Abstract

This study aims to evaluate the reliability and minimal detectable change (MDC) of the 2 min marching test (2MMT) for cardiovascular response, as well as to compare its outcomes with those of the 6 min walk test (6MWT), in youth recovering from post-COVID-19 condition. Forty-four youth with post-COVID-19 condition underwent two assessment sessions, separated by five days, utilizing both the 6MWT and 2MMT to measure cardiorespiratory response parameters. Test–retest reliability was found to be excellent for the 6MWT (ICC = 0.83; MDC95 = 8.06%) and good for the 2MMT (ICC = 0.78; MDC95 = 15.61%) between initial and follow-up measurements. The 2MMT demonstrates good reliability and validity for assessing cardiovascular response in youth with post-COVID-19 condition. The reported MDC values provide clinically meaningful thresholds that enable clinicians to distinguish true changes in performance from measurement error. These findings support the use of the 2MMT as a practical tool for clinical assessment, providing preliminary guidance for interpreting changes in performance. However, longitudinal monitoring of patient progress was not directly assessed in this study.

1. Introduction

Individuals with preexisting cardiorespiratory diseases are at a higher risk of morbidity and mortality following infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection [1]. This population also showed a greater incidence of cardiorespiratory complications, including arrhythmia, myocardial injury, and acute coronary syndrome [2,3,4], as well as symptoms such as cough, fatigue, fever, and shortness of breath [3]. These findings highlight the importance of monitoring cardiovascular function in populations affected by COVID-19.

For undergraduate students, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic led to the abrupt cancelation of in-person classes and a transition to remote, virtual learning in an effort to reduce transmission of the highly contagious virus. Most universities resumed in-person instruction, with safety protocols in place, during the 2021–2022 academic year. A previous report identified college campuses as significant sites of super-spreader events [5]. Although young individuals generally experience milder acute symptoms than adults, more than half of those infected with COVID-19 have been reported to present at least one risk factor for coronary heart disease [6]. Importantly, youth represent a distinct population with unique functional demands, including academic activities, social participation, and physical activity requirements, which may be disproportionately affected by post-COVID-19 functional impairments. A previous study found that individuals recovering from COVID-19 experienced a reduction in cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF), which was associated with decreased quality of life and increased risk of cardiovascular diseases [7]. However, evidence regarding the impact of COVID-19 on CRF in young individuals remains limited. This knowledge gap is particularly relevant given that post-COVID-19 functional limitations in youth may be under-recognized and differ in presentation and recovery trajectory from those observed in adults or older populations. Therefore, age-appropriate and practical assessment tools are needed to evaluate functional cardiovascular endurance in this population.

The six-minute walk test (6MWT) is the most frequently used measure for assessing physical capacity in a range of respiratory, metabolic, cardiovascular, and neurological disorders [8,9,10,11]. While the 6MWT can be conducted in resource-limited settings, it requires specific technical conditions, such as a 30 m corridor, which is often not available in hospitals and rehabilitation centers [8]. A previous study developed a new cardiovascular endurance assessment using the 2 min marching test (2MMT) to evaluate cardiovascular endurance in healthy individuals. The results showed that the 2MMT was comparable to the 6MWT in estimating VO2max and demonstrated no significant difference in cardiovascular responses between the two tests [12]. The researchers concluded that the 2MMT is a practical tool for assessing functional capacity and cardiovascular endurance in older adults, individuals with pulmonary conditions, and those at risk for heart disease or hypertension. Additionally, it offers a time-efficient option for follow-up assessment during rehabilitation, home isolation, or routine clinical evaluation [12]. The 2MMT was designed to measure the number of steps completed within 2 min. Participants were instructed to march in place, raising their knees to a target an height of 30 cm, and to perform as many steps as possible while maintaining this knee height throughout the test [12]. However, limited data are available regarding cardiorespiratory responses to the 2MMT in youth with post-COVID-19 conditions. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the test–retest reliability and determine the minimal detectable change (MDC) for the cardiorespiratory response parameters of the 2MMT. Additionally, it seeks to compare these outcomes with those obtained from the 6MWT in youth with post-COVID-19 conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This observational, descriptive, cross-sectional study aimed to assess test–retest reliability and calculate MDC scores for the cardiorespiratory response parameters of the 2MMT, as well as compare these outcomes with those of the 6MWT in youth with post-COVID-19 conditions.

2.2. Participants

A total of 44 participants of age 18–23 years with a confirmed history of SAR-CoV-2 infection, verified via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or antigen test kit (ATK), were recruited. All participants had recovered from COVID-19 at the time of enrollment, with at least 12 weeks since their last infection. The participants were recruited from the University of Phayao and were not experiencing acute COVID-19 symptoms during the study. Participants reported common post-COVID-19 symptoms such as fatigue, exercise intolerance, and shortness of breath. Eligibility as post-COVID-19 individuals was based on a confirmed prior infection combined with the presence of at least one lingering symptom consistent with post-COVID-19 condition. The sample size was calculated based on the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) approach [13], assuming a minimum acceptable ICC of 0.60 and an expected ICC of 0.80, with 90% power and a 5% significance level. A minimum of 40 participants was required, with an additional 10% added to account for potential attrition, resulting in a final sample size of 44. Participants were excluded if they had a history of acute myocardial infarction, asthma, unstable angina or musculoskeletal or neurological disorders that could affect test performance. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants following a full explanation of the study procedures. Ethical approval was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Phayao, Thailand (HREC-UP-HSST 1.2/155/68).

2.3. Procedure

All assessments were conducted by a physiotherapist over two days separate, with a 5-day interval between them. One the first day, participants underwent baseline assessments, including demographic data such as age, weight, height, body mass index (BMI), duration of COVID-19 infection, and presenting symptoms. Cardiorespiratory response parameters were then measured during both the 6MWT and the 2MMT. The order of test administration was randomized using sealed envelopes. A 30 min rest period was provided between the two tests to minimize fatigue effects. On the second day, participants repeated both the 6MWT and 2MMT following the same procedures as on the first day.

Prior to commencing the 6MWT, participants underwent an initial assessment of prior cardiorespiratory parameters, including heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), pulse oxygen saturation (O2sat), rate of perceived exertion (RPE), and leg fatigue. Participants were instructed to wear comfortable clothing and appropriate footwear. The test was performed along a 30 m corridor, with participants instructed to walk as far as possible within 6 min without running. The total distance covered was recorded as the primary outcome measure [14]. Additionally, cardiorespiratory response parameters were recorded during the first minute of the test to monitor physiological responses during exertion.

Prior to commencing the 2MMT, participants underwent an initial assessment of cardiorespiratory parameters, including HR, SBP, DBP, O2sat, RPE, and leg fatigue. Participants were instructed to march in place, raising their knees to a target height of 30 cm. They were asked to perform as many steps as possible, ensuring each step reached the designated knee height, within a 2 min period. A brief familiarization session was provided, allowing participants to perform a few practice steps to ensure proper technique and confirm their ability to complete the task. Participants were permitted to march at a self-selected pace and were allowed to slow down or pause if needed before resuming until the 2 min duration was completed. The assessor counted the number of completed steps, defined by the right foot contacting the ground, and provided time reminders and verbal encouragement throughout the test to promote maximal effort [12]. Additionally, cardiorespiratory response parameters were recorded during the first minute of the test to monitor physiological responses during exertion.

Cardiorespiratory parameters were recorded during the first minute of both the 6MWT and the 2MMT. Measurements during the initial minute were selected to standardize data collection across participants and to capture the early cardiovascular response under submaximal, steady-state conditions. This approach is consistent with previously described protocols for functional field-based endurance tests, including the 6MWT [14] and the original development of the 2MMT [12], and minimizes the influence of pacing strategies, premature fatigue, or symptom-limited termination that may occur at peak effort or during post-test recovery.

Unlike treadmill or cycle ergometer testing, the 2MMT does not require electrical devices, calibration, or technical expertise, making it feasible for use in resource-limited clinical settings, community health centers, and during repeated assessments in youth recovering from post-COVID-19 condition. Furthermore, the self-paced nature of the 2MMT allows participants to regulate exercise intensity and pause if symptoms such as fatigue or dyspnea occur, enhancing safety and tolerability in this population.

The order of test administration was randomized using sealed envelopes. All assessments were conducted by the same trained physiotherapists following standardized testing protocols. Assessors were not blinded between testing sessions; however, consistent procedures and standardized verbal instructions were applied to minimize potential measurement bias.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of the data distribution. Continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations (SD). Test–retest reliability for both the 6MWT and 2MMT was evaluated using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), with reliability interpreted as follows: excellent (ICC ≥ 0.90), good (0.90 > ICC ≥ 0.70), fair (0.70 > ICC ≥ 0.40), and poor (ICC < 0.40). The Standard Error of Measurement (SEM), indicating the precision of the reliability estimated, was calculated using the formula: SEM = sd × √(1 − r). The minimal detectable change at the 95% confidence level (MDC95) was computed as MDC95 = SEM × 1.96 × √2. Agreement between repeated measurements was further assessed using Bland–Altman plots. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistics, version 26, with a significance level set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

Table 1 presents the demographic and clinical characteristics of the youth experiencing post-COVID-19 conditions. Females constituted the majority of participants in this study. Key vital signs, including SBP, DBP, HR, and O2sat, were within normal ranges. On average, participants reported 1.93 previous COVID-19 infections, with a mean duration of 33.86 months since their last infection. The average number of vaccination doses received was 2.41.

Table 1.

Characteristics of youth with post-COVID-19 conditions.

Table 2 summarizes the cardiorespiratory responses of youth with post-COVID-19 conditions. No significant differences were observed between trials for cardiorespiratory responses during either the 6MWT or the 2MMT. In the 6MWT, mean HR was 125.73 bpm (Trial 1) and 129.86 bpm (Trial 2, p = 0.071). SBP/DBP were recorded at 144.27/85.18 mmHg and 141.11/83.98 mmHg for Trial 1 and Trial 2, respectively (p > 0.05). O2sat was 98.32% in Trial 1 and 97.95% in Trial 2 (p = 0.125), while RPE and leg fatigue were 4.19 and 4.43 in Trial 1, and 5.23 and 5.43 in Trial 2 (p > 0.05). Similarly, the 2MMT showed no significant differences between Trial 1 and Trial 2 for HR, SBP, DBP, O2sat, RPE, and leg fatigue (p > 0.05). Although no statistically significant differences were observed between trials, a small increase in performance was noted in the second trial, particularly for the 2MMT. This trend may reflect familiarization or learning effect as participants became more accustomed to the test procedures.

Table 2.

Cardiorespiratory responses in youth with post-COVID-19 conditions.

As detailed in Table 3, both the 6MWT and the 2MMT demonstrated good test–retest reliability in youth with post-COVID-19 conditions. For the 6MWT, mean distances were 596.91 m (Trial 1) and 610.25 m (Trial 2), yielding an ICC of 0.83, a SEM of 17.56 m, and an MDC95 of 8.06 m. The 2MMT showed mean repetitions of 108.52 (Trial 1) and 114.25 (Trial 2), with an ICC of 0.78, an SEM of 8.16 repetitions, and an MDC95 of 15.61 repetitions.

Table 3.

The test–retest reliability of the 6MWT and 2MMT in youth with post-COVID-19 conditions.

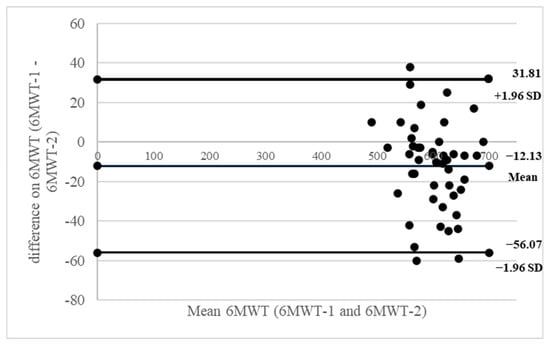

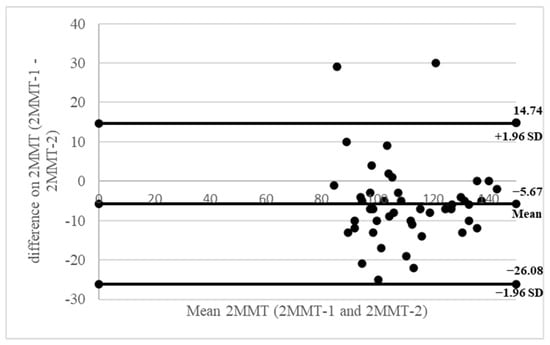

Figure 1 and Figure 2 present Bland–Altman plots illustrating the test–retest reliability of the 6MWT and 2MMT, respectively. In these plots, the x-axis represents the mean score from both trials, and the y-axis shows the difference between the two trials.

Figure 1.

Bland–Altman plots of inter-rater reliability of the 6MWT. The x-axis presents the mean score, and the y-axis presents the difference between trials.

Figure 2.

Bland–Altman plots of inter-rater reliability of the 2MMT. The x-axis presents the mean score, and the y-axis presents the difference between trials.

4. Discussion

This study is novel as it represents the first assessment of test–retest reliability, including MDC95 scores, for cardiorespiratory response parameters of the 2MMT, specifically in youth with post-COVID-19 conditions. It also provides a direct comparison of these outcomes with the 6MWT. Both the 6MWT (ICC (3,1) = 0.83) and the 2MMT (ICC (3,1) = 0.78) demonstrated good test–retest reliability. Furthermore, no significant differences were observed in cardiorespiratory response parameters HR, SBP, DBP, O2sat, RPE, and leg fatigue between the two trials for either test. This consistency in results across trials suggests that youth with post-COVID-19 conditions may have improved their familiarity with the test protocols.

The clinical utility of the 2MMT for evaluating cardiovascular endurance in healthy individuals has been previously reported. This research demonstrated the 2MMT’s equivalence to the 6MWT in estimating maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max), with consistent cardiovascular responses between both tests. Therefore, the 2MMT represents a viable alternative for assessing functional ability or cardiovascular endurance in patient groups such as older adults, those with respiratory conditions, and individuals at risk for cardiovascular disease or hypertension. Moreover, its time-efficient nature makes it particularly suitable for serial monitoring during rehabilitation, home-based care, or standard clinical screening [12]. Therefore, our results suggest the 2MMT can serve as a valid and acceptable method for evaluating cardiovascular endurance in youth recovering from COVID-19.

Although treadmill and cycle ergometer tests can be performed in relatively small areas, these modalities require costly equipment, routine maintenance, calibration, and trained personnel. In addition, treadmill walking may alter natural gait patterns, while cycle ergometer performance can be influenced by lower-limb muscular fatigue and cycling skill rather than true cardiorespiratory limitation. In contrast, the 2MMT is equipment-free, low-cost, and closely reflects functional movements commonly performed in daily life, thereby offering greater ecological validity for assessing cardiovascular endurance. These advantages are particularly relevant for youth with post-COVID-19 condition, who often present with fluctuating fatigue, dyspnea, and autonomic symptoms. Maximal or semi-maximal treadmill or cycling tests may exacerbate symptoms or reduce test tolerability in this population. The 2MMT, as a brief submaximal and self-paced test, allows immediate cessation if symptoms arise and can be safely administered with minimal supervision. Moreover, its short duration and simple setup support efficient clinical workflow and facilitate serial monitoring of functional recovery when space, time, or resources are constrained.

The 6MWT serves as a gold standard for evaluating cardiovascular endurance in various populations, particularly those with heart or lung diseases [15,16,17,18]. Its clinical significance is further underscored by its ability to predict morbidity and mortality rates in these patient groups [19,20]. Conversely, a notable drawback of the 6MWT is its spatial demand: the requirement for a corridor longer than 30 m often limits its practical application in space-constrained clinical or rehabilitation settings [14]. The 2 min step test (2MST) is a known tool for assessing cardiovascular endurance in various populations, including older adults, and those undergoing inpatient and outpatient cardiopulmonary rehabilitation, as well as healthy individuals [21,22]. However, the 2MST has limitations, particularly its requirement for high leg elevation and potential for measurement discrepancies, which can introduce errors in assessment results [12]. To address these issues, a previous study developed the 2MMT, demonstrating its practicality, simplicity, and equivalence to the 6MWT in estimating VO2max in healthy individuals [12]. Despite this, the test–retest reliability and Minimal Detectable Change (MDC) for cardiorespiratory response parameters of the 2MMT have not yet been investigated in youth with post-COVID-19 conditions. Our study aims to fill this critical gap, being the first to explore these aspects in this specific population. Consequently, we confirm the 2MMT as a valid and reliable tool for evaluating cardiovascular endurance in individuals recovering from COVID-19.

To enhance clinical interpretation, our study evaluated the MDC, which quantifies the smallest true change in a measurement, beyond the margin of assessment error [23]. In youth recovering from COVID-19, we observed excellent MDC reliability for the 6MWT (8.06% MDC95) and acceptable reliability for the 2MMT (15.61% MDC95) [24]. These MDC values provide preliminary reference thresholds that may assist clinicians and researchers in distinguishing potential true changes in functional performance from measurement variability during rehabilitation or follow-up assessments. As this is the first study to report MDC values for the 2MMT, the findings offer initial benchmarks in the absence of previous data for direct comparison; however, these values should be interpreted cautiously and within the broader clinical and recovery context of youth post-COVID-19.

Limitations of This Study

The limitations of this study include the relatively small sample size and the cross-sectional design, which may restrict generalizability. The long and variable interval since the last COVID-19 infection should also be considered as a factor that could influence cardiorespiratory outcomes. In addition, the absence of CPET or spirometry, as well as the lack of comparison with other clinical parameters such as pulmonary function and symptom tracking over time, represents another limitation. This highlights the need for future research to examine the concurrent validity of the 2MMT against gold-standard cardiopulmonary assessments and other relevant clinical measures. Such studies would provide additional evidence to further support the reproducibility, clinical applicability, and suitability of the 2MMT for evaluating post-COVID-19 condition.

5. Conclusions

The 2MMT is a reliable and valid tool for assessing cardiovascular endurance in youth post-COVID-19 and is suitable for evaluating meaningful patient improvements. Its minimal space requirements, lack of specialized equipment, and favorable safety profile make it a practical alternative to the 6MWT, treadmill, and cycle ergometer, particularly in settings with limited resources. Additionally, the identified MDC values may help guide rehabilitation decisions and monitor meaningful changes over time, reinforcing its clinical applicability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.A.; Methodology, P.A., W.T., N.S. and S.W.; Formal Analysis, P.A.; Investigation, P.A. and S.W.; Data Curation, P.A.; Writing, P.A.; Original Draft Preparation, P.A.; Writing—Review and Editing, P.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by University of Phayao and Thailand Science Research and Innovation Fund (Fundamental Fund 2026, Grant No. 2264).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Human Ethical Committee at the University of Phayao, Phayao, Thailand (HREC-UP-HSST 1.2/155/68, on 6 August 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the volunteers who participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chung, M.K.; Zidar, D.A.; Bristow, M.R.; Cameron, S.J.; Chan, T.; Harding, C.V., 3rd; Kwon, D.H.; Singh, T.; Tilton, J.C.; Tsai, E.J.; et al. COVID-19 and Cardiovascular Disease: From Bench to Bedside. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 1214–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranard, L.S.; Fried, J.A.; Abdalla, M.; Anstey, D.E.; Givens, R.C.; Kumaraiah, D.; Kodali, S.K.; Takeda, K.; Karmpaliotis, D.; Rabbani, L.E.; et al. Approach to Acute Cardiovascular Complications in COVID-19 Infection. Circ. Heart Fail. 2020, 13, e007220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adilović, M. COVID-19 related complications. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2025, 213, 259–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochav, S.M.; Coromilas, E.; Nalbandian, A.; Ranard, L.S.; Gupta, A.; Chung, M.K.; Gopinathannair, R.; Biviano, A.B.; Garan, H.; Wan, E.Y. Cardiac Arrhythmias in COVID-19 Infection. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2020, 13, e008719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Weintz, C.; Pace, J.; Indana, D.; Linka, K.; Kuhl, E. Are college campuses superspreaders? A data-driven modeling study. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 24, 1136–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts, J.; Fernandez, M.L.; Lofgren, I.E. Coronary heart disease risk factors in college students. Adv. Nutr. 2014, 5, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwendinger, F.; Knaier, R.; Radtke, T.; Schmidt-Trucksäss, A. Low Cardiorespiratory Fitness Post-COVID-19: A Narrative Review. Sports Med. 2023, 53, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, A.E.; Spruit, M.A.; Troosters, T.; Puhan, M.A.; Pepin, V.; Saey, D.; McCormack, M.C.; Carlin, B.W.; Sciurba, F.C.; Pitta, F.; et al. An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society technical standard: Field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 44, 1428–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavero-Redondo, I.; Saz-Lara, A.; Bizzozero-Peroni, B.; Núñez-Martínez, L.; Díaz-Goñi, V.; Calero-Paniagua, I.; Matínez-García, I.; Pascual-Morena, C. Accuracy of the 6-Minute Walk Test for Assessing Functional Capacity in Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction and Other Chronic Cardiac Pathologies: Results of the ExIC-FEp Trial and a Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. Open 2024, 10, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubo, H.; Nozoe, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Kamo, A.; Noguchi, M.; Kanai, M.; Mase, K.; Shimada, S. Safety and Feasibility of the 6-Minute Walk Test in Patients with Acute Stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2018, 27, 1632–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C. Validity of the 6-minute walk test and step test for evaluation of cardio respiratory fitness in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Exerc. Nutr. Biochem. 2018, 22, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surapichpong, S.; Jisarojito, S.; Surapichpong, C. A comparison of new cardiovascular endurance test using the 2-minute marching test vs. 6-minute walk test in healthy volunteers: A crossover randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, S.D.; Eliasziw, M.; Donner, A. Sample size and optimal designs for reliability studies. Stat. Med. 1998, 17, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories; American Thoracic Society. ATS statement: Guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 166, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakut Ozdemir, H.; Bozdemir Ozel, C.; Dural, M.; Yalvac, H.E.; Al, A.; Murat, S.; Mert, G.O.; Cavusoglu, Y. The 6-minute walk test and fall risk in patients with heart failure: A cross-sectional study. Heart Lung 2024, 64, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, E.; Tutuş, N.; Aydogdu, Y.; Ozmen, I. Clinical correlates and prognostic significance of cardiopulmonary recovery time after 6-minute walk test in COPD versus interstitial lung disease patients. Heart Lung 2025, 74, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, F.K.; Chen, D.; Sharma, P.; Adsett, J.; Hwang, R.; Roberts, L.; Bach, A.; Louis, M.; Morris, N. Physiological Responses to Sit-to-Stand and Six-Minute Walk Tests in Heart Failure: A Randomised Trial. Heart Lung Circ. 2025, 34, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Just, I.A.; Schoenrath, F.; Passinger, P.; Stein, J.; Kemper, D.; Knosalla, C.; Falk, V.; Knierim, J. Validity of the 6-Minute Walk Test in Patients with End-Stage Lung Diseases Wearing an Oronasal Surgical Mask in Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Respiration 2021, 100, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanth, M.S.; Awad, N.T. Six Minute Walk Test: A Tool for Predicting Mortality in Chronic Pulmonary Diseases. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, OC34–OC38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.; Jeon, J.; Lee, J.E.; Park, S.H.; Kang, D.O.; Park, E.J.; Lee, D.I.; Choi, J.Y.; Roh, S.Y.; Na, J.O.; et al. Prognostic value of the six-minute walk test in patients with cardiovascular disease. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, F.; Sweeney, G.; Pierre, A.; Plusch, T.; Whiteson, J. Validation of a 2 minute step test for assessing functional improvement. Open J. Ther. Rehabil. 2017, 5, 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Berlanga, L.A.; Matos-Duarte, M.; Abdalla, P.; Alves, E.; Mota, J.; Bohn, L. Validity of the two-minute step test for healthy older adults. Geriatr. Nurs. 2023, 51, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haley, S.M.; Fragala-Pinkham, M.A. Interpreting change scores of tests and measures used in physical therapy. Phys. Ther. 2006, 86, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.; Liu, C.H.; Fan, C.W.; Lu, C.P.; Lu, W.S.; Hsieh, C.L. The test-retest reliability and the minimal detectable change of the Purdue pegboard test in schizophrenia. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2013, 112, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.