Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are among the most common comorbidities in COVID-19 patients. This multicenter cross-sectional study assessed knowledge, risk perception, precautionary measures, and psychological burden related to COVID-19 among Lebanese individuals with and without CVD during the pandemic’s first wave. A total of 485 CVD patients and 1033 control group (CG) participants completed standardized questionnaires, including the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), and Coronavirus Anxiety Scale. Compared to CG, CVD patients demonstrated significantly lower COVID-19-related knowledge (86.4% vs. 90.0%, p < 0.001) and adherence to preventive measures (81.5% vs. 85.7%, p < 0.001). After stratification, limited knowledge was more common among CVD patients (45.7% vs. 31.8%), as was limited precautionary behavior (70.3% vs. 54.2%). Risk perception was suboptimal in both groups, with no significant difference (41.3% vs. 38.6%, p = 0.072). Anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 10) and depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 10) were more prevalent among CVD patients (13.4% and 11.3%) than CG participants (9.5% and 16.5%). Survey outcomes were influenced by educational, socioeconomic, and psychosocial factors. These findings highlight the need to target CVD patients in public health campaigns to enhance preparedness and mental health support during pandemics.

1. Introduction

After its detection in December 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) a public health emergency of international concern on 30 January 2020 and elevated it to pandemic status on 11 March 2020 [1]. As of 23 August 2025, over 777 million laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases and approximately 7 million deaths were reported globally [2]. In Lebanon, the first confirmed COVID-19 case appeared on 21 February 2020. As of 23 August 2025, cumulative totals reached 1,243,838 confirmed cases and 10,952 deaths, equivalent to approximately 178 deaths per 100,000 population. Globally, cumulative COVID-19 deaths stood at around 7.1 million by the same date, illustrating the sustained global impact of the pandemic [2].

COVID-19 has been particularly burdensome for individuals with cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), which have emerged as the most common comorbidities and predictors of poor outcomes in infected patients [3]. CVDs encompass cerebrovascular disease, hypertension, heart failure, coronary and peripheral artery disease, arrhythmia, and thromboembolic disorders [4]. Notably, in Lebanon, the epidemiological surveillance program of the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health reported that 82% of COVID-19 deaths involved at least one comorbidity, most commonly hypertension (59.1%), reflecting the high vulnerability of patients with underlying cardiovascular risk factors [5].

SARS-CoV-2 can damage the cardiovascular system through multiple mechanisms, including direct myocardial injury, systemic inflammation, hypoxemia and hypoperfusion, endothelial dysfunction, plaque destabilization, coagulopathy, arrhythmogenesis, and stress cardiomyopathy [3,6,7,8]. In addition to acute complications, increasing evidence highlights the persistence of cardiovascular symptoms well beyond the acute phase, termed post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) or long COVID. This syndrome may involve lingering symptoms such as chest pain, palpitations, exertional dyspnea, and fatigue, often accompanied by elevated cardiac biomarkers and clinical findings of myocarditis, fibrosis, and pericardial involvement months after recovery, even in previously healthy individuals [8,9,10]. The virus uses angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) to infiltrate target organs which are expressed in cardiac, renal, pulmonary, and intestinal tissues [6]. This initially raised concerns regarding the safety of cardiovascular medications such as ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), which may increase ACE2 expression. However, clinical evidence has not demonstrated increased risk, and both the American Heart Association (AHA) and European Society of Cardiology (ESC) have recommended continuing these therapies due to their well-established benefits in managing cardiovascular conditions [11,12]

Knowledge–attitude–practice (KAP) studies have been instrumental in understanding perceptions during the first COVID-19 wave [13], particularly among healthcare workers [14], healthy individuals [15], pregnant women [16], parents [17], and chronic disease cohorts worldwide [18,19]. In Lebanon, extensive KAP research has been conducted among the general population [20,21], pregnant women [16], parents [17], and hospital pharmacists [22]. However, until now, there has been no study specifically examining KAP among Lebanese patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD) in response to COVID-19. Previous research conducted by our team has assessed baseline KAP regarding CVD prevention in the Lebanese population [23], but the intersection of CVD and COVID-19 perspectives remains unexplored.

Beyond physical outcomes, the COVID-19 pandemic has exerted a profound psychological impact, manifesting as heightened levels of anxiety, depression, and coronavirus-specific anxiety, especially among individuals with chronic illnesses [24,25,26,27,28]. Evidence from international and regional studies indicates that psychological distress may substantially shape risk perception and precautionary practices [29,30,31]. Among patients with cardiovascular diseases, this association is particularly critical, as the coexistence of mental health difficulties and altered perceptions of risk can further compromise adherence to preventive measures and exacerbate disease management challenges [27,28].

Accordingly, this study was designed to address this gap by providing a comprehensive assessment of COVID-19-related knowledge, risk perception, precautionary behaviors, and psychological burden—including anxiety, depression, and coronavirus-related anxiety—among Lebanese patients with cardiovascular diseases during the pandemic’s first wave. By directly comparing these outcomes with those of a healthy control group, this work seeks to elucidate the multidimensional challenges faced by this vulnerable population and to generate evidence that may inform tailored public health interventions and mental health support strategies during ongoing and future health crises.

2. Materials and Methods

This study is part of a larger national project that investigates COVID-19-related knowledge, precautionary behaviors, perceptions, and psychological outcomes (anxiety and depression) in patients with various chronic diseases (cardiovascular diseases, mental disorders, lung diseases, metabolic diseases, chronic kidney diseases, cancer, and musculoskeletal disorders). The current paper focuses specifically on patients with cardiovascular diseases compared to a control group of healthy individuals.

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.1.1. Study Design and Setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted in Lebanon between 3 May and 27 May, 2020, targeting patients with cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and healthy control participants. A structured questionnaire was administered both electronically (via Google Forms) and in printed form. Participants were recruited from various private medical clinics and hospitals located across all eight governorates of Lebanon, proportionally reflecting the population distribution in five major regions: Beirut, Mount Lebanon, Bekaa (including Baalbek-Hermel), North (including Akkar), and South (including Nabatieh). Enrollment was achieved through a combination of in-person recruitment at these healthcare facilities and remote contact via telephone interviews.

2.1.2. Study Population

We included within the case group (CVD group) all patients currently diagnosed or with a history of cardiovascular diseases (hypertension, heart failure, atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease, and thrombosis (e.g., deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism)), whereas the control group (CG) included all subjects without chronic conditions (cardiovascular diseases, mental disorders, lung diseases, metabolic, chronic kidney diseases, cancer, musculoskeletal disorders).

2.1.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All participants were required to be ≥18 years of age, residing in Lebanon, and to provide informed consent. We excluded any participant under the age of 18 or who refused to fill in the survey.

2.1.4. Sample Size Calculation

Slovin’s formula was used to calculate a representative sample of the Lebanese general population, , with N representing the Lebanese population (following the Index Mundi registry, the Lebanese population was 6,100,075 in 2019), e is the p-value = 0.05. Therefore, a minimum of 400 patients had to fill out the questionnaire in order to be representative of the general population in Lebanon.

Cochran’s formula was used to calculate a representative sample of the patients suffering from CVD in the Lebanese population, , where Z2 is the square of the confidence interval, considered 95% in this case, which corresponds to (1.96)2, p is the estimated proportion of the Lebanese population having CVD, q is (1 − p), and e represents the p-value = 0.05, The prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidities in our targeted population is around 36% [32]. Therefore, a minimum of 355 participants with CVD were needed. The population was targeted in all 8 governorates in Lebanon.

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Survey Tool and Validation

The questionnaire was based on a survey executed and validated by Yale University [33]. Permission was granted for the reproduction of the questionnaire [21]. Additional questions were built according to updated guidelines and recommendations [34,35,36,37,38,39]. It was translated into Arabic using Fortin’s back-translation method and reviewed for clarity by a native Arabic speaker and bilingual medical expert [40]. A pre-test with 10 individuals ensured cultural appropriateness and comprehension. The questionnaire consisted of three main components (Appendix A):

- Informed consent.

This section introduced the study’s purpose, outlined participants’ rights, and confirmed that participation was entirely voluntary. It also included guarantees of data confidentiality and anonymity.

- 2.

- General questionnaire for all participants (cases and controls).

This part was composed of 103 questions divided into five key sections:

Section 1 collected sociodemographic and background data, including age, sex, region of residence, smoking status, comorbidities, and self-assessed knowledge of COVID-19.

Section 2 explored participants’ general knowledge of COVID-19, such as modes of transmission, symptoms, and prevention strategies.

Section 3 examined participants’ perceptions of the pandemic, including their beliefs about COVID-19’s severity, response measures, and personal risk.

Section 4 assessed the preventive practices adopted by participants to protect themselves against infection, such as mask-wearing, hand hygiene, and social distancing.

Section 5 included standardized psychological screening tools to assess mental health status, including the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) scale for anxiety symptoms, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for depressive symptoms, and the Coronavirus Anxiety Scale (CAS) for COVID-19-specific anxiety symptoms.

- 3.

- Cardiovascular disease (CVD)-specific questionnaire.

This section, completed only by participants with a history of cardiovascular disease, comprised 52 questions divided into four sections:

Section 1 gathered clinical information specific to cardiovascular health, including blood pressure levels, lipid profiles, and current pharmacological treatments.

Section 2 assessed participants’ knowledge regarding the heightened risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes associated with cardiovascular conditions.

Section 3 explored the perceptions of CVD patients toward their susceptibility to COVID-19 complications.

Section 4 investigated the preventive behaviors adopted by CVD patients specifically in response to the pandemic, including medication adherence and health monitoring practices.

2.2.2. Procedure for Data Collection

Data collection took place between 3 May and 27 May 2020. Participants were enrolled through a combination of in-person recruitment at private medical clinics and hospitals and remote contact via telephone interviews. Upon confirming eligibility and obtaining informed consent, participants completed either a printed version of the questionnaire during clinic visits or an electronic version distributed via Google Forms.

Trained research coordinators provided assistance when needed, especially for older or less tech-literate participants. To ensure reliability, approximately 82% of questionnaires were completed during face-to-face or telephone interviews, with data entered directly by trained physicians. Around 18% of participants self-entered their responses through the electronic Google Form. A very small proportion of printed questionnaires were entered into the database by two independent team members using a double-entry method to verify accuracy and resolve discrepancies. All completed questionnaires, whether printed or electronic, were securely compiled into a centralized database for subsequent data cleaning and analysis. Quality control measures included real-time verification of responses by the study team and follow-up where necessary to ensure completeness.

2.2.3. Measurements and Scores

All measured variables were converted into standardized scores to enable quantitative analysis.

General knowledge about COVID-19 was assessed using 14 items answered by both cases and controls, where each correct response was awarded 1 point and incorrect or “I don’t know” responses received 0 points, resulting in a total score ranging from 0 to 14.

General perception toward COVID-19 was evaluated through 10 Likert-scale items, each scored from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”), with “don’t know” assigned a score of 0. For positively framed items, “strongly agree” was designated as the highest score of 5, with “agree” scored as 4, “neutral” as 3, “disagree” as 2, and “strongly disagree” as 1. For negatively framed items, reverse scoring was applied so that “strongly disagree” received the highest score of 5 and “strongly agree” the lowest as 1. This method ensured that responses were graded rather than dichotomized, allowing for the computation of a continuous perception score ranging from 0 to 50.

General preventive practices were measured using 26 yes/no questions on behaviors related to infection control, with each correct action given 1 point and incorrect answers receiving 0 points (total range: 0–26).

Psychological status was assessed using three validated scales: the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7), consisting of 7 items scored from 0 to 3 and totaling 0 to 21 points; the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), consisting of 9 items scored on a 4-point scale to assess depressive symptoms (range: 0–27); and the Coronavirus Anxiety Scale (CAS), composed of 5 Likert-scale items assessing COVID-19-specific anxiety symptoms (range: 0–25).

CVD patients also completed a disease-specific questionnaire.

Knowledge of COVID-19 in the CVD patient section was analyzed using 16 questions. Each correct response was awarded 1 point, while incorrect and “I don’t know” answers received 0 points, for a total score ranging from 0 to 16.

Perception of COVID-19 in CVD patients included 2 questions. The questions followed a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 as follows: 1 “strongly disagree”, 2 “disagree”, 3 “neutral”, 4 “agree”, 5 “strongly agree” and 0 “don’t know”, resulting in a total perception score ranging from 0 to 50.

Preventions from COVID-19 in CVD patients included 6 questions about the preventive measures taken by CVD patients such as adhering to treatment and following recommendations. These questions were answered on a true/false basis with an additional “I don’t know” option. Each participant received a score of “1” on the correct answer and “0” on the false answer, yielding a total prevention score of 0 to 6.

All computed scores were subsequently categorized and sub-categorized into “Limited” (Poor, Fair) to “Adequate” (Good, Excellent) levels of knowledge and preventive measures, as shown in Table 1, using the median of the distribution and a modified version of Bloom’s taxonomy cut-off points validated by previously published studies by our team [23,41,42,43,44] and others [45].

Table 1.

Grading of knowledge and precautions scores about COVID-19 into categories “Limited and Adequate” and sub-categories “Poor, Fair, Good, and Excellent”.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Data were represented as frequencies and proportions for nominal variables and as mean (±SD) for continuous variables. There were a total of 6 scores: The first 5 scores of knowledge, prevention, anxiety level (GAD-7), depression level (PHQ-9), and coronavirus anxiety level were computed for CVD patients and CG subjects, whereas a 6th score of specific knowledge was calculated from the knowledge questions addressed only to CVD patients. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was calculated for the adapted scales. The knowledge, prevention, and perception scales demonstrated Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.707, 0.782, and 0.550, respectively. While knowledge and prevention showed acceptable reliability (α > 0.70), the perception scale had a lower alpha, likely due to the multidimensional nature of its items; however, it was retained to capture the diversity of participants’ views. For the standardized psychological instruments, internal consistency was also confirmed: CAS (α = 0.815), GAD-7 (α = 0.879), and PHQ-9 (α = 0.888), which are consistent with their established psychometric validity. In addition, Shapiro–Wilk’s test (p < 0.05) showed that the scores were not normally distributed, with a skewness and kurtoses out of the range (−1.96 and +1.96). We performed the Mann–Whitney test to compare continuous variables of two groups. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare the mean of 3 or more different groups. Spearman’s tests were employed to correlate between 2 continuous variables. Categorical variables were compared using a χ2 test. Multivariate linear regression models were built including all the factors that were statistically correlated with the knowledge, prevention, PHQ-9, GAD-7, coronavirus anxiety, and specific knowledge scores. Data analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 22. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board of Al Hayat Hospital (number: ETC-13-2020; date: 23 April 2020). Participation in the study was entirely voluntary. Informed consent was obtained from all participants (aged ≥ 18 years) either electronically via a statement embedded in the online survey form (“Yes, I agree to participate”) or verbally with assistance from medical staff during phone-based data collection. Data collection was anonymized: personal identifiers (e.g., names, contact details, exact birth dates) were not collected, and only direct age was provided. Each participant received a designated code. Data were securely stored with restricted access limited to the researchers. The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and ICH-GCP guidelines [46].

3. Results

3.1. Population Characteristics

3.1.1. General Characteristics of CVD Patients in Comparison with Control Group Subjects

We initially contacted 1706 subjects (1136 control group (CG) subjects and 570 patients suffering from CVD). The response rate was on average about 89%; thus, a total of 1518 subjects participated in this study, distributed into 1033 CG subjects without the chronic diseases cited above (Section 2) and 485 patients suffering from CVD. The mean age of the sample was 39.4 ± 19.5 years. CVD patients were predominantly males (47.6%), were significantly older (59.1 years), and had a higher body mass index (BMI) (28.5 Kg/m2) when compared to CG subjects (all p < 0.001). Patients, compared to CG subjects, had increased their consumption of cigarettes (9.3% vs. 4.75%, respectively, p < 0.001) since the start of the outbreak (all). The complete demographic details of CVD patients compared to CG subjects are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the control group and CVD patients. n: number of participants; p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. BMI: body mass index; overweight (BMI: 25–29.9 Kg/m2); obesity C1 (BMI: 30–34.9 Kg/m2); obesity C2 (BMI ≥ 35 Kg/m2); CVD: cardiovascular disease. * represents statistical significance.

3.1.2. Clinical Characteristics of Participants in Our Study

Among the 485 patients with CVDs included in our study, hypertension was the leading diagnosis (56.2%), followed by heart rhythm disorders (15.5%), coronary artery disease (10.5%), heart failure (7.4%), thromboembolic disease (7.1%), and cerebrovascular disease (3.5%) (Supplementary Materials, Figure S1A). Blood pressure measurements revealed a 29.8% prevalence of grade 1 and 10.3% of grade 2 systolic hypertension as well as 20.2% prevalence of grade 1 and 12.1% of grade 2 diastolic hypertension in CVD patients. Additionally, 37.5% of patients reported having hyperglycemia, while total cholesterol (<200 mg/dL) and triglyceride levels (<150 mg/dL) were normal in 42.2% and 41.1% of patients, respectively (Supplementary Materials, Figure S1B). Concerning medications, 56.2% of patients were under antihypertensive medication (beta-blockers (42.2%)) and anti-coagulants (aspirin (78%)) (Supplementary Materials, Figure S1C).

3.2. General Parameters (Knowledge, Perception, Precautions About COVID-19, Coronavirus Anxiety, GAD, and Depression) in CVD Patients and CG Individuals

3.2.1. General Knowledge Score About COVID-19 and Associated Factors in CVD Patients vs. CG Individuals

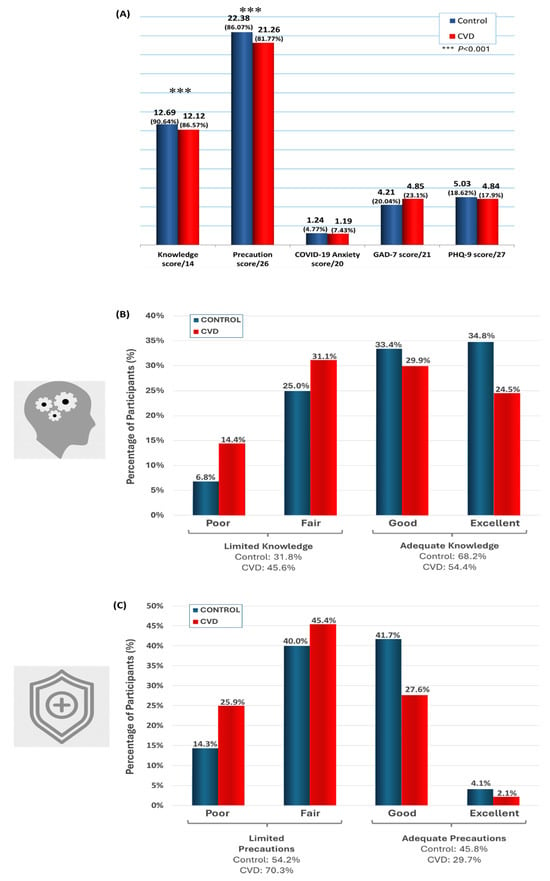

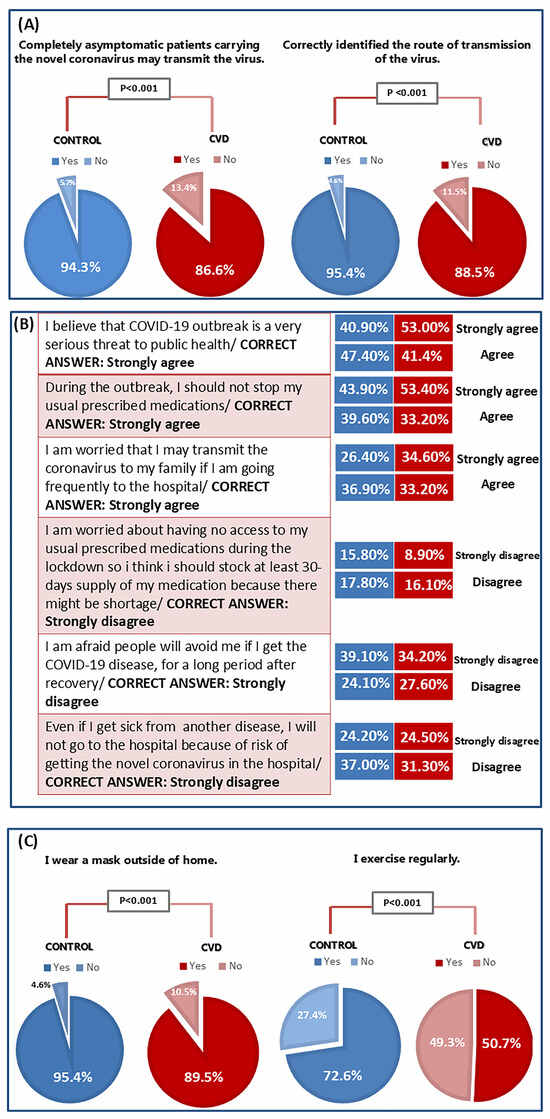

The mean knowledge score of CVD patients was significantly lower than that of the CG subjects (12.1 ± 2.1/14 (86.4%) vs. 12.6 ± 1.6/14 (90.0%), p < 0.001, respectively) (Figure 1A). Almost half of the CVD patients (45.7% regrouping, 14.4% with Poor, and 31.3% with Fair knowledge scores) versus a third of CG subjects who had a “Limited” Knowledge level about COVID-19 (Figure 1B). For instance, CVD patients, when compared to CG subjects, less frequently correctly identified that asymptomatic patients carrying the virus may transmit the virus (86.6% vs. 94.3%, p < 0.001, respectively) (Figure 2A). The complete set of knowledge-related questions and the distribution of correct/incorrect responses for both groups are presented in the Supplementary Materials, Table S1. The bivariate analysis is shown in the Supplementary Materials, Table S2. The multivariate analysis showed that CVD patients knew more about COVID-19 when they were of a younger age (p = 0.001), male gender (p = 0.02), higher educational level (p < 0.001), and when they had a higher precaution score toward COVID-19 and a better specific knowledge about COVID-19 related to their disease (p < 0.001) (Supplementary Materials, Table S3).

Figure 1.

(A) CVD patients’ and control subjects’ average scores of COVID-19 knowledge, precaution, and anxiety (CAS), as well as scores of GAD-7 and PHQ-9, according to the Mann–Whitney test, in comparison with control subjects. CAS: Coronavirus Anxiety Score; GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9. CVD: cardiovascular disease. *** p < 0.001 with p < 0.05 was considered significant. (B) Percentage (%) of CVD patients versus control subjects with COVID-19 knowledge scores categorized into Poor (≤10 /14 so ≤71.4%), Fair (11/14 = 78.5% and 12/14 = 85.7%), Good (13/14 = 92.8%), and Excellent (14/14 = 100%). Almost half of the CVD patients (45.7% regrouping, 14.4% with Poor, and 31.3% with Fair knowledge scores) versus a third of CG subjects (31.8% regrouping, 6.8% with Poor, and 25.0% with Fair knowledge scores) had a “Limited” knowledge level about COVID-19. The remaining subjects (CVD: 54.4% vs. CG: 68.2%) had an ‘’Adequate” knowledge level about COVID-19 (Good and Excellent knowledge scores). (C) Percentage (%) of CVD patients versus control subjects with COVID-19 precaution scores categorized into Poor (≤19/26 so ≤73.0%), Fair (between 20/26 = 76.9% and 23/26= 84.4%), Good (between 24/26 = 92.3% and 25/26 = 96.1%), and Excellent (26/26 = 100%). Almost three-fourths of the CVD patients (70.3% regrouping, 24.9% with Poor, and 45.4% with Fair precaution scores) versus half of CG subjects (54.2% regrouping, 14.3% with Poor, and 39.9% with Fair precaution scores) had a “Limited” precaution level about COVID-19. The remaining subjects (CVD: 29.7% vs. CG: 45.8%) had an ‘’Adequate” precaution level about COVID-19 (Good and Excellent precaution scores). Categories of “Poor” and “Fair” scores = “Limited knowledge” or “Limited precautions” about COVID-19; categories of “Good” and “Excellent” scores = “Adequate knowledge” or “Adequate precautions” about COVID-19.

Figure 2.

Distribution of (A) answers related to knowledge, (B) correct answers related to risk perception (Blue: Control; Red: CVD), and (C) answers related to precautionary measures concerning COVID-19 in patients with CVD versus CG subjects. The full set of knowledge/perception/precaution questions and response distributions are provided in the Supplementary Materials, Tables S1, S4, and S5, respectively. The chi square test was performed with p < 0.05 is statistically significant. CG: control group. CVD: cardiovascular disease.

3.2.2. General Risk Perception Toward COVID-19 and Associated Factors in CVD Patients vs. CG Individuals

CVD patients showed a poor-to-moderate general perception about COVID-19 risk, with no significant difference from CG subjects (41.3% vs. 38.6% of correct answers, respectively, p = 0.072). For instance, more than half of CVD patients, when compared to CG participants, correctly and better recognized that they should not stop their usual prescribed medication during the outbreak (p = 0.002). Very few patients correctly perceived, compared to CG subjects, that they should not worry about restricted access to their usual prescribed medications during the lockdown (p < 0.001) (8.9% vs. 15.8% of correct answers, respectively) (Figure 2B). The complete set of perception-related questions and the distribution of correct/incorrect responses for both groups are presented in the Supplementary Materials, Table S4.

3.2.3. General Precaution Score Against COVID-19 and Associated Factors in CVD Patients vs. CG Individuals

The mean precaution score of CVD patients was significantly lower than that of the CG subjects (21.2 ± 3.4 /26 (81.5%) vs. 22.3 ± 3.0/26 (85.7%), p < 0.001, respectively) (Figure 1A). Almost three-fourths of the CVD patients versus half of the CG subjects had a “Limited” precaution level towards COVID-19 (Figure 1C). Specifically, CVD patients were less likely to exercise regularly (50.7% vs. 72.6%) and to wear a mask outside home (89.5% vs. 95.4%) compared to the CG subjects (all p < 0.001) (Figure 2C). The complete set of precaution-related questions and the distribution of correct/incorrect responses for both groups are presented in the Supplementary Materials, Table S5. The bivariate analysis is shown in the Supplementary Materials, Table S2. The multivariate analysis revealed that CVD patients took more precautionary measures toward COVID-19 when they had a better socioeconomic status (p = 0.013), a higher educational level (p = 0.040), better knowledge about COVID-19 (p < 0.001), and better specific knowledge about COVID-19 in CVD patients (p < 0.001) (Supplementary Materials, Table S3).

3.2.4. Coronavirus Anxiety Scale (CAS) and Associated Factors in CVD Patients vs. CG Individuals

The mean CAS score of CVD patients was higher than that of CG subjects (1.1 ± 2.2 over 20 vs. 1.2 ± 2.3 over 20, respectively), but these means had no clinical relevance, and their differences were not statistically significant (Figure 1A). The bivariate analysis is shown in the Supplementary Materials, Table S2. The multivariate analysis revealed that CVD patients were more anxious towards COVID-19 when they had increased their alcohol consumption since the start of the outbreak (p = 0.04) and had higher GAD7 and PHQ9 scores (both p < 0.001) (Supplementary Materials, Table S3).

3.2.5. GAD-7 Score and Associated Factors in CVD Patients vs. CG Individuals

The CVD group achieved higher mean GAD-7 scores in comparison to the CG GAD-7 scores (4.7 ± 4.5/21 and 4.2 ± 4.3/21, respectively), but these means had no clinical relevance, and their differences were not statistically significant (Figure 1A). A proportion of 13.4% of CVD patients versus 9.49% of CG subjects had a clinically relevant GAD-7 score (≥10) without being diagnosed with anxiety by their physician. The bivariate analysis is shown in the Supplementary Materials, Table S2. The multivariate analysis showed that CVD patients had a significantly higher GAD-7 score when they were living outside of Beirut (p = 0.032), had a higher CAS score (p < 0.001), and had a higher PHQ-9 score (p < 0.001) (Supplementary Materials, Table S3).

3.2.6. PHQ-9 Score and Associated Factors in CVD Patients vs. CG Individuals

The mean PHQ-9 scores of CVD patients and the CG subjects were 4.84/27 (17.9%) and 5.03/27 (18.62%), respectively. The difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (Figure 1A). We found that 11.3% of CVD patients versus 16.46% of CG subjects had a clinically relevant PHQ-9 score (≥10) without being diagnosed with depression by their physician. The bivariate analysis is shown in the Supplementary Materials, Table S2. The multivariate analysis demonstrated that CVD patients had a higher PHQ-9 score when they had a higher GAD-7 score (p < 0.001) and were younger (p = 0.001) (Supplementary Materials, Table S3).

3.3. Specific Parameters (Knowledge, Precautions, and Perception About COVID-19) in CVD Patients

This section was filled according to the third part of the questionnaire, completed only by CVD patients answering questions about COVID-19 that were particularly related to their disease.

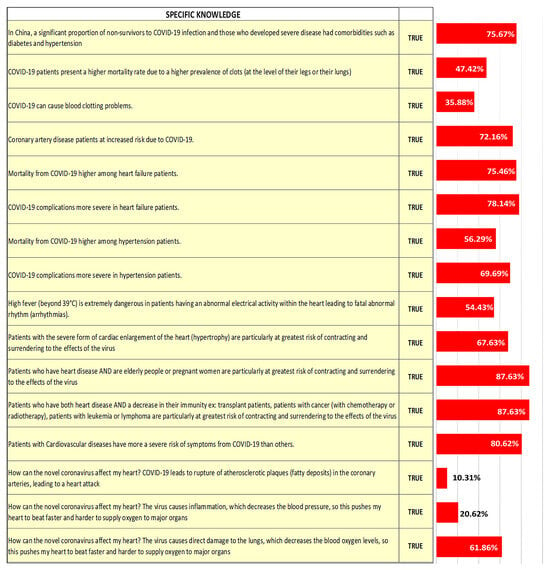

3.3.1. Specific Knowledge

The mean specific knowledge score was 9.41 ± 3.77 over 14 (67.2%) for CVD patients, with 16.1% having Good and 8.9% having Excellent specific knowledge scores about COVID-19 in relation to their disease. For instance, CVD patients correctly identified that they had a higher risk of severe symptoms from COVID-19 than other individuals. However, only 35.88% knew that COVID-19 could cause blood clotting issues. Overall, the average of correct answers to questions related to specific knowledge was 61.34% (Figure 3). The bivariate analysis is shown in the Supplementary Materials, Table S2. The multivariate analysis showed that better knowledge and preventive measures positively influenced in CVD patients the specific knowledge about COVID-19 in relation to their disease (Supplementary Materials, Table S3).

Figure 3.

Frequency (%) of correct answers to specific knowledge questions concerning COVID-19 in CVD patients. CVD: cardiovascular disease.

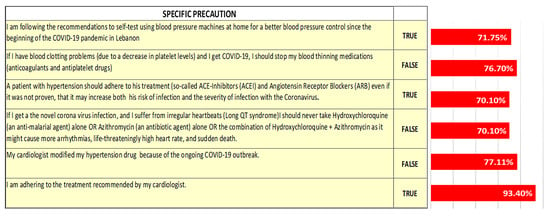

3.3.2. Specific Precautions

A proportion of 93.40% of CVD patients adhered to the treatment recommended by their cardiologist. Only 32.99% of CVD patients knew that if they contracted COVID-19 while they suffered from irregular heartbeats (e.g., Long QT syndrome), they should never take hydroxychloroquine and/or azithromycin. Overall, the average of correct answers regarding questions about specific precautions was 70.34% (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Frequency (%) of correct answers to specific precautionary measures questions concerning COVID-19 in CVD patients. CVD: cardiovascular disease.

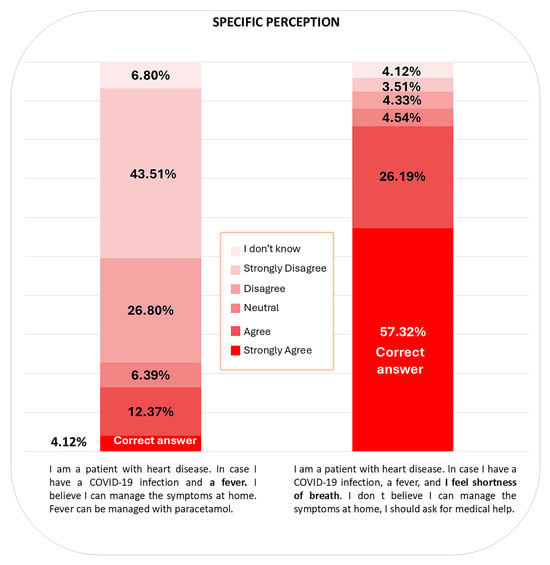

3.3.3. Specific Perception

Only 4.12% of CVD patients correctly believed that in case they had a COVID-19 infection and a fever, they could manage the symptoms at home, since fever can be treated with paracetamol. In addition, 57.32% of patients correctly responded that in case they had a COVID-19 infection and a fever with shortness of breath, they should ask for medical help instead of managing their symptoms at home. Accordingly, the average of correct answers regarding specific risk perception questions was 30.72% (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Frequency (%) of answers to specific perception questions concerning COVID-19 in CVD patients. CVD: cardiovascular disease.

4. Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we evaluated the perspective of CVD patients in Lebanon towards COVID-19, as it has been shown that improving knowledge, risk perception, and preventive practices helps in preventing the spread of the disease and in managing symptoms of anxiety and depression during this pandemic [47]. A total of 1518 individuals participated in this survey, of which 31.9% had CVD, with the most common primary diagnosis being hypertension.

4.1. COVID-19 Knowledge

CVD patients had a reasonably fair general knowledge about COVID-19, as a few gaps existed when compared to CG subjects. More importantly, CVD patients scored poorly on specific knowledge questions related to their disease. Similar studies in the United States [18], Ethiopia [19,39], India [48], and Vietnam [47] reported a relative lack of knowledge about COVID-19 in patients with chronic diseases, including patients with heart diseases and hypertension. Some of our patients, similarly to others [19,46], failed to recognize that COVID-19 complications and death were more severe and frequent, respectively, in hypertensive patients infected with COVID-19, hence the role of the treating physician in providing better guidance and education on CVD and COVID-19. In addition, our findings, in line with others [19,39,46,48], showed that patients with a higher educational level and younger participants (healthy or suffering from a disease) were more knowledgeable about COVID-19. Moreover, males and especially those suffering from CVD demonstrated a higher knowledge level about COVID-19 than females. As the majority of patients who contracted the virus were males [49], this might explain why they would seek more information on COVID-19. Furthermore, our study demonstrated that knowledge about COVID-19 was a significant predictor of COVID-19-preventive behavior, as previously reported by others [48]. Therefore, great preventive practices toward COVID-19 can be achieved with adequate knowledge of preventive measures [24]. The poor specific knowledge among CVD patients also reflects suboptimal physician–patient communication. Previous studies have highlighted how the COVID-19 context disrupted doctor–patient communication and trust, as infection control measures created barriers in face-to-face interactions [50]. To address this challenge, ensuring clear and empathetic communication is essential, particularly for patients with chronic conditions, in order to maintain adherence to precautionary measures and treatment during the pandemic. Incorporating brief but structured counseling sessions on infection risks and comorbidity-specific vulnerabilities during outpatient visits may bridge this knowledge gap [45].

4.2. COVID-19 Risk Perception

Moreover, CVD patients disclosed high averages of wrong answers regarding COVID-19 general and specific risk perception questions. Indeed, only half of our CVD patients perceived this outbreak as a serious public health threat, which was quite in line with what other chronic disease patients (including patients with hypertension) perceived to be at high risk if infected by COVID-19 from Ethiopia (68%) [25] and from Portugal (51.6%) [29]. Only one-third of our patients worried that their family or household members would contract the virus, which was inconsistent with others’ findings from Vietnam (64.8%) [47]. More importantly, only half of our patients perceived the need to pursue their usual prescribed medication, and a quarter of them admitted to avoiding hospitals for fear of contracting the virus. These findings were in line with previously published data [30].

4.3. COVID-19-Preventive Practices

Furthermore, CVD patients adopted relatively fair preventive measures about COVID-19, as several gaps in the general preventive measures were revealed when compared to CG subjects. Most patients had a “Limited” general precautions level towards COVID-19. In line with these findings, chronic disease patients reported poor practice [19,39] as well as a decline in physical activity during the pandemic [51], in contrast to others with 98.3% adherence to face masks and an overall 77.2% good precautionary measures against COVID-19 [47]. A higher educational level and socioeconomic status in our patients correlated with a better specific knowledge about COVID-19 related to their disease. More importantly, many of our patients responded with wrong answers to the specific precautionary measures about COVID-19 in relation to their disease, with several ones who did not follow the recommendations to self-test using blood pressure machines at home for better controlling their blood pressure. Undoubtedly, the pandemic has favored remote consultation and monitoring through the use of mobile-health tools and wearables [52]. Adoption of telemedicine has become an essential step in CVD management [52]. In addition, many patients reported not adhering to their antihypertensive treatments (such as ACEI /ARB), which were initially thought to increase the risk of infection with COVID-19 [4,12] In the USA, one in eight Americans with CVD missed or delayed taking medication due to costs [53]. More drastically, in Lebanon, diminished purchasing power due to one of the worst economic crises in history, conjugated with the pandemic, has critically impeded access and adherence to medications for citizens and particularly for CVD patients.

4.4. COVID-19 Psychological Impact

Regarding the psychological impact of COVID-19 on our population, our study revealed that CVD patients and CG individuals did not show clinically relevant anxiety and depression scores. Similarly to Louvardi et al. [26], overall levels of anxiety and depression in our CVD patients and CG subjects had no clinical significance. As a matter of fact, the lack of any clinical relevance in these three scores (CAS, GAD-7, and PHQ-9) among our patients may be attributable to many possibilities: (1) The initial success of Lebanon in containing the virus and the limited number of cases and deaths among the Lebanese population at that time (May 2020) [54]. (2) CVD patients had incomplete perception of their risk of severe COVID-19, as shown in our findings and others’ [31]. Patients may have also adopted a coping strategy to deny or minimize stressors, as reported by others [31,55]. In particular, the same coping mechanism may be applied to the Lebanese general population to mitigate the disastrous period that the country is going through (unprecedented economic crisis, the August 2020 Beirut blast, etc.). That same “safety behavior” amongst individuals with high-risk diseases during the pandemic was also suggested by Kohler et al. [56]. (3) In Lebanon, anxiety and depression are still considered taboo topics to many, and some patients may avoid reaching out to their physicians to share their fears and distresses and particularly with our volunteers. Nonetheless, when classes of PHQ-9 and GAD-7 tests were closely examined, our findings revealed clinically relevant scores on both tests, with surprising rates of anxiety and depression that were not previously diagnosed by their physicians in both CG subjects and CVD patients. In particular, patients living outside of the capital Beirut had higher anxiety levels, as reported by others [27]. Younger patients manifested a higher PHQ-9 score, possibly due to isolation and limited access to healthcare, support groups, and services. Certainly, the pandemic and all its ensuing consequences, from infection, isolation, lockdowns, social distancing, working from home, and even post-COVID-19 syndrome [28], may have increased the risk of developing depression and other mental health disorders.

4.5. Limitations

This study had several limitations, mainly related to the method of data collection. The survey was made available online and was self-filled; this may have led to reporting, selection, sampling, and volunteer biases [46]. However, to reduce those biases, our team was carefully selected and well trained to address around 82% of the total number of participants (healthy individuals and our CVD patients) over face-to-face or phone interviews. Indeed, participants were randomly selected among the family, friends, and hospitalized patients. This prevented those feeling more engaged or knowledgeable about the topic to complete the survey. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that participant selection itself is a key factor that may have influenced the study outcomes, particularly given the diversity of healthcare access and sociodemographic backgrounds across Lebanon. On the other hand, direct interviews with participants, whether by phone or in-person, may have also led to a social desirability bias. A key limitation of this study is the sampling bias resulting from the demographic imbalance between the case and control groups, particularly in terms of age and gender distribution (Table 2). Patients with cardiovascular diseases are naturally older, while the control group represented a relatively younger segment of the general population. Although such differences could in principle be addressed through weighing procedures (ponderation) or by constructing matched groups, this was not the aim of our study. Our intention was to capture the perspectives of CVD patients as a high-risk population and compare them to the general Lebanese population, whose preparedness is also of public health importance. Preserving this natural demographic difference allowed us to assess vulnerabilities in older CVD patients while simultaneously identifying gaps in knowledge and behaviors among the younger general population. Nonetheless, we recognize that the absence of weighing or matching procedures could introduce bias, and this must be considered when interpreting our findings. In addition, the Likert scale used in evaluating the perception toward COVID-19 may have caused a central tendency bias, where extreme answers (e.g., strongly disagree and strongly agree that these are the correct answers) are avoided. Furthermore, due to lack of Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency, the scores of general perception as well as specific perception and specific precaution were not computed. To assess general perception, we calculated the average number of correct responses to perception-related questions for both CVD patients and control group (CG) participants. A bivariate analysis using the Mann–Whitney test was then performed to compare Likert-scale scores between the two groups. For specific perception and precaution parameters, we calculated the average number of correct responses among CVD patients regarding COVID-19 in relation to their cardiovascular condition. Finally, we failed to conduct matching and propensity scores, which might limit the generalizability of our findings.

4.6. Perspectives and Recommendations

The results of our study indicate that during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Lebanon, individuals with or without CVD experienced changes in certain lifestyle and behavioral patterns, including tobacco use, work arrangements, shopping responsibilities, and alcohol consumption. These findings underscore the importance of targeted public health strategies to address and mitigate the long-term impact of such behavioral shifts during future health crises. As assessing and improving the population’s perspective remain essential in fighting pandemics, priority should be given to older patients, females, individuals with low educational and socioeconomic status, and people living in underserved areas.

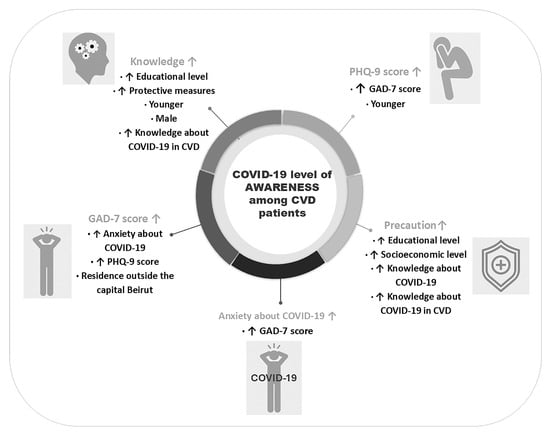

Despite reasonably fair levels of knowledge, perception, and precaution, a perfect score of 100% is required in all these parameters, since a single gap in knowledge about COVID-19 or a single flawed precautionary measure may put the individual at risk of contracting COVID-19. Meanwhile, although COVID-19 vaccines have been widely delivered worldwide, adopting the typical preventive measures (masks, social distancing, and strict hand hygiene) remains necessary. Therefore, protection is incomplete without better knowledge about the disease, responsible preventive measures, and improved risk perception. Finally, we must orient our attention to the psychological burden of this and future pandemics by encouraging patient–physician communication to mitigate any arising psychological and emotional distress, especially in vulnerable populations. The list of key points is summarized in Table 3 and Figure 6.

Table 3.

Caring for patients with CVD during COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 6.

Major factors affecting COVID-19 level of awareness among patients with CVD (knowledge, precaution, COVID-19 anxiety, GAD-7 (anxiety), and PHQ-9 (depression) scores). CVD: cardiovascular disease; GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9. An upward-pointing arrow indicates an increase.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings suggest that a significant proportion of our CVD population had limited knowledge, perception, and practices about COVID-19. Due to the high predisposition of this population to an increased risk of complications due to COVID-19, organizing and prioritizing care for patients with CVD is of paramount importance. Thus, the perspective of CVD patients must be taken into consideration to guide future pandemic responses, and recommendations inferred from the present investigation represent a blueprint for implementing awareness campaigns to establish proper knowledge, perception, and precautionary measures along with psychological and emotional support for this vulnerable population.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/covid5090155/s1. Figure S1. (A) Chart representing the diagnoses of CVD patients by their doctor; (B) Clinical characteristics of patients with CVD. (C) Bar chart representing the medications taken by CVD patients; ACE: Angiotensin Converting Enzyme; BP: Blood Pressure; HTN: Hypertension. CVD: Cardiovascular Disease. Table S1: General Knowledge-Related Questions on COVID-19 and Distribution of Correct/Incorrect Responses Among CVD Patients and Control Participants. Table S2: Bivariate analysis of the general characteristics affecting the scores of COVID-19 knowledge, precaution, specific perception, and anxiety (CAS) as well as general anxiety (GAD-7) and depression (PHQ-9) in CVD patients: p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. BMI: Body Mass Index; CAS: Coronavirus Anxiety Score, GAD-7: General Anxiety Disorder-7, PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9. CVD: Cardiovascular Disease. Table S3: Multivariate analysis with Linear regression analysis of COVID-19 Knowledge, specific Perception, Precaution, and Anxiety scores, as well as GAD-7, and PHQ-9 scores in CVD patients. B: beta; Std. Error: Standard Error; t: t-test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. CAS: Coronavirus Anxiety Score, GAD-7: General Anxiety Disorder-7, PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9. CVD: Cardiovascular Disease. Table S4: General Perception-Related Questions on COVID-19 and Distribution of Correct/Incorrect Responses Among CVD Patients and Control Participants. Table S5: General Precaution-Related Questions on COVID-19 and Distribution of Correct/Incorrect Responses Among CVD Patients and Control Participants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.N., E.C., R.A., N.Y. and M.N.C.; Data curation, M.M., B.F., K.F., J.H., Y.R., P.G., D.C.A., A.Z., J.G.L., L.O., A.H., H.C., M.G., M.S. and M.N.C.; Formal analysis, B.A.; Investigation, M.M., B.F., K.F., J.H., Y.R., P.G., D.C.A., A.Z., J.G.L., L.O., A.H., H.C., M.G. and M.S.; Methodology, M.M., B.F., K.F., J.H., Y.R., P.G., D.C.A., A.Z., J.G.L., L.O., A.H., H.C., M.G., M.S., B.A., W.N., E.C., R.A., N.Y. and M.N.C.; Project administration, M.N.C.; Software, B.F. and B.A.; Supervision, W.N., E.C., R.A., N.Y. and M.N.C.; Validation, B.A.; Visualization, M.M., B.F., K.F. and M.N.C.; Writing—original draft, M.M., B.F., K.F. and J.H.; Writing—review and editing, W.N., E.C., R.A., N.Y. and M.N.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

There has been no financial support for this work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

An IRB waiver was obtained from the ethical committee of Al-Hayat hospital (number: ETC-13-2020; 23 April 2020). Our survey was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice ICH Section 3 and the principles laid down by the 18th World Medical Assembly (Helsinki, 1964) and all applicable amendments. To ensure anonymity, the survey did not require the names, phone numbers, emails, and exact date of birth (only age was provided) of the participants. All participants were provided with a designated code. Electronic records were safely stored, and access to the sheets was limited to the researchers.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants (18 years of age and older) across Lebanon have signed informed consent and accepted to fill the online survey form by choosing “yes, I agree to participate” or with the help of medical staff.

Data Availability Statement

The questionnaire is available in the Supplementary Materials. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for every healthy subject or patient with cardiovascular diseases who participated in our study, and we wish full recovery to all patients worldwide fighting COVID-19. We are mostly grateful for dispensaries who provided us with their list of patients to include in our study, notably Srebta Health Center and Armenian Relief Cross Lebanon Center. We thank the contribution of our undergraduate students from the Lebanese University, at the faculty of Medical Sciences and faculty of Public Health (section II), who assisted the participants to fill out the questionnaire: Aalaa Saleh, Ahmad Issawi, Ahmad El-Lakis, Ali Hamdan, Amira El Khouwayer, Atifa Kamaleddine, Carine Mina, Diana Abou Ltaif, Diana Bashashi, Dima Al Saddik, Dina Essayli, Elissa Abi Fadel, Elissa El Toum, Ennio Charchar, Emmanuel Eid, Fatima Farhat, Gaelle Ghazal, Hadi Meslem, Hadi Shammaa, Hiba El Dinnawi, Jana Ghamraoui, Joelle Kalaji, Joseph Mouawad, Karim Kheir, Maha Trad, Manar Osman, Mariane Bou Zeidan, Michel Boueiz, Mohamad Al Hajjar, Mohammad Kazzaz, Mohamad Naboulsi, Mohammad Srour, Moussa Hojeij, Mustafa Saleh, Nadia Sabbagh, Nicolas Sandakly, Ogarite Kattan, Olga Mcheileh, Omar Al Khatib, Oussama Ouzeir, Rania Makki, Raoul Al Kassis, Rawane Abdul Razzak, Rim Chehab, Rim Araoui, Rimla Abboud, Rita Chebl, Salim Yakdane, Samir Mitri, Sana Tantawi, Sawsane Ghaddar, Solay Farhat, Sondos Naous, Tia El Kazzi, Victoria Chidiac, Wafaa Bzeih, Walaa Meouch, Yara Tarhini, Yousra Antar, Yves Ghattas Damoun, Zainab Hammoud, and Zeina Ajram.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACE2 | Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 |

| ARB | Angiotensin Receptor Blocker |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CAS | Coronavirus Anxiety Scale |

| CG | Control Group |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Diseases |

| GAD-7 | Generalized Anxiety Disorder questionnaire |

| PHQ-9 | Patient Health Questionnaire |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Appendix A

| Questionnaire |

| Section 1—General Questions |

| A—General Characteristics of all participants |

|

| B—General Knowledge about COVID-19 |

| The following are questions about your knowledge level on novel coronavirus. Please select the answer of your choice. |

|

| C—Perception of COVID 19 |

|

| D—Prevention from COVID-19 |

|

| E—Anxiety and depression level during COVID-19 outbreak |

| E1/Coronavirus Anxiety (5 Questions): |

| How often have you experienced the following since the beginning of the outbreak in Lebanon? |

|

| E2/Anxiety Questionnaire (7 Questions): (GAD-7) |

| What best describes you since the beginning of the outbreak in Lebanon? |

|

| E3/Depression Questionnaire (PHQ-9) |

| Since the beginning of the outbreak in Lebanon, how often have you been bothered by the following? |

|

| Section 2—Cardiovascular Diseases Questions |

|

| For questions 2 and 3, please write your blood pressure which equals SBP/DBP. |

|

|

| Section 1—Continued: Other Chronic diseases |

|

References

- World Health Organization. Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Situation Report 51. 11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200311-sitrep-51-covid-19.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard Global Summary. 2025. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/summary (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Napoli, C.; Tritto, I.; Benincasa, G.; Mansueto, G.; Ambrosio, G. Cardiovascular Involvement during COVID-19 and Clinical Implications in Elderly Patients: A Review. Ann. Med. Surg. 2020, 57, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicin, L.; Abplanalp, W.T.; Mellentin, H.; Kattih, B.; Tombor, L.; John, D.; Schmitto, J.D.; Heineke, J.; Emrich, F.; Arsalan, M.; et al. Cell Type-Specific Expression of the Putative SARS-CoV-2 Receptor ACE2 in Human Hearts. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 1804–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Hassan, F.F.; Bou Hamdan, M.; Ali, F.; Melhem, N.M. Response to COVID-19 in Lebanon: Update, Challenges and Lessons Learned. Epidemiol. Infect. 2023, 151, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiga, M.; Wang, D.W.; Han, Y.; Lewis, D.B.; Wu, J.C. COVID-19 and Cardiovascular Disease: From Basic Mechanisms to Clinical Perspectives. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Hu, B.; Hu, C.; Zhu, F.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, B.; Xiang, H.; Cheng, Z.; Xiong, Y.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients with 2019 Novel Coronavirus–Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020, 323, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, B.A.; Metaxaki, M.; Sithole, N.; Landín, P.; Martín, P.; Salinas-Botrán, A. Cardiovascular Disease and COVID-19: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puntmann, V.O.; Carerj, M.L.; Wieters, I.; Fahim, M.; Arendt, C.; Hoffmann, J.; Shchendrygina, A.; Escher, F.; Vasa-Nicotera, M.; Zeiher, A.M.; et al. Outcomes of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients Recently Recovered from Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 1265–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Xu, E.; Bowe, B.; Al-Aly, Z. Long-term Cardiovascular Outcomes of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaduganathan, M.; Vardeny, O.; Michel, T.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Solomon, S.D. Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System Inhibitors in Patients with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1653–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Society of Cardiology. Position Statement of the ESC Council on Hypertension on ACE Inhibitors and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers. 2020. Available online: https://www.escardio.org/Councils/Council-on-Hypertension-(CHT)/News/position-statement-of-the-esc-council-on-hypertension-on-ace-inhibitors-and-ang (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Siddiquea, B.N.; Shetty, A.; Bhattacharya, O.; Afroz, A.; Billah, B. Global Epidemiology of COVID-19 Knowledge, Attitude and Practice: A Systematic Review and Meta Analysis. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e051447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olum, R.; Chekwech, G.; Wekha, G.; Nassozi, D.R.; Bongomin, F. Coronavirus Disease 2019: Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices of Health Care Workers at Makerere University Teaching Hospitals, Uganda. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, M.Z.; Islam, M.S.; Sikder, M.T.; Mosaddek, A.S.M.; Zegarra-Valdivia, J.A.; Gozal, D. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Regarding COVID-19 Outbreak in Bangladesh: An Online-Based Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, D.C.; Zaiter, A.; Ghiya, P.; Zaiter, K.; Louka, J.G.; Fakih, C.; Chahine, M.N. COVID-19: Pregnant Women’s Knowledge, Perceptions & Fears. First National Data from Lebanon. Obstet. Gynecol. Res. 2020, 3, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saryeddine, R.; Ajrouch, Z.; El Ahmar, M.; Lahoud, N.; Ajrouche, R. Parents’ Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices towards COVID-19 in Children: A Lebanese Cross-Sectional Study. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63, E497–E512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.S.; Serper, M.; Opsasnick, L.; O’Conor, R.M.; Curtis, L.; Benavente, J.Y.; Wismer, G.; Batio, S.; Eifler, M.; Zheng, P.; et al. Awareness, Attitudes, and Actions Related to COVID-19 Among Adults with Chronic Conditions at the Onset of the U.S. Outbreak: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akalu, Y.; Ayelign, B.; Molla, M.D. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Towards COVID-19 Among Chronic Disease Patients at Addis Zemen Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 1949–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, L.; Hallit, S.; Sacre, H.; Salameh, P. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices towards COVID-19: A Cross Sectional Study in Lebanon. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halawi, A.; Ghazal, M.; Cherry, H.; Abi Hanna, P.; Chahine, M.N. Knowledge, Perception and Precautions of the Lebanese Population Regarding the Novel Coronavirus Outbreak: A Cross-Sectional Study between 18 and 22 March 2020. J. Public Health Dis. 2020, 3, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacre, H.; Hallit, S.; Hajj, A.; Zeenny, R.M.; Salameh, P. Knowledge, Attitude, Practice, and Perceived Barriers among Community Pharmacists in Lebanon. Pharm. Pract. 2020, 18, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machaalani, M.; Fakhry, B.; Zwaideh, M.; Mendelek, K.; Mahmoud, N.; Hammoud, T.; Chahine, M.N. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Toward Cardiovascular Diseases in the Lebanese Population. Glob. Heart 2022, 17, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, D.; Tripathy, S.; Kar, S.K.; Sharma, N.; Verma, S.K.; Kaushal, V. Study of Knowledge, Attitude, Anxiety and Perceived Mental Healthcare Need in Indian Population During COVID-19 Pandemic. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 51, 102083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melesie Taye, G.; Bose, L.; Beressa, T.B.; Tefera, G.M.; Mosisa, B.; Dinsa, H.; Birhanu, A.; Umeta, G. COVID-19 Knowledge, Attitudes, and Prevention Practices Among People with Hypertension and Diabetes Mellitus Attending Public Health Facilities in Ambo, Ethiopia. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 4203–4214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louvardi, M.; Pelekasis, P.; Chrousos, G.P.; Darviri, C. Mental Health in Chronic Disease Patients During the COVID-19 Quarantine in Greece. Palliat. Support Care 2020, 18, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szlenk-Czyczerska, E.; Guzek, M.; Bielska, D.E.; Ławnik, A.; Polański, P.; Kurpas, D. Factors Differentiating Rural and Urban Population in Determining Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Chronic Cardiovascular Disease: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giurgi-Oncu, C.; Tudoran, C.; Pop, G.N.; Bredicean, C.; Pescariu, S.A.; Giurgiuca, A.; Tudoran, M. Cardiovascular Abnormalities and Mental Health Difficulties Result in a Reduced Quality of Life in the Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laires, P.A.; Dias, S.; Gama, A.; Moniz, M.; Pedro, A.R.; Soares, P.; Aguiar, P.; Nunes, C. The Association Between Chronic Disease and Serious COVID-19 Outcomes and Its Influence on Risk Perception: Survey Study and Database Analysis. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021, 7, e22794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Kaushik, A.; Johnson, L.; Jaganathan, S.; Jarhyan, P.; Deepa, M.; Kong, S.; Venkateshmurthy, N.S.; Kondal, D.; Mohan, S.; et al. Patient Experiences and Perceptions of Chronic Disease Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic in India: A Qualitative Study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e048926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.T.; Ravaud, P. COVID-19-Related Perceptions, Context and Attitudes of Adults with Chronic Conditions: Results from a Cross-Sectional Survey Nested in the ComPaRe e-Cohort. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, L.; Barrett-Connor, E.; Wenger, N.K. Sex/Gender Differences in Cardiovascular Disease Prevention: What a Difference a Decade Makes. Circulation 2011, 124, 2145–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Kim, L.; Whitaker, M.; O’Halloran, A.; Cummings, C.; Holstein, R.; Prill, M.; Chai, S.J.; Kirley, P.D.; Alden, N.B.; et al. Hospitalization Rates and Characteristics of Patients Hospitalized with Laboratory-Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019—COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1–30, 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Xu, S.; Yu, M.; Wang, K.; Tao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhou, M.; Wu, B.; Yang, Z.; et al. Risk Factors for Severity and Mortality in Adult COVID-19 Inpatients in Wuhan. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 146, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a Brief Depression Severity Measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.A. Coronavirus Anxiety Scale: A Brief Mental Health Screener for COVID-19 Related Anxiety. Death Stud. 2020, 44, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikdeli, B.; Madhavan, M.V.; Jimenez, D.; Chuich, T.; Dreyfus, I.; Driggin, E.; Nigoghossian, C.D.; Ageno, W.; Madjid, M.; Guo, Y.; et al. COVID-19 and Thrombotic or Thromboembolic Disease: Implications for Prevention, Antithrombotic Therapy, and Follow-Up. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 2950–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Heart Association. Coronavirus Precautions for Patients and Others Facing Higher Risks. Available online: https://www.heart.org/en/coronavirus/coronavirus-covid-19-resources/coronavirus-precautions-for-patients-and-others-facing-higher-risks (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Addis, S.G.; Nega, A.D.; Miretu, D.G. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Patients with Chronic Diseases Towards COVID-19 Pandemic in Dessie Town Hospitals, Northeast Ethiopia. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2021, 15, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortin, M.-F.; Gagnon, J. Fondements et étapes du Processus de Recherche: Méthodes Quantitatives et Qualitatives, 2nd ed.; Chenelière Éducation: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moussi, C.; Tahan, L.; Habchy, P.; Kattan, O.; Njeim, A.; Abou Habib, L.; El Bitar, W.; El Asmar, B.; Chahine, M.N. School-Based Pre- and Post-Intervention Tests Assessing Knowledge about Healthy Lifestyles: A National School Health Awareness Campaign on Children Aged between 3 and 12 Years Old. Children 2024, 11, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chehab, R.; Abboud, R.; Bou Zeidan, M.; Eid, C.; Gerges, G.; Attieh, C.Z.; Btadini, S.; Kazma, D.O.; Bou Chahine El Chalouhi, S.M.; Abi Haidar, M.; et al. The Impact of a Randomized Community-Based Intervention on the Awareness of Women Residing in Lebanon Toward Breast Cancer, Cervical Cancer, and Intimate Hygiene. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, N.Y.; Fakhry, B.; Baddour, I.; Ismail, O.; Jamaleddine, Y.; Nohra, L.; Twainy, A.; Hassan, K.; Azzi, J.; Chahine, M.N. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Toward Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in the Lebanese Population. Cureus 2025, 17, e82024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machaalani, M.; Seifeddine, H.; Ali, A.; Bitar, H.; Briman, O.; Chahine, M.N. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Toward Hypertension Among Hypertensive Patients Residing in Lebanon. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2022, 18, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seid, M.A.; Hussen, M.S. Knowledge and attitude towards antimicrobial resistance among final year undergraduate paramedical students at University of Gondar, Ethiopia. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, G.; Nguyen, M.Q.; Tran, T.T.; Nguyen, V.T.; Nguyen, T.V.; Do, T.H.T.; Nguyen, P.H.; Phan, T.H.; Vu, T.T.; Nguyen, T.N. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices Regarding COVID-19 Among Chronic Illness Patients at Outpatient Departments in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 1571–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, V.; Dileepan, S.; Rustagi, N.; Mittal, A.; Patel, M.; Shafi, S.; Thirunavukkarasu, P.; Raghav, P. Health Literacy, Preventive COVID-19 Behaviour and Adherence to Chronic Disease Treatment During Lockdown Among Patients Registered at Primary Health Facility in Urban Jodhpur, Rajasthan. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2021, 15, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; An, Q.; Zhang, C.L.; He, L.; Wang, L. Decreased Low-Density Lipoprotein and the Presence of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Among Newly Diagnosed Drug-Naïve Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: D-Dimer as a Mediator. Exp. Ther. Med. 2022, 24, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopichandran, V.; Sakthivel, K. Doctor–Patient Communication and Trust in Doctors During COVID-19 Times—A Cross-Sectional Study in Chennai, India. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bakel, B.M.A.; Bakker, E.A.; de Vries, F.; Thijssen, D.H.J.; Eijsvogels, T.M.H. Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour in Dutch Cardiovascular Disease Patients. Neth. Heart J. 2021, 29, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowie, M.R.; Lam, C.S.P. Remote Monitoring and Digital Health Tools in CVD Management. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 457–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khera, A.; Baum, S.J.; Gluckman, T.J.; Gulati, M.; Martin, S.S.; Michos, E.D.; Navar, A.M.; Taub, P.R.; Toth, P.P.; Virani, S.S.; et al. Continuity of Care and Outpatient Management for Patients with and at High Risk for Cardiovascular Disease During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scientific Statement from the American Society for Preventive Cardiology. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020, 1, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, P.; Azar, E.; Hitti, E. COVID-19 Response in Lebanon: Current Experience and Challenges in a Low-Resource Setting. JAMA 2020, 324, 548–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.C.; Ting, S.A. Avoidance Denial Versus Optimistic Denial in Reaction to the Threat of Future Cardiovascular Disease. Health Educ. Behav. 2012, 39, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.; Schwenkel, L.; Koch, A.; Berberich, J.; Pauli, P.; Allgöwer, F. Robust and Optimal Predictive Control of the COVID-19 Outbreak. Annu. Rev. Control 2021, 51, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).