Abstract

In northwestern Ecuador, where more than 90% of the original forest cover has been lost, it is unknown how soil chemistry influences bat diversity. This study evaluated bat diversity, non-herbaceous plant community structure, and soil nutrients in 30 plots distributed across crops on two farms separated by 32 km. Soil analyses revealed variations in organic matter and nutrients, identifying calcium, magnesium, zinc and iron as the most influential. A total of 1662 individuals of 24 non-herbaceous plant species and 193 individuals of 16 bat species were recorded, dominated by frugivorous and nectarivorous guilds. Generalized linear mixed models showed significant relationships between bat diversity indices and soil nutrients. These elements improve tree growth, fruiting, and flowering, which increases the quality and availability of food resources for bats. In return, these mammals provide key ecosystem services such as pollination, seed dispersal, and insect control. Our findings highlight that soil chemistry indirectly regulates bat communities by influencing vegetation structure and resource availability. This integrated approach underscores the importance of soil–plant–animal interactions in tropical agricultural landscapes, offering practical guidance.

1. Introduction

The north-western region of Ecuador is the most affected by agricultural activities; currently, more than 90% of the original forest cover has been destroyed and displaced by agricultural land use, thereby impacting biodiversity. The annual deforestation rate increases significantly each year [1]. Agricultural expansion and commercial logging have driven profound land-use changes in this region, resulting in severe forest-cover reduction, fragmentation, and the transformation of continuous forests into heterogeneous agricultural mosaics [2]. These processes have fundamentally altered ecosystem structure and function, creating landscapes dominated by productive land uses interspersed with remnant forest patches and secondary vegetation. Considering the above, it is necessary to understand the reasons why some animal species have been able to survive under these conditions.

Bats constitute a particularly informative taxonomic group for evaluating ecological responses to landscape modification. In the Neotropics, bats exhibit high mobility, pronounced functional diversity, and a strong dependence on vegetation structure and plant-derived resources [3]. The Phyllostomidae family represents one of the most diverse radiations of mammals in tropical ecosystems and encompasses multiple trophic guilds, including frugivores, nectarivorous, insectivorous, carnivorous, and omnivorous, which respond differently to disturbance and landscape complexity gradients [4,5]. These characteristics make phyllostomid bats widely recognised bioindicators of habitat quality and ecosystem functioning. Bats also play a key role in maintaining ecosystem processes such as seed dispersal, pollination and biological control of insect populations, thus contributing directly to forest regeneration, ecosystem resilience and the maintenance of ecological processes in fragmented landscapes [6,7,8]. In agricultural environments, these services are particularly important, as bats improve functional connectivity between forest remnants and productive matrices, promoting biodiversity and ecosystem functioning in human-modified systems [9].

Previous studies that assessed biodiversity in disturbed landscapes have found positive and significant relationships between faunal diversity and climatic variables, landscape fragmentation and plant diversity [10,11,12]. Within this context of rapid land-use change, the conversion of forests into mosaics of croplands, pastures, secondary vegetation, and remnant forest patches alters habitat connectivity, vegetation structure, and resource availability, thereby shaping biodiversity persistence and ecosystem functioning [12,13]. Research conducted in agroforestry and mixed agricultural systems further demonstrates that landscape configuration and habitat heterogeneity strongly influence community composition, even in matrices dominated by productive land uses [14]. However, the majority of authors have focused their efforts on evaluating the various responses exhibited by bats to vegetation and landscape characteristics, overlooking the soil–plant–animal relationships that are relevant to maintaining ecosystem balance [9,10,14]. Therefore, studies that explicitly integrate soil chemical composition with non-herbaceous plant diversity and bat communities in tropical agricultural landscapes remain scarce.

Based on the knowledge that soil chemical composition plays a fundamental role in regulating plant productivity, community structure, and the nutritional quality of plant-derived resources [15,16], our study hypothesizes that variations in soil nutrients may indirectly influence the richness and diversity of bat communities by shaping the structure of non-herbaceous plant communities, generating knock-on effects on food availability and bat habitat quality. To evaluate the hypothesis, the following objective was formulated: To determine how bat diversity is related to non-herbaceous plant diversity and soil nutrient composition in agricultural landscapes in the Ecuadorian tropics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

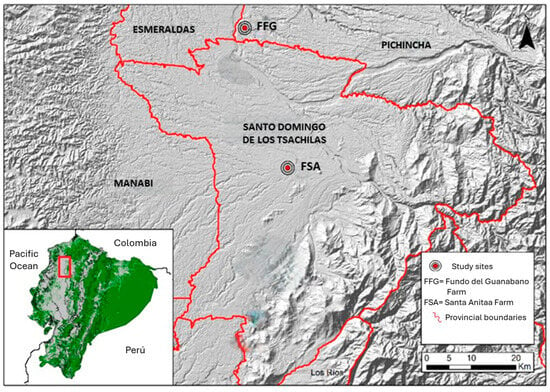

The study was conducted in two farms located in northwestern Ecuador: (a) the Fundo del Guanábano farm (FFG), located in the province of Pichincha, canton of Puerto Quito, parish of Nuevo Triunfo, 165 km from the Quito-La Independencia highway, 0°3′59″ N; 79°15′04″ W; 350 and 410 m above sea level, (b) the Santa Anita farm (FSA) in the province of Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas, Santo Domingo canton, 6.5 km from the Santo Domingo-Chone highway, 0°13′18″ S; 79°13′21″ W; 560 m above sea level (Figure 1). The two locations evaluated are 32.14 km apart, both belong to the life zone known as tropical rainforest [17].

Figure 1.

Location of the two farms, in north-western Ecuador, where soil chemicals, non-herbaceous plant diversity and bat diversity were evaluated.

With the participation of workers and farm owners, we implemented a total of 30 plots with an area of 100 m2 (replications) separated by a minimum distance of 300 m, within five different types of crop (treatments) (Table 1). In each plot, we studied: (a) the physical-chemical properties of the soil, (b) non-herbaceous plant diversity, and (c) bats diversity.

Table 1.

Crop (treatments) and number of plots (replications) in the evaluated farms, Northwestern Ecuador.

2.2. Soil Analysis

A linear transect was established in each plot, along which 21 soil subsamples were collected in a zigzag pattern at a depth of 15 cm. The length of the transects was approximately 14 m in 10 × 10 m plots and 100 m in 100 × 1 m plots. The subsamples were homogenized and sent to the Soil, Water, and Foliar Laboratory of the Ecuadorian Ministry of Agriculture. The soil analyses performed were organic matter (OM) content, cation exchange capacity (CEC), macronutrients (N, P, K, Ca, and Mg), and micronutrients (Fe, Mn, Cu, and Zn).

2.3. Arboreal and Bats Diversity

All non-herbaceous plant with a diameter at breast height (DBH) ≥ 3 cm within the crop of the selected plots were inventoried. After a period of two months, to ensure that human presence did not influence data collection, bats sampling was initiated.

Since mist nets are widely recognized as the most effective method for sampling bats communities [18,19], a 10 m × 2 m mist net with a mesh size of 20 mm was installed in each sampling plot. Mist nets were placed at ground level and were open from 5:30 p.m. to 12:30 a.m., with checks carried out every 15 min. The sampling times were selected to coincide with the peak activity of bats [3,6,7]. On all plots, all mist nets were kept open for seven hours per night for two consecutive nights, repeated five times over a period of five months (September, November, December, February, and March). The mist nets were checked simultaneously by five observers (two of the authors and three field assistants), each assigned to a different crop type. The sampling effort was calculated as 4200 m2·h·net (20 m2 of net surface area × 7 h × 30 mist nets), this was expressed in m2 of mist net to allow direct comparison with non-herbaceous plant density, which is also measured in surface area units [9].

The captured animals were identified at the species level, then marked, photographed for record purposes, and immediately released at the site of capture; none were killed, retained, or kept in captivity. It is important to note that Ecuador’s Ministry of Environment, Water, and Ecological Transition approved the protocols and issued scientific research authorizations 10-2013-IC-FAU-DPAP-MA and 01-2015-0-IC-FAU-DPAP-MA. Furthermore, the study adhered to the standards outlined in the ARRIVE guidelines [20].

2.4. Data Analysis

We obtained the numbers in Hill’s series (Q0 = species richness, Q1 = the exponential of Shannon diversity and Q2 = the reciprocal of Simpson diversity), separately for the non-herbaceous plant and the bat communities.

We performed the analyses using nonparametric tests due to the non-normal distribution of the non-herbaceous plants, bat diversity and soil nutrient variables (Shapiro–Wilk p > 0.05). We preliminarily checked multicollinearity among the predictors (nutrient’s concentration and plant richness/diversity) via pairwise correlation, using Spearman’s r ≥ 0.7 as threshold for discarding one of two correlated variables.

The relationships between bat community structure and environmental variables (soil chemistry and non-herbaceous plant community structure) were assessed by means of generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs). To control for site-specific variation and test the pure influence of sets of environmental variables, we included farm as a random effect and plantation type (Table 1) as a fixed effect. We used a Poisson error distribution to model bat species richness (Q0), and a Gaussian error distribution to model bat diversity indices (Q1 and Q2).

The statistical analyses were performed using: InfoStat 2020p [21], Past 5.2.1 [22], and R 4.5.2 [23] softwares.

3. Results

3.1. Soil Characterization

The characterization of soil samples from this region revealed that the predominant soil type was silt. The central tendency measures of OM, CEC, macronutrients and micronutrients are shown in Appendix A. The soils with the highest CEC were found in the polyspecific live fences, mixed plantations, cocoa plantations, and scattered trees in pastures. In contrast, monospecific fences exhibited lower CEC (Appendix A Table A1).

3.2. Bats and Arboreal Diversity

A total of 193 individuals from 16 species of bats were captured, grouped into two families: 94% of the species belong to the family Phyllostomidae, and 6% to the family Vespertilionidae. Glossophaga soricina (Pallas, 1766), Carollia brevicauda (Wied-Neuwied, 1821), Uroderma convexum (Lion, 1902), Carollia perspicillata (Linnaeus, 1758), Sturnira bakeri (Velazco & Patterson, 2014), and Myotis riparius (Handley, 1960), accounted for 81.3% of the captures; Artibeus aequatorialis (Andersen, 1906), Chiroderma villosum (Peters, 1860), Vampyriscus nymphaea (Thomas, 1909), and Artibeus ravus (Miller, 1902), represented 14% of captures; Chiroderma salvini (Dobson, 1878), Chiroderma sp., Gardnerycteris keenani ((Handley, 1960), Micronycteris hirsuta (Peters, 1869), Sturnira ludovici (Anthony, 1924), and Trachops cirrhosus (Spix, 1823) were classified as rare species, represented 4.7% of the captured individuals, each species constituting ≤ 1% of the total captures (Appendix B Table A2).

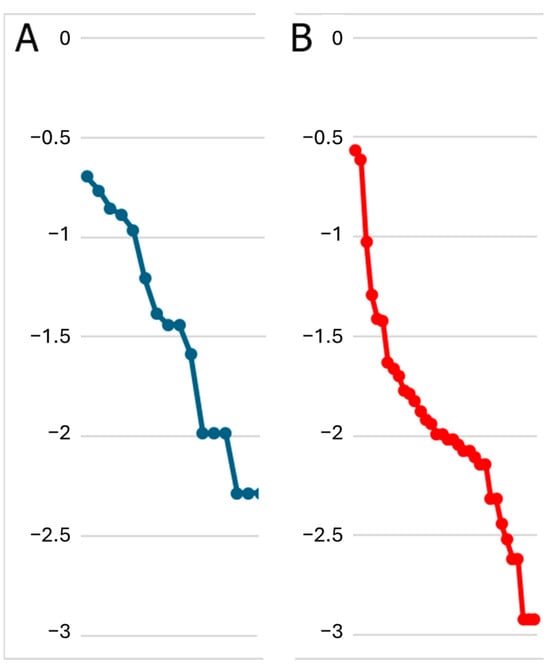

The rank-abundance curve demonstrated that the bat community comprised a high species richness, with the presence of six rare species (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Rank-abundance curves expressed as Log10 of the proportional abundance of species (Pi). (A) bat diversity: The first six species represent 80% of the relative abundance, with collections ranging from 12 to 39 individuals. (B) Arboreal diversity: The first 17 species represent 90% of the relative abundance, with collections ranging from 17 to 452 individuals.

One thousand six hundred and sixty-two non-herbaceous plants, belonging to 34 species were identified. As demonstrated by rank-abundance curve, non-herbaceous plant diversity differs from bat diversity (Figure 2B). A total of seventeen plant species accounted for 90% of the relative abundance, while the remaining 10% was made up of the other 17 plant species (Appendix C Table A3).

3.3. Relationships Between Bat Community Metrics, Non-Herbaceous Plant Diversity and Soil Nutrients

GLMMs revealed relationships between bat community structure and soil properties, and non-herbaceous plant diversity metrics (Table 2). The variables not included in Table 2 showed non-significant values.

Table 2.

GLMM coefficients (slope ± SE) for significant relationships (p < 0.05) between environmental predictors and bat diversity metrics (Q0, Q1) and plant diversity metrics (Q0, Q1), Northwestern Ecuador. G = likelihood ratio test statistic used to assess the significance of fixed effects.

Bat community richness showed significant positive relationships with multiple environmental factors: Q1 non-herbaceous plant diversity expressed by exponential Shannon index, soil organic matter, Ca, and Zn. In contrast, Fe concentration was negatively associated with bat richness (Table 2). GLMMs also indicated that bat diversity responds positively to increases in Ca, Mg, and Zn (p < 0.05) and negatively to increases in Fe (p < 0.0001) (Table 2). The richness and diversity of non-herbaceous plants showed responses to the soil nutrients being similar to those highlighted for bats (Table 2).

4. Discussion

The visual analysis of the rank-abundance curves indicates moderate diversity of bats and arboreal species in the evaluated farms. It is important to note that a previous study in ecological reserves near the study area of our research [24], recorded 41 bat species, while in the evaluated farms we barely recorded 16 bat species [2], this allows inferring that the low number of species recorded may be due to land use changes in our study area from tropical forest to agricultural soils [1]. Pozo-Rivera [9] reported the presence of 16 species of phyllostomids and two of vespertilionids as results of bats inventories applied to four study sites involving eight farms in the same area. In addition, the ecological indices used in this study showed higher values in polycultures than in monocultures, which suggests a positive relationship between non-herbaceous plant diversity and bats diversity in the two farms evaluated, despite such a relationship did not emerge as statistically significant in our model.

Livestock farms in northwestern Ecuador have different types of forest arrangements, including fruit orchards, secondary forests, primary forests and forest plantations [25]. A recent study demonstrated the presence of 31 different tree species used as live fences within farms located along the northern coast of Ecuador [9]. Both the previously cited studies, as well as the present work, agree that there is a high percentage of native tree species used as crops in Ecuadorian agricultural systems.

Our results suggest that bat richness and diversity increase with higher non-herbaceous plant diversity and higher soil organic matter, Ca, Mg, and Zn, while decreasing with higher soil Fe. These patterns support the idea that soil bioelements and soil fertility can structure biodiversity indirectly by shaping the quality, diversity, and phenology of non-herbaceous plant communities that supply food and habitat to bats [15,16].

Soil organic matter is central to this “bottom-up” mechanism because it strongly influences both soil function and nutrient availability. Even when OM represents a relatively small fraction of the soil mass, it can have outsized effects on soil aggregation, water retention, infiltration, and nutrient exchange, thereby supporting plant productivity and stabilizing nutrient supply across time. OM also affects soil-solution chemistry and the availability of macro and micronutrients, and can detoxify harmful substances and reduce stress in acidic soils. Importantly, OM can chelate micronutrients (including Fe and Zn) and form organomineral complexes that regulate whether nutrients remain available for plant uptake or become immobilized [26,27]. Thus, the positive association between OM and bat diversity in our study is consistent with a system in which OM improves plant performance and resource production (flowers, fruits, foliage quality), increasing the availability and continuity of food resources and roosting opportunities for bats across a heterogeneous agricultural mosaic.

Ca, Mg and Zn have been identified as essential bioelements in the context of plant and animal nutrition. In this study, these elements exhibited direct and significant associations with bat diversity and the plants under consideration. Information provided by Peñuelas et al. [15] reveals that soil bioelements are continuously recycled through biogeochemical cycles, circulating between biotic components through food webs and abiotic components through soil, water and atmosphere, which ensures their availability to all organisms. Thus, the availability of key bioelements in the soil has a direct impact on the ecology of communities, affecting the nutritional quality of primary producers and, consequently, the structure and dynamics of food chains that influence the diversity, growth, reproduction and adaptation of organisms [28].

According to the findings of previous studies conducted in the same area [2], the nutritional status of bats is contingent on the quality of the crop. In the two farms under study, it was ascertained that 10 of the bat species captured were frugivorous, two were insectivorous, two were insectivorous/animalivorous, and one was nectarivorous. Parachnowitsch and Manson [29] proposed that the chemical composition of flowers exerts a substantial influence on the interactions between plants and herbivores. Consequently, the chemistry of floral nectar and pollen, regarded as essential phyto-products for ecological balance and constituting the primary food rewards for pollinators, can impact both plant reproduction and the health of nectarivorous bat species.

The stoichiometric evaluation of pollen in 26 studies of different plant species indicates that it contains different concentrations of essential elements such as C, N, P, Cu, Na, K, Ca, Mg and Zn [16]. These concentrations, among other factors, depend on the availability of soil bioelements. Concurrent with this, studies focusing on nectar chemistry have demonstrated that this floral product, in addition to its high sugar content, contains bioelements such as Cl, Cu, K, Ca, Na, and Zn. The distinct chemical composition of these elements is found to be contingent upon the stoichiometry of the soil in which the evaluated plants grow [30].

Schade et al. [28] suggested that the bioelement availability in the soil influences leaf chemistry, thereby affecting the physiology and ecology of herbivores. This establishes a direct link between soil biogeochemistry and the chemical composition of herbivore food. In the context of biogeochemical cycles and ecological stoichiometry, Ca, Mg, and Zn have been shown to be positively and significantly correlated with the diversity of bats and plants on the farms evaluated in this study. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that the soil provides plants with the necessary nutrients to produce nectar and pollen, which are rich in bioelements, making them more attractive to pollinating insects and bats [16]. At the same time, this contributes to an increase in the abundance, richness and diversity of bats and plants. The enhancement of pollinator diversity has been demonstrated to improve plant fertilization processes, thereby favoring the dispersal, germination, and survival of plant species. Concurrently this has a significant influence on the formation of fruit available to frugivorous bat species, while high insect diversity attracts insectivorous bats, especially in major conserved ecosystems [31].

The highest levels of Mg were recorded in polyspecific live fences and in trees scattered in paddocks, which are crops that also presented the highest richness of non-herbaceous plants and bats. Wdowiak [32] point out that the availability of Ca and Mg in the soil is a key factor to promote a greater diversity of plant cover, since these nutrients directly influence the growth and competitiveness of plant species. Ca is essential for cell wall stability and root development [33], promoting colonization of species with deep root systems. Mg, being a central component of the chlorophyll tetrapyrrole ring [34], is essential for photosynthesis and allows the establishment of plants with high growth rates. Thus, soils well supplied with Ca and Mg can support a greater plant diversity generating heterogeneity of plant resources, such as fruits, leaves, flowers and even refuges for bats and other animals. Likewise, different tree species have varied phenological cycles such as flowering or fruiting at different times, which extends the availability of resources for animal species throughout the year [35] and, on the other hand, tree diversity regulates factors such as humidity, temperature and light availability, which directly influence the composition of animal communities [36].

Likewise, Zn is an essential plant micronutrient which promotes the synthesis of tryptophan, a precursor of auxins, which favors plant growth. It also improves photosynthetic efficiency by stabilizing the RuBisCo enzyme and modulating carbonic anhydrase activity, which results in increased carbon fixation and biomass production. In addition, Zn has been demonstrated to enhance the ability of plants to withstand environmental stresses by regulating water uptake, mitigating the effects of heat and salt stresses, and activating antioxidant mechanisms that protect against oxidative damage [37]. These responses are not only instrumental in optimizing plant growth and health but also serve to increase their nutritional value. For herbivorous bats, Zn obtained through trophic chains is essential for processes such as cell proliferation, differentiation and regulation of the immune system [38]. In addition, it contributes to the activation of transcription factors, the modulation of kinases and phosphatases, and cellular homeostasis, which enhances their health and adaptive capacity. Consequently, ensuring sufficient Zn availability in the soil is advantageous not only for plants but also for bats, which depend on them for nutrition.

In contrast, the negative association between Fe and bat diversity suggests that higher Fe may act as a signal of soil conditions that constrain plant performance or nutrient accessibility. Microelements can have narrow margins between deficiency and toxicity, and soil disturbance, particularly where hydrocarbons and associated degradation processes alter soil chemistry, may increase acidity and shift micronutrient profiles [25]. Solly et al. [39] demonstrated that the acidic conditions can promote the formation and dominance of Fe oxides and hydroxides, which may influence sorption, retention, and the physicochemical stabilization of organic matter and nutrients, sometimes reducing their effective availability to plants. More broadly, Fe oxides are major binding agents involved in soil aggregation processes and can interact strongly with OM, affecting how nutrients and carbon are retained in soil [26]. Taken together, these mechanisms support the interpretation that higher soil Fe in our sites may reflect a soil chemical environment (e.g., increased acidity and altered redox/sorption dynamics) that limits resource production or alters plant community structure, ultimately reducing the habitat quality and trophic resources needed to sustain diverse bat assemblages.

Finally, the joint positive relationships of bat diversity with non-herbaceous plant diversity and with OM, Ca, Mg, and Zn reinforce the view that edaphic conditions and aboveground vegetation interact to shape bat assemblages in tropical agricultural mosaics. Where soils better support productive, structurally diverse non-herbaceous plant communities, resource availability (flowers, fruits, insects) and microhabitat heterogeneity likely increase, benefiting multiple bat trophic guilds. This interpretation aligns with broader evidence that bat communities track vegetation structure and habitat quality across disturbed and agricultural landscapes, including responses to landscape features and habitat elements that maintain connectivity and resources [2,13].

5. Conclusions

The present study provides further evidence of the importance of maintaining well-nourished soils to promote the growth and health of trees, which serve as primary roosts for bats in agricultural systems. Our results show that the soil nutrients Ca, Mg, Zn and Fe have a substantial linear relationship with the richness and diversity of both bats and non-herbaceous plants in agricultural landscapes. These findings suggest that the presence of these specific soil nutrients favors the establishment and maintenance of healthy and productive non-herbaceous plants. Consequently, non-herbaceous plant species provide key food resources that favor the permanence and survival of bat communities in tropical agricultural systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.E.P.-R. and M.I.A.-H.; methodology, W.E.P.-R., M.I.A.-H. and P.R.-S.; formal analysis, W.E.P.-R., M.I.A.-H., and P.R.-S.; data curation, W.E.P.-R., M.I.A.-H., P.R.-S.; resources, W.E.P.-R. and M.I.A.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, W.E.P.-R. and M.I.A.-H.; writing—review and editing, W.E.P.-R. and M.I.A.-H., and P.R.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The field trips were supported by Vicerrectorado de Investigaciones of the Universidad de las Fuerzas Armadas ESPE through research grants PIC-068 and PIC-DCV-019.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not involve human beings or clinical trials requiring Institutional Committee approval. No animals were sacrificed or kept in captivity. All field activities adhered to biosafety standards. The Ministry of Environment, Water, and Ecological Transition of Ecuador authorized the research under permits 10-2013-IC-FAU-DPAP-MA and 01-2015-0-IC-FAU-DPAP-MA. The study complied with ARRIVE guidelines and applicable regulations [20].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/appendices. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Gabriel Moya, Sebastian Recalde, Noelly Ruiz, Mayra Morales, and Karonila Yazán for their help in collecting field data. We also thank to Soil, Water and Foliar Laboratory of the Ministry of Agriculture of Ecuador for soil analysis. Finally, to Xavier Paredes-Chiquiza and Armando Echeverría, for their help in preparing Figure 1.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FFG | Fundo del Guanabano Farm |

| FSA | Santa Anita Farm |

| OM | Organic matter content |

| CEC | Cation exchange capacity |

| Q0 | Species richness, |

| Q1 | Exponential of Shannon diversity |

| Q2 | Reciprocal of Simpson diversity |

| GLMMs | Generalized linear mixed models |

| G | likelihood ratio test statistic used to assess the significance of fixed effects |

| Pi | Proportional abundance of species |

| RuBisCo | Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase enzyme |

| S | Richness species |

| eH’ | Exponential of Shannon index |

| 1/λ | Reciprocal of Simpson index |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Physicochemical structure of soils in the crop types evaluated.

Table A1.

Physicochemical structure of soils in the crop types evaluated.

| Crop Type | Variable | n | Mean | S.D. | S.E. | V.C. | Mín. | Máx. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cocoa plantations | ph | 6 | 5.73 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.35 | 5.71 | 5.75 |

| OM(%) | 6 | 8.34 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.36 | 8.31 | 8.37 | |

| N(%) | 6 | 0.42 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 4.76 | 0.4 | 0.44 | |

| P(ppm) | 6 | 3.9 | 0.3 | 0.17 | 7.69 | 3.6 | 4.2 | |

| K(cOMl/Kg) | 6 | 0.32 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 9.38 | 0.29 | 0.35 | |

| Ca(cOMl/Kg) | 6 | 5.07 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.59 | 5.04 | 5.1 | |

| Mg(cOMl/Kg) | 6 | 0.65 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.54 | 0.64 | 0.66 | |

| Fe(ppm) | 6 | 272.8 | 0.1 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 272.7 | 272.9 | |

| Mn(ppm) | 6 | 9.89 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 9.88 | 9.9 | |

| Cu(ppm) | 6 | 7.36 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.41 | 7.33 | 7.39 | |

| Zn(ppm) | 6 | 5.3 | 0.3 | 0.17 | 5.66 | 5 | 5.6 | |

| CEC | 6 | 21.68 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 21.66 | 21.7 | |

| Humidity % | 6 | 33.12 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 33.1 | 33.14 | |

| Sand | 6 | 47 | 1 | 0.58 | 2.13 | 46 | 48 | |

| Silt | 6 | 43 | 1 | 0.58 | 2.33 | 42 | 44 | |

| Clay | 6 | 10 | 2 | 1.15 | 20 | 8 | 12 | |

| Live fence of Erythrina | ph | 6 | 6.09 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.81 | 6.03 | 6.12 |

| OM(%) | 6 | 4.54 | 0.84 | 0.49 | 18.57 | 3.87 | 5.49 | |

| N(%) | 6 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 18.64 | 0.19 | 0.27 | |

| P(ppm) | 6 | 4.23 | 1.1 | 0.63 | 25.91 | 3.6 | 5.5 | |

| K(cOMl/Kg) | 6 | 0.32 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 48.24 | 0.15 | 0.45 | |

| Ca(cOMl/Kg) | 6 | 6.66 | 2.58 | 1.49 | 38.76 | 4.68 | 9.58 | |

| Mg(cOMl/Kg) | 6 | 1.07 | 0.36 | 0.21 | 34.18 | 0.74 | 1.46 | |

| Fe(ppm) | 6 | 425.2 | 16.48 | 9.51 | 3.88 | 406.5 | 437.6 | |

| Mn(ppm) | 6 | 11.61 | 0.93 | 0.54 | 8 | 10.55 | 12.29 | |

| Cu(ppm) | 6 | 5.63 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 4.32 | 5.37 | 5.85 | |

| Zn(ppm) | 6 | 10.14 | 0.29 | 0.17 | 2.85 | 9.83 | 10.4 | |

| CEC | 6 | 17.98 | 5.86 | 3.38 | 32.57 | 11.22 | 21.48 | |

| Humidity % | 6 | 33.31 | 1.87 | 1.08 | 5.6 | 31.44 | 35.17 | |

| Sand | 6 | 40 | 7.21 | 4.16 | 18.03 | 34 | 48 | |

| Silt | 6 | 45.33 | 2.52 | 1.45 | 5.55 | 43 | 48 | |

| Clay | 6 | 16 | 4.36 | 2.52 | 27.24 | 11 | 19 | |

| Polyspecific live fence | ph | 6 | 6.07 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 1.25 | 5.98 | 6.12 |

| OM(%) | 6 | 12.5 | 2.93 | 1.69 | 23.42 | 9.43 | 15.26 | |

| N(%) | 6 | 0.62 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 23.38 | 0.47 | 0.76 | |

| P(ppm) | 6 | 4.17 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 6.04 | 3.9 | 4.4 | |

| K(cOMl/Kg) | 6 | 0.6 | 0.27 | 0.15 | 44.54 | 0.32 | 0.85 | |

| Ca(cOMl/Kg) | 6 | 12.74 | 3.24 | 1.87 | 25.39 | 9.53 | 16 | |

| Mg(cOMl/Kg) | 6 | 2.22 | 0.49 | 0.28 | 22.02 | 1.92 | 2.78 | |

| Fe(ppm) | 6 | 160.2 | 31.03 | 17.92 | 19.37 | 133 | 194 | |

| Mn(ppm) | 6 | 10.91 | 2.12 | 1.23 | 19.48 | 9.57 | 13.36 | |

| Cu(ppm) | 6 | 6.57 | 0.35 | 0.2 | 5.32 | 6.28 | 6.96 | |

| Zn(ppm) | 6 | 11.72 | 2.73 | 1.58 | 23.28 | 9.17 | 14.6 | |

| CEC | 6 | 25.95 | 7.15 | 4.13 | 27.57 | 17.69 | 30.14 | |

| Humidity % | 6 | 45.8 | 2.57 | 1.48 | 5.61 | 43.23 | 48.37 | |

| Sand | 6 | 46 | 2 | 1.15 | 4.35 | 44 | 48 | |

| Silt | 6 | 43.33 | 1.53 | 0.88 | 3.53 | 42 | 45 | |

| Clay | 6 | 10.67 | 2.89 | 1.67 | 27.06 | 9 | 14 | |

| Mixed plantations | ph | 6 | 5.88 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.34 | 5.86 | 5.9 |

| OM(%) | 6 | 9.49 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 9.48 | 9.5 | |

| N(%) | 6 | 0.47 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 6.38 | 0.44 | 0.5 | |

| P(ppm) | 6 | 6.2 | 0.2 | 0.12 | 3.23 | 6 | 6.4 | |

| K(cOMl/Kg) | 6 | 1.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 1 | 1.02 | |

| Ca(cOMl/Kg) | 6 | 12.7 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 5.51 | 12 | 13.4 | |

| Mg(cOMl/Kg) | 6 | 1.55 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 3.23 | 1.5 | 1.6 | |

| Fe(ppm) | 6 | 286 | 4 | 2.31 | 1.4 | 282 | 290 | |

| Mn(ppm) | 6 | 15.43 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.19 | 15.4 | 15.46 | |

| Cu(ppm) | 6 | 7.05 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 2.13 | 6.9 | 7.2 | |

| Zn(ppm) | 6 | 19.83 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.2 | 19.79 | 19.87 | |

| CEC | 6 | 22.98 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 22.96 | 23 | |

| Humidity % | 6 | 43.74 | 0.1 | 0.06 | 0.23 | 43.64 | 43.84 | |

| Sand | 6 | 33 | 1 | 0.58 | 3.03 | 32 | 34 | |

| Silt | 6 | 57.67 | 1.53 | 0.88 | 2.65 | 56 | 59 | |

| Clay | 6 | 9.33 | 1.15 | 0.67 | 12.37 | 8 | 10 | |

| Scattered trees in pastures | ph | 6 | 6.1 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 1.34 | 6.03 | 6.19 |

| OM(%) | 6 | 5.84 | 2.75 | 1.59 | 47.12 | 3.28 | 8.75 | |

| N(%) | 6 | 0.3 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 44.51 | 0.18 | 0.44 | |

| P(ppm) | 6 | 7.6 | 6.93 | 4 | 91.16 | 3.6 | 15.6 | |

| K(cOMl/Kg) | 6 | 0.6 | 0.45 | 0.26 | 74.81 | 0.3 | 1.11 | |

| Ca(cOMl/Kg) | 6 | 6.49 | 0.96 | 0.55 | 14.72 | 5.53 | 7.44 | |

| Mg(cOMl/Kg) | 6 | 0.85 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 14.74 | 0.73 | 0.98 | |

| Fe(ppm) | 6 | 335.73 | 98.09 | 56.63 | 29.22 | 275 | 448.9 | |

| Mn(ppm) | 6 | 11.18 | 1.78 | 1.03 | 15.96 | 9.2 | 12.66 | |

| Cu(ppm) | 6 | 5.99 | 1.15 | 0.66 | 19.11 | 4.79 | 7.07 | |

| Zn(ppm) | 6 | 12.05 | 3.21 | 1.85 | 26.65 | 8.36 | 14.2 | |

| CEC | 6 | 21.74 | 1.26 | 0.73 | 5.79 | 20.48 | 23 | |

| Humidity % | 6 | 31.42 | 9.63 | 5.56 | 30.66 | 20.33 | 37.74 | |

| Sand | 6 | 32 | 5.29 | 3.06 | 16.54 | 28 | 38 | |

| Silt | 6 | 48.67 | 3.51 | 2.03 | 7.22 | 45 | 52 | |

| Clay | 6 | 22.67 | 3.79 | 2.19 | 16.7 | 20 | 27 |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Bat species distribution by crop type.

Table A2.

Bat species distribution by crop type.

| Bat Species | Cocoa Plantations | Mixed Plantations | Scattered Trees in Pastures | Polyspecific Live Fences | Live Fences of Erythrina | Relative Abundance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glossophaga soricina | 8 | 9 | 4 | 16 | 2 | 20.2 |

| Carollia brevicauda | 2 | 21 | 10 | 17.1 | ||

| Uroderma convexum | 6 | 6 | 12 | 3 | 14.0 | |

| Carollia perspicillata | 3 | 7 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 13.0 |

| Sturnira bakeri | 1 | 5 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 10.9 |

| Myotis nigricans | 12 | 6.2 | ||||

| Artibeus aequatorialis | 2 | 5 | 1 | 4.1 | ||

| Chiroderma villosum | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3.6 | ||

| Vampyriscus nymphaea | 4 | 3 | 3.6 | |||

| Artibeus ravus | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2.6 | |

| Chiroderma sp. | 1 | 1 | 1.0 | |||

| Chiroderma trinitatum | 1 | 1 | 1.0 | |||

| Gardnerycteris keenani | 1 | 1 | 1.0 | |||

| Micronicterys hirsuta | 1 | 0.5 | ||||

| Sturnira ludovici | 1 | 0.5 | ||||

| Trachops cirrhosus | 1 | 0.5 | ||||

| Q0 = S | 6 | 13 | 5 | 12 | 8 | |

| Q1 = eH’ | 5.14 | 8.28 | 4.04 | 9.28 | 9.02 | |

| Q2 = 1/λ | 4.47 | 5.62 | 3.33 | 8.08 | 10.91 |

Appendix C

Table A3.

Non-herbaceous plant species distribution by crop type.

Table A3.

Non-herbaceous plant species distribution by crop type.

| Plant Species | Cocoa Plantations | Mixed Plantations | Scattered Trees in Pastures | Polyspecific Live Fences | Life Fences of Erythrina | Relative Abundance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erythrina smithiana | 14 | 137 | 301 | 27.20 | ||

| Theobroma cacao | 280 | 82 | 6 | 37 | 24.37 | |

| Cordia alliodora | 39 | 118 | 9.45 | |||

| Erithryna poeppigiana | 16 | 69 | 5.11 | |||

| Musa paradisiaca | 64 | 3.85 | ||||

| Spondias mombin | 7 | 56 | 3.79 | |||

| Citrus sinensis | 8 | 31 | 2.35 | |||

| Citrus aurantium | 30 | 6 | 2.17 | |||

| Citrus reticulata | 5 | 28 | 1.99 | |||

| Jathropa curcas | 28 | 1.68 | ||||

| Manihot sculenta | 27 | 1.62 | ||||

| Annona muricata | 25 | 1.50 | ||||

| Gliricidia sepium | 22 | 1.32 | ||||

| Erythrina poeppigiana | 20 | 1.20 | ||||

| Coffea canephora | 2 | 17 | 1.14 | |||

| Guadua sp. | 17 | 1.02 | ||||

| Iriartea deltoidea | 3 | 14 | 1.02 | |||

| Phyllantus juglandifolius | 3 | 13 | 0.96 | |||

| Carica papaya | 7 | 9 | 0.96 | |||

| Helicostylis tovarensis | 3 | 12 | 0.90 | |||

| Annona cherimola | 14 | 0.84 | ||||

| Persea americana | 9 | 5 | 0.84 | |||

| Ficus sp. | 10 | 3 | 0.78 | |||

| Attalea colenda | 10 | 2 | 0.72 | |||

| Baccharis sp. | 12 | 0.72 | ||||

| Aegiphilia alba | 8 | 0.48 | ||||

| Cecropia sp. | 5 | 3 | 0.48 | |||

| Coffea arabiga caturra | 6 | 0.36 | ||||

| Psidium guajaba | 5 | 0.30 | ||||

| Artocarpus altilis | 4 | 0.24 | ||||

| Citrus limonia | 4 | 0.24 | ||||

| Undeterminated | 2 | 0.12 | ||||

| Inga sp. | 2 | 0.12 | ||||

| Tabebuia sp. | 2 | 0.12 | ||||

| Q0 = S | 1 | 5 | 19 | 28 | 1 | |

| Q1 = eH’ | 1 | 4.09 | 13.57 | 15.56 | 1 | |

| Q2 = 1/λ | 1 | 3.62 | 9.67 | 10.57 | 1 |

References

- Sierra, R.; Tirado, M.; Palacios, W. Forest-cover changes from labor-and capital-intensive commercial logging in the southern Chocó rainforests. Prof. Geogr. 2003, 55, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo-Rivera, W.E.; Martin-Solano, S.; Carrillo-Bilbao, G. Response of phyllostomid bat diversity to tree cover types in north-western Ecuador. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, M.; Kalko, E.K.V. Foraging strategy and breeding constraints of Rhinophylla pumilio (Phyllostomidae) in the Amazon lowlands. J. Mammal. 2007, 88, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Cabadilla, L.D.; Stoner, K.E.; Henry, M.; Añorve, M.Y. Composition, structure and diversity of phyllostomid bat assemblages in different successional stages of a tropical dry forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 258, 986–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-García, J.L.; Santos-Moreno, A. Efectos de la estructura del paisaje y de la vegetación en la diversidad de murciélagos filostómidos (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) de Oaxaca, México. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2014, 62, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelm, D.H.; Wiesner, K.R.; von Helversen, O. Effects of artificial roosts for frugivorous bats on seed dispersal in a Neotropical forest–pasture mosaic. Conserv. Biol. 2008, 22, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés-Delgado, N.; Sosa, V.J. Do bats roost and forage in shade coffee plantations? A perspective from the frugivorous bat Sturnira hondurensis. Biotropica 2014, 46, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, A.; Harvey, C.A.; Sánchez-Melo, D.; Vilchez, S.; Hernández, B. Bat diversity and movements in an agricultural landscape in Matiguás, Nicaragua. Biotropica 2007, 39, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo-Rivera, W.E. Relaciones de la Diversidad Arbórea y la Estructura Del Paisaje Agrícola Tropical Ecuatoriano Con La Biodiversidad de Murciélagos Filostómidos. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de La Habana, La Habana, Cuba, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pozo-Rivera, W.E.; Cárdenas-Tello, C.D.; Echeverría, A.; Berovides-Álvarez, V.; Ricardo-Nápoles, N. Efecto de la estructura del paisaje agrícola en la diversidad arbórea. Bol. Téc. Ser. Zool. 2017, 13, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kunz, T.H.; Braun de Torrez, E.; Bauer, D.; Lobova, T.; Fleming, T.H. Ecosystem services provided by bats. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1223, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasso, M.; Balakrishnan, M. Ecological and economic importance of bats (Order Chiroptera). ISRN Biodivers. 2013, 2013, 187415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, C.A.; Medina, A.; Merlo Sánchez, D.; Vílchez, S.; Hernández, B.; Sáenz, J.C.; Maes, J.M.; Casanoves, F.; Sinclair, F.L. Patterns of animal diversity in different forms of tree cover in agricultural landscapes. Ecological Applications 2006, 16, 1986–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey-Ehrenbold, A.; Bontadina, F.; Arlettaz, R.; Obrist, M.K. Landscape connectivity, habitat structure and activity of bat guilds in farmland-dominated matrices. J. Appl. Ecol. 2013, 50, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñuelas, J.; Fernández-Martínez, M.; Ciais, P.; Jou, D.; Piao, S.; Obersteiner, M.; Vicca, S.; Janssens, I.A.; Sardans, J. The bioelements, the elementome, and the biogeochemical niche. Ecology 2019, 100, e02652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipiak, M.; Weiner, J. Plant–insect interactions: The role of ecological stoichiometry. Acta Agrobot. 2017, 70, 1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdridge, L. Ecología Basada en Zonas de Vida; IICA: San José, Costa Rica, 1982.

- Pech-Canche, J.M.; MacSwiney, C.; Estrella, E. Importancia de los detectores ultrasónicos para mejorar los inventarios de murciélagos Neotropicales. Therya 2010, 1, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracamonte, J.C. Protocolo de muestreo para la estimación de la diversidad de murciélagos con redes de niebla en estudios de ecología. Ecol. Austral. 2018, 28, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percie du Sert, N.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; Emerson, M.; et al. Reporting animal research: Explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Rienzo, J.A.; Casanoves, F.; Balzarini, M.G.; González, L.; Tablada, M.; Robledo, C.W. InfoStat, versión 2016; Grupo InfoStat, FCA, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba: Córdoba, Argentina, 2016. Available online: http://www.infostat.com.ar (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. PAST: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 9. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Tirira, D.G. Guía de Campo de Los Mamíferos del Ecuador, 1st ed.; Editorial Murciélago Blanco: Quito, Ecuador, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Villacís, J.; Chiriboga, C. Relaciones entre las variables socioeconómicas y la cobertura arbórea de fincas ganaderas del trópico húmedo. Rev. Cubana Cienc. For. 2016, 4, 149–163. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, J.; Kleber, M. The contentious nature of soil organic matter. Nature 2015, 528, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleber, M.; Eusterhues, K.; Keiluweit, M.; Mikutta, C.; Mikutta, R.; Nico, P.S. Mineral–organic associations: Formation, properties, and relevance in soil environments. Adv. Agron. 2015, 130, 1–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schade, J.D.; Kyle, M.; Hobbie, S.E.; Fagan, W.F.; Elser, J.J. Stoichiometric tracking of soil nutrients by a desert insect herbivore. Ecol. Lett. 2003, 6, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parachnowitsch, A.L.; Manson, J.S. The chemical ecology of plant-pollinator interactions: Recent advances and future directions. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2015, 8, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, V.; Sarkar, B.C.; Sharma, H.K.; Bawa, A.S. Physico-chemical properties and estimation of mineral content in honey produced from different plants in Northern India. Food Chem. 2003, 82, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Fernandes, A.S.; Araújo-Fernandes, A.C.; Guedes, P.; Cassari, J.; Mata, V.A.; Yoh, N.; Rocha, R.; Palmeirim, A.F. Responses of insectivorous bats to different types of land-use in an endemic-rich island in Central West Africa. Biol. Conserv. 2025, 302, 110910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wdowiak, A.; Podgórska, A.; Szal, B. Calcium in plants: An important element of cell physiology and structure, signaling, and stress responses. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2024, 46, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, T.; Li, J.; He, Y.; Shankar, A.; Saxena, A.; Tiwari, A.; Maturi, K.C.; Solanki, M.K.; Singh, V.; Eissa, M.A.; et al. Role of calcium nutrition in plant physiology: Advances in research and insights into acidic soil conditions—A comprehensive review. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 210, 108602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.Y.; He, D.D.; Bai, S.; Zeng, W.Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, M.; Wu, L.Q.; Chen, Z.C. Physiological and molecular advances in magnesium nutrition of plants. Plant Soil 2021, 468, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestro, R.; Deslauriers, A.; Prislan, P.; Rademacher, T.; Rezaie, N. From roots to leaves: Tree growth phenology in forest ecosystems. Curr. For. Rep. 2025, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Landuyt, D.; Verheyen, K.; De Frenne, P. Tree species mixing can amplify microclimate offsets in young forest plantations. J. Appl. Ecol. 2022, 59, 1428–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsonev, T.; Cebola Lidon, F.J. Zinc in plants—An overview. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2012, 24, 322–333. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267030914_Zinc_in_plants_-_An_overview (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Wessels, I.; Fischer, H.J.; Rink, L. Dietary and physiological effects of zinc on the immune system. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2021, 41, 133–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Han, F.X.; Su, Y.; Zhang, T.L.; Sun, B.; Monts, D.L.; Plodinec, M.J. Assessment of soil organic and carbonate carbon storage. Geoderma 2008, 143, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.