Abstract

Western North Carolina (WNC), part of the Appalachian landscape, hosts a robust forest product industry but faces increasing challenges like land marginalization, warming temperatures and raw material shortages. This study evaluates the site suitability and cost-effectiveness of cultivating Populus species for high-value veneer–plywood (VP) production in WNC using the Veneer-Poplar Productivity and Economic Assessment Model (VP-PEAM). The model integrates site-specific variables (elevation, soil characteristics, landform and land-use history) to optimize site-species management strategies across diverse landscapes. Twelve scenarios are analyzed to assess how biophysical and land-use factors influence VP growth and profitability. The results show that VP productivity and profitability decline with increasing elevation, past land-use intensity, soil compaction and decreasing soil depth. All land-use types studied support profitable VP production. Yet, flood plain sites with medium-textured soils and moderate water table depths (0.61–1.83 m) offer optimal conditions. Even under suboptimal conditions, extended rotations maintain profitability, except on sites with persistent waterlogging or shallow water tables (<0.31 m). VPs generate higher annual equivalent opportunity benefits (USD 1568–USD 2763 ha−1 yr−1 in 15- to 18-year rotations) compared to non-forest land uses, suggesting their potential to enhance regional wood supply and land-use efficiency. These findings contribute to site-informed forest management and offer a modeling approach for assessing forest resilience and cost-effectiveness in Appalachian landscapes.

1. Introduction

Western North Carolina (WNC) is a high-elevation region (>854 m above mean sea level) in the Appalachian part of the US Southeast. WNC features a range of agricultural and forestry production systems [1] as well as abundant lands with great altitude variations, high slopes and poor soils, which have led to the abandonment of some land-use types [2]. WNC is a prominent Christmas-tree production region in the United States [3]. However, Christmas-tree producers may be forced to consider alternative crops as the industry faces several significant challenges, including competition from improved-quality artificial Christmas trees and expanding markets for them, as well as higher wholesale Christmas-tree productions [4]. Moreover, the production of Fraser fir, a popular Christmas-tree variety, is increasingly threatened by rising temperatures [3,5] and the spread of Phytophthora species pathogens [5,6]. WNC is also home to many wood-processing mills that produce high-value wood products (including veneer and plywood) and that procure hardwood timber, and some mills in the region use cottonwood (Populus) as raw material [7]. Growing interests in alternatives to procuring native yellow poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera) and other commonly used hardwoods could increase future Populus plantation productions in WNC (within the current buy area of the mills that use raw materials from cottonwood).

Poplars (genus Populus), particularly eastern cottonwood (P. deltoides) and hybrids with other species (e.g., black poplar, P. nigra; black cottonwood, P. trichocarpa; balsam poplar, P. balsamifera; and Japanese poplar, P. maximowiczii), are among the most important timber species globally [8]. Poplars are grown in both plantations and natural stands across temperate regions for wood and fiber products, with various growing areas and corresponding shares allocated to industrial roundwood production: India (0.32 million ha, 91%), Turkey (0.43 million ha, 49%), Europe (>0.65 million ha, 46%), China (9.19 million ha, 49%), the USA (9.33 million ha, 62%) and Canada (39.07 million ha, 2%) [8].

Poplar is commonly grown for lower-value wood products such as pulp and paper and bioenergy feedstocks [9,10], as well as high-value wood products. In Argentina, China and certain European countries, predominant markets include high-value solid wood products such as veneer, plywood, structural lumber and pallets [8,9,11] for which Populus is suitable, including cross-laminated timber [12], laminated veneer lumber, oriented strand board ([13] and references within), parallel strand lumber and other plywood forms [9].

Beyond its market versatility, poplar is an ideal plantation species due to its ease of propagation, fast growth, high response to management inputs [14] and adaptability to a wide range of environmental and silvicultural conditions [8,9,15,16], which aids in its global distribution. Significant efforts have also been made to select superior poplar genotypes. Interspecific hybridization, for example, is widely used [8,9] and produces crosses that often match superior local provenances, improving physiological and adaptational traits that can lead to increased poplar productivity [9,17]. Select poplar genotypes have demonstrated strength properties required for laminated veneer lumber production that are comparable with other frequently used species, including sliver fir (Abies alba) and European spruce (Picea abies) [18], as well as strength and stiffness nearly as desirable as those of Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) [11]. Veneer from poplars has a more uniform bond than dense hardwoods, which increases the desirability and value of poplar wood [11]. Additionally, treated poplar plywood has shown resistance to decay, enhancing the potential use of poplars for high-value outdoor furniture markets [19]. Owing to their suitability for high-value veneer products, poplars can generate high economic values, and the past few decades have seen an increased acreage of poplar plantations, specifically grown for high-value wood products [9,11].

There is no information on the economic viability of growing high-value poplars for wood product markets available in the region. In WNC, poplars can potentially make significant contributions to the supply chain of high-value timber if produced within reasonable distances from hardwood procuring and wood processors. This assertion is based on the recent commercial-grade suitability testing of poplars (conducted in 2020 and 2022 by Columbia Forest Products, Old Fort in WNC), which found many poplar genotypes suitable for veneer and plywood production [20].

Landowners, wood mills and other forestry stakeholders need reliable information to address whether veneer poplars (VPs) have significant timber productivity potential in WNC and can be produced cost-effectively. Previous studies have examined variations in poplar productivity and species adaptability across different physiographic regions and land types, identifying fast-growing genotypes in the region [15,21,22] that can reach harvest dimensions at significantly shorter rotations compared to other tree species. Other studies have reported the economic assessment results of poplars and other short-rotation woody crops (SRWCs) for bioenergy purposes in several regions of North Carolina and the USA [2,22,23]. Although these studies showed that the economic return from bioenergy production systems were not profitable, they did not address the cost-effectiveness of VP production in WNC.

A robust approach is needed for evaluating VP productivity potential in the region, considering site–land parameters unique to WNC, which is characterized by high altitudes, great variations in landforms and soil properties and various land-use types. Because conducting field studies to assess all possible site–land and stand parameters on VP growth and profitability is impractical, decision-support models can be valuable for bridging these knowledge gaps and facilitating the decision-making process for growing and managing poplars in the absence of production and profitability data [16]. For instance, an SRWC productivity and economic assessment model (SRWC-PEAM) was previously developed and validated for bioenergy production in the Southeastern USA, including poplars. However, it did not account for elevation effects on poplar productivity, critical in the high-elevation WNC region. Stand density, a crucial silvicultural consideration affecting resource availability, tree growth and wood quality [24], was also not fully integrated into SRWC-PEAM to assess tradeoffs between stem growth and stand density, crucial for veneer stands since the stands prioritize stem diameter growth and quality. Previous studies have used decision-support tools to assess the economic viability of poplars and willow (Salix spp.) [25,26,27,28]. However, the results from these studies are not directly applicable to VP production in WNC due to regional, species, growing condition and stand objective differences.

This study evaluated the cost-effectiveness of VP production in WNC, given the existing veneer and plywood market potential in the region, by assessing the productivity and economic potential of VP using a modified and refined version of SRWC-PEAM [16], termed VP-PEAM (Veneer-Poplar Productivity and Economic Assessment Model). SRWC-PEAM was chosen for adaptation due to its established utility as a tool for assessing poplar productivity and profitability in the Southeastern USA. Given the adaptability of poplars and the suitability of several poplar genotypes for veneer and plywood production, this study hypothesized that poplar cultivation could offer significant economic opportunities in WNC within relatively short rotations compared to other forest species. This evaluation included opportunity cost comparisons of VP versus other common land uses in WNC, which provided important insights into potential alternative production systems for utilizing marginal lands in WNC and assessing the investment risks associated with potential land-use changes to VP plantations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. A Summary of SRWC-PEAM

SRWC-PEAM is a decision-support model developed to evaluate the effects of land types, site preparation and stand management strategies, rotation length and delivered feedstock prices on the productivity and cost-effectiveness of selected fast-growing forest species (SRWCs) in the Southeastern USA [15,21]. The model comprises three main modules: site suitability and productivity assessment, site preparation and stand management strategies and financial analysis (including itemized budgets and cost-effectiveness evaluations).

The model assesses the suitability of SRWC species such as poplars, American sycamore (Platanus occidentalis) and sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua) based on user-selected site–soil attributes. The model rates the extent of site–species suitability using a parameter called Site Quality Rating (SQR), which ranges from 0 (unsuitable) to 1 (unrestricted suitability), with values in-between indicating varying degrees of suitability adjustments due to user-selected site–soil properties. SQR serves as the initial step in assessing species–site suitability and helps identify the most suitable SRWC species for specific land attributes. Besides SQR, the model incorporates the mean annual increment (MAI) in wood biomass (Mg ha−1) for selected species. The MAI multiplied by SQR provides an estimation of stand wood biomass productivity. This approach allows users to comprehensively evaluate the suitability of SRWCs for a site, as a site may have a higher SQR for one SRWC species but a lower MAI compared to another SRWC with a lower SQR but higher wood productivity.

SRWC-PEAM allows users to choose from various current land-use types and applies optimal site preparation and stand management strategies based on the selection. It generates itemized year-by-year cost projections for site preparation and intensive stand management during the initial three years of SRWC growth. Once SRWC stands achieve canopy closure after three years, weed growth decreases significantly, minimizing wood control expenses, the costliest phase of stand management. The model evaluates the economic performance of SRWCs using parameters including wood biomass productivity, delivered green biomass prices and detailed stand costs. SRWC-PEAM accommodates stands ranging from low- to high-density, which may not require pruning or thinning and are harvested between 3 and 20 years for applications in bioenergy or pulpwood. Outputs from the model include SQR, wood biomass estimates, year-by-year stand budgets and cost-effectiveness metrics for selected site–soil conditions, species and management practices. The productivity outputs of SRWC-PEAM have been validated against field data [15]. SRWC-PEAM was developed to balance the inclusion of detailed site–soil–stand characteristics necessary for comprehensive productivity and profitability assessments while ensuring practicality and user-friendliness for various stakeholders such as landowners, researchers and extension agents exploring profitable species and management options.

2.2. Description of VP-PEAM

SRWC-PEAM serves as a valuable tool for assessing the productivity and profitability of SRWCs under generalized conditions. However, the model lacks refinement to assess how wood biomass productivity is influenced by site elevation or stand density. The model’s stand management submodule also does not incorporate silvicultural treatments that enhance wood form or quality. Elevation effects are particularly significant in accurately estimating productivity and cost-effectiveness in high-altitude regions like WNC, which features mountainous physiography with diverse elevations and microsites. A robust approach is essential to account for density effects on VP productivity and stem diameter growth, crucial for producing veneer-suitable logs.

This study modified SRWC-PEAM to include capabilities for assessing the effects of elevation and stand density on VP productivity and profitability. These modifications enable VP-PEAM (Veneer-Poplar Productivity and Economic Assessment Model) to estimate veneer log volume and stem size (scaling diameter), stand profitability and annual budgets in WNC. The adaptation of SRWC-PEAM into VP-PEAM involved developing assessment indices for elevation and stand density effects. These indices were used to adjust SQR values, which assess the compatibility between site–soil attributes and SRWC species. This enhancement ensures that VP-PEAM provides more accurate and specific assessments associated with the unique conditions of WNC. The following approaches were used to develop the indices for elevation and stand density.

2.2.1. Site Elevation

The elevation index in VP-PEAM was derived from the empirical relationship regarding aboveground net primary production across 16 broad-leaved deciduous forest stands in the southern Appalachian Mountains, which remained relatively undisturbed for over 70 years [29]. For this study, it was assumed that stand productivity decreases as elevation increases above 839 m above mean sea level (a.m.s.l.), based on the findings from Bolstad et al. [29]. Accordingly, an elevation index of one is assigned to stands growing below 839 m elevation, indicating no reduction in stand productivity due to elevation. In VP-PEAM, the elevation index is calculated as (Equation (1))

where elevation (user-provided) is in meters, and 10.36 (Mg ha−1 yr−1) represents the maximum net primary production value [29].

2.2.2. Stand Density

VP-PEAM includes a stand density index derived from an empirical relationship developed specifically for eastern cottonwood (Populus deltoides) [30]. This index evaluates the effect of stand density on productivity relative to a reference density of 374 trees ha−1, which was identified as the density that produced the highest growth in the study by Krinard and Johnson [30]. The density index in VP-PEAM is calculated as follows (Equation (2)):

where stand density is in trees ha−1, and stand age (or rotation length) is in years.

2.2.3. Site Quality Rating (SQR, VP-PEAM)

In VP-PEAM, SQR for growing VPs under specific site and stand conditions (SQRV) is calculated using Equation (3). The equation integrates elevation and stand density considerations into the assessment of site quality for VP production, offering a refined approach to evaluating the suitability of sites for growing veneer poplars. That is,

where SQR represents the cumulative contributions of site attributes to poplar growth as determined by SRWC-PEAM [16]; elevation index adjusts for the impact of elevation on productivity, derived from empirical data; and density index evaluates the effect of stand density relative to a standard density of 374 trees ha−1.

SQRV = SQR × Elevation Index × Density Index

2.2.4. Additional VP-PEAM Considerations

VP-PEAM incorporates the following assumptions and enhancements to broaden its capabilities for assessing veneer log production in WNC under varying site and management conditions:

- VP-PEAM assumes the selection of site-suitable poplar genotypes for veneer poplar (VP) production.

- The model estimates total stand stem biomass and calculates stand total veneer log biomass, assuming that it constitutes 50% of the total stem biomass.

- It is assumed that 75% of standing VP trees produce veneer logs, each 2.75 m long, when their scaling diameter (SD, which refers to the inside-bark or under-bark stem diameter) reaches at least 21.6 cm; trees with SDs smaller than 21.6 cm are not ready for harvest.

- Stand total veneer log biomass is converted into volume using the mean poplar wood density of 492 kg m−3. The per-tree volume of veneer logs is estimated based on a truncated cone formula (Equations (4) and (5)), assuming logs are truncated cones with a length of 2.75 m and basal diameters 1.187 times SD.

- No interactions between elevation and stand density effects on productivity were considered.

- The cost-effectiveness of VP production is evaluated using net present value (NPV, $ ha−1) and assuming the veneer log delivered price of USD 190 m−3 of wood (log).

- VP-PEAM includes opportunity benefit (gain) comparisons between VP production and commonly grown crops in WNC such as corn, wheat, tobacco and small-grain hay. Expected annual VP revenues are expressed as equivalent annual values (EAVs, $ ha−1 yr−1) and compared with revenues from alternative crops using data from the 2024 Crop Comparison Tool [31].

2.3. Assessment of VP Productivity and Profitability in WNC

VP-PEAM was used to analyze 12 scenarios encompassing site–land attributes and stand management to determine conditions conducive to cost-effective VP production in WNC. The scenarios included site elevation (Case 1), stand density (Case 2), previous land-use type and intensity (Cases 3 and 4), soil depth (Case 5), soil texture (Case 6), root-zone (RZ) structure (Case 7), soil compaction (Case 8), presence/type of soil pan (Case 9), water table depth (WTD, Case 10), site topography (Case 11) and microsite characteristics (Case 12). Table 1 details these site–land–stand configurations used to assess VP productivity and profitability across scenarios relevant to WNC. Each scenario evaluated VP profitability using at least two rotation lengths, facilitating the identification of optimal rotations under specific site–stand conditions and enabling a comparison of additional growth years’ effects on profitability. Stands were deemed ready for veneer harvest when SD reached at least 21.6 cm; scenarios with smaller SDs were assessed with longer rotations. This study focused exclusively on the profitability of veneer production (excluded non-veneer wood biomass economic values from VPs).

Table 1.

Scenarios of site–land–stand variables used to assess the effects of elevation, stand density, land-use type, past use intensity, soil properties, water table depth (WTD) and landforms on veneer poplar productivity (stem biomass and scaling diameter) and cost-effectiveness in WNC.

All site and land conditions considered were relevant to WNC and VP production. This study and VP-PEAM encompassed various WNC land-use types, with cost-effectiveness assessments of VP production potentially influencing conversions from current land uses. Elevation effects were evaluated across the range of 854–1373 m a.m.s.l. Stand density effects were examined (in Case 2) using spacing options applicable to VP production. This study focused on within-case evaluations (e.g., Case 5 compared different soil depths at the same stand density). VP-suitable stand density values were selected to illustrate density effects on VP productivity. Yet, variations in stand density across cases (e.g., 1864 trees ha−1 in Case 1 vs. 1658 trees ha−1 in Case 3) were irrelevant to the outcomes of the target within-case evaluations.

All cases assumed 5% mortality. Cases 3–12 used an elevation of 915 m and a stand density of 1658 trees ha−1. Variations in stand density across cases do not affect within-case evaluations that were the study focus.

3. Results

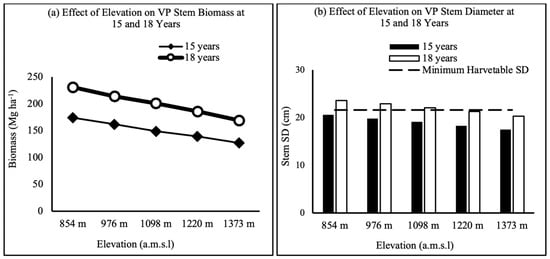

Site elevation affected VP productivity and profitability (Figure 1a, Table 2). As elevation increased, VP productivity and NPVs decreased. VP stands would need longer rotation to reach scaling diameter (SD) for veneer logs (21.6 cm, Figure 1b). In Case 1, for example, an elevation increase from 976 m to 1220 m would extend the VP rotation length by at least one year while reducing NPV at harvest by USD 1957 ha−1. Yet, smaller elevation changes, e.g., between 1098 m and 1220 m, would have similar NPV values at rotations suitable for harvest for veneer (18 years and 19 years, respectively). The results (Case 1, Table 2) focused on rotations required for stands to reach SD of 21.6 cm, yet further extending the rotation would increase economic returns.

Figure 1.

(a) shows the effect of elevation on veneer poplar (VP) stem biomass at 15 and 18 years and biomass (Mg ha−1) decreasing with increasing elevation. (b) shows the effect of elevation on VP stem scaling diameter (SD) at stand ages of 15 and 18 years and that SD decreases with elevation. The dashed line indicates the minimum harvestable diameter threshold (SD of 21.6 cm) and shows that elevation has a modest effect on meeting size requirements.

Table 2.

The results of the assessments of the effects of site elevation and stand density (Cases 1–2) on the economic returns (NPV) of veneer poplar production in WNC.

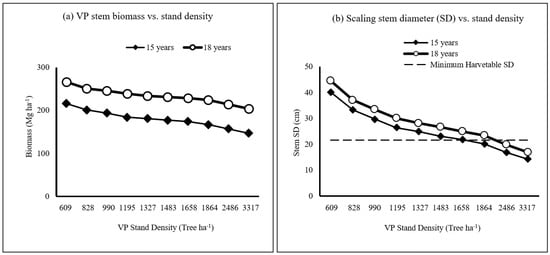

Stand density affected VP productivity and profitability (Figure 2a, Table 2). Higher density would lead to slower stem growth and longer rotations to reach harvest size (SD ≥ 21.6 cm, Figure 1b), which could be up to 60% longer. For example, Case 2 stands could reach an SD of 21.6 cm or larger in 15 years if stand density is 1658 or 1409 trees ha−1 but would require up to 24 years at a stand density of 3317 trees ha−1. The VP-PEAM results also showed that NPV values would also be higher for harvest-ready stands with a decrease in density.

Figure 2.

(a) shows effect of stand density on veneer poplar (VP) stem biomass at 15 and 18 years, showing biomass (Mg ha−1) decrease with increasing stand density. Older stands (18 years) have higher biomass across all densities compared to 15-year-old stands, indicating benefit of extended rotations for total biomass. (b) shows effect of stand density on VP scaling diameter (SD) at 15 and 18 years and stem diameter decrease with increasing stand density. Dashed line indicates minimum harvestable diameter threshold (SD of 21.6 cm), showing that higher-density stands take longer to reach this limit, which emphasizes importance of density management for veneer log production.

Land-use types would influence the profitability of VP production in WNC (Case 3, Table 3). Across all the land-use types studied (cropped/tilled, fallow with herbaceous or woody species, old-site fields, pasture, pasture with tree incompatibility and timber harvesting trails), NPV varied only slightly. For 15-year rotations, NPV ranged from USD 23,055 to USD 24,293 ha−1, while for 18-year rotations, the NPV range was USD 31,046 to USD 32,163 ha−1. These results indicate that VP plantations can be cost-effective on diverse marginal lands. The results also showed that any of the land-use types considered at a site with similar site–land features (as in Case 3) could be used for profitable VP production in a 15-year rotation, although longer rotation would lead to higher NPVs. VP-PEAM uses land-use types to estimate annual stand costs for establishing and managing VP stands. The choice of land-use types affects cost-effectiveness by affecting expenses, not productivity or revenues from biomass sales. Moreover, the intensity of the past use of land also affected VP productivity and profitability (Table 3). A higher intensity of previous land use reduced VP productivity and profitability. In cases where land was previously intensely used for more than 10 years or is currently open and bare, VP production would require longer rotations to reach the harvestable stage. For example, the Case 4 results showed that VP production on undisturbed lands would be 20% more profitable compared to previously intensively managed lands, for the same rotation length (18 years required to reach SD ≥ 21.6 cm).

Table 3.

The results of the assessments of the effects of land types and previous use (Cases 3–4), soil properties (Cases 5–9), water table depth (WTD, Case 10) and topographic position and microsite (Cases 11–12) on the stem wood biomass productivity, scaling diameter (SD) growth and economic returns (NPV) of veneer poplar production in WNC.

Soil properties affected VP productivity and profitability (Table 3). In Case 5, for instance, stem growth and NPV increased with greater soil depth, with up to a 24% (four-year) difference in rotation (to reach SD ≥ 21.6 cm) between shallow and deep soils. Soil texture and RZ structure also influenced VP profitability and the rotation lengths to reach the harvest stage for veneers. VP productivity and profitability were the highest in medium-textured soils and the lowest in fine (clayey) soils (Case 6). Under the site–stand conditions of Case 6, VPs could be harvestable (reach SD = 21.6 cm) in 15 years in medium-textured soils and in 18 years in course- or fine-textured soils. The results regarding the effects of RZ soil structures (granular, prismatic/blocky and massive/platy; Case 7) showed that VP was the least productive and least profitable in soils with massive/platy structure, requiring longer rotations (up to 3 years) to reach an SD of 21.6 cm. Despite the influence of soil properties on VP profitability, VPs could be produced cost-effectively across all soil conditions discussed by adjusting rotation lengths according to site–stand conditions. VP production and profitability were also affected by the presence of growth-limiting soil conditions including soil compaction and pan (Table 3). The current results (Cases 8 and 9) revealed that over 18 years, VP production would be more profitable on soils with no compaction than soils with moderate (by 3.5%) or strong compaction (by 15.3%). Similarly, VP would be more profitable on soil without a pan than soils with a plow pan (by 3.5%) or inherent pan (by 19.3%).

VP production was cost-effective across most WT depth options, as well as all topography and microsite scenarios of this study (Cases 10–12, Table 3). However, VP productivity and profitability differed based on WT depth (Case 10), topographic positions (Case 11) and microsites (Case 12). VP production was optimal on sites with a WT 0.61 to 1.83 m deep followed by sites where WT depth was 0.31 to 0.61 m or 2.14 to 3.05 m (Table 3). In contrast, VP profitability was lower on sites with a deep WT (>3.05 m), and VP production would be unfeasible on sites with a very shallow WT (<0.31 m) or sites that are flooded or waterlogged yearlong. Site topography affected VP profitability (Case 11). VPs were the most profitable on flood plains and lower on higher topographic positions (Table 3). VP was more profitable in depressions and flat microsites than ridges.

Opportunity benefit analyses showed that VP equivalent annual revenues (EAV) considerably exceeded expected revenues from the other production systems in WNC, including corn, wheat, tobacco and small-grain hay (Table 4). VP production cases (Cases 1–12) were grouped (e.g., Cases 1–2, Cases 3–4, Table 3) based on similarities in selected site–stand attributes (Table 1). Depending on site–land conditions, the average VP opportunity benefits would be USD 1568 ha−1 yr−1 to USD 2264 ha−1 yr−1 in 15-year rotations and USD 1995 ha−1 yr−1 to USD 2763 ha−1 yr−1 in 18-year rotations. Variations in site–stand attributes across case groups (in this study) demonstrate VP-PEAM’s robustness in assessing diverse conditions typical of areas considered for VP production and the alternative production systems mentioned above.

Table 4.

An assessment of the opportunity benefits of VP production (under Case 12) vs. other production systems (corn, wheat, tobacco and small-grain hay) that are common in WNC.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that VP-PEAM can assess the economic potential of VP stands and is valuable for identifying site–land–stand conditions specific to VP production and to WNC, rather than relying on generalized productivity and profitability estimations. These capabilities make VP-PEAM a robust and versatile decision-making tool for several stakeholders including WNC mills, forestry consultants and extension agents and forest landowners (and growers). VP-PEAM evaluates stand profitability based on poplar productivity responses to the various site–soil–stand variables included in the model. Hence, it is important to gain insights into how these variables affect poplars as such insights can facilitate the application and interpretation of the model’s results. To ensure reliability, the productivity projections presented in this study should be complemented by (validated through) field evaluation.

The current study found that stand density affected tree productivity and stem growth inversely, consistent with previous poplar findings. Jiang et al. [24] found that stand density significantly impacted radial growth (positively) and stem taper (inversely) but not wood density. This study also correlated stand density and wood mechanical properties. A long-term study also observed significant stand density effects on poplar stem size and biomass partitioning, including an increased proportion of stem wood biomass relative to total aboveground wood and enhancing total root growth [32]. These results emphasize the importance of integrating stand density decisions with other management considerations, such as expecting greater pruning in lower-density stands and addressing lower nutrient availability in higher-density stands, especially under conditions of low fertility.

VP-PEAM includes land-use types to estimate year-by-year costs necessary for the optimal establishment and management of VP stands. The selections affected the cost-effectiveness of stands by affecting expenses but not stand productivity or revenues. Poplars have mainly been grown on marginal, former agricultural lands [33,34] and have demonstrated adaptability to various poor-quality lands. Yet, poplar productivity is considerably affected by soil quality [16,22]. Intensive land use deteriorates soil structure and fertility [35], and the current study stressed the importance of past land-use intensity as a proxy to reflect soil quality deterioration that impacts VP productivity.

Soil texture plays a critical role in the productivity of poplars, which ideally favor soils with medium texture and good drainage [36] over heavier soils [37]. However, other studies have reported mixed results on the effects of soil texture on poplar establishment and early growth. Johansson and Karačić [38] found that poplars have slower early growth on heavier soils, although they can end up with high productivity. In contrast, Böhlenius et al. [39] reported that soil texture did not affect poplar establishment on agricultural sites, although it affected root growth, with more roots produced under sandy conditions. Salehi et al. [40] also observed significant productivity differences between poplar stands with different textures. These studies corroborated the current results on how textual differences affect VP productivity; VP would show the highest growth on medium-textured soils and the lowest growth on heavier texture. A previous study found decreased root growth in hybrid eastern cottonwood (a cross between Eastern cottonwood, Populus deltoides, and European black poplar, Populus nigra), with increasing soil bulk density. The suggested increased bulk density inhibits root growth and resource access, potentially affecting early poplar survival, especially under water-limited conditions [41]. This insight helps explain the current study results on the negative effects of heavier textures, increased soil compaction and soil pan presence on VP productivity. Soil drainage also affects the productivity of poplars, which prefers good drainage [36]. This preference (for good drainage) may explain the lower VP productivity associated with increased compaction, the presence of soil pan and heavier soils, all of which inhibit soil moisture movement.

The current study agreed with previous research on the effects of WT on poplar productivity. Mahoney and Rood [42] observed decreased poplar growth in riparian zones with a lower WT. Imada et al. [43] observed that WT depth affected the root growth of young P. alba trees, with fine roots mainly concentrated right above the water table. Their study also observed high concentration of fine roots right below the soil surface, which somewhat aligned with McIvor et al.’s [41] findings that the root biomass of young poplars was concentrated in the top 0.5 m of the soil where bulk density was lower and regardless of soil type (three studied). These results from young poplar studies suggest that poplar growth may be affected more by WT depth and soil bulk density than by soil depth beyond a minimum depth. However, given that VPs would be grown in rotations of up to 20 years, soil depth can be expected to have a considerably greater effect on poplar productivity.

VP-PEAM includes an approach for assessing elevation effects on poplar productivity based on Bolstad’s [29] findings on productivity decreases in 16 broad-leaved deciduous species with increasing elevation. The current results showed that VP biomass and stem growth decreased with increased elevations, agreeing with Coomes and Allen [44] who observed that trees experienced lower growth and reduced canopies at high elevations. Bolstad et al. [29] also found that landforms affected the productivity of hardwood species in the southern Appalachians, with greater productivity on ridges than depressions. However, although the landform–productivity correlation in their study was not particularly strong (R2 = 0.33), the study results contrasted with the current results, which found greater poplar growth on depressions than ridges. The current results on microsite effects agreed with a study by Wang et al. [45] that linked differences in microsites to considerable variations in tree growth, soil physical properties and the relationships between soil water and physical properties. Pinno et al. [46] studied microsite textural differences and their effects on poplar growth, observing an “optimal range” of sand content for a poplar genotype. Their study also found greater poplar growth in microsites with less extreme sand or clay contents; particularly, poplar growth was greater in coarse-textured microsites with higher clay content (better soil water-holding capacity of clay) and in heavier-textured microsites with higher sand content (better soil porosity).

Depending on genotype, some poplars (anisotropic) respond to water stress by avoiding drought (e.g., reducing leaf area by shedding leaves), while other genotypes (isotropic) perform morphological adjustments (e.g., chemical adjustments) that allow them to carry out biological functions [47]. These approaches have significant implications for how poplars respond to their topographic positions. A previous study reported that anisotropic poplars prefer higher topographic positions due to greater soil water variability in these positions, while isotropic poplars are expected to grow better in lower topographic positions, which maintain consistent soil water content for longer [48]. While the current study did not include the effects of water strategies, it agreed with the above-mentioned studies in that topographic position affected poplar productivity.

Many landowners may prefer to avoid or minimize production risks and view the long-term nature of forest productions, even considerably shorter-rotation types like VPs, as higher-risk systems that also tie up funds for extended periods due to their multi-year revenue generation cycle. These landowners may require substantially greater annual equivalent revenues from productions like VPs to consider them over annual production systems. The current study observed great opportunity benefits of VP production over the other production systems in this study, which may encourage some growers to consider VP production.

The VP stand budgets developed by VP-PEAM provide more production information that producers can use to compare VP production activities and costs against published crop enterprise budgets for in-depth financial comparisons and assessments. The opportunity benefit assessments of this study (Table 3) have important implications for addressing the potential roles of poplars as alternative production systems in WNC, especially on Fraser fir Christmas-tree (Abies fraseri) production lands as Fraser fir production faces growing production challenges [2,3,4,5,6]. VP can be profitable in WNC, where there is a market for high-value forest products (veneer and plywood), and this could serve as a preferred alternative crop on former Fraser fir Christmas-tree lands now classified as Phytophthora-infected marginal sites. This potential stems from poplar’s tolerance to Phytophthora pathogens. Recent findings indicate that poplars, particularly T × D hybrid genotypes, showed strong tolerance to Phytophthora cinnamomi, the most common species in WNC and the primary pathogenic threat to Fraser fir production in the region [49]. Given poplars’ adaptability to grow on various marginal land types, growing conditions and physiographic regions [15], there is a great promise in growing stands of site-suitable poplar genotypes for veneer and plywood on under-used to fallow lands. This approach may also be considered for converting less profitable production systems to VP production. Additionally, landowners could gain added economic benefits from carbon credits by converting on previously non-forested sites or marginalized lands to VP production.

For optimal productivity outcomes, poplar genotypes should be matched with site conditions [15,21,32], and this is applicable to VP production in WNC. However, confounding site and stand factors complicate the broad implementation of available information on clonal performance to different sites [50]. Significant efforts have gone into advanced poplar selection through interspecies and intraspecies hybridization [9,17] and applying insights into poplar’s genotype–environment interaction [50,51,52,53] and knowledge on the broad phenotypic plasticity [52]. Moreover, poplar genotypes vary in their wood properties that affect wood products [18,24]. These are important factors to consider when applying VP feasibility assessments from the current study, which assumes the selection of site-suitable genotypes.

5. Conclusions

Poplars have significant potential to strengthen the supply chain in WNC, a key part of the greater Appalachian region. This study demonstrated that veneer poplars (VPs) offer strong productivity and profitability in WNC. They can be grown on substantially shorter rotations than other forest species and within reasonable distances of hardwood procurement and wood-processing mills in the region. The current results indicate that optimal VP growth and economic returns occur at lower elevations and topographic positions, at moderate stand densities and on deep, medium-textured, well-structured soils with moderate water table depth and a minimal history of intensive land use. The key findings include the following:

- Elevation effects: Higher elevation reduced the productivity and profitability of VP stands. However, small elevation differences resulted in similar NPVs at harvestable rotations (18–19 years), which suggests diminishing economic returns beyond certain elevation thresholds.

- Stand density effects: Higher densities slow stem growth, requiring longer rotations (up to 60%) to reach harvest size (SD ≥ 21.6 cm). Cost-effectiveness increased as stand density decreased, which indicates that wider spacing improves economic returns and growth efficiency.

- Land types and use history: All land-use types considered can support profitable VP production by adjusting rotation length. Sites with less intensive past land use or undisturbed conditions were up to ~20% more profitable than previously intensively used lands.

- Site factors: Soil depth, texture and structure significantly affected VP productivity and economic returns. Deep soils and medium textures yielded higher biomass and NPVs, whereas strongly compacted soils reduced productivity and NPV by up to ~15%. Soil pans lowered profitability by up to ~19%, and shallow water tables negatively affected growth. Lower slopes and stream terraces outperformed upland sites in biomass production and cost-effectiveness. Depressions and concave microsites yielded better growth compared to ridges.

- Opportunity gain: VP production could be substantially more cost-effective than several annually harvested systems (corn, wheat, tobacco, hay) common across WNC and the broader Appalachian landscapes (opportunity benefits: USD 1568–USD 2763 ha−1 yr−1 in 15- to 18-year rotations). This makes VPs a strong alternative for land-use planning in WNC.

Although this study shows that VP production can be productive and profitable across diverse site conditions typical or relevant in WNC, site selection and management strategies, including rotation length and density adjustments, are crucial for maximizing veneer log production and economic returns. The information generated in this study should be integrated with existing data on fast-growing, highly productive poplars for the region. The current results and the VP-PEAM model could help identify site–land–stand conditions and opportunities for profitable commercial-scale VP production. Such operations could lead to economies of scale, lowering production costs and increasing profitability, especially since poplar establishment and early management are highly cost-intensive.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B. (Solomon Beyene); Methodology, S.B. (Solomon Beyene) and S.B. (Sam Blumenfeld); Formal Analysis and Investigation, S.B. (Solomon Beyene) and S.B. (Sam Blumenfeld); Validation, S.B. (Solomon Beyene); Writing—Original Draft, S.B. (Solomon Beyene) and S.B. (Sam Blumenfeld); Writing—Review and Editing, S.B. (Solomon Beyene), S.B. (Sam Blumenfeld), and E.G.N.; Supervision, S.B. (Solomon Beyene); Funding Acquisition, S.B. (Solomon Beyene) and E.G.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the (Grant number: 2022-0106). United States Department of Agriculture—National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Agriculture and Food Research Initiative (USDA NIFA) Grant Number: 2022-68016-36232.

Data Availability Statement

The model used in this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request due to technical and time limitations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dennis Hazel for his review during the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest or competing financial or non-financial interests related to the work presented in this manuscript.

References

- USDA. National Agricultural Statistics Service—NASS. Census of Agriculture. 2022. Available online: https://www.nass.usda.gov/AgCensus (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Ghezehei, S.B.; Nichols, E.G.; Hazel, D.W. Early clonal survival and growth of poplars grown on North Carolina Piedmont and Mountain marginal lands. BioEnergy Res. 2015, 9, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agricultural Marketing Resource Center. Christmas Trees. 2024. Available online: https://www.agmrc.org/commodities-products/forestry/christmas-trees (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Pettersson, M.; Frampton, J.; Sidebottom, J. Influence of Phytophthora root rot on planting trends of Fraser Fir Christmas trees in the Southern Appalachian Mountains. Tree Plant Notes 2017, 60, 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel, K.E.; Easterling, D.R.; Ballinger, A.; Bililign, S.; Champion, S.M.; Corbett, D.R.; Dello, K.D.; Dissen, J.; Lackmann, G.M.; Luettich, R.A., Jr.; et al. North Carolina Climate Science Report; North Carolina Institute for Climate Studies: Asheville, NC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://ncics.org/nccsr (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- North Carolina Christmas Tree Association. Fraser Fir Trees. 2021. Available online: https://ncchristmastrees.com/fraser-fir-trees/ (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- North Carolina Forest Service. Buyers of Timber Products in North Carolina. 2023. Available online: https://www.ncforestservice.gov/Managing_your_forest/timber_buyers.htm (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- International Poplar Commission (IPC). Synthesis of country progress reports. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth Session of the International Commission on Poplars and Other Fast-Growing Trees Sustaining People and the Environment, Rome, Italy, 5–8 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Isebrands, J.G.; Aronsson, P.; Ceulemans, M.C.; Coleman, M.; Dimitriou, N.D.; Doty, S.; Gardiner, E.; Heinsoo, K.; Johnson, J.D.; Koo, Y.B.; et al. Environmental applications of poplars and willows. In Poplars and Willows: Trees for Society and the Environment; Isebrands, J.G., Richardson, J., Eds.; CABI: Oxford, UK; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014; pp. 258–336. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Energy. Billion-Ton Report: Advancing Domestic Resources for a Thriving Bioeconomy; Oak Ridge National Laboratory: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2016. Volume 1. Available online: http://energy.gov/eere/bioenergy/2016-billion-ton-report (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Balatinecz, J.J.; Kretschmann, D.E.; Leclercq, A. Achievements in the utilization of poplar wood—Guideposts for the future. For. Chron. 2001, 77, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hematabadi, H.; Madhoushi, M.; Khazaeian, A.; Ebrahimi, G. Structural performance of hybrid poplar-beech cross-laminated timber (CLT). J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 102959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudson, R.; Brunette, G. Evaluation of Canadian prairie-grown hybrid poplar for high-value solid wood products. For. Chron. 2015, 91, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.P. Ecophysiology of short rotation forest crops. Biomass Bioenergy 1992, 2, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghezehei, S.B.; Nichols, E.G.; Maier, C.A.; Hazel, D.W. Adaptability of Populus to physiography and growing conditions in the Southeastern USA. Forests 2019, 10, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghezehei, S.B.; Nichols, E.G.; Hazel, D.W. Productivity and cost-effectiveness of short-rotation hardwoods on various land types in the southeastern USA. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2019, 22, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, R.E., Jr.; Stettler, R.F.; Bradshaw, H.D., Jr. The genecology of Populus. In Biology of Populus and Its Implications for Management and Conservation, 3rd ed.; Stettler, R.F., Bradshaw, H.D., Jr., Heilman, P.E., Hinckley, T.M., Eds.; NRC Research Press: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1996; pp. 33–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kurt, R. Suitability of three hybrid poplar clones for laminated veneer lumber manufacturing using melamine urea formaldehyde adhesive. BioResources 2010, 5, 1868–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcon, B.; Viguier, J.; Candelier, K.; Thevenon, M.F.; Butaud, J.C.; Pignolet, L.; Gartili, A.; Denaud, L.; Collet, R. Heat treatment of poplar plywood: Modifications in physical, mechanical, and durability properties. iForest 2023, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghezehei, S.; Hazel, D.; (Department of Forestry & Environmental Resources, College of Natural Resources, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695, USA). Intercropping Populus for Bioenergy and Veneer. Final Report to the Bioenergy Research Initiative Grant Program, North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. Unpublished report. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ghezehei, S.B.; Wright, J.; Zalesny, R.S., Jr.; Nichols, E.G.; Hazel, D.W. Matching site-suitable poplars to rotation length for optimized productivity. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 45, 117670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghezehei, S.B.; Ewald, A.L.; Hazel, D.W.; Zalesny, R.S., Jr.; Nichols, E.G. Productivity and profitability of poplars on fertile and marginal sandy soils under different density and fertilization treatments. Forests 2021, 12, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanturf, J.A.; Young, T.M.; Perdue, J.H.; Dougherty, D.; Pigott, M.; Guo, Z.; Huang, X. Potential profitability zones for Populus spp. biomass plantings in the Eastern United States. For. Sci. 2017, 63, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.Z.H.; Wang, X.Q.; Fei, B.H.; Ren, H.Q. Effect of stand and tree attributes on growth and wood quality characteristics from a spacing trial with Populus. Ann. For. Sci. 2007, 64, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, T.; Volk, T.A. Improving the profitability of willow crops—Identifying opportunities with a Crop Budget Model. BioEnergy Res. 2011, 4, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, W. Energy Crop Production Costs and Breakeven Prices Under Minnesota Conditions; Department of Applied Economics Staff Papers, No. 2008-18 (or Staff Paper P08-18); University of Minnesota, University of Minnesota: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, W.; Headlee, W.L.; Zalesny, R.S. Impacts of supply-shed-level differences in productivity and land costs on the economics of hybrid poplar production in Minnesota. BioEnergy Res. 2015, 8, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, W.F.; Nelson, N.; Jackson, J.; Berguson, B.; McMahon, B.; Buchman, D.; Cai, M. Comparison of Hybrid Poplar Wood Breakeven Prices as Affected by Current and Improved Genetics; Technical Report NRRI/TR-2021/16; Natural Resources Research Institute: Hermantown, MN, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bolstad, P.V.; Vose, J.M.; McNulty, S.G. Forest productivity, leaf area, and terrain in Southern Appalachian deciduous forests. For. Sci. 2001, 47, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krinard, R.M.; Johnson, R.L. Cottonwood Plantation Growth Through 20 Years; Res Pap SO-212; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Forest Experiment Station: Asheville, NC, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Piggott, N.; Washburn, D. The 2024 Crop Comparison Tool (Crop-Comparison-Tool_2024_with_Yieldpredictor, Version 2-28-2024); Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, North Carolina State University: Raleigh, NC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://cals.ncsu.edu/agricultural-and-resource-economics/extension/business-planning-and-operations/enterprise-budgets (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Truax, B.; Fortier, J.; Gagnon, D.; Lambert, F. Planting density and site effects on stem dimensions, stand productivity, biomass partitioning, carbon stocks, and soil nutrient supply in hybrid poplar plantations. Forests 2018, 9, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christersson, L. Wood production potential in poplar plantations in Sweden. Biomass Bioenergy 2010, 34, 1289–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tullus, A.; Rytter, L.; Tullus, T.; Weih, M.; Tullus, H. Short-rotation forestry with hybrid aspen (Populus tremula L. × P. tremuloides Michx.) in Northern Europe. Scand. J. For. Res. 2011, 27, 10–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkai, K.; Végh, K.R.; Várallyay, G.; Farkas, C.S. Impacts of soil structure on crop growth. Int. Agrophysics 1997, 11, 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, J.B.; Broadfoot, W.M. A Practical Field Method of Site Evaluation for Commercially Important Southern Hardwoods; General Technical Report SO-26; USDA Forest Service, Southern Forest Experiment Station: Asheville, NC, USA, 1979. Available online: https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/gtr/uncaptured/gtr_so026.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- Stanturf, J.A.; von Oosten, C.; Netzer, D.A.; Colman, M.D.; Pritwood, C.J. Ecology and silviculture of poplar plantations. In Poplar Culture in North America; Dickman, D.I., Eckenwald, J.E., Richardson, J., Eds.; NRC Research Press, National Council Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2001; pp. 152–206. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, T.; Karacic, A. Increment and biomass in hybrid poplar and some practical implications. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 1925–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhlenius, H.; Övergaard, R.; Jämtgård, S. Influence of soil types on establishment and early growth of Populus trichocarpa. Open J. For. 2016, 6, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, A.; Calagari, M.; Ahmadloo, F. Effect of some soil properties on growth of three-year black poplar (Populus nigra L.) trees in poplar plantations in south of Tehran. Iran. J. For. Poplar Res. 2018, 26, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIvor, I.; Marden, M.; Douglas, G.; Hedderley, D.; Phillips, C. Influence of soil type on root development and above-and below-ground biomass of 1–3-year-old Populus deltoides × nigra grown from poles. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Nat. Resour. 2020, 24, 556138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, J.M.; Rood, S.B. Response of a hybrid poplar to water table decline in different substrates. For. Ecol. Manag. 1992, 54, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imada, S.; Yamanaka, N.; Tamai, S. Water table depth affects Populus alba fine root growth and whole plant biomass. Funct. Ecol. 2008, 22, 1018–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coomes, D.A.; Allen, R.B. Effects of size, competition and altitude on tree growth. J. Ecol. 2007, 95, 1084–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z. Variation of soil microsite moisture-physical properties and its effect on Fraxinus mandshurica juvenile stand growth. Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao 2001, 12, 335–338. [Google Scholar]

- Pinno, B.D.; Bélanger, N. Competition control in juvenile hybrid poplar plantations across a range of site productivities in Central Saskatchewan, Canada. New For. 2009, 37, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, Z.; Domec, J.C.; Oren, R.; Way, D.A.; Moshelion, M. Growth and physiological responses of isohydric and anisohydric poplars to drought. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 4373–4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Toribio, M.; Ibarra-Manríquez, G.; Navarrete-Segueda, A.; Paz, H. Topographic position, but not slope aspect, drives the dominance of functional strategies of tropical dry forest trees. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 085002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlway, W.H.; Cothron, C.P.; Chiang, A.; Ghezehei, S.; Nichols, E.G.; Whitehill, J. Potential for elite veneer poplar on marginal Phytophthora spp.–infected Christmas tree lands. Plant Dis. 2025, 109, 2114–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortier, J.; Truax, B.; Gagnon, D.; Lambert, F. Allometric equations for estimating compartment biomass and stem volume in mature hybrid poplars: General or site-specific? Forests 2017, 8, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.R.; Beall, F.D.; Hogan, G.D. Establishment-year height growth in hybrid poplars; relations with longer-term growth. New For. 1996, 12, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, N.D.; Berguson, W.E.; McMahon, B.G.; Cai, M.; Buchman, D.J. Growth performance and stability of hybrid poplar clones in simultaneous tests on six sites. Biomass Bioenergy 2018, 118, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, C.A.; Burley, J.; Cook, R.; Ghezehei, S.B.; Hazel, D.W.; Nichols, E.G. Tree water use, water use efficiency, and carbon isotope discrimination in relation to growth potential in Populus deltoides and hybrids under field conditions. Forests 2019, 10, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.