Abstract

Background and Objectives: The increase in rates of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) due to HCV infection supported the implementation of screening programs for control of this infection in Italy. The HepCoVe network has collected cases with chronic hepatitis C (CHC) in the Veneto region of North-East Italy since the 2000s. This platform allowed us to (a) compare the characteristics of the HCV cohort exposed to parenteral risk before or after 1995 (introduction of mandatory HCV testing), and (b) track the changes induced by IFN-based therapy and the novel direct-acting antivirals (DAA). Methods: From January 2000 to December 2005, 2703 prospectively recruited cases with CHC were analyzed and followed up for 16.2 ± 8.4 years, by a per protocol analysis. Results: Two epidemic waves occurred; the first, related to blood transfusions and infection with the HCV-1b and 2a/2c genotypes, affecting an elderly population, and the second, spread through drug addiction, among young people and with a prevalence of HCV-1a, 3a/3b and 4c/4d. Patients treated with DAA had more advanced liver disease; despite this, they achieved the highest SVR rate, compared to those who received an IFN-based regimen (95.1% vs. 61.5%; p < 0.01). The 10-year HCC incidence rate by KM was 0.81, 3.75, and 1.26 per 100 person-years (p-y) in cases with or without SVR and in the untreated group, respectively (p < 0.001). Conclusions: The period of exposure to HCV in Italy (born from 1939 to 1989) was supported by two epidemic waves. Unknowing cases of HCV infection are disappearing, particularly those included in the first cohort, among the “boomers”. Despite the eradication of HCV in all treated cases, antiviral therapy does not completely eliminate the risk of HCC onset.

1. Introduction

The spread of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, particularly in the period 1945–1965, subsequently caused a high rate of related cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [1]. The high incidence of HCV has led to an estimated average prevalence of chronic infection of 0.50% in Europe (EU), reaching a peak of 0.88% in Eastern EU, therefore affecting approximately 2,820,000 people in 2019, of which approximately 570,600 were in Italy, highlighting a prevalence of 0.96% and 3.0% between northern and southern Italy, respectively [2].

Chronic hepatitis C (CHC), especially when the disease progresses to the stage of liver cirrhosis with clinical complications, becomes a serious health problem due to the high costs of patient management and related mortality, which appeared five times higher among those born between 1945 and 1965 compared to subsequent birth cohorts in the EU [3,4]. This period of high contagiousness was probably iatrogenic and facilitated by the use of non-disposable medical instruments and transfusions prior to the identification of HCV and the subsequent production of diagnostic tests, starting in 1990 [5,6].

The natural history of HCV is characterized by a slowly progressive chronic disease, lasting 20–40 years in approximately 80% of cases. Consequently, the cohort of individuals with HCV who acquired the infection before 1945 is progressively ending, mainly due to a temporal effect related to the natural exhaustion of the elderly population [7]. Furthermore, effective therapeutic interventions initially based on IFN starting in the 1990s [8], as well as the high HCV-related mortality in cases of cirrhosis, portal hypertension and HCC, have substantially contributed to the reduction in the infected population, even among younger subjects [9,10,11].

Among early studies, to extrapolate the prevalence of chronic HCV infection in our country, particularly one [12], in Northern Italy, estimated a 1.76% prevalence of chronic HCV-RNA positive infection in a cohort of 4820 individuals screened for cardiovascular risk factors. Two key findings emerged for improving HCV diagnosis and elimination strategies: (1) 46% of subjects with viremia had normal ALT levels, and 19% of them still showed moderate to severe hepatitis; (2) HCV-RNA positivity increased with age, from 0.67% to 2.4% in the 16–30 and 46–60 age groups.

These results suggest that many active infections without symptoms or known risk factors may go undetected, but that the number of infected individuals is decreasing, as the cohort of most affected ages (born 1945–1965) is disappearing [4,7].

Since 1995, growing awareness of these events has led to the introduction of numerous strategies to limit HCV transmission worldwide. These include mandatory HCV testing for all individuals with risk factors or abnormal ALT levels, as well as routine testing in specific groups such as blood donors, healthcare and public safety workers, and high-risk populations (including people who use drugs, prisoners, and sex workers) [13].

Furthermore, after the long use of the IFN-based regimen from 1995 to 2014 [14,15,16,17], which eradicated HCV in approximately 40–60% of treated subjects, the current introduction of direct-acting antivirals (DAA) has revolutionized therapy and outcomes in cases with CHC. DAA offered broader indications, including for patients with comorbidities, advanced age or liver disease, along with good safety, excellent tolerability and a shorter oral-only treatment regimen, achieving an SVR above 95% [18,19,20,21].

These public health actions aimed at the prevention and care of communicable diseases are now leading to the elimination of HCV in the world, an objective pursued by the World Health Organization (WHO), since Global Report 2017 [22,23] and implemented by all countries. All Italian regions by a national law application have joined to guarantee surveillance and control programs for HCV infection and for a free screening campaign for those born between 1969 and 1989 [24,25,26].

The HepCoVe network, an epidemiological and clinical observatory, established to prospectively collects cases with HCV infection in the Veneto Region of North-East (NE) Italy, enabled us to monitor and investigate the clinical and healthcare pathways involved in the effort for elimination of CHC in Italy.

The analysis and description of the HepCoVe cohort allowed us to (a) compare the characteristics of individuals with parenteral exposure reported before or after 1995, the year mandatory HCV testing was introduced, and (b) trace the changes brought about by antiviral therapies, from earlier IFN-based regimens to the new era of DAA, which represent highly effective treatments for CHC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Source

The HepCoVe project is a prospective and real-life collection of cases with HCV infection, recruited in 12 liver centers of the Veneto Region, which is one of the 20 political-administrative areas of Italy, with a population of 4,750,000 inhabitants. The study was developed as a regional surveillance program on “Improvement and control of chronic liver diseases related to HCV infection” and approved by the Local Ethics Committee. All patients’ data, made anonymous, were collected in a web-based platform, which included 56,000 medical checks obtained in the observation period from January 2000 to December 2024. Detailed medical history, in particular of all probable risk factors for exposure to HCV infection, laboratory results, treatment schemes used and all events, in particular the occurrence of HCC and the mortality of the cohort, were recorded. Figure S1 of the Supplementary Materials describes the study flowchart, showing the number of cases enrolled, those excluded from the study description, and the untreated and treated groups analyzed “per protocol,” which included 2703 cases, (see also Graphical Abstract).

2.2. Patients Selection and Characteristics

A cohort of 3397 cases with CHC (anti-HCV and HCV-RNA positive), were recruited in the period from January 2000 to December 2005, aged ≥18 to <75 years at enrollment, who gave their consent to the observational study. Patients were assessed at baseline to record (a) medical history, (b) staging of liver disease, (c) presence of signs of portal hypertension (PH) (e.g., gastro-esophageal (GE) varices or other venous collateral circles), and (d) virologic profile (genotyping and HCV-RNA level). Patients who enrolled were informed about their clinical condition and the opportunity to receive an antiviral treatment. During study analysis, we identified 1949 (57.4%) and 978 (28.8%) cases in the cohort who had experienced parenteral risk (i.e., post-transfusion hepatitis, drug injection, and occupational or needle exposure, such as tattooing or piercing), with a period of infection reported before or after 1995, respectively. The remaining 470 cases (13.8%) recorded an unknown risk profile.

2.3. Antiviral Treatment Schedules Used

Antiviral treatment has been proposed in particular for patients with histological and/or biochemical signs of chronic hepatitis or compensated cirrhosis (Child A) due to active HCV infection with known genotyping analysis. All cases with absolute contraindication to antiviral therapy—in particular, serious drug interactions, autoimmune disorders, severe depression or psychiatric diseases, HIV co-infection, cirrhosis with previous decompensation (Child B/C), GE bleeding or active HCC—were excluded. Patients with low motivation to comply or adhere to therapy (e.g., heavy drug or alcohol users) or with a life expectancy prognosis of less than 1 year due to severe comorbidity were also excluded.

Peg-IFNα-2a was administered, at a fixed dose of 180 μg/week and Peg-IFNα-2b at a high (HD; >1 μg/kg/week) or low (LD; ≤1 μg/kg/week) dose, depending on the patient’s weight (> or ≤75 kg), both plus ribavirin (RBV), at the standard dose of 15 mg/kg/tid [27]. Subsequently, since the availability of DAA, the antiviral regimen has been based or not on regimen combinations with Sofosbuvir (SOF), according to the indications of the EASL guidelines [28]. Patients treated with Peg-IFN received a 24 or 48 week schedule depending on the HCV genotype (HCV-2/3 or HCV-1/4), while the duration of DAA therapy was initially 24 weeks, with RBV addition in cases with HCV-1 or -3 infection, but reduced to 8–12 weeks and RBV-free from 2017, with latest generation and pan-genotypic molecules. All treatment interruptions or dosage changes were monitored during the FU period, to apply a per-protocol analysis. Patients were ultimately evaluated to determine sustained virologic response (SVR), defined as an undetectable level of HCV-RNA at 24 or 12 weeks after end-of-therapy (EOT) in cases treated with the Peg-IFN or DAA regimens, respectively.

2.4. Laboratory, Instrumental and Virologic Tests

Biochemical parameters were recorded at each patient evaluation, in particular: hemoglobin (g/L), white cell and platelet count (mm3), INR ration, total bilirubin (μmol/L), ALT and GGT (U/L), total protein, albumin and gamma globulin (g/L), and alfa-fetoprotein (μg/L). Patients underwent liver biopsy at recruitment to obtain a METAVIR staging of fibrosis (F0–F4) or had liver stiffness (LS) measurement according to specific probes (M or XL; 50 Hz), ranging 1.5–75 kPa and with IQR determination over 10 series by TE (Fibroscan®, Echosens, Paris, France), from 2007. All cases with values ≥ 12 kPa were defined with cirrhosis. Genotyping analysis was performed by using the Line Probe Assay (InnoLiPA-TM HCVII, Innogenetics, Gent, Belgium). Serum HCV viral load quantification was measured by real-time PCR assay (Cobas, AmpliPrep/Cobas TaqMan HCV, Roche Diagnostics S.pA., Monza, Italy).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Mean value and standard deviation (SD) were applied to continuous variables showing a normal distribution, and the means were compared using t-test for independent samples. The differences between categorical variables were evaluated with Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s test, when appropriate. The viral load at baseline of IFN and DAA schedules were showed by box and whisker as median and mean (±SD and SE). The Bonferroni method was applied to verify differences in dose-intake in relation to the three schedules used with Peg-IFNα2a and Peg-IFNα2b-LD or α2b-HD in a post hoc analysis, comparing effectiveness according to body weight (≤ or >75 kg). Only significant parameters obtained at univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses, with p-value ≤ 0.05, were taken into consideration to identify predictors of HCC onset. In cases with and without SVR, or untreated group comparison of the Kaplan–Meier curves was performed using Log-Rank test. The analyses and graphics were performed using the statistical software Stata 9.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA) and MedCalc 20.0 (MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium).

3. Results

3.1. The Epidemiological Changes in the HepCoVe Cohort

In the analysis conducted after the end of the recruitment period in 2005, the HepCoVe cohort identified two distinct HCV epidemic waves from the analysis of the HCV genotype distribution (Table 1). The first, especially within an older population of 55–60 years old, related to blood transfusion risk in 33.2–39.1% of cases and acquired particularly through HCV-1b and 2a/2c infection before 1995. The second was widespread due to drug addiction, among young people and with a prevalence of HCV-1a, 3a/3b and 4c/4d in 32.8%, 59.6% and 48.1% of cases, respectively. Among the 1949 and 978 cases reporting a parenteral risk before or after 1995, respectively, those exposed before 1995, appeared older (55.7 ± 13.1 vs. 53.0 ± 14.1; p < 0.01) and with a higher prevalence of F3-F4 fibrosis (25.0% vs. 19.1%; p < 0.01). They also showed a markedly higher rate of post-transfusion hepatitis (28.4% vs. 2.7%; p < 0.001), while the proportion of drug users remained similar between the two groups (18.5% vs. 17.7%; p = ns).

Table 1.

Characteristics of HepCoVe cohort in relation to the risk of parenteral HCV exposure reported before or after the year 1995. In this table, also the two epidemiologic waves that overlapped during the HCV infection spread in Italy are described.

However, after 1995 the situation significantly changed; the HCV genotype cluster 1a, 3a/3b, and 4c/4d remained prevalent in 69.1% of drug users (p < 0.01) but showed a sharp reduction in cases to 3–5 times.

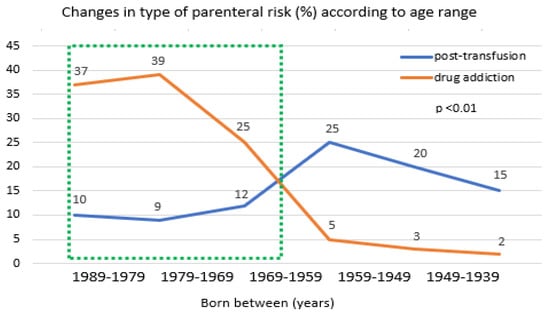

In Figure 1, the changes in cases with parenteral exposure in relation to age range helped to monitor the transition of the two waves over time. The first one had mainly exposition to post-transfusion hepatitis and was particularly concentrated in those born between 1939 and 1969. The second appeared within the youngest subjects with the highest prevalence of drug users in the period 1979–1989, showing a significant decline after 1979 (p < 0.01).

Figure 1.

Risk rates of post-transfusion hepatitis or drug addiction by age range 1939–1989, inluded in the 2005 survey data. The green dash line indicates the population included in the “2021–2025 HCV screening free-of-charge dedicated campaign in Italy”.

3.2. The Antiviral Drugs Efficacy During IFN and DAA Treatment

In Table 2, are represented the characteristics of the subjects treated with IFN or DAA regimen and the untreated group. A total of 1020 cases received a schedule with Peg-IFN plus RBV, while 940 were treated with DAA. Cases treated with IFN have prevalence of male gender, were of younger age, infected with HCV-1 in 48.8% of cases and staging advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis in 34.4% (in contrast to DAA-treated all, p < 0.01).

Table 2.

Patient’s characteristics in the groups of treated with IFN or DAA regimen and untreated cases. NS, not significant. IFN, interferon-based, BMI, body mass index; RBV, ribavirin; SVR, sustained virologic response; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; OLT, orthotopic liver transplant.

As expected, cases treated with DAA showed significantly more advanced liver disease (43,6%); despite this, they had effective therapy in 95.1% of cases reaching the SVR, compared to 61.5% of those treated with IFN (p < 0.01). Focusing on the untreated group, they showed a significantly older age (73.1 ± 10.7 years), higher rate of fibrosis stage F3-F4 (49.5%), and had the highest incidence of cases with HCC and deaths, of 15.5% and 45.6%, respectively, in contrast to treated groups (all, p < 0.01).

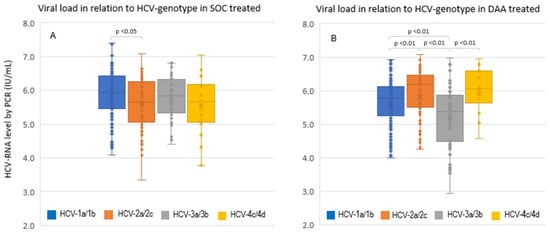

A specific analysis was also carried out to investigate levels of viremia in relation to the HCV genotype and to therapy schedules received, considering that the two types of antiviral therapy followed each other over time, and approximately one case out of three was defined as “experienced” or previously treated.

In Figure 2 is represented the viral load (IU/L) in relation to HCV genotypes at baseline. As you can see, in panel A among IFN-treated cases, only the comparison between cases with HCV-1a/1b and 2a/2c showed a statistical difference for higher viremia in the former but not with respect to those with HCV-3a/3b or 4c/4d infection (p = ns). On the contrary, in subjects treated with DAA (panel B), a more fluctuating viral load characterized the different genotype groups, with a higher viremia in HCV-2a/2c and 4c/4d, as compared to HCV-1a/1b and 3a/3b, the latter showing the lowest viremia (all, p < 0.01).

Figure 2.

Comparison of baseline viral load in relation to HCV genotype infections in all cases that received SOC with IFN-based panel (A) and with DAA treatment panel (B). SOC, standard-of-care with IFN-based treatment.

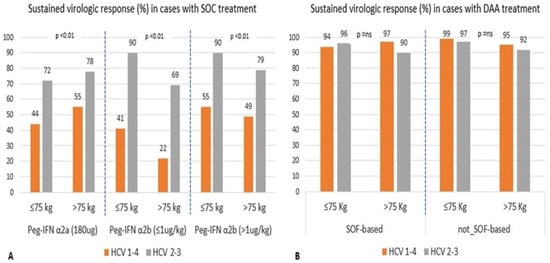

We also aimed to identify the factors associated with SVR in relation to dose and type of antiviral regimens used. In Figure 3A, during SOC treatment, body weight and HCV genotype 2 or 3 (easy to treat cases) were significantly associated with maximal SVR (90%), particularly among lighter patients (≤75 kg) treated with any Peg-IFN α2b dose (all, p < 0.01). Peg-IFN α2a fixed-dose and Peg-IFN α2b at HD produced similar SVR rate in cases with weight > 75 kg; in contrast, Peg-IFN α2b at LD proved inadequate for high-weight patients. Patients treated with DAA (panel B) achieved very high viral clearance rates among all genotypes, with a slight advantage in favor of HCV-1 or -4 infection. Thus, in the DAA era, HCV genotypes 2 and 3 appear to show greater therapeutic resistance and have become the more challenging genotypes to treat, particularly among treatment-experienced individuals.

Figure 3.

Comparison of cases with SVR treated with Peg-IFN α2a and Peg-IFN α2b at ≤1 (low dose, LD) or >1 μg/kg high dose (HD) panel (A) and Sofosbuvir-based or not-based schedules panel (B), in relation to patient body weight and genotype HCV-1-4 or HCV-2-3 infection.

3.3. The Outcome After Long-Term FU of the HepCoVe Cohort

Our latest analysis concerns the description of cohort outcomes during the FU period of 16.2 ± 8.4 years. 650 (24.0%) cases died, 82 (3.0%) received or were listed for OLT, and 250 (9.2%) developed HCC. Among the deceased, 311 cases (47.8%) received antiviral therapy, while 339 were not treated (p < 0.01). The causes of death were liver-related in 494 cases (76.0%), of which 46.4%, 35.0% and 18.6% were due to HCC, decompensated liver disease and septic episodes, respectively. In this group, male gender distribution was 57.1%, and the mean age at death among males and females was 69.1 ± 12.3 and 76.2 ± 10.1 years, respectively (p < 0.01). Mortality in cases with HCC during the long-term FU of the study was of 82.0%. Non-hepatic mortality mainly concerned cardiovascular diseases and solid tumors with an incidence of 50.6% and 30.0%, respectively.

Cases that developed HCC were 49 (4.8%), 86 (9.1%) and 115 (15.5%) among the IFN or DAA-treated and untreated groups, respectively (p < 0.01). Cases with virologic relapse after antiviral treatment had significantly higher rates of HCC occurrence, compared to those with SVR (27.3% and 0.98%; p < 0.001).

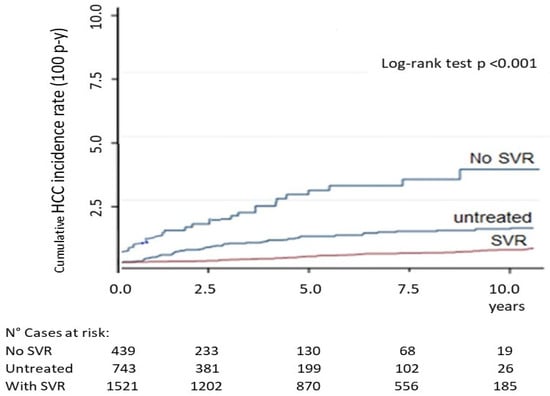

In Figure 4, the HCC cumulative incidence rate, calculated from 12 weeks EOT to 10 years of FU, described by Kaplan–Meier curves among cases with or without SVR and in the untreated group, was 0.81 (95%CI 0.41–1.97), 3.75 (95%CI 2.55–5.23) and 1.26 (95%CI 0.78–2.04) 100 p-y, respectively (Log-rank test p < 0.001). By multivariate Cox regression analysis, among patient characteristics, biochemical parameters and LS values, the variables that resulted independently associated with HCC occurrence were the following: LS (HR 2.04; 95%CI 1.4–6.6), virologic relapse after treatment (HR 7.71; 95%CI 3.2–16.8), presence of signs of PH (HR 3.81; 95%CI 1.5–9.9) and total bilirubin level (HR 1.18; 95%CI 0.8–4.9) (all, p < 0.01).

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves of cumulative HCC incidence rate, determined from 12 weeks after EOT to 10 years FU, in cases with or without SVR and in the untreated group. Four cases with relapse showed early HCC onset at inclusion. SVR, sustained virologic response; EOT, end-of-therapy.

4. Discussion

In Italy, CHC is among the main public health challenges, with a sharply decreasing prevalence trend in 2015 and 2020 at 1.4% and 1.0%, thus affecting from 888,000 to 577,000 people, respectively [29], and causing approximately 15,000–20,000 related deaths per year. Currently, the elimination of HCV infection is a major goal of all EU countries, and the WHO has set mandatory targets to eliminate HCV as a public health threat by 2030 [23].

The HepCoVe network promoted a prospective recruitment of HCV-infected cases in the Veneto region of NE Italy, collected from a web-based platform in 12 liver unit centers, and conducted with an observational long-term FU of 20 years. It was an epidemiological and clinical observatory, capable of following and exploring the sequences of clinical and healthcare pathways with the aim of eliminating hepatitis C in Italy.

Our analysis allowed us to identify different profiles based on the risk of parenteral exposure and helped to design two epidemic scenarios, overlapping in 1995 (time of mandatory HCV testing). We demonstrated that the first cohort of subjects infected before 1995 had been particularly exposed to HCV-1b or 2a/2c infection (72.8%) via post-transfusion hepatitis (90.9%) and had advanced liver disease in 25.1% of cases. In particular, this first wave included a group of females, aged 60.4 ± 12.8 years, with spread due to iatrogenic contagion from transfusions (39.1%) or use of glass syringes, mostly infected with HCV-2a/2b (68.0%) and with advanced fibrosis in 36.5% of cases.

After 1995 the profile changed, with a significant reduction in cases with post-transfusion (2.7%) or occupational risk (1.4%), and above all, with the onset of a younger male cohort aged 41.0 ± 9.1 years, especially exposed to drug addiction with HCV-1a, 3a/3b or 4c/4d infection. These subjects showed a mild fibrosis stage in more than 80% of cases, and they represented the characteristics of the subjects included in the second wave of HCV infection spread in Italy.

Our data appeared in agreement with those of a probabilistic modeling approach, to estimate annual historical HCV incident cases by age-group distribution and stage of liver disease related to HCV infection from the available literature and Italian National database [30]. The model estimated a total of 410,775 cases with active HCV infection in Italy by October 2019 (0.68% of current population; 95%CI: 0.64–0.71), of which 281,809 (68.6%) had a fibrosis stage of F0-F3, and 80% were within an age range of 46–55 years.

These epidemiological aspects must be applied to guide future strategies aimed to reach the total elimination of HCV infection, considering that the older cohort has already disappeared in Italy, and we are currently treating mostly cases with a milder stage of fibrosis in a younger population.

Since 2015, according to data from the Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA) about 277,812 patients (update on 29 September 2025) [31] with HCV infection have been treated with DAA, with a peak in 2017–2018, accounting for the highest number of DAA-treated patients in the EU [32]. It should also be considered that a significant portion of subjects (about 110,000–150,000), at least those tolerant to IFN and indicated for SOC IFN-based therapy, had already been treated in Italy, especially from 1995 to 2012. As a consequence, the active infection burden and mortality have been significantly decreased over time in Italy [29]. Particularly in the Veneto region, in the period between 2008 and 2012 among those aged ≥35 years, there was a decline of 4.0% per year in age-standardized mortality related to chronic liver disease, of which 22.8% was associated with HCV infection [33].

We analyzed 1960 cases, of which 1020 and 940 were treated with IFN and DAA regimens. As expected, the recent cohort of DAA-treated, in contrast to IFN-based, appeared nearly equal in gender distribution (51.3% male), but older (59.4 ± 10.3 vs. 50.8 ± 8.3 years), with prevalence of genotype HCV-1 (61.5% vs. 48.8%), and with a higher rate of advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis (43.6% vs. 34.4%). They also showed a maximized SVR rate at 95.1% (all, p < 0.01). Finally, the untreated group of 743 cases had a higher prevalence among people over 70 years of age, of female gender with F3-F4 fibrosis stage (49.5%) and HCV-1 infection (51.5%). These characteristics may motivate the choice to postpone IFN-based treatment, as many of them did not meet the eligibility criteria for IFN therapy and they appeared as difficult-to-treat cases.

Literature data have widely demonstrated that there is a different sensitivity of response to IFN therapy in relation to infecting genotype, with cases defined as easy to treat such as HCV-2 and -3, which have instead become the most difficult to treat during the DAA era, particularly in HCV-3-experienced patients [34]. This phenomenon was due to the multiple cycles of antivirals received in resistant cases, which certainly influenced the natural balance between HCV quasi-species, and the emergence of mutant subtypes. This fully motivates the different definition of “easy- or difficult-to-treat patient” in the periods in which IFN or DAA molecules were used.

Our data described these viral load fluctuations at baseline of antiviral treatments with IFN or DAA. There was a more preserved profile during previous IFN therapy that had 72.1% of naïve cases, in contrast to 36.2% in DAA-treated cases. During DAA, HCV levels appeared significantly decreased in cases with genotype HCV-1 and -3. Despite this, HCV-3 has represented the most difficult to treat, perhaps due also to an intrinsic and known resistance to the polymerase inhibitor present in this strain [35].

The body weight of patients certainly influenced the effectiveness of the therapy in our study, particularly in cases treated with IFN. The fixed dose with Peg-IFN α-2a showed comparable results with α-2b-HD (≥1 μg/kg), while the dose of α-2b-LD (<1 μg/kg) clearly appeared useless, especially in subjects weighing > 75 kg. During DAA treatment, HCV-3-infected cases showed the lowest response, especially related to cases with highest body weight (SVR 90–92%).

The HepCoVe cohort, including a FU of 16.2 ± 8.4 years, also helped to describe clinical outcomes, particularly related to HCV liver disease. By a per-protocol analysis in 2703 cases, the mortality and the number of patients that received an OLT or had HCC occurrence was 24%, 3% and 9.2%, respectively. Mortality involved males in two thirds of cases, with an earlier age of death in contrast to female (69.1 ± 12.3 vs. 76.2 ± 10.1 years; p < 0.01) and appeared especially HCC-related in 82.0% of cases. These data are perhaps due also to comorbidities, in particular smoking and alcohol habits, as well as cardiovascular diseases and diabetes, that were more frequent among males (p < 0.01). The HCC onset was highly related to therapy relapse, especially in the DAA era, due to a proportion of cases with progressive liver disease and PH, in this setting of cases, as known cancer-promoting factors [36]. Thus, the HCC cumulative incidence rate (100 p-y) at 10 years of FU was of 0.81, 3.75 and 1.26 among cases with or without SVR and in the untreated group, respectively, (p < 0.001).

Universal treatment with DAA of patients with chronic HCV infection has been widely conducted in Italy since 2017 [37], treating all cases regardless of the stage of liver disease. This new effective approach for the treatment of “boomers” who had not responded to SOC with IFN, from 1995 to 2014, allowed the eradication of HCV infection in the older generation born between 1939 and 1969 [7] and also influenced the epidemiologic history and clinical aspects of the HepCoVe cohort.

Nowadays, HCV infection appears significantly in resolution, with a prevalence of less than 0.5% in the Italian general population [33]. Furthermore, in Italy, a free-of-charge dedicated campaign for hepatitis C screening began in 2021, among those born in the period 1969–1989, and for the key population of drug addicts and prisoners, has been extended to the year 2025 [24,25,26]. Therefore, we believe that only strategies, based mainly on the identification and timely treatment of risk categories [38] or through a general population, but with a selected approach (i.e., during access to the emergency room, hospitalization or practitioner office) [39,40], can almost totally identify the remaining cases with unknown infection. Therefore, it is mandatory that EU countries continue to pursue efforts to eliminate HCV through screening, diagnosis and timely care treatments.

Strengths and Limitation of This Study

This collection was obtained in the real context of a single region, through an observational study on a large cohort, in which the results acquired, over a FU period of 20 years, were estimated. However, it was not possible to make a direct temporal comparison between the groups, but the real historical link between the treatment periods (IFN vs. DAA) as well as the data relating to the untreated group was underlined and discussed. These data, in fact, were obtained specifically in the same epidemiological and clinical population, applying the same inclusion/exclusion criteria and from the use of a common database. Of course, our data remain truly valid and adequate in the setting in which they were obtained and should be extrapolated with caution to other time periods or regions.

5. Conclusions

The 20-year HepCoVe cohort confirmed the presence of at least two epidemiological outbreak periods for HCV in Italy, which greatly differed for parenteral-risk exposition, age, fibrosis stage, and HCV genotype distribution. Unaware cases of HCV infection are disappearing, in particular those exposed to the risk of transfusion and included in the first epidemic wave, among the “boomers”. Antiviral therapy with IFN or DAA does not cancel out over time the HCC occurrence risk, although it eliminated HCV infection among all treated cases. A final effort is needed for the complete elimination of HCV infection in Italy and for achievement of WHO objectives for 2030, by a strategy based mainly on the rapid diagnostic detection of cases with active HCV infection and point-of-care of all at risk or into selected categories.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/livers6010007/s1, Figure S1: Flowchart of the study. * From January 2000 to December 2005; ** Per protocol analysis (mean FU 16.2 ± 8.4 years). TE, transient elastography; EOT, end-of-therapy; FU, follow-up; IFN, interferon; RBV, ribavirin; DAA, direct acting antivirals; HCC. hepatocellular carcinoma.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C. (Liliana Chemello) and L.C. (Luisa Cavalletto); Methodology, L.C. (Luisa Cavalletto), L.C. (Liliana Chemello), E.B. (Elisabetta Bernardinello), E.B. (Eleonora Bertoli), I.M., S.D.C. and M.S.; Software, L.C. (Luisa Cavalletto); Validation, L.C. (Luisa Cavalletto), L.C. (Liliana Chemello) and E.B. (Eleonora Bertoli); Formal analysis, L.C. (Luisa Cavalletto) and L.C. (Liliana Chemello); Investigation, E.B. (Elisabetta Bernardinello), E.B. (Eleonora Bertoli), I.M., S.D.C., M.S. and L.C. (Luisa Cavalletto); Resources, L.C. (Liliana Chemello); Data curation, E.B. (Eleonora Bertoli), E.B. (Elisabetta Bernardinello), L.C. (Luisa Cavalletto) and L.C. (Liliana Chemello); Writing—original draft preparation, L.C. (Liliana Chemello) and L.C. (Luisa Cavalletto); Writing—review and editing, L.C. (Liliana Chemello), L.C. (Luisa Cavalletto), E.B. (Eleonora Bertoli), E.B. (Elisabetta Bernardinello) and I.M.; Visualization, L.C. (Liliana Chemello); Supervision, L.C. (Liliana Chemello), L.C. (Luisa Cavalletto), E.B. (Eleonora Bertoli), E.B. (Elisabetta Bernardinello), I.M., S.D.C. and M.S.; Funding acquisition, L.C. (Liliana Chemello) and L.C. (Luisa Cavalletto). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The University of Padova, Italy supported this scientific research activity through dedicated funds for the development of projects of the Department of Medicine-DIMED (DOR 2024 N°00743).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was developed as a regional program of survey to “Improvement and Control of Chronic Liver Diseases Related to HCV Infection” by Decreto della Giunta Regionale del Veneto [D.G.R.V. N°4383, on day 7 December 1999] and approved by the Local Ethic Committee Azienda-Ospedale Università di Padova [Protocol N°208P and D.D.G. AOPD N°1023, on day 26 July 2000], as an independent project with a regional grant. The Veneto Region had no role in the collection, analysis and reporting of study data, or in the decision to publish the manuscript. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from all subjects recruited in this study cohort, who agreed also to the publication of data analyzed and of results obtained in a completely anonymous manner, regarding the identity of the cases included.

Data Availability Statement

All the data used for the study are stored in a database with security measures compliant with privacy legislation and can be consulted in an anonymous form, upon request to the researchers who conducted the study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Daniela Sterrantino for her support and assistance in verifying sources and collecting data from the study population.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ALT | alanine aminotransferase |

| BMI | body mass index |

| CI | confidence interval |

| CHC | chronic hepatitis C |

| DAA | direct-acting antiviral |

| EOT | end of therapy |

| EU | Europe |

| EV | esophageal varices |

| FU | follow-up |

| GE | gastro-esophageal |

| GGT | gamma-glutamyl transferase |

| HCC | hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HCV | human hepatitis C virus |

| HR | hazard ratio |

| IQR | interquartile range |

| LS | liver stiffness |

| OLT | orthotopic liver transplantation |

| NE | North-East |

| NS | not significant |

| PH | portal hypertension |

| RBV | ribavirin |

| SD | standard deviation |

| SE | standard error |

| SOC | standard of care |

| SOF | sofosbuvir |

| SVR | sustained virologic response |

| TE | transient elastography |

| TID | two-intakes per day |

| VS | versus |

References

- Fedeli, U. Increasing mortality associated with the more recent epidemic wave of hepatitis C virus infection in Northern. J. Viral Hepat. 2018, 25, 996–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomadakis, C.; Gountas, I. Prevalence of HCV infection in EU/EEA countries in 2019 using multiparameter evidence synthesis. Lancet Reg. Heath Eur. 2024, 36, 100792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly, K.N.; Xing, J. The increasing burden of mortality from viral hepatitis in the United States between 1999 and 2007. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012, 156, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.D.; Morgan, R.L. Recommendation for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among person born during 1945–1965. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2012, 61, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Choo, Q.L.; Kuo, G. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science 1989, 244, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstone, S.M.; Kapikian, A.Z. Transfusion-associated hepatitis not due to viral hepatitis type A or B. N. Engl. J. Med. 1975, 292, 767–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puoti, M.; Girardi, E. Chronic hepatitis C in Italy: The vanishing of the first consistent epidemic wave. Dig. Liver Dis. 2013, 45, 369–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoofnagle, J.H.; Mullen, K.D. Treatment of chronic non-A, non-B hepatitis with recombinant human alpha interferon. A preliminary report. N. Engl. J. Med. 1986, 315, 1575–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, K.N.; Hughes, E.M. Rising mortality associated with hepatitis c virus in the United States, 2003–2013. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, 1287–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, R.; Xing, J. Mortality among persons in care with hepatis C virus infection: The chronic hepatitis cohort study (CHeCS), 2006–2010. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 58, 1055–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriulli, A.; Stroffolini, T. Declining prevalence and increasing awareness of HCV infection in Italy: A population-based survey in five metropolitan areas. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 53, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberti, A.; Noventa, F. Prevalence of liver disease in a population of asymptomatic persons with hepatitis C virus infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 2002, 137, 961–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, K.C.; Barker, L.K. Estimated Prevalence and Awareness of Hepatitis C Virus Infection Among US Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, January 2017–March 2020. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 77, 1413–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chemello, L.; Cavalletto, L. The effect of interferon alpha and ribavirin combination therapy in naïve patients with chronic hepatitis C. J. Hepatol. 1995, 23, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Manns, M.P.; McHutchison, J.G. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: A randomised trial. Lancet 2001, 358, 958–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Liu, E. A comparison of peginterferon alpha-2a and alpha-2b for treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis C virus: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Clin. Ther. 2010, 32, 1565–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, S.C.; Muir, A.J. Safety profile of boceprevir and telaprevir in chronic hepatitis C: Real world experience from HCV-TARGET. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, J.C.; Nielsen, E.E. Direct-acting antivirals for chronic hepatitis C. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 9, CD012143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarębska-Michaluk, D.; Brzdęk, M. Best therapy for the easiest to treat hepatitis C virus genotype 1b-infected patients. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 6380–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Terrault, N. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in patients with cirrhosis. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2016, 32, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampertico, P.; Carrión, J.A. Real-world effectiveness and safety of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir for the treatment of patients with chronic HCV infection: A meta-analysis. J. Hepatol. 2020, 72, 1112–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis 2016–2021. Towards Ending Viral Hepatitis; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HIV-2016.06 (accessed on 17 May 2016).

- World Health Organization. Hepatitis C. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-c (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Ministry of Health. Italy Law n.8, art. 25-Sexies. 28 February 2020. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2025/03/18/25A01622/SG (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Kondili, L.A.; Aghemo, A. Milestones to reach Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) elimination in Italy: From free-of-charge screening. Dig. Liver Dis. 2022, 54, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stasi, C.; Milli, C. The Epidemiology of Chronic Hepatitis C: Where We Are Now. Livers 2024, 4, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craxì, A.; Pawlotsky, J.M. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatitis C virus infection. J. Hepatol. 2011, 55, 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghemo, A.; Berenguer, M. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C: Final update of the series☆. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 1170–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Polaris Observatory HCV Collaborators. Global change in hepatitis C virus prevalence and cascade of care between 2015 and 2020: A modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 396–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondili, L.A.; Andreoni, M. Estimated prevalence of undiagnosed HCV infected individuals in Italy: A mathematical model by route of transmission and fibrosis progression. Epidemics 2021, 34, 100442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco. Registri AIFA per il Monitoraggio dei Farmaci Anti-HCV. 2025. Available online: https://www.aifa.gov.it/en/aggiornamento-epatite-c (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- The Polaris Observatory Collaborators. Number of people treated for hepatitis C virus infection in 2014–2023 and applicable lessons for new HBV and HDV therapies. J. Hepatol. 2025, 83, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casotto, V.; Barbiellini Amidei, C. Mortality related to HCV and other chronic liver diseases in Veneto (Italy), 2008–2021: Changes in trends and age-period-cohort effects. Liver Int. 2024, 44, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabjan, P.; Brzdęk, M. Are There Still Difficult-to-Treat Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C in the Era of Direct-Acting Antivirals? Viruses 2022, 14, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.; Magri, A. Resistance analysis of genotype 3 hepatitis C virus indicates subtypes inherently resistant to nonstructural protein 5A inhibitors. Hepatology 2018, 69, 1861–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondili, L.A.; Quaranta, M.G. Profiling the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma after long-term HCV eradication in patients with liver cirrhosis in the PITER cohort. Dig. Liver Dis. 2023, 55, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A.D.; Pawlotsky, J.M. The removal of DAA restrictions in Europe—One step closer to eliminating HCV as a major public health threat. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 1188–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, J.V.; Safreed-Harmon, K. The Micro-Elimination Approach to Eliminating Hepatitis C: Strategic and Operational Considerations. Semin. Liver Dis. 2018, 38, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haukoos, J.; Rothman, R.E. Hepatitis C Screening in Emergency Departments the DETECT Hep C Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2025, 334, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrarese, A.; Zanaga, P. In-Hospital Screening Campaign Against Hepatitis C Could Be Effective for Identifying More Patients Who Still Need Treatment. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 61, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.