Simple Summary

The Military Macaw (Ara militaris) is a bird that is endangered in Mexico primarily due to habitat loss and illegal capture. To develop better tools to protect this species, we must understand how the Macaw’s diet provides the nutrients necessary for its survival and reproduction. Here, we analyzed the nutritional value of the pulp and seeds that macaws consume in the Alto Balsas Basin, Mexico. We found patterns in the seasonal availability of the fruiting species consumed by Macaws that suggest that macaws may shift their use of resources in accordance with their energy demands during different periods. During the breeding season, the resources available are those richest in protein and lipids could potentially support courtship, egg formation, and feeding young, whereas, during the non-breeding season, the available species used by Military Macaws have higher carbohydrate and lipid content. Although these results are limited in that they measure resource availability rather than consumption, they provide potential insights into nutritional strategies. They could be used to determine tree species that represent essential resources for macaws, which are essential to support the long-term survival of this iconic species.

Abstract

The Military Macaw is a Neotropical psittacid that is endangered in Mexico. It faces significant threats due to habitat loss and the illegal pet trade. However, little is known about the nutritional characteristics of the plant resources available to this species throughout its annual cycle. This study aimed to characterize the nutritional profile of the fruits consumed by macaws in the Alto Balsas Basin, Mexico, and to infer potential seasonal patterns in the availability of the fruits they feed on in relation to the Macaws’ reproductive phenology. We identified 13 plant species that have been consistently reported as components of the diet of the macaws within the Alto Balsas Basin using a literature review, field observations, and local interviews. We conducted bromatological analyses to assess the content of moisture, protein, lipids, carbohydrates, and fiber for the pulp and seeds of all 13 identified plant species. Although we did not measure quantitative food intake, we integrated these data with reproductive phenology and resource availability to infer potential patterns of nutritional use. The results revealed significant differences in nutritional content among the different species, as well as seasonal variation in the nutritional profiles of available resources that coincide with the physiological demands of the macaw life cycle. During the non-breeding season, the availability of species whose fruits have high lipid and carbohydrate contents, such as Bursera spp., hackberry and madras thorn, may provide essential energy. Conversely, during the breeding season, resources with higher lipid and protein content (such as Mexican kapok tree and red mombin) could support the increased energetic investment associated with courtship, egg production, and chick provisioning. Although our study did not directly quantify the amount of each food item consumed, the integration of nutritional and ecological data provides a preliminary view of how resource quality may influence seasonal foraging patterns, offering valuable insights for the conservation and management of this species.

1. Introduction

The Military Macaw is one of the most threatened psittacine species in Mexico, primarily due to habitat loss, landscape fragmentation, and capture for the illegal wildlife trade [1,2,3]. Consequently, it is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List [4] and classified as Endangered under Mexican environmental law [5]. This Neotropical species primarily inhabits tropical dry forests in Mexico and South America [6,7,8]. In Mexico, its historical distribution spans the Sierra Madre Oriental, Sierra Madre Occidental, and Sierra Madre del Sur [9,10,11]. This includes the Alto Balsas Basin, an area of high biodiversity characterized by tropical deciduous and semi-deciduous forests, as well as patches of oak forest, which provide essential feeding resources [3,8,12,13,14].

Throughout its range, the Military Macaw utilizes a wide variety of food resources [11,15,16,17,18,19]. Its diet consists primarily of seeds and fruit pulp, though it occasionally includes flowers and leaves [17]. However, the species consumes only about 10% to 23% of the total plant species available, suggesting a highly specialized diet [11,17,19].

Understanding psittacine diets is essential for assessing their nutritional requirements and the factors influencing their reproduction and survival [20,21,22,23]. These requirements vary throughout the life cycle. For example, proteins are vital during reproduction, as eggs contain approximately 38% protein, and demand is influenced by the number and composition of eggs [20,24,25,26]. Lipids also serve as a key energy source, especially during reproduction, with eggs containing about 31% fat [27]. Lipid deficiencies can reduce egg size, impair feather development, and affect skin quality [20,24,26]. Carbohydrates are the primary immediate energy source and may increase in demand by 3% to 20% during molting [26,27].

Despite the importance of these nutrients, the nutritional value of resources consumed by wild Military Macaw has been poorly documented. The available studies have only partially described the qualitative and quantitative composition of certain plant species, often linking these data tangentially to the species’ annual biological cycle without measuring intake directly. Early bromatological analyses by Contreras-González et al. [17] evaluated five plant species consumed by Military Macaw in the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Biosphere Reserve. Mountain peanut butter tree (Bunchosia montana) showed the highest carbohydrate content during the non-breeding season, while tetetzo cactus (Cephalocereus tetetzo) fruits had high protein and lipid concentrations, the latex of frangipani (Plumeria rubra) was rich in lipids, and the leaves of chupandia (Cyrtocarpa procera) and makoy’s tillandsia (Tillandsia makoyana) had high moisture content during the breeding season. However, Carrillo et al. [28] reported that in the El Salado Estuary, Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco, Military Macaws feed primarily on white mangrove (Laguncularia racemosa) and red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle) fruits during the non-breeding season, taking advantage of their high mineral, lipid and carbohydrate content to cope with winter conditions. Likewise, Puebla-Olivares et al. [22] and De la Parra et al. [19] analyzed possum wood (Hura polyandra) seeds in Salazares, Nayarit, and Cajón de Peñas, Jalisco, identifying it as a key resource during the breeding season due to its high moisture, lipid, protein, and carbohydrate content.

Bromatological analysis of plant resources consumed by Military Macaw quantifies the contents of essential nutrients (moisture, protein, lipids, carbohydrates, and fiber) that are fundamental to the species’ metabolism, reproductive physiology, and foraging behavior [17,19,22,28]. Moreover, seasonal variation in the availability and nutritional quality of food may significantly influence the species’ biology. For example, during seasons when food resources are scarce, Military Macaws may adopt broader foraging strategies, explore alternative habitats or incorporate lower-quality plant species, potentially affecting body condition [17,18,29,30,31].

In this study, we examine the bromatological composition of different plant species that have been reported in the diet of the Military Macaw in the Alto Balsas Basin, and we analyzed their association with different stages of the reproductive and non-reproductive seasons. Because actual intake was not measured, our approach emphasizes the interpretation of nutritional availability rather than direct dietary composition. We considered factors such as temporal variability in food resources, foraging pattern, and the potential for nutritional complementarity in the diet.

Therefore, we test the hypothesis that seasonal patterns of fruit use reflect shifts in resource quality, with macaws adjusting their diet to meet the changing energetic and physiological demands of their annual cycle. Specifically, we expect that during the non-breeding season macaws rely on lipid and carbohydrate rich species to build energy reserves, that courtship and mating are supported by the selective intake of high-energy fruits, and that egg formation and chick provisioning coincide with the consumption of protein and moisture rich resources that sustain embryonic development and nestling growth.

The findings will not only enhance our understanding of the species’ trophic ecology but also provide valuable insights for the management and conservation of its habitat to ensure the long-term availability of key nutritional resources.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

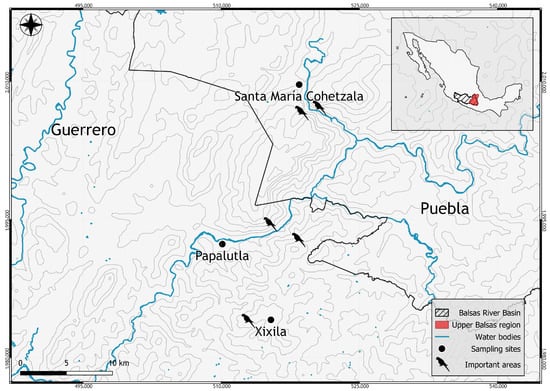

The study was conducted in the Alto Balsas Basin, Mexico, across three localities: Papalutla and Xixila in the state of Guerrero, and Santa María Cohetzala in Puebla, Mexico (Figure 1). Papalutla, Guerrero, is located along the Balsas River on the border between the municipalities of Copalillo and Olinalá, at coordinates 18°01′21′′ N; 98°54′15′′ W [32,33]. The climate is warm sub-humid with dry winter (Aw), characterized by summer–autumn rainfall, with an average annual precipitation of 780 mm and a mean annual temperature of 28 °C [34]. The predominant vegetation consists of tropical deciduous and semi-deciduous forest, with patches of riparian forest elements [35].

Figure 1.

Map of the Alto Balsas Basin, Mexico. The black points indicate the locations where fruits of different plant species consumed by the Military Macaw were collected.

Xixila, also located in Guerrero, spans the coordinates 17°41′59′′ to 18°03′48′′ N, and 98°36′43′′ to 98°58′54′′ W. The climate is warm sub-humid (A)C(w), with an average annual precipitation of 1000 mm and a mean temperature of 26 °C [34]. The dominant vegetation is deciduous and semi-deciduous tropical forest, with ecotonal transitions into pine-oak forest [33].

Santa María Cohetzala is located in the southwestern most region of Puebla, at coordinates 18°11′ N; 98°49′ W, and is traversed by the Nexapa and Atoyac rivers [8]. The climate is warm sub-humid with dry winter (Aw), characterized by summer–autumn rainfall, with an average annual precipitation of 800 mm and a mean annual temperature of 28 °C [36]. Vegetation is primarily composed of deciduous and semi-deciduous tropical forest, as well as patches of oak forest [32,35].

2.2. Selection of the Tree Species Included in the Military Macaw’s Diet

We used three complementary strategies to identify plant species that have been reported as part of the Military Macaw’s diet and determine when each species has fruits available to macaws. The first strategy was an exhaustive and systematic literature search. We performed the search on 10 October 2022 in English and Spanish using major databases (Cambridge Scientific Abstracts, Science Citation Index, Searchable Ornithological Research Archive) and major publishers (Springer-Verlag and Elsevier), as well as the websites of scientific societies that specialize in ecology and ornithology. The search strings combined the following search terms: “Ara militaris”, “Alto Balsas Basin”, “diet”, “feeding”, “habitat use” and “Military Macaw”. Searches were applied to titles, abstracts, and keywords. The initial search retrieved 187 records; after removing duplicates and applying inclusion criteria (i.e., studies reporting diet or plant resource use), 10 studies were retained, four of which contained specific dietary information for the Alto Balsas Basin [8,12,13,14].

The second approach was a series of unstructured interviews conducted between December 2022 and January 2024 with local residents from the three study localities to gather information not available in published sources [8]. Participants were selected using purposive sampling based on their experience observing macaws. We interviewed a total of 15 key informants. Interviews were informal and open-ended, focusing on fruiting periods and plant species observed being consumed by macaws. Responses were recorded in field notes and later coded by frequency of mention.

The third approach consisted of opportunistic direct observations of the Military Macaw’s feeding behavior conducted during fruit-collection surveys between December 2022 and April 2024 across the three study localities. These observations were not designed as systematic behavioral sampling but were obtained incidentally while locating and collecting fruits from plant species previously reported as food resources.

During these surveys, we recorded the plant species used, the plant part consumed (pulp or seed), the date, and the locality whenever macaws were directly observed feeding. No focal sampling was performed, and no quantitative measures of feeding rates, handling times, or intake were collected. Consequently, these observations were used exclusively to confirm the use of plant species identified through literature and/or interviews.

From these combined sources, we identified 18 tree species that were reported to be consumed by Military Macaws in the Alto Balsas Basin (Table A1). A subset of 13 species was selected for bromatological analysis based on their consistent documentation, their availability during the sampling period, and their recurrent mention across sources. As such, they represent the best supported components of the diet in the region and the most relevant candidates for nutritional characterization.

While we were unable to quantify the amounts of each plant species consumed, we categorized the relative importance of each food resource by integrating information from regional literature, interviews with residents, and opportunistic field observations recorded during fruit collection. Based on the recurrence and number of mentions, we classified each plant species as a dominant, supplementary, or occasional resource, following dietary assessment criteria commonly applied in psittacine ecology, e.g., [19,23].

2.3. Collection of Plant Material

Field sampling was conducted from December 2022 through April 2024 across all three study zones to collect specimens from tree species consumed by the Military Macaw. We obtained samples of fruits by systematic collection in Macaw foraging sites in tropical deciduous and semi-deciduous forest, as well as ecotones of oak forest [17]. The following species were collected: bolivar’s bursera (Bursera bolivarii), copal tree (Bursera copallifera), gumbo-limbo (Bursera simaruba), Mexican elemi tree (Bursera morelensis), golden spoon (Byrsonima crassifolia), Mexican kapok tree (Ceiba aesculifolia), hackberry (Celtis caudata), elephant ear tree (Enterolobium cyclocarpum), Mexican mountain papaya (Jacaratia mexicana), coulter’s acacia (Mariosousa coulteri), madras thorn (Pithecellobium dulce), frangipani (Plumeria rubra) and red mombin (Spondias purpurea) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Tree species consumed by the Military Macaw in the Alto Balsas Basin, Mexico, including evidence source, relative dietary importance, and season of use.

Fruits were collected from three individuals of each tree’s species, using a pruning pole ensuring samples were either ripe or dry according to the Military Macaw’s feeding patterns. Between 300 and 500 g of fruits were collected per individual. Note that the statistical unit for species-level comparisons was the mean value per tree, not individual fruits. The samples were immediately stored in airtight bags and frozen for subsequent laboratory analysis [17,22,28].

2.4. Nutritional Content

We performed bromatological analysis to quantify the moisture, total proteins, total lipids, total carbohydrates, and total fiber. For these analyses, frozen samples were left at room temperature until completely thawed [17,22].

Moisture content was calculated from ten fruits per tree. After thawing, samples were weighed to record the fresh weight, then they were oven-dried at 70 °C until reaching constant weight (recorded as dry weight). Moisture content was calculated as the difference between fresh and dry weights [17]. For the protein, lipid, and carbohydrate analyses, we separated the pulp from the seeds of all collected fruits and pooled the fruits by tree. Thus, each tree contributed a single pulp value and a single seed value for each nutrient. The samples were then oven-dried at 70 °C, pulverized with a mortar and pestle, and subsampled (50 g each of pulp and seed) for subsequent analyses [17].

Total protein percentage was quantified using the micro-Kjeldahl method [37,38,39]. Total lipids were determined by Soxhlet extraction [37], and total carbohydrates were measured via glucose quantification using Clegg’s anthrone method [40]. For total fiber quantification, ash content was first determined by muffle furnace incineration [41]. Total fiber percentage was calculated by subtracting the sum of the percentages of protein, lipid, carbohydrate, and ash from the fruit’s dry weight [41].

2.5. Association Between Nutrients and Macaw Annual Biological Cycle

To assess the association between the nutritional content of the Military Macaw’s diet and its reproductive and non-reproductive periods, we considered two general yearly stages—reproductive (March–September) and non-reproductive (October–February; [8,13,14]. The reproductive period is further divided into courtship and copulation (March–April), incubation (May–June), chick-feeding (July–August), and fledging of young (September). We then determined the fruiting periods of the 13 tree species analyzed in the study area using the strategies previously described in Section 2.2.

This information was compiled into a table that associated the months of the year with the reproductive phases of the Military Macaw and the temporal availability of the fruits of each of the 13 tree species.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

To evaluate the nutritional content (moisture, total proteins, total lipids, total carbohydrates, and total fiber) in the pulp and seeds of fruits consumed by the Military Macaw, we first assessed normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. For each species, three individual trees were sampled, and each tree contributed one mean value per nutrient for pulp and one for seeds (n = 3 per species per nutrient per tissue). Because those data did not meet normality assumptions, all statistical analyses were performed using non-parametric tests [42,43].

For each nutrient (moisture, protein, lipids, carbohydrates, and fiber), we compared values among species using the Kruskal–Wallis test, applied separately to pulp and seeds. Dunn’s post hoc test with Bonferroni correction was then performed to identify which species exhibited significant differences in nutritional content. In addition, we performed seasonal comparisons of the nutrient content of the species available across the five stages of the annual cycle: non-reproductive, courtship and copulation, egg-laying and nesting, feeding chicks, and fledglings. Because each plant species was evaluated across all seasonal stages, nutritional values were analyzed as repeated measures. For this reason, Friedman’s test was used to detect overall differences among the five stages. Seasonal comparisons were conducted using an unweighted approach, in which all fruiting species available during each stage were given equal weight. This analysis therefore characterizes seasonal variation in the nutritional landscape available to macaws rather than differential use or selection of particular species. All statistical analyses were conducted using PAST 4.03 [44], following the statistical criteria established by Sokal and Rohlf [42] and Zar [43].

3. Results

3.1. Relative Importance of Food Resources in the Diet of the Military Macaw

The integration of information from regional literature, local interviews, and opportunistic field observations allowed us to semi-quantitatively categorize the 13 plant species included in the bromatological analysis according to their relative importance (Table 1). This classification revealed clear patterns in how macaws use food resources during the five different stages of their annual cycle.

Three species (copal tree, bolivar’s bursera, and hackberry) were identified as dominant resources due to their recurrent documentation across sources. Several species appeared as supplementary resources, including Mexican elemi tree, gumbo-limbo, golden spoon, madras thorn, Mexican mountain papaya, elephant ear tree, and red mombin. Coulter’s acacia and frangipani were categorized as occasional resources due to their infrequent mention. Importantly, we emphasize that these categories reflect frequency of documentation and availability, rather than direct quantitative intake by macaws. Thus, the patterns we describe represent ecological inferences based on available information rather than confirmed feeding rates.

3.2. Nutritional Content of Fruits (Pulp and Seeds)

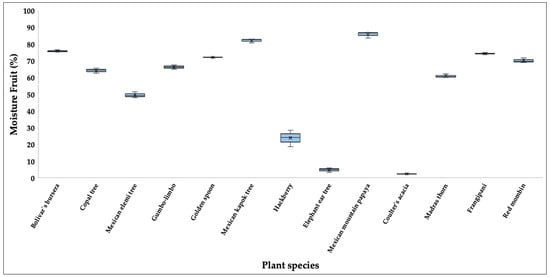

Moisture content of the whole fruit (combined pulp and seed) showed wide variation among species (Table S1). The highest values were recorded in Mexican mountain papaya (85.84%) and Mexican kapok tree (82.10%), while the lowest was in coulter’s acacia (2.24%), elephant ear tree (4.77%) and hackberry had 23.80%. Significant differences among species were detected (H = 34.74, p < 0.05). Post hoc comparisons indicated that coulter’s acacia differed significantly from both Mexican kapok tree and Mexican mountain papaya (p < 0.05), and elephant ear tree differed significantly from Mexican mountain papaya (p < 0.05) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Boxplots showing the moisture (%) of fruits consumed by the Military Macaw in the Alto Balsas Basin, Mexico. For each species, boxes indicate the interquartile range (IQR), horizontal lines represent medians, whiskers show minimum and maximum values, and crosses denote mean values.

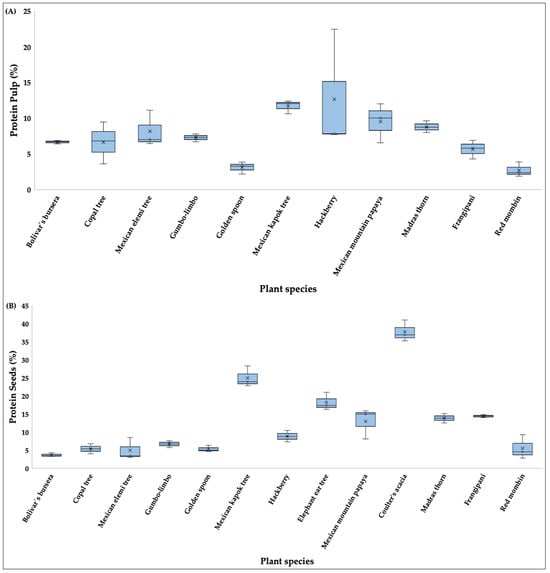

Regarding total percentage of protein content in pulp (Figure 3A), the highest values were in hackberry (12.65%), Mexican kapok tree (11.66%), Mexican mountain papaya (9.52%), and madras thorn (8.78%), whereas red mombin (2.70%) and golden spoon (3.08%) had the lowest. In seeds (Figure 3B), coulter’s acacia (37.71%), Mexican kapok tree (25.01%), elephant ear tree (18.24%), frangipani, (14.44%) and madras thorn (13.86%) had the highest protein content, while bolivar’s bursera had the lowest (3.69%) (Table S1).

Figure 3.

Boxplots showing the protein content (%) in (A) pulp and (B) seeds of fruits consumed by the Military Macaw in the Alto Balsas Basin, Mexico. For each species, boxes indicate the interquartile range (IQR), horizontal lines represent medians, whiskers show minimum and maximum values, and crosses denote mean values.

Significant differences were detected for both pulp (H = 23.64, p < 0.05) and seeds (H = 33.54, p < 0.05). Post hoc comparisons showed that Mexican kapok tree had significantly higher pulp protein content than red mombin and golden spoon (p < 0.05), and that coulter’s acacia differed significantly from bolivar’s bursera in seed protein content (p < 0.05).

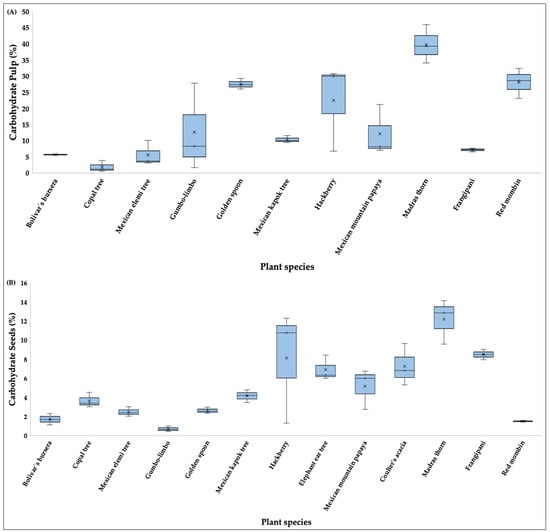

With respect to total percentage of carbohydrates, the species with the highest pulp values (Figure 4A) were Mexican mountain papaya (39.73%), madras thorn (28.01%), golden spoon (27.49%), and hackberry (22.45%), and the species with the lowest was copal tree (1.84%). In seeds (Figure 4B), carbohydrate values were highest in madras thorn (12.18%), hackberry (8.11%), frangipani (8.49%), elephant ear tree (6.91%), and coulter’s acacia (7.22%) and lowest in gumbo limbo (0.68%), bolivar’s bursera (1.79%), and red mombin (1.49%) (Table S1).

Figure 4.

Boxplots showing the carbohydrates content (%) in pulp (A) and seeds (B) of fruits consumed by the Military Macaw in the Alto Balsas Basin, Mexico. For each species, boxes indicate the interquartile range (IQR), horizontal lines represent medians, whiskers show minimum and maximum values, and crosses denote mean values.

There were significant differences were detected in carbohydrate content for both pulp (H = 24.47, p < 0.05) and seeds (H = 33.97, p < 0.05). Post hoc comparisons showed that madras thorn had significantly higher pulp carbohydrate content than copal tree (p < 0.05) and higher seed carbohydrate content than gumbo limbo (p < 0.05).

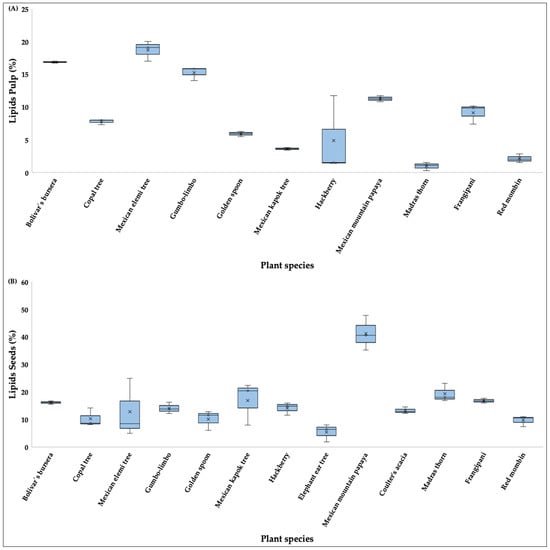

For total percentage of lipid content, the highest values in pulp (Figure 5A) were recorded in Mexican elemi tree (18.73%), bolivar’s bursera (16.88%), and gumbo-limbo (15.28%); Mexican mountain papaya (0.98%), madras thorn (2.15%), red mombin (2.15%), and hackberry had the lowest values (4.90%). In seeds (Figure 5B), lipid content was highest in Mexican mountain papaya (41.20%), madras thorn (19.33%), and Mexican kapok tree (16.91%) and lowest in elephant ear tree (5.42%) and red mombin (9.62%) (Table S1).

Figure 5.

Boxplots showing the lipids content (%) in pulp (A) and seeds (B) of fruits consumed by the Military Macaw in the Alto Balsas Basin, Mexico. For each species, boxes indicate the interquartile range (IQR), horizontal lines represent medians, whiskers show minimum and maximum values, and crosses denote mean values.

Significant differences in lipid contents were observed for both pulp (H = 28.61, p < 0.05) and seeds (H = 25.82, p < 0.05). Post hoc comparisons revealed that madras thorn differed significantly from bolivar’s bursera and Mexican elemi tree in pulp lipid content (p < 0.05), and elephant ear tree differed significantly from Mexican mountain papaya in seed lipid content (p < 0.05) (Figure 5).

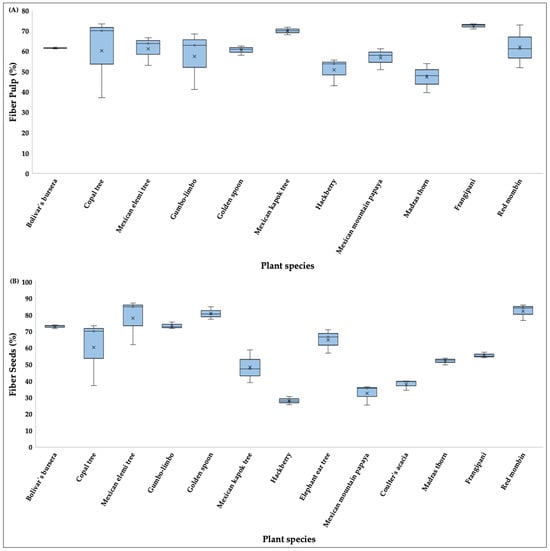

Regarding the total percentage of fiber content in pulp (Figure 6A), the species with the highest values were frangipani, Mexican kapok tree, red mombin, bolivar’s bursera, and frangipani (61 to 73%), whereas the lowest percentage was observed in Mexican elemi tree (37.94%). In seeds (Figure 6B), the highest fiber values occurred in red mombin, golden spoon, and Mexican elemi tree (77–82%), whereas hackberry, Mexican mountain papaya, and coulter’s acacia had the lowest values (27–37%) (Table S1).

Figure 6.

Boxplots showing the fiber content (%) in pulp (A) and seeds (B) of fruits consumed by the Military Macaw in the Alto Balsas Basin, Mexico. For each species, boxes indicate the interquartile range (IQR), horizontal lines represent medians, whiskers show minimum and maximum values, and crosses denote mean values.

Statistical analyses did not show significant differences among species in total fiber content for either pulp (H= 10.59, p > 0.05) and seeds (H = 16.78, p > 0.05).

3.3. Association Between Nutrients and Annual Biological Cycle

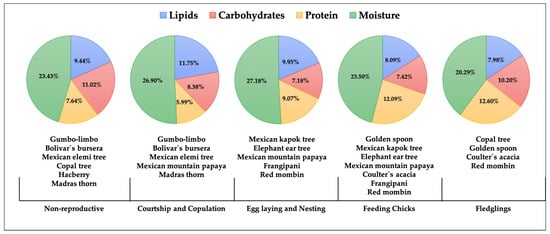

We found seasonal variation in the nutritional composition of the fruit species used by Military Macaws that are available to them. There were distinct shifts in the percentage moisture, total protein, total carbohydrate, and total lipid percentages across the different reproductive and non-reproductive seasons (X2 = 13.28, p < 0.05) (Figure 7). Throughout the non-reproductive season (October–February), the resources available were characterized by a high proportion of moisture (23.43%) and contributions of lipids (9.44%), carbohydrates (11.02%), and protein (7.64%), derived from gumbo-limbo, bolivar’s bursera, Mexican elemi tree, copal tree, hackberry, and madras thorn (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Seasonal variation in the nutritional content (lipids, carbohydrates, proteins, and moisture) of plant resources available to the Military Macaw throughout its annual biological cycle in the Alto Balsas Basin. The non-breeding season extends from October to February; the courtship and copulation period from March to April; egg-laying and nesting from May to June; chick-feeding from July to August; and the fledgling stage from September.

During the reproductive season (February to September) there were 12 plant species available that differed considerably from the non-reproductive season species in nutritional values. The fruits available during the courtship and copulation period had higher moisture (26.90%) and lipid (11.75%) contents and lower carbohydrate (8.38%) and protein (5.99%) levels than those available during the non-reproductive season. Plant species consumed during this phase included gumbo-limbo, bolivar’s bursera, Mexican elemi tree, Mexican mountain papaya, and madras thorn (Figure 7).

During the egg-laying and nesting stages, both moisture (27.18%) and protein (9.07%) contents rose, while lipids (9.95%) and carbohydrates (7.18%) decreased. The food sources were Mexican kapok tree, elephant ear tree, Mexican mountain papaya, frangipani, and red mombin (Figure 7). As chick-rearing progressed, the proportions of proteins (12.09%) and carbohydrates (7.42%) increased, whereas lipid content declined (7.42%). The species used during this phase were golden spoon, Mexican kapok tree, elephant ear tree, Mexican mountain papaya, coulter’s acacia, frangipani, and red mombin (Figure 7). Finally, toward the fledgling period, the plant species available at this stage exhibited higher protein (12.60%) and carbohydrate (10.20%) contents. The plant species consumed were copal tree, golden spoon, coulter’s acacia, and red mombin (Figure 7).

In the case of fiber content, no significant differences were detected among the five stages of the Military Macaw’s annual cycle (X2 = 11.81, p > 0.05), with values ranging from 46.42% to 48.93%.

4. Discussion

The characterization of the nutritional profile of pulp and seeds available in the habitat of the Military Macaw and that they have been documented utilizing in the Alto Balsas Basin reveals marked seasonal differences in the percentage of moisture, protein, carbohydrate, lipid, and fiber content. These patterns are consistent with findings for other tropical birds species with pronounced seasonality, where variation in the chemical composition of pulp and seeds influences foraging opportunities and ecological constraints [17,20,21,22,28,45,46,47,48]. This study was not based on systematic direct observations of feeding by the Military Macaw; rather, all interpretations presented here refer to the nutritional composition of resources that are available (i.e., species that are fruiting) during each period of the year. Despite this limitation, the integration of bromatological analyses with information from the literature, interviews, and occasional field observations of some plant species allows us to infer potential patterns of food use throughout the year. In Neotropical psittacids, both the availability and the quality of food resources are known to be key factors regulating the onset of reproduction, chick survival, and adult body condition [21,46,49,50,51,52].

The semi-quantitative classification of food resources (dominant, supplementary, and occasional), derived from literature records, local interviews, and opportunistic field observations, provides an ecological framework for interpreting the bromatological patterns observed in this study. This classification allows the nutritional profiles of fruits and seeds to be contextualized within the seasonal availability of resources used by Military Macaws in the Alto Balsas Basin.

Dominant species, such as copal tree, bolivar’s bursera, and hackberry, were consistently reported across data sources and seasons, suggesting that they represent core components of the available nutritional landscape throughout the annual cycle. These resources likely contribute to meeting baseline energetic requirements during both non-breeding and breeding periods [13,14,15,17]. Supplementary resources showed more seasonal patterns of use. Species such as Mexican kapok tree, golden spoon, Mexican mountain papaya, madras thorn, and red mombin were available during specific reproductive stages, suggesting that they may provide complementary nutritional inputs during periods of increased physiological demand. For example, protein-rich species coincided with egg-laying and chick-rearing stages, whereas carbohydrate-rich fruits were more frequent during fledgling development [19,20,22,46]. Occasional resources (i.e., those that were recorded less frequently) may function as opportunistic supplements when dominant resources are scarce. This suggests some degree of flexibility in resource use and the importance of maintaining plant species diversity within the landscape [17,19,45,48].

Taken together, these patterns suggest a nutritional mosaic strategy based on the seasonal availability of different food resources, rather than direct evidence of dietary preference or selection [22]. Such patterns should be interpreted cautiously as ecological inferences based on availability rather than direct evidence of Military Macaw preference or differential use of fruits across seasons.

4.1. Nutritional Content in the Non-Breeding Season

Our results suggest that during the non-breeding season, Military Macaw likely relies on pulp and seeds such as hackberry, which is characterized by relatively high protein and carbohydrate content; madras thorn, which provides high moisture and carbohydrate; and bolivar’s bursera, notable for its high moisture and lipid content. This inference is supported by previous reports for the species. Contreras-González et al. [17] reported that the consumption of hackberry and mountain peanut butter tree during the non-breeding season is driven by their elevated concentrations of carbohydrates and lipids. Similarly, Carrillo et al. [28] documented consumption of mangrove leaves by Military Macaw during the non-breeding season, likely primarily related to their lipid content. Similar patterns were found by Puebla-Olivares et al. [22], who showed that Military Macaw in western Mexico select fruits with high energy and moisture content but relatively low protein levels. Comparable dietary strategies have been documented in studies of other psittacids, such as Brown-necked Parrot (Poicephalus fuscicollis) and Budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus), where individuals favor plant resources that are rich in energy and essential fatty acids during non-breeding periods [53,54].

The use of lipid-rich pulp and seeds during the non-breeding season may allow individuals to accumulate the fat reserves necessary to sustain the increased metabolic demands of the coming reproductive season, as documented in Scarlet Macaw (Ara macao), Blue-and-yellow Macaw (Ara ararauna), Rüppell’s Parrot (Poicephalus rueppellii), and Brown-necked Parrot [50,54,55,56]. Meanwhile, carbohydrate-rich resources provide readily available energy for immediate activities such as flight, thermoregulation, and foraging [17,20]. Likewise, fruits and seeds with high moisture content may be an important source of water, particularly in species inhabiting dry tropical environments [17,57], such as Military Macaw in the Alto Balsas Basin region. Taken together, these patterns suggest a foraging strategy characterized by lower protein demand, in which energy and water balance are prioritized [20,28], as has been observed in other species of the genus Ara and other Neotropical psittacids that inhabit seasonally dry habitats [46,50].

4.2. Nutritional Content During the Breeding Season

The nutritional composition of resources available during the breeding season shows higher proportions of pulp and seeds with elevated protein, carbohydrate, and lipid content compared to the non-breeding season. This is consistent with previous reports for the Military Macaw in other localities [17,19,22,28] and aligns with the composition of food resources used by other parrot species [58,59,60].

In the courtship and copulation phase, macaws have been reported to consume plant species rich in carbohydrates and lipids [17,19], such as Mexican mountain papaya, bolivar’s bursera, Mexican elemi tree, and madras thorn. This pattern likely reflects the energetic requirements associated with display behaviors and movements between feeding and breeding sites. This phenomenon has also been described for other psittacids and bird species in the wild and in captivity [20,61,62,63,64]. Carbohydrates enable males to perform persistent displays, while in females they are crucial for sustaining nesting-site assessment and defense prior to ovulation [64].

Lipids, in turn, play a key role in steroid hormone synthesis (testosterone and estradiol), which directly regulate reproductive behaviors [65,66,67]. In captive psittacines, lipids have been documented to enhance courtship, pair-bond formation, sperm quality, and copulatory activity, as reported for Budgerigar, Orange-winged Amazon (Amazona amazonica), and Cockatiel (Nymphicus hollandicus) [68]. In females, they are fundamental for estrogen production, regulating ovarian maturation and preparing the body for egg-laying, as reported for Turquoise-fronted Amazon (Amazona aestiva) [69].

During egg-laying and incubation, our results suggest that the Military Macaw uses pulp and seeds with higher moisture (e.g., Mexican kapok tree, madras thorn) and protein content (e.g., golden spoon, elephant ear tree), consistent with previous reports [17,19,22,28]. This dietary pattern reflects females’ need to maintain their body condition during egg-laying, while providing nutrients essential for egg formation and therefore embryonic development [20,22]. Similar responses have been reported in other psittacids. For example, New Zealand Kaka (Nestor meridionalis) times its reproduction to correspond with the seasonal availability of moist, protein-rich foods [70,71], while in captivity, cockatoos increase egg-laying when diets are supplemented with protein [20].

During egg formation, prior to laying, adequate hydration has been shown to be essential in birds for the synthesis of albumen and eggshell membranes [72], whereas proteins supply the essential amino acids required for the formation of embryonic tissues and enzymes [73,74]. During incubation, female Military Macaws virtually cease foraging to remain at the nest, this period is typically characterized by male-mediated food provisioning [12,15,18,29]. The predominance of moisture and protein-rich fruits and seeds among the plant species fruiting during the incubation period suggests that males may supply moisture-rich fruits and seeds; these may serve as an important water source to maintain water balance, prevent dehydration, regulate body temperature, and support efficient incubation [20,74]. At the same time, proteins help maintain the female’s muscle mass throughout the incubation period, as has been documented in other bird species [75]. Moreover, in various psittacine species, a low-protein diet has been associated with reduced hatching success and lower chick survival [23,76].

During chick feeding, both parents participate in provisioning [12,15,18,29]. Our results show that during this time, Macaws they have fruits available of Mexican kapok tree, frangipsni, and red mombin, which are rich in protein. This aligns with high protein demand by chicks due to their altricial development [20], as documented in Scarlet Macaw, Kakapo (Strigops habroptilus), and Hyacinth Macaw (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus) [46,50,75,76]. In captive Turquoise-fronted Amazon, proteins are known to support muscle growth, feather formation, and immune function [77]. Likewise, captive macaw studies show that chicks fed high-protein diets exhibit greater growth and reduced mortality [20,73].

Finally, during the fledgling stage, our results suggest that the available plants species (including Mexican mountain papaya, bolivar’s bursera, Mexican elemi tree, and madras thorn) have high carbohydrate and protein content. This could help fledglings to meet the energetic and growth demands of developing independence, as reported in other psittacids [73,78]. Proteins provide amino acids for muscle synthesis required for flight, while carbohydrates supply immediate energy for flight and thermoregulation [78].

Fiber content did not differ significantly among the five seasonal stages examined in this study. No direct studies in wild psittacids have evaluated the role of fiber across the annual cycle. However, in poultry such as chickens and turkeys, fiber might improve the performance of chicks at early ages [79]. In captive Blue-and-yellow Macaw, Veloso Jr. et al. [80] reported that fiber supplementation reduced the digestibility of proteins, fats, and metabolizable energy without associated weight gain in females fed high-fiber diets. However, fiber inclusion also lowered fasting glucose, cholesterol, and triglyceride levels, suggesting a positive metabolic effect and potential role in preventing obesity-related disorders in captivity. These findings indicate that moderate fiber intake may contribute to metabolic balance during non-breeding phases, while excessive intake could limit nutrient availability during periods of higher energetic demand, such as reproduction or molting [20,78,79,80].

The incorporation of relative dietary importance categories adds ecological depth to our interpretation of the nutritional data. This multidimensional perspective clarifies seasonal shifts in resource use and underscores the need for conservation strategies that protect not only the most frequently used food trees but also seasonally critical species that support reproduction, chick survival, and fledgling development [78].

Despite the ecological insights gained from this integrative approach, several limitations must be acknowledged when interpreting our findings. Ultimately, although this study provides an integrative view of the nutritional landscape available to the Military Macaw in the Alto Balsas Basin, the absence of systematic, quantitative observations of feeding behavior limits our ability to confirm the proportional contribution of each plant species and obliges us to infer dietary patterns from literature sources, interviews, and occasional field records. In addition, the 13 species analyzed represent only part of the trophic spectrum potentially used by the species, and unassessed resources may also play significant seasonal roles.

Another important limitation is that bromatological values were derived from samples collected across different years and localities, which may introduce nutritional variability driven by phenological or environmental heterogeneity. Furthermore, because seasonal comparisons were conducted using species-level means (three trees per species), the effective sample size per seasonal stage was small, which may limit the statistical power of non-parametric tests such as Friedman and should be considered when interpreting seasonal differences. Moreover, while our interpretation assumes that macaws respond to temporal fluctuations in resource quality, the degree to which nutrient composition directly influences foraging choices remains unresolved in the absence of detailed behavioral data.

Recognizing these limitations highlights the importance of future studies integrating systematic foraging observations, quantitative intake measurements, and broader sampling of plant resources to refine our understanding of the nutritional and ecological drivers that structure the annual diet of this endangered psittacid.

5. Conclusions

This study represents a broader attempt to analyze the nutritional patterns of the Military Macaw’s diet throughout its annual cycle, extending beyond previous studies that focused on a limited number of plant species or on specific reproductive stages [17,19,22,28]. In this context, the present work provides a preliminary overview of the patterns observed in the Alto Balsas Basin, revealing marked seasonal differences in moisture, protein, carbohydrate, and lipid content in the resources available to Military Macaw. These results suggest that different plant species may contribute nutritionally at different times of the year, reflecting potential seasonal associations between resource availability and the macaw’s energetic and physiological demands. Although dietary dependence or active nutrient selection could be driving these patterns, more detailed behavioral and quantitative studies of resource use and relative abundance will be required to confirm those possibilities. While our results were not based on systematic direct feeding observations, the integration of bromatological analyses with information from the literature, interviews, and occasional field records suggest that Military Macaw may adjust its use of available food resources in ways that are consistent with its energetic and physiological requirements.

Taken together, the results of this study highlight the importance of conserving the diversity of tree species in the Alto Balsas Basin, particularly those that provide essential nutrients during critical stages of the reproductive cycle. This study could therefore help provide specific conservation recommendations to support wild populations of the Military Macaw. Furthermore, our findings offer a valuable foundation for future research and conservation actions, especially in the face of habitat alteration and climate change scenarios that could affect both the temporal availability and nutritional quality of resources essential to the species [8,13,14]. Such information is crucial for developing effective management and conservation strategies for this threatened psittacid [21,22,75].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/birds7010002/s1, Table S1: Nutritional content of food resources in the diet of the Military Macaw. Mean values are shown with standard errors (SEs) in parentheses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.A.R.-O., V.L.-H. and V.H.J.-A.; Funding acquisition, F.A.R.-O. and L.D.V.-R.; methodology, F.A.R.-O., J.T.R.-M., C.M.F.-O., V.L.-H. and V.H.J.-A.; software, F.A.R.-O., J.T.R.-M. and V.H.J.-A.; validation, F.A.R.-O., L.D.V.-R., A.M.C.-G., C.M.F.-O. and J.A.R.; formal analysis, F.A.R.-O., V.L.-H., M.P.T.-B., T.L.-M. and V.H.J.-A.; investigation, F.A.R.-O., V.L.-H., J.T.R.-M., M.P.T.-B., T.L.-M., J.A.R. and V.H.J.-A.; resources, F.A.R.-O. and L.D.V.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, F.A.R.-O., A.M.C.-G., L.D.V.-R. and V.H.J.-A.; writing—review and editing, F.A.R.-O., A.M.C.-G., L.D.V.-R. and V.H.J.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by UNAM-PAPIIT IA204324 and IA208124, granted to F.A.R.-O. and L.D.R.V., respectively.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it did not involve experimental manipulation, handling, or disturbance of animals.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and the Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the authorities and residents of the communities of Santa María Cohetzala, Puebla, as well as Papalutla and Xixila, Guerrero, for their hospitality and support during the fieldwork. We are especially grateful to Enrique Lara, Nazario Carrillo, Ángel Aguilar, Juan Esteban Flores, and José Enrique Rosendo for their valuable assistance in field activities. We also extend our sincere thanks to Margarita Moreno Ramírez for her technical guidance and support in the bromatological analyses. We thank anonymous Reviewers 1 and 2 for their valuable comments and suggestions that improved this work. Lynna Kiere for the review of the English language style.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of plant species consumed by the Military Macaw in the Alto Balsas Basin, Mexico.

Table A1.

List of plant species consumed by the Military Macaw in the Alto Balsas Basin, Mexico.

| Family | Plant Specie | Common English Name | Tissue Consumed | Relative Importance | Seasonal Use | Evidence Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anacardiaceae | Cyrtocarpa procera | American plum | Fruits and leaves | Supplementary | B | L, I |

| Spondias purpurea | Red mombin | Fruits | Supplementary | B | I, O | |

| Apocyanacea | Plumeria rubra | Frangipani | Fruits, seeds and latex | Occasional | B | L, I |

| Burseraceae | Bursera bolivarii | Bolivar’s bursera | Fruits and seeds | Dominant | NB | L, I |

| Bursera copallifera | Copal tree | Fruits and seeds | Dominant | BT | L, O | |

| Bursera morelensis | Mexican elemi tree | Fruits and seeds | Supplementary | BT | L, I, O | |

| Bursera simaruba | Gumbo-limbo | Fruits and seeds | Supplementary | NB | L, O | |

| Bursera submoniliformis | Chinese Copal | Fruits and seeds | Supplementary | B | L, I | |

| Cannabacea | Celtis caudata | Hackberry | Seeds | Dominant | NB | L, I, O |

| Caricaeae | Jacaratia mexicana | Mexican mountain papaya | Fruits | Supplementary | B | O |

| Euphorbiaceae | Enterolobium cyclocarpum | Elephant ear tree | Seeds | Supplementary | B | O |

| Fabaceae | Lysiloma divaricatum | Mauto tree | Seeds | Dominant | B | L, I |

| Lysiloma microphyla | Feather bush | Seeds | Supplementary | B | L, I | |

| Mariosousa coulteri | Coulter’s acacia | Seeds | Occasional | B | O | |

| Phitecellobium dulce | Madras thorn | Fruits and seeds | Supplementary | NB | L, I | |

| Malpighiaceae | Byrsonima crassifolia | Golden spoon | Fruits | Supplementary | B | L, I |

| Malvaceae | Ceiba aesculifolia | Mexican kapok tree | Seeds | Dominant | B | L, I |

| Pseudobombax ellipticum | Red silk cotton | Fruits and seeds | Dominant | NB | L, I |

Dominant = Highly recurrent, consistently used resources; Supplementary = Moderate use, relevant during specific periods; Occasional = Rare or sporadic consumption, NB = Non-breeding, B = Breeding, BT = Both, L = Literature, I = Local interviews, O = Opportunistic field observations.

References

- Grajal, A. The Neotropics (Americas). In Parrots. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan 2000–2004, 1st ed.; Snyder, N.P., MaGowan, J.G., Grajal, A., Eds.; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2000; Volume 2004, pp. 98–151. [Google Scholar]

- Cantú-Guzmán, J.C.; Sánchez-Saldaña, M.E. Guía de Identificación de Psitácidos Mexicanos, 1st ed.; Teyeliz, A.C., Ed.; Defenders of Wildlife: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Ortiz, F.A.; Oyama, K.; Ríos-Muñoz, C.A.; Solórzano, S.; Navarro-Sigüenza, A.G.; Arizmendi, M.A. Habitat characterization and modeling of the potential distribution of the Military Macaw (Ara militaris) in Mexico. Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2013, 84, 1200–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. Red List of Threatened Species. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Norma Oficial Mexicana 059 SEMARNAT. Protección Ambiental—Especies Nativas de México de Flora y Fauna Silvestres—Categorías de Riesgo y Especificaciones para su Inclusión, Exclusión o Cambio. Lista de Especies en Riesgo. México. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/profepa/documentos/norma-oficial-mexicana-nom-059-semarnat-2010 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Forshaw, J.M. Parrots of the World, 1st ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2010; p. 336. [Google Scholar]

- Collar, N.J.; Juniper, A.T. Dimensions and causes of the parrot conservation crisis. In New World Parrots in Crisis: Solutions from Conservation Biology, 1st ed.; Beissinger, S.R., Snyder, N.F.R., Eds.; Smithsonian Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 1992; Volume 56, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Reyes, L.D.; Jiménez-Arcos, V.H.; Ramírez-Bastida, P.; Rodríguez-Malacara, J.T.; Contreras-González, A.M.; Sanabria-Urban, O.S.; Rivera-Ortiz, F.A. First record of a breeding site of Ara militaris mexicanus (Ridgway, 1915), Military Macaw (Psittacidae), in the Alto Balsas Poblano Region, Mexico. Check List 2024, 20, 996–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.; Chalif, E. A Field Guide to Mexican Birds and Adjacent Central America, 1st ed.; Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1989; p. 473. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, S.N.G.; Webb, S. A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America, 1st ed.; Oxford University: Oxford, UK, 1995; p. 337. [Google Scholar]

- Iñigo, E.E. Las Guacamayas verde y escarlata en México. Biodiversitas 1999, 25, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Arcos, V.H.; Santa Cruz-Padilla, S.A.; Escalona-López, A.; Arizmendi, M.C.; Vázquez-Reyes, L.D. Ampliación de la distribución y presencia de una colonia reproductiva de guacamaya verde (Ara militaris) en el alto Balsas de Guerrero, México. Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2012, 83, 864–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequi, N. Prospección de la Guacamaya Verde en el Alto Balsas. Programa de Conservación de Especies en Riesgo, Informe Final; Comisión Nacional de Áreas Protegidas: Naucalpan de Juárez, Mexico, 2015; p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Sequi, N. Conservación del Hábitat de la Guacamaya verde en el Alto Balsas. Programa de Conservación de Especies en Riesgo, Informe Final; Comisión Nacional de Áreas Protegidas: Naucalpan de Juárez, Mexico, 2016; p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Loza-Salas, C.A. Patrones de Abundancia, uso de Hábitat y Alimentación de la Guacamaya Verde (Ara militaris) en la Presa Cajón de Peña, Jalisco, México. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad de México, Mexico, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Pérez, L. Evaluación de la Abundancia Poblacional y Recursos Alimenticios para Tres Géneros de Psitácidos en Hábitats Conservados y Perturbados de la Costa de Jalisco, México. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras-González, A.M.; Rivera-Ortiz, F.A.; Soberanes-González, C.; Valiente-Banuet, A.; Arizmendi, M.C. Feeding ecology of Military Macaw (Ara militaris) in a semiarid region of central Mexico. Wilson J. Ornithol. 2009, 121, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez, M.; Marateo, G.; Grilli, P.G.; Pagano, L.; Rumi, M.; Silva-Croome, M. Estado del conocimiento y nuevos aportes sobre la historia natural del guacamayo verde (Ara militaris). Hornero 2012, 27, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Parra-Martínez, S.M.; Muñoz-Lacy, L.G.; Salinas-Melgoza, A.; Renton, K. Optimal diet strategy of a large-bodied psittacine: Food resource abundance and nutritional content enable facultative dietary specialization by the Military Macaw. Avian Res. 2019, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsos, E.A.; Matson, K.D.; Klasing, K.C. Nutrition of the birds in the order Psittaciformes: A review. J. Avian Med. Surg. 2001, 15, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renton, K.; Salinas-Melgoza, A.; De Labra Hernández, M.A.; De la Parra-Martínez, S.M. Resource requirements of parrots: Nest-site selectivity and dietary plasticity of Psittaciformes. J. Ornithol. 2015, 156, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puebla-Olivares, F.; Salcedo-Hernández, J.; Figueroa-Esquivel, E. El habillo (Hura polyandra) en la dieta de la guacamaya verde (Ara militaris). Huitzil 2018, 19, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, J.; Dierenfeld, E.S.; Renton, K.; Bailey, C.A.; Stahala, C.; Cruz-Nieto, J.; Brightsmith, D.J. Nutrition of free-living Neotropical psittacine nestlings and implications for hand-feeding formulas. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2022, 106, 1174–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.E. Nutrition and metabolism. In Avian Energetics and Nutritional Ecology, 1st ed.; Carey, C., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1996; Volume 1, pp. 31–60. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, S.; Kronfeld, D. Veterinary nutrition of large Psittacines. Semin. Avian Exot. Pet Med. 1998, 7, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro, C.J.S.; Bert, E. Principios en la alimentación de psitácidas. RedVet 2011, 12, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Body, D.R.; Powlesland, R.G. Lipid composition of a clutch of kakapo (Strigops habroptilus) (Aves: Cacatuidae) eggs. N. Z. J. Zool. 1990, 17, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, O.R.; Cinta, C.C.; Bonilla, C. Uso de hábitat interanual de la Guacamaya Verde (Ara militaris) en manglar de una zona de conservación ecológica estero El Salado, en el occidente de México. Mesoamericana 2013, 17, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Ortiz, F.A.; Contreras-González, A.M.; Soberanes-González, C.A.; Valiente-Banuet, A.; Arizmendi, M.C. Seasonal abundance and breeding chronology of the Military Macaw (Ara militaris) in a semi-arid region of central Mexico. Neotrop. Ornithol. 2008, 19, 255–263. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, M.F.C.; Galetti, M. Use of forest fragments by blue-winged macaws (Primolius maracana) within a fragmented landscape. Biodiver. Conserv. 2007, 16, 953–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brightsmith, D.J. Parrot nesting in southeastern Peru: Seasonal patterns and keystone trees. Wilson Bull. 2005, 117, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordillo, M.M.; Ávalos, S.V.; Soto, J.C. Flora de Papalutla, Guerrero y de sus alrededores. An. Inst. Biol. 1997, 68, 107–133. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Reyes, L.D.; Jiménez-Arcos, V.H.; SantaCruz-Padilla, S.A.; García-Aguilera, R.; Aguirre-Romero, A.; Arizmendi, M.D.C.; Navarro-Sigüenza, A.G. Aves del Alto Balsas de Guerrero: Diversidad e identidad ecológica de una región prioritaria para la conservación. Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2018, 89, 873–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Nacional del Agua. Available online: https://smn.conagua.gob.mx/es/climatologia/informacion-climatologica/normales-climatologicas-por-estado?estado=gro (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Nava, R.F.; Jiménez, C.R.; Sánchez, M.D.L.L.A. Listado florístico de la cuenca del río Balsas, México. Polibotánica 1998, 9, 1–151. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Nacional del Agua. Available online: https://smn.conagua.gob.mx/es/climatologia/informacion-climatologica/normales-climatologicas-por-estado?estado=pue (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- González, M.; Peñaloza, I. Biomoléculas. Métodos de Análisis, 1st ed.; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Tlalnepantla, Mexico, 2000; pp. 142–156. [Google Scholar]

- Izaki, I. Influence of no protein nitrogen on estimation of protein from total nitrogen in fleshy fruit. J. Chem. Ecol. 1993, 19, 2605–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, D.J.; Bissell, H.A.; O’keefe, S.F. Conversion of nitrogen to protein and amino acids in wild fruits. J. Chem. Ecol. 2000, 26, 1749–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, D.R. Análisis de los Nutrientes de los Alimentos, 1st ed.; Editorial Acribia: Zaragoza, Spain, 1986; pp. 136–138. [Google Scholar]

- Bonet, S.G.R.; Aguilera, L.C.; Villalba, J.B.; Villalba, D.; Rotela, L.A.; Franco, R.B. Caracterización fisicoquímica de la pulpa y almendra de Acrocomia aculeata. Investig. Agrar. 2020, 22, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokal, R.R.; Rohlf, F.J. Biostatistics, 2nd ed.; W.H. Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1987; p. 364. [Google Scholar]

- Zar, H.J. Biostatistical Analysis, 4th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1999; p. 663. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.; Ryan, P. Past: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Matuzak, G.D.; Bezy, M.B.; Brightsmith, D.J. Foraging ecology of parrots in a modified landscape: Seasonal trends and introduced species. Wilson J. Ornithol. 2008, 120, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brightsmith, D.J.; McDonald, D.; Matsafuji, D.; Bailey, C.A. Nutritional content of the diets of free-living scarlet macaw chicks in southeastern Peru. J. Avian Med. Surg. 2010, 24, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilardi, J.D.; Toft, C.A. Parrots eat nutritious foods despite toxins. PLoS ONE 2012, 76, e38293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brightsmith, D.J.; Cáceres, A. Parrots consume sodium-rich palms in the sodium-deprived landscape of the Western Amazon Basin. Biotropica 2017, 49, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.E. Food as a limit on breeding birds: A life-history perspective. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 1987, 18, 453–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renton, K. Diet of adult and nestling Scarlet Macaws in Southwest Belize, Central America. Biotropica 2006, 38, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Kitzberger, T.; Peris, S. Food resources and reproductive output of the Austral Parakeet (Enicognathus ferrugineus) in forests of northern Patagonia. Emu Austral Ornithol. 2012, 112, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brightsmith, D.J.; Hobson, E.A.; Martinez, G. Food availability and breeding season as predictors of geophagy in Amazonian parrots. Ibis 2018, 160, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyndham, E. Environment and food of the budgerigar Melopsittacus undulatus. Aust. J. Ecol. 1980, 5, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symes, C.T.; Perrin, M.R. Feeding biology of the greyheaded parrot, Poicephalus fuscicollis suahelicus (Reichenow), in Northern Province, South Africa. Emu Austral Ornithol. 2003, 103, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.A.; Ragusa-Netto, J. Plant food resources exploited by Blue-and-Yellow Macaws (Ara ararauna, Linnaeus 1758) at an urban area in Central Brazil. Braz. J. Biol. 2014, 74, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, R.G.; Perrin, M.R.; Hunter, M.L.; Dean, W.R.J. The feeding ecology of Rüppell’s Parrot, Poicephalus rueppellii, in the Waterberg, Namibia. Ostrich 2002, 73, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragusa-Netto, J.; Fecchio, A. Plant food resources and the diet of a parrot community in a gallery forest of the southern Pantanal (Brazil). Braz. J. Biol. 2006, 66, 1021–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J. Nutritional requirements. In The Large Macaws: Their Care, Breeding and Conservation, 1st ed.; Abramson, J., Speer, B.L., Thomsen, J.B., Eds.; Raintree Publications: Fort Bragg, CA, USA, 1995; Volume 1, pp. 111–146. [Google Scholar]

- Pepper, J.W. The Behavioral Ecology of the Glossy Black-Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus lathami halmaturinus. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pepper, J.W.; Male, T.D.; Roberts, G.E. Foraging ecology of the South Australian glossy black-cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus lathami halmaturinus). Austral Ecol. 2000, 25, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, C. Avian Energetics and Nutritional Ecology, 1st ed.; Chapman and Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1996; p. 542. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, E.J.; Skinner, N.D. Clinical nutrition of small psittacines and passerines. Semin. Avian Exot. Pet Med. 1998, 7, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidgett, A.L. Nutritional Aspects of Breeding in Birds. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, S.J.; Schoech, S.J.; Bowman, R. Nutritional quality of prebreeding diet influences breeding performance of the Florida scrub-jay. Oecologia 2003, 134, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vleck, C.M.; Brown, J.L. Testosterone and social and reproductive behaviour in Aphelocoma jays. Anim. Behav. 1999, 58, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goymann, W.; Moore, I.T.; Scheuerlein, A.; Hirschenhauser, K.; Grafen, A.; Wingfield, J.C. Testosterone in tropical birds: Effects of environmental and social factors. Am. Nat. 2004, 164, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahaye, S.E.; Eens, M.; Darras, V.M.; Pinxten, R. Testosterone stimulates the expression of male-typical socio-sexual and song behaviors in female budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus): An experimental study. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2012, 178, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millam, J.R. Neonatal handling, behavior and reproduction in Orange-winged amazons and Cockatiels. Int. Zoo Yearb. 2000, 37, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.J.; Christofoletti, M.D.; Blank, M.H.; Duarte, J.M.B. Urofecal steroid profiles of captive Blue-fronted parrots (Amazona aestiva) with different reproductive outcomes. Gen. Com. Endocrinol. 2018, 260, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.R.; Karl, B.J.; Toft, R.J.; Beggs, J.R.; Taylor, R.H. The role of introduced predators and competitors in the decline of kaka (Nestor meridionalis) populations in New Zealand. Biol. Conserv. 1998, 83, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, D.; Mcinnes, K.; Elliott, G.; Eason, D.; Moorhouse, R.; Cockrem, J. The use of a nutritional supplement to improve egg production in the endangered kakapo. Biol. Conserv. 2007, 138, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.K.; Khaliduzzaman, A. Egg formation and embryonic development: An overview. In Informatics in Poultry Production: A Technical Guidebook for Egg and Poultry Education, Research and Industry, 1st ed.; Khaliduzzaman, A., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péron, F.; Grosset, C. The diet of adult psittacids: Veterinarian and ethological approaches. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2014, 98, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, D.C.; Donnan, D.; Jones, P.; Hamilton, I.; Osborne, D. Changes in the muscle condition of female zebra finches Poephila guttata during egg laying and the role of protein storage in bird skeletal muscle. Ibis 1995, 137, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carciofi, A.C. Estudos sobre nutrição de psitacídeos em vida livre: O exemplo da arara-azul (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus). In Ecologia e Conservação de Psitacídeos no Brasil, 1st ed.; Galetti, M., Pizo, M.A., Eds.; Mellopsitacus: Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2002; Volume 1, pp. 63–97. [Google Scholar]

- Cottam, Y.; Merton, D.V.; Hendricks, W. Nutrient composition of the diet of parent-raised kakapo nestlings. Notornis 2006, 53, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carciofi, A.C.; Sanfilippo, L.F.; De-Oliveira, L.D.; Do Amaral, P.P.; Prada, F. Protein requirements for Blue-fronted Amazon (Amazona aestiva) growth. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2008, 92, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrey, D.E.; Allen, M.E.; Baer, D.J. Formulated diets versus seed mixtures for psittacines. J. Nutr. 1991, 121, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Alvarado, J.M.; Jiménez-Moreno, E.; Lázaro, R.; Mateos, G.G. Effect of type of cereal, heat processing of the cereal, and inclusion of fiber in the diet on productive performance and digestive traits of broilers. Poult. Sci. 2007, 86, 1705–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veloso, R.R., Jr.; Sakomura, N.K.; Kawauchi, I.M.; Malheiros, E.B.; Carciofi, A.C. Effects of food processing and fibre content on the digestibility, energy intake and biochemical parameters of B lue-and-gold macaws (Ara ararauna L.–Aves, Psittacidae). J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2014, 98, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.