Interventions and Strategies to Improve Sexual and Reproductive Health Outcomes among Adolescents Living in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Background

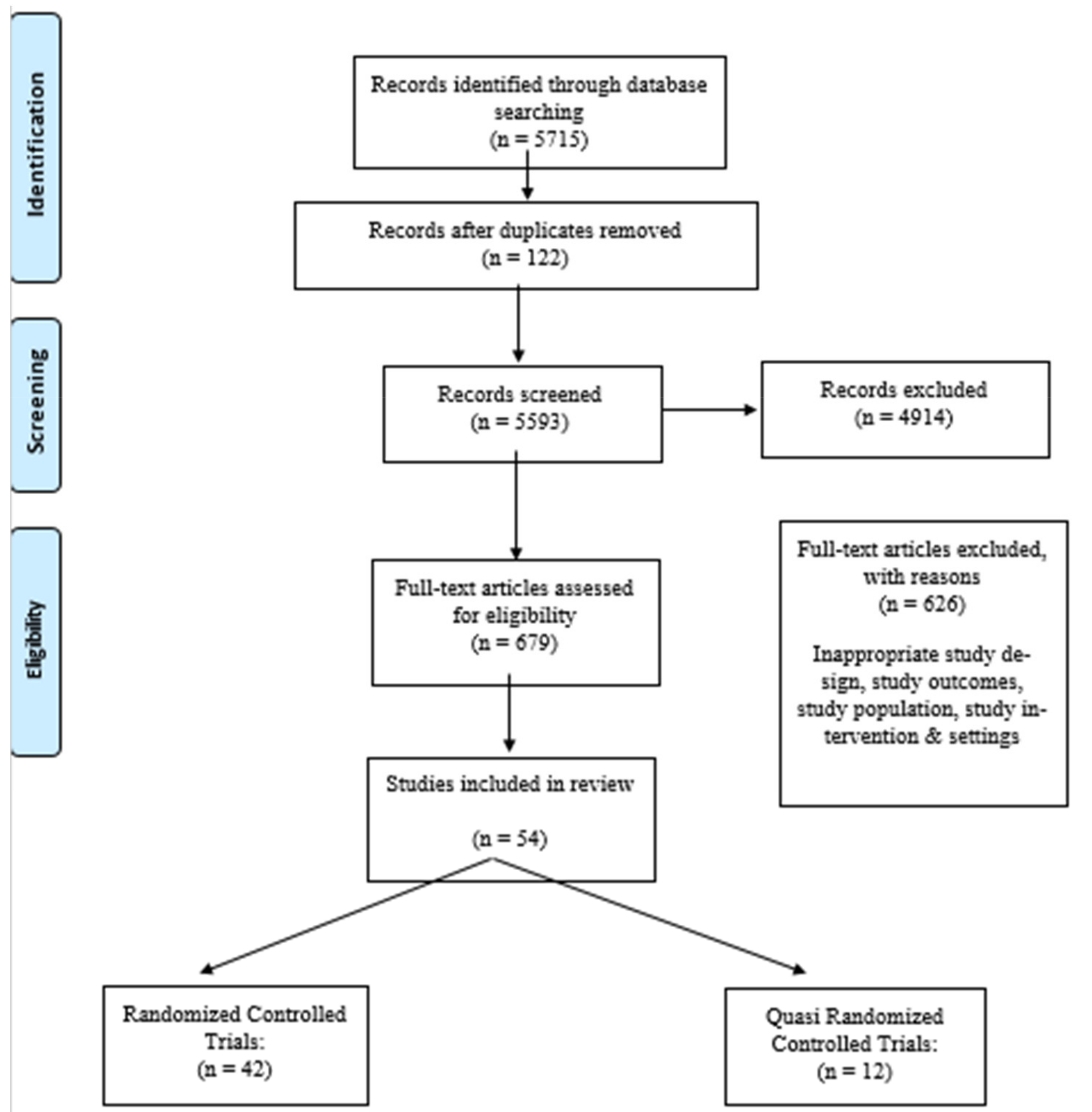

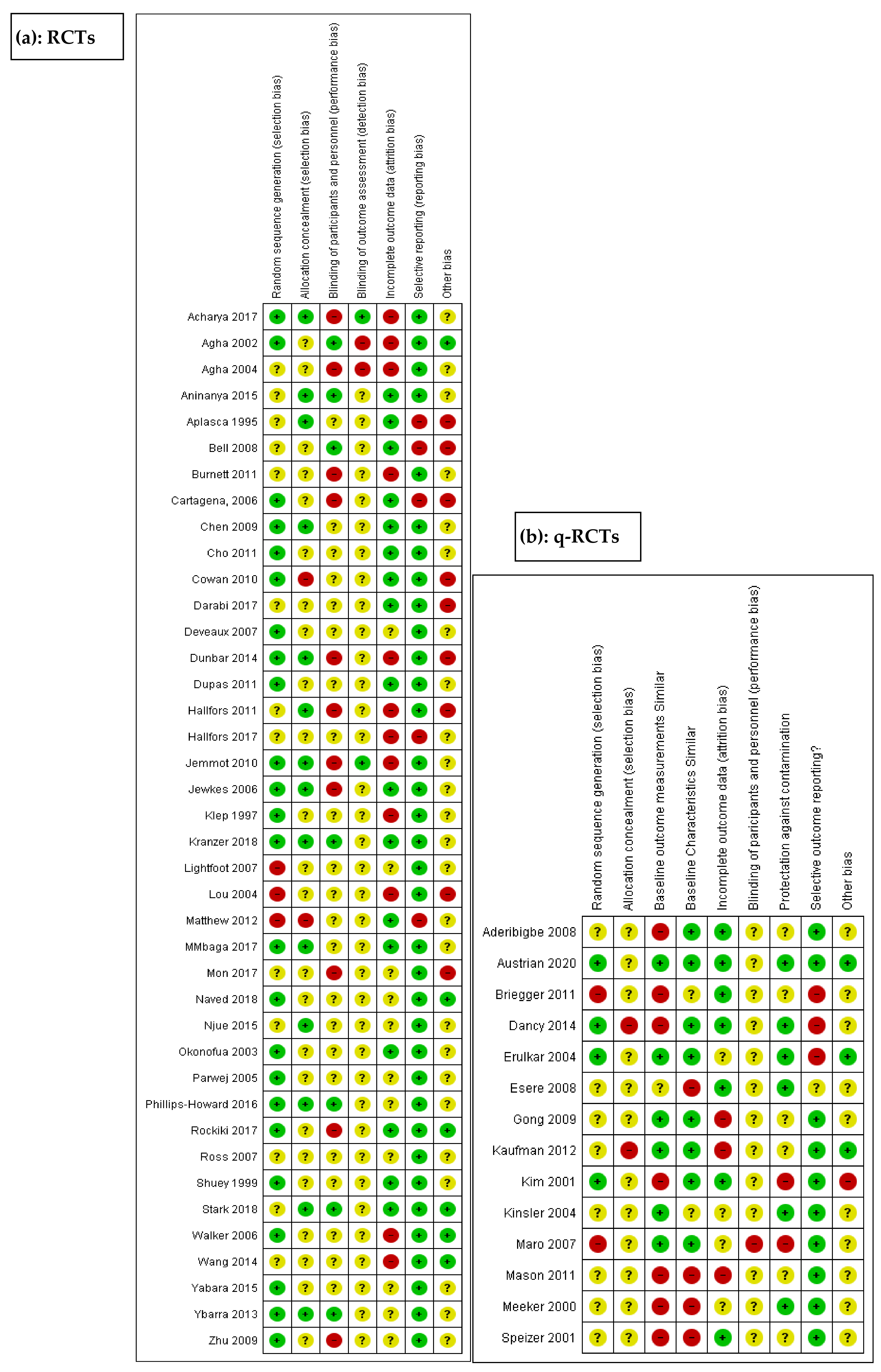

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Summary of Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (ASRHR) Interventions

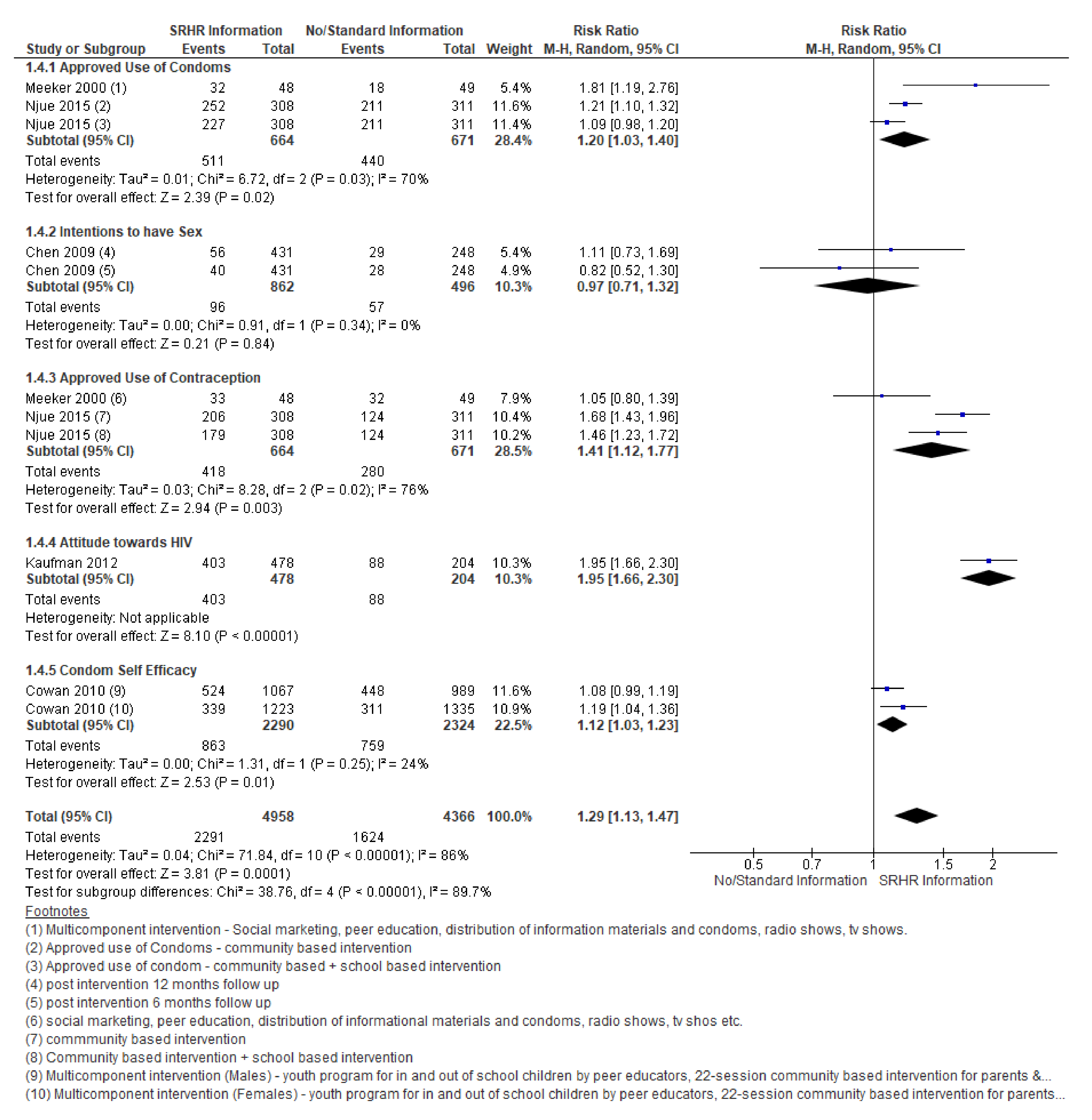

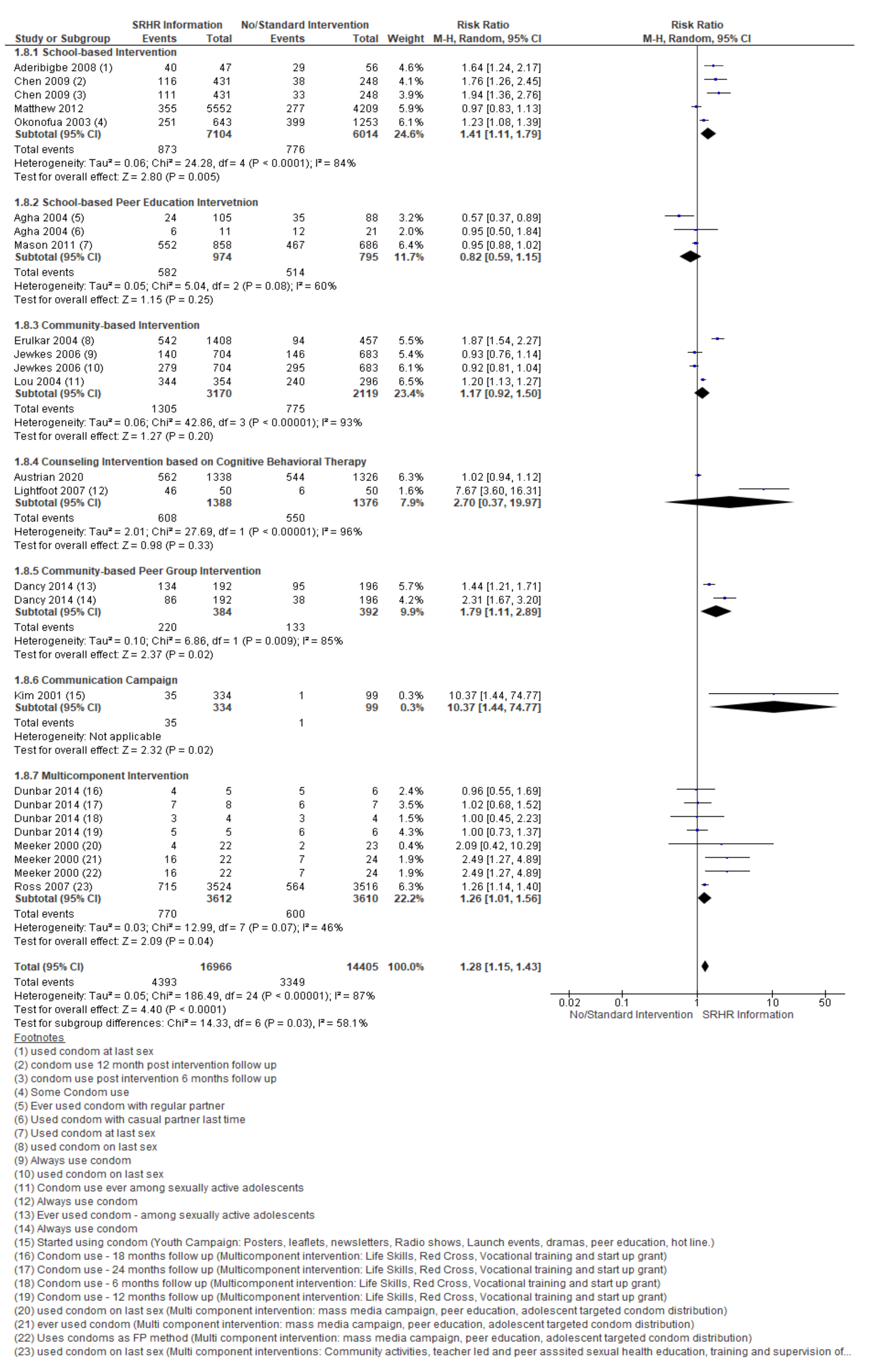

3.3. ASRHR Education Interventions

3.4. Provision of Financial Incentives to Improve the Uptake of HIV Testing and Counseling Services

3.5. Comprehensive Post-Abortion Family Planning Services

3.6. Comprehensive School Support to Adolescents in Schools

3.7. Provision of Menstrual Products to the School-Going Adolescents

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fatusi, A.O.; Hindin, M.J. Adolescents and youth in developing countries: Health and development issues in context. J. Adolesc. Health 2010, 33, 499–508. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20598362/ (accessed on 12 June 2021). [CrossRef]

- Desrosiers, A.; Betancourt, T.; Kergoat, Y.; Servilli, C.; Say, L.; Kobeissi, L. A systematic review of sexual and reproductive health interventions for young people in humanitarian and lower-and-middle-income country settings. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagata, J.M.; Hathi, S.; Ferguson, B.J.; Hindin, M.J.; Yoshida, S.; Ross, D.A. Research priorities for adolescent health in low- and middle-income countries: A mixed-methods synthesis of two separate exercises. J. Glob. Health 2018, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, M.D.; Engelman, R.; Levy, J.; Luchsinger, G.; Merrick, T.; Rosen, J.E. The power of 1.8 billion: Adolescents, youth and the transformation of the future. In State of the World Population; United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA): New York, NY, USA, 2014; p. 126. [Google Scholar]

- Dick, B.; Ferguson, B.J. Health for the world’s adolescents: A second chance in the second decade. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 56, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra-Mouli, V.; Camacho, A.V.; Michaud, P.A. WHO guidelines on preventing early pregnancy and poor reproductive outcomes among adolescents in developing countries. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 52, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Early Marriages, Adolescent and Young Pregnancies; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Salam, R.A.; Faqqah, A.; Sajjad, N.; Lassi, Z.S.; Das, J.K.; Kaufman, M.; Bhutta, Z.A. Improving adolescent sexual and reproductive health: A systematic review of potential interventions. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 59, S11–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatusi, A.O. Young people’s sexual and reproductive health interventions in Developing countries: Making the investments count. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 59, S1–S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, N. Motherhood in Childhood: Facing the Challenge of Adolescent Pregnancy; United Nations Population Fund State of World Population: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Pregnancy; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-pregnancy (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Ali, M.M.; Cleland, J. Sexual and reproductive behaviour among single women aged 15–24 in eight Latin American countries: A comparative analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 60, 1175–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Mahy, M. Sexual initiation among adolescent girls and boys: Trends and differentials in sub-Saharan Africa. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2003, 32, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bearinger, L.H.; Sieving, R.E.; Ferguson, J.; Sharma, V. Global perspectives on the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents: Patterns, prevention, and potential. Lancet 2007, 369, 1220–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettifor, A.E.; van der Straten, A.; Dunbar, M.S.; Shiboski, S.C.; Padian, N.S. Early age of first sex: A risk factor for HIV infection among women in Zimbabwe. AIDS 2004, 18, 1435–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon-Mueller, R. Starting young: Sexual initiation and HIV prevention in early adolescence. AIDS Behav. 2009, 13, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. HIV and Young People: The Threat for Today’s Youth, 2004 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic, 4th ed.; UNAIDS: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004; pp. 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The Millenium Development Goals Report 2008; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Available online: https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2008highlevel/pdf/newsroom/mdg%20reports/MDG_Report_2008_ENGLISH.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Paul-Ebhohimhen, V.A.; Poobalan, A.; van Teijlingen, E.R. A systematic review of school-based sexual health interventions to prevent STI/HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health 2008, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirby, D.; Obasi, A.; Laris, B.A. The effectiveness of sex education and HIV education interventions in schools in developing countries. In Preventing HIV/AIDS in Young People. A Systematic Review of the Evidence from Developing Countriee; Ross, D.A., Dick, B., Ferguson, J., Eds.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; pp. 103–150. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, D.B.; Laris, B.A.; Rolleri, L.A. Sex and HIV education programs: Their impact on sexual behaviors of young people throughout the world. J. Adolesc. Health 2007, 40, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Maternal Newborn Child and Adolescent Health. Making Health Services Adolescent Friendly: Developing National Quality Standards for Adolescent Friendly Health Services; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; Available online: http://www.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75217/1/9789241503594_eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Hindin, M.J.; Fatusi, A.O. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health in developing countries: An overview of trends and interventions. Int. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2009, 35, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agha, S.; Van Rossem, R. Impact of a school-based peer sexual health intervention on normative beliefs, risk perceptions, and sexual behavior of Zambian adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2004, 34, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenson, A.B.; Rahman, M. A randomized controlled study of two educational interventions on adherence with oral contraceptives and condoms. Contraception 2012, 86, 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonell, C.; Maisey, R.; Speight, S.; Purdon, S.; Keogh, P.; Wollny, I.; Sorhaindo, A.; Wellings, K. Randomized controlled trial of ‘teens and toddlers’: A teenage pregnancy prevention intervention combining youth development and voluntary service in a nursery. J. Adolesc. 2013, 36, 859–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, S.S.; Levine, D.K.; Black, S.R.; Schmiege, S.J.; Santelli, J. Social media-delivered sexual health intervention: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 43, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, J.B.; Dmochowski, J.; Boyer, C.; St Lawrence, J.; Lightfoot, M.; Moore, M. Text-messaging-enhanced HIV intervention for African American adolescents: A feasibility study. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2013, 24, 256–267. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3627821/ (accessed on 12 June 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. The World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Sterne, J.A.C.; on behalf of the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group and the Cochrane Bias Methods Group. 8.5 The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [Updated March 2011]; Higgins, J.P.T., Green, S., Eds.; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2011; Available online: http://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/ (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). EPOC Resources for Review Authors. 2017. Available online: Epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-resources-review-authors (accessed on 12 June 2020).

- Dancy, B.L.; Jere, D.L.; Kachingwe, S.I.; Kaponda, C.P.; Norr, J.L.; Norr, K.F. HIV Risk Reduction Intervention for Rural Adolescents in Malawi. J. HIV AIDS Soc. Serv. 2014, 13, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupas, P. Do teenagers respond to HIV risk information? Evidence from a field experiment in Kenya. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2011, 3, 1–34. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w14707 (accessed on 12 June 2021). [CrossRef]

- Erulkar, A.S.; Ettyang, L.I.; Onoka, C.; Nyagah, F.K.; Muyonga, A. Behavior change evaluation of a culturally consistent reproductive health program for young Kenyans. Int. Fam. Plan. Perspect. 2004, 30, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klepp, K.I.; Ndeki, S.S.; Leshabari, M.T.; Hannan, P.J.; Lyimo, B.A. AIDS education in Tanzania: Promoting risk reduction among primary school children. Am. J. Public Health 1997, 87, 1931–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightfoot, M.A.; Kasirye, R.; Comulada, W.S.; Rotheram-Borus, M.J. Efficacy of a culturally adapted intervention for youth living with HIV in Uganda. Prev. Sci. 2007, 8, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maro, C.N.; Roberts, G.C.; Sørensen, M. Using sport to promote HIV/AIDS education for at-risk youths: An intervention using peer coaches in football. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2009, 19, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mmbaga, E.J.; Kajula, L.; Aarø, L.E.; Kilonzo, M.; Wubs, A.G.; Eggers, S.M.; de Vries, H.; Kaaya, S. Effect of the PREPARE intervention on sexual initiation and condom use among adolescents aged 12–14: A cluster randomised controlled trial in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njue, C.; Voeten, H.A.C.M.; Ohuma, E.; Looman, C.; Habbema, D.F.; Askew, I. Findings of an evaluation of community and school-based reproductive health and HIV prevention programs in Kenya. Afr. Pop. Stud. 2015, 29, 1934–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Stark, L.; Asghar, K.; Seff, I.; Yu, G.; Tesfay Gessesse, T.; Ward, L.; Bayse, A.A.; Neiman, A.; Falb, K.L. Preventing violence against refugee adolescent girls: Findings from a cluster randomised controlled trial in Ethiopia. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e000825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuey, D.A.; Babishangire, B.B.; Omiat, S.; Bagarukayo, H. Increased sexual abstinence among in-school adolescents as a result of school health education in Soroti district, Uganda. Health Educ. Res. 1999, 14, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, D.A.; Changalucha, J.; Obasi, A.I.; Todd, J.; Plummer, M.L.; Cleophas-Mazige, B.; Anemona, A.; Everett, D.; Weiss, H.A.; Mabey, D.C.; et al. Biological and behavioural impact of an adolescent sexual health intervention in Tanzania: A community-randomized trial. AIDS 2007, 21, 1943–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybarra, M.L.; Bull, S.S.; Prescott, T.L.; Korchmaros, J.D.; Bangsberg, D.R.; Kiwanuka, J.P. Adolescent abstinence and unprotected sex in CyberSenga, an Internet-based HIV prevention program: Randomized clinical trial of efficacy. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybarra, M.L.; Korchmaros, J.D.; Prescott, T.L.; Birungi, R. A Randomized Controlled Trial to Increase HIV Preventive Information, Motivation, and Behavioral Skills in Ugandan Adolescents. Ann. Behav. Med. 2015, 49, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, C.C.; Bhana, A.; Petersen, I.; McKay, M.M.; Gibbons, R.; Bannon, W.; Amatya, A. Building protective factors to offset sexually risky behaviors among black youths: A randomized control trial. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2008, 100, 936–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, S.M.; Weaver, M.R.; Mody-Pan, P.N.; Thomas, L.A.; Mar, C.M. Evaluation of an intervention to increase human immunodeficiency virus testing among youth in Manzini, Swaziland: A randomized control trial. J. Adolesc. Health 2011, 48, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowan, F.M.; Pascoe, S.J.; Langhaug, L.F.; Mavhu, W.; Chidiya, S.; Jaffar, S.; Mbizvo, M.T.; Stephenson, J.M.; Johnson, A.M.; Power, R.M.; et al. The Regai Dzive Shiri project: Results of a randomized trial of an HIV prevention intervention for youth. AIDS 2010, 24, 2541–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemmott, J.B.; Jemmott, L.S.; O’Leary, A.; Ngwane, Z.; Icard, L.D.; Bellamy, S.L.; Jones, S.F.; Landis, J.R.; Heeren, G.A.; Tyler, J.C.; et al. School-based randomized controlled trial of an HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention for South African adolescents. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2010, 164, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewkes, R.; Nduna, M.; Levin, J.; Jama, N.; Dunkle, K.; Khuzwayo, N.; Koss, M.; Puren, A.; Wood, K.; Duvvury, N. A cluster randomized-controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of Stepping Stones in preventing HIV infections and promoting safer sexual behaviour amongst youth in the rural Eastern Cape, South Africa: Trial design, methods and baseline findings. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2006, 11, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.M.; Kols, A.; Nyakauru, R.; Marangwanda, C.; Chibatamoto, P. Promoting sexual responsibility among young people in zimbabwe. Int. Fam. Plan. Perspect. 2001, 27, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason-Jones, A.J.; Mathews, C.; Flisher, A.J. Can peer education make a difference? Evaluation of a South African adolescent peer education program to promote sexual and reproductive health. AIDS Behav. 2011, 15, 1605–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, C.; Aaro, L.E.; Grimsrud, A.; Flisher, A.J.; Kaaya, S.; Onya, H.; Schaalma, H.; Wubs, A.; Mukoma, W.; Klepp, K.-I. Effects of the SATZ teacher-led school HIV prevention programmes on adolescent sexual behaviour: Cluster randomised controlled trials in three sub-Saharan African sites. Int. Health 2012, 4, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meekers, D. The effectiveness of targeted social marketing to promote adolescent reproductive health: The case of soweto, south africa. J. HIV AIDS Prev. Child. Youth 2000, 3, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderibigbe, S.; Araoye, M. Effect of health education on sexual behaviour of students of public secondary schools in ilorin, nigeria. Eur. J. Sci Res. 2008, 24, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Aninanya, G.A.; Debpuur, C.Y.; Awine, T.; Williams, J.E.; Hodgson, A.; Howard, N. Effects of an adolescent sexual and reproductive health intervention on health service usage by young people in northern Ghana: A community-randomised trial. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brieger, W.R.; Delano, G.E.; Lane, C.G.; Oladepo, O.; Oyediran, K.A. West African youth initiative: Outcome of a reproductive health education program. J. Adolesc. Health 2001, 29, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, M.S.; Kang Dufour, M.S.; Lambdin, B.; Mudekunye-Mahaka, I.; Nhamo, D.; Padian, N.S. The SHAZ! project: Results from a pilot randomized trial of a structural intervention to prevent HIV among adolescent women in Zimbabwe. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esere, M.O. Effect of Sex Education Programme on at-risk sexual behaviour of school-going adolescents in Ilorin, Nigeria. Afr. Health Sci. 2008, 8, 120–125. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19357762/ (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Okonofua, F.E.; Coplan, P.; Collins, S.; Oronsaye, F.; Ogunsakin, D.; Ogonor, J.T.; Kaufman, J.A.; Heggenhougen, K. Impact of an intervention to improve treatment-seeking behavior and prevent sexually transmitted diseases among Nigerian youths. Int. J. Infect. Dis 2003, 7, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokicki, S.; Cohen, J.; Salomon, J.A.; Fink, G. Impact of a Text-Messaging Program on Adolescent Reproductive Health: A Cluster-Randomized Trial in Ghana. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha, S. An evaluation of the effectiveness of a peer sexual health intervention among secondary-school students in Zambia. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2002, 14, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austrian, K.; Soler-Hampejsek, E.; Behrman, J.R.; Digitale, J.; Jackson Hachonda, N.; Bweupe, M.; Hewett, P.C. The impact of the Adolescent Girls Empowerment Program (AGEP) on short and long term social, economic, education and fertility outcomes: A cluster randomized controlled trial in Zambia. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speizer, I.S.; Tambashe, B.O.; Tegang, S.P. An evaluation of the “Entre Nous Jeunes” peer-educator program for adolescents in Cameroon. Stud. Fam. Plann. 2001, 32, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Hallfors, D.D.; Mbai, I.I.; Itindi, J.; Milimo, B.W.; Halpern, C.T.; Iritani, B.J. Keeping adolescent orphans in school to prevent human immunodeficiency virus infection: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial in Kenya. J. Adolesc. Health 2011, 48, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hallfors, D.D.; Cho, H.; Hartman, S.; Mbai, I.; Ouma, C.A.; Halpern, C.T. Process Evaluation of a Clinical Trial to Test School Support as HIV Prevention Among Orphaned Adolescents in Western Kenya. Prev. Sci. 2017, 18, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallfors, D.; Cho, H.; Rusakaniko, S.; Iritani, B.; Mapfumo, J.; Halpern, C. Supporting adolescent orphan girls to stay in school as HIV risk prevention: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial in Zimbabwe. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, 1082–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kranzer, K.; Simms, V.; Bandason, T.; Dauya, E.; McHugh, G.; Munyati, S.; Chonzi, P.; Dakshina, S.; Mujuru, H.; Weiss, H.A.; et al. Economic incentives for HIV testing by adolescents in Zimbabwe: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet HIV 2018, 5, e79–e86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips-Howard, P.A.; Nyothach, E.; Ter Kuile, F.O.; Omoto, J.; Wang, D.; Zeh, C.; Onyango, C.; Mason, L.; Alexander, K.T.; Odhiambo, F.O.; et al. Menstrual cups and sanitary pads to reduce school attrition, and sexually transmitted and reproductive tract infections: A cluster randomised controlled feasibility study in rural Western Kenya. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e013229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darabi, F.; Yaseri, M.; Kaveh, M.H.; Khalajabadi Farahani, F.; Majlessi, F.; Shojaeizadeh, D. The Effect of a Theory of Planned Behavior-based Educational Intervention on Sexual and Reproductive Health in Iranian Adolescent Girls: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Res. Health Sci. 2017, 17, e00400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mon, M.; Liabsuetrakul, T.; McNeil, E.B.; Htut, K. Mindfulness-integrated reproductive health package for adolescents with parental HIV infection: A group-randomized controlled trial. Vulnerable Child. Youth Stud. 2017, 12, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parwej, S.; Kumar, R.; Walia, I.; Aggarwal, A.K. Reproductive health education intervention trial. Indian J. Pediatr. 2005, 72, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naved, R.T.; Mamun, M.A.; Mourin, S.A.; Parvin, K. A cluster randomized controlled trial to assess the impact of SAFE on spousal violence against women and girls in slums of Dhaka, Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Wang, B.; Shen, Y.; Gao, E.S. Effects of a Community-based Sex Education and Reproductive Health Service Program on Contraceptive Use of Unmarried Youths in Shanghai. J. Adoles. Health 2004, 34, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, D.; Thomas, M.; Cann, R. Evaluating school-based sexual health education programme in nepal: An outcome from a randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 82, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aplasca, M.R.; Siegel, D.; Mandel, J.S.; Santana-Arciaga, R.T.; Paul, J.; Hudes, E.S.; Monzon, O.T.; Hearst, N. Results of a model AIDS prevention program for high school students in the Philippines. AIDS 1995, 9 (Suppl. 1), S7–S13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cartagena, R.G.; Veugelers, P.J.; Kipp, W.; Magigav, K.; Laing, L.M. Effectiveness of an HIV prevention program for secondary school students in Mongolia. J. Adolesc. Health 2006, 39, 925.e9–925e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.L.; Zhang, W.H.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, J.; Xu, X.; Gibson, D.; Støvring, H.; Claeys, P.; Temmerman, M. Impact of post-abortion family planning services on contraceptive use and abortion rate among young women in China: A cluster randomised trial. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2009, 14, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, Z.A.; Welsch, R.L.; Erickson, J.D.; Craig, S.; Adams, L.V.; Ross, D.A. Effectiveness of a sports-based HIV prevention intervention in the Dominican Republic: A quasi-experimental study. AIDS Care 2012, 24, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Walker, D.; Gutierrez, J.P.; Torres, P.; Bertozzi, S.M. HIV prevention in Mexican schools: Prospective randomised evaluation of intervention. BMJ 2006, 332, 1189–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinsler, J.; Sneed, C.D.; Morisky, D.E.; Ang, A. Evaluation of a school-based intervention for HIV/AIDS prevention among Belizean adolescents. Health Educ. Res. 2004, 19, 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Stanton, B.; Lunn, S.; Deveaux, L.; Li, X.; Marshall, S.; Brathwaite, N.V.; Cottrell, L.; Harris, C.; Chen, X. Effects through 24 months of an HIV/AIDS prevention intervention program based on protection motivation theory among preadolescents in the Bahamas. Pediatrics 2009, 123, e917–e928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lunn, S.; Deveaux, L.; Li, X.; Brathwaite, N.; Cottrell, L.; Stanton, B. A cluster randomized controlled trial of an adolescent HIV prevention program among Bahamian youth: Effect at 12 months post-intervention. AIDS Behav. 2009, 13, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveaux, L.; Stanton, B.; Lunn, S.; Cottrell, L.; Yu, S.; Brathwaite, N.; Li, X.; Liu, H.; Marshall, S.; Harris, C. Reduction in human immunodeficiency virus risk among youth in developing countries. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2007, 161, 1130–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Wang, B.; Stanton, B.; Deveaux, L.; Li, X.; Koci, V.; Lunn, S. The impact of parent involvement in an effective adolescent risk reduction intervention on sexual risk communication and adolescent outcomes. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2014, 26, 500–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guse, K.; Levine, D.; Martins, S.; Lira, A.; Gaarde, J.; Westmorland, W.; Gilliam, M. Interventions using new digital media to improve adolescent sexual health: A systematic review. J. Adolesc. Health 2012, 51, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feroz, A.S.; Ali, N.A.; Khoja, A.; Asad, A.; Saleem, S. Using mobile phones to improve young people sexual and reproductive health in low and middle-income countries: A systematic review to identify barriers, facilitators, and range of mHealth solutions. Repro. Health 2021, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wekesah, F.M.; Mbada, C.E.; Muula, A.S.; Kabiru, C.W.; Muthuri, S.K.; Izugbara, C.O. Effective non-drug interventions for improving outcomes and quality of maternal health care in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, D. Postabortion Care and the Voluntary Family Planning Component: Expanding Contraceptive Choices and Service Options. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2019, 7 (Suppl. 2), S207–S210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High Impact Practices in Family Planning. Postabortion Family Planning: Strengthening the Family Planning Component of Postabortion Care; USAID: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Population Fund. Girlhood, not motherhood. In Preventing Adolescent Pregnancy; United Nations Population Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr, R.; Carbajal, J.; Sharma, B.B. The influence of educational attainment on teenage pregnancy in low-income countries: A systematic literature review. J. Soc. Work Glob. Community 2019, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eijk, A.M.; Zulaika, G.; Lenchner, M.; Mason, L.; Sivakami, M.; Nyothach, E.; Unger, H.; Laserson, K.; Phillips-Howard, P.A. Menstrual cup use, leakage, acceptability, safety, and availability: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e376–e393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S # | First Author, Year | Country and Setting | Study Design | Target Population/Sex | Total Participants | Intervention | Control Group | Outcome (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison Group 1: SRHR Information vs. No Information or Standard Intervention | ||||||||

| 1 | Cowan 2010 [48] | Zimbabwe; community setting | RCT | 12–24 years | Intervention: 2319 Control: 2353 Total: 4672 | Community-based multi component HIV and reproductive health intervention (youth program for in and out of school youth, community-based program for parents and community stakeholders and training program for nurses and other staff in rural clinics) (n age 18–20 = 1557) | No intervention | Knowledge, attitude and behavior of young men and women towards SRHR, Prevalence of HIV, HSV2 and pregnancy |

| 2 | Dancy 2014 [33] | Malawi; community setting | qRCT | Males and females aged 13–19 years | Intervention: 384 Control: 393 Total: 777 | HIV risk reduction community-based peer group intervention | No intervention | HIV knowledge and attitude, HIV risk reduction behaviors, self-efficacy for condom use and safer sex |

| 3 | Kaufman 2012 [79] | Dominican Republic; community | qRCT | Adolescents | Intervention: 99 Control: 41 Total: 140 | Sports-based HIV prevention intervention | No intervention | HIV-related knowledge, attitudes, and communication |

| 4 | Meekers 2000 [54] | Soweto and Umlazi districts, South Africa; community setting | qRCT | Adolescents aged between 17–20 years | Intervention: 219 Control: 211 Total: 420 | Targeted social marketing program on reproductive health beliefs and behaviors via radio, TV, information booklet on adolescent reproductive health | No intervention | Knowledge of risk of pregnancy, condom use, HIV/AIDS prevention |

| 5 | Ross 2007 [43] | Tanzania; community setting | RCT | Primary school | Intervention: 2607 Control: 2496 Total: 9645 | Multi component intervention (community activities, teacher-led, peer-assisted sexual health education, training and supervision of health workers to provide YFHS, peer-based condom social marketing) | Standard activities | Knowledge and reported attitudes towards SRHR, reported STIs and pregnancy rates |

| 6 | Walker 2006 [80] | Morelos, Mexico; school setting | RCT | Students aged 15–18 years) | Intervention: 5617 Control: 1867 Total: 7484 | School based HIV prevention programme | Biology-based sex education course | Condom use, knowledge and attitude towards HIV and emergency contraception |

| 7 | Kinsler 2004 [81] | Belize City, Belize; school setting | qRCT | adolescents (aged 13–17) | Intervention: 75 Control: 75 Total: 150 | Cognitive behavioral peer-facilitated school-based HIV/AIDS education program | HIV/AIDS educational Handbook | HIV knowledge, Condom use, condom attitudes, condom intentions, condom self-efficacy |

| 8 | Brieger 2001 [57] | Nigeria and Ghana; school setting | qRCT | Male and Female adolescents | Intervention: 908 Control: 893 Total: 1801 | Adolescent reproductive health peer education program | No intervention | Reproductive health knowledge, contraceptive use, willingness to buy contraceptives, self-efficacy in contraceptive use |

| 9 | Darabi 2017 [70] | Iran; school setting | RCT | First Year High School girls (12–16 years) | Intervention: 289 Control: 289 Total: 578 | Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) school-based educational intervention on sexual and reproductive health with adolescents and parents | No intervention | SRHR behavior and attitude, subjective norms, perceived parental control and perceived behavioral control |

| 10 | Gong, 2009 [82] | Bahamas; school and community | qRCT | preadolescents aged 10–14 years | Intervention Group 1:436 Intervention Group 2: 427 Control Group: 497 Total: 1360 | HIV/AIDS Prevention Intervention program based on Protection Motivation Theory (Intervention Group 1: Youth HIV intervention + Parental HIV education intervention; Intervention Group 2: Youth HIV intervention + parental goal setting intervention | Youth environmental protection intervention + parental goal setting intervention | HIV/AIDS knowledge, sexual perception and condom use intention |

| 11 | Mon, 2017 [71] | Myanmar; community setting | RCT | Adolescents aged 10–16 years with HIV-infected parent(s) | Intervention: 72 Control: 72 Total: 144 | Mindfulness-integrated reproductive health intervention | Group activities conducted including playing games, preparing food and eating together at the office of people living with HIV | Reproductive health knowledge |

| 12 | Parwej 2005 [72] | Chandigarh, India; school setting | RCT | 15–19 years. | Intervention Group 1—Peer education: 84 Intervention Group 2—Conventional education by nurses: 95 Control Group: 94 Total: 273 | Reproductive Health Education via peer education and conventional education in schools | No intervention | Reproductive health knowledge |

| 13 | Kim, 2001 [51] | Zimbabwe; community setting | qRCT | 10–24 years male and female | Intervention: 1000 Control: 400 Total: 1400 | Multimedia campaign (posters, leaflets, newsletters, radio program, launch events, theatre programs, peer education and hot line) with youth to promote SRHR | No intervention | Knowledge of family planning methods, adoption of safe sexual behaviors and uptake of sexual health services |

| 14 | Shuey 1999 [42] | Soroti, Uganda; school setting | RCT | 13–14 years male and female students | Intervention: 567 Control: 233 Total: 800 | School health education programme on AIDS prevention | Standard school health AIDS education program of Uganda | Sexual abstinence, safe sexual behaviors and communication regarding sexual matters with teachers and peers |

| 15 | Njue 2015 [40] | Kenya; community and school settings | RCT | 10–19 years | Community Intervention Group 1: 1232 Community + school-based intervention Group 2: 1279 Control: 1247 Total: 3758 | Community and school-based reproductive health HIV program | No intervention | Knowledge, attitude and behavior towards SRHR |

| 16 | Chen 2009 [83] | Bahamas; school setting | RCT | Sixth grade aged 10–11 years | Intervention: 863 Control: 497 Total: 1360 | School based adolescent HIV prevention program | Wondrous Wetlands Conservation program focusing on water conservation, wildlife and other natural resources | Sexual behavior |

| 17 | Jewkes 2006 [50] | Eastern Cape, South Africa; community setting | RCT | Young people aged 16–23 | Intervention: 1409 Control: 1367 Total: 2776 | 17 community-based behavioral intervention sessions aimed at reducing HIV incidence were conducted | 1 community- based session on HIV and safer sex was conducted | HIV incidences, knowledge and attitude towards SRHR, HIV related sexual behavior risk factors |

| 18 | Naved 2018 [73] | Bangladesh; community setting | RCT | Women aged 15–29 | Intervention: 2670 Control: 1026 Total: 3696 | Multisectoral, multi-tier 20-month SAFE program (interactive sessions on gender health, rights and life skills; community campaign; health and legal services and referrals) | Community campaign and SAFE health and legal services | Physical, sexual, economic and emotional intimate partner violence |

| 19 | Stark 2018 [41] | Ethiopia; community setting | RCT | Refugee adolescent girls ages 13–19 years. | Intervention: 457 Control: 462 Total: 919 | Life skills and safe spaces program | No intervention | Sexual violence, physical violence, emotional violence, transactional sex and child marriage |

| 20 | Dunbar 2014 [58] | Zimbabwe; community setting | RCT | Female adolescents and maternal orphans aged 16–19 years (out of school) | Intervention: 158 Control: 157 Total: 315 | Shaping the Health of Adolescents in Zimbabwe—SHAZ program focusing on HIV and SRH services, life skills-based HIV education, vocational training and provision of micro grant to improve economic outcomes and integrated social support. | Life skills-based HIV education, reproductive health services and home-based care training | Economic and social empowerment, sexual risk behaviors, HIV/STI prevalence and unintended pregnancy |

| 21 | Erulkar 2004 [35] | Nairobi, Kenya; community setting | qRCT | Unmarried young people aged 10–24 years | Intervention: 1408 Control: 457 Total: 1865 | Life skills-based curriculum was implemented by training health educators who conducted door to door visits in the community | No intervention | Reproductive health–related behaviors, condom use and communication between adolescents and parents/adult on SRHR |

| 22 | Lou 2004 [74] | Shanghai, China; community setting | RCT | Unmarried youth aged 15–24 years | Intervention: 1220 Control: 1007 Total: 2227 | Community-based interventions to promote contraceptive use (dissemination of educational materials, videos and lectures, provision of FP counseling at youth health centre and provision to access to FP services at FP unit) | No intervention | Contraceptive use |

| 23 | Lightfoot 2007 [37] | Uganda; community setting | RCT | Youth aged 14–21 years | Intervention: 50 Control: 50 Total: 100 | Culturally adopted HIV prevention program | No intervention | Condom use, number of sexual partners |

| 24 | Ybarra 2013 [44] | Uganda, secondary schools setting | RCT | Youth aged 12 years and older | Intervention: 183 Control: 183 Total: 366 | Cyber Senga—An internet-based HIV prevention program | School-based sexuality education program | Abstinence, sexual behavior and unprotected vaginal sex |

| 25 | Agha 2004 [24] | Zambia; school setting | RCT | Male and female adolescents in grades 10 and 11 aged 14–23 years | Intervention: 254 Control: 162 Total: 416 | School-based peer sexual health intervention | Peer education session on water purification | Knowledge and normative beliefs about abstinence, condom use, HIV risk perception and sexual behaviors |

| 26 | Aderibigbe 2008 [55] | Nigeria; public secondary schools setting | qRCT | Adolescents aged 10–19 years | Intervention: 262 Control: 259 Total: 521 | Health Education Sessionon risky sexual behaviour | No intervention | Condom use, sexual partners and frequency of sexual intercourse |

| 27 | Mathew 2012 [53] | Cape Town and Mankweng, South Africa, and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; school setting | RCT | Adolescents aged 12–14 years | Intervention: 6801 Control: 5338 Total: 12,139 | Teacher-led school HIV prevention programmes | No intervention | Delayed sexual debut and condom use |

| 28 | Okonofua 2003 [60] | Nigeria; school settings | RCT | Youth aged 14–20 years | Intervention: 643 Control: 1253 Total: 1896 | Creation of reproductive health clubs in schools to conduct health awareness campaigns on STD, training of club members as peer educators on STD prevention and treatment and training of health care professionals on STD | No intervention | STD symptoms, condom use, treatment seeking behavior and notification of partners by adolescents on STD symptoms |

| 29 | Mason-Jones 2011 [52] | Western Cape, South Africa; school setting | qRCT | Grade 10 students(aged 15–16 years) | Intervention: 2049 Control: 1885 Total: 3934 | Peer education program on relationships, sexual health and well-being and confidence building | Usual life orientation program | Age of sexual debut and condom use |

| 30 | Wang 2014 [85] | Bahamas; school setting | RCT | Grade 10 students aged 13–17 years | Intervention Group 1—Bahamian Focus on Older Youth (BFOOY) + Caribbean Informed Parents and Children Together—CiMPACT): 664 youth and 505 parents Intervention Group 2—BFOOY + Goal Focused Intervention: 559 youth and 387 parents Intervention Group 3—BFOOY only: 569 youth and 389 parents Control Group—Healthy Family Life Education: 772 youth and 552 parents Total: 2564 youth and 1833 parents | Parental involvement in an effective risk reduction intervention program (BFOOY + CiMPACT) | Existing Bahamian Healthy Family Life Education program (HFLE) | Sexual Debut Condom use |

| 31 | Rokicki 2017 [61] | Ghana; Community setting | RCT | Adolescents aged 14–24 years | Intervention Group 1—Unidirectional: 239 Intervention Group 2—Interactive: 196 Control Group: 273 Total: 708 | Intervention Group 1: Text- messages with reproductive health information Intervention Group 2: Engaging adolescents in text-messaging reproductive health quizzes | Placebo messages with information about malaria | Reproductive health knowledge, pregnancy risk and use of contraceptive methods |

| 32 | Jemmott 2010 [49] | Eastern Cape, South Africa; primary school setting | RCT | Grade 6 learners | Intervention: 545 Control: 477 Total: 1022 | School-based HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention | Health promotion intervention focusing on Non-communicable diseases | Unprotected vaginal intercourse, anal intercourse, sexually inexperienced and multiple sexual partners |

| 33 | Speizer 2001 [64] | Cameroon; community setting | qRCT | Adolescents aged 12–25 Years | Intervention: 403 Control: 413 Total: 815 | Peer-based adolescent reproductive health intervention | No intervention | Contraceptive prevalence, prevalence of STI/HIV and unintended pregnancy |

| 34 | Dupas 2011 [34] | Kenya; community setting | RCT | Teenagers | Intervention Group 1: 164 schools Intervention Group 2: 71 schools Control Group: 93 schools Total: 328 | Intervention 1: The Teacher Training (TT) Program on National HIV Prevention Curriculum Intervention 2: TT program + The Relative Risk Information Campaign—information on distribution of HIV information by age and gender | No intervention | Teen childbearing, pregnancies and self reported sexual behavior |

| 35 | Maro 2009 [38] | Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; in and out of school settings | qRCT | Adolescents aged 12–15 years | Intervention Group 1: 200 Intervention Group 2: 200 Control Group 1:200 Control Group 2: 200 Total: 800 | Intervention Group 1: Using peer coaches and sports to promote HIV/AIDS education with mastery coaching strategies Intervention Group 2: Using peer coaches and sports to promote HIV/AIDS education without mastery coaching strategies | Control Group 1: In-school children received traditional AIDS program Control Group 2: Out-of-school children received no education | HIV/AIDS knowledge |

| 36 | Deveaux 2007 [84] | Bahamas; school setting | RCT | Sixth-grade students | Intervention Group 1—FOYC or CiMPACT: 822 youth and 238 parents Control Group 1—WW or GFI: 460 youth and 528 parents Intervention Group 2a—FOYC + CiMPACT: 417 youth and 238 parents Intervention Group 2b—FOYC + GFI: 405 youth and 222 parents Control Group 2—WW + GFI: 460 youth and 306 parents Total: 4096 | Intervention Group 1—FOYC or CiMPACT Intervention Group—2a: FOYC + CiMPACT Intervention Group 2b: FOYC + GFI | Control Group 1: WW or GFI Control Group 2: WW + GFI | HIV risk and protective knowledge, condom use skills, perceptions, interventions and self-reported behaviors |

| 37 | Acharya 2017 [75] | Nepal; school setting | RCT | Secondary school children aged 14–18 years | Intervention: 201 Control: 247 Total: 448 | School based sex education intervention programme using participatory based approach | Conventional teacher-led sex education program | Knowledge and understanding of sexual health |

| 38 | Agha 2002 [62] | Zambia; school setting | RCT | Male and female adolescents grades 10–12 | Intervention: 421 Control: 338 Total: 759 | School-based peer sexual health intervention (education session about HIV/AIDS) | 1-h long session on water purification with the students | Knowledge and positive normative beliefs about abstinence and condoms perception of acquiring HIV |

| 39 | Aplasca 1995 [76] | Philippines; school setting | RCT | Adolescents in high schools | Intervention: 420 Control: 384 Total: 804 | Development and implementation of AIDS prevention program for high school students | No intervention | AIDS related knowledge, attitudes, and preventive behaviours and intended onset of sexual activity |

| 40 | Burnett 2011 [47] | Swaziland; school setting | RCT | Youth | Intervention: 69 Control: 66 Total: 135 | Life skills-based education program | No intervention | HIV knowledge, self-efficacy for abstinence and condom use |

| 41 | Cartagena 2006 [77] | Mongolia; school setting | RCT | Secondary School Students | Intervention: 320 Control: 327 Total: 647 | Sexual health peer education program focusing on life skills for HIV awareness and prevention, computer technology, job readiness, community outreach and a mobile HIV testing unit | No intervention | HIV knowledge, self-efficacy for abstinence, condom use and HIV tests |

| 42 | Esere 2008 [59] | Nigeria; school setting | qRCT | School-going adolescents aged 13–19 years | Intervention: 12 Control: 12 Total: 24 | Sex education programme | No intervention | STDs, multiple sexual partners, anal sex, oral sex and non-use of condom |

| 43 | Aninanya 2015 [56] | Ghana; community setting | RCT | Adolescents aged 10–24 years | Intervention: 1288 Control: 1376 Total: 2664 | Adolescents school-based curriculum and peer outreach activities | Community mobilization and Youth Friendly Health Services (YFHS) provider training | Uptake of ASRH services for STI management, HIV counselling and testing, antenatal and peri/postnatal services |

| 44 | Ybarra 2015 [45] | Uganda; school setting | RCT | Students aged 13–18 years | 366 participants were randomly assigned to the intervention and control group | Internet-based HIV prevention program | School-based sexuality education program | HIV information, condom use and abstinence |

| 45 | Bell 2008 [46] | South Africa; school setting | RCT | Youth aged 9–13 years | Intervention: 245 Control: 233 Total: 475 | Collaborative HIV Adolescent Mental Health Program South Africa (CHAMPSA) | Existing school-basedHIV prevention curriculum | HIV transmission knowledge HIV stigma |

| 46 | Mmbaga 2017 [39] | Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; school setting | RCT | Adolescents aged 12–14. | Intervention: 2503 Control: 2588 Total: 5091 | PREPARE—an educational program consisted of 3 components: teachers, peer educators and health care providers at youth friendly health clinics, aiming to address adolescents risky sexual and reproductive health behaviors | No intervention | Sexual Debut Condom Use |

| 47 | Klepp 1997 [36] | Tanzania, school setting | RCT | Sixth Grade Students (Average age 13.6 years) | Intervention: 258 Control: 556 Total: 814 | Local HIV/AIDS education program | No intervention | HIV/AIDS related information, knowledge, communication attitudes and behavioral intentions |

| 48 | Austrian 2020 [63] | Zambia; community setting | cRCT | Adolescents 10–19 years girls | Interventions: 3978 Control: 1326 Total: 5304 | Adolescent Girls Empowerment program on mentor-led, girls group meetings on health, life skills and financial education | No intervention | Condom use Knowledge on reproductive health |

| Comparison Group 2: Financial Incentive vs. No Intervention | ||||||||

| 1 | Kranzer 2018 [68] | Zimbabwe; primary health center | RCT | Children and adolescents 8–17 years | Intervention Group 1—USD 2: 654 Intervention Group 2—Fixed incentive or lottery: 562 Control group: 472 Total:1688 | Financial incentive for HIV testing and counseling | No incentive | Uptake of HIV testing |

| Comparison Group 3: Comprehensive School Support vs. No Intervention | ||||||||

| 1 | Hallfors 2011 [67] | Zimbabwe; school setting | RCT | Orphan girls aged 10–16 years | Intervention: 184 Control: 145 Total: 329 | Comprehensive school support (universal daily feeding program + provision of fees, uniforms, school supplies, helper) | Universal daily feeding program | HIV risk school dropout, marriage and pregnancy |

| 2 | Cho 2011 [65] | Kenya; school setting | RCT | Adolescent orphans aged 12–14 years | Intervention: 53 Control: 52 Total: 105 | Comprehensive School Support Program to prevent HIV (school uniform, tuition fees and a community visitor) and household support (mosquito nets and food supplements) | Received household support only (mosquito nets and food supplements) | School dropout, sexual debut and gender equity |

| 3 | Hallfors, 2017 [66] | Kenya; school setting | RCT | Adolescents orphans in grades 7 and 8 | Intervention: 412 Control: 425 Total: 837 | Comprehensive school support as an HIV prevention strategy (school uniform, tuition fees and) | No intervention | HIV/HSV2 prevention |

| Comparison Group 4: Comprehensive Post Abortion Family Planning Services vs. Standard Intervention | ||||||||

| 1 | Zhu 2009 [78] | China; hospital setting—abortion clinics | RCT | Young women aged 15–24 years | Intervention: 592 Control: 555 Total: 1147 | Comprehensive post abortion family planning services: (i) training of abortion service providers, provision of service guidelines as per standard training schedule and module (two days) (ii) group education (iii) individual counseling of women on contraceptive methods (iv) free provision of contraceptives (v) male involvement in group and individual counseling (vi) referral of women to existing FP services | Standard post abortion family planning services (i) training of abortion services providers and provision of service guidelines as per standard training schedule and module (one day) (ii) group education and (iii) referral of women to FP services | Use of contraceptive methods, rate of pregnancy, unwanted pregnancy, and induced abortion |

| Comparison Group 4: Provision of Menstrual Products vs. Standard Intervention | ||||||||

| 1. | Phillips-Howard 2016 [69] | Western Kenya; school setting | RCT | Primary-school girls 14–16 years, 3 menses | Intervention: 444 Control: 200 Total: 644 | Puberty and hygiene training, provision of menstrual cups, sanitary pads, and hand washing soap | Continued usual practice + provision of pubertal education and hand washing soap | STI, RTI, school dropout, adverse events (e.g., toxic shock etc.) |

| Outcomes | No of Studies; and Participants | Risk Ratio/Mean Difference (95% CI) | Heterogeneity Chi2 p Value; I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention 1: SRHR Information vs. No Information/Standard Intervention | |||

| Knowledge of Reproductive Health: HIV, STI, Pregnancy, Emergency Contraception | 6; 20,437 | 1.16 (1.04, 1.29) | (p < 0.001); I2 = 94% |

| 5; 7526 | 1.17 (0.99, 1.38) | (p < 0.001); I2 = 92% |

| 2; 2396 | 1.10 (0.91, 1.33) | (p = 0.05); I2 = 66% |

| 1; 65 | 1.10 (0.96, 1.27) | Not applicable |

| 1; 3520 | 1.63 (1.55, 1.72) | Not applicable |

| 1; 6930 | 1.11 (0.94, 1.32) | (p < 0.001); I2 = 94% |

| Knowledge of Reproductive Health—Overall—End of Intervention | 8; 7328 | 0.80 (0.44, 1.16) | (p < 0.001); I2 = 98% |

| 1; 777 | 0.28 (0.14, 0.43) | Not applicable |

| 2; 2625 | 0.16 (−0.22, 0.55) | (p 0.02); I2 = 80% |

| 5; 3926 | 1.11 (0.54, 1.67) | (p < 0.001); I2 = 98% |

| Improved SRHR Behavior | 2; 1338 | 1.61 (0.89, 2.92) | (p < 0.001); I2 = 89% |

| 1; 421 | 1.66 (1.22, 2.27) | Not applicable |

| 1; 63 | 0.83 (0.60, 1.14) | Not applicable |

| 1; 421 | 1.69 (1.29, 2.21) | Not applicable |

| 1; 433 | 20.16 (2.83, 143.31) | Not applicable |

| Improved Attitude towards SRHR | 5; 9324 | 1.29 (1.13, 1.47) | (p < 0.001); I2 = 86% |

| 2; 1335 | 1.20 (1.03, 1.40) | (p = 0.03); I2 = 70% |

| 1; 1358 | 0.97 (0.71, 1.32) | (p = 0.34); I2 = 0% |

| 2; 1335 | 1.41 (1.12, 1.77) | (p = 0.02); I2 = 76% |

| 1; 682 | 1.95 (1.66, 2.30) | Not applicable |

| 1; 4614 | 1.12 (1.03, 1.23) | (p = 0.25); I2 = 24% |

| Overall attitude towards SRHR | 1; 556 | 16.70 (15.19, 18.21) | Not applicable |

| Any Violence | 4; 8051 | 1.10 (1.01, 1.19) | (p = 0.35); I2 = 9% |

| 3; 1995 | 1.06 (0.92, 1.20) | (p = 0.55); I2 = 0% |

| 3; 1995 | 1.03 (0.87, 1.23) | (p = 0.97); I2 = 0% |

| 2; 1179 | 0.65 (0.10, 4.46) | (p = 0.15); I2 = 52% |

| 1; 665 | 1.07 (0.90, 1.28) | (p = 0.63); I2 = 0% |

| 1; 2217 | 1.19 (0.79, 1.80) | (p = 0.01); I2 = 85% |

| Any contraceptive use | 11; 6235 | 1.02 (0.91, 1.15) | (p < 0.001); I2 = 83% |

| 2; 2514 | 0.90 (0.64, 1.26) | (p < 0.001); I2 = 92% |

| 1; 100 | 1.58 (1.27, 1.97) | Not applicable |

| 2; 1346 | 1.09 (0.74, 1.61) | (p < 0.001); I2 = 95% |

| 1; 270 | 0.41 (0.24, 0.72) | Not applicable |

| 1; 366 | 1.01 (0.90, 1.13) | Not applicable |

| 1; 1264 | 1.42 (1.13, 1.80) | Not applicable |

| 3; 375 | 0.98 (0.85, 1.13) | (p = 0.96); I2 = 0% |

| Condom use | 16; 31,371 | 1.28 (1.15, 1.43) | (p < 0.001); I2 = 87% |

| 4; 13,118 | 1.41 (1.11, 1.79) | (p < 0.001); I2 = 84% |

| 2; 1769 | 0.82 (0.59, 1.15) | (p = 0.08); I2 = 60% |

| 3; 5289 | 1.17 (0.92, 1.50) | (p < 0.001); I2 = 93% |

| 2; 2764 | 2.70 (0.37, 19.97) | (p < 0.0001); I2 = 96% |

| 1; 776 | 1.79 (1.11, 2.89) | (p < 0.009); I2 = 85% |

| 1; 433 | 10.37 (1.44, 74.77) | Not applicable |

| 3; 7222 | 1.26 (1.01, 1.56) | (p = 0.07); I2 = 46% |

| Attitude and practice towards condom Use (School-based Intervention) | 5; 3704 | 0.37 (0.17, 0.57) | (p < 0.001); I2 = 84% |

| 1; 50 | 1.36 (0.74, 1.98) | Not applicable |

| 2; 1896 | 0.22 (0.04, 0.40) | (p = 0.02); I2 = 74% |

| 2; 1222 | 0.79 (−0.36, 1.93) | (p = 0.0003); I2 = 92% |

| 1; 50 | 0.54 (−0.02, 1.11) | Not applicable |

| Prevalence of STI/HIV | 2, 4672 | 0.71 (0.62, 0.82) | (p = 0.55); I2 = 0% |

| 1; 1896 | 0.69 (0.59, 0.82) | Not applicable |

| 1; 2776 | 0.76 (0.58, 1.01) | Not applicable |

| Reported pregnancy among young women (Adolescents and youth) | 3; 6194 | 1.00 (0.92, 1.10) | 1.64 (1.29, 2.07) |

| 1; 381 | 0.57 (0.17, 1.93) | Not applicable |

| 1; 331 | 0.86 (0.27, 2.75) | Not applicable |

| 2; 5482 | 1.01 (0.92, 1.10) | (p = 0.44); I2 = 0% |

| Unprotected Sex | 2; 1326 | 0.75 (0.48, 1.19) | 0.44 (1.29, 2.07) |

| 1; 1022 | 0.50 (0.25, 1.01) | Not applicable |

| 1; 304 | 1.02 (0.56, 1.86) | (p = 0.44); I2 = 0% |

| Self-efficacy for safer sex | 1; 777 | 0.26 (0.19, 0.33) | 1.64 (1.29, 2.07) |

| Multiple sex partners | 9; 18,670 | 0.66 (0.48, 0.91) | 1.64 (1.29, 2.07) |

| 2; 9616 | 0.92 (0.64, 1.33) | (p < 0.001); I2 = 91% |

| 1; 777 | 1.24 (0.87, 1.78) | Not applicable |

| 4; 2746 | 0.59 (0.27, 1.30) | (p < 0.008); I2 = 71% |

| 1; 3666 | 0.90 (0.72, 1.11) | (p = 0.97); I2 = 0% |

| 1; 1865 | 0.02 (0.01, 0.05) | Not applicable |

| Number of multiple sexual partners | 1; 400 | −0.60 (−1.02, −0.18) | Not applicable |

| Uptake of ASRH Services | 5; 7851 | 1.45 (1.17, 1.80) | (p < 0.001); I2 = 91% |

| 2; 1441 | 1.64 (1.29, 2.07) | (p = 0.07); I2 = 53% |

| 2; 5146 | 1.00 (0.95, 1.06) | (p = 0.86); I2 = 0% |

| 1; 1264 | 3.64 (2.51, 5.27) | Not applicable |

| Prevalence of STI diseases | 2; 14,150 | 0.86 (0.75, 0.99) | (p < 0.001); I2 = 89% |

| 1; 1308 | 2.03 (0.62, 6.69) | (p = 0.97); I2 = 0% |

| 1; 1308 | 0.88 (0.43, 1.78) | (p = 0.90); I2 = 0% |

| 2; 3643 | 1.12 (0.79, 1.57) | (p = 0.94); I2 = 0% |

| 2; 3643 | 1.07 (0.88, 1.30) | (p = 0.69); I2 = 0% |

| 1; 1696 | 0.18 (0.13, 0.25) | Not applicable |

| 1; 2552 | 5.00 (2.44, 10.25) | (p = 0.05); I2 = 75% |

| Intervention 2: Financial Incentive vs. No Intervention | |||

| U of HIV testing services | 1; 1688 | 2.24 (1.84, 2.71) | (p = 0.37); I2 = 0% |

| 1; 890 | 2.43 (1.86, 3.17) | Not applicable |

| 1; 798 | 2.04 (1.54, 2.69) | Not applicable |

| Intervention 3: Comprehensive School Support vs. No Intervention | |||

| Rates of teenage pregnancy | 1; 329 | 0.16 (0.01, 3.26) | Not applicable |

| Intervention 4: Comprehensive Post Abortion Family Planning Services vs. Standard Intervention | |||

| Use of family planning methods | 1; 937 | 1.16 (1.09, 1.24) | (p < 0.001); I2 = 99% |

| 1; 500 | 1.01 (0.98, 1.03) | Not applicable |

| 1; 437 | 1.97 (1.45, 2.66) | Not applicable |

| Compliance of contraceptives | 1; 83 | 1.23 (0.93, 1.64) | Not applicable |

| Rate of unwanted pregnancies | 1; 1147 | 0.33 (0.15, 0.72) | Not applicable |

| Induces abortion | 1; 1147 | 0.36 (0.15, 0.87) | Not applicable |

| Intervention 5: Provision of Menstrual Products vs. No Intervention | |||

| Rates of STIs and RTIs | 1; 384 | 0.79 (0.34, 1.79) | (p = 0.18); I2 = 44% |

| 1; 174 | 0.43 (0.13, 1.41) | Not applicable |

| 1; 174 | 1.05 (0.60, 1.83) | Not applicable |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meherali, S.; Rehmani, M.; Ali, S.; Lassi, Z.S. Interventions and Strategies to Improve Sexual and Reproductive Health Outcomes among Adolescents Living in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adolescents 2021, 1, 363-390. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents1030028

Meherali S, Rehmani M, Ali S, Lassi ZS. Interventions and Strategies to Improve Sexual and Reproductive Health Outcomes among Adolescents Living in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adolescents. 2021; 1(3):363-390. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents1030028

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeherali, Salima, Mehnaz Rehmani, Sonam Ali, and Zohra S. Lassi. 2021. "Interventions and Strategies to Improve Sexual and Reproductive Health Outcomes among Adolescents Living in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Adolescents 1, no. 3: 363-390. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents1030028

APA StyleMeherali, S., Rehmani, M., Ali, S., & Lassi, Z. S. (2021). Interventions and Strategies to Improve Sexual and Reproductive Health Outcomes among Adolescents Living in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adolescents, 1(3), 363-390. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents1030028