the emotional dimension and to support long-term personal and collective transformation [8,25].

6. Conclusions and Prospects

This review has synthesized a substantial body of evidence demonstrating the challenges and opportunities inherent to CCE in secondary schooling, with particular attention to the persistent gap between knowledge and action. The analysis indicates that students’ SRCC often remain superficial, fragmented and marked by conceptual confusions. The prevalence of deficit-based approaches and of tendencies that promote simplified, individualized eco-gestures further limits systemic understanding and constrains civic engagement with the structural roots of the problem.

The overarching thread emerging from the literature is that overcoming these limitations requires a transformative approach that places climate justice at its core. CCE must move beyond narrow, technocratic forms of scientific transmission and, instead, cultivate a complex, inquiry-based and critically grounded understanding of climate systems—an approach aligned with a didactics of CC that links scientific literacy with collective action and social transformation. This reorientation can be articulated around four key dimensions: advancing climate justice (by confronting inequalities and historical responsibilities), fostering collective agency (enabling students to experience themselves as agents of change), engaging the affective domain (channeling emotions such as eco-anxiety toward action and hope), and adopting a glocal perspective (examining the crisis through the articulation of local and global scales). Crucially, this transformative orientation cannot replace rigorous scientific learning; rather, it depends on deepening students’ conceptual understanding and their capacity to reason critically and creatively about climate processes. Without this epistemic foundation, action risks becoming superficial or disconnected from the complexities of climate science.

From a pedagogical standpoint, it is essential to adopt methodologies that support these dimensions. Such methodologies must integrate robust scientific inquiry with participatory, value-based learning, ensuring that action is always anchored in well-constructed knowledge. Active strategies such as SSI and complexity-based approaches are fundamental for engaging students in authentic controversies and decision-making processes. Within this context, constructive narratives emerge as a particularly relevant catalyst, as they have been shown to be more effective than purely informational messages in promoting action and reducing feelings of helplessness.

For these approaches to succeed, the review also highlights the indispensable role of educators as critical mediators. The practical challenges are significant: teachers often lack systematic training, time and resources to address the complexity of CC in a transdisciplinary manner, and many feel particularly unprepared to manage affective dimensions such as eco-anxiety in the classroom. Professional development should therefore aim to strengthen both scientific literacy and didactic competences for working with complex problems, explicitly integrating emotional work with an orientation toward active hope. Yet this professional growth cannot be understood as an individual effort. It requires schools to create and sustain institutional conditions that make it possible: protected time for collaboration and reflection, organizational cultures that value innovation and continuous learning, and pedagogical leadership capable of guiding a shared vision of the importance of CCE.

In interpreting this review, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, this is a narrative, non-systematic synthesis; although we sought to construct a theoretically rich and representative corpus through iterative database searches and citation tracking, we did not aim for exhaustive coverage, and some relevant studies may have been omitted. Second, the corpus is shaped by language filters: we focused primarily on publications in English and Spanish and selectively included work in Portuguese and French, so research published in other languages remains largely outside our scope. Relatedly, the literature reviewed is geographically concentrated in Europe and Latin America, with more limited representation from other world regions; this reflects both the distribution of CCE research and the search criteria applied, and it constrains the extent to which the patterns identified can be generalized globally. Third, we privileged peer-reviewed empirical and conceptual contributions in school and teacher-education settings, with a particular emphasis on secondary education; as a result, practice-oriented reports, gray literature and work on early childhood or vocational education are only marginally reflected. Finally, our analytic focus on four domains and on justice-oriented, transformative approaches may foreground certain questions (for example, social representations, eco-citizenship, agency and emotions) over others, and future reviews using different lenses or more formal systematic procedures could refine, challenge or extend the patterns identified here.

Looking ahead, the research agenda must move beyond primarily descriptive studies. There is an urgent need for robust research designs that can clarify how different pedagogical strategies foster agency, deep understanding and long-term retention; for example, which combinations of SSI, narrative-based and complexity-oriented approaches most effectively support sustained behavioral change, under what conditions, and for which groups of students? Equally important is investigating how structuring full curricula as coherent, purpose-driven stories can maximize motivation and sustained engagement; future studies might ask how narrative coherence interacts with assessment practices and school cultures, and whether such designs differentially benefit students with diverse backgrounds and prior achievement. Tools such as EO and the integration of IK also represent promising avenues to strengthen glocal connections and reinforce community resilience, raising further questions about how these resources shape students’ glocal understandings and their participation in community-based climate action.

In sum, the path forward for CCE involves balancing scientific rigor with social imagination, and cognitive depth with emotional resonance. A reflective integration of emerging pedagogical approaches—supported by a solid research agenda and coherent institutional backing—can empower students not only to understand climate science but also to see themselves as critical ecological citizens and active participants in the necessary socio-ecological transformation. Ultimately, transformative climate action in education requires an interplay between epistemic rigor and civic engagement, ensuring that agency emerges from knowledge, critique and creativity rather than from activism detached from scientific understanding.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.G.-B., G.C.-S., G.J.-V. and M.E.-P.; methodology, G.G.-B.; G.C.-S. and G.J.-V.; validation, G.C.-S. and G.J.-V.; formal analysis, G.G.-B., G.C.-S., G.J.-V. and M.E.-P.; investigation, G.G.-B.; resources, G.C.-S. and M.E.-P.; data curation, G.G.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, G.G.-B.; writing—review and editing, G.G.-B., G.C.-S., G.J.-V. and M.E.-P.; supervision, G.C.-S. and G.J.-V.; project administration, G.C.-S.; funding acquisition, G.C.-S., G.J.-V. and M.E.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca (AGAUR), grant number 2024 ARMIF 00003.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CC | Climate Change |

| CCE | Climate Change Education |

| EO | Earth Observation |

| ERIC | Education Resources Information Center |

| IK | Indigenous Knowledge |

| SRCC | Social Representations of Climate Change |

| SSI | Socio-Scientific Issues |

References

- Carbonell-Alcocer, A.; Gertrudix, M. Percepción docente sobre los recursos y metodologías eficaces para la educación ambiental para la sostenibilidad. Rev. Int. Educ. Justicia Soc. 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2021—The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, I.; Congreve, A. Teaching (super) wicked problems: Authentic learning about climate change. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2021, 45, 491–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudiano, É.J.G.; Cartea, P.Á.M.; Pérez, J.G. ¿Cómo educar sobre la complejidad de la crisis climática? Rev. Mex. Investig. Educ. 2020, 25, 843–872. [Google Scholar]

- Rissanen, I.; Aarnio-Linnanvuori, E.; Mansikka-aho, A. Worldview transformation in and through education. In Religion and Worldviews in Education, 1st ed.; Gearon, L., Kuusisto, A., Poulter, S., Toom, A., Ubani, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 194–206. [Google Scholar]

- Giusti, M.; Mäkelä, V.; Garbett Skagerlid, A.; Nagatsu, M. Shifting relationships with nature through schools: Exploring the social and spatial context for transformative sustainability education. Ecol. Soc. 2025, 30, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Report of the Conference of the Parties on Its Twenty-First Session, Held in Paris from 30 November to 13 December 2015; United Nations: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Agundez-Rodriguez, A.; Sauvé, L. L’éducation relative au changement climatique: Une lecture à la lumière du Pacte de Glasgow. Educ. Relat. Environ. 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Pérez, D.; Vilches, A. Cómo avanzar en la necesaria transición a la sostenibilidad. Ciênc. Educ. 2023, 29, e23027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasny, M.E.; DuBois, B. Climate adaptation education: Embracing reality or abandoning environmental values. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Säfström, C.A.; Östman, L. Transactive teaching in a time of climate crisis. J. Philos. Educ. 2020, 54, 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meira Cartea, P.Á. Climate change and education. In Climate Action. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Filho, L.W., Wall, T., Azeiteiro, U., Azul, A.M., Brandli, L., Özuyar, P.G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murga Menoyo, M.Á. Percepciones, valores y actitudes ante el desarrollo sostenible. Detección de necesidades educativas en estudiantes universitarios. Rev. Esp. Pedagog. 2008, 66, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumi Quispe, J.E. Actitudes y prácticas ambientales de la población urbana de Puno, altiplano andino. La Granja 2024, 39, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos-Merino, J.M.; Corbacho-Cuello, I.; Hernández-Barco, M. Analysis of sustainability knowingness, attitudes and behavior of a Spanish pre-service primary teachers sample. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiardi, D.; Morana, C. Climate change awareness: Empirical evidence for the European Union. Energy Econ. 2021, 96, 105163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, J.A. Understanding How Queensland Teachers’ Views on Climate Change and Climate Change Education Shape Their Reported Practices. Ph.D. Thesis, James Cook University, Douglas, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.H.; Pascua, L. Conceptualizing climate change education: An overview. In Proceedings of the SEAGA International Conference, Singapore, 27–30 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, A. Climate change education and research: Possibilities and potentials versus problems and perils? Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 767–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Pascua, L. The state of climate change education—Reflections from a selection of studies around the world. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2017, 26, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calafell, G.; Junyent, M. La idea vector y sus esferas: Una propuesta formativa para la ambientalización curricular desde la complejidad. Teor. Educ. Rev. Interuniv. 2017, 29, 189–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.; King, J.; Rieckmann, M.; Barth, M.; Büssing, A.; Hemmer, I.; Lindau-Bank, D. Teacher education for sustainable development: A review of an emerging research field. J. Teach. Educ. 2022, 73, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Gaudiano, E.J.; Meira Cartea, P.Á. Educación para el cambio climático: ¿educar sobre el clima o para el cambio? Perfiles Educ. 2020, 42, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caride Gómez, J.A.; Meira Cartea, P.Á. La educación ambiental en los límites, o la necesidad cívica y pedagógica de respuestas a una civilización que colapsa. Pedagog. Soc. Rev. Interuniv. 2020, 36, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, R.; Kwauk, C.T. Curriculum and Learning for Climate Action: Toward an SDG 4.7 Roadmap for Systems Change; BRILL: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, J.G. Construyendo una pedagogía de la solidaridad. La intervención educativa en situaciones de emergencia. Rev. Esp. Pedagog. 2011, 69, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadiapurwa, A.; Ali, M.; Ropo, E.; Hernawan, A.H. Trends in climate change education studies in the last ten years: A systematic literature review. Mimb. Ilmu 2024, 29, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello Benavides, L.O.; Meira Cartea, P.Á.; González Gaudiano, É.J. Representaciones sociales sobre cambio climático en dos grupos de estudiantes de educación secundaria de España y bachillerato de México. Rev. Mex. Investig. Educ. 2017, 22, 505–532. [Google Scholar]

- Calixto-Flores, R. Estudiantes del bachillerato y cambio climático. Un estudio desde las representaciones sociales. Rev. Electrón. Educ. 2022, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano-Rojas, H.; Castillo, A.; Meira-Cartea, P. El potencial educativo de la teoría de las representaciones sociales aplicada al cambio climático: Una revisión crítica de la literatura. Rev. Esp. Pedagog. 2025, 83, 27–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Vinuesa, A.; Carvalho, S.; Meira Cartea, P.Á.; Azeiteiro, U.M. Assessing climate knowledge and perceptions among adolescents. An exploratory study in Portugal. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 114, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Vinuesa, A.; Meira Cartea, P.Á.; Caride Gómez, J.A.; Bachiorri, A. El cambio climático en la educación secundaria: Conocimientos, creencias y percepciones. Enseñ. Cienc. Rev. Investig. Exp. Didáct. 2022, 40, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rivas, R.; Vilches, A.; Mayoral, O. Secondary school students’ perceptions and concerns on sustainability and climate change. Climate 2024, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Vinuesa, A. Empowering secondary education teachers for sustainable climate action. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meira-Cartea, P.Á.; Arto-Blanco, M. Representaciones del cambio climático en estudiantes universitarios en España: Aportes para la educación y la comunicación. Educ. Em Rev. 2014, spe3, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello Benavides, L.O.; Alatorre Frenk, G.; González-Gaudiano, É.J. Representaciones sociales sobre cambio climático. Un acercamiento a sus procesos de construcción. Trayectorias 2016, 18, 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Canaza-Choque, F.A. Reconocer a la bestia: Percepción de peligro climático en estudiantes de educación secundaria. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2021, 27, 417–434. [Google Scholar]

- García Vinuesa, A.; Carvalho, S.; Meira Cartea, P.Á. Cambio climático en educación secundaria: La representación social del alumnado portugués. Enseñ. Cienc. Rev. Investig. Exp. Didáct. 2024, 42, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrochano Fernández, D.; Ferrari Lagos, E.R.; Andrés Sánchez, S.; Fuertes Prieto, M.Á.; Herrero Teijón, P.; Ballegeer, A.M.; Delgado Martín, L.; Ruiz Méndez, C. Percepción del profesorado latinoamericano y español sobre el cambio climático: Aproximaciones desde un MOOC de formación docente. Rev. Educ. Ambient. Sostenibilidad 2021, 3, 2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Echanove, M.; Bloch-Atefi, A.; Hanson-Easey, S.; Oswald, T.K.; Eliott, J. Climate change cognition, affect, and behavior in youth: A scoping review. WIREs Clim. Change 2025, 16, e70000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Gjersoe, N.; O’Neill, S.; Barnett, J. Youth perceptions of climate change: A narrative synthesis. WIREs Clim. Change 2020, 11, e641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Gaudiano, E.J.; Maldonado-González, A.L. ¿Qué piensan, dicen y hacen los jóvenes universitarios sobre el cambio climático? Un estudio de representaciones sociales. Educ. Em Rev. 2014, spe3, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deisenrieder, V.; Kubisch, S.; Keller, L.; Stötter, J. Bridging the action gap by democratizing climate change education—The case of k.i.d.Z.21 in the context of Fridays for Future. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, A.L.; González Gaudiano, É.J.; Cajigal, E. Representaciones sociales y creencias epistemológicas. Conceptos convergentes en la investigación social. Cult. Represent. Soc. 2019, 13, 412–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Gaudiano, É.; Meira Cartea, P.Á. Educación, comunicación y cambio climático. Resistencias para la acción social responsable. Trayectorias 2009, 11, 6–38. [Google Scholar]

- Olausson, U. “We’re the ones to blame”: Citizens’ representations of climate change and the role of the media. Environ. Commun. 2011, 5, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, L.; Maibach, E.W.; Roser-Renouf, C.; Leiserowitz, A. Climate on cable: The nature and impact of global warming coverage on Fox News, CNN, and MSNBC. Int. J. Press. 2012, 17, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rivas, R.; Vilches, A.; Mayoral, O. Bridging the gap: How researcher–teacher collaboration is transforming climate change education in secondary schools. Sustainability 2025, 17, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olausson, U. Meat as a matter of fact(s): The role of science in everyday representations of livestock production on social media. J. Sci. Commun. 2019, 18, A01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitson, A.; Phillips, M.; Dillon, J. The Key Contributions of Subjects to Climate Change and Nature Education: A Curriculum Policy Proposal; Centre for Climate Change and Sustainability Education: London, UK, 2025; Available online: www.climateeducation.org.uk (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- European Commission; Joint Research Centre. GreenComp, the European Sustainability Competence Framework; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, G.; Calafell Subirà, G.; Rodríguez Marín, F. ¿Cómo incorporamos la complejidad en actividades de educación científica y ambiental? Enseñ. Cienc. Rev. Investig. Exp. Didáct. 2022, 40, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvé, L. Une diversité de courants en éducation relative à l’environnement. In Dictionnaire Critique Des Enjeux et Concepts Des Éducations; Barthes, A., Lange, J.M., Eds.; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2017; pp. 113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Wals, A.E.J.; Brody, M.; Dillon, J.; Stevenson, R.B. Convergence between science and environmental education. Science 2014, 344, 583–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eilam, E. Climate change education: The problem with walking away from disciplines. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2022, 58, 231–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, A.; Gray, P. A climate change and sustainability education movement: Networks, open schooling, and the “CARE-KNOW-DO” framework. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilam, E. Considering the role of behaviors in sustainability and climate change education. Front. Psychol. 2025, 15, 1394326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morote, Á.-F.; Sebastiá-Álcaraz, R.; Ferrero-Punzano, S.M.; Miguel-Revilla, D.; Moreno-Vera, J.R.; Rodríguez-Pizzinato, L.A.; Jerez García, Ó. Climate change, education, training, and perception of pre-service teachers. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Galeote, D.; Rajanen, M.; Rajanen, D.; Legaki, N.Z.; Langley, D.J.; Hamari, J. Gamification for climate change engagement: Review of corpus and future agenda. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 063004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arntzen, M.; Scheie, E.; Haug, B. Unveiling perceptions: How science teachers perceive sustainable development and their expectations of students’ learning outcomes through environmental and sustainability education. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2025, 59, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides-Lahnstein, A.I.; Ryder, J. School teachers’ conceptions of environmental education: Reinterpreting a typology through a thematic analysis. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 26, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, J.; Achiam, M.; Glackin, M. The role of out-of-school science education in addressing wicked problems: An introduction. In Addressing Wicked Problems through Science Education; Achiam, M., Dillon, J., Glackin, M., Eds.; Contributions from Science Education Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2021; Volume 8, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Stouthart, T.; Bayram, D.; Van der Veen, J. Science teachers’ views on student competences in education for sustainable development. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2025, 62, 1617–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siani, A.; Joseph, M.; Dacin, C. Susceptibility to scientific misinformation and perception of news source reliability in secondary school students. Discov. Educ. 2024, 3, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard-Jones, P.; Sands, D.; Dillon, J.; Fenton-Jones, F. The views of teachers in England on an action-oriented climate change curriculum. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 1660–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, V.; Kranz, J.; Möller, A. Climate change education challenges from two different perspectives of change agents: Perceptions of school students and pre-service teachers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, K.; Kitson, A.; Rushton, E.A.C.; Walshe, N.; Dillon, J. Teaching climate change and sustainability in England: Committed individuals and the prevalence of “self-taught” professional learning. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2025, 51, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, D.A.; Houseal, A.K.; Flarend, A.M. Secondary core science teachers’ perceptions of teaching climate change. J. Geosci. Educ. 2025, 73, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calafell, G.; Bonil, J.; Junyent, M. ¿Es posible una didáctica de la educación ambiental? ¿Existen contenidos específicos para ello? Rev. Eletrônica Mestr. Educ. Ambient. 2015, 1, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zummo, L. Climate change and the social world: Discourse analysis of students’ intuitive understandings. Sci. Educ. 2024, 33, 811–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Banet, L.; Martínez-Carmona, M.; Reis, P. Effects of an intervention on emotional and cognitive engagement in teacher education: Scientific practices concerning greenhouse gases. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1307847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, M.C.; Plate, R.R.; Oxarart, A.; Bowers, A.; Chaves, W.A. Identifying effective climate change education strategies: A systematic review of the research. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 791–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thor, D.; Karlsudd, P. Teaching and fostering an active environmental awareness: Design, validation and planning for action-oriented environmental education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrochano, D.; Ferrari, E.; López-Luengo, M.A.; Ortega-Quevedo, V. Educational gardens and climate change education: An analysis of Spanish preservice teachers’ perceptions. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagg, B.C.; Dillon, J. Plants and the Kunming-Montreal global biodiversity framework: Educational approaches to support pro-conservation behaviours. J. Biol. Educ. 2025, 59, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagg, B.C.; Dillon, J. Plant awareness is linked to plant relevance: A review of educational and ethnobiological literature (1998–2020). Plants People Planet 2022, 4, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentz, J. Learning about climate change in, with and through art. Clim. Change 2020, 162, 1595–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Valverde, G. Narrative approaches in science education: From conceptual understanding to applications in chemistry and gamification. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Valverde, G.; Fabre-Mitjans, N.; Guimerà-Ballesta, G. Narrative-driven digital gamification for motivation and presence: Preservice teachers’ experiences in a science education course. Computers 2025, 14, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, B.S.; Chrysochou, P.; Christensen, J.D.; Orquin, J.L.; Barraza, J.; Zak, P.J.; Mitkidis, P. Stories vs. facts: Triggering emotion and action-taking on climate change. Clim. Change 2019, 154, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushell, S.; Buisson, G.S.; Workman, M.; Colley, T. Strategic narratives in climate change: Towards a unifying narrative to address the action gap on climate change. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 28, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, N.; Wölfl, V. Impact of constructive narratives about climate change on learned helplessness and motivation to engage in climate action. Environ. Behav. 2025, 57, 75–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meyer, K.; Coren, E.; McCaffrey, M.; Slean, C. Transforming the stories we tell about climate change: From “issue” to “action”. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 015002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMeeking, S.; Tetini-Timoteo, M.; Hayward, B.; Prendergast, K.; Ratuva, S.; Crichton-Hill, Y.; Mayall-Nahi, M.; Wood, B.; Tolbert, S.; Harré, N.; et al. Storytelling and good relations: Indigenous youth capabilities in climate futures. Geogr. Res. 2025, 63, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherpa, P.D. Climate change education through narrative inquiry. J. Transform. Prax. 2021, 2, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano Velasco, J. Educar en el paisaje, en la cultura rural y en el conocimiento ecológico tradicional. Papeles Relac. Ecosociales Cambio Glob. 2015, 131, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Heinemeyer, C.; Reason, M.; Quatermass, N.; Wood, N.; Adekola, O. Mutual learning through participatory storytelling: Creative approaches to climate adaptation education in secondary schools. Res. Educ. 2024, 118, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Reumont, F.; Budke, A. Learning about climate change with comics and text: A comparative study. Sustain. Sci. 2023, 18, 2661–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.C. Exploring and narrating futures in undergraduate climate change education: An innovative teaching approach. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2024, 25, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Orto, E.; Tasquier, G. Narrativity and climate change education: Design of an operative approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Safe spaces or a pedagogy of discomfort? Senior high-school teachers’ meta-emotion philosophies and climate change education. J. Environ. Educ. 2021, 52, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corres, A.; Rieckmann, M.; Espasa, A.; Ruiz-Mallén, I. Educator competences in sustainability education: A systematic review of frameworks. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkman, G.; Howe, L.; Walton, G. How social norms are often a barrier to addressing climate change but can be part of the solution. Behav. Public Policy 2021, 5, 528–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, C.D.; Lam, S.; Roncker, J.; Gray, E.S.; Courtney, R.H.; Even, T.L. Justice in climate change education: A systematic review. Environ. Educ. Res. 2023, 29, 1535–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranz, J.; Schwichow, M.; Breitenmoser, P.; Niebert, K. The (un)political perspective on climate change in education—A systematic review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinol, A.; Miller, E.; Axtell, H.; Hirschfeld, I.; Leggett, S.; Si, Y.; Stephens, J.C. Climate justice in higher education: A proposed paradigm shift towards a transformative role for colleges and universities. Clim. Change 2023, 176, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Poeck, K.; Östman, L. The risk and potentiality of engaging with sustainability problems in education—A pragmatist teaching approach. J. Philos. Educ. 2020, 54, 1003–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, C.; Christie, B. Towards climate justice education: Views from activists and educators in Scotland. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 652–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, P.; Webb, R. Conceptualising uncertainty and the role of the teacher for a politics of climate change within and beyond the institution of the school. Educ. Rev. 2023, 75, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichenko, R.; Gram-Hanssen, I.; O’Brien, K. Teaching the “how” of transformation. Sustain. Sci. 2022, 17, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichenko, R.; O’Brien, K. Teaching climate change in the Anthropocene: An integrative approach. Anthropocene 2020, 30, 100241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, K.A.; Capps, D.K.; Jackson, D.F.; Capps, K.A. Six minutes to promote change: People, not facts, alter students’ perceptions on climate change. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 5790–5802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergdahl, L.; Langmann, E. Pedagogical publics: Creating sustainable educational environments in times of climate change. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2022, 21, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcinas, M.; Apostol, E.; Lingatong, S.; Sulat, M.; Jayme, M.C. Climate change engagement: Youth perspectives and pathways to climate action. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 11, 364–379. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, E.K.; Lawson, D.F.; McClain, L.R.; Plummer, J.D. Heads, hearts, and hands: A systematic review of empirical studies about eco/climate anxiety and environmental education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2024, 30, 2131–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnegan, W.; d’Abreu, C. The hope wheel: A model to enable hope-based pedagogy in climate change education. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1347392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asimakopoulou, P.; Nastos, P.; Vassilakis, E.; Hatzaki, M.; Antonarakou, A. Earth observation as a facilitator of climate change education in schools: The teachers’ perspectives. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, E.A.C.; Walshe, N.; Johnston, B.J. Towards justice-oriented climate change and sustainability education: Perspectives from school teachers in England. Curric. J. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, C.D. Activism as education in and through the youth climate justice movement. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiaszek, G.W. Ecopedagogy: Teaching critical literacies of ‘development’, ‘sustainability’, and ‘sustainable development’. Teach. High. Educ. 2020, 25, 615–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vamvalis, M. “We’re fighting for our lives”: Centering affective, collective and systemic approaches to climate justice education as a youth mental health imperative. Res. Educ. 2023, 117, 88–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Mallén, I.; Satorras, M.; March, H.; Baró, F. Community climate resilience and environmental education: Opportunities and challenges for transformative learning. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 28, 1088–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cripps, E. School for sedition? Climate justice, citizenship and education. J. Moral Educ. 2025, 54, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svastard, H. Critical climate education: Studying climate justice in time and space. Int. Stud. Sociol. 2021, 30, 214–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.