Abstract

The exact role of nitric oxide (NO) in the complex interplay between the host and Trichinella spiralis (T. spiralis) parasite remains uncovered. While much has been revealed about the role of the inducible isoenzyme (iNOS) in different parasitic infections, research is slowly progressing toward understanding the neuronal enzyme (nNOS)-derived impacts on trichinosis. This study aims to clarify the dual nature of (NO) during the enteral phase of experimental trichinosis by examining the participation of both iNOS and nNOS in T. spiralis-infected mice. The experimental design included 48 male Swiss albino mice divided into six groups: (G1) negative control, (G2) infected control, (G3) infected–Albendazole-treated, (G4) infected-infected–L-arginine-treated, (G5) infected–Aminoguanidine-treated, and (G6) infected–7-Nitroindazole-treated. On the seventh day post-infection, the study groups underwent parasitological (adult worm count), histopathological, immunohistochemical, and biochemical assessments. Our results showed that (nNOS) predominance during the enteral phase of trichinosis enhanced parasitic clearance. Conversely, NO produced by iNOS was not essential for worm expulsion but contributed to T. spiralis-mediated enteropathy. Nitric oxide seems to play a puzzling role in T. spiralis infection. While (iNOS) is known for eliminating numerous infections, this is the first example we are aware of where the activity of the neuronal isoform (nNOS) is required in trichinosis.

1. Introduction

Trichinosis is a food-borne zoonotic disease with worldwide distribution. It is caused by a parasitic nematode of the genus Trichinella [1]. The disease holds significant public health implications. It affects approximately ten thousand individuals annually, with a mortality rate of around 0.2% [2]. Trichinella spiralis (T. spiralis) is the most virulent pathogenic species affecting humans. It exhibits a wide global distribution and is mainly transmitted through the consumption of undercooked pork infected with the encysted larvae of the parasite [3].

The Trichinella parasite has a unique life cycle that is accomplished in a single host. The adult worms lodge in the small intestinal enterocytes [4]. There, they release newborn larvae (NBL), which migrate throughout the body until they settle in the skeletal muscles, where they become infective larvae, transforming the host muscle cells into a permanent niche. Although this parasitic occupation is efficient, it does not remain without counter-resistance from the host [5].

During the intestinal phase of infection, the immune response to trichinosis involves both Th1 and Th2 responses. Initially, Th1 responses are induced, followed by a Th2 dominance. In the small intestine, adult T. spiralis worms create an intra-multicellular residence, constituting numerous epithelial cells. As a result, the intestinal mucosa serves as the first natural barrier against the parasite. Consequently, infected epithelial cells initiate the mucosal production of proinflammatory cytokines and mediators, including nitric oxide (NO) [6,7].

Nitric oxide (NO) is a unique signaling molecule with diverse physiological functions. It is a product of L-arginine deamination to L-citrulline by the nitric oxide synthase (NOS) enzyme, a reaction that requires nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) as a cofactor [8]. Three NOS isotypes exist: neuronal nNOS (NOS I), inducible ‘i’NOS (NOS II), and endothelial eNOS (NOS III). Each of these differ in their anatomical distribution, genetic origin, and pathophysiological roles [9]. The isoforms (nNOS) and (eNOS) are constitutively present in many cells and tissues, where they engage in normal physiological responses. The inducible isotype (iNOS) is absent in resting cells. Yet, it is rapidly expressed in response to stimuli like infections or inflammation [10].

Among the calcium-dependent constitutive isoforms, (nNOS) and (eNOS), the neuronal NO synthase is the dominant isoenzyme in the small intestine of rodents and large animals. It plays critical physiological functions in regulating gut motility [11,12]. Because (eNOS) accounts for only a very small part of intestinal (NOS) activity, nNOS’s role may extend beyond motility regulation. Thus, it is possible that (nNOS) in the intestine also functions as the protective (eNOS). As a result, the lack of this key enzyme is associated with impaired nitric oxide production and defective gastrointestinal transit [13].

Many studies have analyzed the protective role of (NO) during Th1-inducing infections. However, fewer have examined its effects in Th2-polarizing infections, such as those involving helminth parasites. To date, the role of (NO) in the immune response against T. spiralis infection remains debatable [14]. Most studies have focused on the effects of the inducible isotype (iNOS) during both the intestinal and muscular phases of trichinosis [7,15,16]. In contrast, literature addressing the impacts of the neuronal isoform (nNOS) on different intestinal parasitic infections remains scarce. Building on this gap, this research is the first to investigate the possible implications of not only (iNOS) but also (nNOS) during the intestinal stage of experimental trichinosis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Parasite

The Trichinella spiralis (T. spiralis) strain was provided by Theodor Bilharz Research Institute (TBRI), Giza, Egypt. The larvae were originally obtained from infected pig muscles at Cairo abattoir in Elbasatin, Egypt. The life cycle was initiated and maintained through successive passages in parasite-free BALB/C mice.

2.2. Animals and T. spiralis Infection

In this experimental study, the sample size was calculated to be 48 mice using OpenEpi at a confidence level of 95% and 80% power of test. The laboratory-bred male Swiss albino mice were of matched age (6–8 weeks) and weight (20–25 g). The mice were selected from the animal facilities of TBRI. They were housed in well-ventilated plastic cages and maintained under controlled lighting (12 h light/12 h dark cycle) and temperature (25 ± 2 °C) with standard pelleted diets and water supplies. To exclude any parasitic infections, routine fecal examination was conducted for all mice, using direct smear analysis and concentration measures for 3 consecutive days [17]. All animal handling, breeding, and experimental procedures were conducted at the Medical Parasitology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, in accordance with national and institutional guidelines for the use and care of laboratory animals.

T. spiralis muscle larvae were recovered from infected mice. The recovery followed the protocol implemented by Dunn and Wright [18]. Briefly, heavily infected muscles were minced and digested in equal volumes of 1% pepsin and 1% concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl) in 1000 mL of distilled water. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 2 h under continuous agitation, using an electric stirrer. The digested product was passed through a 50-mesh/inch sieve to remove coarse particles. Larvae were then collected on a 200 mesh/inch sieve, washed twice, and suspended in 150 mL of tap water in a conical flask. After discarding the supernatant fluid, the larvae in the sediment were counted microscopically using a McMaster counting chamber. Experimental mice were orally infected with approximately 250–300 larvae per mouse. A tuberculin syringe with a blunt needle was used to introduce the infective larvae into the stomachs of mice after a 12 h starvation period.

2.3. Drug Regimen: Dosage Schedule

Albendazole (Bendazol; Sigma Pharmaceuticals Industries, Cairo, Egypt) was provided as a 20 mg/mL suspension and administered orally at a dose of 50 mg/kg/day, starting on the 3rd day post-infection for 3 successive days [19]. L-arginine stock solution (A8094; Sigma Pharmaceutical Industries, Cairo, Egypt) was dissolved in saline to prepare a concentration of 20 mg/mL. Each mouse in the L-arginine-treated group then received an oral dose of 0.1 mL/10 g BW/day (200 mg/kg/day) [20]. L-arginine was administered orally for 7 days before infection [16].

The nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitors, aminoguanidine (AG) and 7-Nitroindazole (7-NI) (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), were administered from day 1 to day 5 post-infection. Aminoguanidine, in the form of aminoguanidine bicarbonate white powder, was dissolved in saline and given orally at 50 mg/kg/day [21]. 7-Nitroindazole was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and administered intraperitoneally at a dose of 50 mg/kg/day [22].

2.4. Experimental Design

The forty-eight (48) mice included in the study were divided into 6 groups (8 mice each) as follows: (G1): negative control group (non-infected, non-treated), (G2): infected control group (infected, non-treated), (G3): infected–Albendazole-treated group, (G4): infected–L-arginine-treated group, (G5): infected–Aminoguanidine-treated group, and (G6): infected–7-Nitroindazole-treated group. Except for (G1), all mice were exposed to T. spiralis infection. On the 7th day post-infection, all mice (48 total) were sacrificed by cervical dislocation under anesthesia. The small intestine of each mouse was removed, opened longitudinally, and washed. A one-centimeter segment (at the junction of the proximal 1/3 and distal 2/3) was stored in 10% formalin for histopathological and immunohistochemical studies. The remaining portions of the small intestine were used to detect adult T. spiralis worms.

2.5. Assessment Measures

2.5.1. Parasitological Analysis

- Isolation and Counting of Adult Worms

First, the washed intestine was cut into 1 cm pieces and incubated at 37 °C in 10 mL of saline for 2 h to allow the worms to detach from the tissue. Next, repeated saline washing was performed until the fluid became clear. Afterward, all fluid was collected and centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 min. Finally, to count adult worms, the supernatant was decanted, and the sediment was examined under a dissecting microscope [23].

2.5.2. Histopathological Analysis

Histopathological examination was performed on small intestinal specimens from different study groups. The samples were fixed in 10% formalin, dehydrated in ascending grades of ethyl alcohol, cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin blocks. Paraffin sections of 5 μm thickness were prepared, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and examined under a light microscope for histopathological evaluation [24]. The extent of the intestinal inflammatory response was scored as follows: grade (+1) was defined as a mild inflammatory infiltrate, with less than one inflammatory cell focus per X100 field; grade (+2) indicated a moderate inflammatory infiltrate, with 1–5 foci/X100 field; grade (+3) corresponded to a large inflammatory infiltrate, with >5 foci/100X field; and grade (+4) reflected an extensive inflammatory infiltrate, characterized by a widespread inflammatory reaction observable throughout the tissue. The degree of inflammatory reaction was assessed by examining 10 fields for each tissue section using a semi-quantitative score [25].

2.5.3. Immunohistochemical Analysis

To investigate intestinal iNOS and nNOS expressions, immunostaining was performed using the avidin–biotin–peroxidase complex (ABC) technique [26]. Briefly, paraffin sections were cut to a thickness of 5 μm on poly-L-lysine-coated slides. The sections were deparaffinized, and endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubating with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 5 min. They were then washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (5 min each time). Next, the sections were placed in a 0.01 mol/l citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and subjected to a 20 min microwave treatment for antigen retrieval. The primary antibodies (rabbit polyclonal anti-iNOS and rabbit polyclonal anti-nNOS antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), in 1:200 dilutions, were added and left overnight at 4 °C. Sections were washed with PBS. They were then incubated with biotin-labelled goat anti-rabbit antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) for 35 min. The peroxidase activity was visualized using a diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate (DAKO Corp, Fremont, CA, USA) applied for 5 min. Negative control slides were prepared by processing sections in the absence of primary antibody [19].

The immunohistochemical reactivities of iNOS and nNOS markers were evaluated in intestinal sections from different study groups in a semi-quantitative manner based on staining extent and intensity. The extent of staining was graded as follows: 0, <5%; 1, >5–25%; 2, >25–50%; 3, >50–75%; and 4, >75%. Meanwhile, the intensity signal was graded as follows: 0: no staining, 1: mild, 2: moderate, and 3: marked staining intensity. A final score was generated by multiplying intensity and extent, yielding a range of 0 to 12. Final scores were further classified into three categories: negative/low (scores 0–4), moderate (scores 5–8), and high expression (scores 9–12) [27]. The iNOS and nNOS immune stains were microscopically assessed in 10 fields for each tissue section using the Leica Qwin 500 image analyzer computer system (Cambridge, UK).

For both histopathological and immunohistochemical analyses, biopsy specimens were randomized, coded, and evaluated blindly.

2.5.4. Biochemical Analysis

Serum samples were obtained from all treated and control mice on the 7th day post-infection. The samples were collected and stored at −20 °C until further biochemical analysis.

- Assessment of serum nitric oxide (NO) levels

Serum NO levels were measured using a colorimetric nitric oxide assay kit (BioVision Incorporated, CA, USA, Cat. No. K262–200) following the instructions of the manufacturer. Prepared standards, a sample blank, and 85 μL of each serum sample were added to a microtiter plate. The assay consisted of two steps. First, 5 μL of each nitrate reductase mixture and enzyme cofactor were added to the sample and standard wells. The plate was incubated for 60 min to convert nitrate to nitrite. After adding 5 μL of the enhancer, the plate was incubated for 10 min. In the second step, 50 μL of each Griess reagent (R1 and R2) was added to generate a deep purple compound from nitrite. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm.

- Assessment of the serum cytokines, IFN-γ, and TNF-α

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to assess the serum concentrations of IFN-γ and TNF-α cytokines. The Mouse ELISA Kit (Quantikine, USA R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN 55413, USA) was used for the quantitative determination of IFN-γ (Cat. No. MIF00) and TNF-α (Cat. No. MTA00B-1) concentrations in serum samples, according to the supplier’s protocol.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The data collected were tabulated and analyzed using SPSS version 25 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Quantitative data were described using mean, range, and standard deviation (SD). ANOVA F-test was performed to compare more than two groups for normally distributed quantitative variables. [28]. Post hoc analysis was performed for pairwise comparisons. The Bonferroni correction was applied to control the overall rate of false positives [29]. Significance was set at p values < 0.05. Treatment efficacy was calculated using the following equation: Efficacy (%) = 100 × (mean worm number in controls minus mean worm number recovered in treated mice)/mean worm number in controls [30].

2.7. Ethical Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by The Scientific Research Ethical Committee of The Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University (ZU–IACUC/3/F/38/2023).

3. Results

3.1. Parasitological Results

Adult Worm Count

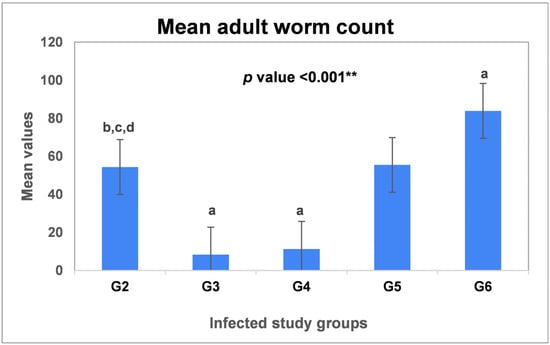

Our parasitological analysis revealed that the highest worm burden was observed in the 7-Nitroindazole-treated group (G6), with a significant increase in the mean worm count by a percentage of (54.2%) compared to the infected untreated group (G2) (P5 < 0.001 **, Table 1). However, treatment of mice with aminoguanidine (G5) did not induce a significant change in the adult worm count (P4 = 0.92, p > 0.05) (Table 1). The current study has also assessed the efficacy of albendazole and L-arginine drugs. Based on the findings in Table 1, the highest reduction (%) in worm count was observed in the albendazole-treated group (G3, 84.6%), followed by the L-arginine-treated group (G4, 79.1%), yet without a statistically significant difference between the two groups (P3 = 0.19, p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Trichinella spiralis adult worm counts in the intestinal sections of the infected groups.

As shown in Figure 1, the lowest burdens of T. spiralis were recorded in (G3) and (G4).

Figure 1.

Mean adult worm counts of T. spiralis in the intestinal sections of the infected groups. G2: Infected untreated group; G3: Infected–Albendazole-treated; G4: Infected–L-arginine-treated group; G5: Infected–Aminoguanidine-treated group, and G6: Infected–7-Nitroindazole-treated group. Data were analyzed using ANOVA with a post hoc analysis. Note: “a” indicates a significant difference vs. (G2) (p < 0.001 **), while “b” indicates a significant difference vs. (G3) (p < 0.001 **), “c” indicates a significant difference vs. (G4) (p < 0.001 **) and “d” indicates a significant difference vs. (G6) (p < 0.001 **).

3.2. Histopathological Results

3.2.1. Histopathological Features

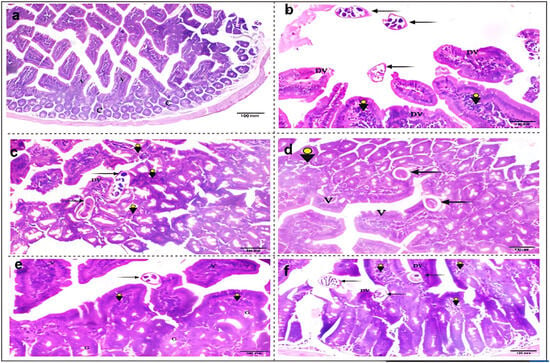

Sections from the small intestinal segments of the infected, untreated group (G2) revealed characteristic features of T. spiralis infection, with variable numbers of adult worms embedded in-between the villi or free in the lumen. Infection with T. spiralis also induced different pathological changes in the intestinal tissue, which showed villous degeneration, and dense lymphocytic infiltrations, as shown in Figure 2b. While albendazole treatment notably reduced worm burden, it did not resolve these pathological changes. The intestinal sections of (G3) still demonstrated villous damage, and extensive inflammatory infiltrates (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Photomicrographs of the histopathological changes in small intestinal sections from different study groups. (a) G1: non-infected, non-treated mice with regular intact villi (V), and normal crypt architecture (C) (H&E, X 100); (b) G2: T. spiralis infected untreated mice, showing multiple irregular degenerated villi (DV). Three worms could be seen free inside the intestinal lumen (black arrows), with dense villous lymphocytic infiltrations (arrowheads); (c) G3: infected–albendazole-treated group, exhibiting marked loss of the normal intestinal architecture with extensive cellular infiltrations (arrowheads). Two partially necrotic worms could be seen, as a result of therapy (black arrows); (d) G4: infected–L-arginine-treated mice, with restoration of regular villous architecture (V), moderate lymphocytic inflammatory infiltration (arrowhead) and partially degenerated worms (black arrows). (e) G5: infected–aminoguanidine-treated mice, showing regular villous structure (V) and goblet cells (G), with mild inflammatory infiltrations (arrowheads). An intact T. spiralis worm could be seen atop the villi (black arrow); (f) G6: infected–7NI-treated mice, displaying irregular, degenerated villi (DV), with infestation by three T. spiralis worms (black arrows), and moderate villous lymphocytic infiltrations (arrowheads) (H&E, X 200).

A significant improvement in pathological features was observed following L-arginine treatment in (G4). This group exhibited a restoration of normal villous architecture and a reduction in cellular inflammation (Figure 2d). Despite the worm burden, a slight improvement in intestinal architecture was recorded in (G5) after aminoguanidine administration. This treatment induced a resolution in cellular inflammation after selectively inhibiting the (iNOS) isotype (Figure 2e). The reported increase in parasitic load following 7-NI treatment contributed to several sequelae in the intestinal sections of treated mice (G6). These pathological changes included villous damage and degeneration, inflammatory infiltrations, and loss of normal tissue architecture (Figure 2f).

3.2.2. Inflammatory Response Score

The present work has assessed the degree and intensity of inflammatory infiltration changes in the intestinal sections of the infected study groups. According to the data presented in Table 2, more than 60% (62.5%) of the infected untreated mice (G2) exhibited severe inflammation. Notably, the extent of inflammation worsened following albendazole treatment. In (G3), 75% of the mice showed extensive infiltration changes. Furthermore, none (0%) of the treated animals showed mild or moderate inflammatory scores. In contrast, after L-arginine treatment, the intensity of the inflammatory response reduced compared to (G2); however, this difference was not statistically significant (p2 = 0.60, p > 0.05).

Table 2.

Extent of inflammatory infiltration changes in the intestinal sections of the infected groups.

Our study has reported a notable improvement in the extent of inflammation after selective inhibition of the nitric oxide synthase isotypes, iNOS and nNOS, in (G5) and (G6), respectively. None of the aminoguanidine-treated mice (0%) exhibited severe inflammation. Also, after 7-NI treatment, half of the treated mice (50%) showed mild inflammatory infiltrations. Such observed reductions in the degree of inflammation were found significant for (G5) (p3 = 0.014), yet insignificant for (G6) (p4 = 0.06), as depicted in Table 2.

3.3. Immunohistochemical (IHC) Results

The current study has assessed the distribution of the nitric oxide synthase isoenzymes, iNOS, and nNOS, in the intestinal sections of different study groups.

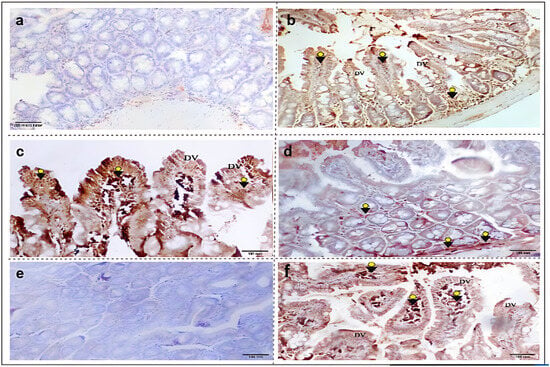

3.3.1. iNOS Immunohistochemical Expression

According to our results, T. spiralis infection induced a marked elevation in the intestinal expression of (iNOS) isoenzyme. Furthermore, a stronger immunostaining of the marker was observed in (G3) following albendazole treatment (Figure 3b and Figure 3c, respectively). Yet, a reduced distribution of (iNOS) was observed in the L-arginine-treated mice (G4) (Figure 3d). After its selective blockage by aminoguanidine, no immunoreactivity was reported for the (iNOS) isoenzyme in (G5). Conversely, an intense marker expression was noticed following the 7NI treatment (Figure 3e and Figure 3f, respectively).

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical expressions of the iNOS isoenzyme in small intestinal sections from different study groups. (a) G1: non-infected, non-treated mice with negative iNOS immunoreactivity. (b) G2: T. spiralis infected untreated mice, showing degenerated villi (DV) with strong positive iNOS immunostaining (arrowheads). (c) G3: infected–albendazole-treated group, featuring degenerated villi (DV) with marked iNOS expression (arrowheads). (d) G4: infected–L-arginine-treated mice, showing focal minimal iNOS immunoreactivity (arrowheads). (e) G5: infected–aminoguanidine-treated mice, exhibiting negative iNOS expression. (f) G6: infected–7NI-treated mice, showing villous degeneration (DV) and damage with marked (iNOS) distribution (arrowheads) (iNOS IHC, X100).

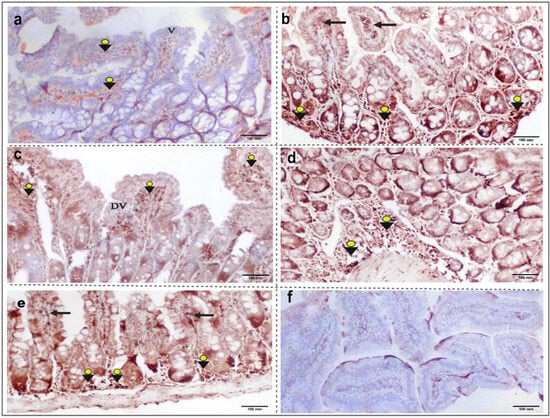

3.3.2. nNOS Immunohistochemical Expression

Our work would be the first to demonstrate the distribution of the (nNOS) isoenzyme in the intestinal sections of T. spiralis-infected mice. According to the findings depicted in Figure 4, the parasite induced a strong expression of the marker inside the villi and in the submucosal layer (Figure 4b). Yet, moderate (nNOS) expression was noticed in the intestinal sections of the albendazole-treated mice (Figure 4c). Treatment of the infected mice with L-arginine induced an extensive intestinal distribution of (nNOS) (Figure 4d). However, after the selective inhibition of the isotype using 7-NI, the treated mice exhibited negative (nNOS) immunostaining (Figure 4f).

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical expression of the nNOS isoenzyme in small intestinal sections from different study groups. (a) G1: non-infected, non-treated mice, showing weak nNOS immunostaining (arrowheads), and normal villous architecture (V). (b) G2: T. spiralis infected untreated mice, with a strong positive nNOS immunoreactivity in the submucosal layer (arrowheads) and inside villi (black arrows). (c) G3: infected–albendazole-treated group, showing focal villous degeneration (DV) with moderate positive (nNOS) immunohistochemical staining (arrowheads). (d) G4: infected–L-arginine-treated mice, featuring marked submucosal (nNOS) expression (arrowheads). (e) G5: infected–aminoguanidine-treated mice, with strong (nNOS) immunoreactivity in the submucosal layer (arrowheads) and inside villi (black arrows). (f) G6: infected–7NI-treated mice, showing negative (nNOS) immunohistochemical staining (nNOS IHC, X100).

3.3.3. iNOS and nNOS Immunohistochemical Scores

According to Table 3, all the control negative mice (G1) tested negative for (iNOS), while 25% showed moderate (nNOS) reaction in their intestines. Notably, T. spiralis infection induced a significant (p < 0.05) increase in both (iNOS) and (nNOS) levels in the infected mice. Furthermore, based on our data, albendazole treatment induced a strong intestinal (iNOS) expression; 75% of the treated mice in (G3) showed an intense distribution of the marker. In contrast, L-arginine treatment primarily elevated the (nNOS) isoenzyme, with more than 80% (87.5%) of (G4) mice exhibiting extensive (nNOS) immunostaining. The selective inhibition of iNOS and nNOS isotypes using aminoguanidine and 7-NI drugs in (G5) and (G6), respectively, led to a significant (p < 0.05) reduction in their intestinal levels, compared to the infected untreated mice (G2).

Table 3.

Immunohistochemical expressions of iNOS and nNOS isoenzymes in the intestinal sections of different study groups.

3.4. Biochemical Results

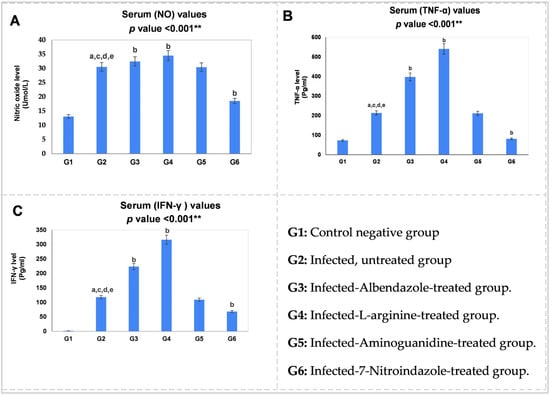

The proinflammatory mediators (NO, TNF-α, and IFN-γ) were assessed in serum samples of the study groups using the ELISA assay. As shown in Figure 5, T. spiralis infection induced a notable elevation in the expression of these mediators in the sera of the infected mice compared to the control negative group (G1) (p < 0.001 **).

Figure 5.

Statistical pairwise comparisons of the serum values of the proinflammatory mediators during the enteral phase of trichinosis: (A) serum nitric oxide (NO, Umol/L); (B) serum tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α, Pg/mL); (C) serum interferon-gamma (IFN-γ, Pg/mL). Data were analyzed using ANOVA with a post hoc analysis. Note: “a” indicates a significant difference vs. (G1) (p < 0.001 **), while “b” indicates a significant difference vs. (G2) (p < 0.001 **), “c” indicates a significant difference vs. (G3) (p < 0.001 **), “d” indicates a significant difference vs. (G4) (p < 0.001 **), and “e” indicates a significant difference vs. (G6) (p < 0.001 **).

Based on our data, L-arginine induced the highest serum production of the proinflammatory agents, NO (34.51 Umol/L), TNF-α (540.23 Pg/mL) and IFN-γ (316.04 Pg/mL), followed by albendazole therapy. In contrast, among infected intestinal groups, selective (nNOS) blockage in (G6) resulted in the lowest serum levels of these mediators (Table 4), a statistically significant reduction (p < 0.001 **) compared to the infected untreated group (G2) (Figure 5). Aminoguanidine-induced reduction, however, was not significant compared to (G2) (p > 0.05).

Table 4.

Serum values of the proinflammatory mediators (NO, TNF-a and IFN-γ) during the enteral phase of infection.

4. Discussion

In human trichinosis, cellular immunity develops a mixed Th1/Th2 immune response, characterized by the initial development of an early Th1 response, followed by a subsequent predominance of Th2 [31]. While there is wide evidence supporting the use of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in experimental trichinosis [19,32,33], a notable gap exists in reports investigating the impacts of the neuronal isoform (nNOS) on Th2-inducing infections. To address this gap, we assessed, for the first time, the functional roles of both iNOS and nNOS isoenzymes in experimental T. spiralis infection.

Our parasitological analysis showed that the highest reduction (%) in worm burden was observed in the albendazole-treated group (G3, 84.6%) (Table 1). In support, Attia et al. [19] reported a significant reduction in the adult count of T. spiralis following albendazole treatment, with a reduction rate of 94.2%. The anti-parasitic effects of albendazole are attributed to the drug’s inhibition of microtubule polymerization through its selective binding to beta-tubulin monomer of the parasite, which is considered a primary target [34]. Albendazole also acts by causing glucose deprivation in adult intestinal cells, leading to defective nutrient absorption and ultimately resulting in starvation of the adult worms [35]. Our use of the nitric oxide donor, L-arginine, in (G4) resulted in a significant reduction (79.1%) in the mean worm count, as shown in Table 1. This finding aligns with Wang et al. [36], who reported lethal effects of exogenous (NO) donors on adult T. spiralis worms. However, in contrast to these results, Fadl et al. [16] observed a significant increase in the number of T. spiralis worms in the intestinal sections of mice treated with L-arginine.

In this investigation, the use of aminoguanidine, a selective iNOS inhibitor, did not significantly change adult worm count (p4 = 0.92, p > 0.05) (Table 1). On the other hand, selective (nNOS) inhibition using 7-NI induced a significant increase in the parasitic load in (G6). The mean worm count was (83.88), as shown in Figure 1. Based on these data, it appears feasible to suggest that the neuronal enzyme (nNOS) is the main isotype responsible for eliminating T. spiralis adult worms, whereas the inducible isoenzyme, iNOS, was not essential for the expulsion of the parasite. Findings that support the protective role of (nNOS) during the enteral phase of trichinosis are consistent with those of Li et al. [37]. They proved that NO production by (nNOS) was necessary for controlling Giardia intestinalis infection.

Since nNOS-expressing neurons in the enteric nervous system are involved in regulating gut motility and smooth muscle tone within the gastrointestinal tract [38], we suggest that the anti-parasitic action reported for the neuronal isoenzyme (nNOS) could be related to its role in eliciting intestinal hypermotility, which further contributes to the clearance of infection. This observation confirms the study by Li et al. [39], who regarded nNOS-induced hypermotility as a host defense strategy against giardiasis.

Recently, Liu et al. [40] investigated the role of programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) in eosinophilia during Trichinella spiralis infection in mice. According to them, PD-1-deficient mice exhibited delayed expulsion of adult worms and increased muscle larva burdens compared to wild-type mice following infection. Their findings demonstrated a positive role for PD-1 in the recruitment of eosinophils, suggesting their involvement in host defense against helminth infection.

Sex-related differences are prominent in gastric motility functions both in health and disease. In their research, Balasuriya et al. [41] confirmed the cyclic and sexually dimorphic effect of NOS activity in the female mouse colon, which could be due to the genomic effects of estrogen. They showed that altered colonic motility during the estrus cycle correlates with fluctuating levels of sex steroid hormones in female C57Bl/6 mice.

Despite the notable reduction in worm burden reported in the current study after albendazole treatment, the pathological changes were not resolved. Specifically, several pathological features were observed in the intestinal sections of (G3) mice, including villous degeneration, and extensive inflammatory cellular infiltrations (Figure 2c). To explain this finding, we propose that albendazole may contribute to this unresolved pathology by inducing (iNOS) expression in the intestinal sections of the treated mice, which could promote inflammatory responses. Supporting this, Table 2 shows that 75% of (G3) mice exhibited extensive inflammatory infiltration changes, further suggesting that immune protection, while beneficial, may also drive tissue damage. In their research, Ricken et al. [42] have also confirmed the role of albendazole in augmenting the inflammatory response in human hepatic alveolar echinococcosis. The authors indicated that albendazole treatment activates the host immune system by reducing the immunosuppressive functions of the Echinococcus multilocularis parasite.

Unlike the reported impacts of albendazole, the use of L-arginine has resulted in a notable improvement in the pathological features in (G4) mice, with restoration of normal villous architecture and a reduction in the extent of inflammatory infiltration, as shown in Figure 2d. These findings can be attributed to reasons including, on the one hand, the drug’s notable induction of the neuronal isoform (nNOS) in the intestinal sections of the treated mice, as indicated by more than 80% (87.5%) of (G4) mice showing extensive (nNOS) immunostaining (Table 3). On the other hand, a reduced distribution of (iNOS) was observed in the L-arginine-treated group (Figure 3d). Consistent with these observations, Carbajosa et al. [43] reported that L-arginine supplementation improved clinical profile and survival in Trypanosoma cruzi-infected mice.

Following the selective inhibition of the (iNOS) isotype with aminoguanidine, our study demonstrated that iNOS activity contributes to intestinal tissue inflammation and damage. Its inhibition led to a slight improvement in intestinal tissue architecture and a reduction in cellular inflammation, as shown in Figure 2e. None of the (G5) mice exhibited extensive inflammatory changes (Table 2). These findings align with the work of Kołodziej-Sob-ocińska et al. [44], who used aminoguanidine to prevent intestinal mucosal damage and cytotoxicity in T. spiralis-infected mice. In contrast, selective inhibition of the (nNOS) isoenzyme using 7-NI indicated a protective role for nNOS; its inhibition resulted in the emergence of parasite-induced changes, including villous damage and degeneration, inflammatory infiltrations, and loss of normal tissue architecture in (G6) mice (Figure 2f). Supporting this, Abdel Aziz and Elsayed [22] similarly recorded pathological features for the 7-NI drug in the intestinal sections of the Heterophyes heterophyes infected and treated dogs, such as loss of intestinal tissue structure with marked lymphocytic and eosinophilic cellular infiltrations. These findings suggest that while iNOS activity can be detrimental during trichinosis, nNOS exerts a protective effect on intestinal tissues during the enteral phase of infection.

Based on biochemical results, T. spiralis infection induced a significant elevation in the serum concentrations of the proinflammatory mediators (NO, TNF-α, and IFN-γ) (p < 0.001 **, Figure 5). Notably, such an increase in the (Th1) agents corresponded to a notable rise in the intestinal (iNOS) and (nNOS) immunoreactivities in the infected mice, as shown in Table 3. Consistent with these findings, Ishikawa et al. [6] reported that during the intestinal phase of trichinosis, there is an initial predominance of the (Th1) response, with an elevation of its related cytokines. Furthermore, Frydas et al. [45] indicated that T. spiralis infection enhances proinflammatory cytokine (TNF-α) induction from the first day post-infection, persisting throughout infection. The same study demonstrated increased (IFN-γ) expression in the serum of infected mice.

One intriguing finding of this work is that L-arginine-induced nitric oxide production matched strong neuronal marker (nNOS) expression (Figure 4d), despite minimal (iNOS) immunoreactivity (Figure 3d). In contrast, Fadl et al. [16] reported that L-arginine induced significantly high (iNOS) distribution in the intestinal sections of T. spiralis-infected mice. Another interesting result in this study is that aminoguanidine-induced reduction in proinflammatory mediators was insignificant compared to the infected non-treated group (G2) (p > 0.05). On the other hand, selective blockage of (nNOS) caused a significant reduction in the serum levels of the immune markers (NO, TNF-α, and IFN-γ) in (G6) (p < 0.001 **, Figure 5). Collectively, these data indicate that during the intestinal phase of infection, there is another important source for (NO) production: the (nNOS) isoenzyme. This supports our hypothesis regarding the predominance of the neuronal isoform during the enteral phase of experimental trichinosis.

5. Conclusions

The observations of the current work challenge the conventional paradigm that Th1-immune responses evolved to combat intracellular microorganisms, while Th2-type responses target extracellular pathogens. Instead, based on our findings, what is more important than the cellular location of the parasite is the source and magnitude of nitric oxide production, as well as the type of infected tissue. Notably, the study highlights the opposing roles of nitric oxide synthase isoforms during the enteral phase of experimental trichinosis. While (nNOS) proved protective, (iNOS) acted as a central mediator for pathogenesis.

Building on these insights, this research has several strengths. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first study to investigate the distribution and potential impacts of the neuronal isoenzyme (nNOS) in experimental T. spiralis infection. Second, after selective inhibition of (iNOS) and (nNOS) isotypes with aminoguanidine and 7-NI, respectively, we observed negative immunostaining for both markers in the intestinal sections of the treated mice. This confirms the specificity of the reagents and markers used. Finally, we demonstrated the dual nature of nitric oxide in experimental trichinosis, with one aspect being beneficial and the other detrimental.

Study Limitations

One limitation of the current study is the inclusion of only male mice in the experimental design. Gender-related differences are prominent in gastric motility functions both in health and disease. Gender bias impacts the Th1/Th2-dominant response and has been implicated in the nitrergic pathway in rodent models of gastroparesis and gut motility.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.O.; methodology, M.O. and A.E.-t.; formal analysis and investigations, M.O. and A.E.-t.; original draft preparation, M.O.; review and editing, M.O. and S.M.; supervision, G.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by The Scientific Research Ethical Committee of The Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University (ZU–IACUC/3/F/38/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Heba Abdelal, Assistant Director of Operations at LIS Cross-National Data Center in Luxembourg, for her valuable feedback and assistance with the statistical analysis of data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| T. spiralis | Trichinella spiralis |

| NBL | Newborn larvae |

| AG | Aminoguanidine |

| 7-NI | 7-Nitroindazole |

| DV | Degenerated villi |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| HCL | Hydrochloric acid |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NOS | Nitric oxide synthase |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| nNOS | Neuronal nitric oxide synthase |

| IHC | Immunohistochemical |

| ABC | Avidin–biotin–peroxidase complex |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| DAB | Diaminobenzidine |

| ELISA | Enzyme linked immune-sorbent assay |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| Th1 | T helper-1 |

| Th2 | T helper-2 |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-gamma |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death 1 |

References

- Liu, R.D.; Wang, Z.Q.; Wang, L.; Long, S.R.; Ren, H.; Cui, J. Analysis of differentially expressed genes of Trichinella spiralis larvae activated by bile and cultured with intestinal epithelial cells using real-time PCR. Parasitol. Res. 2013, 112, 4113–4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milton, A.A.P.; Das, S.; Ghatak, S.; Srinivas, K.; Priya, G.B.; Angappan, M.; Sen, A. Seroepidemological investigation of Toxoplasma gondii and Trichinella spp. in pigs reared by tribal communities and small-holder livestock farmers in Northeastern India. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozio, E. World distribution of Trichinella spp. infections in animals and humans. Vet. Parasitol. 2007, 149, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofronic-Milosavljevic, L.; Ilic, N.; Pinelli, E.; Gruden-Movsesijan, A. Secretory products of Trichinella spiralis muscle larvae and immunomodulation: Implication for autoimmune diseases, allergies, and malignancies. J. Immunol. Res. 2015, 2015, 523875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottstein, B.; Pozio, E.; Nöckler, K. Epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and control of trichinellosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 22, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, N.; Goyal, P.K.; Mahida, Y.R.; Li, K.F.; Wakelin, D. Early cytokine responses during intestinal parasitic infections. Immunology 1998, 93, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, C.E.; Paterson, J.C.; Wei, X.Q.; Liew, F.Y.; Garside, P.; Kennedy, M.W. Nitric oxide mediates intestinal pathology but not immune expulsion during Trichinella spiralis infection in mice. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 4229–4234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bredt, D.S.; Snyder, S.H. Isolation of nitric oxide synthetase, a calmodulin-requiring enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 682–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Feron, O. Nitric oxide synthases: Which, where, how, and why? J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 100, 2146–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, J.; Keselman, A.; Li, E.; Singer, S.M. Macrophages expressing arginase 1 and nitric oxide synthase 2 accumulate in the small intestine during Giardia lamblia infection. Microbes Infect. 2015, 17, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.W.; Wang, H.; Rozenfeld, R.A.; Huang, W.; Hsueh, W. Type I nitric oxide synthase (NOS) is the predominant NOS in rat small intestine. Regulation by platelet-activating factor. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1999, 1451, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palásthy, Z.; Kaszaki, J.; Lázár, G.; Nagy, S.; Boros, M. Intestinal nitric oxide synthase activity changes during experimental colon obstruction. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 41, 910–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, X.W.; Wang, H.; De Plaen, I.G.; Rozenfeld, R.A.; Hsueh, W. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase (NOS) regulates the expression of inducible NOS in rat small intestine via modulation of nuclear factor kappa B. FASEB J. 2001, 15, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.; Abdelal, H.O. Nitric oxide in parasitic infections: A friend or foe? J. Parasit. Dis. 2022, 46, 1147–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żeromski, J.; Boczoń, K.; Wandurska-Nowak, E.; Mozer-Lisewska, I. Effect of aminoguanidine and albendazole on inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) activity in T. spiralis-infected mice muscles. Folia Histochem. Cytobiol. 2005, 43, 157–159. [Google Scholar]

- Fadl, H.O.; Amin, N.M.; Wanas, H.; El-Din, S.S.; Ibrahim, H.A.; Aboulhoda, B.E.; Bocktor, N.Z. The impact of l-arginine supplementation on the enteral phase of experimental Trichinella spiralis infection in treated and untreated mice. J. Parasit. Dis. 2020, 44, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giarcia, L.S.; Bruckner, D.A. Macroscopic and microscopic examination of fecal specimens. In Diagnostic Medical Parasitology, 3rd ed.; Giboda, M.N., Vokurkova, P., Kopacek, O., Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1977; pp. 608–649. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, I.J.; Wright, K.A. Cell injury caused by Trichinella spiralis in the mucosal epithelium of B10A mice. J. Parasitol. 1985, 71, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attia, R.A.; Mahmoud, A.E.; Farrag, H.M.; Makboul, R.; Mohamed, M.E.; Ibraheim, Z. Effect of myrrh and thyme on Trichinella spiralis enteral and parenteral phases with inducible nitric oxide expression in mice. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2015, 110, 1035–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bayati, M.A.; Ahmad, M.A.; Khamas, W. The potential effect of L-arginine on mice placenta. Adv. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2014, 3, 1000150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.F.; Zakaria, S.; Fahmy, A. Can Chronic Nitric Oxide Inhibition Improve Liver and Renal Dysfunction in Bile Duct Ligated Rats? Adv. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 2015, 298792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Aziz, M.; Elsayed, H. Insights into the effects of inducible and neuronal nitric oxide synthase isoenzymes in experimental intestinal heterophyiasis. Parasitol. United J. 2021, 14, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, R.M.; El-Arousy, M.H.; Abd EI-Aal, A.A. Albendazole: A study of its effect on experimental Trichinella spiralis infection in rats. Egypt J. Med. Sci. 1998, 19, 281–290. [Google Scholar]

- Demoulin, J.C.; Kulbertus, H.E. Histopathological examination of concept of left hemiblock. Br. Heart J. 1972, 34, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, A.E.; Zoghroban, H.S.; Ghanem, H.B.; El-Guindy, D.M.; Younis, S.S. The effects of L-citrulline adjunctive treatment of Toxoplasma gondii RH strain infection in a mouse model. Acta Trop. 2023, 239, 106830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czarnewski, P.; Araújo, E.C.B.; Oliveira, M.C.; Mineo, T.W.P.; Silva, N.M. Recombinant TgHSP70 Immunization Protects against Toxoplasma gondii Brain Cyst Formation by Enhancing Inducible Nitric Oxide Expression. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, X.P.; Pretlow, T.G.; Rao, J.S.; Pretlow, T.P. Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) is expressed similarly in multiple aberrant crypt foci and colorectal tumors from the same patients. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 419–422. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Y.H. Biostatistics 102: Quantitative data—Parametric & non-parametric tests. Singapore Med. J. 2003, 44, 391–396. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Post-hoc multiple comparisons. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2015, 40, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosking, B.C.; Watson, T.G.; Leathwick, D.M. Multigeneric resistance to oxfendazole by nematodes in cattle. Vet. Rec. 1996, 138, 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Bella, C.; Benagiano, M.; De Gennaro, M.; Gomez-Morales, M.A.; Ludovisi, A.; D’Elios, S.; Bruschi, F.A. T-cell clones in human trichinellosis: Evidence for a mixed Th1/Th2 response. Parasite Immunol. 2017, 39, e12412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashour, D.S.; Abou Rayia, D.M.; Saad, A.E.; El-Bakary, R.H. Nitazoxanide anthelmintic activity against the enteral and parenteral phases of trichinellosis in experimentally infected rats. Exp. Parasitol. 2016, 170, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdeltawab, M.; Abdel-Shafi, I.; Aboulhoda, B.; Wanas, H.; Saad El-Din, S.; Amer, S.; Hamed, A. Investigating the effect of the nitric oxide donor L-arginine on albendazole efficacy in Trichinella spiralis-induced myositis and myocarditis in mice. Parasitol. United J. 2022, 15, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguayo-Ortiz, R.; Méndez-Lucio, O.; Medina-Franco, J.L.; Castillo, R.; Yépez-Mulia, L.; Hernández-Luis, F.; Hernández-Campos, A. Towards the identification of the binding site of benzimidazoles to β-tubulin of Trichinella spiralis: Insights from computational and experimental data. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2013, 41, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despommier, D.D. Trichinella spiralis and the concept of niche. J. Parasitol. 1993, 79, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.L.; Wang, Y.Y.; Fang, Q.; Xue, Y.Q.; Shen, J.L. In vitro killing of adult Trichinella spiralis by exogenous nitric oxide. Chin. J. Parasitol. Parasit. Dis. 2012, 30, 374–377. [Google Scholar]

- Li, E.; Zhou, P.; Singer, S.M. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase is necessary for elimination of Giardia lamblia infections in mice. J. Immunol. 2006, 176, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, Y.S.; Gillin, F.D.; Eckmann, L. Adaptive immunity-dependent intestinal hypermotility contributes to host defense against Giardia spp. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 2473–2476. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Peirasmaki, D.; Svärd, S.; Åbrink, M. Serglycin-deficiency causes reduced weight gain and changed intestinal cytokine responses in mice infected with Giardia intestinalis. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 677722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, S.; Du, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhan, B.; Hao, J.; Jia, Z.; Huang, J.; Guo, Y.; et al. PD-1 deficiency impairs eosinophil recruitment to tissue during Trichinella spiralis infection. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasuriya, G.K.; Nugapitiya, S.S.; Hill-Yardin, E.L.; Bornstein, J.C. Nitric Oxide Regulates Estrus Cycle Dependent Colonic Motility in Mice. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 647555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricken, F.J.; Nell, J.; Grüner, B.; Schmidberger, J.; Kaltenbach, T.; Kratzer, W.; Hillenbrand, A.; Henne-Bruns, D.; Deplazes, P.; Moller, P.; et al. Albendazole increases the inflammatory response and the amount of Em2-positive small particles of Echinococcus multilocularis (spems) in human hepatic alveolar echinococcosis lesions. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbajosa, S.; Rodríguez-Angulo, H.O.; Gea, S.; Chillón-Marinas, C.; Poveda, C.; Maza, M.C.; Colombet, D.; Fresno, M.; Gironès, N. L-arginine supplementation reduces mortality and improves disease outcome in mice infected with Trypanosoma cruzi. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kołodziej-Sobocińska, M.; Dziemian, E.; Machnicka-Rowińska, B. Inhibition of nitric oxide production by aminoguanidine influences the number of Trichinella spiralis parasites in infected “low responders” (C57BL/6) and “high responders” (BALB/c) mice. Parasitol. Res. 2006, 99, 194–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frydas, S.; Papaioannou, N.; Hatzistilianou, M.; Merlitti, D.; Di Gioacchino, M.; Castellani, M.L.; Conti, P. Generation of TNFα, IFNγ, IL-4, IL-6 and IL-10 in Trichinella spiralis infected mice: Effect of the anti-inflammatory compound mimosine. Inflammopharmacology 2001, 9, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).