Abstract

The current paper studies the 2022 parliamentary election campaign, in regards to what extent and quality certain elements of political debate can appear in political actors’ social media communication. During our research, we analyzed 2441 Facebook posts from parties and party leaders prior to the election. According to our results, political actors engage in opinionated discourse on social media and largely focus on public policy issues. They rarely rely on factual reasoning; instead, they tend to use individual phenomena to justify their claims. Ad hominem fallacy also plays a significant role in their Facebook posts when they are making an argument. However, other argumentation errors, so-called fallacies are quite rare in their communication. The main patterns are similar between the actors, but in general, parties and politicians from the opposition are more argumentative compared to the ruling party coalitions.

1. Introduction

Politics Is Always Answering and Waiting for an Answer

These are words from István Schlett (2018, p. 26), a Hungarian political thinker, who argues that political texts and speeches are always up for debate, they constantly representing an opinion and a counter-opinion. This plurality of different ideas gives a unique discursive character to politics, which is so inherent in its nature that if there is no counter-opinion, politicians tend to create one just to argue against it.

There is extensive literature on how politicians can successfully deploy their messages to voters, but in general, less attention has been paid to how political actors interact with each other and each other’s views (but see, e.g., Maier and Renner 2018). Nonetheless, it still has merits for further investigation since the dialogue between opposing political actors can indeed affect the people’s opinion on them and on their political offers. Political argumentation, however, is not a two-way dialogue between the debaters but a battle of interpretations in which political actors are trying to convince the audience about their political offer and devalue the opponents’ (Szabó 2003, p. 139).

The phenomenon of the public dispute has a long tradition in political communication, but only a handful of debate forms have become fully established practices in Hungary. It is increasingly uncommon to see two politicians, one from the opposition and one from a governing party reacting to each other’s arguments in a certain speech event. There are several factors that determine the nature of public disputes, such as the power imbalance between the government and the opposition, (Körösényi et al. 2020), the extremely high political polarization (Patkós 2019), or the transformation/colonization of the press and media (Bajomi-Lázár 2021). In the highly partisan media context, political actors mostly appear in outlets with positive attitude toward them, and this way the opportunity of direct verbal clashes are increasingly limited. As the Hungarian public sphere has radically changed over the years, social media have become a crucial platform for political communication (Bene and Szabó 2021). On Facebook, for example, political leaders and parties can reach large masses of voters directly, without having to engage with the press or traditional forms of media such as cable television. This one-to-many structure of communication does not mean, however, that political debate has no place on these platforms; political actors can express their subjective opinions and justify them with factual reasoning or even with fallacious arguments. On Facebook, they can also react to similar statements by their rivals and allies. Political actors’ social media communication aims to target the larger audience even when they seemingly interacting with each other, they tend to make an argument to a mass of voters, hence it can change their argumentation strategy from resolving a difference of opinion to influence the public discourse. It is therefore worth examining to what extent elements of the traditional political debate have been transferred to the online space.

When the Election Day approaches, political actors make significant efforts to influence and thematize public discourse with their own messages and their reactions to other’s opinions to prove the relevance of their political offers using their parties’ or their personal social media pages. With the growing prevalence of online campaigns and the viral spread of fake news and disinformation campaigns (Bennett and Livingston 2018) it is particularly important if politicians are able to or willing to justify their arguments on certain issues which can affect the entire country. It is therefore worth examining not only what they say, but also how they say it. This is a particularly important question in the discursive space of social media, where political actors’ statements cannot be directly challenged by fellow debaters or external moderating actors (e.g., journalists), making it easier to support claims with fallacious reasoning or unreliable evidence. Naturally, these statements can be reacted by other actors in form of comments, shares or response posts, but these reactions are less visible for the direct followers and recipients of the particular post. In this study, we aim at investigating the role of argumentation in Facebook communication during election campaigns and how elements of the normative ideal of political debate emerge in indirect dialectical relations; to what extent (1) political actors react to each other’s statements, (2) present their subjective opinions in their posts, (3) make their arguments in line with the rules of pragma-dialectics of rational debate, and (4) support the presented information with facts. To summarize our research questions, we aim to answer the question that to what extent and in what quality certain elements of ideal political debate appear in political actors’ Facebook communication.

To answer these research questions, we conducted a quantitative content analysis on the Facebook activity of political parties and leaders during the 2022 Hungarian parliamentary election campaign. In the next section, we briefly discuss argumentation theory that provides an analytical framework for our research and the elements of classical debate that are searched in politicians’ Facebook posts. In this section, we also record our three research questions, which aim to map the interactions between politicians, i.e., (1) to what extent actors express subjective opinions, (2) how often they react to each other or to certain phenomena, and (3) what argumentation strategies and argumentation errors, so-called fallacies, they use in their Facebook posts. We then present the methodology and the results of our research and draw conclusions at the end of the paper.

2. The Culture of Political Debate in Hungary

Nowadays, the idea of the declining extent and quality of political debate culture in Hungary is often reiterated in both public and academic discourse (Szabó and Farkas 2021). However, it is not easy to define what exactly they mean by this phenomenon. It is not true that there are no political debates at all; during the opposition primaries, for example, parties organized a record number of candidate debates, and in the parliament, MPs regularly pose questions to each other on issues of public concern. Nonetheless, it is not only the decreasing number of debates but also the quality of the existing ones is often criticized. Quality can be captured by the characteristics of the participants, their preparation, the quality of the arguments, and the environment where the dispute takes place. For example, the above-mentioned debates took place in a context characterized by imbalanced political power relationships; there were no candidates from the government party in the primaries organized by opposition parties, and in case of the parliamentary debates the opposition has no substantive say in the legislature due to the two-thirds majority of the government parties. For more than a decade, there was hardly any speech event where a pro-government and an opposition politician engaged in a direct dialectical interaction and attempted to refute each other’s positions with arguments to resolve the controversy. This would be what is defined as a debate in the classical sense (Eemeren et al. 2002, p. 11).

It may seem that classical debate models are disappearing from the Hungarian political discourse, but arguments and dialogues are still integral parts of the communication ecosystem, so it is safe to say that debate is “transforming rather than vanishing” in Hungarian politics. In order to gain and maintain voter support, political actors have to constantly justify their political goals and actions, and interpret certain events and phenomena in a way that aligns with their political goals. This process of interpretation and justification takes place through a series of arguments. The literature of argumentation, the so-called pragma-dialectics, classifies political communication as a type of public communicative activity, called deliberation. It involves the varied use of argumentative communicative activities by participants to discuss issues on which the debating parties but also the audience hold different views (Eemeren and Peng 2017, pp. 129–35). According to the study of pragma dialectics, during a deliberative communicative activity, argumentation is mostly directed toward the third party, the audience, so the debaters’ aim is to influence the public rather than convincing each other or resolving a disagreement. In other words, when politicians engage in dialogue with another actors, they are less interested in convincing their rivals, instead they focus on persuading the audience, i.e., the electorate, and they adopt a communication strategy in line with this goal (Strömbäck and Kiousis 2014). Important to note that in political science deliberation often refers to a direct exchange of arguments in which political actors are focusing on a transparent debate representing every opinion thus resulting a compromise in decision-making. In this study however, we are using the definition of deliberation presented by Eemeren, which focuses the nature of political debate and the debater’s strategies rather than deliberation as a form of democratic practice (Habermas 1996).

In social media, however, most of the arguments are no longer conducted through a direct dialectical relationship, instead, political actors react to each other’s positions via certain platforms. Social media allow politicians to reach the masses of voters without the intermediary role of journalists who may try to filter, comment on or criticize their messages. In the Hungarian context, the imbalanced power relations between the government and the opposition (Körösényi et al. 2020) and the decline of pluralistic media space (Bajomi-Lázár 2021) has also contributed to this pattern; government parties control several media channels to deliver their messages with supportive journalistic framing to a wide segment of the electorates. In this context, from their perspective, it is a risk to directly engage with opposition political actors in a controlled debate situation. However, even though politicians have few opportunities to engage in direct debates, they still can react to each other’s statements and express their subjective opinions via their social media pages. Social media has become a crucial communication tool in politics; Hungarian politicians actively use various platforms, especially Facebook (Bene and Farkas 2022). In addition to making their own political work visible to their followers, they can also express subjective opinions, and react to events, decisions and each other in the online space without journalists or political opponents being able to directly question or challenge the statements they made. To gain a deeper understanding of the contemporary debate culture, it is therefore essential to focus on political actors’ arguments on social networking sites.

3. The Theory of Pragma Dialectics

Contemporary approaches on argumentation theory distinguish different types of communicative activities where there is a direct dialectical relationship between the actors in a debate. However, as online communication has become a central context of public discourse, it is necessary to examine the argumentative discourse on the Internet, where interactions occur in different time and space via unfiltered online platforms. Studies have already addressed the effects of the media on argumentation (Rinke 2016) and the argumentative errors in the rhetoric of populist politicians (Blassnig et al. 2019), but less attention has been paid to argumentative activities on social media platforms. There are some studies with related topics, which indicates that it is worth to examine online argumentation between political actors. For example, Heiss et al. (2019) demonstrated that reasoning is rewarded by followers as these posts provoke more likes, comments and shares. In addition, Jost (2022) showed that position-taking result in higher amount of user engagement on Facebook. The aim of this paper is to examine the extent to which social media is an area of indirect political debate situations if it means a rationality-driven, fallacy-free exchange of ideas between political actors. Traditional debate models are disappearing from political discourse, but as they are increasingly moving to the online space, certain argumentative elements may still appear there. We are therefore interested in the extent to which the social media activities of political actors can replace or supplement traditional political debate by creating a kind of indirect dialogical space where opinions, arguments, and reactions to each other’s statements circulate.

A prerequisite for political debate is that different subjective opinions are formulated by the parties. According to the literature, the first condition for a dispute is the realization of the differences of opinion which is recorded at the debate’s confrontation stage (Eemeren and Grootendorst 1984, p. 85). Our first research question, therefore, focuses on the extent to which political actors give space to the expression of their own subjective opinions on Facebook (RQ1). The articulation of opinions also serves to set the political agenda, and declares which issues political actors consider important by expressing an opinion on them and thus generates discourse around them.

Subjective opinions are necessary but not sufficient preconditions for debate. For argumentation, parties must also enter into a discourse with each other, which they can do by reacting to each other’s positions (Eemeren and Grootendorst 1984, p. 86). Therefore, in our second research question, we investigate the extent to which political actors on Facebook react to the views of other speakers and how they do this (RQ2). In the digital public sphere actors may seek to influence the audience by reacting to the position of another politician. Reactions may be positive or negative and may include subjective opinions and facts, supported by arguments and evidence to make it more convincing.

Finally, the quality of arguments is also examined (RQ3). Arguments are essential for the debate to take place and are used to justify positions. An argument typically consists of a premise and a conclusion, the conclusion being the debater’s position itself, and the premise being the argument or arguments with which he or she wishes to support his or her claims (Henkemans and Francisca 1997). Ideally, the arguer will present facts in a logically plausible way to prove his or her position, so that their conclusion clearly follows from the premises. It follows that the strength of the argument is influenced by the evidence cited and the relationship between the argument and the conclusion. The evidence is easier to analyze, while understanding arguments requires the analytical framework of argumentative fallacies provided by pragma-dialectics.

4. Fallacious Arguments and Their Types

Argumentation theory relies on a linear model of critical debate, which is designed to resolve differences of opinion through a predetermined set of rules. Within this structured set of rules, scholars have identified a number of argumentation schemas and argumentation errors, the so-called fallacies (Eemeren et al. 2002, pp. 182–83). Among argumentation errors, we can distinguish formal and informal fallacies. Formal fallacies are those which are readily seen to be instances of invalid logical forms. Informal fallacies are also invalid arguments, but pragma-dialectics bring their weaknesses to light through analyses that do not involve appeal to formal languages (Hansen 2020; Walton 1995). Examples include loose connections between conclusion and premise, exaggerated statements, or incorrect use of metaphors.

It is important to note that the prescriptive rules of pragma dialectics, which is the normative idea of rational debate is a purely methodological tool in our study. As explained above, political debate, even in direct contact, does not satisfy the premises of rational, or critical debate, i.e., the resolution of a difference of opinion or finding the ‘objective’ truth. In the course of their election campaigns, parties and party leaders using logical and rhetorical means to achieve further political capital not to convince each other. However, this does not mean, that the argumentation schemes defined by the literature cannot be reconstructed in the social media utterances of politicians.

Strategic maneuvering has been developed to complement the theory of the critical debate model. It examines the arguments in a debate based on their rhetorical effectiveness and dialectical reasonableness. Strategic maneuvering also extends the approach in the sense that disputants no longer engage in debate merely to resolve differences of opinion, but also to ensure that this resolution is to their advantage (Eemeren 2010, pp. 25–28). Strategic maneuvering is a more descriptive approach to analyze why actors opt for specific argumentative strategies based on audiance demand, and their presentational functions and topical potential (Eemeren and Peng 2017, p. 7). Based on this approach, the arguments should be not only logically coherent but also have a rhetorical impact on the debaters. Strategic maneuvering presupposes that the parties do not aiming to participate in a transparent truth discourse, they rather try to influence the audience about their own ideas using any means available to them in the margin of communication.

Some studies have focused on the strategic use of fallacies, in which politicians use flawed arguments to justify their overly strong claims to the public (Zurloni and Anolli 2010). Hence, the third research question of our study, seeks to answer: how do political actors argue on social media? In this context, we will examine the premises politicians use to justify they subjective opinions, and the extent to which the argumentation errors identified by pragma-dialectics are typical of their communication.

First, to examine argumentation patterns (RQ3a), a preliminary literature review was carried out to collect the most common argumentation errors in politics. Informal fallacies reveal logical deficiencies in argumentation, but in many cases, political leaders use them strategically in their communication for their rhetorical effectiveness. One of the cases examined is the group of ad hominems, which can be defined as attacks on speaker rather than the statement. In this case, the political actor does not attack his or her opponent’s argument, but the opponent herself, thus breaking the rules of rational debate and making it impossible to revise positions (Walton 2008, p. 170). Ad hominem is more than mere mockery and negative campaigning as it requires that it should be made in response to the position of the debating partner. Another common argumentative strategy is the appeal to emotions. The politician finds something threatening or pleasing, for example, “the government is running a mafia state, which is extremely upsetting”. This is considered a flawed argument, as it seeks to appeal to the electorate through emotion rather than logical argument (Walton 2008, p. 106). The third commonly used but flawed argument is the appeal to the majority, i.e., ad populum, e.g., “The government is lying because nobody believes it anymore”. Here, the politician is trying to support a very strong opinion by merely assuming public sentiment, which is obviously not sufficient proof (Walton 2008, pp. 107–8). The next category under consideration is faulty generalization, i.e., when a politician assumes that his opponent’s position is untrue because he belongs to a particular social or political group. This is also considered an error of reasoning, but in politics, we often hear implicit or explicit examples of this (Blassnig et al. 2019), for example, “the government is running a mafia state because Pál Volner from the governing Fidesz party took bribes.” The ‘slippery slope’ argument asserts that a proposed, relatively small, first action will inevitably lead to a chain of related events resulting in a significant and negative outcome. The probability of the set of consequences are very low in reality, yet the actor presents them as inevitable (Walton 2008, p. 22). These are also logically incorrect; however, politicians often threaten with ‘fatal’ outcomes.

More often than not, these categorizations can overlap, since argumentation errors are rarely explicit enough that they can easily be revealed by lay audience. In order to resolve the confusion between these categories, we included several examples in our codebook to help the data collecting.

In a second step, we will look into the tools used by political actors to justify their statements in their Facebook posts. A claim can be supported by fact-based evidence such as data/statistics, expert opinion or legal sources (RQ3b). While the use of these sources can be also misleading, deceptive, or even false, they still facilitate rational debate and reflection by being verifiable and factually questionable. Conversely, when a political actor cites a specific phenomenon to support an argument on his or her opinion by arguing that since this isolated phenomenon happened this way, this is evidence on a general lesson, the scope for rational debate is reduced. An isolated phenomenon is rarely clear evidence and it is easy to be contrasted with another isolated phenomenon that contradicts the asserted fact, and this way the argument and the claim remain unprovable. This is also the case when a factual claim is taken-for-granted as a common sense within the society. It is impossible to prove that the claim is truly a common sense, and also a ‘common knowledge’ claim does not prove that it is a true claim. Therefore, it can be argued that an argument is of a higher quality when it contains at least ‘fact-based’ sources, such as data, expert opinions, and legal argument compared to when it is justified by individual phenomena and ‘self-evident truths’. However, it is also important to note that research showed using evidence in argumentation is not clearly rewarded by voters (e.g., Levasseur and Dean 1996) which may demotivate political actors to pursue more evidence-based communication.

5. Methodology

The research used content analysis to examine the Facebook communications of Hungarian parties and party leaders during the 2022 campaign. We choose to analyze political parties Facebook pages as well, because we believe in social media they participate in the discourse as they sharing the party’s general opinion on several topics thus they manifesting as a political actor in the online sphere. For this purpose, the central pages of the parties’ websites (Fidesz, Christian Democratic People’s Party (KDNP), Democratik Coalition (DK), Jobbik, Momentum Movement, Hungarian Socialist Party MSZP, LMP, and Párbeszéd), the leaders of these parties, and Péter Márki-Zay, joint opposition candidate for Prime Minister, were downloaded using the CrowdTangle application during the last four weeks of the campaign, i.e., between 7 March and 3 April 2022. In the case of the radical right party, Mi Hazánk, the party leader did not have a Facebook page, and the party page was deleted by Facebook during the campaign, so we were unable to access the previously downloaded posts at the time of coding. Downloading was carried out daily. In the case of parties with a co-leadership system, only one co-chair was included, namely the one who had shown more activity on Facebook in the week before the data collection; Ágnes Kunhalmi for MSZP, Máté Kanász-Nagy for LMP and Tímea Szabó for Párbeszéd. Table 1 gives a short summary about the parties and leaders under investigation.

Table 1.

Parties and leaders included in the sample.

The content analysis sample included all published posts for leaders (N = 1335) and a 50% random sample of published posts for parties (N = 1106). In the latter case, the sampling was necessary because parties posted significantly more content than political leaders. Posts were categorized according to the code book of the international research network DigiWorld1, but the internationally used code book was supplemented with some additional categories-in this analysis we mostly focus on these. Most of our variables were treated as dummy variables with two values, i.e., if the item is present in the post, the variable takes the value 1, if it is not present, it takes the value 0.

This meant that coders had to record if the post contained the political actor’s own opinion, an explicit reaction to another political actor’s statement, the nature of the reaction (positive, negative, neutral) (coded only if reaction is included), one of the listed argumentation errors (ad hominem, negative emotional argument, positive emotional argument, ad populum, generalization, slippery slope), and the source used to prove the factual statements (data, expert, law, common sense, specific case) (for the description of the categories, see the Appendix A, Appendix B, Appendix C, Appendix D, Appendix E and Appendix F). Coding was carried out by four coders between 20 April and 30 June. To check the reliability of the coding, an inter-coder reliability test was conducted on a random sample of 100 items. The Brennan-Prediger kappa coefficient was above the high-reliability value of 0.8 for most variables, only with subjective opinion (0.61) and perceptual error of generalization (0.62) reaching lower values. The material to be coded was randomly distributed among the four coders so that systematic coder bias does not prevail on an actor-specific basis.

6. Results

6.1. Reactions and Opinions

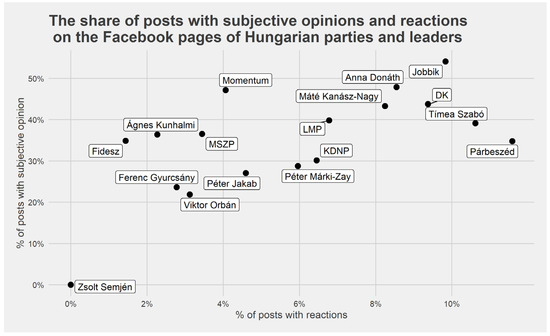

In our first two research questions, we focus on the proportions of subjective opinions and reactions that political actors display on their own sites during the election campaign (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The percentage of opinion and reaction posts made by Hungarian party leaders and parties on Facebook.

As shown in Figure 1, subjective opinions are relatively common, while reactions are less frequent in party- and politician-posts. Only 6% of all the posts analyzed contain a reaction, but 35% of them express some kind of opinion. The vast majority of the reactions were negative, with only 16% of the posts being positive and 9% of the reactions between politicians being neutral. Opinions appear more often than reactions at each politician, but the results also show significant differenc between political actors. The Jobbik stands out in the table, with 54% of posts expressing an opinion, and also responding to a statement or person twice as often as the average, in 10% of posts. Jobbik was followed by Anna Donáth the leader of Momentum and the DK with 48% and 44% of opinions/posts ratio. The Momentum leader and the DK reacted in 9% of their posts. Other members of the opposition coalition also expressed their opinions frequently, with the Momentum Movement (46%), LMP-leader, Máte Kanász-Nagy (43%), LMP (40%) and Tímea Szabó the leader of Párbeszéd (39%) at the top of the scale. Of the political leaders and parties we surveyed, Zsolt Semjén, the leader of KDNP, was at the bottom of the list with 0 reactions or opinions. Ferenc Gyurcsány the leader of DK and Viktor Orbán prime minister (Fidesz) expressed their opinions in 23% and 21% of their posts, respectively. The DK’s leading politician (Ferenc Gyurcsány) reacted to the opinions of others much less often than his party, in only 3% of posts, as did the Prime Minister. Péter Jakab, in contrast to his party’s Jobbik Facebook page, does not often express his opinion (27%) and does not often react to others’ posts (5%). Péter Márki-Zay, the prime ministerial candidate of the united opposition, expressed his own opinion in only 29% of his posts during the campaign, while he reacted to other politicians in only 6% of his posts.

The data shows that opposition pages are generally more reactive than the governing parties, with the exception of the KDNP’s Facebook page, which has a high rate of reactions (7%). Facebook pages of Ferenc Gyurcsány (DK) (3%), the MSZP (3%) and Ágnes Kunhalmi (MSZP) (2%) are the exceptions in the opposition sphere, as they share reactions to other politicians or parties less frequently.

It was also found that more individual opinions appear on the opposition pages, although Fidesz as a party also relatively often shares subjective opinions with users (35%). Ferenc Gyurcsány (DK), Péter Jakab (Jobbik) and Péter Márki-Zay (PM candidate of the opposition) are exceptions in the opposition side, as they infrequently display individual opinions in their posts. It is noteworthy that for Jobbik, DK and KDNP there is a remarkable difference between the party page and the party leader’s page. In all three cases, the party page is much more argumentative, while the party leaders are less so. Fidesz follows a similar strategy when it comes to communicating its views, with the party page much more often using subjective messages than the Prime Minister himself. In contrast, in the case of Párbeszéd, LMP and MSZP, the strategy of the party leader and the party side is very similar in terms of communicating opinions, and in the case of Momentum, the party leader’s reactivity and opinionated communication go beyond the party itself.

These observations suggest that two different communication strategies exist; some parties organize the political agenda via the party pages and the leaders engage in a less argumentative communication, while for other actors the party and party leaders simultaneously communicate opinions and reactions.

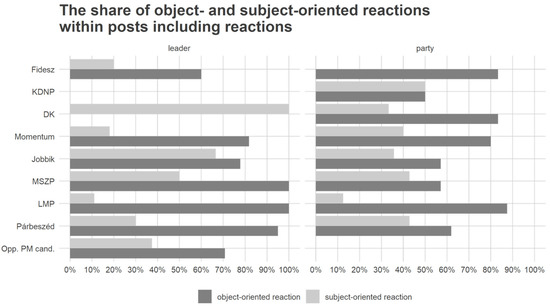

6.2. What Politicians Are Reacting to?

Figure 2 distinguishes the reactions within Facebook posts, whether the party or politician react to a particular opinion or to a person expressing an opinion. The results are relevant for our third research question because if the debater reacts to the person itself instead of his or her position, he or she commits an argumentative error according to the rules of debate in the pragma-dialectics. Our research however concludes that when political actors react to statements, they predominantly criticize their substance rather than the person who made that point. This is a particularly interesting result because in politics personal attacks are a very common phenomenon, so one might assume that politicians criticize their opponents more often than their opinions in social media arguments. Tímea Szabó (Párbeszéd), Anna Donáth (Momentum), the LMP, and the DK, or Máté Kanász-Nagy (LMP), who are particularly active in the field of reactions, almost always react to the communicator’s position, and relatively rarely attack the communicator himself. Ágnes Kunhalmi (MSZP), the Momentum and the Fidesz party are less reactive actors, but they also often react to the position of the communicator, moreover Fidesz relies exclusively on reactions to the content. Criticism of the communicator is most typical of DK-leader, Ferenc Gyurcsány, whose few reactions were all this kind, so as Jobbik-leader, Péter Jakab’s. Ágnes Kunhalmi (MSZP) and the KDNP also often take a personal approach to the content of their criticisms.

Figure 2.

Proportion of reactions to a particular subject or a person in parties and party leaders Facebook posts.

Although the figure shows that politicians react less to each other’s personal positions than to each other’s positions, it is worth distinguishing this type of reaction from the ad hominem fallacy. While former is only considered in the case when a politician or the party makes an explicit reaction to a statement, ad hominem can occur when they express opinion without reacting to other statements or people to justify the actor’s own opinion. In any case, our results suggest that political actors relatively rarely react to each other on social media, but when they do, they tend to focus on statements rather than the person of who made them.

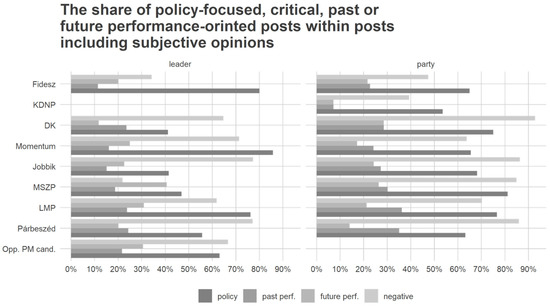

6.3. What Do Politicians Complain about?

To acquire a more nuanced understanding about the topics of the argumentation, Figure 3 shows the proportion of subjective opinions on Facebook that contained public policy-related topics, evaluations of past performance or predictions for the future, and the degree to which these opinions are negative. In 66% of argumentative posts contain negative opinions. Opposition parties and leaders are significantly more negative than those of the governing party, Viktor Orbán (Fidesz), the Fidesz and the KDNP expressed negative opinions in less than 50% of their subjective posts. The governing party-related pages are more focused on policy-related topics. Anna Donáth (Momentum) and Máté Kanász-Nagy (LMP), who already post a lot of opinions, also predominantly express views on policies. According to the table, the most negative political actor in the online space is the DK, but Párbeszéd and MSZP are not far behind. It is also interesting to note that the assessment of past and future performance is less frequent on each political site. On average, political actors express their views on the past and the future performance in 23% of their subjective posts.

Figure 3.

The ratio of posts that contained an opinion on public policy, past and future performance and with negative tone.

Based on the previous two graphs, we can therefore conclude that politicians are discussing policies rather than personal issues in the online space, with a strong negative edge and negative undertone. However, expressing opinions is only one part of the presentation of positions. All arguments are made up of a conclusion and a premise, so it is also necessary to look at the arguments politicians use to support their own opinions, whether negative or positive, policy-related or personal.

6.4. Fallacies Everywhere

Table 2 examines the presence of argumentation errors in the communication of political actors. Our research question (RQ3a) asked to what extent political actors use fallacies in their argumentation online to express their views. All but the ad hominem fallacies were coded only if subjective opinions were included in the posts. However, the variable of ad hominem fallacy was adopted from a section which investigated negative campaigning, and in this case this filter was not applied. Therefore, percentages show the share of posts where any of these fallacies appeared within the total number of posts. Overall, the presence of fallacies we listed in our research are relatively low in parties’ and their leaders’ Facebook posts. The most common one is ad hominem, which appeared in 23% of all the collected posts, followed by appeals to emotions, since politicians appealed to voters with negative emotions in 10% and positive ones in 6% of their posts. These results, therefore, show that, even if personal attacks are less frequent in explicit responses, it is generally a very frequently used communication tool. Ad populum, i.e., appeals to public opinion and slippery slope arguments, appeared in 2–2% of Facebook posts published during the campaign, while faultly generalisation was used by political actors in only 0.7% of their posts. The figure shows that the opposition used a much higher number of fallacies, while the governing parties and leaders exceed the 10% mark only in one case (Fidesz uses ad hominem in 10% of its posts)-although we also know from Figure 1 that opposition pages in general express their subjective opinions more often, i.e., they have more posts with arguments.

Table 2.

The share of argumentative fallacies within the Facebook posts of Hungarian political parties and leaders.

It seems that the proportion of argumentation errors are the highest on the right wing of the opposition. The Jobbik stands out with 53% of the ad hominems, followed by the DK with 41% and Párbeszéd with 40%. Anna Donáth (Momentum) (34%) and Tímea Szabó (Párbeszéd) (33%) also frequently use of ad hominems. Jobbik (21%), Momentum (17%), DK (16%) and Párbeszéd (13%) appeal to negative emotions in their posts in more often, while Ágnes Kunhalmi (MSZP) (14%) and Tímea Szabó (Párbeszéd) (10%) also emphasize positive emotions, although the latter is still dominated by negative emotions (15%). Jobbik’s communication shows several populist traits, and it has a high number of fallacies. The right-wing government parties (Fidesz and KDNP) are frequently using populist rhetoric as well, but contrary to the literature that suggests populist actors tend to appeal to emotions and use several ad hominems (Heiss and Matthes 2020), they lack fallacies as such on Facebook. This can be explained simply by the fact that they do not argue that often than Jobbik does.

Comparing the results with the data in Figure 1, it can be seen that the amount of argumentation errors increases with the amount of opinionated communication. Parties and leaders who express more opinions use more fallacies as well on Facebook. If we compare the table of argumentation errors with Figure 2, we can see that some politicians use ad hominem in their arguments more often than they respond to individuals. This discrepancy is possible because some posts did not always contain reactions to specific opinions, but actors use the argumentative error against a person to justify their own position. The number of ad hominems is low among politicians with a relatively higher proportion of posts reacting to individuals, such as Ferenc Gyurcsány (DK), Ágnes Kunhalmi (MSZP), or Péter Jakab (Jobbik), but this can also be explained by the fact that their reactions are lower overall compared to the statements of other parties and their leaders.

6.5. Lack of Factual Reasoning

In our research question (RQ3b), we also wanted to know not only how politicians argue, but also with what evidence. The percentage points in Table 3 show the proportion of posts which make references to data, experts, legal sources, common sense or support their claims by specific cases as a source of evidence. The figure shows that politicians cite relatively few factual sources to support their arguments, but opposition figures, in general, use them more often than their governing party counterparts. The most common was the use of individual phenomenon, which was used most often by Párbeszéd (22%), Jobbik (18%) and Tímea Szabó (Párbeszéd) (17%), but also relatively often by Anna Donáth (Momentum) (12%), the DK (9%), the MSZP (10%) and Momentum (10%) compared to the others. Data were most frequently used by the MSZP (14%), Anna Donáth (Momentum) (12%), LMP (11%), Máté Kanász-Nagy (LMP) (9%) and Tímea Szabó (Párbeszéd) (8%) during an argument.

Table 3.

Share of the different sources of evidence to support factual claims within the Facebook posts of Hungarian political parties and leaders.

A comparison of Table 2 and Table 3 show that parties and their leaders use argumentative errors more often than sources to support their opinions, but sources are also used more likely by those who communicate argumentatively in the online public sphere. Although opposition parties and their leaders cite factual sources more often, they also use more case studies in their arguments.

7. Conclusions

The results of the research paint an interesting picture of how Hungarian parties and their leaders communicate on Facebook. In our first two questions at the beginning of the study, we asked whether political leaders express their subjective opinions on different issues and whether they react to the opinions of others. In the election campaign, 35% of the posts we studied contained some kind of opinion, while reactions accounted for less than 6% of the posts. Nevertheless, we can identify some characteristics of online argumentation. In terms of opinions and reactions, opposition party sites topped the list, not only being more argumentative than pro-government politicians and parties, but also in many cases outperforming their own leaders on the scale. This may also reflect a conscious communication strategy, whereby politicians try to convey their views and organize the political agenda through their party’s Facebook pages, while on their own pages they are less able to communicate argumentatively with voters. This is supported by the fact that the main political leaders, the two prime ministerial candidates, and the leaders of the two main opposition parties, Ferenc Gyurcsány, and Péter Jakab, were rather restrained in both their expression of opinion and their reactions.

Another important observation is that in the online space political actors use arguments to justify their positions, even if often incorrectly from a pragma-dialectics perspective. Indeed, according to the data, the actors with the highest percentage of opinions, are the same who use argumentative errors or evidence the most often. This means that when they express a subjective view, they still made an effort to validate it, even if the link between the conclusion and the premise is flawed or not sufficiently supported by facts. On this basis, we can speak of some kind of burden of proof that is present on Facebook, but it is not sufficient to fulfil the universal rules of rational debate ideal of pragma-dialectics. It is also possible that a politician or a party strategically uses individual instances instead of citing data or experts to support their position, as this can have a greater rhetorical impact on Facebook.

The research also shows that when parties and their leaders do express personal opinions, they are often very negative, especially in case of the opposition-related pages. Further, all parties and party leaders prefer to express their views on public policy. In addition, an interesting observation is that, while it is rare in posts that react to other actors, the most common fallacy is still the error of personal attacks known as ad hominem fallacy.

From the perspective of traditional debate models, the Facebook discourse of political elites presents a mixed picture. In general, political actors frequently communicate their subjective opinions, mainly on public policy issues with a critical edge. However, these opinions contain errors of reasoning; ad hominem arguments are the most common feature of Hungarian political discourse, and political actors tend to use individual phenomena rather than fact-based sources as evidence to justify their claims. However, other distinctive errors of argumentation are quite rare. What is a significant limitation, however, is that there is little dialogue between these subjective opinions, and political actors rarely react to each other’s statements. When they do, however, it is a substantive, content-driven, primarily critical reaction, rather than a personal attack that otherwise characterizes the discourse. It is also important to note that while there are many similarities in general patterns between political actors, there are also remarkable differences; opposition political pages generally engage in more argumentative-reactive Facebook communication, but this is also more error-filled, than pro-government pages’ communication-although the results also highlight several exceptions in this respect.

Overall, from the perspective of traditional debate models, the main flaws are the low reaction rates and too high rates of ad hominem arguments-if these areas were to change, Facebook would provide a suitable but limited arena for public debate between political elites.

Nonetheless, it seems that Facebook cannot replace traditional political debates as politicians’ communication on this platform is consisted of series of one-way monologues rather than dialogues between the political actors. As many people acquire their political information from Facebook, it means that they mostly consume these opinionated monologues without directly contrasted with counter-opinions. In this sense, social media politics may be perceived as a chain of unchallenged statements as opposed to reasoned debate between competing views which is in sharp contrast with the pluralistic conception of democracy (see Dahl 1961).

Due to our resources, the paper has obvious limitations, since it only focuses on partys’ and party leaders’ argumentation strategies and a limited number of fallacies. Moreover, the research is based on one specific country’s one specific election campaign therefore lack of generalization can be made with the results. It would be important to see that in countries where the mass media still give floor for extensive debate between political actors, what role social media plays in this process. The method however can be used in several other cases, and with further research a comparative model can be established regarding the country’s politicians’ argumentative styles. Thus, we believe our research provided a solid merit for further examination on the topic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.J. and M.B.; methodology, V.J and M.B.; software, M.B.; validation, V.J.; formal analysis, M.B.; investigation, V.J.; resources, M.B.; data curation, M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, V.J.; writing—review and editing, M.B.; visualization, M.B.; supervision, M.B; project administration, V.J.; funding acquisition, M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by the Incubator program of the Center for Social Sciences, Hungarian Academy of Sciences Centre of Excellence (project number: 03013645), and by the ÚNKP-21-5 (ÚNKP-21-5-ELTE-1094) and the ÚNKP-22-5 (ÚNKP-22-3-I-ELTE-843) New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation from the source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Opinion and Assessment [op]

Table A1.

Opinion and assessment categories.

Table A1.

Opinion and assessment categories.

| Category | Description | Code | % (of 1 Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| opinion or assessment | Here, we code whether the post includes any subjective opinion or assessment about any political actor, situation, or phenomenon. Opinions and assessments do not only neutrally describe situations, but normatively assess them arguing why it is good/effective or bad/ineffective or substantively interpret them by highlighting its causes or consequences | 0 1 | 35% |

Appendix B. Argumentation [arg]

Here we code what kind of argumentative techniques are used in the post. Several frequently used argumentative modes are listed, code those which are present in the argumentation in any way.

Table A2.

Argumentation categories.

Table A2.

Argumentation categories.

| Category | Description | Code | % (of 1 Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ad_hom | Ad hominem: The argument includes any explicit attack the professional or personal competency, credibility, rhetorical skills or appearance of any other actors | 0 1 | 23% |

| app_pos | Appeal to positive emotions: The argument explicitly refers to the positive emotions of the self or the others. | 0 1 | 6% |

| app_neg | Appeal to negative emotions: The argument explicitly refers to the negative emotions of the self or the others. | 0 1 | 10% |

| ad_pop | Ad populum: instances of attempted reinforcement of political claims by referring to the fact that something is very popular, or the will of the people. (Blassnig et al. 2019) | 0 1 | 2% |

| assoc | Guilt by association: The subject of the argumentation is evaluated by the group (s)he belongs to. The argument is true or false because it is said by someone who belongs to the certain social or political group. It is important that the subject of the argument is an individual, but he/she is presented as a member of his/her group. | 1% | |

| slip | Slippery slope: arguments that include a sequence of steps or a chain argument that rationalizes small differences. a first step in a certain direction is described as invariably involving a whole series of small steps that are not to be stopped once the first step is taken and will finally result in a very negative consequence (Blassnig et al. 2019) | 0 1 | 2% |

Appendix C. Reaction [React]

Here, we code whether the post includes any explicit reaction to something that someone said previously. We code reaction as present only if the person who is reacted to is explicitly named in the post. Reaction can agree and disagree with or neutral toward the reacted utterance. However, the reaction should include the own opinion of the reacting person about either the reacted statement or person. If the reacted statement is just cited without any own opinion, it is not coded as reaction. If more than one reaction is included we need to focus on the most dominant one.

Table A3.

Reaction categories.

Table A3.

Reaction categories.

| Category | Description | Code | % (of 1 Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| no_react | no reaction: there is no reaction in the post | 0 1 | 94% |

| pos_react | positive reaction: the reaction is an expression of agreement with the reacted opinion or person. | 0 1 | 1% |

| neg_react | negative reaction: the reaction is an expression of disagreement with the reacted opinion or person. | 0 1 | 4% |

| neu_reacti | neutral reaction: the reaction is an expression of own views about the reacted opinion or person without explicitly agreeing or disagreeing with them. | 0 1 | 1% |

Appendix D. Reaction Target [React_Targ]

Here we code the substantive target of the reaction. It is coded only if any reaction (positive, negative or neutral) has been coded as present the reaction can react to the argument or statement, but also it can react to the person who expressed it. If both are present, we code both.

Table A4.

Reaction target categories.

Table A4.

Reaction target categories.

| Category | Description | Code | % (of 1 Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| react_ob | react to the object: the reaction is about the argument or opinion what was expressed by the reacted person. (e.g., “Márki-Zay Péter téved, amikor azt mondja, hogy fegyvereket kellene küldeni Ukrajnába, hiszen ez nagy veszélybe sodorná az országot”, “Orbán Viktornak igaza van abban, hogy ilyen helyzetben a stratégiai nyugalom a legfontosabb”. | 1 0 | 2% |

| react_sub | react to the subject: the reaction is about the person the person who expressed the argument or opinion. (e.g., “Orbán Viktor azért beszél stratégiai nyugalomról, mert már a saját hazugságaiba is belebonyolódik”. “Márki-Zay Péter javaslata mutatja, hogy mennyire józan és tisztességes politikus valójában”. | 1 0 | 5% |

Appendix E. Sources of Evidence [Source]

Here we code how facts are supported by references to different types of sources. If any reference to the sources listed below are included, we code it.

Table A5.

Sources of evidence categories.

Table A5.

Sources of evidence categories.

| Category | Description | Code | % (of 1 Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ref_data | References to data/statistics: if the post refer to any numerical data or statistics, we code this item. E.g., polls, gdp, inflation, etc. | 0 1 | 6% |

| ref_exp | References to expert: if the post refer to any expert or experts–even if in a general way such as “experts argues…”-we code this item. E.g., economists, political analysists etc. | 0 1 | 1% |

| ref_inc | References to incidents: if the post refer to one or more individual events or incidents, and deduce general political assessments from it/them. To code this, it is important to include the more general lesson or implication of the individual incident. E.g., “Völner Pált korrupcióval vádolja az ügyészség, tehát a Fidesz korrupt. “A köztévé tévesen számolt be a tüntetésről, tehát a közmédia a Fidesz befolyása alatt áll”. | 0 1 | 1% |

| ref_ck | References to common knowledge: if the post refer to something that is allegedly known by “all of us” as a common knowledge. E.g., “Ahogy azt mindannyian tudjuk, Márki-Zay Péter Gyurcsány bábja”. “Köztudott, hogy a baloldal katonákat küldene Ukrajnába”. | 0 1 | 1% |

| ref_law | References to law: if the post refer to law or legal processes to argue that something is illegal or legally obligatory etc. It doesn’t need to be very specific, it is enough if there is legal reference or argument in the post. E.g., “Márki-Zay nem küldhet katonákat Ukrajnába, mert az alkotmányba ütközik”. “A Fidesz pénzköltése nem felel meg a választási törvénynek”. | 0 1 | 9% |

Appendix F. Negativity, Past and Future Performances, Policy

Table A6.

Negativity, performance and policy categories.

Table A6.

Negativity, performance and policy categories.

| Category | Description | Code | % (of 1 Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| tendency_negative | Negative statements Here, we code if a post includes negative statements, images and emotions which are of refusing, hostile, disliking or hating nature. Here, the emotions (faces, gestures) shown in the images are especially important. | 0 1 | 39% |

| past_performance | The post focuses on the past performance of a politician or a party. Dependent on the language, the use of past tense or present tense focusing on past performances can indicate that this category applies. | 0 1 | 14% |

| future_performance | The post focuses on the future performance of a politician or a party. Dependent on the language, the use of future tense or present tense focusing on future performances can indicate that this category applies. | 0 1 | 19% |

| Policy | Created variable: 24 policy topics were listed and it was coded if the post deals with them. If any of these topics were touched upon in the post, it is coded as policy-related post | 0 1 | 44% |

Note

| 1 | https://digidemo.ifkw.lmu.de/digiworld/ accessed on 18 September 2022. |

References

- Bajomi-Lázár, Péter. 2021. Hungary’s clientelistic media system. In The Routledge Companion to Political Journalism. Edited by James Morrison, Jen Birks and Mike Berry. New York: Routledge, pp. 103–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bene, Márton, and Gabriella Szabó. 2021. Discovered and Undiscovered Fields of Digital Politics: Mapping Online Political Communication and Online News Media Literature in Hungary. Intersections: East European Journal of Society and Politics 7: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bene, Márton, and Xénia Farkas. 2022. Ki mint vet, úgy arat? A 2022-es választási kampány a közösségi médiában. Századvég 2: 131–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, W. Lance, and Steven Livingston. 2018. The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication 33: 122–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blassnig, Sina, Florin Büchel, Nicole Ernst, and Sven Engesser. 2019. Populism and Informal Fallacies: An Analysis of Right-Wing Populist Rhetoric in Election Campaigns. Argumentation 33: 107–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, Robert A. 1961. Who Governs? New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eemeren, Frans H. 2010. Strategic Maneuvering in Argumentative Discourse. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Eemeren, Frans H., A. Francisca Sn Henkemans, and Rob Grootendorst. 2002. Argumentation Analysis, Evaluation, Presentation. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Eemeren, Frans H., and Rob Grootendorst. 1984. Speech Acts in Argumentative Discussions: A Theoretical Model for the Analysis of Discussions Directed towards Solving Conflicts of Opinion. Dortrecht: Foris Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Eemeren, Frans H., and Wu Peng. 2017. Contextualizing Pragma-Dialectics, Argumentation in Context. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1996. Between Facts and Norms, Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Hans. 2020. Fallacies. In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edited by Edward N. Zalta. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2020/entries/fallacies/ (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Heiss, Raffael, and Jörg Matthes. 2020. Stuck in a Nativist Spiral: Content, Selection, and Effects of Right-Wing Populists’ Communication on Facebook. Political Communication 37: 303–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiss, Raffael, Desiree Schmuck, and Jörg Matthes. 2018. What drives interaction in political actors’ Facebook posts? Profile and content predictors of user engagement and political actors’ reactions. Information, Communication & Society 22: 1497–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkemans, Snoeck, and Arnolda Francisca. 1997. Analysing Complex Argumentation: The Reconstruction of Multiple and Coordinatively Compound Argumentation in a Critical Discussion, 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Sic Sat. [Google Scholar]

- Jost, Pablo. 2022. How politicians adapt to new media logic. A longitudinal perspective on accommodation to user-engagement on Facebook. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 1–14, Online first. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körösényi, András, Gábor Illés, and Attila Gyulai. 2020. The Orbán Regime: Plebiscitary Leader Democracy in the Making. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Levasseur, David, and Kevin W. Dean. 1996. The use of evidence in presidential debates: A study of evidence levels and types from 1960 to 1988. Argumentation and Advocacy 32: 129–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, Jürgen, and Anna-Maria Renner. 2018. When a man meets a woman: Comparing the use of negativity of male candidates in single-and mixed-gender televised debates. Political Communication 35: 433–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patkós, Veronika. 2019. Szekértáborharc: Eredmények a politikai megosztottság okairól és következményeiről. Budapest: MTA TK, Napvilág Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Rinke, Eike Mark. 2016. The Impact of Sound-Bite Journalism. Journal of Communication 66: 625–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlett, István. 2018. A politikai gondolkodás története Magyarországon, 1-2-3. (1. Mi a politikai gondolkodás?. kötet). Budapest: Századvég Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Strömbäck, Jesper, and Spiro Kiousis. 2014. Strategic political communication in election campaigns. Political Communication 1: 109–15. [Google Scholar]

- Szabó, Gabriella, and Xénia Farkas. 2021. Libernyákok és O1G. Modortalanság a politikai kommunikációban. Politikatudományi Szemle 30: 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, Márton. 2003. A diszkurzív politikatudomány alapjai. Elméletek és elemzések. Budapest: L’Harmattan. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, Douglas. 1995. A Pragmatic Theory of Fallacy. Studies in Rhetoric and Communication. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, Douglas. 2008. Informal Logic: A Pragmatic Approach, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zurloni, Valentino, and Luigi Anolli. 2010. Fallacies as Argumentative Devices in Political Debates. In Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence: Vol. 7688 Multimodal Communication in Political Speech: Shaping Minds and Social Action: International Workshop, Political Speech. Berlin: Springer, pp. 245–57. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).