Abstract

Annex A of EN 1992-1-1:2023—recently revised and amended in the context of the Second Generation of Eurocodes—introduces a method to adjust partial safety factors for the resistance side alongside a set of factors for different conditions and design situations, both for new and existing structures. The method proposed in Annex A is complemented by a set of stochastic models for relevant basic variables and forms a rather simple and objective format to adjust the partial safety factors from the default values offered in EN 1990:2023. Yet, over the last few years, advanced reliability-based methods aligned with modern computational tools have proved to enable rather robust and efficient structural reliability assessments. A thorough comparative analysis is imperative to understand how distinct reliability-based methods can be applied to adjust partial safety factors in the design of new structural components composed of steel-reinforced concrete. This analysis sheds light on the use of different methods to derive partial safety factors for the resolution of common engineering problems and offers inferences regarding possible implications in terms of safety and economic efficiency of design solutions.

1. Introduction

In structural reliability studies, the presence of aleatory and epistemic uncertainties—primarily resulting from (natural) variability and incomplete knowledge, respectively—is widely acknowledged [1]. By being aware of the presence of these uncertainties, one of the prime requirements of structural engineering is to guarantee that every design calculation results in sufficiently low failure probabilities of a structure [1,2]. To ensure reliable structural designs, the partial safety factor format is one of the most widely adopted approaches in modern structural codes or guidelines (e.g., [3,4]). The partial safety factor format results from the application of a semi-probabilistic approach, in which a safety verification is simplified to assess whether a structural component fulfills a given set of inequalities regarding the resistance and the load sides. Here, the design values of basic variables account for the reliability requirement by means of partial safety factors that are normally calibrated with reliability-based approaches. Modern structural codes and guidelines consider distinct partial safety factors resulting from different choices and assumptions adopted in calibration procedures [3,4]. For example, a set of assumptions are considered in [5] based on the work of [2,6]. These assumptions support the specification of statistical values of the variable effective depth and the calibration of the partial safety factor for reinforcing steel as part of the new EN 1992-1-1:2023 [7]—a recently revised code in the context of the Second Generation of Eurocodes. Precisely, in EN 1992-1-1:2023, a set of reference partial safety factors influencing the resistance side are offered (Table 1). Reference values are provided for reinforcing steel , for concrete , and for modulus of elasticity . Additionally, EN 1992-1-1:2023 includes a partial safety factor for shear and punching shear without shear reinforcement . This factor replaces in all the formulae for calculating the shear and punching resistance in components without shear reinforcement [5]. Notwithstanding, these (reference) partial safety factors can be adjusted providing that different conditions and design situations are verified, including that the uncertainties of the basic variables are somehow reduced (e.g., [8,9]).

Table 1.

Partial safety factors for the resistance side (Table 4.3 (NDP) of EN 1992-1-1:2023 [7]).

In this context, the new Annex A of EN 1992-1-1:2023 offers a method to adjust partial safety factors for the resistance side (hereby denoted as , a term representing for steel reinforcement, for concrete, and for shear and punching shear without shear reinforcement). Additionally, this annex introduces a set of values for design situations and conditions alongside stochastic models for a group of relevant basic variables influencing the design of structural components—and, ultimately, the partial safety factors on the resistance side. The premise of these provisions is that adjusted (i.e., meaning reduced) partial safety factors can be utilized in design on the basis of enhanced knowledge of material and geometric properties as well as model uncertainties in combination with strict quality control requirements adopted in the production of building materials (e.g., reinforcing steel and concrete). The previous version of Annex A (part of EN 1992-1-1:2004 + AC:2010 [11]) already includes provisions for the adjustment of partial safety factors on the basis of (i) enhanced quality control (paragraph A.2.1) and (ii) experimental test values: measured geometrical data (paragraph A.2.2) and, particularly for existing structures, experimental data of concrete compressive strength according to the specifications of EN 13791:2019 [12] (paragraph A.2.3). These provisions implicitly recognize that a reduction in the variation of geometric and material strength properties can be attained through more stringent quality control measures, which are exercised in controlling deviations on the dimensions of critical sections and on the values of concrete compressive strength, respectively. Under similar principles, the premises of the new version of Annex A are enhanced and applied to a wider set of conditions and design situations. Provisions are detailed for in situ concrete members (new and existing) as well as for precast concrete members. To support the interpretation of Annex A, an additional document entitled “Background document to 4.3.3 and Annex A. Partial safety factors for materials“ (hereby denoted as ) [5] has been produced.

Simultaneously, other initiatives to adjust partial safety factors have been emerging over the years. For the design of new structures, for example, the German Committee for Structural Concrete (DAfStb) has recently introduced a preliminary version of a guideline entitled Procedure for the derivation of safety factors in concrete structures using probabilistic methods [13]. This two-part document covers the basics for time-invariant design considerations and guides the use of methods to derive partial safety factors when decoupling the load and resistance sides. In the context of existing structures, specific standards and guidelines have also been developed at both international and national levels [14]. The international standards include ISO 13822: 2010 [15] and the European Technical Specifications TS CEN/TC 17440:2020 [16], which include provisions to assess existing structures and guidance to adjust partial safety factors based on condition evaluation and material testing. These standards and specifications have been complemented by other related background documents, including the fib Bulletin 80 [17] and the handbook from Diamantidis and Holickỳ [18], providing a practical procedure to update design values for each basic variable using the method of partial factors. More recently, the fib Model Code 2020 [19] was systematically revised to provide state-of-the-art pre-normative guidance and synthesis of international research with concrete industry and engineering expertise [14]. Following the fib proposals, the group of experts under IABSE TG 1.3 investigated the use of probabilistic and semi-probabilistic methods in the reliability assessment of existing (road) bridges [14] and demonstrated applications of the theoretical principles illustrated in [20], where provisions of Annex A in EN 1992-1-1:2023 are considered. In Germany, the research project ZfPStatik [21,22,23,24] aimed at proposing recommendations for actions about inspection-based reliability analysis of existing bridges by seeking to integrate the benefits of semi-probabilistic and probabilistic assessment concepts and enabling the incorporation of measured data into the reliability analysis of existing structures through partial safety factor modification.

With the recent developments in code generation, standardization, and guidance for both new and existing structures, technological advances in computational capabilities have been emerging over recent decades. For example, Level III methods—e.g., Monte Carlo with Importance Sampling or Monte Carlo with Subset Sampling—and other more avant-garde approaches have gradually become more robust and efficient. Multiple investigations have demonstrated that the use of such methods in the resolution of common structural problems results in a great degree of accuracy and precision. In [25], an overview on the development of classical reliability methods is offered, followed by first- and second-order approximations and extensions, numerical integration, and simulation methods, all developed to address difficulties encountered when classical methods are applied to realistic structural systems. Another study [26] demonstrated that variance reduction techniques are capable of generating a wide range of solutions with high precision and satisfactory computational efficiency.

Such computational progress introduces promising possibilities to optimize design solutions and to reduce uncertainty in structural reliability assessments without compromising the target reliability levels recommended in structural codes, as in EN 1990:2002 + A1:2005 + A1:2005/AC:2010 [27] and, more recently, in its revised version EN 1990:2023 [28]. Concurrently, multiple uncertainty quantification platforms specifically developed to tackle structural reliability problems have been made publicly available to support and motivate engineering practitioners and scientific research communities embracing a probabilistic-based rationale in structural design. For example, the TesiproV software package [29]—an open-source package for structural reliability assessments developed by the Hochschule Biberach University of Applied Sciences and RWTH Aachen (both in Germany) in the free software environment R [30]—was released in 2022 [26,31]. Other examples are the Feasible Reliability Engineering Tool (FREeT) [32] and the UQLab [33]. It is expected that new software platforms will emerge over the coming years due to the predominance of data science and scientific computing in all fields of research and engineering applications [25].

Given such developments, it is relevant to investigate to what extent the recently introduced provisions of Annex A are compatible with the use of existing reliability-based approaches and what implications might be inherent in the design of concrete structures. This analysis is vital for practitioners to be aware of the limitations of the new provisions in Annex A as well as their potential in order to consciously comply with the principles of reliability and economy expected in the design of new concrete structures. On these grounds, this investigation follows a preliminary analysis described in [34]. Section 2 and Section 3 of this manuscript focus on the approaches to adjust partial safety factors and their fundamentals. Through a numerical analysis offered in Section 4, different structural reliability levels are compared, namely the results attained with the use of the simplified method included in Annex A of EN 1992-1-1:2023 and those resulting from the use of more advanced reliability-based methods. The manuscript provides a discussion on the possible implications for practical structural problems. Section 5 offers the main conclusions of this investigation, and closes this manuscript with an outlook on future research directions.

2. Methods: Partial Safety Factors Through the Method in Annex A of EN 1992-1-1:2023

2.1. Method in Annex A of EN 1992-1-1:2023

Annex A of EN 1992-1-1:2023 [7] offers a simplified method to adjust partial safety factors for the resistance side . The value is attained from the ratio between the characteristic values and the design values of the resistance side on the basis of the provisions offered in EN 1990:2002 + A1:2005 + A1:2005/AC:2010 [27] (Equation (1)):

with the index referring to material properties, thereby concerning steel reinforcement , concrete , and shear and punching shear without shear reinforcement . In Equation (1), the term refers to the sensitivity factor for resistance (reference value equal to 0.8 according to Table A.4 (NDP) of Annex A in EN 1992-1-1:2023). The term refers to the target value for the reliability index, which, according to Table A.4 (NDP) of Annex A, is equal to 3.8 for persistent or transient design situations over a 50-year design period. The term represents the coefficient of variation for concrete , for steel reinforcement , or for shear and punching shear (without shear reinforcement) (Equations (2), (3), or (4), respectively). According to EN 1990:2023, Equations (2)–(4) can be used for a value smaller than 0.20.

The term corresponds to the bias factor for concrete , for steel reinforcement , or for shear and punching shear (without shear reinforcement) (Equations (5), (6), and (7), respectively).

As briefly introduced in Section 1, Annex A includes a set of stochastic models for relevant basic variables involved on the resistance side. These models are defined in terms of bias factors and coefficients of variation . An extract of this data is offered in Table 3. Note, however, that no distribution type is included in Annex A. The premises adopted for the specification of these stochastic models are mostly described in the [5].

Table 3.

Stochastic models assumed for the calibration of proposed in EN 1992-1-1:2023 [7] according to Table 4.3 (NDP).

From Equation (1), the reliability index is estimated as

2.2. Considerations on the Fundamentals of the Method in Annex A of EN 1992-1-1:2023

2.2.1. Annex D of EN 1990:2002 + A1:2005 + A1:2005/AC:2010

The method offered in Annex A of EN 1992-1:2023 (Equation (1)) is streamlined from the procedure included in Annex D of EN 1990:2002 + A1:2005 + A1:2005/AC:2010 [27]. The code offers a procedure to determine the partial safety factor for the resistance side, in which experimental data is compared to the empirical values estimated for the resistance model. The overarching procedure entails several steps, as listed in the Appendix A section of this manuscript (Table A1).

In order to use the Annex D procedure, a resistance function should be derived, which is denoted as

Here, the vector of the basic variables may refer, for example, to realizations of concrete compressive strength, yield strength, or geometrical properties.

In the procedure, the theoretical estimate is compared to the experimental one , which is, in principle, based on numerical (advanced FEM-analyses) or physical (laboratory) test results [35]. The procedure considers possible deviations due to random and model uncertainties. To account for the relationship between the theoretical and the experimental estimates, the resistance function expressed in Equation (9) may be rewritten with a correction factor :

Furthermore, approximations about the moments of distributions of basic variables can be found by expansion in a Taylor series about the mean values [35]. Considering that the Taylor series is truncated after the linear terms, i.e.,

the first-order mean value and the coefficient of variation of the resistance are determined through Equations (12) and (13), respectively:

Note that Equation (13) is based on the assumption that the basic variables are stochastically independent and are obtained from the truncated series of Equation (11).

Annex D explicitly allows for a simplification of the general procedure, where the resistance function is described by a simple product function:

with the random variable referring to the error term (i.e., model uncertainties). For Equation (14), the mean value and the variance can be estimated through Equations (15) and (16), respectively.

As is implicit from the general procedure, the term refers to the coefficient of variation of the error term (i.e., model uncertainties) . In turn, the term refers to the coefficient of variation of the basic variables . Equation (17) combines the effect of scatter due to design model and scatter due to the basic variables:

with = . The code allows to simplify Equation (17) if the coefficients of variation and are small:

If a large number of tests are available ( > 100), the design value of the resistance should satisfy the following condition:

with being the design fractile factor for → ∞ (this value is offered in Annex D: = 3.04). The term is expressed as

In this way, the design value of the resistance considers both uncertainties—the one due to the scatter of the basic variables and the one related to simplifications introduced in the design model [35]. It also corresponds to the selected reliability level according to consequence classes and corresponding reliability classes.

By assuming = 1.0 and = · in Equation (19), the reliability index can be estimated as

Equation (21) can be extended to Equation (24)

with referring to the nominal values of the basic input variables. Note that, for coefficients of variation smaller than 0.20, the expression Q can be expressed by with a deviation of less than 1%. The approximated value is estimated as

By comparing the estimation of the reliability index through the approach proposed in Annex A (Equation (8)), only the second leg of Equation (25) is different. Note that, for a sensitivity factor of 0.8 and for a value smaller than 0.2, the second leg results are smaller than 0.125. Yet, Equation (8) is still a simplification of Annex D and leads to higher reliability indices .

2.2.2. Mean Value First-Order Second Moment

The basis of the approach offered in Annex D of EN 1990:2002 + A1:2005 + A1:2005/AC:2010 [27] is the Mean Value First-Order Second Moment (MVFOSM) method. The MVFOSM method was proposed by Freudenthal in the 1950s [36] and was utilized to derive early versions of reliability-based design formats (e.g., [37,38,39,40]). In a nutshell, the MVFOSM method is the simplest and least expensive reliability-based technique that belongs to the family of First-Order Reliability Methods (FORMs). The method is based on the first-order Taylor series approximation of the limit state function , which is linearized at the mean values of the basic variables (i.e., the derivatives of the function are at the mean values) (e.g., [39,41,42,43,44,45,46]):

The mean value is determined as

The coefficient of variation is estimated as

with the variance being defined as

The reliability index results as

Nonetheless, the MVFOSM method is known to have two main limitations (e.g., [39,41,42,43,44,45,46]). First, the results are only exact (i.e., “truly” accurate) for linear functions since the Taylor approximation is conducted at the mean value of the joint density function of the basic variables, In case the function is highly nonlinear, a linear approximation to such nonlinear function introduces an integration error and leads to less accurate estimations of the mean and variance of the limit state function. The accuracy associated with the estimated mean and variance deteriorates rapidly as the degree of nonlinearity of the limit state function increases (e.g., [39,41,42,43,44,45,46]).

Second, the MVFOSM method has an invariance problem (e.g., [39,41,42,43,44,45,46]). The results produced by an MVFOSM fail to remain constant under different but mathematically equivalent formulations of the limit state function. This is a problem not only for nonlinear limit state functions but also for certain linear forms [44]. This problem is illustrated through the basic example offered in Table 4, where it can be observed that, for a mathematically equivalent function, three distinct reliability indices are obtained when they are determined with the MVFOSM method. By calculating the reliability index according to an Advanced First-Order Reliability Method (A-FORM) (in this case, the algorithm of Hasofer and Lind [37] was adopted; see Section 3), the invariant reliability problem appears to be tackled.

Table 4.

Illustration of the invariance problem in the MVFOSM.

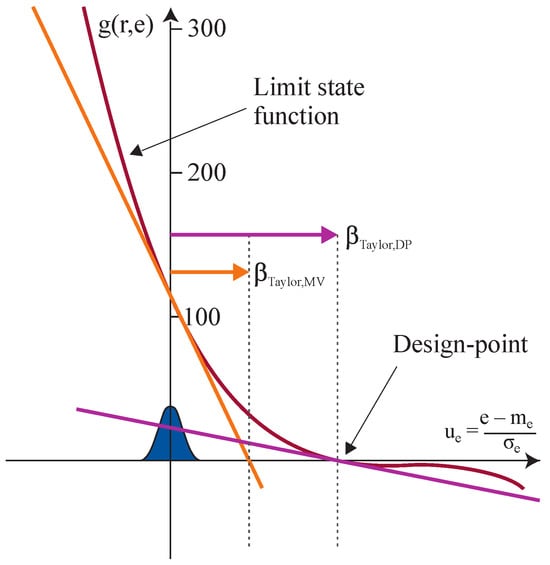

The challenges around the MVFOSM formulation are symbolically illustrated in Figure 1 for the simple case representing the basic variables and in which = − − 2 (see assumptions for the basic variables in Table 4). As explained, the Taylor approximation in the MVFOSM method is at the mean value, which is the origin in the standard normal space. Alternatively, when using an A-FORM (in this case, the algorithm of Hasofer and Lind [37] was also utilized), the Taylor approximation is at the so-called “design-point” (see Section 3). As observed in Figure 1, the approximation at the mean value introduces an integration error, which can be expressive in dependency of the curvature of the function. In this case, the determined with an MVFOSM is smaller than the computed with an A-FORM method, thereby potentially leading to more conservative design solutions. Note, however, that a distinct limit state function with a different curvature may change the trend of the estimated structural reliability level.

Figure 1.

Side view of the limit state function = − − 2 (see assumptions for the basic variables in Table 4) and Taylor approximations according to MVFOSM at the mean value and A-FORM at the design-point.

3. Methods: Adjusting Partial Safety Factors Through Advanced Reliability-Based Methods

In structural engineering, the use of advanced reliability-based methods—commonly designated as Level II and Level III methods—is not a recent topic and is thoroughly covered in the literature (e.g., [3,25,42]). Yet, for the sake of clarity, a brief overview of the most common methods is offered in this section.

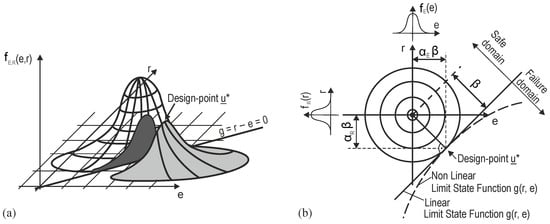

In a nutshell, Level II methods consist of approximating the limit state function to a first- or second-order function using First- or Second-Order Reliability Method (FORM or SORM, respectively). As described in Section 2, the MVFOSM method [36] is the most basic approach belonging to the family of FORM methods. However, to tackle the invariant reliability problem in MVFOSM, Hasofer and Lind [37] proposed an A-FORM, where the reliability index is defined as the shortest distance from the origin of reduced variables to the limit state surface in the standard normal space [39]. This method entails an iterative and linear approximation to the limit state function (i.e., the term first-order), and its linearization occurs around the most probable failure point—so-called design-point u* (Figure 2a,b). The computational procedure of the method can be summarized in the following steps (e.g., [41]):

Figure 2.

(a) Joint distribution density for two independent variables in the function = and (b) respective projection of joint distribution density (adapted from [3,27,44,47,48,49]).

- The basic input variables are transformed using probabilistic transformation methods to the standard Gaussian image space. For the simplest case, when the two variables r (resistance) and e (load) are involved, the transformation is illustrated in Figure 2b.

- Then, the transformed image failure surface is approximated through a Taylor series expansion by a tangent hyperplane at the projection point by assuming suitable regularity of the failure surface at this point. The nearest point on the failure surface is located by iteration. This is the design-point u*. The efficiency of the method depends on the algorithm utilized for the location of the design-point u*, which leads to the following optimization problem:In addition to the Hasofer and Lind [37] algorithm, the Rackwitz–Fiessler algorithm [50] and the NLPQL algorithm of Schittkowski [51], among others, are valid first-order calculation approaches.

- When the design-point u* is located, the probability of failure is assessed throughwith corresponding to the integral of the standard normal distribution. The distance from the origin—labeled as the reliability index —is then determined as

Follow-up techniques based on SORM emerged to improve the accuracy of A-FORM methods. They are particularly relevant for strongly nonlinear limit state functions (e.g., [52]). SORM methods consist of approximating the limit state surface at the design-point u* by a second-order surface, which enables a better estimate of the probability of failure than using a single linear approximation at the global minimum distance point. These were developed by numerous academics, e.g., Breitung [53], Tvedt [54], and Hochenbichler et al. [55].

Level III methods are those that enable an even more accurate estimation of the probability of failure than those determined with Level II methods. Here, the safety verification is carried out with probabilistic methods with full consideration of the distribution functions of the basic variables and the exact limit state functions. To this end, a multi-dimensional integration of the function might be performed by means of direct integration by simplifying the integration through transforming the integral to a multi-normal joint probability density function or by applying numerical integration (e.g., Crude Monte Carlo simulations) [3,26,38]. These techniques are considered simple and robust, enabling handling any limit state function independent of its complexity [56]. The efficiency of Crude Monte Carlo simulation in its standard form does not depend on the dimension of the random variable space [56]. This technique is deemed accurate thanks to the strong law of large numbers and the central limit theorem if infinite computing budget is available. However, for complex structural problems, these simulations can demand considerable computational power and be rather time-consuming (e.g., [3,26,38,45]). To overcome such drawbacks, variance reduction techniques can reduce the variance (i.e., the error) of the estimator to obtain an accurate estimator in comparison to the Crude Monte Carlo estimator at the same computational costs (e.g., [57]). In principle, the computational cost of a sample run is reduced and the accuracy is maintained by using the same number of runs [45]. A wide range of variance reduction techniques are now available, such as Adaptive Sampling (e.g., [58,59,60]), Line Sampling (e.g., [61,62]), and Conditional Expectation techniques, including Directional Simulation [63] and Axis-Orthogonal Simulation [61], just to name a few. Albeit not particularly modern, Monte Carlo Importance Sampling remains one of the most well-established variance reduction techniques utilized to solve structural reliability problems either in its classic form (e.g., [41]) or through further algorithm adjustments, such as Sequential Importance Sampling [64]. Also, the Subset Sampling (SuS) technique has seen growing acceptance for exhibiting high precision and computational efficiency in the calculation of small failure probabilities and for being independent of prior knowledge obtained from simplified reliability techniques (e.g., first-order approximation techniques) (e.g., [65]).

4. Numerical Analysis

4.1. Numerical Example 1

In this numerical example, the following equation of a product form was considered:

The stochastic models for the basic variables are summarized in Table 5. The assessment of this numerical example followed the assumption that the basic variables are characterized by a normal distribution. Additionally, a hypothetical partial safety factor equal to 1.60 was adopted. The probability of failure and the corresponding reliability index were estimated according to distinct methods. Equation (1) was utilized for the method proposed in Annex A of EN 1992-1-1:2023. Note that, according to EN 1990:2002 + A1:2005/AC:2010 [27], Equation (1) can be employed for smaller than 0.20, as demonstrated in Table 5. For the application of Equation (1), a sensitivity factor of 0.8 was considered, which is a reference value given in Table A.4 (NDP) of Annex A and in EN 1990:2002 + A1:2005/AC:2010. Equation (25) was utilized for the calculation according to Annex D of EN 1990:2002 + A1:2005/AC:2010. The assessment on the basis of A-FORM [37] and MC-IS (e.g., [41]) considered Equations (32) and (33), respectively.

Table 5.

Numerical example 1: stochastic models for the basic variables.

The results listed in Table 6 demonstrate that, under the assumption of a normal distribution, the calculation according to the method proposed in Annex A of EN 1992-1-1:2023 leads to a reliability index of 4.29, the highest value of the entire set of results. The calculation according to Annex D of EN 1990:2002 + A1:2005/AC:2010 yields a slightly smaller value: = 4.18. This variation is explained by the second leg of Equation (25), which is not considered in the method proposed in Annex A (Equation (1)). The calculation according to A-FORM generates a further reduced value ( = 3.66), and the evaluation with the MC-IS leads to the smallest value of the entire scope of methods ( = 3.57). The difference between the maximum and minimum values is 16.8%.

Table 6.

Numerical example 1: comparison of probabilities of failure and reliability indices .

4.2. Numerical Example 2

Let us now assume the same Equation (34) but with distinct stochastic models for the basic variables , , and (Table 7). As indicated in Table 7, the combined coefficient of variation is smaller than the limit value established in EN 1990:2002 + A1:2005/AC:2010 [27] equal to 0.20. The same hypothetical partial safety factor equal to 1.60 was considered. The results listed in Table 8 indicate that the method proposed in Annex A yields the highest value generated by the whole set of methods: = 4.98. The results follow the same trend identified in numerical example 1 with a slightly smaller value produced by the provisions of Annex D, with = 4.92. The use of advanced reliability-based approaches led to smaller values ( = 4.62), with the results of the Monte Carlo simulation with Importance Sampling being the smallest of the whole set of results: = 4.56. The reliability indices estimated in this example indicate a difference of 8.43% between the maximum and minimum values, which is smaller than the difference calculated in numerical example 1.

Table 7.

Numerical example 2: stochastic models for the basic variables.

Table 8.

Numerical example 2: comparison of probabilities of failure and reliability indices .

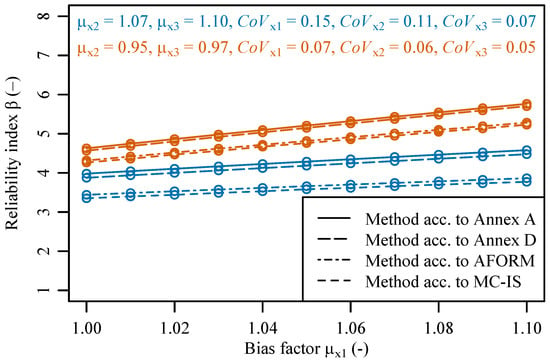

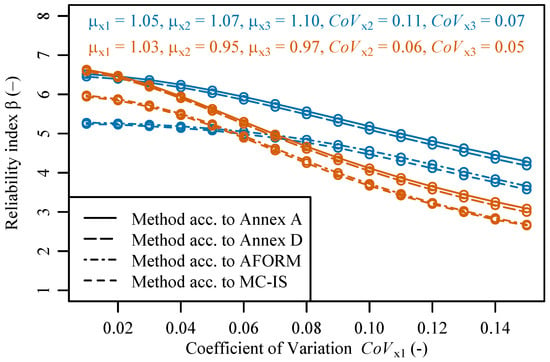

4.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Influence on the Basic Variables

The results of both numerical examples suggest that the stochastic models selected for the basic variables play a critical role in the estimation of the reliability index alongside the methods selected for this estimation (i.e., Annex A, Annex D, A-FORM, and MC-IS). To illustrate such variation, the sensitivity factors of each basic variable were determined for each numerical example, expressing the weight (or importance) of the variable for the estimation of the values (Table 5 and Table 7). In both numerical examples, the basic variable has the highest sensitivity factor: 0.85 in numerical example 1 (Table 5) and 0.70 in numerical example 2 (Table 7). Therefore, the stochastic model of the variable was carefully analyzed.

Figure 3 represents the variation in the bias factor for the variable (i.e., the blue curve corresponds to numerical example 1, and the orange curve corresponds to numerical example 2). In both examples, the bias factors of that were determined with the methods proposed in Annex A of EN 1992-1-1:2023 [7] and Annex D of EN 1990:2002 + A1:2005/AC:2010 [27] led to higher reliability indices than those determined with advanced methods, i.e., A-FORM and MC-IS. In numerical example 1, the difference between these two groups of values (i.e., methods according to Annex A and according to Annex D vs. advanced methods) is approximately constant over the whole range of values considered for the bias factor. For the first group of methods, the values varied approximately between 3.9 and 4.1, while, for the second group of methods, the values varied approximately between 3.3 and 3.7. A similar trend is visible in numerical example 2, where the difference between the values generated by these two groups of methods appears approximately constant over the scope of values allocated to bias factors. Even though this difference is slightly smaller than the one attained in numerical example 1, an increased bias factor for the variable leads to a sharper increase in the values than the trend in numerical example 1. For the first group of methods, the values varied approximately between 4.7 and 5.8, while, for the second group of methods, the values varied approximately between 4.2 and 5.0.

Figure 3.

Sensitivity analysis for the bias factors of the basic variable on the reliability indices determined according to different methods (blue curve corresponds to numerical example 1, and the orange curve corresponds to numerical example 2).

Figure 4 represents the behavior of the coefficients of variation for the variable (i.e., the blue curve corresponds to numerical example 1 and the orange curve corresponds to numerical example 2). Similar to the trend in numerical example 1, the reliability indices generated with the methods prescribed in Annex A of EN 1992-1-1:2023 and in Annex D of EN 1990:2002 + A1:2005/AC:2010 led to higher values than those determined with the advanced methods, i.e., A-FORM and MC-IS. In numerical example 1, the differences between the sets of values generated through these two groups tend to decrease over the whole spectrum of coefficients of variation considered in the analysis. The difference is wider for the coefficients of variation between 0.01 and 0.06. For example, for a coefficient of variation of 0.01, the values vary approximately between 5.2 and 6.5. The difference gradually decreases up to a coefficient of variation of 0.06, with the values being in the range of 5.0 to 6.0, respectively, for the simplified methods (i.e., Annex A and Annex D) and for the advanced methods (i.e., A-FORM and MC-IS). The difference becomes approximately constant up to the coefficient of variation of 0.15, where the values vary between 3.8 and 4.8. Likewise, in numerical example 2, the difference between the sets of values generated through these two groups is approximately constant over the whole range of coefficients of variation. The values generated by the two groups differ by around 0.5-0.6. Yet, a sharp decrease in the trend for values is visible for coefficients of variation higher than 0.06. While for a coefficient of variation of 0.01 the values sit between 6.0 and 6.7, for a coefficient of variation of 0.06, the values sit between 4.9 and 5.4, reaching values in the range of 3.2 to 2.8 when the coefficient of variation for the variable is equal to 0.15.

Figure 4.

Sensitivity analysis for coefficients of variation of the basic variable on the reliability indices determined according to different methods (blue curve corresponds to numerical example 1, and the orange curve corresponds to numerical example 2).

4.4. Discussion

The results of both numerical examples suggest that the application of the method proposed in Annex A of EN 1992-1-1:2023 [7] needs to be carefully interpreted since, based on the adopted premises for the investigated examples, the method leads to the least conservative solutions. Thus, in practical structural problems, such a tendency may lead to unsafe design solutions. For a more detailed analysis and “exact” solutions, a full-probabilistic approach should be adopted in combination with advanced reliability-based approaches.

Nonetheless, it should be emphasized that the method proposed in Annex A of EN 1992-1-1:2023 is easy to utilize, which is especially advantageous for practitioners. The method enables accounting for the individual uncertainties of the basic variables involved in the adjustment of such partial safety factors. When specific material or geometric information becomes available from laboratory or in situ testing, such information can be incorporated in the stochastic models of the basic variables in a simplistic manner. Moreover, for situations where limited data exists, the use of this method might be beneficial. The method offers potential for preliminary assessments before more detailed reliability-based analyses are conducted.

Another point concerns the role of stochastic models for the basic variables. The sensitivity analysis conducted in Section 4.3 demonstrated that, since the method proposed in Annex A considers the bias factors and the coefficients of variation, even minor input changes can greatly affect the resulting values. This analysis highlights the importance of selecting robust models for the most relevant basic variables.

5. Conclusions

From this investigation, the following conclusions are derived:

- The newly revised Annex A of EN 1992-1-1:2023 introduces a rather simple and objective format to adjust partial safety factors for the resistance side (concrete , reinforcing steel , and shear and punching shear without shear reinforcement ). Since it does not require complex probabilistic-based knowledge, its simplicity is an advantage for engineering practitioners.

- Considering the characteristics of the simplified method, it can be argued that it might be an interesting approach to assess the feasibility of adjusting partial safety factors in preliminary analyses.

- Yet, the theoretical foundations of the simplified method in Annex A have some well-known challenges:

- –

- By being a simplified approach of Annex D of EN 1990:2002, the proposed method only applies to design verifications with a specific mathematical formulation (i.e., a function applicable to a product form) and for the cases of small coefficients of variation of basic variables.

- –

- The limitations applied to the MVFOSM method—as one of the most basic reliability-based approaches—are also applicable to the proposed method. Among those limitations are the inaccuracy of the results when applied in nonlinear limit state functions as well as the invariance problems associated with the specific mathematical formulation of limit state functions.

- –

- These limitations may influence the accuracy of the resulting probabilities of failure and reliability indices and have implications on the reliability of the structural component being designed.

- The use of advanced reliability-based methods—such as Level II or Level III methods— has demonstrated efficiency and accurate results in the assessment of structural reliability level and thus for the adjustment of partial safety factors.

- Conditional on the assumptions taken in the numerical examples, the results indicate that the reliability indices obtained from the simplified method can be higher than those attained with advanced reliability-based methods. These results suggest that the use of the simplified method might have to be carefully evaluated when applied to the resolution of real structural problems.

- This investigation demonstrated that the stochastic models for the basic variables should be carefully selected since minor input changes can significantly affect values.

From this investigation, a set of avenues was identified for future work. A thorough verification and validation of the factors offered in Annex A of EN 1992-1-1:2023 is recommended. To this end, individual and combined failure mechanisms and their impact on the proposed values shall be investigated. For those analyses, a wide scope of modern and robust reliability-based techniques and computational platforms are available (e.g., [25,26,29,31,32,33]). Another possibility is to consider more advanced stochastic models for the basic variables through the use of Bayesian updating methods (e.g., [66,67,68,69,70,71,72]). These are particularly useful when experimental data or expert input is available. The inclusion of a methodology that considers the interplay between quality control, stochastic models of the basic variables, reliability levels, and their differentiation and corresponding partial factor reduction can be further investigated (e.g., [68,69,70,71,72]). Further work could be considered concerning existing structures since Annex A of EN 1992-1-1:2023 also includes provisions for existing structures. A specific application could be in the field of structural resilience (e.g., [73,74,75,76,77]). Structural resilience analyses aim at assessing the capacity to withstand and recover efficiently from extreme events [77]. For this reason, the concept of resilience can be applied to preventive assessment. The implications of adjusted partial safety factors on the resilience of a structural component, while maintaining the required safety level, might be investigated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R., T.F. and T.L.; methodology, M.R., T.F. and T.L.; software, T.L.; validation, M.R.; formal analysis, M.R., T.F. and T.L.; investigation, T.F. and T.L.; resources, T.F. and T.L.; data curation, T.F. and T.L.; writing, T.F.; writing—review and editing, M.R., T.F. and T.L.; visualization, T.F. and T.L.; supervision, M.R.; project administration, M.R. and U.W.; funding acquisition, M.R. and U.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the German Committee for Structural Concrete (in German: Deutscher Ausschuss für Stahlbeton e.V. DAfStb) grant number DAfStb-Projekt V521.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No additional data was generated in the scope of this investigation.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the German Committee for Structural Concrete (in German: Deutscher Ausschuss für Stahlbeton e.V., DAfStb) for funding this investigation (DAfStb-Projekt V521: Kritische Bewertung des Hintergrundokuments zu Anhang A in FprEN 1992-1-1:2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Annex D of EN 1990: Standard Procedure for the Safety Analysis of Resistance Functions

Table A1.

Annex D of EN 1990: standard procedure for the safety analysis of resistance functions [27] (table adapted from [35]).

Table A1.

Annex D of EN 1990: standard procedure for the safety analysis of resistance functions [27] (table adapted from [35]).

| Steps | Description | Formulae |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Set up the resistance function | = (, , …, ) |

| Product function: = · · = (, , …, ) · | ||

| Step 2 | Compare experimental and theoretical values | Graphical representation of experimental vs. theoretical results (*) |

| Step 3 | Estimate mean value of correction factor b | = / |

| Step 4 | Estimate coefficient of variation of the error | = /( · ) |

| = ln () | ||

| = 1/(n − 1) · ( − | ||

| = | ||

| Step 5 | Analyze compatibility, i.e., if the resistance function is acceptable | - |

| Step 6 | Determine coefficient of variation | = → = 1/ · ()/∂ |

| of the basic variables | Specific for product function: = ( + 1) · ( ( + 1) ) − 1 | |

| For small values of and , the term can be determined as | ||

| = + → = | ||

| Step 7 | Determine characteristic value of the resistance | = ; = |

| Q = | ||

| For < 100: = · () · exp ( · · − · · − 0.5 · ) | ||

| For ≥ 100: = · () · exp ( · Q − 0.5 · ) |

(*) The theoretical estimate is compared to the experimental one , which is based on numerical (advanced FEM analyses) or physical (laboratory) test results.

References

- Vrouwenvelder, A.; Maljaars, J.; Dimova, T.; Sousa, M.; Marková, J.; Mancini, G.; Kuhlmann, U.; Taras, A.; Jockwer, R.; Jäger, W.; et al. Reliability Background of the Eurocodes: Support to the Implementation, Harmonization and Further Development of the Eurocodes; Joint Research Centre EC: Luxembourg, 2024; pp. 1–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Ruiz, M.F.; Muttoni, A. Considerations on the partial safety factor format for reinforced concrete structures accounting for multiple failure modes. Eng. Struct. 2022, 264, 114442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchers, R.E.; Beck, A.T. Structural Reliability Analysis and Prediction; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novák, L.; Červenka, J.; Červenka, V.; Novák, D.; Sỳkora, M. Comparison of advanced semi-probabilistic methods for design and assessment of concrete structures. Struct. Concrete 2023, 24, 771–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttoni, A. Background Document to 4.3. 3 and Annex A, Partial Safety Factors for Materials; Background Document for FprEN 1992-1-1; Technical Report, CEN/TC250/SC2/WG1/TG6 (Report EPFL-IBETON 16-06-R11); EPFL Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2021.

- Yu, Q. Reliability Analysis and Partial Safety Format Calibration Considering the Characteristics of the Resistance of Reinforced Concrete Structures; Technical Report; EPFL: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2023.

- EN 1992-1-1:2023; Design of Concrete Structures—Part 1-1: General Rules and Rules for Buildings. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- Glock, C.; Schnell, J.; Weber, M. Bauen im Bestand. In Konstruktiver Ingenieurbau und Hochbau: Technik-Organisation-Wirtschaftlichkeit; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 559–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.; Caspeele, R.; Schnell, J.; Glock, C.; Botte, W. Das neue fib Bulletin 80—Teilsicherheitsbeiwerte für die Nachrechnung bestehender Massivbauwerke. Beton Stahlbetonbau 2018, 113, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 13670: 2010; Execution of Concrete Structures. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2010.

- EN 1992-1-1:2004 + AC:2010; Design of Concrete Structures—Part 1-1: General Rules and Rules for Buildings. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2011.

- EN 13791: 2019; Assessment of In-Situ Compressive Strength in Structures and Precast Concrete Components. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2010.

- Feiri, T.; Schulze-Ardey, J.P.; Wiens, U.; Ricker, M.; Hegger, J. A Guideline for Probability-Based Structural Design: Cornerstones and Principles. In 20th International Probabilistic Workshop; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantidis, D.; Tanner, P.; Holicky, M.; Madsen, H.O.; Sykora, M. On reliability assessment of existing structures. Struct. Saf. 2024, 113, 102452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 13822:2010; Bases for Design of Structures—Assessment of Existing Structures. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- DIN CEN/TS 17440:2020-10; Assessment and Retrofitting of Existing Structures; German Version CEN/TS 17440:2020. Beuth: Berlin, Germany, 2020.

- International Federation for Structural Concrete (fib). Partial Factor Methods for Existing Concrete Structures; Bulletin 80; Recommendation, fib Task Group 3.1; fib CEB-FIB: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Diamantidis, D.; Holickỳ, M. Innovative Methods for the Assessment of Existing Structures; Czech Technical University, Klokner Institute: Prague, Czech Republic, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- International Federation for Structural Concrete (fib). fib Model Code for Concrete Structures 2020 (MC2020); fib CEB-FIB: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Orcesi, A.; Diamantidis, D.; O’Connor, A.; Palmisano, F.; Sykora, M.; Boros, V.; Caspeele, R.; Chateauneuf, A.; Mandić Ivanković, A.; Lenner, R.; et al. Investigating partial factors for the assessment of existing reinforced concrete bridges. Struct. Eng. Int. 2024, 34, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küttenbaum, S.; Braml, T.; Heinze, M.; Kainz, C.; Stettner, C.; Taffe, A. Reliability and partial factor-based assessment of a highway bridge supported by nondestructive testing. Struct. Concr. 2025, 26, 5535–5554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainz, C.; Braml, T.; Küttenbaum, S. Recent developments in the research project “ZfPStatik” for a guideline on inspection-supported reliability assessment of existing bridges in Germany. ce/papers 2025, 8, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainz, D.I.C.; Küttenbaum, I.S.; Maack, I.S.; Taffe, I.A.; Kotz, D.I.P.; Reinke, D.I.K.D.; Keuser, I.M.; Soukup, M.S.A.; Schulze, I.S. Recent findings of the research project “ZfPStatik” on inspection-supported reliability assessment of existing bridges in Germany. In 14th Japanese German Bridge Symposium; Förderverein Konstruktiver Ingenieurbau der UniBw München e. V.: Munique, Germany, 2025; pp. 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özlü, C.; Küttenbaum, S.; Kainz, C.; Braml, T.; Taffe, A. Probabilistischer Nachweis einer Spannbetonbrücke—Teil 1: Semiprobabilistische Nachrechnung und probabilistische Modellierung einer einfeldrigen, sechsstegigen Plattenbalkenbrücke. Beton Stahlbetonbau 2024, 119, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingwood, B.; Maes, M.; Bartlett, F.M.; Beck, A.T.; Caprani, C.; Der Kiureghian, A.; Dueñas-Osorio, L.; Galvão, N.; Gilbert, R.; Li, J.; et al. Development of methods of structural reliability. Struct. Saf. 2024, 113, 102474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricker, M.; Feiri, T.; Nille-Hauf, K. Contribution to efficient structural safety assessments: A comparative analysis of computational schemes. Probabilistic Eng. Mech. 2022, 69, 103285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1990:2002 + A1:2005/AC:2010; Basis of Structural Design. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2002.

- EN 1990:2023; Basis of Structural Design. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- Nille-Hauf, K.; Feiri, T.; Ricker, M. TesiproV: Calculation of Reliability and Failure Probability in Civil Engineering; R Package Version 0.9.1; Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN): Biberach, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schulze-Ardey, J.P.; Feiri, T.; Hegger, J.; Ricker, M. Implementation of reliability methods in a new developed open-source software library. In 18th International Probabilistic Workshop; Matos, J.C., Lourenço, P.B., Oliveira, D.V., Branco, J., Proske, D., Silva, R.A., Sousa, H.S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novák, D.; Radoslav, R.; Vořechovskỳ, M. FREeT. Feasible Reliability Engineering Tool. Version 1.7. 2024. Available online: http://www.freet.cz (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Marelli, S.; Sudret, B. UQLab: A framework for uncertainty quantification in Matlab. In Vulnerability, Uncertainty, and Risk: Quantification, Mitigation, and Management; ASCE Library: Zürich, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 2554–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiri, T.; Lux, T.; Wiens, U.; Ricker, M. Method for the adjustment of partial safety factors for materials in Annex A of EN 1992-1-1:2023: Practical implications. ce/papers 2025, 8, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tankova, T.; da Silva, L.S.; Marques, L.; Rebelo, C.; Taras, A. Towards a standardized procedure for the safety assessment of stability design rules. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2014, 103, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenthal, A.M. Safety and the probability of structural failure. Trans. Am. Soc. Civ. Eng. 1956, 121, 1337–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasofer, A.M. An exact and invarient first order reliability format. J. Eng. Mech. Div. Proc. ASCE 1974, 100, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditlevsen, O.; Madsen, H.O. Structural Reliability Methods; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1996; Volume 178. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaidis, E.; Burdisso, R. Reliability based optimization: A safety index approach. Comput. Struct. 1988, 28, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, C.A. A probability-based structural code. J. Proc. 1969, 66, 974–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricker, M.; Feiri, T.; Nille-Hauf, K.; Adam, V.; Hegger, J. Enhanced reliability assessment of punching shear resistance models for flat slabs without shear reinforcement. Eng. Struct. 2021, 226, 111319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shittu, A.A.; Kolios, A.; Mehmanparast, A. A systematic review of structural reliability methods for deformation and fatigue analysis of offshore jacket structures. Metals 2020, 11, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubišić, M.; Ivošević, J.; Grubišić, A. Reliability analysis of reinforced concrete frame by finite element method with implicit limit state functions. Buildings 2019, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, A.S.; Collins, K.R. Reliability of Structures; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.K.; Canfield, R.A.; Grandhi, R.V. Reliability-Based Structural Design; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Haldar, A.; Mahadevan, S. First-order and second-order reliability methods. In Probabilistic Structural Mechanics Handbook: Theory and Industrial Applications; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1995; pp. 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JCSS Probabilistic Model Code (PMC). 2001. Available online: https://www.jcss-lc.org/jcss-probabilistic-model-code/ (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Zilch, K.; Zehetmaier, G. Bemessung im Konstruktiven Betonbau: Nach DIN 1045-1 und DIN EN 1992-1-1; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Spaethe, G. Die Sicherheit Tragender Baukonstruktionen; VEB: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rackwitz, R.; Fissler, B. Structural reliability under combined random load sequences. Comput. Struct. 1978, 9, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schittkowski, K. NLPQL: A Fortran subroutine solving constrained nonlinear programming problems. Ann. Oper. Res. 1986, 5, 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.G.; Ono, T. A general procedure for First/Second-order reliability method (FORM/SORM). Struct. Saf. 1999, 21, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitung, K. Asymptotic approximations for probability integrals. Probabilistic Eng. Mech. 1989, 4, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tvedt, L. Distribution of quadratic forms in normal space—Application to structural reliability. J. Eng. Mech. Div. Proc. ASCE 1990, 116, 1183–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenbichler, M.; Gollwitzer, S.; Kruse, W.; Rackwitz, R. New light on first-and second-order reliability methods. Struct. Saf. 1987, 4, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, I.; Breitung, K.; Straub, D. Reliability sensitivity analysis with Monte Carlo methods. In Proceedings of the ICOSSAR 2013, New York, NY, USA, 16–20 June 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, Y. Observations on applications of Importance Sampling in structural reliability analysis. Struct. Saf. 1991, 9, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, C.G. Adaptive Sampling—An iterative fast Monte Carlo procedure. Struct. Saf. 1988, 5, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, S.K.; Beck, J.L. A new adaptive Importance Sampling scheme for reliability calculations. Struct. Saf. 1999, 21, 135–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, N.; Song, J. Cross-entropy-based adaptive Importance Sampling using Gaussian mixture. Struct. Saf. 2013, 42, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenbichler, M.; Rackwitz, R. Improvement of second-order reliability estimates by Importance Sampling. J. Eng. Mech. Div. Proc. ASCE 1988, 114, 2195–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsourelakis, P.S.; Pradlwarter, H.J.; Schueller, G.I. Reliability of structures in high dimensions. Part I: Algorithms and applications. Probabilistic Eng. Mech. 2004, 19, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditlevsen, O.; Melchers, R.E.; Gluver, H. General multi-dimensional probability integration by Directional Simulation. Comput. Struct. 1990, 36, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, I.; Papadimitriou, C.; Straub, D. Sequential Importance Sampling for structural reliability analysis. Struct. Saf. 2016, 62, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, S.K.; Beck, J.L. Estimation of small failure probabilities in high dimensions by Subset Simulation. Probabilistic Eng. Mech. 2001, 16, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rackwitz, R. Predictive distribution of strength under control. Matériaux Constr. 1983, 16, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiri, T.; Kuhn, S.; Wiens, U.; Ricker, M. Updating the prior parameters of concrete compressive strength through Bayesian statistics for structural reliability assessment. Structures 2023, 58, 105636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspeele, R.; Taerwe, L. Numerical Bayesian updating of prior distributions for concrete strength properties considering conformity control. Adv. Concr. Constr. 2013, 1, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspeele, R.; Sykora, M.; Taerwe, L. Influence of quality control of concrete on structural reliability: Assessment using a Bayesian approach. Mater. Struct. 2014, 47, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiri, T.; Lux, T.; Schulze-Ardey, J.; Hegger, J.; Claßen, M.; Ricker, M. Statistical procedures to quantify the influence of quality control in component properties: A methodology for structural safety assessments. ce/papers 2025, 8, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiri, T.; Lux, T.; Schulze-Ardey, J.; Hegger, J.; Claßen, M.; Ricker, M. Using Operating Characteristic curves to quantify the effect of quality control on geometric properties in structural members: Use case for structural reliability assessments. ce/papers 2025, 8, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze-Ardey, J.P.; Lux, T.; Feiri, T.; Hegger, J.; Claßen, M.; Ricker, M. The potential of quality control in structural safety: A case study on shear resistance models without shear reinforcement. ce/papers 2025, 8, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameshwar, S.; Forcellini, D.; Barbosa, A.R. Assessment of building recovery functions for local and global resilience assessment to tsunamis. Resilient Cities Struct. 2025, 4, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcellini, D.; Kalfas, K.N. A framework to quantify the impact of deterioration on the seismic resilience of structures. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2025, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murao, O. Recovery curves for housing reconstruction from the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and comparison with other post-disaster recovery processes. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 45, 101467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocchini, P.; Decò, A.; Frangopol, D.M. Probabilistic functionality recovery model for resilience analysis. In Bridge Maintenance, Safety, Management, Resilience and Sustainability, Proceedings of the Sixth International IABMAS Conference, Stresa, Lake Maggiore, Italy, 8–12 July 2012; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau, M.; Chang, S.E.; Eguchi, R.T.; Lee, G.C.; O’Rourke, T.D.; Reinhorn, A.M.; Shinozuka, M.; Tierney, K.; Wallace, W.A.; Von Winterfeldt, D. A framework to quantitatively assess and enhance the seismic resilience of communities. Earthq. Spectra 2003, 19, 733–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.