Abstract

This paper presents an experimental and numerical investigation of continuous reinforced concrete (RC) beams made of self-compacting concrete (SCC) strengthened with fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) bars using the Near-Surface Mounted (NSM) method. While the majority of previous studies have focused on simply supported beams, this work examines two-span continuous beams, which are more representative of real structural behavior. Four SCC beams were tested under static loading to evaluate the influence of the FRP reinforcement position on flexural capacity and deformational characteristics. The beams were strengthened using glass FRP (GFRP) bars embedded in epoxy adhesive within pre-cut grooves in the concrete cover. Experimental results showed that FRP reinforcement significantly increased the ultimate load capacity, while excessive reinforcement reduced ductility, leading to a more brittle failure mode. A three-dimensional finite element model was developed in Abaqus/Standard using the Concrete Damage Plasticity (CDP) model to simulate the nonlinear behavior of concrete and the bond–slip interaction at the epoxy–concrete interface. The numerical predictions closely matched the experimental load–deflection responses, with a maximum deviation of less than 3%. The validated model provides a reliable tool for parametric analysis and can serve as a reference for optimizing the design of continuous SCC beams strengthened by the NSM FRP method.

1. Introduction

The use of self-compacting concrete (SCC) in structural members has become increasingly prevalent in various construction applications [1]. The concept of SCC originated in Japan through the research of Okamura et al. [2,3]. SCC is a high-performance concrete that can flow and consolidate under its own weight without external vibration, owing to the presence of chemical admixtures that enhance viscosity and stability. The main advantages of SCC, besides reducing labor and noise, include improved filling ability and superior compaction in elements with dense reinforcement or complex formwork, minimizing segregation and voids.

Structural strengthening has attracted significant attention due to the deterioration of existing infrastructure and the need to satisfy modern design requirements [4]. Corrosion of reinforcing steel is a major issue in reinforced concrete (RC) structures exposed to aggressive environments, leading to reduced service life and impaired load-bearing capacity [5]. Strengthening is also required for damaged structures after earthquakes or accidental loads, or when changes in design codes or functional use demand increased capacity. Given the current state of concrete infrastructure globally, the research interest in effective strengthening techniques remains high.

Apart from modifying the cross-sectional dimensions, the load-bearing capacity of RC members can be improved by applying external reinforcement. In recent decades, fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) composites have become the preferred choice for retrofitting, replacing traditional steel-based systems due to their excellent mechanical and durability properties [6]. FRP materials consist of high-strength fibers embedded in a polymer matrix, commonly classified as AFRP (Aramid FRP), CFRP (Carbon FRP), or GFRP (Glass FRP), depending on the fiber type [7]. The main advantages of FRP are their high strength-to-weight ratio, corrosion resistance, and ease of installation [8], while the disadvantages include higher cost, linear elastic behavior, and poor fire resistance [7]. FRP is now widely used in strengthening columns, beams, slabs, and hybrid structural systems [9]. Comprehensive recent reviews summarize the flexural behavior, design considerations, and long-term performance of FRP-reinforced concrete beams, providing updated guidelines for practical applications [10].

Two main methods are employed for flexural strengthening of RC beams with FRP materials:

- The Externally Bonded (EB) method, where FRP laminates are glued to the tension face of the beam—simple and cost-effective;

- The Near-Surface Mounted (NSM) method, where bars or strips are embedded in grooves within the concrete cover—offering improved performance.

Hybrid systems combining both methods (CEBNSM) have also been proposed to maximize their respective advantages. Several comprehensive reviews have examined the performance of hybrid EB/NSM systems, confirming their superior flexural efficiency and improved interfacial behavior compared with individual methods [11,12]. Additional studies have shown that the flexural capacity of RC beams can also be enhanced using FRP grid–PCM composite strengthening systems [13].

Most experimental and numerical investigations on FRP-strengthened RC beams have been conducted on members made of conventional vibrated concrete (VC). Comprehensive reviews summarize the flexural behavior, design methodologies, and long-term performance of FRP-strengthened VC beams [10]. In contrast, studies focusing specifically on SCC beams remain comparatively limited, despite their increasing use in practice.

Several researchers have demonstrated that SCC beams exhibit flexural performance comparable to, or slightly superior to, VC beams when strengthened with FRP systems. Mabrouk and Rasha [14] and Yaw et al. [15] reported good agreement between experimental and numerical results for SCC beams, with deviations generally below 10%. Khatab et al. [16] experimentally investigated continuous SCC deep beams, highlighting the need for additional studies addressing flexural behavior and strengthening strategies specific to SCC.

The majority of existing studies focus on simply supported beams, although many real RC structures—such as bridges and frames—are inherently continuous. Akbarzadeh et al. [17] emphasized that the response of continuous beams strengthened with FRP remains insufficiently investigated. Experimental evidence indicates that the effectiveness of FRP strengthening in continuous beams strongly depends on reinforcement configuration, particularly in negative moment regions above intermediate supports [18,19,20,21,22,23,24].

Experimental studies on continuous beams strengthened using CFRP or GFRP laminates and NSM systems have consistently reported significant increases in load capacity and improved ductility [19,20,21,22,23,25]. Recent parametric investigations further highlighted the influence of FRP layout, anchorage, and bond length on the flexural response of continuous beams strengthened with NSM FRP bars [26,27].

Numerical modeling using finite element analysis (FEA), most commonly implemented in Abaqus, has become a powerful tool for simulating the behavior of FRP-strengthened RC members. Previous studies successfully modeled static and fatigue behavior [24,28], viscoelastic stress transfer at the FRP–concrete interface [29], and prestressed RC beams strengthened with NSM CFRP rods [30], and conducted detailed parametric numerical analyses [31]. Other investigations extended numerical approaches to high-performance fiber-reinforced cementitious composites (HPFRCC) and innovative NSM joint configurations, validated through combined experimental and numerical programs [32,33,34]. Recent research also includes the monitoring of damage in NSM CFRP/GFRP-strengthened RC beams using free vibration-based techniques [35].

More recently, attention has shifted toward hybrid confinement and cyclic loading behavior, reflecting realistic service and seismic conditions. In this context, the recent study by Chen et al. [36] on the performance and modeling of FRP–steel dually confined reinforced concrete under cyclic axial loading provides valuable insights into confinement mechanisms and advanced constitutive modeling strategies, which are directly relevant for improving numerical simulations of FRP-strengthened RC systems under complex loading conditions.

Despite the growing body of research, there remains a lack of studies addressing the flexural behavior of continuous SCC beams strengthened with the NSM FRP method. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the performance of such beams through a combined experimental and numerical approach. Four two-span continuous SCC beams with identical geometry and reinforcement were tested, varying only the position of the GFRP strengthening. The finite element model developed in Abaqus/Standard was validated against experimental results to assess the influence of FRP layout on load capacity and deformation behavior.

The results provide a better understanding of the flexural response of continuous SCC beams and offer guidance for the practical application of FRP strengthening in real structures.

2. Experimental Investigation

2.1. Mechanical Properties of Materials

2.1.1. Mechanical Properties of SCC Concrete

The experimental program on self-compacting concrete (SCC) encompassed the evaluation of both fresh and hardened concrete properties. Although the primary focus of this study is on the mechanical behavior of hardened concrete, the principal characteristics of the fresh mixture are briefly presented to provide a complete overview of the investigated material.

The designed SCC mixture was composed of 320 kg/m3 of cement and 100 kg/m3 of limestone filler, with natural aggregates divided into three fractions: 0–4 mm (807.5 kg/m3), 4–8 mm (380 kg/m3), and 8–16 mm (553 kg/m3). The water content of 210 kg/m3 corresponded to a water-to-cement ratio of approximately 0.49. A polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer (MC Power Flow 1102, MC-Bauchemie Müller GmbH & Co. KG, Bottrop, Germany), with a density of 1.06 kg/dm3, was incorporated at a dosage of 0.5% relative to the total mass of cementitious materials.

The fresh SCC exhibited a density of approximately 2305 kg/m3, a slump-flow diameter of 605 mm, and a T500 flow time of 4.8 s. Based on the classification criteria specified in EFNARC [37] and EN 206-9:2010 [38], the mixture was categorized as SF1 in terms of flowability and VS2 in terms of viscosity, confirming adequate filling ability and segregation resistance for SCC applications.

The mechanical properties of hardened concrete were determined on fifteen 150 mm cubes and six 150 mm diameter cylinders of 300 mm length specimens cast simultaneously with the beam elements.

The following parameters were obtained: compressive strength after 2, 7, 14, and 28 days (fc,2, fc,7, fc,14, fc,28) and on the day of testing (fc,test), as well as the modulus of elasticity after 28 days (Ec,28) and on the day of testing (Ec,test). For each compressive strength age, three cube specimens were tested, resulting in a total of fifteen cubes, while six cylinder specimens were used for the determination of the modulus of elasticity at 28 days and at the testing age. All tests were conducted in accordance with EN 206-1 [39] and EC2 [40] standards. The mean values and corresponding standard deviations (σ) of the results are summarized in Table 1. It is worth mentioning that the tensile strength of concrete was not tested due to the limitations and complexity associated with conducting direct tensile tests on concrete specimens; instead, in the numerical model, the tensile strength of concrete was indirectly derived from the compressive strength using available validated empirical expressions.

Table 1.

The test results obtained on hardened concrete.

2.1.2. Mechanical Properties of Steel and FRP Reinforcement

The mechanical properties of steel reinforcement were taken from the manufacturer’s technical documentation, while those of FRP bars were determined experimentally at the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, University of Nis [41]. The tests were conducted in accordance with ACI standards [42].

Table 2 provides a summary of the main mechanical properties of the steel and GFRP bars. The steel reinforcement (B500B) showed the expected yield strength, while the GFRP bars exhibited a linear elastic behavior up to failure, as typical for FRP composites.

Table 2.

Mechanical properties of steel and GFRP reinforcement.

2.1.3. Mechanical Properties of Epoxy Adhesive

The epoxy adhesive used for embedding the GFRP bars was a two-component structural resin, and for the epoxy adhesive–concrete connection, the two-component thixotropic primer was used. In the absence of test data, the mechanical properties were selected from the manufacturer’s technical data sheets [34,43], and the values used in this study are given in Table 3 [44].

Table 3.

Mechanical properties of epoxy adhesive and/or primer (suppliers’ data).

2.2. Test Specimens

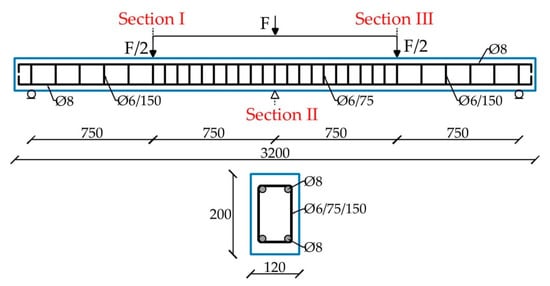

Four continuous beams were made of SCC concrete in accordance with the program of experimental testing. The beams have the same percentage of longitudinal and transverse reinforcements shown in Figure 1. The tested beams have a rectangular cross section, having dimensions b/h = 120/200 mm, a total length of 3200 mm, a beam span of 1500 mm, and reinforced with B500B reinforcement, with Ø8 bars used as longitudinal reinforcement and Ø6 bars used as stirrups.

Figure 1.

Reinforcing of the tested beams.

2.3. Strengthening Method and Variants of Strengthening

The strengthening of RC beams was performed using the Near-Surface Mounted (NSM) technique, following the recommendations found in the literature [19]. The procedure consisted of the following steps:

- •

- Cutting grooves in the concrete cover with a diamond saw (25 × 25 mm) in beams reinforced with GFRP bars;

- •

- Cleaning the grooves and applying a primer;

- •

- Filling the grooves halfway with epoxy adhesive and placing the GFRP bars;

- •

- Completing the filling with epoxy so that the final beam surface remained visually identical to that of the unstrengthened control beam.

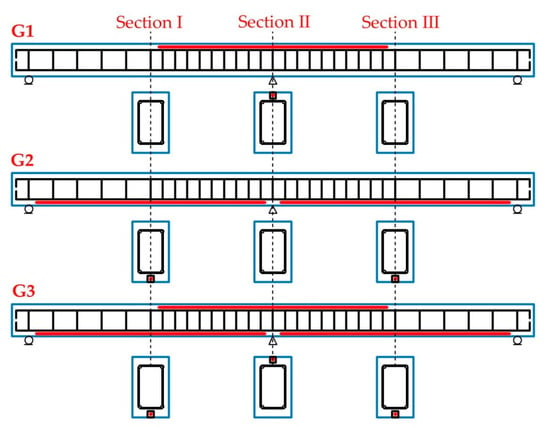

The strengthening configurations are illustrated in Figure 2. In beam G1, GFRP reinforcement was installed only above the middle support; in beam G2, it was placed in the tension zone of both spans; while beam G3 was strengthened both above the support and in the span zones.

Figure 2.

Variants of strengthening of tested beams.

2.4. Testing Procedure

The testing of the beam girders was carried out in the mechatronics laboratory using the measuring equipment of the structural testing laboratory of the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering and the Faculty of Civil Engineering, both of the University of Nis. The beams were loaded using a hydraulic actuator through a steel spreader beam that transferred two concentrated forces to the specimen (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Testing setup.

The applied load was measured using an HBM (Hottinger Baldwin Messtechnik GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) U2A load cell, while deflections were continuously recorded by linear variable displacement transducers (LVDTs) positioned at the mid-span section of each beam. The data acquisition during testing was performed using MGC-plus and SPIDER8 systems (HBM, Darmstadt, Germany), which converted mechanical quantities into electrical signals recorded and processed using the Catman 5.1 software package (HBM, Darmstadt, Germany). The loading was applied incrementally under displacement control until failure. In addition, strain gauges were installed on the longitudinal steel reinforcement, on the GFRP bars, and on the concrete surface in selected cross-sections to monitor strain development. In the present paper, the mid-span deflection data, as well as strains in tensioned steel reinforcement, GFRP bars and compressed concrete, are analyzed and discussed, as they are directly relevant for validating the numerical model and assessing flexural behavior.

A detailed description of the experimental setup, loading arrangement, and measurement instrumentation—including the complete layout and sensor positions—is available in the authors’ previous publication [45]. Only the key aspects required to understand the testing procedure are summarized herein.

2.5. Results of Experimental Testing

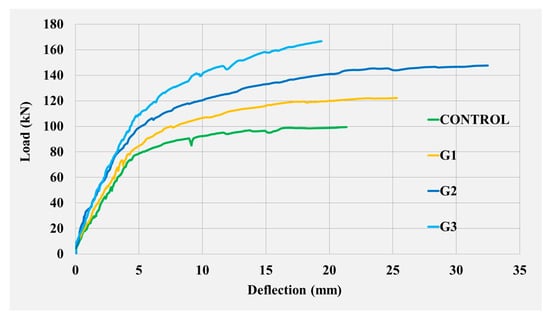

The behavior of the tested beams can best be seen in the diagram of the dependence between the load and the deflections of the section in the middle of the span, shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Mid-span deflection for tested beams.

The behavior of the beams is almost identical at the beginning of the test, with slight differences in the load at which the first cracks appear. After that, the strengthened beams show greater stiffness, which indicates a decrease in ductility, but their behavior is still nonlinear.

With the occurrence of yielding of the tensioned steel reinforcement in the most loaded section, the behavior changes further, and the load required for yielding is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Yielding load of the tested beams.

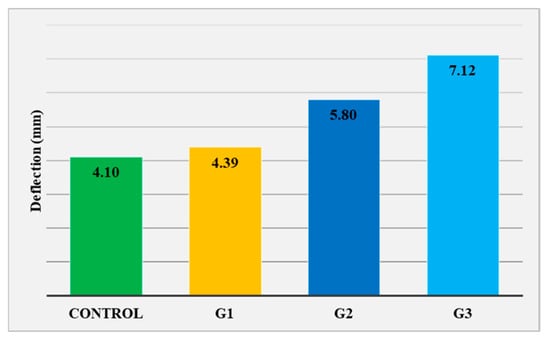

The deflections of the cross-section at mid-span at the moment of yielding in the tensioned steel reinforcement are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Mid-span deflections of the tested beams at yielding load.

Already at this stage, a difference in the behavior of the tested beams is clearly noticeable, both in terms of load-bearing capacity and deformation behavior.

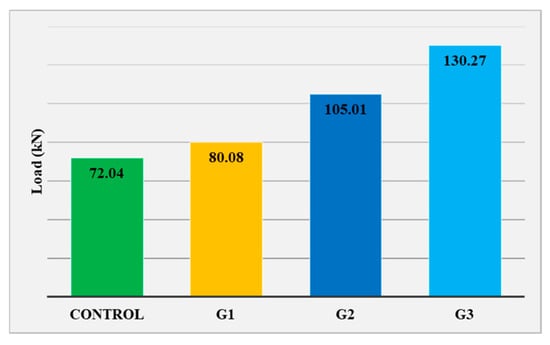

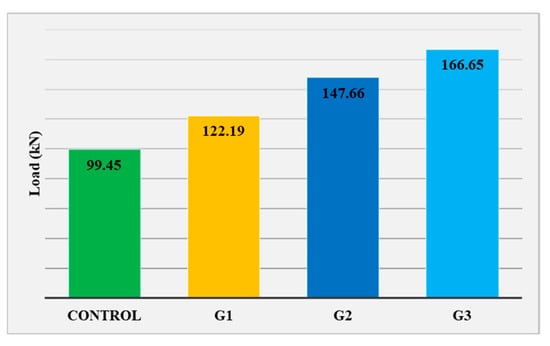

The ultimate load-carrying capacities of the tested beams, presented in Figure 7, clearly illustrate the increase in strength achieved through the applied strengthening techniques.

Figure 7.

Ultimate load of the tested beams.

The types of beam failure observed in the beams are as follows:

- •

- Control beam: formation of plastic hinges due to yielding of the steel reinforcement;

- •

- G1 beam: plastic hinge formation in the span sections followed by concrete crushing above the middle support, without FRP debonding;

- •

- G2 beam: plastic hinge formation above the middle support, followed by concrete cover separation near the level of tensile steel reinforcement;

- •

- G3 beam: simultaneous FRP debonding and concrete cover separation, resulting in sudden failure and significant damage under a much higher load than the control beam.

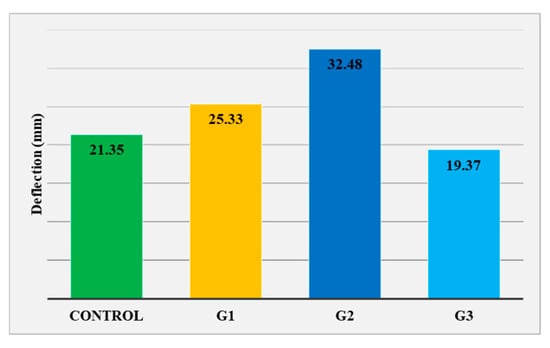

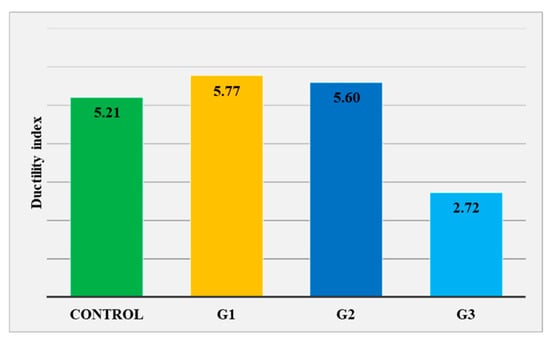

The corresponding mid-span deflections at failure are presented in Figure 8. Compared to the control beam, G1 and G2 exhibited larger ultimate deflections, while G3 showed reduced deformability and sudden failure. The ductility index, defined as the ratio of deflection at failure to deflection at steel yielding, is illustrated in Figure 9 and confirms the limited ductility of beam G3.

Figure 8.

Maximum deflections at mid-span of the tested beams.

Figure 9.

Ductility index of the tested beams.

3. Numerical Study

3.1. Finite Element Model

Following the experimental investigation, a detailed three-dimensional finite element (FE) model was developed in Abaqus/Standard to simulate the flexural behavior of the tested reinforced concrete (RC) beams strengthened with Near-Surface Mounted (NSM) fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) bars. The modeling strategy, material definitions, and boundary conditions are described in the subsequent sections.

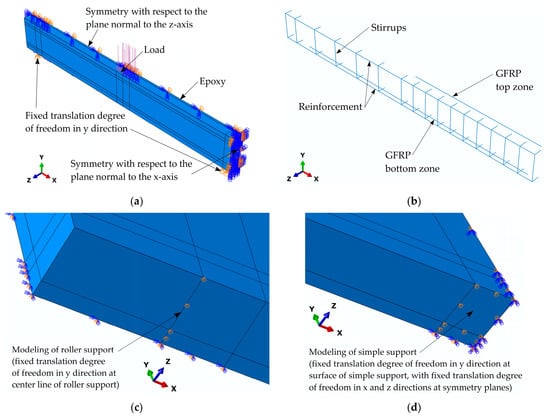

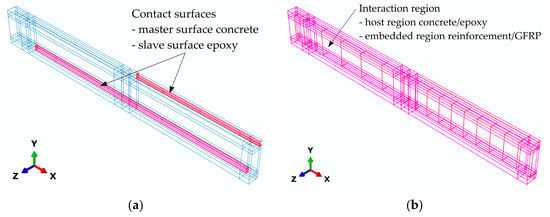

The FE models were developed to reflect the geometry of the beams tested in the laboratory (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). Due to the double symmetry, only one quarter of the beams were modeled in order to reduce the computational time. The configuration of beam G3, including the boundary and symmetry conditions applied in the planes normal to the x- and z-axes, is illustrated in Figure 10a, while Figure 10b presents the layout of the internal reinforcement and the GFRP bars. The other beam models follow a similar configuration, with minor modifications in the epoxy and GFRP components depending on the RC beam reinforcement cases.

Figure 10.

FE model G3: (a) beam geometry and boundary conditions; (b) geometry of reinforcement and GFRP bars; (c) details of roller support; (d) details of simple support.

In the experimental setup, the middle support was a simple support, while the end supports were roller supports. Although these supports were not modeled in full detail, appropriate boundary conditions were applied in the numerical simulations. Specifically, at a distance of 100 mm from the beam end, which coincides with the centerline of the roller support, the displacements in the y direction at the bottom nodes were constrained, allowing translation in the beam axis direction (Figure 10c). In the middle section the displacements in the y direction were constrained to a length of 100 mm, which corresponds to the support width (50 mm due to symmetry). This, together with the boundary conditions on the symmetry planes (constrained translations in x and z directions), represents simple support (Figure 10d). During the experimental tests, loads were applied using steel bearing plates positioned at one-half points along the spans. In the numerical models, this setup was simplified by applying surface pressure directly to the top face of the concrete beams, omitting the steel plates (Figure 10a).

3.2. Material Models

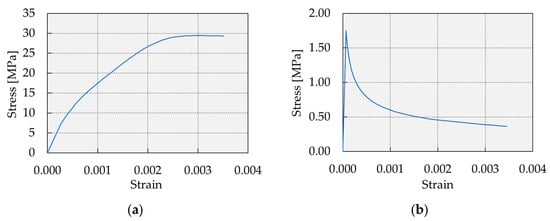

The concrete was modeled using a concrete damage plasticity (CDP) material model. The stress–strain diagram (σc–εc) of concrete under compression was experimentally obtained on a cylindrical specimen at the time of beam testing (Figure 11a). The linear elastic behavior of concrete under compression was modeled with modulus of elasticity E = 25.35 GPa (Table 1) and Poisson’s ratio ν = 0.20 up to the compressive stress approximately corresponding to the 40% of compressive strength, which is in accordance with the standard [40]. After that point, nonlinear behavior was modeled according to the experimentally obtained stress–strain diagram.

Figure 11.

Concrete stress–strain diagrams: (a) under compression; (b) under tension.

The tensile behavior of the concrete (represented by the σt–εt curve) was described using the equation provided in [46]:

where ft denotes the tensile strength of the concrete, while εcr represents the strain corresponding to that tensile strength.

In the absence of experimental data, the concrete’s tensile strength (ft) was determined based on the expression suggested in [47], which relates it to the compressive strength of concrete (fc) at the time of beam testing (reference compressive strength obtained as the difference between the compressive strength mean value and the standard deviation, see Table 1):

The strain corresponding to the concrete’s tensile strength was calculated as εcr = 0.00006896. This value marks the limit of the elastic response of the examined concrete in tension. Based on the adopted model, the stress–strain relationship under tensile loading is illustrated in Figure 11b.

The Concrete Damaged Plasticity (CDP) model characterizes the inelastic behavior of concrete by accounting for degradation under both compressive and tensile stresses. This modeling approach is considered suitable for simulating quasi-brittle materials, as supported by various studies [48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. To implement the CDP model, several material parameters must be specified. These parameters are selected based on established guidelines from the referenced literature [48,49,50,51,52,53,54] as follows: dilation angle ψ = 35°, flow potential eccentricity є = 0.1, ratio of the biaxial compressive and uniaxial compressive yield stress σb0/σc0 = 1.16, ratio of the second stress invariant on the tensile meridian to that on the compressive meridian at initial yield K = 0.666, and viscosity parameter μ = 0.0001.

When concrete undergoes unloading after entering the strain-softening region of the stress–strain response, either in compression or tension, its stiffness is no longer fully recovered. This indicates a reduction in the material’s elastic stiffness due to accumulated damage. Within the CDP framework, this stiffness degradation is represented by scaling down the initial elastic modulus [55] using a factor of 1 − dc for compressive behavior and 1 − dt for tensile behavior [48]. The damage variables dc (for compression) and dt (for tension) are defined according to the following equations [48]:

The damage variables are expressed in terms of inelastic strain for compression (εcin) and cracking strain for tension (εtcr). The inelastic strain under compression and the cracking strain under tension are defined as the difference between the total strain and the elastic strain associated with the undamaged material response. Using these strain measures as input, the software computes the corresponding plastic strains in both compressive and tensile regimes, following the procedures outlined in [48]. To capture total material failure, the sudden loss of material stiffness, which leads to a rapid increase in damage parameters, is considered. This approach follows calibration and sensitivity analysis for compression, as well as previous recommendations for tension, and is applied upon reaching the ultimate strain: εcu = 0.0035 in compression (experimentally obtained) and εtu = 0.0035 in tension, according to the recommendation that cracks open at a strain 50 times greater than the tensile strength strain [51].

There are several approaches for epoxy material modeling, such as the elastoplastic model [56,57] and the viscoelastic model for the study of the long-term behavior of strengthened RC beams [29]. Furthermore, some researchers used the same finite element type for epoxy and concrete to simulate tensile splitting cracks of epoxy [58]. Considering the observation of a small-width crack on the epoxy during the experimental testing of the beams, the same constitutive model applied for concrete, the CDP model, was used for the epoxy’s material properties. The modeling approach described earlier in this section was likewise followed for the epoxy, with the distinction that its elastic modulus was taken as Ee = 4000 MPa, compressive strength fce = 70 MPa, and tensile strength fte = 30 MPa (Table 3) [44]. It should be noted that experimental data for stress–strain relationships for epoxy were not available; therefore, after the calibration of the model, the diagram for compression is defined according to the equation recommended for concrete [40]:

where strain at the maximal stress (εc1e) is 0.0205.

The ultimate strain under compression is adopted as 0.025 and under tension 0.01. The corresponding stress–strain relationships in compression and tension for epoxy material are illustrated in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Epoxy stress–strain diagrams: (a) under compression; (b) under tension.

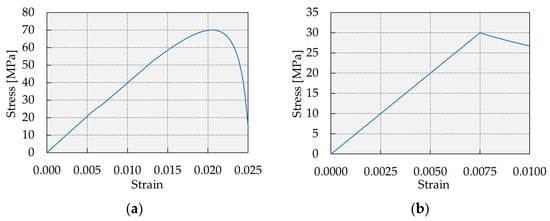

The main steel reinforcement was of grade B500B with the elastic modulus E = 200 GPa and Poisson’s ratio ν = 0.30. The multilinear isotropic hardening model was implemented (Figure 13a), where the data were adopted according to the available experimental results [59]. The stirrups were of steel grade GA240/360 and a bilinear kinematic hardening model was implemented (Figure 13b) using the elastic modulus E = 200 GPa, Poisson’s ratio ν = 0.3, the engineering yield strength fy = 240 MPa, and the tangent modulus approximately Et = 7000 MPa. The GFRP bars were represented as linearly elastic materials, characterized by a modulus of elasticity E = 47 GPa (Table 2) and Poisson’s ratio ν = 0.26.

Figure 13.

Stress–strain diagrams: (a) main reinforcement; (b) stirrups.

3.3. Interaction Model

The interaction between the epoxy layer and the concrete substrate was simulated using cohesive contact elements [58]. The maximum allowable normal stress at the contact interface was defined as 70 MPa, while the maximum shear stress was limited to 6 MPa (Table 3) [44]. The damage progression was characterized through a fracture energy value of 6.12 MPa, consistent with verified and widely accepted models [58,60]. Figure 14a illustrates the interaction surfaces of the epoxy and concrete for the G3 model. Considering that the slippage of steel and GFRP bars was not observed during the experiments, and in accordance with the recommendations of other researchers [30,34,57], the interfaces between the concrete and steel reinforcement, as well as between the epoxy and the GFRP bars, were modeled as perfectly bonded (no slip), utilizing the software’s embedded region feature (Figure 14b).

Figure 14.

Interactions definition: (a) concrete–epoxy; (b) concrete/epoxy–reinforcement/GFRP.

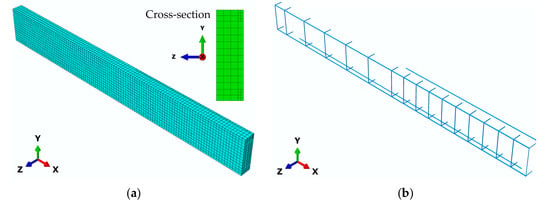

3.4. Finite Element Mesh

The RC beam and the epoxy layer were discretized using solid hexahedral finite elements with three translational degrees of freedom per node (C3D8R in the software) [48]. To mitigate the “shear locking” effect, reduced integration was applied during the stiffness matrix formulation [48,61]. The steel reinforcement and GFRP bars were modeled with two-node truss elements possessing only axial stiffness (T3D2 type) [48]. Cross-sectional areas were assigned based on the diameters of the longitudinal reinforcement, stirrups, and GFRP bars.

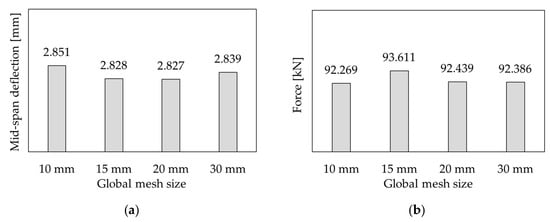

A mesh convergence analysis has been conducted for the control beam in order to check mesh sensitivity and to determine the optimal FE mesh size. In this analysis, four FE sizes have been varied, namely 10, 15, 20, and 30 mm. For a comparative analysis, the value of vertical displacement in the beam mid-span at a load of 60 kN, which is in the post-crack phase of the beam, as well as the value of force at the vertical displacement of 10 mm, which is in the reinforcement post-yield phase, have been selected. It has been concluded (Figure 15) that the results differ by less than 2% for different mesh sizes; therefore, mesh convergency was achieved. For further research, the global mesh size in all analyzed models was 15 mm, as the optimal form from the aspects of computational resources and accuracy of results. For strengthened beam models, the epoxy layer was meshed using elements with a 12.5 mm size, due to its relatively small thickness and the expected high stress gradients within that region. The number of finite elements and nodes for the analyzed models is provided in Table 4. The final finite element mesh for the G3 model is depicted in Figure 16 as a representative example.

Figure 15.

Mesh convergence analysis for model of the control beam: (a) mid-span deflection at load of 60 kN; (b) load at mid-span deflection of 10 mm.

Table 4.

Number of finite elements and nodes for the analyzed models.

Figure 16.

Finite element mesh of the model G3: (a) beam and epoxy; (b) reinforcement and GFRP.

3.5. Numerical Results and Discussion

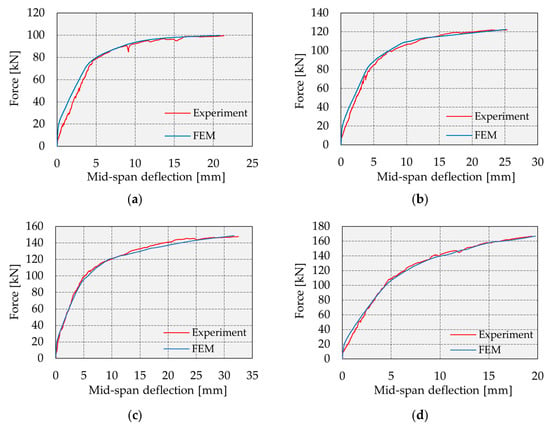

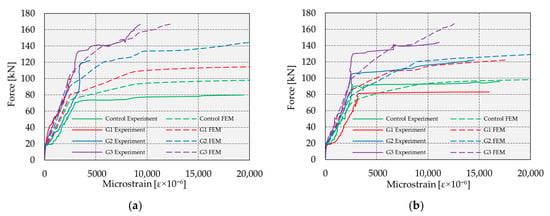

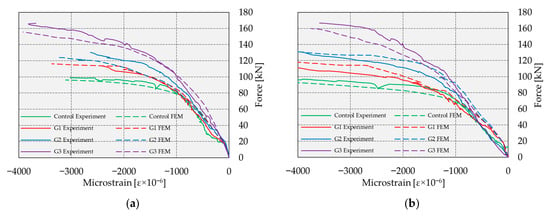

The accuracy of the numerical model was verified by comparing the experimentally obtained and numerically simulated force–deflection curves for all analyzed cases (Figure 17a–d). The comparison revealed a very close correlation between the two sets of results in all three phases of the load–deflection response—namely, in the elastic range, in the phase following initial cracking up to the yielding of the steel reinforcement, and in the phase after reinforcement yielding up to the point of failure. This confirms the validity of the developed model.

Figure 17.

Force–deflection diagrams: (a) control; (b) G1; (c) G2; (d) G3.

The validation of the numerical models was also performed by comparing the load and mid-span deflection values at beam failure (Table 5). Considering that the maximal difference between experimental and numerical results is less than 3%, it can be considered that the numerical models are fully reliable.

Table 5.

Comparison of experimental and numerical ultimate load and mid-span deflection.

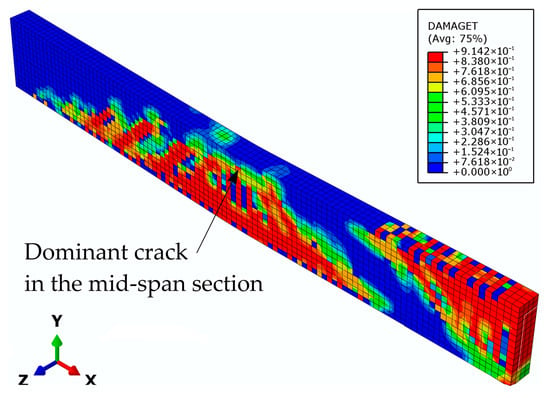

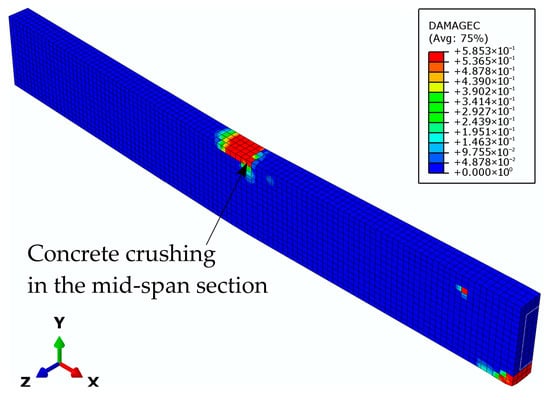

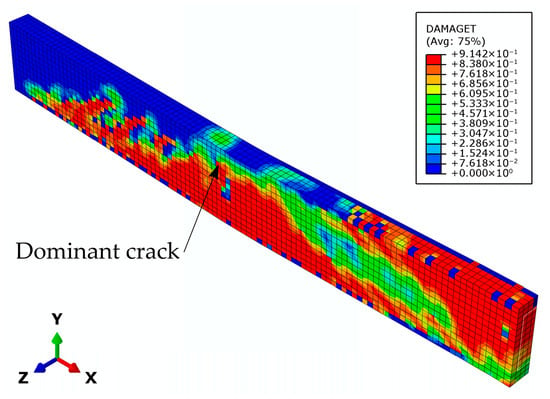

The mechanism of structural failure was examined through crack propagation, concrete crushing, and the transfer of shear stresses (bond stresses) at the epoxy–concrete interface. In the CDP model, the development of cracks was defined by the tensile damage parameter, and the damage at ultimate strain of the analyzed materials was adopted as the crack opening.

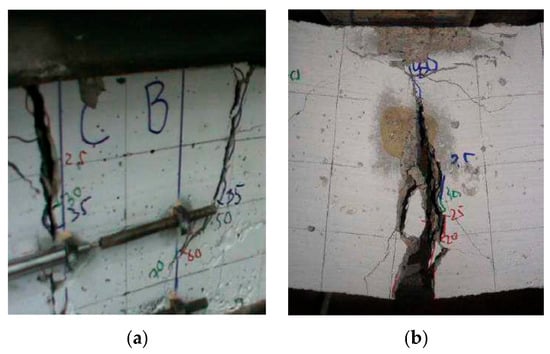

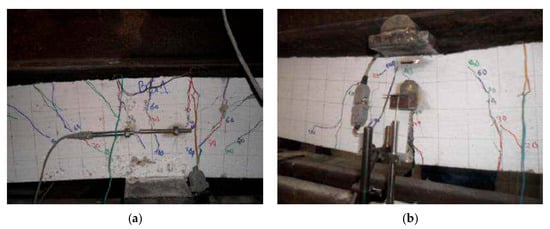

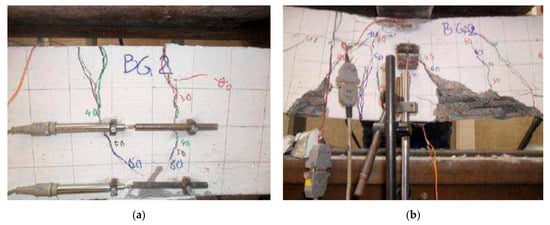

The results indicate that in the unstrengthened beam without GFRP, the dominant crack developed in the mid-span section from the bottom zone up to the upper zone (Figure 18) where concrete crushing appears (Figure 19). These results indicate the development of a plastic hinge in the mid-span section, which occurs after the plastic hinge forms at the mid-support section, and represents beam failure. Considering this, the numerical results show strong agreement with the experimental results (Figure 20).

Figure 18.

Damage parameter in tension at the control beam failure.

Figure 19.

Damage parameter in compression at the control beam failure.

Figure 20.

Experimental control beam failure: (a) mid-support section; (b) mid-span section.

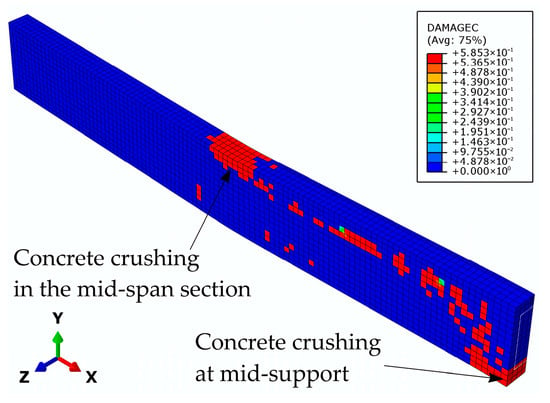

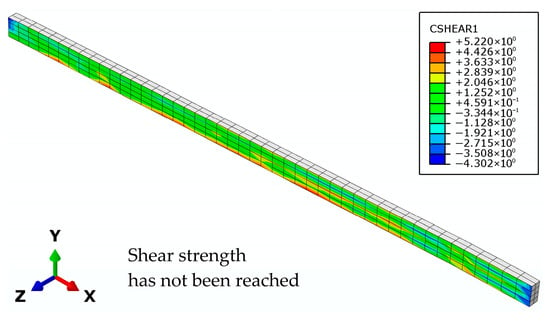

In the case of model G1, the strengthened beam with the GFRP bar in the mid-support top zone, the plastic hinge formation at the mid-span and mid-support sections occurs almost simultaneously. At the mid-support section, the crack system develops, while at the mid-span section, dominant cracks occur (Figure 21), which are followed by concrete crushing in the compressed zone (Figure 22). The shear strength at the epoxy–concrete interface in the top zone of the mid-support section has not been reached at beam failure (Figure 23). Taking this into account, the numerical results are in close agreement with the experimental findings (Figure 24).

Figure 21.

Damage parameter in tension at the beam G1 failure.

Figure 22.

Damage parameter in compression at the beam G1 failure.

Figure 23.

Shear stress at the concrete–epoxy interface at the G1 beam failure.

Figure 24.

Experimental G1 beam failure: (a) mid-support section; (b) mid-span section.

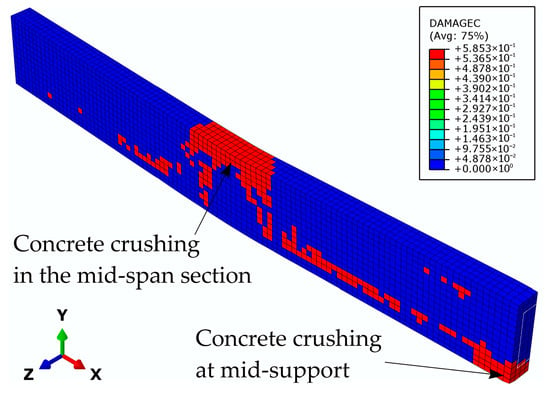

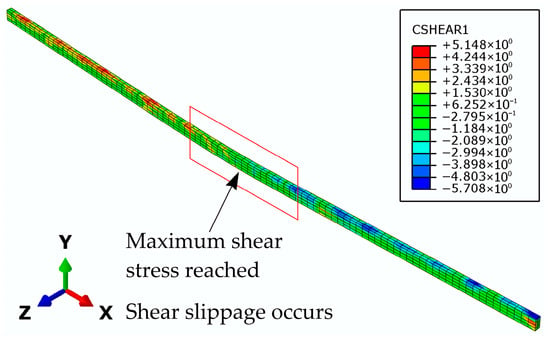

In model G2, the strengthened beam with the GFRP bar in the mid-span bottom zone first displays plastic hinge formation at the mid-support section due to the crack system and concrete crushing (Figure 25 and Figure 26). After that, crack formation on the sides of the load application zone appear, which, together with concrete crushing (Figure 25 and Figure 26) and the shear strength being reached at the epoxy–concrete interface in the mid-span section (indicating debonding) (Figure 27), lead to plastic hinge formation and beam failure. A comparison of the numerical and experimental results (Figure 28) indicates that the numerical model provides an excellent representation of the beam’s actual behavior.

Figure 25.

Damage parameter in tension at the beam G2 failure.

Figure 26.

Damage parameter in compression at the G2 beam failure.

Figure 27.

Shear stress at the concrete–epoxy interface at the G2 beam failure.

Figure 28.

Experimental G2 beam failure: (a) mid-support section; (b) mid-span section.

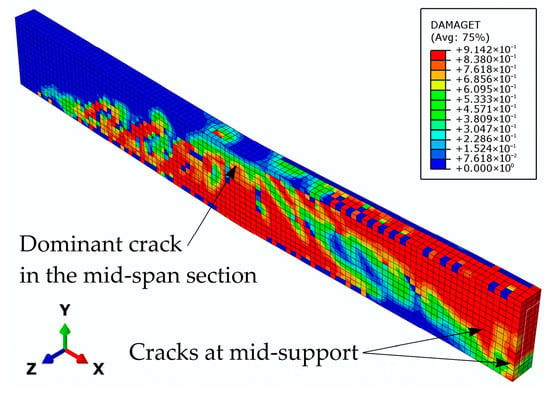

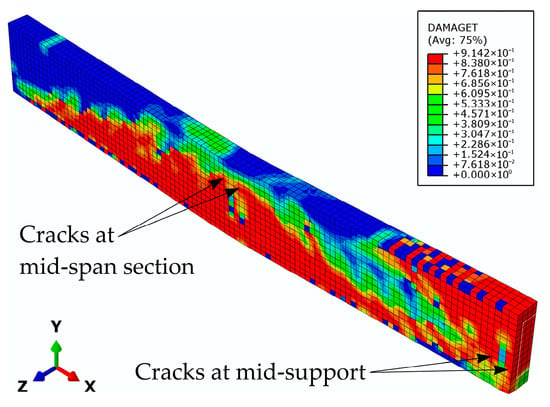

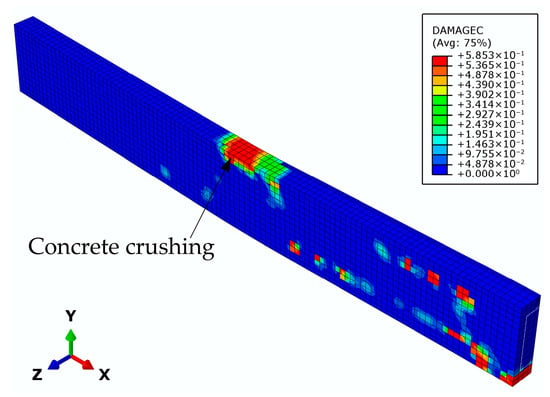

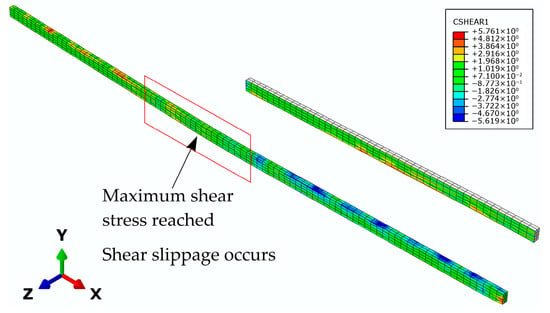

For model G3, the dominant crack appeared near the mid-span section, extending toward the end support (Figure 29), after the plastic hinge formation at the mid-support section. The crack extends all the way to the top zone, where concrete crushing occurs (Figure 30). At the same time, the shear stress at the epoxy–concrete interface in the zone of the mid-span section reached its maximum value, leading to slippage and debonding of the epoxy from the concrete (Figure 31). By comparing the numerical and experimental results (Figure 32), it can be concluded that the numerical model describes the actual behavior of the beam very well.

Figure 29.

Damage parameter in tension at the beam G3 failure.

Figure 30.

Damage parameter in compression at the G3 beam failure.

Figure 31.

Shear stress at the concrete–epoxy interface at the G3 beam failure.

Figure 32.

Experimental G3 beam failure: (a) mid-support section; (b) mid-span section.

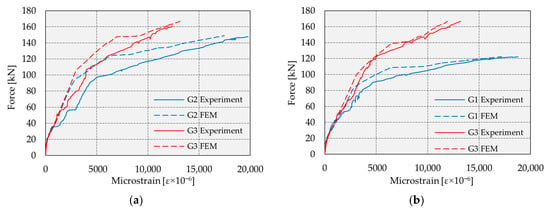

The final validation of the numerical model was performed by comparing the load vs. strain diagrams. Namely, during the experiment, the strains in the tensioned reinforcement, compressed edge of concrete, as well as GFRP bars, were recorded in Section I and Section II of the beam (Figure 2). It is worth mentioning that strain gauges on the reinforcement were damaged during the experiment; therefore, it was not possible to fully record the data. The comparison of the load-strain diagrams is presented in Figure 33, Figure 34 and Figure 35. It can be concluded that there were some slight discrepancies between the numerical and experimental results regarding the analyzed strains in the elastic, post-cracking, and post-yielding phases. However, given the strongly nonlinear nature of the problem and its dependence on multiple physical and mechanical parameters, the observed level of agreement can be regarded as acceptable, thereby supporting the full reliability and validity of the numerical model.

Figure 33.

Force–strain in tensioned reinforcement diagrams: (a) Section I; (b) Section II.

Figure 34.

Force–strain in compressed edge of concrete diagrams: (a) Section I; (b) Section II.

Figure 35.

Force–strain in GFRP bars diagrams: (a) Section I; (b) Section II.

4. Discussion

The experimental and numerical results demonstrate that the placement and amount of GFRP reinforcement significantly influence both the ultimate load and ductility of SCC continuous beams. Among the tested configurations, beam G2, reinforced in the tension zones of both spans, exhibited the most favorable balance between strength and deformability. Similar observations were reported in recent experimental studies investigating the influence of different FRP strengthening patterns on the flexural response of continuous beams [62]. In contrast, beam G3, strengthened in both the top and bottom zones, achieved the highest ultimate load but failed abruptly due to simultaneous epoxy–concrete debonding and protective layer detachment, highlighting that excessive reinforcement can lead to brittle failure. Beam G1, with reinforcement only above the middle support, showed localized concrete crushing without debonding, indicating efficient stress transfer between GFRP bars and surrounding concrete. In addition to global load–deflection behavior, the numerical model was further validated at the strain level by comparing the evolution of strains in steel reinforcement, concrete, and GFRP bars, confirming that the model reliably captures internal force redistribution and stiffness degradation mechanisms, despite unavoidable experimental limitations.

These findings illustrate the critical role of reinforcement layout in controlling structural performance. Even low FRP reinforcement ratios can substantially enhance flexural capacity, while inappropriate placement or excessive reinforcement may compromise ductility. The validated numerical model accurately captures the nonlinear behavior of the beams, including crack formation, concrete crushing, and bond–slip interaction at the epoxy–concrete interface, with maximum deviations in ultimate load and mid-span deflection below 3%. This confirms the model’s suitability for parametric studies and optimization of NSM strengthening interventions.

From a practical perspective, the results indicate that careful design of NSM strengthening is essential to achieve the desired balance between strength and ductility. Strengthening in the tension zones provides an effective compromise, while combined top and bottom reinforcement should be applied with caution to avoid brittle failure. The numerical model developed in this study offers a reliable tool to guide designers in selecting appropriate reinforcement ratios, bar lengths, and placement for continuous SCC beams. Future work should focus on systematic parametric analyses, including long-term behavior, cyclic loading, and environmental effects, to develop comprehensive guidelines for the safe and efficient application of NSM FRP strengthening.

These findings are consistent with previous studies [19,20,21,22,23,24,28,29,63,64], which also reported the importance of bond behavior and reinforcement layout in NSM-strengthened members, as well as the beneficial effect of hybrid CFRP–GFRP systems in improving flexural performance and the influence of service temperature on the end-debonding behavior of NSM CFRP-strengthened beams. The present work, however, extends the existing knowledge by addressing SCC continuous beams rather than conventional RC simply supported specimens, providing a more realistic representation of actual structural systems.

5. Conclusions

Based on the experimental and numerical investigation of SCC continuous beams strengthened with GFRP bars using the NSM method, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- Effectiveness of strengthening: Even a relatively small amount of GFRP reinforcement considerably increased the flexural load capacity of the beams compared to the control specimen.

- Influence on ductility: While NSM strengthening enhances stiffness and strength, it also tends to reduce ductility. The beam with combined top and bottom reinforcement (G3) reached the highest load capacity but exhibited brittle and sudden failure.

- Failure mechanisms:

- •

- The control beam failed through steel yielding and concrete crushing at mid-span.

- •

- The G1 beam failed by crushing of concrete above the middle support.

- •

- The G2 beam failed due to partial separation of the concrete cover near the tensile reinforcement level.

- •

- The G3 beam failed by debonding of the epoxy layer along with the concrete protective layer.

- Numerical validation: The finite element models developed in Abaqus/Standard accurately reproduced the experimental responses, including stiffness, crack formation, ultimate capacity, and strains, confirming the suitability of the modeling approach for further parametric studies.

- Practical implications:

- •

- The NSM technique is effective but requires careful design to avoid over-reinforcement and premature debonding.

- •

- Strengthening in the tension zones (as in beam G2) provides the best compromise between load capacity and ductility.

- •

- The method’s complexity and limitations near supports should be considered when applying it in real structures.

- •

- Due to the limited number of tested beams, a comprehensive statistical analysis could not be performed for all parameters. Nevertheless, the presented experimental and numerical results provide a solid basis for further validation and parametric studies, enabling the reliable use of the developed numerical model for designing NSM FRP strengthening of continuous SCC beams.

- Future work: Further studies should focus on parametric numerical analyses to optimize NSM strengthening configurations. Variables such as FRP bar length, cross-sectional area, and placement can be systematically modified to determine the minimum reinforcement required to achieve the desired flexural performance. This approach would enable designers to efficiently tailor strengthening interventions for continuous SCC beams while ensuring safety and serviceability criteria. Additionally, long-term behavior, cyclic loading, and environmental effects (temperature, moisture, freeze–thaw) should be investigated to provide comprehensive design guidelines.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ž.P. and B.M.; methodology, Ž.P., A.Z., and S.R.; software, A.Z. and P.P.; validation, Ž.P. and S.R.; formal analysis, Ž.P. and B.M.; investigation, Ž.P., B.M., and S.R.; resources, Ž.P. and P.P.; data curation, A.Z. and P.P.; writing—original draft preparation, Ž.P. and B.M.; writing—review and editing, A.Z., S.R., and P.P.; visualization, Ž.P. and A.Z.; supervision, Ž.P.; project administration, P.P.; funding acquisition, Ž.P. and S.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia, under the Agreement on Financing the Scientific Research Work of Teaching Staff at the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering and Civil Engineering in Kraljevo, University of Kragujevac—Registration number: 451-03-137/2025-03/200108 and at the Faculty of Civil Engineering and Architecture, University of Nis—Registration number: 451-03-137/2025-03/200095 dated 4 February 2025.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy concerns.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zitouni, M.; Kada, A.; Lamri, B.; Arruda, M.R. Numerical Analysis of Combined Effect Hybrid Fibres and Fire Insulation on the Fire Resistance Performance of SCC Beams. Period. Polytech. Civ. Eng. 2024, 68, 1255–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamura, H.; Ozawa, K. Mix Design for Self-Compacting Concrete. Concrete. Libr. Jpn. Soc. Civ. Eng. 1995, 25, 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Okamura, H.; Ouchi, M. Self-Compacting Concrete. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 2003, 1, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilotta, A.; Ceroni, F.; di Ludovico, M.; Nigro, E.; Pecce, M.; Manfredi, G. Bond efficiency of EBR and NSM systems for strengthening concrete members. J. Compos. Constr. 2011, 15, 757–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakcali, G.B.; Yüksel, I. Shear Strength Evaluation of Concrete Beams with FRP Transverse Rebar. Period. Polytech. Civ. Eng. 2024, 68, 469–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouroumana, I.; Nafa, Z.; Nigri, G. Numerical Study on the Retrofitting of Exterior RC Beam-column Joints with CFRP Composites Using the Grooving Method. Period. Polytech. Civ. Eng. 2025, 69, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FIB. Externally Bonded FRP Reinforcement for RC Structures; Technical Report on the Design and Use of Externally Bonded Fiber Reinforced Polymer Reinforcement (FRP EBR) for Reinforced Concrete Structures. Bulletin.14 (Task Group 9.3); International Federation for Structural Concrete: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Abd, F. An Introduction to FRP Composites for Construction; ISIS Educational Module 2; A Canadian Network of Centres of Excellence: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bank, L. Composites for Construction; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, H.; Nguyen-Thoi, T.; Dinh, H.-B. State-of-the-Art Review of Studies on the Flexural Behavior and Design of FRP-Reinforced Concrete Beams. Materials 2025, 18, 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darain, K.M.u.; Jumaat, M.Z.; Shukri, A.A.; Obaydullah, M.; Huda, M.N.; Hosen, M.A.; Hoque, N. Strengthening of RC Beams Using Externally Bonded Reinforcement Combined with Near-Surface Mounted Technique. Polymers 2016, 8, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megahed, F.A.; Seleem, M.H.; Badawy, A.A.M.; Abdelrahman, H. The Flexural Response of RC Beams Strengthened by EB/NSM Techniques Using FRP and Metal Materials: A State-of-the-Art Review. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2023, 8, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Qin, H. Study on Flexural Performance of Reinforced Concrete Beams Strengthened with FRP Grid–PCM Composite Reinforcement. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabrouk, T.S.; Rasha, M.A. Behavior of RC beams with tension lap splices confined with transverse reinforcement using different types of concrete under pure bending. Alex. Eng. J. 2018, 57, 1727–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaw, L.T.; Osei, J.B.; Adom-Asamoah, M. On The Non-Linear Finite Element Modelling of Self-Compacting Concrete Beams. J. Struct. Transp. Stud. 2017, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Khatab, T.A.M.; Ashour, F.A.; Sheehan, T.; Lam, D. Experimental investigation on continuous reinforced SCC deep beams and Comparisons with Code provisions and models. Eng. Struct. 2017, 131, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarzadeh, H.; Maghsoudi, A.A. Experimental and analytical investigation of reinforced high strength concrete continuous beams strengthened with fiber reinforced polymer. Mater. Des. 2010, 31, 1130–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, M.A.; Khalifa, T.M.; Mansour, W.N. External Strengthening of RC Continuous Beams Using FRP Plates: Finite Element Model. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Advances in Civil, Structural and Mechanical Engineering—CSM 2014, Birmingham, UK, 1–2 June 2014; ISBN 978-1-63248-054-5. Available online: https://theired.org/conference/paper/external-strengthening-of-rc-continuous-beams-using-frp-plates-finite-element-model-1138 (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Aiello, M.A.; Valente, L.; Rizzo, A. Moment redistribution in continuous reinforced concrete beams strengthened with carbon fiber- reinforced polymer laminates. Mech. Compos. Mater. 2007, 43, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghsoudi, A.A.; Bengar, H.A. Moment redistribution and ductility of RHSC continuous beams strengthened with CFRP. Turk. J. Eng. Environ. Sci. 2009, 33, 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.M.; Jumaat, M.Z. The Effect of CFRP Laminate Length for Strengthening the Tension Zone of the Reinforced Concrete T-Beam. J. Sci. Res. Rep. 2013, 2, 626–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khafaji, A.; Salim, H. Flexural Strengthening of RC Continuous T-Beams Using CFRP. Fibers 2020, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumya, S. Strengthening of RC Continuous Beam Using FRP Sheet; Department of Civil Engineering, National Institute of Technology Rourkela: Odisha, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, C. Numerical investigation for the flexural strengthening of reinforced concrete beams with external pre-stressed HFRP sheets. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 189, 804–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emara, M.; Mostafa, A.H.; Mohamed, H.A.; Zaghlal, M. Performance of Rubberized RC Beams Flexural-Strengthened Using Near-Surface Mounted Systems. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2025, 19, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadhim, M.M.A.; Jawdhari, A.; Altaee, M.M.; Majdi, A.; Fam, A. Parametric Investigation of Continuous Beams Strengthened with Near Surface Mounted FRP Bars. Eng. Struct. 2023, 288, 116619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dushimimana, D.; Li, L.; Zhang, J.; Yang, H.; Liu, J.; Li, Y. Flexural Performance of Reinforced Concrete Beams Strengthened Using Near-Surface Mounted CFRP Bars: Effects of Bonding Patterns. Compos. Struct. 2024, 335, 117985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, C.; Ai, J.; Petru, M.; Liu, Y. Numerical investigation for the fatigue performance of reinforced concrete beams strengthened with external prestressed HFRP sheet. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 237, 117601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, J. Viscoelastic analysis of FRP strengthened reinforced concrete beams. Compos. Struct. 2011, 93, 3200–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, L.; Haryanto, Y.; Hu, H.-T.; Hsiao, F.-P.; Pamudji, G.; Setiadji, B.H.; Hsu, C.-N.; Weng, P.-W.; Lin, C.-C. Prestressed Concrete T-Beams Strengthened with Near-Surface Mounted Carbon-Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Rods Under Monotonic Loading: A Finite Element Analysis. Eng 2025, 6, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chang, Z.; Huang, J. Parameter Analysis for the Flexural Performance of Concrete Beams Using Near-Surface Mounted-Strengthening Application. Buildings 2025, 15, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleghi, R.; Shokoohfar, A.; Farokhzad, R.; Roudsari, M.T. Experimental Investigation of High-performance Fiber reinforced Cementitious Composite and its Effect on RC Beams by Numerical Method. Period. Polytech. Civ. Eng. 2025, 69, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranković, S.; Folić, R.; Zorić, A.; Vacev, T.; Petrović, Ž.; Kovačević, D. Experimental Analysis of an Innovative Double Strap Joint Splicing of GFRP Bars by NSM Methods for Strengthening RC Beams. Period. Polytech. Civ. Eng. 2024, 68, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranković, S.; Zorić, A.; Vacev, T.; Petrović, Ž. Numerical Analysis of an Innovative Double-Strap Joint for the Splicing of Near-Surface Mounted Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Bars for Reinforced Concrete Beam Strengthening. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettucci, E.; Capozucca, R.; Magagnini, E.; Vecchietti, M.V. Detection in RC Beams Damaged and Strengthened with NSM CFRP/GFRP Rods by Free Vibration Monitoring. Buildings 2023, 13, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Wang, Y.; Cai, G.; Larbi, A.S.; Wan, B.; Hao, Q. Performance and Modeling of FRP–Steel Dually Confined Reinforced Concrete under Cyclic Axial Loading. Compos. Struct. 2022, 300, 116076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFNARC. Specifications and Guidelines for Self-Compacting Concrete; EFNARC: Camberley, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- EN 206-9:2010; Concrete—Part 9: Additional Rules for Self-Compacting Concrete (SCC). CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2010.

- EN 206-1:2000; Concrete—Part 1: Specification, Performance, Production and Conformity. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2000.

- EN 1992-1-1:2004; Eurocode 2: Design of Concrete Structures—Part 1-1: General Rules and Rules for Buildings. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2004.

- Ranković, S. Experimental and Theoretical Analysis of Limit State RC Linear Plane Structures Strengthened with NSM FRP Elements. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Niš, Niš, Serbia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- ACI. Guide Test Methods for Fiber-Reinforced Polymers (FRPs) for Reinforcing or Strengthening Concrete Structures (ACI 440.3R-04); Committee 440; American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Abadel, A. Shear strengthening of deficient RC deep beams using NSM FRP system: Experimental and numerical investigation. Mater. Sci. Pol. 2024, 42, 140–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapei FRP System. Available online: www.mapei.com (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Petrović, Ž.; Milošević, B.; Ranković, S.; Mladenović, B.; Zlatkov, D.; Zorić, A.; Petronijević, P. Experimental Analysis of Continuous Beams Made of Self-Compacting Concrete (Scc) Strengthened with Fiber Reinforced Polymer (Frp) Materials. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Hsu, T.T.C. Nonlinear finite element analysis of concrete structures using new constitutive models. Comput. Struct. 2001, 79, 2781–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Taha, M.R. Experimental and Numerical Evaluation of Direct Tension Test for Cylindrical Concrete Specimens. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2014, 2014, 156926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassault Systems. Abaqus Theory Manual; Dassault Systems: Providence, RI, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alfarah, B.; López-Almansa, F.; Oller, S. New methodology for calculating damage variables evolution in Plastic Damage Model for RC structures. Eng. Struct. 2017, 132, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, Ž.; Milošević, B.; Zorić, A.; Ranković, S.; Mladenović, B.; Zlatkov, D. Flexural Behavior of Continuous Beams Made of Self-Compacting Concrete (SCC)—Experimental and Numerical Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacev, T.; Zorić, A.; Grdić, D.; Ristić, N.; Grdić, Z.; Milić, M. Experimental and Numerical Analysis of Impact Strength of Concrete Slabs. Period. Polytech. Civ. Eng. 2023, 67, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhti, R.; Benahmed, B.; Laib, A.; Alfach, M.T. New approach for computing damage parameters evolution in plastic damage model for concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 16, e00834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sümer, Y.; Öztemel, M. Investigation of the Effect of GFRP Reinforcement Bars on the Flexural Strength of Reinforced Concrete Beams Using the Finite Element Method. Fibers 2025, 13, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawki Ali, N.K.; Mahfouz, S.Y.; Amer, N.H. Flexural Response of Concrete Beams Reinforced with Steel and Fiber Reinforced Polymers. Buildings 2023, 13, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassl, P.; Xenos, D.; Nyström, U.; Rempling, R.; Gylltoft, K. CDPM2: A damage-plasticity approach to modelling the failure of concrete. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2013, 50, 3805–3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdesselam, A.; Merdas, A.; Fiorio, B.; Chikh, N.-E. Experimental and Numerical Study on RC Beams Strengthened by NSM Using CFRP Reinforcements. Period. Polytech. Civ. Eng. 2023, 67, 1214–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverria, M.; Perera, R. Three dimensional nonlinear model of beam tests for bond of near-surface mounted FRP rods in concrete. Compos. Part B Eng. 2013, 54, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadhim, M.M.A.; Jawdhari, A.; Peiris, A. Evaluation of lap-splices in NSM FRP rods for retrofitting RC members. Structures 2021, 30, 877–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haefliger, S.; Fomasi, S.; Kaufmann, W. Influence of quasi-static strain rate on the stress-strain characteristics of modern reinforcing bars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 287, 122967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seracino, R.; Raizal Saifulnaz, M.R.; Oehlers, D.J. Generic Debonding Resistance of EB and NSM Plate-to-Concrete Joints. J. Compos. Constr. 2007, 11, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zienkiewicz, O.; Taylor, R.L.; Zhu, J.Z. The Finite Element Method: Basis and Fundamentals, 6th ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 398–404. [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah, M.; Al Mahmoud, F.; Khalil, N.; Khelil, A. Effect of the Strengthening Patterns on the Flexural Performance of RC Continuous Beams Using FRP Reinforcements. Eng. Struct. 2023, 280, 115657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, A.; Shahmansouri, A.A.; Akbarzadeh Bengar, H. Hybrid CFRP–GFRP Sheets for Flexural Strengthening of Continuous RC Beams: Experimentation and Analytical Modeling. Struct. Concr. 2024, 25, e202400264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena, M.; Jahani, Y.; Torres, L.; Barris, C.; Perera, R. Flexural Performance and End Debonding Prediction of NSM Carbon FRP-Strengthened Reinforced Concrete Beams under Different Service Temperatures. Polymers 2023, 15, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.