Abstract

To evaluate the consumption of ultra-processed foods (UPFs), culinary abilities, and food addiction (FA) in adults after different periods since bariatric and metabolic surgery, this cross-sectional study recruited and collected data via social media from adults who underwent metabolic and bariatric surgery. The Brazil Food and Nutritional Surveillance System markers of dietary consumption and the NOVA-UPF screener assessed dietary patterns and UPF consumption, the modified Yale Food Addiction Scale 2.0 assessed FA, and the Cooking Skills Index (CSI) assessed culinary abilities. 1525 participants were included, with a mean age of 38 ± 8 years and a mean time since surgery of 37 ± 54 months. Individuals with longer postoperative time showed a higher NOVA-UPF score and higher consumption of hamburgers/sausages, sweetened beverages, and instant noodles (p < 0.01 for all), without a corresponding decrease in fresh fruit and vegetable consumption. Each year since surgery increased NOVA-UPF score by 0.67 [CI95%: 0.57; 0.76] points. CSI showed no association with time (−0.41; [CI95%: −1.33; 0.50]), while FA prevalence was lowest at 48 months and increased thereafter (p < 0.01). FA prevalence initially decreased up to 4 years post-surgery, followed by a partial increase beyond 4 years, although remaining below levels observed within the first 6 months. Time since surgery is associated with higher UPF consumption and a non-linear trajectory of FA prevalence, but not with culinary abilities.

1. Introduction

Over the years, the prevalence of obesity has increased dramatically worldwide, and it was estimated that in 2022, it affected 890 million people [1]. In Brazil, data from the Surveillance of Risk and Protective Factors for Chronic Diseases via Telephone Survey (VIGITEL) indicate that the obesity rate among adults residing in the country’s capitals is 24.3%, with a higher prevalence among women (24.8%) [2]. It is well known that obesity is associated with a range of clinical conditions such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and various types of cancer [3]. Moreover, the economic and social costs linked to obesity—including premature death, reduced productivity, high direct and indirect costs, and increased healthcare expenditures—have already been documented [4,5,6,7]. Consequently, the treatment of this condition becomes indispensable for improving an individual’s quality of life and reducing its associated consequences [8].

Bariatric and metabolic surgery (BMS) is an alternative treatment for obesity. It is recognized for providing significant, sustained weight loss, and for contributing to the control of associated comorbidities through modifications to the gastrointestinal tract, potentially altering the stomach’s anatomy and/or modifying the passage of food through the digestive system [9,10]. This direct intervention on the gastrointestinal tract can induce metabolic changes as well as alterations in appetite and satiety, which result in weight loss and improved management of the patient’s comorbidities [10,11,12,13]. Despite the impact of BMS and its satisfactory outcomes in weight loss and comorbidity control, maintaining the lost weight remains one of the greatest challenges for patients. Several factors may be associated with weight regain, one of which is related to these individuals’ dietary intake [14].

The population’s dietary pattern has been changing in recent years, with a significant increase in the consumption of ultra-processed foods (UPFs), which raises concerns about the health impacts of this habit [15,16,17]. UPFs are foods that generally have a high energy density and are poor in nutrients, and their consumption is associated with weight gain [18]. Pinto, Silva, and Bressan (2019) observed a reduction in UPF consumption at 3 and 12 months after bariatric and metabolic surgery (BMS), as was demonstrated by another subsequent study [19,20]. However, this reduction in UPF consumption does not appear to be maintained in the long term, with intake levels potentially reverting to those observed prior to the procedure at 2 and 5 years post-BMS, contributing to weight regain [21,22]. Therefore, it is essential to understand how this dietary change influences individuals undergoing BMS, given that the procedure has various metabolic and lifestyle repercussions for patients [23].

In this context, it is important to investigate which individual characteristics may be associated with the increased consumption of UPFs. Among these characteristics, food addiction (FA) appears to be a possible explanation. FA is characterized by the excessive consumption of UPFs, accompanied by symptoms similar to those of substance use disorders [24]. Its assessment is carried out using the Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS) and its adaptations, which modify the diagnostic criteria for substance use disorders to evaluate FA specifically. This instrument evaluates self-reported symptoms related to the intake of foods high in simple carbohydrates or added fats, such as sweets and salty snacks, features that are common in UPFs, and associations between UPFs and FA have been observed [25,26,27]. Individuals with FA are more likely to compulsively consume these foods, with prolonged adherence to caloric restriction being a likely interfering factor [28]. The prevalence of FA in the general adult population is around 14.0%. A systematic review with meta-analysis demonstrated a prevalence of 32.0% in individuals in the preoperative phase of BMS (a prevalence considerably higher than that of the general adult population) and 15.0% in the postoperative phase, indicating a significant reduction after the procedure [29].

Furthermore, another possible factor that may explain the variation in UPF consumption is the culinary skills of individuals after BMS. Culinary skills are competencies related to the selection, combination, and preparation of fresh and minimally processed foods [30]. In turn, Brazilian culture is built around food traditions, in which the handling and preparation of fresh and minimally processed foods create memories and play a significant role in refining culinary practices [31]. In this regard, it is evident that the presence of culinary skills in adults can improve food choices and promote weight loss, aiding in the mitigation of non-communicable chronic diseases [32]. Considering the positive associations previously reported between culinary skills and the consumption of fresh and minimally processed foods, the presence of culinary skills in individuals undergoing BMS could contribute to adherence to dietary recommendations and guidelines for this population, thereby preventing weight regain. However, few studies explore the association of time since BMS with UPF intake, food addiction and culinary skills. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the UPF consumption, culinary skills and FA prevalence in adult individuals in different windows of time since BMS.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Aspects

The protocol for this study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Alagoas (CAAE number: 60233722.7.0000.5013). All participants were presented with the free and informed consent form on the first page of the online questionnaire. This page contained information about the research, the informed consent document, details regarding the Ethics Committee approval (including the CAAE number), as well as the contact information of the project coordinator. Consent to participate was required to access the questionnaire and begin data collection; if a participant did not wish to participate, the subsequent page displayed the following message: “Thank you! You may close this page.” No personal information was collected from the participants.

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Sample Size Calculation

For the sample size calculation, a 95% confidence level and an acceptable margin of error of 2% were assumed. Since there is no estimate of the population of patients who have undergone BMS in Brazil, the population was considered infinite. The expected frequency of FA is 15%, based on the post-BMS prevalence resulting from a systematic review with meta-analysis conducted by our research group [29]. With these settings, a total of 1224 individuals were required to form the sample.

2.4. Procedures

The survey was developed on the Google Forms® platform to serve as the primary data collection instrument. The research team compiled a questionnaire with all data of interest and transferred it to the Google Forms® platform. A pilot study was conducted with 20 individuals to prevent potential issues during questionnaire completion. This step ensured the identification and correction of any inconsistencies in the questionnaire, thereby confirming the form’s suitability for data collection. On some pages of the questionnaire, participants were required to select a specific option in order to demonstrate that they were carefully responding to the questions. The questionnaire had a total of 11 screen pages, each with a range of 6 to 10 questionnaire items. The items of the questionnaire were not randomized, and there was no conditional display to items, hence, all individuals answered all items. Respondents were able to review answers before finishing their questionnaire, with the aid of a “back” button in the form. Google Forms® compile all data answered through the link into an online spreadsheet, which only the research team had access. Due to the nature of the Google Forms® platform, we do not have access to view rates, participation rates and completion rates of the forms. The uniqueness of each respondent was verified by the email address used to fill out the form, ensuring that repeated email addresses would be considered only the last answer. Only complete questionnaires were analyzed.

2.5. Recruitment and Sample

Following the approval by the Ethics Committee and the development of the questionnaire, social media profiles on Instagram® and Facebook®, related to MBS (either from scientific societies or from health professionals that treat patients of MBS) were used to disseminate study information along with the link to the questionnaire, in a “open-survey” fashion. Participant recruitment took place from August 2022 to January 2023. Additionally, participants were encouraged to invite individuals from their social circles to take part in the study. Both male and female individuals aged between 18 and 59 years who had undergone any type of BMS were included. Pregnant women, lactating women, and those who did not complete the questionnaires in full were excluded. Answering the survey was completely voluntary and no incentives or compensations were given to the respondents.

2.6. Variables

2.6.1. Exposure

Time since bariatric and metabolic surgery: Participants were asked to provide the date of their surgical procedure, which allowed the calculation of the elapsed time between the surgery and the data collection. Participants were also queried about the specific surgical technique used. The time since surgery was categorized as follows: 0–6 months, 6–12 months, 12–48 months, and more than 48 months.

2.6.2. Outcomes

Food Consumption

To assess dietary patterns and healthy versus unhealthy eating behaviors, as recommended by the Brazilian Food Guide [31], consumption markers from the Food and Nutrition Surveillance System (SISVAN) were utilized. This instrument, which is divided into sets of questions tailored for different groups (e.g., children aged 2 or older, adolescents, adults, the elderly, and pregnant women), consists of 9 items. It evaluates the frequency of daily meals, the habit of eating while watching screens, and the consumption frequency of specific foods on the previous day. The answers for each of the markers could be “yes” or “no”. The healthy markers include the consumption of fruits, vegetables, and beans. In contrast, the unhealthy markers comprise the consumption of processed meats, sweetened beverages, instant noodles, and salty biscuits, as well as sweets, snacks, and filled cookies [35].

Ultra-Processed Food Consumption

The NOVA-UPF screener [36] was used to assess the consumption of 23 groups of UPFs on the day preceding the questionnaire. These groups were developed to include the UPF subgroups that contribute most significantly to daily energy intake, as estimated by the national food consumption survey conducted in the Family Budget Survey by the Brazilian Institute of Health and Geography in 2008–2009, along with some subdivisions of several of the original 13 subgroups. Each participant’s NOVA-UPF consumption score was calculated by summing the number of UPF subgroups reported among the 23 listed, thus ranging from 0 to 23. The 23 UPF groups listed are: margarine; sliced bread, hot dogs, or hamburgers; regular or diet sodas; sweet biscuits with or without filling; packaged snacks, potato chips, or savory biscuits; chocolate bars or bonbons; ham, salami, or bologna; sausages, hamburgers, or nuggets; fruit or chocolate-flavored yogurt; boxed or canned fruit juices (e.g., Del Valle); powdered refreshment drinks (e.g., Tang); mayonnaise, ketchup, or mustard; branded ice cream or popsicles; chocolate-flavored beverages (e.g., Nescau); frozen French fries or those from chains such as McDonald’s; instant noodles (e.g., Miojo) or packaged soups; tea-based beverages (e.g., iced tea); frozen pizza or those from chains like Pizza Hut or Domino’s; frozen lasagna or other ready-made frozen meals; ready-to-use salad dressings; packaged cakes; cereal bars; and sweetened breakfast cereals (e.g., Sucrilhos).

Culinary Skills

Culinary skills were assessed using the Cooking Skills Index (CSI) [37]. This instrument consists of ten brief, closed-ended items that evaluate the level of confidence in performing ten distinct culinary skills. These skills involve preparing home-cooked meals based on fresh and minimally processed foods, seasoned exclusively with culinary ingredients. Each item is scored on a four-point scale: (0) not confident at all, (1) slightly confident, (2) confident, and (3) very confident. The total score, which ranges from 0 to 30, is multiplied by 3.33 to convert it to a 0–100 scale, thus summarizing each participant’s culinary skills, with higher scores indicating greater culinary ability.

Food Addiction

Measured by the modified Yale Food Addiction Scale 2.0 (mYFAS 2.0) [38]. This scale was translated and cross-culturally validated for Portuguese, demonstrating adequate internal consistency and factor structure [39]. It comprises 13 items, 11 of which represent symptoms related to the individual’s eating behavior mirroring aspects of substance use disorders as defined in the DSM-5, while the remaining two items address clinical impairment/distress. Before beginning the questionnaire, participants were instructed to reflect on their relationship with hyperpalatable foods over the past twelve months. Each item was answered according to the frequency of occurrence, ranging from “never” to “every day,” with a specific threshold established for each to determine whether the symptom criteria were met. Ultimately, the 11 symptoms were summed to create a symptom count score. Participants exhibiting two or more symptoms and reaching the threshold for any of the clinical impairment/distress items were classified as having FA. Furthermore, they were categorized as either not having FA or having mild, moderate, or severe FA [38,40].

2.6.3. Additional and Adjustment Data

Social, Demographic, and Clinical Variables

Data were collected on age (in years), date of birth, education level, state, marital status, sex, race/skin color, alcohol consumption habits, smoking status, and exercise practices. Additionally, information on previous medical diagnoses of hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and depression was obtained.

Economic Class

The Brazilian Economic Classification Criteria (CCEB) was used to determine the participants’ economic class. The CCEB consists of several questions regarding asset ownership, the number of bathrooms in the residence, the number of monthly employees, the education level of the head of the household (the person who contributes the most to the family income), and access to public services such as piped water and paved streets. The scores from these questions are summed, yielding a total score ranging from 0 to 100 points, with higher scores indicating a higher estimated monthly household income. Individuals are then classified into one of six possible economic classes: “A” (45–100 points), “B1” (38–44 points), “B2” (29–37 points), “C1” (23–28 points), “C2” (17–22 points), and “D–E” (0–16) [41].

Anthropometry

Anthropometric data were self-reported, including pre-surgical weight (kg), lowest weight achieved after surgery (kg), current weight (kg), and height (m). The Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated and classified according to the World Health Organization as follows: underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 kg/m2), overweight (BMI between 25.0 and 29.9 kg/m2), and obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) [42].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

For data analysis, continuous variables are presented as mean and standard deviation, while categorical variables are expressed in frequencies. In the univariable analysis, comparisons of continuous variables across the different intervals of time since surgery were performed using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with the Tukey-HSD post hoc test. In contrast, categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. Multivariable linear models were used to assess the influence of time since surgery on the cooking skills index, the number of FA symptoms, and the NOVA-UPF score, adjusted for age, sex, BMI, economic class, and surgical technique. In order to investigate the influence of time since surgery on the categorical outcomes related to food consumption markers and FA prevalence, multivariable Poisson models were constructed—also adjusted for the same variables—to estimate prevalence ratios in different timeframes. A significance level of 5% was adopted for all analyses.

3. Results

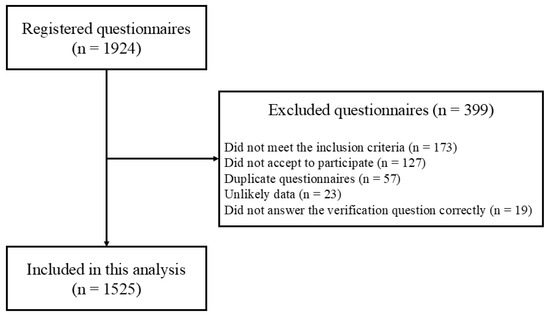

A total of 1924 questionnaires were registered on the online platform. Of these, 399 were excluded, and the participant inclusion flowchart is presented in Figure 1. Therefore, 1525 participants were included in this study.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participant inclusion.

The mean age of the sample was 38 ± 8 years, with the majority being female (n = 1458; 95.6%), and 814 (53.4%) residing in the Southeast region of the country. Regarding the surgical technique, 1206 (79.1%) underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and 319 (20.9%) underwent sleeve gastrectomy. The mean pre-surgical BMI was 42.1 ± 5.4, while the current BMI averaged 29.9 ± 5.8. In addition, the majority of the sample belonged to economic class B2 (n = 633; 41.5%). Participants had an average CSI score of 78.40 ± 19.33, and the prevalence of FA in the sample was 25.7% (n = 392). The mean time since surgery was 37 ± 54 months for the overall sample, with 452 (29.7%) individuals having undergone surgery 0–6 months ago, 275 (18.0%) 6–12 months ago, 414 (27.2%) 12–48 months ago, and 384 (25.1%) more than 48 months ago. The sample characteristics, stratified by time since surgery, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics divided by time after metabolic and bariatric surgery (n = 1525).

The CSI did not show differences according to the individuals’ time since surgery (p = 0.73). In contrast, both the prevalence and the number of symptoms of FA varied according to the individuals’ time since surgery. The prevalence of FA in individuals within the first 6 months since surgery was 41.8%, while it was lower (12.3%) in those in the period between 12 and 48 months, and intermediate in those with periods longer than 48 months since surgery (22.9%). A U-shaped pattern was observed, with the lowest FA prevalence between 24 and 48 years post-surgery and a partial increase after 4 years. A similar scenario was noted for the mean number of FA symptoms (0–6 months: 3.65 ± 3.27; 6–12 months: 2.23 ± 2.81; 12–48 months: 1.40 ± 2.30; and >48 months: 2.22 ± 2.91). The consumption of vegetables and beans did not show significant differences among the individuals with different times since surgery (p = 0.16 and p = 0.02, respectively). In contrast, the consumption of fresh fruits varied according postoperative time intervals, being higher in individuals with up to 12 months post-surgery (0–6 months: 69.2% and 6–12 months: 72.0%) and lower in individuals with more than 48 months post-surgery (12–48 months: 65.2% and >48 months: 57.3%), showing a statistically significant difference across groups (p < 0.01).

For the markers of unhealthy food consumption, the intake of processed meats (0–6 months: 10.0%; 6–12 months: 24.0%; 12–48 months: 30.0%; and >48 months: 32.0%; p < 0.01) and sweetened beverages (0–6 months: 8.6%; 6–12 months: 29.1%; 12–48 months: 36.2%; and >48 months: 40.1%; p < 0.01) showed differences across the different time-since-surgery groups, being higher in the individuals with longer time since surgery On the other hand, the consumption of instant noodles (0–6 months: 8.2%; 6–12 months: 16.4%; 12–48 months: 18.6%; and >48 months: 18.0%; p < 0.01) and savory biscuits (0–6 months: 10.8%; 6–12 months: 26.5%; 12–48 months: 42.3%; and >48 months: 36.7%; p < 0.01) also differed among groups, but with a less consistent pattern.

Table 2 presents the results of the linear regression used to associate the CSI, the number of FA symptoms, and the NOVA-UPF score with the time since BMS. It can be found that the time elapsed since surgery was not significantly associated with the participants’ cooking skills index in the univariable analysis (β: 0.04; 95% CI: −0.79, 0.87) or the multivariable analysis (β: −0.41; 95% CI: −1.33, 0.50). In contrast, FA symptoms demonstrated a significant negative association with time since surgery in both the univariable analysis (β: −0.55; 95% CI: −0.68, −0.42) and the multivariable analysis (β: −0.31; 95% CI: −0.45, −0.17). On the other hand, the consumption of UPFs, measured by the NOVA-UPF Score, showed a significant positive association with the participants’ time since surgery in both the univariable analysis (β: 0.68; 95% CI: 0.59, 0.76) and the multivariable analysis (β: 0.67; IC95%: 0.57; 0.76).

Table 2.

Linear regressions between culinary skills index, number of food addiction symptoms, and NOVA-UPF Score in relation to time (in months) after metabolic and bariatric surgery (n = 1525).

Table 3 presents the prevalence ratios obtained from the univariable and multivariable analyses for dietary consumption markers according to different categories of time since surgery. In multivariable analysis, the 12–48-month post-op group had the lowest FA prevalence (PR = 0.39 vs. the <6-month group). Those >48 months post-op showed an increase in FA (PR = 0.63), similar to the 6–12-month group, but prevalence was still significantly lower than in the immediate post-op (<6 m) group. Conversely, the consumption of UPFs showed significant differences between the categories of time since surgery. Foods such as hamburgers and/or sausages (>48 months: PR = 3.42; 95% CI: [2.44, 4.81]), sweetened beverages (>48 months: PR = 5.00; 95% CI: [3.55, 7.04]), instant noodles and snacks (12–48 months: PR = 2.46; 95% CI: [1.58, 3.84]), and sweets (12–48 months: PR = 4.01; 95% CI: [2.88, 5.57]) were significantly more consumed by those individuals with longer time since surgery. On the other hand, the intake of healthier foods such as beans was also higher in those individuals with longer time since surgery (6–12 months: PR = 1.19; 95% CI: [1.02, 1.38]; and >48 months: PR = 1.15; 95% CI: [1.00, 1.32]), although this difference was less pronounced compared to that of UPF consumption.

Table 3.

Prevalence ratio of univariable and multivariable analyses for food consumption and eating patterns markers in relation to time (in months) after metabolic and bariatric surgery.

4. Discussion

In this cross-sectional study of individuals undergoing BMS, a higher UPF consumption in those individuals with longer time since surgery was observed, with higher intakes of hamburgers and/or sausages, sweetened beverages, instant noodles, packaged snacks, and/or salty cookies; as well as sandwich cookies, sweets, and/or treats. We noted that individuals longer post-surgery consumed fewer fresh fruits. We also observed a lower number of FA symptoms and prevalence of FA in individuals up to 48 months post-surgery, while FA symptoms increased only in the group of individuals more than 48 months post-surgery. Finally, contrary to our hypothesis, no significant association was found between the Cooking Skills Index and the time since surgery, which was stable in all categories.

The observed U-shaped pattern in FA prevalence may be explained by a combination of physiological, behavioral, and psychological factors. In the first years post-surgery, metabolic changes, reduced gastric capacity, and structured clinical follow-up likely suppress addictive eating behaviors [43,44,45]. Over time, however, diminished supervision, increased availability of UPFs, and psychological vulnerabilities—such as stress, anxiety, or prior disordered eating tendencies—may contribute to a resurgence of FA symptoms [43,46]. This pattern suggests that initial protection conferred by surgery may wane, highlighting the need for long-term behavioral and nutritional support.

The consumption of UPFs after BMS has been frequently studied, but the correlates associated with it are less well-known. For instance, Farias et al. [21] observed that UPFs made up ~50% of energy intake even at 6 and 12 months post-surgery, essentially unchanged from baseline. This suggests that UPF intake remains high and does not continuously increase during the first year, aligning with our finding that the major increase happens later [21]. In contrast, Pinto et al. [19] demonstrated a reduction in UPF consumption 3 months after the surgical procedure, likely due to the direct physiological and metabolic effects of the surgery, which lead to intolerance to foods rich in carbohydrates and fats, such as UPFs, associated with dumping syndrome [47]. However, other studies reinforced that after 60 months postoperatively, there is a tendency for individuals to revert to their preoperative eating habits, particularly with respect to UPF consumption, which may ultimately lead to weight regain after 5 years post-surgery [22].

The markedly lower UPF consumption during the first 0–6 months post-surgery likely reflects strict dietary modifications in the immediate postoperative period, including liquid and pureed diets, as well as surgery-induced physiological effects such as intolerance to high-fat and high-sugar foods and dumping syndrome. Clinical guidelines recommend adopting healthy eating patterns, gradually progressing food textures, and ensuring adequate intake of protein, vitamins, and minerals. These factors likely explain why this group represents the lowest consumption in our study. As restrictions are relaxed and tolerance improves over time, UPF intake tends to rise and FA symptoms may partially return, underscoring the need for ongoing nutritional monitoring and long-term behavioral support.

Additionally, in the present study, a reduction in fruit consumption was found in the different time categories following BMS. According to Moslehi et al. (2024), the adoption of healthy eating habits is essential for achieving better outcomes after this procedure [48]. Regular consumption of foods such as fruits, vegetables, and legumes positively impacts adherence to dietary plans, promoting more effective and sustainable weight loss. Fruit consumption is also associated with higher levels of physical activity, as evidenced by Sundgot-Borgen (2024), a relevant factor in the weight loss process [49]. In this context, it is essential to assess fruit intake and its impact on weight reduction.

We also observed a significant reduction in both the symptomatology and the prevalence of FA among the participants in different time categories, which may be attributed to the metabolic effects of bariatric surgery. These effects directly impact gastric capacity and promote metabolic changes that influence dietary intake over time [50]. Furthermore, we investigated whether individuals’ culinary skills varied across the different time categories since surgery. We expected that culinary skills would increase after BMS as individuals would probably need to change their dietary habits and avoid meals outside home [51]. However, the mean CSI score of the participants in the present study indicated a medium-high culinary skills in all time categories since BMS, indicating that time since surgery was not a factor in the culinary skills of the participants.

The present study has some limitations that should be considered. The generalizability of our findings is limited. Because recruitment occurred through social media platforms, the sample likely overrepresents individuals who are younger, digitally active, and more engaged with postoperative care. Additionally, 95.6% of participants were women, and more than half resided in the Southeast region of Brazil, predominantly within economic class B2. Therefore, the results may primarily reflect the experiences of middle-income women living in more urbanized regions, and dietary behaviors may differ among men or individuals from other geographic or socioeconomic contexts. Another important limitation is that all data—including dietary intake, food addiction symptoms, culinary skills, and anthropometric measures—were self-reported through an online questionnaire. This approach is inherently susceptible to recall and reporting biases. Individuals further from surgery may underreport the consumption of UPFs due to social desirability or difficulty recalling habitual intake, whereas those in the early postoperative period—who are still under structured clinical monitoring—may report their behaviors more rigidly and accurately. Although anonymity and attention-check items were used to improve data quality, these measures cannot fully eliminate the risk. The reliance on subjective information underscores the need for future studies incorporating objective assessments, such as food records, clinical evaluations, or biochemical markers. Finally, this is a cross-sectional study and, thus, we do not have longitudinal data on the same participants, but rather we compared different individuals in different time categories since surgery, which makes it impossible to infer any causality in our findings. Therefore, the findings in this study should be interpreted with caution, and it is suggested that cohorts be conducted to evaluate the same individuals over time for the outcomes of interest at different post-surgery time points.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, time since surgery is strongly associated with both the UPF intake and prevalence of FA in adults after BMS. UPF consumption is lowest in the early postoperative period and increases over time, whereas FA shows a marked decrease up to 48 months post-surgery, followed by a partial increase after 48 months, resulting in a U-shaped pattern. In contrast, the CSI did not show an association with the time since BMS. These findings highlight the need for continuous nutritional monitoring in the postoperative period to minimize the negative impacts of these dietary changes and to prevent weight regain. Furthermore, they highlight the necessity for further research to understand the reasons behind the lack of long-term adherence to healthy eating habits.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/obesities5040085/s1, Table S1: STROBE Statement—Checklist of items that should be included in reports of cross-sectional studies; Table S2: CHERRIES—Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E.d.S.-J., M.d.L.M. and N.B.B.; methodology, A.E.d.S.-J., M.d.L.M. and N.B.B.; software, A.E.d.S.-J. and N.B.B.; validation, A.E.d.S.-J., M.d.L.M. and N.B.B.; formal analysis, A.E.d.S.-J., M.d.L.M. and N.B.B.; investigation, N.G.d.S.L., J.M.F.M. and M.C.T.F.d.S.; data curation, A.E.d.S.-J., M.d.L.M. and N.B.B.; writing—original draft preparation, N.G.d.S.L., J.M.F.M. and M.C.T.F.d.S.; writing—review and editing, A.E.d.S.-J., N.G.d.S.L., M.d.L.M. and N.B.B.; visualization, A.E.d.S.-J., M.d.L.M. and N.B.B.; supervision, A.E.d.S.-J. and N.B.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. A.E.d.S.-J. is supported by research grants from the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel—Brazil (CAPES) (process number: 88887.805029/2023-00). N.G.d.S.L. is supported by a grant from the Scientific Initiation Incentive and Scholarship Program (PIBIC-UFAL) (process number: 138294/2024-0). M.L.M. receives support from research grants from CAPES (process number: 88887.679721/2022-00). N.B.B. is funded by a research grant from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) (process number: 311401/2022-8). None of the sponsors participated in the planning, analysis, or writing of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de Alagoas (CAAE number: 60233722.7.0000.5013; date: 25 July 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request to the authors.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to the Universidade Federal de Alagoas and Laboratório de Nutrição e Metabolismo (LANUM) for providing the essential infrastructure for our work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. URL World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight Fact Sheet, 7 May 2025. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Ministry of Health. Vigitel Brazil 2023: Surveillance of Risk and Protective Factors for Chronic Diseases by Telephone Survey; Ministry of Health: Brasília, Brazil, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo, G.B.; Figueiredo, I.H.d.S.; Araujo, B.S.; Oliveira, I.M.M.; Dornelles, C.; Aguiar, J.R.V.; Ferreira, A.R.; Silva, C.V.S.; Araujo, Y.E.L.; Ribeiro, S.E.F.S.; et al. Relationship between overweight and obesity and the development or worsening of chronic non-communicable diseases in adults. Res. Soc. Dev. 2022, 11, e50311225917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goettler, A.; Grosse, A.; Sonntag, D. Productivity loss due to overweight and obesity: A systematic review of indirect costs. BMJ 2017, 7, e014632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, S.; Fusco, F.; Gray, A.; Jebb, S.A.; Cairns, B.J.; Mihaylova, B. Body mass index and healthcare costs: A systematic literature review of individual participant data studies. Obes. Rev. 2017, 7, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagi, M.A.; Ahmed, H.; Rezq, M.A.A.; Sangroongruangsri, S.; Chaikledkaew, U.; Almalki, Z.; Thavorncharoensap, M. Economic costs of obesity: A systematic review. Int. J. Obes. 2024, 48, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, D.-T.; Minh Nguyet, N.T.; Dinh, T.C.; Lien, N.V.T.; Nguyen, K.-H.; Ngoc, V.T.N.; Tao, Y.; Son, L.H.; Le, D.-H.; Nga, V.B.; et al. An update on physical health and economic consequences of overweight and obesity. Diab. Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2018, 12, 1095–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, J.; Husain, F.; Papasavas, P.; Docimo, S.; Albaugh, V.; Aylward, L.; Blalock, C.; Benson-Davies, S.; Clinical Issues Committee of the American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgeons. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery review of the body mass index. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2025, 21, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D.; Shikora, S.A.; Aarts, E.; Aminian, A.; Angrisani, L.; Cohen, R.V.; Luca, M.d.; Faria, S.L.; Goodpaster, K.P.S.; Haddad, A.; et al. 2022 American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO) Indications for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Obes. Surg. 2023, 33, 3–14, Erratum in Obes. Surg. 2023, 33, 15–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-022-06369-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordalo, L.A.; Teixeira, T.F.S.; Bressan, J.; Mourão, D.M. Bariatric surgery: How and why to supplement. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2011, 57, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghusn, W.; Zeineddine, J.; Betancourt, R.S.; Gajjar, A.; Yang, W.; Robertson, A.G.; Ghanem, O.M. Advances in Metabolic Bariatric Surgeries and Endoscopic Therapies: A Comprehensive Narrative Review of Diabetes Remission Outcomes. Medicina 2025, 61, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abi Mosleh, K.; Salameh, Y.; Ghusn, W.; Jawhar, N.; Mundi, M.S.; Collazo-Clavell, M.L.; Kendrick, M.L.; Ghanem, O.M. Impact of metabolic and bariatric surgery on weight loss and insulin requirements in type 1 and insulin-treated type 2 diabetes. Clin. Obes. 2024, 14, e12689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, P.; Docherty, N.; le Roux, C.W. Metabolic Effects of Bariatric Surgery. Clin. Chem. 2018, 64, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berino, T.N.; Reis, A.L.; Carvalhal, M.M.L.; Kikuchi, J.L.D.; Teixeira, R.C.R.; Gomes, D.L. Relationship between Eating Behavior, Quality of Life and Weight Regain in Women after Bariatric Surgery. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, E.C.; Diniz, A.S.; Monteiro, J.S.; Cabral, P.C. Dietary risk patterns for non-communicable chronic diseases and their association with body fat—A systematic review. Cien Saude Colet. 2014, 19, 1447–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juul, F.; Parekh, N.; Martinez-Steele, E.; Monteiro, C.A.; Chang, V.W. Ultra-processed food consumption among US adults from 2001 to 2018. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louzada, M.L.C.; Cruz, G.L.; Silva, K.A.A.N.; Grassi, A.G.F.; Andrade, G.C.; Rauber, F.; Levy, R.B.; Monteiro, C.A. Consumption of ultra-processed foods in Brazil: Distribution and temporal evolution 2008–2018. Rev. Saúde Públ. 2023, 57, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louzada, M.L.C.; Costa, C.D.S.; Souza, T.N.; Cruz, G.L.; Levy, R.B.; Monteiro, C.A. Impact of the consumption of ultra-processed foods on children, adolescents and adults’ health: Scope review. Cadernos Saúde Públ. 2022, 37, e00323020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, S.L.; Silva, D.C.; Bressan, J. Absolute and Relative Changes in Ultra-processed Food Consumption and Dietary Antioxidants in Severely Obese Adults 3 Months After Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. Obes. Surg. 2019, 29, 1810–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, S.L.; Juvanhol, L.L.; Bressan, J. Increase in Protein Intake After 3 Months of RYGB Is an Independent Predictor for the Remission of Obesity in the First Year of Surgery. Obes. Surg. 2019, 29, 3780–3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, G.; Silva, R.M.O.; da Silva, P.P.P.; Vilela, R.M.; Bettini, S.C.; Dâmaso, A.R.; Netto, B.D.M. Impact of dietary patterns according to NOVA food groups: 2 y after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Nutrition 2020, 74, 110746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobão, S.L.; Oliveira, A.S.; Bressan, J.; Pinto, S.L. Contribution of Ultra-Processed Foods to Weight Gain Recurrence 5 Years After Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Obes. Surg. 2024, 34, 2492–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulin, A.; Rodrigues, T.F.C.S.; Cardoso, L.C.B.; Santos, F.G.T.; Rêgo, A.d.S.; Oliveira, L.D.F.; Radovanovic, C.A.T. Changes that occurred after bariatric surgery: An integrative literature review. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e31410313329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearhardt, A.N.; Bueno, N.B.; DiFeliceantonio, A.G.; Roberto, C.A.; Jiménez-Murcia, S.; Fernandez-Aranda, F. Social, clinical, and policy implications of ultra-processed food addiction. BMJ 2023, 383, e075354, Erratum in BMJ 2023, 383, 2679. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.p2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearhardt, A.N.; Corbin, W.R.; Brownell, K.D. Development of the Yale food addiction scale version 2.0. Psychology of addictive behaviors. J. Soc. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2016, 30, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pursey, K.M.; Skinner, J.; Leary, M.; Burrows, T. The Relationship between Addictive Eating and Dietary Intake: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Júnior, A.E.D.; Gearhardt, A.N.; Bueno, N.B. Association between food addiction with ultra-processed food consumption and eating patterns in a Brazilian sample. Appetite 2023, 186, 106572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFata, E.M.; Gearhardt, A.N. Ultra-processed food addiction: An epidemic? Psychother. Psychosom. 2022, 91, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praxedes, D.R.; Silva-Júnior, A.E.; Macena, M.L.; Gearhardt, A.N.; Bueno, N.B. Prevalence of food addiction among patients undergoing metabolic/bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2023, 24, e13529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, J.A.; Nieto, J.A.; Suarez-Diéguez, T.; Silva, M. Influence of culinary skills on ultraprocessed food consumption and Mediterranean diet adherence: An integrative review. Nutrition 2024, 121, 112354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. Dietary Guidelines for the Brazilian Population; Ministry of Health: Brasília, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson, J.A.; Bleich, S.N. Is cooking at home associated with better diet quality or weight-loss intention? Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 1397–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 1500–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenbach, G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: The Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J. Med. Internet Res. 2004, 6, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. Guidelines for Evaluation of Food Consumption Markers in Primary Health Care; Ministry of Health: Brasília, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, C.S.; Faria, F.R.; Gabe, K.T.; Sattamini, I.F.; KhandpurI, N.; Leite, F.H.M.; Steele, E.M.; Louzada, M.L.d.C.; Levy, R.B.; Monteiro, C.A. Nova score for the consumption of ultra-processed foods: Description and performance evaluation in Brazil. Rev. Saude Publ. 2021, 55, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.A.; Baraldi, L.G.; Scagliusi, F.B.; Villar, B.S.; Monteiro, C.A. Cooking Skills Index: Development and reliability assessment. Rev. Nutr. 2019, 32, e180124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, E.M.; Gearhardt, A.N. Development of the Modified Yale Food Addiction Scale Version 2.0. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2017, 25, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes-Neto, P.R.; Kohler, C.A.; Schuch, F.B.; Solmi, M.; Quevedo, J.; Maes, M.; Murru, A.; Vieta, E.; McIntyre, R.S.; McElroy, S.I.; et al. Psychometric properties of the modified Yale Food Addiction Scale 2.0 in a large Brazilian sample. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2018, 40, 444–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Júnior, A.E.; Bueno, N.B. Comments on the translated version of the modified Yale Food Addiction Scale 2.0 into Brazilian Portuguese. Braz. J. Psychiatry. 2023, 45, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABEP Brazil Economic Classification Criteria. Available online: http://www.abep.org (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- WHO Expert Committee on Physical Status: The Use and Interpretation of Anthropometry (Ed.) Physical Status: The Use and Interpretation of Anthropometry: Report of a WHO Expert Committee; WHO Technical Report Series; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995; ISBN 9789241208543.

- Budny, A.; Janczy, A.; Szymanski, M.; Mika, A. Long-Term Follow-Up After Bariatric Surgery: Key to Successful Outcomes in Obesity Management. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Pérez, F.; Rojas, N.V.; Sánchez, I.; Munguía, L.; Jiménez-Murcia, S.; Artero, C.; Sobrino, L.; Lazzara, C.; Monseny, R.; Montserrat, M.; et al. Impact of preoperative food addiction on weight loss and weight regain three years after bariatric Surgery. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.M.; Goetze, R.E.; Howell, L.A.; Grothe, K.B. Psychological assessment and motivational interviewing of patients seeking bariatric and metabolic endoscopic therapies. Tech. Innov. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2020, 22, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belo, G.D.Q.M.B.; Siqueira, L.T.D.; Melo Filho, D.A.A.; Kreimer, F.; Ramos, V.P.; Ferraz, A.A.B. Predictors of poor follow-up after bariatric surgery. Rev. Col. Bras. Cir. 2018, 45, e1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpellini, E.; Arts, J.; Karamanolis, G.; Laurenius, A.; Siquini, W.; Suzuki, H.; Ukleja, A.; Beek, A.V.; Vanuytsel, T.; Bor, S.; et al. International consensus on the diagnosis and management of dumping syndrome. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2020, 16, 448–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslehi, N.; Kamali, Z.; Barzin, M.; Khalaj, A.; Mirmiran, P. Major dietary patterns and their associations with total weight loss and weight loss composition 2–4 years after sleeve gastrectomy. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundgot-Borgen, C.; Bond, D.S.; Rø, Ø.; Sniehotta, F.; Kristinsson, J.; Kvalem, I.L. Associations of adherence to physical activity and dietary recommendations with weight recurrence 1–5 years after metabolic and bariatric surgery. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2024, 20, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nora, C.; Morais, T.; Nora, M.; Coutinho, J.; Carmo, I.; Monteiro, M.P. Sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass for the treatment of metabolic syndrome. Rev. Port. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2016, 11, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marconi, S.; Covolo, L.; Marullo, M.; Zanini, B.; Viola, G.C.V.; Gelatti, U.; Maroldi, R.; Latronico, N.; Castellano, M. Cooking skills, eating habits and nutrition knowledge among Italian adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic: Sub-analysis from the online survey COALESCENT (Change amOng Italian adoLESCENTs). Nutrients 2023, 15, 4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).