Abstract

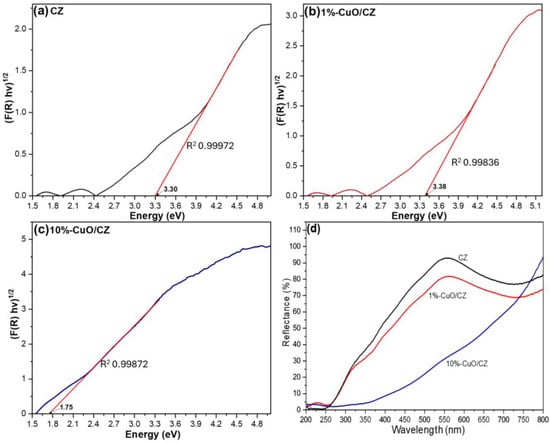

The increasing atmospheric concentration of CO2 is a major contributor to global climate change, underscoring the urgent need for effective strategies to convert CO2 into value-added products. In this sense, a composite was successfully synthesized by combining clinoptilolite zeolite (CZ) with varying amounts of copper oxide (CuO-1% and 10%) for CO2 photoreduction. The composites were characterized using insightful techniques, including XRD, nitrogen physisorption, DRS, and SEM. The results confirmed the incorporation and dispersion of CuO within the CZ support. The XRD analysis revealed characteristic crystalline CuO peaks. Despite the low surface area (<15 m2·g−1) and macroporous nature of the samples, EDS imaging revealed an effective and homogeneous dispersion of CuO, indicating efficient surface distribution. UV–Vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy revealed band gap energies of 3.30 eV (CZ), 3.38 eV (1%-CuO/CZ), and 1.75 eV (10%-CuO/CZ), highlighting the pronounced electronic changes resulting from CuO incorporation. Photocatalytic tests conducted under UVC irradiation (λ = 254 nm) revealed that 10%-CuO/CZ exhibited the highest CO and CH4 production, 35 µmol·g−1 and 3.6 µmol·g−1, respectively. The composite also delivered the highest CO productivity (5.91 µmol·g−1·h−1), approximately 3.5 times that of pristine CZ, in addition to achieving the highest CH4 productivity (0.60 µmol·g−1·h−1). Furthermore, turnover frequency (TOF) analysis normalized per Cu site revealed that CuO incorporation not only enhances total productivity but also improves the intrinsic catalytic efficiency of the active copper centers. Overall, the synthesized composites demonstrate promising potential for CO2 photoreduction, driven by synergistic structural, electronic, and morphological features.

1. Introduction

The development of CO2 conversion technologies is essential in the face of rising greenhouse gas emissions and the urgent need to combat climate change [1,2]. Among the most promising approaches are photoelectrochemical and photocatalytic processes, which not only mitigate environmental impact but also harness renewable energy to convert CO2 into valuable products, such as fuels and chemicals [3,4]. In photocatalysis, a semiconductor material absorbs light energy, which promotes the formation of electron-hole pairs (e−/h+) [5]. These charge carriers drive redox reactions on the photocatalyst surface: electrons in the conduction band (CB) reduce CO2, while holes in the valence band (VB) typically oxidize water, generating protons (H+) and oxygen [6,7].

A central challenge in the development of efficient photocatalysts for CO2 reduction is selecting semiconductor materials that not only offer suitable VB and CB potentials to drive redox reactions but also exhibit strong CO2 adsorption affinity and prolonged charge carrier lifetimes [8,9]. To address these requirements, various strategies have been explored, including doping, particle size control, sensitization, and the construction of composites and heterostructures [10,11]. Integrating semiconductors with structured support has proven effective in enhancing photocatalytic performance by improving substrate adsorption, facilitating charge separation, and increasing thermal stability. Among the most studied supports, zeolites stand out due to their high surface area, thermal robustness, and ion-exchange capacity, making them excellent platforms for dispersing semiconductor nanoparticles and tuning their reactivity [12,13].

Clinoptilolite, a natural zeolite belonging to the heulandite group, is classified as T10O20 according to Gottardi & Galli (1985) [14]. Its crystalline structure consists of a three-dimensional network of interconnected SiO4 and AlO4 tetrahedra, forming channels composed of 8- to 10-membered rings. This porous framework enables efficient ion exchange through mobile cations, which balance the framework’s negative charge. The typical unit cell formula is (X)6(Al6Si30O72)20H2O, where X represents the exchangeable cations [15,16]. Although its composition can vary by geological source, the predominant elements include silicon, aluminum, calcium, sodium, and potassium. Due to its high porosity, ion-exchange capacity, and excellent thermal and chemical stability, clinoptilolite finds broad use in environmental applications, such as photocatalysis and industrial applications [17,18,19].

The integration of semiconductors into zeolite matrices significantly enhances photocatalytic performance. Zeolites contribute to this process not only by serving as high surface area supports but also through their intrinsic acidic and basic sites, which facilitate CO2 adsorption and activation [20,21,22]. For instance, CuO, an indirect band gap semiconductor (~1.7 eV), can form a heterojunction with clinoptilolite [23,24,25], effectively suppressing electron-hole recombination and enhancing the generation of reactive species. This synergistic interaction improves both the efficiency and selectivity of photocatalytic reactions, offering a promising strategy for the development of advanced catalysts for sustainable chemical transformations [26,27,28]. In this study, we propose the use of clinoptilolite zeolite combined with CuO for the development of composite materials aimed at CO2 photoreduction. Composites were synthesized via the coprecipitation method with two different CuO loadings: 1% and 10% (w/w). In addition, we explored their physicochemical properties, including surface area, band gap, and particle morphology, to assess the influence of CuO incorporation on the structure and photocatalytic behavior of the composites under ultraviolet irradiation to simulate artificial photosynthesis. The photocatalytic tests revealed that both CuO-containing composites were effective in converting CO2 into CH4, CO, and short-chain alcohols (methanol and ethanol), with the 10% CuO composite achieving the highest production of gaseous and liquid products.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Composite Synthesis

The composites were synthesized by dispersing 2 g of natural clinoptilolite zeolite in 100 mL of water, followed by the addition of a specific amount of copper nitrate (Cu(NO3)2·6H2O—NEON Corporation Ltd., Suzano, SP, Brazil) to achieve CuO loadings of 1% and 10% relative to the zeolite mass. The mixture was heated to 100 °C under continuous stirring. Subsequently, a 1 mol/L sodium hydroxide (NaOH—NEON Corporation Ltd., Suzano, SP, Brazil) solution was gradually added until the pH reached 13. The system was stirred for 30 min then washed thoroughly with ethanol and water. The resulting material was dried in an oven at 80 °C for 12 h. The composites were designated based on their copper content, 1%-CuO/CZ and 10%-CuO/CZ, while the commercial clinoptilolite zeolite was labeled as CZ.

2.2. Characterization

The materials were characterized using a range of analytical techniques. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded on a Rigaku Ultima IV with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.15406 nm) at a scanning rate of 0.5° min−1 over a 2θ range of 5–50°. Copper content was quantified via atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS) using a PerkinElmer PinAAcle 900T (PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), with a synthetic air/acetylene flame (10 mL/2.5 mL) mixture. Measurements were performed using a hollow cathode lamp with the emission at 324.75 nm. Morphological analysis was performed by field emission SEM (JEOL JSM 6510, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Thermogravimetric analyses characterized all materials were performed on an SDT 650 analyzer (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA), using 10 mg samples in a platinum crucible under a nitrogen atmosphere (60 mL min−1) and a temperature range of 25–550 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C min−1. Bandgap energies were estimated by the Tauc Plot method using DRS data (obtained from a Shimadzu UV-2600 spectrophotometer, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). Infrared spectra were acquired on a Bruker VERTEX 70 spectrophotometer (Bruker Optics GmbH, Ettlingen, Germany) in the 4000–400 cm−1 range. The isotherm N2 adsorption/desorption was performed on a Quantachrome NOVA 4200E analyzer (Quantachrome Instruments, Boynton Beach, FL, USA) at 77 K, after degassing at 80 °C for 12 h. The specific surface area was determined by the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) equation.

2.3. CO2 Photoreduction Reactions

For the CO2 photoreduction experiments, batch quartz tube reactors with a total volume of 144 mL were used, each equipped with a septum for gas sampling and capillary inlets and outlets fitted with valves for CO2 purging (see Supplementary Materials Figure S1). After 10 min of CO2 purging, both inlet and outlet valves were closed, establishing a closed batch system for photoreduction reaction. To maintain a homogeneous reaction environment and control the reaction temperature, the tubes were placed inside a temperature-controlled chamber coupled to a magnetic stirring system. Thermal regulation was achieved by forced air circulation combined with a continuous water flow circulating through the walls of the chamber, ensuring efficient heat dissipation during irradiation. The reactions were irradiated with UV-C light using six Philips TUV 15W SLV/25 lamps (λ = 254 nm). Prior to irradiation, high-purity CO2 was purged into the system for 10 min to ensure saturation of the suspension, which was prepared by dispersing 100 mg of the photocatalyst in 100 mL of distilled water. After 6 h of illumination, gas-phase aliquots (400 μL) were collected through the septum and manually injected into an Agilent 8860 GC System Custom gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a Carboxen 1010 PLOT capillary column (Supelco (Merck KGaA), Bellefonte, PA, USA). After chromatographic separation, the gases were detected by flame ionization (FID) and thermal conductivity (TCD) detectors. All analyses were performed in duplicate to ensure consistency and reproducibility. Hydrogen nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H NMR) was applied to analyze the water-dissolved compounds. The measurements were acquired on a Nuclear Magnetic spectrometer (Bruker 600 MHz NMR, Ascent 600 model, Bruker BioSpin GmbH, Rheinstetten, Germany) at 25 °C. Prior to data collection, a protocol for attenuating the water resonance signal was applied. Each sample (540 µL) was combined with 60 µL of a D2O solution containing DMSO (2.36 mM), the latter was the internal standard. The resulting spectra was processed with MestreNova software (version 14.2.3).

The number of electrons involved in the CO2 photoreduction process was estimated from the stoichiometric electron requirements of each reaction pathway. Product formation values (µmol·g−1) were multiplied by the corresponding number of electrons necessary for the reduction of CO2 to each compound: 2 e− for CO, 6 e− for CH3OH, 8 e− for CH4, 12 e− for C2H5OH, and 8 e− for acetate. The total number of electrons involved (µmol e−·g−1) was obtained by multiplying the amount of each product (µmol·g−1) by its corresponding electron requirement and summing the contributions of all products:

where is the amount (µmol·g−1) of each species produced.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization

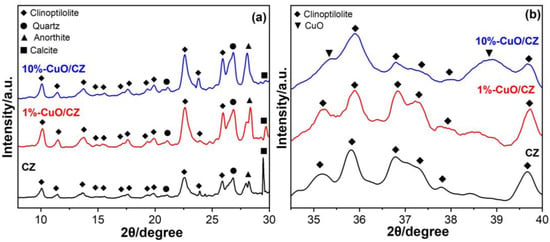

Figure 1a displays the XRD patterns for both pristine and CuO-modified clinoptilolite, in the 10–30° 2θ range, where the presence of the crystalline phase of clinoptilolite and common impurities can be assessed. The unmodified zeolite shows diffraction peaks characteristic of clinoptilolite (JCPDS #79–1462), confirming its crystalline structure, along with additional peaks attributed to quartz (JCPDS #1–649), anorthite (JCPDS #2–537), and calcite (JCPDS #24–27), typical impurities from mineralogical complexity of natural clinoptilolite sources, which often include aluminosilicate and carbonates. EPR spectra (Figure S2) also support the presence of impurities; a very broad line at low magnetic field is observed, indicating strong exchange interactions between paramagnetic species. In addition, six characteristic hyperfine transitions of Mn2+ are clearly visible in the region near g ≈ 2.00, which result from the coupling between the unpaired d-electrons and the nuclear spin of 55Mn (I = 5/2). This signal, typically isotropic, exhibits a g-factor close to 2.00 and confirms the presence of Mn2+ ions well isolated in the aluminosilicate framework. The use of EPR is particularly important because it reveals impurities that are often undetectable by conventional techniques such as EDS and XRD, especially when present at very low concentrations or in structurally disordered environments. Comparing the CZ with the CuO-bearing composites, spectral differences are observed, indicating that the NaOH used in the co-precipitation has an effect on the impurities’ removal, evidenced by the decreased intensity of the broad line and the narrowing in the line width of the Mn2+ centers. CuO-modified composites have secondary phases as well. However, the prominent calcite peak at approximately 29.5° appears diminished, suggesting partial leaching of calcium carbonate during synthesis. Furthermore, distinct peaks corresponding to CuO (JCPDS #48–1548), associated with the (002) and (111) planes near 35.5° and 38.8°, are visible only in the diffractogram of the 10%-CuO/CZ composite (Figure 1b). These peaks are absent in the 1%-CuO/CZ sample, likely due to the lower copper content, which may fall below the XRD detection limit.

Figure 1.

X-ray diffraction patterns of commercial clinoptilolite (CZ) and the synthesized CuO/CZ composites. (a) Diffraction patterns recorded in the 2θ range of 5–30°. (b) Enlarged view of the diffractograms in the 2θ range between 30–40°, highlighting the region associated with CuO.

To complement the phase identification obtained by XRD, the copper incorporation efficiency in the CuO/CZ composites was also quantified. Although the diffractograms confirm the presence of CuO reflections only for the higher-loading sample (10%-CuO/CZ), chemical analysis provides a more accurate assessment of the actual copper content introduced during synthesis. The composites were synthesized by combining Cu2+ precursors with CZ via a coprecipitation route, in which Cu(OH)2 initially precipitates upon NaOH addition and subsequently undergoes thermal conversion to CuO in the aqueous medium at approximately 100 °C. Atomic absorption spectroscopy revealed that the effective copper loadings (0.6% for 1%-CuO/CZ and 3.5% for 10%-CuO/CZ) were lower than the nominal values, indicating partial removal of weakly bound or non-incorporated copper species during the washing steps.

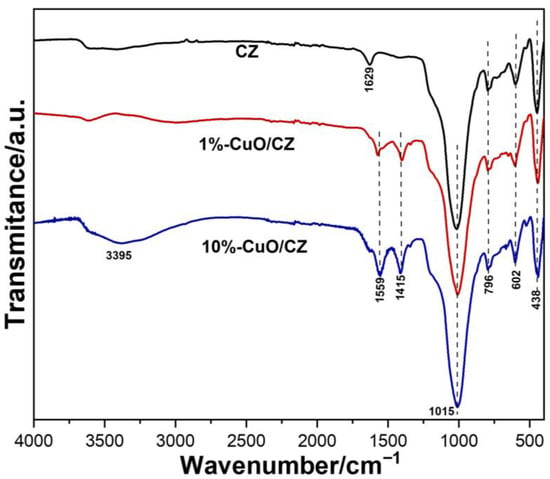

The structural features of the CZ and its composites were further examined using FTIR spectroscopy (Figure 2). The spectrum of commercial CZ exhibited a strong and broad absorption band near 1015 cm−1, attributed to asymmetric stretching vibrations of Si–O–Si, Al–O–Al, and Al–O–Si linkages [22]. Additional characteristic zeolite bands were observed at 796 cm−1 (symmetric stretching of Si–O–Si and Si–O–Al), 602 cm−1 (vibrations of double rings within the zeolite framework), and approximately 438 cm−1 (bending vibrations of SiO or Al–O) [29]. The CZ spectrum also exhibited a band at 1629 cm−1, corresponding to the deformation vibrations of water molecules structurally integrated within the zeolite [30]. However, two new absorptions at 1559 and 1415 cm−1, absent in pristine CZ, were observed and are attributed to acetate groups present on the CuO surface, originating from the copper precursor used in the synthesis, as previously verified in related studies of the group [31,32,33]. The presence of these species confirms the incorporation of copper oxide into the CZ/CuO-1% composite, even though no CuO-related peaks were detected in its XRD pattern due to the low loading.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of pristine CZ and CuO/CZ composites.

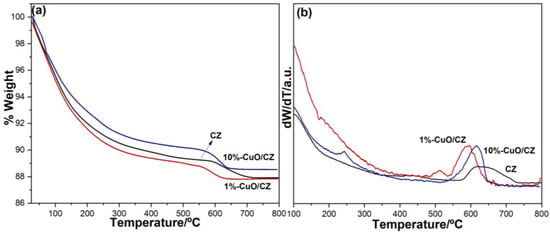

To assess the thermal stability of the zeolite-based materials, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was conducted, as shown in Figure 3a. The sample 10%-CuO/CZ exhibited a lower mass loss after 200 °C compared to both CZ and 1%-CuO/CZ This difference, sustained throughout the entire thermal profile, suggests that the higher copper loading reduced the water retention capacity of the CZ, likely due to the occupation of hydrophilic sites by CuO particles. In contrast, the 1%-CuO/CZ sample displayed thermal behavior nearly identical to that of CZ up to around 550 °C, indicating that, within this temperature range, the lower CuO content did not significantly alter interactions with water or surface functionalities. However, beyond 550 °C, both CuO-containing samples exhibited a more pronounced mass loss not observed in the CZ, as evidenced by the DTG curves in Figure 3b. Specifically, the modified materials presented sharper peaks between 550 and 650 °C, while the CZ sample showed a broader thermal event extending from 580 to 740 °C. This broad feature is consistent with the dehydroxylation of the clinoptilolite framework and the decomposition of residual carbonate species [34,35]. The sharper DTG peaks observed in the copper-loaded samples may be attributed to the decomposition of basic copper carbonate, which was identified by FTIR spectroscopy and typically decomposes at lower temperatures than calcium carbonate [36]. Alternatively, the presence of copper may influence the thermal stability of the material by catalyzing the decomposition of surface groups or enhancing dehydroxylation processes.

Figure 3.

(a) Thermogravimetric analysis and (b) DTG of pristine CZ and CZ/CuO composites.

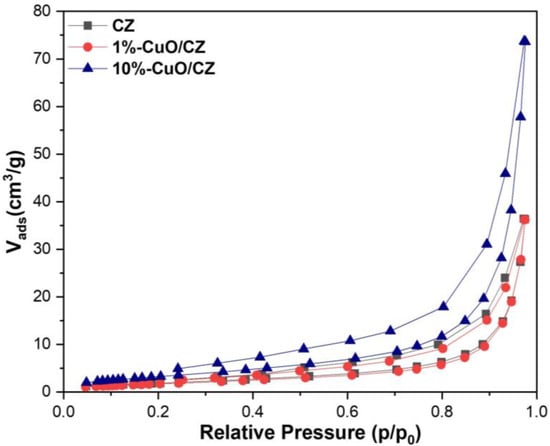

The nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms (Figure 4) of CZ and CuO/CZ composite exhibited a steep increase in nitrogen uptake at high relative pressures, characteristic of Type III isotherms, typically associated with nonporous or macroporous materials according to IUPAC classification. The absence of a pronounced hysteresis loop and the low BET surface areas further support the dominance of macroporosity or external surface adsorption. The specific surface areas of the materials, determined by the BET method, were generally low, all below 15 m2·g−1 (14 m2·g−1, 0.8 m2·g−1, and 2.3 m2·g−1 for CZ, 1%-CZ/CuO, and 10%-CZ/CuO, respectively) which is consistent with previously reported values for CZ in the range of 14–19 m2·g−1 [37]. After copper incorporation, no significant decrease in surface area was observed. This suggests a high dispersion of CuO species across the CZ surface, likely in the form of ultrafine particles or clusters that do not substantially block the pores or reduce the accessible surface area. The high dispersion of CuO may indicate a strong interaction between the copper precursor and the surface functional groups of CZ, favoring uniform distribution rather than aggregation. This uniform dispersion is beneficial for photocatalytic applications, as it increases the number of active sites while maintaining surface accessibility.

Figure 4.

Nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms.

The literature presents varying results regarding the effect of metal incorporation on surface morphology. While some studies report negligible changes in surface area upon metal incorporation, others have observed either a reduction or even an increase, depending on the preparation method [38,39]. For example, in the case of CuO/TiO2 composites, no significant decrease in surface area was reported, suggesting a high dispersion of CuO species across the support surface [40]. In contrast, studies have been conducted on MCM-41-based composites with varying metal loadings, specifically containing copper oxide (via coprecipitation) and iron oxide (via impregnation) [38,39]. It was reported that the metal-modified materials had lower surface areas compared to the pure MCM-41 support; however, the composites with higher metal content also showed increased surface area and pore volume relative to those with lower loading.

As previously discussed, evaluating the band gap of photocatalysts intended for CO2 reduction is a critical step. Photocatalytic CO2 reduction involves redox reactions that occur within a potential window of approximately −1.5 to +1.5 eV. Therefore, it is essential not only for the material to have a sufficiently narrow band gap to be activated by light but also for the band gap to align with the energy range required for these reactions [9].

Figure 5 shows the estimated band gap values for CZ and its CuO-based composites. It is important to note that clinoptilolite is an aluminosilicate insulator, and therefore the value obtained from the Tauc-Kubelka-Munk analysis corresponds to an apparent optical band gap, associated with defect-related or edge-type electronic transitions rather than a true semiconductor band structure. Nevertheless, this apparent band gap is relevant for assessing changes in the optical absorption profile upon CuO incorporation.

Figure 5.

Band gap determination for (a) CZ, (b) 1%-CuO/CZ, and (c) 10%-CuO/CZ; (d) corresponding diffuse reflectance spectra.

The CZ and 1%-CuO/CZ samples displayed similar apparent band gap energies of 3.30 eV and 3.38 eV, respectively, indicating that a low CuO loading does not significantly perturb the optical response of the clinoptilolite framework. At this concentration, Cu species are likely dispersed as isolated Cu(II) centers or very small clusters, which contribute only marginally to the absorption edge.

The excitation of the pristine zeolite under the experimental photocatalytic conditions is feasible given that the lamp used in the reactions exhibits its most intense emission line at 254 nm (~4.88 eV), which matches one of the strongest absorption bands typically observed in zeolites. This spectral overlap enables UV excitation of defect sites or extra-framework species, providing a plausible pathway for the limited intrinsic photoactivity often observed in natural zeolites. This consideration is particularly relevant for interpreting the photocatalytic results presented in the following section.

In contrast to the low-loading composite, the 10%-CuO/CZ material exhibits a pronounced band gap reduction to 1.75 eV. This decrease is attributed to the higher CuO content, whose intrinsic band gap (1.7–2.9 eV) increasingly dominates the optical response of the hybrid system [41]. Moreover, the formation of interfacial Cu-O-Si/Al linkages at higher loadings can modify the local electronic environment and introduce intermediate energy states within the composite, thereby enhancing visible-light absorption. Together, these effects explain the substantial narrowing of the band gap in 10%-CuO/CZ and support the role of the CuO/CZ interface in improving light harvesting and charge separation efficiency.

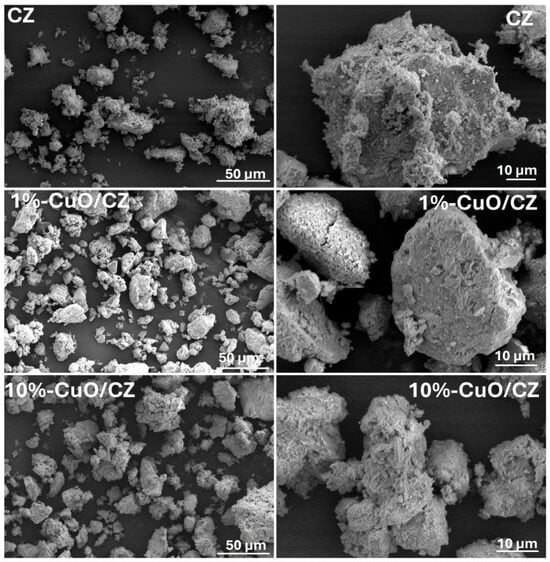

Figure 6 presents SEM images of the samples, showing that all materials consist of irregularly shaped agglomerates, with no well-defined morphology. The incorporation of CuO at both 1 wt% and 10 wt% does not lead to noticeable changes in particle structure or surface features. Additionally, no distinct CuO particles are observed on the surface, suggesting a homogeneous dispersion of copper oxide within the CZ matrix. Further compositional analysis is provided by the SEM–EDS maps shown in Figures S3 and S4 (Supplementary Materials). The mapping of the commercial CZ confirms the presence of C, O, Al, Si, Na, and Mg. For the 10%-CuO/CZ composite, Cu was not detected in the EDS map, which can be explained by the low Cu content. In fact, atomic absorption spectroscopy confirmed the presence of Cu at 0.6 wt%. In contrast, the 10%-CuO/CZ sample exhibited a clear Cu distribution in the EDS map, consistent with its higher loading. These results demonstrate the successful incorporation of CuO into the CZ framework, while also highlighting the detection limits of EDS for low-concentration elements.

Figure 6.

SEM images of CZ and 1%-CuO/CZ, and 10%-CuO/CZ composites.

3.2. Photocatalytic Tests

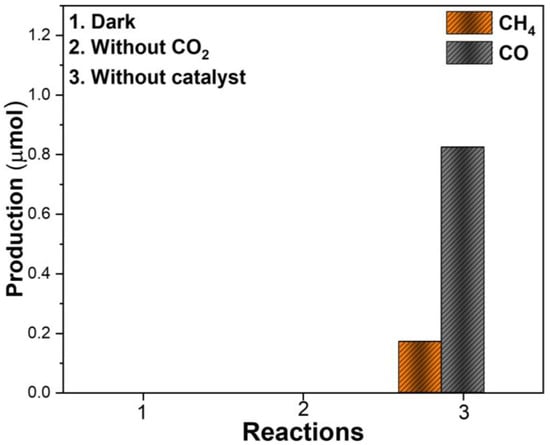

To assess whether there was formation of products unrelated to the photocatalytic activity of the synthesized materials, three control experiments were performed: (i) under dark conditions, (ii) in the absence of CO2, and (iii) without a catalyst (Figure 7). As expected, no detectable products were observed in the first two cases, confirming that both light irradiation and CO2 are essential for the reaction and that there is no organic contamination that could mask CO2 reduction results. However, in the absence of a catalyst, a minor amount (<1 µmol) of CH4 and CO was detected. This result suggests that a small fraction of the CO2 can undergo reduction due to radical reactions initiated by UVC illumination, leading to trace formation of gaseous products even without the photocatalytic material.

Figure 7.

Control experiments were carried out under dark conditions, in the absence of CO2, and without a catalyst at 6 h of reaction.

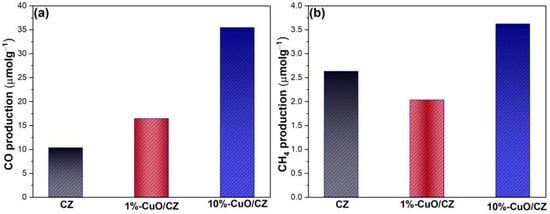

Figure 8 and Table 1 present the photocatalytic performance of the synthesized materials in the CO2 photoreduction process, highlighting the generation of CO and CH4 as the predominant gaseous reduction products. Notably, CuO plays a crucial role in CO2 photoreduction, particularly in enhancing CO production. Among the tested photocatalysts, 10%-CuO/CZ exhibited the highest activity, achieving 35.44 µmol·g−1 of CO and 3.62 µmol·g−1 of CH4 after 6 h. The amount of CO produced is approximately 3.5 times higher than that of pristine CZ. In contrast, 1%-CuO/CZ showed moderate performance, with 18 µmol·g−1 of CO and 2.03 µmol·g−1 of CH4. While the pure CZ sample produced only 10 µmol·g−1 of CO, it generated a slightly higher amount of CH4 (2.63 µmol·g−1) compared to 1%-CuO/CZ, indicating that CuO incorporation primarily promotes CO formation. These results indicate that CuO dispersion and the interaction with the CZ matrix are more favorable in the 10%-CuO/CZ sample, significantly improving photocatalytic efficiency. Additionally, the superior performance of 10%-CuO/CZ may also be attributed to its higher macroporosity compared to 1%-CuO/CZ, which likely facilitates more efficient mass transport of reactants and products during the photocatalytic process. This result is consistent with findings in the literature, where CuO is recognized as a promising photocatalyst due to its suitable electron donor properties and favorable band structure for CO2 reduction [42].

Figure 8.

Photocatalytic CO2 reduction performance of the synthesized catalysts. (a) CO and (b) CH4 production.

Table 1.

Total product amounts (µmol·g−1) and corresponding productivities normalized by reaction time (µmol·g−1·h−1) for gaseous and liquid products formed during CO2 photoreduction over CZ and CuO/CZ catalysts after 6 h of irradiation.

Water molecules can also enhance CO2 adsorption through hydrogen bonding interactions, improving the activation of CO2 on the photocatalyst surface [43]. Following the initial formation of CO, these interactions may also support the subsequent hydrogenation steps that lead to CH4 production [42]. Thus, CO production is favored in the material with higher CuO content, with the catalytic activity being modulated by the presence of a reversible Cu+/Cu2+ redox couple, resulting from modifications in the local chemical environment [44]. The interconversion of copper species, influenced by the reaction environment, may account for the formation of distinct products. In this context, Cu+ sites are often proposed to serve as active centers for the initial reduction of CO2 to CO. The resulting CO can then undergo hydrogenation to yield the CHO intermediate, which is subsequently reduced via electron and proton transfer, ultimately leading to CH4 formation [44].

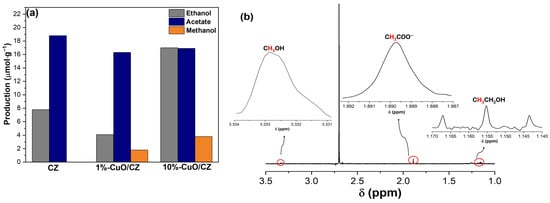

The liquid phase of the photocatalytic CO2 reduction was analyzed by 1H NMR at 6 h of reaction, revealing the formation of three main products: ethanol, acetate, and methanol (Figure 9). Among them, acetate was the predominant product for the pristine CZ sample (18.8 µmol·g−1), followed by ethanol (7.8 µmol·g−1), while no detectable amount of methanol was observed. The incorporation of 1% CuO into CZ resulted in a decrease in ethanol production (4.1 µmol·g−1) but enabled the formation of methanol (1.8 µmol·g−1), while acetate remained at comparable levels (16.3 µmol·g−1). Notably, the photocatalysts 10%-CuO/CZ exhibited the highest ethanol production (17 µmol·g−1), accompanied by 3.8 µmol·g−1 of methanol and 16.9 µmol·g−1 of acetate. These results suggest that the presence of CuO significantly influences the selectivity of the liquid-phase products, favoring the generation of alcohols, particularly ethanol and methanol, at higher CuO contents. At the same time, acetate formation remains relatively stable across all catalysts.

Figure 9.

Liquid-phase products obtained from photocatalytic CO2 reduction over CZ and CuO/CZ catalysts after 6 h of reaction. (a) Quantification of ethanol, acetate, and methanol. (b) Representative 1H NMR spectrum evidencing the characteristic signals of the identified products.

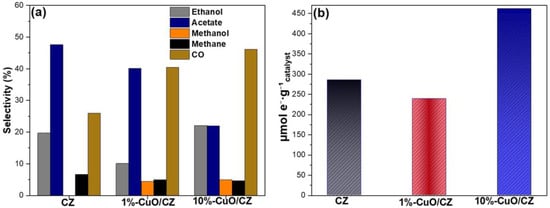

The selectivity of the photocatalytic CO2 reduction process revealed significant differences depending on the catalyst composition (Figure 10). For the pristine CZ sample, acetate was the predominant product (47.6%), followed by CO (26.0%) and ethanol (19.7%), whereas no methanol formation was detected. The incorporation of 1% CuO modified the product distribution, decreasing acetate selectivity to 40.1% and ethanol to 10.1%, while favoring the formation of methanol (4.4%) and increasing CO selectivity to 40.4%. This indicates that the presence of CuO facilitates electron transfer processes that enhance CO generation and promote the reduction pathway toward methanol.

Figure 10.

(a) Selectivity of the liquid- and gas-phase products formed during photocatalytic CO2 reduction over CZ and CuO/CZ catalysts. (b) Total number of electrons involved in the CO2 photoreduction process at 6 h of reaction.

At higher CuO loading, a pronounced shift in selectivity was observed, with ethanol becoming the major product (22.1%), followed by CO (46.2%) and acetate (22.0%). Conversely, methanol and CH4 had low selectivity values (5.0% and 4.7%, respectively). These results suggest that the CuO content plays a crucial role in modulating the reaction pathways: while pristine CZ tends to favor acetate formation, the addition of CuO enhances CO generation and, at higher loadings, shifts the selectivity toward alcohol production, particularly ethanol. This behavior may be associated with the improved charge separation and enhanced surface redox properties imparted by CuO, which favor multi-electron/proton transfer reactions required for alcohol synthesis.

In addition to product quantification, photocatalytic efficiency can also be evaluated by the total number of electrons involved in the CO2 reduction reaction per gram of photocatalyst. The 10%-CuO/CZ sample exhibited the highest electron participation, with 461.84 µmol e−·g−1, confirming its superior ability to generate and transfer photogenerated electrons under UV illumination. In contrast, pristine CZ and 1%-CuO/CZ showed significantly lower values, with 285.64 and 239.08 µmol e−·g−1, respectively. These results corroborate the product distribution trends and reinforce the beneficial role of CuO, particularly at higher loading, in promoting effective charge separation and enhancing electron mobility, thereby increasing the number of electrons available for CO2 photoreduction [45].

The selectivity observed in the liquid and gaseous products of CO2 photoreduction varied significantly with the catalyst composition (Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10). For CZ, the major liquid-phase product was acetate (18.8 μmol·g−1), followed by ethanol (7.8 μmol·g−1), with no detectable methanol formation. This behavior can be attributed to the macroporous surface structure of CZ, which, despite its relatively low specific surface area, provides Brønsted and Lewis acid sites capable of adsorbing and activating CO2 [46]. At these sites, CO2 is stabilized as carbonate/bicarbonate intermediates, which can undergo successive reductions and favor C–C coupling, ultimately leading to acetate formation [47]. The predominance of this product suggests that, in the absence of metallic redox species, the catalytic pathway is governed by the acidic centers of the zeolite, which prolong the residence time of intermediates and facilitate condensation between *CO and *CHX species.

Upon incorporation of CuO into the structure (1%-CuO/CZ and 10%-CuO/CZ) a clear shift in product distribution was observed. In 1%-CuO/CZ, ethanol formation decreased (4.1 μmol·g−1), while methanol emerged (1.8 μmol·g−1), and acetate remained at a level comparable to that of pure CZ (16.3 μmol g−1). This indicates that small amounts of CuO promote water dissociation and the generation of reactive hydrogen, but the limited dispersion of CuO is insufficient to redirect the dominant reaction pathway, which remains governed by the acidic sites of the zeolite [48,49].

In contrast, for 10%-CuO/CZ, the scenario changes markedly: ethanol production increased significantly (17 μmol·g−1), accompanied by methanol (3.8 μmol·g−1), while acetate remained nearly constant (16.9 μmol·g−1). This shift in selectivity can be ascribed to the presence of highly dispersed Cu+/Cu2+ redox sites, which serve as active centers for CO2 conversion to CO and, subsequently, for its sequential hydrogenation into alcohols [22]. Unlike pure CZ, where C2 products arise from the coupling of activated intermediates at acidic sites, in 10%-CuO/CZ the predominant route involves multi-electron hydrogenation of adsorbed CO, yielding ethanol as the main liquid product. This hypothesis is supported by the higher number of electrons transferred (461.84 μmol e−·g−1), demonstrating that CuO enhances the efficiency of photogenerated charge separation and increases the number of electrons available for reduction reactions.

Comparison with other CuO-modified zeolitic systems reported in the literature further substantiates this interpretation. In MCM-41/CuO materials, for instance, increasing CuO content enhanced selectivity toward alcohols (mainly methanol), attributed to the role of Cu in stabilizing *CH3O and *CH2OH intermediates [22]. Similarly, in CuO-modified zeolite A, the coexistence of zeolite acid sites and copper redox centers favored the formation of C2 compounds, including ethanol and ethylene. Therefore, the transition from acetate selectivity in pure CZ to ethanol selectivity in 10%-CuO/CZ can be attributed to the synergy between the macroporous CZ structure, which ensures reactant accessibility, and CuO redox sites, which introduce alternative hydrogenation pathways.

The TOF based on the number of electrons transferred per active Cu site was calculated by considering the actual Cu content in each catalyst and the total number of electrons involved in the photoreduction process over 6 h of reaction. For 1%-CuO/CZ, which contained 0.6 mg of Cu, the total number of electrons generated was 23.91 µmol, resulting in a TON of 2.53 e− per mol of Cu and a corresponding TOF of 0.42 h−1. In contrast, 10%-CuO/CZ, with a higher Cu content (3.6 mg), produced 46.18 µmol of electrons, corresponding to a TON of 0.815 and a TOF of 0.14 h−1. These findings show that, although 10%-CuO/CZ contains a greater absolute amount of Cu and generates more total electrons, its intrinsic efficiency per Cu site is significantly lower than that of 1%-CuO/CZ. Therefore, 1%-CuO/CZ exhibits superior Cu-normalized catalytic efficiency, indicating more effective utilization of active sites and a more favorable electron transfer dynamics.

4. Conclusions

The incorporation of CuO into the clinoptilolite matrix significantly enhanced both the efficiency and selectivity of CO2 photoconversion. The 10%-CuO/CZ composite displayed superior charge separation and electron availability, resulting in a substantial increase in CO formation and the selective production of alcohols (ethanol and methanol), whereas pristine CZ predominantly favored the formation of acetate. These findings highlight the synergistic interplay between the zeolite framework and the Cu-based redox centers, which promotes electron transfer and modulates reaction pathways. Notably, the TOF analysis normalized per Cu site confirmed that, despite differences in the total Cu content, the CuO-modified materials exhibit distinct intrinsic efficiencies, further supporting the role of copper active centers in governing electron transfer dynamics. Overall, the performance achieved demonstrates the potential of CuO–zeolite composites as a promising platform for the rational design of selective photocatalysts for CO2 conversion.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/photochem6010003/s1, Figure S1: Photograph of the reaction system used in the CO2 photoreduction experiments and schematic representation of the experimental setup, Figure S2: EPR spectra of (a) CZ, (b) CZ/CuO-1% and (c) CZ/CuO-10%. The right side is the expansion of the spectra region limited by the frame, Figure S3: Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping (C, O, Al, Na, Si, and Cu) of CZ/CuO 1%, CZ/CuO 5%, and CZ/CuO 10% composites, Figure S4: Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy analysis of the CZ (a), 1%-CuO/CZ (b), and 10%-CuO/CZ (c); Table S1: Weight percentages of all components of the CZ, Table S2: Weight percentages of all components of the 1%-CuO/CZ, Table S3: Weight percentages of all components of the 10%-CuO/CZ.

Author Contributions

F.L.S.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, formal analysis, investigation, Data curation, Writing—original draft preparation, Writing—review and editing, Visualization. J.B.G.F.: Methodology, formal analysis, Data curation, Writing—review and editing, and Visualization; V.M.F.S.: Methodology, Investigation, formal analysis, Data curation, Writing—review and editing; K.F.: Methodology, formal analysis, Data curation, Writing—review and editing; M.G.: Methodology, formal analysis, Data curation, Writing—review and editing and Visualization; J.A.T.: Methodology, formal analysis, Data curation, Writing—review and editing and Visualization; A.S.G.: Methodology, formal analysis, Data curation, Writing—review and editing and Visualization; L.S.R.: Methodology, formal analysis, Data curation, Writing—review and editing; L.B.: Methodology, formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—review and editing; C.R.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Resources, Writing—review and editing and Supervision; A.E.N.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, formal analysis, investigation Resources, Writing—original draft preparation, Writing—review and editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the São Paulo Research Foundation-FAPESP, grant number 2023/17686-4, 2023/10329-1 and 2017/11986-5, by National Council for Scientific and Technological Development-CNPq, grant number 308823/2022, 406860/2022-0, 406925/2022-4 and 407878/2022-0, by CAPES (Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel—Finance Code 001) and by Funding Authority for Studies and Projects (FINEP, grant number 01.24.0554.00).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alli, Y.A.; Bamisaye, A.; Bamidele, M.O.; Etafo, N.O.; Chkirida, S.; Lawal, A.; Hammed, V.O.; Akinfenwa, A.S.; Hanson, E.; Nwakile, C.; et al. Transforming waste to wealth: Harnessing carbon dioxide for sustainable solutions. Results Surf. Interfaces 2024, 17, 100321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Malek, A.; Teo, S.H.; Marwani, H.M.; Rahman, M.M.; Asiri, A.M.; Khan, M.A.R.; Taufiq-Yap, Y.H.; Awual, M.R. Smart materials for CO2 conversion into renewable fuels and emission reduction. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2023, 37, e00636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Sun, Z.; Lim, K.H.; Gani, T.Z.H.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Yin, H.; Liu, K.; Guo, H.; Du, T.; et al. Emerging Strategies for CO2 Photoreduction to CH4: From Experimental to Data-Driven Design. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2200389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Yuan, J.; Su, Y.; Ma, L.; Liu, J.; Ren, M.; Huang, S.; Liu, Y. Enhanced photo-electrochemical reduction of CO2 into methanol at CuInS2/CuFeO2 thin-film photocathodes with synergistic catalysis of oxygen vacancy and S–O bond. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 648, 159033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, R.; Romero, R.; Amado-Piña, D. Cu/TiO2 Photo-catalyzed CO2 Chemical Reduction in a Multiphase Capillary Reactor. Top. Catal. 2024, 67, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.; Lopes, O.; Dias, E.; Torres, J.; Nogueira, A.; Faustino, L.; Prado, F.; Patrocínio, A.; Ribeiro, C. Redução de CO2 em Hidrocarbonetos e Oxigenados: Fundamentos, Estratégias e Desafios. Quim. Nova 2021, 44, 963–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, I.; Garg, S.; Sapi, A.; Ingole, P.P.; Chandra, A. Insights into photocatalytic CO2 reduction reaction pathway: Catalytic modification for enhanced solar fuel production. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2024, 137, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Q.; Wang, W.; Hao, N.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Luo, D. Recent advances in novel materials for photocatalytic carbon dioxide reduction. Carbon Neutralization 2024, 3, 142–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, A.E.; Ribeiro, L.S.; Geovo, J.D.C.; Neto, F.N.S.; Fragal, V.H.; Sequinel, T.; Camargo, E.R.; Gorup, L.F. The Chemistry of CO2 Reduction Processes: Mechanisms, Challenges, and Perspectives. In Handbook of Energy Materials; Gupta, R., Ed.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Q.; Li, L.; Gao, W.; Shen, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Shen, Q.; Xiong, Y.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Elegant Construction of ZnIn2S4/BiVO4 Hierarchical Heterostructures as Direct Z-Scheme Photocatalysts for Efficient CO2 Photoreduction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 15092–15100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, B.; Cui, W.; Chen, P.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Dong, F. C–Doping Induced Oxygen-Vacancy in WO3 Nanosheets for CO2 Activation and Photoreduction. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 9670–9678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Yang, J.; Duan, X.; Farnood, R.; Yang, C.; Yang, J.; Liu, W.; Liu, Q. Recent developments and challenges in zeolite-based composite photocatalysts for environmental applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 417, 129209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, M.; Guo, Y.; Wu, Z. Recent Advances in the Synthesis and Photoelectrocatalysis of Zeolite-Based Composites. Catalysts 2024, 14, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottardi, G.; Galli, E. Natural Zeolites; Minerals, Rocks and Mountains Series 18; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; p. 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, D.A.; Tezel, F.H. Cation exchange modification of clinoptilolite—Screening analysis for potential equilibrium and kinetic adsorption separations involving methane, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide. Microporous Mesoporous Mat. 2018, 262, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reháková, M.; Čuvanová, S.; Dzivák, M.; Rimár, J.; Gaval’ová, Z. Agricultural and agrochemical uses of natural zeolite of the clinoptilolite type. Curr. Opin. Solid. State Mater. Sci. 2004, 8, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifasi, N.; Ziantoni, B.; Fino, D.; Piumetti, M. Fundamental properties and sustainable applications of the natural zeolite clinoptilolite. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 32, 27805–27840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whaieb, A.H.; Jasim, F.T.; Abdulrahman, A.A.; Khuder, I.M.; Gheni, S.A.; Fattah, I.M.R.; Karakullukcu, N.T. Tailoring zeolites for enhanced post-combustion CO2 capture: A critical review. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2025, 10, 100451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, M.R.; Othman, M.H.D.; Hubadillah, S.K.; Aziz, M.H.A.; Jamalludin, M.R. Application of natural zeolite clinoptilolite for the removal of ammonia in wastewater. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, (Corrected Proof, in press). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Qi, R.; Sun, X.; Kawazoe, N.; Chen, G.; Yang, Y. Synthesis and characterization of 3D-zeolite–modified TiO2-based photocatalyst with synergistic effect for elimination of organic pollutant in wastewater treatment. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1009045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Fan, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Yi, Y. Tuning selectivity of acetic acid and alcohols by Brønsted and Lewis acid sites in plasma-catalytic CH4/CO2 conversion over zeolites. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2024, 350, 123938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.R.C.; Torres, J.A.; Giroto, A.S.; Oliveira, A.V.P.S.; Silva, P.H.M.; Santos, F.L.; Iga, G.D.; Ribeiro, C.; Nogueira, A.E. Development of photocatalysts based on zeolite A with copper oxide (CuO) for application in the artificial photosynthesis process. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh, A.; Zabihi-Mobarakeh, H. Heterogeneous photodecolorization of mixture of methylene blue and bromophenol blue using CuO-nano-clinoptilolite. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2014, 20, 1421–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iazdani, F.; Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh, A. Supported cuprous oxide-clinoptilolite nanoparticles: Brief identification and the catalytic kinetics in the photodegradation of dichloroaniline. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 250, 119348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornejo-Cornejo, L.G.; Romero, R.; Gutiérrez-Alejandre, A.; Regalado-Méndez, A.; Amado-Piña, D.; Hernández-Servín, J.A.; Natividad, R. Iron and copper pillared clay photo-catalyzes carbon dioxide chemical reduction in aqueous médium. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 511, 162193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberian, M.; Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh, A. Synergistic photocatalytic degraded tetracycline upon supported CuO clinoptilolite nanoparticles. Solid State Sci. 2024, 147, 107381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, R.; Yousefinejad, S.; Mokarami, H. Catalytic ozonation process using CuO/clinoptilolite zeolite for the removal of formaldehyde from the air stream. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 16, 6629–6636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh, A.; Amiri, M. CuO supported Clinoptilolite towards solar photocatalytic degradation of p-aminophenol. Powder Technol. 2013, 235, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, M.; Koleżyński, A.; Mozgawa, W. Vibrational Spectra of Zeolite Y as a Function of Ion Exchange. Molecules 2021, 26, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miądlicki, P.; Wróblewska, A.; Kiełbasa, K.; Koren, Z.C.; Michalkiewicz, B. Sulfuric acid modified clinoptilolite as a solid green catalyst for solvent-free α-pinene isomerization process. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2021, 324, 111266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Gadd, G.M. Biosynthesis of copper carbonate nanoparticles by ureolytic fungi. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 7397–7407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, A.E.; Oliveira, J.A.; da Silva, G.T.S.T.; Ribeiro, C. Insights into the role of CuO in the CO2 photoreduction process. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, A.E.; Giroto, A.S.; Neto, A.B.S.; Ribeiro, C. CuO synthesized by solvothermal method as a high capacity adsorbent for hexavalent chromium. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2016, 498, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, M.; Dechnik, J.; Szymczak, P.; Handke, B.; Szumera, M.; Stoch, P. Thermal Behavior of Clinoptilolite. Crystals 2024, 14, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siva, T.; Muralidharan, S.; Sathiyanarayanan, S.; Manikandan, E.; Jayachandran, M. Enhanced Polymer Induced Precipitation of Polymorphous in Calcium Carbonate: Calcite Aragonite Vaterite Phases. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2017, 27, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lwin, Y.; Yarmo, M.A.; Yaakob, Z.; Mohamad, A.B.; Daud, W.R.W. Synthesis and characterization of Cu–Al layered double hydroxides. Mater. Res. Bull. 2001, 36, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esenli, F.; Şans, B.E.; Erdoğan, B.; Sirkecioğlu, A. The surface characteristics of natural heulandites/clinoptilolites with different extra-framework cations. Clay Min. 2023, 58, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geovo, J.D.C.; Torres, J.A.; Giroto, A.S.; Santos, F.L.; Souza, J.R.C.; Ribeiro, L.S.; Nogueira, A.E. Effect of CuO synthesis on the activity and selectivity of MCM-41/CuO composites in the CO2 photoreduction process. Mater. Lett. 2024, 356, 135608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhal, J.P.; Dash, T.; Hota, G. Iron oxide impregnated mesoporous MCM-41: Synthesis, characterization and adsorption studies. J. Porous Mater. 2020, 27, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Dong, L.; Chen, Y. Influence of CuO loading on dispersion and reduction behavior of CuO/TiO2 (anatase) system. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1998, 94, 1905–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raizada, P.; Sudhaik, A.; Patial, S.; Hasija, V.; Khan, A.A.P.; Singh, P.; Gautam, S.; Kaur, M.; Nguyen, V.-H. Engineering nanostructures of CuO-based photocatalysts for water treatment: Current progress and future challenges. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 8424–8457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Chang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, Z.; Zou, P.; Wang, H.; Jia, L. CuO@N/C-ZnO nanoflowers with quantum dots derived from ZIF-8 for efficient CO2 photoreduction. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 129248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shang, X.; Shen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, D.; Lin, J.; Wu, J.C.S.; Fu, X.; Wang, X.; Li, C. Direct and indirect Z-scheme heterostructure-coupled photosystem enabling cooperation of CO2 reduction and H2O oxidation. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Deng, C.; Xie, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Sheng, H.; Chen, C.; Zhao, J. Photocatalytic C–C Coupling from Carbon Dioxide Reduction on Copper Oxide with Mixed-Valence Copper(I)/Copper(II). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 2984–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadi, M.W.; Mohamed, R.M.; Ismail, A.A. Uniform dispersion of CuO nanoparticles on mesoporous TiO2 networks promotes visible light photocatalysis. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 8819–8826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyalcin, S.; Akyalcin, L.; Ertugrul, E. Modification of natural clinoptilolite zeolite to enhance its hydrogen adsorption capacity. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2024, 50, 1455–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, R.; Liu, K.; Hu, H.; Fan, M.; Li, K.; Zhang, M.; Huang, H. Boosting CO2 photoreduction to acetic acid via the van der waals heterostructures of monolayer Nb2O5 modified TiO2 nanotubes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 359, 130835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geovo, J.D.C.; Torres, J.A.; Giroto, A.S.; Rocha, F.C.N.; Garcia, M.M.; Silva, G.T.S.T.; Souza, J.R.C.; de Oliveira, J.A.; Ribeiro, C.; Nogueira, A.E. Evaluation of the activity and selectivity of mesoporous composites of MCM-41 and CuO in the CO2 photoreduction process. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2023, 439, 114631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Chen, J.; Koodali, R.T.; Hu, Y.; Xiao, Q.; Zhou, J.; Wang, X.; Guo, L. Activation of MCM-41 mesoporous silica by transition-metal incorporation for photocatalytic hydrogen production. Appl. Catal. B 2014, 150–151, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.