Abstract

In recent decades, zoos have been increasingly transformed into education centers with the goal of raising awareness about environmental issues and providing environmental education. Probably the simplest and most widespread environmental education program in the zoo is the guided tour. This study therefore aims to test whether a one hour zoo tour has an influence on the participants’ connection to nature and attitude towards species conservation. For this purpose, 269 people who had voluntarily registered for a zoo tour were surveyed before and after the tour. In addition to the regular zoo tour, special themed tours and tours with animal feedings were included. The results show a positive increase in connection to nature and a strengthening of positive attitudes towards species conservation for all tour types. For nature connectedness, in particular, people with an initial high connection to nature benefitted from the special themed tours and the tours, including animal feedings. For attitudes towards species conservation, no difference was found between the tour types. The results prove the positive influence of a very simple environmental education program, even for people with a preexisting high level of connection to nature and positive attitude towards species conservation.

1. Introduction

In our modern society the protection of nature and the environment is becoming increasingly important. An essential approach to addressing these problems and changing people’s behavior is environmental education. In recent decades, zoos have increasingly seen their role as being the education of visitors [1] and, in this way, have evolved from living museums to education and conservation centers [2,3]. Both zoos and zoo visitors see conservation education as a major task for zoos and aquariums [4,5].

Numerous studies have demonstrated the positive effect of zoos in relation to environmental education. For example, a visit to a zoo can be a positive emotional experience that leads to visitors’ interest in learning more about animals [6]. A zoo visit has the potential to positively impact visitors’ understanding of biodiversity [7,8], conservation learning [9], or knowledge [10,11]. Zoos can also have a positive effect on other environmental psychological factors. For example, zoo-related environmental education programs can contribute to an increase in nature connectedness [12,13] or strengthen positive environmental attitudes [14,15]. Behavior change through zoo education has also been demonstrated [16,17] and it was confirmed that the effects achieved by zoos can be sustainable [18]. However, there are also critical studies. For example, methodological weaknesses have been demonstrated in some zoo studies in an environmental education context [19,20]. Moscardo [21] did not find evidence of a positive effect of a wildlife-based tourism experience on conservation awareness. Smith and Broad [22] found that many participants did not show a significant increase in knowledge as a result of a narrated bus tour at the zoo. Other studies have also found that some participants in a zoo environmental education program experienced no increase in knowledge or even experienced a decrease in understanding [9,23]. In addition, a zoo program can lead to misconceptions (false learning) [24]. One possible reason for this could be that many people believe that a visit to the zoo should be a fun and relaxing recreational activity [25].

Despite all of the criticism, the special importance of zoos as environmental education institutions can be illustrated particularly well by the annual visitor numbers. The members of the Association of Zoological Gardens, an association of 71 zoos in German-speaking countries, were visited by more than 43 million people in 2018 [26]. The European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) stated in its annual report for 2017 that its members were visited by 140 million visitors [27]. Globally, it is estimated that there are more than 700 million visits annually and that zoos spend $350 million on conservation projects [28]. However, it must be noted that the number of visitors does not provide any direct information about the general education output [29] and many visitors do not only come to the zoo to learn [25]. Nevertheless, the number of visitors is at least an indicator, since even if only every third person learns something at the zoo, this is already a significant contribution [30].

When educational programs are evaluated in the zoo context, environmental attitudes [31,32], nature connectedness [13,33], environmental knowledge [34,35], or behavior change [16,17] are often examined. Knowledge has long been considered one of the most important factors influencing behavior, but this old paradigm is increasingly being disputed [36]. For example, Moss et al. (2017) discovered that the correlation between knowledge and environmental behavior is small [37], and Otto and Pensini (2017) also confirmed that knowledge has only a small effect on behavior [38].

However, especially for connection to nature and environmental attitudes, there are contradictory results in the zoo context. While some studies found a positive effect of a zoo visit on nature connectedness [12,13,39], other studies could not confirm an increase or even identified a small negative [33,40]. For environmental attitudes, there are also contradictory results in the zoo context. For example, some studies found a positive effect of a zoo visit or environmental education program at the zoo on environmental attitudes [15,41,42]. In contrast, other studies found no change [43,44] or only small effects [31]. Therefore, in this study we will investigate whether a simple environmental education program at a zoo—a one hour zoo tour—has a positive effect on participants’ connection to nature and attitudes toward species conservation.

Although the concept of connection to nature is regularly studied and has now gained a lot of attention, there is no universally accepted definition of the construct. Some researchers focus on the connection of a person’s personality with nature [45]. Others consider, for example, the individual’s emotional connection to nature [46,47]. A widely used concept is the Inclusion of Nature in Self by Schultz [48]. In this concept, the inclusion of nature consists of three layers, which are arranged hierarchically. The cognitive level forms the basis and answers the question of whether a person sees nature as part of him or herself. The affective level deals with the question of whether someone cares about nature and is the prerequisite for the third level; the behavioral level. The behavioral level considers whether someone is motivated to act in the best interest of nature [48]. Despite the various definitions and the resulting different measurement tools, it has been repeatedly demonstrated that the measurement tools are similar and presumably measure the same underlying concept [49,50,51]. Furthermore, many studies show that connection to nature and environmentally friendly behavior are strongly related, and that connection to nature can also motivate people to protect nature [46,52,53,54,55].

Similar to the connection to nature, environmental attitudes also have an influence on environmental behavior. However, there is no consensus on the strength of the relationship. Therefore, depending on the author, attitudes are considered to be a very strong or a moderate factor influencing environmental behavior [56,57,58,59]. Attitudes cannot be directly translated into behavior [60,61], but they are nevertheless a decisive factor influencing behavior [57,58]. There are different approaches to defining the concept of environmental attitude. For example, Schultz (2004) describes environmental attitudes as a collection of a person’s beliefs, feelings, and behavioral intentions about an environmental issue. In the classical view, attitudes consist of three components: a cognitive component that reflects a person’s thoughts toward an attitude or object; an affective component that describes a person’s feelings toward the attitude or object; and a conative component that describes a person’s behavioral intensions toward an attitude or object [62,63,64]. Frequently, environmental attitudes are also summarized as care for nature or concern about environmental problems [64]. Although visitor studies in the zoo context often consider environmental attitudes (e.g., [31,32,42,43,65]), attitudes toward species conservation specifically tend to be neglected. Therefore, in this study we specifically examined the influence of guided zoo tours on attitudes toward species conservation and connection to nature.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure & Participants

The guided tours to obtain the data for this study took place at the Opel Zoo in Kronberg (Germany). These were public tours offered daily (Monday to Friday) at 11 am during the survey period (July to October 2021). Participation in the tours was free of charge, but due to hygiene measures in effect at the time of the study, a non-binding online pre-registration was required. The maximum number of participants was 15 people per tour and only one tour was offered daily. The duration of the tour was approximately one hour and the topics for each tour were published on the Opel Zoo website in advance. Tours were conducted by one of four full-time zoo educators. Tours on similar topics covered the same content, animals and used the same paths in the zoo. For this purpose, the zoo educators used a consistent dialogue. However, minor deviations between zoo educators cannot be completely avoided.

Three different types of tours were conducted for the study. The African mammals tour focused on African mammals, which include, in particular, Rothschild’s giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis rothschildi) and African elephants (Loxodonta africana). In particular, the characteristics of the animals, their habitats, but also their endangerment and threats were addressed. In addition, the housing conditions of these animals in the zoo were discussed. The special topics tours were themed on specific topics (e.g., focus on animals in the European forest; especially the threat to the animals and their habitats but also actions by zoos such as breeding programs and reintroduction into their original habitat) or even individual species (e.g., African penguins (Spheniscus demersus); in particular, their habitat and its endangerment by, for example, guano extraction was addressed, but their hunting and breeding behavior were also included). The feeding tours included any one of the other tours (variable topics) followed by a feeding of animals. Either porcupines (Hystrix indica) or crested capuchins (Sapajus apella) were fed. During the animal feeding, the feeding behavior of the species was explained. The different types of tours were offered on different days, and as such the visitors were only able to attend one particular tour.

At the beginning of the guided tour, all tour participants were briefly informed about the research project and asked to fill out the short questionnaire. The participants were told that participation was voluntary, and people who did not want to fill out a questionnaire were also allowed to take part in the tour. In addition to the questionnaire, each participant was given a printed zoo pen to keep at the end of the tour. After the tour, the second questionnaire was distributed. Only persons of legal age were surveyed.

2.2. Measurement

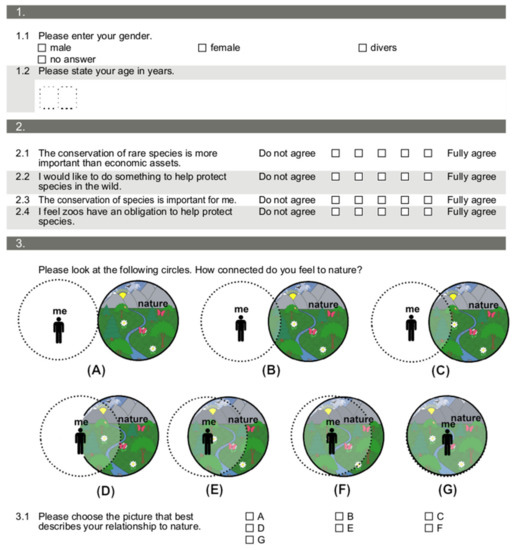

Since the study participants were surveyed spontaneously during a voluntary guided tour, in our experience the questionnaire had to be as short as possible, since people are more willing to participate in short surveys. Therefore, short measurement instruments from other studies were selected to measure nature connectedness and attitudes towards species conservation. The questionnaire can be found in Appendix A, Figure A1.

2.2.1. Measurement of Connection to Nature

Various instruments have been developed over the years to measure connection to nature. For example, the Connectedness to Nature Scale by Mayer and Frantz [46], the Environmental Identity Scale by Clayton [45], or the Nature Relatedness Scale by Nisbet et al. [55]. In this study, the Illustrated Inclusion of Nature in Self Scale (IINS) by Kleespies et al. [66] was used to measure connection to nature. The IINS is an adapted version of the Inclusion of Nature in Self Scale (INS) by Schultz [48]. The original INS consists of seven pairs of circles. One circle is labeled “me”; the other is labeled “nature”. The pairs of circles differ in their degree of overlap, from two separate circles (no connection to nature) to two completely overlapping circles (one with nature). For the evaluation, the pairs of circles were assigned hierarchical numbers from 1 (non-overlapping circles) to 7 (completely overlapping circles). Study participants are asked to select the pair of circles that best describes their own relationship with nature. The IINS is a form of the INS extended by graphic elements with the aim to increase the comprehensibility of the scale. The scale was originally developed and tested for children, but its validity and applicability have also been demonstrated for adults [66].

2.2.2. Measuring Attitudes toward Species Conservation

To assess attitudes toward species conservation, a short scale from Kleespies et al. [14] was used. The scale consists of four items covering the three components of the attitude construct. In addition, the scale has a direct zoo reference, which makes it particularly suitable for this study (Table 1). Participants were asked to rate their agreement with each item on a five-point Likert scale. For the analysis, the mean value was calculated for each person from the four items. Reliability and applicability of the scale have already been confirmed for a similar demographic group [14].

Table 1.

Items used to measure attitudes toward species conservation. The wording of cognitive_1 was slightly changed for this study compared to the original research.

2.3. Analysis

All calculations were performed with IBM SPSS 28. To determine the difference between test point 1 (before the guided tour) and test point 2 (after the guided tour), the Wilcoxon signed ranks test was used after the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test did not show a normal distribution (p < 0.001). The formula from Fritz et al. [67] was used to calculate the effect size.

For the analysis, individuals were divided into three groups according to their initial nature connectedness: IINS scores of 1 to 3 were classified as low nature connectedness, IINS scores of 4 as medium nature connectedness, and IINS scores of 5 and 7 as high nature connectedness [13]. Such a classification was not possible for attitudes toward species conservation, since the Likert scale was only a five-point scale and most study participants already showed very high scores at the beginning. To compare the baseline levels of connection to nature and attitudes toward species conservation between the guided tour types, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used.

3. Results

A total of 269 persons (33.46% male, 64.68% female, 0.37% diverse [diverse is the third official gender option in Germany for non-binary], 1.49% no information) participated in this study. The average age was 41.27 years.

The baseline value for connection to nature was 4.90 ± 1.28 (n = 267). No significant differences were found between the groups according to the classification of the type of tours for connection to nature (p = 0.924; African mammal tours: 4.86 ± 1.25, n = 146; special topic tours: 4.87 ± 1.32, n = 38; feeding tours: 4.95 ± 1.21, n = 58). Attitudes toward species conservation also had a high overall baseline value of 4.49 ± 0.58 (n = 267). No significant differences occurred between types of tours for attitudes towards species conservation (p = 0.487; African mammal tour: 4.44 ± 0.64, n = 146; special topic tour: 4.58 ± 0.44, n = 38; feeding tour: 4.55 + 0.47, n = 60).

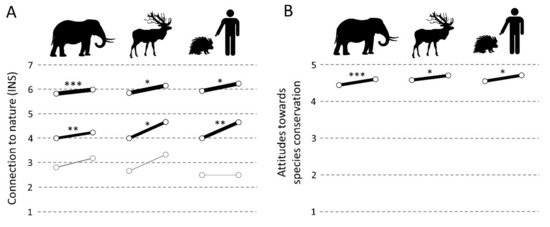

The various zoo tours all triggered increases in connection to nature and attitudes toward species conservation. The influence of the guided tours is shown in Figure 1. Numerical values, exact effect sizes and significance levels can be found in Appendix A, Table A1 and Table A2.

Figure 1.

Means for connection to nature (A) and attitudes toward species conservation (B) before and after zoo tours for the three types of tours. The three rows in A represent the three groups according to baseline connection to nature (high, medium, and low). The elephant is representative of tours focusing on African mammals, the deer is representative of tours with special topics, and the person feeding a porcupine is representative of tours with feeding. Significant changes are marked with * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. The line thickness of the graphs was normalized for each tour type based on the number of participants being represented in the subgroups.

In the group with a high connection to nature baseline, a similarly strong increase is shown for all three guided tour types (African mammal tour: 0.17, n = 79, r = 0.211; special topic tour: 0.30, n = 20, r = 0.243; feeding tour: 0.30, n = 30, r = 0.228). For the group with a low connection to nature, no meaningful result is obtained due to the small sample size for the special topic tour and feeding tour (African mammal tour: n = 16; special topic tour: n = 3; feeding tour: n = 2). In the group with an initial medium connection to nature, there is a higher increase in the guided tours with feedings and in the guided tours with special topics (special topic tour: 0.67, n = 15, r = 0.282; feeding tour: 0.65, n = 26, r = 0.291) than in the guided tours with a focus on African animals (African mammal tour: 0.24, n = 51, r = 0.173). For the attitude towards species conservation, a significant increase is shown for all groups, despite the initial high baseline (between 0.12 and 0.16).

4. Discussion

Most participants in the guided zoo tours in this study showed a very high level of connection to nature even before the tours. Regardless of the type of tour, most participants were already in the upper range in terms of nature connectedness (IINS 5–7). Because of the already high baseline, further increases through environmental education programs are difficult (this is called the ceiling effect). Compared to environmental education programs with students, in which individuals with lower nature connectedness also frequently participate [13,68], persons with low IINS scores were the exception in this study. One possible explanation could be that the individuals voluntarily participated in a guided tour. For this reason, it can be assumed that this group of people is more interested in environmental and animal topics and already has a high connection to nature. Comparable studies often survey school or college students, who have limited, if any, choice to participate because the programs are part of the school curriculum. In addition to visitors with a high connection to nature, zoos should try to encourage people with a low connection to nature to participate in their environmental education programs, for example, by making the programs more attractive to this group of people in particular.

Another explanation for the high initial connection to nature of the participants compared to other studies could be the age of the participants. Many other studies have included students between the ages of 12 and 18 as their target group. At this age, connection to nature is particularly low and only increases again later in life [69]. In this study, the participants were, on average, 41 years old. At this age, connection to nature has usually recovered from the decline during puberty.

The various guided tours show a positive effect on connection to nature, regardless of the topic of the guided tour. Compared to other personality traits that tend to be constant, such as environmental values [70], connection to nature can be influenced by various factors [71]. A particularly important factor that positively influences nature connectedness is the amount of time a person spends in nature [47,48,53,55]. Also, environmental education programs can increase a person’s nature connectedness [13,68,72,73]. The combination of time spent at the zoo, which can be classified as time spent in nature, and the environmental education element of the zoo tour can be considered as factors that positively influence nature connectedness. In this research, however, it is not possible to determine the extent to which the two factors (or their combination) are responsible for the increase in connection to nature. The results of this study are consistent with previous research that has shown the positive effect of a zoo visit on connection to nature [12,13,39].

Differences between the three types of guided tours can be seen for the participants with initial medium connection to nature. Although all tour types show a significant positive increase for the medium group, for the tours with special topics and the tours with feedings the increase is stronger compared with the “regular” Africa tour. This result is consistent with previous zoo research, which showed that individuals with medium connection to nature, in particular, can benefit from small additions to the zoo tour [13]. As such, the feedings and the special themed tours can be seen as a unique experience compared to the regular tour. The increase in connection to nature in the group with an initial high connection to nature is surprising. Compared to other studies where no significant effect was found for short-term interventions [13,68], this study shows a small but significant increase. A possible explanation for this could be that the individuals in other studies were students who attended the environmental education program as part of a school course, while, in this study, the surveyed adults voluntarily participated in the tour in their free time. This means that, in most cases, the reason for the participation of the students was due to extrinsic motivation, while the adult tour participants probably had an intrinsic motivation [74]. This intrinsic motivation may have contributed to a better appreciation of the guided tours and thus to an improvement in the connection to nature.

For the attitudes towards species conservation, the results show that people attending the tours already have very positive attitudes towards species conservation. This result is consistent with previous research: For example, it has been documented that zoo visitors show strong positive environmental attitudes [32] and have more concern for environmental issues compared to the general public [65]. A positive relationship was found between the number of zoo visits in the past and attitudes toward species conservation [14]. An important influencing factor of environmental attitudes is prior experience: Individuals with higher ecological experience at the zoo show more positive attitudes toward conservation compared to individuals with little prior experience [75]. It can be assumed that individuals who voluntarily participate in a guided tour are likely to be among a very interested group which also have prior experience.

Regardless of the type of tour, a significant increase with a small effect size is shown for the attitudes towards species conservation. Since in all three groups the increase is of a similar size, it can be concluded that special topics or feeding of animals do not have an additional positive effect on attitudes toward species conservation. The strengthening of positive environmental attitudes by a visit to a zoo is consistent with previous research. For example, it has been shown that (repeated) environmental education programs at the zoo can improve attitudes toward conservation [76,77]. Even a visit without an additional education program can result in reinforcing positive environmental attitudes [42,78]. In a previous study, it was shown that close animal contact can have a positive effect on attitude [79]. Other studies, on the other hand, have shown that a direct animal encounter has no additional positive effect on environmental knowledge. For example, Whitehouse-Tedd et al. (2021) found that a zoo tour was more likely to increase zoo visitors’ knowledge than an animal encounter, potentially because the tour was longer and thus provided more opportunities for learning [23]. Another study was able to show that there was no difference in environmental behavior improvement between zoo groups with and without animal contact [80]. Our results are consistent with these findings. Thus, we also could not find an additional positive effect of animal feeding on environmental attitudes.

Despite the highly significant increases for both attitudes and connection to nature, it should be noted that the effect sizes in all cases are in the small range (r < 0.3). This means that while there are measurable significant positive effects, these increases are, on average, less than one scale unit. Such a result could be expected for a short intervention, such as the one conducted in this study. In comparable studies in which environmental education programs were evaluated, the effect sizes for connection to nature and environmental attitudes were also in a similar range [68,81].

In summary, this study shows that an environmental education program at the zoo can have a positive impact on the participants’ attitudes towards species conservation and their connection to nature. The results confirm the positive influence of even a very simple and short environmental education program. However, it should not be ignored that these effects are relatively small, although given the duration of the environmental education program, this is not surprising.

5. Limitations

Although the study was conducted with great care, there are some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. Since the study only surveyed people who participated in voluntary zoo tours, a very select group of people was chosen. It can be assumed that this group was, on average, more motivated to learn about environmental issues and to engage with nature. Therefore, the results are not directly transferable to the general population. Another point is that the tours were conducted by different zoo educators. Even though the general themes and routes were set by the zoo, there may still be small variations and differences between educators, which may have affected the tours.

The sample size is also a potential weakness of the study. With 269 persons, the sample was not particularly large. Therefore, only between 30 and 146 participants took part in the different tour types. The lack of a control group (zoo visit without a guided tour) is also a potential weakness of the study.

6. Conclusions

The results of this study show that even a simple and short environmental education program can have a positive effect on the participants’ connection to nature and environmental attitudes. The positive effect especially among those with an initial high connection to nature and very strong positive environmental attitudes shows that even in this group an increase is possible. The findings show that such short environmental education programs are an opportunity to increase nature connectedness and attitudes of people with low baseline values but also have a positive effect on people with already initially high values. It should be noted, however, that the observed effects, although highly significant, are small in terms of effect size. This study provides important evidence that learning at educationally prepared locations, such as zoos in our example, can play an important role in increasing environmental psychological variables, such as nature connectedness and environmental attitudes in people who choose voluntarily to participate in such a program. The impact of such programs on a more diversified audience needs to be investigated in further studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: P.W.D., M.B. and M.W.K.; Data collection: M.B.; Methodology: M.W.K. and P.W.D.; Validation: M.W.K. and P.W.D.; Formal Analysis: M.W.K.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation: M.W.K.; Writing—Review & Editing: M.W.K., P.W.D. and V.F.; Supervision: P.W.D.; Funding Acquisition: P.W.D. and M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partly supported by the Opel-Zoo foundation professorship in zoo biology from the “von Opel Hessische Zoostiftung” and by the Verband der Zoologischen Gärten (VdZ).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and the local rules and regulations. No formal institutional review process was undertaken but ethical considerations were reviewed by the authors and zoo authorities. Since no personal data were collected, only persons of legal age were surveyed, the data were processed anonymously, and the persons were informed that participation in the study was voluntary, the project was deemed of low ethical risk.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors to any qualified researcher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the people who participated in our survey. Special thanks go to the guides at Opel-Zoo in Kronberg, without their help the data collection would not have been possible: Tanja Spengler, Katja Follert-Hagendorff, Alexandra Schneider and Martin Becker.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Results of the Wilcoxon test for connection to nature. The n stands for the sample size in the subgroup. The standard deviation is given in brackets. No standard deviation could be determined for the group with only two persons. Significant changes are marked with * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Table A1.

Results of the Wilcoxon test for connection to nature. The n stands for the sample size in the subgroup. The standard deviation is given in brackets. No standard deviation could be determined for the group with only two persons. Significant changes are marked with * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

| Type of Guided Tour | Initial INS | n | Mean T1 | Mean T2 | Significance Level | Effect Size (r) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

African mammal tour | High | 79 | 5.82 (0.76) | 5.99 (0.78) | *** | p < 0.001 | 0.211 |

| Medium | 51 | 4.00 (0.00) | 4.24 (0.51) | ** | p = 0.003 | 0.173 | |

| Low | 16 | 2.81 (0.40) | 3.19 (1.17) | n.s. | p = 0.102 | ||

Special topics tour | High | 20 | 5.85 (0.99) | 6.15 (0.93) | * | p = 0.034 | 0.243 |

| Medium | 15 | 4 (0.00) | 4.67 (0.90) | * | p = 0.014 | 0.282 | |

| Low | 3 | 2.67 (0.58) | 3.33 (1.53) | n.s. | p = 0.317 | ||

Feeding tour | High | 30 | 5.93 (0.78) | 6.23 (0.82) | * | p = 0.014 | 0.228 |

| Medium | 26 | 4 (0.00) | 4.65 (0.85) | ** | p = 0.002 | 0.291 | |

| Low | 2 | 2.5 | 2.5 | n.s. | p = 1.000 | ||

Table A2.

Results of the Wilcoxon test for attitudes toward species conservation. The n stands for the sample size in the subgroup. The standard deviation is given in brackets. Significant changes are marked with * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001.

Table A2.

Results of the Wilcoxon test for attitudes toward species conservation. The n stands for the sample size in the subgroup. The standard deviation is given in brackets. Significant changes are marked with * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001.

| Type of Guided Tour | n | Mean T1 | Mean T2 | Significance Level | Effect Size (r) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

African mammal tour | 146 | 4.44 (0.64) | 4.60 (0.51) | *** | p < 0.001 | 0.266 |

Special topics tour | 38 | 4.58 (0.43) | 4.70 (0.40) | * | p = 0.028 | 0.252 |

Feeding tour | 60 | 4.55 (0.47) | 4.71 (0.37) | * | p = 0.014 | 0.223 |

Figure A1.

The questionnaire used for the study.

References

- EAZA Executive Office. The Modern Zoo: Foundations for Management and Development. Available online: https://www.eaza.net/assets/Uploads/images/Membership-docs-and-images/Zoo-Management-Manual-compressed.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Rabb, G.B. The evolution of zoos from menageries to centers of conservation and caring. Curator Mus. J. 2004, 47, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabb, G.B. The changing roles of zoological parks in conserving biological diversity. Am. Zool. 1994, 34, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, P.G.; Matthews, C.E.; Ayers, D.F.; Tunnicliffe, S.D. Conservation and education: Prominent themes in zoo mission statements. J. Environ. Educ. 2007, 38, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, K.; McConney, A.; Mansfield, C.F. The role of zoos in modern society—A comparison of zoos’ reported priorities and what visitors believe they should be. Anthrozoös 2014, 27, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Fraser, J.; Saunders, C.D. Zoo experiences: Conversations, connections, and concern for animals. Zoo Biol. 2009, 28, 377–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, A.; Jensen, E.; Gusset, M. Evaluating the contribution of zoos and aquariums to Aichi Biodiversity Target 1. Conserv. Biol. J. Soc. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 29, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, E.A.; Moss, A.; Gusset, M. Quantifying long-term impact of zoo and aquarium visits on biodiversity-related learning outcomes. Zoo Biol. 2017, 36, 294–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, E. Evaluating children’s conservation biology learning at the zoo. Conserv. Biol. J. Soc. Conserv. Biol. 2014, 28, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, S.; Bogner, F.X. Short-and long-term outreach at the zoo: Cognitive learning about marine ecological and conservational issues. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 252–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randler, C.; Kummer, B.; Wilhelm, C. Adolescent learning in the zoo: Embedding a non-formal learning environment to teach formal aspects of vertebrate biology. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2012, 21, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Tabanico, J. Self, identity, and the natural environment: Exploring implicit connections with nature. J. Appl. Soc. Pyschol. 2007, 37, 1219–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleespies, M.W.; Gübert, J.; Popp, A.; Hartmann, N.; Dietz, C.; Spengler, T.; Becker, M.; Dierkes, P.W. Connecting high school students with nature—How different guided tours in the zoo influence the success of extracurricular educational programs. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleespies, M.W.; Montes, N.Á.; Bambach, A.M.; Gricar, E.; Wenzel, V.; Dierkes, P.W. Identifying factors influencing attitudes towards species conservation—A transnational study in the context of zoos. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.H.; Reinhard, E.M.; Vernon, C.L.; Bronnenkant, K.; Heimlich, J.E.; Deans, N.L. Why Zoos & Aquariums Matter: Assessing the Impact of a Visit to a Zoo or Aquarium; Association of Zoos & Aquariums: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, E. Quantifying the impact of wellington zoo’s persuasive communication campaign on post-visit behavior. Zoo Biol. 2015, 34, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemmerly, J.D.; Macfarlane, V. The elements of a consumer-based initiative in contributing to positive environmental change: Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch program. Zoo Biol. 2009, 28, 398–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seybold, B.; Braunbeck, T.; Randler, C. Primate conservation—An evaluation of two different educational programs in Germany. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2014, 12, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellish, S.; Ryan, J.C.; Pearson, E.L.; Tuckey, M.R. Research methods and reporting practices in zoo and aquarium conservation-education evaluation. Conserv. Biol. J. Soc. Conserv. Biol. 2019, 33, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamud, R.; Broglio, R.; Marino, L.; Lilienfeld, S.O.; Nobis, N. Do zoos and aquariums promote attitude change in visitors? A critical evaluation of the american zoo and aquarium study. Soc. Anim. 2010, 18, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G. Understanding visitor experiences in captive, controlled, and noncaptive wildlife-based tourism settings. Tour. Rev. Int. 2007, 11, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Broad, S. Comparing zoos and the media as conservation educators. Visit. Stud. 2008, 11, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehouse-Tedd, K.M.; Lozano-Martinez, J.; Reeves, J.; Page, M.; Martin, J.H.; Prozesky, H. Assessing the Visitor and Animal Outcomes of a Zoo Encounter and Guided Tour Program with Ambassador Cheetahs. Anthrozoös 2021, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spooner, S.L. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Education in Zoos. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of York, York, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J. Visitors’ Perceptions of the Conservation Education Role of Zoos and Aquariums: Implications for the Provision of Learning Experiences. Visit. Stud. 2016, 19, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kögler, J.; Barbosa Pacheco, I.; Dierkes, P.W. Evaluating the quantitative and qualitative contribution of zoos and aquaria to peer-reviewed science. J. Zoo Aquar. Res. 2020, 8, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, M. Report from the EAZA Executive Director; The European Association of Zoos and Aquaria: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gusset, M.; Dick, G. The global reach of zoos and aquariums in visitor numbers and conservation expenditures. Zoo Biol. 2011, 30, 566–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, A.; Esson, M. The educational claims of zoos: Where do we go from here? Zoo Biol. 2013, 32, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, M. Can zoos offer more than entertainment? Curr. Biol. 2015, 25, R391–R394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lukas, K.E.; Ross, S.R. Naturalistic exhibits may be more effective than traditional exhibits at improving zoo-visitor attitudes toward African apes. Anthrozoös 2014, 27, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellish, S.; Pearson, E.L.; Sanders, B.; Litchfield, C.A. Marine wildlife entanglement and the Seal the Loop initiative: A comparison of two free-choice learning approaches on visitor knowledge, attitudes and conservation behaviour. Int. Zoo Yb. 2016, 50, 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, C.M.; Fraser, J.; Schultz, P.W. The value of zoo experiences for connecting people with nature. Visit. Stud. 2008, 11, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.H.; Adelman, L.M. Investigating the impact of prior knowledge and interest on aquarium visitor learning. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2003, 40, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann-Matthies, P.; Kamer, T. The influence of an interactive educational approach on visitors’ learning in a Swiss zoo. Sci. Ed. 2006, 90, 296–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, J.; Heimlich, J.E. Why focus on zoo and aquarium education? Zoo Biol. 2009, 28, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, A.; Jensen, E.; Gusset, M. Probing the Link between Biodiversity-Related Knowledge and Self-Reported Proconservation Behavior in a Global Survey of Zoo Visitors. Conserv. Lett. 2017, 10, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Pensini, P. Nature-based environmental education of children: Environmental knowledge and connectedness to nature, together, are related to ecological behaviour. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 47, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Luebke, J.; Saunders, C.; Matiasek, J.; Grajal, A. Connecting to nature at the zoo: Implications for responding to climate change. Environ. Educ. Res. 2014, 20, 460–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, S. Can a Zoo Visit Contribute to Environmentally Relevant Educational Goals? An Empirical Study on the Possibilities of an Environmental Education Program at the Extracurricular Learning Site Zoo and the Human-Animal Relationship with Regard to Environmentally Relevant Questions. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bayreuth, Bayreuth, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, T. Assessment of Change in Conservation Attitudes through Zoo Education. Ph.D. Thesis, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wyles, K.J.; Pahl, S.; White, M.; Morris, S.; Cracknell, D.; Thompson, R.C. Towards a marine mindset: Visiting an aquarium can improve attitudes and intentions regarding marine sustainability. Visit. Stud. 2013, 16, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukas, K.E.; Ross, S.R. Zoo visitor knowledgeand attitudes toward gorillas and chimpanzees. J. Environ. Educ. 2005, 34, 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Waller, B.M.; Peirce, K.; Mitchell, H.; Micheletta, J. Evidence of public engagement with science: Visitor learning at a zoo-housed primate research centre. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e44680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Environmental identity: A conceptual and an operational definition. In Identity and the Natural Environment: The Psychological Significance of Nature; Clayton, S.D., Opotow, S., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M. The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kals, E.; Schumacher, D.; Montada, L. Emotional Affinity toward Nature as a Motivational Basis to Protect Nature. Environ. Behav. 1999, 31, 178–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W. Inclusion with nature: The psychology of human-nature relations. In Psychology of Sustainable Development; Schmuck, P., Schultz, P.W., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, K.-P. Concepts and measures related to connection to nature: Similarities and differences. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brügger, A.; Kaiser, F.G.; Roczen, N. One for All?: Connectedness to nature, inclusion of nature, environmental identity, and implicit association with nature. Eur. Psychol. 2011, 16, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivos, P.; Aragonés, J.-I. Psychometric properties of the Environmental Identity Scale (EID). Psyecology 2011, 2, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitburn, J.; Linklater, W.; Abrahamse, W. Meta-analysis of human connection to nature and proenvironmental behavior. Conserv. Biol. 2020, 34, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Roczen, N.; Bogner, F.X. Competence formation in environmental education: Advancing ecology-specific rather than general abilities. Umweltpsychologie 2008, 12, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.C.-H.; Monroe, M.C. Connection to nature: Children’s affective attitude toward nature. Environ. Behav. 2012, 44, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Murphy, S.A. The Nature Relatedness Scale. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 715–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinkowski, T.; Reid, A. Reviews of research on the attitude–behavior relationship and their implications for future environmental education research. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Wölfing, S.; Fuhrer, U. Environmental attitude and ecological behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 1999, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, D.S.; Strube, M.J. Environmental attitudes, knowledge, intentions and behaviors among college students. J. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 152, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyl, M.; Díaz, E.M.; Cifuentes, L. Environmental attitudes and behaviors of college students: A case study conducted at a chilean university. RLP 2014, 45, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R. Public Support for Environmental Protection: Objective Problems and Subjective Values in 43 Societies. PS Political Sci. Politics 1995, 28, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 1977, 84, 888–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, Personality and Behavior. Mapping Social Psychology, 2nd ed.; Open University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Breckler, S.J. Empirical validation of affect, behavior, and cognition as distinct components of attitude. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 47, 1191–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Sussman, R. Environmental attitudes. In The Oxford Handbook of Environmental and Conservation Psychology; Clayton, S., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, L.-A.D.; Luebke, J.F.; Clayton, S.; Saunders, C.D.; Matiasek, J.; Grajal, A. Climate change attitudes of zoo and aquarium visitors: Implications for climate literacy education. J. Geosci. Educ. 2014, 62, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleespies, M.W.; Braun, T.; Dierkes, P.W.; Wenzel, V. Measuring connection to nature—A illustrated extension of the Inclusion of Nature in Self Scale. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, C.O.; Morris, P.E.; Richler, J.J. Effect size estimates: Current use, calculations, and interpretation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2012, 141, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, T.; Dierkes, P. Connecting students to nature—How intensity of nature experience and student age influence the success of outdoor education programs. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 937–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.; Rogerson, M.; Barton, J.; Bragg, R. Age and connection to nature: When is engagement critical? Front. Ecol. Environ. 2019, 17, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feather, N.T. Values, valences, and choice: The influences of values on the perceived attractiveness and choice of alternatives. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 68, 1135–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengieza, M.L.; Swim, J.K. The paths to connectedness: A review of the antecedents of connectedness to nature. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 763231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liefländer, A.K.; Fröhlich, G.; Bogner, F.X.; Schultz, P.W. Promoting connectedness with nature through environmental education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2013, 19, 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossack, A.; Bogner, F.X. How does a one-day environmental education programme support individual connectedness with nature? J. Biol. Educ. 2012, 46, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, D. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marseille, M.M.; Elands, B.H.M.; van den Brink, M.L. Experiencing polar bears in the zoo: Feelings and cognitions in relation to a visitor’s conservation attitude. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2012, 17, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Counsell, G.; Moon, A.; Littlehales, C.; Brooks, H.; Bridges, E.; Moss, A. Evaluating an in-school zoo education programme: An analysis of attitudes and learning: Evaluation of zoo education. J. Zoo Aquar. Res. 2020, 8, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, E.L.; Lowry, R.; Dorrian, J.; Litchfield, C.A. Evaluating the conservation impact of an innovative zoo-based educational campaign: ‘Don’t Palm Us Off’ for orang-utan conservation. Zoo Biol. 2014, 33, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiew, S.J.; Hemsworth, P.H.; Melfi, V.; Sherwen, S.L.; Burns, A.; Coleman, G.J. Visitor Attitudes Toward Little Penguins (Eudyptula minor) at Two Australian Zoos. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 626185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacker, C.E.; Miller, L.J. Zoo visitor perceptions, attitudes, and conservation intent after viewing African elephants at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park. Zoo Biol. 2016, 35, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford-Clarke, M.M.; Whitehouse-Tedd, K.; Ellis, C.F. Conservation Education Impacts of Animal Ambassadors in Zoos. JZBG 2022, 3, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liefländer, A.K.; Bogner, F.X. The Effects of Children’s Age and Sex on Acquiring Pro-Environmental Attitudes Through Environmental Education. J. Environ. Educ. 2014, 45, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).