Abstract

We present the design and characterization of a fully automated free-standing liquid crystal (FSLC) film holder, enabling remote and precise control of liquid crystal (LC) volume release, wiping speed, and temperature. Using 4-octyl-4′-cyanobiphenyl (8CB) as a test material, we systematically investigated the influence of formation parameters on the resulting film thickness and temporal evolution. Thickness measurements performed by monitoring the difference in optical path lengths of two arms of a standard optical intensity autocorrelation setup reveal that the wiping speed is the dominant factor determining both the initial film thickness and the subsequent annealing dynamics, while temperature becomes relevant only at the highest wiping speeds. Faster wiping speeds consistently produce thinner and more uniform FSLC films on the order of 3 µm, due to reduced LC mass deposition. Time-resolved optical and X-ray scattering measurements confirm the presence of an annealing phase following film formation, which can last for between 1 s and 10 min time scales, until a stable smectic configuration is reached. The holder provides a reliable and fully remote tool for generating high-quality FSLC films at rates up to 1 Hz, suitable for optical to hard X-ray experiments where direct access to the sample environment is limited.

1. Introduction

Freely suspended liquid crystal (FSLC) films have served as versatile and accessible systems for exploring two-dimensional (2D) fluid mechanics and soft condensed matter physics since the late 1970s [1,2,3,4,5]. Because of the extended correlation lengths typical of liquid-crystalline mesophases, the influence of bounding surfaces remains significant even for films several tens of micrometers thick [6]. This makes FSLCs an ideal platform for investigating interfacial effects, elastic interactions, and topological dynamics in quasi-2D fluids.

Liquid crystals (LCs), as their name suggests, exhibit phases that are intermediate between conventional liquids and crystalline solids, with varying degrees of both orientational and positional order. In this work, we focus on thermotropic, rod-like LC systems in which temperature controls the sequence of mesophases. In the nematic phase, molecules exhibit orientational order without positional correlation, aligning on average along a common axis, known as the director. Upon cooling, rod-like LCs can transition into a smectic phase, where molecules form equidistant layers, adding one-dimensional positional order. In the smectic A (SmA) phase, the director is oriented perpendicular to the layers, which stack parallel to the film surface [4,7].

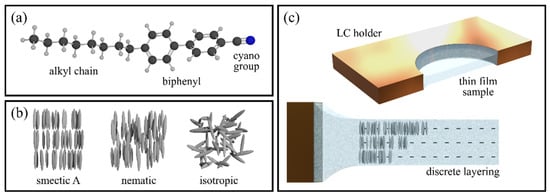

Among thermotropic compounds, 4-octyl-4′-cyanobiphenyl (8CB) is one of the most thoroughly studied, showing nematic and SmA phases near room temperature and readily forming FSLCs [7,8,9] (see Figure 1a,b). Its well-characterized structural and mechanical properties make it an ideal model material for testing controlled film formation methods.

FSLCs behave as highly stable, quasi-2D fluid membranes, with mechanical and hydrodynamic properties that have been extensively investigated [5,7,9]. They differ from soap films not only in robustness but also in their discrete layer structure, each film consisting of an integer number of smectic layers [7], as sketched in Figure 1c. Studies using X-ray scattering have revealed subtle structural variations between surface and interior layers [10], while others have identified first-order phase transitions between smectic A and smectic C phases [11]. Phenomena such as layer thinning, where smectic films reduce their thickness in discrete steps upon heating near the SmA–isotropic transition, have been observed particularly in partially fluorinated materials [12].

Edge dislocations, topological line defects defining thickness islands or holes, govern much of the film’s dynamics, with a characteristic line tension on the order of 10−7 dyn [9]. These films also host 2D topological defects (disclinations) that exhibit well-defined annihilation dynamics governed by hydrodynamic backflow coupling [5].

In practice, the preparation of uniform FSLC films requires careful control of the film thickness, temperature, and formation dynamics. Typically, a small LC droplet is spread across a rigid frame using a wiping mechanism, producing a thin suspended region connected to a thicker meniscus that acts as a reservoir [9,13,14]. The resulting film thickness is discrete and depends on the balance of surface tension, pressure difference, and flow conditions during formation [5,12].

With the advent of advanced radiation sources, from the infrared to X-rays and free-electron lasers (FELs), FSLCs have become particularly attractive as substrate-free, optically and structurally uniform targets. Their quasi-2D geometry enables direct probing of molecular ordering and collective dynamics without substrate interference [4,5]. However, experiments at FEL facilities often preclude manual film preparation due to restricted access and radiation hazards. This motivates the development of fully remote, automated systems for controlled FSLC formation and characterization.

In this work, we present the design and performance of a fully automated FSLC film holder, inspired by the linear-slide concept of Poole et al. [15,16], and capable of remote operation. Using 8CB as a benchmark material, we investigate how the released volume, temperature, and wiping speed influence the resulting film thickness, both statically and as a function of time during film formation. Finally, we demonstrate the applicability of this system in hard X-ray diffraction experiments, establishing a reproducible and adaptable platform for the study of FSLCs under extreme conditions.

Figure 1.

(a) 8CB molecular structure. (b) 8CB mesophase arrangement, where every ellipsoid is equivalent to a dimer in antiparallel configuration [17]. (c) SmA-FSLC film configuration and molecular alignment within the film.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. FSLC Film Holder

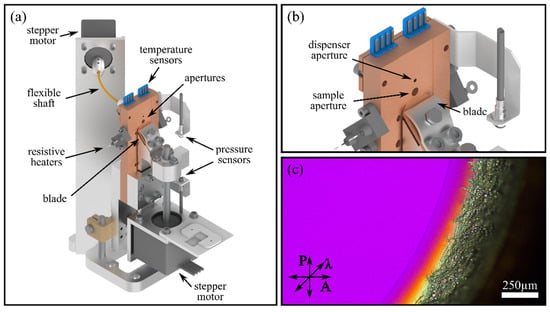

FSLC films need to be prepared, usually by sweeping a small amount of LC material over a framed aperture which has been prepared by ‘wetting’ it with sample material beforehand [5,13,15,18], very similarly to soap bubbles. In the holder presented here, the film is drawn by wiping a blade across a circular aperture as sketched in Figure 2a. Figure 2a,b, in fact, show the overall holder structure composed of a large copper block, equipped with a heating mechanism and a temperature sensor, which presents two circular apertures. The upper 1 mm hole has screw threads and is utilized as an LC reservoir. By rotating a screw forward, LC is displaced and pushed slowly out of the reservoir, which is sized to release ~10 µL at each 360° rotation of the inner screw. The second 3 mm hole is the place where the sample films are created, and features a 45° bevel extending into the sample holder block, helping to define the sample plane at the front surface of the device. The holder also features a copper blade, which is attached to a stepper motor that moves it over both apertures. The copper blade, in fact, moves over the dispenser hole and distributes LC material, which is attached to the blade edge and in between blade and frame, over the main hole, where the FSLC film forms as shown in the polarized microscope image in Figure 2c. The uniform magenta color in the center implies a uniform thickness and homeotropic alignment. A meniscus of varying thickness and alignment is also clearly visible, as expected. In this configuration, coherent and polarized light propagating normal to the sample plane, such as laser radiation, will experience only the ordinary axis of 8CB. The FSLC film forms preferentially where the radius of the beveled hole is smallest, at the front surface of the film holder, thanks to its surface tension, ensuring a repeatable film position over multiple film refreshments. After the film is formed, meaning the blade is no longer in contact with the LC over the aperture, the excess LC material and the overall alignment require a settling time before stability is reached, typically called ‘annealing’ time. With the holder presented here, multiple films can be redrawn at different speeds and frequencies, controlling temperature and LC volume fully remotely, resulting in various thicknesses and annealing times, which will be characterized in detail in the following paragraphs.

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic image of the LC holder. The automatic LC dispenser is realized through a flexible shaft connecting the copper frame with a stepper motor. The automatic wiping mechanism can be seen on the front side of the copper frame. (b) Zoom on the actual holder. (c) Polarized microscope image with an inserted lambda plate of a 3 mm diameter 8CB free-standing film in the smectic A phase.

2.2. Automatic LC Wiper Blade

The wiping procedure can be performed in principle manually, but because the present holder has been designed to expose the FSLC film to intense and/or energetic radiation, which can easily destroy it after a few interactions, an automatic wiping mechanism is installed to quickly redraw fresh LC films up to 1 Hz of repetition rate. The mechanism is remotely controlled and can be synchronized with a specific trigger during the experiment if necessary. The wiper blade is therefore attached to a stepper motor, which imparts the up-down motion via a rotating screw with a specific tread inclination. The range of motion of the motor can be adjusted using pressure sensors at the start and stop positions, and the wiping speed can be adjusted through custom software. A flat profile copper blade was used to draw all FSLC films presented in this work. The blade pressure on the sliding copper surface was adjusted with a tightening screw and fixed in order to be able to form the film, but avoiding major friction. With the travel range reduced to the minimum necessary, the only variable that influences the repetition rate is the wiping speed. At the same time, the success rate of film formation decreases with increasing wiping speed. A success rate formation test of the FSLC film was performed as a function of wiping speed. The temperature of the copper block was set to 29 °C. In this case, 30 µL of 8CB was directly dispensed using a micropipette (Eppendorf Research plus 10–100 µL, Eppendorf SE, Hamburg, Germany) onto the copper block. The results are summarized in Table 1, where it is clear that a wiping speed of 5 mm/s or below guarantees a success rate of 97% or above.

Table 1.

FSLC film formation success rate as a function of blade wiping speed and number of films formed per refill.

2.3. Temperature Control

The LC holder is temperature-controlled in a range between 25 °C and 50 °C, such that the LCs used in the test experiments can be studied in their smectic and nematic phases. In the case of 8CB (Synthon Chemicals GmbH, Wolfen, Germany), the solid–smectic phase transition occurs at approximately 21.5 °C and the smectic–nematic phase transition at 33 °C. The ideal material for the temperature-controlled medium is copper due to its high thermal conductivity and easy machinability. An ADT4722 temperature sensor (AnalogDevices, Wilmington, MA, USA) is screwed into the copper frame (see Figure 2a) and records the temperature of the copper through direct thermal contact with an accuracy of 0.1 °C. An additional temperature sensor is attached to the base of the holder and records the ambient temperature. Two RCH05 power resistors (Vishay Electronic GmbH, Selb, Germany), each with an output power of 5 W, are attached to the side of the copper frame to supply heat to the system. A digital PID control loop that can be accessed via custom software allows the user to set a desired temperature to the holder and to simultaneously monitor and record the current temperature of the holder and the environment. Using power resistors, the holder temperature can rise relatively quickly up to 5 °C per minute. The holder loses thermal energy through convection with the ambient atmosphere, radiation, and conduction through the base plate. These variables are hard to predict since the ambient atmosphere might be purged with different gases and pressures. Furthermore, the holder setup might be changed during the experiments by adding or removing parts (e.g., LC dispenser, shielding, etc.). In all instances, the cooling process is expected to follow an exponential decay and can take particularly long as the holder temperature approaches the ambient temperature. We therefore always keep the holder at least 2 °C to 3 °C above ambient temperature, where the cooling time will not exceed 30 min between setpoints above this threshold. At a constant temperature of 27 °C, the measured standard deviation of the recorded temperature under laboratory conditions is below 0.3 °C. As expected, a successfully formed LC film can, in principle, survive for several hours if unperturbed.

2.4. Automatic LC Dispenser

If no automatic LC dispenser is used, a micropipette supplying 20 µL to 30 µL of preheated LC directly around the circular aperture on the holder is needed. Due to the large excess of deposited LC on the holder, the resulting film thickness becomes quite unpredictable, as each wiping causes the blade to collect a different amount of LC to be stretched over the aperture. To ensure reproducible FSLC formation and consistent thickness, the LC release is automated. An automated solution is especially important when FSLC formation and the LC reservoir must proceed fully remotely without interfering with ongoing experiments. Therefore, an automatic LC dispenser has been installed. It features an upper aperture in the copper block, 5 mm from the main film aperture, functioning as an LC reservoir. The hole measures 9 mm in length and 3.5 mm in diameter. The LC can be supplied by tightening a fine-thread screw at the back of the copper frame. Leaving a 1.5 mm margin at both ends of the screw path results in an effective length of 6 mm and a total reservoir volume of 58 µL. The screw connects to a stepper motor via a flexible shaft (see Figure 2a), allowing the motor to be positioned behind the holder so that any interacting radiation remains unobstructed during the experiment. The stepper motor enables automated, remote control of the dispenser, similar to the wiping mechanism and temperature control. Each motor step releases approximately 10 µL of LC onto the holder surface, ready for the blade to wipe immediately below. Starting from a cleaned copper holder surface and a filled reservoir, the initial setup requires a few steps before stable FSLC film formation is possible. First, a drop of LC must be released, and the wiper driven at a velocity of 2.5 mm/s across the film aperture several times until a stable FSLC film forms. This process is necessary because the LC must be dragged around the aperture and beneath the blade, wetting the entire holder surface and the contact blade. After the first film is successfully formed, it is destroyed by moving the blade one more time over the aperture, as this initial film does not follow a reproducible formation pattern. From then on, the holder can be used under standard conditions to produce FSLC films in a continuous cycle, as each upward stroke of the blade mechanically clears the previous film before a new one is drawn. Using this automatic dispenser, a new 10 µL drop of LC is released every 100 films.

2.5. FSLC Film Thickness and Characterization

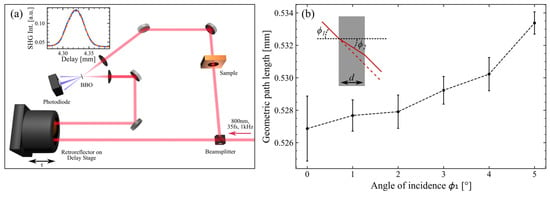

Several studies have specifically focused on determining the thickness and layer spacing of FSLC films, mainly using optical interference, reflectivity, or ellipsometry methods. Rosenblatt and Amer first showed that optical interference of polarized light could be used to determine smectic-A layer spacing in thin films (2 ≤ N ≤ 15), finding an average layer spacing of 31.1 ± 0.2 Å for 8OCB and noting a slight reduction in refractive index in ultrathin films [19]. Matsuhashi et al. improved this approach with transmission ellipsometry using a photoelastic modulator, accurately measuring both thickness and refractive index anisotropy in 8CB films (n∥ = 1.665, n⊥ = 1.523), and revealing a smaller interlayer spacing (~2.4 nm) compared to the bulk (~3.0 nm), indicating strong surface effects [20]. A recent advancement introduced color-based reflectivity mapping, which uses RGB data to quickly produce pixel-resolved thickness maps with sub-nanometer accuracy for films thicker than 100 nm, resulting in an average 8CB layer thickness of 3.10 ± 0.02 nm [21]. Additionally, a reflection spectrum analysis was developed for in situ measurements, correlating absolute reflection intensities with interference theory to determine quantized layer numbers with single-layer precision [22]. Achieving an optically accurate measurement of FSLC thicknesses remains challenging due to refractive index variations, alignment conditions, and scattering. In this work, we constructed an intensity autocorrelator in a non-collinear geometry (similar to a Mach-Zehnder configuration with additional nonlinear interaction in the recombination volume), as shown in Figure 3. Near-infrared (IR) pulsed radiation from a Ti:Sapphire laser system (Coherent Astrella-HE, Coherent -Santa Clara, CA, USA), centered at 800 nm with a pulse duration of 35 fs, 1 mJ energy, and 1 kHz repetition rate, is initially split 50:50 by a beamsplitter, forming the two arms of the autocorrelator. These beams are directed along different optical paths of equal length into focusing lenses, then recombined spatially and temporally into a β-barium borate (BBO) nonlinear crystal (Eksma Optics BBO-601H, Type I, 0.1 mm, Topag Lasertechnik GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) that generates the second harmonic (SH) signal, which is collected by a photodiode (Thorlabs DET100A2, Thorlabs GmbH, Bergkirchen, Germany). Our goal is to collect only the SH signal resulting from the coherent superposition of the two pulses, not the SH generated individually from each arm. The desired signal appears only when both pulses arrive at the same place and time within the BBO crystal, which is well known to be phase-matched at our working wavelengths. Moving the corner mirror in one arm alters the optical path of that pulse, sampling the temporal convolution of the two pulses via SH generation. If one pulse experiences a different optical path length, such as when passing through our FSLC film with a higher refractive index than air, the SH signal will be delayed. Knowing this delay relative to a no-sample condition, combined with the 8CB refractive index at 800 nm, directly yields the FSLC film thickness. Specifically, the delay can be calculated as:

where τ represents the time difference associated with the arrival of the delayed pulse compared to the other, x denotes the displacement of the corner mirror, and c stands for the speed of light when traveling in air. The multiplication by 2 accounts for double passage into the delay stage. The speed of light c varies accordingly to the medium as it depends on its refractive index. Thus, two replicas of the same input NIR pulse created by the beamsplitter will accumulate a different delay because of a difference in optical path length as follows:

where dLC is the thickness of the FSLC film, nLC and nair are the refractive indices of the LC and air at 800 nm, respectively. The refractive index of 8CB depends on the temperature and the wavelength of the incident light. As already mentioned, in SmA-FSLC films, the molecules are arranged perpendicular to the film surface. An incoming beam at normal incidence will consequently only experience the ordinary refractive index. In this work, we interpolated the refractive index of 8CB from the works of ShinTson Wu et al. on 5CB [23] and I. Chirtoc et al. [24] on 8CB at 589 nm. By fitting the autocorrelation signal (see Figure 3a, inset) using a single Gaussian function with offset described by Equation (3):

where I0 is the offset, x0 is the Gaussian center or peak position, w the width and A the amplitude. We extract the FSLC film thickness from the peak positions of the autocorrelation trace in air and across the LC sample as follows:

where the and are mean values over multiple scans of the identified peak position for the sample (‘LC’) and for the air reference (‘air’).

Figure 3.

(a) Schematic of the intensity autocorrelator setup. The inset shows an example of a recorded SH signal: the blue line represents the experimental data, while the red dashed line indicates a single Gaussian fit. (b) Calibration measurements showing the geometric path length of the radiation (800 nm) propagating through a quartz substrate as a function of the angle of incidence. The inset shows a sketch of the optical path s (solid red) considering an incidence angle ϕ1 and a refracted ϕ2 across a SiO2 thickness of d.

Calibration Measurements

To check the accuracy of the autocorrelation setup, a calibration measurement with fused silica was conducted. A thin sheet of fused silica with a nominal thickness of 500 ± 25 μm was mounted in a rotational stage and measured by changing the incident angle ϕ1 of the incoming IR radiation from 0° to 5°. Each measurement included 10 scans, and a reference measurement, without the silica, was performed before and after. Due to refraction, the thickness of the tilted fused silica wafer is not the cosine projection of the thickness (dashed red path in the inset of Figure 3b). According to Snell’s law, the theoretical optical path s length through the fused silica wafer, depending on the angle of incidence ϕ1 can be calculated as

With nSiO2 = 1.4533 being the refractive index of fused silica [25]. In this case and in all the following thickness measurements presented here, each data point results from the average of multiple data acquisitions. In detail, the reference (no sample in the beam path) is the result of 10 averages, while the sample measurement was averaged over 30 to 40 acquisitions, improving the statistics. To each averaged reference and sample peak position, a standard deviation was associated as follows:

with N being the number of measurements, the peak position of a single scan and the mean peak position. Referring to Equation (4), the estimated error in the final thickness measurements is:

Figure 3b shows the measured thicknesses with corresponding error bars, over the 5° angle of incidence, where the normal incidence corresponds to 0°. There is a clear increase in the light pathway as the angle of incidence deviates from the normal incidence, of course taking into consideration also the refraction due to refractive index mismatch. From these experimental data, we determined an average axial resolution of 2.2 ± 0.8 μm. Here, 2.2 μm represents the mean thickness uncertainty across the measured range, while ±0.8 μm is the standard deviation reflecting the consistency of the system’s precision over the different acquisition angles.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Static Measurements

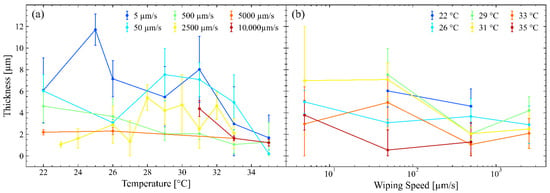

The film thickness was measured at temperatures from 22 °C to 35 °C and wiping speeds ranging from 5 µm/s to 2.5 mm/s, covering three orders of magnitude. As shown in Figure 4a, the film thickness generally decreases with increasing temperature, indicating a clear thermal influence on the structural stability of the FSLC films. The dependence on wiping speed, however, exhibits two distinct regimes separated around 28 °C. Below this temperature, the thinnest films are obtained at the highest wiping speeds. To consider that at a 10 mm/s wiping speed, no stable films could be formed at low temperatures. Above 28 °C, the thinnest and most uniform films form at an intermediate speed of approximately 500 µm/s. This behavior highlights the direct role of mechanical formation rate in determining the final film thickness. Faster wiping speeds consistently produce thinner films, largely independent of temperature, due to the smaller volume of material dragged across the frame during film formation. Viewing the same dataset from another perspective (Figure 4b), where thickness is plotted against wiping speed for each temperature, confirms that higher speeds yield narrower thickness distributions, approximately 2.92 ± 0.79 µm, regardless of temperature. It is important to note that the reported thickness values correspond to the settled, post-formation state, measured only after the blade motion ceased and the film stabilized. The characteristic annealing time, however, varies strongly with both temperature and wiping speed, as discussed in the following section.

Figure 4.

(a) The mean thickness of 8CB films plotted over the temperature for different wiping speeds. (b) The mean thickness of 8CB films for different wiping speeds and temperatures. Error bars are defined in Equation (7).

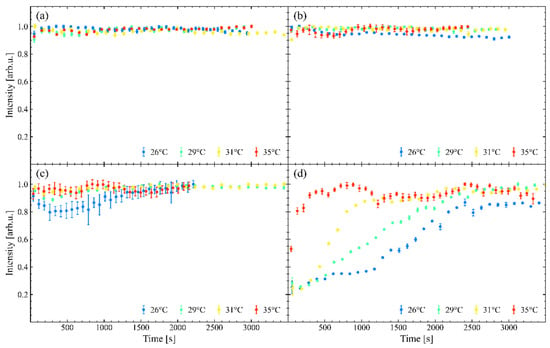

3.2. Time-Resolved Measurements

By recording the autocorrelation signal as a function of time, a clear progressive increase in signal intensity is observed (Figure 5), corresponding to what we refer to as the annealing phase. Time zero is defined as the moment when the blade completes its motion, and the FSLC film is fully formed. The initial absence or suppression of the autocorrelation signal can be attributed to perturbations in the beam path as the near-infrared (NIR) pulse traverses the freshly formed, non-uniform film. Such perturbations degrade both the spatial and temporal coherence of the beam, preventing proper autocorrelation and second harmonic generation (SHG). This loss of coherence arises because the NIR beam encounters spatial variations in thickness and refractive index across its ~1 mm diameter spot. Since the beam is not focused onto the film, any local heterogeneity, whether due to multi-domain molecular alignment or residual thickness gradients, introduces phase distortions through varying optical path lengths, effectively destroying the temporal overlap required for SHG. A comparison of Figure 5a–d reveals that the annealing time depends primarily on the wiping speed, rather than on the formation temperature, except at the highest speeds, where increased temperature accelerates the annealing. In general, the slowest wiping speeds result in negligible annealing times, as the film reaches near-equilibrium during formation. This suggests that slower mechanical spreading allows the LC to relax and self-organize directly during deposition, minimizing post-formation rearrangement of both excess material and molecular alignment. Under these conditions, complete stabilization occurs within only a few minutes after the blade has finished its path.

Figure 5.

Normalized amplitude of the autocorrelation peaks over time for various temperatures at wiping speeds of (a) 5 µm/s, (b) 50 µm/s, (c) 500 µm/s, and (d) 2500 µm/s.

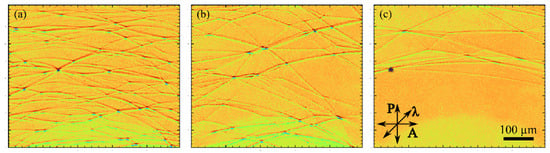

3.3. Polarizing Microscope Analysis

To be able to disentangle whether such a de-coherence effect in the autocorrelation signal is caused by either a molecular orientation process from multi- to single domain (see Figure 2c) or a mass-transfer towards the outer region of the film, we performed a polarized light optical microscopy (POM) study. To this aim we built a horizontal polarized microscope, composed of a standard partially collimated white light source (Thorlabs SOLIS-1D, Thorlabs GmbH, Bergkirchen, Germany), a polarizer, a lambda plate (Leica Mikrosysteme Vertrieb GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany), a 10× microscope lens (Mitutoyo APO lens with a Working Distance: 34 mm, Mitutoyo Corporation, Kanagawa, Japan), an analyzer, a tube lens (Thorlabs TTL200 focal length: 200 mm, Thorlabs GmbH, Bergkirchen, Germany) and a CCD camera (Basler a2A2448-75ucBAS, Basler AG, Ahrensburg, Germany). Figure 6 shows snapshots extracted from the recorded movie (see Video S1 in Supplementary Materials) with the POM at different times along the annealing process. The images are displayed with false color maps in order to enhance the visibility of the structures. The overall movies (see Supplementary Materials) are acquired with a frame rate of 1 frame/s. From the isolated snapshots along the annealing time, it is quite clear that there is no multidomain configuration of the LC film alignment. What is visible quite clearly are evident ripples of excess material traveling outwards, reaching the edges of the films, until a homogenous configuration is reached.

Figure 6.

Polarizing microscope snapshots of a recorded movie of a 26 °C sample after formation at different instants, specifically: (a) at 100 s; (b) at 1000 s and (c) at 2000 s.

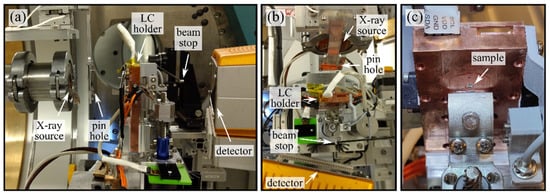

3.4. 8CB FSLC Film Holder Testing for Static X-Ray Diffraction Experiment

Once we understood that the annealing time is entirely due to excess material being expelled from the initial wiped LC over the aperture, we wanted to test the entire equipment and the same annealing process in a static hard X-ray diffraction experiment. The goal was to verify the remote-control functionality of the FSLC holder in terms of temperature control and film formation, as well as to gather precise information about the FSLC film endurance when exposed to such energetic radiation. The experiments were performed at the P23 experimental hutch of PETRA III at DESY in Hamburg. PETRA III is one of the world’s brightest storage-ring-based X-ray radiation sources, with a brilliance of 1018 photons per second, of which up to 8 × 1012 photons per second can reach our sample in the core energy range between 5 keV and 35 keV. For our experiment, we chose a photon energy of 8.9 keV, slightly below the copper X-ray absorption K edge at 8.9789 keV. The beamline uses a heavy-load 5 + 2 circle HUBER diffractometer. The sample platform can be moved in x, y, and z directions and rotated about ϕ (the horizontal plane). For detection, we used an X-Spectrum Lambda 750K detector (X-Spectrum GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) with a pixel size of 55 μm × 55 μm and an array size of 512 × 1536 pixels, covering a field of view of 28 × 85 mm2. It can collect photons with a count rate of up to 8 × 105 counts per second per pixel. The sample-to-detector distance can be selected within a range from several centimeters to meters, allowing for various angular resolutions. The 2D Lambda detector was rotated to provide sufficient q-range coverage in the horizontal scattering geometry. We conducted measurements in an LC temperature range from 24 °C to 36 °C solely in transmission geometry because, in reflection, the FSLC film position prevented the reflected X-ray beam from reaching the detector, as it was located slightly inward compared to the outer edge of the copper block aperture. In transmission geometry, the ϕ-angles were varied to investigate possible effects of exposing the LC’s extraordinary axis to the X-ray beam. ϕ was changed within a range from 0° to 20° around the orthogonal configuration, which is the maximum rotation allowed by the thick copper plate composing the holder. Additionally, a lead foil and a pinhole were installed around the holder to block scattered photons from the air. The final setup is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The sample stack with lead shielding and a pinhole installed. The detector is positioned close to the sample to minimize air absorption. The direct X-ray beam passes through the pinhole, the LC film, and is finally blocked by the beam stop. Only the scattered X-rays reach the detector. (a) side view, (b) top view, and (c) front view and zoom into the sample holder in operation at the beamline. The thin sample film over the aperture is visible by the reflected ambient light.

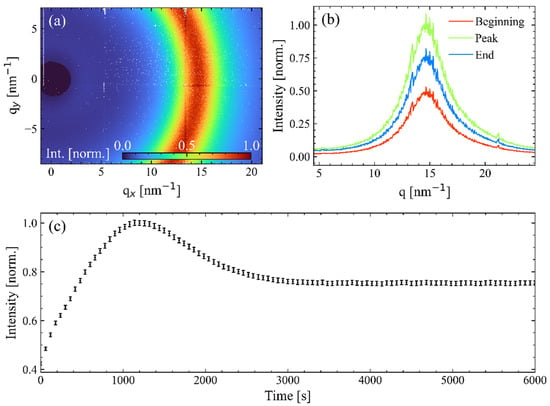

Transmission X-Ray Diffraction Characterization

The structural evolution of the LC films was characterized using X-ray diffraction measurements. This procedure required precise centering of the LC film holder at the diffractometer’s center of rotation. This was achieved by translating the setup along all three spatial axes while monitoring the attenuated transmitted X-ray beam. The LaB6 660c diffraction standard was additionally used for precise calibration of the sample-to-detector distance. The photon energy was set to 8.9 keV, corresponding to a photon flux of 3.8 × 1013 photons/s, and a focused spot size of 300 µm × 300 µm. Under these conditions, the LC film remained stable when exposed to an incident flux density of approximately 4.2 × 1016 photons/cm2·s. A representative detector image recorded in transmission geometry is shown in Figure 8a. For this measurement, the copper block was maintained at 27 °C, with a wiping speed of 5 mm/s and an exposure time of 1 min. After background subtraction, the image reveals a distinct segment of a diffuse ring consistent with the scattering expected from a smectic A film when the film is exposed to the X-rays with the LC director aligned with the beam propagation direction [26]. Due to instrumental limitations, the entire ring could not be captured in a single frame; nonetheless, the data allow an estimated scattering efficiency on the order of 10−5, and from the ring diameter, an intermolecular spacing of approximately 0.43 nm was derived. Figure 8c presents the integrated scattering intensity as a function of time after film formation, while Figure 8b displays the integrated azimuthal intensity profiles of the diffuse scattering ring at successive times following film formation. The temporal evolution closely mirrors the trend observed in the autocorrelation measurements: immediately after refreshing the film (Figure 8b, red, the signal is weak, followed by a gradual increase in intensity over the next 5–10 min, reaching a maximum after approximately 20 min (Figure 8b, green). Thereafter, the signal decays slowly, stabilizing after 45–50 min (Figure 8b, blue). These measurements, performed at 27 °C and a wiping speed of 5 mm/s, show excellent agreement with the SHG signal evolution in Figure 5d (26–29 °C range). The observed modulation in X-ray scattering intensity is thus attributed to temporal variations in the effective scattering mass within the illuminated volume, rather than molecular reorientation effects, as the ring shape remains constant while only its overall amplitude varies.

Figure 8.

(a) XRD transmission image. The diffuse ring corresponds to the intra-layer molecular spacing. (b) Outlines of the diffuse ring at different times after film formation. (c) Integrated XRD signal over time after the film formation.

4. Conclusions

We have developed and demonstrated a fully automated FSLC film holder with independent control of LC volume release, wiping mechanism, and temperature. The system enables reproducible film generation at rates up to 1 Hz with full remote operation, making it well-suited for restricted-access experiments. Film formation was systematically characterized as a function of temperature and wiping speed using real-time thickness measurements obtained by monitoring the difference in optical path lengths of two arms of a standard optical intensity autocorrelation setup. These measurements show that wiping speed is the principal factor governing both the initial film thickness and its subsequent annealing: faster wiping produces thinner, more uniform films due to reduced LC deposition. Temperature becomes relevant only at the highest wiping speeds, where increased thermal energy and decreased viscosity accelerate equilibration; at lower speeds, its influence is minimal. The annealing stage, tracked by the gradual increase in amplitude of the autocorrelation signal (as opposed to a shift related to sample thickness), reflects the relaxation of thickness and alignment inhomogeneities introduced during formation. Time-resolved X-ray scattering corroborates this behavior, revealing a parallel evolution of the diffuse smectic ring intensity. Once annealed, the film thickness and structural properties remain highly stable and largely independent of the initial formation parameters. Furthermore, while the films demonstrated such stability under the synchrotron flux used here, the 1 Hz drawing capability is a key technical feature for broader applications. Given that X-ray FEL deliver peak brightness levels several orders of magnitude higher than synchrotrons, a rapid refresh rate is essential to operate in the ‘diffraction-before-destruction’ regime, ensuring each pulse probes a pristine sample volume. In summary, mechanical formation conditions, particularly wiping speed, dictate the dynamics and uniformity of FSLC films, with temperature acting primarily as a secondary tuning parameter at high speeds. The holder provides a robust, versatile platform for producing high-quality, reproducible FSLC films compatible with a wide range of optical and X-ray setups. Future enhancements, including Peltier-based temperature regulation and vacuum-compatible stepper motors, will further extend its stability and applicability.

Supplementary Materials

Video S1: This is a polarizing optical microscope video recorded after a free-standing film of 8CB liquid crystal in the Smectic A phase is formed at 26 °C. The video is captured in transmission geometry and shows the true color in the polarizing optical microscopy setup. The Polarizer is set vertically in the reference frame of the image axis, the Analyzer perpendicular to it, and the lambda plate is set pointing ‘north-east’. The recording frame rate was set at 1 frame/s. After film formation, a complex network of defect lines is visible, which gradually moves outward until a stable and uniform configuration is found. We assign this mass movement to be the annealing process, which gives rise to the buildup of coherence in the transmitted light pulses and therefore the increase in amplitude of the autocorrelation signal, discussed in the manuscript. The Video can be accessed on https://zenodo.org/records/17872677 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C.; formal analysis, L.C., E.B., M.L. and P.F.; investigation, E.B., M.L., P.F., A.K. and D.N.; resources, L.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.C., E.B., M.L. and P.F.; writing—review and editing, L.C., E.B., M.L., K.M.M.-H., P.F. and A.K.; supervision, L.C. and D.N.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

L.C. would like to acknowledge the Max Planck Group Leader program for funding her independent research. All co-authors would like to thank Yannick Steinhauser, Michael Weissmare and Thomas Wagner as well as the people of the mechanical workshop of the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics, Heidelberg, for their help in the flat FSLC film holder technical design and realization.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 8CB | 4-octyl-4′-cyanobiphenyl |

| LC | Liquid Crystal |

| FSLC | Free-standing liquid crystal |

| SH | Second Harmonic |

| SHG | Second Harmonic Generation |

| IR | Infrared |

| NIR | Near-infrared |

| BBO | Barium borate |

| FEL | Free-electron laser |

| a.u. | Arbitrary unit |

References

- Rosenblatt, C.; Pindak, R.; Clark, N.A.; Meyer, R.B. Freely Suspended Ferroelectric Liquid-Crystal Films: Absolute Measurements of Polarization, Elastic Constants, and Viscosities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1979, 42, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, C.; Meyer, R.B.; Pindak, R.; Clark, N.A. Temperature behavior of ferroelectric liquid-crystal thin films: A classical XY system. Phys. Rev. A 1980, 21, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindak, R.; Young, C.Y.; Meyer, R.B.; Clark, N.A. Macroscopic Orientation Patterns in Smectic-C Films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1980, 45, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopp, C.; Trittel, T.; Harth, K.; Stannarius, R. Smectic Free-Standing Films under Fast Lateral Compression. Soft Matter 2022, 18, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Missaoui, A. Dynamics of Topological Defects in Freely Floating Smectic Liquid Crystal Films and Bubbles. PhD. Thesis, Universite’ Sorbonne, Magdeburg University, Magdeburg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sonin, A.A.; Yethiraj, A.; Bechhoefer, J.; Frisken, B.J. Temperature-Induced Orientational Transitions in Freely Suspended Nematic Films. Phys. Rev. E 1995, 52, 6260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohley, C.; Stannarius, R. Inclusions in Free Standing Smectic Liquid Crystal Films. Soft Matter 2008, 4, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoebe, T.; Mach, P.; Huang, C.C. Surface Tension of Free-Standing Liquid-Crystal Films. Phys. Rev. E 1994, 49, R3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Géminard, J.C.; Holyst, R.; Oswald, P. Meniscus and Dislocations in Free-Standing Films of Smectic-A Liquid Crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 78, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweet, D.J.; Hołyst, R.; Swanson, B.D.; Stragier, H.; Sorensen, L.B. X-Ray Determination of the Molecular Tilt and Layer Fluctuation Profiles of Freely Suspended Liquid-Crystal Films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1990, 65, 2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahr, C.; Fliegner, D. Behavior of a First-Order Smectic-A-Smectic-C Transition in Free-Standing Liquid-Crystal Films. Phys. Rev. A 1992, 46, 7657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoebe, T.; Mach, P.; Huang, C.C. Unusual Layer-Thinning Transition Observed near the Smectic-A-Isotropic Transition in Free-Standing Liquid-Crystal Films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1994, 73, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieranski, P.; Beliard, L.; Tournellec, J.P.; Leoncini, X.; Furtlehner, C.; Dumoulin, H.; Riou, E.; Jouvin, B.; Fénerol, J.P.; Palaric, P.; et al. Physics of Smectic Membranes. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 1993, 194, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loudet, J.C.; Dolganov, P.V.; Patrício, P.; Saadaoui, H.; Cluzeau, P. Undulation Instabilities in the Meniscus of Smectic Membranes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poole, P.L.; Andereck, C.D.; Schumacher, D.W.; Daskalova, R.L.; Feister, S.; George, K.M.; Akli, K.U.; Chowdhury, E.A. Lasers Liquid Crystal Films as On-Demand, Variable Thickness (50–5000 nm) Targets for Intense Lasers. Phys. Plasmas 2014, 21, 063109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, P.L.; Willis, C.; Cochran, G.E.; Hanna, R.T.; Andereck, C.D.; Schumacher, D.W. Moderate Repetition Rate Ultra-Intense Laser Targets and Optics Using Variable Thickness Liquid Crystal Films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 109, 151109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amovilli, C.; Cacelli, I.; Campanile, S.; Prampolini, G. Calculation of the Intermolecular Energy of Large Molecules by a Fragmentation Scheme: Application to the 4-n-Pentyl-4′-Cyanobiphenyl (5CB) Dimer. J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 117, 3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, I.; Bahr, C.; Pieranski, P. Mechanical Properties of Freely Suspended Smectic Films. J. Phys. II 1997, 7, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, C.; Amer, N.M. Optical Determination of Smectic A Layer Spacing in Freely Suspended Thin Films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1980, 36, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuhashi, N.; Okumoto, Y.; Kimura, M.; Akahane, T. Determination of Film Thickness and Anisotropy of the Refractive Indices in 4-Octyl-4′-Cyanobiphenyl Liquid Crystalline Free-Standing Films. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. Part 1 Regul. Pap. Short Notes Rev. Pap. 2002, 41, 4615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yokoyama, H. Rapid Thickness Mapping of Free-Standing Smectic Films Using Colour Information of Reflected Light. Liq. Cryst. 2021, 48, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, B. Structure Formation and Dynamics in Molecularly Thin Smectic Liquid Crystal Films. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Gauzia, S.; Wu, S.-T. High Temperature-Gradient Refractive Index Liquid Crystals. Opt. Express 2004, 12, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirtoc, I.; Chirtoc, M.; Glorieux, C.; Thoen, J. Determination of the Order Parameter and Its Critical Exponent for n CB (n = 5 – 8) Liquid Crystals from Refractive Index Data. Liq. Cryst. 2004, 31, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malitson, I.H. Interspecimen Comparison of the Refractive Index of Fused Silica. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1965, 55, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncton, D.E.; Pindak, R.; Davey, S.C.; Brown, G.S. Melting of Variable-Thickness Liquid-Crystal Thin Films: A Synchrotron X-Ray Study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 49, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.