Abstract

Background: Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their inhibitors, tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs), regulate the extracellular matrix. This study examined messenger RNA transcripts of TIMP2 before and after kidney transplantation. Methods: Transcripts were measured in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from 105 kidney transplant recipients, including AB0-incompatible, AB0-compatible, and deceased donor transplantation patients. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction was utilized. Results: Kidney transplant recipients (72 male; 33 female) were a median of 55 (44–63) years old. The median (interquartile range) of pretransplant TIMP2 transcripts was 0.68 (0.50–0.87) in kidney transplant recipients. In total, 9 out of 72 patients (13%) showed delayed graft function, i.e., need for dialysis within 1 week after transplantation. Preoperative TIMP2 transcripts were significantly lower in kidney transplant recipients who experienced delayed graft function compared to patients with immediate graft function (0.40 (0.32–0.62) vs. 0.68 (0.56–0.87); p = 0.01). There was no association between TIMP2 transcripts and age or gender. TIMP2 median transcripts were 0.73 (0.58–0.88) on the first postoperative day. TIMP2 transcripts were similar on the first postoperative day in patients with delayed graft function and immediate graft function. Conclusions: Preoperative TIMP2 transcripts were lower in patients with delayed allograft function. Future investigations are needed to establish the role of TIMP2 transcripts in transplant pathophysiology.

1. Introduction

Chronic kidney disease remains a serious issue, with a prevalence varying between 3% and 17% in Europe [1]. When chronic kidney disease progresses to end-stage kidney disease, renal replacement therapy is initiated. A kidney allograft transplant is the most effective kind of renal replacement therapy [2,3]. However, the number of kidney transplants required exceeds the available supply [4]. The life expectancy of a living donor kidney transplant recipient without return to dialysis is approximately 20 years, with large variation according to donor age, recipient comorbidities, rejection episodes, infections, and lifestyle habits [2]. To aid in prolonging kidney graft survival, several biomarkers are being researched to guide clinical decision-making [5].

Among these biomarkers are matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases 2 (TIMP2). MMP9 is a zinc-dependent endopeptidase enzyme that remodels the extracellular matrix and is involved in chronic kidney disease [6], rheumatologic diseases [7], and breast cancer [8]. TIMP2 is an inhibitor of MMP9 which is involved in cellular processes such as apoptosis and proliferation [9]. Urinary and serum TIMP2 have been shown to be positively correlated with delayed or reduced kidney graft function [10,11,12].

There is not much knowledge about TIMP2 messenger RNA transcripts from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in kidney transplant recipients. PBMCs interact with the allograft. We hypothesize that this interaction between the allograft and PBMCs may affect transcripts in PBMCs and consequently affect the outcome after a kidney transplant. To monitor these interactions, we measured the TIMP2 transcript. Changes in TIMP2 may thus mirror allograft outcome after kidney transplant. The aim of this study, using data from a study in kidney transplant recipients, was to report the transcript levels of TIMP2 relative to β-actin in PBMCs in kidney transplant recipients before and one day after transplantation using Reverse Transcriptase Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR). In addition, we tested the associations between transcript levels of TIMP2 and age, type of transplant, and delayed allograft function.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Ethics, and Patient Population

This study used data from the study “Molecular Monitoring after Kidney Transplantation” (MoMoTx) at Odense University Hospital, Denmark (ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT01515605). This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declarations of Helsinki and Istanbul. The local ethics committee (Den Videnskabsetiske Komité for Region Syddanmark) approved the MoMoTx study (Projekt-ID 20100098). It is confirmed that the consent form for participation was distributed to all participants and signed.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: above 18 years, incident kidney transplant recipient, and written informed consent given prior to enrolment. A total of 105 patients were included in this paper; 78 had preoperative TIMP2 transcript levels available and 103 had postoperative transcript levels available following the same testing schedule.

The characteristics of the MoMoTx study have been reported previously [13,14,15]. Clinical and laboratory data were retrieved from electronic medical records. Delayed graft function was defined as a need for dialysis within 7 days after transplantation [16]. The entirety of the paper is written without the use of AI or AI-powered tools.

2.2. Isolation of Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells

The following method of extracting PBMCs, the extraction and purification of total RNA, the synthesis of complementary DNA (cDNA), and RT-qPCR has previously been described by our group [13,15]. In brief, blood samples were collected preoperatively and on the first postoperative day. Isolation of PBMCs was performed using heparinized whole blood. The heparinized blood was first centrifuged at 1620× g for 4 min, plasma was discarded, and the remaining blood was then diluted with 1.5 mL of Hanks’ Balanced Salt solution. Cells were then extracted and layered on top of 1.8 mL of Histopaque (Histopaque, Sigma Aldrich, Søborg, Denmark; density: 1.077 g/mL) and were centrifuged for 15 min at 952× g. PBMCs were then harvested and centrifuged at 8000× g for 3 min with phosphate-buffered saline. Finally, the PBMCs were suspended in 400 μL of TRI reagent (TRIzol, Sigma Aldrich, Søborg, Denmark) and frozen at −80 °C.

2.3. Extraction and Purification of Total RNA

Extraction of RNA was performed using a RNeasy mini-kit including an RNase-free DNase set (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), in accordance with the protocol of the manufacturer. The purity and concentration of total RNA were assessed using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (Implen nanophotometer, Implen GmbH, Munich, Germany). Absorbance was measured at 260 nm and 280 nm, and the ratio (A260/A280) was calculated. Samples with a ratio between 1.8 and 2.1 were processed further, as this indicates highly purified RNA. Afterwards, the RNA was stored at −80 °C.

2.4. Synthesis of Complementary DNA

The extracted RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). A measure of 300 ng of total RNA was mixed with genomic DNA wipeout buffer and incubated at 42 °C for 4 min. Afterwards, the RNA was mixed with Quantiscript Reverse Transcriptase, Quantiscript RT buffer, and RT primer mix. It was subsequently incubated at 37 °C for 60 min, and the reaction was then inactivated at 95 °C for 5 min. The synthesized cDNA was stored at −20 °C.

2.5. Primers and Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

RT-qPCR was used to quantify the transcription levels of TIMP2 and β-actin. A primer for TIMP2 [17] and a primer for β-actin [15], as reported in the literature, were ordered from Sigma Aldrich, Søborg, Denmark.

TIMP2 Forward: AAGCGGTCAGTGAGAAGGAAG

TIMP2 Reverse: GGGGCCGTGTAGATAAACTCTAT

β-actin Forward: GGACTTCGAGCAAGAGATGG

β-actin Reverse: AGCACTGTGTTGGCGTACAG

RT-qPCR measurements were carried out with the LightCycler 96 Instrument (Roche, Copenhagen, Denmark). The cycle settings were a single preincubation cycle at 95 °C for 10 min, then 55 cycles of 3-step amplification, consisting of the denaturation of cDNA at 95 °C for 10 s, annealing of primers at 63 °C for 10 s, and extension of primers at 72 °C for 10 s. After the 55 cycles, a single melting cycle was included, comprising 95 °C for 10 s, 65 °C for 60 s, and 97 °C for 1 s. FastStart Essential DNA Green Master Mix (Roche, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used for the PCR reaction. Each reaction consisted of 2 μL of cDNA, 2 μL of forward primer, 2 μL of reverse primer, 4 μL of nuclease-free water, and 10 μL of FastStart Essential DNA Green Master Mix. Melting peaks and amplification graphs were assessed using LightCycler 96 Software 1.1 (Roche, Copenhagen, Denmark). All reactions were run in duplicate, and in-house cDNA control and nuclease-free water control were run alongside the reactions. TIMP2 was calculated according to β-actin values. We also determined TIMP2 transcripts in healthy subjects as another group for calculations using the delta-delta quantification cycle method [2−ΔΔCq method]. In that group, the average ΔCq was 5.67 (median, 5.76; IQR, 5.36 to 6.10). All transcript levels were reported as 2−ΔΔCq unless specified otherwise.

2.6. Gel Electrophoresis of PCR Products

PCR product band size was controlled by gel electrophoresis. A 2% agarose gel was made using 30 mL of TAE buffer, 0.6 g of agarose powder, and 3 μL of GelRed 10,000× stock reagent at a 1:10,000 dilution. We used a Gene Ruler 50 bp DNA ladder (Thermo Scientific, Roskilde, Denmark) for size determination of PCR products.

Measures of 4 μL of sample buffer, 20 μL of PCR product, and 4 μL of Gel Loading Dye, Blue (6×) (New England BioLabs, Copenhagen, Denmark) were loaded in wells in the finished agarose gel. Electrophoresis was then performed for 1 h at 100 Volts.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

For descriptive statistics, numerical data were reported with median and interquartile range (IQR), and categorical data were reported with frequency and percentages. A Bland–Altman plot was also utilized. For analytical statistics, non-parametric tests (Mann–Whitney test, Kruskal–Wallis test, Spearman correlation) were used as appropriate. Fisher’s exact test was used for contingency tables.

All statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 10.4.2 for Windows, GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA). All statistical tests were two-sided, and p-values lower than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. TIMP2 Transcript Levels in Kidney Transplant Recipients Before and One Day After Transplantation

TIMP2 transcript levels were measured in 105 incident kidney transplant recipients; 78 patients had preoperative TIMP2 transcripts, whereas 103 patients had TIMP2 transcripts on their first postoperative day. Patient characteristics for all 105 patients, divided into groups based on the type of graft donor, are shown in Table 1. The characteristics of the patients with available pretransplant transcripts and information about postoperative allograft function are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of 105 kidney transplant patients, divided into groups based on the type of graft donor. Table 1 gives information on 105 recipients for whom either pre- or postoperative TIMP2 values were available.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of 72 kidney transplant patients, divided into groups based on graft function. Table 2 gives information on all 72 recipients where graft function status (immediate graft or delayed graft function) and preoperative TIMP2 values were available.

The median TIMP2 transcript level was 0.68 (IQR, 0.50 to 0.87) in the 78 preoperative samples. Preoperative TIMP2 transcript levels were not associated with recipient age (Spearman r = 0.21, p = 0.07). There was no significant correlation of preoperative TIMP2 transcripts and height, weight, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, or mean blood pressure (each p greater than 0.05). There was no association between preoperative TIMP2 transcript levels and a drop in plasma creatinine level on the first postoperative day (p = 0.25 by Mann–Whitney test).

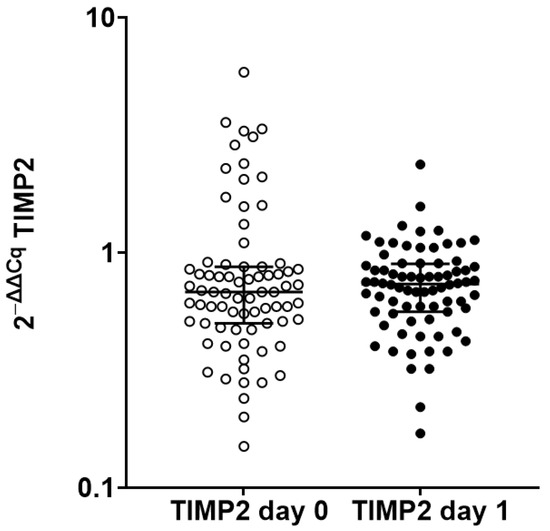

TIMP2 transcript levels on the first postoperative day had a median of 0.73 (IQR, 0.58 to 0.88) in the 103 samples (p = 0.39 by Mann–Whitney test; Figure 1). Transcripts were also similar in patients receiving thymoglobulin-containing induction therapy and patients receiving all other induction therapies.

Figure 1.

Scatterplot of preoperative (day 0) and first postoperative day (day 1) TIMP2 transcript levels in kidney transplant recipients. Preoperative TIMP2 transcript levels were available from 78 recipients, whereas postoperative TIMP2 transcript levels on the first postoperative day were available from 103 recipients. TIMP2 transcript level was similar (p = 0.39 by Mann–Whitney test).

We also measured TIMP2 transcript levels in eight healthy kidney donors before donation for use in the 2−ΔΔCq method; in that group, the average ΔCq was 5.67 (median, 5.76; IQR, 5.36 to 6.10).

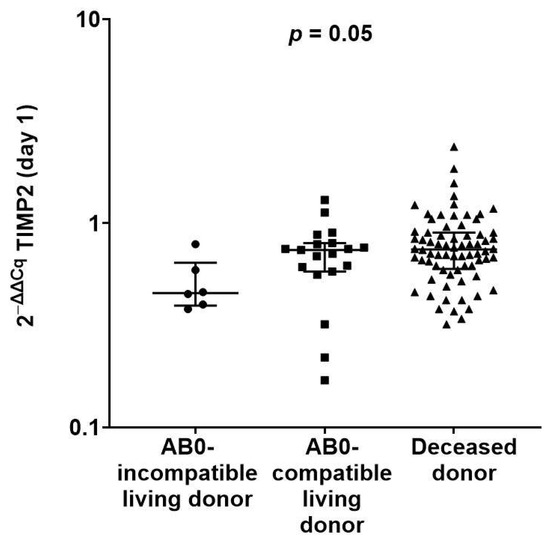

3.2. Postoperative TIMP2 Transcripts According to Donor Type

Among 97 patients with available data, 6 recipients had AB0-incompatible living donors, 19 recipients had AB0-compatible living donors, and 72 recipients had deceased donors. The recipients with AB0-incompatible living donors had median TIMP2 transcripts of 0.46 (IQR, 0.40 to 0.64), recipients with AB0-compatible living donors had median TIMP2 transcripts of 0.74 (IQR, 0.58 to 0.80), and recipients with deceased donors had median TIMP2 transcripts of 0.75 (IQR, 0.60 to 0.90) (p = 0.05 by Kruskal–Wallis test; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Scatterplot of first postoperative day TIMP2 transcripts according to type of kidney donor. In total, 6 recipients had AB0-incompatible living donors, 19 recipients had AB0-compatible living donors, and 72 recipients had deceased donors. There was a significant difference in transcripts (p = 0.05 by Kruskal–Wallis test).

3.3. Allograft Function According to Preoperative and First Postoperative Day TIMP2 Transcript Levels

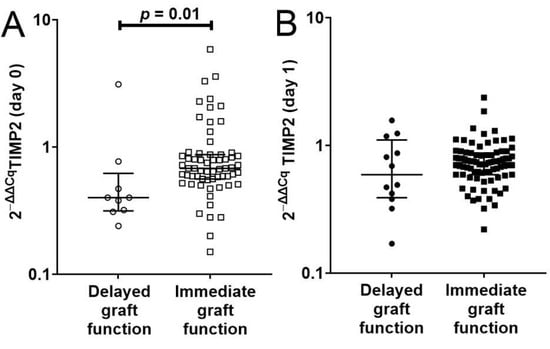

Among 72 recipients with preoperative TIMP2 transcripts, 9 recipients had delayed graft function (DGF), defined as needing dialysis within 7 days after transplantation, whereas 63 recipients had immediate graft function (IGF). Recipients with delayed graft function had significantly lower median preoperative TIMP2 transcripts than recipients with immediate graft function (0.40 (IQR, 0.32 to 0.62) vs. 0.68 (IQR, 0.56 to 0.87)) (p = 0.01 by Mann–Whitney test; Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

(A) Scatterplot showing the significantly lower preoperative TIMP2 transcripts of 9 kidney transplant recipients with delayed graft function compared to 63 kidney transplant recipients with immediate graft function (p = 0.01 by Mann–Whitney test). (B) Scatterplot of first postoperative day TIMP2 transcripts in 12 kidney transplant recipients with delayed graft function and 83 kidney transplant recipients with immediate graft function (p = 0.46 by Mann–Whitney test). (B) Information on 95 recipients where graft function status (immediate graft or delayed graft function) and postoperative TIMP2 values are available.

Among 95 recipients with first postoperative day TIMP2 transcripts, 12 recipients had delayed graft function, and the remaining 83 recipients had immediate graft function. On the first postoperative day, recipients with delayed graft function and immediate graft function had similar TIMP2 transcript levels (median of 0.59 (IQR, 0.39 to 1.10) vs. median of 0.73 (IQR, 0.59 to 0.87)) (p = 0.46 by Mann–Whitney test; Figure 3B).

Analysis of data using only individuals with both pre- and post-operative TIMP2 values confirmed that there was a significant difference between these groups preoperatively (IGF: 0.68 (0.55 to 0.88; n = 61) vs. DGF 0.40 (0.31 to 0.62; n = 9), p = 0.0099 by Mann–Whitney test). On the other hand, there still was no significant effect between the groups postoperatively (IGF: 0.74 (0.59 to 0.88; n = 61) vs. DGF 0.49 (0.35 to 1.21; n = 9), p = 0.55, non-significant by Mann–Whitney test).

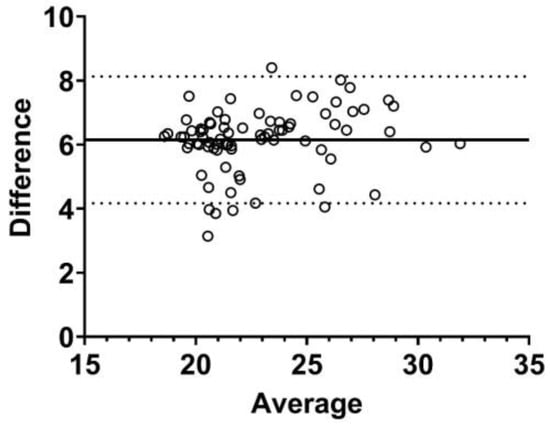

3.4. Preoperative TIMP2 and β-Actin Transcript Levels

A Bland–Altman plot analyzing the agreement between preoperative TIMP2 and β-actin Cq-values is presented in Figure 4. There were 78 patients with preoperative TIMP2 and β-actin Cq-values. The median TIMP2 Cq-value was 24.61 (IQR, 23.53 to 27.85), and the β-actin median Cq-value was 19.09 (IQR, 17.63 to 21.37). The bias was 6.1, with a standard deviation of 1.0, and the 95% limits of agreement were from 4.2 to 8.1.

Figure 4.

Bland–Altman plot of preoperative TIMP2 quantification cycle values compared to preoperative β-actin quantification cycle values in 78 kidney transplant recipients. The bias was 6.1 (as shown by the solid line), the standard deviation was 1.0, and the 95% limits of agreement were from 4.2 to 8.1 (as shown by the dotted lines).

This may indicate that TIMP2 transcription is closely related to genes essential for cellular existence due to its specific function as a regulator of the extracellular matrix.

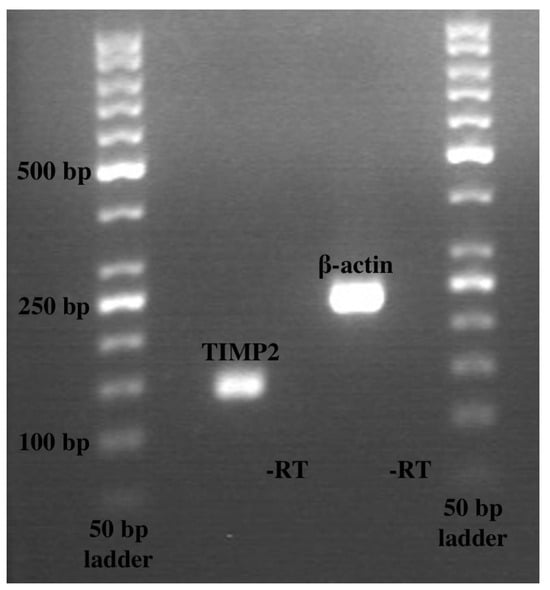

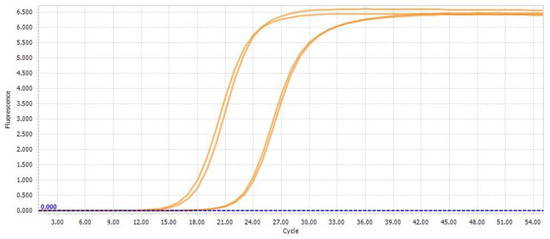

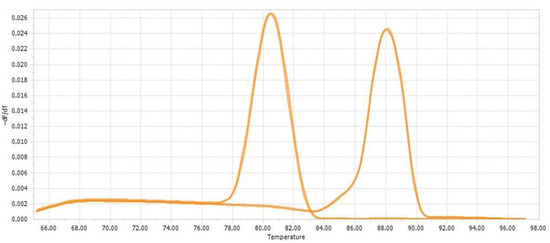

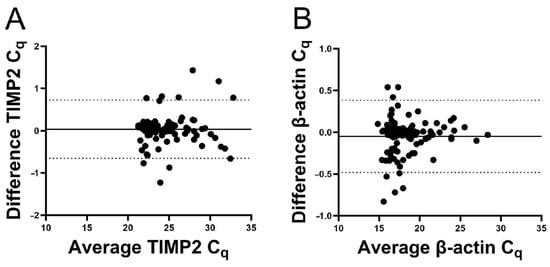

The gel electrophoresis of PCR products and Cq-curves for β-actin and TIMP2, melting peaks for β-actin and TIMP2, as well as Bland–Altman plots, are shown respectively in Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8.

Figure 5.

Gel electrophoresis of polymerase chain reaction products. Lane 1 contains TIMP2 at 136 base pairs; lane 3 contains β-actin at 234 base pairs. Lanes 2 and 4 had controls with no reverse transcriptase. A total of 50 base pair ladders were used.

Figure 6.

Quantification cycle curves from LightCycler 96 Software 1.1; one sample with double determination is shown for β-actin and TIMP2, respectively.

Figure 7.

Melting peak curves from LightCycler 96 Software 1.1; one sample with double determination is shown for TIMP2 and β-actin, respectively.

Figure 8.

Bland–Altman plots of quantification. Average of duplicate Cq-values was plotted against the difference. The bias was 0.035 for TIMP2 and −0.049 for β-actin. The solid lines represent the bias, and the dotted lines represent the 95% limits of agreement. (A) For TIMP2, the bias was 0.035, the standard deviation was 0.35, and the 95% limits of agreement were −0.65 to 0.72. (B) For β-actin, the bias was −0.049, the standard deviation was 0.22, and the 95% limits of agreement were −0.48 to 0.38.

4. Discussion

The present study in kidney transplant recipients showed that preoperative TIMP2 transcripts were lower in patients with delayed allograft function. Future investigations are needed to establish the role of TIMP2 transcripts in transplant pathophysiology. TIMP2 concentrations can be influenced by several factors. These include the function of the patient’s own kidneys and of the allograft, medication before and after the transplantation, inflammatory changes due to the surgery, and the effects of immobilization, dietary changes, and gastrointestinal changes. It may be speculated that inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein or interleukins may show an association between inflammation and outcome after kidney transplant [18].

Recipients with delayed graft function show an increased risk for death and kidney graft failure [19], and therefore, detection of delayed graft function is important, as it may allow for improved management of the condition. TIMP2 is an important regulator of the extracellular matrix and has been associated with fibrosis, acute kidney disease, and chronic kidney disease [20,21]. However, it is unclear whether TIMP2 may also be a marker for delayed allograft function in kidney transplant recipients. Yang et al. used [TIMP2] × [IGFBP7] protein levels and showed that high urinary [TIMP2] × [IGFBP7] was correlated with creatinine clearance [11]. In contrast, Kwiatkowska et al. showed no correlation of TIMP2 and creatinine clearance on the first postoperative day [12]. It may be speculated that well known difficulties during urine collections may explain these discrepant findings.

Furthermore, the use of TIMP2 for the determination of acute kidney injury has been tested [22]. Esmeijer et al. found TIMP2 to be a predictor of renal replacement therapy and 30-day mortality in elective cardiac surgery, although it has not been introduced into clinical practice yet [23]. Dekker et al. found that urinary TIMP2 did not correlate with disease severity in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease [24]. Other markers for delayed graft function have been published, such as kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM-1) [25], endotrophin [14], and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) [5]. The previously mentioned studies, however, were all performed on protein levels, and the impact on clinical practice has been limited. Few studies have been performed on reduced or delayed graft function and mRNA transcript levels. Wohlfahrtova et al. investigated netrin-1 transcripts in kidney biopsies and found that low netrin-1 transcripts were associated with delayed graft function [26]. Hruba et al. found that certain transcripts isolated from peripheral vein blood could predict early graft loss at three years [27].

Among the strengths of the present study is a large cohort (N = 105), which includes both males and females (31% female). Furthermore, measurements of transcripts are reproducible and consistent, as evidenced by the double determination of Cq-values.

There were also limitations to the study. The study was limited to one site, and there were technical issues with sample handling during the COVID-19 epidemic, leading to a reduced number of available RNA samples. A limitation of the present study is the imbalance in sample size and the low numbers in one group. This may weaken the reliability of the conclusions despite their apparent statistical significance. In addition, subgroup analyses could not be performed due to statistical power. Furthermore, another limitation of this study is the high prevalence of glomerulonephritis as a cause for end-stage renal disease in the study population.

As expected, time on dialysis was higher in patients with delayed graft function, confirming that our cohort represents the common dialysis population. It should be noted that since we report transcript levels in PBMCs, other tissues—such as kidney tissue—may exhibit different transcript levels. Transcripts were determined at two points, i.e., before and after transplant, for practical reasons, but may not show a complete picture. Lastly, the induction therapies consisted of various substances which might have various effects on transcripts. The differences in TIMP2 transcripts on the first postoperative day may reflect differences in recipients’ and donors’ characteristics and therapies. We may speculate that a multitude of underlying causes and their complex interaction with inflammatory markers, immunosuppression, and immune cell activation are involved. Several recipient and donor characteristics may be mirrored in TIMP2, at least on the protein level. It is known that TIMP2 is associated with cell cycle arrest, cell proliferation, and cellular repair mechanisms, which all contribute to outcomes after a kidney transplant. It is unknown whether TIMP2 may be affected by haemodialysis. As indicated by Friedrich et al., there were studies showing controversial results with respect to the acute effects of haemodialysis treatment on cytokine protein levels, and several transcripts may be affected similarly to other markers, for example, C-reactive protein [28]. We restricted our analysis to immediate versus delayed allograft function due to the limited sample size. We cannot exclude the possibility that TIMP2 can also be affected by several additional factors, e.g., inflammation, dialysis vintage, dialysis conditions, body composition, current diagnosis of diabetes, and prior organ transplant, which all may be included in the analysis of future larger populations. Long-term outcomes after a kidney transplant cannot be predicted from the present investigation. This is in line with findings in the literature that TIMP2 may be a biomarker of acute kidney injury.

5. Conclusions

TIMP2 is present in peripheral blood cells as well as in kidney tubules and it is involved in the regulation of the cell cycle. Hence, changes in cellular TIMP2 transcript levels may play a role in transplant outcomes. Particularly, patients with delayed allograft function after transplant show lower pretransplant transcripts of TIMP2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.M.M., S.N. and M.T.; methodology, T.M.M., S.N. and M.T.; validation, T.M.M., S.N. and M.T.; formal analysis, T.M.M. and M.T., investigation, T.M.M., S.N. and M.T.; data curation, T.M.M., S.N. and M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, T.M.M., S.N. and M.T.; writing—review and editing, T.M.M., S.N. and M.T.; visualization, T.M.M. and M.T.; supervision, S.N. and M.T.; project administration, S.N. and M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local ethics committee (Den Videnskabsetiske Komité for Region Syddanmark) (Project ID 20100098; approval date: 30 November 2011).

Informed Consent Statement

Participants gave written informed consent prior to enrolment in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data are included in the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, Gen AI was NOT used. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| KTR | Kidney transplant recipient |

| TIMP2 | Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

References

- Brück, K.; Stel, V.S.; Gambaro, G.; Hallan, S.; Völzke, H.; Ärnlöv, J.; Kastarinen, M.; Guessous, I.; Vinhas, J.; Stengel, B.; et al. CKD Prevalence Varies across the European General Population. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 2135–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggio, E.D.; Augustine, J.J.; Arrigain, S.; Brennan, D.C.; Schold, J.D. Long-term kidney transplant graft survival-Making progress when most needed. Am. J. Transplant. 2021, 21, 2824–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, K.J.; Bhattarai, M.; Parajuli, S. Delayed graft function: Current status and future directions. Curr. Opin. Organ. Transplant. 2023, 28, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio-Lucar, A.G.; Patel, A.; Mehta, S.; Yadav, A.; Doshi, M.; Urbanski, M.A.; Concepcion, B.P.; Singh, N.; Sanders, M.L.; Basu, A.; et al. Expanding the access to kidney transplantation: Strategies for kidney transplant programs. Clin. Transplant. 2024, 38, e15315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaglia, M.; Merlotti, G.; Guglielmetti, G.; Castellano, G.; Cantaluppi, V. Recent Advances on Biomarkers of Early and Late Kidney Graft Dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaRussa, A.; Serra, R.; Faga, T.; Crugliano, G.; Bonelli, A.; Coppolino, G.; Bolignano, D.; Battaglia, Y.; Ielapi, N.; Costa, D.; et al. Kidney fibrosis and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). Front. Biosci.-Landmark 2024, 29, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, R.; Maeda, T.; Zhang, H.; Berry, G.J.; Zeisbrich, M.; Brockett, R.; Greenstein, A.E.; Tian, L.; Goronzy, J.J.; Weyand, C.M. MMP (Matrix Metalloprotease)-9-producing monocytes enable T cells to invade the vessel wall and cause vasculitis. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 700–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Li, H. Prognostic values of tumoral MMP2 and MMP9 overexpression in breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrish, A.R. Matrix metalloproteinases in kidney disease: Role in pathogenesis and potential as a therapeutic target. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2017, 148, 31–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.J.; Xu, D.S.; Liu, S.D.; Yan, J.K.; Liu, X.L.; Zhang, X.F.; Pan, W.G.; Tian, C. An analysis of the relationship between donor and recipient biomarkers and kidney graft function, dysfunction, and rejection. Transpl. Immunol. 2023, 81, 101934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lim, S.Y.; Kim, M.G.; Jung, C.W.; Cho, W.Y.; Jo, S.K. Urinary tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase and insulin-like growth factor-7 as early biomarkers of delayed graft function after kidney transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 2017, 49, 2050–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowska, E.; Domanski, L.; Bober, J.; Safranow, K.; Romanowski, M.; Pawlik, A.; Kwiatkowski, S.; Ciechanowski, K. Affiliations expand urinary metalloproteinases-9 and -2 and their inhibitors TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 are markers of early and long-term graft function after renal transplantation. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2016, 41, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipic, D.; Rasmussen, M.; Saleh, Q.W.; Tepel, M. Induction therapies determine the distribution of perforin and granzyme B transcripts in kidney transplant recipients. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepel, M.; Alkaff, F.F.; DKremer Bakker, S.J.L.; Thaunat, O.; Nagarajah, S.; Saleh, Q.; Berger, S.P.; van den Born, J.; Krogstrup, N.V.; Nielsen, M.B.; et al. Pretransplant endotrophin predicts delayed graft function after kidney transplantation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagarajah, S.; Rasmussen, M.; Hoegh, S.V.; Tepel, M. Prospective study of long noncoding RNA, MGAT3-AS1, and viremia of BK polyomavirus and cytomegalovirus in living donor renal transplant recipients. Kidney Int. Rep. 2020, 5, 2218–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, W.; Gao, F. Delayed graft function as a predictor of chronic allograft dysfunction: A 10-year follow-up study. BMC Nephrol. 2025, 26, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Tong, Y.; Wang, W.; Hou, Y.; Dou, H.; Liu, Z. Characterization and significance of monocytes in acute stanford type B aortic dissection. J. Immunol. Res. 2020, 2020, 9670360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heldal, T.F.; Åsberg, A.; Ueland, T.; Reisæter, A.V.; Pischke, S.E.; Mollnes, T.E.; Aukrust, P.; Hartmann, A.; Heldal, K.; Jenssen, T. Inflammation in the early phase after kidney transplantation is associated with increased long-term all-cause mortality. Am. J. Transplant. 2022, 22, 2016–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapiawala, S.N.; Tinckam, K.J.; Cardella, C.J.; Schiff, J.; Cattran, D.C.; Cole, E.H.; Kim, S.J. Delayed graft function and the risk for death with a functioning graft. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 21, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanz, M.; Kimmel, M.; Alscher, M.D.; Amann, K.; Daniel, C. TIMP-2 and IGFBP7 in human kidney biopsies in renal disease. Clin. Kidney J. 2023, 16, 1434–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musiał, K.; Zwolińska, D. Novel indicators of fibrosis-related complications in children with chronic kidney disease. Clin. Chim. Acta 2014, 430, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, A.; Faubel, S.; Askenazi, D.J.; Cerda, J.; Fissell, W.H.; Heung, M.; Humphreys, B.D.; Koyner, J.L.; Liu, K.D.; Mour, G.; et al. Clinical use of the urine biomarker [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] for acute kidney injury risk assessment. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2016, 68, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmeijer, K.; Schoe, A.; Ruhaak, L.R.; Hoogeveen, E.K.; Soonawala, D.; Romijn, F.P.H.T.M.; Shirzada, M.R.; van Dissel, J.T.; Cobbaert, C.M.; de Fijter, J.W. The predictive value of TIMP-2 and IGFBP7 for kidney failure and 30-day mortality after elective cardiac surgery. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekker, S.E.I.; Ruhaak, L.R.; Romijn, F.P.H.T.M.; Meijer, E.; Cobbaert, C.M.; de Fijter, J.F.; Soonawala, D.; DIPAK Consortium. Urinary tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 do not correlate with disease severity in ADPKD patients. Kidney Int. Rep. 2019, 4, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, B.; Prasad, N.; Agrawal, V.; Jaiswal, A.; Agrawal, V.; Rai, M.; Sharma, R.; Gupta, A.; Bhadauria, D.; Kaul, A. Urinary kidney injury molecule-1 can predict delayed graft function in living donor renal allograft recipients. Nephrology 2015, 20, 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlfahrtova, M.; Brabcova, I.; Zelezny, F.; Balaz, P.; Janousek, L.; Honsova, E.; Lodererova, A.; Wohlfahrt, P.; Viklicky, O. Tubular atrophy and low netrin-1 gene expression are associated with delayed kidney allograft function. Transplantation 2014, 97, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hruba, P.; Klema, J.; Le, A.V.; Girmanova, E.; Mrazova, P.; Massart, A.; Maixnerova, D.; Voska, L.; Piredda, G.B.; Biancone, L.; et al. Affiliations expand novel transcriptomic signatures associated with premature kidney allograft failure. EBioMedicine 2023, 96, 104782. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich, B.; Alexander, D.; Janessa, A.; Häring, H.U.; Lang, F.; Risler, T. Acute effect of hemodialysis on cytokine transcription profiles: Evidence for C-reactive protein dependency of mediator induction. Kidney Int. 2006, 70, 2124–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.