Abstract

Biodiversity assessment is important for evaluating community conservation status. The haor basin in Sylhet Division represents a transitional zone with high species availability, rare occurrences and endemism. As a result, this study aims to describe the haor-based freshwater fish composition, including habitat, trophic ecology, availability and conservation status. Semi-structured questionnaires were used to collect data on fish samples through focus group discussions, field surveys, and interviews with fisheries stakeholders on a monthly basis. We identified 188 morpho-species, of which 176 were finfish and 12 shellfish, distributed into 15 orders and 42 families where 29%, 42%, 15%, and 14% species were commonly available, moderately available, abundantly available, and rarely available, respectively. Cypriniformes was the dominant order in both total species and small indigenous species identified. Approximately 45.34% of species were riverine, 31.58% floodplain residents, 12.55% estuarine, 2.83% migratory, and 7.69% were exclusively hill stream residents. Carnivores and omnivores were the most dominant trophic groups. A total of 87.76% species were used as food, 12.23% as ornamental and 6.91% as sport fish. Approximately 50 species were threatened (7 critically endangered, 23 endangered and 20 vulnerable) at the national level, most of them belonging to Cypriniformes and Siluriformes. Based on endemism, 16 species were endemic of which Sygnathidae, Cobitidae, Olyridae, Cyprinidae and Balitoridae fell under the threatened category. Minimizing intense fishing efforts, banning indiscriminate fishing and destructive fishing gear, initiating fish sanctuaries and beel nurseries, and implementing eco-friendly modern fishing technology are suggested to conserve the threatened species. This study represents a guideline for assessing the availability and conservation of freshwater fish in the Sylhet belt and serves as a reference for decision-makers in order to allow for the sustainable exploitation of fisheries resources within an ecosystem-based framework.

1. Introduction

Basic knowledge of species ordination patterns and existence images is important to accurately describe the structure and dynamics of an ecosystem [1]. Moreover, this information supports the fruitful management of natural resources and reduces possible anthropogenic effects [2,3]. Equatorial freshwater fish are highly diverse and not easily characterized by any specific features. Scientists distinguish freshwater fish into three major groups in terms of saltwater tolerance and the presumed ability to spread by overcoming maritime barriers: [4] fish that are strictly intolerant of saltwater (primary division), rarely capable of crossing narrow marine boundaries (secondary division), and representatives of marine families colonizing inland water from the sea (peripheral division). Fish Base (http://www.fishbase.org (accessed on 7 December 2016) adapts a slightly different salient feature of freshwater and brackish water fish species into three groups: (1) entirely freshwater, (2) fresh and brackish water, and (3) fresh, brackish and seawater.

Globally, freshwater and brackish water fish species belong to 207 families and 2513 genera, of which 11,952 are strictly freshwater species [5] and 15,062 inhabit fresh and brackish waters [6]. Notably, the number assessed to be 13,000 ichthyofauna found in freshwater reservoirs covers only 1% of the earth’s surface. Freshwater fish species and the stability of their existing ecosystem are seriously threatened and are the world’s most endangered group of animals after amphibians [7,8,9].

Bangladesh is blessed with highly diverse and rich natural aquatic resources in the form of rivers, streams, estuaries, mangroves, floodplains, haors (seasonal wetlands), baors (oxbow lakes), beels (perennial water bodies), canals and artificial reservoir ponds. A total of 253 fish species were assessed where 104 were riverine, 113 floodplain inhabitants and 36 migratory species [10]. The freshwater fish species are not limited to freshwater; 62 species live in estuaries and numerous fish species migrate upstream from the Bay of Bengal [11]. Among the assessed fish species, 64 species were listed as threatened, comprising 25.3% of the total species assessed, while 9 species were Critically Endangered (CR), 30 species were Endangered (EN) and 25 species were Vulnerable (VU). In addition, 27 species were listed as Near Threatened (NT), 122 species as Least Concern (LC), and the remaining 40 species were considered Data Deficient (DD). No fish were found to be Extinct or Regionally Extinct [10]. In the last few decades, freshwater fish faced adverse impacts due to anthropogenic environmental degradation such as urbanization, construction of dams, diversion of water for irrigation and power generation and pollution. Unfortunately, the country’s biodiversity is under threat due to the recent growing population and excessive extraction and use of natural resources [10].

Sylhet Division covers 12,558 square kilometers (with 217 haors covering 16,154.51 ha; 663 floodplains covering 174,824.17 ha; 3167 beels covering 40,946.18 ha; 116,850 ponds covering 15,129.09 ha and 20 fish sanctuaries) and is comprised of four districts (Sylhet, Sunamganj, Moulvibazar, and Hobiganj). It is the most important breeding, nursery and grazing habitats for freshwater fish species with near 0.26 million metric tons (MT) total production and a surplus of 55.85 thousand metric tons [12]. Approximately 0.152 million registered fishers are engaged in fishing and depend on natural waters for livelihood. Fishers with diverse fishing crafts and apparatuses seize a massive number of different fish species in the haors, rivers, and beels every day except during times when fishing is definitely prohibited. Indiscriminate killing, over-exploitation, use of destructive fishing gear and techniques, pollution and lack of proper management have put the fish biodiversity of Sylhet division at extreme risk. As a result, many fish have become vulnerable, endangered and critically endangered over time. The extinction of fish species at the global and local levels seriously threatens biodiversity and ecosystem balance [13]. Some research studies have been conducted on fish biodiversity in Sylhet Division, but a complete list of existing ichthyofauna with up-to-date conservation status is lacking. Therefore, it is very challenging to comprehend the present status of fish in Sylhet Division. Detailed survey work with a logical inventory of fish species is highly required to undertake necessary management for conservation of fish biodiversity of Sylhet division.

Although there are a few relevant publications on diversity and conservation status in this region, to date there is no compilation of the complete list of freshwater fish of the entire Sylhet division and information on their potential threat level. Considering this scenario, the aim of the study was to (a) prepare an updated checklist of floodplain rich freshwater fish species composition, availability status, habitat and trophic status, and national and global conservation status, and (b) propose recommendations to develop the existing conservation position of threatened fish in Bangladesh.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

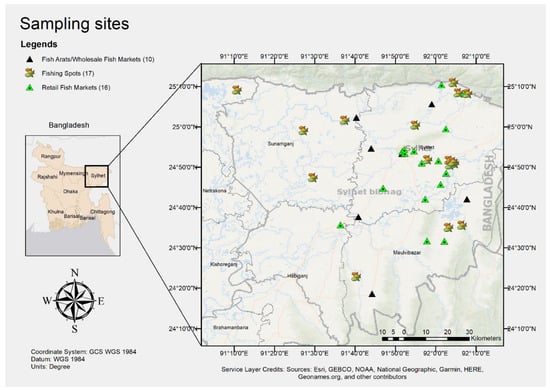

Sylhet division lies between latitudes 23°58′ and 25°12′ north and longitudes 90°56′ and 92°30′ east. It is bordered by Meghalaya to the north, Tripura to the south, Assam to the east and Netrokona and Kishoreganj districts to the west. The study was conducted at 43 sampling sites (10 sites in fish arat/wholesale fish markets, 16 sites in retail fish markets, and 17 sites in fishing spots/areas) across Sylhet division (Figure 1). The study sites were selected to consider their unique geographic locations and incredible species diversity. The GPS reading of sampling spots was taken using Android GPS Test Software (version 1.6.3). A map of the sampling sites was created using ArcMap 10.7 [14].

Figure 1.

Location of the sampling sites.

2.2. Data Collection Framework and Species Identification

An eight-month study was conducted from September 2017 to April 2018. Focus group discussions (FGDs) with commercial fishing vessel owners, fish retailers, fish traders, locals, fishermen, sport anglers, riverbank colonials, and other people who came forward were used to obtain information regarding the feasibility of sampling existing fish species. In addition, a semi-structured questionnaire was used to conduct consultations at fish markets, fish landing centers, and fishing villages.

Fish samples were collected in both live and fresh conditions. Samples of live and fresh fish were collected directly from fishermen at fishing spots, aratders/wholesalers at arat/wholesale fish markets, and retailers at retail fish markets. For capturing live fish samples, fishing nets (seine net, gillnet, cast net, drag net, pull net, push net, and lift net) and fishing traps were used (Doair, Bair, Chai, Bana, Bamboo pipe, Hogra), and the ethical procedure approved by the ‘Ethical Approval Committee of Bangladesh Agricultural University Research System (BAURES)’ was followed. During sampling, photos of each fish species were taken with a digital camera. The collected fish samples were acknowledged by examining their biometric features in accordance with published articles [6,10,11,15].

Trophic category and habitat groups were determined by following IUCN Bangladesh [10] and the Web-based related database [6]. When data were unavailable on IUCN Bangladesh and Fishbase, information was gathered from various articles published earlier [12,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. As precise information on fish trophic levels is absent in the study area, the food items for each species were reviewed to explain the feeding mode according to the literature found for each taxon. The identified fish species were categorized into functional groups based on feeding mode (omnivores, carnivores, planktivores, herbivores, larvivores, and insectivores). The ecological structure was categorized into five groups, namely, riverine, hill stream, migratory, estuarine, and floodplain residents. To identify the commercial value of fish, each species was evaluated based on specific criteria for food (showed adequate growth in unit time and attained maximum size), sport (the preference of anglers), or ornamentation (based on diversified ornamental criteria viz. beautiful color, shape and size, banding pattern, hardiness, transparent body, calm behavior, and adhesive suckers). Endemic species were identified based on their distribution restricted to haor basins in Sylhet [12]. In addition, identified fish were categorized into four groups based on respondent perceptions, namely, abundantly available (AA): available in abundance all year round (frequency of occurrence: 76–100%), commonly available (CA): usually found in small numbers all year round (frequency of occurrence: 51–75%), moderately available (MA): rarely found in the study area (frequency of occurrence: 26–50%), and rarely available (RA): found infrequently in very small numbers (frequency of occurrence: 1–25%) [4,25]. The conservation status of each species was listed in accordance with the IUCN Red List of Bangladesh [10] and Threatened Species of Global Red List [16].

2.3. Data Analysis

To detect the most frequent freshwater fish orders, families, trophic categories, habitat group endemicity, commercial fish value, and existing conservation status, the contribution (frequency of occurrence) of each group was assessed by following equation: F0 = (N/n) × 100, where F0 is % contributor or frequency of occurrence, N is the category to be calculated (order, family, or conservation status) and n is the total number of species in each group.

3. Results

3.1. Fauna Composition

The present study on freshwater fish species in the Sylhet division revealed one hundred eighty-eight (188) species, distributed into 15 orders and 42 families, detected from 43 sampling spots. The identified fish included 176 finfish (166 indigenous and the rest 10 were exotic) followed by 12 shellfish (freshwater prawn) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Freshwater fish species recorded in Sylhet division of Bangladesh. CA—Commonly available; MA—Moderately available; AA—Abundantly available; RA—Rarely available; FP—Flood plain; HS—Hill streams; Et—Estuarine; R—River; Mgt—Migratory; NE—Not Evaluated; DD—Data Deficient; LC—Least Concern; NT—Near Threatened; VU—Vulnerable; EN—Endangered; CR—Critically Endangered; BD—National conservation status; IUCN—Global conservation status.

Table 2 summarizes a comparison of recorded fish species and their presence (%) to the national and global levels. Compared with nationwide levels, Synbranchiformes showed the highest prevalence (116.67%) followed by Osteoglossiformes (100%), Cyprinodontiformes (100%), Siluriformes (83.64%) and Cypriniformes (79.35%). Compared with worldwide levels, the highest presence was occupied by Anguilliformes (83.33%), followed by Tetraodontiformes (16.67%), Mugiliformes (12.5%) and Pleuronectiformes (10%). The rest were less than 10% compared with global prevalence.

Table 2.

Status of freshwater fish species in Sylhet division compared with national (BD) and global level.

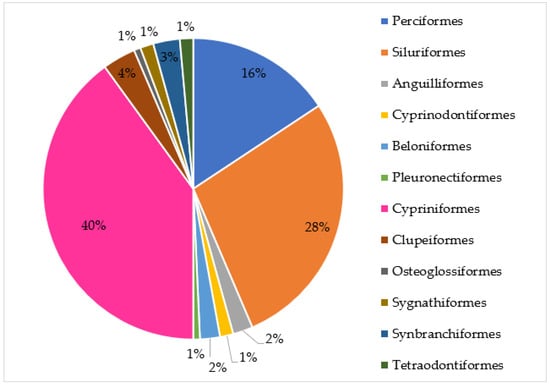

Cypriniformes was the dominant order (39.04%) followed by Siluriformes (24.6%) and Perciformes (13.37%). The rest of the faunal orders contributed approximately 23.53% of the total species found (Table 3). Cyprinidae was the leading family, accounting for 29.95% (56 species) of all families identified, followed by Bagridae with 6.95% (13 species), Sisoridae with 6.95% (13 species), Palaemonidae with 6.42% (12 species), and Cobitidae with 5.35% (10 species).

Table 3.

Number and frequency of occurrence (FO) of orders and families of fish in Sylhet division, Bangladesh.

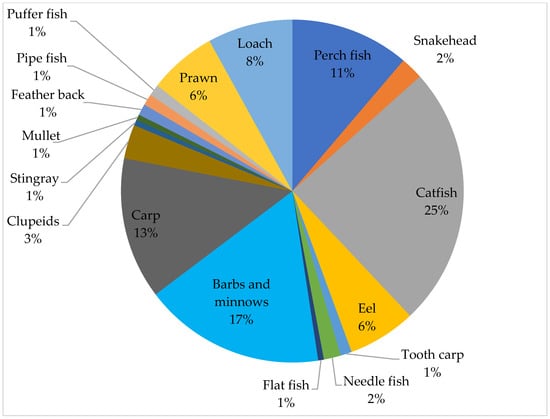

The fish recorded in this study were categorized into 17 major groups: perch, snakeheads, catfish, eels, tooth carp, needlefish, flatfish, barbs and minnows, carp, clupeids, stingrays, mullets, feather backs, pipefish, pufferfish, prawns, and loach (Figure 2). Catfish contributed the most, accounting for 25% of the total groups, followed by barbs and minnows (17%), carp (13%), perch fish (11%), loach (8%), prawns (6%) and eels (6%). The remaining groups contributed a considerably smaller percentage (14%). Small indigenous species (SIS) comprised 140 species distributed into 12 orders, of which Cypriniformes (56 species), Siluriformes (39 species) and Perciformes (22 species) were dominant, representing approximately 83.57% (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Major groups of freshwater fish in Sylhet division.

Figure 3.

Composition of small indigenous fish species (based on order) from the study area.

3.2. Habitat Status and Trophic Ecology of Fish Fauna

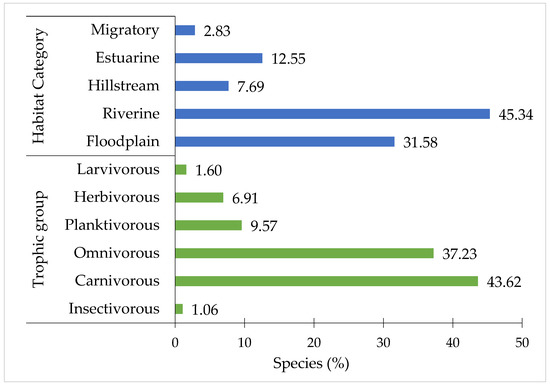

Figure 4 reveals that 45.34% of the species were riverine, 31.58% floodplain residents, 12.55% estuarine, 2.83% migratory (traveled to floodplains and other habitats for feeding and spawning during monsoon) and 7.69% were exclusively hill stream inhabitants. Figure 4 also demonstrates that carnivorous and omnivorous species were the leading trophic groups, accounting for 43.62% and 37.23%, respectively, followed by planktivorous with 9.57%, herbivorous with 6.91%, larvivorous with 1.6%, and insectivorous with 1.06%.

Figure 4.

Habitat structure and trophic groups of freshwater fish recorded in Sylhet division.

3.3. Endemic Status of Fish

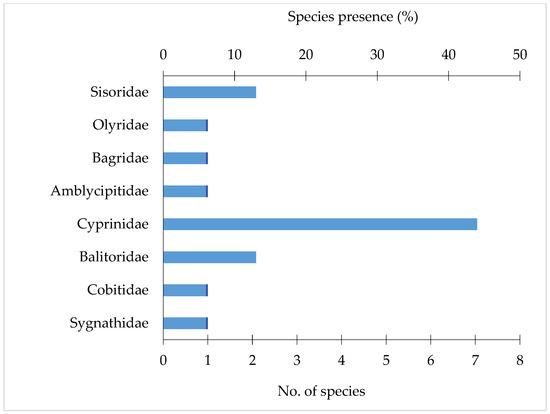

Figure 5 summarizes the species-rich group of endemic species from the study area. A total of sixteen (16) endemic species were identified, distributed across three orders and eight families, accounting for 8% of the total species found. Cyprinidae was the leading endemic species-rich family (seven species—Labeo ariza; Aspidoparia morar; Barilius tileo; Barilius bendelisis; B. barila; B. vagra; B. dogarsinghi) with 44% of total endemic species found, followed by Balitoridae with 13% (two species—Schistura sikmaiensis; Syncrossus hymenophysa) and Sisoridae with 13% (two species—Gogangra viridescens; Gagata sexualis). The rest contributed 30% (one species of each family) to the total endemic species found.

Figure 5.

Diagrammatic representation of families rich in endemic freshwater species in Sylhet division.

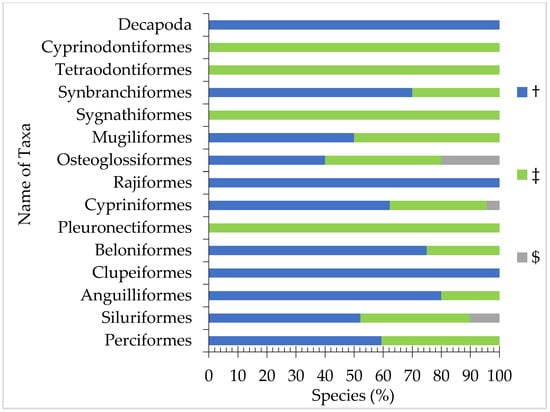

3.4. Commercial Utilization Status of Fish

The utilization of commercial fish revealed that 87.76% (165 species) were consumed as food, with 43.03% also having ornamental value (71 sp.). Approximately 12.23% (23 species) were only of ornamental value, while 6.91% (13 species) were considered sport fish with food value. Tor tor and Chitala chitala were considered to be food, ornamental, and sport fish (Table 1). All species belonging to Decapoda, Rajiformes, and Clupeiformes were found to have food value, while Tetraodontiformes, Pleuronectiformes, Cyprinodontiformes, and Sygnathiformes had ornamental value. Cypriniformes, Osteoglossiformes, and Siluriformes were shown to have food, ornamental, and sport fish value, with food value being more prevalent (62.28%) compared to the other groups (40% and 52.17% respectively) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Relative frequency (%) of commercial utilization of fish. † Food fish, ‡ Ornamental fish, $ Sport fish.

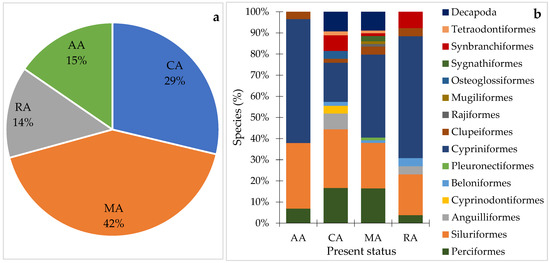

3.5. Present Status of Identified Fish Species

The current study revealed that approximately 42% of fish were moderately available, followed by 29% commonly available, 15% abundantly available and 14% rarely available (Figure 7a). Figure 7b summarizes the present status of species according to order. The results showed that moderately available, rarely available and abundantly available species were highest in Cypriniformes (39.24%, 57.69% and 58.62% respectively) whereas commonly available species were highest in Siluriformes (27.78%).

Figure 7.

Present status of identified fish (a) and frequency of occurrence (%) based on order (b). AA = Abundantly available; CA = Commonly available; MA = Moderately available; RA = Rarely available.

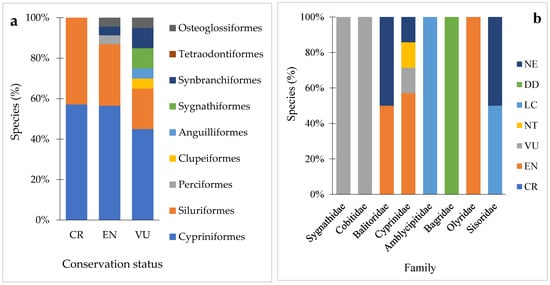

3.6. Conservation Status

A total of 161 species (86.1%) and 157 species (83.95%) were evaluated in the national list [10] and global list, respectively. Of these recorded species, 50 species (26.74%) were considered threatened at a national level (CR—7 sp.; EN—23 sp. and VU—20 sp.) and eight species (4.27%) at a global level (CR—1 sp.; EN—3 sp.; VU—4 sp.). The majority of recorded species were listed as LC both in the present study (42.55%) and globally (70.21%). Out of 188 species, 19 species were listed as NT, and 11 as DD, differing from their global category. We obtained a substantially large number of species (26 species in national status and 31 species in global) that have not been assessed in IUCN evaluation (Table 4).

Table 4.

Number and frequency of occurrence of threat categories of fish recorded in Sylhet division, Bangladesh.

Most species belonging to Cypriniformes (CR 57.14%, EN 56.52%, VU 45%) and Siluriformes (CR 42.86%, EN 30.43%, VU 20%) were listed as threatened in the present study (Figure 8a). Based on endemism, species belonging to Sygnathidae, Cobitidae and Olyridae were listed as VU and EN, respectively. Approximately 50% and 57.14% species from Balitoridae and Cyprinidae, respectively, were in the EN category (Figure 8b).

Figure 8.

Conservation status of fish: (a) all combined fish; (b) endemic species. CR—Critically endangered; EN—Endangered; VU—Vulnerable; NT—Near threatened; LC—Least concern; DD—Data Deficient; NE—Not Evaluated.

4. Discussion

4.1. Fauna Composition

Freshwater fish species are represented in all areas at the national level, which is one of the richest diversity of fish fauna with a rich variety of morpho-species. Approximately 253 fish species have been identified from freshwater in Bangladesh [10]. Rahman [11] recorded 265 species comprising 154 genera and 55 families and Hossain et al. [31] obtained 293 species of freshwater fish including 13 orders and 61 families in Bangladesh, both of which were higher than the present study. The most species-rich orders that covered all types of water bodies and ecosystems in the Sylhet division are similar to those found in national and global surveys, and there were six orders for which the proportion of freshwater species in the Sylhet division was 67.87% of national prevalence and 2.16% of global prevalence (Table 2). This indicates that freshwater fish in the Sylhet Belt play a significant role in the national and global freshwater fish species bank. The fish belonging to the Cyprinidae family in the present study were the most dominant, a common feature of the fish community similar to Asian rivers [32,33,34]. Nonetheless, little research has been conducted on the fish biodiversity and conservation status in the greater Sylhet region. For instance, lower freshwater fish diversity has been reported in haor and wetland ecosystems at the district level within the Sylhet division [31,32,33,34,35], which may be attributed to extremely insufficient sampling areas. Ray and Grassle [36] noted that hydrographic conditions, climatic patterns, and habitat are influential factors that drive the number of species. Moreover, the observed image of species diversity during the study period may also be influenced by the sampling strategies and efforts used [37].

The number of small indigenous fish (140 species) listed in the entire Sylhet division was similar to the number found in Bangladesh [38]. The leading SIS orders in the study area were Cypriniformes, Perciformes, and Siluriformes, similar to observations from the Gorai River [39] and the southern coastal waters of Bangladesh [40]. Geographically, the connection of freshwater habitats such as rivers, floodplains, and diverse landscape areas maintains continuity to facilitate the movement of SIS [33].

Exotic species are extensively cultured in Bangladesh but are also found in open aquatic habitats, most likely due to escape from adjacent ponds and periodic water bodies during flash floods [40]. Our synthesis found 176 freshwater fish, of which 166 were indigenous and the remaining 10 exotic. Mukul et al. [40] found 16 exotic freshwater fish species in Bangladesh. Galib and Mohsin [41] listed 92 varieties of exotic fish in Bangladesh, of which 16 were cultured fish species and the rest were ornamental fish species. Islam and Hossain [42] estimated a total of 57 fish species in Dekar haor, of which 52 were native and 5 were exotic. Suravi et al. [43] highlighted 51 species in Dekar haor, of which 47 were indigenous and 4 were exotic. Sayeed et al. [44] and Mahalder and Mustafa [45] reported seven and nine exotic freshwater fish species in the Hakaluki haor in Moulovibazar and Sunamganj regions, respectively, within CBRMP’s working area. Exotic species may harm the food web and breeding ground for native species, leading to the depletion of natural reserves of endemic species and the extinction of some native species [46]. Therefore, greater emphasis should be placed on preventing the potential negative effects of exotic species on native stocks.

4.2. Habitat and Trophic Ecology of Fish

Floodplain-dwelling fish take shelter in nearby perennial water bodies, such as rivers and deep beels, when the floodplain’s water level decreases during the dry season, which complicates their classification. According to IUCN Bangladesh [10], floodplain species dominate. Similarly to the present study, Pandit et al. [47] found that 54.9% of the species of the Dhanu river and surrounding wetlands in Kishoreganj were beel residents and 45.1% were riverine residents. Based on their habitat preference, freshwater fish spend the majority of their lives in rivers and/or floodplains, where they tend to live for much longer than in other types of freshwater environments. Feeding is the leading activity throughout the entire life cycle of fish [46]. The current trophic structure study revealed the dominance of carnivores and omnivore fishes, which corresponded to previous findings [14,17,20,48]. Sarker et al. [49] observed similar composition of feeding types in the Western Ghats and Ganges river in India. Nevertheless, several fish species had multiple trophic levels depending on their ecological resources or prey availability [50], which was similar to the current findings.

4.3. Endemic Status of Fish

An endemic fish is defined as a fish species localized in a particular area or country where it originated. As no previous research has been conducted on the endemic fish species of haor in Sylhet division, the present findings can be compared to those of neighboring countries. However, Dey et al. [20] at the Ganges river in India and De Silva et al. [51] in South-East Asia reported similar patterns. Higher endemicity was reported by [52,53] in Assam and the neighboring North-Eastern states of India (48 and 33 species respectively). The presence of a high number of endemic species in the aforementioned Indian states could be attributed to hilly terrain and perennial wetlands. Therefore, a comprehensive study of the aforementioned fish endemicity variations in the Sylhet region is required.

4.4. Commercial Utilization Status of Fish

Nature provides a wide variety of fish species used as food, which differ in shape and taxonomic group [54]. According to [19,20], in West Bengal, India, food fish were dominant over ornamental fish, resulting in a reverse pattern. We identified 94 native fish out of 188 fish species as ornamental fish. Some of them are already used as ornamental fish, while others could be used based on their diverse ornamental criteria viz. beautiful color, shape and size, banding pattern, hardiness, transparent body, calm behavior, and adhesive suckers [24]. For instance, a lower number of potential indigenous freshwater fish and non-fish species (31 spp.) were identified as having ornamental value in Bangladesh [55]. It is difficult to list the commercial utilization of fish due to the lack of preceding evidence on fish diversity, but the current study could be considered baseline information for upcoming commercial utilization status investigation.

4.5. Present Status of Identified Fish Species

The current status of freshwater fish is consistent with that of the fish communities in various wetland ecosystems in the haor-based, floodplain-rich Sylhet division [35,44,46,56,57]. Observing the current status of fish, it is possible that a large proportion of the fish fauna under Cypriniformes and Siluriformes classified as rarely available in that region will disappear in the near future.

4.6. Conservation Status

IUCN classification is widely used for evaluating the conservation status of fish around the world. However, due to the lack of data on the regional list, it was impossible to assess the species’ regional, national and global conservation status to validate a similar pattern. According to IUCN Bangladesh [10], 25.3% of species are listed under a threatened category. We highlighted that 26.74% of our species found were considered to be threatened at the national level. This result reflects the findings reported by [44,58,59] at different haors and other water bodies in the Sylhet division. The threatened species composition recorded in the present study was lower than in earlier reports from Sylhet Sadar and Dekhar haor in Sunamganj District [60,61]. According to Hossain and Wahab [30] and IUCN Bangladesh [10], most of the fish belonging to Cypriniformes and Siluriformes faced significant threat, and the majority of them were categorized as either endangered or critically endangered over the last 10 years, which was similar to the present findings. Species listed as critically endangered experienced at least an 80% population decline over the past 10 years or three generations, indicating a significant threat to extinction in near future in the Sylhet region.

Pangasianodon hypophthalmus, a Critically Endangered species at the global level, infiltrated Bangladesh in the early 1990s and is now an intensively cultured species that frequently occupies freshwater bodies on a large scale [62]. Chowdhury et al. [63] reported that Tor tor, Pangasius pangasius and Anguilla bengalensis were extinct at the regional level. Islam et al. [34] and Chakraborty and Mirza [64] demonstrated that two species, viz. Tor tor and Labeo nandina, were extinct from the Juri River in Sylhet and the Someswari River in Netrokona respectively, compared to 10–20 years previously. Channa barca was found to be regionally extinct from the survey area during the study period. Furthermore, species identified as Critically Endangered at the national level, such as Ompok pabo, Bagarius bagarius, Sisor rabdophorus, Schistura corica, Labeo boga, Labeo nandina, and Tor tor were captured in limited numbers but should be prioritized for conservation owing to their population decline. According to IUCN Bangladesh [10], Wallago attu was listed as Vulnerable and Notopterus notopterus, Canna marulius, Mystus armatus as Endangered; however, these species have recently moved into the Least Concern and Endangered categories, respectively, due to signs of population growth and are now abundant in the haor [43].

We synthesized 27 species considered Not Evaluated, of which 10 were exotic and the remaining 17 were indigenous. Due to a lack of indigenous entities, these invasive species were not included in IUCN Bangladesh [10]. Four species, Tetraodon nigroviridis, Pseudorhombus arsius, Hypostomus Plecostomus, and Morigua raitaborua, were used as ornamental fish at national and global levels, with Hypostomus Plecostomus having both food and ornamental value. Thirteen species listed as Not Evaluated at national levels with only food value, including Mastacembelus oatesii, Himantura bleekeri, Puntius parrah, Lamnostoma orientalis, Panna microdon, Barilius dogarsinghi, Syncrossus hymenophysa, Oreonectes evezardi, Lepidocephalus thermalis, Parambassis thomassi, Mystus keletius, and Gagata sexualis, were used as food for local inhabitants as well as recreational purposes; Glyptothorax platypogonoides was considered an ornamental fish among the non-evaluated fish [65]. Additionally, a significant number of species listed as Not Threatened and Data Deficient by IUCN Bangladesh [10] require further investigation at the regional and national levels in subsequent assessments. Assessment should be prioritized at the regional level for conservation and justifying the current status of endemic species.

Local environmental knowledge, participatory planning with fisheries stakeholders, and the adoption of sustainable fisheries management practices could be the first steps in eradicating the decline in threatened species diversity and availability [66]. Fishing during the breeding and spawning seasons, indiscriminate harvesting of fish larvae and fingerlings, and the use of harmful fishing gear and crafts must be prohibited immediately. Declaring some parts of or the whole of a haor as a “fish sanctuary”, and the concept of a “beel nursery”, could be effective steps toward conserving endangered and vulnerable species in Sylhet division. Breeding and nursery grounds, migration routes and hotspots of fish biodiversity in the haor region must be designated as nature reserves and delineated by a demarcation line, with fishing strictly prohibited and navigation temporarily stopped during the breeding season. Fishing limitations by completely drying out water bodies and regular dredging of silted water are required to facilitate fish habitat, breeding, nursing, maturation, and relocation. Eco-friendly fishing technologies for the monitoring, controlling and surveillance of protected areas and threatened species, selection of fishing gear and crafts, and development of a digital fishing calendar for effective banning periods and catch restrictions should be initiated to conserve the threatened fish species [67]. In addition, a live fish gene bank could be an effective way to conserve threatened species. However, the most important aspect of conserving the threatened fish of haor in Sylhet division is to raise awareness among the stakeholders through effective communication, collaboration, and education. Furthermore, financial support from the government and donor agencies is crucial for further research and monitoring, along with raising awareness among fishers regarding the importance of conserving fish diversity in the haor areas. In short, since fish and fisheries in this region support the livelihoods of thousands of marginalized poor, particularly fishers, the government should adopt a long-term conservation strategy to ensure sustainable production in the haor region in Sylhet division.

5. Conclusions

The number of species documented during the study is a good indication of rich biodiversity in the Sylhet division. Fish species belonging to Cypriniformes and Siluriformes face significant threat levels. In addition, species that are critically endangered, endangered and vulnerable at national and global levels are intensively being cultured and a live gene bank is being established to conserve threatened species. Furthermore, the findings of this study could serve as an important benchmark for assessing biodiversity and fish conservation in the haor region. Notably, a large number of fish might have been excluded from evaluation due to insufficient scientific research. The threatened fish recorded in the Sylhet division indicate an alarming threat to fish conservation. Community and ecosystem-based co-management programs that promote the conservation of biodiversity and social protection schemes can be very effective to conserve fish diversity. However, fish sample collection from fishers, rather than direct sampling, limited sample size, and taxonomic identification through barcoding due to lack of funding were the major drawbacks of the present study. In addition, current status and threat level were recorded based on fishers’ perceptions via a survey and researcher observation. In order to conserve fish biodiversity in this area, a thorough study is needed on species composition and assemblages, along with species’ taxonomic identification, life history, geographic range, ecology and reproductive biology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.C.S. and M.K.R.; methodology, F.C.S. and M.K.R.; formal analysis, M.K.R. and F.C.S.; investigation, F.C.S. and M.K.R.; resources, F.C.S. and M.K.R.; data curation, M.K.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K.R. and F.C.S.; writing—review and editing, F.C.S., M.K.R., A.S., M.A.S. and A.K.M.N.A.; visualization, M.K.R., M.A.S. and A.S.; supervision, F.C.S., M.K.R. and A.K.M.N.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the ‘Ethical Approval Committee of Bangladesh Agricultural University Research System (BAURES)’ (protocol code: 502/BAURES/ESRS/FISH/20 and date of approval: 20 March 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Department of Fisheries of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh for providing financial support for data collection and to stakeholders in the fishing community across all of Sylhet division for their support in sampling and identifying fish samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests or personal relationships that may affect the work reported in this paper.

References

- Hillebrand, H.; Blasius, B.; Borer, E.T.; Chase, J.M.; Downing, J.A.; Eriksson, B.K.; Filstrup, C.T.; Harpole, W.S.; Hodapp, D.; Larsen, S.; et al. Biodiversity change is uncoupled from species richness trends: Consequences for conservation and monitoring. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017, 55, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D.; Isbell, F.; Cowles, J.M. Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2014, 45, 471–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, J.; Johansson, E.L.; Olsson, L. Harnessing local knowledge for scientific knowledge production: Challenges and pitfalls within evidence-based sustainability studies. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, G.S. Salt-tolerance of fresh-water fish groups in relation to zoogeographical problems. Bijdr. Dierkd. 1949, 28, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.S. Fishes of the World, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; p. 601. [Google Scholar]

- Froese, R.; Pauly, D. List of Freshwater Fishes Reported from Bangladesh, FishBase; World Wide Web Electronic Publication: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: http://www.fishbase.org (accessed on 7 December 2016).

- Suski, C.D.; Cooke, S.J. Conservation of aquatic resources through the use of freshwater protected areas: Opportunities and challenges. Biodivers. Conserv. 2007, 16, 2015–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruton, M.N. Have fishes had their chips? The dilemma of threatened fishes. Environ. Biol. Fish. 1995, 43, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, J.R.; Lockwood, J.L. Extinction in a Weld of bullets: A search for the cause in the decline of the world’s freshwater fishes. Biol. Conserv. 2001, 102, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN Bangladesh. Red List of Bangladesh, 5th ed.; Freshwater Fishes, (IUCN) International Union for Conservation of Nature, Bangladesh Country Office: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2015; p. xvi+360. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, A.K.A. Freshwater Fishes of Bangladesh, 2nd ed.; Zoological Society of Bangladesh, University of Dhaka: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2005; p. 394. [Google Scholar]

- DoF. Yearbook of Fisheries Statistics of Bangladesh, 2017–2018; Fisheries Resources Survey System (FRSS), Department of Fisheries, Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2018; pp. 2–37.

- Baillie, J.E.M.; Hilton-Taylor, C.; Stuart, S.N. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. A Global Species Assessment; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2004; p. xviv+191. [Google Scholar]

- ESRI. ArcGIS Desktop: Release 10; Environmental Systems Research Institute: Redlands, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Talwar, P.K.; Jhingran, A.G. Inland Fishes of India and Adjacent Countries; Oxford & IBH Publishing Company Pvt. Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 1991; Volume 2, p. 1158. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; Version 2020; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 3, Available online: http://www.iucnredlist.org (accessed on 31 December 2020).

- Lakra, W.S.; Sarkar, U.K.; Kumar, R.S.; Pandey, A.; Dubey, V.K.; Gusain, O.P. Fish diversity, habitat ecology and their conservation and management issues of a tropical River in Ganga basin, India. Environmentalist 2010, 30, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Rana, N.; Varma, M. Comparative Morphology of Alimentary Canal in Relation to Feeding Habit of Indian Rasborine Fishes. Proc. Zool. Soc. India 2016, 15, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, A.; Nur, R.; Sarkar, D.; Barat, S. Ichthyofauna Diversity of River Kaljani in Cooch Behar District of West Bengal, India. Int. J. Pure Appl. Biosci. 2015, 3, 247–256. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, A.; Sarkar, K.; Barat, S. Evaluation of fish biodiversity in rivers of three districts of eastern Himalayan region for conservation and sustainability. Int. J. Appl. Res. 2015, 1, 424–435. [Google Scholar]

- Khaing, M.M.; Khaing, K.Y.M. Food and Feeding Habits of Some Freshwater Fishes from Ayeyarwady River, Mandalay District, Myanmar. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Songkhla, Thailand, 21 November 2018; IOP Publishing, 2020; Volume 416, p. 012005. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtiyar, Y.; Lakhnotra, R.; Langer, S. Natural food and feeding habits of a locally available freshwater prawn Macrobrachium dayanum (Henderson) from Jammu waters, North India. Int. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2014, 2, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, M.Y.; Ayub, F.; Mian, S.; Lucky, N.S.; Hossain, M.A.R. Biodiversity status of freshwater catfishes in some selected water bodies of Bangladesh. J. Taxon. Biodivers. Res. 2008, 2, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mahapatra, B.K.; Vinod, K.; Mandal, B.K. Inland indigenous ornamental fish germplasm of northeastern India: Status and future strategies. In Biodiversity and Its Significancei; IK International Pvt Ltd.: Delhi, India, 2007; pp. 134–149. [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav, B.V.; Kharat, S.S.; Raut, R.N.; Paingankar, M.; Dahanukar, N. Freshwater fish fauna of Koyna River, northern Western Ghats, India. J. Threat. Taxa 2011, 3, 1449–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.S.; Grande, T.C.; Wilson, M.V. Fishes of the World, 5th ed.; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Eschmeyer, W.N. (Ed.) Catalog of Fishes, Updated database version of May 2005; Catalog databases as made available to FishBase in May 2005; California Academy of Sciences: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, N.; Demaine, H.; Muir, J.F. Freshwater prawn farming in Bangladesh: History, present status and future prospects. Aquac. Res. 2008, 39, 806–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Grave, S.; Smith, K.G.; Adeler, N.A.; Allen, D.J.; Alvarez, F.; Anker, A.; Cai, Y.; Carrizo, S.F.; Klotz, W.; Mantelatto, F.L.; et al. Dead shrimp blues: A global assessment of extinction risk in freshwater shrimps (Crustacea: Decapoda: Caridea). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0120198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Wahab, M.A. The Diversity of Cypriniforms throughout Bangladesh: Present Status and Conservation Challenges; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 143–182. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.A.R.; Wahab, M.A.; Belton, B. The Checklist of the Riverine Fishes of Bangladesh; Fisheries and Aquaculture News (FAN Bangladesh); The world Fish Center, Bangladesh and South Asia Office: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2012; pp. 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hanif, A.; Siddik, M.A.B.; Chaklader, R.; Nahar, A.; Mahmud, S. Fish diversity in the southern coastal waters of Bangladesh: Present status, threats and conservation perspectives. Croat. J. Fish. Ribar. 2015, 73, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, D.; Pal, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Nandy, G.; Chakraborty, A.; Rahaman, S.H.; Aditya, G. Abundance and biomass of assorted small indigenous fish species: Observations from rural fish markets of West Bengal, India. Aquac. Fish. 2018, 3, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Kunda, M.; Pandit, D.; Harun-Al-Rashid, D. Assessment of the ichthyofaunal diversity in the Juri River of Sylhet district, Bangladesh. Arch. Agri. Environ. Sci. 2019, 4, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A.B.M.S.; Badhon, M.K.; Sarker, M.W. Biodiversity of Tanguar Haor: A Ramsar Site of Bangladesh Volume III: Fish. In Proceedings of the (IUCN) International Union for Conservation of Nature, Bangladesh Country Office, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 19 December 2015; p. xii+216. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, G.C.; Grassle, J.F. Marine biological diversity program. BioScience 1991, 41, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magurran, A.E. Measuring Biological Diversity; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.Y. Small Indigenous Fish Species culture in Bangladesh. In Proceedings of the National Workshop on Small Indigenous Fish Culture in Bangladesh, IFADEP-SP 2, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 12 December 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hanif, M.A.; Siddik, M.A.B.; Nahar, A.; Chaklader, M.R.; Rumpa, R.J.; Alam, M.J.; Mahmud, S. The current status of small indigenous fish species (SIS) of River Gorai, a distributary of the river Ganges. Bangladesh. J. Biodivers. Endanger Species 2016, 4, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mukul, S.A.; Khan, M.A.S.A.; Uddin, M.B. Identifying threats from invasive alien species in Bangladesh. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 23, e01196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galib, S.M.; Mohsin, A.B.M. Cultured and Ornamental Exotic Fishes of Bangladesh: Past and Present; LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2011; pp. 65–66. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.; Hossain, A. Sanctuary Status on Diversity and Production of Fish and Shellfish in Sunamganj Dekar Haor of Bangladesh. J. Asiat. Soc. Bangladesh Sci. 2019, 45, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suravi, I.; Islam, M.; Begum, N.; Kashem, M.; Munny, F.; Iris, F. Fish biodiversity and livelihood of fishers of Dekar haor in Sunamganj of Bangladesh. J. Asiat. Soc. Bangladesh Sci. 2017, 43, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayeed, M.A.; Deb, R.C.; Bhattarcharjee, D.; Himuand, M.H.; Alam, M.T. Fish biodiversity of Hakaluki haor in the northeast region of Bangladesh. SAU Res. Prog. Rep. 2015, 2, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalder, B.; Mustafa, M.G. Introduction to Fish Species Diversity: Sunamganj Haor Region within CBRMP’s Working Area; Community-Based Resource Management Project-LGED; Worldfish: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2013; p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Cao, W.; Chen, Y. Effects of fish stocking on lake ecosystems in China. Acta Hydrobiol. Sin. 1997, 21, 271–280. [Google Scholar]

- Pandit, D.; Saha, S.; Kunda, M.; Harun-Al-Rashid, A. Indigenous freshwater ichthyofauna in the Dhanu River and surrounding wetlands of Bangladesh: Species diversity, availability, and conservation perspectives. Conservation 2021, 1, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.K. Environment and fish health: A holistic assessment of inland fisheries in India. In Natural and Anthropogenic Hazards on Fish and Fisheries; Narendra Publishing House: Delhi, India, 2007; pp. 137–151. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, U.K.; Gupta, B.K.; Lakra, W.S. Biodiversity, ecohydrology, threat status, and conservation priority of the freshwater fishes of river Gomti, a tributary of river Ganga (India). Environmentalist 2010, 30, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz-Agostinho, K.D.; Bini, L.M.; Fugi, R.; Agostinho, A.A.; Júlio, H.F., Jr. Food spectrum and trophic structure of the ichthyofauna of Corumbá reservoir, Paraná River Basin, Brazil. Neotrop. Ichthyol. 2006, 4, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, S.S.; Abery, N.W.; Nguyen, T.T.T. Endemic freshwater finfish of Asia: Distribution and conservation status. Divers. Distrib. 2007, 13, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, T.K. The Fish Fauna of Assam and the Neighboring North Eastern States of India; Occasional Paper No. 64, Records of Zoological Survey of India; Miscellaneous Publication: Calcutta, India, 1985; pp. 1–216. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S.K.; Lipton, A.P. Ichthyofauna of the N.E.H. Region with Special Reference to Their Economic Importance; ICAR Spl. Bu4letin No. B; ICAR Research Complex: Shillong, India, 1982; pp. 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Sipaúba-Tavares, L.H.; de S Braga, F.M. Study on feeding habits of Piaractus mesopotamicus (Pacu) larvae in fish ponds. Naga ICLARM Q. 1999, 22, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kangkon, R.H. Past and Present Status and Prospectus of Ornamental Fishes in Bangladesh. Available online: http://en.bdfish.org/2013/01/past-present-status-prospects-ornamental-fishes-bangladesh/ (accessed on 8 November 2014).

- Mozahid, M.N.; Ahmed, J.U.; Mannaf, M.; Akter, S.; Alam, M.S. Fish Biodiversity and Economic Performance of Fish Catching in Dekhar Haor: A Case Study of Sunamganj District, Bangladesh. IOSR J. Econ. Financ. 2017, 8, 66–72. [Google Scholar]

- Mia, M.; Islam, M.S.; Begum, N.; Suravi, I.N.; Ali, S. Fishing gears and their effect on fish diversity of Dekar haor in Sunamganj district. J. Sylhet Agric. Univ. 2017, 4, 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- ICNRS (Center for Natural Resource Studies). Biophysical and Socio-economic Characterization of Hakaluki Haor: Steps towards Building Community Consensus on Sustainable Wetland Resource management. In Proceedings of the IUCN-Netherlands Small Grants for Wetlands Program, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 15 June 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pandit, D.; Kunda, M.; Harun-Al-Rashid, A.; Sufian, M.A.; Mazumder, S.K. Present status of fish biodiversity in Dekhar haor, Bangladesh: A case study. World J. Fish. Mar. Sci. 2015, 7, 278–287. [Google Scholar]

- Maria, A.B.; Iqbal, M.M.; Hossain, M.A.R.; Rahman, M.A.; Uddin, S.; Hossain, M.A.; Jabed, M.N. Present status of endangered fish species in Sylhet Sadar, Bangladesh. Int. J. Nat. Sci. 2016, 6, 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Trina, B.D.; Roy, N.C.; Das, S.K.; Ferdausi, H.J. Socioeconomic status of fishers’ community at Dekhar Haor in Sunamganj district of Bangladesh. J. Sylhet Agric. Univ. 2016, 2, 239–246. [Google Scholar]

- Belton, B.; Karim, M.; Thilsted, S.; Jahan, K.M.; Collis, W.; Phillips, M. Review of Aquaculture and Fish Consumption in Bangladesh. Stud. Rev. 2011, 2011, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, N.K.; Ahmed, M.; Rahman, L.; Das, M.; Bhuiyan, N.A.B.; Ahamed, G.S. Present status of fish biodiversity in wetlands of Tahirpur Upazila under Sunamganj district in Bangladesh. Int. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2018, 6, 641–645. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, B.K.; Mirza, M.J.A. Status of aquatic resources in Someswari River in Northern Bangladesh. Asian Fish. Sci. 2010, 23, 174–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.N.; Kalsoom, S.; Pervaiz, K. Catfishes of the genus Glyptothorax Blyth (Pisces: Sisoridae) from Pakistan. Biol. Soc. Pakistan 2013, 59, 69–83. [Google Scholar]

- Giovos, I.; Stoilas, V.O.; Al-Mabruk, S.A.; Doumpas, N.; Marakis, P.; Maximiadi, M.; Moutopoulos, D.; Kleitou, P.; Keramidas, I.; Tiralongo, F.; et al. Integrating local ecological knowledge, citizen science and long-term historical data for endangered species conservation: Additional records of angel sharks (Chondrichthyes: Squatinidae) in the Mediterranean Sea. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2019, 29, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Datta, S.N. Improvising Indian fishing technology: Modernization, impacts and strategies for sustainable fisheries. J. Exp. Zool. India 2021, 24, 1071–1076. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).