Abstract

This paper examines the intersection between Christian theological principles and contemporary cybersecurity challenges, with a focus on the specific vulnerabilities and responsibilities of faith-based organizations. Recognizing that digital threats emerge not only from technological weaknesses but also from human motives and ethical failings, this study introduces a Biblically Framed Cybersecurity (BFCy) Model that integrates scriptural ethics with established security practices. Through a narrative literature review and comparative analysis, the research synthesizes Christian concepts, such as stewardship, vigilance, and integrity, with technical standards (including the CIS Controls v8, NIST CSF 2.0, and ISO 27001:2022), mapping biblical narratives to contemporary risks like social engineering, insider threats, and identity theft. The findings underscore that robust cybersecurity requires more than technical solutions; it also demands a culture of moral accountability and spiritual awareness. Practical recommendations, including tables linking biblical values to operational controls, highlight actionable steps for church leaders and faith-based organizations. This study concludes that effective cybersecurity in these contexts is best achieved by aligning technical measures with enduring ethical and spiritual commitments, offering a model that may inform religious and broader organizational approaches to digital risk and resilience.

1. Introduction

Cybersecurity concerns continue to intensify as technology, human behavior, and ethical considerations converge (Burton & Moore, 2024; Kure et al., 2022; Saeed et al., 2025). These concerns are likely to continue escalating because of global interconnectivity and the emergence of new technologies. As systems become increasingly reliant on digital platforms, the challenges involved in safeguarding these systems escalate alongside the dangers arising from human behavior (Nobles, 2022; Nobles & Burrell, 2024) and technological factors (Burton & Moore, 2024; Jones & Burrell, 2025; Shadbad, 2021).

The rapid pace and increasing sophistication of cyber threats pose individuals and organizations with ever greater challenges in safeguarding their information, systems, and trust. Cyber risk arises from sociotechnical systems characterized by the interdependence of human behavior and technology. The two parts are fundamentally interconnected, especially within faith-based groups. According to the Ponemon Institute’s (2023) Cost of Insider Risks Global Report, organizations are increasingly recognizing the key role that artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning play in thwarting insider threats. According to the report, 64% of the respondents to a survey stated that technologies played an essential (33%) or significant (31%) role in preventing, investigating, escalating, containing, and remediating incidents originating within their organizations. These responses represent a notable increase from the 54% of organizations that held this belief in 2022. Additionally, 61% of the respondents indicated that automation is very important (38%) or crucial (23%) for managing internal threats within an organization.

The emergence of ethical dilemmas, human factors, and imminent threats necessitates robust cybersecurity measures (Jones, 2024). The cybersecurity industry is anticipated to expand significantly (Saeed et al., 2025), with an overall growth of $5.7 trillion (69.94%) from 2023 to 2028 (Petrosyan, 2023). Furthermore, global cybersecurity expenditures are anticipated to reach $124 billion (Petrosyan, 2022). Given the heightened and irreversible reliance on technology, companies must safeguard the assets essential to operational continuity and overall success (Kure et al., 2022).

Exploiting vulnerabilities through social engineering often involves manipulative, dishonest tactics with significant consequences. According to the FBI, the costs associated with cybercrime reached at least $16 billion in 2024 (Reuters, 2025). Cybersecurity risks vary depending on the nature of the attacks and the vulnerabilities of the assets being targeted. The threat of cyber warfare is a significant concern for corporations, governments, and even charitable organizations such as churches and other nonprofit institutions. In 2023, the average global cost of a data breach was $4.45 million, with sizeable repercussions for industries such as healthcare and finance. Therefore, no organization dependent on the internet is impervious to cybersecurity threats (IBM Security, 2023; Jones, 2021). Likewise, the employees of organizations create vulnerabilities (Nobles & Burrell, 2024; Nobles, 2022).

Thus, although security protocols establish the basis for digital protection, most breaches arise from human vulnerabilities, including deception, betrayal of trust, failure to verify, and the omission of necessary protective measures (Nobles & Burrell, 2024; Nobles, 2022). Every religion involves a doctrine and, in many cases, sacred texts that delineate the beliefs and obligations of its followers (Alkhouri, 2024; Renaud & Dupuis, 2023). Amid the variation among religions and their subdivisions (e.g., Catholic and Protestant Christians), religious groups and denominations typically reach a consensus on their doctrines and behavioral standards.

Subsequently, religious protocols have been established and ratified over time (Alkhouri, 2024; Renaud & Dupuis, 2023). As risks escalate, the need for ethical clarity and discernment becomes paramount (Ephesians 5:15–17 (New International Version, 2011); Jones, 2021; Philippians 1:9–10), especially in organizations that consider trust, stewardship, and accountability essential to their mission. Faith-based institutions, which often operate with inadequate cybersecurity infrastructure, are not exempt (Alkhouri, 2024), as they are increasingly becoming targets due to their financial assets, the personal data they collect, and their inherently trusting nature.

A unique combination of organizational, cultural, and technical factors makes religious institutions and faith-based organizations increasingly susceptible to cyberattacks (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, 2023). Although churches may seem to lack high-value targets, they frequently handle significant amounts of sensitive data, including donor information, financial records, membership databases, and pastoral counseling notes, rendering them “data-rich” (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, 2023; Troilo et al., 2017). However, these institutions often have limited resources to protect their sensitive digital assets (CyberPeace Institute, 2023). Numerous entities lack dedicated cybersecurity staff, robust technical infrastructure, and established strategies to protect these assets (Jones, 2021; Nobles & Burrell, 2024). As a result, they are “defense-poor,” lacking the requisite layered security to counter the increasingly sophisticated cyberattacks (Pattison-Gordon, 2022).

The theological aspects of trust, truth, and moral responsibility, particularly in Christianity, provide a context for recognizing, preempting, and addressing cyber deception. Analogous to the biblical warning about wolves in sheep’s clothing (Matthew 7:15), modern cyber attackers masquerade as legitimate entities to exploit human kindness (Nobles, 2022; Nobles & Burrell, 2024). Social engineers, fraudsters, and insider threats often impersonate credible individuals (Jones, 2021), such as coworkers, supervisors, suppliers, and intimate partners, to exploit trust for personal or organizational gain. Their effectiveness in this regard depends not on brute force but on psychological manipulation, ethical compromise, and trust-exploitation dynamics that scripture continually cautions against (Renaud & Dupuis, 2023).

This research applied biblical teachings to cybersecurity, and similar parallels concerning deceit and ethical consequences can be found in other religious and philosophical traditions (Alkhouri, 2024; Renaud & Dupuis, 2023). The Christian tradition offers a comprehensive moral framework for Christians, grounded in principles such as discernment, stewardship, repentance, and the cognizance of humanity’s fallen nature, which can facilitate efforts to address the ethical challenges posed by technology. However, atonement and forgiveness are attainable, while ethical cybersecurity entails adhering to regulations, acquiring knowledge, being accountable, and advancing morally. Biblical texts suggest that efforts to address issues such as cybersecurity should not assume universal perfection, but rather a pragmatic consideration of human nature. Good stewardship entails accountability for the resources entrusted to individuals, including data and technology, within the biblical framework of stewardship. Individuals must exhibit honesty and transparency, for concealing issues and blaming others are inconsistent with professional ethics.

This study aimed to examine ethics and moral vigilance as essential components of technical security systems by assessing cybersecurity threats through the lens of Christian theology, especially in an era characterized by increasing human-centered vulnerabilities. Cybersecurity need not be confined to algorithms (Nobles & Burrell, 2024; Nobles, 2022) but may also encompass spiritual integrity, ethical culture, and the development of wisdom. By employing scripture-informed judgment, individuals and organizations can enhance their resilience against technical exploitation while preserving moral clarity in a complex digital era (Renaud & Dupuis, 2023).

Key takeaways of this section emphasize that cybersecurity threats are escalating due to the convergence of technology, human behavior, and ethical complexities, particularly in globally interconnected environments and faith-based groups. Organizations face increasing challenges from sociotechnical risks, including insider threats and social engineering that exploit human vulnerabilities and trust, necessitating robust technological safeguards and ethical clarity. Faith-based institutions, which are often “data-rich but defense-poor,” require prudent stewardship and discernment rooted in biblical principles, as theological values like trust, honesty, and accountability frame effective responses to cyber deception. Ultimately, moral vigilance and spiritually informed judgment complement technical controls, empowering organizations to fortify resilience and preserve ethical integrity amid evolving cyber risks

2. Statement of the Problem

Corporations and religious institutions are increasingly vulnerable to external and internal threats. Victims may be exploited by schemes such as pig butchering scams, wherein perpetrators cultivate trust through attentiveness and empathy and persuade their victims to relinquish money or assets with promises of rewards (Burton & Moore, 2024). Organizations may be compromised by “organizational arsonists,” individuals who instigate turmoil, conflict, and dysfunction to further personal goals, acquire power, or influence narratives (Burton, 2025; Jones, 2024; Jones & Burrell, 2025). As mentioned, in 2024, the global cost of cybercrime was approximately $16 billion (Reuters, 2025), with social engineering and deception-based attacks accounting for around one-third of data breaches (Verizon, 2023). Notably, approximately 95% of breaches are attributable to human error or insider activity (World Economic Forum, 2022). In 2023, schemes such as pig butchering resulted in at least $3.8 billion in recorded losses (Burton & Moore, 2024). Despite this empirical evidence, most organizational remedies are primarily technical, offering limited solutions to address the risks posed by human motivations, ethical blind spots, and value conflicts (Nobles, 2022; Nobles & Burrell, 2024). In 2024, around 30% of religious institutions experienced various types of cyberattacks. Nonprofit organizations, including faith-based institutions, now represent the second-most-targeted sector by cyber attackers, comprising 31% of all notifications about nation-state assaults (CyberPeace Institute, 2024; Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, 2025). While comprehensive statistics on cyberattacks against religious institutions are limited, the recorded occurrences and increasing trend underscore the pressing need for enhanced cybersecurity in these institutions.

3. Significance, Importance, and Novelty of the Inquiry

The intersection of religious beliefs and cybersecurity practices is a complex dynamic that influences individuals’ behavior and cognition in the online and spiritual domains alike (Alkhouri, 2024). For Christians, the Bible is the primary source of spiritual, moral, and practical wisdom (2 Timothy 3:16–17; John 3:16; Psalm 119:105). Given the relevance of biblical writings to Christians, valuable insights from this wisdom apply to fields such as cybersecurity, fraud detection, and deception analysis. Thus, this study takes a Christian theological perspective rooted in biblical ethics.

Various chapters and teachings in the Bible are pertinent to modern organizational resilience when analyzed in light of their fundamental messages (Alkhouri, 2024). So, while the Bible does not, of course, mention phishing or malware, it does explore essential themes such as temptation, deception, misplaced trust, and the consequences of erroneous judgment. The discussions of dishonesty, trust, alertness, and ethical compromise in the Bible are highly relevant to modern cybersecurity. This concept paper presents a critical analysis of various biblical narratives and teachings pertinent to cybersecurity, integrating theological and philosophical viewpoints.

The swift evolution of cybersecurity risks poses significant challenges (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, 2023; Office of Intelligence and Analysis, 2025), but fundamental concepts concerning cyber safety, especially alertness, trustworthiness, integrity, and the repercussions of misconduct, align with enduring biblical teachings (Alkhouri, 2024; Renaud & Dupuis, 2023). The gap between these swiftly increasing threats and the frequently neglected notion of lasting comprehension is significant. This raises the question of how companies and individuals can apply core security principles and ethical norms to address and mitigate the challenges posed by the modern threat landscape (Burton & Moore, 2024; Nobles & Burrell, 2024). Businesses must avert the digital equivalent of the Fall of Man, as described in Genesis 3:1–24, by securing themselves against data corruption, trust erosion, and societal harm in a modern context.

This inquiry presents strategies for proactively mitigating the hazards caused by cyber vulnerabilities based on the responses to and safeguards against malevolent intentions described in the Bible (Alkhouri, 2024; Ephesians 6:11–13; Psalm 119:9–11). Burton and Moore (2024) argued that contemporary pig butchering scams exemplify extended social engineering. Victims are gradually manipulated into trusting relationships that lead to financial and psychological exploitation (Burton & Moore, 2024; Ohu & Jones, 2025a, 2025b). In like manner as the serpent presents Eve with ostensibly beneficial knowledge, cybersecurity fraudsters may offer illusory investment returns and promises of amorous satisfaction (Genesis 3:13; Paul et al., 2023).

The theological conclusion is significant: deception leads to brokenness when individuals place their trust in false promises rather than truth. Therefore, organizations and individuals must cultivate technological safeguards and spiritual discernment. God has demonstrated the importance of security measures since the beginning of time (Genesis 3:24; Ephesians 6:11–13; Exodus 25–27; Nehemiah 4:7–9; Proverbs 2:11, 4:23). This emphasis in the Bible on security measures may prompt Christian leaders to investigate cybersecurity strategies that align with scripture. This investigation underscores concepts firmly rooted in Christianity, but as noted, adjacent theologies could adopt this biblical-cyber perspective.

4. Materials and Methods

This study employed a qualitative, narrative review methodology to investigate how Christian theological principles intersect with cybersecurity practice, particularly in relation to organizational resilience and spiritual stewardship. Primary source materials included key biblical passages from the Old and New Testaments of the New International Version (2011). In contrast, secondary sources comprised peer-reviewed journal articles, books, professional reports, and leading cybersecurity standards, such as CIS Controls v8 (Center for Internet Security, 2021), the NIST Cybersecurity Framework 2.0 (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2024), and ISO 27001:2022 (International Organization for Standardization [ISO], 2022).

Literature was gathered using systematic keyword searches (e.g., “cybersecurity,” “Christian ethics,” “religious organizations,” “trust theory”) in major academic databases, including JSTOR, IEEE Xplore, Google Scholar, and relevant organizational archives. The selection criteria limited sources to English-language publications from 2015 to 2025, with an emphasis on studies and guidelines pertinent to ethical, human-centered digital threat management and faith-based institutions.

The research process involved thematic synthesis, identifying, comparing, and integrating biblical concepts (such as stewardship, vigilance, and integrity) with technical controls and operational practices emerging from the cybersecurity standards and empirical studies. The Biblically Framed Cybersecurity (BFCy) Model was developed by systematically correlating scriptural imperatives with concrete security measures from established frameworks.

5. Discussion

5.1. The Intersection of Technology, Human Nature, and Ethics

5.1.1. Technology

Ecclesiastes 7:29 states, “God made mankind upright, but they have gone in search of many schemes.” In scripture, technology, tools, systems, and structure simultaneously serve human progress and rebellion. Thus, in Genesis, humanity is given dominion over creation in a call to stewardship that includes technological innovation to cultivate the world. Later in Genesis 11:1–9, the misuse of a collective technological effort (the Tower of Babel “with its top in the heavens”) leads to fragmentation and divine intervention. This event also explains the basis for diverse languages and is often interpreted as a cautionary tale about pride, unity without purpose, and the defiance of divine boundaries.

Leaders in academic theology must acknowledge that no system can be deemed secure if it neglects the possibility of human or technical fallibility, nor should people depend exclusively on technology. Intervention remains essential in advanced technologies, including AI, artificial general intelligence, and quantum computing. Ecclesiastes 3:11 articulates humanity’s yearning for eternity and the transcendent, thereby underscoring humanity’s distinctive position in the cosmos.

Fascination and rivalry are essential to technological growth, and efficient security models must consider established conventions, accountability, oversight, and continuous evolution (Nobles, 2022; Nobles & Burrell, 2024). There needs to be a balance between technologies that facilitate easier engagement among people and people’s efforts to monitor how technology affects them (Nobles, 2022; Nobles & Burrell, 2024; Shadbad, 2021). Cyber protection is more than just better firewalls. In this context, Colossians 1:17 poses a relevant question about the investment of faith to preserve unity.

5.1.2. Human Nature

Even if technology is flawless, the human component in cybersecurity remains erratic and unreliable. As mentioned, 95% of cybersecurity breaches are attributed to human errors, including susceptibility to phishing schemes, misconfigurations, and social engineering (World Economic Forum, 2022). The technological aspect of cybersecurity constitutes only half of the challenge, for the human element remains a variable that is unpredictable and challenging to forecast and control.

Jeremiah 17:9 presents the profound theological insight that humans are predisposed to self-deception, moral decay, and imprudent choices. This predisposition extends beyond mere spiritual awareness to inform tangible actions in cybersecurity. Scams such as phishing, spear-phishing, and baiting exploit victims’ trust, haste, anxiety, and curiosity (Burton & Moore, 2024; Hadlington, 2018; Nobles & Burrell, 2024). Well-disposed employees in organizations can represent a vulnerability, for stress, exhaustion, or resentment may lead an individual to engage in deliberate or inadvertent malevolent conduct (Burton & Moore, 2024; Hadlington, 2018; Nobles, 2022; Nobles & Burrell, 2024; Shadbad, 2021).

No system can completely predict or control this randomness. Multifactor authentication and least-privilege access do not merely account for likely errors but expect them. Training should assume that users are distractible, overconfident, and susceptible to manipulation. Confronting cybersecurity risks involves addressing technical components, such as faulty configurations and flawed code, and establishing controls to guard against humans’ flawed nature. Researchers have argued that there is value in learning from the established best practices of other disciplines that also depend on human actions (Renaud & Dupuis, 2023). This is a compelling argument, especially considering that cybersecurity is a relatively young discipline that has yet to address the complexities of human nature and error fully. Other disciplines have decades, if not centuries, of experience addressing problems that arise in modern business when workers deviate from established guidelines and propagate vulnerabilities throughout an organization.

5.1.3. Ethics

Business ethics is not a novel concept. In a study published more than 40 years ago, management expert Peter F. Drucker (1981) acknowledged the significance of ethics in business (Hoffman & Moore, 1982), asserting that it transcends the call for repentance from religious leaders. In business ethics, stakeholders are defined as the individuals, groups, and entities that are affected by or can influence an organization’s decisions, actions, or policies (D’Cruz et al., 2022). Business ethics is relevant not only to shareholders and investors but also to a diverse array of entities, including employees, consumers, suppliers, government agencies, local communities, and future generations.

From the perspective of biblical ethics, cybersecurity constitutes not just a problem of safeguarding but also an obligation. Jeremiah 17:9, cited above, acknowledges that human fallibility involves the ethical responsibility to hold individuals accountable without demanding perfection from them. Organizations must transcend superficial evaluations, focusing on discerning behavioral patterns over time and distinguishing between honest and fraudulent acts. In this verse, the prophet Jeremiah asks, “The heart is deceitful above all things and beyond cure. Who can understand it?”

This inquiry prompts contemporary practitioners to recognize the limitations of technology when it comes to identifying malicious intent. Ethical vigilance, behavioral analytics, and ongoing monitoring are essential to identify patterns that reflect deeper realities obscured by superficial validity. Humanity must not succumb to the despair of a constantly evolving technological cybersecurity landscape. Instead, efforts should be made to establish systems, cultures, and laws that acknowledge and mitigate the inherent flaws in human nature. Biblical ethics posits that human nature is intrinsically flawed, predisposed to greed, rationalization, and short-term thinking, which have obvious implications for cybersecurity. Jeremiah 17:9 and Romans 3:23 illustrate that ethical frameworks cannot rely exclusively on good intentions but must acknowledge the inherent human propensity for failure.

5.2. Cyberattacks on Faith-Based and NGO Institutions (2024–2025)

The cybersecurity vulnerabilities and increased risks identified in faith-based and non-governmental organizations highlight deeper systemic issues pertinent to the manuscript’s primary focus on sector-wide threat awareness and resilience. Providing tangible, recent examples of these sector-specific threats underscores the urgency of preventive steps and affirms the necessity of ongoing security focus among administrators, policymakers, and stakeholders.

The following current data and trends evidence the escalating threat of cyberattacks:

- Faith-based organizations and charitable entities remain high-risk targets for cybercrime, with threat levels officially classified as “elevated” since July 2025. National bodies overseeing this sector have advocated for increased vigilance in light of the persistent occurrence of ransomware, phishing, doxing, and similar threats (Office of Intelligence and Analysis, 2025). Global conflicts and domestic extremist activities have increased these risks.

- Faith-based organizations can present attractive targets for perpetrators (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, 2023; Office of Intelligence and Analysis, 2025) due to their limited security measures, high-trust cultures, the availability of the information they collect, and their reliance on volunteers. Recent reports indicate that social engineering, email intrusion, and ransomware are particularly prevalent, utilizing insider threats and digital fundraising platforms as entry points (Burton, 2025; Verizon, 2023).

5.3. Recent High-Profile Incidents Involving Faith-Based and Non-Governmental Organizations

Faith-based and non-governmental groups have increasingly been targets for cybercriminals and ideologically driven threat actors. Recent high-profile breaches have highlighted the vulnerability of these institutions, underscoring the intersection of physical and cyber risks and their potential impact on operational continuity and personal safety. These examples illustrate that even prominent and globally respected institutions are susceptible to sophisticated attacks and targeted abuse. The following are some recent cybersecurity breaches.

- A prominent Catholic publisher, Relentless Church, and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints experienced cyberattacks resulting in the exposure of critical information about members and personnel (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2022).

- A sophisticated cyberattack on the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in 2022 compromised the personal information of more than 500,000 individuals who depended on its humanitarian services, demonstrating that not even globally esteemed faith-based non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are impervious to such threats (International Committee of the Red Cross, 2022).

- Manifestos and explicit threats targeting individual churches, such as a July 2025 event in Boise, Idaho (Gryder, 2025), underscore a connection between physical and cyber threats, which are frequently driven by ideological motives, with pre-incident indicators prompting law enforcement apprehension.

5.4. Sector-Wide Observations

Recent developments indicate that the cybersecurity landscape for faith-based organizations is marked by intensified targeting and greater susceptibility. Religious institutions, regardless of their size or denomination, face a range of complex risks that highlight the pervasive nature of these challenges across the sector. Incidents of data breaches, ransomware, and ideologically driven attacks highlight systemic concerns that necessitate a collaborative focus from leaders and security experts within this community.

The following examples illustrate the types of cybersecurity concerns currently affecting various faith-based entities:

- Email compromise, the primary attack vector for faith-based and charitable groups, has intensified because of the increased use of digital fundraising tools and platforms (Cyber Command, n.d.).

- From 2024 to 2025, the global incidence of ransomware attacks increased by more than 120%, with churches, ministries, and Christian publications increasingly facing ransom demands, operational disruptions, and data loss (Firch, 2025).

- Nation-state and hacktivist activity is also a concern, for pro-Iranian and other state-affiliated forces, as well as ideologically driven domestic radicals have targeted Jewish, Christian, and Islamic organizations amid the ongoing geopolitical crises.

5.5. International Perspective

These challenges are not limited to religious organizations in the United States, as the following examples indicate. Two international perspectives on cybersecurity challenges are provided:

- Cybersecurity threats are increasingly globalized, with incidents recorded in North America, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, particularly in the United States, Switzerland, the Vatican, and Israel, including attacks on humanitarian organizations.

- The NGO sector lags in preparedness; thus, 56% of NGOs lack a cybersecurity budget, and around 70% are unprepared to address substantial cyber incidents (CyberPeace Institute, 2024). The tendency for small Christian communities to use donated or outdated equipment and shared or insecure passwords increases their vulnerability.

Table 1 delineates essential global and regional statistics that contextualize the existing cybersecurity landscape, emphasizing the magnitude, prevalence, and repercussions of cyber incidents across various sectors and regions. Note that the table includes quantitative data from differing types of organizations (e.g., NGOs, nonprofits, religious institutions, and faith-based institutions) and geographies. This table consolidates recent statistics on attack prevalence, financial losses, and sector-specific vulnerabilities. It provides an empirical basis for comprehending the urgency and scope of cybersecurity concerns. These data offer critical context for managing organizational risk and justify adopting more resilient, culturally sensitive security methods, particularly in faith-based and mission-driven enterprises.

Table 1.

Global and Regional Statistics.

Globally, NGOs, including faith-based organizations, face a persistent and intensifying threat environment (CyberPeace Institute, 2024; Gryder, 2025; SC Media, 2024) created by criminal and state-sponsored entities (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, 2023; Office of Intelligence and Analysis, 2025). Recent data sources have confirmed that these institutions are experiencing unprecedented targeting, with attackers exploiting resource constraints, high-trust settings, and digital security deficiencies (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, 2023; Office of Intelligence and Analysis, 2025). The effects are extensive, influencing economics, member confidence, and personal safety, highlighting the pressing need for customized security measures and resource distribution.

The widespread implications of cybersecurity underscore the importance of acknowledging that users, developers, and executives may make poor judgments despite having good intentions. Therefore, controls, accountability, and robust policies are essential. Religious organizations and other NGOs regularly manage substantial financial assets and collect confidential personal data from their followers, but often lack adequate cybersecurity measures and are vulnerable to cybercriminals seeking financial gain (CyberPeace Institute, 2023, 2024; Roberts, 2023). Roberts (2023) characterized religious institutions as appealing targets for cybercriminals because of three factors: (a) they are “data rich, defense poor” (cf. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, 2023; Pattison-Gordon, 2022; Troilo et al., 2017), (b) they typically possess financial reserves, and (c) they are characterized by inherent trust among their members.

5.6. Relevant Theories and Conceptual Frameworks

Divine command theory posits that cybersecurity responsibilities supersede professional duties and are moral imperatives derived from divine authority. Strategies designed to avoid data breaches, mitigate fraud, and protect users’ privacy align with moral imperatives against deception, betrayal, and carelessness (Máhrik & Králik, 2024). Cyber transgressions, such as willful insider threats and unethical hacking, may also be regarded as moral violations of divine will rather than simple malicious intent. Conversely, virtue ethics underscores the cultivation of moral character traits such as honesty, prudence, and courage that are considered fundamental to ethical conduct in cybersecurity. In high-risk or uncertain situations, these traits enable professionals to behave with moral clarity, particularly in the absence of specified constraints. These concepts collectively provide complementary frameworks. Thus, divine command theory emphasizes the sanctity of ethical behavior, whereas virtue ethics prioritizes the development of essential character traits for reliable and responsible cybersecurity practices.

Other pertinent conceptual frameworks are examined here, including Erving Goffman’s dramaturgical model, interpersonal deception theory (IDT), moral disengagement theory, and trust theories.

- Erving Goffman’s dramaturgical theory likens social life to a theatrical performance wherein individuals perform roles to influence the perceptions of others (Smith, 2016). The “frontstage” refers to public conduct that conforms to cultural expectations, whereas the “backstage” reveals concealed intentions and preparations. For Goffman, identity is malleable and adaptable to social settings (Smith, 2016). In cybersecurity, this concept refers to the techniques employed by hackers to create convincing digital communications, such as phishing emails or romance scams, to exploit victims. The precise identities of the perpetrators remain concealed while they conspire in clandestine forums, crafting narratives and utilizing psychological manipulation covertly. This behavior parallels that of biblical heroes such as Jacob, who plotted covertly before public action. Goffman’s paradigm underscores the performative nature of cyber deception, thereby augmenting the contrast between biblical and contemporary acts of dishonesty.

- Interpersonal deception theory (IDT) highlights the fluidity of deception in speech, paralleling biblical accounts that feature conversational trickery (e.g., the serpent and Eve). This amalgamation of interpersonal communication and deception theories provides a comprehensive awareness of deception in interactive contexts (Buller & Burgoon, 1996). In cybersecurity, IDT denotes subversive strategies employed by cyberattackers, such as phishing and social engineering. Establishing these links can enhance the sophistication and precision of cybersecurity analogies. Thomas and Biros (2020) showed that it is feasible to differentiate between truthful and dishonest conduct, with behavioral patterns emerging over time.

- Moral disengagement (Bandura, 1990) elucidates how individuals rationalize unethical conduct, making it especially pertinent to insider threats and ethical violations in cybersecurity. This concept aligns with biblical teachings on the justification of sin, thereby enhancing the theoretical complexity of the discourse on “guarding the gates.”Trust theories facilitate the systematic comprehension of the components of trust, namely ability, kindness, and integrity (Schoorman et al., 1996), which are crucial in religious and cybersecurity contexts. In theology, reliance on divine character signifies dependence on moral purity, whereas in cybersecurity, trust regulates access, authentication, and risk management. These characteristics reveal weaknesses in human and system interactions and underscore the need for reliable conduct and frameworks. Because trust theory facilitates the evaluation of the trustworthiness of entities, whether divine, human, or digital, it is a practical framework for addressing deceit, identity verification, and ethical congruence in spiritual and technological contexts.The following discussion delineates some parallels between biblical narratives and cybersecurity.

5.7. Limitations

While this article offers a robust conceptual foundation, its arguments remain circumscribed by a series of consequential boundaries. These methodological and contextual delimitations, ranging from the singular focus on a Christian paradigm and the absence of empirical validation to the insufficient engagement with technological, legal, and intra-faith complexities, simultaneously testify to the promise and unfinished agenda of this research. Nuanced considerations such as organizational heterogeneity, evolving threat vectors, and the distinct vulnerabilities of marginalized faith communities reveal a landscape far richer and more variegated than a singular theological lens can encompass. By articulating these points of tension and omission, the discourse not only exemplifies scholarly transparency but also charts a forward-looking topography for interdisciplinary research, practical innovation, and deeper engagement at the contested intersection of faith, ethics, and digital security. Each of the following limitations links to the paper’s thematic construct, highlighting where additional depth, broader inclusivity, or methodological expansion would substantively strengthen its practical application.

- Christian Paradigm Exclusivity. The study is primarily anchored in Christian theology, which may limit its universal applicability. Limited engagement with non-Christian or secular ethical frameworks may not reveal unique and convergent dynamics in cyber-ethical stewardship that could address cross-cultural generalizability.

- Theological Diversity and Intra-Faith Disputes. Christian denominations and communities differ on many theological, ethical, and interpretive issues. The BFCy Model may not yet fully account for these internal distinctions or disagreements about scriptural application in digital contexts.

- Empirical, Quantitative Validation. The effectiveness of the Biblically Framed Cybersecurity (BFCy) Model in changing behaviors or reducing risk remains unquantified and thus open to further validation. Limitations exist regarding the operationalization of the model.

- Scriptural Analogy. While drawing analogies between biblical narratives and modern cyber threats provides rich theological resonance, it may oversimplify the technical complexities of cybersecurity, necessitating a deeper critical-technical analysis in parallel.

- Organizational Scale and Context. There are limitations in rigorously addressing variations in organizational size, structure, or resources, which could significantly affect the adoption and impact of the current model.

- Consideration for Legal and Regulatory Divergence. Specific legal mandates (e.g., GDPR, HIPAA, or region-specific data privacy regulations) may pose practical challenges for faith-based organizations operating in varied jurisdictions.

- Evolving Threat Vectors and Technological Adaptability. Scriptural principles were not the specific focus in terms of agility in responding to new classes of attack (e.g., polymorphic malware, AI-enabled threats).

- Exploration of Human Factors Outside Theological Context. The study is limited in its consideration of the psychological, cognitive, or social factors that could significantly enhance understanding of cybersecurity behaviors beyond spiritual examination.

- Intersectionality of Diverse Religious Communities. The distinct hazards, resource limitations, and socio-political vulnerabilities encountered by marginalized, minority, or persecuted religious groups in cyberspace are limited in their scrutiny.

- Systematic Framework for Execution and Evaluation. Organizations would need to customize a formal, iterative procedure for assessing the progress, outcomes, and ongoing enhancement of the BFCy Model in organizational practice.

- Key takeaways of this section reveal that faith-based and NGO institutions face a highly intensified and evolving cyber threat landscape, mainly due to resource constraints, high-trust environments, and underdeveloped digital defenses. Theologically rooted models stress that cybersecurity is not merely a technical or professional duty but also a profound moral imperative governed by divine command and the cultivation of virtuous character traits. Psychological manipulation and social engineering tactics are used to exploit organizational structures and individual trust, echoing biblical narratives and sociological frameworks. However, current research is bound by notable limitations, including its exclusive focus on Christian paradigms, absence of broad empirical validation, and insufficient accommodation of organizational, legal, and cross-cultural complexities. This underscores the need for interdisciplinary inquiry and continuous adaptation of ethical and practical frameworks in the realm of digital security.

6. Results

6.1. Cybersecurity Threats and Controls Analogous to Biblical Themes

This discussion focuses on seven cybersecurity analogies to biblical references and lessons. Each biblical account is paired with cybersecurity analogies to offer detailed insight into the shared themes and risks. The following parallels are drawn solely from Christian scripture, but other faiths may offer valuable analogies that are worthy of future exploration, though outside the scope of this model. Table 2 presents a cohesive array of examples demonstrating how biblical narratives reflect modern cybersecurity threats and associated defense mechanisms. By examining these scriptural accounts alongside contemporary digital risks, the table facilitates the extraction of actionable insights that can inform the formulation of successful cybersecurity practices, especially within faith-based contexts. This method highlights the importance of fundamental religious teachings in fostering proactive and ethically sound responses to emerging cyber threats.

Table 2.

Biblical Narratives and Analogous Cybersecurity Threats and Controls.

Faith-based organizations face several cybersecurity dangers that compromise their operations and confidentiality, while also reflecting patterns and teachings from scriptural texts. By comparing modern cyber occurrences to core scriptural events, the greater relevance and severity of these risks are contextualized in a manner that profoundly connects with religious communities.

The following comparative analysis of biblical narratives and analogous cybersecurity threats and controls illustrates the parallels between specific biblical accounts and current cybersecurity challenges, along with relevant preventative strategies. This analyzes scripture tales alongside contemporary cyber hazards and controls, offering a framework to understand how timeless teachings from religious texts might enhance digital risk management techniques in faith-based enterprises and beyond. The subsequent elaborated examples illustrate how these similarities might guide and motivate a cohesive response to cybersecurity challenges.

6.1.1. Biblical Narrative 1: The Temptation and the Fall

- Text: Genesis 3:13. “Then the Lord God said to the woman, ‘What is this you have done?’ The woman said, ‘The serpent deceived me, and I ate.”

- Event: Eve succumbs to the serpent’s attack and is led to defy God’s order

- Social Engineering and Deception:

- 𝚘

- Cyber Relevance. Eve’s succumbing to the serpent’s attack allows for a damaging compromise of humanity (the Fall). The Fall is analogous to social engineering: an attacker (the serpent) uses trust and curiosity to drive behavior.

- 𝚘

- Data-backed Insight. Social engineering attacks have been among the most common causes of non-insider data breaches, accounting for 53% of such incidents (Ponemon Institute, 2023).

- 𝚘

- Critical Synthesis. In Genesis, the serpent convinces Eve to eat from the forbidden tree by questioning her comprehension of God’s order and offering her hidden knowledge. Persuasion, false promises, and manipulation also entice Eve. The sin (failure), loss of innocence, and awareness of Eve’s and Adam’s vulnerability have momentous consequences (Genesis 3:13). This account is a timeless example of psychological manipulation, with the assailant exploiting curiosity, trust, and the need for empowerment. Today’s attackers employ many of the tactics used throughout the ages, so a coordinated response to malicious activity is still needed (Burton, 2024). Cyber attackers deceive victims by convincing them to violate established norms that help ensure safety, security, resilience, and strategic survivability. In like manner, Adam and Eve realize their mistake too late and attempt to conceal their wrongdoing once they become aware of their mistake. Employees are expected to operate according to established conventions communicated through managerial, administrative, and technical controls, and thus are required to report errors, when necessary, rather than hiding them (Jones, 2024). However, as the experience in the Garden of Eden shows, it is not inconceivable or even uncommon for human curiosity to prevail over expectations.

6.1.2. Biblical Narrative 2: Guard Your Heart

- Text: Proverbs 4:23. “Above all else, guard your heart, for everything you do flows from it.”

- Event: The exhortation to diligently guard one’s heart.

- Vigilance and Access:

- 𝚘

- Cyber Relevance. When protecting the body, protection of the heart is the most vital task because it is the foundation of everything that defines life. The heart is central to sustaining life. In cybersecurity, controlling access is crucial because organizations must persistently defend the core of their operations and valuable assets, as their status influences the overall integrity of the system.

- 𝚘

- Data-backed Insight. Eighty-four percent of organizations have experienced an identity-related breach, and 96% believe that these breaches could have been prevented with better identity-focused security measures (Identity Defined Security Alliance, 2023).

- 𝚘

- Critical Synthesis. Guarding the heart involves being mindful of what individuals allow into their minds and what influences their inner selves. Likewise, who or what is provided with access to a network directly influences its condition and assurance. Like a fundamental tenet of security design, Proverbs 4:23 emphasizes proactive protection. Those with authorized access who are entrusted with elevated privileges may make mistakes or abuse trust. In addition, workers often inadvertently provide credentials to attackers owing to a lack of awareness or verification (Hadlington, 2018; Nobles & Burrell, 2024; Triplett, 2022), thereby giving assailants access to parts or all of an organization’s network. Systems must be constructed with the defense-in-depth security strategy to safeguard the core from unauthorized access. A single data breach can lead to a 7.5% decline in customer trust and brand reputation (Harvard Business Review, 2023; IBM Security, 2023), with recovery taking years (Roering, 2014). Just as protecting the heart is important for an individual’s spirit and morals, protecting identity and access systems is key to strong cybersecurity. Breaches often happen because access controls are ignored, while being careful at the center stops large-scale digital problems. Activities such as following prescribed policies and guidance, seeking clarification, and maintaining cybersecurity awareness mimic the biblical call to spiritual vigilance.

6.1.3. Biblical Narrative 3: Jacob Imitating Esau

- Text: Genesis 27:1. “When Isaac was old and his eyes were so weak that he could no longer see, he called for Esau, his older son, and said to him, ‘My son.’ ‘Here I am,’ he answered.”

- Event: Jacob uses disguise (imposter risk) and manipulation (trickery) to receive his father’s blessing, which is intended for his brother, Esau.

- Identity Theft, Impersonation and Scams:

- 𝚘

- Cyber Relevance. Today’s cyber landscape is replete with methods for impersonating identities, including fake social media profiles, phishing attacks, business email compromise, deepfakes, spoofing, and synthetic (combining real and fake information) identity fraud. This kind of identity theft occurs when someone pretends to be someone else to scam individuals for their benefit.

- 𝚘

- Data-backed Insight. Ninety-five percent of breaches have been attributed to human error (Mimecast, 2025).

- 𝚘

- Critical Synthesis. This incident highlights the dangers and magnitude of loss associated with inadequately verifying an identity. Jacob is able to scam his father, Isaac, because Isaac’s eyesight (awareness) fails him. While Isaac touches Jacob’s hands and neck to ensure that he is blessing Esau (the rightful son, who is authorized to receive the blessing and whose skin is hairy), Isaac’s authentication process is thwarted by Jacob’s scam. In this situation, Jacob presents a false positive by covering himself with goat hair. The multi-factor authentication process fails as the first control (something known provides recognition on sight, a human factor), and the second control (a physical attribute, i.e., fake hairy skin) is not authentically validated but assumed so. Isaac is completely duped, and Jacob maliciously steals Esau’s blessing.

- 𝚘

- The application of this learning to cybersecurity illustrates the critical need for genuine authentication measures to avoid identity theft, impersonation, and scams. In the cybersecurity realm, credential theft incidents have averaged $679,621 per incident (Ponemon Institute, 2023). The goal of credential thieves is to steal users’ credentials, which provide access to critical data and information. Further, adverse insiders have accounted for an average of 6.2 incidents experienced between early 2022 and early to mid-2023, and the median cost for such incidents was calculated to be $701,500 (Ponemon Institute, 2023). The people, processes, and technologies of organizational systems can be exploited if confidence is gained without the use of proper controls.

6.1.4. Biblical Narrative 4: Judas as the Moneybag Keeper

- Text: John 12:6. “God made mankind upright, but they have gone in search of many schemes.”

- Event: Judas uses his role and access to help himself to funds in the communal bag.

- Insider Threat:

- 𝚘

- Cyber Relevance. As keeper of the money bag (also referred to as the money box), Judas is an insider threat. He operates inside the system deliberately, using his role-based access for personal gain.

- 𝚘

- Data-backed Insight. Sixty percent of security breaches involve insiders (IBM Security, 2023).

- 𝚘

- Critical Synthesis. Betrayal is conceivable even in close circles, and the legal dimensions of insider threats are vast and multidimensional (Jones & Burrell, 2025). Hence, zero-trust models are especially important. There is growing empirical evidence connecting the psychological profiles of internal and external threat actors to the so-called “dark triad” of personality traits, namely Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy (Ohu & Jones, 2025b). Just as Judas was the keeper of the money box, individuals entrusted with managing organizational assets can willfully misuse possessions and hide evidence of doing so. Insider threats involve people who work for an organization and have a propensity to engage in actions that expose or misuse information; thus, they pose serious challenges to contemporary businesses (Jones, 2024). Insiders are assigned credentials that allow access to assets, so their responsibilities can carry financial, operational, reputational, and other risks. Organizations must implement controls, checkpoints, and audit procedures to identify and prevent the adverse actions of insider threats.

- 𝚘

- The challenges posed by insider threats require responses that go beyond conventional, reactive cybersecurity measures (Jones, 2024). Integrating multidisciplinary insights from psychology, criminology, organization, and cybersecurity is a promising strategy for effectively identifying and mitigating these complex threats. As the keeper of the bag, Judas Iscariot can collect money, misinform about the status of that money, and help himself as desired. He can commit collusion and take advantage of the situation. In cybersecurity, these factors are significant for establishing a strong control environment (e.g., segregation of duties). No single individual should have excessive privileges or the ability to access various accounts, creating situations in which they can commit fraud, waste, and abuse, and then hide the evidence by exploiting the accounts. A notable recent insider threat to a religious organization involving financial malfeasance is the case of Joseph Meisch, the former business manager of St. Patrick’s Church in New Orleans. In September 2020, Meisch was charged with wire fraud after he embezzled more than $329,000 from church accounts. He used church credit cards for personal expenses and transferred church money to his personal bank accounts, abusing the trust the congregation had placed in him. This incident is reminiscent of the betrayal of Judas, in which a trusted member, Meisch, abuses his authority to gain personal advantage at the expense of the church. This incident underscores the fact that insider threats in religious organizations can cause moral and financial damages, paralleling those in secular organizations. Having well-documented processes and following efficient audit procedures can reduce the risk of collusion.

- 𝚘

- In some cases, malicious behaviors are reportable offenses that carry fines, penalties, and a reputational impact that can be financially incalculable. Insider threats make zero-trust architectures a necessity. Disinformation exemplifies how deceit works against governance. Limited privilege is essential to limit the negative consequences, in like manner as Eden’s walls safeguard purity. Accountability can involve audit logs and digital forensics that provide traceability and ethical stewardship in cyberspace.

6.1.5. Biblical Narrative 5: Misrepresented Truth

- Text: Proverbs 14:15. “God made mankind upright, but they have gone in search of many schemes.”

- Event: Disguising their appearance to seem harmless, the Gibeonites use misinformation and deception to exploit the trust of the Israelites.

- Data Integrity and Misinformation:

- 𝚘

- Cyber Relevance. Misinformation involves false information, and disinformation efforts, including data integrity issues, seem credible but are harmful. These activities use convincing deceptions to induce individuals to comply with threat actors’ desires.

- 𝚘

- Data-backed Insight. More than 70% of organizations report having been targeted by misinformation campaigns (World Economic Forum, 2022).

- 𝚘

- Critical Synthesis. The Israelites have a decree to eliminate the inhabitants from the land. Thus, the Gibeonites, who are their neighbors, wear old clothes and carry moldy bread to disguise themselves as travelers rather than inhabitants. The Israelites “believed every word” provided to them by the Gibeonites without scrutiny or divine consultation. Thus, the Gibeonites can trick (or spoof) the Israelites. The Gibeonites’ claims represent a layer of their breach strategy. Their deception mirrors the tactics of false prophets, manipulating appearances and words to bypass scrutiny and exploit trust. Just as the Israelites’ signs mislead the Israelites, modern cyber threats depend on social engineering and disinformation. The Bible warns against naivety and emphasizes discernment (Proverbs 14:15), a virtue reiterated in cybersecurity procedures such as validation, verification, and threat intelligence. False prophets, threat actors, and attackers in the cyber domain construct narratives of persuasion to exploit vulnerabilities. Matthew 7:15 warns, “Beware of false prophets, which come to you in sheep’s clothing, but inwardly they are ravening wolves.” Spiritual and digital discernment are thus equally vital to protecting the integrity of communities, whether sacred or virtual. The Bible warns against gullibility and emphasizes discernment and the capacity to evaluate life forces and establish the truth. Likewise, cybersecurity stresses threat intelligence, reputation checks, and validation to guard against misinformation, which can be detrimental depending on the vulnerability being exploited. From insider threats to state-sponsored attackers, misinformation can be used to deceive and act on malicious intent. False appearances and words lead to misguided promises, so exercising sound judgment is essential.

6.1.6. Biblical Narrative 6: The Tree of Knowledge

- Text: Genesis 2:16–17. “And the Lord God commanded the man, ‘You are free to eat from any tree in the garden, but you must not eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, for when you eat from it you will certainly die.”

- Event: Adam and Eve are deceived into eating from the Tree of Knowledge and receive calamitous consequences.

- Principle of Least Privilege (PoLP):

- 𝚘

- Cyber Relevance. Overreach leads to systemic failure. Operating based on the PoLP is a safeguarding practice. In Genesis, the injunction against eating from the Tree of Knowledge establishes a boundary for maintaining things in balance. In cybersecurity, the PoLP is an echo of this establishment of a boundary: providing too much access increases threats, permits insider attacks, privilege misuse, and severe security violations.

- 𝚘

- Data-backed Insight. Eighty percent of breaches can be prevented by proper application of the PoLP (CyberArk, 2023).

- 𝚘

- Critical Synthesis. The PoLP is an important principle of security according to which users, programs, or systems should only be allowed to access the bare minimum of resources necessary for their purposes. The principle involves minimizing the risk of serious consequences from a security issue by making attacks difficult to achieve and preventing the spread of malware. By granting users and systems the minimum access that they need, organizations can minimize the risk of security intrusions resulting from breached accounts with extensive privileges. In a biblical context, this principle mirrors the restricted access granted in the Garden of Eden. For their own protection, Adam and Eve are instructed not to eat from the Tree of Knowledge (Genesis 2:16–17). They do not have “a need to know” specific information. However, because they are prime targets, they are deceived and give in to the opposition. The breach in the Garden of Eden changes the course of humanity’s earthly sustainability and its lifecycle. Limiting access serves as a safeguard against potential transgressions. The PoLP also applies to knowledge-sharing since information can be used maliciously. Judges 16:4–21 describes how Delilah uses social engineering tactics (trust and questioning) to discover the secret of Samson’s strength (i.e., his hair), ultimately gaining access to critical information and using it to compromise him. Ignoring such boundaries as the PoLP can lead to dire consequences. This story illustrates the importance of adhering to defined limits to maintain integrity and security. By connecting modern cybersecurity measures with timeless biblical principles, organizations can cultivate a culture of awareness and moral obligation.

6.1.7. Biblical Narrative 7: Review of Decisions and Actions

- Text: Revelation 20:12. “…and books were opened. Another book was opened, which is the Book of Life…. The dead were judged according to what they had done as recorded in the books.”

- Event: The final review of choices and actions in alignment with divine standards.

- Audit and Accountability:

- 𝚘

- Cyber Relevance. Revelation 20:12 reflects the cybersecurity principle of auditability and traceability, as systems log and examine activities for justice and accountability. Since no act is invisible to divine judgment, no privileged act in secure systems needs to be unrecorded or non-auditable. Record-keeping must be maintained through audit logs backed by immutable records.

- 𝚘

- Data-backed Insight. 279 companies (8%) revealed material deficiencies in their 2023/2024 annual reports out of 3502 total. Lack of documentation, rules, and processes; accounting resources or knowledge; IT/software/access concerns; segregation of duties/design controls; and insufficient disclosure controls were the top five problems causing major weaknesses.This indicates that one of the main underlying causes of material weaknesses, which are significant accountability issues, is insufficient documentation (i.e., poor record-keeping/audit trails) (The Corporate Counsel, 2025).

- 𝚘

- Critical Synthesis. Divine inquiry models ethical accountability in that all actions are traceable before God. Accordingly, there will come a time when acts performed are assessed for their integrity. Revelation 20:12 speaks of a final judgment according to a perfect record called the Book of Life. Modern cybersecurity controls utilize secure and immutable audit trails so that all actions are accounted for and traceable. This theme recurs in blockchain technology, zero-trust networks, and forensic logging in cybersecurity, where systems that do not forget maintaining accountability and trust. Transparency and accurate records are essential in domains to ensure that intent and action align and that repercussions follow from substantiated behavior, not just the appearance of implications. The Book of Life illustrates perfect traceability, being analogous to the need for tamper-proof logs that hold users and systems accountable for actions taken under their identities. In the domains of religion and the internet alike, genuine justice hinges on what is recorded rather than what is stated. The Book of Life exhibits impeccable tracking, as evidenced by the use of irreversible records that hold individuals and systems accountable for actions carried out in their name.

6.2. The Biblically Framed Cybersecurity (BFCy) Model

The BFCy Model is fundamentally rooted in scripture, while also drawing conceptually on divine command theory and virtue ethics. These ethical frameworks enhance the model’s robustness by establishing a moral foundation. The model reconceptualizes cybersecurity from an embedded, faith- and values-based perspective, thereby enhancing cyber governance and organizational resilience. This foundational framework for safeguarding digital assets merges religious principles with cybersecurity methodologies. It indicates that cybersecurity transcends technical concerns, as it involves adapting to the overarching policies and ethical frameworks that enterprises, their personnel, and the stakeholder community must contemplate. The rapid advancement of technologies makes leaders susceptible to the dangers of adhering to outdated techniques and methodologies, which can cause significant difficulties (Aridi et al., 2024; Burrell, 2018).

The BFCy Model is, then, an innovative methodology that amalgamates biblical tenets with modern cybersecurity approaches to establish a comprehensive framework for digital safeguarding. The paradigm interprets cybersecurity as a spiritual duty by referencing scriptures that emphasize stewardship, honesty, vigilance, justice, and compassion in order to protect data and the dignity, trust, and welfare of the individuals it represents. The repercussions of a cyberattack on a religious institution extend beyond the digital realm, manifesting in tangible impacts on its core principles. Financial theft, whether directly from institutional finances or by members through fraudulent emails, can disrupt operational activities and impede core objectives (Maurer & Nelson, 2021). The BFCy Model shows academic theologians that cybersecurity awareness can be enhanced through a practical and scriptural foundation.

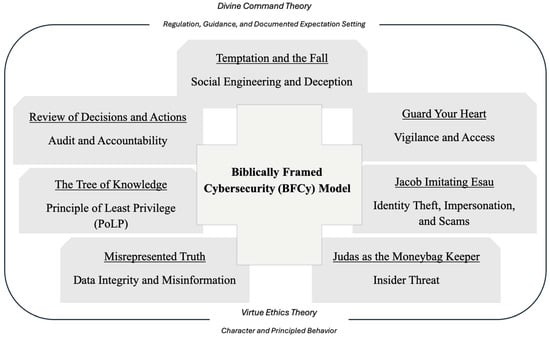

Based on the empirical data provided by the global and regional cybersecurity statistics in Table 1, Figure 1 presents the Biblically Framed Cybersecurity (BFCy) Model. This conceptual framework combines enduring ideas from biblical texts with modern cybersecurity tactics, providing a culturally relevant and ethically sound approach to digital risk management. The BFCy Model underscores the cohesive integration of spiritual values with technological defense systems, seeking to bolster organizational resilience and community trust. The integration of biblical principles with cybersecurity practices centers on embedding ethical, spiritual, and moral values into the foundational culture of technological defense systems. The BFCy Model emphasizes this fusion as a means to enhance organizational resilience and foster enduring trust within communities.

Figure 1.

The Biblically Framed Cybersecurity (BFCy) Model. Note. The author of this paper created this figure.

Biblical teachings such as stewardship, vigilance, and integrity are viewed as aligning with essential cybersecurity values. For instance:

- Stewardship is reflected in the responsible management and safeguarding of digital assets and data.

- Vigilance is mirrored in proactive monitoring and defending against threats, echoing biblical admonitions to “watch and pray.”

- Integrity shapes policies around confidentiality and honest reporting of vulnerabilities, parallel to scriptural mandates for truthfulness and transparency.

The BFCy Model, while grounded in Christian scripture and ethics, may offer adaptable elements for other faith-based or ethical frameworks. Nonetheless, generalization beyond Christian institutions should be approached with meticulous modification and in collaboration with practitioners or researchers from those traditions. This paper does not assert general applicability and presents the concept mainly as a resource for Christian groups, unless further research or collaborative adaptation provides additional evidence.

The approach integrates scriptural knowledge, behavioral insights, and operational cybersecurity practices, providing a strategic framework for faith-based and mission-driven companies. It promotes a comprehensive concept of cybersecurity that extends beyond just technical solutions, emphasizing stewardship, honesty, vigilance, and community protection as fundamental foundations of effective defense. Figure 1 establishes a vital connection between the statistical reality of cyber threats and the specific contextual requirements of businesses aiming to safeguard their digital assets while upholding their core values. It establishes a foundation for a pragmatic yet insightful examination of cybersecurity through a biblically informed perspective, cultivating a distinctly strong framework for continuous risk mitigation and ethical governance.

The BFCy Model reconceptualizes regulations and protocols, not as bureaucratic obstacles, but as moral imperatives derived from biblical teachings, thereby highlighting the tangible repercussions of inadequate implementation. Businesses that follow this approach acknowledge that comprehending cutting-edge technology is beneficial, but that ethics and wisdom must guide its use to prevent misuse, exploitation, and harm. Thus, the BFCy Model addresses a critical gap in traditional cybersecurity discourse by integrating ethical considerations, collective accountability, and insights from the primary source of truth. It urges leaders to cultivate environments rich in transparency, ethical consciousness, and moral judgment in which security measures are not simply enforced but align with established principles and insights that significantly affect critical cybersecurity domains, including access controls, data utilization, risk tolerance, and organizational trust.

Organizations must integrate cybersecurity best practices to protect sensitive information and mitigate the risk of cyberattacks (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, 2023). Regular audits should be conducted to identify potential ethical and security weaknesses in computer systems. The audits must evaluate compliance with cybersecurity best practices and organizations’ religiously grounded ethical standards. Employing frameworks such as the Cybersecurity Framework 2.0 of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST CSF 2.0) (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2024) enables organizations to monitor and mitigate cybersecurity threats systematically. The BFCy Model demonstrates that accountability and auditability are essential for maintaining strong cybersecurity procedures. Leaders must cultivate an organizational culture that prioritizes responsibility and openness in cybersecurity, one that encompasses candid communication about security policies, incidents, and ethical challenges. Such actions foster trust among stakeholders and enhance an organization’s adherence to established norms and expectations.

In theological organizations, leaders can incorporate cybersecurity issues into theological education, thereby equipping future faith leaders to address the digital challenges that their communities will face (Alkhouri, 2024). Alkhouri (2024) urged leaders to create educational programs that integrate technical cybersecurity training with religious ethics and comprehend the potential effects of breaches from a scriptural viewpoint. Leaders should also promote the involvement of religious communities in cybersecurity knowledge and practices (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, 2023). Such engagement includes organizing workshops, talks, and collaborative initiatives to foster ethical digital conduct and shared accountability. Although it is assumed that individuals comprehend the expectations and are aware of appropriate conduct, it is essential to recognize that “knowing is not doing” (Burrell, 2018), for an employee may complete a security awareness assessment but fail to implement the acquired knowledge (Burton et al., 2023; Renaud & Dupuis, 2023; Triplett, 2022; Wightman & Shakhsheer, 2021).

Numerous factors likely contribute to this “action paradox.” According to reactance theory, introduced by Jack W. Brehm (1966), when individuals see a loss or imminent loss of their liberties, they are compelled to reclaim them (see also Wicklund, 2024). Consequently, individuals may oppose rules that impose constraints, particularly if they perceive that the rules limit their options or liberty. Cybersecurity researchers have highlighted this issue (Putri & Hovav, 2014; Renaud & Dupuis, 2023). From another perspective, various psychological characteristics, including dissatisfaction, hostility, control concerns, a mindset of disrespect for authority, and traits associated with antisocial and narcissistic personality types, may lead to dangerous behaviors (Moore et al., 2008; Noonan, 2018; Ohu & Jones, 2025a; Renaud & Dupuis, 2023). The member of an organization may experience elevated stress levels or workloads (D’Arcy et al., 2014; Nobles & Burrell, 2024) or feel apathy regarding an organization’s cybersecurity initiatives because of adverse prior experiences (Nobles, 2022).

6.3. Beyond Moral Exhortation

The BFCy Model encourages religious leaders to establish a comprehensive code of ethics that integrates principles such as honesty, stewardship, and justice into their organizations’ cybersecurity practices. As churches progressively transition services online and provide livestreamed worship, their digital presence extends significantly beyond the confines of the sanctuary (Kusuma et al., 2022). This transformation not only exposes church IT systems to cyber threats but also creates a distinct vulnerability at the intersection of church and congregant home networks, particularly through Internet of Things (IoT) devices (Kusuma et al., 2022).

More specifically, livestreaming services connect church equipment and networks with the varied and often less secure home environments of congregants. This process may create opportunities for cybercriminals to exploit vulnerabilities at either end of the connection (New Jersey Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Cell, n.d.). Securing digital interfaces is crucial to safeguard sensitive member information, maintain the integrity of worship experiences, and prevent technology-induced disruptions that could erode trust within faith communities (Kusuma et al., 2022; New Jersey Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Cell, n.d.). The expansion of IoT devices from smart cameras to home streaming systems underscores the need for proactive strategies that integrate scriptural principles of vigilance and prudent stewardship with contemporary risk management to protect the church community and individual congregants as they convene in hybrid digital environments.

The BFCy Model grounds cybersecurity in scriptural and ethical principles by emphasizing stewardship, integrity, vigilance, and justice. Center for Internet Security Critical Security Controls (CIS Controls) version 8 is a widely recognized, prioritized collection of best practices for cybersecurity designed to mitigate tangible threats across businesses of varying scales (Center for Internet Security, 2021). Table 3, a crosswalk table, correlates specific scriptural principles from the BFCy Model with relevant CIS Controls v8 (Center for Internet Security, 2021) and practices to demonstrate how biblical ethics underpin essential cybersecurity disciplines.

Table 3.

Cross-Mapping the BFCy Model with Relevant CIS Controls.

6.4. Cross-Mapping the BFCy Model

The systematic cross-mapping of the Biblically Framed Cybersecurity (BFCy) Model with leading technical standards and controls elucidates how scripturally informed practices resonate with contemporary cybersecurity requirements. This integrative analysis reveals substantive thematic and operational convergence between faith-based ethical imperatives and established frameworks. Such frameworks include the Center for Internet Security (CIS) Controls, the NIST CSF 2.0 (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2024), and ISO 27001:2022 (Adewole, 2024; International Organization for Standardization [ISO], 2022). Through this comparative lens, several key insights emerge:

- The CIS Controls v8 comprises 18 distinct, actionable domains, including Secure Configuration, Access Control, Data Protection, and Security Awareness Training. Each domain corresponds to the practical requirements addressed in technological frameworks and faith-based ethics.

- The BFCy Model interprets activities such as least privilege, perimeter defense, and quick response as contemporary manifestations of the biblical imperatives to safeguard, discern, and restore.

- The BFCy Model and CIS framework highlight the importance of not only technical controls but also the transformation of corporate culture, training, and leadership.

- Other cybersecurity-related standards, such as the NIST’s CSF and the International Organization for Standardization’s ISO 27001:2022—Information Security, Cybersecurity, and Privacy Protection–Information Security Management Systems–Requirements, align well with the BFCy Model.

While technical controls are essential, a Biblically Framed Cybersecurity (BFCy) approach must combine these safeguards with specific non-technical, ethical, and cultural initiatives. Neither technical nor human-centric measures are adequate in isolation. Aligning the scriptural and moral principles of the BFCy Model with cybersecurity controls can reveal significant collaboration. Faith-based principles not only validate but also actively strengthen the fundamental behaviors, governance, and controls outlined in generally accepted cybersecurity frameworks (Renaud & Dupuis, 2023). Researchers have argued that religious values such as stewardship, discipline, accountability, and communal oversight can effectively reinforce the behaviors, governance structures, and controls essential to established cybersecurity frameworks (Alkhouri, 2024; Renaud & Dupuis, 2023). From this perspective, faith-based ethics not only aligns with standards such as NIST CSF 2.0 (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2024) and ISO 27001:2022 (International Organization for Standardization [ISO], 2022) but can also inform various disciplines and essential cybersecurity practices (Renaud & Dupuis, 2023). This is a compelling and inspiring narrative for church communities seeking spiritual and digital fortitude.

6.5. Actionable Insights

Christian worship leaders can enhance their followers’ understanding of the critical importance of cybersecurity by drawing on biblical narratives, providing theological depth and practical information that fosters the development of cybersecurity skills. A crucial suggestion for worship leaders is to reconceptualize biblical accounts in terms of contemporary issues, aligning them with discernment and digital stewardship, for example, and likening the protection of digital borders to the safeguarding of the heart (Proverbs 4:23). To deepen congregations’ knowledge of cybersecurity, sermons may emphasize that, similar to the expectation for believers to remain vigilant in prayer and moral in behavior, they must also exercise prudence in their online activities and protect their digital communities. Enhancing security awareness and vigilance can further protect religious institutions, particularly those with an online presence, from cyber threats.

Members of the clergy may reference biblical narratives of deception, such as the serpent in the Garden of Eden (Genesis 3) and Judas’s betrayal (Matthew 26; Mark 14; Luke 22; John 18), to emphasize the importance of being vigilant against phishing, identity theft, and insider threats. They can enhance cybersecurity by encouraging congregants to exemplify moral clarity, honesty, and accountability in their online interactions. Worship leaders can subtly incorporate cybersecurity issues into prayer points, devotional readings, and multimedia representations that symbolize digital “gates,” “armor,” and “walls of protection” during theological and philosophical teachings about cybersecurity, thereby reinforcing the parallels with biblical narratives. This approach conveys knowledge by incorporating cybersecurity awareness into the spiritual growth of the religious community and establishing this awareness as a moral and pastoral responsibility.