Abstract

(1) In a context of an unprecedented global pandemic, an analysis of the effects of political disinformation on audiences is needed. The U.S. election process culminating in the official proclamation of Joe Biden as president has led to an increase in the public’s distrust of politics and its leaders, as public opinion polls show. In this context, the change in the electorate’s attitude towards Donald Trump, throughout the legislature and especially after the elections, stands out. So, the objective of this research was to determine, through the measurement of surveys, the views of the electorate on the behavior of the Republican candidate and the possible causes that determine the loss of confidence in his speeches and comments. (2) The methodology, a comparative quantitative-qualitative approach, analyzed the responses collected by Pew Research waves 78 and 80 (2020 and 2021). Specifically, the surveys analyzed were 11,818 U.S. adults in the case of the American Trends Panel 2020 and 5360 in the case of the same panel for 2021. (3) Results showed the change of position of the electorate, especially Republicans, in the face of the policy of delegitimization of the process and Trump’s populist messages on Twitter. (4) Conclusions pointed in two directions: society has decided not to trust Trump, while at the same time showing distrust about the correct management of the electoral ballot.

1. Introduction

Post-election polls of the US presidential election (3 November 2020) state that 60% of Americans think that Biden legitimately won the election; however, the same poll also asserts that 70% of Republicans pointed out that the Democratic candidate was not legitimately elected (Balz et al. 2021). These data reflect the polarization of citizen opinions (Bennett and Pfetsch 2018) and the distrust of voters towards politicians and institutions (Waisbord 2018a). The direct consequences are related to the instability of representative democracy (Mounk 2018) and of constitutional rights in a pandemic context, which favors the increase of misinformation (Salaverría et al. 2020). In this context, the rise of fake news in social networks (Van Der Linden et al. 2020) has occurred in parallel with the primacy of extreme political populism (Román-San-Miguel et al. 2020; Kissas 2019).

The most immediate antecedents happened during the legislature of Donald Trump (Waisbord 2018a), a leader who criticizes elites and appeals to emotions (Schneiker 2020; Block and Negrine 2017), relying on Twitter as a tool for political tactics (Persyli and Tucker 2020; Roth 2018). He is also a leader who advocates negationism, as opposed to reason, appeals to emotion and defends anti-intellectualism and politically incorrect language, vindicating the simple man (Almansa Pérez 2019). In this context, the theory of the multimodal use of the network stands out (Bracciale and Martella 2017), with a key role in the development of electoral campaigns (Campos-Domínguez 2017).

The differential factor that has marked the 2020 elections has been the denunciation of fraud of the results and the lack of recognition of Biden’s triumph that Trump has maintained until his departure from the White House. We put the focus on the final phase of a political process that was dominated by the effects of platforming, polarization and conspiracies of the leader. This process stood out in the social networks, and especially on Twitter, a thread of messages, with a combination of textual marks of hate, threats, stereotypes and lies (Van-Dijk 2015) that, to say the least, have permeated citizen attitudes. The high point of rejection could be visualized with the riots of the assault on the Capitol by a sector of Republican supporters and the decision of Twitter to close Donald Trump’s account (@realDonaldTrump), sanctioning the leader’s disinformation and his discourse against institutional stability.

From this perspective, the following objectives were put forward:

- O1.

- To find out the causes of the fall in the electorate’s confidence in Donald Trump after the U.S. elections.

- O2.

- To find out, from the opinion polls, the electorate’s opinion on Donald Trump’s populist discourse based on the delegitimization of the electoral results.

- O3.

- To understand the change of attitude of the Republican electorate following the events related to the attack on the Capitol.

2. Background

2.1. Leadership and Cyber Populism’s Influence at Election Time

There are several reasons that encourage approaching the rise of populism as an alternative to the failure of savage capitalism and hyper globalization (Cox 2018). However, populism represents, above all, a communicative and discursive staging, beyond being a symptom of the political, social and economic reality of the moment. So, this research is based on the conception and meaning of populism insofar as it represents a political tendency that seeks to attract the popular classes through any propagandistic or communicative discourse or action (Bracciale and Martella 2017). As such, for this study, we opted for a definition of a populist communication style, since we started from the theory of discursive approaches already launched by Cox (2018), Bracciale and Martella (2017), Block and Negrine (2017) and, more recently, from the contributions of Pich and Newman (2020) or Schneiker (2020).

In modern democratic societies, populists, both on the left and on the right, pretend to adopt empathy with the people, whom they theoretically represent (Moffitt and Tormey 2014). However, this connection with society, with voters, can be stylistic and rhetorical (Kissas 2019) and can also be ideological, in that it focuses on the content of the messages sent with a political and/or propagandistic character. In this line, Donald Trump represents this combination of traits that define him as an influencer and macro-strategist of political marketing (Pérez-Curiel and Limón-Naharro 2019).

As Pich and Newman affirm in their study, a political leader is, therefore, a brand. because the precepts of political marketing, in fact, are based on this idea (Ahmed et al. 2017). Additionally, in brand management, everything communicates discourse, image, message and actions (Jiménez-Marín et al. 2021). The figure of the media politician, the celebrity politician (Street 2012), generates a connection with a disaffected public (Wood et al. 2016) and shows himself to be a superhero, (Block and Negrine 2017) and savior before the system. After the elections concluded, Donald Trump’s campaign remained active and an emphatic succession of messages about the delegitimization of the results proliferates on Twitter. Cyber populism, as a current linked to the use of technology and the Internet is installed behind a message of hate, threat, stereotypes and lies, with democratic consequences that can be very harmful (Gerbaudo 2018). Personalization, victimhood and spectacularization with doses of satire and ridicule of the other (Milner and Phillips 2016) have allowed him to gain supporters among Republicans while provoking strong opposition among conservatives (De las Heras Pedrosa et al. 2017). From this approach, Donald Trump has thus embodied, as a political figure, an extreme model on social, political and economic issues. Since his first electoral campaign, and until the end of his only term in office, he has shown an authoritarian style based on biased, unusual and unsubstantiated messages on race, gender, sexuality and foreign policy. He has implemented a discourse with groundbreaking, irreverent, provocative, insulting, aggressive and offensive language (Plantic et al. 2017) combined with simple, impulsive and uncivil language (Ott 2017).

Since the 2016 campaign in the USA, Donald Trump has shown a political profile that defines him as an influencer (Montoya and Vandehey 2009; Pérez Ortega 2014), a role that refers to a set of external personal perceptions that condenses the expectations, promises and experiences that a person offers before others (Vos and Van Aelst 2018). Social networks, especially Twitter, uncover a candidate with a personalized brand (Vázquez Sande 2017) that not only provokes his political adversaries but also voters, parties and media of related ideologies. This is a personalization that is considered as the main characteristic of democratic politics in the 21st century (MacAllister 2007).

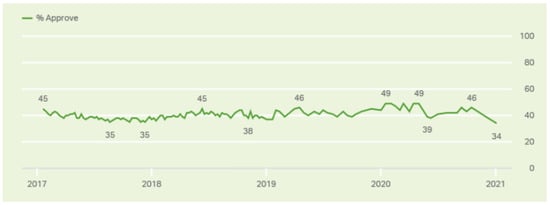

This capacity to attract citizens’ attention reached relevant heights in his second electoral appointment. However, the intensity of the conspiracy and fraud discourse against the development of the electoral process, in addition to citizen disagreements regarding the management of the pandemic or the international confrontation, may have been the cause of a division of public opinion in the post-electoral polls (Pew Research’s American Trend Panel 2020), which confirmed a change of attitude in the electorate, as well as a decrease in the support of Republicans, which were largely sympathetic to the candidate. There is an arithmetic progression of falling confidence and criticism of the leader’s management, as can be observed thanks to the data provided by Gallup Poll (2021), due to which it could be observed how Trump’s approval fell exponentially and almost constantly. It was clearly seen how this increased as populist messages harangued the masses to mobilization (Bevelander and Wodak 2019), as we can see in Figure 1. In this regard, it should be remembered that the 2020 U.S. presidential elections took place on 3 November, and the Pew Research survey was conducted between 8 and 12 January 2021, which means that 65 days passed between the two processes, a little over two months.

Figure 1.

President Donald Trump’s Job Approval Ratings, Full Trend. Source: (Gallup Poll 2021).

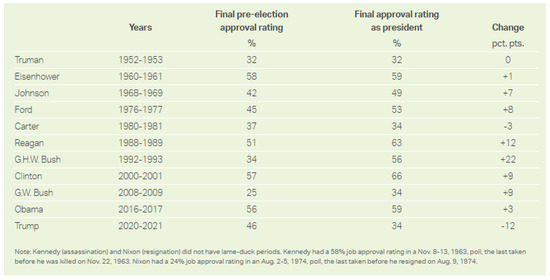

Other polls (Gallup Poll 2021) show Trump’s loss of support with respect to other American presidents in the post-election period and underline that he is the leader who leaves the White House with the most negative score of all (−12 points), a fact linked to factors such as the delegitimization of the elections, the effects of the assault on the Capitol (January 2021) or the second impeachment process (February 2021), as we can observe in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Changes in Presidential Job Approval During the Lame-Duck Period. Source: (Gallup Poll 2021).

2.2. Audience Activism against Trump’s Infodemic in Times of Crisis

The 2020 U.S. presidential elections were a focus of world interest, together with the health crisis caused by the coronavirus. Both events converged in a climate of confusion and public reaction to misinformation. At the beginning of April 2020, 113 million unique authors had shared messages on Twitter about COVID-19 (Heidi 2020). Freedom of speech allows social networks to spread any unverified misinformation and fake news (Rosenberg et al. 2020). Some messages are apocalyptic and produce a fear effect that accompanies the infectious disease (Aleixandre-Benavent et al. 2020). In this framework, Trump’s conspiracy narrative, which accuses China of causing the pandemic disease, the promotion of drugs such as hydroxychloroquine without scientific backing (Chadwick and Cereceda 2020) or his attitude of politicizing and downplaying the virus stood out. This contributed to the increase in citizen criticism of the government’s management of the pandemic. Positive opinions of support for Biden and rejection of Trump’s behavior in the face of the situation the country stood out. The Pew Research Center’s November 12-17 American Trends Panel survey found much greater agreement on the need for additional government assistance in response to the coronavirus outbreak. A large majority of Americans (80%) recognized the need for the president and Congress to approve more aid to tackle the virus in addition to the $2 billion package enacted in March. A whole chain of events that may explain the decline in support for Trump’s policies and the animosity of a growing electorate that was expressing its disagreement with Trump’s tactics and use of lies in social networks.

As a general thesis, in election periods there is an arithmetic increase in invented news (Waisbord 2018b) which in the case of Donald Trump constituted the common thread of his messages on Twitter. As in the 2016 elections, Trump stood out for his constant appeal to sentiment, xenophobic statements against minorities (Fuchs 2017), his rupturist domestic policy with the past and his grandiloquent foreign policy (Ramírez Nárdiz 2020). A dynamic of fake news propagation was reproduced and a climate of polarization (Graham et al. 2013), spectacularization (Baym 2010) and social chaos is looming. Cyber-rhetoric (López Meri 2016) is defined as a marketing strategy of the incumbent. The naturalness and spontaneity of the messages, imitating the television format, with an authentic style, more amateur than professional (Enli 2017) and unorthodox (Berger 2017), brought Trump support from his followers on Twitter. Paradoxically, Trump breaches the rules of use of this network and emphasizes a discourse of political controversy and denial of the results that proliferated until the end of his mandate.

Already throughout the 2020 campaign, a decrease in citizen support was observed in the face of a policy of disinformation, active since Trump’s beginnings as a candidate in the USA (Gallup Poll 2021). An accumulation of antecedents can explain the animosity of a part of the electorate towards the figure of the president. In the election arena, Trump’s discursive strategies regarding the production of fake news exceeds that of previous elections in 2016 (Kaiser 2020), generating a confrontation with the media that was been maintained throughout his administration. The Washington Post’s verification blog awarded him the maximum score on the dishonesty scale—four “Pinocchios”—by observing that 64% of his statements were totally false (Pérez-Curiel and Limón-Naharro 2019). Data revealed that fabricated stories favoring Donald Trump were shared 30 million times, quadrupling the number of shares in favor of Hillary Clinton (Allcott and Gentzkow 2017).

In parallel, the increasing rates of fake news on social networks had already alerted public institutions and social platforms of the potential consequences of a hyper-connected audience with a disinterest in public affairs (Lee and Xenos 2019) and ignorance of hard news (Williams and Delli-Carpini 2011). This makes it a target for misinformation (Bennett and Livingston 2018), polarization (Neudert and Marchal 2019) and political fallacies (Pérez-Curiel and Velasco Molpeceres 2020). Along these lines, international bodies (European Comission 2018) promote the creation of an independent group of experts (digital platforms and technology companies, fact-checkers, media, academics or members of civil society) in order to study possible legal ways to combat disinformation. Similarly, digital platforms such as Facebook, Google, Mozilla Firefox or Twitter have showed their commitment to contributing by designing standards of self-regulation and transparency for the 2019 European election campaign and other future elections (Tuñón Navarro et al. 2019). From this initiative derives a Twitter commitment published on its personal blog (Roth 2018), prior to the 2020 presidential elections, to warn of sanctions to users who generate the dissemination of false content.

Trump’s incisive behavior against the electoral system provoked the reaction of the institutions and the media itself. A post-election poll conducted between November 3 and 9 (El Español 2020) confirmed that 70% of Republican voters did not think the elections were free and fair. In fact, 78% of Republicans thought, according to this poll, that it was the mail-in ballot that led to massive voter fraud. In fact, 72% of Trump supporters thought those mail-in ballots were rigged, and as many as 84% thought that manipulation occurred to Joe Biden’s benefit. These percentages contrast sharply with other pre-election polls, with only 18% of Republicans showing distrust in the electoral system prior to November 3. Trump’s conspiracy theory continues its course while from the institutions and the American electoral system categorically deny that there has been any attempt to rig the result. The New York Times set out to investigate the credibility of these accusations and made a query to each of the secretaries of the 50 U.S. states. None of them pointed out any problems in their recounts or the slightest suspicion of fraud in their respective territories (Corasaniti et al. 2020).

In short, post-election polls indicate that even those who until now had been President Trump’s fan community are speaking out against the narrative of destabilization of the system that he maintains on Twitter. The confusion of public opinion noted in the first polls (Pew Research’s American Trend Panel 2020) contrasts with the response of the polls conducted after the incidents on Capitol Hill (Pew Research’s American Trend Panel 2021) and opens a debate on the participation of citizens in the fight against disinformation.

3. Materials and Methods

In the context of unprecedented political polarization in the U.S., and in the face of Trump’s and his followers’ attempts to delegitimize the outcome of the 2020 presidential election, it is necessary to analyze the evolution of public opinion from Election Day, 3 November 2020, to the certification by the Congress of Joe Biden as president-elect, on 6 January 2021.

3.1. Research Questions and Hypotheses

In this context, it is worth studying the opinion of audiences regarding the strategy of the previous president and Republican candidate, Donald Trump. In his discourse, a constant appears related to the overturn of the constitutional process of certification of the results, through lawsuits, parliamentary filibustering and a narrative based on disinformation. Considering all the above, and in accordance with the objectives of the study, the following research questions were posed:

- Q1.

- What have been the causes of the loss of confidence in Trump manifested by a part of the American electorate after the U.S. elections?

- Q2.

- What is the electorate’s opinion of Trump’s populist strategy in the post-election phase?

- Q3.

- How have Trump’s fraud speech and the incidents of the Capitol attack influenced the change of attitudes of the U.S. electorate?

Thus, we started from the main hypothesis that:

- MH.

- Populism emerges as a communicative and discursive strategy in the context of management systems based on capitalism and globalization.

From this conjectural framework, we specified the secondary hypotheses on which this study is based. So:

- SH1.

- Political populism, when perceived as such, generates rejection and distrust in the electorate.

- SH2.

- The attack on the Capitol and Donald Trump’s reaction after learning the polling data generated a change in the attitude of the Republican electorate.

3.2. Methodology

For this purpose, a quantitative-qualitative methodology based on the comparative analysis of secondary data was employed. Specifically, for this research, the responses of 11,818 respondents collected by Pew Research’s American Trend Panel (2020) were analyzed, to which we added 5360 corresponding to Pew Research’s American Trend Panel (2021).

In essence, we drew on data published by two waves of the Pew Research’s American Trends Panel (78 and 80):

- -

- Wave 78 of the American Trends Panel (Pew Research’s American Trend Panel 2020): Developed by Pew Research Center, it is an online survey panel that, through a national and random sampling, seeks to understand the attitudes of the American electorate after the 2020 presidential election. The survey was conducted on 12–17 November 2020, among 11,818 U.S. adults, including 10,399 U.S. citizens who reported voting in that election. The survey, which had a margin of sampling error of ±1.6 percentage points, was weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, political affiliation, education and other categories

- -

- Wave 80 of the American Trends Panel (Pew Research’s American Trend Panel 2021): The Pew Research Center conducted this new survey to examine the public’s reactions to the aftermath of the 2020 presidential election, including Americans’ views of Biden as president-elect, also for ratings on the Capitol Hill assault. The survey, conducted 8–12 January 2021, consults 5360 U.S. adults recruited through random sampling with weighting, as above, to ensure representativeness of the U.S. adult population based on the variables: gender, race, ethnicity, political affiliation, education and other categories. The margin of error for this survey is ±1.9 percentage points.

With all data published by the two studies, a comparative analysis of the items corresponding to the three research questions and addressed by these surveys was proposed (Table 1). Thus, the results of the study are based on the selection of data, the interpretation of the results by items and the comparison of responses related to Trump’s political management and the discourse of delegitimization of the elections. We can note this in Table 1:

Table 1.

Research questions and proposed analysis.

4. Results

In this research, then, we wanted to delve deeper into the results of this Pew report because we were interested in knowing the opinion of the audiences and comparing how the rejection of Trump’s policies had worsened. Likewise, the study serves as a precedent for others that are already being developed on the role of Twitter and the media as verifiers of information on the electoral process in the U.S., in a context of maximum disinformation also manifested in the opinion polls.

Once the elections were held, Donald Trump’s campaign remained active, especially on the social network Twitter, and disseminated a whole series of messages with which it constructed the story of electoral fraud. The successive waves of the American Trends Panel (ATP) elaborated by the think tank Pew Research Center throughout the post-electoral period showed a series of changes of opinion among the electorate and, especially, a decrease in the support of the Republican sector for its candidate, Donald Trump.

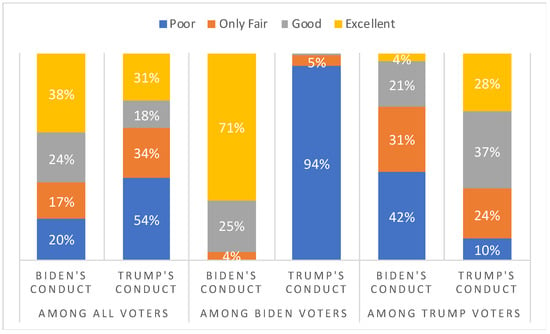

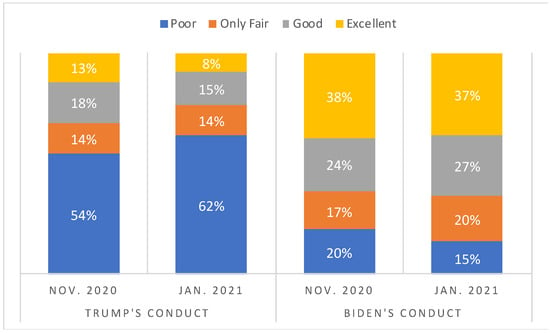

In this context, wave 78 of the ATP conducted by Pew Research Center noted a marked divide between Democratic and Republican voters (Figure 3). Although the states were several weeks away from finalizing the 2020 election results, Donald Trump was receiving very negative ratings for his conduct since Election Day. In fact, nearly seven in ten voters (68%) said the Republican front-runner’s conduct has been only fair or poor, including many voters who believe it has been bad (54%). In contrast, Joe Biden gets positive marks for his behavior since the 2020 presidential election. Overall, 62% of respondents note that it has been good or excellent, while 37% rate it as fair or poor. Still, nearly three times as many voters say Biden’s conduct is excellent, in contrast to what they say about Trump’s behavior (38% vs. 13%, respectively), as we can observe in Figure 3:

Figure 3.

Trump and Biden’s post-election conduct evaluation. Source: Own elaboration from Pew Research’s American Trend Panel (2020).

However, the high degree of polarization in this political scenario is reflected in the great divergences between Republican and Democratic voters. Thus, Trump has a third of his supporters (34%) who reject his conduct and almost all of Biden’s voters (99%) in favor of this rejection. In contrast, the attitude of the winner of the election is supported by almost all his voters (96%), but only by one in four Republican voters (25%). So far, there is still a significant degree of division between the supporters of one side or the other, which is a typical feature of electoral processes in which ideology takes precedence over other factors.

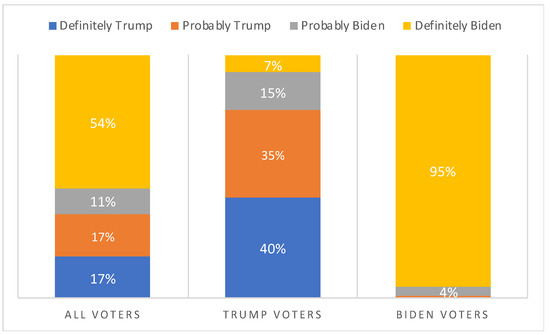

After we analyzed the elements related to the construction of the electoral fraud theory, we could highlight that while a majority of voters (59%) affirm that the presidential election in the United States is managed correctly (Figure 4), only 21% of Trump’s supporters show a positive view of how the process is developing. Thus, the discourse of conspiracy and denial of results that powers Trump in social networks became the main foreshortening of the change in the attitude of the Republicans themselves in the final phase of the process.

Figure 4.

Percentage of voters who believe that the U.S. elections have been well managed. Source: Own elaboration from Pew Research’s American Trend Panel (2020).

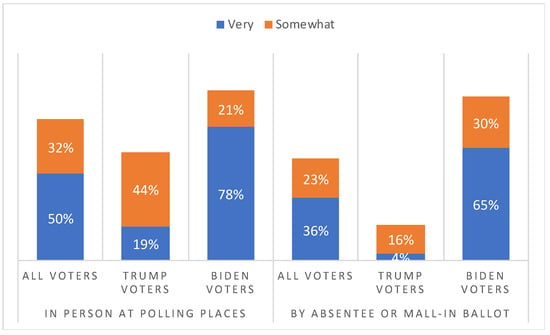

In line with the polarization and political division detected, it is noteworthy that 78% of Democratic supporters who went to the polls in person are very confident that their vote has been counted accurately (Figure 5), while in the case of Republicans it is only 19%. These divergences are even greater in the case of absentee voting, as Biden voters are overwhelmingly confident in the counting system (95%), while only one in five Trump voters are (19%). The functioning of the electoral system was the focus of the Republican leader’s attacks since the day after the elections were held, and the polls reflect the influence that this discourse has achieved among the like-minded electorate.

Figure 5.

Percentage of voters who are convinced that their vote has been counted correctly. Source: Own elaboration from Pew Research’s American Trend Panel (2020).

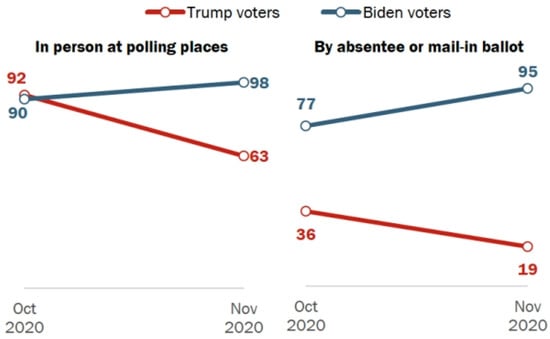

Trump’s rhetoric, on the one hand, and the media’s role as fact-checkers, on the other, make these divisions even more acute after the election. In this regard, Pew Research (Figure 6) notes that Biden voters’ confidence in a correct vote count is higher (+8%) than it was a month before Election Day. In contrast, Trump voters’ confidence in the vote count was lower (−29%) than in the pre-election survey. As the process progressed, the balance in favor of the legality of the recount strengthened, to the detriment of Trump’s delegitimization slogan against the electoral system.

Figure 6.

Evolution of trust in the correct recounting of the vote. Source: Pew Research’s American Trend Panel (2020).

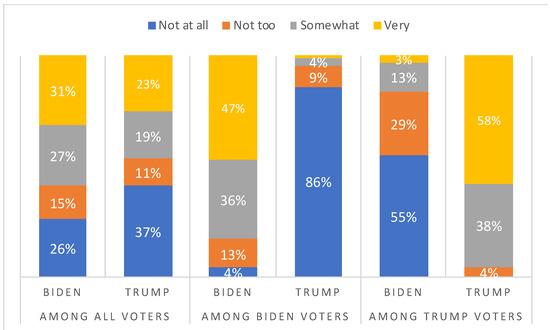

It is essential to analyze the results considering the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and its influence on public opinion. The polls show a lack of confidence in the management of the government and its president. In this context, it can be observed (Figure 7) that positive opinions of support for Biden and rejection of Trump’s behavior in the face of the crisis the country would stand out.

Figure 7.

Trust in the candidates’ ability to manage the COVID-19 health crisis. Source: Own elaboration from Pew Research’s American Trend Panel (2020).

Once again, Joe Biden and Donald Trump voters expressed greater trust in their candidate than in his opponent. However, Biden voters were especially critical of the still-president, with 86% having no confidence at all in Trump’s ability to manage the health impact of the pandemic, while Republicans who have no trust in Biden were down to 55%. In addition, 58% of Biden voters showed a lot of faith in their candidate’s ability to deal with the coronavirus, while the figure dropped to 47% for Trump voters.

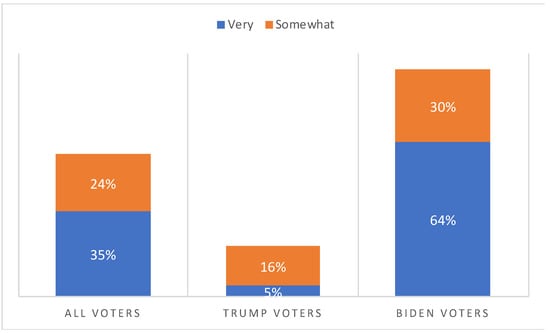

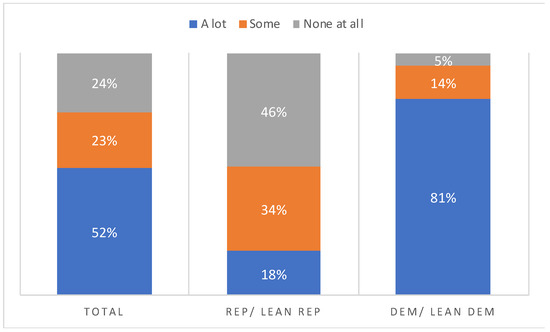

Against this survey, it is worth bearing in mind the 80th wave of the American Trends Panel, produced by Pew Research days after the incidents surrounding the assault on the Capitol (6 January 2021) by Donald Trump followers. For many, Trump’s strategy of encouraging his supporters to revolt against Joe Biden’s certification of victory and to participate in riots against Congress tarnished Trump’s final days as president. In this regard, the data indicate that three-quarters of the public believed the president bears at least some responsibility for the events and 52% said that he bears a great deal of responsibility for the unfolding of these incidents. However, nearly a quarter (24%) thought that Trump bears no responsibility for these events. In addition, it is noteworthy that about half of Republicans (52%) recognized that Trump has some responsibility for the violence unleashed in the Capitol, a figure that rose to almost all Democrats (95%). In this context, the opinions collected by the polls shows the relevance that the riots against a public institution, a symbol of representative democracy, reached for the American electorate. It is from this moment on that voters, both Trump supporters and non-Trump supporters, shared in a more evident way the reaction of rejection and disagreement with his policies. We can observe this trend in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Citizens who consider Trump bears at least part of the responsibility for the Capitol disturbances. Source: Own elaboration from Pew Research’s American Trend Panel (2021).

On the other hand, the data also show that the assessment of Joe Biden’s conduct was mostly positive, with six in 10 respondents (64%) that considered it good or very good, and even this figure rose by 2% since Election Day. In contrast, the proportion of voters who rate Trump’s conduct as negative rose from 68% in November to 76% in January. Moreover, approval among Republican voters fell to 60%, when during his entire term in office it remained between 74% and 85% (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Evolution of the evaluation of Trump’s and Biden’s behavior after the presidential election. Source: Own elaboration from Pew Research’s American Trend Panel (2021).

Despite the scenes of violence on Capitol Hill and the deterioration of Donald Trump’s image, even among his own voters, Pew Research’s American Trend Panel (Pew Research’s American Trend Panel 2021) reflects (Figure 10) that one-third (34%) of U.S. voters believed that the Republican representative won the election, a figure that rose to 75% among his constituents. In fact, it is noteworthy that only two in 10 (22%) recognized Joe Biden’s victory in the 2020 presidential election. However, the electoral delegitimization narrative lacked traction among Democratic voters (1%).

Figure 10.

Percentage of Americans who incorrectly think Trump won the election. Source: Own elaboration from Pew Research’s American Trend Panel (2021).

In short, the exploitation and comparison of data extracted from the two waves (78 and 80) of the American Trend Panel of Pew Research highlighted the process of changes in the electorate’s opinion about the narrative that Donald Trump has championed on the fraud of the elections. While it can be considered normal that the entire Democratic sector does not share this discourse of delegitimization of the results, what is exceptional is that a part of the Republicans disapproves of the management of their candidate and recognizes his responsibility in the attack on the Capitol. In any case, the levels of polarization remain in force between the two positions, although the set of responses points to a shared reaction to the disinformation.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

In modern democratic societies, populists, left or right, pretend to adopt empathy with the people, whom they theoretically represent. But this connection with society, with the voters, can be stylistic, insofar as it focuses on the form of the messages through rhetorical resources, as Kissas (2019) already pointed out, or ideological, insofar as it focuses on the content of the messages sent with a clearly propagandistic character, as Pasitselska, and Baden point out (Pasitselska and Baden 2019). A (re)negotiation of existing power relations is pursued.

Populism, in addition to being anti-elitist and anti-pluralistic, is a strategic tool for achieving political power and exercising it, which, in recent times, has found a truly valuable tool in social networks, since they provide individuals and the masses with information and resources in a fast, shocking and persuasive way, coated with a halo of truthfulness that is not always real. The increase of disinformation in social networks is evident, particularly, as has been studied in this case, on Twitter.

Data from a previous research were added that demonstrates Trump’s use, based on lies and fallacy, of Twitter as a platform to deploy his rhetoric of delegitimization of the electoral result. Taking advantage of this basis, Trump has launched, from his official account, a not inconsiderable number of messages that permeated the electorate. In previous research (Pérez-Curiel and Domínguez-García 2021) analyzing the tweets published by the US president after his defeat in the 2020 presidential election and it was shown that Trump bases his discourse on Twitter on disinformation, denouncing the alleged electoral theft (31.3%), confronting (24.8%) and defending his alleged victory (17%). In addition, the authors reflected that the Republican relies on a massive use of the propagandistic resource of fallacy (88.9%).

The rhetoric of persuasion used in this social network is based, in many political accounts, on lies and defamation. It should not be forgotten that populist political communication revolves around charismatic leaders, who launch supposed theoretical authenticities in their personality by appealing to the empathy and sympathy they are able to arouse in the people. Taking advantage of this base, Trump has launched, from his official account, a not inconsiderable number of messages that have permeated the electorate. Also, as this research has shown, beyond the specific means used for this purpose, populism is, above all, a communicative and discursive mise-en-scène, beyond being a symptom of the political, social and economic reality of the moment. This has provoked, in this specific case, an important increase in the rejection, on the part of society, towards the candidate.

In the development of Trump’s electoral period (2016–2020) and, above all, in the electoral campaign, and as a result of the COVID-19 health crisis, the high degree of polarization existing in this political scenario has been reflected in the divergences that have arisen between voters and Democrats and Republicans. Thus, consequences have been observed in two directions: at the pre-electoral level, society decided not to trust Trump with the management of the U.S.; at the post-electoral level, a large part of public opinion showed its misgivings about the correct management of the scrutiny of these elections, thus accusing the electoral system of fraud. In both cases, the perennial and progressive distrust was greater than demonstrated.

Trump, in addition, has launched many messages through Twitter in which he denied the legitimacy of the electoral process where he lost the presidency and, with this, he incited the people to rebellion so that they would stand up against the American institutions. The functioning of the electoral system has become, with this, a focus of attack, with which society was affected. In a large number of cases this led to reduced faith in the electoral system and in institutions. Thus, the conspiracy discourse and the denial of results that Trump promoted through Twitter has been the main element that has led to this change in the attitude of the Republicans themselves. Moreover, as the electoral process progressed, Trump’s delegitimization was increasing, precisely because of this public attack on the institutions and, with it, an increase in positive opinions in support of Biden.

All this leads to a reflection on the role of social networks as a means of information, and the need for fact-checking in the knowledge society, as well as a profound reasoning on the need to provide truthful and respectful messages to society and the electorate. Although they can do so, it is not the task of citizens to check every piece of information received. The media can try to alert audiences and educate them on the distinction between verified and false facts, but the public is not always capable of doing this. Along these lines, it would be interesting to propose a serious alliance between the media and social networks, as well as the signing of a code of ethics to pursue the veracity of data and the reality of information presented as facts, especially in the field of politics, as this affects all citizens.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: C.P.-C., R.D.-G. and G.J.-M.; methodology: C.P.-C., R.D.-G. and G.J.-M.; software: C.P.-C., R.D.-G. and G.J.-M.; validation: C.P.-C., R.D.-G. and G.J.-M.; formal analysis: C.P.-C., R.D.-G. and G.J.-M.; investigation: C.P.-C., R.D.-G. and G.J.-M.; resources: C.P.-C., R.D.-G. and G.J.-M.; data curation: C.P.-C., R.D.-G. and G.J.-M.; writing—original draft preparation: C.P.-C., R.D.-G. and G.J.-M.; writing—review and editing: C.P.-C., R.D.-G. and G.J.-M.; visualization: C.P.-C., R.D.-G. and G.J.-M.; supervision: C.P.-C., R.D.-G. and G.J.-M.; project administration: C.P.-C., R.D.-G. and G.J.-M.; funding acquisition: C.P.-C., R.D.-G. and G.J.-M.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmed, Mirza Ashfaq, Suleman Aziz Lodhi, and Zahoor Ahmad. 2017. Political Brand Equity Model: The Integration of Political Brands in Voter Choice. Journal of Political Marketing 16: 147–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleixandre-Benavent, Rafael, Lurdes Castelló-Cogollos, and Juan-Carlos Valderrama-Zurián. 2020. Información y comunicación durante los primeros meses de Covid-19. Infodemia, desinformación y papel de los profesionales de la información. El Profesional de la Información 29: e290408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allcott, Hunt, and Matthew Gentzkow. 2017. Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives 31: 211–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Almansa Pérez, Rosa. 2019. El populismo de extrema derecha en los Estados Unidos de la era Trump: De la democracia “sin rostro” a la reacción identitaria. Anales de la Cátedra Francisco Suárez 53: 157–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balz, Dan, Scott Clement, and Emily Guskin. 2021. Biden Wins by Approval for Handling of Transition but Persistent GOP Skepticism on Issues Will Cloud the Opening of His Presidency, Post ABC Polls Finds. The Washington Post. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/poll-biden-trump-republicans/2021/01/16/5e41c9ba-575b-11eb-a08b-f1381ef3d207_story.html (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Baym, Geoffrey. 2010. From Cronkite to Colbert: The Evolution of Broadcast News. Boulder: Paradigm. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, W. Lance, and Steven Livingston. 2018. The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication 33: 122–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, W. Lance, and Barbara Pfetsch. 2018. Rethinking political communication in a time of disrupted public spheres. Journal of Communication 68: 243–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Arthur Asa. 2017. Marketing and American Consumer Culture. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bevelander, Pieter, and Ruth Wodak. 2019. Europe at the Crossroads: Confronting Populist, Nationalist and Global Challenges. Lund: Nordic Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Block, Elena, and Ralph Negrine. 2017. The Populist Communication Style: Toward a critical framework. International Journal of Communication 11: 178–97. [Google Scholar]

- Bracciale, Roberta, and Antonio Martella. 2017. Define the populist political communication style: The case of Italian political leaders on Twitter. Information, Communication & Society 20: 1310–29. [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Domínguez, Eva. 2017. Twitter y la comunicación política. El Profesional de la Información 26: 785–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chadwick, Lauren, and Rafa Cereceda. 2020. La Cloroquina e Hidroxicloroquina Contra el Covid-19 ¿Una Esperanza? Euronews. Available online: https://es.euronews.com/2020/03/24/empiezan-los-ensayos-clinicos-con-cloroquina-contra-el-covid-19-una-esperanza (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- Corasaniti, Epstein Nick, J. Reid, and Jim Rutenberg. 2020. The Times Called Officials in Every State: No Evidence of Voter Fraud. New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/10/us/politics/voting-fraud.html (accessed on 25 February 2021).

- Cox, Michael. 2018. Understanding the Global Rise of Populism. LSE !deas. Available online: http://www.lse.ac.uk/ideas/Assets/Documents/updates/LSE-IDEAS-Understanding-Global-Rise-of-Populism.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- De las Heras Pedrosa, Carlos, Paniagua Rojano, Francisco Javier, Carmen Jambrino Maldonado, and Patricia Iglesias Sánchez. 2017. La imagen de los candidatos en las elecciones presidenciales de los Estados Unidos. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 72: 975–97. [Google Scholar]

- El Español. 2020. Trump y la teoría de la conspiración: El 70% de los votantes republicanos cree que hubo fraude electoral. Available online: https://www.elespanol.com/mundo/america/20201112/trump-teoria-conspiracion-votantes-republicanos-fraude-electoral/535197626_0.html (accessed on 7 January 2021).

- Enli, Gunn. 2017. New media and politics. Annals of the International Communication Association 41: 220–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Comission. 2018. Fake News and Disinformation Online. Flash Eurobarometer 464. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Fuchs, Christian. 2017. Donald Trump: A critical theory perspective on authoritarian capitalism. TripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique 15: 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup Poll. 2021. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/328637/last-trump-job-approval-average-record-low.aspx (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Gerbaudo, Paolo. 2018. Social media and populism: An elective affinity? Media, Culture & Society 40: 745–53. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Todd, Marcel Broersma, Karin Hazelhoff, and Guido van’t Haar. 2013. Between broadcasting political messages and interacting with voters: The use of Twitter during the 2010 UK general election campaign. Information, Communication & Society 16: 692–716. [Google Scholar]

- Heidi, Larson J. 2020. Blocking information on Covid-19 can fuel the spread of misinformation. Nature 580: 306. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Marín, Gloria, Rodrigo Elías Zambrano, Araceli Galiano-Coronil, and Luis BayardoTobar-Pesantez. 2021. Brand management from social marketing and happiness management binomial of in the age of Industry 4.0. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues 24: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, Brittany. 2020. I Blew the Whistle on Cambridge Analytica—Four Years Later, Facebook still Hasn’t Learnt Its Lesson. The Independent. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/us-election-trump-cambridge analytica-facebook-fake-news-brexit-vote-leave-a9304421.html (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- Kissas, Angelos. 2019. Performative and ideological populism: The case of charismatic leaders on Twitter. Discourse & Society 31: 268–84. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Sangwon, and Michael A. Xenos. 2019. Social distraction? Social media use and political knowledge in two US Presidential elections. Computers in Human Behavior 90: 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Meri, Amparo. 2016. Twitter-retórica para captar votos en campaña electoral. El caso de las elecciones de Cataluña de 2015. Comunicación y Hombre 12: 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacAllister, Ian. 2007. The personalization of Politics. In Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior, 1st ed. Edited by J. Dalton and Russell Hans-Dieter Kinglemann. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, M. Rayan, and Whitney Phillips. 2016. Dark Magic: The memes that made Donald Trump’s victory. In US Election Analysis 2016: Media, Voters and the Campaign, 1st ed. Edited by Darren Lilleker, Daniel Jackson, Einar Thorsen and Anastasia Veneti. Poole: Centre for the Study of Journalism, pp. 84–85. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt, Benjamin, and Simon Tormey. 2014. Rethinking populism: Politics, mediatisation, and political style. Political Studies 62: 381–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, Peter, and Tim Vandehey. 2009. The Brand Called You. Create a Personal Branding That Wins Attention and Grows Your Business. London: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Mounk, Yascha. 2018. The People vs. Democracy. Why Our Freedom Is in Danger and How to Save It. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Neudert, Lisa Maria, and Nahema Marchal. 2019. Polarisation and the Use of Technology in Political Campaigns and Communication. European Parliamentary Research—Service Scientific Foresight Unit (STOA). Available online: https://doi.org/10.2861/167110 (accessed on 6 January 2021).

- Ott, Brian L. 2017. The age of Twitter: Donald J. Trump and the politics of debasement. Critical Studies in Media Communication 34: 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasitselska, Olga, and Christian Baden. 2019. Who are ‘the people’? Uses of empty signifiers in propagandistic news discourse. Journal of Language and Politics 19: 666–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Ortega, Andrés. 2014. Marca Personal para Dummies. Barcelona: PAPF. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Curiel, Choncha, and Ricardo Domínguez-García. 2021. Discurso político contra la democracia. Populismo, sesgo y falacia de Trump tras las elecciones de EEUU (3-N). Cultura, Lenguaje y Representación 25: 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Curiel, Concha, and Pilar Limón-Naharro. 2019. Political influencers. A study of Donald Trump’s personal brand on Twitter and its impact on the media and users. Communication & Society 32: 57–75. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Curiel, Concha, and Ana María Velasco Molpeceres. 2020. Impacto del discurso político en la difusión de bulos sobre Covid-19. Influencia de la desinformación en públicos y medios. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 78: 65–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persyli, Nathaniel, and Joshua A. Tucker. 2020. Social Media and Democracy: The State of the Field, Prospects for Reform. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research’s American Trend Panel. 2020. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2020/11/20/sharp-divisions-on-vote-counts-as-biden-gets-high-marks-for-his-post-election-conduct/ (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Pew Research’s American Trend Panel. 2021. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2021/01/15/biden-begins-presidency-with-positive-ratings-trump-departs-with-lowest-ever-job-mark/ (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Pich, Christopher, and Bruce I. Newman. 2020. Evolution of Political Branding: Typologies, Diverse Settings and Future Research. Journal of Political Marketing 19: 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plantic, Diana, Hrvoje Ratkic, and Branka Suput. 2017. Comparative analysis of mar-keting communication strategy on social networks: Case study of presidential candidates Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton. Paper presented at 20th International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development, Prague, Czech Republic, April 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez Nárdiz, Alfredo. 2020. Aproximación al pensamiento político de Donald Trump: ¿es el presidente de Estados Unidos populista? Revista Española de Ciencia Política 52: 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-San-Miguel, Aránzazu, Nuria Sánchez-Gey-Valenzuela, and Rodrigo Elías Zambrano. 2020. Fake news during the COVID-19 State of Alarm. Analysis from the political point of view in the Spanish press. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 78: 359–92. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, Hans, Shahbaz Syed, and Salim Rezaie. 2020. The Twitter pandemic: The critical role of Twitter in the dissemination of medical information and misinformation during the Covid-19 pandemic. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine 22: 418–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roth, Yoel. 2018. Automation and the Use of Multiple Accounts. Twitter Developer Blog. Available online: https://blog.twitter.com/developer/en_us/topics/tips/2018/automation-and-the-use-ofmultiple-accounts.html (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Salaverría, Ramón, Nataly Buslón, Fernando López-Pan, Bienvenido León, Ignacio López-Goñi, and María-Carmen Erviti. 2020. Desinformación en tiempos de pandemia: tipología de los bulos sobre la Covid-19. El Profesional de la Información 29: e290315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneiker, Andrea. 2020. Populist Leadership: The Superhero Donald Trump as Savior in Times of Crisis. Political Studies 68: 857–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, John. 2012. Do Celebrity Politics and Celebrity Politicians Matter? The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 14: 346–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuñón Navarro, Jorge, Álvaro Oleart, and Luis Bouza García. 2019. Actores Europeos y Desinformación: La disputa entre el factchecking, las agendas alternativas y la geopolítica. Revista de Comunicación 18: 245–60. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Linden, Sander, Costas Panagopoulos, and Jon Roozenbeek. 2020. You are fake news: Political bias in perceptions of fake news. New Media & Society 42: 460–70. [Google Scholar]

- Van-Dijk, A. Teun. 2015. Critical discourse studies. A sociocognitive Approach. In Methods of Critical Discourse Studies, 3rd ed. Edited by Ruth Wodak and Michael Meyer. Los Angeles: SAGE, vol. 3, pp. 54–96. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez Sande, Pablo. 2017. Personalización de la política, narración de historias y valores transmitidos. Communication & Society 30: 275–91. [Google Scholar]

- Vos, Debby, and Peter Van Aelst. 2018. Does the Political System Determine Media Visibility of Politicians? A Comparative Analysis of Political Functions in the News in Sixteen Countries. Political Communication 35: 371–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waisbord, Silvio. 2018a. Truth is What Happens to News. Journalism Studies 19: 1866–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waisbord, Silvio. 2018b. The elective affinity between post-truth communication and populist politics. Communication Research and Practice 4: 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Bruce A., and Michel X. Delli-Carpini. 2011. After Broadcast News: Media Regimes, Democracy, and the New Information Environment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Matthew, Jack Corbett, and Matthew Flinders. 2016. Just Like Us: Everyday Celebrity Politicians and the Pursuit of Popularity in an Age of Anti-politics. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 18: 581–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).