Abstract

The construction industry significantly contributes to global sustainability challenges, producing 30–40 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions and consuming large amounts of natural resources. Pervious concrete has emerged as a sustainable alternative to conventional pavements due to its ability to promote stormwater infiltration and groundwater recharge. However, the absence of fine aggregates creates a highly porous structure that results in reduced compressive strength, limiting its broader structural use. Determining compressive strength traditionally requires destructive laboratory testing of concrete specimens, which demands considerable material, energy, and curing time, often up to 28 days—before results can be obtained. This makes iterative mix design and optimization both slow and resource intensive. To address this practical limitation, this study applies Machine Learning (ML) as a rapid, preliminary estimation tool capable of providing early predictions of compressive strength based on mix composition and curing parameters. Rather than replacing laboratory testing, the developed ML models serve as supportive decision-making tools, enabling engineers to assess potential strength outcomes before casting and curing physical specimens. This can reduce the number of trial batches produced, lower material consumption, and minimize the environmental footprint associated with repeated destructive testing. Multiple ML algorithms were trained and evaluated using data from existing literature and validated through laboratory testing. The results indicate that ML can provide reliable preliminary strength estimates, offering a faster and more resource-efficient approach to guiding mix design adjustments. By reducing the reliance on repeated 28-day test cycles, the integration of ML into previous concrete research supports more sustainable, cost-effective, and time-efficient material development practices.

1. Introduction

One of the most critical global challenges in recent decades is climate change, largely fueled by carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. Among the significant contributors to these emissions is the construction sector, particularly due to the extensive production of cement. Cement manufacturing alone accounts for nearly 10% of global CO2 emissions [1]. With rapid urbanization and infrastructural development, the demand for cement continues to rise, leading to an increase in energy consumption and environmental degradation. In addition to carbon emissions, the construction industry contributes to dust, noise, and chemical pollution, highlighting the urgent need for sustainable alternatives. Recent studies have similarly highlighted the need for more sustainable concrete solutions, particularly through the use of recycled materials and improved mix designs [2].

Pervious concrete [3,4], also known as porous or no-fine concrete, has gained attention as a sustainable construction material due to its unique ability to allow water to infiltrate through its interconnected voids. Comprising cement, coarse aggregates, and minimal or no fine aggregates, pervious concrete enables stormwater management, reduces urban flooding, mitigates the urban heat island effect, and supports groundwater recharge [5]. These benefits position pervious concrete as an environmentally friendly substitute for conventional impermeable pavements, especially in urban areas facing water runoff and scarcity challenges [6].

Despite its environmental advantages, pervious concrete presents challenges in achieving high compressive strength due to its porous structure. Several researchers have explored the trade-off between strength and permeability in mix designs [4,7,8,9]. The relationship between void content and compressive strength remains a central issue in optimizing performance. Traditionally, determining the compressive strength of concrete requires destructive testing of cylindrical specimens. However, with sufficient data on key mix and physical parameters, machine learning models could serve as a form of non-destructive strength estimation [10,11]. Such approaches, if properly validated, have the potential to minimize material waste, reduce testing costs, and enable real-time quality assessment during construction. In the future, data-driven models could complement or even enhance existing non-destructive evaluation methods such as the rebound hammer or ultrasonic pulse velocity by integrating multiple parameters for more accurate strength prediction.

Although ML-based prediction models have been explored in concrete research, existing studies on pervious concrete remain limited in several ways. Many rely on a single machine learning algorithm (commonly ANN or SVR), lack external validation, or fail to incorporate important porosity-related features. Moreover, bias in feature importance analysis is often overlooked, leading to reduced generalizability and limited interpretability. These issues highlight the need for models that are both robust and interpretable, particularly for civil engineering applications where model transparency is valued.

Past studies have highlighted the importance of aggregate classification, water–cement ratio, and binder content in influencing the mechanical and hydraulic properties of pervious concrete [12]. In addition, sustainable enhancements such as the inclusion of additional cementitious materials (SCMs) and recycled aggregates are being evaluated for their long-term performance and environmental benefits [13].

This study addresses these gaps by developing a Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR) model trained on a curated dataset that combines 83 literature-derived mixes with 18 experimentally validated samples. Gradient Boosting was selected for its ability to model complex nonlinear interactions and offer interpretable feature importance rankings, which is beneficial for engineering decision-making. The results provide insights into the practical viability of using data-driven approaches in sustainable material design.

In summary, this research contributes to the broader field of environmentally conscious construction by (i) evaluating the structural performance of pervious concrete under varying water contents, (ii) generating an optimized machine learning model for strength prediction, and (iii) validating these predictions through experimental data. This integrative approach bridges environmental sustainability with technological innovation and serves as a stepping stone toward the development of greener infrastructure.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the detailed methods used in different phases of this proposed work. A thorough exploratory data analysis (EDA) is demonstrated in Section 3, followed by feature importance analysis in Section 4. Section 5 presents and analyzes the obtained results using various machine learning algorithms. Finally, Section 6, Section 7 and Section 8 conclude this paper with a thorough discussion, conclusion, and presentation of future challenges, respectively.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Harmonization

A total of 253 experimental mix designs were extracted from published literature, primarily peer-reviewed journal articles and conference papers.Selection criteria included: (i) availability of essential mix design parameters such as cement content, water to cement ratio (w/c), coarse aggregate size, porosity, and permeability; (ii) compressive strength data measured at a curing age of 28 days; and (iii) clearly reported material types and quantities. Entries with missing or ambiguous values were excluded to ensure consistency.

To harmonize the dataset, all mix proportions were converted to uniform units (e.g., kg/m3), and nomenclature across sources was standardized. Compatibility checks were performed to resolve discrepancies in test methods, material definitions, and data formats. Unconventional mix designs or studies using non-standard testing protocols were omitted to maintain dataset uniformity and improve model reliability.

Preprocessing and initial analysis were conducted in Python 3.13.5 using the Pandas, NumPy, and Scikit-learn libraries. This curated dataset forms the foundation for training and evaluating the machine learning regression models presented in subsequent sections.

2.2. Data Preprocessing

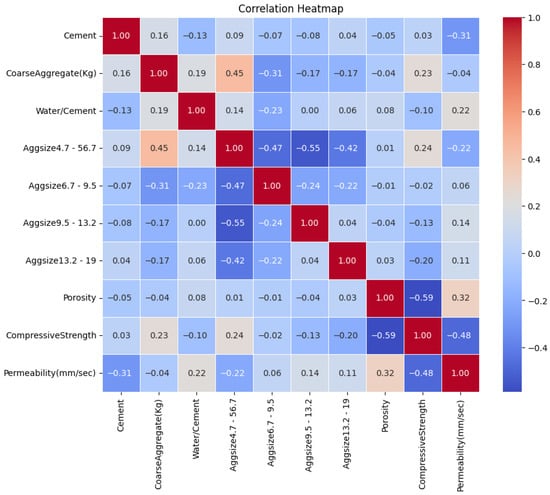

Outlier detection was performed using the interquartile range (IQR) method and verified with box plots. Correlation analysis via heatmaps was used to guide feature selection. Less significant aggregate size categories were removed to improve model simplicity, following the observations of Sonebi et al. [14]. The cleaned dataset was then prepared for modeling.

Figure 1 illustrates the correlation structure among all numerical features prior to feature removal. Compressive strength shows a moderate negative correlation with porosity and a weak negative correlation with the water–cement ratio, both consistent with established material behavior. Permeability exhibits a weak positive association with porosity, reflecting the influence of interconnected voids on infiltration capacity. In contrast, the aggregate size variables display consistently low correlation with compressive strength and high inter-correlation among themselves, indicating redundancy and limited predictive value. Therefore, aggregate size features were removed to simplify the dataset and improve model clarity and generalization.Pearson correlation was used for this analysis, as it is the default method in Pandas and is appropriate for assessing linear relationships among continuous numerical variables.

Figure 1.

Correlation heatmap showing relationships among mix design parameters and output variables.

2.3. Machine Learning Formulation and Model Development

In this study, the prediction of compressive strength is formulated as a supervised regression task, where compressive strength is treated as a continuous output variable and mix-design parameters serve as input features.

The Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR) was selected for its strong capability to model complex, non-linear relationships. Gradient Boosting was chosen because it performs reliably on small-to-medium sized tabular datasets, is robust to noise, and provides interpretable feature importance values, which are useful for understanding the influence of mix parameters in material science applications. In addition to Gradient Boosting, multiple ensemble based machine learning algorithms including Random Forest, Extra Trees, XGBoost, and AdaBoost were incorporated to ensure a comprehensive comparison across different learning paradigms. Ensemble methods are well suited for engineering datasets because they effectively capture non-linear feature interactions, reduce overfitting through model aggregation, and require minimal data preprocessing. Bagging methods such as Random Forest and Extra Trees improve stability by averaging multiple decision trees, while boosting-based models (GBR, XGBoost, AdaBoost) iteratively refine predictions to enhance accuracy. Including both families of models provides a robust evaluation framework and prevents performance conclusions from depending on a single algorithm.

The dataset was divided into 85% for training and 15% for testing. Feature scaling and encoding were applied to standardize the input variables. The GBR model was trained using mean squared error (MSE) as the loss function. To enhance reliability, 7-fold cross-validation was performed. Feature importance values were extracted to assess the influence of each predictor. Model performance was evaluated using R2, MSE, RMSE, MAE, MAPE, and residual analysis. Additional implementation details are provided in Appendix A and Appendix B.

2.4. Experimental Validation

Eighteen pervious concrete mixes were prepared in the laboratory using varying water–cement ratios (0.2 and 0.3) and grades (M10, M15, M20). Materials included OPC 43 cement, 9.5 mm graded coarse aggregates, potable water, and SP430 superplasticizer. The detailed mix proportions and experimental parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Presents the full mix design details for the 18 casted specimens.

The mixes were cast in 150 mm cubes and cured for 28 days. Physical and mechanical tests were conducted:

- Compressive strength: measured using a universal testing machine (IS 10086:1982) [15].

- Porosity: calculated via fluid displacement method.

- Permeability: determined using the simple infiltration method (IRC 44:2017) [16].

The experimental results were compared against the GBR-predicted values to assess model performance and accuracy.

2.5. Laboratory Validation Protocol

To validate the ML model, 18 concrete mixes were prepared and tested in the laboratory as shown in Table 2. These mixes were developed using Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC), standard coarse aggregates (12.5 mm and 10 mm), and consistent mix procedures. All specimens were cured under water for 28 days. Mechanical compaction was applied, and permeability was tested using the falling head method. This experimental dataset, though limited in size, was used to assess generalizability of the model to real-world mixes.

Table 2.

Summarizes the measured weights and timing from multiple trials.

3. Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)

Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) was conducted to explore the underlying patterns, relationships, and anomalies present in the dataset before applying any machine learning algorithms. This step ensured data quality and helped inform the modeling process.

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Basic statistical measures such as mean, median, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum were calculated for all key numerical features as shown in Table 3. These included:

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of mix design parameters in the compiled dataset.

- Cement content (kg).

- Coarse aggregate (kg).

- Water–cement ratio.

- Porosity (%).

- Permeability (mm/s).

- Compressive strength (MPa).

These metrics helped assess the spread and central tendency of each variable.

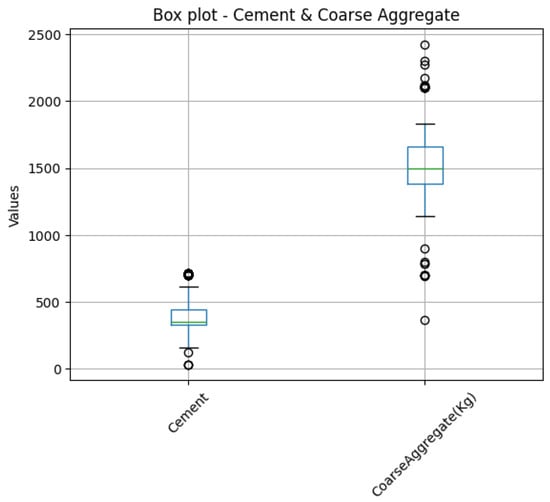

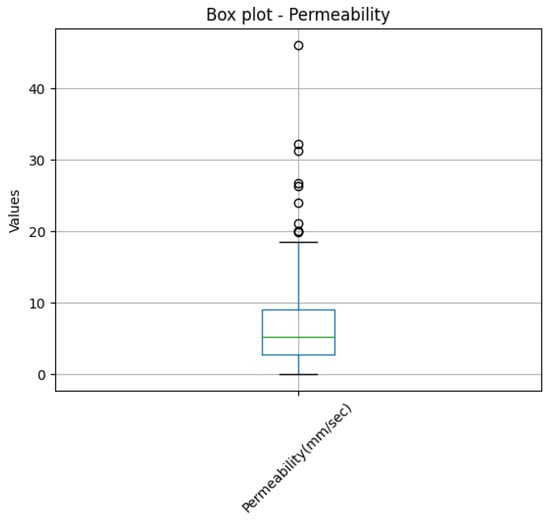

3.2. Box Plot Analysis

Box plots were generated for the key numerical features to examine distribution patterns and identify potential outliers within the compiled dataset. Permeability exhibited a positively skewed distribution with several high-end outliers above 20–30 mm/s, suggesting variability in experimental procedures and aggregate gradations reported in the literature. Cement content and coarse aggregate mass also showed scattered high values, indicating differences in mix proportions across studies. The box plot for compressive strength revealed a broad spread with a few extreme values above 40 MPa, while porosity displayed a similar wide distribution ranging from approximately 2% to 34% as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. These observations highlight the inherent variability in literature-derived datasets, particularly for pervious concrete, where mix composition, compaction effort, and measurement techniques differ across sources. To improve the reliability and consistency of the dataset, outliers were treated using the Interquartile Range (IQR) method. After removing these extreme values, the final dataset contained 226 observations across 10 variables, providing a cleaner and more uniform basis for subsequent exploratory data analysis and machine learning modeling. Table 4 summarizes the descriptive statistics of the physical and strength properties in the compiled dataset.

Figure 2.

Box plot showing the distribution and outliers for compressive strength and porosity.

Figure 3.

Box plot showing the distribution and outliers for permeability.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of physical and strength properties in the compiled dataset.

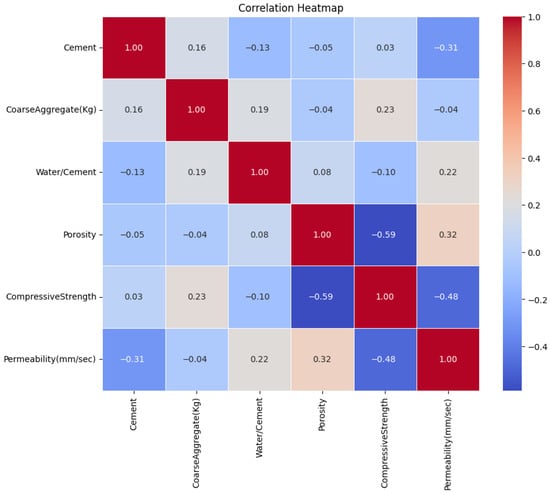

3.3. Correlation Analysis

A correlation heatmap was constructed to visualize the relationships among features. Key findings included:

- Porosity had a strong negative correlation with compressive strength.

- Cement content and coarse aggregate content had a positive influence on strength.

- Water–cement ratio showed a non-linear relationship with strength.

Figure 4 presents the correlation matrix after removing the aggregate size variables. The resulting heatmap shows a clearer and more interpretable relationship among the remaining numerical features. As expected, porosity maintains a strong negative correlation with compressive strength (), reflecting the established inverse relationship between void content and mechanical performance. Permeability exhibits a moderate positive correlation with porosity (), indicating that mixes with higher pore connectivity allow greater water infiltration. Permeability also shows a moderate negative correlation with compressive strength (), further confirming that mixes optimized for flow tend to sacrifice strength.

Figure 4.

Correlation heatmap of input variables after removing the aggregate size variables. Darker blue indicates stronger negative correlation, red indicates positive correlation.

Cement content and water/cement ratio display only weak correlations with the other variables, suggesting that their influence is more indirect and dependent on combined mix proportion effects rather than linear relationships in isolation. Compared to the full feature set, the reduced heatmap demonstrates fewer noisy or redundant associations, providing a more focused and meaningful representation of the dataset. This supports the decision to remove low-impact aggregate size features and retain only the variables with greater relevance to strength prediction and model interpretability. This analysis confirmed the need for non-linear modeling techniques such as Gradient Boosting.

3.4. Preliminary Feature Importance

Using a Random Forest Regressor, feature importance was evaluated before final model development. The most influential predictors of compressive strength were:

- Porosity.

- Water–cement ratio.

- Cement content.

- Coarse aggregate.

These were retained as inputs for the Gradient Boosting model.

3.5. Distribution Visualizations

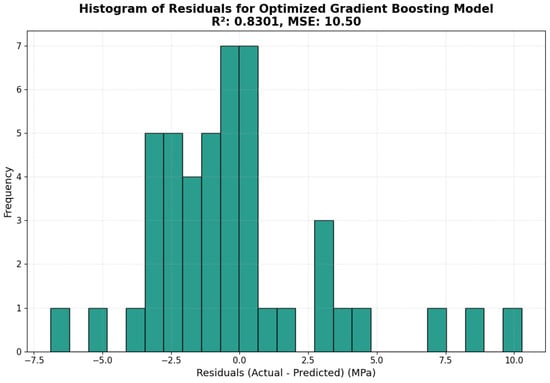

Histograms of continuous variables revealed mostly continuous, slightly skewed distributions. This confirmed that data normalization and outlier removal were appropriate and that the dataset was suitable for regression modeling as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Histogram of residuals for predicted vs. actual compressive strength.

In conclusion, EDA provided valuable insights that guided preprocessing, feature selection, and model choice, ultimately improving prediction accuracy and model robustness.

4. Feature Importance

Feature importance analysis was conducted to identify which input variables had the greatest impact on predicting the compressive strength of pervious concrete. Multiple ensemble regression models were compared to understand how different algorithms interpret variable significance.

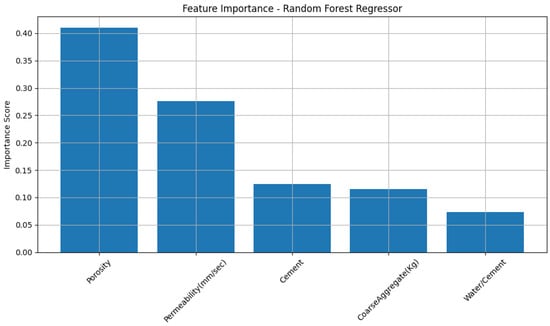

4.1. Random Forest Regressor

The Random Forest model indicated that Porosity and Permeability were the most influential features, followed by Cement content, Coarse Aggregate, and Water/Cement ratio as shown in Figure 6. These results highlight the dominant role of porosity-related parameters in determining compressive strength.

Figure 6.

Feature importance from the Random Forest Regressor model.

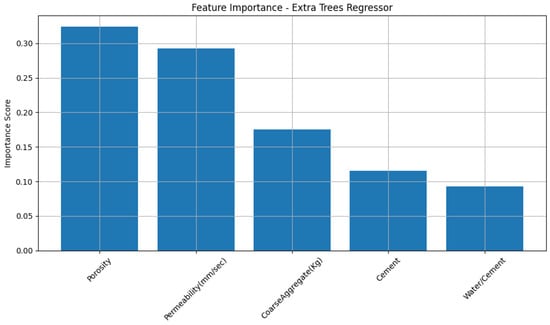

4.2. Extra Trees Regressor

The Extra Trees model produced a similar trend, with Porosity and Permeability again emerging as the top predictors as shown in Figure 7. This consistency across ensemble methods reinforces the reliability of the identified influential parameters.

Figure 7.

Feature importance from the Extra Trees Regressor model.

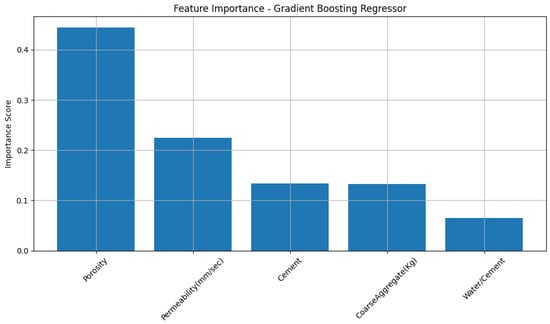

4.3. Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR)

The Gradient Boosting model revealed Porosity as the most dominant factor, contributing over 40% to the prediction. Permeability, Cement content, and Coarse Aggregate followed, while Water/Cement ratio showed the least influence as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Feature importance from the Gradient Boosting Regressor model.

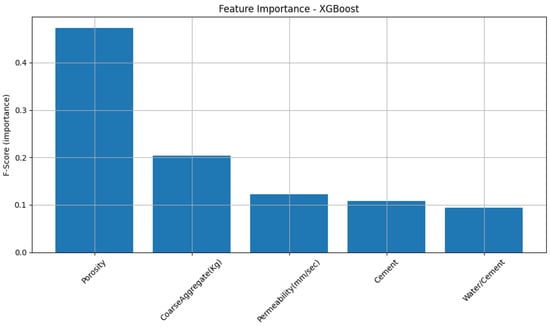

4.4. XGBoost Regressor

The XGBoost model displayed comparable importance trends, with Porosity remaining the most significant feature as depicted in Figure 9. This further validates the correlation between void structure and strength performance in pervious concrete.

Figure 9.

Feature importance from the XGBoost Regressor model.

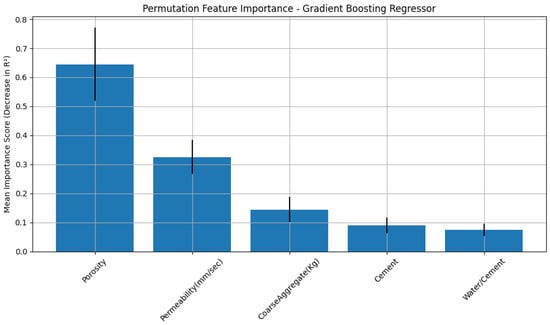

4.5. GBR Permutation Importance

To address the known bias of impurity-based feature importance in tree-based models, permutation importance (Figure 10) was computed for the Gradient Boosting Regressor. This method evaluates the decrease in model performance when each feature is randomly permuted and provides a more robust estimation of feature relevance.

Figure 10.

Permutation importance from the GBR model.

Beyond the numerical rankings produced by the ensemble models, the identified feature-importance pattern is consistent with the established mechanics of pervious concrete. Porosity emerged as the most influential parameter because an increase in void content reduces the effective load-bearing area within the concrete matrix, thereby lowering compressive strength. Permeability exhibited similarly high importance, which is expected since it is governed by the connectivity and size of the pores that also control mechanical performance. Cement content and coarse aggregate size showed moderate influence, reflecting their roles in determining paste thickness, aggregate interlock, and overall structural stiffness of the pervious concrete skeleton. In contrast, the water to cement ratio contributed relatively little to the predictions, which aligns with the low-paste nature of pervious concrete where small variations in w/c have a reduced effect compared with conventional concrete. These physical interpretations confirm that the machine-learning results are coherent with known material behavior and strengthen the scientific validity of the feature importance findings.

Across all ensemble models evaluated Random Forest, Extra Trees, Gradient Boosting, and XGBoost, Porosity consistently emerged as the most influential predictor of compressive strength, followed by Permeability. Cement content, Coarse Aggregate content, and the Water/Cement ratio exhibited comparatively lower influence. The strong agreement among these models highlights the robustness of the observed feature-importance pattern. Furthermore, the permutation importance analysis conducted for the Gradient Boosting Regressor provided an unbiased, model-agnostic validation of these findings. The large decrease in predictive performance when Porosity and Permeability were permuted confirms their dominant role, thereby strengthening confidence in the reliability and stability of the identified key parameters affecting pervious concrete strength.

5. Result Evaluations

This section presents and analyses the experimental results obtained from the compressive strength testing, porosity determination, and permeability evaluation of pervious concrete specimens. The predictive model results based on Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR) are also discussed and compared to the experimental values.

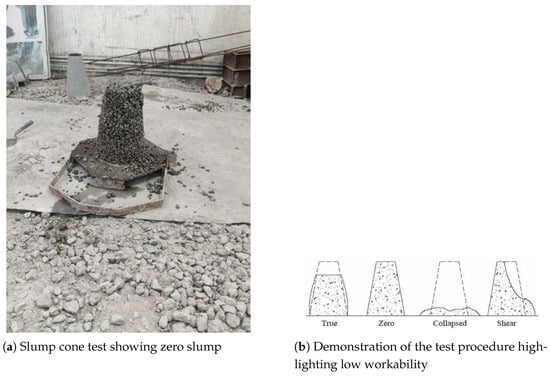

5.1. Workability

The slump test was conducted to evaluate the workability of fresh pervious concrete mixes as shown in Figure 11. Due to its open-graded structure and low water–cement ratio, pervious concrete typically exhibits negligible slump compared to conventional concrete. In this study, all mixes showed zero slump, confirming the low workability characteristic of pervious concrete [17]. Workability was primarily affected by the water content and aggregate size; excessive water caused bleeding, whereas larger aggregates reduced mix cohesion. These results are consistent with the behavior expected from pervious concrete, where permeability and interconnected voids are prioritized over ease of placement.

Figure 11.

Slump test results for pervious concrete mixes.

5.2. Compressive Strength

A total of 18 mixes were tested after 28 days of water curing shown in Table 5. The compressive strength ranged from 10.67 MPa to 18.67 MPa. A lower water–cement ratio (0.2) consistently produced higher strength than 0.3. Figure 12 shows the compressive testing setup used for the cube specimens.

Table 5.

Compressive strength of pervious concrete specimens.

Figure 12.

Compression testing of pervious concrete cube.

5.3. Porosity

Table 6 shows the porosity values ranged from 2.07% to 25.19%. Higher grades with 0.3 w/c ratio showed slightly higher porosity.

Table 6.

Porosity of pervious concrete (Fluid Displacement Method).

5.4. Permeability

Table 7 shows the permeability values ranged between 0.0717 cm/s and 0.2222 cm/s. Most of the of the samples fell within the range for highly permeable concrete.

Table 7.

Permeability of pervious concrete (Simple Infiltration Method).

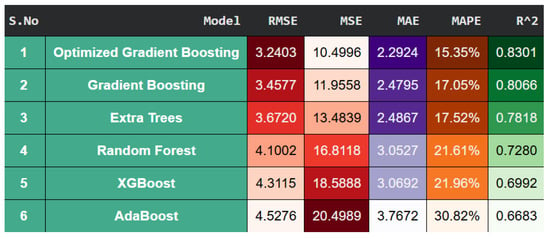

5.5. Model Performance and Validation

A comparative analysis was carried out to evaluate the predictive performance of various ensemble regression models, including Random Forest, Extra Trees, AdaBoost, XGBoost, and Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR). Each model was trained on the same dataset and assessed using statistical performance metrics such as the coefficient of determination (), mean squared error (MSE), and root mean squared error (RMSE). Additionally, mean absolute error (MAE) and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) were included to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of predictive accuracy, especially for capturing error magnitudes in absolute and relative terms. All models achieved satisfactory results, with values ranging between 0.74 and 0.81 as shown in Figure 13, indicating that ensemble learning methods are well-suited for predicting the compressive strength of pervious concrete. However, slight differences were observed in their accuracy and generalization behavior.

Figure 13.

Model performance comparison across ensemble regressors using RMSE, MAE, MAPE, and metrics. The Optimized Gradient Boosting model achieved the best overall performance, with the lowest error values and highest , indicating improved predictive reliability over other models.

The Random Forest and Extra Trees models provided stable predictions but showed mild underfitting tendencies due to their averaging mechanism, which smooths out extreme values and limits the model’s ability to capture complex feature interactions. AdaBoost, on the other hand, exhibited sensitivity to outliers and noise, leading to fluctuations in its performance. XGBoost produced results comparable to Gradient Boosting but required careful parameter tuning to prevent overfitting. Among all tested algorithms, the Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR) achieved the highest predictive accuracy with an optimized value of 0.83 and the lowest RMSE. It also produced the lowest MAE (2.29) and MAPE (15.35%), further validating its performance in both absolute and relative error dimensions. The predicted compressive strengths showed a strong correlation with the experimental values.

The superior performance of the GBR model can be attributed to its sequential learning process, where each weak learner focuses on correcting the residual errors of previous iterations. This iterative boosting approach enables the model to capture complex non-linear relationships between features such as porosity, permeability, and water–cement ratio. Furthermore, the optimized GBR employed fine-tuned hyperparameters including the number of estimators, learning rate, and tree depth identified through a grid search optimization process. These settings allowed the model to achieve an ideal balance between bias and variance, improving both accuracy and robustness. In contrast, other ensemble regressors either relied on random sampling (Random Forest, Extra Trees) or exhibited higher sensitivity to parameter tuning (XGBoost, AdaBoost). As a result, the optimized Gradient Boosting model outperformed all other approaches, providing a reliable and interpretable framework for predicting the compressive strength of pervious concrete.

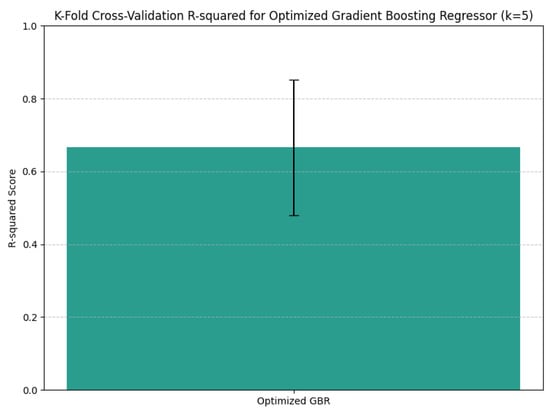

5.6. Cross-Validation Performance

To evaluate the generalizability of the optimized Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR), 5-fold cross-validation was performed. The mean R-squared score across folds was 0.6661, with a standard deviation of 0.1860, indicating moderate variability in performance across different splits of the dataset (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

5-Fold Cross-Validation R-squared Score for Optimized GBR Model.

6. Discussion

The experimental results and machine learning predictions obtained in this study align with the existing literature on pervious concrete, particularly in terms of the inverse relationship between porosity and compressive strength. As observed, the increase in the content while improving permeability consistently led to a reduction in strength [18,19]. This supports the findings of Ribeiro et al. [7]. and Sourabh Rahangdale et al. [8]., who emphasized the trade-off between permeability and structural integrity in pervious concrete.

The application of a Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR) proved effective in capturing the complex non-linear interactions between the mix parameters, such as the water–cement ratio, porosity, and aggregate size. The predictive model achieved a reliable approximation of compressive strength, validating the hypothesis that machine learning can be a powerful tool for predictive analysis in civil materials research [20].

Experimentally, the results confirmed the predictions of the model within an acceptable range, underscoring the robustness of GBR when trained on diverse and well-curated datasets. These findings suggest that integrating ML into concrete design processes can reduce trial-and-error in lab settings, saving time and resources [21].

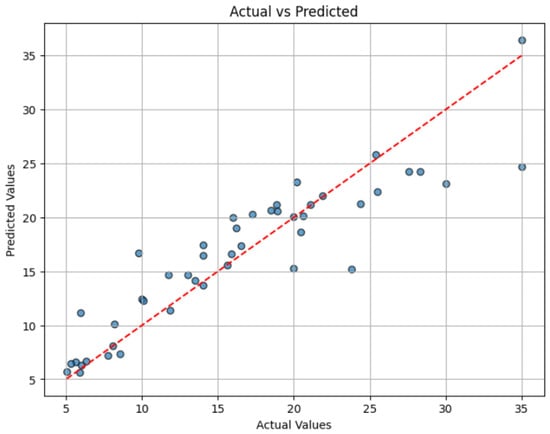

Figure 15 illustrates the correlation between the actual and predicted compressive strength values. Most data points are clustered near the 45-degree reference line, indicating a high level of agreement between experimental and model-predicted values. This alignment confirms that the GBR effectively learned the underlying relationships in the dataset, with minimal bias and error. Minor deviations can be attributed to experimental variability in factors such as mixing, curing conditions, and material heterogeneity. These results further reinforce the potential of machine learning as a reliable alternative to conventional regression methods for predicting the strength characteristics of pervious concrete.

Figure 15.

Actual vs. predicted compressive strength.

Despite these promising results, certain limitations were observed. Variability in experimental conditions and the relatively small dataset size might introduce minor discrepancies in model generalization. Future research could benefit from expanding the dataset and incorporating additional parameters, such as admixture content or temperature effects, to improve robustness [22].

The implications of this research are significant in the context of sustainable urban development. Pervious concrete has the potential to play a vital role in mitigating urban flooding, enhancing groundwater recharge, and promoting eco-friendly construction practices. By accurately predicting performance using data-driven approaches, engineers can tailor mix designs for specific environmental and structural needs, ultimately advancing the development of sustainable and resilient infrastructure systems.

7. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the compressive strength of pervious concrete can be effectively predicted using machine learning, particularly through Gradient Boosting Regression. By analyzing key mix parameters such as water–cement ratio, porosity, and aggregate distribution, the model achieved high predictive accuracy and showed good alignment with experimental results.

The findings reaffirm the trade-off between strength and permeability in pervious concrete, highlighting the importance of optimized mix design. Moreover, this research bridges experimental civil engineering with data-driven approaches, opening pathways for more efficient and sustainable concrete design practices.

The integration of predictive modeling in material science not only reduces the need for extensive physical trials but also enhances the ability to tailor concrete properties to site-specific requirements. This approach supports the broader goals of sustainable construction and climate-resilient infrastructure.

Future work can expand upon this foundation by incorporating more diverse materials, long-term durability analysis, and life cycle assessment, further enhancing the utility of machine learning in civil engineering applications.

8. Limitations, Future Work and Challenges

While this study successfully demonstrates the use of machine learning to predict compressive strength in pervious concrete, further research can enhance both the accuracy and applicability of the findings.

8.1. Dataset Limitations

This study has a few limitations. The dataset was compiled from multiple literature sources, which may introduce variability in testing conditions and material properties. The experimental validation involved a limited number of laboratory mixes, and the analysis focused only on 28-day compressive strength due to inconsistent reporting of other mechanical properties. Additionally, specialized or uncommon mix materials were excluded to maintain dataset consistency, making the model most applicable to conventional pervious concrete mixes.

8.2. Key Future Research Directions Might Include

- Expanding the dataset with more experimental variables such as binder types, chemical admixtures, and recycled materials.

- Exploring deep learning models (e.g., neural networks, CNNs) to capture more complex interactions among mix parameters.

- Studying the long-term durability of pervious concrete under chemical, mechanical, and environmental stresses (e.g., freeze-thaw cycles, acid exposure).

- Integrating Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) for a comprehensive evaluation of environmental impact.

- Developing a user-friendly software tool or web app that enables engineers to input mix parameters and obtain strength predictions.

- Validating ML models through field-scale trials and region-specific materials to improve practical scalability.

- Incorporating uncertainty quantification to improve the reliability of predictions in real-world scenarios.

- Enhancing model robustness through cross-dataset validation and more advanced validation techniques to address observed variability and improve generalization to diverse experimental conditions.

- Additionally, future work should explore more robust uncertainty propagation techniques, such as quantile regression or Bayesian approaches, to offer prediction intervals and better reflect model confidence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.A.B. and G.G.M.N.A.; methodology, H.A.B. and G.G.M.N.A.; software, H.A.B.; validation, H.A.B. and G.G.M.N.A.; formal analysis, H.A.B.; investigation, G.G.M.N.A.; resources, G.G.M.N.A.; data curation, H.A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, H.A.B. and G.G.M.N.A.; writing—review and editing, H.A.B. and G.G.M.N.A.; visualization, H.A.B.; supervision, G.G.M.N.A.; project administration, G.G.M.N.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to compilation from third-party published sources.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PC | Pervious Concrete |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| GBR | Gradient Boosting Regressor |

| CA | Coarse Aggregate |

| FA | Fine Aggregate |

| w/c | Water–Cement Ratio |

| IS | Indian Standard |

| MPa | Megapascal |

| SCM | Supplementary Cementitious Material |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| ASTM | American Society for Testing and Materials |

| ACI | American Concrete Institute |

| CSH | Calcium Silicate Hydrate |

Appendix A. Model Code Snippet

Below is a simplified Python snippet showing the structure of the Gradient Boosting Regressor used:

| from sklearn.ensemble import GradientBoostingRegressor |

| model = GradientBoostingRegressor(n_estimators=200, learning_rate=0.05, |

| max_depth=4) |

| model.fit(X_train, y_train) |

Appendix B. Collected Dataset Snapshot

The following table shows a portion of the experimental dataset collected from literature:

Table A1.

Sample entries from the compiled dataset.

Table A1.

Sample entries from the compiled dataset.

| Cement (kg) | w/c Ratio | Porosity (%) | Compressive Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 590 | 0.25 | 15 | 24.4 |

| 590 | 0.35 | 25 | 17.9 |

| 590 | 0.25 | 20 | 19.4 |

References

- Andrew, R. Global CO2 emissions from cement production, 1928–2018. Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 2019, 11, 1675–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibeigibeni, A.; Stochino, F.; Zucca, M.; Gayarre, F.L. Enhancing Concrete Sustainability: A Critical Review of the Performance of Recycled Concrete Aggregates (RCAs) in Structural Concrete. Buildings 2025, 15, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Sampath, P.V.; Biligiri, K.P. A review of sustainable pervious concrete systems: Emphasis on clogging, material characterization, and environmental aspects. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 261, 120491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Jiang, G. Experimental study on properties of pervious concrete pavement materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.; Akin, M.; Shi, X. Permeable concrete pavements: A review of environmental benefits and durability. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 210, 1605–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirthagadeshwaran, G.; Ramesh, S.; Selvi, K. An Experimental Study on Pervious Concrete. Int. Res. J. Multidiscip. Technovation 2019, 1, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.; dos Santos, V.; Pagnussat, D.T.; Brandalise, R.N. Effect of Void Content on Compressive Strength of Pervious Concrete. J. Sustain. Constr. Mater. Technol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahangdale, S.; Maran, S.; Lakhmani, S.; Gidde, M. A Study on Factors Affecting Strength and Permeability of Pervious Concrete. Int. J. Eng. Res. 2021. Available online: http://www.irjet.net/archives/V4/i6/IRJET-V4I6648.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Lyu, Q.; Dai, P.; Chen, A. Correlations among physical properties of pervious concrete with different aggregate sizes and mix proportions. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2024, 25, 2747–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Pieralisi, R.; B. Sandoval, F.G.; López-Carreño, R.; Pujadas, P. Optimizing pervious concrete with machine learning: Predicting permeability and compressive strength using artificial neural networks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 443, 137619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Chu, W.; Zhang, R.; Gao, Z.; Yang, Y. Predicting the permeability and compressive strength of pervious concrete using a stacking ensemble machine learning approach. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguesvari, M.; Narasimha, V. Studies on Characterization of Pervious Concrete for Pavement Applications. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 104, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirthagadeshwaran, G.; Ramesh, S.; Selvi, K. Utilization of Fly Ash in Pervious Concrete: Strength and Permeability Studies. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sonebi, M.; Bassuoni, M.; Yahia, A. Pervious Concrete: Mix Design, Properties and Applications. Rilem Tech. Lett. 2016, 1, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IS 10086:1982; Method of Test for Compressive Strength of Concrete. Bureau of Indian Standards: New Delhi, India, 1982. Available online: https://law.resource.org/pub/in/bis/S03/is.10086.1982.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- IRC 44:2017; Guidelines for Cement Concrete Mix Design for Pavement Quality Concrete. Indian Roads Congress: New Delhi, India, 2017. Available online: https://archive.org/details/gov.in.irc.044.2017 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Kováč, M.; Sičáková, A. Influence of Water-Cement Ratio on Workability and Strength in Pervious Concrete. Mater. Res. Proc. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, M.; Valunjkar, S. An Experimental Study on Compressive Strength, Void Ratio and Infiltration Rate of Pervious Concrete. Int. J. Eng. Res. V4 2015, 4, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abousnina, R.; Aljuaydi, F.; Benabed, B.; Almabrok, M.H.; Vimonsatit, V. A State-of-the-Art Review on the Influence of Porosity on the Compressive Strength of Porous Concrete for Infrastructure Applications. Buildings 2025, 15, 2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikoopayan Tak, M.S.; Feng, Y.; Mahgoub, M. Advanced Machine Learning Techniques for Predicting Concrete Compressive Strength. Infrastructures 2025, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathiparan, N.; Wijekoon, S.H.; Jeyananthan, P.; Subramaniam, D.N. Prediction of characteristics of pervious concrete by machine learning technique using mix parameters and non-destructive test measurements. Nondestruct. Test. Eval. 2025, 41, 314–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, B.V.R.; Rajeswari, G. Effect of Fine Aggregate Addition on Strength and Permeability of Pervious Concrete. J. Civ. Eng. Mater. 2023. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.