Definition

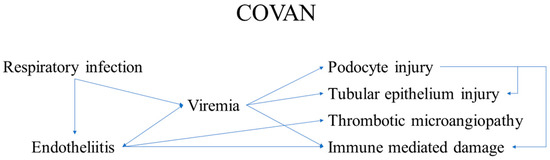

Coronaviruses are a large group of RNA viruses, the most notable representatives of which are SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. Human coronavirus infections were first documented in the 1960s, when members causing seasonal common colds were successfully replicated in human embryonal trachea and kidney cell cultures and classified based on electron microscopy. The history of coronaviruses stretched far back to that point, however, with some representatives causing disease in animals identified several decades prior and evolutionary data pointing towards the origin of this viral group more than 55 million years ago. In the short time period of research since they were discovered, coronaviruses have shown significant diversity, genetic peculiarities and varying tropism, resulting in the three identified causative agents of severe disease in humans—SARS, MERS and the most recent one, COVID-19, which has surpassed the previous two due to causing a pandemic resulting in significant healthcare, social and political consequences. Coronaviruses are likely to have caused pandemics long before, such as the so-called Asian or Russian influenza. Despite being epitheliotropic viruses and predominantly affecting the respiratory system, these entities affect multiple systems and organs, including the kidneys. In the kidneys, they actively replicate in glomerular podocytes and epithelial cells of the tubules, resulting in acute kidney injury, seen in a significant percentage of severe and fatal cases. Furthermore, the endothelial affinity of the viruses, resulting in endotheliitis, increases the likelihood of thrombotic microangiopathy, damaging the kidneys in a two-hit mechanism. As such, recently, COVAN has been a suggested nomenclature change indicating renal involvement in coronavirus infections and its long-lasting consequences.

1. Introduction

Coronaviruses are representatives of a large group of RNA viruses [1]. According to their structure, these viruses have relatively large sizes, varying between 80 and 120 μm, but some members are characterized by smaller and significantly larger sizes—from 50 to 400 μm, with a molecular mass of about 40,000 kilodaltons [1,2,3,4]. The viral single-stranded RNA is enveloped by a double lipid membrane in which transmembrane and structural proteins are integrated, including the so-called spike proteins [5]. Formed in this way, the virion has a characteristic rayed surface, visible in electron microscopy and computer-modeled reconstructions [1]. From this characteristic surface structure of the virions, they derive their name—corona viruses [1,6]. It is through these membrane-associated proteins that the virions bind to cell receptors, during which the viral endocytosis in the host cell takes place. Immediately after virion endocytosis, viral “undressing” occurs in the host cell’s cytoplasm and viral RNA is released [7]. The structure of this RNA, with a 5′ methylated cap and a 3′ polyadenylated tail, allows it to be recognized by the granulated endoplasmic reticulum as an mRNA and thus initiate direct replication of new structural proteins for the assembly of new virions, by synthesizing a replication–transcription complex [6].

The replication–transcription complex allows the viral RNA to be replicated in multiple steps, the viral structures to be transcribed and, in the presence of at least two viral RNAs, even from another virus family, in the host cell, to recombine the sources [6]. Errors in the first two described stages and the third stage of the process give the characteristics of high mutagenicity and emergence of new virus variants; a critical clarification is that such mutant and/or recombined forms are not always vital [8]. Furthermore, the hijacking of the host cell not only disrupts its metabolism and homeostasis, leading to induced apoptosis or necrosis, but can also lead to structural, functional, or mutation alterations occurring in it [9].

After the synthesis of the necessary genetic and structural material, the process of virion assembly begins, taking place predominantly in the Golgi complex, after which new virions are released from the cell by mediated exocytosis and/or cell destruction (necrosis) and can directly infect other cells [6].

Coronaviruses exhibit epithelial tropism, with individual members having specific tissue, organ and even species tropism, as well as different modes of transmission [10]. The most common infection transmission mechanism is airborne, while there are also data on fecal–oral transmission (alimentary)—coronavirus gastroenteritis in pigs [6,10,11,12]. Given the diversity of structural proteins, the cellular receptors used for endocytosis vary between different entities, with the most commonly used ones being the ACE-2 and alanine aminopeptidase receptors [6,13].

As a group of viruses, they cause diseases in a large proportion of mammals, including humans, as well as in birds, i.e., are a typical example of anthropozoonosis [6,14,15]. Characteristic of the course of these infections is the involvement of the respiratory system, with the majority of representatives involving the upper respiratory tract and causing seasonal common colds with acute, predominantly serous rhinosinusitis, conjunctivitis, otitis, pharyngitis and laryngitis [14,16]. Classically, these infections are not severe; they are transient, no specific treatment is available, and if necessary, the treatment is symptomatic—nasal decongestants, antipyretics and vitamins [16].

The earliest documented data on coronavirus infections date back to the 1920s, when they were described as causing severe bronchitis in newly hatched chicks, with extremely high mortality ranging from 40% to 90% [15,17]. Newly hatched chicks had severe respiratory symptoms, and the isolated virus was named infectious bronchitis virus in 1933 and cultivated in 1937 [18,19]. In the 1940s, viral infections in mice causing encephalitis and hepatitis were also described, and at a later stage, it was understood that the three viruses described so far belong to the same group [4,20]. Human coronaviruses were described in the 1960s as the causes of common seasonal colds, in which it was impossible to cultivate the causative agent using conventional methods used for adenoviruses and rhinoviruses [21,22]. Cultivation was achieved only a few years later using tissue cultures from human embryonal trachea [23]. Descriptions of similar viruses followed in the same decade, some of which were replicated successfully in human embryonal kidney cell cultures [23,24,25]. Utilizing electron microscopy, it was established that all the viral pathogens described so far have a characteristic shape and membrane protrusions, which is why they were united in a joint group called coronaviruses, which later included many more representatives, based on genetic analysis, with varying organ tropism and severity of symptoms [25,26].

Evolutionarily, the earliest established ancestor of modern coronaviruses is thought to have existed about 10,000 years ago, with some evidence suggesting the presence of similar viruses about 55 million years ago in bats and birds [27]. This evolutionary theory of the origin of modern coronaviruses is well supported by the fact that the natural reservoir and source of new variants are most often bats and birds [28].

The modern classification of viruses defines these viruses in the family coronaviridae, with two subfamilies, letovirinae and orthocoronavirinae, of which the characteristics and entities described so far are representatives [10,29]. The orthocoronavirinae subfamily, in turn, consists of four genera—alpha, beta, gamma and delta coronavirus [27]. Alpha- and betacoronaviruses have the greatest infectious affinity for the human population, while gamma and delta are primarily zoonotic infections [10,29,30,31]. Betacoronaviruses are of fundamental importance to the human population, whose representations include the three most severe infections with such viruses—SARS, MERS and COVID-19 [12,32,33]. It is important to note that while the betacoronavirus family is a close relative, SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 are members of the subgenus sarbecovirus, while MERS is a more distant relative—a member of the subgenus of merbecovirus.

Although the clinical picture in humans is relatively mild, except for some virus types, coronaviruses are thought to have caused epidemic outbreaks of severe disease long before they were identified, most often interpreted as influenza infections [6,14,16,34,35]. For example, the last major pandemic of the 19th century—the so-called Asian or Russian influenza, which caused a pandemic outbreak in 1889–1890, long considered to be influenza type 1—had similar symptoms to COVID-19, including neurological symptoms—loss of taste and smell, clouding of consciousness and encephalitis-like symptoms, all rarely seen in influenza [14,36,37]. Of course, serological data from the period do not exist, and proving a phylogenetic relationship is practically impossible.

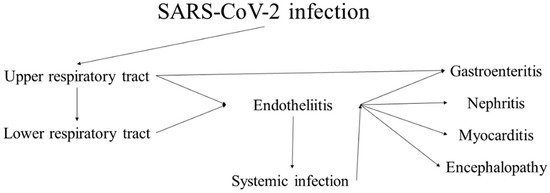

Since emerging in late 2019, the most recent representative of severe coronaviruses, SARS-CoV-2 has led to multiple consequences, from medical and social to political and philosophical [38,39,40,41]. The clinical disease the virus causes, coronavirus disease, identified in 2019 (COVID-19), while initially regarded as a respiratory infection, has shown its multisystem nature [42,43]. While most cases present with and have the most severe clinical symptoms from the respiratory system, case reports, small cohort studies and systemic research have genuinely shown the systemic nature of the virus due to its epitheliotropism and rapid dissemination (Figure 1) [40,44,45,46,47,48,49]. The characteristics of the virus and the disease it causes are broadly representative of coronaviruses, and its pathological effects are highly similar to those of the previous two significant outbreaks—SARS and MERS.

Figure 1.

Progression and sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (COVID-19).

2. Applications and Influences

Knowledge of the viral mechanism established in close relatives and the systemic effects of the infection are essential in caring for and treating ill patients, especially those in critical condition. Focus purely on the most severely affected system, i.e., the respiratory system, even with optimal care, while negating the effects of the virus on other systems may lead to rapid deterioration due to multisystem infection and the death of the patients, even in the absence of severe pathological effects to the respiratory system.

4. Conclusions and Prospects

- Coronaviruses are epitheliotropic viruses, with three variants of concern emerging over the last two decades;

- While respiratory symptoms dominate these diseases’ clinical course, many other systems and organs are also a direct viral target;

- One of these is the kidney. The renal involvement, designated as COVAN, is due to:

- ○

- direct viral replication and damage to the podocytes;

- ○

- Direct viral replication and damage to tubule epithelial cells, resulting in:

- ▪

- glomerulopathy and tubule-interstitial nephritis with acute kidney injury, latent kidney injury and chronic kidney injury, requiring dialysis in such patients;

- One of the main non-direct components of COVAN is the development of thrombotic microangiopathy, even in the context of active anticoagulant treatments, indicating a two-hit mechanism;

- Awareness of these complications, active monitoring and preventive as well as systemic treatment will inevitably decrease mortality and improve life quality in the context of post-COVID-19 syndrome.

Author Contributions

H.P. and G.S.S. conceptualized the study; H.P. and G.S.S. performed initial literature review; H.P. performed detailed review on historical data; H.P., A.B.T., M.I., D.S. and L.P. performed review on morphology and mechanisms; G.S.S., M.I., D.S. and L.P. conceptualized and produced the figures; H.P., G.S.S. and L.P. wrote the initial manuscript; A.B.T., D.S. and M.I. performed critical revisions; A.B.T. revised and approved the final version of the manuscript for submitting; H.P., G.S.S. and A.B.T. performed revisions after review. All authors have read and approve the final version of the published manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Goldsmith, C.S.; Tatti, K.M.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Rollin, P.E.; Comer, J.A.; Lee, W.W.; Rota, P.A.; Bankamp, B.; Bellini, W.J.; Zaki, S.R. Ultrastructural characterization of SARS coronavirus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masters, P.S. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 2006, 66, 193–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuman, B.W.; Kiss, G.; Kunding, A.H.; Bhella, D.; Baksh, M.F.; Connelly, S.; Droese, B.; Klaus, J.P.; Makino, S.; Sawicki, S.G. A structural analysis of M protein in coronavirus assembly and morphology. J. Struct. Biol. 2011, 174, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalchhandama, K. The chronicles of coronaviruses: The electron microscope, the doughnut, and the spike. Sci. Vis. 2020, 20, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godet, M.; L’Haridon, R.; Vautherot, J.F.; Laude, H. TGEV corona virus ORF4 encodes a membrane protein that is incorporated into virions. Virology 1992, 188, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, A.R.; Perlman, S. Coronaviruses: An overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1282, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, G.; Zmora, P.; Gierer, S.; Heurich, A.; Pöhlmann, S. Proteolytic activation of the SARS-coronavirus spike protein: Cutting enzymes at the cutting edge of antiviral research. Antivir. Res. 2013, 100, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, S.; Wong, G.; Shi, W.; Liu, J.; Lai, A.C.K.; Zhou, J.; Liu, W.; Bi, Y.; Gao, G.F. Epidemiology, Genetic Recombination, and Pathogenesis of Coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2016, 24, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, N.; Wang, W.; Liu, Z.; Liang, C.; Wang, W.; Ye, F.; Huang, B.; Zhao, L.; Wang, H.; Zhou, W. Morphogenesis and cytopathic effect of SARS-CoV-2 infection in human airway epithelial cells. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Family—Coronaviridae. Virus Taxon. 2012, 806–828. [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N. Alphacoronavirus. Springer Index Viruses 2011, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N. Betacoronavirus. Springer Index Viruses 2011, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, W.; Farzan, M.; Harrison, S.C. Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor. Science 2005, 309, 1864–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A. An uncommon cold. New Sci. 2020, 246, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estola, T. Coronaviruses, a new group of animal RNA viruses. Avian Dis. 1970, 14, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Shi, L.; Zhang, W.; He, J.; Liu, C.; Zhao, C.; Kong, S.K.; Loo, J.F.C.; Gu, D.; Hu, L. Prevalence and genetic diversity analysis of human coronaviruses among cross-border children. Virol. J. 2017, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabricant, J. The early history of infectious bronchitis. Avian Dis. 1998, 42, 648–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bushnell, L.D.; Brandly, C.A. Laryngotracheitis in Chicks. Poult Sci. 1933, 12, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N. Gammacoronavirus‡: Coronaviridae. Springer Index Viruses 2011, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, K. Coronaviruses: A Comparative Review. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol./Ergeb. Mikrobiol. Immun. 1974, 85–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, J.S.; McIntosh, K. History and recent advances in coronavirus discovery. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2005, 24, S223–S227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahase, E. Covid-19: First Coronavirus was described in The BMJ in 1965. BMJ 2020, 369, m1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrrell, D.A.J.; Bynoe, M.L. Cultivation of a Novel Type of Common-Cold Virus in Organ Cultures. Br. Med. J. 1965, 1, 1467–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamre, D.; Procknow, J.J. A new virus isolated from the human respiratory tract. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1966, 121, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, J.D.; Tyrrell, D.A. The morphology of three previously uncharacterized human respiratory viruses that grow in organ culture. J. Gen. Virol. 1967, 1, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntosh, K.; Becker, W.B.; Chanock, R.M. Growth in suckling-mouse brain of ‘IBV-like’ viruses from patients with upper respiratory tract disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1967, 58, 2268–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wertheim, J.O.; Chu, D.K.W.; Peiris, J.S.M.; Kosakovsky Pond, S.L.; Poon, L.L.M. A case for the ancient origin of coronaviruses. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 7039–7045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, P.C.Y.; Lau, S.K.P.; Lam, C.S.F.; Lau, C.C.; Tsang, A.K.; Lau, J.H.; Bai, R.; Teng, J.L.; Tsang, C.C.; Wang, M. Discovery of Seven Novel Mammalian and Avian Coronaviruses in the Genus Deltacoronavirus Supports Bat Coronaviruses as the Gene Source of Alphacoronavirus and Betacoronavirus and Avian Coronaviruses as the Gene Source of Gammacoronavirus and Deltacoronavirus. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 3995–4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Zhao, K.; Shi, Z.L.; Zhou, P. Bat Coronaviruses in China. Viruses 2019, 11, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfarouk, K.O.; AlHoufie, S.T.S.; Ahmed, S.B.M.; Shabana, M.; Ahmed, A.; Alqahtani, S.S.; Alqahtani, A.S.; Alqahtani, A.M.; Ramadan, A.M.; Ahmed, M.E. Pathogenesis and Management of COVID-19. J. Xenobiot. 2021, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: Classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockx, B.; Kuiken, T.; Herfst, S.; Bestebroer, T.; Lamers, M.M.; Oude Munnink, B.B.; de Meulder, D.; van Amerongen, G.; van den Brand, J.; Okba, N.M.A. Comparative pathogenesis of COVID-19, MERS, and SARS in a nonhuman primate model. Science 2020, 368, 1012–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarner, J. Three Emerging Coronaviruses in Two DecadesThe Story of SARS, MERS, and Now COVID-19. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2020, 153, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forgie, S.; Marrie, T.J. Healthcare-associated atypical pneumonia. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 30, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corman, V.M.; Muth, D.; Niemeyer, D.; Drosten, C. Hosts and Sources of Endemic Human Coronaviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 2018, 100, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brüssow, H.; Brüssow, L. Clinical evidence that the pandemic from 1889 to 1891 commonly called the Russian flu might have been an earlier coronavirus pandemic. Microb. Biotechnol. 2021, 14, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijgen, L.; Keyaerts, E.; Moës, E.; Thoelen, I.; Wollants, E.; Lemey, P.; Vandamme, A.M.; Van Ranst, M. Complete Genomic Sequence of Human Coronavirus OC43: Molecular Clock Analysis Suggests a Relatively Recent Zoonotic Coronavirus Transmission Event. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, N. The coronavirus is here to stay - here’s what that means. Nature 2021, 590, 382–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, K.G.; Rambaut, A.; Lipkin, W.I.; Holmes, E.C.; Garry, R.F. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 450–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzieciatkowski, T.; Szarpak, L.; Filipiak, K.J.; Jaguszewski, M.; Ladny, J.R.; Smereka, J. COVID-19 challenge for modern medicine. Cardiol. J. 2020, 27, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.W.; Cheong, K.H. Superposition of COVID-19 waves, anticipating a sustained wave, and lessons for the future. BioEssays 2020, 42, 2000178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Guo, H.; Zhou, P.; Shi, Z.L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, G.T.; Baymakova, M.; Vaseva, V.; Kundurzhiev, T.; Mutafchiyski, V. Clinical Characteristics of Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19 in Sofia, Bulgaria. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2020, 20, 910–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiga, M.; Wang, D.W.; Han, Y.; Lewis, D.B.; Wu, J.C. COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease: From basic mechanisms to clinical perspectives. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, R.C.; Cicinelli, M.V.; Gilbert, S.S.; Honavar, S.G.; Murthy, G.V.S. COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons learned and future directions. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 68, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buja, L.M.; Wolf, D.; Zhao, B.; Akkanti, B.; McDonald, M.; Lelenwa, L.; Reilly, N.; Ottaviani, G.; Elghetany, M.T.; Trujillo, D.O.; et al. The emerging spectrum of cardiopulmonary pathology of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Report of 3 autopsies from Houston, Texas, and review of autopsy findings from other United States cities. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2020, 48, 107233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siripanthong, B.; Nazarian, S.; Muser, D.; Deo, R.; Santangeli, P.; Khanji, M.Y.; Cooper, L.T., Jr.; Chahal, C.A.A. Recognizing COVID-19–related myocarditis: The possible pathophysiology and proposed guideline for diagnosis and management. Heart Rhythm 2020, 17, 1463–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legrand, M.; Bell, S.; Forni, L.; Joannidis, M.; Koyner, J.L.; Liu, K.; Cantaluppi, V. Pathophysiology of COVID-19-associated acute kidney injury. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2021, 17, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Mannan, O.; Eyre, M.; Löbel, U.; Bamford, A.; Eltze, C.; Hameed, B.; Hemingway, C.; Hacohen, Y. Neurologic and Radiographic Findings Associated With COVID-19 Infection in Children. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 1440–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, B.T.; Bryan, A. Emerging respiratory infections: The infectious disease pathology of SARS, MERS, pandemic influenza, and Legionella. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 2019, 36, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peeri, N.C.; Shrestha, N.; Siddikur Rahman, M.; Zaki, R.; Tan, Z.; Bibi, S.; Baghbanzadeh, M.; Aghamohammadi, N.; Zhang, W.; Haque, U. The SARS, MERS and novel coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemics, the newest and biggest global health threats: What lessons have we learned? Int. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 49, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan-Yeung, M.; Xu, R.H. SARS: Epidemiology. Respirology 2003, 8, S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consensus Document on the Epidemiology of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. (SARS). Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/70863 (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Stephenson, J. SARS in China. JAMA 2004, 291, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, T.J.; Chong, P.Y.; Chui, P.; Galvin, J.R.; Lourens, R.M.; Reid, A.H.; Selbs, E.; McEvoy, C.P.; Hayden, C.D.; Fukuoka, J.; et al. Lung pathology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): A study of 8 autopsy cases from Singapore. Hum. Pathol. 2003, 34, 743–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Z.W.; Zhang, L.J.; Zhang, S.J.; Meng, X.; Li, J.Q.; Song, C.Z.; Sun, L.; Zhou, Y.S.; Dwyer, D.E. A clinicopathological study of three cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Pathology 2003, 35, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Wang, H.; Shen, H.; Li, Z.; Geng, J.; Han, H.; Cai, J.; Li, X.; Kang, W.; Weng, D.; et al. The clinical pathology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): A report from China. J. Pathol. 2003, 200, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; He, L.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Z.; Geng, J.; Han, H.; Cai, J.; Li, X.; Kang, W.; Weng, D.; et al. Organ distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in SARS patients: Implications for pathogenesis and virus transmission pathways. J. Pathol. 2004, 203, 622–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.L.; Ding, Y.Q.; Hou, J.L.; He, L.; Huang, Z.X.; Wang, H.J.; Cai, J.J.; Zhang, J.H.; Zhang, W.L.; Geng, J.; et al. [Detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-associated coronavirus RNA in autopsy tissues with in situ hybridization]. Di Yi Jun Yi Da Xue Xue Bao 2003, 23, 1125–1127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chu, K.H.; Tsang, W.K.; Tang, C.S.; Lam, M.F.; Lai, F.M.; To, K.F.; Fung, K.S.; Tang, H.L.; Yan, W.W.; Chan, H.W.; et al. Acute renal impairment in coronavirus-associated severe acute respiratory syndrome. Kidney Int. 2005, 67, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacciarini, F.; Ghezzi, S.; Canducci, F.; Sims, A.; Sampaolo, M.; Ferioli, E.; Clementi, M.; Poli, G.; Conaldi, P.G.; Baric, R.; et al. Persistent Replication of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus in Human Tubular Kidney Cells Selects for Adaptive Mutations in the Membrane Protein. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 5137–5144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satija, N.; Lal, S.K. The Molecular Biology of SARS Coronavirus. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007, 1102, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoyanov, G.S.; Yanulova, N.; Stoev, L.; Zgurova, N.; Mihaylova, V.; Dzhenkov, D.L.; Stoeva, M.; Stefanova, N.; Kalchev, K.; Petkova, L. Temporal Patterns of COVID-19-Associated Pulmonary Pathology: An Autopsy Study. Cureus 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, B.T.; Maioli, H.; Johnston, R.; Chaudhry, I.; Fink, S.L.; Xu, H.; Najafian, B.; Deutsch, G.; Lacy, J.M.; Williams, T.; et al. Histopathology and ultrastructural findings of fatal COVID-19 infections in Washington State: A case series. Lancet 2020, 396, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariri, L.P.; North, C.M.; Shih, A.R.; Israel, R.A.; Maley, J.H.; Villalba, J.A.; Vinarsky, V.; Rubin, J.; Okin, D.A.; Sclafani, A.; et al. Lung Histopathology in Coronavirus Disease 2019 as Compared With Severe Acute Respiratory Sydrome and H1N1 Influenza: A Systematic Review. Chest 2021, 159, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanov, G.S.; Petkova, L.; Dzhenkov, D.L.; Sapundzhiev, N.R.; Todorov, I. Gross and Histopathology of COVID-19 With First Histology Report of Olfactory Bulb Changes. Cureus 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, A.M.; van Boheemen, S.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Fouchier, R.A.M. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1814–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assiri, A.; Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Al-Rabeeah, A.A.; Al-Rabiah, F.A.; Al-Hajjar, S.; Al-Barrak, A.; Flemban, H.; Al-Nassir, W.N.; Balkhy, H.H.; Al-Hakeem, R.F.; et al. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: A descriptive study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 752–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemida, M.G.; Perera, R.A.; Wang, P.; Alhammadi, M.A.; Siu, L.Y.; Li, M.; Poon, L.L.; Saif, L.; Alnaeem, A.; Peiris, M. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) coronavirus seroprevalence in domestic livestock in Saudi Arabia, 2010 to 2013. Euro Surveill 2013, 18, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, E.I.; El-Kafrawy, S.A.; Farraj, S.A.; Hassan, A.M.; Al-Saeed, M.S.; Hashem, A.M.; Madani, T.A. Evidence for camel-to-human transmission of MERS coronavirus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 2499–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briese, T.; Mishra, N.; Jain, K.; Zalmout, I.S.; Jabado, O.J.; Karesh, W.B.; Daszak, P.; Mohammed, O.B.; Alagaili, A.N.; Lipkin, W.I. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus quasispecies that include homologues of human isolates revealed through whole-genome analysis and virus cultured from dromedary camels in Saudi Arabia. mBio 2014, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assiri, A.; McGeer, A.; Perl, T.M.; Price, C.S.; Al Rabeeah, A.A.; Cummings, D.A.; Alabdullatif, Z.N.; Assad, M.; Almulhim, A.; Makhdoom, H.; et al. Hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Who Mers-Cov Research Group. State of Knowledge and Data Gaps of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in Humans. PLoS Curr. 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauchemez, S.; Fraser, C.; Van Kerkhove, M.D.; Donnelly, C.A.; Riley, S.; Rambaut, A.; Enouf, V.; van der Werf, S.; Ferguson, N.M. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: Quantification of the extent of the epidemic, surveillance biases, and transmissibility. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.K.W.; Poon, L.L.M.; Gomaa, M.M.; Shehata, M.M.; Perera, R.A.; Abu Zeid, D.; El Rifay, A.S.; Siu, L.Y.; Guan, Y.; Webby, R.J.; et al. MERS coronaviruses in dromedary camels, Egypt. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 1049–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saey, T.H. Story one: Scientists race to understand deadly new virus: SARS-like infection causes severe illness, but may not spread quickly among people. Sci. News 2013, 183, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO EMRO. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Available online: http://www.emro.who.int/health-topics/mers-cov/mers-outbreaks.html (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Alsaad, K.O.; Hajeer, A.H.; Al Balwi, M.; Al Moaiqel, M.; Al Oudah, N.; Al Ajlan, A.; AlJohani, S.; Alsolamy, S.; Gmati, G.E.; Balkhy, H.; et al. Histopathology of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronovirus (MERS-CoV) infection—Clinicopathological and ultrastructural study. Histopathology 2018, 72, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, J.M.; Brooks, E.G.; Akers, J.; Armstrong, D.; Decker, L.; Gonzalez, A.; Humphrey, W.; Mayer, R.; Miller, M.; Perez, C.; et al. COVID-19: Postmortem Diagnostic and Biosafety Considerations. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2020, 41, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-Y.; Cheong, H.; Kim, H.-S. Medicine TWG for SAG for C-19 from TKS for L: Proposal of the Autopsy Guideline for Infectious Diseases: Preparation for the Post-COVID-19 Era (abridged translation). J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020, 35, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, D.L.; Al Hosani, F.; Keating, M.K.; Gerber, S.I.; Jones, T.L.; Metcalfe, M.G.; Tong, S.; Tao, Y.; Alami, N.N.; Haynes, L.M.; et al. Clinicopathologic, Immunohistochemical, and Ultrastructural Findings of a Fatal Case of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Infection in the United Arab Emirates, April 2014. Am. J. Pathol. 2016, 186, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabi, Y.M.; Arifi, A.A.; Balkhy, H.H.; Najm, H.; Aldawood, A.S.; Ghabashi, A.; Hawa, H.; Alothman, A.; Khaldi, A.; Al Raiy, B. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014, 160, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckerle, I.; Müller, M.A.; Kallies, S.; Gotthardt, D.N.; Drosten, C. In-vitro renal epithelial cell infection reveals a viral kidney tropism as a potential mechanism for acute renal failure during Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) Coronavirus infection. Virol. J. 2013, 10, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, M.L.; Yao, Y.; Jia, L.; Chan, J.F.; Chan, K.H.; Cheung, K.F.; Chen, H.; Poon, V.K.; Tsang, A.K.; To, K.K.; et al. MERS coronavirus induces apoptosis in kidney and lung by upregulating Smad7 and FGF2. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, R.H.; Yang, S.H.; Moon, K.C.; Joh, J.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Shin, H.S.; Kim, D.K.; Kim, Y.S. A Case Report of a Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Survivor with Kidney Biopsy Results. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2016, 31, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, S.A.; Beaubien-Souligny, W.; Shah, P.S.; Harel, S.; Blum, D.; Kishibe, T.; Meraz-Munoz, A.; Wald, R.; Harel, Z. The Prevalence of Acute Kidney Injury in Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Kidney Med. 2021, 3, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.H.; Zaidan, M.; Jhaveri, K.D.; Izzedine, H. Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis and COVID-19. Clin. Kidney J. 2021, 14, 2151–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero, J.; Merino-López, M.; Olmedo, R.; Garrido-Roldan, R.; Moguel, B.; Rojas, G.; Chavez-Morales, A.; Alvarez-Maldonado, P.; Duarte-Molina, P.; Castaño-Guerra, R.; et al. Association between Postmortem Kidney Biopsy Findings and Acute Kidney Injury from Patients with SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2021, 16, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, B.; Wang, C.C.; Wang, R.; Journet, J.; Lariotte, A.C.; Aubignat, D.; Rebibou, J.M.; De La Vega, M.F.; Legendre, M.; Belliot, G.; et al. Human kidney is a target for novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akilesh, S.; Nast, C.C.; Yamashita, M.; Henriksen, K.; Charu, V.; Troxell, M.L.; Kambham, N.; Bracamonte, E.; Houghton, D.; Ahmed, N.I.; et al. Multicenter Clinicopathologic Correlation of Kidney Biopsies Performed in COVID-19 Patients Presenting With Acute Kidney Injury or Proteinuria. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2021, 77, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caramaschi, S.; Kapp, M.E.; Miller, S.E.; Eisenberg, R.; Johnson, J.; Epperly, G.; Maiorana, A.; Silvestri, G.; Giannico, G.A. Histopathological findings and clinicopathologic correlation in COVID-19: A systematic review. Mod. Pathol. 2021, 34, 1614–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.K.; Bhargava, R.; Shaukat, A.A.; Albert, E.; Leggat, J. Spectrum of podocytopathies in new-onset nephrotic syndrome following COVID-19 disease: A report of 2 cases. BMC Nephrol. 2020, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, S.; Zhou, X.J.; Hiser, W. Collapsing glomerulopathy in a patient of Indian descent in the setting of COVID-19. Ren. Fail. 2020, 42, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasupulati, A.K. Is Podocyte Injury During COVID-19 Infection Contributes To Proteinuria and A Threat To Renal Failure ? J. Clin. Nephrol. Res. 2020, 7, 7–1096. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Y.; Nasr, S.H.; Larsen, C.P.; Kemper, A.; Ormsby, A.H.; Williamson, S.R. COVID-19–Associated Collapsing Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis: A Report of 2 Cases. Kidney Med. 2020, 2, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magoon, S.; Bichu, P.; Malhotra, V.; Alhashimi, F.; Hu, Y.; Khanna, S.; Berhanu, K. COVID-19–Related Glomerulopathy: A Report of 2 Cases of Collapsing Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Med. 2020, 2, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Uppal, N.N.; Wanchoo, R.; Shah, H.H.; Yang, Y.; Parikh, R.; Khanin, Y.; Madireddy, V.; Larsen, C.P.; Jhaveri, K.D.; et al. COVID-19–Associated Kidney Injury: A Case Series of Kidney Biopsy Findings. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 31, 1948–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basic-Jukic, N.; Coric, M.; Bulimbasic, S.; Dika, Z.; Juric, I.; Furic-Cunko, V.; Katalinic, L.; Kos, J.; Fistrek, M.; Kastelan, Z.; et al. Histopathologic findings on indication renal allograft biopsies after recovery from acute COVID-19. Clin. Transplant. 2021, 35, e14486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velez, J.C.Q.; Caza, T.; Larsen, C.P. COVAN is the new HIVAN: The re-emergence of collapsing glomerulopathy with COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2020, 16, 565–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouquegneau, A.; Erpicum, P.; Grosch, S.; Habran, L.; Hougrand, O.; Huart, J.; Krzesinski, J.M.; Misset, B.; Hayette, M.P.; Delvenne, P.; et al. COVID-19–associated Nephropathy Includes Tubular Necrosis and Capillary Congestion, with Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 in the Nephron. Kidney360 2021, 2, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijers, B.; Hilbrands, L.B. The clinical characteristics of coronavirus-associated nephropathy. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2020, 35, 1279–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, A.A.; Tawhari, I.; Safar-Boueri, L.; Seif, N.; Alahmadi, A.; Gargiulo, R.; Aggarwal, V.; Usman, I.; Kisselev, S.; Gharavi, A.G.; et al. COVID-19-associated glomerular disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2021, 32, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemudryi, A.; Nemudraia, A.; Wiegand, T.; Surya, K.; Buyukyoruk, M.; Cicha, C.; Vanderwood, K.K.; Wilkinson, R.; Wiedenheft, B. Temporal Detection and Phylogenetic Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 in Municipal Wastewater. Cell Rep. Med. 2020, 1, 100098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitamura, K.; Sadamasu, K.; Muramatsu, M.; Yoshida, H. Efficient detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the solid fraction of wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 763, 144587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).