Abstract

The Guizhou snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus brelichi), a critically endangered primate endemic to China’s Fanjingshan National Nature Reserve, faces severe population decline, with fewer than 850 individuals remaining in the wild. As a high-altitude species adapted to long, snowy winters, its survival depends on behavioral thermoregulation and energy conservation. However, how these behaviors are expressed in captivity remains unclear. To examine behavioral responses to cold conditions, we analyzed the daily activity rhythms and spatial preferences of R. brelichi under winter conditions. Continuous focal observations and instantaneous scan sampling (every 60 s, 07:00–20:00) were conducted across three consecutive snowy days. The monkeys spent most of their time in sleep, with additional time devoted to awake thermoregulatory behaviors. Spatial use was uneven, with outdoor platform most utilized and indoor ground areas least used. Activity showed distinct daily rhythms, with locomotion peaking in the early morning and evening, and foraging concentrated in the late afternoon. Spatial behavior also displayed cyclical patterns, including consistent outdoor platform use and bimodal reliance on indoor foraging and ground areas. These findings provide the first detailed behavioral and spatial profile of R. brelichi in winter captivity, revealing short-term behavioral adjustments to cold conditions and highlighting constraints imposed by enclosure design. The results offer baseline data for improving welfare and enclosure management for this and other cold-adapted primates.

1. Introduction

The Guizhou snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus brelichi), also known as the gray snub-nosed monkey, is a critically endangered primate found only in the high-altitude forests of Guizhou, China. With fewer than 850 individuals remaining in the wild, it ranks among the world’s most imperiled primates, largely due to habitat loss and fragmentation in its native Fanjingshan National Nature Reserve [1,2]. In response, conservation efforts have prioritized captive breeding programs to safeguard the species from extinction [3]. Currently, the ex situ population of the Guizhou snub-nosed monkey remains critically small, consisting of only eight individuals (three males and five females) housed in Guizhou institutions and four individuals (two males and two females) at the Beijing Zoo. Although several copulations and a few surviving infants have been recorded, overall reproductive success is still low. In contrast, the Sichuan snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus roxellana) has 12,000–15,000 individuals, including 227 documented in the international studbook by 2009, with balanced sex ratios and stable multi-generational breeding across numerous Chinese zoos [4,5]. The Yunnan snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus bieti) maintains fewer than 100 captive individuals—mainly in Kunming Zoo and Beijing Zoo—but shows a steadily rising birth rate, while its wild population has expanded to 23 groups totaling about 3845 individuals by 2021 [6]. Compared with these species, the ex situ population of R. brelichi is extremely limited and genetically narrow, emphasizing the urgency of improving husbandry and understanding behavioral adaptation, space use, and welfare to support successful breeding and long-term conservation of this critically endangered primate [7].

A core challenge in ex situ conservation is ensuring that captive individuals retain behaviors essential for survival and reproduction [8,9]. Behavioral rhythms, such as how nonhuman primates divide their time among foraging, resting, socializing, and moving, offer important windows into animal welfare [10,11,12]. Significant deviations from species-typical activity patterns may indicate that the enclosure, care routines, or social environment are suboptimal [13]. In the wild, snub-nosed monkeys adapt their daily activity in response to environmental pressures such as food availability and temperature. For instance, wild R. roxellana (Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys) rest more and move less in winter to conserve energy [14,15]. Likewise, behavioral thermoregulation strategies like sun-basking or huddling are common among cold-climate primates [16]. Yet little is known about how R. brelichi responds behaviorally to cold in captivity, which is a major knowledge gap given its snow-prone native range.

Understanding how R. brelichi adjusts its behavior and space use in winter is not just a welfare concern, it is also central to the biological question of whether this species can maintain adaptive responses in managed care [17,18,19]. This has far-reaching implications for reintroduction success, as R. brelichi lacking natural behavioral flexibility may fail to survive in the wild. Another critical factor is how well the enclosure environment supports species-typical behaviors [20,21]. Enclosure design and enrichment directly shape how R. brelichi engage with their surroundings. Poorly designed or overly barren enclosures can lead to unnatural idleness, stress, or even stereotypic behavior [22]. By contrast, enclosures that provide complexity, such as vertical space, foraging challenges, and cognitive enrichment, support physical health and psychological resilience [23,24]. For example, macaques with access to natural vegetation in their enclosures exhibit foraging and grooming patterns similar to their wild counterparts [25]. These findings reinforce that enrichment and spatial design are not luxuries, but essential components of effective conservation breeding.

In addition to activity budgets, spatial utilization, specifically how zoo animals use different parts of their enclosure, offers critical insights into their preferences, comfort, and environmental needs [26]. Arboreal species like R. brelichi are expected to favor elevated structures over ground-level areas, especially in cold weather [19]. Apes that consistently avoid certain zones (e.g., exposed or cold spaces) may be signaling that the design fails to meet their behavioral or thermoregulatory needs [27]. Ideally, captive animals should use most or all areas of a well-designed enclosure; concentrated use or avoidance patterns can reveal shortcomings in thermal comfort, safety perception, or habitat complexity [26].

Despite the importance of such behavioral and spatial analyses, very little research exists on captive R. brelichi, particularly under naturalistic winter conditions. Most studies on snub-nosed monkeys focus on wild populations of related species like R. roxellana and R. bieti [28,29,30]. The lack of data on how R. brelichi behaves in captivity limits our ability to design appropriate enclosures and care routines. To address this gap, our study provides the first detailed assessment of daily behavioral rhythms and space use in captive R. brelichi under snowy winter conditions. Using high-frequency scan sampling over full daylight cycles, we investigated (i) how captive R. brelichi allocate time across key behavioral categories (e.g., resting, foraging, locomotion, thermoregulation, social behavior); (ii) how they utilize indoor vs. outdoor, elevated vs. ground-level zones of a mixed-environment enclosure during cold weather; and (iii) whether these patterns align with known wild behaviors and expectations from optimal welfare standards. We hypothesized that R. brelichi would exhibit an energy-conserving activity budget characterized by high proportions of sleep and awake thermoregulatory behaviors, together with a clear preference for elevated and sheltered areas and avoidance of cold ground-level zones. By documenting how R. brelichi responds behaviorally to real-world winter conditions in captivity, this research provides a critical evidence base for improving enclosure design, enrichment strategies, and daily husbandry protocols. More broadly, these insights can enhance the long-term viability of captive breeding programs and inform strategies for successful reintroduction to the wild. In the broader impact, as zoos and conservation centers increasingly aim to serve as arks for endangered biodiversity, studies like this one help bridge the gap between welfare science and species recovery. For R. brelichi and other cold-adapted, arboreal primates, understanding behavioral adaptability under captive constraints is key to building sustainable conservation programs that do more than just preserve life, but they prepare it for resilience and return.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects, Housing Conditions, and Husbandry Management

In February 2024, behavioral observations were conducted on a family group of captive R. brelichi housed at the Fanjingshan Rhinopithecus Research Center, a facility specializing in the rescue, breeding, and behavioral research of Guizhou snub-nosed monkeys. The study group represented a single family unit consisting of one adult male (G043, father), one adult female (G047, mother), and one juvenile female (G055) housed together in one enclosure, and two subadult males (G052 and G054) were housed in a second enclosure located adjacent to the adults’ enclosure (Table 1, Figure 1). Although physically separated, the two enclosures were visually and acoustically connected, allowing for continuous social exposure between family members (Figure 1B–E). This subadult enclosure followed the same functional zoning as the adults’ enclosure, with corresponding indoor and outdoor activity areas, including a ground-level foraging station and enrichment structures. A dedicated surveillance camera was installed to monitor this enclosure, ensuring complete coverage of both indoor and outdoor zones. Thus, all five individuals were continuously monitored throughout the study, and behavioral data were recorded independently for each monkey. These monkeys had been maintained in these two separate enclosures for a long period before the experiment as part of the center’s standard management practice to ensure social stability and breeding safety. No individuals were relocated or regrouped for the study. Because all members were closely related and maintained affiliative and hierarchical relationships typical of a family group, the present observations should be regarded as a case study reflecting the behavioral characteristics of this specific social unit rather than the species as a whole. Because R. brelichi remains extremely rare in captivity—only about 12 individuals are currently maintained worldwide—it was not feasible to conduct behavioral observations on multiple independent groups or to separate individuals into single cages for statistical independence. The juvenile female (G055) required continuous parental care, and separating her from the adults would have violated animal-welfare standards and disrupted normal social interactions.

Table 1.

Pedigree of captive Rhinopithecus brelichi used in this study.

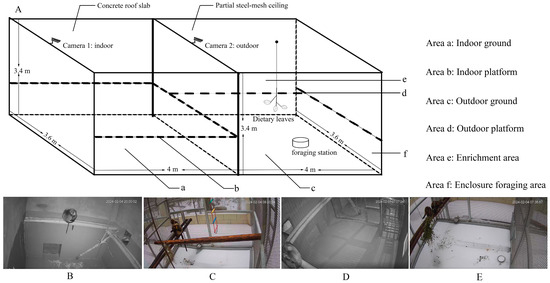

Figure 1.

Enclosure layout, camera placement, and behavioral observation zones for captive Rhinopithecus brelichi. (A) Schematic of the connected indoor (left) and outdoor (right) enclosures showing Camera 1 (indoor, under a concrete roof slab) and Camera 2 (outdoor, under a partial steel-mesh ceiling). The setup included an indoor platform, outdoor platform, enrichment structures (hanging ropes and ladders), and an outdoor ground foraging station where food was placed. These correspond to six observation zones: indoor ground (a), indoor platform (b), outdoor ground (c), outdoor platform (d), enrichment area (e), and foraging station (f). (B) Indoor camera view of the adults’ enclosure showing the indoor platform and surrounding activity area. (C) Outdoor camera view of the adults’ enclosure showing the outdoor platform and associated enrichment structures. (D) Indoor camera view of the subadult enclosure showing the indoor platform and surrounding activity area. (E) Outdoor camera view of the subadult enclosure showing the outdoor platform and associated enrichment structures.

Cleaning occurred between 08:00 and 09:00. Foraging was provided three times daily—morning (08:30): tree leaves, fruits, and vegetables; midday (13:30): tree leaves and grain buns; and afternoon (16:30): tree leaves, fruits, and vegetables. The diet of captive R. brelichi consisted of a variety of natural and supplemental foods designed to meet both nutritional and behavioral needs. Tree leaves (Ligustrum quihoui Carr.) were collected from the surrounding area. Fruits included peaches, apples, pears, plums, oranges, and grapes, while vegetables included eggplant, carrots, lettuce, and stem lettuce. Coarse grains were provided as mixed-grain buns made from corn, soybeans, and buckwheat. Food was offered in two ways: tree leaves were hung on the outdoor platform (see Figure 1A) to simulate natural foraging and encourage arboreal foraging, whereas all other foods were placed in the foraging station on the outdoor ground.

The study was conducted in both indoor and outdoor enclosures (Figure 1A) designed to accommodate the natural behaviors of captive R. brelichi. The indoor enclosure measured approximately 4.0 m × 3.6 m × 3.4 m (length × width × height) and was equipped with wooden climbing poles, crossbars, and a resting platform. The floor was cemented for easy cleaning, and ventilation openings ensured adequate air exchange. The outdoor enclosure measured approximately 4.0 m × 3.6 m × 3.4 m (length × width × height) and was enclosed with metal mesh to allow for exposure to natural light and weather while maintaining safety. It contained elevated perches, a foraging station, and enrichment structures such as hanging ropes and ladders to encourage climbing and play. Both enclosures were connected, allowing for free movement between indoor and outdoor spaces except during cleaning or maintenance periods.

During the study period, environmental conditions were characterized by cold winter weather with continuous snowfall. The ambient temperature ranged from −2 °C to 1 °C. The photoperiod was approximately 11 h of daylight (07:30–18:30). These natural climatic factors were consistent throughout the observation period and likely influenced the monkeys’ behavioral rhythms and space use patterns.

Five individuals were identified based on distinct morphological characteristics such as body size, pelage coloration, and facial features. Age classification followed that by Liang et al. (2001) [31], using morphological and sexual development indicators, including body size, hair color, canine eruption, and secondary sexual traits. Accordingly, individuals aged ≥ 6 years were defined as adults, those aged 3–5 years as subadults, and those aged ≤ 2 years as juveniles. Due to the small sample size, no statistical comparisons were made between sexes.

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

Behavioral data were recorded using a HIKVISION surveillance system (Model DS-2CD3T47WDA-PW, Figure 1A–C) equipped with high-definition dual infrared cameras positioned to ensure complete visibility of all indoor and outdoor activity zones. Instantaneous scan sampling was conducted from 07:00 to 20:00 at fixed 60 s intervals over three consecutive days, following standard ethological procedures. Behavioral categories and coding rules followed the PAE (posture–act–environment) framework as detailed by Yang et al. [32], Cui et al. [33], Yang et al. [34], and were refined into operational definitions for this study (Table 2).

Table 2.

Definitions of main behavioral categories observed in captive Rhinopithecus brelichi (based on the PAE coding system in Yang et al. (2009) [32], Cui et al. (2014) [33], Yang et al. (2023) [34]).

Scan-sampling records were used to estimate time budgets for state behaviors (sustained activities). Short-duration, discrete behaviors (events) such as full copulation/mounting were treated as event behaviors. Event occurrences were recorded as all-occurrence counts (frequency) when observed; where only captured during scans they are reported but were not included in statistical comparisons of % time because instantaneous sampling underestimates event duration and frequency relative to longer states [35]. Video analysis was performed by a single trained observer, who systematically coded behavioral data for all five individuals at each scan point. To ensure data consistency, all behavioral categories and criteria were standardized before formal recording.

To summarize daytime time budgets for the eight behavioral categories, scan-sampling records were first converted to group-level frequencies. For each observation day and each behavior n, we summed across the five monkeys the number of scans in which that behavior was recorded (, where Si is the number of scans in which individual i expressed behavior n). The daily proportion of time allocated to behavior n at the group level was then calculated as , where k indexes the eight behavioral categories (locomotion, sleep, thermoregulation, resting, foraging, grooming, play, and begging). The three daily proportions for each behavior were averaged to obtain the percentages reported in the Results.

An analogous procedure was used to quantify spatial use of the six enclosure zones. For each observation day and each zone n, we calculated Bn as the total number of scans in which any individual was located in that zone (, where Si is the number of scans in which individual i expressed behavior n). The daily proportion of time that the group spent in zone n was then , where k indexes the six zones (indoor ground, indoor platform, outdoor ground, outdoor platform, enrichment area and foraging area). Again, daily proportions were averaged across the three days to provide descriptive percentages of spatial use.

To characterize temporal patterns in behavior and space use, each scan was additionally treated as a time-stamped observation and analyzed using kernel density estimation. For each behavioral category and each enclosure zone, we estimated a circular probability density function over the daytime observation period (07:00–20:00), with time of day on the x-axis and the probability of observing that behavior or zone at a given time on the y-axis. Conditional density contours, highlighting periods with the highest concentration of observations, were generated using the modal.region function in the circular package in R (version 4.4.2). These density curves and contours provide a descriptive visualization of diurnal “peaks” and “troughs” in behavioral and spatial activity. Final plots were formatted and assembled in Origin 2024.

3. Results

3.1. Daily Time Allocation of Behaviors and Spatial Use in Captive R. brelichi Under Snowy Conditions

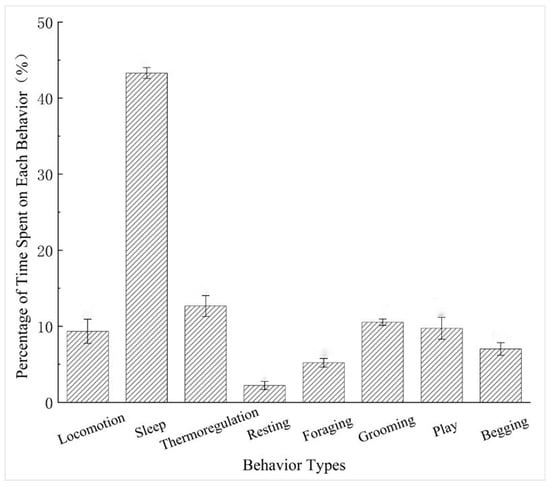

Captive R. brelichi showed clear variation in the proportion of time allocated to different behaviors under snowy conditions (Figure 2). Sleep occupied the largest proportion of time and was much higher than all other behaviors. Thermoregulation, grooming, and play occurred at moderate levels, whereas locomotion, begging, and foraging were less frequent. Resting accounted for the smallest proportion of time.

Figure 2.

Daily time allocation of different behavior types in captive Rhinopithecus brelichi under snowy conditions.

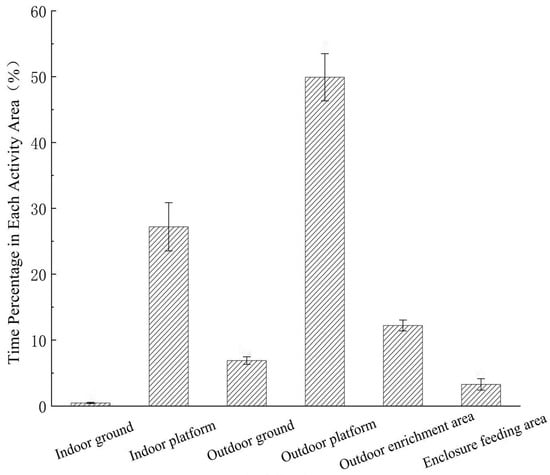

Spatial use varied among different areas of the enclosure (Figure 3). The monkeys used the outdoor platform most frequently, followed by the indoor platform, outdoor enrichment area, outdoor ground, foraging zone, and indoor ground. Use of the indoor platform was lower than the outdoor platform but higher than all other areas. The outdoor enrichment area and outdoor ground were used at similar levels, both more frequently than the indoor ground and foraging zone. Overall, the monkeys showed a strong preference for elevated structures, particularly the outdoor platform, and rarely occupied ground-level spaces.

Figure 3.

Time allocation of spatial utilization in different areas of the enclosure by captive Rhinopithecus brelichi under snowy conditions.

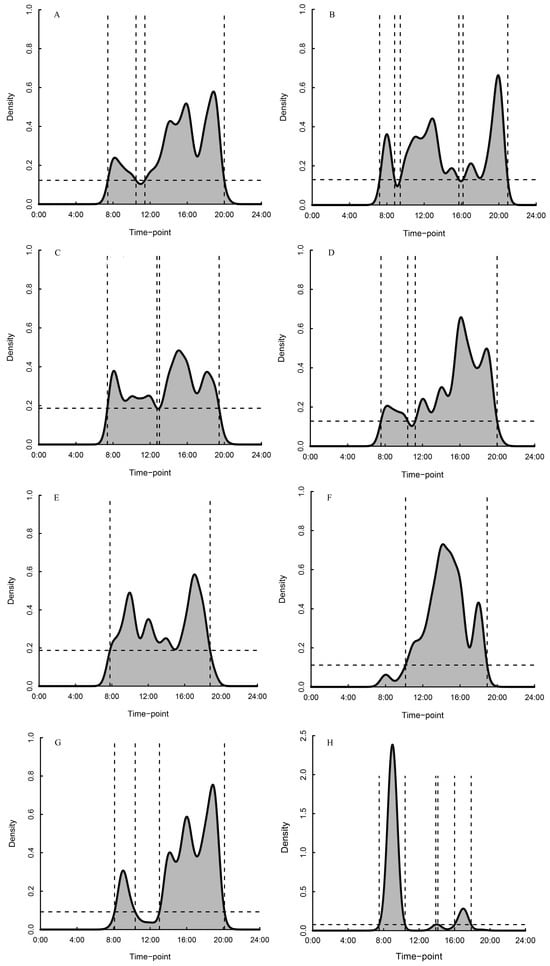

3.2. Daily Activity Rhythms of Captive R. brelichi Under Snowy Conditions

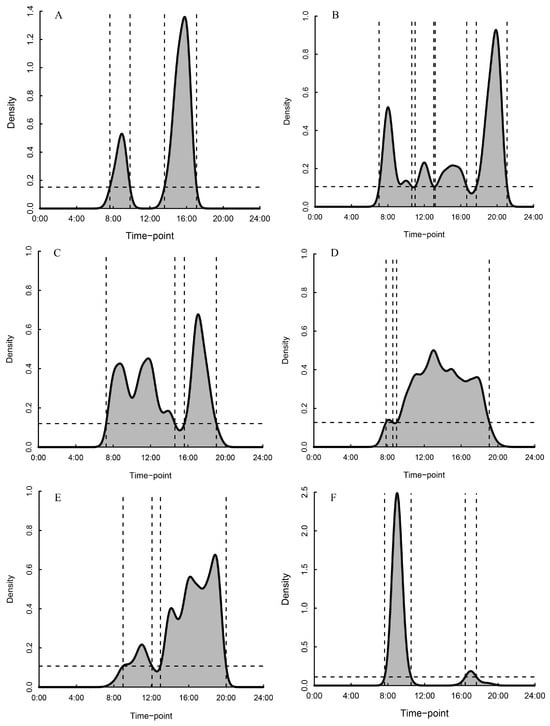

Distinct diurnal patterns were observed across behaviors (Figure 4). Typically, we observed that the locomotion peaked during early morning (07:00–08:00) and again in the early evening (18:00–19:00) (Figure 4A). Sleeping exhibited three peaks: early morning (07:00–08:00), midday (12:00–13:00), and late evening (19:00–20:00) (Figure 4B); thermoregulation showed two peaks: 07:00–08:00 and 14:00–15:00 (Figure 4C); and resting peaked at 08:00–10:00 and again at 15:00–16:00 (Figure 4D). On our assays, we saw that foraging had a prolonged peak period, reaching maximum intensity at 16:00–17:00 (Figure 4E); grooming peaked distinctly in the early afternoon (13:00–14:00) (Figure 4F); playing showed two peaks: morning (08:00–09:00) and early evening (17:00–18:00) (Figure 4G); begging exhibited three consistent peaks: 08:00–09:00, 13:00–14:00, and 16:00–17:00; and mating occurred infrequently and was concentrated during 13:00–14:00 (Figure 4H).

Figure 4.

Daily activity rhythms of captive Rhinopithecus brelichi under snowy conditions. Behavioral density distributions were generated using kernel density estimation for (A) locomotion, (B) sleep, (C) thermoregulation, (D) resting, (E) foraging, (F) grooming, (G) play, and (H) begging. The horizontal dashed line indicates the 50% kernel isopleth (threshold) derived from the modal.region function; values above this line define peak-activity periods. Vertical dashed lines mark the beginning and end of each peak-activity period.

3.3. Spatial Utilization Rhythms of Captive R. brelichi

Clear spatial utilization rhythms emerged across time periods (Figure 5). The indoor ground use followed a bimodal pattern, peaking at 08:00–09:00 and 14:00–16:00, while the indoor platform use showed four peaks: 08:00–11:00, 12:00–13:00, 14:00–16:00, and 18:00–20:00, and the outdoor ground use peaked twice: 08:00–14:00 and 16:00–20:00. The outdoor platform was used consistently throughout the day, indicating it was the most continuously utilized zone, and the outdoor enrichment area showed two primary peaks, 09:00–12:00 and 13:00–20:00, with higher usage during the latter period. The foraging area activity mirrored indoor ground patterns, peaking around foraging times (08:00–09:00 and 16:00–17:00).

Figure 5.

Utilization characteristics of different activity areas in captive Rhinopithecus brelichi under snowy conditions. (A): Indoor ground; (B): indoor platform; (C): outdoor ground; (D): outdoor platform; (E): enrichment; (F): enclosure foraging area. The horizontal dashed line indicates the 50% kernel isopleth (threshold) derived from the modal.region function; values above this line define peak-use periods. Vertical dashed lines mark the beginning and end of each peak-use period.

3.4. Behavior Frequencies Across Different Enclosure Zones

Behavioral frequencies varied across spatial zones (Table 3). The indoor ground was limited to locomotion, foraging, and begging, with locomotion being most frequent (13 ± 6.03 instances). Typically, the indoor platform was dominated by sleeping (612.67 ± 95.84 instances), which was much more frequent than any other behavior. The outdoor ground was primarily used for foraging (241.67 ± 32.17), which exceeded locomotion, playing, and begging in this area. The outdoor platform saw the highest frequency of sleeping behavior (730.33 ± 103.70), while the outdoor enrichment area was mainly used for playing (252.67 ± 37.03). Behavior in the foraging area was overwhelmingly foraging-related (189 ± 19 instances), and more frequent than playing in that zone.

Table 3.

Daily frequencies of behaviors of captive Rhinopithecus brelichi across enclosure areas under snowy conditions.

4. Discussion

In this study, we describe daytime behavior and spatial use in a captive family group of Guizhou snub-nosed monkeys under snowy winter conditions, based on 1 min scan samples from 07:00 to 20:00 over three consecutive days. Our aim is to characterize how this group allocated its daytime activity and space under cold conditions and to generate hypotheses for improving captive management and welfare of R. brelichi.

4.1. Daytime Sleep Patterns in Captive R. brelichi

A central pattern in our data was the high proportion of daytime sleep: over 40% of scans were scored as sleeping, whereas locomotion and foraging were markedly reduced. One plausible interpretation is an energy-saving strategy under cold, snowy conditions, consistent with primates in energetically challenging environments resting more and moving less [15,36]. Daytime foraging accounted for only ~5% of activity, far below the roughly one-third of the day typically devoted to foraging and feeding in wild R. roxellana [14]. However, sleep duration and function in primates remain incompletely understood, and comparative work shows that sleep is highly flexible across ecological and social contexts [36,37,38,39]. In captivity, abundant food, predictable routines, and the absence of predators can permit longer sleep and reduced foraging, but may also reflect low environmental stimulation or mild boredom rather than purely adaptive energy conservation [24,25]. Our findings therefore suggest that high daytime sleep in this group may arise from both thermoregulatory energy saving and captivity-specific conditions, underscoring the value of enrichment that increases cognitively demanding and foraging-like activities.

4.2. Thermoregulatory Behavior in Captive R. brelichi

In cold weather, thermoregulation made up 13% of daily activity, which is through sun-basking, huddling, and clustering in sunlit, sheltered zones. These behaviors mirror those of wild colobines and macaques in winter environments [15]. The findings emphasize that captive enclosures must provide thermally appropriate microhabitats, such as heated indoor spaces and passive solar access. Providing environmental choice is not just a welfare best practice, but it allows monkeys to engage in natural thermoregulatory behaviors, reinforcing autonomy and comfort [40]. Hanya (2004) [15] reported on similar practices applied to captive Japanese macaques in snowy habitats.

4.3. Spatial Use and Preferences in Captive R. brelichi

The monkeys’ strong preference for elevated areas, especially the outdoor platform (~50% usage), underscores their arboreal nature. Ground-level areas, particularly the snow-covered outdoor ground and indoor concrete floors, were largely avoided (<7%). This reinforces the importance of vertical complexity in enclosure design [41,42], a key feature for promoting species-typical behavior and mental stimulation. Additionally, the indoor platform (~27%) served as a refuge during colder hours and foraging times. The ability to move freely between indoor and outdoor areas allowed monkeys to regulate their spatial use, suggesting that flexible access to different microenvironments supports behavioral autonomy and welfare [40].

4.4. Use of Enrichment Areas in Captive R. brelichi

The dedicated enrichment area (~12%) saw moderate use, and a relatively high level of play behavior (~10%) was observed, both encouraging indicators of positive welfare [24]. Notably, the behavioral patterns we observed align with adaptive strategies documented in both wild and captive primates experiencing cold conditions, emphasizing resting and thermoregulation [15]. The reduced foraging and locomotion observed contrast markedly with wild behaviors, highlighting captivity-specific deviations due to readily available food and limited spatial requirements. Consequently, our study suggests further potential in expanding enrichment that includes cognitive challenges, such as training sessions or complex feeders. Enrichment that mimics natural foraging, particularly for folivorous species like R. brelichi, could include fresh browse and seasonal variation to better align with their digestive ecology and behavioral needs [43].

5. Conclusions

This study presents the first detailed description of daytime behavioral patterns and space use in captive R. brelichi under snowy winter conditions. The monkeys spent most of the day sleeping, engaged moderately in thermoregulation, grooming, and play, and showed clear diurnal rhythms in both behavior and enclosure use. They strongly preferred elevated areas, especially the outdoor platform, and rarely occupied ground-level zones when snow was present. However, all observations come from a single closely related family group over a short winter period, and individuals within this social unit are not statistically independent. Our analyses are therefore descriptive and should be interpreted as case-study evidence rather than formal tests comparing multiple enclosures or populations. Despite these limitations, the patterns documented here provide valuable baseline information on behavioral flexibility, thermoregulatory strategies and spatial preferences in captive R. brelichi, and they generate practical hypotheses for refining enclosure design, enrichment and management. Future work with additional groups, facilities, and seasons will be essential to validate and extend these findings for this critically endangered primate.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.-A.T. and Y.T.; Methodology, T.-A.T.; Software, T.-A.T.; Validation, T.-A.T. and W.Y.; Formal Analysis, T.-A.T.; Investigation, T.-A.T. and H.-B.L.; Resources, T.-A.T. and N.Y.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, T.-A.T. and J.-F.L.; Writing—Review and Editing, T.-A.T., G.S., and X.-L.H.; Visualization, T.-A.T.; Supervision, J.-F.L.; Project Administration, N.Y.; Funding Acquisition, X.-L.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Guizhou Science and Technology Support Plan Project ([2024]129 and [2023]188), Construction of Capacity for Ecosystem Optimization and Innovation in Key Ecological Zones of Guizhou Province (QKHFQ [2023]009), and 2024 Central Government Forestry and Grassland Ecological Protection and Restoration Fund (Qiancaizihuan [2023] No. 82).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Huang, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, S.; Yan, Y.; Yan, W.; Meng, B.; Wang, C.; Yang, J.; Ran, J. Difference of gut microbial structure between Rhinopithecus brelichi and Macaca thibetana in Fanjingshan Nature Reserve. Acta Zool. Sin. 2024, 44, 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, S.; Yan, Y.; Yang, W.; Meng, B.; Wang, C.; Yang, J.; Ran, J. The comparative study on intestinal parasites of Rhinopithecus brelichi and Macaca thibetana in Fanjingshan. J. Wildl. Res. 2024, 45, 744–756. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Lv, C.; Liu, X.; Jin, K. Protection of endangered wildlife in China and its prospect. World For. Res. 2014, 27, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z. A comparative analysis of the reproductive fitness of a captive population of golden snub—Nosed monkey. Chin. J. Wildl. 2011, 32, 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sichuan Observation. The Sichuan Snub-Nosed Monkey: How Sichuan Protects a Species as Iconic as the Giant Panda. 2021. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1700060256053107792&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Xinhuanet. Population of the Rare and Endangered Yunnan Snub-Nosed Monkey Exceeds 3300 Individuals. 2023. Available online: https://www.xinhuanet.com/2021-05/01/c_1127401426.htm#:~:text=%E6%96%B0%E5%8D%8E%E7%A4%BE%E6%98%86%E6%98%8E5%E6%9C%88,%E5%8A%A8%E7%89%A9%E7%9B%91%E6%B5%8B%E8%B0%83%E6%9F%A5%E4%B8%AD%E6%8E%A8%E5%B9%BF%E3%80%82 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Zhu, A.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, B.; Huang, F.; Lou, Y.; Zheng, X. Rhythms and time allocation for diurnal activities of captive Sichuan Snub-nosed monkeys. J. Wildl. Res. 2024, 45, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.-C.; Zhou, Q.-H.; Xu, H.-L.; Huang, Z.-H. Diet, food availability, and climatic factors drive ranging behavior in white-headed langurs in the limestone forests of Guangxi, southwest China. Zool. Res. 2021, 42, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, K.; Li, H.; Xu, X.; Duan, W.; Chen, H.; Qiu, G.; Chen, W.; Lu, J.; Ding, C. Ethogram and PAE coding system of Crested Ibis in non-breeding season. Biodivers. Sci. 2024, 32, 24075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, C.K.; Novak, M.A. Environmental enrichment for nonhuman primates: Theory and application. ILAR J. 2005, 46, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yao, Z.; Meng, B.; Ran, J.; Huang, X.; Zhang, M. Daily activity rhythms of Paguma larvata in Fanjingshan National Nature Reserve. J. Mt. Agric. Biol. 2023, 42, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- He, M.; Wang, L.; Yang, G.; Cao, H.; Diao, Y.; Su, H. Rapid assessment of macaque population size using multiple methods and analysis of human–macaque conflicts in county-level areas: A case study of Changshun, Guizhou. J. Mt. Agric. Biol. 2024, 43, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hosey, G.; Melfi, V.; Pankhurst, S. Zoo Animals: Behaviour, Management, and Welfare; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; 643p. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Li, B.; Watanabe, K. Diet and activity budget of Rhinopithecus roxellana in the Qinling Mountains, China. Primates 2007, 48, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanya, G. Seasonal variations in the activity budget of Japanese macaques in the coniferous forest of Yakushima: Effects of food and temperature. Am. J. Primatol. 2004, 63, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFarland, R.; Fuller, A.; Hetem, R.S.; Mitchell, D.; Maloney, S.K.; Henzi, S.P.; Barrett, L. Social integration confers thermal benefits in a gregarious primate. J. Anim. Ecol. 2015, 84, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhong, H.; Ran, J.; Luo, J.; Chen, M.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, S.; Yan, Y.; Huang, X. Analysis of winter diet in Guizhou golden monkey (Rhinopithecus brelichi) using DNA metabarcoding data. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e10893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, S.; Yan, Y.; Yang, W.; Meng, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, J.; et al. Comparative analysis of gut microbiota between wild and captive Guizhou Snub-Nosed Monkey (Rhinopithecus brelichi). Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e70690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, K.; Tan, C.L.; Yang, Y. Altitudinal movements of Guizhou snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus brelichi) in Fanjingshan National Nature Reserve, China: Implications for conservation management of a flagship species. Folia Primatol. 2010, 81, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, P.T.; Réale, D.; Sol, D.; Reader, S.M. Wildlife conservation and animal temperament: Causes and consequences of evolutionary change for captive, reintroduced, and wild populations. Anim. Conserv. 2006, 9, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, F.E.; Greggor, A.L.; Montgomery, S.H.; Plotnik, J.M. The endangered brain: Actively preserving ex-situ animal behaviour and cognition will benefit in-situ conservation. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2023, 10, 230707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, N.; Mason, G. Frustration and perseveration in stereotypic captive animals: Is a taste of enrichment worse than none at all? Behav. Brain Res. 2010, 211, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swaisgood, R.R.; Shepherdson, D.J. Scientific approaches to enrichment and stereotypies in zoo animals: What’s been done and where should we go next? Zoo Biol. 2005, 24, 499–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, L.M.; Pillay, N. A metric-based, meta-analytic appraisal of environmental enrichment efficacy in captive primates. Animals 2025, 15, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaman, M.F.; Huffman, M.A. Enclosure environment affects the activity budgets of captive Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata). Am. J. Primatol. 2008, 70, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Azevedo, C.S.; Cipreste, C.F.; Pizzutto, C.S.; Young, R.J. Review of the effects of enclosure complexity and design on the behaviour and physiology of zoo animals. Animals 2023, 13, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.R.; Schapiro, S.J.; Hau, J.; Lukas, K.E. Space use as an indicator of enclosure appropriateness: A novel measure of captive animal welfare. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 121, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Yang, H.; Fang, Y.; Cheng, K.; Guan, H.; Grueter, C.C.; Xiao, W.; Guo, Q. Associations between forest vertical structure and habitat preferences of black-and-white snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus bieti) in high-elevation environments. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 90, 103269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, N.; Pan, R.; Li, B. A unique case of adoption in Golden Snub-Nosed Monkeys. Animals 2024, 14, 3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.; Xia, W.; Zhu, Y.; Hacker, C.; Wang, X.; Li, D. Historical changes in the distribution of the Sichuan golden snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus roxellana) in Sichuan Province, China. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e11270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Qi, H.-J.; Zhang, S.-Y.; Ren, B.-P. Developmental traits of captive Sichuan Snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus roxellana) at different age stages. Acta Zool. Sin. 2001, 47, 381–387. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Sun, D.Y.; Zinner, D.; Roos, C. Reproductive parameters in Guizhou snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus brelichi). Am. J. Primatol. 2009, 71, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Niu, K.; Luen, T.C.; Yang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y. Behavior Coding and Ethogram of Guizhou Snub-nosed Monkey (Rhinopithecus brelichi). Sichuan J. Zool. 2014, 33, 815–828. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T.; Cui, D.; Niu, K. Current knowledge and conservation strategies of the Guizhou Snub-nosed monkey in Fanjingshan, China. Chin. J. Wildl. 2023, 44, 695–704. [Google Scholar]

- Altmann, J. Observational study of behavior: Sampling methods. Behaviour 1974, 49, 227–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, K.D. Wild primate sleep: Understanding sleep in an ecological context. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2020, 15, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.R. Sleep, sleeping sites, and sleep-related activities: Awakening to their significance. Am. J. Primatol. 1998, 46, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattenborg, N.C.; de la Iglesia, H.O.; Kempenaers, B.; Lesku, J.A.; Meerlo, P.; Scriba, M.F. Sleep research goes wild: New methods and approaches to investigate the ecology, evolution and functions of sleep. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 372, 20160251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattenborg, N.C. Functional implications of sleeping little in the wild. Sleep 2025, zsaf309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maple, T.; Perdue, B.M. Zoo Animal Welfare; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, R. The Behaviour of Lion-Tailed Macaques (Macaca silenus) in Captivity. Ph.D. Thesis, National University of Ireland, Cork, Ireland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, S.R.; Calcutt, S.; Schapiro, S.J.; Hau, J. Space use selectivity by chimpanzees and gorillas in an indoor–outdoor enclosure. Am. J. Primatol. 2011, 73, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hale, V.L.; Tan, C.L.; Niu, K.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Knight, R.; Amato, K.R. Gut microbiota in wild and captive Guizhou snub-nosed monkeys, Rhinopithecus brelichi. Am. J. Primatol. 2019, 81, e22989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.