Abstract

Introduction: Mental health conditions include disorders, diseases, problems, and/or symptoms that affect an individual’s emotions, thoughts, and/or behaviors, such as anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders. When describing the etiology of mental health conditions, various factors are often considered, including genetic, biomedical, social, and environmental. Therefore, the theoretical framework through which mental health conditions are discussed is important to consider, as it directly affects the conceptualization and treatment of mental health conditions. This narrative review synthesized the existing literature on different theoretical frameworks that can be used to understand the etiology of mental health conditions. Methods: This review employed a pragmatic, narrative approach to literature synthesis. Google Scholar was searched using variations of the terms “theory”, “mental health”, “etiology”, and “resilience” to locate the relevant peer-reviewed literature. The identified literature was further mined for additional important evidence sources. Results: Six theoretical frameworks were identified and discussed, including (1) attachment theory, (2) intersectionality theory, (3) intergenerational theory, (4) queer theory, (5) social cognitive theory, and (6) resilience theory. Strengths and weaknesses of each theoretical framework are identified. Conclusions: Although overlap exists among these theories, the different theoretical frameworks influence the conceptualization and treatment of mental health conditions. This has important implications since perceptions about the etiology and treatment of mental health conditions can be influenced by the theoretical perspective that one adopts. Some theoretical frameworks focus predominantly on psychosocial versus biological mechanisms, or vice versa, alluding to the need for interdisciplinary collaboration to best understand the etiology and treatment of mental health conditions.

1. Introduction

Mental health conditions (e.g., anxiety, depression, personality disorders, substance use disorders) are considered disorders, diseases, problems, and/or symptoms that impact one’s emotions, thinking, and/or behavior and at times lead to distress and impaired functioning [1]. The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation estimated that in 2019, the prevalence of anxiety and major depressive disorders increased by 15% and 18%, respectively, with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, and that in 2021, approximately 13.9% of the global population experienced some type of mental health condition [2]. These estimates varied by region, with the United States, Brazil, and Australia having the highest rates per 100,000 persons [2]. Globally, mental health conditions such as anxiety, depression, and schizophrenia were estimated to cost the global economy USD 2.5 trillion in 2010, with an extrapolated estimate of USD 6 trillion by 2030 [3], mostly attributable to loss in productivity and healthcare costs [4,5]. The adverse impacts of mental health conditions on quality of life [6], socioeconomic attainment [7], physical health [8], and global productivity [5] make its prevention a global health priority.

Childhood contexts, including the occurrence of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs; described as adverse events experienced before 18 years of age, such as abuse and/or neglect), have been strongly associated with mental health conditions during childhood and adulthood [9], revealing an important factor to consider in the discourse of mental health conditions. However, other factors, such as genetic predeterminants [10], prenatal conditions [11], social support [10], and the environment (e.g., pollutants) [12], among others [13], can also significantly shape one’s mental health outcomes. Nevertheless, uncertainty remains as to why certain individuals or groups experience greater prevalence of mental health conditions compared to others despite exposure to similar risk factors. In pursuit of better understanding the impacts of these factors on mental health conditions, researchers have applied different frameworks, including attachment [14], intergenerational [15], intersectionality [16], queer [17], social cognitive [18], and resilience [19] theories. Some of these theories (i.e., attachment, intergenerational, and social cognitive theory) have been used historically to better understand mental health conditions, while others have been applied in researching conditions of mental health only more recently (i.e., intersectionality, queer, and resilience theory). Despite some overlap, these theories originated from different fields of expertise, providing unique ways of conceptualizing the etiology of mental health conditions. Exploring historical and contemporary understandings of attachment, intergenerational, intersectionality, queer, social cognitive, and resilience theories can inform our understanding of the etiology of mental health conditions and offer various frameworks that could be applied to different mental health conditions in different populations, helping to more optimally understand and address the global burden of mental health conditions.

Purpose of the Review

This review employed a narrative synthesis approach to explore attachment, intergenerational, intersectionality, queer, social cognitive, and resilience theories as frameworks for understanding the etiology of mental health conditions [20,21]. A narrative synthesis approach allows for a structured and rapid approach to literature synthesis; such an approach is not bound by certain inclusion or exclusion criteria, which limits systematic searching and reproducibility, but allows for greater exploration and inclusion of relevant evidence sources [20,21]. Narrative synthesis reviews do not seek to identify all relevant studies but instead to provide a summary of main understandings and implications on a certain topic [20,21].

2. Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Included studies (1) were any peer-reviewed studies that either used or described the identified theories either broadly or in practice in the context of mental health conditions; (2) if applied in a human sample, could target any demographic group and/or be conducted in any geographical region; (3) were written in a language spoken by the team members (i.e., English, French, Spanish, or Gujarati); and (4) could be conducted at any timepoint. Studies were excluded if they were not peer-reviewed (e.g., grey literature) and were written in a language not spoken by the team. Conference abstracts, opinion letters, and commentaries were also excluded.

2.2. Search Strategy

Important frameworks or theories that can help to explain the etiology of mental health conditions were identified via discussion with academic experts and an exploration of the literature. One author (SK) used Google Scholar to search for relevant articles from November 2024 to January 2025, updated again in March 2025. SK used the Advanced Search function to create separate searches with the terms “attachment”, “intergenerational”, “intersectionality”, “queer”, “social cognitive”, and “resilience” alongside variations of the terms “theory”, “mental health”, “etiology”, and “resilience”. SK also mined identified articles to pinpoint additional important and the relevant literature. The relevant literature fell into two categories and were screened accordingly: (1) those discussing the theory more broadly and (2) those providing empirical support of the theory in practice. Studies discussing each theory (i.e., attachment, intergenerational, intersectionality, queer, social cognitive, resilience) more broadly were used to provide a general description of the theory and its evolution over time; therefore, once its description was outlined (i.e., data saturation attained), no additional studies were examined. Similarly, studies focused on applying the theory in practice (e.g., empirical studies) were included in this study to outline relevant evidence and describe the theory’s potential in guiding mental health condition treatment through example; however, reviews (e.g., systematic reviews) were used, when available, as the highest form of evidence to characterize empirical findings [22]. After describing various empirical examples, no additional studies were included.

3. Attachment Theory

Attachment theory posits that infants and children have a primitive need for nurturance, comfort, and safety from a parent, where those who attain secure attachment have an increased likelihood of survival and longevity [23]. While the term parent is used, for the purpose of this review, the term parent refers to any figure primarily responsible for taking care of a child. Early theorists such as Freud first referred to the infant’s relationship with their parent as “dependency”, founded on the need to acquire food and pleasure [23]. As attachment theory emerged, Bowlby [23] claimed that the use of the term dependency was detrimental to studying infant-mother relationships. If the acquisition of food and pleasure was in fact a dependency-driven behavior, Bowlby argued that infants would feed from and find pleasure with any individual [23]. However, young infants have a clear tendency to seek food and pleasure from their mother relative to others, alluding to the presence of an emotional attachment [23]. Bowlby believed that even if infants are largely dependent on their primary parents, especially in the initial period of life, the attachment between a mother and infant extends beyond the acquisition of resources to one that is emotionally reciprocal [23]. Other studies conducted among primates were in alignment with this line of thinking. For example, Harlow and colleagues removed newborn rhesus monkeys from their mothers and placed them in an experimental environment with two constructed mothers, alternating which fake mother was holding food: (1) a wire mother and (2) a mother covered in cloth [24]. This team observed that newborns would expend nearly all their time with the cloth-covered mother regardless of whether the cloth mother held the food or not, only approaching the wired mother temporarily to feed when it was conditioned to hold the food, suggesting the importance of an emotional and comforting attachment [24]. With evidence pointing toward an emotionally driven attachment, researchers studied the characterization of attachment.

Ainsworth and Bell [25] were important researchers who elaborated on attachment theory by defining three different patterns categorized under either secure or insecure types. A secure attachment pattern is characterized by the ability of a child to attain comfort and safety from their primary parents and other important relationships [25]. Securely attached children have a supportive base and safe haven which provide them with comfort in times of distress [23,26]. In turn, this may promote positive mental health outcomes, as securely attached individuals are more likely to successfully navigate stress and return to homeostasis more rapidly [23]. Secure attachment has also been linked to children’s increased comfort in exploring new or risky circumstances, increasing one’s threshold vis-à-vis novel stressors [23]. In contrast, insecure attachment is linked to suboptimal health and was initially subdivided into two types: (1) avoidant, where children develop avoidant behaviors toward their parent(s) due to inconsistent responses; or (2) anxious, where children become anxiously attached to their parent(s) as the child obtains safety and comfort from them, but unreliably [25]. Later, a third type of insecure attachment, termed disorganized attachment and considered the most debilitating form of insecure attachment, was identified, reflecting a mixture of both extreme avoidant and anxious attachment patterns [26]. Children who exhibit insecure patterns of attachment demonstrate compromised exploratory behaviors and socio-emotional functioning (e.g., withdrawal, impulsivity) [23,27]. Children exhibiting insecure patterns of attachment also show elevated levels of cortisol [28,29], which could help to explain the observed associations between children’s insecure attachment pattern and mental health conditions such as depression [30] and anxiety [31]. Therefore, attachment is an important factor to examine in the etiological origin of mental health conditions.

Attachment theory also extends into the context of adult intimate relationships, whereby similar patterns of childhood attachment are observed in adulthood [32]. Secure attachment in adults is characterized by feeling lovable and perceiving others as caring and supportive, leading to strong and reliable relationships [32]. Preoccupied attachment, one form of insecure attachment, is characterized by an overdependence on psychological intimacy in intimate relationships. Adults with preoccupied attachment patterns tend to experience considerable distress and anxiety in their relationships, requiring consistent psychological reassurance which can push their partners away [14]. The other form of insecure attachment, dismissive attachment, involves distancing oneself from intimate partners when relationships become overly psychologically intimate due to their fear and discomfort with such intimacy [14]. While preoccupied and dismissive attachment patterns share some characteristics with anxious and avoidant attachment patterns, they should not be used interchangeably.

Both preoccupied and dismissive attachment patterns are associated with various mental health conditions in adulthood, such as anxiety [33] and depression, among others [14], attributable to difficulty in maintaining close, intimate relationships [14]. Without sufficient attachment security, individuals may also engage in more health-damaging behaviors (e.g., binge eating, avoidant behaviors) to alleviate their mental distress, which paradoxically increases their risk of developing mental health conditions [14]. On the other hand, studies consistently show elevated levels of the stress-induced hormone cortisol among insecurely attached adults, especially those with preoccupied adult attachment [34], representing an underlying biosocial pathway through which attachment insecurity can affect mental health conditions. However, others suggest that attachment patterns predict psychological (e.g., anxiety) but not cortisol responses to stress [35]. These differences could be attributed to the measuring of attachment, as there is debate on whether attachment should be measured continuously (secure versus insecure) or categorically (i.e., dismissive, preoccupied, disorganized, secure) [36,37]. While adult attachment patterns are largely established in and predicted by patterns observed during childhood and adolescence [23,25], much of the variance in attachment pattern outcomes remain unexplained [38,39,40]. This unexplained variance is concerning, as the pattern of attachment that one develops in early childhood can have far-reaching positive or negative impacts on mental health outcomes across the lifespan [14].

As attachment theory focuses extensively on the relationship between a parent and child in the early years, ACEs, which reflect stressors such as depression, can undermine secure attachment development and lead to mental health conditions [27,41,42]. However, individuals with no ACEs can also demonstrate differing patterns of attachment and mental health outcomes, in part due to the style and quality of parenting received [43,44]. For example, parents can adopt authoritarian, authoritative, permissive, and uninvolved parenting styles, each uniquely associated with potential child outcomes (Table 1) [44]. Overall, suboptimal parenting places children at risk of lifetime mental health conditions by exacerbating relevant precursors (e.g., emotional regulation), independent of ACEs [44]. In contrast, optimal parenting, characterized by nurturance, responsiveness, positive encouragement, and support [45], is linked to more secure attachment and a lower likelihood of mental health conditions later in life [46]. It is important to note that while most studies focus on the degree/quality of negative parenting as opposed to positive parenting, the absence of negative parenting does not necessarily imply positive parenting [47]. For these reasons, the quality of positive parenting should be considered above and beyond ACEs given its independent association with children’s development to best understand the etiology of mental health conditions [44,48].

Table 1.

Parenting styles and expected outcomes among children.

Other explanations for the origin of attachment patterns have been largely attributed to psychosocial factors (e.g., parental mental health conditions) and less so to biological factors [49]. For example, cortisol has been directly associated with disorganized versus non-disorganized attachment patterns in children [49]. Increased focus of research on physiological factors, in addition to social ones, can help to promote the understanding of the development of attachment and inform potentially more effective interventions to promote attachment security [50]. In the context of mental health treatment, this is important since individuals experiencing severe mental health conditions have described the need for their attachment to be addressed throughout mental health service delivery [51]. Moreover, interventions that target child and adult attachment insecurity, or components of it, consistently result in better mental health outcomes for individuals involved [50,52,53]. Taken together, the findings underpin the potential importance of considering attachment theory when explaining the etiology of mental health conditions.

4. Intergenerational Theory

Intergenerational theory implies that health outcomes, along with their risk and protective factors, are transferred across generations [15]. According to intergenerational theory, some families are predisposed to developing certain mental health conditions such as depression [15,54]. Through a psychosocial lens, the intergenerational continuity of parenting phenomenon suggests that individuals will often employ similar parenting patterns as those of their parents; individuals who experienced ACEs are more likely to behave in manners, or reside in environments, that cause their own children to experience ACEs, perpetuating both the occurrence of ACEs intergenerationally and the risk of developing mental health conditions [55,56]. Conversely, a child who receives nurturance and safety from their parents is more likely to provide more optimal parenting to their own child(ren), reducing the likelihood of mental health conditions developing across generations [55]. Many studies demonstrate an association between parental ACEs and mental health conditions among their children, which can be elucidated through the application of intergenerational theory [42,57,58]. Others support the intergenerational transmission of risk factors of mental health conditions such as lower socioeconomic status [54] or genetic polymorphisms [47]. Intergenerational theory posits that the examination of one’s family dynamics and mental health condition history provides a relatively strong prediction of what their own mental health trajectory will look like [15].

Bowen [15] was an important contributor to intergenerational theory. He discussed the behaviors and outcomes of one generation as a function of those preceding it, whereby certain traits become more pronounced over generations while others dissipate [15]. He argued that intergenerational transmission is facilitated either through learning or through automatic and unconsciously learned emotional programming [15]. Bowen applied intergenerational theory in his practice to identify the influence of previous generations on current negative behaviors (e.g., health-damaging substance use) in an attempt to break the cycle and shift outcomes to more positive ones [15]. Concepts underlying this theory also helped illuminate the impact of other factors above and beyond ACEs, such as lower educational attainment, on adverse intergenerational health outcomes [15]. However, the focus of intergenerational theory on social aspects of transmission alone [15] ignores the influence of genetics and physiological mechanisms on one’s development and their mental health conditions [47], both of which are known to be important contributors to human health [47,59].

From a biological perspective, genetics is also an important aspect of intergenerational theory, as certain alleles can predispose families to experiencing more mental health conditions [47]. Many mental health conditions are known to have a degree of genetic inheritance, where certain alleles can serve to increase one’s risk of developing certain mental health conditions [47,59]. For example, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and psychosis are known to be mental health conditions that occur across familial generations due to genetic transmission [59]. Likewise, research points to family histories of depression and anxiety in predicting subsequent diagnoses in future generations [59]. However, the intergenerational implications of genetic transmission on mental health conditions are not always observed [47]. This could be attributable to differential susceptibility, which suggests that a genotype may prove disadvantageous and even harmful when exposed to negative environmental conditions (e.g., ACEs), while the same genotype may reap the most benefits when exposed to positive environmental conditions such as nurturing parenting [47]. Indeed, studies examining the interaction between genes and the environment show that in positive conditions, individuals with certain genotypes experience better mental health outcomes, while in adverse conditions, they are more likely to experience mental health conditions [60,61,62]. Therefore, it can be inferred that as parents learn to foster more positive childhood environments (e.g., reverse the intergenerational continuity of negative parenting) or relocate to better environments [55], children’s genotypes may be expressed more advantageously to reduce the risk of mental health conditions from developing [47,63]. The differential susceptibility phenomenon can also help explain why familial mental health outcomes can diverge over time [47]. However, other intergenerational biological mechanisms such as epigenetic processes, inflammation, and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis function, among others [64], could also help explain the intergenerational transmission of mental health conditions.

At a broader level, intergenerational theory can also inform understanding of the experiences of groups’ or populations’ mental health conditions that may be attributable to systemic-level problems and trauma [65]. For example, colonized Indigenous peoples, such as many groups residing in upper North America, have and continue to experience grave inequities through colonization, genocide, and assimilation, which, in turn, increase their vulnerability to poverty, substance use, and adverse mental health conditions [65,66]. The traumatic impacts of these historical and ongoing events are so pervasive that they become embedded within the population [67]. Consequently, the negative coping skills, socioeconomic repercussions, and negative lived experiences are intergenerationally transmitted, increasing one’s risk of developing mental health conditions [65,66]. Other groups, such as those surviving the Holocaust, show persistent impacts of the trauma across multiple generations, demonstrating persisting systemic-level problems among affected populations that influence mental health conditions intergenerationally [65]. Psychopathological impacts from human conflicts, such as the Dutch famine (a 5-month period of extreme food deprivation), can also be studied through intergenerational theory [68]. Therefore, knowledge of the historical roots of the family or group under study can allow for the effective application of intergenerational theory to better understand the development of mental health conditions.

Studies elucidate how intergenerational theory can be applied in practice to ameliorate mental health outcomes. It has been well-established that interventions (e.g., psychoeducational, coping skills) that enhance parenting result in better mental health outcomes for children [69], even if parental mental health is not ameliorated [70]. In families with histories of mental health conditions, early family interventions that engage all family members can also help to reduce negative outcomes among children and across the lifespan [71]. Considering that genes can interact with surrounding environments for the better, more optimal childhood conditions are expected to further enhance mental health in children with certain genotypes [60,61,62]. Having knowledge of which genotypes are most likely to predict mental health conditions later in life can help healthcare professionals intervene accordingly [72], promoting individuals’ number and types of protective factors to prevent the emergence of mental health conditions. In alignment with this, pharmacotherapies that target substance use disorders and mental health conditions also show differing effectiveness based on genetic expression, informing the applicability of pharmacotherapies among different individuals [73]. At a systems level, policies and legislation that reduce oppression have resulted in better mental health outcomes for marginalized groups [74]. For example, following the legalization of same-sex marriage, sexual and gender minorities reported better mental health outcomes in the Netherlands and a smaller gap in mental health burden compared to their cisheterosexual counterparts [75]. Using intergenerational theory to identify historical roots for mental health conditions can help to guide intervention delivery, breaking the intergenerational transmission of mental health conditions.

5. Intersectionality Theory

Applicable across diverse exposures and outcomes, intersectionality theory helps elucidate social forces such as racism, queerphobia, ableism, and fatphobia, among others, which can undermine an individual’s capacity to attain equitable opportunities within healthcare, employment, and educational sectors [16,76], all important indicators of life satisfaction and mental health well-being [12]. Crenshaw [77] first coined the term “intersectionality” over 30 years ago, although it was not until the last decade that this theory became more popular [16,76]. Intersectionality theory sprouted from the Black feminist movement, where Crenshaw observed that racism toward Black individuals or discrimination toward women were discussed separately in legislative contexts [77]. From her perspective, without examining discriminatory oppressions towards both being Black and a woman as an intersection, it was impossible to fully comprehend and conceptualize the challenges that Black women experience in society [77]. Therefore, she argued that discussing racism experienced as a Black person and discrimination experienced as a woman separately (reflecting a single-axis framework) overlooks the additive and intersecting oppressions that arise from being both Black and a woman at the same time (reflecting a multi-axis framework) [77]. In most of Canada, the United States, Australia, and Europe, intersectionality theory currently implies that individuals who diverge from the white, cisheterosexual, able-bodied, male identity will experience more vulnerabilities throughout their lifetime, exacerbating their risk of developing mental health conditions [16]. Applying intersectionality in practice can help explain one’s positioning within different contexts and the consequent impact on their mental health conditions [16].

Researchers interested in intersectionality theory have extended its application to consider the influence of sexual orientation, class, and other sociocultural factors on one’s experience in life [16]. Significant evidence indicates that people who are marginalized, such as people of color [12], sexual and/or gender minority groups [78], and people living with a disability [10], among others, often experience more ACEs, which can be attributable to familial experiences with systems of oppression [10,79]. People who are marginalized almost always report disproportionately more negative outcomes across social services (i.e., mental health centers, drug treatment programs, shelters [80,81]) as well as criminal justice systems (i.e., police, legal services [82,83]). For example, two studies conducted by Kattari and colleagues [80,81] demonstrate the compounding discriminations that trans and gender non-conforming individuals experience when concomitantly identifying as a person of color or disabled individual. These outcomes are linked to biases, stigma, stereotypes, discrimination, and oppressions that result in suboptimal provision of care and reluctance in seeking future support [12,82]. Consequently, suboptimal and discriminatory service provision undermines healthy familial functioning, successful performance in educational and employment settings, and typical childhood development [10]. People who are marginalized are less likely to ascertain educational or employment opportunities [12], and (1) if employed, these people report on average lower incomes than cisheterosexual white men [12], and (2) if enrolled in school, marginalized people must navigate colonialist and white-centric beliefs engrained within educational curriculums [16]. Incarceration rates are almost always higher among people of color compared to their white counterparts despite comprising a smaller proportion of the population, reflecting systems founded on enslavement and racial control [16]. It is not surprising that people who are marginalized experience more vulnerabilities to developing mental health conditions as they must navigate multiple systems of oppression [12].

Intersectionality theory is a powerful framework that can illuminate inequities that underlie various mental health conditions [76,77]. Many studies elucidate a positive association between perceived discrimination and the occurrence of mental health conditions [84]; therefore, it can be inferred that services and resources that decrease perceived discrimination can also decrease mental health burden among marginalized groups. For example, integration of gender-affirming care relevant to gender and sexual diversity has been associated with decreased prevalence of certain mental health conditions among sexual and gender minorities [85]. Cultural competency interventions have also led to increased patient satisfaction with providers among racialized individuals [86], likely resulting in better mental health outcomes [87]. Disability-affirming care that consists of caring, supportive responses underpinned by equity, diversity, inclusion, and accessibility concepts also results in better mental health outcomes among disabled individuals [88,89,90]. While complex, in practice, intersectionality theory can be simplified through the intersectional examination of risk and protective factors specific to individuals with various identities, revealing tangible factors that can be acted upon to foster better mental health outcomes among marginalized groups [76,77].

Effective application of intersectionality theory shifts the narrative from blaming the individual to considering the broader social dimensions, which inhibit ascertainment of equitable opportunities that are known to reduce the likelihood of mental health conditions from developing [76,77]; through intersectionality theory, mental health conditions become the embodiment of the intersecting oppressions one experiences rather than the embodiment of the individual’s behaviors. However, changes in policy and legislation can only foster change if the social narrative is also shifted to weaken the control of those who traditionally hold more power (i.e., cisheterosexual, white males) [16].

6. Queer Theory

Queer theory challenges the predominance of cisheterosexual binary divisions of gender (woman versus man) and sexuality (heterosexuality versus homosexuality), elucidating the impacts of these binary norms within different sectors on sexual and gender minority health, such as reproductivity or even citizenship [17,91]. Sexual and gender diversity is evident throughout human history; however, it may be epitomized in the 20th century, where homosexuality was characterized as a “psychopathological and as a sociopathic personality disturbance” in the first edition of the Diagnostic Statistic Manual (DSM) of Mental Health Disorders ([91], p. 9). In the second edition of the DSM, homosexuality was removed as a sociopathic disturbance but still defined as predictive of psychopathology, being paralleled with other sexual acts such as pedophilia and fetishism [91]. Other terms such as ego-dystonic homosexuality and gender identity disorder were included in subsequent DSM versions in an attempt to explain the etiology of homosexuality [91]. The most current version no longer has homosexuality included as a mental health condition but includes gender dysphoria, which conflates sex and gender and encourages gender-based norms [91]. The biomedicalization of queerness continues to challenge sexual and gender minority individuals’ navigation in different social contexts, which, in turn, negatively impacts their mental health outcomes [91].

Queer theory can be applied to illuminate the ongoing impacts of historic events that continue to isolate people who are sexually and gender diverse in the 21st century through the pathologization of their identity and behaviors [91]. For example, men who were gay were described as carriers of the HIV virus, stigmatized as pathogenic, and blamed when testing seropositive for HIV; essentially, men who were gay were considered dispensable [91]. On a similar note, some European doctors considered queerness to be a flaw in the human design, as it inhibited reproductivity. In fact, German doctors referred to homosexuality as “a threat to public health” ([91], p. 13). Such radical beliefs were and continue to be entrenched within political, health, economic, and social spheres, further isolating people who identify as a sexual and gender minority within society [91]. The different forms of discrimination that sexual and gender minority individuals can experience, such as macroaggressions (e.g., homophobia), microaggressions (e.g., misuse of pronouns), or unauthentic identity expression (e.g., remaining closeted), ultimately increase one’s risk of developing mental health conditions [78]. It is unsurprising that sexual and gender minority individuals report higher rates of mental health conditions when they are described as inhumane, disposable, pathogenic, and health threats [91].

The biomedicalization and pathologization of sexuality and gender also affect the mental health conditions of all family members [91]. For example, in an attempt to identify the etiology of homosexuality, many theorists and researchers who were homophobic believed that men who were gay developed effeminate characteristics due to a mother being overly protective, anxious, and seductive, while fathers were blamed if they diverged from the “breadwinner” role [91]. Consequently, parents were described as causal, etiological factors for homosexuality and blamed for their children’s sexual and gender diversity ([91], p. 11). This parental self-blame, rejection, stigmatization, and confusion can lead to mental health conditions and neglectful and abusive behaviors in parents [91], resulting in sexual and gender minority individuals often reporting more ACEs [92]. In turn, ACEs and the associated negative impacts can undermine sexual and gender minority individuals’ mental health outcomes and overall quality of life [92,93], which is further compounded by the additional discrimination and oppressions that these individuals experience outside of the home [82,94]. In many instances, not only do sexual and gender minority individuals have to be wary when navigating the broader community [82,94], they must often do so within the home as well [92].

Many sexual and gender minority individuals state that some or all of their mental health conditions stem from their sexual orientation and/or gender identity living within a cisheterosexual society, extending above and beyond ACEs [17]. For example, sexual and gender minority individuals who test seropositive for HIV are more susceptible to experiencing stigmatized responses in healthcare as they fit the historical discourse of pathogenesis [91], rather than considering the systemic oppressions and barriers that cause higher rates of HIV among sexual and gender minority individuals [17]. Further, a diagnosis of gender dysphoria is currently required to be eligible for any hormonal or gender-related medical treatments in many North American regions [91]. In fact, some researchers justify the need to funnel resources into identifying the etiology of homosexuality [17]. These examples demonstrate that to this day, identifying as a sexual and gender minority is still considered a biomedical condition.

While queer-specific resources are important for sexual and gender minority individuals, a division of facilities and services based on sexuality and gender paradoxically amplifies cisheterosexual binary norms by further isolating sexual and gender minority individuals and centralizing the responsibility of queer inclusivity and responsibility into a select few settings [91]. The alarmingly higher rates of mental health conditions among sexual and gender minority individuals are ultimately embodiments of cisheterosexual norms and historical understandings, which prevent dissolution of a cisheterosexual binary way of living [78,91]. Provision of support that is underpinned by sexual and gender diversity inclusivity can, however, reduce the mental health burden among sexual and gender minorities [85]. Indeed, gender-affirming care that considers sexual and gender health and diversity results in decreased occurrence of mental health conditions among sexual and gender minorities [85]. At a broader level, legislation and policy that consider sexual and gender minorities as equal constituents within society and result in equal rights (e.g., legal marriage, gender-neutral bathrooms) also link to better mental health outcomes [75,95]. Applying queer theory in research can help identify the historical beliefs that are perpetuating biases, stigmas, stereotypes, and oppressions, address them in practice, and promote sexual and gender minority individuals’ mental health outcomes.

7. Social Cognitive Theory

Based on the assumption that individuals learn by witnessing behaviors from others within various social environments, social cognitive theory posits that one’s behaviors are the embodiment of learned social processes, with less of an emphasis on biological processes [96]. Social cognitive theory is founded on two key constructs: (1) self-efficacy, which describes the control that an individual believes they have in a given context and (2) outcome expectancies, the outcomes that one expects based on their behavior in a given context [96]. However, these two constructs also interact with one’s environmental conditions in a reciprocal manner, such that environmental conditions and one’s behaviors impact one another [96]. Social cognitive theory has been influenced by the study of human behavior, specifically: (1) imitation, (2) latent learning, and (3) social learning [97]. Humans are believed to have a primitive drive to imitate others, which is more likely to reoccur if previous acts of imitation were reinforced by external stimuli [97]. Latent learning refers to learning that does not require any reinforcement [97]. More specifically, latent learning leads to a distinction between performance and learning, wherein latent learning can occur without reinforcement but that reinforcement can encourage more optimal performance [97]. Social learning, which encapsulates more strongly the constructs of outcome expectancies, refers to the reinforced and innate outcomes that one expects when behaving in a specific manner [97]. It is important to make a distinction between the three when applying social cognitive theory.

When the first construct of social cognitive theory, self-efficacy, is considered, a direct connection is made between ones’ perceptions of their capacity to overcome challenging situations and their actual attempts to tackle these challenging situations [96]. An individual’s ability to be successful in various settings is strongly correlated with mental health outcomes [98,99,100]. If one believes they are incapable of surmounting a challenge, they may instead cope through avoidant-based behaviors, including dissociation [101], withdrawal, and substance use [100], all of which are known to increase one’s risk of developing mental health conditions. The second construct, outcome expectancies, refers to the various outcomes that an individual may foresee happening if they were to tackle a challenge [96]. These outcome expectancies can be further subdivided into areas of consequence (i.e., physical, social, self-evaluative), direction of outcome, and length of duration of the outcome [96]. Therefore, when one is deciding whether to tackle a challenge, they are anticipated to consider physical, social, and self-evaluative outcomes of a behavioral change, whether these consequences will be positive or negative, and the length of time required before, and how long, the consequence; if the positives of overcoming a challenge outweigh the negatives, there may be a greater motivation to pursue and maintain a change in behavior [96].

Social cognitive theory posits that individuals who develop negative beliefs regarding their self-efficacy in certain environments such as educational settings are more likely to establish lower expectations for themselves, leading to lower likelihood of success [96,97]. Moreover, those who have pessimistic beliefs regarding the area of consequence, direction of consequence, and duration of consequence are also less motivated to try and incur change [96]. For example, a study conducted by Keller et al. revealed the impact that one’s perception of stress has on one’s longevity even if experiencing similar levels of stress [102]. Relative to individuals who experienced almost no stress in the past year and who perceived that stress has hardly any or no impact on their health, those who reported experiencing a lot of stress in the past year and also perceived stress as being very impactful had a 43% higher likelihood of premature death whereas those who concomitantly reported experiencing a lot of stress in the past year but perceived stress to have hardly any impact on their health compared had a 17% lower likelihood of premature death [102]. Further, studies provide converging evidence of social cognitive theory underlying and explaining behavioral differences related to not only health behaviors [103,104], but also socioeconomic outcomes [105,106]. Findings from studies also demonstrate that social cognitive theory can be used to inform and guide primary care interventions [107,108]. This suggests that social cognitive theory can serve as a framework for conceptualizing mental health conditions while also being applied in practice to optimize service delivery.

Substance use disorders are often comorbid with a number of other mental health conditions, including anxiety and mood disorders [109], personality disorders [110], and suicidal behavior [111]. Social cognitive theory was applied by Heydari et al. to develop an educational-based intervention to support those with opium use disorders, whereby the program consisted of: (1) promoting knowledge about opium use disorders and treatment, (2) promoting vulnerability among individuals with opium use disorders, (3) self-efficacy through learning and a review of problem-solving and decision-making skills, and (4) introducing clients’ social supports to the program and encouraging self-governance [103]. The findings from this study revealed a statistically significant difference in terms of successful quitting rates, recurrence rates, and self-efficacy for those in the intervention group relative to the control group, demonstrating the use of social cognitive theory in guiding substance use disorder treatments [103]. Further, social cognitive theory has been used to conceptualize mental health conditions among students. For example, in a study of Iranian high school and pre-university students, higher levels of total, physical, and academic self-efficacy negatively predicted depressive symptoms while higher levels of total, physical, and emotional self-efficacy negatively predicted anxiety symptoms [105]. Similarly, in another study, Chinese students’ perceived self-efficacy was associated with test anxiety scores such that greater perceived self-efficacy was associated with lower anxiety scores [112]. Overall, research suggests that the constructs of self-efficacy and outcome expectancies, two foundational constructs associated with social cognitive theory, can be tightly linked to the etiology of mental health conditions, particularly when individuals perceive limited capacity to overcome challenging conditions and/or perceive limited benefit in terms of overcoming a challenge [113].

8. Resilience Theory

Resilience theory is a framework that can be applied to conceptualize an individual’s capacity to adapt to a novel threat in their environment, overcome it, and return to baseline conditions [113]. The foundation of an individual’s resilience is shaped by their genetic predisposition; however, positive and negative experiences or supports can serve to respectively increase or decrease an individual’s resilience, revealing the dynamic nature of resilience (Figure 1) [114]. Positive experiences and supports, or protective factors, include access to educational opportunities and healthcare, positive parent-child relationships, strong family and community networks, and housing, food, and financial security, among others [9]. Conversely, negative experiences and supports, or risk factors, include exposure to war, poverty, lack of familial and community support, ACEs, lack of access to healthcare and education, and housing, financial, and food insecurity, among others [115]. However, the impact of protective and risk factors can vary based on different ideologies (e.g., cultural and religious views) and values (e.g., individual autonomy, family connections), something that is controlled for by allowing the individual themselves to identify protective and risk factors that increase their resilience to mental health conditions [116]. Healthcare providers can therefore apply resilience theory to gain a better understanding of where their clients may lie in terms of their risk of developing mental health conditions and identify appropriate supports and experiences that may help to positively shift their resilience.

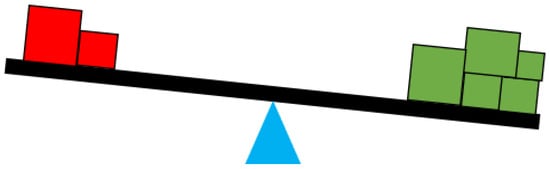

Figure 1.

Resilience scale, where red boxes reflect negative experiences and supports, green boxes reflect positive experiences and supports, and the blue triangle represents genetic resilience. The size of the boxes indicates the weight of correlates that impact experiences and supports. Adapted from: National Scientific Council on the Developing Child [114].

Resilience theory helps to explain why some individuals can experience adverse events and remain functional, positive-minded, and even reap benefits from those experiences, while others who experience the same adverse events may engage in health-damaging behaviors (e.g., substance use) and develop mental health conditions [117]. Although the gravity, timing, and frequency of the adversity are important to consider, resilience theory emphasizes that the way individuals manage adversities is important and a manifestation of their genetic expression, baseline functioning, previous experiences, and current supports and resources [117]. Overall, resilience theory can be a powerful framework that guides treatment of mental health conditions through its capacity of distinguishing (1) between those who are more likely to experience vulnerability and those who are more likely to experience resilience to certain mental health conditions, (2) which present factors are supporting or attenuating an individual’s resilience, and (3) which factors could be integrated into or removed from an individual’s life to increase their resilience [118,119].

Brain structure [120], cognitive functioning [121], and genetics [122] have been linked to greater resilience. Findings from a systematic review revealed that more grey matter volume in the frontal lobe and hippocampus of youth, larger ventral striatum (functions in reward processing [123]) volumes, and greater structural connectivity in the corpus callosum (a bridge connecting the left and right hemispheres of the brain with a prominent role in cognitive processing [124]) are associated with greater resilience to mental health conditions [120]. The hippocampus and amygdala are two parts of the brain that play a pertinent role in the stress response system [125]. Studies have consistently demonstrated a greater risk of developing certain mental health conditions among individuals with greater amygdala functioning and smaller hippocampal brain volumes, which have been associated with a hyperactive response to stress and greater difficulty in returning to homeostasis [64]. Executive function is primarily orchestrated by the prefrontal cortex and has been strongly associated with numerous mental health conditions due to its involvement in planning, organizing, and executing tasks [126]. In a longitudinal study conducted by Wu et al. among 17-to-24-year-olds (n = 420), those with higher executive functioning scores had greater levels of resilience at follow-up compared to those with lower executive functioning scores [121]. Findings from reviews show promising associations between genes and resilience [61,127,128]. Those who are genetically predisposed to having an irregularly active hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, a system that governs our flight, fight, freeze, or fawn response, are more likely to experience hyperactive fear responses or compromised immune functioning, both of which are linked to mental health conditions [10,129]. Further, those born with abnormal chromosome numbers or gene mutations, which undermine appropriate protein expression and physiological functioning, are more likely to experience vulnerability to mental health conditions [130]. All the above examples represent factors that lay the foundation for one’s resilience to mental health conditions; however, other internal and external factors also serve to further influence one’s resilience.

It is important to consider not only exposure to factors that impact resilience and those that are inherited, but also the timing of exposure to such factors. External factors influence one’s resilience to mental health conditions as early as the fetal period, whereby fetal development can be undermined by maternal stress, poor nutrition, and irregular immune functioning during pregnancy; this is a phenomenon known as fetal programming [11]. Akin to this, parents who report strong social support during prenatal and postpartum periods are less likely to report perinatal mental health condition symptoms [131,132]. During infancy and childhood, children who experience positive parenting and support are more likely to exhibit more optimal behavioral development, achievement of developmental milestones, and performance in recreational and academic settings compared to children who experience ACEs or a lack of nurturance and safety [133], all of which are linked to greater quality of life later in life. While children born with developmental delays or disabilities are more likely to experience vulnerabilities associated with mental health conditions, early support from healthcare providers can attenuate, prevent, or even reverse impacts on lifelong physical and mental health outcomes [134]. More relevant to resilience across the lifespan are socioeconomic factors, including educational attainment, employment, income, food and housing security, and access to healthcare [9,135]. Resilience theory ultimately posits risk and protective factors relevant to explaining the etiology of mental health conditions. This knowledge can help healthcare providers to conduct individualized assessments and intervene to promote resilience.

Interventions that aim to increase resilience in individuals often result in better mental health outcomes [136]. Jiang and colleagues conducted a literature review on resilience-based interventions, identifying four different levels: (1) individual-level interventions (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy, psychotherapy), which aim to enhance cognitive functioning, emotional regulation, coping, and stress responses; (2) family-level interventions (e.g., parenting programs), which aim to foster healthier family and social relationships; (3) community-level interventions, which foster a sense of belonging and external perceived social support; and (4) multi-level interventions, which touch on combinations of the first three levels of interventions and target multiple groups or communities (e.g., HIV healthcare pathways) [136]. Empirical evidence supports the application of all the levels of resilience-based interventions on promoting mental health outcomes, especially in children [136], offering attractive opportunities to design and implement effective mental health interventions. Identifying protective factors that an individual deems most important can guide which level of resilience-based intervention will be most conducive to optimizing their mental health.

9. Summary of Theories and Their Strengths and Weaknesses

Each of the theories accounts for the etiology of mental health conditions differently. Though overlap exists, each theory attributes unique factors to the presence or absence of mental health conditions and possesses its own strengths and weaknesses in conceptualizing the etiology of mental health conditions. The factors related to the etiology of mental health conditions and the strengths and weaknesses of each theory (i.e., attachment, intergenerational, intersectionality, queer, social cognitive, resilience) are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

The factors related to mental health conditions and the strengths and weaknesses of each theory.

10. Limitations and Strengths

This review applied narrative review methods. While narrative review methods allow for a flexible approach to synthesizing a large body of literature, rigor, transparency, and reproducibility are reduced due to a non-systematic approach to literature identification [20,21]. Nevertheless, many studies were still reviewed, and this approach allowed for relevant information to be identified and extracted. Further, only Google Scholar was searched to identify relevant studies. However, the use of Google Scholar to search for relevant studies still allowed for many studies to be reviewed, where identified studies were further mined to pinpoint additional literature for data saturation. Lastly, the quality of the identified research was not assessed given that much of the research is naturally theoretical and assessment of research quality is not typically expected when utilizing narrative synthesis methods [20,21]; however, after introducing all six theories, strengths and weaknesses of their application in conceptualizing mental health conditions are provided, helping readers gauge the level and quality of evidence available for each theory in explaining the etiology of mental health conditions.

11. Concluding Remarks

This narrative review explored attachment, intergenerational, intersectionality, queer, social cognitive, and resilience theories as ways of understanding the etiology of mental health conditions, setting a foundation for more structured reviews (e.g., systematic reviews) and additional research to be conducted to better understand how they can each be used to describe the etiology and treatment of mental health conditions. All six theories can be applied differently to conceptualize the etiology of mental health conditions above and beyond the context of ACEs. Further, each theory has its own unique qualities, which can be used in research and practice to elucidate important factors related to mental health conditions. Selection of the theory depends on the level and type of information of interest. Application of more than one theory may be optimal to capitalize on strengths, address identified gaps, and promote a multidisciplinary approach to mental health condition research and treatment.

Author Contributions

S.K. was involved in study conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, supervision, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, and project administration. N.L. was involved in conceptualization, methodology, supervision, resources, writing—review and editing, and project administration. D.D. was involved in conceptualization, methodology, and writing—review and editing. A.D. was involved in conceptualization, methodology, supervision, and writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. What Is Mental Illness? Available online: https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/what-is-mental-illness#:~:text=Mental%20illnesses%20are%20health%20conditions,like%20heart%20disease%20or%20diabetes.&text=More%20than%20one%20in%20five,(including%20alcohol%20use%20disorder) (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Research and Analysis: Mental Health. Available online: https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/health-risks-issues/mental-health-research-library (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- The Lancet Global, H. Mental health matters. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sporinova, B.; Manns, B.; Tonelli, M.; Hemmelgarn, B.; MacMaster, F.; Mitchell, N.; Au, F.; Ma, Z.; Weaver, R.; Quinn, A. Association of mental health disorders with health care utilization and costs among adults with chronic disease. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e199910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, C.; Saka, M.; Bone, L.; Jacobs, R. The role of mental health on workplace productivity: A critical review of the literature. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2023, 21, 167–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J.; Brazier, J.; O’Cathain, A.; Lloyd-Jones, M.; Paisley, S. Quality of life of people with mental health problems: A synthesis of qualitative research. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2012, 10, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, K.C.; Guhn, M.; Richardson, C.G.; Shoveller, J.A. Associations between household educational attainment and adolescent positive mental health in Canada. SSM-Popul. Health 2017, 3, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzol, D.; Trott, M.; Butler, L.; Barnett, Y.; Ford, T.; Neufeld, S.A.; Ragnhildstveit, A.; Parris, C.N.; Underwood, B.R.; López Sánchez, G.F.; et al. Relationship between severe mental illness and physical multimorbidity: A meta-analysis and call for action. BMJ Ment. Health 2023, 26, 300870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, C.A.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Harris, N.B.; Danese, A.; Samara, M. Adversity in childhood is linked to mental and physical health throughout life. BMJ 2020, 371, 3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneiderman, N.; Ironson, G.; Siegel, S.D. Stress and health: Psychological, behavioral, and biological determinants. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 1, 607–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glover, V. Prenatal stress and its effects on the fetus and the child: Possible underlying biological mechanisms. In Perinatal Programming of Neurodevelopment; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 269–283. [Google Scholar]

- Braveman, P.; Gottlieb, L. The social determinants of health: It’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public. Health Rep. 2014, 129 (Suppl. S2), 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.; Loureiro, A.; Cardoso, G. Social determinants of mental health: A review of the evidence. Eur. J. Psychiatry 2016, 30, 259–292. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. An attachment perspective on psychopathology. World Psychiatry 2012, 11, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, M. The use of family theory in clinical practice. Compr. Psychiatry 1966, 7, 345–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbado, D.W.; Crenshaw, K.W.; Mays, V.M.; Tomlinson, B. INTERSECTIONALITY: Mapping the Movements of a Theory. Du. Bois Rev. 2013, 10, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semp, D. Questioning heteronormativity: Using queer theory to inform research and practice within public mental health services. Psychol. Sex. 2011, 2, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberta Family Wellness Initiative. Report 1 of 3: Brain Story: Using the Resilience Scale as a Tool for Individuals; Alberta Family Wellness Initiative: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sukhera, J. Narrative Reviews: Flexible, Rigorous, and Practical. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2022, 14, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, S.S.; Barak, G.; Truong, G.; Parker, M.W. Hierarchy of Evidence Within the Medical Literature. Hosp. Pediatr. 2022, 12, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Harlow, H.F.; Zimmermann, R.R. The Development of Affectional Responses in Infant Monkeys. Proc. Am. Philos. Soc. 1958, 102, 501–509. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, M.D.; Bell, S.M. Attachment, exploration, and separation: Illustrated by the behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. Child. Dev. 1970, 41, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, D. Infant-parent attachment: Definition, types, antecedents, measurement and outcome. Paediatr. Child. Health 2004, 9, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sroufe, L.A. Attachment and development: A prospective, longitudinal study from birth to adulthood. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2005, 7, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Mendonça Filho, E.J.; Frechette, A.; Pokhvisneva, I.; Arcego, D.M.; Barth, B.; Tejada, C.-A.V.; Sassi, R.; Wazana, A.; Atkinson, L.; Meaney, M.J.; et al. Examining attachment, cortisol secretion, and cognitive neurodevelopment in preschoolers and its predictive value for telomere length at age seven. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 954977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groh, A.M.; Narayan, A.J. Infant Attachment Insecurity and Baseline Physiological Activity and Physiological Reactivity to Interpersonal Stress: A Meta-Analytic Review. Child. Dev. 2019, 90, 679–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruit, A.; Goos, L.; Weenink, N.; Rodenburg, R.; Niemeyer, H.; Stams, G.J.; Colonnesi, C. The Relation Between Attachment and Depression in Children and Adolescents: A Multilevel Meta-Analysis. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 23, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumariu, L.E.; Kerns, K.A. Mother-Child Attachment and Social Anxiety Symptoms in Middle Childhood. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 29, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, K.; Horowitz, L.M. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 61, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Ash, J. Anxiety and Attachment Styles: A Systematic Review; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Xie, F.; Chen, X.; Xu, W.; Hudson, N.W. The relationship between adult attachment and mental health: A meta-analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 123, 1089–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditzen, B.; Schmidt, S.; Strauss, B.; Nater, U.M.; Ehlert, U.; Heinrichs, M. Adult attachment and social support interact to reduce psychological but not cortisol responses to stress. J. Psychosom. Res. 2008, 64, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraley, R.C.; Hudson, N.W.; Heffernan, M.E.; Segal, N. Are adult attachment styles categorical or dimensional? A taxometric analysis of general and relationship-specific attachment orientations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 109, 354–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraley, R.C.; Waller, N.G. Adult attachment patterns: A test of the typological model. In Attachment Theory and Close Relationships; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 77–114. [Google Scholar]

- De Wolff, M.S.; Van Ijzendoorn, M.H. Sensitivity and attachment: A meta-analysis on parental antecedents of infant attachment. Child. Dev. 1997, 68, 571–591. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- van Ijzendoorn, M.H.; Schuengel, C.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J. Disorganized attachment in early childhood: Meta-analysis of precursors, concomitants, and sequelae. Dev. Psychopathol. 1999, 11, 225–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letourneau, N.; Tryphonopoulos, P.; Giesbrecht, G.; Dennis, C.L.; Bhogal, S.; Watson, B. Narrative and meta-analytic review of interventions aiming to improve maternal-child attachment security. Infant. Ment. Health J. 2015, 36, 366–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, J.; Theule, J. Maternal depression and infant attachment security: A meta-analysis. Infant. Ment. Health J. Infancy Early Child. 2019, 40, 817–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, J.E.; Racine, N.; Pador, P.; Madigan, S. Maternal Adverse Childhood Experiences and Child Behavior Problems: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2020044131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppert, F.A.; Abbott, R.A.; Ploubidis, G.B.; Richards, M.; Kuh, D. Parental practices predict psychological well-being in midlife: Life-course associations among women in the 1946 British birth cohort. Psychol. Med. 2010, 40, 1507–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanvictores, T.; Mendez, M.D. Types of Parenting Styles and Effects on Children; StatPearls [Internet]: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lanjekar, P.D.; Joshi, S.H.; Lanjekar, P.D.; Wagh, V. The effect of parenting and the parent-child relationship on a child’s cognitive development: A literature review. Cureus 2022, 14, e30574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, M.; Kannis-dymand, L.; Sharman, R. A review of attachment-based parenting interventions: Recent advances and future considerations. Aust. J. Psychol. 2020, 72, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsky, J.; Jonassaint, C.; Pluess, M.; Stanton, D.; Brummet, B.; Williams, R. Vulnerability genes or plasticity genes? Mol. Psychiatry 2009, 14, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaoka, Y.; Bard, D.E. Positive Parenting Matters in the Face of Early Adversity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 56, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurbatfinski, S.; Woo, J.; Ntanda, H.; Giesbrecht, G.; Letourneau, N. Perinatal Predictors and Mediators of Attachment Patterns in Preschool Children: Exploration of Children’s Contributions in Interactions with Mothers. Children 2024, 11, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, B.; Fearon, P.; Garside, M.; Tsappis, E.; Amoah, E.; Glaser, D.; Allgar, V.; Minnis, H.; Woolgar, M.; Churchill, R.; et al. Routinely used interventions to improve attachment in infants and young children: A national survey and two systematic reviews. Health Technol. Assess. 2023, 27, 1–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucci, S.; Roberts, N.H.; Danquah, A.N.; Berry, K. Using attachment theory to inform the design and delivery of mental health services: A systematic review of the literature. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2015, 88, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letourneau, N.; Kurbatfinski, S.; Ross, K.; Anis, L.; Cole, S.; Hart, M. Promoting optimal relationships and the health of parents and children: Findings of the Attachment and Child Health (ATTACH™) program for families experiencing vulnerabilities. Devenir 2024, 36, 114–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. Boosting Attachment Security to Promote Mental Health, Prosocial Values, and Inter-Group Tolerance. Psychol. Inq. 2007, 18, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, C.A.; McEwen, B.S. Social Structure, Adversity, Toxic Stress, and Intergenerational Poverty: An Early Childhood Model. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2017, 43, 445–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomanowska, A.M.; Boivin, M.; Hertzman, C.; Fleming, A.S. Parenting begets parenting: A neurobiological perspective on early adversity and the transmission of parenting styles across generations. Neuroscience 2017, 342, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, N.; Deneault, A.-A.; Thiemann, R.; Turgeon, J.; Zhu, J.; Cooke, J.; Madigan, S. Intergenerational transmission of parent adverse childhood experiences to child outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child. Abus. Negl. 2023, 2023, 106479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, K.C.; Jones, C.W.; Wade, M.; Callerame, K.; Smith, A.K.; Theall, K.P.; Drury, S.S. Adverse Childhood Experiences: Implications for Offspring Telomere Length and Psychopathology. Am. J. Psychiatry 2020, 177, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lê-Scherban, F.; Wang, X.; Boyle-Steed, K.H.; Pachter, L.M. Intergenerational Associations of Parent Adverse Childhood Experiences and Child Health Outcomes. Pediatrics 2018, 141, e20174274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Larsson, H.; D’Onofrio, B.M.; Landén, M.; Lichtenstein, P.; Pettersson, E. Intergenerational Transmission of Psychiatric Conditions and Psychiatric, Behavioral, and Psychosocial Outcomes in Offspring. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2348439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffee, S.R.; Price, T.S. Gene–environment correlations: A review of the evidence and implications for prevention of mental illness. Mol. Psychiatry 2007, 12, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niitsu, K.; Rice, M.J.; Houfek, J.F.; Stoltenberg, S.F.; Kupzyk, K.A.; Barron, C.R. A Systematic Review of Genetic Influence on Psychological Resilience. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2019, 21, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdá, M.; Sagdeo, A.; Johnson, J.; Galea, S. Genetic and environmental influences on psychiatric comorbidity: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 126, 14–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, A.J.; Lieberman, A.F.; Masten, A.S. Intergenerational transmission and prevention of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 85, 101997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurbatfinski, S.; Dosani, A.; Dewey, D.M.; Letourneau, N. Proposed Physiological Mechanisms Underlying the Association between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Mental Health Conditions: A Narrative Review. Children 2024, 11, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roubinov, D.S.; Luecken, L.J.; Curci, S.G.; Somers, J.A.; Winstone, L.K. A prenatal programming perspective on the intergenerational transmission of maternal adverse childhood experiences to offspring health problems. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowers, M.E.; Yehuda, R. Intergenerational Transmission of Stress in Humans. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016, 41, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.B.; Riley, A.W.; Granger, D.A.; Riis, J. The science of early life toxic stress for pediatric practice and advocacy. Pediatrics 2013, 131, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, C.S.; Callaghan, B.L.; Kan, J.M.; Richardson, R. The lasting impact of early-life adversity on individuals and their descendants: Potential mechanisms and hope for intervention. Genes. Brain Behav. 2016, 15, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, G.A.; Smallegange, E.; Coetzee, A.; Hartog, K.; Turner, J.; Jordans, M.J.D.; Brown, F.L. A Systematic Review of the Evidence for Family and Parenting Interventions in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Child and Youth Mental Health Outcomes. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 2036–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sager, A.; Goodman, S.H.; Jeong, J.; Bain, P.A.; Ahun, M.N. Effects of multi-component parenting and parental mental health interventions on early childhood development and parent outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health 2024, 8, 656–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.; Sargent, J. Overview of the Evidence Base for Family Interventions in Child Psychiatry. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 24, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourque, V.-R.; Poulain, C.; Proulx, C.; Moreau, C.A.; Joober, R.; Forgeot d’Arc, B.; Huguet, G.; Jacquemont, S. Genetic and phenotypic similarity across major psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and quantitative assessment. Transl. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, I.E.; Graham, D.P.; Soares, J.C.; Nielsen, D.A. Serotonergic Gene Variation in Substance Use Pharmacotherapy: A Systematic Review. Pharmacogenomics 2015, 16, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, E.G.; Ijadi-Maghsoodi, R.; Shadravan, S.; Moore, E.; Mensah, M.O., 3rd; Docherty, M.; Aguilera Nunez, M.G.; Barcelo, N.; Goodsmith, N.; Halpin, L.E.; et al. Community Interventions to Promote Mental Health and Social Equity. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; van Ours, J.C. Mental health effects of same-sex marriage legalization. Health Econ. 2022, 31, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. On Intersectionality: Essential Writings; The New Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanf. Law. Rev. 1991, 43, 1241–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, L.; Wislar, W. Physical and Mental Health Disparities at the Intersection of Sexual and Gender Minority Statuses: Evidence From Population-Level Data. Demography 2023, 60, 731–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roubinov, D.; Browne, D.; LeWinn, K.Z.; Lisha, N.; Mason, W.A.; Bush, N.R. Intergenerational transmission of maternal childhood adversity and depression on children’s internalizing problems. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 308, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattari, S.K.; Walls, N.E.; Speer, S.R. Differences in Experiences of Discrimination in Accessing Social Services Among Transgender/Gender Nonconforming Individuals by (Dis)Ability. J. Soc. Work. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 16, 116–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kattari, S.K.; Walls, N.E.; Whitfield, D.L.; Langenderfer-Magruder, L. Racial and ethnic differences in experiences of discrimination in accessing health services among transgender people in the United States. Int. J. Transgenderism 2015, 16, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurbatfinski, S.; Letourneau, N.; Marshall, S.; McBride, D.; Novick, J.; Griggs, K.; Perrotta, A.; Daye, M.; McManus, C.; Nixon, K. Myths and misconceptions of intimate partner violence among sexual and gender minorities: A qualitative exploration. Front. Sociol. 2024, 9, 1466984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotter, A. Perceptions of and experiences with police and the justice system among the Black and Indigenous populations in Canada. Juristat Can. Cent. Justice Stat. 2022, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe, E.A.; Smart Richman, L. Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 135, 531–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelemy, L.; Cotton, S.; Crane, C.; Knight, M. Systematic review of prospective adult mental health outcomes following affirmative interventions for gender dysphoria. Int. J. Transgender Health 2024, 27, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, M.C.; Price, E.G.; Gary, T.L.; Robinson, K.A.; Gozu, A.; Palacio, A.; Smarth, C.; Jenckes, M.W.; Feuerstein, C.; Bass, E.B.; et al. Cultural competence: A systematic review of health care provider educational interventions. Med. Care 2005, 43, 356–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Beal, E.W.; Okunrintemi, V.; Cerier, E.; Paredes, A.; Sun, S.; Olsen, G.; Pawlik, T.M. The Association Between Patient Satisfaction and Patient-Reported Health Outcomes. J. Patient Exp. 2019, 6, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhurst, P.; Full, W. Disabled people’s perceptions and experiences of accessing and receiving counselling and psychotherapy: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e069204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, R.S.; Rogers, C.C.; Claypool, H.; Trieshmann, L.; Frye, O.; Wellbeloved-Stone, C.; Kushalnagar, P. Ensuring full participation of people with disabilities in an era of telehealth. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 2021, 28, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkman, A.H.; Rea-Sandin, G.; Lund, E.M.; Fitzpatrick, O.M.; Gusman, M.S.; Boness, C.L. Shifting the discourse on disability: Moving to an inclusive, intersectional focus. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2023, 93, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spurlin, W.J. Queer Theory and Biomedical Practice: The Biomedicalization of Sexuality/The Cultural Politics of Biomedicine. J. Med. Humanit. 2019, 40, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorri, A.A.; Stone, A.L.; Salcido, R., Jr.; Russell, S.T.; Schnarrs, P.W. Sexual and gender minority adverse childhood experiences (SGM-ACEs), perceived social support, and adult mental health. Child. Abus. Negl. 2023, 143, 106277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnarrs, P.W.; Stone, A.L.; Bond, M.A.; Salcido, R.; Dorri, A.A.; Nemeroff, C.B. Development and psychometric properties of the sexual and gender minority adverse childhood experiences (SGM-ACEs): Effect on sexual and gender minority adult mental health. Child. Abus. Negl. 2022, 127, 105570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]