Abstract

Fully integrated airport access requires managing many aspects from both the passengers’ and the operational point of view. It is noted that air passenger preferences, influenced by distance, time, and other travel-related factors, are one of the fundamentals for understanding airport choice within multi-region airport systems. Therefore, an online survey was conducted in Europe, collecting more than two thousand responses, from which passengers’ attitudes and motives for selecting airport access travel modes were obtained. On the basis of the mobility profile of respondents, Fuzzy C-means (FCM) clustering analysis was performed to identify segments with similar travel attributes. The outcomes of clustering were validated through the comparison between the FCM and K-means clustering algorithms. The results of the study showed that (i) the car was the most preferred mode of transport across different age groups, and (ii) waiting time, travel costs, and travel time were rated as important, with reliability identified as the most important factor when making travel mode choices. These findings may serve as a reference for improving multimodal airport access services and encouraging a shift from private to public transportation modes.

1. Introduction

Due to economic growth and rapid urbanization, mobility systems play a crucial role in meeting individual passengers’ requirements and providing infrastructure accessibility. Air transportation, particularly through low-cost carriers, has experienced steady growth in demand. As a result of this increase, multimodal door-to-door (D2D) trips have become fundamental for providing efficient transportation services. However, seamless D2D multimodal solutions are still limited, since the integration of air transportation with other travel modes is mostly bimodal [1,2]. For instance, dedicated express bus services connecting airports with city centers can lead to significant travel time savings, even though fares are typically higher than those of regular services [3]. Airport managers could improve the operational performance of these services by (i) using the airport curb side as a transit hub, allowing buses to connect with other routes stopping at the airport, and (ii) reducing the cost of express bus services and offering multi-journey fare discounts. Other solutions focus on offering integrated ticketing options (bundles), such as combined rail–air tickets, as well as increasing the attractiveness and competitiveness of rail transportation through proper infrastructure availability [4,5]. For example, the connection of Frankfurt airport with high-frequency long-distance trains to the German and European rail network increased the accessibility of the airport’s catchment area. Also, the features of express train connections (e.g., Stockholm Arlanda or London airports Gatwick, Heathrow, and Stansted) provided travel/waiting time reduction, high frequency, and short-distance accessibility [6]. However, several factors still need to be considered to enhance intermodal integration, including the availability of pick-up and drop-off locations, service frequency, and passengers’ willingness to pay additional fares to obtain reliable D2D service.

A seamless multimodal D2D trip, with air transportation as the main leg, should provide coordinated transport services from origin to destination by integrating multiple modes, such as buses, trains or metro systems, private cars, taxis, and combinations of these modes, for airport access and egress. In view of this paradigm, Mobility as a Service (MaaS) represents a novel sustainable mobility solution that integrates multiple travel mode alternatives into a single mobility service and acts as the journey planner by offering comprehensive service to users (booking and payment via smartphone applications) [7]. Recent studies have demonstrated the positive effects of multiple travel mode options on the willingness of a user to subscribe to MaaS [8]. According to the results of logit models reported in reference [9], which analyzed choices of MaaS bundles at airports/high-speed rail stations, approximately 80% of respondents were willing to subscribe to MaaS. However, the implementation of MaaS, in the context of seamless multimodal airport D2D service, requires efficient airport access/egress, which usually depend on several attributes. These include the availability of the transportation mode during preferred time periods, travel time to reach the airport, service frequency/waiting time, reliability, and comfort. It becomes crucial to gain insights into the general preferences and journey-specific needs of travelers to develop adequate user-centric services. Thus, the proposed study is focused on the assessment of air passengers’ mode choice behavior and the attributes (i.e., travel time, costs, reliability, and delays) that influence their choice of transport modes to the airport, as well as from the airport to their destination. In contrast to previous research that focused on significant factors influencing demand for air travel at national and regional levels [10,11,12], this study emphasizes passengers’ opportunities/willingness to shift from private to more sustainable public travel modes when arriving at or departing from airports.

This study aims to identify clusters of answers/respondents with similar characteristics related to travel attributes and mode choice preferences to match the defined persona types; according to the output from the disseminated survey, five types of personas have been identified. Cluster analysis is carried out, in particular the Fuzzy C-means (FCM) clustering method, which assigns respondents to the cluster with the highest value of the membership degree. The results were validated by comparing FCM with the K-means clustering algorithm. The findings provide insight into the preference of the mode choices, as well as the importance of the factors “waiting time”, “reliability”, “travel costs”, and “travel time” (selected as key attributes influencing the mode choice among different age groups [13]). While previous studies on airport access mode choice and air passenger behavior have primarily relied on discrete choice modelling approaches (e.g., multinomial and mixed logit models), this study applies the FCM approach to elucidate passengers’ views on multimodal airport access, namely the shift towards sustainable D2D solutions. From an empirical perspective, the novelty of this study is based on a large-scale European survey (2199 validated responses) that methodologically provides one of the first passenger-centered clustering analyses of airport access mode choice in a multimodal door-to-door (D2D) context, with a specific focus on passengers’ willingness to shift from private to more sustainable public transport modes.

The structure of this paper is as follows. Section 2 reports a literature review related to recent studies on different clustering methods in the air transportation field, as well as studies that captured passengers’ attitudes when making airport access travel mode choices. The methodology of the proposed study, followed by the description of the survey and the mathematical formulation of the FCM clustering method, is described in Section 3. The results and outcomes of the performed cluster analysis, validated using FCM and the K-means clustering method, are reported in Section 4. Section 5 is dedicated to the overall findings and limitations of this study, while Section 6 is devoted to conclusions and further development.

2. Literature Review

Air passengers’ travel behavior plays a crucial role in forecasting air travel demand and managing airport service operations [14,15,16]. Since accessibility is one of the main factors influencing airport choice in multi-region airports (MARs), it is crucial to establish adequate transportation infrastructure and services following passenger-specific attributes [17]. Thus, an overview of research works on air passengers’ travel behavior, as well as the cluster analysis of air passengers based on their travel characteristics, is summarized in the first and second subsections. The third subsection highlights the contribution of this work with respect to the existing literature.

2.1. Air Passenger Travel Behavior and Ground Access Mode Choice

Airways companies struggle to maintain higher-quality airport service standards, while the efficiency of airport ground operations, such as loading/unloading of luggage into/out of aircraft and baggage transfer, is mainly influenced by the air passenger traffic volume. Due to growing demand, many airports have experienced curbside and roadway congestion during peak periods, leading to modified curb assignments. Reference [18] investigated ground access to major Chinese airports by comparing time and monetary costs of travelling between airports and city centers via private car and public transport. Also, the results of the binomial logit model for analyzing the ground access and airport choice behavior of air passengers in Beijing, China, showed that travel time, travel cost, and the number of transfers can affect the probability of choosing an airport among air passengers who use rail transit frequently [2]. Reference [19] analyzed the airport ground access reliability and resilience of the transit network, considering passenger delays, generalized costs, and volume-over-capacity changes as measures of unplanned service disruptions. In addition, transport operators are interested in providing reliable coordinated transportation services by analyzing the attributes that influence air passengers’ airport access ground mode choice. Reference [20] examined the ground access mode choices of passengers traveling to Port Columbus International Airport and found that business-traveling passengers were more likely to use alternative modes of transportation to reach the airport. For instance, reference [21] investigated air passengers’ access mode of low-cost airports to support policymakers in evaluating improvements to the current ground access transport system.

Especially during summer periods, the analysis of air passenger travel behavior is crucial for preventing flight disruptions and ensuring the smooth functioning of landside operations. For instance, reference [22] provided the methodology for estimating air passengers’ characteristics by collecting indicators from mobile phone records related to flight departure/arrival times, access/egress modes, transfer trips, and passenger tours. Reference [23] conducted a study on the travel behavior of air passengers at Shijiazhuang Airport, where the passenger distribution was primarily in urban areas; the results revealed distance and time decay effects, as the car is the dominant travel mode at this airport. Reference [24] investigated the factors that influence the ground airport access travel mode choice of elderly air passengers using survey data from a Taiwanese sample; the most important factors were safety and user-friendliness. Other studies applied regression models to analyze attitudes of air passenger travel choice decisions [25,26,27]. Reference [28] applied multinomial and nested logit models to examine the behavior of air passengers in regional Western Australia, where travel costs, journey time, service frequency, and seat comfort were found to highly affect mode choice.

2.2. Cluster Analysis on Air Traffic Segmentation

Current research on cluster analysis in the air transportation field is mostly focused on applying different clustering methods to classify airports according to traffic volume measures, network characteristics, operational efficiency [29,30,31,32,33], and clustering analysis for airport parking [34]. For instance, the K-means clustering algorithm in the air transportation field was applied in [35] for clustering airports based on their organizational structure. Another study, proposed by [36], used K-means clustering to classify the airports based on the number of handled passengers. Studies on different airport clustering analyses are summarized in Table 1. For example, [37] used the k-shape clustering algorithm to cluster hubs of the United States according to outbound passenger movements at airport terminals. Another study proposed a new airport clustering algorithm, named Split by City-Pair, for designing an air traffic flow network as a support for Flow Contingency Management [38]. Reference [39] implemented an improved clustering algorithm and used criteria such as altitude, weight, and air speed to analyze the relationship between aircraft flight paths and fuel consumption data to identify the descent path with the lowest average fuel consumption. The results showed a reduction in average fuel consumption of 17.5% and 10.31%, resulting in fuel savings of 81.6 kg and 68.22 kg, respectively. Reference [40] used data-mining techniques and decision tree classification to investigate the relationship between air traffic volume and macro-economic development based on a dataset for Taiwan from 2001 to 2014. Reference [41] used clustering analysis to predict aircraft taxiing estimated time of arrival, thereby improving the operational efficiency of the airports. Also, reference [42] applied the clustering technique and the Gaussian Mixture Model to cluster aircraft trajectories at Suvarnabhumi International Airport.

Table 1.

Studies on airport and air traffic flow clustering analysis.

Although the studies summarized in Table 1 primarily focus on clustering airports, aircraft trajectories, and air traffic flows from an operational perspective, they collectively demonstrate the effectiveness of clustering techniques in handling complex, high-dimensional aviation datasets. While clustering has been extensively applied to airport traffic systems and air passengers, passenger-centered clustering in the context of multimodal door-to-door (D2D) airport access travel remains unexplored. Nevertheless, some related studies have explored cluster segmentation of air passengers. Reference [43] identified three segments of air passengers as those who prefer traditional manual, automated technology-based, and more personalized technology-based processes. Differently, reference [44] described groups of passengers, “conflicted Greens” and “pessimistic lift seekers”, as those with the greatest potential to reduce private car use to airports. Another study [45] examined the attitudes and behaviors of Spanish air passengers based on travel frequency, environmental concern, perception of aviation’s impact, and willingness to adopt sustainable alternatives. In addition, reference [11] applied the hierarchical (agglomerative) procedure (Ward’s Method) and robust non-hierarchical (divisive) clustering technique (K-means) for defining market segments of air passengers according to their shared air travel attitudes and preferences considering data from a survey in Norway; the results showed four distinct passenger segments, e.g., one group involved those with the highest level of concern about flying. In the context of air transport studies, Q-mode hierarchical clustering groups individual observations (e.g., passengers or trips) based on similarity across multiple attributes. In contrast, R-mode hierarchical analysis clusters variables rather than observations and is typically applied to identify relationships among indicators or service attributes. For example, the study proposed by [46] applied Q-mode and R-mode hierarchical cluster analysis to investigate travel mode choice (i.e., transit (bus and metro) and car) based on their characteristics. While these approaches provide useful structural insights, their application in aviation has largely focused on infrastructure performance or service attributes rather than on passenger-centered airport access behavior.

2.3. Contributions

The proposed study focuses on defining different types of air passengers to investigate their attitudes towards airport access travel mode choice within the multimodal travel chain, a topic that has been scarcely considered in the literature. The above-mentioned studies mostly focused on airport segmentation from the perspectives of air traffic and airport service quality, while only a few studies applied FCM clustering analysis to capture air passengers’ preferences. For example, reference [47] used a fuzzy clustering method to analyze the air transport passenger market and to understand travelers’ choices based on service quality factors. According to the outcomes, the travelers were clustered into three types of markets based on their preferences for service quality, high pleasure and low price, and the sensitivity to expense, time, and service. Another study proposed by [48] applied FCM and the Adaptive Neuro Fuzzy Inference System to predict the number of airline travelers.

To fill this gap, the proposed study applied FCM cluster segmentation of air passengers’ attitudes to improve the airport’s accessibility and provide insight for seamless D2D multimodal trips. In addition, cluster segmentation is based on a survey conducted across different European countries, with a large sample of responses (2199 respondents). Furthermore, the outcomes of cluster analysis could support MaaS operators, enabling coordinated multimodal D2D services and providing insights into passengers’ perspectives for moving toward sustainable travel mode solutions.

3. Data and Methodology

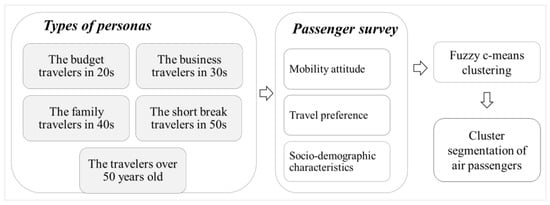

The framework of the proposed study is represented in Figure 1. Different types of personas have been identified, including both business and leisure travelers, varying budget constraints, the process of planning journeys and buying tickets, needs, and motivations. The introduction of personas is not intended to represent rigid, age-exclusive traveler categories. Instead, the “persona” in this study is defined as a conceptual archetype representing combinations of travel purpose, life stage, and mobility needs; further, personas are intended to support understanding of passengers’ attitudes, where age is treated as an analytical variable within the clustering process and not as a rigid classification criterion.

Figure 1.

Methodology of the proposed study.

Those have been classified as budget travelers in their 20s, business travelers in their 30s, family travelers in their 40s, short-break travelers in their 50s, and travelers over 50, while their interactions are described through customer journeys. Different traits, travel behavior characteristics, and mode choice preferences of passengers have been further incorporated to create and conduct the online survey in Europe (primarily in Greece, Italy, Serbia, and Spain). To this point, the first subsection summarizes the findings of the disseminated survey, while the second subsection describes the Fuzzy C-means (FCM) clustering method.

3.1. Survey Description

The Syn + Air survey aimed to quantify the trade-offs passengers consider when selecting a travel mode. Through 25 questions, three main areas of interest have been defined to capture the mobility profile, travel preferences, and the socio-demographic structure of respondents. The travelers’ mobility profile section included relevant information needed to capture their traveling habits (flight frequency, membership in a frequent-flyer program, check-in, and baggage). The travel preference section included the respondents’ trip characteristics (e.g., the travel purpose and frequency, travel mode choice, factors that influence the travel mode choice, opportunities for travel mode shift, private car ownership). The socio-demographic section addressed a few questions on gender, age, employment status, average income, occupation, and household size.

The survey was designed to cover different types and geographic locations of passengers to achieve a representative sample and avoid non-responsive bias [49]. This has been demonstrated by respondents’ willingness to participate in the survey from different geographic locations (Greece, Serbia, Italy, Spain, and other European countries). The questionnaire was administered online within the Syn + Air project and disseminated through project partners’ institutional channels, professional networks, and social media platforms, allowing respondents to share the survey within their networks. The survey concluded with a good response rate of 2251 responses (2199 validated responses), exceeding the Syn + Air target of reaching a minimum of 1200 responses. The process was monitored to obtain high-quality samples (e.g., avoiding an extensive number of student respondents and ensuring more responses from the older population) across different types of passengers: leisure and business travelers, young and older travelers, families or individual travelers, or travelers with reduced mobility. Since one of the common causes of non-responsive bias is poor survey design, a preliminary survey design was constructed. Feedback from the pilot phase was used to refine the question and the overall structure, ensuring both comprehension and a reasonable completion time. The draft questionnaire was piloted among project partners and university colleagues; minor corrections were made to ensure a high level of comprehension and succinctness, as well as to approximate compliance time (i.e., under 20 min on average). Also, the survey was completed in less than two months to avoid time bias caused by changes in travel behavior across different times of the year.

Findings of the Survey

After data cleaning, the dataset contained 2199 responses, of which 719 were from Greece, 562 from Serbia, 444 from Italy, 194 from Spain, and 280 from other countries. The mobility patterns of respondents are summarized in Table 2. The median and mode of the respondents were 39 and 30 years old, respectively; 54.4% were female and 44.5% were male, while 23 individuals chose not to disclose their gender. In general, the most common purpose for traveling by airplane was selected as “mostly for leisure” by 42.02%, “only for leisure” by 26.69%, while 28.14% were “mostly for business” and 3.14% “only for business” travelers. Also, the participants were asked to select their approximate household income (low, average, high, or rather not say) to ensure comparability across countries and to account for subjective income perceptions given differences in salaries and the cost of living across European countries. Most participants in the survey (61.07%) had an average household income, while 20.55% had a high income. Descriptive statistics related to travel mode choice to/from the airport showed that most respondents, about 40.11%, selected the “Car (someone drops me off/picks me up)” mode choice. In contrast, the minimum percentage of responses, i.e., 2.59%, is associated with the bus mode choice. In addition, most respondents, 43.2% of them, have one car, while 36.3% have two, and 8.23% have more than two cars. Furthermore, the highest number of respondents, i.e., 34.88%, rated the factor “reliability” as “more important” in making the travel mode choice, while 33.97% outlined this as the “most important”. As regards the mode choice selection among different countries, which might vary depending on the level, frequency, availability of transportation service supply, the summary is as follows: (i) 24% of the respondents from Spain prefer car/metro mode choice; (ii) car (as a passenger) mode choice is preferred by 53% of the respondents from Greece, 34% from Italy and 48% from Serbia; (iii) 38% of the respondents from other countries prefer the car (as a passenger) mode choice.

Table 2.

Characteristics of survey respondents (total of 2199).

Table 3 reports the outcomes of Pearson correlation related to the significant negative and positive correlation among the age groups: (i) 18 to 29 years; (ii) 30–39 years; (iii) 40–49 years; (iv) over 50 years old. Respondents in the age group 18 to 29 years were negatively correlated with traveling mostly for business and positively correlated with traveling mostly for business purposes. Responses in this age group are negatively correlated with printing the boarding pass and having frequent-flyer program memberships; also, there is a positive correlation with the preference for using PT when traveling as a group of five or more people and using car (as passenger) mode for traveling to/from the airport. The cost factor is important when traveling to and from the airport. Respondents in this age group were positively associated with Greek residence and negatively with Serbian residence; the considered age group is mostly students (high positive correlation of 0.547), while a negative correlation was observed among employees in the public and private sectors.

Table 3.

Main Pearson correlations among different age groups of respondents.

The results of the significant correlations for the age group 30 to 39 years showed that respondents do not prefer paper boarding passes when traveling by airplane. Also, for this age group, the cost factor was important in deciding which mode to choose when traveling to and from the airport. The investigated age group was positively associated with Greek residence and negatively associated with Serbian residence. In addition, respondents were positively correlated with employment status in the private sector and negatively correlated with student status.

The age group of 40 to 49 years was positively correlated with traveling mostly for business. On the other hand, the process of “walking to the gate” at the airport was negatively correlated with the considered age group. Unlike previous age groups, the cost factor was negatively correlated with travel mode selection. The respondents were positively associated with Serbian residence and negatively with Greek residence; with respect to employment status, the respondents were positively associated with public sector employment and negatively with student status. The Pearson correlation for the age group over 50 years old showed a positive correlation with traveling mostly for business and negative correlation with traveling only for leisure. Also, respondents were positively correlated with having a paper ticket when traveling by airplane. In addition, respondents were found to be positively correlated with Italian and negatively with Greek residence; the respondents were positively correlated with employment in the public sector and negatively with the private sector. According to income-related questions, this age group is negatively correlated with low income.

3.2. Fuzzy C-Means Clustering Method

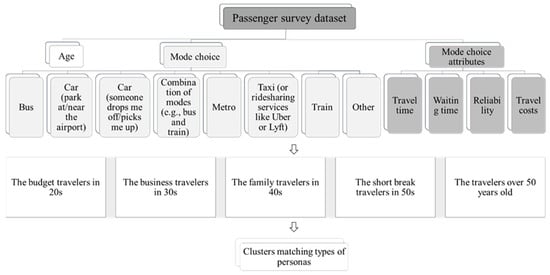

Clustering analysis was applied to match responses within defined types of personas while, at the same time, investigating the impact of multimodal travel choices from passengers’ perspectives. The main questions are as follows: (i) Q7 is related to the mode choice (If all of the following transport modes are available, which one would you choose to travel to/from the airport?), where the mode choice alternatives were defined as bus, car mode (as driver), car mode (as passenger), combinations of modes (e.g., bus and train), metro, taxi (or ridesharing services like Uber or Lyft), train, and other; (ii) Q17 is related to the mode choice attributes (How much do the following factors influence your choice of mode when traveling to and from the airport?), where factors were defined as travel time, waiting time, reliability and travel costs; (iii) Q20 is related to the age of respondents to describe various personas (see Q7, Q17 and Q20 in Figure 2). Q17 is a Likert-scale question, in which the factors “waiting time”, “travel time”, “travel costs” and “reliability” (e.g., most investigated in the literature [13]) were selected for the forthcoming cluster analysis. Those factors were selected based on the highest number of responses, their quantitative nature, and their familiarity with transport operators.

Figure 2.

Obtained dataset from passenger survey applied in clustering analysis.

The Fuzzy C-Means (FCM) clustering method, an extension of K-means clustering, was applied. As travelers could belong to more than one cluster, the respondents have high similarity within one cluster and are very dissimilar to those in other clusters. The FCM clustering method is considered an adequate technique, as different types of attributes can be assigned to clusters more flexibly, especially when it is difficult to identify clear boundaries between clusters [50]. Since clusters are associated with the types of personas, their age groups can be subject to slight variation; for example, respondents in their 30s can be “business” and “family” travelers. Thus, through this method, each respondent could belong to a certain cluster with a different degree of membership function.

The formulation of the FCM clustering method, initially proposed by [51], is described as follows. The denotes the dataset of answers/respondents so that , while is the total number of groups/clusters , so that . The number of clusters in FCM was set as five () to match the individuated types of personas. The FCM involves pre-processing a dataset to portray all variables of the same type as numeric (e.g., Likert scale). The main advantage of FCM, compared to “hard” clustering, is the formation of new clusters from the answers/respondents that have closer membership values to the centers of clustering groups, where is the degree of the membership of in the cluster . FCM is an iterative algorithm that updates the membership values and cluster centers according to the objective function (Equation (1)) that aims at minimizing the distance (i.e., dissimilarities among the datasets within the cluster ) [52]:

where is any real number greater than 1, i.e., , as in most cases [53].

Accordingly, the steps of the FCM algorithm are defined as follows:

Step 1. Initialize membership matrix

Step 2. After the initialization of the membership matrix , the center of cluster at k-step is calculated as follows:

Step 3. Update . The updated membership value at k-step, with center vectors and is calculated as follows:

Step 4. If ||U(k + 1) − U(k)|| < α then STOP; otherwise return to Step 2. The algorithm performs until the condition is satisfied, where α is the predefined threshold, α = 10−5.

For further details on the FCM clustering method, see [52,53,54].

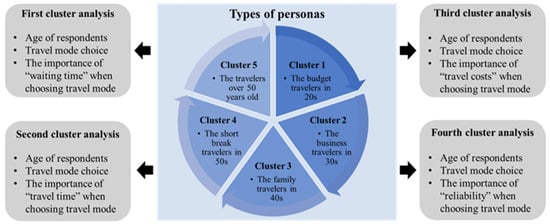

4. Results of Cluster Analysis

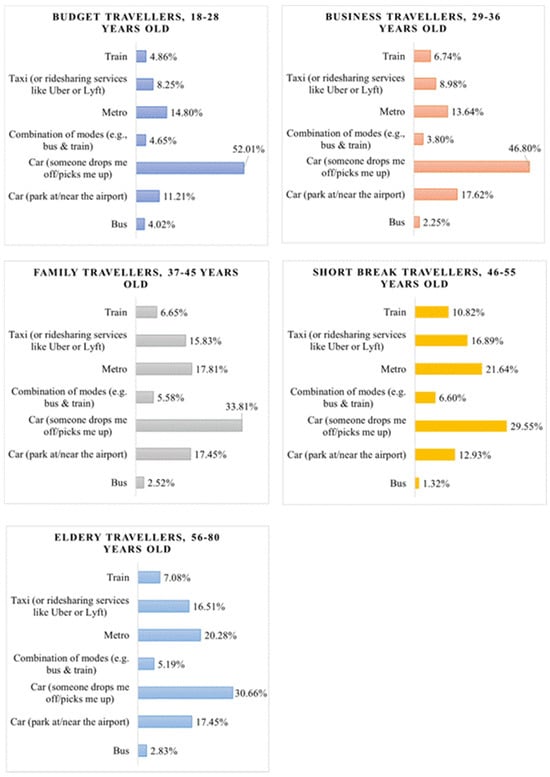

Based on the factors/attributes that influence the travel mode choice for arriving/departing to/from the airport, four different cluster analyses are displayed, as shown in Figure 3. Therefore, the cluster analysis depicts five types of personas that are influenced by the “waiting time” factor in the first analysis, the “travel time” factor in the second analysis, the “travel costs” factor in the third analysis, and the “reliability” factor in the fourth cluster. As a result, Figure 4 depicts the approximate share of the travel mode choice within five clusters, obtained from the four clusters’ analysis, summarized as follows. Budget and business travelers have a 14% to 18% higher preference for the car (as passenger) mode choice than other age groups. However, the car (as driver) mode choice has the lowest share of 11% among budget travelers, while the car (as driver) mode choice has the highest share (18%) among business and family travelers. The metro mode choice, with about 20%, is preferred among short-break and elderly travelers. Moreover, the percentage of respondents, from 37 to 80 years, who selected taxi as a mode choice is two-times higher than for younger participants. Nevertheless, the lowest preference was for train, followed by the combination of modes and bus mode choice, at around 10% and 5%, respectively.

Figure 3.

Framework of four clusters’ analysis.

Figure 4.

The share of the travel mode choice according to the obtained clusters.

Specifically, clusters with age groups from 18 to 28 years have the highest preference for the car (as passenger) mode choice, with a 52% share, while a 15% share is for metro and less than 10% for other travel mode choices. Similarly, the 29–36 age group accounted for about 48% of car (as passenger), 18% of car (as driver), 14% of metro mode choice, and less than 10% for other alternatives. Differently, clusters with the age group from 37 to 45 years resulted in a more equally distributed share of travel modes: (i) 34% for car (as passenger); (ii) 18% car (as driver); (iii) 16% for metro and taxi mode choice, respectively. Clusters with age groups from 45 to 55 years have 29% and 23% preference for the car (as passenger) and the metro, 18% for the taxi, and less than 15% for the car (as driver). Also, the cluster with the age group from 56 to 80 years has a 32% preference for car (as passenger), 20% for metro, 16% for car (as driver), and 15% for taxi mode choice. However, we omitted the representation of “other” travel mode share in Figure 4 due to the very low number of responses.

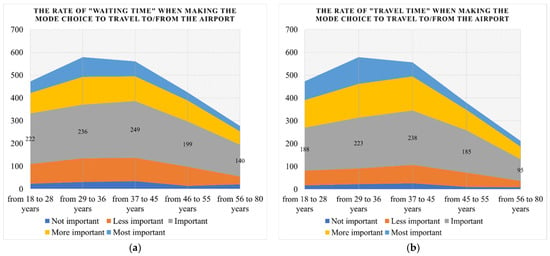

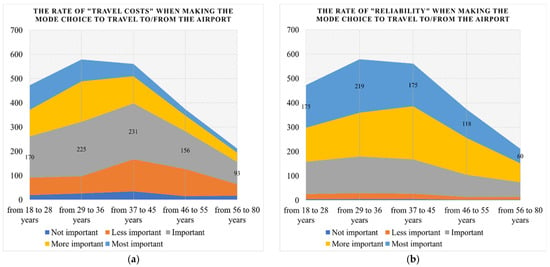

In addition, Figure 5 shows the importance of the factors “waiting time” and “travel time”, while Figure 6 shows factors “travel costs” and “reliability” when making the travel mode choice for arriving/departing at/from the airport across different age groups. The rating of factors as “not important” and “less important” was selected by the minimum number of participants. For example, the highest number of respondents within the cluster groups rated the factors “waiting time”, “travel time”, and “travel costs” as important. The factor “reliability” was rated by the most respondents as “more important” and “most important” when making the travel mode choice. In this context, the figure presents the numerical values for the highest number of respondents’ ratings of travel mode choice factors within each cluster. Furthermore, Table 4 reports the results of the FCM clustering analysis considering the value of the objective function and cluster centers .

Figure 5.

The importance of: (a) waiting time among four clusters; (b) travel time among four clusters.

Figure 6.

The importance of: (a) travel costs among four clusters; (b) reliability among four clusters.

Table 4.

Results of the FCM cluster analysis.

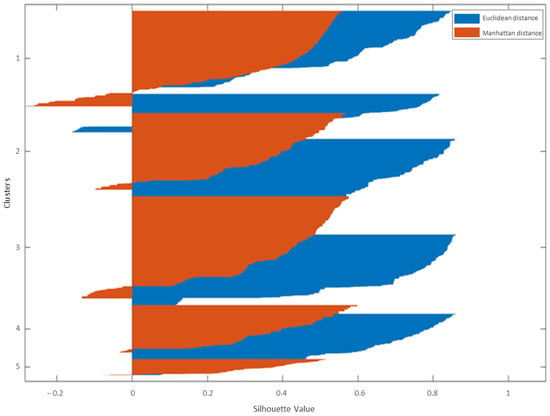

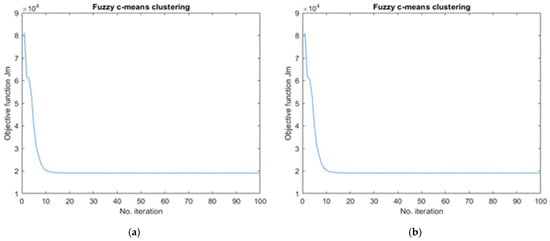

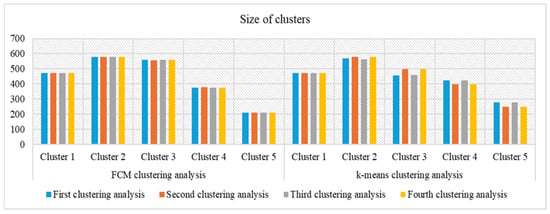

Comparison of Fuzzy C-Means and K-Means Clustering Analysis

The outcomes of FCM clustering analysis were compared with the K-means clustering algorithm, which, similarly to FCM, partitions the dataset into predefined distinct clusters in a way that data points within the same cluster are more similar than those in other clusters [55]. The measurement of similarity between two data elements was performed using the Euclidean distance measure. As depicted in Figure 7, silhouette values ranging from −1 to 1 indicate the goodness of fitting data within the clusters, in a way that higher values (greater than 0.5) have better matching within the clusters, as in the case of Euclidean distance. At the same time, a high silhouette score indicates that most clusters are well separated from others so the average silhouette scores for five clusters were 0.37 for the Manhattan distance and 0.59 for the Euclidean distance. Consequently, Figure 8 compares the computational performance of FCM and K-means clustering, showing that the FCM algorithm reaches the minimum value of the objective function after 100 iterations, whereas K-means reaches it after 5 iterations. However, although the complexity of the K-means clustering algorithm is less complex than FCM, the outcomes of the FCM analysis showed less dissimilarities and variations in the sizes of the clustering segmentation groups, as reported in Figure 9.

Figure 7.

The representation of Euclidean and Manhattan silhouette values of K-means clustering analysis.

Figure 8.

The computational performance of: (a) FCM clustering method; (b) K-means clustering method.

Figure 9.

The comparison of clusters’ size between the FCM and K-means clustering analyses.

The findings of the FCM and K-means clustering analyses regarding the travel mode choice and the importance of the factors in selecting travel mode choice are reported in Appendix A, Appendix B, Appendix C and Appendix D. According to the FCM clustering in the first cluster analysis, most participants chose “car (someone drops me off/picks me up)” and the factor “waiting time” as “important” when making the mode choice. Most respondents in the largest cluster (579), i.e., business travelers in their 30s, preferred “car (someone drops me off/picks me up)” as a mode choice and rated “waiting time” as an “important” factor. Similarly, in the case of K-means clustering, most respondents preferred “car (someone drops me off/picks me up)” and rated “waiting time” as “important”. The results of the second clustering analysis showed that most participants in the survey selected “car (someone drops me off/picks me up)” as their mode choice and rated “travel time” as “important”. For example, the largest-sized cluster belonging to the age group from 29 to 36 years with 579 respondents, in both FCM and K-means clustering analysis, selected “car (someone drops me off/picks me up)” as a mode choice and “travel time” as “important”. Also, in the third clustering analysis, most participants selected the “car (someone drops me off/picks me up)” mode and rated the factor “travel costs” as “important”. However, it can be observed that most respondents in the fourth clustering analysis, both in the FCM and K-means clustering analyses, rated the factor “reliability” as “most important” or “more important” when making the mode choice. For example, the age group from 18 to 28 years and from 29 to 36 years, both for FCM and K-means clustering analysis, rated the “reliability” as “most important”, while other age groups rated it as “more important”.

5. Discussion

Due to increasing air traffic flow, transport operators are facing challenges in providing efficient airport access and connectivity with other transportation modes. The possibilities for reaching the airport by different travel modes usually differ in both travel time and cost, with some travelers preferring a more expensive but faster mode, while others choose a cheaper but slower mode. Usually, non-residents have lower car ownership and, since they do not use private cars, they opt for public transport more frequently. Also, some travelers may prefer more reliable services, such as public transportation. Travelers using private cars often face a limit on the maximum dwell time at the curbside; at the same time, a higher number of taxi vehicles could lead to congestion at the airport’s curbside. In this context, the results of the cluster analysis and the comparison between FCM and K-means clustering showed different habits/attitudes of passengers across age groups but, at the same time, common travel mode preferences within the same cluster segment (Table 5).

Table 5.

Summary profile of derived clustering analysis.

In summary, the cluster labeling derived from the joint interpretation of dominant airport access mode choices, relative importance of access mode attributes, and trip purpose characteristics, rather than only age. For instance, the cluster group indicated budget travelers showed a stronger preference for the car (as passenger) mode, about 52%, due to the highest importance of waiting time and travel costs; on average, around 200 respondents within this cluster group rated waiting time and travel costs as important when selecting travel mode (see Appendix A, Appendix B, Appendix C and Appendix D). This further justifies a stronger preference for car (as passenger) and metro modes and a predominance of leisure-oriented trips. Similar findings can be found in the literature [56]. Reference [21] demonstrated that low-cost airline passengers consider not only cost but also time savings valuable when choosing an access mode. In addition, the cluster group comprising business travelers showed slightly lower preference for the car (as driver) travel mode, resulting in around 47%. At the same time, this preference is distinguished by the highest importance of factor reliability when choosing travel mode, compared to all other age groups (about 219 respondents). Differently, cluster groups with family travelers (and short-break travelers), mostly influenced by travel and waiting time factors, showed lower preference for the car mode than previous clusters. Furthermore, the cluster comprising short-break travelers and travelers over 50 showed a higher preference for car-based modes and an almost two-fold higher preference for taxi use. This finding is well aligned with previous studies. For instance, based on [24], elderly passengers prefer to ask family members to drive them to the airport or take a taxi due to the importance of safety and user-friendliness.

With respect to previous studies, the results of the cluster analysis showed the opportunities to shift to more sustainable modes. Although private modes show a valuable preference among all age groups, with 52% being the highest, it is, at the same time, significantly lower compared to other studies [13,20]; the results of the study proposed by reference [13] indicate that private cars and taxis account for approximately 85% of the choices for traveling to the airport.

Implications for Airport Planning and MaaS Design

The cluster segmentation suggests that pricing strategies, efficiency of transportation service, and timetable coordination play a key role in encouraging shifts toward public transport. For these groups, MaaS bundles combining integrated ticketing, fare discounts, and synchronized schedules across metro, bus, and rail services can significantly improve the attractiveness of airport access modes. Integrating these features into MaaS platforms can enhance tailored service, enabling personalized journey recommendations and reducing dependence on private cars. From a planning perspective, this implies the need to manage curbside operations and their seamless integration into MaaS applications.

Another important aspect of adopting public transit and multimodal airport transportation connectivity is reliability. MaaS operators would be interested in enhancing the reliability of airport access modes to provide coordinated multimodal airport D2D service without delays and flight cancelations. This is supported by the outcomes of the cluster analysis, in which the highest number of respondents within clusters rated factor reliability as “most important” when making their mode choice (see Figure 6). Coordinated multimodal airport D2D service would have a positive impact on budget travelers who opt for cheaper travel mode options, as well as budget/family/business travelers who value a reliable transportation service with no delays/waiting time or increased travel time. The public modes’ reliability in managing unexpected events (e.g., delays, traffic congestion, missed flights) could decrease the preference for private mode solutions and, in this case, the possibilities for shifting to metro/train/combination of modes. In this way, MaaS operators could take actions to improve efficiency, such as developing new strategies based on a robust understanding of passenger responses to mobility options, future mobility changes, and their incorporation into infrastructure designs. Also, the development of reliable multimodal airport D2D service and transportation infrastructure accessibility would have a positive impact on passengers living in more rural areas/suburban communities. Furthermore, improved infrastructure, including connectivity between airports and bus/train/metro modes, would benefit airport operators in managing their parking facilities and mitigating the number of taxi vehicles at the airport’s curbside.

6. Conclusions

This study proposed Fuzzy C-means (FCM) clustering analysis to segment passengers’ airport access mode behavior by persona types in a multimodal D2D trip chain. The different types of personas were identified from the dataset obtained from the disseminated online survey, based on mobility profile, age, and socio-demographic characteristics of air passengers. Survey participants were asked to select the travel mode to/from the airport among car (as driver), car (as passenger), bus, metro, taxi, and train and to rate the importance of the factors that influence their travel alternative. Consequently, five clusters were identified to match personas with similar aspects of travel attributes and mode choice preferences. The results of the FCM cluster analysis, validated by comparing with the K-means clustering algorithm, are in line with the findings from recent studies and can be summarized as follows. Cluster segmentation shows that budget travelers and business travelers have a stronger preference for the car (as passenger) mode choice than other clusters, while the car (as driver) mode has the lowest share among budget travelers. The car (as driver) mode has the highest share among business and family travelers since they are willing to pay more for comfort. Furthermore, short-break travelers and travelers over 50 have a higher preference for metro mode than other age groups.

While previous studies of air passenger mode choice behavior have mainly focused on airport access mode choice models (e.g., multinomial, mixed logit, regression models), this study investigated the segmentation of air passengers’ attitudes towards multimodal airport access mode choices and their willingness to shift from private to public travel modes. In this context, the limitation of this study is the lack of a broader range of factors that influence airport access mode choice, as well as the application of other clustering techniques that consider the presence of mixed, categorial, and numerical data types. Differently, the proposed study focused on the most meaningful factors that affect the travel mode choice, such as waiting time, reliability, travel costs, and travel time, and that match those investigated in the literature [28]. The strong emphasis on those factors suggests that future airport planning and policy should prioritize integrated, high-frequency, and resilient ground access services. In this context, this study’s outcomes highlight the importance of airport ground access as an integral component of future air transportation systems. Additionally, these could be an indication for improving coordination between air transport and ground modes, reducing dependence on private cars, and adapting more effectively to mobility expectations. In this respect, future research could extend the analysis by incorporating a broader range of qualitative and contextual factors, such as comfort, luggage handling, and accessibility needs. For further developments, we intend to investigate the concept of seamless multimodal D2D trips by applying modal choice regression for developing the factors that influence travel mode choice and integrating those within the cluster analysis of the air passengers’ behavior for obtaining the decision support system that would help MaaS operators in providing a coordinated multimodal service.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C. and M.O.; methodology, A.C.; software, A.C.; validation, A.C. and M.B.; formal analysis, A.C.; investigation, A.C. and M.B.; resources, M.O.; data curation, A.C. and M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.; writing—review and editing, A.C., M.B. and M.O.; visualization, A.C.; supervision, M.O.; project administration, M.O.; funding acquisition, M.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was developed within the project Syn + Air: “Synergies between transport modes and air transportation” supported by SESAR Joint Under-taking under the European Union’s Horizon 2020, grant number: No. 894116. The study was developed within the MOST–Sustainable Mobility National Research Center of Italy and received funding from the European Union Next-GenerationEU (Italian Recovery and Resilience Plan–PNRR–Mission 4 Component 2, Funding line 1.4–D.D. 1033 17/06/2022, grant number: No. CN00000023).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to obtaining an exemption from the Politecnico di Bari’s Ethics Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of privacy, legal and ethical reasons. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

First clustering analysis (waiting time rating) comparison between FCM and K-means method.

Table A1.

First clustering analysis (waiting time rating) comparison between FCM and K-means method.

| FCM Clustering Analysis | K-Means Clustering Analysis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | |

| Min. age | 37 | 29 | 56 | 18 | 46 | 44 | 54 | 36 | 18 | 29 |

| Max. age | 45 | 36 | 80 | 28 | 55 | 53 | 80 | 43 | 28 | 36 |

| Bus | 14 | 13 | 6 | 19 | 5 | 3 | 8 | 14 | 19 | 13 |

| Car (as driver) | 97 | 102 | 37 | 53 | 49 | 60 | 43 | 80 | 53 | 102 |

| Car (as passenger) | 188 | 271 | 65 | 246 | 112 | 129 | 86 | 150 | 246 | 271 |

| Comb. of modes | 31 | 22 | 11 | 22 | 25 | 28 | 14 | 25 | 22 | 22 |

| Metro | 99 | 79 | 43 | 70 | 82 | 100 | 54 | 70 | 70 | 79 |

| Other | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Taxi | 88 | 52 | 35 | 39 | 64 | 75 | 43 | 76 | 39 | 45 |

| Train | 42 | 39 | 15 | 23 | 36 | 28 | 29 | 39 | 23 | 36 |

| Not important | 34 | 31 | 14 | 23 | 16 | 14 | 20 | 30 | 23 | 31 |

| Less important | 103 | 104 | 27 | 87 | 69 | 84 | 35 | 81 | 87 | 103 |

| Important | 249 | 236 | 109 | 222 | 178 | 199 | 140 | 202 | 222 | 231 |

| More important | 109 | 122 | 46 | 90 | 80 | 92 | 58 | 88 | 90 | 119 |

| Most important | 66 | 86 | 16 | 51 | 31 | 36 | 24 | 54 | 51 | 85 |

| Size of clusters | 561 | 579 | 212 | 473 | 374 | 425 | 277 | 455 | 473 | 569 |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Second clustering analysis (travel time rating) comparison between FCM and K-means method.

Table A2.

Second clustering analysis (travel time rating) comparison between FCM and K-means method.

| FCM Clustering Analysis | K-Means Clustering Analysis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | |

| Min. age | 37 | 29 | 56 | 18 | 45 | 37 | 55 | 29 | 18 | 45 |

| Max. age | 45 | 36 | 80 | 28 | 55 | 44 | 80 | 36 | 28 | 54 |

| Bus | 14 | 13 | 6 | 19 | 5 | 14 | 7 | 13 | 19 | 4 |

| Car (as driver) | 97 | 102 | 37 | 53 | 49 | 89 | 40 | 102 | 53 | 54 |

| Car (as passenger) | 188 | 271 | 65 | 246 | 112 | 169 | 79 | 271 | 246 | 117 |

| Comb. of modes | 31 | 22 | 11 | 22 | 25 | 28 | 13 | 22 | 22 | 26 |

| Metro | 99 | 79 | 43 | 70 | 82 | 82 | 50 | 79 | 70 | 92 |

| Other | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Taxi | 88 | 52 | 35 | 39 | 64 | 78 | 38 | 52 | 39 | 71 |

| Train | 37 | 39 | 15 | 23 | 41 | 37 | 23 | 39 | 23 | 33 |

| Not important | 26 | 22 | 9 | 17 | 10 | 24 | 10 | 22 | 17 | 11 |

| Less important | 81 | 69 | 28 | 65 | 63 | 74 | 35 | 69 | 65 | 63 |

| Important | 238 | 223 | 95 | 188 | 185 | 212 | 113 | 223 | 188 | 193 |

| More important | 149 | 148 | 55 | 121 | 90 | 131 | 63 | 148 | 121 | 100 |

| Most important | 62 | 117 | 25 | 82 | 31 | 57 | 29 | 117 | 82 | 32 |

| Size of clusters | 556 | 579 | 212 | 473 | 379 | 498 | 250 | 579 | 473 | 399 |

Appendix C

Table A3.

Third clustering analysis (travel cost rating) comparison between FCM and K-means method.

Table A3.

Third clustering analysis (travel cost rating) comparison between FCM and K-means method.

| FCM Clustering Analysis | K-Means Clustering Analysis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | |

| Min. age | 37 | 29 | 56 | 18 | 46 | 36 | 54 | 29 | 18 | 44 |

| Max. age | 45 | 36 | 80 | 28 | 55 | 43 | 80 | 36 | 28 | 53 |

| Bus | 14 | 13 | 6 | 19 | 5 | 14 | 8 | 13 | 19 | 3 |

| Car (as driver) | 97 | 102 | 37 | 53 | 49 | 80 | 43 | 102 | 53 | 60 |

| Car (as passenger) | 188 | 271 | 65 | 246 | 112 | 150 | 86 | 271 | 246 | 129 |

| Comb. of modes | 31 | 22 | 11 | 22 | 25 | 25 | 14 | 22 | 22 | 28 |

| Metro | 99 | 79 | 43 | 70 | 82 | 75 | 54 | 74 | 70 | 100 |

| Other | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Taxi | 88 | 52 | 35 | 39 | 64 | 76 | 43 | 45 | 39 | 75 |

| Train | 42 | 39 | 15 | 23 | 36 | 39 | 29 | 36 | 23 | 28 |

| Not important | 35 | 26 | 17 | 19 | 15 | 25 | 20 | 25 | 19 | 23 |

| Less important | 132 | 71 | 47 | 73 | 112 | 104 | 65 | 69 | 73 | 124 |

| Important | 231 | 225 | 93 | 170 | 156 | 200 | 123 | 216 | 170 | 166 |

| More important | 112 | 167 | 38 | 109 | 65 | 85 | 46 | 165 | 109 | 86 |

| Most important | 51 | 90 | 17 | 102 | 26 | 46 | 23 | 89 | 102 | 26 |

| Size of clusters | 561 | 579 | 212 | 473 | 374 | 460 | 277 | 564 | 473 | 425 |

Appendix D

Table A4.

Fourth clustering analysis (reliability rating) comparison between FCM and K-means method.

Table A4.

Fourth clustering analysis (reliability rating) comparison between FCM and K-means method.

| FCM Clustering Analysis | K-Means Clustering Analysis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | Cluster | |

| Min. age | 37 | 29 | 56 | 18 | 46 | 37 | 55 | 29 | 18 | 45 |

| Max. age | 45 | 36 | 80 | 28 | 55 | 44 | 80 | 36 | 28 | 54 |

| Bus | 14 | 13 | 6 | 19 | 5 | 14 | 7 | 13 | 19 | 4 |

| Car (as driver) | 97 | 102 | 37 | 53 | 49 | 89 | 40 | 102 | 53 | 54 |

| Car (as passenger) | 188 | 271 | 65 | 246 | 112 | 169 | 79 | 271 | 246 | 117 |

| Comb. of modes | 31 | 22 | 11 | 22 | 25 | 28 | 13 | 22 | 22 | 26 |

| Metro | 99 | 79 | 43 | 70 | 82 | 82 | 50 | 79 | 70 | 92 |

| Other | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Taxi | 88 | 52 | 35 | 39 | 64 | 78 | 38 | 52 | 39 | 71 |

| Train | 42 | 39 | 15 | 23 | 36 | 37 | 23 | 39 | 23 | 33 |

| Not important | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 2 |

| Less important | 22 | 24 | 11 | 22 | 11 | 19 | 11 | 24 | 22 | 14 |

| Important | 141 | 151 | 60 | 132 | 92 | 122 | 75 | 151 | 132 | 96 |

| More important | 218 | 180 | 78 | 140 | 151 | 193 | 90 | 180 | 140 | 164 |

| Most important | 175 | 219 | 60 | 175 | 118 | 159 | 71 | 219 | 175 | 123 |

| Size of clusters | 561 | 579 | 212 | 473 | 374 | 498 | 250 | 579 | 473 | 399 |

References

- Albalate, D.; Bel, G.; Fageda, X. Competition and Cooperation between High-Speed Rail and Air Transportation Services in Europe. J. Transp. Geogr. 2015, 42, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.J.; Jia, H.H.; Dai, F.; Diao, M. Understanding the Ground Access and Airport Choice Behavior of Air Passengers Using Transit Payment Transaction Data. Transp. Policy 2022, 127, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riza, L.; Bruehl, R.; Fricke, H.; Planing, P. Will Air Taxis Extend Public Transportation? A Scenario-Based Approach on User Acceptance in Different Urban Settings. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2024, 23, 101001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Wang, Q.; Yang, H.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, Y. Effects of Beijing-Shanghai High-Speed Rail on Air Travel: Passenger Types, Airline Groups and Tacit Collusion. Res. Transp. Econ. 2019, 74, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, S.; Popfinger, M. Evaluating the Substitutability of Short-Haul Air Transport by High-Speed Rail Using a Simulation-Based Approach. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2022, 15, 100632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichmuth, D.J. Airport Accessibility in Europe. In Air Transport and Airport Research; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2010; Volume 32, Available online: https://transport.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2016-09/2010-airport-accessibility-in-eu.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Kamargianni, M.; Matyas, M.; Li, W.; Schafer, A. Feasibility Study for “Mobility as a Service” Concept in London; ULC Energy Institute: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Rasouli, S. The Influence of Latent Lifestyle on Acceptance of Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS): A Hierarchical Latent Variable and Latent Class Approach. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2022, 159, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Sun, Y.; He, Y.; Li, Y. The application potential of Mobility as a Service (MaaS) at mega events: A case study of Hangzhou 2022 Asian Games. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 427, 139211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budd, L.; Ison, S. Supporting the Needs of Special Assistance (Including PRM) Passengers: An International Survey of Disabled Air Passenger Rights Legislation. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2020, 87, 101851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budd, T.; Suau-Sanchez, P.; Halpern, N.; Mwesiumo, D.; Bråthen, S. An assessment of air passenger confidence a year into the COVID-19 crisis: A segmentation analysis of passengers in Norway. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 96, 103204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Kumar Bardhan, A.; Fageda, X. What Is Driving the Passenger Demand on New Regional Air Routes in India: A Study Using the Gravity Model. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2022, 10, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saljoqi, M.; Moradi, M.; Ceccato, R.; De Cet, G. Unraveling Passengers’ Preferences: Investigating Airport Access Mode Choice in Tehran, Iran. Transp. Res. Procedia 2024, 78, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.V.M.; Oliveira, B.F.; Vassallo, M.D. Airport Service Quality Perception and Flight Delays: Examining the Influence of Psychosituational Latent Traits of Respondents in Passenger Satisfaction Surveys. Res. Transp. Econ. 2023, 102, 101371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziedzic, M.; Njoya, E.T.; Warnock-Smith, D.; Hubbard, N. Determinants of Air Traffic Volumes and Structure at Small European Airports. Res. Transp. Econ. 2020, 79, 100749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolcha, T.D. Competition in the African Air Transport Market. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2024, 27, 101209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zheng, C.; Chen, X.; Wandelt, S. Multiple Airport Regions: A Review of Concepts, Insights and Challenges. J. Transp. Geogr. 2024, 120, 103974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. Assessing airport ground access by public transport in Chinese cities. Urban Stud. 2019, 57, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malandri, C.; Mantecchini, L.; Postorino, M.N. Airport Ground Access Reliability and Resilience of Transit Networks: A Case Study. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 27, 1129–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akar, G. Ground Access to Airports, Case Study: Port Columbus International Airport. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2013, 30, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birolini, S.; Malighetti, P.; Redondi, R.; Deforza, P. Access Mode Choice to Low-Cost Airports: Evaluation of New Direct Rail Services at Milan-Bergamo Airport. Transp. Policy 2019, 73, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrieza-Galán, J.; Jordá, R.; Gregg, A.; Ruiz, P.; Rodríguez, R.; Sala, M.J.; Torres, J.; García-Albertos, P.; Cantú Ros, O.G.; Herranz, R. A Methodology for Understanding Passenger Flows Combining Mobile Phone Records and Airport Surveys: Application to Madrid-Barajas Airport after the COVID-19 Outbreak. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2022, 100, 102163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Huang, Y.; Liu, J. Study on Travel Behavior Characteristics of Air Passengers in an Airport Hinterland. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2023, 112, 102440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.C. Factors Affecting Airport Access Mode Choice for Elderly Air Passengers. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2013, 57, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kölker, K.; Lütjens, K.; Gollnick, V. Analyzing Global Passenger Flows Based on Choice Modeling in the Air Transportation System. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2024, 115, 102530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colovic, A.; Pilone, S.G.; Kukić, K.; Kalić, M.; Dožić, S.; Babić, D.; Ottomanelli, M. Airport Access Mode Choice: Analysis of Passengers’ Behavior in European Countries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalakou, S.; Moura, F. Analyzing Passenger Behavior in Airport Terminals Based on Activity Preferences. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2021, 96, 102110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Xia, J.; Norman, R.; Hughes, B.; Nikolova, G.; Kelobonye, K.; Du, K.; Falkmer, T. Do Air Passengers Behave Differently to Other Regional Travellers?: A Travel Mode Choice Model Investigation. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2019, 79, 101682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Brigant, A.; Puechmorel, S. Quantization and Clustering on Riemannian Manifolds with an Application to Air Traffic Analysis. J. Multivar. Anal. 2019, 173, 685–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanganila, S.; Keerthana, T.; Tamilzhchelvi, P. Airline Traffic Analysis Using Clustering Method in R Language. Asian J. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2019, 8, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, B. Airport Role Orientation Based on Improved K-Means Clustering Algorithm; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 302. [Google Scholar]

- Dearmon, J.; Taylor, C.; Masek, T.; Wanke, C. Air Route Clustering for a Queuing Network Model of the National Airspace System. In Proceedings of the 14th AIAA Aviation Technology, Integration, and Operations Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA, 16–20 June 2014; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.S.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Cui, Z. Research on Resampling and Clustering Method of Aircraft Flight Trajectory. J. Signal Process. Syst. 2022, 95, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Schonfeld, P. Optimal Clustering Analysis for Airport Parking. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2024, 120, 102659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenggonowati, D.L.; Ulfah, M.; Ekawati, R.; Yusuf, V.A. Organization Clustering Airports Using K-Means Clustering Algorithm. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 673, 012081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žambochová, M. Cluster analysis of world’s airports on the basis of number of passengers handled (case study examining the impact of significant events). Statistika 2017, 97, 74–88. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y. What Is the Busiest Time at an Airport? Clustering U.S. Hub Airports Based on Passenger Movements. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 90, 102931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Christine, T.; Wanke, C. An Airport Clustering Method for Air Traffic Flow Contingency Management. In Proceedings of the 11th AIAA Aviation Technology, Integration, and Operations (ATIO) Conference, including the AIAA Balloon Systems Conference and 19th AIAA Lighter-Than, Virginia Beach, VA, USA, 20–22 September 2011; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; Pei, J.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Z. Analyzing Commercial Aircraft Fuel Consumption during Descent: A Case Study Using an Improved K-Means Clustering Algorithm. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 223, 869–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.H.; Wei, H.H.; Chen, C.L.; Wei, H.Y.; Chen, Y.P.; Ye, Z. A Practical Approach to Determining Critical Macroeconomic Factors in Air-Traffic Volume Based on K-Means Clustering and Decision-Tree Classification. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2020, 82, 101743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Ji, X.; Liu, J. Predicting Aircraft Taxiing Estimated Time of Arrival by Cluster Analysis. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 16, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamsing, P.; Torteeka, P.; Yooyen, S.; Yenpiem, S.; Delahaye, D.; Notry, P.; Phisannupawong, T.; Channumsin, S. Aircraft Trajectory Recognition via Statistical Analysis Clustering for Suvarnabhumi International Airport. In Proceedings of the 2020 22nd International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology (ICACT), Phoenix Park, Republic of Korea, 16–19 February 2020; Volume 2020, pp. 290–297. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern, N.; Mwesiumo, D.; Budd, T.; Suau-Sanchez, P.; Bråthen, S. Segmentation of Passenger Preferences for Using Digital Technologies at Airports in Norway. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2021, 91, 102005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budd, T.; Ryley, T.; Ison, S. Airport Ground Access and Private Car Use: A Segmentation Analysis. J. Transp. Geogr. 2014, 36, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patino-Artaza, H.; Suau-Sanchez, P. What Drives Passengers towards Sustainable Aviation? A Segmentation Study of Travel Behaviour and Environmental Concern in Spain. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2025, 21, 101539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Zhang, N. A Travel Mode Choice Model Using Individual Grouping Based on Cluster Analysis. Procedia Eng. 2016, 137, 786–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, I.W.-Y.; Liang, G.-S.; Yahalom, S. The Fuzzy Clustering Method: Applications in the Air Transport Market in Taiwan. J. Database Mark. Cust. Strateg. Manag. 2003, 11, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitohang, S.; Girsang, A.S. Suharjito Prediction of the Number of Airport Passengers Using Fuzzy C-Means and Adaptive Neuro Fuzzy Inference System. Int. Rev. Autom. Control 2017, 10, 280–287. [Google Scholar]

- Fishburn, R. Reaching the Target Audience: How Can We Encourage Increased Mode Shift If Our Travel Surveys Are Biased Towards Those Already Using Smarter Modes; Bursary Paper for the Transport Planning Society; The Transport Planning Society: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- D’Urso, P.; Massari, R. Fuzzy clustering of mixed data. Inf. Sci. 2019, 505, 513–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezdek, J.C. Pattern Recognition with Fuzzy Objective Function Algorithms. Advanced Application in Pattern Recognition; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1981; p. 272. [Google Scholar]

- Makhalova, E. Fuzzy C—Means clustering in MatLab. In Proceedings of the 7th International Days of Statistics and Economics, Prague, Czech Republic, 19–21 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi, S.E.; Gholian-Jouybari, F.; Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M. A Fuzzy C-Means Algorithm for Optimizing Data Clustering. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 227, 120377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente de Oliveira, J.; Pedrycz, W. Advances in Fuzzy Clustering and Its Applications, Advances in Fuzzy Clustering and Its Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jipkate, B.R.; Gohokar, V.V. A Comparative Analysis of Fuzzy C-Means Clustering and K Means Clustering Algorithms. Int. J. Comput. Eng. Res. 2012, 2, 737–739. [Google Scholar]

- Comi, A.; Cirianni, F.M.M.; Cabras, L. Sustainable Mobility as a Service: A Scientometric Review in the Context of Agenda 2030. Information 2024, 15, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.