Abstract

The SCALE transport lattice code, Polaris, has been previously developed to generate few-group homogenized cross sections for whole-core nodal diffusion simulators in which the embedded self-shielding method (ESSM) is used for resonance self-shielding calculations to process cross sections. Although the ESSM capability has been very successful in light-water reactor analysis, it may require enhancements in computational efficiency; treatment of spatially dependent resonance self-shielding effects; and handling of interrelated resonance effects among fuel, cladding, and control rod materials. Therefore, this study focuses on improving computational efficiency by using a Dancoff-based Wigner–Seitz approximation combined with a material-based resonance categorization, through which a spatially dependent ESSM capability is developed to accurately estimate self-shielded cross sections inside the fuel. Benchmark results show that the new capability significantly enhances computational efficiency and accuracy for spatially dependent local zones within the fuel and through depletion.

1. Introduction

SCALE/Polaris [1,2] is a two-dimensional (2D) transport lattice physics code developed to generate few-group homogenized cross sections for whole-core nodal diffusion simulators for light-water reactor (LWR) analysis. Key characteristics of the SCALE/Polaris code include (1) direct use of the SCALE/AMPX [3] multigroup (MG) library, (2) an embedded self-shielding method (ESSM) [4,5] for resonance self-shielding calculation, (3) application of the method of characteristics (MOC) for spatial discretization, and (4) coupling with the SCALE/ORIGEN application programming interface for transmutation calculations.

The Polaris ESSM capability was developed to overcome some drawbacks of the physical subgroup method [6,7], including errors arising from the least-squares fitting used to obtain subgroup data from resonance cross section tables, which are MG self-shielded cross sections expressed as a function of background cross sections. Since the subgroup method may not be applied to very thermal groups owing to poor subgroup data quality, subgroup self-shielding calculations are restricted to specified energy groups [8]. In contrast, the ESSM approach avoids errors in resonance data reconstruction and has no limitations on energy groups or nuclides. The Polaris ESSM is based on the intermediate resonance (IR) approximation [9], and its implementation builds on the subgroup implementation using MOC for fixed-source transport calculations [10]. Although the MOC-based ESSM capability in Polaris is very powerful, there remains a need for improvements in (1) computational efficiency, (2) spatially dependent self-shielding, and (3) treatment of improper resonance interference between fuel and cladding or control rod materials. This study focuses on addressing these three challenges.

Recently, the equivalent Dancoff-factor cell (EDC) model [11,12,13] for ultrafine resonance treatment and the subgroup method in a coarse group structure has gained popularity because of its excellent computational efficiency along with comparable accuracy. A key feature of the EDC method is the conversion of the whole domain into constituent cylindrical cells, with the outermost radii of the cylindrical cells adjusted to reproduce the same Dancoff factors as those obtained from the whole domain. The origin of the EDC method—specifically when and by whom it was first proposed—remains unclear. Since the release of SCALE 6.0 in 2009 [14], the SCALE code package [1] has employed the EDC method, also referred to as the Dancoff-based Wigner–Seitz approximation, by adjusting the outermost radii of single or multiple pin cells using Dancoff factors calculated with the SCALE/MCDancoff module. The conventional ESSM has since been enhanced with the Dancoff-based Wigner–Seitz approximation to improve computational efficiency.

Stoker and Weiss developed a method for spatially dependent resonance cross sections in a fuel rod, ref [15], which was later reformulated by Matsumoto et al. through a generalization of the conventional Dancoff method and the Stoker–Weiss method [16]. These methods proved successful in estimating spatially dependent self-shielded cross sections. However, they cannot be applied to nonuniform temperature distributions within a fuel rod, as noted in the cited literature. Kim et al. [17] improved spatially dependent resonance self-shielding methods to account for nonuniform temperature distributions and attempted to couple them with the ESSM procedure. In this study, Kim’s spatially dependent ESSM is further improved and integrated with the Dancoff-based Wigner–Seitz approximation to more accurately predict local self-shielded cross sections inside the fuel.

Since the original ESSM sequence in Polaris was implemented with an excessive treatment of resonance interference between fuel and cladding or control rods, special resonance cross section tables are required for resonance nuclides such as 91Zr and 96Zr in the cladding and control rods. These special resonance cross section tables for 91Zr and 96Zr should not be applied to materials other than cladding. The 235U and 238U resonance cross section tables are similar; however, error cancellations occur between resonance interference and the intrinsic reactivity bias introduced by energy group collapsing. To address this issue, the ESSM implementation was improved to estimate background cross sections on a material-specific basis. For example, separate ESSM fixed-source calculations are performed for fuel and cladding. In the present study, the material categorization capability has been completed by combining spatially dependent ESSM with the Dancoff-based Wigner–Seitz approximation and improvement in resonance data. Test ENDF/B-VII.1 AMPX 56- and 252-group libraries were developed for this material categorization capability, incorporating super-homogenization (SPH) factors to compensate for reaction rate biases introduced by energy group collapsing.

2. Methods

2.1. Embedded Self-Shielding Method

The time-independent Boltzmann neutron transport equation assuming isotropic scattering, no upscattering, and no external source is

where

= neutron direction;

= lethargy at neutron energy (=ln(E0/E));

= angular flux at zone k;

= scalar flux at zone k;

= macroscopic total (scattering, absorption) cross section for nuclide i.

In Equation (1),

where denotes the microscopic cross section for reaction x, and N and A are the atomic number density and the atomic mass number, respectively.

Equation (1) is further simplified through application of the IR approximation [8] into an MG form and can be rewritten as

where is an IR parameter at group g and Σi,p denotes the potential cross section. Equation (3) is called the fixed-source ESSM transport equation, and it can be solved with the same transport solver that is used for the eigenvalue calculation.

The background cross section () is not a fully physical quantity but rather a heuristic parameter used to retrieve the correct self-shielded cross section for a given composition and geometry. The key requirement is consistency among the procedures used for self-shielded cross section generation and application. In a heterogeneous system, the self-shielded scalar flux can be obtained by solving Equation (3) with a self-shielded absorption cross section obtained using either a deterministic or Monte Carlo solution of Equation (1). The corresponding background cross section for the resonance nuclide R can then be determined as follows:

Once the background cross section for each nuclide is determined, then effective self-shielded cross sections can be read from the resonance cross section table. However, in solving Equation (3) to obtain the background cross section within a transport code, the absorption cross sections are initially unknown. Therefore, the background cross sections and self-shielded absorption cross sections must be determined iteratively.

2.2. Limitation of the Embedded Self-Shielding Method

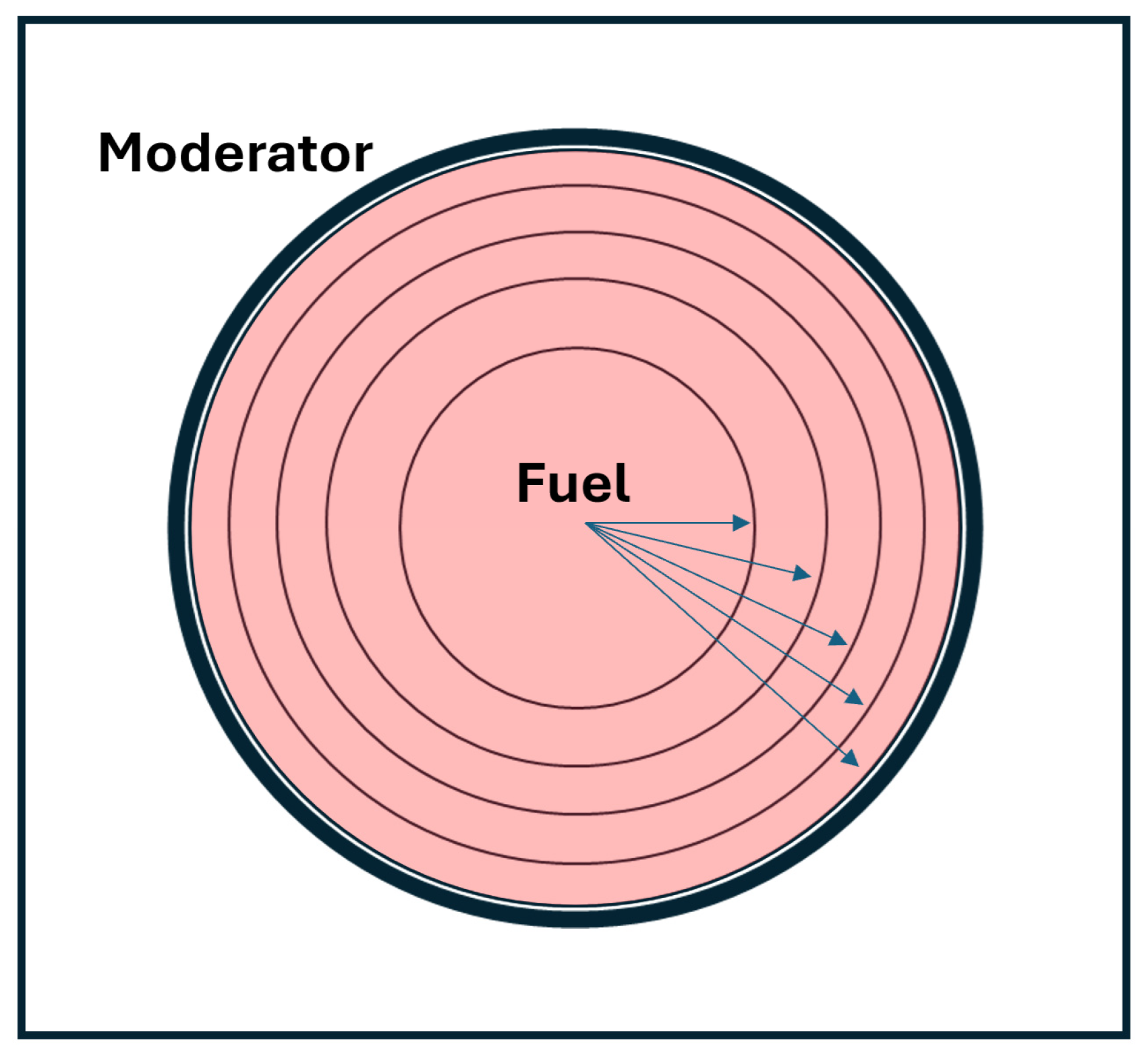

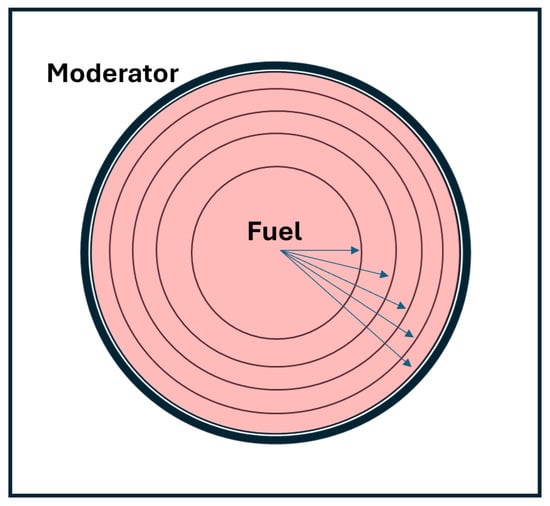

Conventional ESSM [5] has a limitation in predicting spatial variations in resonance self-shielded cross sections within a fuel region: it does not explicitly calculate spatially dependent equivalence cross sections. As a result, conventional ESSM provides accurate pin-averaged quantities of interest, but intra-pin quantities of interest—which are important for fuel performance modeling—may be inaccurate. Figure 1 and Table 1 illustrate a typical pressurized water reactor (PWR) pin configuration with five equivalent-volume radial rings within the fuel.

Figure 1.

Single-pin configuration with five radial rings.

Table 1.

Geometry and composition specifications for single-pin configuration.

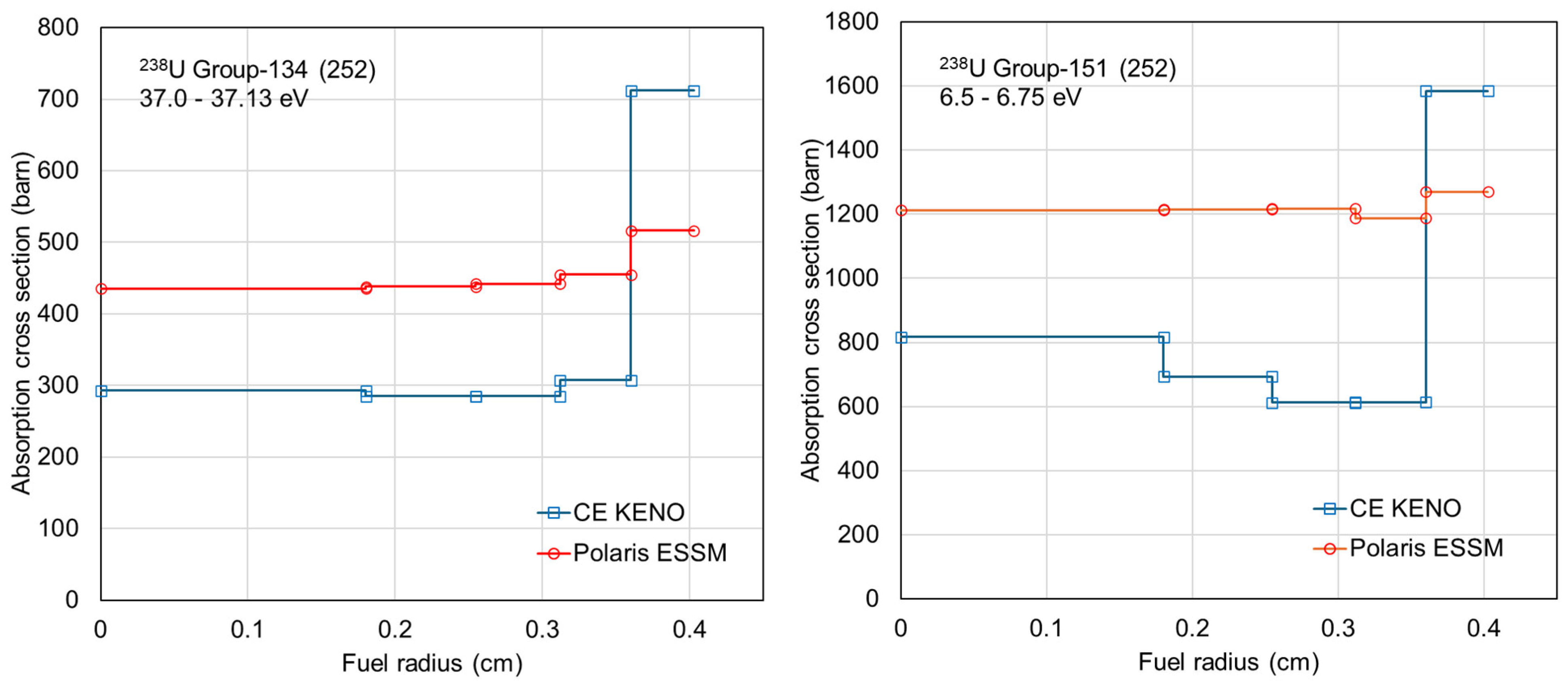

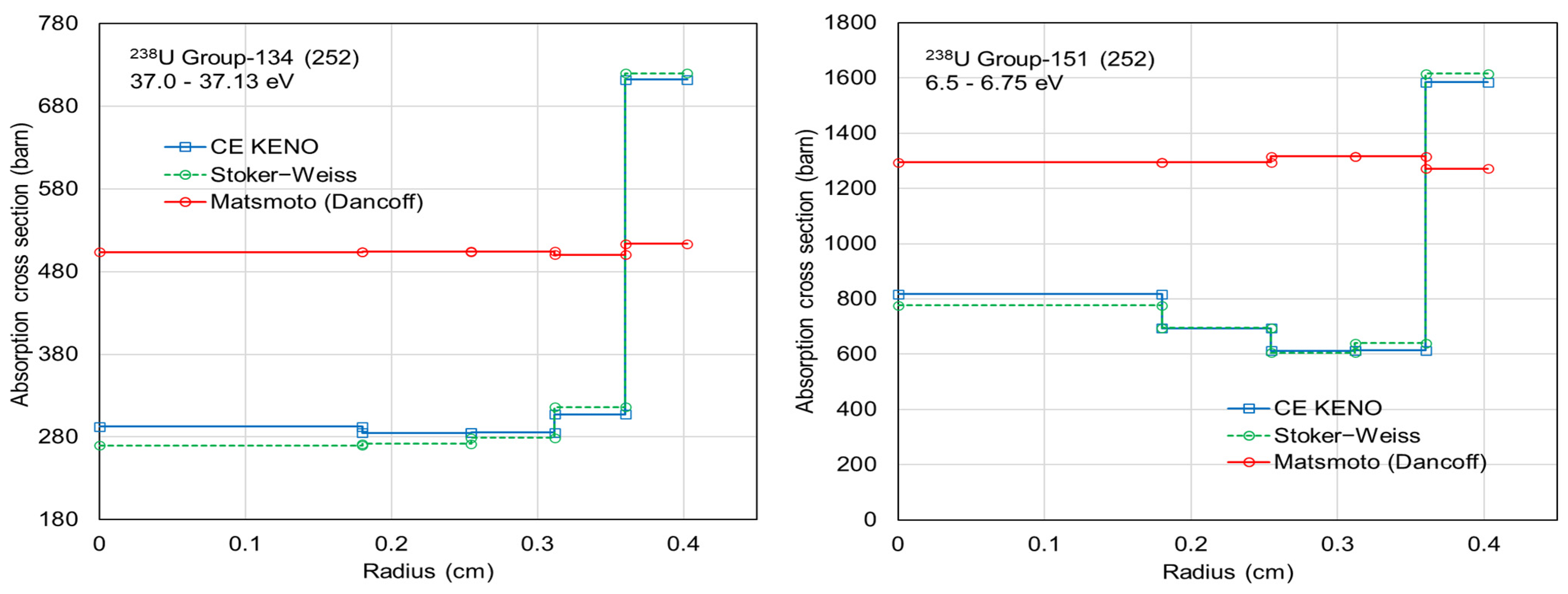

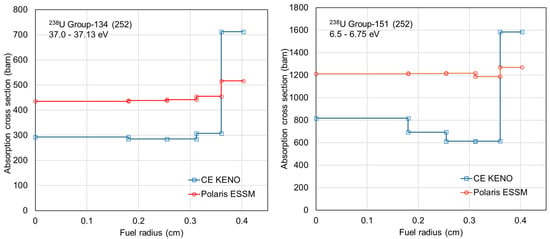

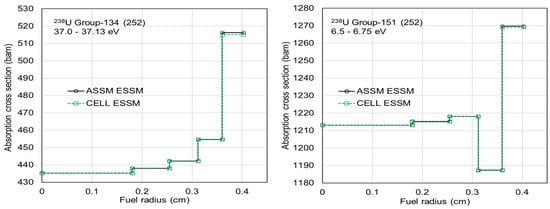

The ESSM calculation was performed for the PWR pin by using SCALE/Polaris, and the reference solution was obtained from the continuous-energy (CE) Monte Carlo calculation using SCALE/KENO. Ring-dependent self-shielded absorption cross sections for group-134 (37.0–37.13 eV) and group-151 (6.5–6.75 eV) within the SCALE 6.3 252-group structure for 238U are compared in Figure 2. Significant differences are observed in the ring-dependent self-shielded absorption cross sections between the CE Monte Carlo and Polaris ESSM calculations for 238U.

Figure 2.

Comparison of ring-dependent self-shielded absorption cross sections for 238U.

The Polaris calculations were performed for single-pin configurations with Al and Zr cladding using the ENDF/B-VII.1 AMPX 56- and 252-group libraries. Special resonance data for 91Zr and 96Zr were included in the AMPX 56-group library. As shown in the benchmark results in Table 2, the Polaris calculations for Al and Zr clads exhibit significant reactivity swings of approximately 400 pcm due to the clad material. While Al does not include any large resonance, Zr includes large capture resonances. These reactivity swings arise from an intrinsic limitation of the conventional ESSM, caused by strong, unphysical resonance interference between the Zr clad and fuel. Special resonance data for 91Zr and 96Zr improve the Polaris results for the Zr clad case but do not resolve the issue for the Al clad case. Consequently, a material grouping capability is required to avoid the need for special resonance data and to ensure applicability to any clad material.

Table 2.

Benchmark result for single-pin configuration.

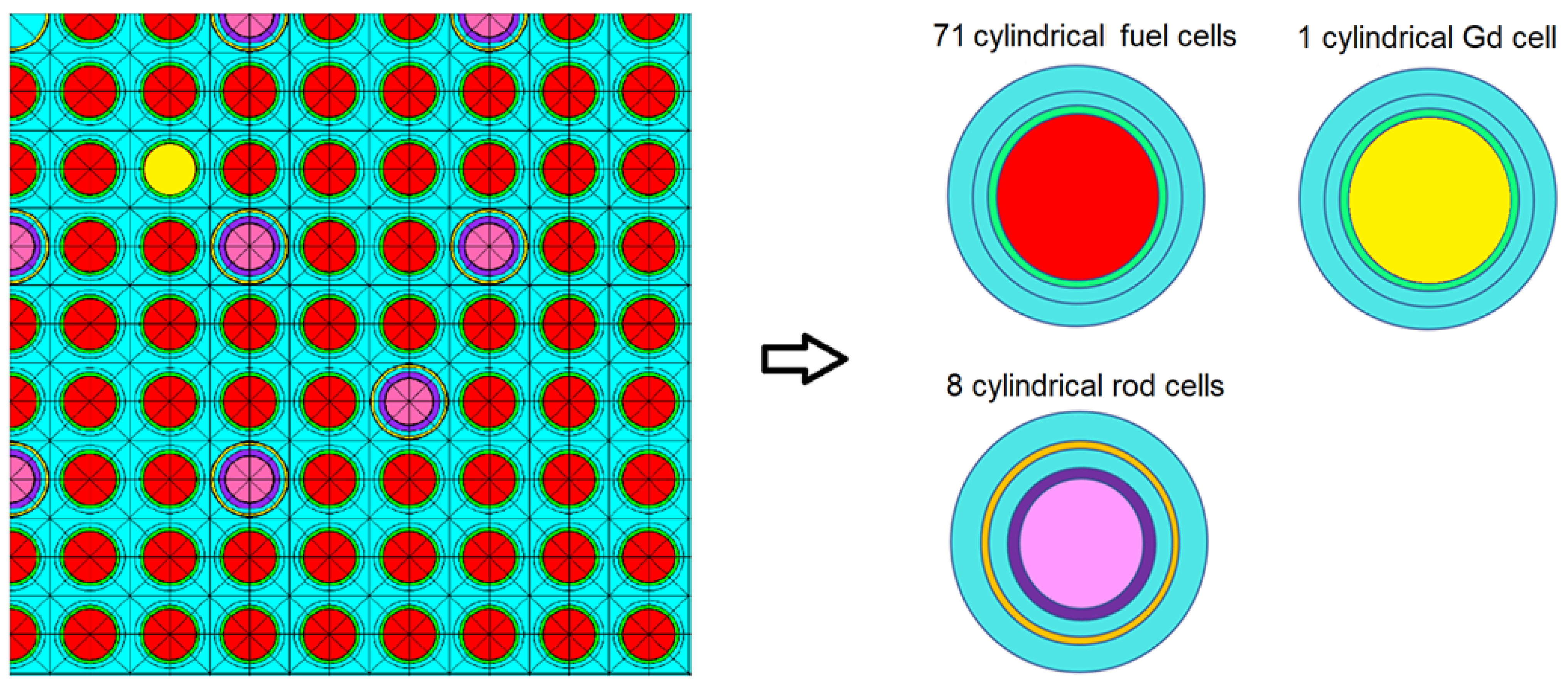

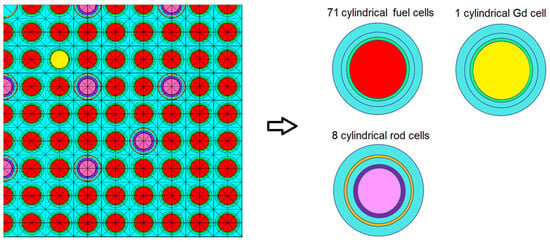

2.3. Dancoff-Based Wigner–Seitz Approximation

Two-dimensional MOC-based fixed-source transport calculations with black absorber approximation are performed to obtain Dancoff factors for fuels, control rods, and burnable poisons. Equivalent cylindrical pin cells with moderator are constructed with preserving volumes, as shown in Figure 3. The outermost radii of these cells are then adjusted to reproduce the same Dancoff factors as those obtained from the 2D MOC calculations for all constituent cylindrical cells. Fixed-source ESSM calculations are performed using a one-dimensional (1D) cylindrical collision probability method for all constituent cells. In addition, 1-group ESSM calculations are carried out for the entire domain to ensure that no resonance materials, such as structural materials, are omitted.

Figure 3.

Domain decomposition into 1D cylindrical cells.

Dancoff factors can be obtained by solving the fixed-source transport equation, shown in Equation (5), using 2D MOC in which a black absorber with 105 cm−1 total cross sections (Σk,i,t) is assigned to the resonance material zone.

where ψk indicates angular flux at the material zone k, i is the nuclide, and Σk,p is the potential cross section. The Dancoff factor (Dk) is calculated using Equation (6):

where is the mean chord length for the resonance material and ϕk is the scalar flux.

2.4. Spatially Dependent Embedded Self-Shielding Method

Stoker and Weiss proposed a simple method to obtain spatially dependent resonance cross sections in a cylindrical fuel rod [15]. Matsumoto et al. [16] developed a spatially dependent Dancoff method (SDDM) based on the conventional Dancoff method and the Stoker–Weiss approach. The present study focuses on developing a novel method of extending the conventional ESSM to accurately provide spatially dependent, effective cross sections at the intra-pin level by integrating the Stoker–Weiss method or SDDM with ESSM.

A detailed derivation of the SDDM equations is introduced in Stoker and Weiss [15] and Matsumoto et al. [16]. The resultant equations are presented here. The neutron spectrum for fuel rods with radial rings can be described as follows:

In Equation (7), Σt is the macroscopic total cross section at fuel region k, and lm is the mean chord length. Table 3 defines a mean chord length and Fm used in Equation (7). In Table 3, R is defined as the fuel pellet outer radius, , Vk is an area of radial ring k, and .

Table 3.

Definition of functions lm and Fm.

There are two options for and suggested by Stoker and Weiss and Matsumoto et al. Stoker and Weiss introduced , , , and . Matsumoto et al. introduced Equations (8)–(10) using a Dancoff factor to consider the neighboring effect. C is obtained from the Dancoff factor (D) using D = 1/(1 + C):

A formula for a flux-weighted MG self-shielded cross section can be derived as

where Νi is the atomic number density, is a microscopic background cross section for nuclide i, and Ri,x,g is a resonance integral for reaction x, defined as

The Stoker–Weiss equation is used solely to adjust the radial shapes of cross sections, whereas the average self-shielded cross section for an entire fuel pellet is determined by the conventional ESSM. Therefore, the first step is to perform the conventional ESSM calculation to obtain (1) average macroscopic background cross sections over fuel and (2) microscopic self-shielded cross sections. The second step is to solve the Stoker–Weiss equation and apply the resulting radial cross section shapes to each radial ring, as follows:

where K denotes fuel pin identification, and k is a radial ring inside K.

SCALE/Polaris was improved to include options for self-shielding calculation, as provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

SCALE/Polaris input options for ESSM.

2.5. Material-Based Category and Library Improvement

The original ESSM implementation performs iterative fixed-source calculations, updating background and absorption cross sections for all materials simultaneously. This approach can result in negative equivalence cross sections and unphysical resonance interference between fuel and cladding or control rods. To address this issue, the ESSM implementation was improved to perform separate fixed-source calculations for each material, thereby avoiding negative equivalence cross sections and unphysical resonance interference. The ESSM material grouping capability [18] was developed, as summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

SCALE/Polaris input option for ESSM material grouping.

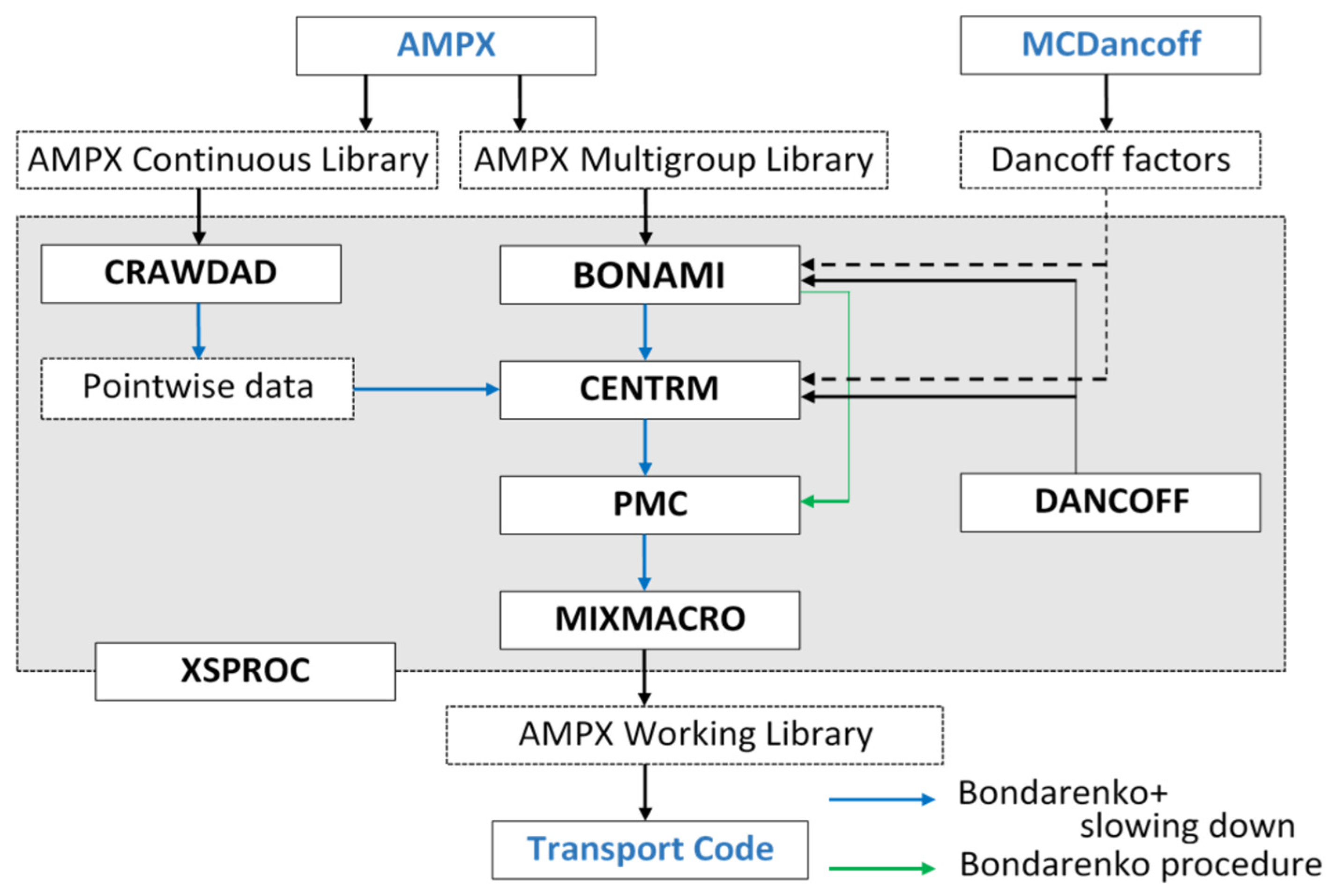

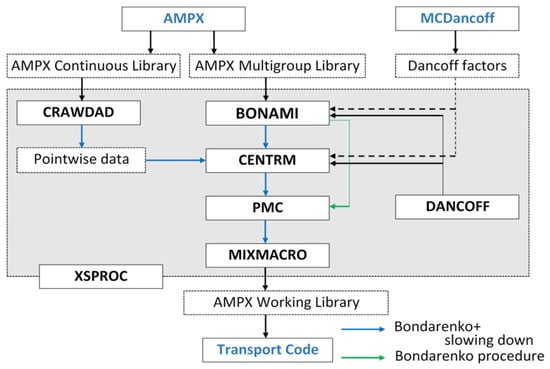

2.6. AMPX Multigroup Cross Section Processing

The SCALE neutron transport modules, including Polaris, NEWT, KENO, and Shift, require MG neutron cross sections to solve the Boltzmann transport equation and obtain the neutron flux distribution and eigenvalue. Evaluated nuclear data (e.g., ENDF/B) are processed to generate MG cross sections using AMPX-6 [3] and SCALE code packages. While SCALE transport modules such as NEWT, KENO, and Shift use effective self-shielded MG cross sections processed by SCALE/XSProc (Figure 4), the SCALE/Polaris lattice physics code directly uses the AMPX MG library. This library includes Bondarenko F-factors for various neutron reactions, defined as the ratios of resonance self-shielded cross sections to infinite dilution cross sections as a function of background cross sections for all energy groups, including both resolved and unresolved resonances. Resolved resonance F-factors are generated using the narrow resonance (NR) approximation, while unresolved resonance F-factors are generated by the probability table method based on the NR approximation.

Figure 4.

Flowchart of the XSProc procedure.

The AMPX MG library generation procedure includes six steps. (a) The AMPX MG library is generated using temperature-dependent pointwise (PW) weighting functions obtained from CENTRM PW slowing-down transport calculations. The resonance data are generated using the NR approximation. (b) IR parameters are generated, and the resonance data are updated with new data obtained from XSProc-CENTRM homogeneous slowing-down calculations using LAMBDA and IRFFACTOR-hom [19]. (c) Resonance data are updated with new data calculated by XSProc-CENTRM heterogeneous slowing-down calculations for important resonance nuclides using IRFFACTOR-het [19]. (d) Transport correction factors are generated for 1H by performing a fixed-source transport calculation. (e) Epithermal and non-epithermal upscattering resonance data are generated for 238U using the CE SCALE Monte Carlo code CE-KENO [19] and the ESSM [5]. SPH factors are obtained and incorporated into the resonance data. (f) The final step is to use AJAX to generate the final AMPX MG library with data prepared in steps (a) through (f).

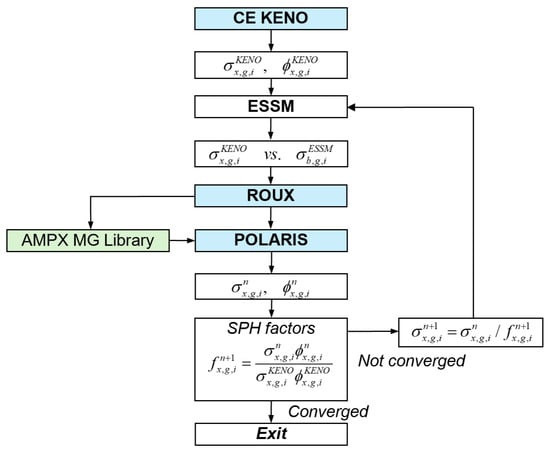

2.7. SPH Method for 238U Resonance Data

In performing coarse group transport calculations using the Bondarenko method for resonance self-shielding, three types of approximations are introduced as follows: (1) angle-independent total cross section, (2) P0 flux moment-weighted scattering matrices, and (3) implicit resonance interference based on the Bondarenko iteration. To address these issues simultaneously, various SPH methods have been developed to conserve reaction rates between high-order solutions and low-order approximations.

Collapsing energy groups from fine to coarse introduces angle-dependent total cross sections and high-order flux moment-weighted scattering matrices. Because angular fluxes and high-order flux moments are problem-dependent, it is not possible to generate coarse group resonance data and scattering matrices that fully account for the angle dependence of nuclear data. In addition, self-shielded cross section tables are generated by considering resonance interference effects between nuclides such as 238U and 235U in the CENTRM PW slowing-down calculation. This approach can provide improved agreement for specific cases in MG resonance self-shielded cross sections or reaction rates between reference and Polaris solutions.

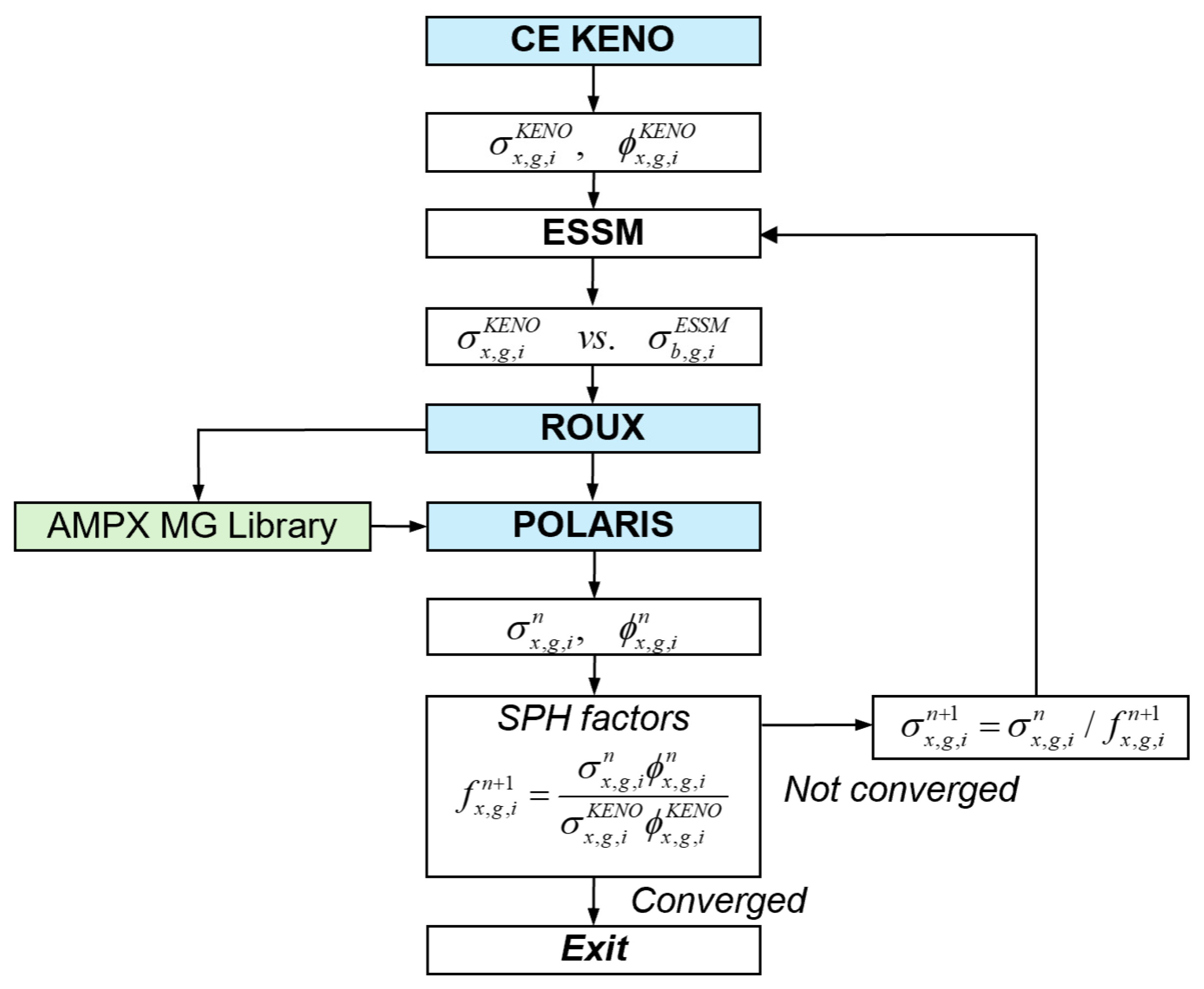

SPH was employed to address the issues described previously by conserving reaction rates between high-order reference solutions and low-order Polaris calculations. The procedure shown in Figure 5 begins with KENO models, including the same variation cases used in heterogeneous IRFFACTOR studies [19,20]. Next, the MG self-shielded cross sections are tallied, and the corresponding background cross sections are estimated using ESSM calculations to complete the self-shielded cross section tables. The updated resonance data are then incorporated into the AMPX MG library using ROUX. Finally, Polaris calculations are performed for the same variation cases to obtain the group-wise SPH factors, defined in Equations (15) and (16).

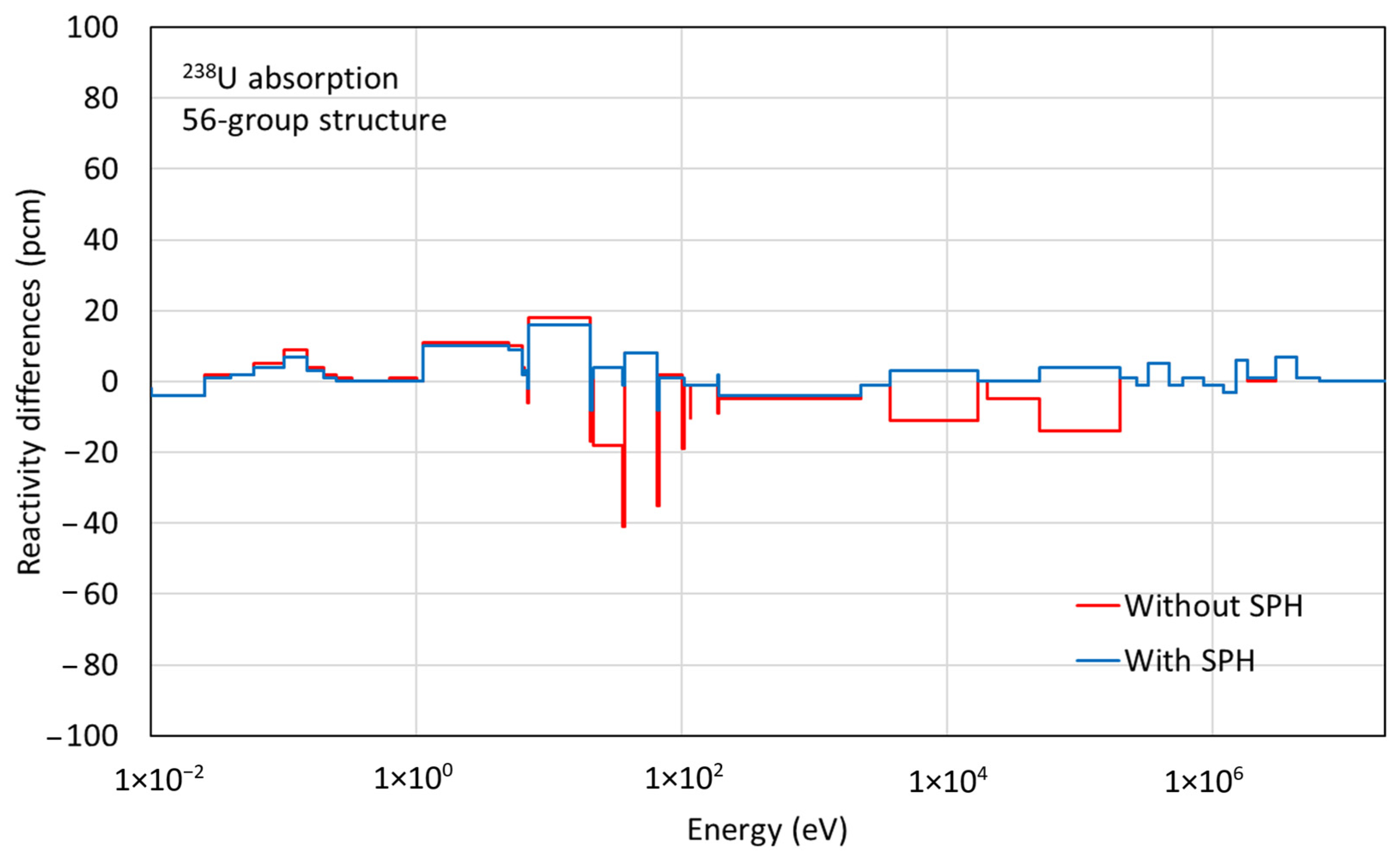

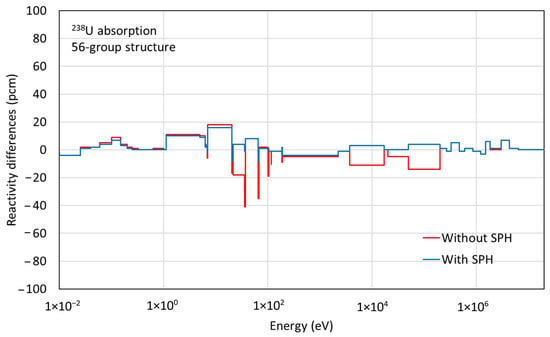

where denotes a microscopic cross section of reaction x of nuclide i at group g, and is the scalar flux. Figure 6 compares the 56-group absorption reaction rate differences in 238U compared to the CE Monte Carlo results with and without SPH factors for a single fuel pin, showing significant improvement when SPH factors are applied. New test ENDF/B-VII.1 AMPX 56- and 252-group libraries, incorporating SPH factors for 238U, were developed for this investigation.

Figure 5.

Flowchart of the SPH procedure.

Figure 6.

Comparisons of 238U 56-group reaction rates with and without SPH factors.

3. Benchmark Calculations and Results

3.1. Single-Pin Problem

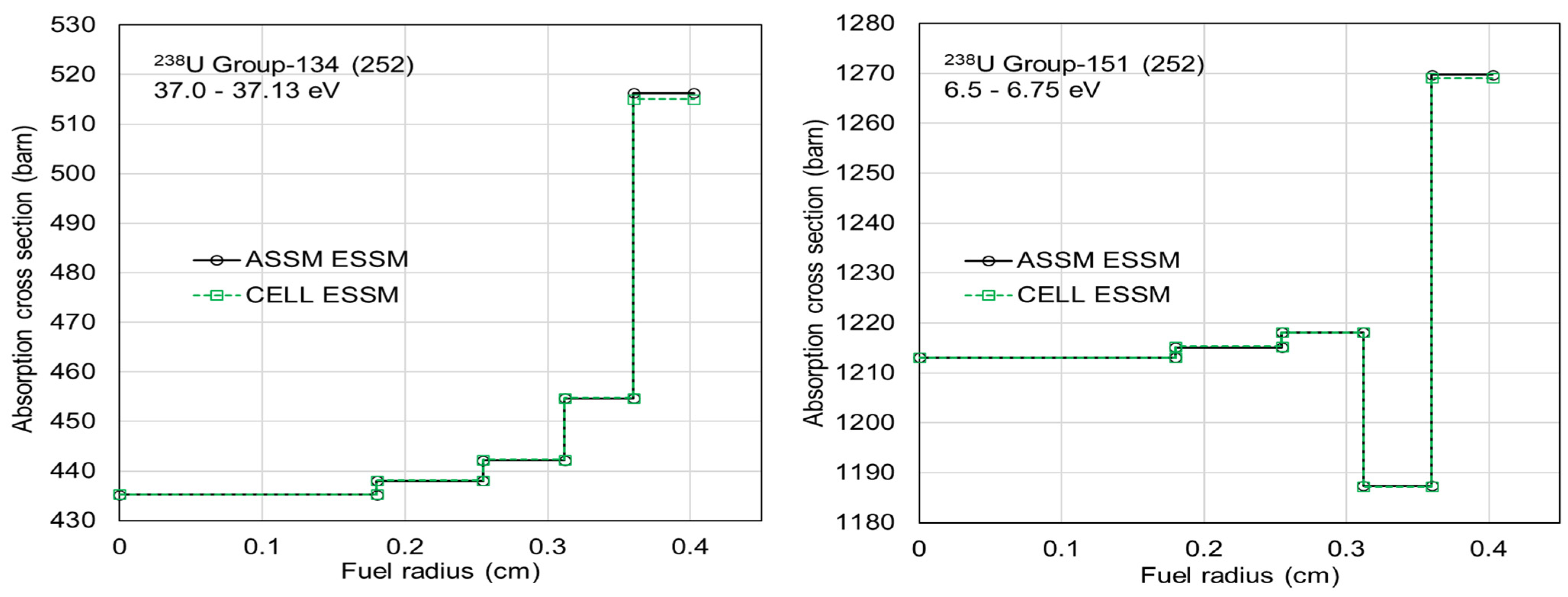

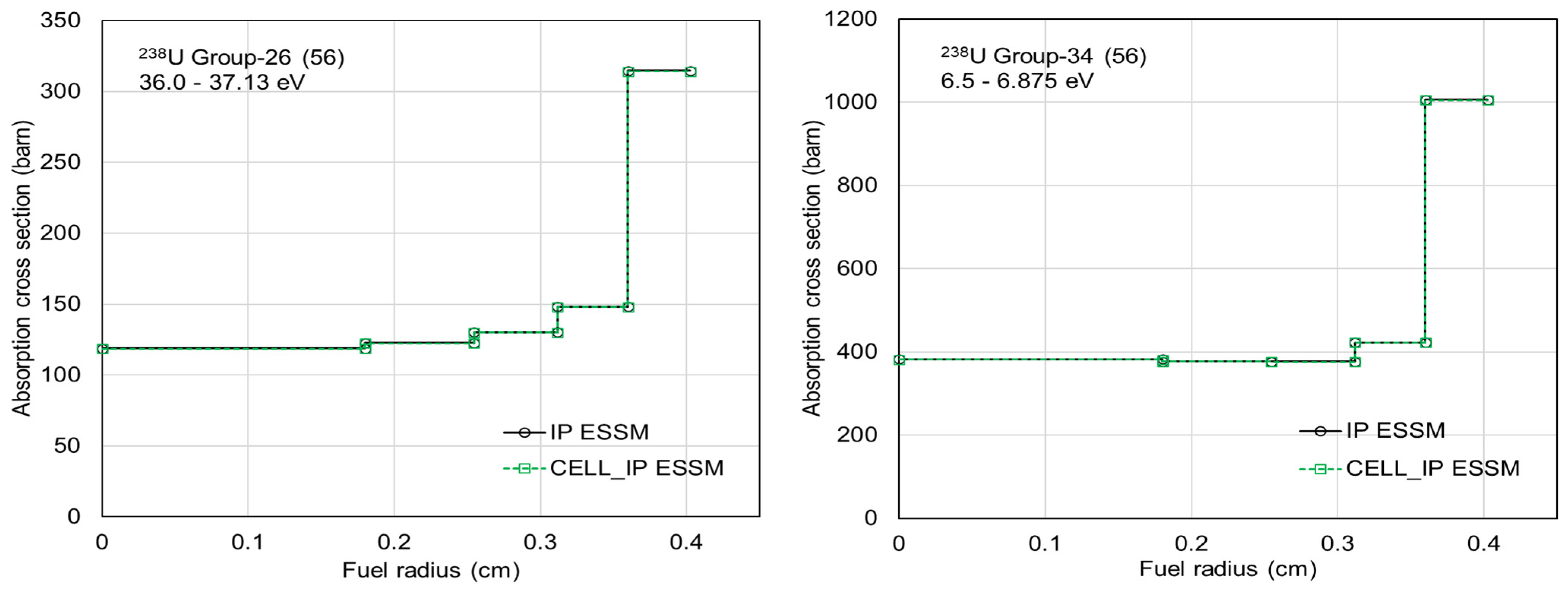

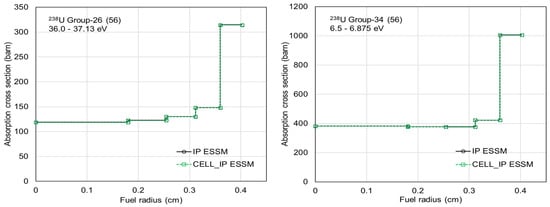

As indicated in Table 4, Polaris supports four ESSM options: ASSM, CELL, IP, and CELL_IP. While the ASSM and CELL options are based on the conventional ESSM, the IP and CELL_IP options support accurate calculation of spatially dependent self-shielded cross sections. The CELL and CELL_IP options provide faster self-shielding calculations compared with the ASSM and IP options, respectively. The same benchmark calculations used for Figure 2 were performed using the various ESSM options with the AMPX 56- and 252-group libraries. Figure 7 compares ring-dependent self-shielded absorption cross sections for group-134 (37.0–37.13 eV) and group-151 (6.5–6.75 eV) within the SCALE 252-group structure for 238U. The consistent ring-dependent self-shielded cross sections indicate that Polaris results with the CELL ESSM option are in agreement with results obtained using the ASSM ESSM option. Figure 8 compares ring-dependent self-shielded absorption cross sections for group-26 (37.0–37.13 eV) and group-34 (6.0–6.875 eV) within the SCALE 56-group structure for 238U. Similarly, the consistent ring-dependent self-shielded cross sections indicate that Polaris results with the CELL_IP ESSM option are in agreement with those obtained using the IP ESSM option.

Figure 7.

Comparison of ring-dependent self-shielded absorption cross sections between the ASSM and CELL ESSMs at 252-group structure for 238U.

Figure 8.

Comparison of ring-dependent self-shielded absorption cross sections between the IP and CELL_IP ESSMs at 56-group structure for 238U.

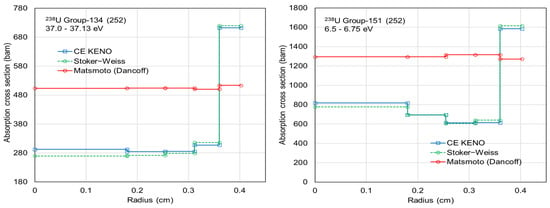

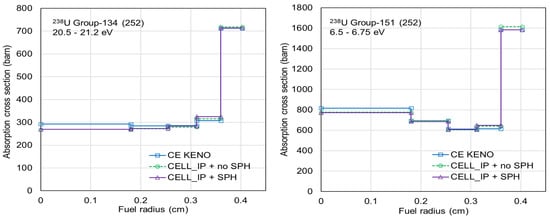

While Stoker and Weiss proposed a simple formula for an and bn, Matsumoto et al. introduced Equations (8)–(10) incorporating the Dancoff factor to account for neighboring effects. Both approaches were implemented into Polaris, and a sensitivity calculation was performed for the two options. Figure 9 compares ring-dependent self-shielded cross sections using CELL_IP for groups 134 and 151 within the 252-group structure between the reference solutions and the Stoker–Weiss and Matsumoto procedures. The Dancoff factor was obtained from Equation (6) by performing a fixed-source calculation with a black absorber. While ring-dependent self-shielded cross sections obtained using the Matsumoto procedure are not consistent with the reference solution, those obtained using the Stoker–Weiss procedure are in very good agreement with the reference. Matsumoto et al. did not provide a clear definition of the Dancoff factors, and the unclear definition may have resulted in unphysical ring-dependent self-shielded cross sections.

Figure 9.

Comparison of ring-dependent self-shielded absorption cross sections between the Stoker–Weiss and Matsumoto procedures at 252-group structure for 238U.

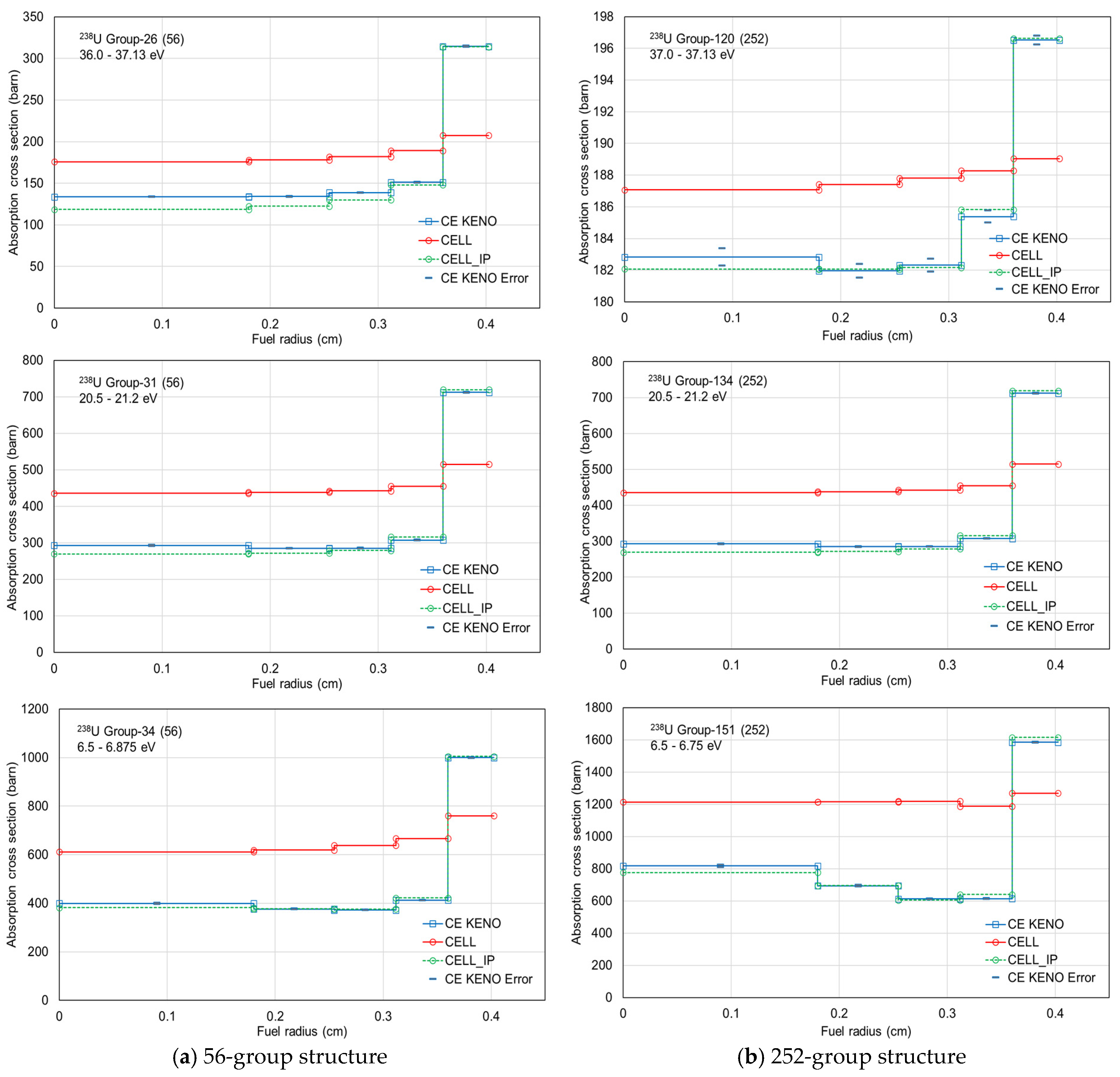

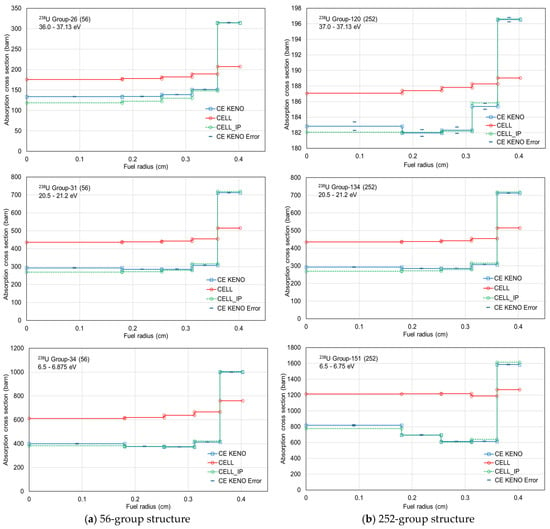

Since Figure 7 and Figure 8 demonstrate that the CELL and CELL_IP ESSM options correspond to the ASSM and IP ESSM options, respectively, the performance of CELL and CELL_IP for ring-dependent self-shielded cross sections was evaluated. Figure 10 compares ring-dependent self-shielded absorption cross sections for group-26 (36.0–37.13 eV), group-31 (20.5–21.2 eV), and group-34 (6.5–6.875 eV) within the SCALE 56-group structure, as well as for group-120 (37.0–37.13 eV), group-134 (20.5–21.2 eV), and group-151 (6.5–6.75 eV) within the SCALE 252-group structure for 238U. The ring-dependent self-shielded absorption cross sections obtained using the CELL_IP ESSM option are in very good agreement with the reference solutions.

Figure 10.

Comparison of ring-dependent self-shielded absorption cross sections between the CELL and CELL_IP ESSM options.

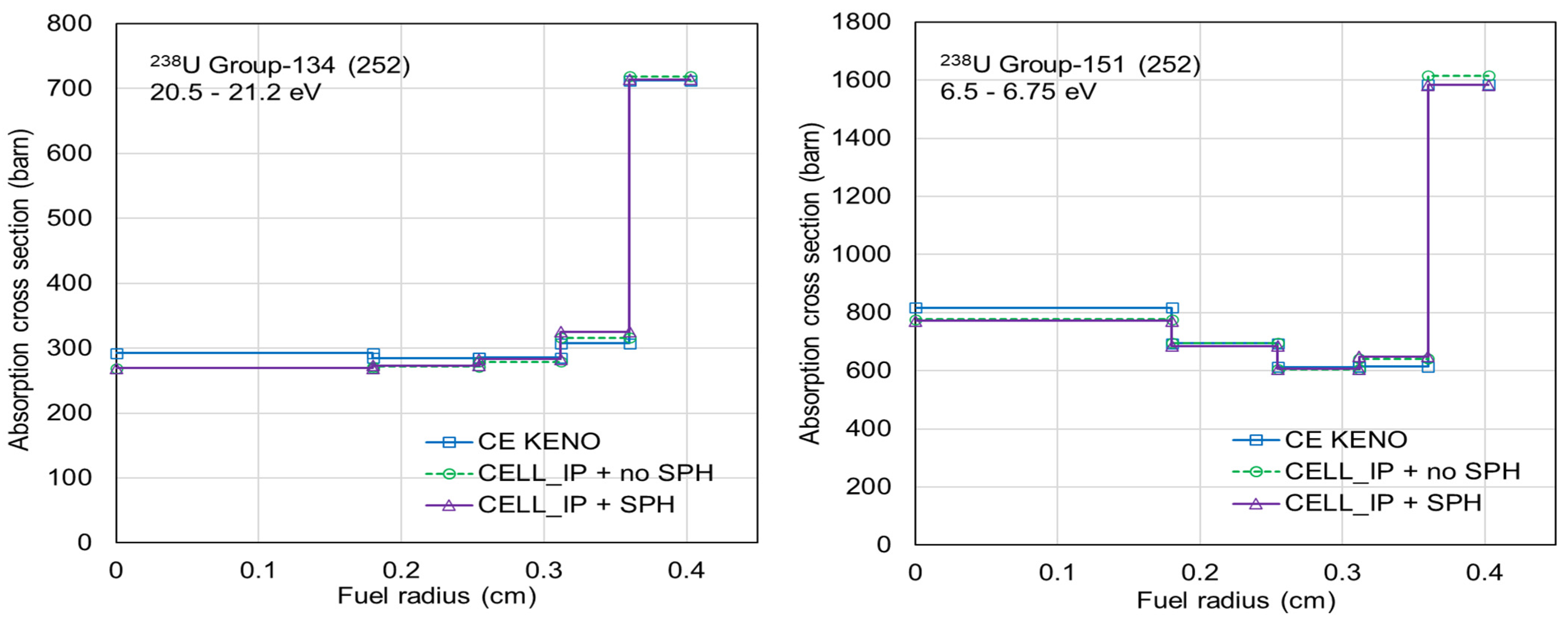

New test ENDF/B-VII.1 AMPX 56- and 252-group libraries were developed by incorporating the 238U SPH factors into the resonance self-shielded cross sections. Polaris benchmark calculations with the CELL_IP ESSM option were then performed using these ENDF/B-VII.1 AMPX 56- and 252-group libraries, both with and without the SPH factors for 238U. Figure 11 compares ring-dependent self-shielded cross sections for group-134 (20.5–21.2 eV) and group-151 (6.5–6.75 eV) for 238U within the SCALE 252-group structure, illustrating the effect of including the SPH factors, with only slight differences observed.

Figure 11.

Comparison of ring-dependent self-shielded absorption cross sections between the CELL_IP ESSMs with and without SPH factors.

3.2. VERA Core Physics Benchmark Progression Problems

The VERA core physics benchmark progression problems used in this study were developed to provide a framework for developing and demonstrating advanced capabilities in reactor physics methods and software [21]. Most of the benchmark data are based on the initial core loading of Watts Bar Nuclear Plant, Unit 1, a Westinghouse-designed 17 × 17 PWR that is representative of reactors built in the United States during the 1980s and 1990s.

For this study, the single-physics 2D benchmark problems were selected to evaluate the neutron cross section library for the CASL VERA neutronics simulator MPACT. Table 6 lists the VERA progression problems used for benchmarking. Detailed specifications of geometry and composition are provided by Godfrey [21]. Reference solutions were obtained using CE KENO with ENDF/B-VII.1.

Table 6.

Description of the VERA progression problems.

Benchmark calculations were performed with various ESSM options (ASSM, CELL, IP, and CELL_IP) in Polaris using the ENDF/B-VII.1 AMPX 56- and 252-group libraries, both with and without SPH factors for 238U. Default ray options were applied for the ESSM and eigenvalue MOC calculations, except for the IFBA (Integral Fuel Burnable Absorber) fuel pin and assembly cases (1E, 2L, 2M, and 2N), where a ray spacing of 0.001 cm was used. In addition, three and five intra-pin radial rings were modeled in Polaris for the UO2 fuel and gadolinia rods, respectively. All Polaris calculations were performed with P2 scattering. For the AMPX 56- and 252-group libraries without SPH factors, no material grouping was applied, whereas for the corresponding libraries with SPH factors for 238U, material grouping for fuels, cladding, and control rods was employed.

Table 7, Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10 present the benchmark calculation results, comparing the eigenvalues and pin power distributions obtained with Polaris against those from CE-KENO. The eigenvalues and pin power distributions show very good consistency across the ASSM, CELL, IP, and CELL_IP ESSM options. Although the Polaris ASSM and CELL ESSMs yield less accurate spatially dependent self-shielded cross sections, they still provide excellent agreement in multiplication factors with CE-KENO.

Table 7.

VERA benchmark results with the AMPX 56-group library without SPH.

Table 8.

VERA benchmark results with the AMPX 56-group library with SPH.

Table 9.

VERA benchmark results with the AMPX 252-group library without SPH.

Table 10.

VERA benchmark results with the AMPX 252-group library with SPH.

Table 11 compares the computing times of the ASSM, CELL, IP, and CELL_IP ESSM options using the AMPX 56- and 252-group libraries. The additional computing time required for spatially dependent self-shielding calculations is negligible, as is the associated memory overhead. The cell Dancoff-based Wigner–Seitz approximation for ESSM (CELL and CELL_IP) significantly enhances computational efficiency, achieving speedup factors of approximately 8 for fuel pins and greater than 10 for assemblies, without loss of accuracy.

Table 11.

Comparison of computing times.

3.3. Nonuniform and Uniform Fuel Temperature Benchmark Problems

Seoul National University developed a benchmark suite for intra-pellet uniform and nonuniform temperature distribution cases [22]. Table 12 provides the geometrical and compositional specifications, including dimensions, nuclides, and atomic number densities. Table 13 shows the nonuniform temperature profiles as functions of power and average fuel temperature.

Table 12.

Geometrical and compositional data.

Table 13.

Nonuniform temperature profiles as a function of power.

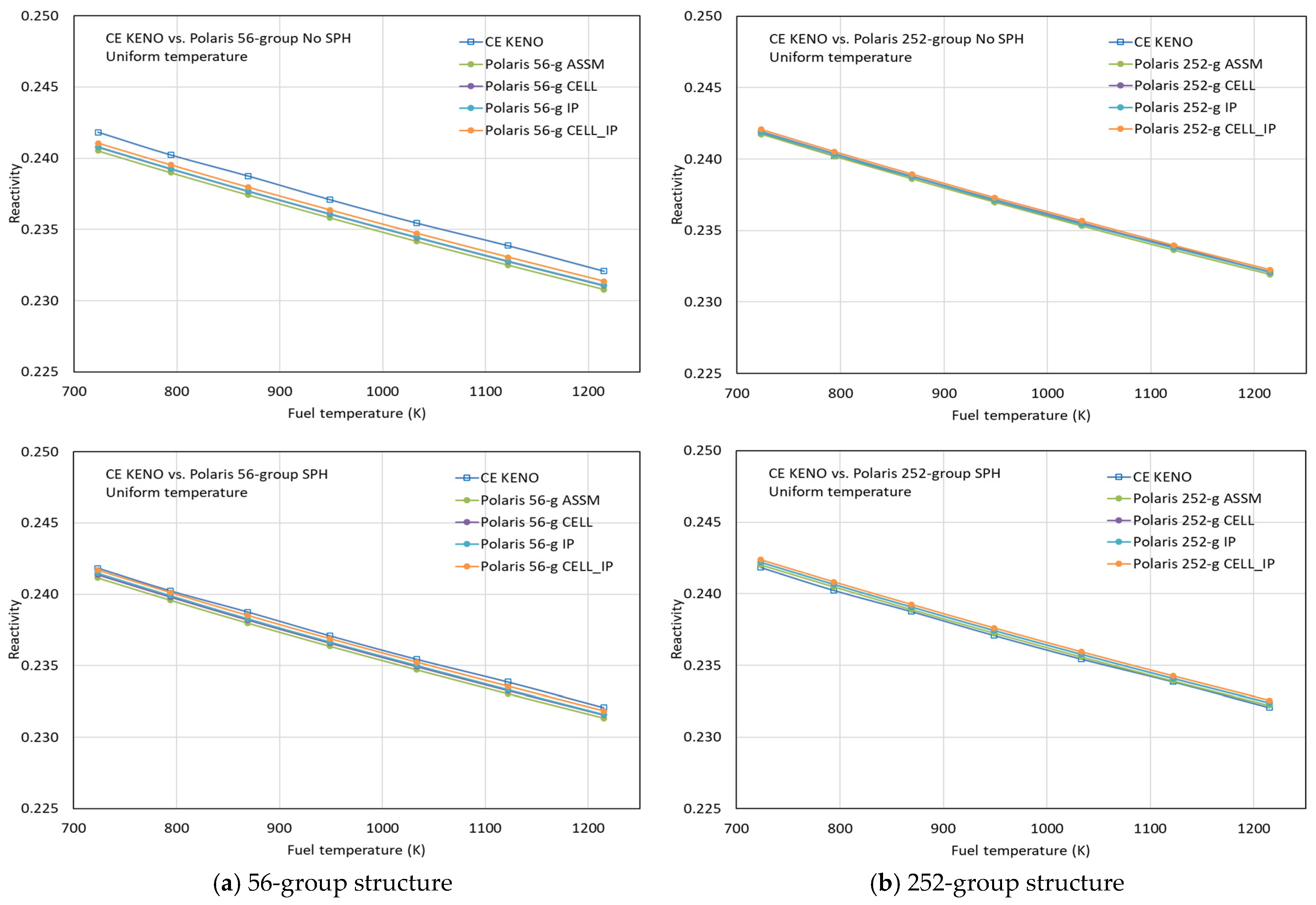

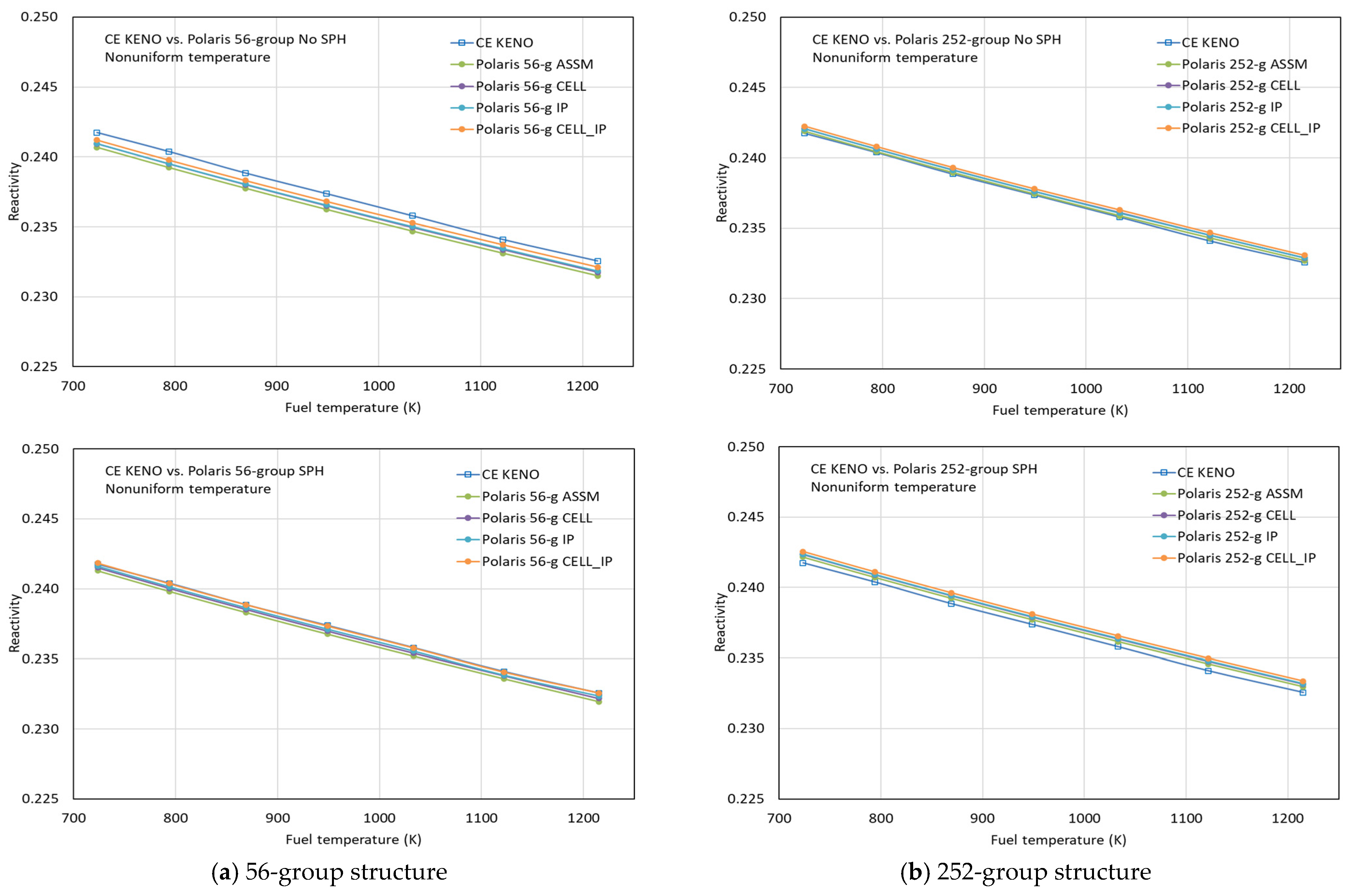

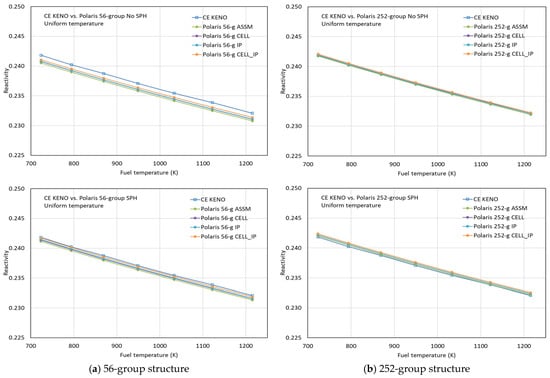

Benchmark calculations were performed for uniform and nonuniform temperature profiles using Polaris with P2 scattering and various ESSM options, including ASSM, CELL, IP, and CELL_IP. Figure 12 compares the reactivities for the uniform temperature profile obtained by CE KENO and Polaris with the different ESSM options, using the ENDF/B-VII.1 AMPX 56- and 252-group libraries with and without considering SPH factors for 238U. The Polaris results with the various ESSM options are highly consistent with the CE KENO results, with some improvement observed in the AMPX 56-group results when SPH factors are applied.

Figure 12.

Comparison of reactivities for the uniform temperature distributions.

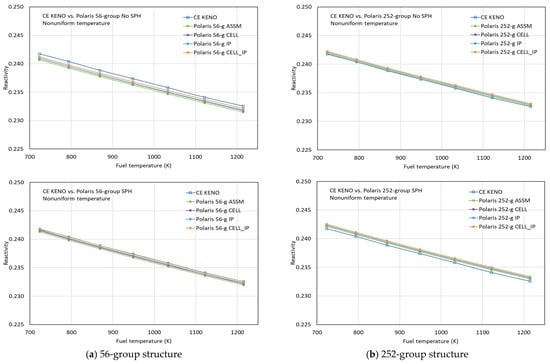

Figure 13 compares the reactivities for the nonuniform temperature profile obtained by CE KENO and Polaris with the ASSM, CELL, IP, and CELL_IP options, again using the ENDF/B-VII.1 AMPX 56- and 252-group libraries with and without SPH factors for 238U. The Polaris results show very good consistency with the CE KENO results. A similar improvement is observed for the nonuniform temperature profile in the AMPX 56-group results when SPH factors are applied. Strictly speaking, a fully spatially dependent ESSM capability for nonuniform temperature profiles could not be implemented in Polaris because of limitations in the Polaris metadata structure.

Figure 13.

Comparison of reactivities for the nonuniform temperature distributions.

Equations (7) and (11) include approximation for nonuniform temperature distribution. Assuming a single resonant nuclide without resonance interference, Equation (7) can be rewritten in MG form as derived using the subgroup method for nonuniform temperature distribution. This is accomplished by introducing correction factors for absorption cross sections that result from nonuniform temperature distribution [17]:

where

The correction factors can simply be applied to adjust background cross sections. Therefore, spatially dependent self-shielded cross sections for uniform and nonuniform temperature distributions can be obtained by

where

Even though this capability was not implemented into Polaris, the Polaris results for nonuniform temperature profiles with the IP and CELL + IP ESSM are very consistent with the CE KENO results. However, this capability would be very useful for high-fidelity multi-physics whole-core calculations.

3.4. Mosteller Benchmark Problems

The Mosteller benchmark [23] was developed to verify the Doppler temperature reactivity coefficient. The compositional and geometrical specifications are provided in Table 14 and Table 15.

Table 14.

Atomic number densities of UO2 fuels.

Table 15.

Atomic number densities of moderator and clad.

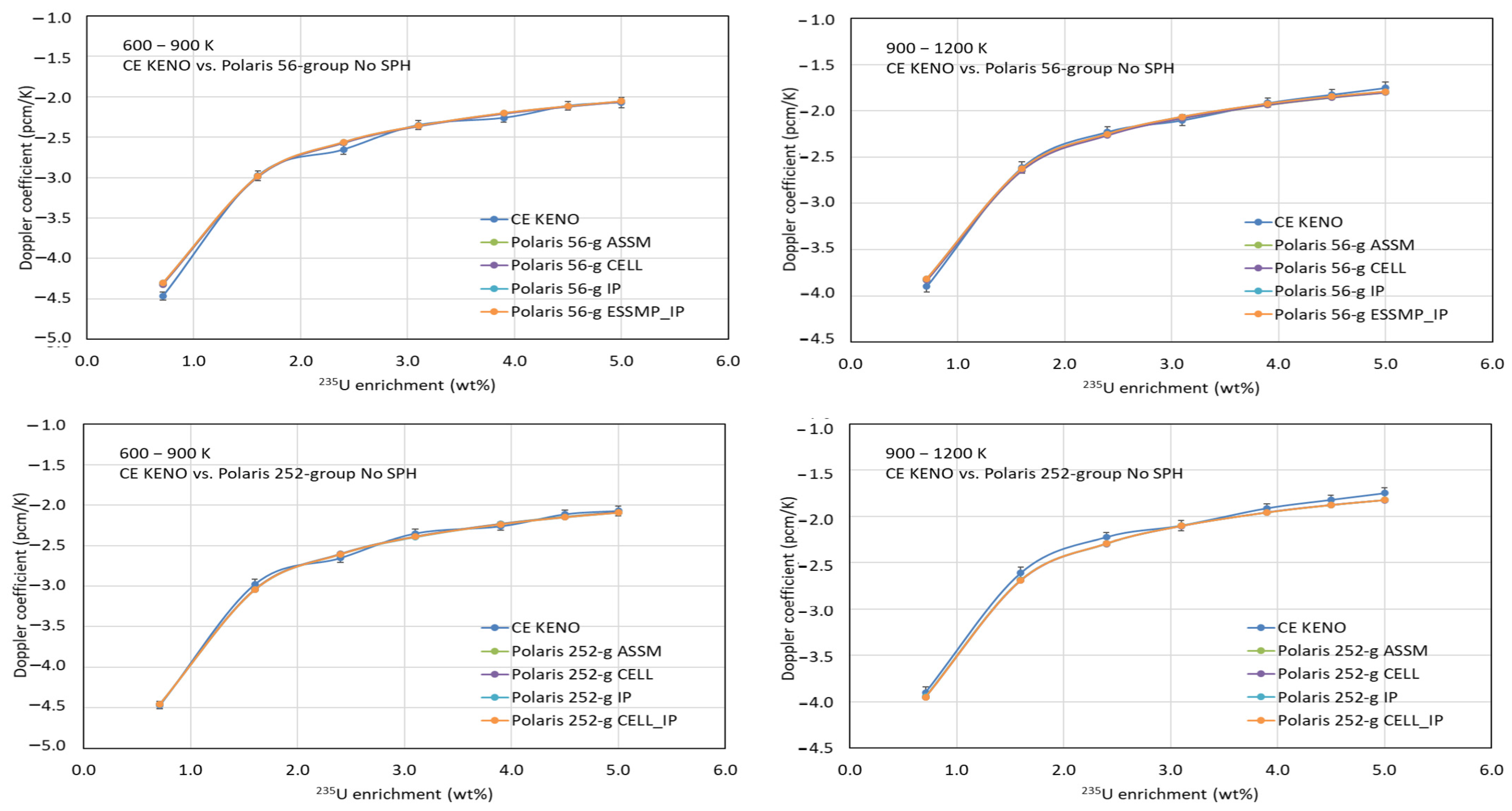

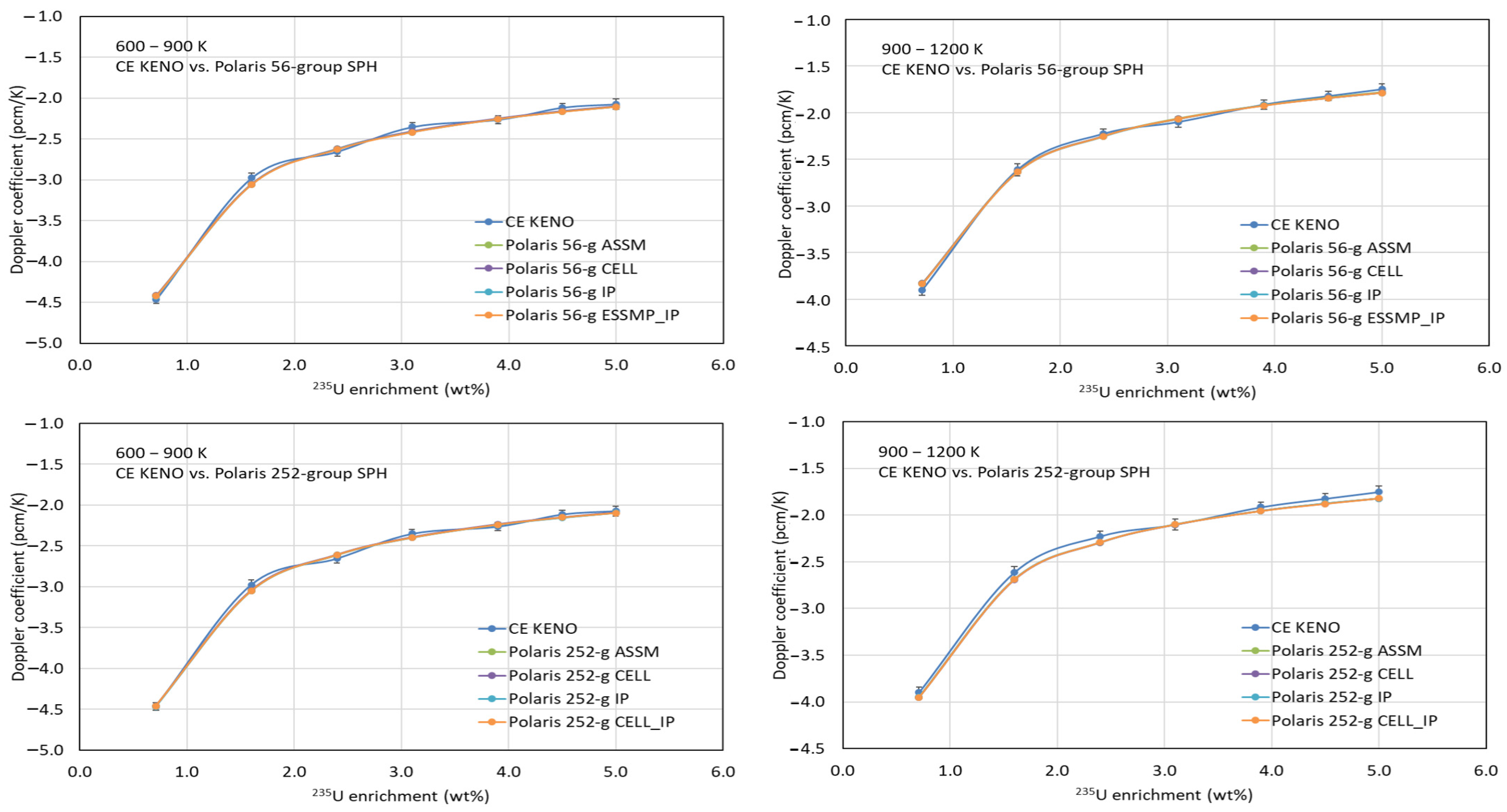

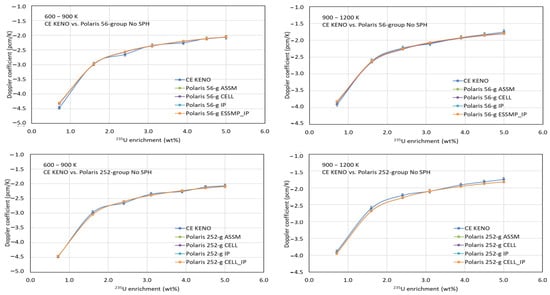

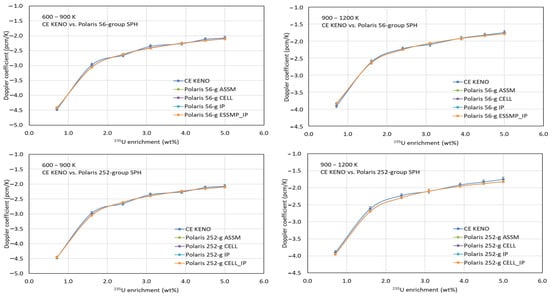

Benchmark calculations were performed using CE KENO and Polaris with the ENDF/B-VII.1 AMPX 56- and 252-group libraries, both with and without considering SPH. Figure 14 and Figure 15 compare Doppler temperature coefficients from KENO and Polaris using various ESSM options (ASSM, CELL, IP, and CELL_IP), both with and without considering SPH, respectively. The comparisons show very good agreement between Polaris and the Monte Carlo results across all temperature ranges.

Figure 14.

Comparison of Doppler coefficient (without SPH).

Figure 15.

Comparison of Doppler coefficient (with SPH).

3.5. VERA Depletion Benchmark Problems

The VERA PWR depletion benchmark problems [24] were developed based on the VERA progression problems [21]. These benchmark problems provide detailed geometrical and material data derived from VERA progression problems #1 and #2. The depletion benchmark suite includes eight single-pin and 16 fuel assembly problems with various fuel temperatures, 235U enrichments, control rods, and burnable poisons. Three representative problems were selected for this study, as listed in Table 16.

Table 16.

Single-pin and assembly depletion benchmark problems.

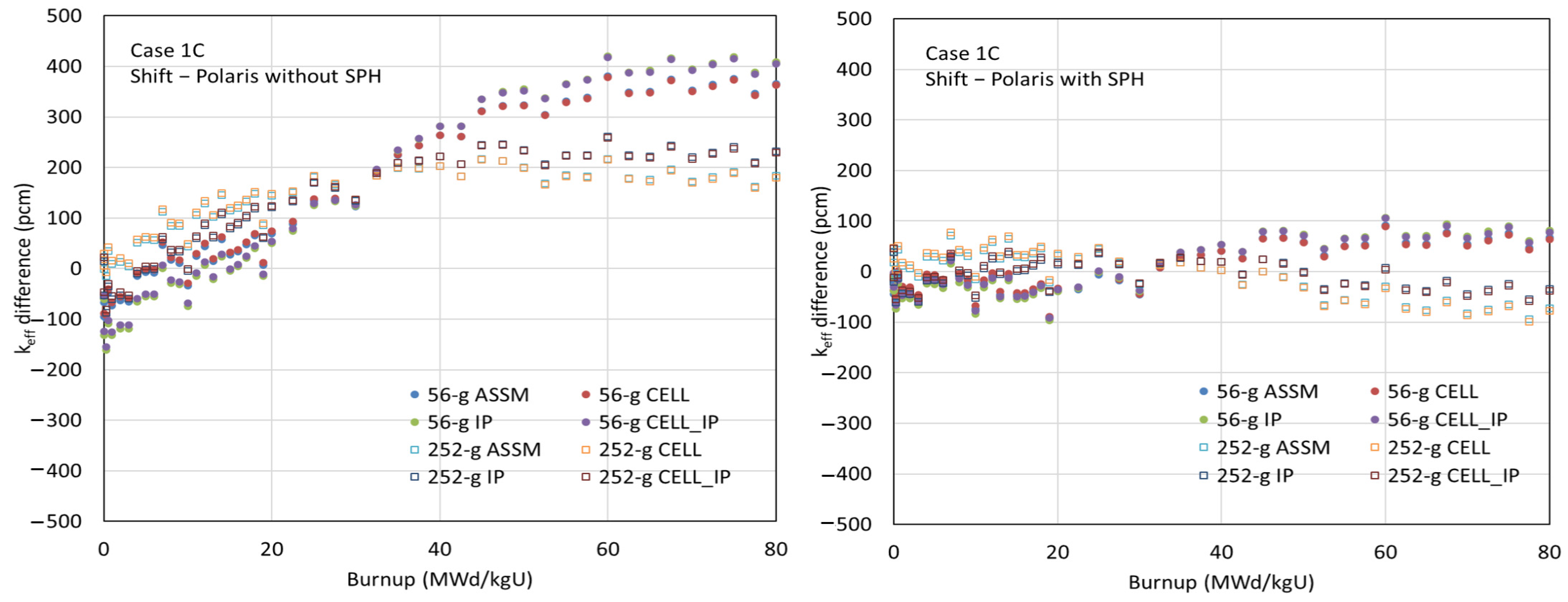

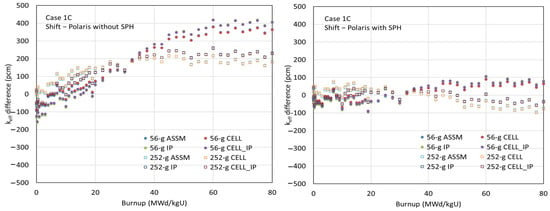

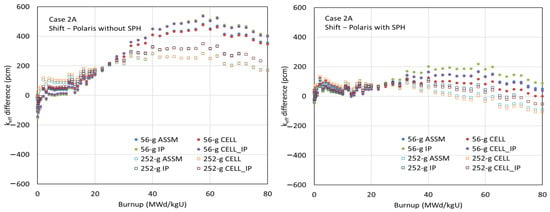

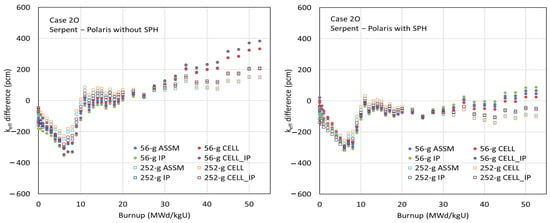

Benchmark calculations were performed for cases 1C, 2A, and 2O of the VERA PWR depletion problems [24] using Polaris with the ENDF/B-VII.1 AMPX 56- and 252-group libraries, both with and without SPH factors for 238U. Reference solutions were obtained using CE Shift and Serpent calculations, in which the same fission κ (recoverable energy per fission) values were applied, and capture κ (recoverable energy per capture) values were incorporated into the fission κ values, as specified in the VERA PWR depletion benchmark problems.

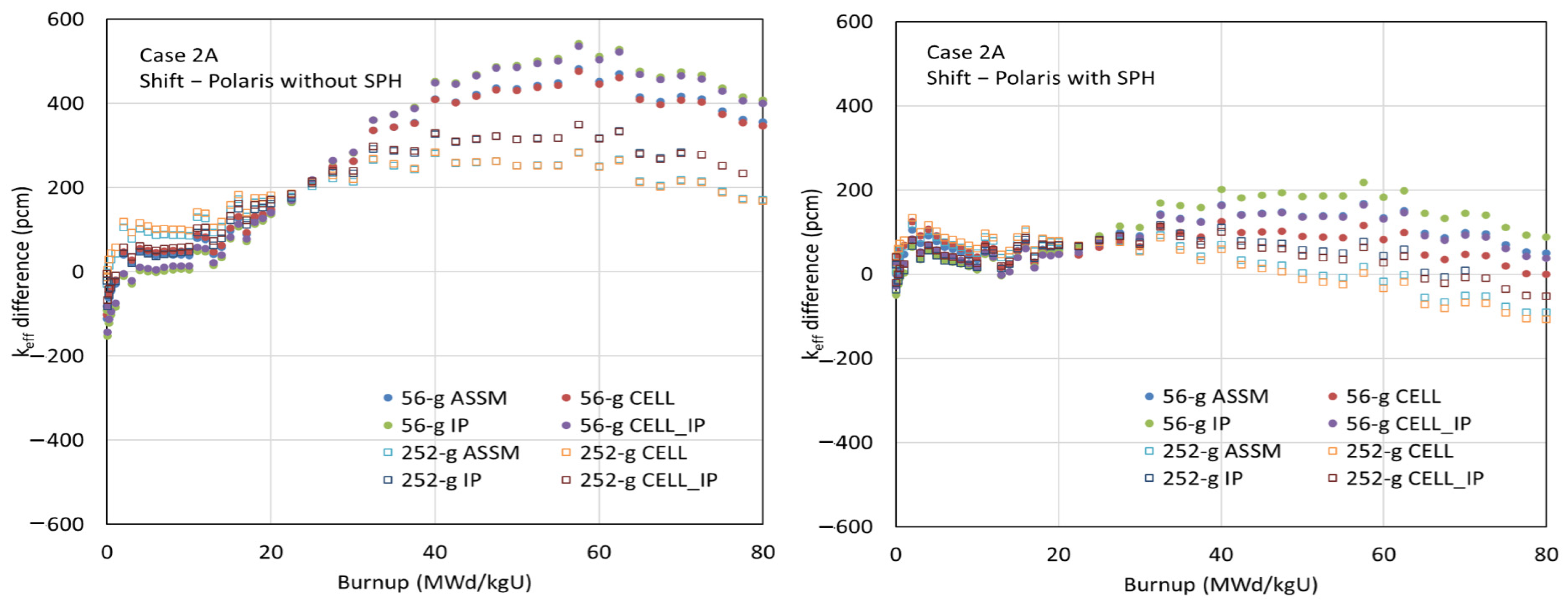

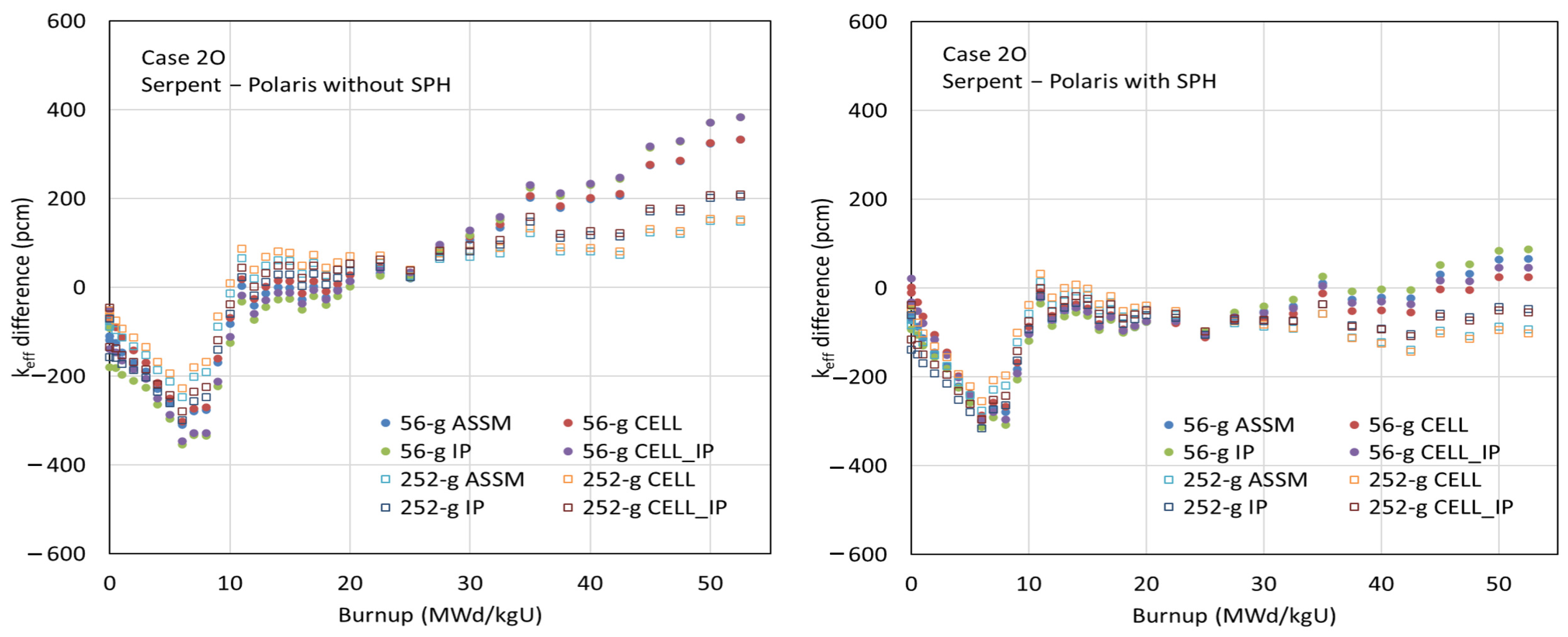

Figure 16, Figure 17 and Figure 18 compare the multiplication factors as a function of burnup for cases 1C, 2A, and 2O between the CE Shift and Polaris results using various ESSM options, with the ENDF/B-VII.1 AMPX 56- and 252-group libraries, both with and without SPH factors for 238U. The left-hand graphs in the figures show the benchmark results using the AMPX 56- and 252-group libraries without SPH factors. Slight reactivity differences are observed among the ESSM options—ASSM, CELL, IP, and CELL_IP—indicating that the less accurate spatially dependent self-shielded cross sections in ASSM and CELL do not significantly affect the depletion results.

Figure 16.

Comparison of the multiplication factors as a function of burnup for case 1C.

Figure 17.

Comparison of the multiplication factors as a function of burnup for case 2A.

Figure 18.

Comparison of the multiplication factors as a function of burnup for case 2O.

Although excellent agreement in multiplication factors is observed at zero burnup between the AMPX MG libraries with and without SPH factors, significant reactivity biases appear at high-burnup points when SPH factors are not considered. In the conventional ESSM, strong unphysical resonance interference occurs between clad and fuel, necessitating special resonance data, particularly for 91Zr and 96Zr in coarse group structures. Even though the interference between clad and fuel is weaker in fine group structures, error cancellation can still impact the depletion results, introducing large reactivity biases at high burnup. It is physically expected that collapsing energy groups from fine to coarse in a problem-independent manner introduces reaction rate differences due to the lack of angle-dependent total cross sections and P0 flux moment weighting.

As shown in the figures, the depletion benchmark results using the AMPX MG libraries with SPH factors and material grouping are highly consistent with the reference results obtained from CE Monte Carlo calculations.

4. Conclusions

The ESSM is currently the primary resonance self-shielding method used in SCALE’s lattice physics code, Polaris. In this study, the conventional ESSM has been extended to accomplish the following:

- Provide accurate, spatially dependent effective cross sections at the intra-pin level using the Stoker–Weiss method.

- Include a material grouping capability to avoid special resonance data, supported by a new resonance data generation procedure incorporating SPH factors.

- Significantly enhance computational efficiency in ESSM self-shielding calculations.

Although the conventional ESSM remains acceptable, as demonstrated in the benchmark results, the extended ESSM offers improved accuracy and computational efficiency. The conventional ESSM exhibits significant errors in spatially dependent self-shielded cross sections when multiple intra-pin radial rings are included. Additionally, it introduces strong unphysical resonance interference between fuel and cladding, which requires special resonance data—particularly for 91Zr and 96Zr in coarse group structures—and can result in reactivity biases at high burnup. This resonance interference leads to some error cancellation, which is unphysical but may not require adjustments to resonance data inherently introduced during energy group collapsing. Because the ESSM equations are solved numerically using the MOC in Polaris, the computations are expensive, accounting for approximately 30% of the total computing time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S.K.; formal analysis, K.S.K., M.J. and A.H.; investigation, K.S.K., M.J. and A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, K.S.K.; writing—review and editing, W.W.; supervision, W.W.; project administration, W.W.; funding acquisition, W.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission Office of Research contract number 31310019N0008.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to dataset restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wieselquist, W.A.; Lefebvre, R.A. (Eds.) SCALE 6.3.1 User Manual; ORNL/TM-SCALE-6.3.1; UT-Battelle, LLC, Oak Ridge National Laboratory: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2023. Available online: https://scale-manual.ornl.gov/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Jessee, M.A.; Wieselquist, W.A.; Mertyurek, U.; Kim, K.S.; Evans, T.M.; Hamilton, S.P. Lattice Physics Calculations Using the Embedded Self-Shielding Method in Polaris, Part I: Methods and Implementation. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2021, 150, 107830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiarda, D.; Dunn, M.E.; Green, N.M.; Williams, M.L.; Celik, C.; Petrie, L.M. AMPX-6: A Modular Code System for Processing ENDF/B; ORNL/TM-2016/43; Oak Ridge National Laboratory: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2016.

- Hong, S.G.; Kim, K.S. Iterative Resonance Treatment Methods Using Resonance Integral Table in Heterogeneous Transport Lattice Calculations. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2011, 38, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.L.; Kim, K.S. The Embedded Self-Shielding Method. In Proceedings of the PHYSOR 2012, Knoxville, TN, USA, 15–20 April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Khairallah, A.; Recolin, J. Calcul de l’autoprotection résonnante dans les cellules complexes par la méthode des sous-groupes. In Proceedings of the Seminar IAEA-SM-154 on Numerical Reactor Calculations, IAEA, Vienna, Austria, 17–21 January 1972; pp. 305–317. [Google Scholar]

- Stamm’ler, R.J.J. The HELIOS Methods; Studsvik Scandpower: Idaho Falls, ID, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.S. Comparison between Spatially Dependent Embedded Self-Shielding and Subgroup Methods. Trans. Am. Nucl. Soc. 2018, 119, 1193–1196. [Google Scholar]

- Stamm’ler, R.J.J.; Abbate, M.J. Methods of Steady-State Reactor Physics in Nuclear Design; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.S.; Lee, C.C.; Zee, S.Q. General Geometry Capability in the Transport Lattice code LIBERTE. In Proceedings of the KNS 2004 Autumn Meeting, Yongpyong, Republic of Korea, 1 July 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji, K.; Koike, H.; Kamiyama, Y.; Kirimura, K.; Kosaka, S. Ultra-Fine-Group Resonance Treatment Using Equivalent Dancoff-Factor Cell Model in Lattice Physics Code GALAXY. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 756–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H. Resonance Treatment Innovations for Efficiency and Accuracy Enhancement in Direct Whole Core Calculations of Water-Cooled Power Reactors. Ph.D. Thesis, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, L.; Zmijarevic, I.; Sanchez, R. A Subgroup Method Based on the Equivalent Dancoff-Factor Cell Technique in APOLLO3® for Thermal Reactor Calculations. Ann. Nucl. Energ. 2020, 139, 107212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCALE: A Modular Code System for Performing Standardized Computer Analyses for Licensing Evaluation; ORNL/TM-2005/39, Version 6; Oak Ridge National Laboratory: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2009; Volume I–III.

- Stoker, C.C.; Weiss, Z.J. Spatially Dependent Resonance Cross Sections in a Fuel Rod. Ann. Nucl. Energy 1996, 23, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, H.; Ouisloumen, M.; Takeda, T. Development of Spatially Dependent Resonance Shielding Method. J. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 2005, 42, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S.; Williams, M.L. Spatially Dependent Embedded Self-Shielding Method for Nonuniform Temperature Distribution. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2019, 132, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, C.A.; Jessee, M.A.; Kim, K.S. Improvement in the Polaris Implementation of the Embedded Self-Shielding Method. In Proceedings of the PHYSOR 2018, Cancun, Mexico, 22–27 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.S.; Williams, M.L.; Wiarda, D.; Clarno, K.T. Development of the Multigroup Cross Section Library for the CASL Neutronics Simulator MPACT: Method and Procedure. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2019, 133, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S.; Asgari, M. Subgroup Resonance Self-Shielding Methods with Two-Term Functionalization for VERA-MPACT. Trans. Am. Nucl. Soc. 2024, 130, 1026–1029. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, A.T. VERA Core Physics Benchmark Progression Problem Specifications; CASL-U-2012-0131-004; Oak Ridge National Laboratory: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2014.

- Joo, H.G.; Han, B.S.; Kim, C.H.; Kim, K.S. Implementation of Subgroup Method in Direct Whole Core Transport Calculation Involving Nonuniform Temperature Distribution. In Proceedings of the M&C 2005, Avignon, France, 12–16 September 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mosteller, R. The Doppler-Defect Benchmark: Overview and Summary of Results. In Proceedings of the M&C+SNA 2007, Monterey, CA, USA, 15–19 April 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.S. Specification for the VERA Depletion Benchmark Suite; CASL-U-2015-1014-000, ORNL/TM-2016/53; Oak Ridge National Laboratory: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2016.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.