Enhancing Nonylphenol Biodegradation: The Role of Acetyl-CoA C-Acetyltransferase in Bacillus cereus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals, Strains, and Growth Conditions

2.2. Construction of the Bacillus cereus atoB Overexpression Vector

2.3. Quantification of AtoB by ELISA

2.4. Biodegradation of NP

2.5. Detection of NP by HPLC

2.6. Measurement of ATP Content in Bacillus cereus

2.7. Lipid Metabolome Detection

2.8. Lipid Qualitative and Quantitative Analyses

2.9. ELISA Validation of Differential Lipids

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. PCR Identification of atoB Overexpression in Bacillus cereus LY

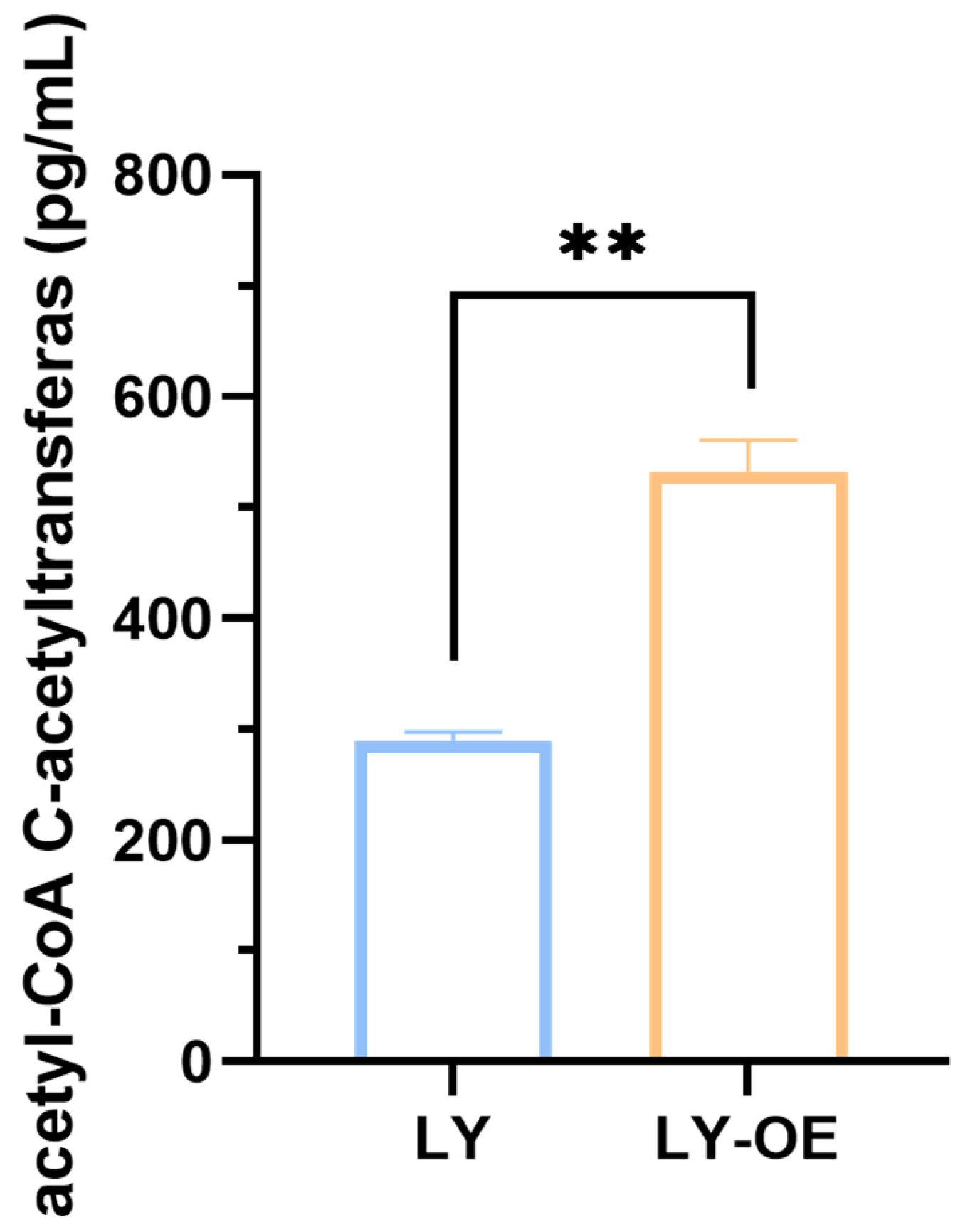

3.2. Acetyl-CoA C-Acetyltransferase Concentrations

3.3. Overexpression of the atoB Gene in Bacillus cereus Enhances Its Degradation Rate of NP

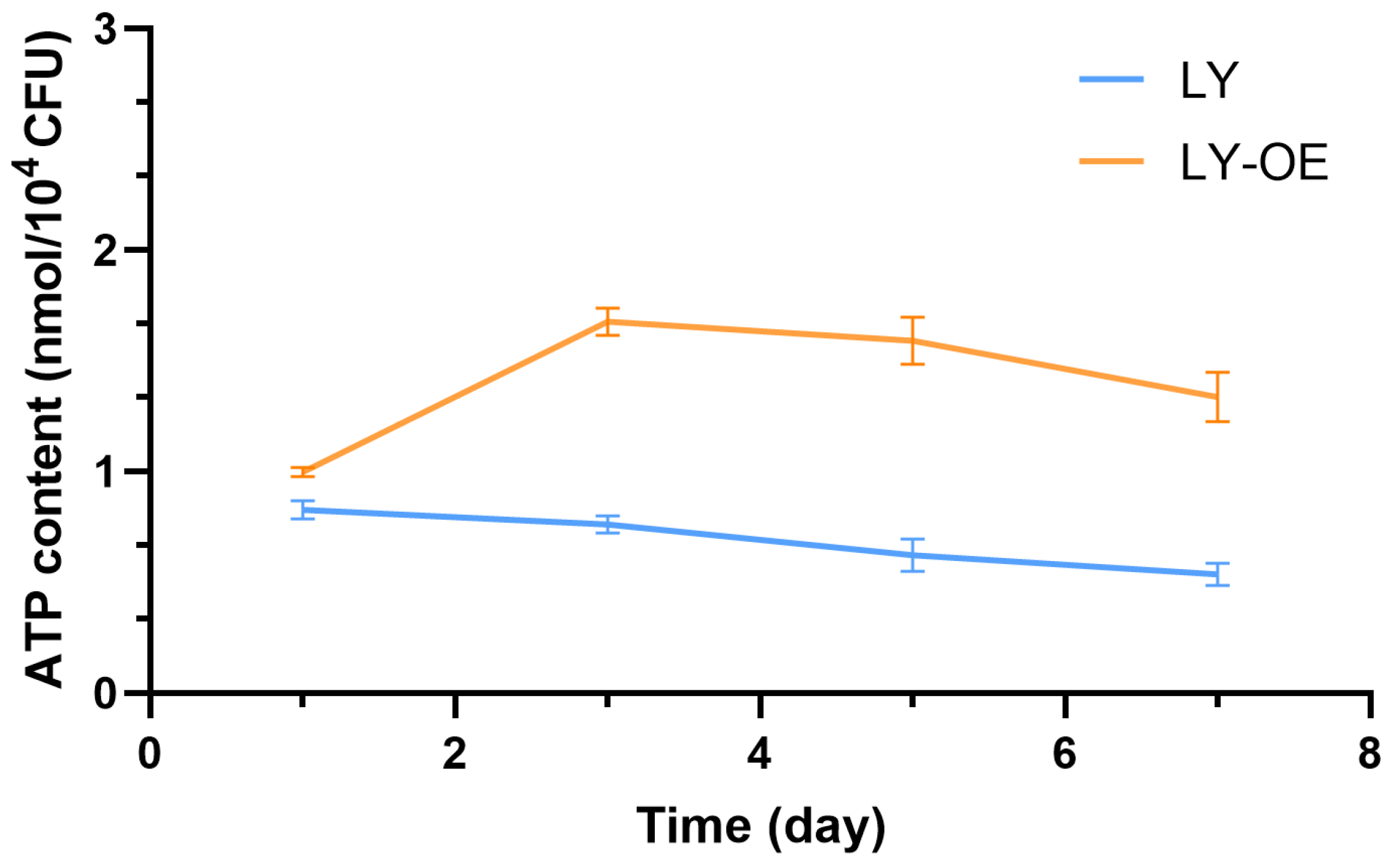

3.4. ATP Content in Bacillus cereus During NP Degradation

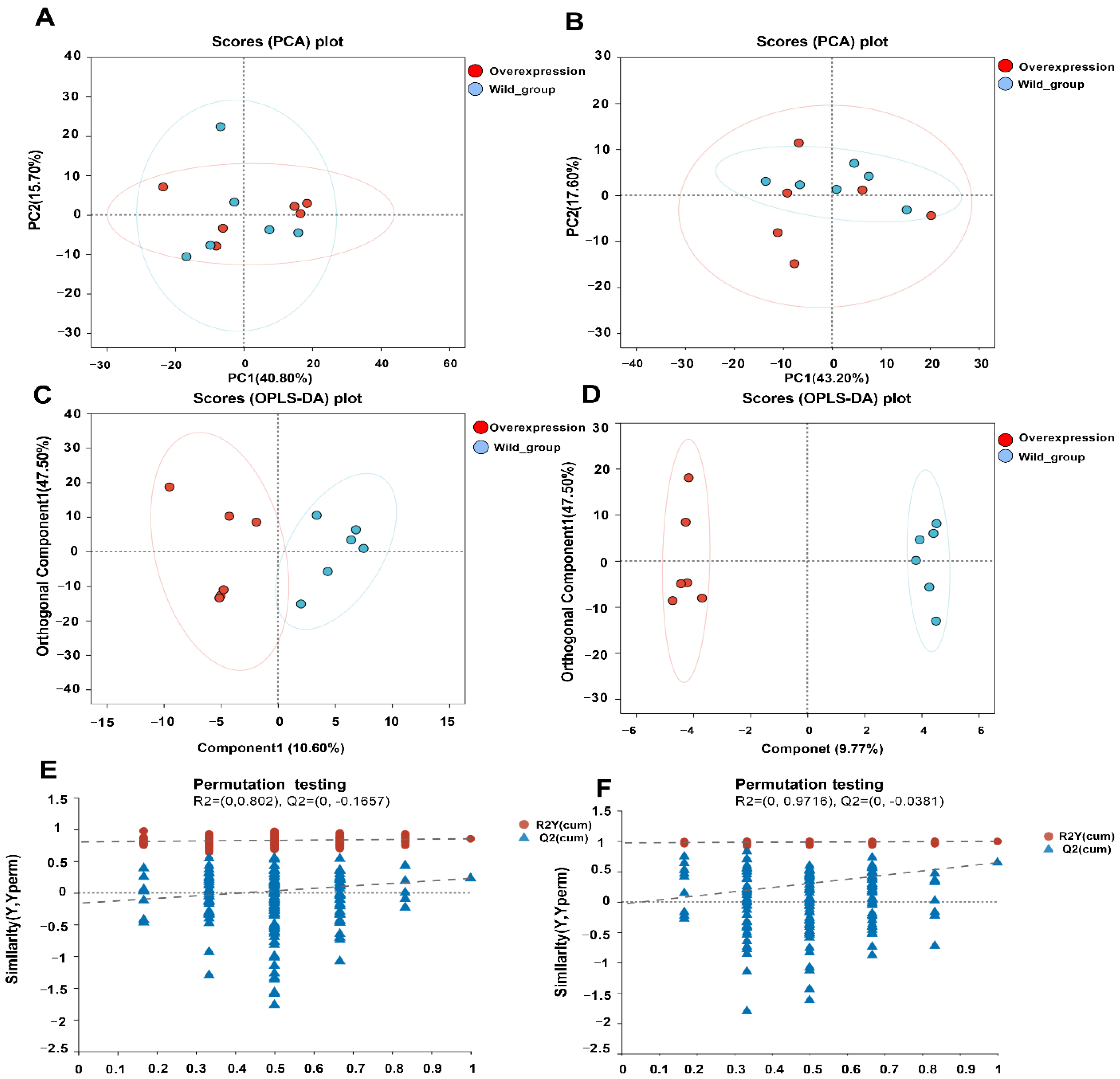

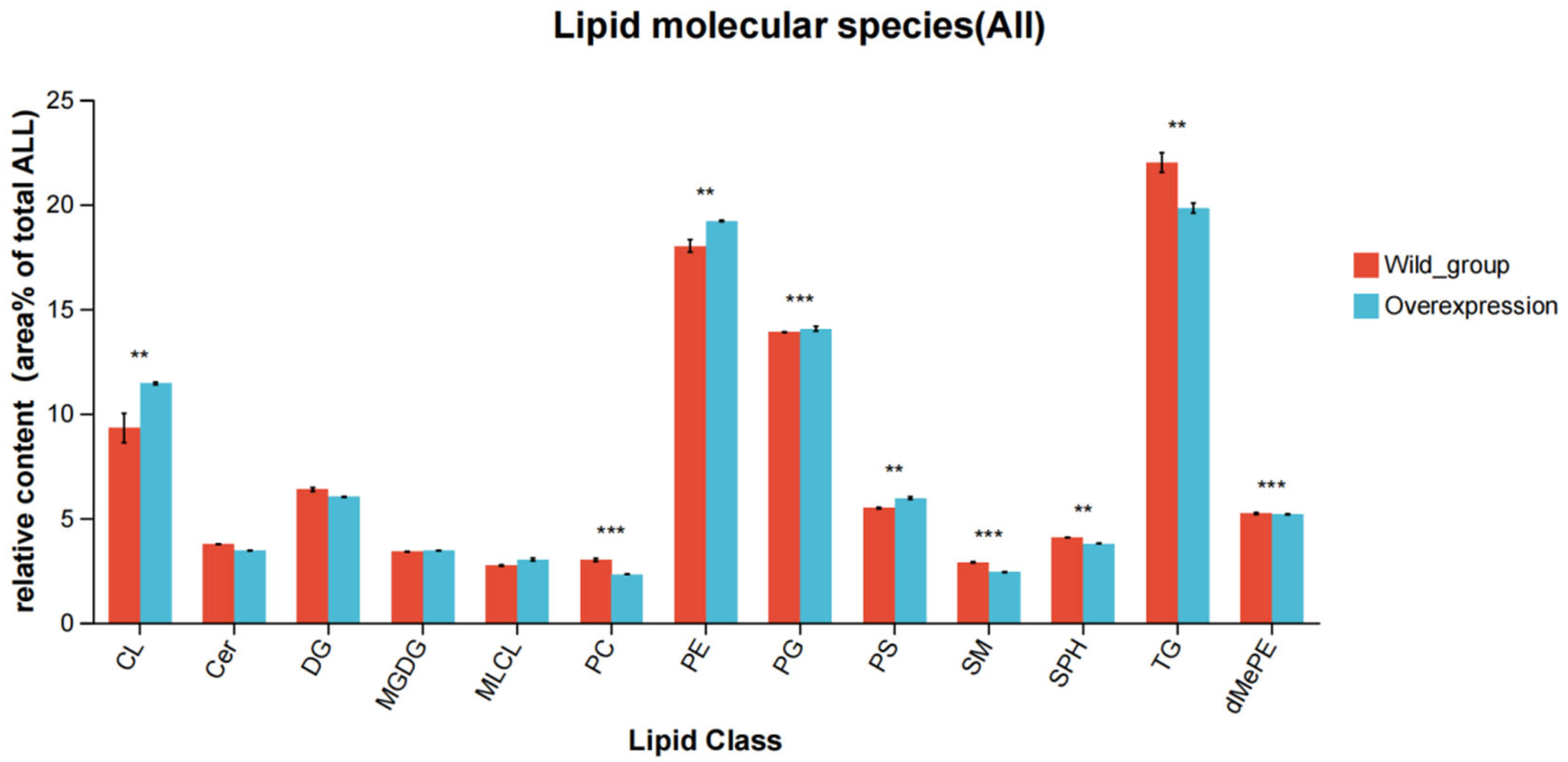

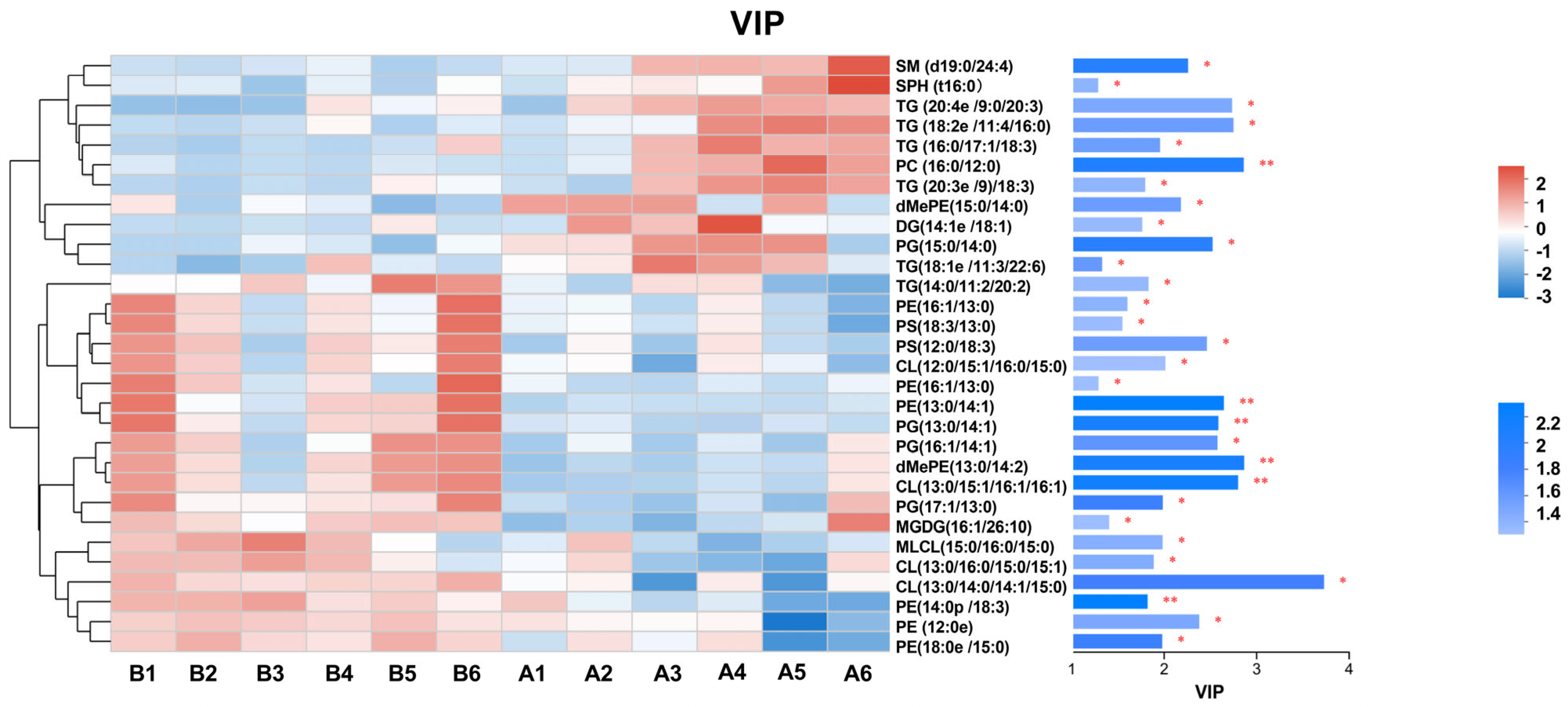

3.5. Lipid Metabolomics Analysis

3.6. ELISA Validation Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Araujo, F.G.; Bauerfeldt, G.F.; Cid, Y.P. Nonylphenol: Properties, legislation, toxicity and determination. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2018, 90, 1903–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandstaetter, C.; Fricko, N.; Rahimi, M.J.; Fellner, J.; Ecker-Lala, W.; Druzhinina, I.S. The microbial metabolic activity on carbohydrates and polymers impact the biodegradability of landfilled solid waste. Biodegradation 2022, 33, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.Y.; Wu, C.Y.; Wang, C.H.; Ding, W.H. Determination and distribution characteristics of degradation products of nonylphenol polyethoxylates in the rivers of Taiwan. Chemosphere 2006, 65, 2275–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.J.; Feng, C.L.; Xu, D.Y.; Wu, F.C. Comprehensive Review on Environmental Biogeochemistry of Nonylphenol and Suggestions for the Management of Emerging Contaminants. Huan Jing Ke Xue 2023, 44, 4717–4727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Yang, L.; Yi, R.; Yu, H.; Zhang, J.; Nawaz, M.I. Degradation of the nonylphenol aqueous solution by strong ionization discharge: Evaluation of degradation mechanism and the water toxicity of zebrafish. Water Sci. Technol. 2022, 86, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milla, S.; Depiereux, S.; Kestemont, P. The effects of estrogenic and androgenic endocrine disruptors on the immune system of fish: A review. Ecotoxicology 2011, 20, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.A. The immune system as a potential target for environmental estrogens (endocrine disrupters): A new emerging field. Toxicology 2000, 150, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, J.A.; Metz, L.; Yong, V.W. Review: Endocrine disrupting chemicals and immune responses: A focus on bisphenol-A and its potential mechanisms. Mol. Immunol. 2013, 53, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, P.A.; Khatami, M.; Baglole, C.J.; Sun, J.; Harris, S.A.; Moon, E.-Y.; Al-Mulla, F.; Al-Temaimi, R.; Brown, D.G.; Colacci, A.M.; et al. Environmental immune disruptors, inflammation and cancer risk. Carcinogenesis 2015, 36, S232–S253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, B.; Qin, J.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Sun, H.; Chen, W. Adsorption of Phenol on Commercial Activated Carbons: Modelling and Interpretation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuramitz, H.; Saitoh, J.; Hattori, T.; Tanaka, S. Electrochemical removal of p-nonylphenol from dilute solutions using a carbon fiber anode. Water Res. 2002, 36, 3323–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, A.; Guieysse, B.; Jefferson, B.; Cartmell, E.; Lester, J.N. Nonylphenol in the environment: A critical review on occurrence, fate, toxicity and treatment in wastewaters. Environ. Int. 2008, 34, 1033–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanghe, T.; Dhooge, W.; Verstraete, W. Isolation of a bacterial strain able to degrade branched nonylphenol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 746–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, K.; Urano, N.; Ushio, H.; Satomi, M.; Kimura, S. Sphingomonas cloacae sp. nov., a nonylphenol-degrading bacterium isolated from wastewater of a sewage-treatment plant in Tokyo. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2001, 51, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, F.L.P.; Giger, W.; Guenther, K.; Kohler, H.P.E. Differential degradation of nonylphenol isomers by Sphingomonas xenophaga Bayram. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 1123–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corvini, P.F.X.; Schäffer, A.; Schlosser, D. Microbial degradation of nonylphenol and other alkylphenols—Our evolving view. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 72, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.; Murto, M.; Guieysse, B.; Mattiasson, B. Biodegradation of nonylphenol in a continuous bioreactor at low temperatures and effects on the microbial population. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 69, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.T.; Wong, Y.S.; Tam, N.F. Removal and biodegradation of nonylphenol by different Chlorella species. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 63, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Sun, W.; Dai, Y.; Xie, S. Variation of nonylphenol-degrading gene abundance and bacterial community structure in bioaugmented sediment microcosm. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 2342–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeo, M.; Akizuki, J.; Kawasaki, A.; Negoro, S. Degradation potential of the nonylphenol monooxygenase of Sphingomonas sp. NP5 for bisphenols and their structural analogs. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaghabee, F.M.F.; Rokana, N.; Gulhane, R.D.; Sharma, C.; Panwar, H. Bacillus as Potential Probiotics: Status, Concerns, and Future Perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, R.; Ueda, K.; Kitano, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Mizutani, Y.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Imoto, K.; Yamamori, Y. Fatal community-acquired Bacillus cereus pneumonia in an immunocompetent adult man: A case report. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Chandra, R. Biodegradation and toxicity reduction of pulp paper mill wastewater by isolated laccase producing Bacillus cereus AKRC03. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2021, 4, 100193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felshia, S.C.; Karthick, N.A.; Thilagam, R.; Chandralekha, A.; Raghavarao, K.S.M.S.; Gnanamani, A. Efficacy of free and encapsulated Bacillus lichenformis strain SL10 on degradation of phenol: A comparative study of degradation kinetics. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 197, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurihara, T.; Ueda, M.; Kamasawa, N.; Osumi, M.; Tanaka, A. Physiological roles of acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase in n-alkane-utilizable yeast, Candida tropicalis: Possible contribution to alkane degradation and sterol biosynthesis. J. Biochem. 1992, 112, 845–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, Y.; Ishigami, K.; Hassaninasab, A.; Kishi, K.; Kumano, T.; Kobayashi, M. Curcumin degradation in a soil microorganism: Screening and characterization of a β-diketone hydrolase. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 107647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Liu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Li, H.; Ye, M.; Pan, H.; Zhu, J.; Song, H. The conversion of the nutrient condition alter the phenol degradation pathway by Rhodococcus biphenylivorans B403: A comparative transcriptomic and proteomic approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 56152–56163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisboa, N.S.; Fahning, C.S.; Cotrim, G.; dos Anjos, J.P.; de Andrade, J.B.; Hatje, V.; da Rocha, G.O. A simple and sensitive UFLC-fluorescence method for endocrine disrupters determination in marine waters. Talanta 2013, 117, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Xie, Y.; Xu, S.; Lv, X.; Yin, H.; Xiang, J.; Chen, H.; Wei, F. Comprehensive Lipidomics Analysis Reveals the Effects of Different Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid-Rich Diets on Egg Yolk Lipids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 15048–15060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunill, J.; Babot, C.; Santos, L.; Serrano, J.C.E.; Jové, M.; Martin-Garí, M.; Portero-Otín, M. In Vivo Anti-Inflammatory Effects and Related Mechanisms of Processed Egg Yolk, a Potential Anti-Inflammaging Dietary Supplement. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, Q.; Kang, S.; Cao, X.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, J.; Wu, R.; Shao, J.; Yang, M.; Yue, X. Characterization and comparison of lipids in bovine colostrum and mature milk based on UHPLC-QTOF-MS lipidomics. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S.; Zoong-Lwe, Z.S.; Gandhi, N.; Welti, R.; Fallen, B.; Smith, J.R.; Rustgi, S. Comparative Lipidomic Analysis Reveals Heat Stress Responses of Two Soybean Genotypes Differing in Temperature Sensitivity. Plants 2020, 9, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, W.; Shi, R.; Kang, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, P.; Zhang, L.; Hou, A.; Wang, R.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, K.; et al. Monoacylglycerol lipase regulates cannabinoid receptor 2-dependent macrophage activation and cancer progression. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tang, Q.; Li, Y.; Fan, Y.Y.; Li, F.H.; Wu, J.H.; Min, D.; Li, W.W.; Lam, P.K.S.; Yu, H.Q. Rediverting Electron Flux with an Engineered CRISPR-ddAsCpf1 System to Enhance the Pollutant Degradation Capacity of Shewanella oneidensis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 3599–3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, N.K.; Sondhi, S. Cloning, expression and characterization of laccase from Bacillus licheniformis NS2324 in E. coli application in dye decolorization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 206, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, D.; Ranjan, B.; Mchunu, N.; Le Roes-Hill, M.; Kudanga, T. Enhancing the expression of recombinant small laccase in Pichia pastoris by a double promoter system and application in antibiotics degradation. Folia Microbiol. 2021, 66, 917–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, R.; Guo, J.; Yang, C.; Zhu, D.; Li, T.; Yang, W.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Huang, S.; Wang, H.; et al. Enhanced chemotaxis and degradation of nonylphenol in Pseudoxanthomonas mexicana via CRISPR-mediated receptor modification. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romantsov, T.; Guan, Z.; Wood, J.M. Cardiolipin and the osmotic stress responses of bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Biomembr. 2009, 1788, 2092–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carney, O.S.; Harris, K.; Santizo, M.; Silva, V.; Davis, J.; Lee, K.; Vishwanath, S.; Hamacher-Brady, A.; Vernon, H.J. A review of disorders of cardiolipin metabolism: Pathophysiology, clinical presentation and future directions. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2025, 145, 109184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E.E. Membrane Lipids: What Membrane Physical Properties are Conserve during Physiochemically-Induced Membrane Restructuring? Am. Zool. 1998, 38, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernomordik, L. Non-bilayer lipids and biological fusion intermediates. Chem. Phys. Lipids 1996, 81, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sendecki, A.M.; Poyton, M.F.; Baxter, A.J.; Yang, T.; Cremer, P.S. Supported Lipid Bilayers with Phosphatidylethanolamine as the Major Component. Langmuir 2017, 33, 13423–13429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murzyn, K.; Róg, T.; Pasenkiewicz-Gierula, M. Phosphatidylethanolamine-phosphatidylglycerol bilayer as a model of the inner bacterial membrane. Biophys. J. 2005, 88, 1091–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.G. How lipids affect the activities of integral membrane proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Biomembr. 2004, 1666, 62–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.G. Lipid-protein interactions in biological membranes: A structural perspective. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Biomembr. 2003, 1612, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, M.; Dowhan, W. Phosphatidylethanolamine is required for in vivo function of the membrane-associated lactose permease of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Diaz, L.; Caballero, A.; Segura, A. Pathways for the Degradation of Fatty Acids in Bacteria. In Aerobic Utilization of Hydrocarbons, Oils and Lipids; Handbook of Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology; Rojo, F.F., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Fang, X.; Yang, R.; Yu, H.; Jiang, P.; Sun, B.; Zhao, Z. MiR-152 Regulates Apoptosis and Triglyceride Production in MECs via Targeting ACAA2 and HSD17B12 Genes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primer Name | Sequence Information |

|---|---|

| atoB-pHT01-F | TTAAAGGAGGAAGGATCCATGAATAGAGCAGTCATTGTAG |

| atoB-pHT01-R | GTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTCTTCTATTTTCTCAAATAAT |

| pHT01-atoB-F | CACCACCACCACCACTAGCAGCCCGCCTAATGAGCGGGCTT |

| pHT01-atoB-R | ATGACTGCTCTATTCATGGGATCCTTCCTCCTTTAATTGGGG |

| pHT01-JD-F | CCGGAATTAGCTTGGGTACCAGCT |

| pHT01-JD-R | AACCATTTGTTCCAGGTAAGG |

| Metabolites | Classification | Molecular Formula | VIP | P | FC | Trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPH (t16:0) | SP | C16H36O3N1 | 1.2863 | 0.0385 | 0.9719 | ↓ |

| Cer (t16:1/17:0) | SP | C33H66O4N1 | 1.1613 | 0.0378 | 0.9610 | ↓ |

| SM (d19:0/24:4) | SP | C48H92O6N2P1 | 2.2581 | 0.0108 | 0.8757 | ↓ |

| dMePE (15:0/14:0) | GP | C36H71O8N1P1 | 2.1811 | 0.0265 | 0.8456 | ↓ |

| dMePE (13:0/14:2) | GP | C34H63O8N1P1 | 2.8655 | 0.0088 | 1.3143 | ↑ |

| PE (16:1/13:0) | GP | C34H65O8N1P1 | 1.6028 | 0.0377 | 1.0674 | ↑ |

| PE (13:0/14:1) | GP | C32H61O8N1P1 | 2.6455 | 0.0061 | 1.2369 | ↑ |

| PE (18:0e/15:0) | GP | C38H78O7N1P1K1 | 1.9791 | 0.0148 | 1.0931 | ↑ |

| PE (16:1/14:3) | GP | C35H62O8N1P1Na1 | 1.2907 | 0.0463 | 1.1681 | ↑ |

| PE (12:0e/18:1) | GP | C35H71O7N1P1 | 2.3793 | 0.0315 | 1.1171 | ↑ |

| PE (14:0p/18:3) | GP | C37H69O7N1P1 | 1.8208 | 0.0058 | 1.0704 | ↑ |

| PS (18:3/13:0) | GP | C37H65O10N1P1 | 1.5490 | 0.0445 | 1.0717 | ↑ |

| PS (12:0/18:3) | GP | C36H63O10N1P1 | 2.4624 | 0.0270 | 1.2339 | ↑ |

| MLCL (15:0/16:0/15:0) | GP | C55H107O16P2 | 1.9832 | 0.0360 | 1.1546 | ↑ |

| CL (12:0/15:1/16:0/15:0) | GP | C67H126O17P2 | 2.0132 | 0.0471 | 1.1443 | ↑ |

| CL (13:0/14:0/14:1/15:0) | GP | C65H122O17P2 | 3.7290 | 0.0168 | 1.8013 | ↑ |

| CL (13:0/15:1/16:1/16:1) | GP | C69H126O17P2 | 2.7992 | 0.0075 | 1.3056 | ↑ |

| CL (13:0/16:0/15:0/15:1) | GP | C68H129O17P2 | 1.8872 | 0.0338 | 1.1319 | ↑ |

| PC (16:0/12:0) | GP | C36H73O8N1P1 | 2.8606 | 0.0099 | 0.8072 | ↓ |

| PG (16:1/14:1) | GP | C36H66O10N0P1 | 2.5766 | 0.0231 | 1.2690 | ↑ |

| PG (13:0/13:0) | GP | C32H62O10N0P1 | 1.1192 | 0.0439 | 0.9572 | ↓ |

| PG (13:0/14:1) | GP | C33H62O10N0P1 | 2.5864 | 0.0084 | 1.2704 | ↑ |

| PG (17:1/13:0) | GP | C36H68O10N0P1 | 1.9851 | 0.0154 | 1.1062 | ↑ |

| PG (15:0/14:0) | GP | C35H69O10N0P1Na1 | 2.5239 | 0.0118 | 0.8481 | ↓ |

| MGDG (16:1/26:10) | GL | C52H77O12 | 1.4053 | 0.0455 | 1.0631 | ↑ |

| DG (16:1/13:0) | GL | C39H71O12 | 1.2476 | 0.0279 | 1.0932 | ↑ |

| DG (14:1e/18:1) | GL | C35H66O4Na1 | 1.7631 | 0.0426 | 0.8625 | ↓ |

| TG (20:4e/9:0/20:3) | GL | C58H104O5N2 | 2.7350 | 0.0317 | 0.8371 | ↓ |

| TG (20:3e/9:0/18:3) | GL | C56H102O5N2 | 1.7953 | 0.0396 | 0.9233 | ↓ |

| TG (9:0/9:0/9:0) | GL | C36H72O6N2 | 1.2217 | 0.0050 | 1.0577 | ↑ |

| TG (16:0/17:1/18:3) | GL | C54H96O6Li1 | 1.9556 | 0.0268 | 0.9232 | ↓ |

| TG (14:0/11:2/20:2) | GL | C54H100O6N2 | 1.8311 | 0.0417 | 1.1041 | ↑ |

| TG (18:2e/11:4/16:0) | GL | C54H98O5N2 | 2.7491 | 0.0266 | 0.8564 | ↓ |

| TG (18:1e/11:3/22:6) | GL | C60H102O5N2 | 1.3292 | 0.0250 | 0.9286 | ↓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, F.; Luo, D.; Yang, L.; Dong, R. Enhancing Nonylphenol Biodegradation: The Role of Acetyl-CoA C-Acetyltransferase in Bacillus cereus. BioTech 2025, 14, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/biotech14040099

Lu F, Luo D, Yang L, Dong R. Enhancing Nonylphenol Biodegradation: The Role of Acetyl-CoA C-Acetyltransferase in Bacillus cereus. BioTech. 2025; 14(4):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/biotech14040099

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Fanglian, Deqin Luo, Lian Yang, and Ranran Dong. 2025. "Enhancing Nonylphenol Biodegradation: The Role of Acetyl-CoA C-Acetyltransferase in Bacillus cereus" BioTech 14, no. 4: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/biotech14040099

APA StyleLu, F., Luo, D., Yang, L., & Dong, R. (2025). Enhancing Nonylphenol Biodegradation: The Role of Acetyl-CoA C-Acetyltransferase in Bacillus cereus. BioTech, 14(4), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/biotech14040099