Abstract

Background/Objectives: Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a severe drug-induced cutaneous reaction characterized by the abrupt onset of sterile pustules, fever, neutrophilia, and a T cell-mediated type IVd hypersensitivity response. This narrative review synthesizes current evidence on pharmacological triggers, immunopathogenic mechanisms, diagnostic criteria, and differential diagnosis to provide a clinically oriented framework. Methods: A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, ScienceDirect, and SpringerLink for studies published between 2000 and 2025, complemented by selected clinical reference sources. Studies addressing clinical features, immunological pathways, pharmacovigilance signals, and diagnostic tools for AGEP were included. Synthesis of Evidence: β-lactam antibiotics remain the most frequent triggers, while increasing associations have been reported with hydroxychloroquine, targeted therapies, immune checkpoint inhibitors, psychotropic agents, and vaccines. Immunopathogenesis is driven by IL-36 activation, CXCL8/IL-8–mediated neutrophil recruitment, and IL36RN mutations, explaining overlap with pustular psoriasis. Diagnostic accuracy improves through integration of drug latency, clinical morphology, histopathology, biomarkers, and standardized tools such as the EuroSCAR score. Conclusions: AGEP is a complex pustular reaction induced by diverse drugs and amplified by IL-36-mediated inflammation. Accurate diagnosis requires a multidimensional approach supported by structured algorithms and robust pharmacovigilance to identify evolving drug-associated patterns.

1. Introduction

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a severe, immune-mediated, rapidly onset cutaneous reaction, characterized by the abrupt appearance of non-follicular sterile pustules on a diffuse erythematous base, accompanied by neutrophilia, variable eosinophilia, and mild to moderate systemic symptoms [1,2]. It corresponds to a form of type IV hypersensitivity mediated by T cells, whose inflammatory response is dominated by the activation of interleukin (IL)-36-dependent pathways, which are determinants both in pustule formation and in the intensity of cutaneous inflammation [3].

The estimated incidence of AGEP ranges from 1 to 5 cases per million inhabitants per year, generally with a favorable course and a mortality rate below 5%. It mainly affects adults, with a predominance in women [4]. Around 90% of cases are drug-induced, with antibiotics being the group historically most implicated; their characteristic latency of 24–48 h facilitates diagnostic orientation and allows them to be distinguished from cases associated with biologic therapies, immunotherapies, or kinase inhibitors, which show a slower, more prolonged, and clinically misleading onset [1,2,3,4].

In recent years, AGEP has become an increasing diagnostic challenge in dermatologic practice. The expansion of polypharmacy, the introduction of new-generation immunomodulatory treatments, and the intensive use of medications during the COVID-19 pandemic have considerably broadened the spectrum of drugs capable of triggering it. Additionally, there is frequent clinical and histological overlap with other acute pustular dermatoses, especially generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP), drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms/drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DRESS/DIHS), and severe reactions such as Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN), which complicates early differential diagnosis [1,2,3,4,5].

In this context, it is essential to systematically integrate clinical criteria, histopathological evaluation, and the support of pharmacovigilance tools to improve diagnostic accuracy and avoid errors in the identification of acute pustular reactions. A central element within this approach is the EuroSCAR score, a validated system that combines morphology, clinical course, and histologic findings, whose usefulness has been repeatedly demonstrated in clinical studies [4,5,6].

Given the dispersion of clinical reports, the heterogeneity of the drugs involved, and the growing complexity of the differential diagnosis, a comprehensive and unified review is needed that integrates the pharmacology, immunological mechanisms, diagnostic criteria, and tools for the clinical differentiation of AGEP from other pustular eruptions, in order to provide clinicians with a clear, practical approach aligned with the most recent evidence.

2. Methods

This study corresponds to a narrative review whose purpose is to provide a comprehensive, updated, and clinically applicable overview of the available evidence on AGEP.

2.1. Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, ScienceDirect, and SpringerLink. Publications in English or Spanish from 2000 to 2025 were considered. The search strategy combined MeSH terms and free-text keywords related to “acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis,” “AGEP,” “drug-induced pustulosis,” “severe cutaneous adverse reactions,” “interleukin-36,” “IL-36,” “pharmacovigilance,” and the generic names of the medications most frequently implicated. The complete database-specific search equations and applied filters are detailed in Appendix A (Table A1).

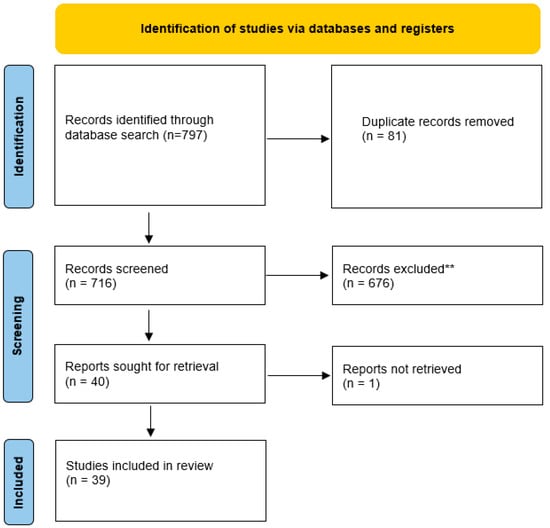

The initial search retrieved 797 records. After removing 81 duplicates, 716 records were screened by title and abstract. Of these, 676 were excluded for not meeting the predefined eligibility criteria. Full-text retrieval was attempted for 40 reports, though one could not be accessed. In total, 39 studies met the inclusion criteria and were incorporated into the qualitative synthesis. The selection process is illustrated in the corresponding flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study selection process.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

For this review, studies conducted in adult populations (≥18 years) with a clinical or histological diagnosis of AGEP were included. Eligible designs encompassed observational studies, case series, clinical trials, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, consensus statements, and high-level narrative reviews. Publications addressing relevant aspects of the condition, including pathophysiology, pharmacology, genetic involvement, latencies, differential diagnosis, diagnostic tools, and associated pharmacovigilance, were also incorporated. Only articles in English or Spanish published between 2000 and 2025 were accepted.

Case reports without diagnostic confirmation of AGEP, letters to the editor lacking clinical information, editorials, and commentaries were excluded. Studies conducted exclusively in vitro or in animal models without clinical correlation were also discarded, as were investigations focused on pediatric populations or on cutaneous reactions not induced by medications.

2.3. Drug Selection

A comprehensive review was conducted to identify the pharmacological classes most commonly associated with AGEP according to the literature, regulatory databases, and pharmacovigilance systems such as the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) and EudraVigilance. Based on this assessment, the main categories considered were antibiotics (β-lactams, macrolides, and lincosamides), antimalarials such as hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), targeted therapies and immunotherapies (Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) inhibitors, tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI), and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI), psychotropic drugs such as typical and atypical antipsychotics, and vaccines based on mRNA or viral vectors. For each therapeutic class, priority was given to drugs with the highest number of reported cases, well-documented immunological mechanisms, or evidence of an emerging risk in pharmacovigilance.

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

For each study and drug identified as potentially implicated in AGEP, the following variables were extracted: population characteristics, type of pharmacological exposure, reported latency, clinical and systemic manifestations, histopathological findings, applied diagnostic criteria (including EuroSCAR), recurrence, severity, therapeutic management, and outcomes. In cases where pharmacovigilance was mentioned, safety signals, reported frequencies, and data derived from global databases (FAERS, EudraVigilance) were also documented.

The collected information was synthesized narratively and organized by pharmacological classes, implicated immunological mechanisms, and differential characteristics. In parallel, the findings were integrated into comparative tables and diagnostic diagrams to generate a structured proposal that facilitates clinical interpretation and a uniform approach to AGEP in dermatological practice. The clinical and pharmacological examples presented are illustrative and do not represent an exhaustive list of all reported AGEP triggers, but rather those most consistently documented or clinically relevant.

2.5. Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence

In this study, ChatGPT (GPT-5, OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) was used exclusively as a support tool for text editing, improving clarity and coherence, standardizing terminology, and generating preliminary conceptual graphic schemes; it did not participate in data extraction, analysis, clinical interpretation, or the development of conclusions. All generated content was subsequently critically reviewed, verified with the sources, and adjusted by the authors.

3. Clinical and Pathophysiological Overview

3.1. Immunopathogenesis

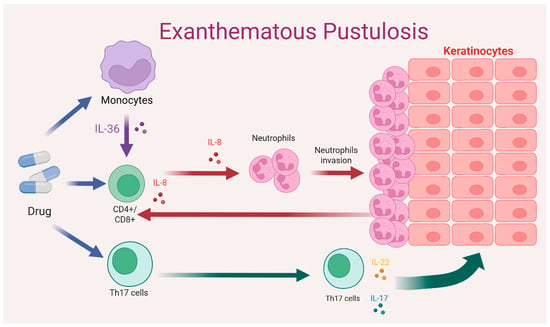

AGEP is a severe cutaneous reaction primarily triggered by medications and mediated by drug-specific T lymphocytes, whose central role is to induce a robust neutrophilic inflammatory response. After exposure to the offending drug, activated T cells release chemotactic cytokines, particularly IL 8, that promote the migration and accumulation of neutrophils within the epidermis, giving rise to the sterile pustules characteristic of the disease. Keratinocytes play a central role in this process, as they are a major source of IL-8 (CXCL8) in response to T cell–derived cytokines, thereby establishing a chemotactic gradient that drives neutrophil recruitment into the epidermis and promotes pustule formation. From an immunological perspective, AGEP is classified as a type IVd delayed hypersensitivity reaction dominated by a T cell-mediated neutrophilic inflammatory pathway [7]. This sequence of events is illustrated in Figure 1, which summarizes the interplay between drug-specific T cells, IL-8 production, and neutrophil recruitment leading to pustule formation.

A key element of this response is the interleukin 36 signaling axis. The IL36RN gene, which encodes the IL 36 receptor antagonist, plays an essential regulatory role. IL 36, produced mainly by keratinocytes and macrophages, requires tight control to modulate inflammation. When IL36RN mutations are present, physiological receptor inhibition is lost, leading to exaggerated IL 36 signaling. This dysregulation amplifies neutrophil recruitment and predisposes individuals to drug-induced pustular eruptions. As also depicted in Figure 2, the combined effect of IL-36 overexpression, Th17-derived cytokines (such as IL-17 and IL-22), and enhanced neutrophilic chemotaxis contributes to the characteristic epidermal pustules seen in AGEP. Together, these genomic and immunologic findings show that AGEP results from the interaction between genetic susceptibility, IL 36 pathway dysregulation and heightened drug-specific immune reactivity [1,2,4,5].

Figure 2.

Mechanism of drug-induced type IVd hypersensitivity reaction. Drug-specific CD4+/CD8+ T cells and Th17 cells induce keratinocyte activation and neutrophil recruitment through cytokine release. Colored arrows represent cytokine-mediated signaling pathways; colored dots indicate specific cytokines (e.g., IL-36, IL-8, IL-17, IL-22), and arrows indicate the direction of cellular interactions and inflammatory signaling. Source: Author’s own elaboration.

3.2. Clinical Features

AGEP typically presents with an abrupt onset within 24 to 48 h after exposure to the causative drug. Some agents, particularly antimalarials and immunotherapies, may exhibit prolonged latencies of up to 22 days, which complicates causal identification. Patients usually develop fever above 38 °C, malaise and neutrophilic leukocytosis, followed by diffuse edematous erythema upon which sterile, non-follicular and pruritic pustules appear. Lesions often begin in intertriginous areas and subsequently spread to the trunk and extremities [1].

Mucosal involvement is not a dominant feature but may occur in about 20 percent of cases, usually limited to a single anatomical site. Between 17 and 20 percent of patients may develop visceral involvement, most commonly hepatic, renal or pulmonary, reflecting the systemic inflammatory response. Cases associated with targeted therapies or immunotherapies may display more complex phenotypes, including prominent mucosal disease or psoriasiform overlap [1,2].

Clinically, AGEP shares several features with other severe cutaneous hypersensitivity syndromes such as DRESS or DIHS and SJS or TEN, which can lead to early diagnostic confusion. Short latency, sterile pustules and rapid improvement after drug discontinuation strongly support AGEP. An underlying IL36RN mutation should be suspected in recurrent episodes, unclear drug temporality or disproportionate severity [3].

3.3. Differential Diagnosis

3.3.1. AGEP vs. GPP

AGEP and generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) share sterile pustules and an IL-36–driven inflammatory signature, which explains their morphological overlap. However, their clinical course differs substantially. AGEP typically develops abruptly after drug exposure and resolves rapidly following drug withdrawal, whereas GPP follows a chronic or relapsing course, often triggered by non-pharmacological factors [1,2,3].

Histologically, AGEP is characterized by acute superficial non-follicular pustules and papillary dermal edema, while GPP shows psoriasiform epidermal changes and pustules associated with chronic plaques or a personal history of psoriasis. Although IL36RN mutations may be present in both conditions, GPP is predominantly autoinflammatory, whereas AGEP represents a drug-induced immune-mediated reaction [1,8].

3.3.2. AGEP vs. DRESS/DIHS

Although AGEP and DRESS/DIHS may share drug exposure and systemic inflammation, they are usually distinguished by latency and clinical evolution. AGEP typically occurs within 24–48 h of drug exposure, while DRESS develops after a prolonged latency of several weeks. DRESS is characterized by marked eosinophilia, lymphadenopathy, and persistent organ involvement, particularly hepatic, with symptoms that do not rapidly resolve after drug discontinuation. Consequently, chronology and clinical course remain the most reliable discriminating features [1,9].

3.3.3. AGEP vs. SJS/TEN

SJS and TEN are clinically distinct from AGEP, despite sharing certain immunologic pathways within the severe cutaneous adverse reaction (SCAR) spectrum. SJS/TEN is characterized by extensive epidermal necrosis, a positive Nikolsky sign, and prominent mucosal involvement, leading to epidermal detachment [1,2].

In contrast, AGEP presents with sterile non-follicular pustules on an erythematous background, minimal keratinocyte necrosis, and limited mucosal involvement. Although SJS/TEN share immunologic features with AGEP, their clinical presentation is usually distinct, and their inclusion here is intended primarily for contextual and mechanistic comparison rather than routine differential diagnosis [1,2,10].

3.4. Histopathology and Biomarkers

Histopathology is essential for confirming AGEP when clinical overlap exists with other pustular dermatoses. Typical findings include early subcorneal or intraepidermal pustules composed of polymorphonuclear neutrophils, mild spongiosis, papillary dermal edema and a mixed dermal inflammatory infiltrate. Variable eosinophils may support a drug-related process, and keratinocyte necrosis is minimal, helping differentiate AGEP from SJS or TEN. Additional features include dermal vasodilation and early neutrophilic exocytosis [1,2,3,11]. A structured summary of histopathological features and key biomarkers is presented in Table 1.

At the molecular level, biomarkers such as IL-36, IL-8 and chemokines like CXCL1 and CXCL2 are consistently elevated, reflecting activation of the IL-36 and IL-8 inflammatory axis. IL 36 overexpression may be associated with IL36RN mutations, increasing susceptibility to drug-induced pustular reactions. These biomarkers are emerging as valuable complementary tools for distinguishing AGEP from GPP [1,2,3,11,12].

Table 1.

Biomarkers and histopathology for AGEP: diagnostic utility and limitations.

Table 1.

Biomarkers and histopathology for AGEP: diagnostic utility and limitations.

| Biomarker/Finding | Description | Diagnostic Utility | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-36 (α, β, γ) [1,2] | Elevated in epidermis and dermis | Differentiates AGEP from other pustuloses; supports drug-dependent hyperinflammation [1,2] | Not routinely available; limited studies |

| IL36RN mutations [1,2,4,5] | Loss of IL-36 receptor antagonist function [1,2,4,5] | Suggests higher risk and greater inflammatory intensity | Requires genetic sequencing |

| Subcorneal/intraepidermal pustules [1,2,3,4,5] | Neutrophil-rich pustules in the superficial epidermis | Classic histologic feature of AGEP [1,2,3,4,5] | Overlaps with pustular psoriasis |

| Papillary dermal edema [1,2,4,5] | Prominent papillary dermal edema [1,2,4,5] | Compatible with AGEP | Also present in other drug reactions |

| Eosinophils in dermis [1,2,4,5] | Mixed inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils [1,2,4,5] | Supports drug-related hypersensitivity | Not specific to AGEP |

| IL-8, CXCL1, CXCL2 [1,2,3,4,5,13,14] | Elevated neutrophil-attracting cytokines [1,2,3,4,5] | Associated with pustular extension | Not routinely available in clinical practice |

However, although the clinical and histopathological features were relatively consistent across findings, multiple studies reported a notable overlap with GPP, DRESS and SJS or TEN, which contributed to diagnostic errors in several cases. This highlights the importance of integrating latency, clinical morphology and histological findings in a comparative manner to reduce diagnostic inaccuracies in contexts of polypharmacy or atypical presentations. A structured comparison of AGEP versus other pustular and severe drug reactions is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Differential diagnosis of AGEP versus other pustular dermatoses and severe drug reactions.

3.5. Diagnostic Algorithm and EuroSCAR Scoring System

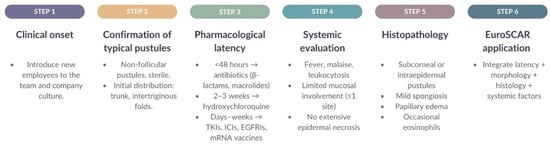

The literature consistently showed that the development of AGEP depends on three major elements: the triggering medication and its latency pattern, the immunologic characteristics of the host and the activation of inflammatory pathways, particularly those mediated by IL 36 and neutrophil recruitment. This interaction explains the phenotypic variability and differences in clinical severity. These elements are integrated into a structured diagnostic pathway summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Clinical diagnostic algorithm for AGEP integrating morphology, pharmacological latency, systemic findings, histopathology, and EuroSCAR criteria. Arrows indicate the sequential diagnostic workflow, and colored blocks represent the different steps of the diagnostic process. Source: Author’s own elaboration.

Although clinical, histopathological and drug latency criteria allow for reasonably accurate diagnostic orientation, their appropriate integration remains challenging in settings involving polypharmacy, targeted therapies and atypical presentations. To reduce diagnostic variability, a clinical algorithm is proposed that synthesizes the essential elements: temporal onset, pustular morphology, systemic findings, oriented histology and application of the EuroSCAR scoring system [4,5,6].

The diagnostic algorithm is based on the EuroSCAR score, which is the most widely used tool for case confirmation. This system integrates variables such as drug latency, pustule characteristics, fever, neutrophilia, mucosal involvement, histopathological findings and clinical evolution after withdrawal. A detailed summary of the EuroSCAR scoring criteria is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

EuroSCAR Scoring System for the Diagnosis of AGEP.

The EuroSCAR score provides clearly defined diagnostic categories (definite, probable, possible and doubtful) and supports diagnostic standardization, facilitates comparisons across studies and enhances clinical decision making. However, limitations may arise, particularly in cases induced by immunotherapies or targeted treatments where clinical patterns tend to deviate from the classic AGEP presentation [28].

Overall, this table serves as a structured reference to improve diagnostic accuracy in AGEP, although the scoring system may be less reliable in non-classical presentations. Interpretation requires considering drug latency, pustular morphology, analytical findings and the clinical response after discontinuation of the suspected agent [4,5,6].

3.6. Main Drugs Involved

The literature review consistently showed that the development of AGEP depends on three main elements: the triggering drug, its pharmacological class, and its latency pattern (Table 4); additionally, it may be associated with host characteristics, including immunological susceptibility, and the activation of inflammatory pathways, particularly those mediated by IL-36 and neutrophilic recruitment. This interaction explains the phenotypic diversity observed and the differences in clinical severity [2,3]. Table 4 provides a structured overview of pharmacological classes implicated in AGEP, including their characteristic latency patterns, proposed mechanisms, and representative clinical examples.

Table 4.

Drugs involved in AGEP.

This table summarizes the classic histological patterns such as subcorneal or intraepidermal pustules, superficial neutrophilic infiltrate, mild spongiosis and papillary edema, along with the most relevant biomarkers, including IL 36 and IL 8, providing a useful comparative framework for interpreting biopsies and complementary studies in complex clinical scenarios.

3.6.1. Antibiotics

Antibiotics are the most frequently implicated drug class in AGEP, particularly beta lactams such as penicillins and cephalosporins, as well as macrolides. These agents typically present with a short latency period, usually less than 48 h, which facilitates diagnostic orientation in complex clinical settings [1,4,5]. The predominant mechanism described in the literature suggests a lymphocyte hapten reaction in which the drug or one of its metabolites acts as the trigger for the inflammatory cascade characteristic of AGEP. In addition, multiple studies indicate that concomitant infections may activate parallel inflammatory pathways, creating a favorable environment for antibiotic-induced pustular reactions and complicating identification of the true causal agent in certain patients [1,2,3].

3.6.2. Antimalarial Agents

HCQ is the second most frequently reported drug associated with AGEP after antibiotics, with a notable increase in cases during the COVID-19 pandemic. Unlike antibiotics, HCQ generally presents with a prolonged latency period, typically between two and three weeks [1,4,5]. Evidence indicates that HCQ can potentiate the IL 36-mediated inflammatory pathway, particularly in patients with IL36RN mutations, which enhances neutrophil recruitment and contributes to the development of the pustular lesions characteristic of AGEP. This prolonged latency, along with its morphological similarity to other pustular reactions, increases the risk of diagnostic confusion between conditions [1,2].

3.6.3. Targeted Therapies and Immunotherapies

Targeted therapies and immunotherapies constitute an emerging group of agents capable of inducing AGEP. Pustular eruptions have been reported with EGFR inhibitors, ICI and several TKIs, frequently presenting with atypical clinical patterns and variable latency [1,13]. ICIs directed against CTLA 4 or PD 1 and PD L1 have been associated with infrequent but immunologically intense cutaneous adverse events. In these patients, distinguishing AGEP from drug-induced pustular psoriasis may be particularly challenging due to the shared activation of the IL 36 and IL 8 inflammatory axis. This overlap has produced contradictory reports and highlights the need for more robust diagnostic tools in this population [1,4,5].

3.6.4. Psychotropic Medications

Psychotropic drugs represent a less common group within the spectrum of medications associated with AGEP. Nevertheless, isolated cases related to haloperidol and olanzapine have been reported, typically showing short latency and marked neutrophilia. The available evidence remains limited and is based primarily on individual case reports, which makes it difficult to establish a solid causal relationship. Furthermore, discontinuing the medication in the context of an underlying psychiatric disorder introduces an additional challenge in clinical decision making [32,33].

3.6.5. Vaccines

Vaccines, particularly mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines, have been associated with a small but consistent number of AGEP cases. Unlike classical pharmacological triggers, these episodes seem to be mediated by systemic immune activation rather than a hapten-dependent mechanism. This may explain their variable latency, minimal systemic involvement and the excellent response to topical corticosteroids described in most reports. In general, vaccine-induced AGEP follows a benign course with rapid resolution [34,35].

3.7. Pharmacovigilance Findings and Emerging Drug-Association Signals

Pharmacovigilance data obtained from the literature and international spontaneous reporting systems confirm that AGEP remains an infrequent yet clinically significant adverse reaction, with reporting patterns that have evolved considerably over the past twenty years. Information from FAERS, EudraVigilance and other surveillance platforms has made it possible to identify high-risk drugs as well as emerging therapeutic combinations that may precipitate AGEP in susceptible populations [37].

FAERS reports from 2004 to 2024 show a progressive increase in AGEP notifications, particularly associated with antibiotics, antimalarial agents, targeted therapies and psychotropic medications [38]. This real-world analysis demonstrated that the drugs with the highest reporting odds ratios include beta lactams, macrolides, HCQ, kinase inhibitors and certain antipsychotics, which is consistent with trends observed in clinical studies and case series [1,5,15,20,23,33]. The data also suggest that polypharmacy and the combined use of immunomodulatory agents increase the relative risk of AGEP, especially in oncology patients and in individuals with chronic inflammatory diseases.

Complementary to these findings, a network pharmacovigilance analysis identified associations between specific drug combinations and the onset of AGEP, highlighting possible synergistic interactions between antibiotics, systemic anti-inflammatory drugs and therapies targeting EGFR or tyrosine kinases [39]. This network-based approach reinforces the concept that AGEP is not necessarily the result of a single agent but may be facilitated by pharmacodynamic interactions and inflammatory environments amplified by multiple medications, which could explain cases with atypical latency or non-classical clinical presentations. Network pharmacovigilance analyses suggest that AGEP may arise not only from single-drug exposure but also from synergistic pharmacodynamic interactions, particularly in the context of polypharmacy involving antibiotics, systemic anti-inflammatory agents, and targeted therapies [39].

Data from EudraVigilance additionally reveal that drugs traditionally considered low risk, such as paracetamol, may be involved in severe hypersensitivity reactions within the SCAR spectrum, including pustular variants compatible with AGEP, although with lower frequency [40]. This observation underscores the need to avoid dismissing commonly used medications during chronological assessment of suspected cases, particularly in scenarios involving multiple concomitant exposures.

In line with pharmacovigilance findings, the review also identified new and emerging signals related to AGEP. Messenger RNA-based COVID-19 vaccines have shown infrequent but reproducible cases, generally with rapid evolution and minimal systemic involvement [34,35]. ICIs are displaying an increasingly recognized risk pattern, often presenting with mixed phenotypes between AGEP and drug-induced pustular psoriasis [9]. Iodinated contrast media have been identified as sporadic but well-documented triggers, and targeted therapies such as erlotinib have generated consistent pharmacovigilance signals supported by multiple published reports [10,40].

Taken together, pharmacovigilance findings highlight three key elements. First, there is a progressive broadening of the pharmacological spectrum associated with AGEP, influenced by the expanding use of modern immunologic and oncologic therapies. Second, detailed chronological analysis of multi-drug exposure is essential, particularly in patients receiving combination treatments [40]. Third, there is a growing need for more robust early warning systems and diagnostic algorithms that integrate data mining approaches, standardized tools such as EuroSCAR and emerging biomarkers linked to the IL-36 and IL-8 pathways [10,40].

The consolidation of these data confirms that AGEP should be understood as a dynamic immunologic phenomenon in which the interaction between host genetics, pharmacologic profile and inflammatory susceptibility determines the final risk. This information is crucial to improving early detection, optimizing timely withdrawal of the causative drug and strengthening traceability within national and international reporting systems. Overall, the evidence emphasizes the importance of adopting a multidimensional diagnostic strategy that integrates drug chronology, clinical morphology, histopathology, emerging biomarkers and standardized criteria such as EuroSCAR to enhance diagnostic accuracy [40]. Early identification of the causative agent and understanding of new clinical variants associated with modern therapies are essential to optimize management, reduce morbidity and prevent recurrence. Future multicenter studies, ideally incorporating immunogenomic analyses, will be crucial to advancing toward a more refined and well-supported classification of AGEP in the era of precision medicine [10,40].

3.8. Limitations of the Evidence, Clinical Implications and Future Directions

Important limitations persist within the available literature. The predominance of case reports and small case series, combined with methodological heterogeneity and the scarcity of prospective research, restricts the ability to establish robust associations between specific drugs and the development of AGEP. Likewise, the absence of validated clinical biomarkers and the limited immunogenomic characterization beyond IL36RN reduce the capacity for early differentiation from entities such as GPP or DRESS [1,2,3,4,5].

Taken together, this review underscores the need for a multidimensional diagnostic approach that integrates drug chronology, clinical morphology, histopathology, emerging biomarkers and standardized tools such as EuroSCAR to enhance diagnostic accuracy. Early identification of the causative agent and proper interpretation of phenotypes associated with modern therapies are essential for optimizing management, reducing morbidity and preventing recurrences.

Looking ahead, multicenter studies incorporating immunogenomic analyses, more sensitive diagnostic methods and adaptations to the EuroSCAR scoring system that account for clinical patterns arising from targeted therapies and immunotherapies will be critical. These research initiatives will support the development of a more precise classification of AGEP within the context of personalized medicine.

4. Conclusions

AGEP is a severe cutaneous reaction whose diagnosis relies on appropriate integration of clinical presentation, histopathology and medication history. Although antibiotics remain the most common triggers, the increasing number of cases associated with antimalarial agents, targeted therapies, immunotherapies and vaccines reflects an expanding and increasingly complex therapeutic landscape.

Advances in understanding its inflammatory mechanism, characterized by activation of the IL 36 axis and a neutrophil-rich response mediated by T-lymphocytes, have clarified its similarities with other pustular dermatoses, particularly GPP. However, much of the current knowledge is based on clinical reports and observational studies, highlighting the need for prospective research and improved molecular characterization.

The use of standardized diagnostic criteria remains essential to enhance accuracy and guide appropriate management, especially in patients receiving immunomodulatory therapies or presenting with atypical features. Overall, these findings emphasize the importance of comprehensive diagnostic evaluation and rigorous pharmacovigilance to optimize clinical management and prevent recurrence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.Z.-M. and A.E.-C.; methodology, E.Z.-M.; validation, E.Z.-M., A.E.-C. and J.M.-J.; formal analysis, E.Z.-M. and J.M.-J.; investigation, E.Z.-M., A.E.-C., J.M.-J., S.A.-C., A.J.H.-V., L.C.M.-B. and J.H.-L.; resources, L.C.M.-B. and J.H.-L.; data curation, E.Z.-M. and S.A.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, E.Z.-M., A.E.-C. and J.M.-J.; writing—review and editing, S.A.-C., A.J.H.-V., L.C.M.-B. and J.H.-L.; visualization, J.M.-J. and S.A.-C.; supervision, E.Z.-M.; project administration, E.Z.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the results of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. Due to privacy and ethical restrictions, data are not publicly available. However, aggregated summary data are included in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AGEP | Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis |

| DRESS/DIHS | Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms/drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome |

| EGFR | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor |

| FAERS | FDA Adverse Event Reporting System |

| GPP | Generalized pustular psoriasis |

| HCQ | Hydroxychloroquine |

| ICI | Immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| IL | Interleukin |

| SJS/TEN | Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis |

| TKI | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Complete search strategies by database, filters applied and date of last query.

Table A1.

Complete search strategies by database, filters applied and date of last query.

| Database | Search Strategy (Exact Syntax) | Filters Applied in the Database | Date of Last Search |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed/MEDLINE | (“Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis”[MeSH] OR AGEP[tiab] OR “drug-induced pustulosis”[tiab]) AND (“Drug Hypersensitivity”[MeSH] OR “drug eruption”[tiab]) AND (“Interleukin-36”[MeSH] OR IL-36RN[tiab] OR “IL36RN mutation”[tiab]) | Humans; Adults ≥ 18 years; English/Spanish; Publication date 2000–2025 | 18 November 2025 |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY(“acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis” OR AGEP OR “drug-induced pustulosis”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(“drug hypersensitivity” OR “adverse drug reaction”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(“IL-36” OR “IL-36RN”) | Article or Review; Human studies; 2000–2025 | 18 November 2025 |

| ScienceDirect | “acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis” AND “drug hypersensitivity” AND (“IL-36” OR “IL-36RN”) | Research articles; Clinical medicine; 2000–2025 | 18 November 2025 |

| SpringerLink | (“acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis” OR AGEP) AND (“drug-induced” OR “drug hypersensitivity”) AND (“IL-36” OR “IL36RN mutation”) | Medicine; Dermatology; 2000–2025 | 18 November 2025 |

References

- Parisi, R.; Shah, H.; Navarini, A.A.; Muehleisen, B.; Ziv, M.; Shear, N.H.; Dodiuk-Gad, R.P. Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis: Clinical Features, Differential Diagnosis, and Management. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2023, 24, 557–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sussman, M.; Napodano, A.; Huang, S.; Are, A.; Hsu, S.; Motaparthi, K. Pustular Psoriasis and Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis. Medicina 2021, 57, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, A.; Deshpande, P.; Campbell, C.N.; Krantz, M.S.; Mukherjee, E.; Mockenhaupt, M.; Pirmohamed, M.; Palubinsky, A.M.; Phillips, E.J. Updates on the Immunopathology and Genomics of Severe Cutaneous Adverse Drug Reactions. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 151, 289–300.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetart, F.; Walsh, S.; Milpied, B.; Gaspar, K.; Vorobyev, A.; Tiplica, G.S.; Didona, B.; Welfringer-Morin, A.; Kucinskiene, V.; Bensaid, B.; et al. Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis: European Expert Consensus for Diagnosis and Management. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2024, 38, 2073–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, P.-C.; Oschmann, A.; Kerl-French, K.; Maul, J.-T.; Oppel, E.M.; Meier-Schiesser, B.; French, L.E. Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis: Clinical Characteristics, Pathogenesis, and Management. Dermatology 2023, 239, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, Y.J.; Akhtar, S.; Ahmad, M.; Hassan, I.; Wani, R. Etiopathological and Clinical Study of Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis: Experience from a Tertiary Care Hospital in North India. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2020, 11, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marovt, M.; Marko, P.B. Denosumab-Induced Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2024, 104, adv40430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Díaz, R.; Daudén, E.; Carrascosa, J.M.; Cueva, P.D.L.; Puig, L. Generalized Pustular Psoriasis: A Review on Clinical Characteristics, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Dermatol. Ther. 2023, 13, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagranda, A.; Suppa, M.; Dehavay, F.; del Marmol, V. Overlapping DRESS and Stevens-Johnson Syndrome: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep. Dermatol. 2017, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfalah, M.; Alotaibi, Y.; Alotaibi, A.; Alharthi, R. Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Induced by Iodinated Contrast Media: A Case Report. Dermatol. Rep. 2025, 17, 10217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.J.; Sathe, N.C.; Ganipisetti, V.M. Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Benezeder, T.; Bordag, N.; Woltsche, J.; Falkensteiner, K.; Graier, T.; Schadelbauer, E.; Cerroni, L.; Meyersburg, D.; Mateeva, V.; Reich, A.; et al. IL-36-Driven Pustulosis: Transcriptomic Signatures Match between Generalized Pustular Psoriasis (GPP) and Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis (AGEP). J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2025, 155, 1913–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospischil, I.; Hoetzenecker, W. Drug Eruptions with Novel Targeted Therapies—Immune Checkpoint and EGFR Inhibitors. JDDG J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2021, 19, 1621–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, M.; Yagi, M.; Wakasugi, Y.; Hattori, H.; Uno, K. A Study of Elevated Interleukin-8 (CXCL8) Detection of Leukocyte Migration Inhibitory Activity in Patients Allergic to Beta-Lactam Antibiotics. Allergol. Int. 2011, 60, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.; Yao, C.; Lo, Y. Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Induced by Hydroxychloroquine. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2021, 37, 1122–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Navarro, I.; Abril-Pérez, C.; Roca-Ginés, J.; Sánchez-Arráez, J.; Botella-Estrada, R. A Case of Cefditoren-Induced Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis during COVID-19 Pandemics. Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions Are an Issue. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, e537–e539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.M.; Dhanani, S.; Patel, K.; Nair, P. Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Following Ceftriaxone. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2024, 56, 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimas, N.; Quintanilla-Dieck, J.; Vandergriff, T. Stevens–Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis. In Cutaneous Drug Eruptions; Hall, J.C., Hall, B.J., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2015; pp. 259–269. ISBN 978-1-4471-6728-0. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: MedlinePlus Genetics. Available online: https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/stevens-johnson-syndrome-toxic-epidermal-necrolysis/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Marwa, K.; Goldin, J.; Kondamudi, N.P. Type IV Hypersensitivity Reaction. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Litaiem, N.; Hajlaoui, K.; Karray, M.; Slouma, M.; Zeglaoui, F. Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis after COVID-19 Treatment with Hydroxychloroquine. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e13565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifzadeh, S.; Mohammadpour, A.H.; Tavanaee, A.; Elyasi, S. Antibacterial Antibiotic-Induced Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS) Syndrome: A Literature Review. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 77, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, E.L.; Olamiju, B.; Leventhal, J.S. Potentially Life-threatening Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions Associated with Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. Oncol. Rep. 2021, 45, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantz, R.; Huang, S.; Are, A.; Motaparthi, K. Stevens–Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: A Review of Diagnosis and Management. Medicina 2021, 57, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canhão, G.; Pinheiro, S.; Cabral, L. Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: A Clinical and Therapeutic Review. Eur. Burn J. 2022, 3, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hama, N.; Abe, R.; Gibson, A.; Phillips, E.J. Drug-Induced Hypersensitivity Syndrome (DIHS)/Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS): Clinical Features and Pathogenesis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2022, 10, 1155–1167.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiempanakit, K.; Apinantriyo, B. Clindamycin-Induced Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis: A Case Report. Medicine 2020, 99, e20389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mima, Y.; Ohtsuka, T. Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Following the Administration of Cephalexin: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Cureus 2025, 17, e79205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odorici, G.; Schenetti, C.; Pacetti, L.; Schettini, N.; Gaban, A.; Mantovani, L. Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Due to Hydroxichloroquine. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komiya, N.; Takahashi, K.; Kato, G.; Kubota, M.; Tashiro, H.; Nakashima, C.; Nakamura, T.; Iwanaga, K.; Kimura, S.; Sueoka-Aragane, N. Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Caused by Erlotinib in a Patient with Lung Cancer. Case Rep. Oncol. 2021, 14, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liquete, E.; Ali, S.; Kammo, R.; Ali, M.; Alali, F.; Challa, H.; Fata, F. Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Induced by Erlotinib (Tarceva) with Superimposed Staphylococcus Aureus Skin Infection in a Pancreatic Cancer Patient: A Case Report. Case Rep. Oncol. 2012, 5, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, C.; Jaiswal, S.; Jayanath, B.P.; Paliwal, S.; Dey, P.; Mehta, V. Haloperidol-Induced Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis: A Rare Side Effect. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2022, 24, 21cr03051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakhar, J.; Badyal, R.; Kumar, S.; Prasad, S. Olanzapine-Induced Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis: A Case Report. Indian J. Psychiatry 2021, 63, 411–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Lin, T. Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 Vaccine-induced Acute Localized Exanthematous Pustulosis. J. Dermatol. 2021, 48, e562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, W.C.; Lee, J.S.S.; Chong, W.-S. Tozinameran (Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine)-Induced AGEP-DRESS Syndrome. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2022, 51, 796–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agaronov, A.; Makdesi, C.; Hall, C.S. Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Induced by Moderna COVID-19 Messenger RNA Vaccine. JAAD Case Rep. 2021, 16, 96–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raschi, E.; La Placa, M.; Poluzzi, E.; De Ponti, F. The Value of Case Reports and Spontaneous Reporting Systems for Pharmacovigilance and Clinical Practice. Br. J. Dermatol. 2021, 184, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Que, H.; Zheng, X.; Li, X.; Wang, W. Risk Factors for Drug-Induced Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis (AGEP) from 2004 to 2024: A Real-World Study Based on the FAERS. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2025, 18, 2835–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-De la Torre, A.; van Weenen, E.; Kraus, M.; Weiler, S.; Feuerriegel, S.; Burden, A.M. A Network Analysis of Drug Combinations Associated with Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis (AGEP). J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popiołek, I.; Piotrowicz-Wójcik, K.; Porebski, G. Hypersensitivity Reactions in Serious Adverse Events Reported for Paracetamol in the EudraVigilance Database, 2007–2018. Pharmacy 2019, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.