Abstract

Background: Several genes and genomic regions have been implicated in COVID-19 susceptibility and severity, but their clinical relevance remains uncertain. We comprehensively assessed both copy number variants (CNVs) and single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) disrupting genes implicated in COVID-19 in a Swedish cohort of ICU-treated COVID-19 patients with detailed phenotype data. Methods: Patients (n = 301) with severe COVID-19 treated in intensive care units (ICU) between March 2020 and January 2021 at two large Swedish university hospitals were included. Whole exome sequencing (WES) was performed to identify both large copy number variations (CNVs) and single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), including small indels, using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) pipelines. We focused our analyses on variants disrupting coding genes implicated in severe COVID-19, but also assessed variants known to cause human disease. Results: We identified 11 rare CNVs and several SNVs potentially linked to severe COVID-19. Patients carrying a CNV spanning a COVID-19-implicated gene had higher levels of the heart failure marker NT-proBNP (median 4440 [1558–8160] vs. 1170 [329–3152], p = 0.017), worse renal function at ICU admission (p = 0.0026), and a higher need for continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) (28% vs. 10%, p = 0.045) compared to patients without a potentially damaging CNV. Conclusions: Although patients with a potentially damaging CNV or SNV exhibited some differences in cardiac and renal markers, our findings do not support broad genetic screening as a predictive tool for COVID-19 severity.

1. Introduction

Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 and variation in disease severity of COVID-19 have been shown to have a genetic component, where genes related to lung function, cardiovascular dysfunction, coagulation deficiencies, and immune response have been implicated [1,2,3,4,5,6]. However, most research initiatives have focused on common genetic variants and rare single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), while the importance of structural variants (SVs), including copy number variations (CNVs), has not been equally explored.

The COVID-19 Host Genomics Initiative (HGI), a global effort aimed at identifying genetic factors important in severe COVID-19 [7,8], and other large initiatives [9,10] have identified genes involved in the pathogenesis of COVID-19, significantly improving our understanding of the underlying genetic pathogenesis. The additive effect of common genetic variation explains only about 1% of severe COVID-19 [4] and thus lacks clinical utility on an individual level. Studies on rare SNVs and COVID-19 severity have suggested potential clinical relevance [11], but findings have been inconsistent [12].

Here, leveraging prior knowledge, we investigate the clinical relevance of genetic findings by comprehensively analyzing both CNVs and SNVs in a cohort of 301 critically ill Swedish COVID-19 patients. Using whole-exome sequencing data and detailed clinical ICU data, genetic factors implicated in COVID-19 are scrutinized in a clinical context.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Cohort

Clinical data and blood samples were collected from 301 individuals, 24% women, and three pairs of first-degree relatives with severe COVID-19 (all patients were included individually and not as relatives). Severe COVID-19 was defined as intensive care unit (ICU) treatment. Patients were recruited from two large university hospitals in Sweden during the initial wave of COVID-19 (March 2020–January 2021) prior to available SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Whole exome sequencing (WES) was performed to identify rare genetic variants (both small and large) potentially influencing disease severity.

2.2. Variant Calling and Annotation

Variant calling from short-read, Illumina-generated, exome sequencing data was performed using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) suite. The new GATK-gCNV algorithm, especially developed to accurately identify rare CNVs in exome data, was used to call CNVs [13], while the Haplotype Caller was used for calling SNVs and short indels [14]. Quality control was performed separately for the two analyses, with cutoffs as suggested by the software authors [Supplementary Material]. Variants were aligned to the genomic build GRCh38, and the Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) [15] was used to annotate the quality-controlled VCF files. Population frequencies from gnomAD were used, and updated ClinVar annotations were downloaded from the official NCBI FTP site (https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pub/clinvar/, accessed on 10 March 2025).

2.3. CNV Prioritization and Filtering

Only gene transcripts annotated by VEP as ‘canonical transcript’ were considered for both the CNV and SNV analysis. Because CNV calling is less accurate for certain genomic regions when WES data is used, only the 15,734 genes assessed by the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) as technically reliable for CNV calling in WES data were investigated [16]. Further, because the study focused on clinically actionable CNVs, we restricted the analysis to gene deletions only. This was performed for two reasons: firstly, it is more difficult to confidently detect duplicated genomic segments in WES data [17], and secondly, the functional impact of a genomic duplication is harder to predict and leads to uncertain interpretations. After quality control, we filtered for rare CNVs disrupting coding genes using a frequency cut-off of <0.5%, as suggested by gnomAD [16].

Unfortunately, samples from one sub-site (n = 96, batch 1) had a read depth variability that was too high for confident CNV calling, and these samples were therefore excluded from the CNV analysis but could be kept for the SNV analysis. Therefore, a total of 205 ICU-treated COVID-19 patients were assessed for disrupting CNVs in genes linked to COVID-19.

To identify potential clinically relevant gene deletion, we employed a filtering strategy with three arms [details in Supplementary Material]. We identified all gene deletions that spanned the canonical transcript of genes in

- (1)

- The curated (green-listed) COVID-19 research gene panel from PanelApp (https://panelapp.genomicsengland.co.uk, accessed on 10 November 2024), Genomics England.

- (2)

- The Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) morbid map (4442 genes) [18], which is a comprehensive resource that catalogs all known genetic diseases and describes what is known about their molecular pathogenesis.

- (3)

- A condensed list of genes implicated in COVID-19 pathogenesis from the largest GWASs and candidate gene studies to date [Supplementary Material].

2.4. SNV Prioritization and Filtering

Because knowledge about SNVs and short indels is much greater than for CNVs, we leveraged prior knowledge and focused on rare SNVs that have previously been classified as either pathogenic or likely pathogenic (non-conflicting evidence) in the curated NCBI database ClinVar [19]. Both pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants are considered clinically actionable by the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) [20]. Here, we used a more stringent frequency cutoff (0.1%) to define a rare variant. This was performed because allele frequencies for SNVs are much more likely to be correct due to larger reference databases. As shown by Lek et al., virtually all known disease variants will be captured, even for recessive disorders, using a frequency cutoff < 0.1% [21]. For the SNV analysis, we also explored variants unknown to ClinVar where predicted loss-of-function (pLoF) variants resided in genes likely to be haploinsufficient (LOUEF score cutoff < 0.35) and thus most likely to cause a clinical disorder on an individual level.

2.5. Clinical Data

Clinical phenotype data were available for all patients. This detailed information was collected during each patient’s ICU stay and consisted of over a hundred variables, including age, sex, BMI, preexisting medical conditions, length of stay (LOS) in the ICU, time on ventilator, need for vasoactive treatment and continuous renal replacement therapy, 90-day survival, and numerous common laboratory results.

2.6. Data Analysis

All figures and downstream analyses were performed in R (version 4.3.2). Statistical inference was performed using linear and/or logistic regression models adjusted for age and sex. Normality of continuous variables was assessed using histograms and Q-Q plots, and variables were transformed when appropriate to meet model assumptions. For genetic comparisons involving small numbers of observations or low expected counts, Fisher’s exact test was used. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.7. Ethics Statement

Ethical approval was granted by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority [Supplementary Material]. Informed written consent was obtained from severely ill COVID-19 patients or their next of kin, if the patient was unable to give consent. Blood samples were collected and pseudonymized prior to analysis to maximize patient confidentiality.

3. Results

A total of 301 ICU-treated COVID-19 patients were included. To assess disease severity, detailed clinical ICU data were collected and analyzed [Section 2]. The newly developed GATK-gCNV algorithm was used to identify CNVs, while HaplotypeCaller was used to call SNVs. Given the low overall heritability of severe COVID-19 (≈1%) [4], we hypothesized that relevant genetic variants (i.e., clinically actionable) must be rare in the general population. Using previously published cutoffs, we therefore focused on variants with a population frequency < 0.5% for CNVs and <0.1% for SNVs that disrupted coding genes implicated in COVID-19 or associated with human disease [Section 2].

3.1. CNV Analysis

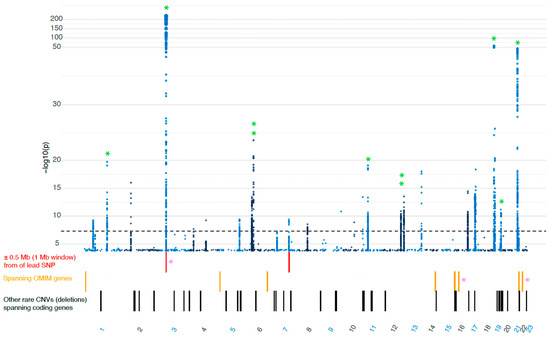

Common and rare SNVs have been extensively studied in relation to COVID-19 [7,8,9,10], but the impact of CNVs in severe cases remains less understood. In our cohort of ICU-treated patients, we identified 61 rare CNVs (deletions with an allele frequency below 0.5%) disrupting coding genes. To identify potentially clinically relevant CNVs, we applied three different filter strategies [details in Section 2]. After filtering, 11 separate deletions of interest in 14 individuals were identified, all with potential clinical relevance. Three deletions, in three separate individuals, disrupted genes previously implicated in COVID-19 severity, while eight large deletions involved genes classified as disease-associated in OMIM (Figure 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1.

The genomic location of the 61 rare deletions identified in our COVID-19 cohort, plotted in relationship to the largest GWAS focused on severe COVID-19 (cases = 21,294, controls = 2,182,461, COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative, Release 7) [22] * PINK = genes implicated in COVID-19, * GREEN = locus also overlaps with COVID-19 susceptibility locus. SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; OMIM, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man database; CNV, copy number variation.

Table 1.

CNV findings are listed by location and annotations. PINK = COVID-19 implicated ORANGE = OMIM genes not linked to COVID-19. OMIM, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man; Louef, loss-of-function observed/expected upper bound fraction; CNV, copy number variation; AR, autosomal recessive; AD, autosomal dominant; LoF, loss of function; GoF, gain of function.

Two of the large deletions, found on 22q11 and 16p11, matched two well-described syndromes. (1) The first individual had a deletion known to cause 22q11 deletion syndrome, also known as DiGeorge syndrome [23]. The deletion larger than 2 Mbp spanned the gene TBX1, which has previously been implicated in COVID-19 severity, but evidence for its action in COVID-19 pathogenesis is limited [24,25]. (2) The second individual had a deletion matching the 16p11.2 recurrent deletion syndrome [26] and spanned the gene CORO1A, which has also been implicated in COVID-19 severity [27,28]. The third deletion spanned the entire XCR1 gene, which has been suggested to be one of the candidate genes to underlie the strong GWAS signal(s) on chromosome 3p21 [29,30,31]. The deletion of XCR1 was located in the 3p21 GWAS locus, very close (<0.5 Mb) to the lead SNP [22] (Figure 1). Additionally, in a fourth individual, we identified a deletion of the gene CNPY4, which also localized to a previously known GWAS locus on 7q22.1. However, the gene CNPY4 has not previously been implicated in COVID-19 [Supplementary Material].

3.2. Clinical Presentation (CNV Patients)

The clinical presentation of each patient with a CNV finding is summarized in (Table 2). Characteristics of patients without a potentially damaging CNV or SNV are summarized in (Table 3). There was no difference in the ICU length of stay (LOS) (median 10 days); however, the CNV patients required more supportive care compared to patients without a potentially damaging CNV. Time on a ventilator differed between the groups (median 3.2 days for the CNV patients vs. 1 day for the non-CNV group), and so did the 90-day survival rate (57% vs. 72%), although none of these results were statistically significant when adjusting for age and sex. The CNV group had worse renal function at ICU admission, measured as creatinine concentration (median 91 μmol/L [76–536] vs. 75 μmol/L [61–98], p = 0.0026) and had a significantly higher need for continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) (28% vs. 10%, p = 0.045). The CNV patients also displayed a significantly higher NT-proBNP (median 4440 ng/L [1558–8160] vs. 1170 ng/L [429–3155], p = 0.017) compared to patients without a potentially damaging CNV.

Table 2.

CNV patient characteristics before, during, and after intensive care, including intensive care outcome. ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; BMI, body mass index; CNV, copy number variation; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LOS, length of stay; BNP/NT-pro-BNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; PFI, fraction of inspired oxygen ratio (PaO2/FiO2); SAPS, simplified acute physiology score.

Table 3.

Patient characteristics for those without rare, potentially damaging copy number variants (CNVs) or single-nucleotide variants (SNVs). ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRP, C-reactive protein; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide.

3.3. SNV Analysis

We also performed an analysis focused on rare coding sequence variants (SNVs and small indels) [Methods]—focusing on those with known clinical relevance. Unlike CNVs, the contribution of SNVs to disease is better understood and supported by larger reference datasets. We chose to concentrate on the >2.4 million variants that consistently have been labeled as either pathogenic (P) or likely pathogenic (LP) in the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) curated variant database ClinVar [19].

3.4. No Enrichment of Pathogenic Variants in Severe COVID-19

Confining our analysis to rare, non-conflicting ClinVar P/LP variants (i.e., clinically actionable variants), we identified 404 alleles (353 unique variants) affecting 296 separate genes in 301 ICU-treated patients—an average of 1.34 previously known clinically actionable variants per person. However, this number did not differ from our population-based [32] control group (SweGen), where an average of 1.37 variants/person was observed (p = 0.80) [Supplementary Material]. Similarly, 8.4% of these variants affected COVID-19-related genes vs. 9.1% in controls (p = 0.69). Naturally, many of these variants reside in genes known to cause recessive disease and might therefore be of less interest. When instead focusing on predicted loss-of-function (pLoF) variants in genes likely to be haploinsufficient (LOEUF < 0.35), we noted a non-significant enrichment in the severe COVID-19 cohort (OR = 2.21 [0.18–19.4], p = 0.33). Although the overall proportion of clinically actionable variants did not differ, gene-specific effects could exist since a large proportion of the pathogenic variants (~35%) in our COVID-19 cohort resided in genes not disrupted in the population controls [Supplementary Material].

3.5. SNV Findings

We identified 28 variants (13 missense, 3 indels, and 12 pLoF) likely to cause a dominant clinical condition, including porphyria, polycystic kidney disease, metabolic disorders, and coagulation defects [Supplementary Material]. In an extended analysis, we also explored genetic variations not previously classified as disease-causing in ClinVar, but where loss-of-function had been described to cause a dominant disorder (i.e., haploinsufficiency), implicated in COVID-19 pathogenesis [Section 2]. Applying these criteria, we identified 12 additional pLoF variants in 12 different genes, where only SRP54 (signal recognition particle 54), known to be a cause of neutropenia with dominant inheritance [33], had been described in COVID-19 severity [34] [Supplementary Material].

4. Discussion

Here, in a cohort of severely ill, ICU-treated COVID-19 patients, we have explored the prevalence of disrupting copy number variants (CNVs) and single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) potentially affecting COVID-19 severity. Our goal was to identify clinically significant genetic variants influencing disease severity through the combined analysis of whole-exome sequencing data and detailed clinical phenotypes. We focused on rare genetic variants disrupting genes implicated in COVID-19 pathogenesis or known to cause human diseases using three filtering strategies: OMIM haploinsufficient genes, PanelApp (Genomics England), and candidate genes from large COVID-19 GWAS studies. This approach allowed us to provide a comprehensive exploration of the genetic landscape and integrate well-established genetic knowledge while also considering emerging research to enhance the robustness of our findings.

During the first and second waves of COVID-19, approximately 11% of all hospitalized Swedish patients required ICU care [35]. Despite finding no enrichment of pathogenic variants in ICU-treated patients, a significant proportion of the ICU cohort (17%) carried at least one genetic variant of potential relevance. We also identified several individuals with variants (both CNVs and SNVs) likely to cause clinical disease. Our results showed that patients with a potentially damaging CNV had a significantly worse renal function at ICU admission and a greater need for continuous renal replacement therapy during their ICU stay. They also had a significantly higher NT-proBNP than patients without a damaging CNV, indicating an increased cardiac load. Although an elevated NT-proBNP is foremost a marker of heart failure, it is also often elevated in chronic kidney disease (CKD) [36,37,38]. Hence, it is not unexpected that both impaired renal function and signs of increased cardiac load co-exist. Severe COVID-19 has been associated with both acute kidney injury and progression of chronic kidney disease [39]. Moreover, elevated NT-proBNP levels are thought to indicate higher risks in CKD patients than in non-CKD patients [40]. Two out of the four CNV patients who needed CRRT had gene deletions with plausible biological relevance. One individual had a deletion in the gene CRYAA, which is almost exclusively expressed in the eye and kidney, but only known to cause a dominant form of cataract in humans. The second individual had a deletion of the gene CELA2A, where heterozygous deleterious variants are associated with early-onset metabolic syndrome and atherosclerosis [41]. This patient had chronic kidney failure before ICU admission, and his metabolic profile (including hypertension, diabetes, and obesity in addition to CKD) conforms to the genetic finding.

Although we cannot demonstrate causality, the clinical presentation varied widely, and we observed that a subset of the CNV patients developed a more severe disease course. First, the deletion of XCR1 was found within the strongest GWAS locus found to date (3p21), associated with both susceptibility, severity, and hospitalizations in COVID-19 cases [3,29,30,42]. This GWAS locus involves multiple immune-related genes, but the underlying effector gene has not yet been established. XCR1, encoding a chemokine receptor expressed by dendritic cells [43], has been suggested as a candidate gene to underlie the strong GWAS signal [29,30]. The patient carrying the XCR1 deletion spent 10 days at the ICU with the need for both invasive mechanical ventilation and vasoactive treatment. This patient also had elevated troponin I and NT-proBNP (Table 2), indicating cardiac injury, which has been associated with a lower survival rate [44].

Another notable finding was in the patient carrying a deletion in CELA2A, a gene associated with metabolic syndrome [41], which is a known risk factor for severe COVID-19. The affected patient was obese (BMI 33) and had hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes—all components of the metabolic syndrome. This patient stayed 15 days in intensive care and 11 days on a ventilator.

Similarly, the deletion in the CNPY4 gene on chromosome 7, also within a GWAS locus, could be relevant as it regulates immune function, and hyperinflammation is one of the cardinal symptoms of severe COVID-19 [45]. Variants in genes regulating any of these steps are therefore highly interesting when exploring COVID-19 severity. The CNV analysis also identified two patients with two separate known syndromes, the 22q11 deletion syndrome and the 16p11.2 recurrent deletion syndrome. These syndromes can affect an individual’s general health and could, as such, increase the risk of severe COVID-19. Interestingly, both these deletion syndromes are associated with immunodeficiency [23,28] and include genes previously implicated in COVID-19 severity (TBX1 [24] on chromosome 22q11 and CORO1A [46] on chromosome 16p11.2). The young, less than 30-year-old, individual who carried the 22q11 deletion had no other risk factors for severe COVID-19, suggesting that the deletion syndrome may have increased his vulnerability. He stayed 11 days in the ICU, including 7 days on a ventilator with vasoactive treatment. This considerably longer need for invasive supportive care compared to patients without a CNV is notable, given his young age.

In contrast, the patient with a 16p11.2 deletion (associated with immunodeficiency 8) had an extreme BMI of 66, which likely contributed to the ICU admission. Interestingly, the deletion breakpoint was just 0.7 Mb from the gene SH2B1, known to cause monogenic childhood-onset obesity [47,48], and sometimes spanned by the recurrent deletions at this chromosomal location (16p11.2) [49]. Although deletions can be identified using WES data, the exact deletion breakpoints are less accurately called compared to whole genome sequencing (WGS), which is why a genetic cause of her high BMI cannot be excluded.

The CNV- and SNV-related conditions were, however, mostly isolated to individual cases and spread over a wide range of genes with different functions. This indicates that rare genetic variants may not directly contribute to COVID-19 severity, but instead, as with high age, male sex, pre-existing medical conditions, and socioeconomic factors [50,51,52,53], affect an individual’s overall frailty. Frailty, a term constructed to capture a person’s general health and well-being, is often impacted in rare diseases and genetic syndromes [54], but it is also a known and important risk factor for ICU-treated patients [55].

5. Conclusions

In our cohort with ICU-treated COVID-19 patients, we identified both CNVs and SNVs likely to cause clinical conditions, suggesting that rare genetic variants may contribute to COVID-19 disease severity in specific cases. However, the overall heterogeneity of our findings, with individually isolated and varying genetic conditions, does not support a direct impact on COVID-19 pathogenesis but possibly an increased overall frailty, making their clinical utility low.

6. Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the overall sample size was moderate, which may limit the statistical power to detect smaller effects and reduce the generalizability of the results. In addition, only a small proportion of patients were identified as having a clinically significant CNV (n = 14), which further restricts the robustness of the analysis. The absence of a suitable comparison group, such as patients with a mild COVID-19 disease course, limits our ability to directly assess whether the observed genetic findings are specific to the severe disease or represent broader background variation. Further, our analysis was limited to CNVs detectable by WES, i.e., spanning exonic regions. Patients classified as ‘not having a CNV’ could therefore have carried structural variants relevant for disease affecting regulatory and/or other non-coding regions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/covid6010010/s1, Figures S1 and S2: Quality control and variant prioritization; Databases for filtering; Figure S3: COVID-19 condensed list; Table S1: Pathogenic variants in patients and controls; CNVs implicated in COVID-19; Table S2: Chromosomal location of CNVs; No enrichment of pathogenic variants in severe COVID-19; SNV findings; Figure S4 and Table S3: Several individuals had genetic variants known to cause a clinical condition; Table S4: Exploratory SNV analysis; Table S5: SNV patient characteristics; Ethical permits; Supplementary references.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K., J.E., P.N., A.N., M.N., M.L., M.M.-H., R.F., J.G., O.R., H.Z., and A.K.; methodology, J.K., J.E., P.N., and A.K.; software, validation and formal analysis, J.K., J.E., and A.K.; resources and data curation, J.K., M.L., M.M.-H., R.F., J.G., and O.R.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K.; writing—review and editing, J.E., P.N., A.N., M.N., M.L., M.M.-H., R.F., J.G., O.R., H.Z., and A.K.; visualization, J.K., J.E., and A.K.; supervision, P.N., A.N., MN., H.Z., and A.K.; funding acquisition, M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partly funded by the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation. Anders Kämpe is supported by Svenska Sällskapet för Medicinsk Forskning (SSMF), grant nr PD20-0190.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (protocol code 2017-043 (with amendments 2019-00169, 2020-01623, 2020-02719, 2020-05730, 2021-01469), as well as de novo application 2020-02322, 2020-05618, 2022-00526-01, and 2020-01302), 20 May 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study, or their next of kin, if the patient was unable to give consent.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study may be made available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, due to privacy and/or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank all patients and families who participated in this study. We also sincerely thank the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACMG | American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| CNV | Copy Number Variant |

| CRRT | Continuous renal replacement therapy |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| ExAC | Exome Aggregation Consortium |

| FTP | File Transfer Protocol |

| GATK | Genome Analysis Toolkit |

| gnomAD | The Genome Aggregation Database |

| GWAS | Genome-wide association study |

| HGI | COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| Indel | Insertion/deletion |

| IFN | Interferon |

| LOEUF | Loss-of-function observed/expected upper bound fraction |

| LOS | Length of stay |

| MB/Mb | Megabase |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide |

| OMIM | Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man |

| p | p-value |

| PFI | fraction of inspired oxygen ratio (PaO2/FiO2) |

| pLoF | Predicted loss-of-function |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| SNV | Single-nucleotide variant |

| SV | Structural variant |

| VEP | Variant Effect Predictor |

| WES | Whole exome sequencing |

| WGAS | Whole genome sequencing |

References

- Di Maria, E.; Latini, A.; Borgiani, P.; Novelli, G. Genetic variants of the human host influencing the coronavirus-associated phenotypes (SARS, MERS and COVID-19): Rapid systematic review and field synopsis. Hum. Genom. 2020, 14, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, S.; Song, F.; Guo, W.; Tan, J.; Zhang, X.; Qiao, F.; Guo, J.; Zhang, L.; Jia, X. Potential Genes Associated with COVID-19 and Comorbidity. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 19, 402–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemi, M.E.K.; Daly, M.J.; Ganna, A. The human genetic epidemiology of COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zguro, K.; Fallerini, C.; Fava, F.; Furini, S.; Renieri, A. Host genetic basis of COVID-19: From methodologies to genes. Eur. J. Hum. Genetics. 2022, 30, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlén, T.; Li, H.; Nyberg, F.; Edgren, G. A population-based, retrospective cohort study of the association between ABO blood group and risk of COVID-19. J. Intern. Med. 2023, 293, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamenarova, K.; Kachakova-Yordanova, D.; Baymakova, M.; Georgiev, M.; Mihova, K.; Petkova, V.; Beltcheva, O.; Argirova, R.; Atanasov, P.; Kunchev, M.; et al. Rare host variants in ciliary expressed genes contribute to COVID-19 severity in Bulgarian patients. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velavan, T.P.; Pallerla, S.R.; Rüter, J.; Augustin, Y.; Kremsner, P.G.; Krishna, S.; Meyer, C.G. Host genetic factors determining COVID-19 susceptibility and severity. eBioMedicine 2021, 72, 103629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemi, M.E.K.; Karjalainen, J.; Liao, R.G.; Neale, B.M.; Daly, M.; Ganna, A.; Pathak, G.A.; Andrews, S.J.; Kanai, M.; Veerapen, K.; et al. Mapping the human genetic architecture of COVID-19. Nature 2021, 600, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redin, C.; Thorball, C.W.; Fellay, J. Host genomics of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2022, 30, 908–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellinghaus, D.; Degenhardt, F.; Bujanda, L.; Buti, M.; Albillos, A.; Invernizzi, P.; Fernández, J.; Prati, D.; Baselli, G.; Asselta, R.; et al. Genomewide Association Study of Severe COVID-19 with Respiratory Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1522–1534. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Bastard, P.; Liu, Z.; Le Pen, J.; Moncada-Velez, M.; Chen, J.; Ogishi, M.; Sabli, I.K.D.; Hodeib, S.; Korol, C.; et al. Inborn errors of type I IFN immunity in patients with life-threatening COVID-19. Science 2020, 370, eabd4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Povysil, G.; Butler-Laporte, G.; Shang, N.; Wang, C.; Khan, A.; Alaamery, M.; Nakanishi, T.; Zhou, S.; Forgetta, V.; Eveleigh, R.J.; et al. Rare loss-of-function variants in type I IFN immunity genes are not associated with severe COVID-19. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babadi, M.; Fu, J.M.; Lee, S.K.; Smirnov, A.N.; Gauthier, L.D.; Walker, M.; Benjamin, D.I.; Zhao, X.; Karczewski, K.J.; Wong, I.; et al. GATK-gCNV enables the discovery of rare copy number variants from exome sequencing data. Nat. Genet. 2023, 55, 1589–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poplin, R.; Ruano-Rubio, V.; DePristo, M.A.; Fennell, T.J.; Carneiro, M.O.; Van der Auwera, G.A.; Kling, D.E.; Gauthier, L.D.; Levy-Moonshine, A.; Roazen, D.; et al. Scaling accurate genetic variant discovery to tens of thousands of samples. bioRxiv 2018, 201178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, W.; Gil, L.; Hunt, S.E.; Riat, H.S.; Ritchie, G.R.; Thormann, A.; Flicek, P.; Cunningham, F. The Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karczewski, K.J.; Weisburd, B.; Thomas, B.; Solomonson, M.; Ruderfer, D.M.; Kavanagh, D.; Hamamsy, T.; Lek, M.; Samocha, K.E.; Cummings, B.B.; et al. The ExAC browser: Displaying reference data information from over 60,000 exomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D840–D845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandiracioglu, B.; Ozden, F.; Kaynar, G.; Yilmaz, M.A.; Alkan, C.; Cicek, A.E. ECOLE: Learning to call copy number variants on whole exome sequencing data. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine JHUB, MD. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, OMIM®. Available online: https://omim.org/ (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- Resource, C.G. ClinVar [2024-02-18]. Available online: https://erepo.clinicalgenome.org/evrepo/ (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lek, M.; Karczewski, K.J.; Minikel, E.V.; Samocha, K.E.; Banks, E.; Fennell, T.; O’Donnell-Luria, A.H.; Ware, J.S.; Hill, A.J.; Cummings, B.B.; et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 2016, 536, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID19-hg GWAS Meta-Analyses Round 7. Available online: https://www.covid19hg.org/results/r7/ (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- McDonald-McGinn, D.M.; Sullivan, K.E.; Marino, B.; Philip, N.; Swillen, A.; Vorstman, J.A.S.; Zackai, E.H.; Emanuel, B.S.; Vermeesch, J.R.; Morrow, B.E.; et al. 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2015, 1, 15071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, T.B.; McGinn, D.M.; Sullivan, K.E. 22q11.2 Deletion and Duplication Syndromes and COVID-19. J. Clin. Immunol. 2022, 42, 746–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulvirenti, F.; Mortari, E.P.; Putotto, C.; Terreri, S.; Fernandez Salinas, A.; Cinicola, B.L.; Cimini, E.; Di Napoli, G.; Sculco, E.; Milito, C.; et al. COVID-19 Severity, Cardiological Outcome, and Immunogenicity of mRNA Vaccine on Adult Patients With 22q11.2 DS. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2023, 11, 292–305.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niarchou, M.; Chawner, S.J.R.A.; Doherty, J.L.; Maillard, A.M.; Jacquemont, S.; Chung, W.K.; Green-Snyder, L.; Bernier, R.A.; Goin-Kochel, R.P.; Hanson, E.; et al. Psychiatric disorders in children with 16p11.2 deletion and duplication. Transl. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 8. [Google Scholar]

- OMIM COROA1. Available online: https://omim.org/entry/605000?search=coro1a&highlight=coro1a (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- Maggadottir, S.M.; Li, J.; Glessner, J.T.; Li, Y.R.; Wei, Z.; Chang, X.; Mentch, F.D.; Thomas, K.A.; Kim, C.E.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Rare variants at 16p11.2 are associated with common variable immunodeficiency. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 135, 1569–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, L.; Griffini, S.; Lamorte, G.; Grovetti, E.; Uceda Renteria, S.C.; Malvestiti, F.; Scudeller, L.; Bandera, A.; Peyvandi, F.; Prati, D.; et al. Chromosome 3 cluster rs11385942 variant links complement activation with severe COVID-19. J. Autoimmun. 2021, 117, 102595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, E.; Frauke, D.; Luis, B.; Maria, B.; Agustín, A.; Pietro, I.; Javier, F.; Daniele, P.; Guido, B.; Rosanna, A.; et al. The ABO blood group locus and a chromosome 3 gene cluster associate with SARS-CoV-2 respiratory failure in an Italian-Spanish genome-wide association analysis. medRxiv 2020. medRxiv:2020.05.31.20114991. [Google Scholar]

- Zeberg, H.; Pääbo, S. The major genetic risk factor for severe COVID-19 is inherited from Neanderthals. Nature 2020, 587, 610–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameur, A.; Dahlberg, J.; Olason, P.; Vezzi, F.; Karlsson, R.; Martin, M.; Viklund, J.; Kähäri, A.K.; Lundin, P.; Che, H.; et al. SweGen: A whole-genome data resource of genetic variability in a cross-section of the Swedish population. Eur. J. Hum. Genetics. 2017, 25, 1253–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carapito, R.; Konantz, M.; Paillard, C.; Miao, Z.; Pichot, A.; Leduc, M.S.; Yang, Y.; Bergstrom, K.L.; Mahoney, D.H.; Shardy, D.L.; et al. Mutations in signal recognition particle SRP54 cause syndromic neutropenia with Shwachman-Diamond–like features. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 4090–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingelbach, K.; Zwieb, C.; Webb, J.R.; Marshallsay, C.; Hoben, P.J.; Walter, P.; Dobberstein, B. Isolation and characterization of a cDNA clone encoding the 19 kDa protein of signal recognition particle (SRP): Expression and binding to 7SL RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988, 16, 9431–9442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweden, S.S. Statistics on COVID-19. Available online: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/en/statistics-and-data/statistics/ (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- Takase, H.; Dohi, Y. Kidney function crucially affects B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), N-terminal proBNP and their relationship. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2014, 44, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Oishi, E.; Nagata, T.; Sakata, S.; Chen, S.; Furuta, Y.; Honda, T.; Yoshida, D.; Hata, J.; Tsuboi, N.; et al. N-Terminal Pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide and Incident CKD. Kidney Int. Rep. 2021, 6, 976–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Hsu, Y.-C.; Chou, K.-W.; Chang, K.-S.; Hsu, Y.-H.; Chiu, W.-H.; Lee, C.-W.; Yang, P.-S.; Chang, W.-H.; Huang, Y.-K.; et al. NT-proBNP point-of-care testing for predicting mortality in end-stage renal disease: A survival analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultström, M.; Lipcsey, M.; Wallin, E.; Larsson, I.M.; Larsson, A.; Frithiof, R. Severe acute kidney injury associated with progression of chronic kidney disease after critical COVID-19. Crit. Care 2021, 25, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuen, B.L.; Vaduganathan, M.; Claggett, B.L.; Beldhuis, I.; Myhre, P.; Desai, A.S.; Skali, H.; Mc Causland, F.R.; McGrath, M.; Anand, I.; et al. Natriuretic Peptides, Kidney Function, and Clinical Outcomes in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2025, 13, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteghamat, F.; Broughton, J.S.; Smith, E.; Cardone, R.; Tyagi, T.; Guerra, M.; Szabó, A.; Ugwu, N.; Mani, M.V.; Azari, B.; et al. CELA2A mutations predispose to early-onset atherosclerosis and metabolic syndrome and affect plasma insulin and platelet activation. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 1233–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pairo-Castineira, E.; Clohisey, S.; Klaric, L.; Bretherick, A.D.; Rawlik, K.; Pasko, D.; Walker, S.; Parkinson, N.; Fourman, M.H.; Russell, C.D.; et al. Genetic mechanisms of critical illness in COVID-19. Nature 2021, 591, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heger, L.; Hatscher, L.; Liang, C.; Lehmann, C.H.K.; Amon, L.; Lühr, J.J.; Kaszubowski, T.; Nzirorera, R.; Schaft, N.; Dörrie, J.; et al. XCR1 expression distinguishes human conventional dendritic cell type 1 with full effector functions from their immediate precursors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2300343120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García de Guadiana-Romualdo, L.; Morell-García, D.; Rodríguez-Fraga, O.; Morales-Indiano, C.; María Lourdes Padilla Jiménez, A.; Gutiérrez Revilla, J.I.; Urrechaga, E.; Álamo, J.M.; Hernando Holgado, A.M.; Lorenzo-Lozano, M.D.C.; et al. Cardiac troponin and COVID-19 severity: Results from BIOCOVID study. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 51, e13532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustine, J.N.; Jones, D. Immunopathology of Hyperinflammation in COVID-19. Am. J. Pathol. 2021, 191, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, C.S.; Massaad, M.J.; Bainter, W.; Ohsumi, T.K.; Föger, N.; Chan, A.C.; Akarsu, N.A.; Aytekin, C.; Ayvaz, D.; Tezcan, I.; et al. Recurrent viral infections associated with a homozygous CORO1A mutation that disrupts oligomerization and cytoskeletal association. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 137, 879–888.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochukova, E.G.; Huang, N.; Keogh, J.; Henning, E.; Purmann, C.; Blaszczyk, K.; Saeed, S.; Hamilton-Shield, J.; Clayton-Smith, J.; O’Rahilly, S.; et al. Large, rare chromosomal deletions associated with severe early-onset obesity. Nature 2010, 463, 666–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chermon, D.; Birk, R. Gene-Environment Interactions Significantly Alter the Obesity Risk of SH2B1 rs7498665 Carriers. JOMES 2024, 33, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrakos, A.K.; Kosma, K.; Makrythanasis, P.; Tzetis, M. The Phenotypic Spectrum of 16p11.2 Recurrent Chromosomal Rearrangements. Genes 2024, 15, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, E.J.; Walker, A.J.; Bhaskaran, K.; Bacon, S.; Bates, C.; Morton, C.E.; Curtis, H.J.; Mehrkar, A.; Evans, D.; Inglesby, P.; et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 2020, 584, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, P.; Hofmann, R.; Häbel, H.; Jernberg, T.; Nordberg, P. Association between cardiometabolic disease and severe COVID-19: A nationwide case-control study of patients requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordberg, P.; Jonsson, M.; Hollenberg, J.; Ringh, M.; Kiiski Berggren, R.; Hofmann, R.; Svensson, P. Immigrant background and socioeconomic status are associated with severe COVID-19 requiring intensive care. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kämpe, J.; Bohlin, O.; Jonsson, M.; Hofmann, R.; Hollenberg, J.; Wahlin, R.R.; Svensson, P.; Nordberg, P. Risk factors for severe COVID-19 in the young-before and after ICU admission. Ann Intensive Care 2023, 13, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaye, J.; Cacciatore, P.; Kole, A. Valuing the “Burden” and Impact of Rare Diseases: A Scoping Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 914338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Biasio, J.C.; Mittel, A.M.; Mueller, A.L.; Ferrante, L.E.; Kim, D.H.; Shaefi, S. Frailty in Critical Care Medicine: A Review. Anesth. Analg. 2020, 130, 1462–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.