Abstract

Time-restricted eating (TRE) has gained attention as an effective approach for weight management and overall well-being by focusing on limiting the eating window, rather than reducing calories. This study explores the biopsychosocial impacts of TRE in free-living individuals using a qualitative design. Twenty-one adults (aged 27–60 years) from Western Australia who had practised TRE for at least three months were purposively recruited, and semi-structured interviews were conducted. The data were analysed using a thematic analysis to identify key themes. The participants reported a range of benefits, including weight loss, reduced joint pain, better digestion, improved mental clarity, increased energy, and a more positive body image. Socially, TRE facilitated simplified daily routines but also introduced challenges, such as disruptions to social interactions and family meal dynamics. Some mixed and negative impacts were reported, including changes in sleep and exercise patterns. These findings highlight TRE’s potential as a holistic dietary intervention. Further research, particularly well-controlled, randomised controlled trials and longitudinal studies, is needed to confirm these insights and guide their appropriate application in clinical and public health settings.

1. Introduction

Conventional weight management approaches that emphasise reducing calorie intake to achieve a calorie deficit have a limited long-term efficacy, primarily due to challenges with adherence and physiological adaptation [1,2,3]. With obesity and being overweight now affecting over 2.5 billion individuals globally [4], there is an urgent need to explore innovative interventions that offer broader reach and sustained effectiveness across diverse populations. Addressing excess weight is essential, as it is linked to numerous health problems, including cardiovascular diseases, stroke, cancer, diabetes, osteoarthritis, and a reduced quality of life, placing a substantial health, economic, and social burden on individuals and society [5,6,7]. Given these widespread impacts, effective dietary interventions should not only support weight management but also contribute to broader health and well-being goals, including the physical, psychological, and social aspects of health. There is increasing recognition that dietary strategies should facilitate long-term behavioural change and have a holistic impact on health, rather than purely addressing issues of weight.

Time-restricted eating (TRE) has emerged as one such holistic strategy, gaining popularity among both the general public and scientific communities [8,9]. Unlike traditional calorie reduction, which focuses on the amount of food intake, TRE focuses on limiting the time window for food consumption [8]. Numerous studies in animals have shown its efficacy in improving metabolic health [10,11,12], and several human trials have demonstrated that TRE interventions significantly reduce weight to levels comparable with calorie restriction [13,14]. Such findings are typically achieved in TRE studies that involve a 4–10 h eating window. Additionally, even in isocaloric clinical trial settings, studies have demonstrated TRE’s benefits on weight control and on several metabolic parameters, including improved glucose control, lower blood pressure, and reduced inflammation markers [15]. These benefits are more pronounced for the early timing of TRE restriction, where the eating window starts in the morning and has an earlier closing window [16,17].

While TRE does not focus on reducing calorie intake, research has shown that participants typically achieve a reduction of their calorie intake of 200–550 calories per day, or by about 10–30% [9,18,19,20]. Therefore, several mechanisms likely contribute to the health benefits of TRE. In addition to a reduced calorie intake, which has been linked to various longevity mechanisms [21], practising TRE leads to extended fasting periods and to metabolic switching, which promotes higher fat oxidation in adipose tissue [22]. Overnight fasting also enhances autophagy, improves cellular repair processes [23], and synchronises eating occasions with circadian rhythms, resulting in improved metabolism [23,24]. These mechanisms likely contribute to overall health improvements and broader health benefits [23]. Moreover, previous studies have suggested that an 8 h TRE regimen over three months may enhance the quality of life, including improvements in physical, mental, and emotional health perception, pain, and social functioning [25]. Additionally, TRE may also offer psychological benefits, such as improved mood, increased energy, and reduced anxiety and depression [26,27,28].

Apart from its physical and psychological health impacts, TRE as a behavioural approach may also influence social interactions and the social life of those who practice it, both directly and indirectly. Fewer eating occasions and less time associated with eating may reduce decision fatigue [27] and free up time for other activities, as well as likely reducing food related costs, acting as a cost-saving measure for adherents. Additionally, potential improvements in metabolic and mental health from practicing TRE might enable greater participation in social activities and increase social inclusion.

However, TRE could also potentially lead to negative impacts on health—physical, psychological, and social. For example, TRE may impose restrictions on social activities involving eating, potentially leading to social isolation or challenges in maintaining social bonds [29,30]. The need to limit eating to specific times can disrupt participants’ social life, hindering their participation in social events outside the defined eating window [30]. Longer fasting periods might also lead to hunger, which could result in overeating during the eating window, increasing the excessive energy intake [31], and the risk of eating disorders [32].

Most research examining TRE’s impacts on individuals has heavily focused on the quantitative outcomes of metabolic parameters within controlled clinical settings. There is a significant gap in qualitative insights from real-world settings where users dynamically interact with their social environments. While the physiological benefits of TRE are increasingly documented, its broader impacts on individuals’ overall biological, psychological, and social well-being remain underexplored. Understanding these aspects through a qualitative lens is important for a comprehensive view of TRE’s implications.

This study aims to explore the biopsychosocial impacts of TRE among free-living individuals from a qualitative perspective. We focus on understanding the broader effects of TRE beyond weight control, capturing the lived experiences of individuals practising TRE. Insights from this study can inform individuals and healthcare practitioners, helping them better understand the potential benefits and challenges of TRE as an alternative dietary intervention to reduce the burden of overweight and obesity and inform future research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

We conducted a qualitative study [33] to explore the impacts of TRE on well-being among its regular users living in free-living conditions. The study was conducted in Western Australia and was part of a larger qualitative study examining the acceptability of TRE among regular TRE users within community settings. A more detailed account of the study methods has been reported elsewhere [34,35].

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

We employed purposive and snowball sampling strategies to recruit participants meeting the following criteria: (1) aged 18 years or older, (2) residing in Western Australia, and (3) practising time-restricted eating for at least three months. This duration was chosen to ensure participants had adequate experience with TRE to observe its impacts and was determined through discussions within the research team and a consultation with a consumer representative.

Recruitment channels included a Facebook group dedicated to intermittent fasting, physical flyers in public locations, and announcements on social and broadcast media and university platforms to reach a diverse population of TRE users. Additionally, some of the participants were asked to refer other individuals who met the study criteria.

2.3. Data Collection

Data collection took place from October 2022 to May 2023. The potential participants were provided with comprehensive information about the study, outlining its purpose, potential benefits, and the voluntary nature of participation. Informed consent was obtained prior to conducting semi-structured interviews designed to gather in-depth information on the participants’ experiences with TRE.

The interview guide was developed with input from experts and a consumer representative and was pilot tested with individuals with similar characteristics to the target participants. The interviews covered specific topics, including a description of a typical day for participants, the advantages and disadvantages of TRE compared to other methods they had tried, both positive and negative changes in their health, other health behaviours, and the social impacts experienced after adopting TRE. The complete set of guiding questions and the development process are detailed in a previously published paper [34], as well as in the Supplementary Materials (See Supplementary Table S1).

All the interviews were conducted by one author, a male general practitioner with experience in qualitative research. The interviews, lasting between 30 and 90 min, occurred in locations chosen by the participants for their comfort and convenience. Eighteen interviews were conducted online via video conferencing (Zoom), while three were conducted in person on university premises. Audio recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim using Otter.ai, an online transcription platform, and manually reviewed and edited to ensure their accuracy. The interviews and analyses were conducted simultaneously, and the data collection concluded when data saturation was reached, which was defined as the point at which no new themes emerged.

2.4. Data Analysis

The data analysis used an iterative thematic analysis approach based on Braun and Clarke’s six-phase process [36], with NVivo (Release 1.7.1, QSR International Pty Ltd., Burlington, MA, USA) aiding in data management. This systematic process involved data familiarisation, generating initial codes, refining codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and producing the final report. The first author conducted the initial coding, while a second author provided a secondary review, ensuring rigour and a high level of agreement on codes and themes. A broader discussion of the themes was then conducted with the other authors. An example of the coding process is provided in Supplementary Table S2.

To ensure rigour and trustworthiness, we undertook member checking by returning the transcript and excerpts of the interviews to the participants for verification and to ensure clarity. The lead researcher, a TRE user, maintained reflexivity to reduce bias by using his knowledge of TRE to enhance understanding while deliberately setting aside his own viewpoints. To enhance objectivity, co-authors who did not practise TRE contributed to the analysis, balancing the interpretations and reinforcing the study’s rigour. The research adheres to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelines [37] to ensure transparency, rigour, and comprehensive reporting (See Supplementary Table S3).

2.5. Ethical Considerations

This study received approval from the University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (project number 2021/ET000993). The participants were given a thorough explanation of the study’s purpose, process, rights, and ethical considerations prior to the interviews. Confidentiality was assured, and written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

3. Results

The study involved 21 participants, predominantly female (71%), ranging in age from 27 to 60 years (median = 48), with all but one living with family. Most participants (81%) resided in metropolitan areas, and the majority (90%) were of Caucasian ethnicity. The participants came from diverse occupational backgrounds, with 52% working full-time in professions such as healthcare, company management, or government roles, suggesting a predominantly higher socioeconomic status group. The participants practised TRE with varying eating windows, ranging from one meal a day (less than 4 h) to 8–10 h, over durations from 3 months to more than 5 years. While some of the participants did not experience weight loss from adopting TRE, most reported some degree of weight loss, with some achieving significant reductions of up to 36 kg. Those who did not experience weight loss were practising TRE for other health benefits and weight maintenance. Detailed characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics sorted by TRE type and actual eating times.

We identified several themes across three inter-related domains: (1) biological, (2) psychological, and (3) social, with some impacts overlapping multiple areas. These are described separately below, under their dominant aspects.

3.1. Biological Impacts

The majority of the participants (90%) reported several biological impacts from practising TRE, including those related to weight control and broader physical health changes:

3.1.1. Impact on Weight Control and Weight-Related Issues

Although not all the participants adopted TRE for weight loss, everyone mentioned its benefits in controlling their weight, such as maintaining it within a desirable range. The participants experienced different weight loss trajectories, with some losing weight rapidly and others more gradually. The greatest amount of weight loss achieved was 36 kg, which was maintained for over two years.

“So obviously, the weight loss has been the biggest supplier [of motivation]. it ended up being 12 kilos of loss, I genuinely didn’t expect that and as I said, this is the lightest I’ve been for easily 25 years.” (P17, M)

“I’ve been doing for about three months now. And yeah, just seeing massive change pretty quickly. And it’s actually quite easy. I’ve got it [highest weight] at 113 [kg]. And at the moment, I’m at 93 [kg].” (P11, M)

Among those who experienced weight loss, several participants reported improvements in weight-related issues, such as reduced pain in their knees and other weight-bearing joints. The participants found it difficult to determine whether this was a direct impact of adopting TRE or a result of reduced pressure on their joints due to the weight loss.

“Because just the fact of losing the amount of weight, it relieved the pressure on my knee, which feels much better. [I don’t know] if it’s the TRE’s healing property out or not, but that’s definitely better.” (P1, F)

3.1.2. Improvements in Health Problems

Some of the participants also reported improvements in various health problems, although not all the improvements were consistently experienced by all the participants. Some mentioned decreased gastric symptoms, fewer migraines, the disappearance of skin lesions, less muscle soreness, reduced joint inflammation, and lower blood pressure readings. Others reported better skin health and faster recovery from muscle injuries after sport.

“I had arthritis joint pain and took anti-inflammatories almost daily, but I don’t need them anymore. So I guess that’s reduced. I used to take medication for reflux and my reflux has also resolved. I presume it’s with the intermittent fasting.” (P5, F)

“[about the benefits]… I’d like to say that there were lots of different things to mention. I feel good. I have a history of migraines, but I don’t get them as often anymore. The mental shift has been huge; I feel like I can carry on doing this, and it’s not hard.” (P8, F)

3.1.3. Impacts on Eating Habits and Other Behaviour

Many of the participants reported various impacts related to their physical experiences with eating. Most noted reduced hunger over time as they practised TRE. Many also mentioned changes in their food preferences, with some favouring vegetables and less sugary food. However, another participant mentioned no changes in her food choices, still allowing herself to eat anything. Several participants noted a better relationship with food, describing this as “appetite correction”, where their appetite became more regulated, and they no longer ate emotionally. Others mentioned enhanced taste perception, allowing them to enjoy certain foods more.

“I don’t want all the big heavy foods anymore. I want nice, clean foods, and I appreciate the flavors, ... I can now distinguish the herbs and spices in those meals. And I can appreciate the different flavors across each vegetable.. I would eat a carrot now. I noticed previously I might think it was savory. But now I find it tastes sweet. Now I can taste that difference.” (P11, M)

“My taste buds have changed over the three years. I also want to eat different foods, I now enjoy foods like eggplant, artichokes, sauerkraut, kimchi, that fermented foods that I never thought I would ever touch.” (P16, F)

“I guess I allow myself to get away with bad food choices more easily. Because I think I’m not going to put weight on because I won’t eat dinner.” (P15, F)

The participants had different experiences with exercise and sleep. Some found that they could exercise more as they had more energy and their bodies were leaner, making it easier to exercise. Others reduced their exercise as they had already achieved their weight goals but enjoyed it more when they did. Similarly, sleep experiences varied, with some reporting longer sleep durations, while others experienced shorter sleep durations, although generally, they perceived no problems with their sleep.

“I no longer overeat, and I wake up feeling refreshed, not sluggish, without needing a meal immediately.. I wake up feeling better and I feel like I’ve had a good night’s rest.” (P12, F)

“I think I might need less sleep than before, maybe just an hour. I used to need about nine hours, but now I’m fine on seven [hours].” (P1, F)

3.2. Psychological Impacts

This domain was the dominant aspect mentioned by almost all the participants (95%) regarding their experience with TRE.

3.2.1. Improved Mood, Energy, and Mental Clarity

Most reported positive changes in their mental health, including enhanced focus and clarity, better mood, and more energy. For some participants, who were creative workers, such as artists or musicians, this improvement in focus was particularly highly valued. Increased energy levels also allowed them to carry out more activities, in turn boosting their emotional well-being.

“The benefits to me have been being broad. Mentally I’m much sharper, because I’m not constantly processing calories. I feel far less sluggish. I no longer snooze my alarm—I get up and get on with the day.” (P17, M)

“I’m also a dancer and and have been teaching dance for 20 years. And now I can do a workshop or I can teach a workshop and then perform at night. I have so much more energy and I enjoy it so much more. And I can move stronger.” (P4, F)

3.2.2. Reduced Stress and Increased Self-Confidence

Some participants also mentioned reduced daily stress, particularly related to constant meal planning and decision making about what to eat. Moreover, as many of the participants had practised TRE for an extended period, they felt a sense of empowerment as they had finally found something they could sustain, giving them control over their lives and boosting their self-confidence.

“It’s the feeling of being in control of my weight for the first time in my life. It’s easy—I don’t have to think about it much. I’m eating much better food and don’t have to worry about calories, macros, and all of that. Also, not having to think about what I’m going to eat for breakfast, lunch, or dinner, or how many calories… it’s freeing.” (P4, F)

While most of the participants lost weight and had a leaner body, many reported a positive mental boost. They were excited by the consequences, such as being able to wear clothes they had not fit into for a long time, which led to increased confidence and comfort with their bodies.

“I’m happier, because I feel like I look better when I look in the mirror. I fit back into clothes I didn’t fit into for a long time. So it feels really nice to put that outfit on and to feel good in it. So, because I have more confidence, but most of that is around the weight loss.” (P15, F)

3.3. Social Impacts

While all the participants recognised the need to modify their daily routines to fit TRE, around two-thirds noted significant social effects, both positive and negative. These impacts related to their daily schedules and social interactions with family, friends, and in the workplace.

3.3.1. Positive Social Impacts

On the positive side, transitioning from eating at least three times spread throughout the day to a more structured eating schedule (typically involving two meals per day) was generally regarded as positive by many. They no longer had to constantly think about eating and could focus more on important tasks, such as work or other activities.

“I’ve saved myself time every morning. That was a part of the appeal. And it’s just the feeling of lightness as well. Your body feels lighter.” (P14, M)

3.3.2. Challenges in Social Interaction

On the negative side, having a defined and shorter eating window disrupted some of the participants’ social habits. Some reported attending fewer social events, occasionally feeling isolated during their fasting periods, facing difficulties when social events conflicted with their fasting windows, and experiencing awkwardness when attending events without eating while others did. However, most mentioned that these issues were generally manageable. All the participants carefully selected their eating window to be convenient and aligned with their schedules and social needs. Many chose a late eating window to accommodate social occasions that often occurred in the evening. They coped with socialisation issues by slightly loosening their eating window or practising flexibility. This was particularly common on weekends and holidays, when more frequent eating occasions were expected.

“If we’re going out to dinner with friends, I just eat everything that I want. I don’t restrict myself. So it hasn’t affected my social life in that way. ... I go ahead and enjoy whatever is there, because it doesn’t have to happen all the time. So if it’s an occasional thing, it’s not a problem.” (P6, F)

“The only thing maybe is socially when I travel with colleagues and they go for breakfast. Sometimes I’ll just go anywhere and have a glass of water. It’s a weird feeling. But I feel better [if I don’t eat breakfast].” (P20, M)

However, within the context of family dynamics, these issues posed greater challenges, particularly for the female participants who were accustomed to cooking for their families. They often needed to manage different eating windows by sitting together during meals and drinking non-caloric beverages. In line with this, some of the participants mentioned that practising TRE was much easier when their family members were away from home. One participant, who lived alone, also acknowledged that it might have been more difficult to practise TRE if he still lived with his family.

“I used to cook my family an amazing meal, and then sitting down and having water. And then I would get it as leftovers the next day. It does get a little bit challenging.” (P4, F)

3.4. Additional Factors Influencing Impacts

While most of the participants attributed many benefits to TRE, some acknowledged that other factors and behaviour changes also contributed to their experiences after adopting TRE. Since TRE was usually not the only lifestyle change they made, some mentioned that many of the outcomes might also have been influenced by other factors, such as exercise, medication, and changing food choices. Nevertheless, they suggested that these behaviours are probably inter-related. Some of the participants mentioned it was difficult to attribute many health impacts solely to TRE, but TRE likely facilitated other positive behavioural changes that improved their overall well-being.

“I’m still on HRT. So I have to consider that as well. But I feel like my mood is very stable now. I don’t get my hot flushes. My weight is good. My hairIoss stopped. So I can’t really be sure if it’s because of my HRT treatment or if it’s because of the TRE.” (P7, F)

“Well, it’s kind of hard to tell because there have been other factors over the past five years. For example, I’ve been going to the gym, which has been very positive as well.” (P14, M)

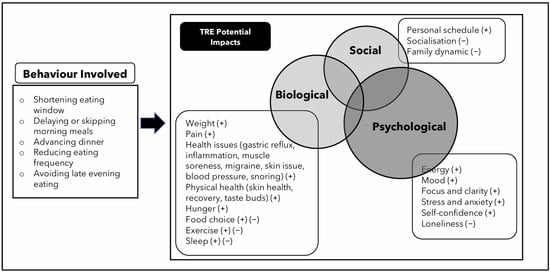

In summary, Figure 1 illustrates the biopsychosocial model of TRE impacts, detailing the behavioural changes involved in TRE practice and their potential impacts across the biological, psychological, and social dimensions identified from participants in this study.

Figure 1.

Behavioural Changes during TRE and their potential biopsychosocial impacts. A plus (+) sign indicates favourable impacts or improvements (e.g., weight reduction, decreased pain, increased energy). A minus (−) sign represents unfavourable impacts (e.g., social disruptions within the family, reduced socialisation). A plus/minus (+/−) sign denotes mixed impacts, meaning the participants reported both positive and negative effects, depending on individual experiences.

4. Discussion

This study provides insights into the potential biopsychosocial impacts of TRE among regular users in real-world settings. Most of the participants in our study experienced weight loss, which made it challenging to separate the benefits of weight loss from those of TRE itself. While some of the reported impacts align with previous studies, new insights also emerged. Interestingly, the psychological and social benefits appeared equally important as the biological impacts for those practising TRE.

Consistent with many randomised controlled trials (RCTs) [15,26,38], systematic reviews [16,39,40], and a real-world study [41], the participants in our study reported significant weight loss and improved weight management through the use of TRE. The participants also noted improvements in weight-related issues, such as reduced joint pain, which aligns with studies linking higher weight to increased pressure on weight-bearing joints [42]. Non-weight-related impacts, such as decreased gastric reflux, fewer migraines, and reduced inflammation, have been less frequently emphasised in trial settings but reported in our study, highlighting the need for further investigation into TRE’s broader health benefits. However, the effectiveness of TRE may vary across populations, with some studies reporting limited or inconsistent benefits in certain groups [43]. For example, some trials have found no or modest differences in weight loss between TRE and standard dietary approaches, particularly when the overall caloric intake is not actively restricted [13,43]. Additionally, individual differences in metabolic responses and lifestyle factors may influence the extent to which TRE is effective across diverse populations [44].

The participants using TRE reported a shift towards more mindful, intuitive, and generally healthier eating habits, along with mixed effects on exercise frequency, physical activity levels, and sleep duration. These findings are consistent with a recent survey showing that individuals practising intermittent fasting or TRE often adopt healthier lifestyles and social behaviours [45]. However, another study reported that the effects of TRE on mood, activity, physical activity, and sleep were still inconclusive [46], highlighting the need for further high-quality research. Additionally, several of the participants in our study made other behavioural changes, such as improving their dietary choices and increasing physical activity, which likely contributed to the enhanced health impacts they experienced. This aligns with studies exploring the combination of TRE with other approaches, such as the DASH diet [47] and resistance training [48], which have shown positive synergistic effects. These findings suggest that integrating TRE with other health behaviours is both feasible and potentially beneficial.

The psychological benefits mentioned by our participants, including enhanced focus, mental clarity, better mood, and increased energy, align with previous studies [20,27]. Swiatkewitz et al. reported that a 12-week, 10 h TRE positively improved mental health by improving sleepiness scores and reducing depression [49]. However, our study uniquely identified a sense of empowerment and self-control among TRE users, which seemed to boost their confidence and contribute to better overall psychological well-being—an area less frequently discussed in the existing literature. Simplifying eating structures through TRE may also reduce the cognitive load and stress associated with constant meal planning and decision making. A systematic review by Sones et al. reported that TRE did not negatively affect the quality of life and may improve physical and mental health, especially after three months of adoption, which aligns with our findings [50].

Socially, our participants reported mixed experiences. While some found TRE disrupted their socialising, many others did not consider it a significant issue. Most adapted their daily routines to align with their eating windows, confirming Bjerre et al.’s findings that TRE requires adjustments to daily structures and social interactions [51,52]. In our study, some of the participants felt awkward when avoiding eating during social gatherings, but these issues were generally manageable. However, the impact of TRE on social life may vary depending on cultural norms and family expectations regarding shared meals. In cultures where communal eating plays a central role, deviating from traditional meal patterns may create additional social pressures [53,54], potentially influencing adherence [35]. Difficulty coping with these situations could disrupt TRE adherence and negatively impact social interactions.

While TRE facilitated positive individual routines, it may have had a negative impact on family dynamics. The participants practising TRE alone, while their family members followed different eating patterns, experienced disruptions in shared meal times, potentially affecting family cohesion [55]. Social challenges were particularly noted during events that did not align with the participants’ eating windows. These findings are consistent with previous studies indicating that TRE can be socially restrictive [29,52]. Applying flexibility to accommodate social events was essential for long-term TRE adherence [35], with many of the participants opting for later eating windows so as to maintain shared meal times.

In summary, our study broadens the understanding of how TRE affects individuals beyond controlled environments. We argue that a holistic, biopsychosocial approach [56] more accurately captures these impacts, highlighting the interplay of TRE’s diverse effects on health. However, it remains challenging to determine whether these benefits are solely due to TRE or influenced by other factors or associated behavioural changes. For instance, since a lower BMI is linked to a better quality of life [6,7], isolating TRE’s unique benefits, as opposed to the impacts of weight loss or other behavioural change, is challenging. Some mental health and sleep improvements may stem from weight loss, but TRE’s structured eating patterns and extended fasting likely also play a role. Fasting in TRE may uniquely enhance bodily functions, such as reducing inflammation, boosting cognition, and supporting muscle endurance, potentially through lowered insulin and leptin levels and reduced oxidative stress [23]. Additionally, TRE’s alignment with circadian rhythms optimises metabolic processes, reduces insulin stimulation, and supports cellular repair [57]. Notably, previous studies have shown that benefits like reduced blood pressure and improved insulin sensitivity can occur with TRE, even without weight loss [15].

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

This study adds to the limited evidence exploring the experiences and perspectives of individuals engaging in TRE in community settings, focusing on its impacts on biological, psychological, and social dimensions. By examining TRE outside of controlled trial settings, this study offers a deeper understanding of its real-world practices and challenges. The inclusion of a diverse sample in terms of age, gender, and social background strengthens the study. The qualitative methodology uncovers previously underexplored impacts of TRE, such as improvements in multiple health issues, mental well-being, and social interactions.

This study’s limitations include its reliance on self-reported data and the recruitment of participants who had maintained TRE for at least three months, which favoured highly motivated and successful TRE practitioners. Our recruitment via social media platforms may have drawn participants who were already interested in TRE and active online, potentially limiting the diversity of perspectives. While the sample was diverse, it lacked representation in some age groups, particularly from individuals aged 30–40 years, who may experience specific challenges with TRE due to child-rearing responsibilities and family mealtime commitments, as well as from those over 60 years old, an age group where reduced work demands might heighten the feelings of loneliness or boredom if using TRE alone. These gaps may limit the generalisability of the findings regarding TRE’s social impacts across different life stages. Future research should explore how cultural differences and family dynamics shape the social feasibility of practising TRE across diverse populations.

Another limitation is the difficulty in distinguishing the TRE-specific effects from potential confounders, such as changes in physical activity, dietary habits, and medication use. Additionally, baseline BMI values were not collected, limiting the ability to contextualise weight changes. The qualitative nature of this study highlights the need for complementary objective assessments of TRE’s effects. Nevertheless, this study significantly advances our understanding of TRE’s biopsychosocial impacts, highlighting key areas for further research and offering practical insights for healthcare providers and public health initiatives.

4.2. Implication of the Findings

Future research should employ well-controlled RCTs and other rigorous designs to comprehensively explore the broader biopsychosocial effects of TRE, rather than focusing on isolated outcomes. Follow-up quantitative research is also needed to validate the themes identified in this qualitative study. Comparing different TRE protocols could help determine the optimal eating windows for specific health outcomes. Studies involving larger and more diverse populations, including older adults and socially disadvantaged groups, are necessary to support the generalisability of these findings. Longitudinal studies are essential to understand the long-term effects of TRE on biopsychosocial health. Furthermore, while the positive impacts are well documented, the frequency and context of negative impacts, particularly among individuals who discontinue TRE, warrant further investigation.

Healthcare providers and public health initiatives may consider incorporating TRE as a weight management strategy, emphasising its biopsychosocial benefits. For instance, healthcare providers could offer tailored guidance to help individuals select eating windows that accommodate their social and family needs, thereby improving adherence. Additionally, integrating TRE with other health-promoting interventions, such as healthy dietary choices or physical activity programs, could further enhance well-being outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This research lays the groundwork for further investigation into TRE’s potential impacts. While TRE appears to be a viable option for improving health and well-being, the intertwined nature of the observed impacts and other factors complicates attributing the benefits solely to TRE. Further studies with robust designs, including longitudinal studies and trials in diverse populations, are needed to examine causal relationships and fully understand TRE’s potential as a comprehensive lifestyle intervention that could mitigate the health and social burden of being overweight or obese. Healthcare providers should consider TRE’s balanced biopsychosocial impacts when recommending it and offer personalised support to individuals adopting this dietary approach.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/obesities5010010/s1, Table S1: Complete interview guiding questions. Table S2: example of coding process. Table S3: COREQ Checklist for manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, H.S.R., N.M., J.M.K. and S.C.T.; methodology, H.S.R., N.M., J.M.K. and S.C.T.; formal analysis, H.S.R. and N.M.; data curation, H.S.R.; writing—original draft preparation, H.S.R.; writing—review and editing, H.S.R., N.M., J.M.K. and S.C.T.; visualisation, H.S.R.; supervision, N.M., J.M.K. and S.C.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP), Ministry of Finance, Republic of Indonesia, through a doctoral scholarship awarded to HSR (No. 20200522651796).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (project number: 2021/ET000993) on 14 March 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to the participants being guaranteed confidentiality.

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere gratitude to Graeme Currie for his support as our research buddy through the Consumer and Community Involvement program organised by the WA Health Translation Network. We are grateful for his contributions to the development of the interview guide and participant recruitment. We also thank Tanya Dale (WACRH dietitian) for her assistance reaching a diverse range of participants for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COREQ | Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research |

| RCT | randomised controlled trial |

| TRE | time-restricted eating |

References

- Hall, K.D.; Kahan, S. Maintenance of Lost Weight and Long-Term Management of Obesity. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 102, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumithran, P.; Prendergast, L.A.; Delbridge, E.; Purcell, K.; Shulkes, A.; Kriketos, A.; Proietto, J. Long-term persistence of hormonal adaptations to weight loss. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 1597–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solbrig, L.; Jones, R.; Kavanagh, D.; May, J.; Parkin, T.; Andrade, J. People trying to lose weight dislike calorie counting apps and want motivational support to help them achieve their goals. Internet Interv. 2017, 7, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Obesity and Overweight. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Das, M.; Webster, N.J.G. Obesity, cancer risk, and time-restricted eating. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2022, 41, 697–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, J.; Smith, C.M.; Kearns, B.; Haywood, A.; Bissell, P. The association between obesity and quality of life: A retrospective analysis of a large-scale population-based cohort study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul-Haq, Z.; Mackay, D.F.; Fenwick, E.; Pell, J.P. Meta-analysis of the association between body mass index and health-related quality of life among adults, assessed by the SF-36. Obesity 2013, 21, E322–E327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, E.B.; Devlin, B.L.; Hawley, J.A. Perspective: Time-Restricted Eating—Integrating the What with the When. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 699–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezpeleta, M.; Cienfuegos, S.; Lin, S.; Pavlou, V.; Gabel, K.; Tussing-Humphreys, L.; Varady, K.A. Time-restricted eating: Watching the clock to treat obesity. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatori, M.; Vollmers, C.; Zarrinpar, A.; DiTacchio, L.; Bushong, E.A.; Gill, S.; Leblanc, M.; Chaix, A.; Joens, M.; Fitzpatrick, J.A.J.; et al. Time-restricted feeding without reducing caloric intake prevents metabolic diseases in mice fed a high-fat diet. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 848–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M.K.; Choi, M.H.; Kulseng, B.; Zhao, C.M.; Chen, D. Time-restricted feeding on weekdays restricts weight gain: A study using rat models of high-fat diet-induced obesity. Physiol. Behav. 2017, 173, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaix, A.; Zarrinpar, A.; Miu, P.; Panda, S. Time-restricted feeding is a preventative and therapeutic intervention against diverse nutritional challenges. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 991–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Huang, Y.; Huang, C.; Yang, S.; Wei, X.; Zhang, P.; Guo, D.; Lin, J.; Xu, B.; Li, C.; et al. Calorie Restriction with or without Time-Restricted Eating in Weight Loss. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1495–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Liu, X.; Bao, L.; Yang, P.; Zhou, H. Health effects of the time-restricted eating in adults with obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1079250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutton, E.F.; Beyl, R.; Early, K.S.; Cefalu, W.T.; Ravussin, E.; Peterson, C.M. Early Time-Restricted Feeding Improves Insulin Sensitivity, Blood Pressure, and Oxidative Stress Even without Weight Loss in Men with Prediabetes. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 1212–1221.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yi, P.; Liu, F. The Effect of Early Time-Restricted Eating vs Later Time-Restricted Eating on Weight Loss and Metabolic Health. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 108, 1824–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, B.; Marín, A.; Burrows, R.; Sepúlveda, A.; Chamorro, R. It’s About Timing: Contrasting the Metabolic Effects of Early vs. Late Time-Restricted Eating in Humans. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2024, 13, 214–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varady, K.A.; Cienfuegos, S.; Ezpeleta, M.; Gabel, K. Clinical application of intermittent fasting for weight loss: Progress and future directions. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2022, 18, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabel, K.; Cienfuegos, S.; Kalam, F.; Ezpeleta, M.; Varady, K.A. Time-Restricted Eating to Improve Cardiovascular Health. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2021, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni, R.; Robertson, T.M.; Robertson, M.D.; Johnston, J.D. A pilot feasibility study exploring the effects of a moderate time-restricted feeding intervention on energy intake, adiposity and metabolic physiology in free-living human subjects. J. Nutr. Sci. 2018, 7, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Most, J.; Tosti, V.; Redman, L.M.; Fontana, L. Calorie restriction in humans: An update. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 39, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano, C.; González-Alvarado, E.; Salmerón, D.; Ruiz-Ojeda, F.J.; Luján, J.; Scheer, F.A.J.L.; Garaulet, M. Time-restricted eating affects human adipose tissue fat mobilization. Obesity 2024, 32, 1680–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anton, S.D.; Moehl, K.; Donahoo, W.T.; Marosi, K.; Lee, S.A.; Mainous, A.G.; Leeuwenburgh, C.; Mattson, M.P. Flipping the Metabolic Switch: Understanding and Applying the Health Benefits of Fasting. Obesity 2018, 26, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Liao, Y.; Deng, Y.; Shuang, R. Unraveling the Health Benefits and Mechanisms of Time-Restricted Feeding: Beyond Caloric Restriction. Nutr. Rev. 2024, 83, e1209–e1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anic, K.; Schmidt, M.W.; Furtado, L.; Weidenbach, L.; Battista, M.J.; Schmidt, M.; Schwab, R.; Brenner, W.; Ruckes, C.; Lotz, J.; et al. Intermittent Fasting—Short-and Long-Term Quality of Life, Fatigue, and Safety in Healthy Volunteers: A Prospective, Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, S.; Panda, S. A smartphone app reveals erratic diurnal eating patterns in humans that can be modulated for health benefits. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, F.L.; Jamshed, H.; Bryan, D.R.; Richman, J.S.; Warriner, A.H.; Hanick, C.J.; Martin, C.K.; Salvy, S.J.; Peterson, C.M. Early time-restricted eating affects weight, metabolic health, mood, and sleep in adherent completers: A secondary analysis. Obesity 2023, 31, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Rodríguez, R.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; Mesas, A.E.; Notario-Pacheco, B.; Medrano, M.; Heilbronn, L.K. Does intermittent fasting impact mental disorders? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 63, 11169–11184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’connor, S.G.; Boyd, P.; Bailey, C.P.; Nebeling, L.; Reedy, J.; Czajkowski, S.M.; Shams-White, M.M. A qualitative exploration of facilitators and barriers of adherence to time-restricted eating. Appetite 2022, 178, 106266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerre, N.; Holm, L.; Veje, N.; Quist, J.S.; Færch, K.; Hempler, N.F. What happens after a weight loss intervention? A qualitative study of drivers and challenges of maintaining time-restricted eating among people with overweight at high risk of type 2 diabetes. Appetite 2022, 174, 106034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unlu, Y.; Piaggi, P.; Stinson, E.J.; Cabeza De Baca, T.; Rodzevik, T.L.; Walter, M.; Krakoff, J.; Chang, D.C. Impaired metabolic flexibility to fasting is associated with increased ad libitum energy intake in healthy adults. Obesity 2024, 32, 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuccolo, K.; Kramer, R.; Petros, T.; Thoennes, M. Intermittent fasting implementation and association with eating disorder symptomatology. Eat. Disord. 2021, 30, 471–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldana, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Mthods Sourcebook, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 9781452257877. [Google Scholar]

- Rathomi, H.S.; Mavaddat, N.; Katzenellenbogen, J.M.; Thompson, S.C. “It just made sense to me!” A Qualitative Exploration of Individual Motivation for Time-Restricted Eating. Appetite 2025, 204, 107751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathomi, H.S.; Mavaddat, N.; Katzenellenbogen, J.M.; Thompson, S.C. Navigating challenges and adherence in time-restricted eating: A qualitative study. Nutr. Diet. 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cienfuegos, S.; Gabel, K.; Kalam, F.; Ezpeleta, M.; Wiseman, E.; Pavlou, V.; Lin, S.; Oliveira, M.L.; Varady, K.A. Effects of 4-and 6-h Time-Restricted Feeding on Weight and Cardiometabolic Health: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Adults with Obesity. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 366–378.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Kang, J.; Kim, S.H.; Chung, H.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Yu, J.M.; Cho, S.T.; Oh, C.-M.; Kim, T. Beneficial Effects of Time-Restricted Eating on Metabolic Diseases: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Du, T.; Zhuang, X.; Ma, G. Time-restricted eating improves health because of energy deficit and circadian rhythm: A systematic review and meta-analysis. iScience 2024, 27, 109000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathomi, H.S.; Katzenellenbogen, J.; Mavaddat, N.; Woods, K.; Thompson, S.C. Time-Restricted Eating in Real-World Healthcare Settings: Utilisation and Short-Term Outcomes Evaluation. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, I.N.; Osborne, R.H. Obesity and increased burden of hip and knee joint disease in Australia: Results from a national survey. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2012, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhou, K.; Shang, Z.; Bao, D.; Zhou, J. The Effects of Time-Restricted Eating on Fat Loss in Adults with Overweight and Obese Depend upon the Eating Window and Intervention Strategies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Cienfuegos, S.; Ezpeleta, M.; Gabel, K.; Pavlou, V.; Mulas, A.; Chakos, K.; McStay, M.; Wu, J.; Tussing-Humphreys, L.; et al. Time-Restricted Eating Without Calorie Counting for Weight Loss in a Racially Diverse Population. Ann. Intern. Med. 2023, 176, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandri, E.; Borghesi, D.; Cantín Larumbe, E.; Cerdá Olmedo, G.; Vega-Bello, M.J.; Bernalte Martí, V. Intermittent Fasting: Socio-Economic Profile of Spanish Citizens Who Practice It and the Influence of This Dietary Pattern on the Health and Lifestyle Habits of the Population. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamshed, H.; Steger, F.L.; Bryan, D.R.; Richman, J.S.; Warriner, A.H.; Hanick, C.J.; Martin, C.K.; Salvy, S.J.; Peterson, C.M. Effectiveness of Early Time-Restricted Eating for Weight Loss, Fat Loss, and Cardiometabolic Health in Adults with Obesity: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2022, 182, 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Lin, X.; Yu, J.; Yang, Y.; Muzammel, H.; Amissi, S.; Schini-Kerth, V.B.; Lei, X.; Jose, P.A.; Yang, J.; et al. Effects of DASH diet with or without time-restricted eating in the management of stage 1 primary hypertension: A randomized controlled trial. Nutr. J. 2024, 23, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, T.; Tinsley, G.; Pacelli, F.Q.; Marcolin, G.; Bianco, A.; Paoli, A. Twelve Months of Time-restricted Eating and Resistance Training Improves Inflammatory Markers and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors. Randomized Control. Trial 2021, 53, 2577–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świątkiewicz, I.; Nuszkiewicz, J.; Wróblewska, J.; Nartowicz, M.; Sokołowski, K.; Sutkowy, P.; Rajewski, P.; Buczkowski, K.; Chudzińska, M.; Manoogian, E.N.C.; et al. Feasibility and Cardiometabolic Effects of Time-Restricted Eating in Patients with Metabolic Syndrome. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sones, B.E.; Devlin, B.L. The impact of time-restricted eating on health-related quality of life: A systematic literature review. Nutr. Rev. 2024, 83, 230–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerre, N.; Holm, L.; Quist, J.S.; Færch, K.; Hempler, N.F. Is time-restricted eating a robust eating regimen during periods of disruptions in daily life? A qualitative study of perspectives of people with overweight during COVID-19. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerre, N.; Holm, L.; Quist, J.S.; Færch, K.; Hempler, N.F. Watching, keeping and squeezing time to lose weight: Implications of time-restricted eating in daily life. Appetite 2021, 161, 105138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, G.; Golley, R.; Patterson, K.; Le Moal, F.; Coveney, J. What can families gain from the family meal? A mixed-papers systematic review. Appetite 2020, 153, 104725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utter, J.; Larson, N.; Berge, J.M.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Fulkerson, J.A.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Family meals among parents: Associations with nutritional, social and emotional wellbeing. Prev. Med. 2018, 113, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiese, B.H.; Schwartz, M. Reclaiming the Family Table: Mealtimes and Child Health and Wellbeing. Soc. Policy Rep. 2008, 22, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G.L. The Need for a New Medical Model: A Challenge for Biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahluwalia, M.K. Chrononutrition—When We Eat Is of the Essence in Tackling Obesity. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).