Abstract

Background: Methotrexate (MTX), a widely used therapeutic agent, is associated with hepatotoxicity. While cumulative MTX dosage has historically been linked to liver injury, recent evidence highlights the potential role of metabolic syndrome (MetS) as a key contributor. Objective: We evaluate the association between MetS and MTX-associated liver injury using vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE) and liver biopsy in patients suspected to have MTX-related liver injury. Design: This retrospective study analyzed 59 patients with chronic MTX use who underwent VCTE in hepatology clinics between 2016 and 2024. Patients with alternative causes of liver injury were excluded. MetS was defined per standard criteria as the presence of ≥3 criteria: diabetes, hypertension, BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, hypertriglyceridemia, or low HDL levels. Measurements: Liver stiffness measurement (LSM) and steatosis (CAP) were measured via VCTE, and liver biopsy data were reviewed for steatohepatitis. ANCOVA was used to assess the effect of MetS on liver disease while controlling for cumulative MTX dosage. Results: Of the 59 patients (mean age: 62 years; mean BMI: 34.3 kg/m2), 36 (61%) met the criteria for MetS. CAP values were significantly higher in patients with MetS (p < 0.001) independent of cumulative MTX dosage. Transformed LSM values also showed a significant association with MetS (p = 0.028). Logistic regression identified MetS as a significant predictor of biopsy-confirmed steatosis and steatohepatitis (p < 0.001) and higher NAFLD activity score (p = 0.002), whereas cumulative MTX dosage was not (p = 0.47). Conclusions: MetS is strongly associated with liver injury in chronic MTX users, independent of cumulative MTX dosage. These findings suggest metabolic factors as key mediators of MTX-induced hepatotoxicity. Prospective, multicenter studies are needed to confirm these findings and improve non-invasive monitoring strategies.

1. Introduction

Methotrexate (MTX), a dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor, is widely used across multiple medical specialties—including rheumatology, dermatology, and gastroenterology—for its potent anti-inflammatory effects. These effects are mediated through modulation of several signaling pathways to provide relief for a variety of diseases [1]. Despite its therapeutic benefits, MTX has long been associated with hepatotoxicity, particularly with long-term use [2]. Even among patients pre-screened for other potential causes of liver injury—such as viral hepatitis or autoimmune liver disease—MTX use has been linked to the development of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis [3].

The exact pathophysiology of MTX-related liver injury remains poorly defined but may involve mitochondrial toxicity, disruption of phospholipid metabolism, activation of the adenosine pathway, and increased fatty acid synthesis [4]. Early studies from the 1970s, particularly among psoriasis patients, suggested a dose-dependent relationship between cumulative lifetime MTX exposure and liver injury. Increased dosages were thought to be associated with a higher likelihood of liver injury [5]. However, a more recent systematic review encompassing forty-two studies found no consistent correlation between MTX cumulative dose and liver damage in the majority of analyses, suggesting that other comorbidities and environmental conditions may be involved [6].

One such comorbidity is metabolic syndrome (MetS), a systemic condition characterized by insulin resistance, abdominal obesity, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. MetS has been increasingly recognized as a driver of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis, most notably in the form of Metabolic-dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) [7].

Although liver biopsy has long been considered the gold standard for evaluating methotrexate-associated liver injury [8,9], its role has evolved considerably in recent years. Biopsy provides direct histologic assessment of steatosis, hepatocellular ballooning, inflammation, and fibrosis—features that are crucial for distinguishing methotrexate-related injury from metabolic-dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) [10,11]. However, its clinical utility is tempered by practical limitations. The procedure is invasive and carries risks of pain, bleeding, infection, and, in rare cases, severe hemorrhage or death [12,13]. Furthermore, sampling error and interobserver variability can lead to inconsistent fibrosis staging, especially when the injury pattern is heterogeneous or multifactorial [14,15].

Historically, clinicians performed routine surveillance biopsies after reaching cumulative methotrexate exposure thresholds (commonly 1.5–4 g) [5,16]. More recent data, however, suggest that cumulative dose alone poorly predicts hepatotoxicity, prompting a shift toward individualized, risk-based monitoring that incorporates comorbid factors such as obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome [6,17]. As a result, biopsy is now reserved for cases in which non-invasive assessments yield discordant or indeterminate results, or when definitive histologic characterization is required to guide management.

In contrast, vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE) offers a rapid, reproducible, and non-invasive alternative for quantifying both fibrosis and steatosis [18]. Prior studies, including Brotherton et al., have demonstrated strong concordance between elevated liver stiffness and controlled attenuation parameter values on VCTE and biopsy-proven fibrosis in methotrexate-treated patients [19]. Given its safety profile and diagnostic accuracy across multiple liver diseases, VCTE now serves as the preferred first-line modality for hepatic assessment in this study, while biopsy remains an important confirmatory tool when histologic clarification is necessary.

Histologically, drug-induced liver injury (DILI) and metabolic liver disease could be difficult to distinguish, as both can present similarly both histologically and clinically [3,7].

Given the overlap in histologic findings between MTX-induced liver injury and metabolic liver disease, it remains difficult in clinical practice to determine the predominant etiology of liver damage in these patients. Furthermore, with studies such as Azzam et al. showing no dose-dependent relationship between MTX and DILI, questions about the hepatoxicity of MTX have arisen. Specifically, the question arises of whether MetS plays a more central role in liver injury than previously appreciated. This study aims to evaluate the impact of MetS on liver injury in patients taking MTX. Specifically, we seek to determine whether the presence of MetS is associated with significantly higher liver stiffness (measured by FibroScan) and greater hepatic steatosis (identified via biopsy or controlled attenuation parameter) compared to patients without MetS. While MTX dosage has historically been implicated in liver damage, we hypothesize that MetS is a more influential contributor to hepatic injury in the modern low-dose MTX era.

2. Methods

Patients referred to our academic center hepatology clinics for evaluation of liver disease due to chronic MTX use from 2016 to 2024 were identified using ICD codes. Patients were included in this study if they had undergone FibroScan (FibroScan, Echosens, Paris, France) and/or liver biopsy following chronic MTX usage. Patients were excluded if the patient had a FibroScan already performed before initiation of MTX. We performed retrospective chart review of all included patients for baseline characteristics. Patients with known etiologies of liver injury such as autoimmune hepatitis, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C, as well as patients with documented alcohol use disorder, were excluded from the study. The institutional review board at our institution approved this study (IRB #31760) under Exempt Category 4 and was conducted under the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient charts were reviewed for baseline characteristics including sex, race, age, indication for MTX usage, biopsy results, and cumulative lifetime MTX dosage (weekly dose × number of weeks). Presence of DM, HTN, HLD, and elevated Body Mass Index (BMI) of ≥30 were gathered from the patient’s chart. VCTE results, including LSM (kPa) and CAP (dB/m), were collected for each patient. The authors also investigated charts for patient outcomes, presence of liver transplantation, development of hepatocellular carcinoma, and mortality.

Patients were classified as having metabolic syndrome if they met three or more of the following criteria: (1) history of DM or treatment for DM, (2) history of HTN or treatment for HTN, (3) elevated triglycerides or treatment for elevated triglycerides, (4) low high-density lipoproteins (HDL) or treatment for low HDL, and (5) elevated BMI [20]. Traditionally, waist circumference is used for diagnosis, but because this is not traditionally a portion of vital signs taken in clinic, BMI was used as a surrogate.

To enhance reliability, all FibroScan measurements were performed by trained operators using the M or XL probe as appropriate for patient body habitus, following a fasting period of at least three hours. Liver biopsy specimens were reviewed by board-certified hepatopathologists. Histologic grading and staging followed the NASH Clinical Research Network criteria, including assessment of steatosis, ballooning, lobular inflammation, and fibrosis.

Statistical analysis was performed on the data using SPSS version 29.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) to assess the impact of MetS on liver injury in individuals treated with MTX. Continuous variables are summarized as mean ± standard deviation, and categorical variables as counts with percentages. Normality was assessed using visual Q–Q plots in addition to Shapiro–Wilk testing to confirm distributional assumptions. Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) was run to determine the effect of MetS on LSM and CAP while accounting for the effects of the covariate, cumulative MTX dosage. To meet the assumptions of the ANCOVA test, the dependent variables, LSM and CAP, were interrogated for normality and homogeneity of variance using the Shapiro–Wilk test and Levene’s test of homogeneity, respectively. For Shapiro–Wilk, a non-significant result (>0.05) was concluded to be normally distributed, meaning the assumption was met. For Levene’s test of homogeneity, a non-significant result (>0.05) concluded that there was homogeneity in variance, meaning the assumption was met. Non-normality and heteroscedasticity were transformed with a square root transformation. For the ANCOVA results, a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

For CAP results, Levene’s test indicated there was homogeneity in variance F (1, 57) = 1.4, p = 0.25. CAP was deemed to have a normal distribution via the Shapiro–Wilk test. For LSM results, Levene’s test violated variance F (1, 57) = 5.2, p = 0.026. Thus, a square root transformation was performed to meet the assumption of homogeneous variance necessary for the statistical analysis. After the square root transformation of LSM (sqrtLSM), Levene’s test indicated homogeneity in variance F (1, 57) = 2.9, p = 0.094. The square root of LSM was deemed to be normally distributed via the Shapiro–Wilk test.

For the biopsy results, patients were separated into groups based on the presence of metabolic syndrome. Patients’ charts were investigated for the presence of steatosis. A nominal regression was conducted to determine a statistically significant difference of MetS on presence of steatosis when MTX dosage was considered. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

61 patients were identified with a history of chronic MTX usage who underwent VCTE. Two patients were excluded due to not taking the medication as prescribed and no documentation of pharmacy refills. Of the 59 patients included in the sample, 41 were female. The mean age was 62 years (±12). The mean BMI was 34.3 (±7.4). MTX was used to treat rheumatologic, dermatologic, oncologic, and gastrointestinal conditions. 34 patients were treated for rheumatologic causes. Of these rheumatologic indications, 27 were for rheumatoid arthritis, 3 were for sarcoidosis, 2 were for systemic lupus, 1 was for scleroderma, and 1 was for inclusion body myositis. 15 patients were treated for dermatologic complications. Of the dermatologic indications, 12 were for psoriasis, 2 were for atopic dermatitis, 1 was for bullous pemphigoid, and 1 was for pityriasis lichen chronica. Of the oncologic indications, 4 patients were treated for myelodysplastic syndromes and 3 patients were treated for leukemia/lymphoma. One patient was on methotrexate for the management of inflammatory bowel disease. A summary of the patient demographics and indications for MTX usage are displayed in Table 1. CAP ranged from 112 to 400 kPa with a mean of 290.0 (±65.2) dB/m. LSM ranged from 3.4 to 27.5 with a mean of 11.5 (±6.1) kPa. Values for LSM and CAP values are displayed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics. Patient demographics and indications for methotrexate usage. Means are presented as mean ± SD (95% CI). Categorical data are shown as counts by group (percent). For categorical variables, p-values were calculated using Pearson Chi-Square test. For continuous variables, p-values were calculated using two-sided t-tests. Significant, p < 0.05; Not significant, p > 0.05.

Table 2.

Mean CAP and LSM values for individuals taking MTX. Mean values for CAP and LSM for the individuals with MetS and those without MetS. Means are presented as mean ± SD (95% CI).

Among all patients, 36 (61%) met criteria for metabolic syndrome, and these individuals tended to have a higher BMI and a greater prevalence of diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension compared to those without MetS (Table 1). The average duration of methotrexate therapy was 6.8 ± 3.2 years, with a mean cumulative dose of 2.7 g, and no differences in cumulative dosing were observed between groups. Steatosis detected by CAP was moderate to severe in most MetS patients, whereas those without MetS typically demonstrated only mild hepatic fat accumulation.

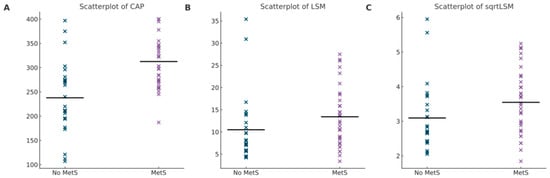

Using ANCOVA, it was determined that there was a significant effect of metabolic syndrome on CAP when cumulative MTX usage was used as a covariate F (1, 56) = 12.9, p < 0.001. Prescence of metabolic syndrome was determined to have a significant effect on sqrtLSM when cumulative MTX dosage was identified as a covariate F (1, 56) = 5.1, p = 0.028. Figure 1A shows a scatterplot of CAP for patients with metabolic syndrome and for those without. Figure 1B shows the LSM values prior to transformation and Figure 1C shows the LSM values after the square root transformation.

Figure 1.

(A) Scatterplot of CAP Values. Difference in CAP values for patients with MetS compared to those without. Mean displayed by horizontal line for each group. (B) Scatterplot of LSM values. Difference in LSM values for patients with MetS as compared to those without. Mean displayed by horizontal line for each group. (C) Scatterplot of sqrtLSM values. Difference in sqrtLSM values for patients with MetS compared to those without. Mean displayed by horizontal line for each group.

Thirty-two patients underwent liver biopsy. Of these 32 patients, 20 were identified with steatosis on biopsy. A binomial regression was performed to determine the effect of metabolic syndrome and MTX dosage on presence of steatosis. The logistic regression model was statistically significant, χ2= 13.787, p < 0.001. The model explained 40% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in steatosis on biopsy and correctly predicted 55% of cases. Presence of steatosis was significantly different in patients with metabolic syndrome (p < 0.001) but was not related to cumulative lifetime dosage of MTX (p = 0.467). Histologic review revealed that steatosis was predominantly macrovesicular, distributed mainly in the centrilobular region, and frequently accompanied by mild portal inflammation. Patients with MetS demonstrated significantly higher NAS (p = 0.002) and ballooning scores (p = 0.008) than those without MetS, consistent with the pattern of metabolic liver injury. Although no statistically significant difference was observed in fibrosis stage (p = 0.8), individuals with MetS exhibited a numerical trend toward more advanced fibrosis. Importantly, no cases of hepatic decompensation, transplantation, or mortality occurred during the study period, emphasizing the largely subclinical but progressive nature of liver injury in this population. Cumulative MTX dosage was not found to influence biopsy-proven steatosis or diagnosis of steatohepatitis (p = 0.467). A summary of the results are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Prescence of biopsy characteristics on biopsy. Data shows the number of patients who had each of the biopsy characteristics. The mean is reported as mean ± SD. A nominal regression was performed to determine if there was a difference between groups with metabolic syndrome and those without. A p < 0.05 is considered significant.

4. Discussion

MTX is a cornerstone treatment for various malignancies, autoimmune diseases, and inflammatory conditions due to its antineoplastic and immunosuppressive properties. Despite its efficacy, MTX is well-documented to cause hepatotoxicity, including serum aminotransferase elevations, fatty liver disease, fibrosis, and, in severe cases, cirrhosis or portal hypertension [16]. Historically, cumulative MTX dosage has been implicated as the primary factor in liver injury; however, variability in liver injury across patient populations suggests that additional risk factors [6], such as obesity, diabetes, and alcohol use, may contribute significantly. Modern MTX regimens with weekly dosing and folate supplementation have reduced the incidence of severe liver disease, but the mechanisms underlying liver injury, especially in the presence of metabolic risk factors, remain unclear. MASLD is associated with MetS [21] and is a prevalent cause of liver transplantation in the United States [22].

Numerous studies have established that diabetes mellitus (DM) and metabolic syndrome (MetS) are major determinants of liver disease progression. Specifically, a meta-analysis by Younossi et al. demonstrated that insulin resistance and diabetes accelerate disease evolution from steatosis to advanced fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), leading to higher liver-related and overall mortality [23]. These findings provide a mechanistic framework supporting our observation that MTX-related hepatotoxicity reflects an interaction between metabolic dysfunction and drug exposure rather than cumulative dose alone. Patients with DM and MetS exhibit a pro-inflammatory, lipotoxic hepatic environment characterized by mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and impaired autophagy [11,24,25]. Beyond these cellular mechanisms, diabetes also promotes hepatic stellate cell activation and extracellular matrix deposition through chronic hyperinsulinemia and advanced glycation end-product formation, both of which perpetuate fibrogenesis [14,15]. This study is not intended to completely disregard the cytotoxic mechanisms of MTX, as it has been well demonstrated that MTX also causes oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and disruption of nucleotide synthesis pathways contributing to hepatocellular injury [1,26]. Rather, this study attempts to address that these pathways may sensitize the liver to the toxic effects of MTX. The coexistence of MetS and MTX exposure may therefore represent a “two-hit” process in which metabolic dysregulation primes hepatocytes for injury, and MTX acts as an accelerant rather than a sole instigator. Moreover, the metabolic milieu in these patients is often compounded by dyslipidemia and visceral adiposity, which further increase hepatic oxidative stress and impair microvascular perfusion, creating a self-sustaining cycle of injury and repair. From a clinical perspective, this interaction explains why patients with diabetes or MetS frequently develop more rapid fibrosis progression even at lower cumulative MTX doses. Recognizing this relationship reframes MTX hepatotoxicity not as an inevitable consequence of long-term therapy but as a modifiable risk mediated by underlying metabolic health.

Furthermore, this study explores the relationship between MetS and MTX-associated liver injury using a retrospective cohort of chronic MTX users. Among the key findings of this study is the identification of MetS as a strong, independent predictor of fibrosis noted via LSM and steatosis measured as CAP score using VCTE, while controlling for cumulative MTX dosage. This finding challenges the traditional belief that MTX hepatotoxicity is primarily dose-dependent, highlighting instead the critical role of metabolic risk factors such as metabolic syndrome and diabetes mellitus. Our results align with broader evidence showing that DM and MetS accelerate the progression of chronic liver disease from steatosis to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and HCC [23,24,25]. This is consistent with studies demonstrating that patients with MetS or DM develop more rapid fibrosis progression, have higher rates of hepatic decompensation, and experience worse long-term survival compared to those without metabolic risk factors. In this context, MTX exposure may act as an additional insult on an already vulnerable liver, compounding the injury driven by underlying metabolic dysfunction. Importantly, this paradigm shift emphasizes that liver injury in MTX users may not be explained solely by cumulative drug exposure, but by the synergistic interplay between MTX and the metabolic milieu. Mechanistically, diabetes exacerbates hepatocellular stress through lipotoxicity, oxidative injury, and chronic inflammation, rendering the liver more susceptible to MTX-induced damage. This aligns with the concept of a “two-hit” or “multiple-hit” model of injury in metabolic dysfunction.

Clinically, these findings carry important implications for patient management. Individuals with metabolic syndrome or diabetes receiving long-term MTX should undergo more intensive hepatic monitoring—such as periodic VCTE or laboratory surveillance—given their heightened risk for fibrosis progression. Conversely, patients without metabolic risk factors may not require as frequent elastography or imaging, allowing for more judicious use of healthcare resources. This tailored approach could refine current monitoring guidelines, which historically rely primarily on cumulative MTX dose thresholds. Moreover, optimizing metabolic health through lifestyle modification or pharmacologic control of diabetes, dyslipidemia, and obesity may mitigate hepatotoxic risk and allow patients to safely continue MTX therapy, a drug that often provides disease- and life-altering benefit.

These observations underscore the need for objective, reliable measures such as VCTE and biopsy to disentangle the relative contributions of MTX and metabolic dysfunction, and to guide risk-stratified monitoring strategies. The study’s use of validated non-invasive diagnostic tools, such as VCTE, alongside histologic confirmation via liver biopsy, strengthens the reliability and clinical relevance of its results. The findings of this study align with the findings by Bedoui et al., who performed a systematic review showing that cumulative dosage of MTX does not influence degree of liver injury [1]. The hypothesis that MetS may mediate drug-induced liver injury is further supported by studies of other hepatotoxic medications such as tamoxifen, valproic acid, and lamotrigine, where metabolic risk factors modify risk [9,22].

Our results therefore support a paradigm in which MTX hepatotoxicity represents a manifestation of metabolic liver vulnerability rather than a direct toxic threshold phenomenon. Recognizing this relationship may improve clinical outcomes by prompting earlier intervention on modifiable metabolic factors, prioritizing fibrosis screening for high-risk individuals, and reducing unnecessary surveillance in low-risk populations. This risk-adapted model aligns with precision medicine principles and emphasizes prevention rather than reaction.

Robust statistical methods, including ANCOVA and logistic regression, were employed in this study to control confounders and test hypotheses effectively. Transformations to address data non-normality and heterogeneity of variance ensure the validity of the statistical analyses. The inclusion of patients treated for diverse indications (rheumatologic, dermatologic, oncologic, and gastrointestinal) enhances the general applicability of findings across specialties. We have previously described the utility of VCTE in detecting MASLD and correlated the LSM and CAP scores with steatosis and fibrosis noted on liver biopsies in these patients with chronic MTX use [20].

Strengths of this study include the integration of both non-invasive elastography and histology, adjustment for cumulative MTX dose as a covariate, and the use of real-world patients across multiple specialties. These design features enhance the clinical relevance of our findings.

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting its findings. The retrospective design introduces potential biases, including incomplete or inconsistent medical records, and the single-center nature of the study limits the generalizability of results to broader populations. Additionally, patient selection bias may have occurred since only those referred to hepatology clinics were included, potentially overrepresenting more severe disease. The overall sample size was modest, and only a subset (n = 32) underwent biopsy, which reduces statistical power and limits generalizability. The reliance on secondary data, such as medical records and pharmacy refill reports, may lead to inaccuracies in assessing MetS and cumulative MTX dosage. Variability in LSM and CAP values, particularly in the MetS group, suggests unmeasured heterogeneity, and the retrospective design precludes causal inferences. While we used established criteria to define metabolic syndrome, we acknowledge that reliance on chart documentation may have introduced some misclassification. Finally, the study’s focus on MetS and MTX dosage does not account for other potential contributors, such as lifestyle factors or genetic predispositions, and the predominance of rheumatologic indications and lack of demographic diversity further limit its applicability to other patient populations.

We acknowledge that several studies have previously examined the association between MetS and liver injury in chronic MTX users. While prior studies have explored dose-dependent MTX hepatotoxicity, recent evidence increasingly highlights the importance of metabolic risk factors [1,3,17]. Our study specifically aims to clarify the independent role of MetS in MTX-associated liver injury by employing VCTE coupled with histologic validation via liver biopsy. Additionally, we have clearly defined MetS where BMI was used instead of waist circumference due to availability and consistency of recorded clinical data. We also recognize that concurrent medications such as antidiabetic and lipid-lowering agents may have influenced outcomes, representing another potential confounder. Collectively, these findings suggest that diabetes and metabolic syndrome may act not only as coexisting comorbidities but as key modifiers of MTX-related hepatotoxicity. Recognizing this relationship has important implications for risk stratification and follow-up in patients prescribed long-term MTX.

Future directions should include the development of prospective, multicenter studies incorporating dynamic metabolic parameters (e.g., insulin resistance indices, lipid profiles, and body composition metrics) to refine risk models. Integration of fibrosis progression data and response to metabolic optimization could further delineate how improving metabolic health alters MTX tolerability and long-term outcomes.

Future research should focus on prospective, multicenter studies to validate the role of MetS in MTX-associated liver injury across diverse and larger patient populations. We plan to conduct studies with adequate follow-up to incorporate comprehensive assessments of liver-related outcomes such as cirrhosis, decompensation, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver transplantation and provide a clearer understanding of disease progression. Investigating lifestyle factors, genetic predispositions, and the interplay of other hepatotoxic medications could further elucidate the multifactorial nature of MTX-induced hepatotoxicity. Finally, developing predictive models that incorporate both metabolic and pharmacologic risk factors could guide personalized monitoring and therapeutic strategies, ensuring optimal safety and efficacy for patients on long-term MTX therapy.

In conclusion, this study suggests an association of metabolic syndrome and MTX-associated liver injury rather than the cumulative dose MTX alone in long-term MTX users. These findings aim to improve understanding of hepatotoxicity mechanisms and inform monitoring strategies, shifting focus from MTX dosage alone to metabolic health as a critical determinant of liver injury risk. Multicenter and prospective studies are required to validate the findings of this study and to avoid erroneous conclusions.

Author Contributions

K.F. contributed substantially to data acquisition, performed statistical analysis, interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. M.M. substantially contributed to the acquisition of data, critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, and assisted in data interpretation. K.Q. designed and conceived the study, supervised data acquisition, critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, provided mentorship, and approved the final version for publication. Each author has approved the final manuscript and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring accuracy and integrity. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Our study was reviewed and approved by the Saint Louis University Institutional Review Board (Protocol ID: 31760). Initial approval date: 4 May 2021. The IRB indicated that the project involves secondary analysis of fully de-identified data, therefore, no expiration date was assigned.

Informed Consent Statement

The study used de-identified data only, patient consent requirements were waived by the IRB.

Data Availability Statement

The data utilized in this study were obtained from the institutional electronic health record (EHR) system and contain protected health information (PHI). Due to privacy regulations, institutional policies, and IRB restrictions, these data cannot be publicly shared or made available outside the research institution. No additional data are available.

Conflicts of Interest

Kaila Fennell declares no conflicts of interest related to this work. Maya Mahmoud declares no conflicts of interest related to this work. Kamran Qureshi declares honoraria received from Gilead, Intercept, Salix, Madrigal, and Phathom Pharmaceuticals for speaking engagements unrelated to the submitted work.

References

- Bedoui, Y.; Guillot, X.; Sélambarom, J.; Guiraud, P.; Giry, C.; Jaffar-Bandjee, M.C.; Ralandison, S.; Gasque, P. Methotrexate an old drug with new tricks. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menter, A.; Gelfand, J.M.; Connor, C.; Armstrong, A.W.; Cordoro, K.M.; Davis, D.M.; Elewski, B.E.; Gordon, K.B.; Gottlieb, A.B.; Kaplan, D.H.; et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology–National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis with systemic nonbiologic therapies. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 82, 1445–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, B.; Chyou, P.-H.; Stratman, E.J.; Green, C. Noninvasive Testing for Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis and Hepatic Fibrosis in Patients with Psoriasis Receiving Long-term Methotrexate Sodium Therapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2017, 153, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, J.D.; Guo, G.L. Mechanistic review of drug-induced steatohepatitis. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2015, 289, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanno, R.; Gruber, G.G.; Owen, L.G.; Callen, J.P. Methotrexate in psoriasis. A brief review of indications, usage, and complications of methotrexate therapy. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1980, 2, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzam, A.; Jiyad, Z.; O’Beirne, J. Is methotrexate hepatotoxicity associated with cumulative dose? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2021, 62, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saklayen, M.G. The global epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2018, 20, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rademaker, M.; Gupta, M.; Andrews, M.; Armour, K.; Baker, C.; Foley, P.; Gebauer, K.; George, J.; Rubel, D.; Sullivan, J. The Australasian Psoriasis Collaboration view on methotrexate for psoriasis in the Australasian setting. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2017, 58, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elefsiniotis, I.S.; Pantazis, K.D.; Mariolis, A.; Moulakakis, A.; Ilias, A.; Pallis, L.; Mariolis, A.; Glynou, I.; Kada, H.; Moulakakis, A. Tamoxifen induced hepatotoxicity in breast cancer patients with liwer the role of intolerance. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2004, 16, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurice, J.; Manousou, P. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Med. 2018, 18, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, S.L.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; Rinella, M.; Sanyal, A.J. Mechanisms of NAFLD development and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 908–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, J.; Card, T.R. Reduced mortality rates following elective percutaneous liver biopsies. Gastroenterology 2010, 139, 1230–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, D.C.; Drinkwater, K.J.; Lawrence, D.; Barter, S.; Nicholson, T. Findings of the UK national audit evaluating image-guided or image-assisted liver biopsy. Part II. Minor and major complications and procedure-related mortality. Radiology 2013, 266, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Gea, V.; Friedman, S.L. Pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2011, 6, 425–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paradis, V.; Zalinski, S.; Chelbi, E.; Guedj, N.; Degos, F.; Vilgrain, V.; Bedossa, P.; Belghiti, J. Hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with metabolic syndrome often develop without significant liver fibrosis: A pathological analysis. Hepatology 2009, 49, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, M. Methotrexate and the liver. Br. J. Dermatol. 1969, 81, 465–467. [Google Scholar]

- Lertnawapan, R.; Chonprasertsuk, S.; Siramolpiwat, S.; Jatuworapruk, K. Correlation between Cumulative Methotrexate Dose, Metabolic Syndrome and Hepatic Fibrosis Detected by FibroScan in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. Medicina 2023, 59, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Castéra, L.; Vergniol, J.; Foucher, J.; Le Bail, B.; Chanteloup, E.; Haaser, M.; Darriet, M.; Couzigou, P.; de Lédinghen, V. Prospective comparison of transient elastography, Fibrotest, APRI, and liver biopsy for the assessment of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 2005, 128, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotherton, T.; Mahmoud, M.; Burton, S.; Qureshi, K. Liver Elastography for the Detection of Methotrexate-Induced Liver Injury: A Retrospective Study. Eur. Med. J. 2024, 9, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, K.G.; Eckel, R.H.; Grundy, S.M.; Zimmet, P.Z.; Cleeman, J.I.; Donato, K.A.; Fruchart, J.C.; James, W.P.; Loria, C.M.; Smith, S.C., Jr. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: A joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 2009, 120, 1640–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, R.J.; Aguilar, M.; Cheung, R.; Perumpail, R.B.; Harrison, S.A.; Younossi, Z.M.; Ahmed, A. Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Is the Second Leading Etiology of Liver Disease Among Adults Awaiting Liver Transplantation in the United States. Gastroenterology 2015, 148, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biton, V.; Mirza, W.; Montouris, G.; Vuong, A.; Hammer, A.E.; Barrett, P.S. Weight change associated with valproate and lamotrigine monotherapy in patients with epilepsy. Neurology 2001, 56, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Koenig, A.B.; Abdelatif, D.; Fazel, Y.; Henry, L.; Wymer, M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 2016, 64, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilg, H.; Moschen, A.R.; Roden, M. NAFLD and diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Sng, W.K.; Quah, J.H.M.; Liu, J.; Chong, B.Y.; Lee, H.K.; Wang, X.F.; Tan, N.C.; Chang, P.-E.; Tan, H.C.; et al. Clinical spectrum of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with diabetes mellitus. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronstein, B.N.; Aune, T.M. Methotrexate and its mechanisms of action in inflammatory arthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2020, 16, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).