Abstract

This study examines the use of electronic waste (e-waste) as an alternative material in concrete for sustainability and natural resource conservation. Various e-wastes, such as Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC), Glass-Reinforced Plastic (GRP), Glass Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (GFRP), cross-linked polyethylene (XLPE), polyethylene (PE), electronic cable waste (ECW), Waste Electrical Cable Rubber (WECR), copper fiber (Cu Fib.), aluminum Fibers (Al fib.), steel fibers, basalt fibers, glass fibers, aramid−carbon fibers, Kevlar fibers, jute fibers, and optical fibers, were tested for influence on compressive, flexural, tensile strength, modulus of elasticity, and water absorption. Outcomes show that fine particle waste at low levels (0.2–1.5%) can improve mechanical performance, while higher levels of replacement or coarse particles generally reduce performance. Mechanical and physical properties are highly sensitive to material type, particle size, and dose. Life cycle assessment (LCA) and predictive modeling are recommended as validation for sustainability benefits.

1. Introduction

Electronic waste has become a major worldwide environmental concern, with its quantity increasing rapidly in recent years. These substances present a danger not only because of the harmful substances they hold but also due to incorrect disposal methods. A mere tiny fraction of e-waste is recycled properly, whereas the remainder is either mishandled or disposed of in landfills [1,2]. These activities lead to environmental contamination and the exhaustion of essential resources, which eventually results in financial setbacks. Effective handling of electronic waste is crucial for environmental protection, ensuring human health and facilitating the recovery of valuable resources [1,3].

E-waste is defined as electrical and electronic devices that are outdated or non-operational, including both large household appliances as well as common electronic devices. According to European Directives WEEE 2002/96/EC [4] and 2012/19/EU [5], these types of waste can be further classified into ten different categories, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

EEE categories and WEEE list of products.

Electronic waste consists of a wide range of materials, such as metals, plastics, glass, and several hazardous elements. E-waste includes precious metals like gold, silver, copper, and aluminum that can be extracted for reuse, alongside harmful substances such as lead and mercury. The potential release of hazardous metals and additives from e-waste can be assessed through leaching tests. However, such analyses are beyond the scope of the present study, which focuses on the macroscopic mechanical performance of concrete.

The non-metallic fraction (NMF), derived from WEEE, is composed mainly of glass fibers, thermosetting resins, and brominated flame retardants, and its valorization using conventional methods is challenging [6]. Currently, the recycling methods that have been developed for NMF involve physical recycling, like shredding, milling, magnetic separation, and sieving, as well as chemical or surface treatments aimed at enhancing the compatibility of the material with the polymer matrix [6,7]. It can be reused as a filler in polymeric materials, contributing to an improvement in mechanical, thermal, and dimensional stability properties [6,7]. The use of recycled NMF represents a sustainable strategy for the valorization of electronic waste and the reduction of its environmental impact [6,7].

At present, the main technique for retrieving valuable resources from electronic waste is incineration, a method that emits carcinogenic and neurotoxic chemicals into the environment. Irresponsible incineration of electronic waste has resulted in considerable environmental problems, severely impacting air, water, and soil quality.

The Global E-waste Monitor reports that in 2022, the worldwide amount of electronic waste reached 62 million metric tons, marking an 82% rise since 2010. Nonetheless, merely 22.3% of this waste was adequately gathered and processed for recycling. The amount of e-waste is increasing rapidly, averaging 2.3 million metric tons annually and expected to hit 82 million tons by 2030, which is a 33% rise from 2020 [2]. Consequently, the production of e-waste is increasing almost five times faster than the existing capability for appropriate recycling.

The management of e-waste has emerged as a pressing challenge because of the swift increase in quantity and its adverse effects on the environment and public health. Although recycling technologies are available, their adoption is constrained by expensive costs and inadequate infrastructure, especially in developing nations [8].

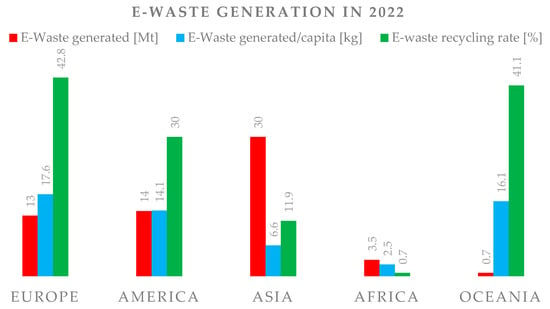

In 2022, the highest volume of electronic waste was produced in Asia (30 Mt), followed by the Americas (14 Mt) and Europe (13 Mt), whereas Africa and Oceania contributed much lower figures, amounting to 3.5 Mt and 0.7 Mt, respectively. Europe topped the list with 17.6 kg per person, followed by Oceania at 16.1 kg and the Americas at 14.1 kg. Asia and Africa showed reduced per capita amounts of 6.6 kg and 2.5 kg, respectively. In terms of recycling rates, Europe and Oceania significantly led with rates of 42.8% and 41.4%, respectively, while the Americas (30%), Asia (11.9%), and Africa (0.7%) had much lower figures as shown in Figure 1 [2].

Figure 1.

Graphical presentation of e-waste generated and recycled.

In Romania, a major issue is that there is no sufficient infrastructure for electronic waste collection [9]. Additionally, the lack of awareness among people regarding recycling and the negative impact of incorrect disposal is another significant obstacle.

Romanian legislation on waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) has always been brought in line with European legislation for the purpose of improving waste management. The adoption of Government Emergency Ordinance No. 5/2015 [10] was the key measure taken by Romania to transpose Directive 2012/19/EU [5], which is centered on extended producer responsibility not only at the point of sale but also after the product has reached the end-of-life. This directive clearly outlines the responsibility of WEEE collection, treatment, and recycling, which is now jointly held by producers, retailers, and local authorities. The aim is to build an effective and sustainable regime that minimizes environmental as well as health-related hazards and promotes the recovery and re-use of valuable materials.

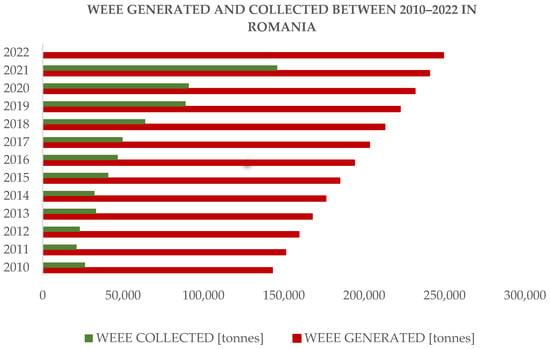

However, in 2019, Romania generated an estimated 223 thousand tons of e-waste, or 11.4 kg per capita, of which only 47 thousand tons were properly collected and recycled [11]. In 2022, the quantity had reached 250 thousand tons (approximately 13 kg per capita), and the recycled quantity had increased to 71.5 thousand tons [2]. Despite a rise in collection rates, the progress cannot keep up with the speed at which the waste is generated. These figures highlight the importance of better policies and infrastructure so that sustainable WEEE management can be ensured.

Data on WEEE in Romania in the period 2010–2022 were taken from the Eurostat database [12,13]. Both produced quantities and collection rates were analyzed, as shown in Table 2. It must be mentioned that while data for all the years exist in the case of e-waste generation, collection data exist up to 2021, according to the most recent updates from the above-described source.

Table 2.

Generated and collected e-waste in Romania between 2010 and 2022 [tons].

The evolution of WEEE can also be observed graphically in Figure 2, in which it can be seen that there is an obvious trend upward for both the quantity of waste produced and for the rate of collection in Romania for recent years.

Figure 2.

E-waste generated and collected in Romania (2010–2022). Source: own compilation from Eurostat.

Concrete is a significant constituent in construction, one of the most widely used building materials globally due to its strength, versatility, and relative affordability. The building sector is among the largest consumers of natural materials [14] and, simultaneously, among the greatest producers of waste. Cement is considered to be the primary ingredient in concrete, essential to this widely used material’s manufacturing process. The world produced 4.1 billion tons of cement in 2022 [15], reflecting the ongoing expansion of the construction sector.

Concrete mix can vary depending on application, but a typical mix consists of approximately 12% Portland cement, 34% fine aggregates, 48% coarse aggregates, and 6% water [16] by weight. Among all the constituents, aggregates make up the largest part by volume, which amounts to a very high use of natural raw materials. Aggregate use across the globe stands at approximately 50 billion tons annually, of which nearly 40% is used by the construction industry [17,18]. The extraction, handling, and processing of natural aggregates are energy-intensive processes and involve a significant environmental impact. They account for about 7% of the global energy consumption, and aggregate transportation alone accounts for 40% of the overall energy consumption in the construction sector [19]. Aggregates are typically extracted from quarries and other natural sources, and account for resource depletion and environmental degradation.

Aside from environmental effects of aggregate extraction and processing, cement production, with the highest carbon footprint of concrete, is an energy-intensive process. The production of one tons of cement requires approximately 1758 kWh [16], indicating that it plays a serious role in worldwide energy use and greenhouse gas emissions.

Because of the far-reaching global implications of this issue, the adoption of sustainable and durable solutions is imperative. In light of this, one of the solutions proposed by this research is to study and reveal the potential benefits of incorporating electronic waste into concrete, considering both sustainability criteria and performance characteristics of the resulting material. This practice would not just remove stress from natural resources by reducing demand for aggregate extraction, but also address the electronic waste management issue, thus transforming an environmental issue into an innovation driver for construction. It promotes a model in which resources are reused responsibly and effectively.

In addition, the study aims to identify and classify the types of electronic waste that are usable in concrete, synthesize the literature on the use of these materials in construction and evaluate the performance of concrete achieved by e-waste use. In so doing, the work contributes to the development of innovative measures for minimizing the environmental impact of electronic waste and increasing sustainable construction systems.

The paper represents an original contribution through a systematic analysis of the mechanical properties of concrete incorporating various types of electronic waste, correlating material behavior with the form and proportion of e-waste and examining multiple waste families and their influence on compressive strength, flexural strength, tensile strength, modulus of elasticity, and water absorption. Unlike previous reviews, this study integrates modulus of elasticity and water absorption to provide a comprehensive overview of the performance of modified concretes. Moreover, the paper presents a case study specific to Romania, based on current data on WEEE [2,11,12,13].

The findings from the reviewed studies have practical implications, informing both structural applications, such as load-bearing elements, and non-structural applications, including pavements and prefabricated components, supporting the development of sustainable construction practices. Consequently, the experimental investigations, which will use locally collected electrical and electronic wastes, will be conducted subsequently and reported in a future publication intended to validate and complement these findings.

2. Methodology

2.1. Literature Search

The literature search was conducted through searches in the Google Scholar, ResearchGate, and ScienceDirect databases, as well as by directly accessing articles published in MDPI journals relevant to the analyzed field.

Keyword combinations such as “concrete”, “electronic waste in concrete”, “production of sustainable materials”, “e-waste fibers”, “recycled fibers”, “fiber-reinforced concrete”, “influence of e-waste in concrete”, and “mechanical properties of concrete with e-waste” were used.

The temporal range covered by the search spanned from 1994 to 2025, with the majority of studies being recent, published in the last few years. Only peer-reviewed articles presenting experimental results on the mechanical and physical properties of concrete or mortar modified with electronic waste were selected.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Clear inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to guide the study selection with a view to ensuring relevance and consistency of the analysis.

Included studies were those that present experimental data for concrete or mortar incorporating electronic waste, fibers, or recycled aggregates. The selected studies analyze mechanical and physical properties, such as compressive strength, flexural strength, splitting tensile strength, modulus of elasticity, and water absorption. They also use reproducible methodologies with clearly defined dosages and material characterization. The studies are published in peer-reviewed journals or in conference proceedings relevant to the field.

Excluded studies were those that do not contain experimental data or present only theoretical models. Studies investigating non-cementitious matrices or lacking sufficient information regarding the material type or dosage were also excluded. Additionally, studies not meeting quality and relevance standards were eliminated.

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

For each selected study, information was extracted regarding the type and form of e-waste, replacement proportion, mix composition, and the resulting mechanical and physical properties. The data were synthesized to identify general trends, peak performance values, and specific limitations for each type of e-waste. Comparative tables and figures summarize these results, allowing clear correlations between material characteristics and concrete behavior.

3. Properties of E-Waste in Concrete

The reinforced concrete behavior changed by adding electronic waste in the form of fibers, powders, or aggregates shows a relationship between the material’s composition and its mechanical and physical properties, such as compressive strength (CS), flexural strength (FS), splitting tensile strength (STS), modulus of elasticity (MOE), and water absorption (WA). In Table 3, the mix design parameters of e-waste concrete reported in the literature are summarized, including the type and dosage of e-waste, type of application, cement type, water/cement ratio, and curing duration. In Table 4, the physical and mechanical properties studied in each work are summarized, indicating which type of test (CS, FS, STS, MOE, and WA) was performed in each study, highlighting gaps in the literature.

Table 3.

Mix design parameters of e-waste concrete in the literature.

Table 4.

Physical and mechanical properties reported in e-waste concrete studies.

According to observations made in the scientific literature, the response of concrete is directly influenced by the size, shape, and proportion of replacement of added wastes. Small additions of PVC, copper, steel, aluminum, Kevlar, basalt, or glass fibers can improve mechanical strength through dispersed reinforcement. Conversely, partial or total substitution of natural aggregates with rigid materials such as GRP, GFRP, XLPE, or ECW often results in substantial reduction of load-carrying capacity, accompanied by increased porosity. The elasticity modulus is also reflected by the embedded material’s inherent characteristics. Metal fibers contribute to greater stiffness, while flexible plastic components encourage a more deformable nature of the composite. Regarding water absorption, variations rely on fibers’ permeability and on the tightness of the blend. Dense, hydrophobic materials reduce absorption, whereas porous or flexible components increase it. Controlled use of e-waste in concrete, with optimized dosages and proper treatment, produces sustainable materials with balanced mechanical properties and improved durability.

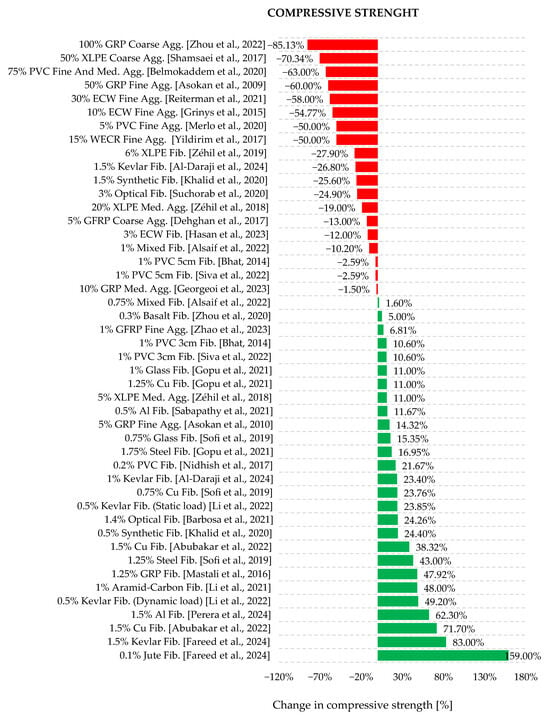

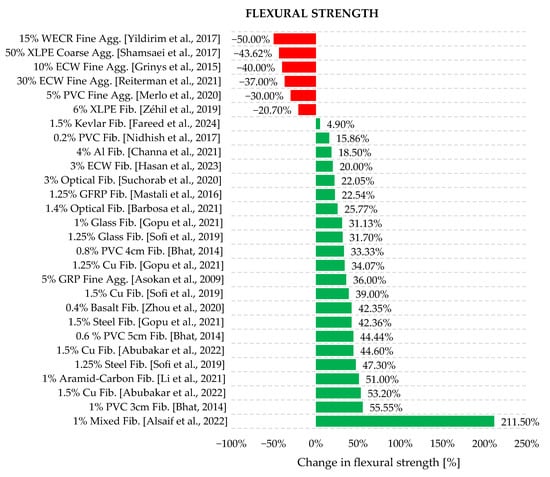

The next section presents a comparative overview of test results, linking performance to mixture characteristics. Common behavioral patterns, peak performance values, and usage limitations for each type of e-waste are highlighted, thereby contributing to the formulation of clear recommendations for their application in sustainable concrete. All percentage variations shown in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 represent the maximum increases or decreases observed at 28 days, except for study [21], where maximum/minimum values correspond to 91 days.

Figure 3.

Effect of recycled materials on compressive strength. Bars show the maximum increase or decrease in the property compared to the control sample. Values correspond to 28 days, except for studies [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,33,34,35,37,38,40,41,43,44,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56] (91 days).

Figure 4.

Effect of recycled materials on flexural strength. Bars show the maximum increase or decrease in the property compared to the control sample. Values correspond to 28 days, except for studies [20,21,22,25,30,31,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,44,45,46,47,50,51,54,56] (91 days).

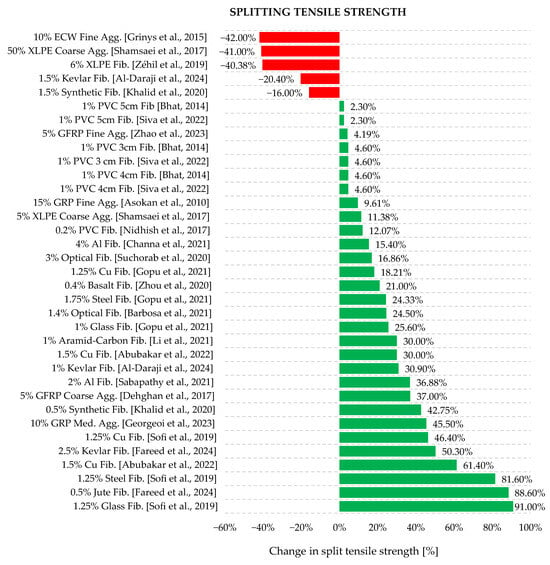

Figure 5.

Effect of recycled materials on split tensile strength. Bars show the maximum increase or decrease in the property compared to the control sample. Values correspond to 28 days, except for studies [20,21,22,24,26,27,28,30,33,34,35,37,38,40,41,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,53] (100 days).

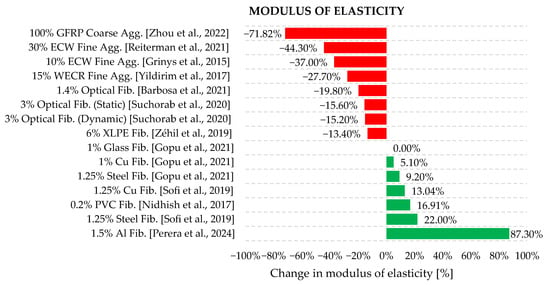

Figure 6.

Effect of recycled materials on the modulus of elasticity. Values correspond to 28 days, with references: [20,21,30,34,40,41,44,51,52,54,55].

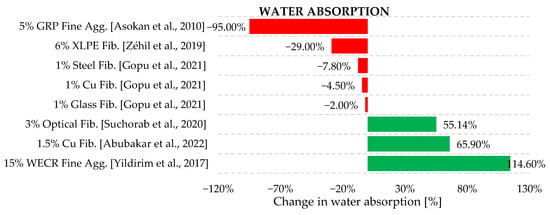

Figure 7.

Effect of recycled materials on the water absorption. Values correspond to 28 days, with references: [21,30,33,44,50,51].

3.1. Compressive Strength

The results of the reviewed studies on the influence of various types of electronic waste and recycled fibers on the compressive strength of concrete and mortar show increasing/decreasing trends, depending on the material type and dosage. These trends are illustrated in Figure 3.

The inclusion of e-plastic fibers, particularly those derived from PVC insulation of electrical cables, led to compressive strength increases of up to 10.6% at an optimal dosage of 1% and a fiber length of 3 cm [22,24]. Conversely, the use of longer fibers (5 cm) caused a 2.59% reduction in strength [22,24]. For recycled PVC fibers, optimal performance was observed at a content of 0.20%, resulting in a 21.67% increase in strength [41]. When PVC was used as aggregate, strength progressively decreased, reaching a 63% reduction at a 75% replacement level [43]. Other studies reported significant losses even at small replacement ratios, such as a 50% decrease at only 5% PVC content [39]. Additions of ground electronic cable waste (ECW), including mixtures of PVC, PE, and XLPE, reduced compressive strength. A 10% ECW addition reduced strength by up to 54.77% [20], while using ECW as aggregate in a 30% proportion led to a 58% reduction [54]. In mortars containing 0.5–1.5% ECW, strength values were close to those of the control sample, but at 3%, a 12% decrease was recorded [36]. For WECR, increasing the content up to 15% resulted in an approximately 50% reduction in compressive strength [44]. Cross-linked polyethylene (XLPE) waste showed dosage-dependent behavior. Replacing 5% of natural aggregates produced an 11% increase in strength [29]. Gradually increasing the replacement ratio to 20% caused reductions of up to 19% [29], and at 50%, a 70.34% reduction was observed [35]. Other research confirmed this downward trend, reporting a 27.9% reduction at a 6% XLPE content [30]. In the case of GRP and GFRP waste, results varied depending on dosage. When GRP was used as a replacement for fine aggregates, increases of up to 14.32% were recorded at a 5% dosage [33], while a 1.25% fiber content resulted in a significant 47.92% improvement [56]. At higher dosages of 50–100%, performance declined, with reductions of about 60% for a 50% GRP content [25] and up to 85.13% when coarse aggregate was completely replaced [52]. For GFRP added as fragments, compressive strength increased by 6.81% at a 1% content but decreased with higher dosages [26]. Replacing 10% of the aggregate with GRP caused a 1.5% drop [27], while a 5% replacement of coarse aggregate led to a reduction of approximately 13%, likely due to the water retention of fibers [53]. The addition of steel fibers resulted in a 16.95% increase in compressive strength at a 1.75% content [21], while another study reported up to a 43% increase at a 1.25% content [34]. Copper fibers consistently improved concrete performance, producing strength gains of 23.76% at a 0.75% dosage [34], 11% at 1.25% [21], and up to 38.32% at 1.5% [47]. Concrete with 1.5% copper fibers showed a 71.7% increase, with strength values rising from 20.14 N/mm2 at 7 days to 34.58 N/mm2 at 28 days [50]. Aluminum fibers also had a positive effect, yielding 62.3% increases in mortar at a 1.5% dosage [55] and 11.67% in concrete at 0.5% [28]. Kevlar fibers contributed significantly under both static and dynamic loading conditions. At a 0.5% dosage, compressive strength increased by 23.85%, while under dynamic loading it reached 164 MPa, representing an improvement of over 49.20% [23]. Other studies confirmed the efficiency of Kevlar and jute fibers, reporting strength increases of up to 83% for a 1.5% Kevlar content and up to 159% for 0.1% jute fibers [38]. Another investigation indicated decreases of up to 26.8% for 1.5% Kevlar fibers, while a 1% dosage yielded a 23.4% increase [49]. Basalt fibers performed optimally at a 0.3% content, with a 5% increase [37]. Glass fibers produced moderate gains, around 11% at a 1% dosage [21] and 15.35% at a 0.75% dosage [34]. Hybrid systems, such as aramid–carbon mixtures, led to increases of up to 48% at a 1% dosage [46]. In hybrid mixtures containing tire steel fibers and plastic fibers, compressive strength variations remained limited. The highest reduction of 10.20% was observed at a 1% total content (0.5% tire steel fiber + 0.5% plastic), and the highest increase of 1.60% at a 0.75% total content (0.25% tire steel fiber + 0.50% plastic fiber) [31]. Optical fibers produced results that depended on conditions. At lower w/c ratios and with crushed marble as aggregate replacement, a 24.26% increase was recorded after 7 days at a 1.4% fiber content [40]. Without marble aggregate, a 3% dosage caused a 24.90% reduction [51]. Synthetic fibers derived from plastic-fiber blends led to 24.4% increases at a 0.5% dosage, but at a 1.5% dosage, a 25.6% decrease was observed [48].

Overall, the mechanical behavior of concretes incorporating electronic waste varies according to the material’s nature, replacement proportion, and the form in which the waste is introduced (fiber, powder, and aggregate). Low dosages (0.2–1.5%) and finely processed waste can enhance compressive strength, while high replacement levels or coarse waste aggregates lead to significant strength losses.

3.2. Flexural Strength

The results of the reviewed studies on the influence of various types of recycled electronic waste on the flexural strength of concrete and mortar show increasing/decreasing trends, depending on the material type and dosage. These trends are shown in Figure 4.

E-plastic fibers (PVC), introduced in lengths of 3–5 cm, significantly improved flexural performance. At a dosage of 1% and a fiber length of 3 cm, a maximum value of 7.0 MPa was recorded, representing a 55.55% increase compared to the control (4.5 MPa). Fibers with a length of 5 cm produced a 44.44% increase at a 0.6% dosage. Fibers with 4 cm in length generated a 33.33% gain at a 0.8% dosage [22]. Recycled PVC fibers achieved optimal performance at a 0.20% content, with a 15.86% increase [41]. Higher PVC replacement ratios caused strength reductions of up to 30%, even at a substitution level as low as 5% [39]. Optical fibers showed a positive effect. In mixes containing recycled marble, a 1.4% dosage produced a 25.77% increase [40]. In another study without marble aggregate, a 3% dosage produced a 22.05% increase [51]. GRP and GFRP waste led to flexural strength gains. A 1.25% GFRP produced a 22.54% increase [56], and 5% GRP increased strength by 36% [25]. The behavior of composite materials depends on dosage and reinforcement configuration. Beams reinforced with GFRP can achieve performances comparable or slightly superior to those reinforced with steel [32,42].

XLPE fibers reduced flexural strength as their content increased. A 6% XLPE reduced strength by 20.7% [30], while at 50% the loss reached 43.62% [35]. Electric cable waste (ECW) and crushed mixtures (PVC, PE, and XLPE) also decreased strength. A 10% ECW dosage reduced strength by about 40% [20], and 30% crushed waste used as aggregate replacement decreased strength by 37% [54]. Small additions of ECW in fiber form, up to 1%, slightly reduced strength, while a 3% content led to an improvement of about 20% [36]. WECR fibers consistently decreased flexural strength, with losses of up to 50% at a 15% dosage [44]. Aluminum fibers increased strength by 18.5% at a 4% dosage, after which performance declined [45].

Steel fibers produced significant improvements in flexural strength, with increases of 42.36% at a 1.5% dosage [21] and 47.30% at a 1.25% dosage in other studies [34]. Copper fibers enhanced concrete performance, yielding a 34.07% increase at 1.25% dosage [21]. Other studies reported gains of 39% [34] and 53.20% [47] for a 1.5% content. In another study, concrete with 1.5% copper fibers showed a 44.6% increase, with strength values rising from 5.58 N/mm2 at 7 days to 8.07 N/mm2 at 28 days [50]. Glass fibers increased flexural strength by 31.13% at a 1% dosage [21]. Electrical waste glass fibers achieved a 31.7% increase at a 1.25% dosage [34]. Kevlar fibers showed modest performance, with a 4.9% increase at a 1.5% dosage and a 25 mm length [38]. Basalt fibers produced substantial gains, with a 42.35% increase at a 0.4% dosage [37].

Hybrid aramid–carbon mixtures improved flexural strength by up to 51% at a 1% dosage [46]. Combined fiber mixes showed wide variations. The highest increase was 211.5% at a 1% total fiber content (0.5% tire steel fiber + 0.5% plastic) [31].

Overall, all fiber types increased the maximum flexural strength compared to control concrete. Strength improves significantly at optimal dosages, while massive replacements or rigid materials (XLPE and ECW) cause considerable performance losses.

3.3. Splitting Tensile Strength

The results of the reviewed studies on the influence of various types of recycled electronic waste on the splitting tensile strength of concrete show increasing/decreasing trends depending on material type and dosage. These trends are illustrated in Figure 5.

E-plastic (PVC) fibers of 3–5 cm moderately increased tensile strength. At a dosage of 1% and a fiber length of 3 cm, strength increased by 4.6%. Fibers of 4 cm and 5 cm produced increases of 4.6% and 2.3%, respectively [22,24]. Recycled PVC fibers achived optimal performance at a 0.20% content, with a 12.07% increase [41]. Optical fibers increased strength by 24.50% at 1.4% dosage in mixtures containing crushed marble [40], and by 16.86% at 3% dosage without marble [51]. XLPE fibers showed dosage-dependent behavior. Replacing 5% of coarse aggregate with XLPE increased strength by 11.38%, while 50% replacement caused a 41% reduction [35]. Another study reported a 40.38% reduction at a 6% XLPE content [30]. Electric cable waste (ECW) reduced tensile strength, with 10% fine aggregate replacement causing a 42% decrease [20]. Steel fibers increased tensile strength by 24.33% at a 1.75% dosage [21] and up to 81.6% at a 1.25% dosage in another study [34]. Copper fibers produced gains of 18.21% [21] and 46.4% [34] at a 1.25% dosage and 61.4% at a 1.5% content [47]. Excessive copper content reduced strength. Another study showed a 30% increase, from 3.36 N/mm2 at 7 days with 0.5% copper fiber to 4.37 N/mm2 at 28 days with 1.5% copper fiber [50]. Glass fibers increased strength by 25.6% at a 1% dosage [21] and by 91% at a 1.25% dosage [34]. Replacing aggregates with GFRP or GRP increased tensile strength by 37% at 5% replacement [53], 45.5% at 10% [27], 9.61% at 15% [33] and 4.19% at 5% [26]. Basalt fibers increased strength by 21% at a 0.4% dosage [37]. Kevlar fibers showed mixed results. A 1% dosage increased strength by 30.9%, whereas a 1.5% dosage reduced it by 20.4% [49]. Another study reported a 50.3% increase at 2.5% Kevlar fibers of 25 mm length [38]. Jute fibers increased strength by 88.6% at a 0.5% dosage and a 15 mm fiber length [38]. Aluminum fibers improved strength by 36.88% at a 2% dosage [28] and 15.40% at a 4% dosage [45]. Synthetic fibers from cable waste increased strength by 42.75% at a 0.5% dosage, but a 1.5% dosage caused a 16% reduction [48]. Aramid–carbon hybrid mixtures increased strength by 30% at a 1% dosage [46].

Overall, all types of fibers and finely processed electronic waste can improve tensile strength at optimal dosages. Massive replacements or rigid materials (XLPE and ECW) reduce performance. The highest gains were observed with well-distributed metallic and natural fibers, while PVC and XLPE fibers produced moderate but controlled improvements.

3.4. Modulus of Elasticity

The reviewed studies show that different types of recycled electronic waste affect the modulus of elasticity (MOE) of concrete, depending on the waste type and dosage. These trends are illustrated in Figure 6.

Recycled PVC fibers exhibited increases in the modulus of elasticity of 16.91% at a dosage of 0.20% [41]. Optical fibers exhibited reduced stiffness. The static modulus decreased from 12.93 GPa (control) to 10.91 GPa for a 3% fiber content, a 15.6% reduction. The dynamic modulus decreased from 15.47 GPa to 13.12 GPa, a 15.2% reduction [51]. In mixtures with a reduced water-to-cement ratio, the modulus increased by 2%, while 1.4% optical fibers caused a 19.8% decrease [40].

GFRP fibers used as aggregate reduced the modulus of elasticity. At 100% GFRP replacement, the modulus decreased from 26.54 GPa to 7.45 GPa, a 71.82% reduction [52]. WECR fibers caused a 27.7% decrease at a 15% dosage [44]. Crushed cable waste (PVC, PE, and XLPE) used as aggregate reduced stiffness from 34.3 GPa to 19.1 GPa at 30% replacement, a 44.3% reduction [54]. XLPE fibers reduced the modulus of elasticity. At a 6% content, it dropped from 38.1 GPa to 33 GPa, a 13.4% reduction [30]. Other studies confirmed these reductions, attributing them to the intrinsic flexibility of XLPE and its limited contribution to elastic behavior [29]. Electric cable waste (ECW) as fine aggregate replacement decreased the modulus by 37% at a 10% dosage [20]. Aluminum fibers increased the modulus of elasticity by 87.3% at a 1.5% dosage [55]. Copper fibers increased MOE by 5.1% at a 1% dosage [21] and 13.04% at a 1.25% dosage [34]; higher contents caused decreases. Steel fibers increased the modulus of elasticity by 9.2% at a 1.25% dosage [21] and up to 22% in other studies [34]. The addition of 1% glass fibers did not significantly affect the modulus of elasticity [21].

Overall, the modulus of elasticity varies with waste type and dosage. Metallic and PVC fibers produced limited increases. Rigid fibers or waste aggregates (GFRP, XLPE, and ECW) caused substantial reductions.

3.5. Water Absorption

The water absorption of concrete containing with electronic and plastic waste varied depending on material type and dosage. These trends are illustrated in Figure 6.

Concrete with 6% XLPE fibers showed a 29% decrease in water absorption compared to the control due to the lower permeability of XLPE fibers [30]. WECR increased absorption from 3.28% to 7.04% at a 15% dosage, a 114.6% rise, indicating higher porosity with more waste [44]. Optical fibers, increased absorption from 3.21% to 4.98% at a 3% dosage, a 55.14% increase [51]. Steel, glass, and copper fibers reduced absorption by 7.8%, 2%, and 4.5% at a 1% content, respectively [21]. Copper fibers caused a progressive increase from 0.85% at 7 days for a 0.5% content to 1.41% at 28 days for a 1.5% content, a 65.9% rise [50]. Replacing fine aggregate with 5% GRP, decreased absorption from 6.15% to 0.30%, a 95% reduction [33].

Water absorption is sensitive to the type and dosage of waste fibers or aggregates. Low permeability materials (XLPE, aluminum, and GRP) reduced absorption, while optical fibers and cable rubber waste increased it.

3.6. Discussions

Data analysis shows that the type and dosage of materials added to concrete significantly influence the mechanical properties. Steel, copper, aluminum, Kevlar, jute, and basalt fibers are beneficial at low dosages and consistently improve compressive, flexural, and tensile strength. For example, metallic fibers can increase compressive strength by up to 43% [21,34] and tensile strength up to 82% [21,34], while fibers such as jute or basalt enhance compressive and tensile strength up to 159% [38] and up to 21% [37], respectively. In the case of Kevlar, variations are larger [23,38,49], reflecting this material’s sensitivity to interaction with the concrete matrix.

In contrast, plastic fibers and electronic waste, such as PVC, XLPE, ECW, and WECR, cause a significant decrease in mechanical performance at high dosages. It is reported that PVC and XLPE may reduce compressive strength by up to 70% and tensile strength by more than 40% [22,24,29,30,35,39,41,43]. Moreover, WECR increases water absorption by up to 115% [44], reflecting increased porosity. The results also suggest how important dosage control and type selection can be in order to avoid substantial decreases in concrete properties.

Optical fibers exhibit mixed behavior. While they increase flexural and tensile strength by 22–26% and 16.86–24.50%, respectively, they reduce the stiffness by 16–20% and increase water absorption by 55% [39,51], indicating a matrix-flexibilizing effect without fully compromising strength.

Rigid aggregates, including GRP and GFRP, provide limited improvements at low dosages. Large substitutions can reduce compressive strength by up to 85% and the modulus of elasticity by up to 72% [25,26,27,33,52,53,56], confirming the negative effects of excessive incorporation of rigid materials.

Overall, the performance of concrete depends on the type and form of added materials, as well as their dosage. While fibers at low concentration contribute to strength enhancement, large substitutions, plastics, or rigid materials result in significant losses in mechanical properties. Specific values are provided in Table 5, summarizing the effects of different types of fiber and e-waste on properties of concrete.

Table 5.

Influence of e-waste as fibers and aggregate replacements on the mechanical properties of concrete.

4. Perspectives and Directions for Future Research

Using electronic waste in concrete mix is an emerging field of study that is at the intersection of sustainability, circular economy, and technology.

The selected mechanical and durability properties include compressive strength, flexural strength, splitting tensile strength, modulus of elasticity, and water absorption. In fact, they represent the essential parameters required for structural assessment and design. They control load-bearing capacity, stiffness, cracking behavior, deformation limits, and long-term durability. All these together, they form the practical toolset used in structural design checks at ultimate and serviceability limit states. Centering the analysis on these parameters positions the material within real structural requirements. It ensures that any modified concrete mix is evaluated in terms of actual design performance.

The existing literature in the scientific database shows that such materials can significantly enhance certain properties of concrete if used in appropriate dosage and form. However, variations between waste types, their degree of processing, and their interaction with cement paste make the topic ripe for specific experimental investigation. Current studies also lack standardized guidance on testing procedures, making it difficult to compare or reproduce results reliably.

Future research should adopt stepwise protocols with controlled dosages, particle sizes, and combinations of materials, such as optical fibers with GRP or flexible polymers with Kevlar, to identify synergies between stiffness and flexibility. This approach will enable the determination of material combinations that maximize mechanical performance while maintaining workability and durability.

Current findings confirm that the effect of incorporating electronic waste is a matter of dosage, particle size, and distribution. Small dosages (0.2–1.5%) enhance mechanical properties, while higher additions produce substantial reductions in strength and stiffness. Follow-up work will need to use a stepwise experimental strategy enabling the realization of an optimal balance between performance and sustainability.

To facilitate industrial-scale deployment, follow-up research must include sustainability analyses projecting resulting energy savings and CO2 reductions via electronic waste substitution of natural aggregates. Recent data indicate that replacing 50% of natural aggregates with recycled alternatives results in minor Global Warming Protection (GWP) increases (0.7–3.4%), while full replacement can increase GWP up to 7.3% [57] due to higher water demand and additional cement or superplasticizer. At the same time, replacing one ton of natural aggregate with alternative recycled aggregate reduces carbon emissions by approximately 58% [58]. Overall, concrete with ≥50% recycled aggregates generally exhibits lower environmental impact than conventional concrete, especially when transport and material reuse are considered. Coupling experimental results with life cycle assessment (LCA) will allow identification of mixes that balance mechanical performance with environmental benefits, supporting circular economy objectives and providing a solid framework for optimizing future experimental designs.

Experimental data on concrete incorporating electronic waste first provide insights into material behavior at the laboratory scale. These data can be integrated into structural analysis software (e.g., Abaqus, Axis, SAP2000) to simulate load-bearing capacity, deformation, cracking patterns, and stiffness variations, allowing identification of applications where the material is suitable. Based on these simulations, preliminary digital databases can be developed to guide engineers on potential structural and non-structural uses. Table 5 illustrates an initial set of parameters and possible applications; it serves as a starting reference and will be refined through additional numerical simulations. However, current studies are mainly limited to laboratory-scale specimens, and the table does not yet represent a fully accessible database. Pilot and full-scale studies are necessary to evaluate industrial feasibility and practical limitations, enabling the reliable use of the laboratory results at the structural scale.

A high-potential area describes the use of double-functional optical fibers as both reinforcing materials and structural health monitoring integrated sensors. Concrete may then be changed into an “intelligent” material that can provide real-time information on deformation, cracking, or temperature change, thus enhancing structural safety and durability.

For purposes of future experiments, a variety of electronic and plastic waste materials that are products of cable manufacturing operations has been supplied by Prysmian Group [59]. These are a good possibility for comparative analysis among different recycled products and include optical cables, optical fibers, GRP, Kevlar, polyethylene, polypropylene, steel wires, and metal strips. Each material has something unique to offer: GRP and Kevlar can be employed as lightweight, high-strength reinforcement, and optical fibers and plastics can contribute to weight reduction and increased impermeability, while metallic components can contribute to stiffness and toughness. The next phases of research must include detailed characterization of the materials from both physical–mechanical and chemical perspectives, in order to assess their compatibility with the cement matrix and ensure safety in term of potential leaching.

A real step already undertaken towards field implementation is the laboratory casting of a set of test beams reinforced longitudinally with GRP and optical cables, both incorporating standard steel stirrups. These specimens will be subjected to mechanical tests to determine flexural behavior, shear strength, and deformability. The results of these tests will be helpful in determining a design model for safe application of such materials in real structural elements such as beams, precast slabs, or light panels.

5. Conclusions

Electronic waste should be included in concrete as a controlled, low-dosage strategy rather than a wholesale substitute for natural aggregates. The applicability of such an approach is dependent on critical selections of types and forms of material that have influences on mechanical behavior and stiffness of the concrete matrix. Improper or excessive use has compromised structural performance, and this demands measured application.

Planned experimental programs, such as the casting of test beams reinforced with GRP and optical cables together with traditional steel stirrups, represent some of the practical paths toward verification of these solutions. These planned tests are expected to contribute to the establishment of a reliable framework that ensures safety for the use of non-conventional materials for structural elements, such as beams, precast slabs, and light panels. They will also allow controlled assessment of load-carrying capacity and deformability of the specimens.

Current data also emphasize that variability between studies remains considerable. Investigations on material characteristics, methodologies of preparation, and testing protocols show the underlying importance of reproducibility and standardization. In fact, it is only under conditions of consistency in experimental practice that such methods can be validated for inclusion into technical standards and practical guidelines for structural design.

The overall evidence shows that e-waste has potential as a supplementary material in concrete and provides specific performance benefits under proper application. The necessary foundation is established through a stepwise approach adopted for these studies, ensuring the safe and effective application of such innovations translated from laboratory research into practical structural solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.G., C.M.N., and I.P.; methodology, C.G. and C.M.N.; validation, C.M.N., I.P., and P.I.S.; formal analysis, C.G.; investigation, C.G.; resources, C.G. and C.M.N.; data curation, C.G.; writing—original draft preparation, C.G.; writing—review and editing, C.G., C.M.N., I.P., and P.I.S.; visualization, C.G.; supervision, C.M.N., I.P., and P.I.S.; project administration, C.G. and C.M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are included in the article and derived from the referenced sources.

Acknowledgments

The study was conducted within the doctoral program of the Technical University of Cluj-Napoca (TUCN).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kumar, G.; Bansal, T.; Haq, M.; Sharma, U.; Kumar, A.; Jha, P.; Sharma, D.; Kamyab, H.; Valencia, E.A.V. Utilizing E-Waste as a Sustainable Aggregate in Concrete Production: A Review. Buildings 2024, 14, 2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldé, C.P.; Kuehr, R.; Yamamoto, T.; McDonald, R.; D’Angelo, E.; Althaf, S.; Bel, G.; Deubzer, O.; Fernandez-Cubillo, E.; Forti, V.; et al. International Telecommunication Union (ITU) and United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR). Global E-waste Monitor 2024. Geneva/Bonn. 2024. Available online: https://ewastemonitor.info/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/GEM_2024_EN_11_NOV-web.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Lee, J.; Choi, H.; Kim, J. Environmental and economic impacts of e-waste recycling: A systematic review. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 494, 0152917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and Council. Directive 2002/96/EC on Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE). Official Journal of the European Union, L 37/24, 13 February 2003. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32002L0096 (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- European Parliament and Council. Directive (EU) 2021/19 on Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE). Official Journal of the European Union, L 38/15, 19 January 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/RO/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32012L0019 (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Kovačević, T.; Rusmirović, J.; Tomić, N.; Mladenović, G.; Milošević, M.; Mitrović, N.; Marinković, A. Effects of oxidized/treated non-metallic fillers obtained from waste printed circuit boards on mechanical properties and shrinkage of unsaturated polyester-based composites. Polym. Compos. 2018, 40, 1170–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačević, T.; Rusmirović, J.; Tomić, N.; Marinović-Cincović, M.; Kamberović, Ž.; Tomić, M.; Marinković, A. New composites based on waste PET and non-metallic fraction from waste printed circuit boards: Mechanical and thermal properties. Compos. Part B Eng. 2017, 127, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinto, S.; Law, N.; Fletcher, C.; Le, J.; Antony Jose, S.; Menezes, P.L. Exploring the E-Waste Crisis: Strategies for Sustainable Recycling and Circular Economy Integration. Recycling 2025, 10, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Păceșilă, M.; Ciocoiu, C.N.; Colesca, S.E.; Burcea, Ș.G. Current trends in weee management in romania. Theor. Empir. Res. Urban Manag. 2016, 11, 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Romania. Government Emergency Ordinance No. 5/2015 on Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment. Official Gazette of Romania 2015, Part I, No. 253, 16 April 2015. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/167211 (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Forti, V.; Baldé, C.P.; Kuehr, R.; Bel, G. The Global E-waste Monitor 2020: Quantities, Flows and the Circular Economy Potential. United Nations University (UNU)/United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR)—Co-Hosted SCYCLE Programme, International Telecommunication Union (ITU) & International Solid Waste Association (ISWA): Bonn/Geneva/Rotterdam. Available online: https://ewastemonitor.info/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/GEM_2020_def_july1_low.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Eurostat, Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment by Waste Management Operations. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/env_waseleeos__custom_16844384/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- WEEE Calculation Tools Developed Under the Study Contract No. 070307/2013/667383/ETU/ENV.A2. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/pdf/waste/weee/WEEE%20calculation%20tools/E-waste_generated_Tool_BEL.xlsm (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Krause, K.; Hafner, A. Resource Efficiency in the Construction Sector: Material Intensities of Residential Buildings—A German Case Study. Energies 2022, 15, 5825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ige, O.E.; Von Kallon, D.V.; Desai, D. Carbon emissions mitigation methods for cement industry using a systems dynamics model. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2024, 26, 579–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babor, D.; Plian, D.; Judele, L. Environmental Impact of Concrete. Bul. Institutului Politeh. Din lasi. Sect. Constr. Arhit. 2009, 55, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, L.; Royal, A.C.D.; Jefferson, I.; Hills, C.D. The Use of Recycled and Secondary Aggregates to Achieve a Circular Economy within Geotechnical Engineering. Geotechnics 2021, 1, 416–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijerathne, D.; Wahala, S.; Illankoon, C. Impact of Crushed Natural Aggregate on Environmental Footprint of the Construction Industry: Enhancing Sustainability in Aggregate Production. Buildings 2024, 14, 2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, U.; Poon, C.S.; Lo, I.M.; Cheng, J.C. Comparative environmental evaluation of aggregate production from recycled waste materials and virgin sources by LCA. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 109, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinys, A.; Vaičiukyniene, D.; Augonis, A.; Sivilevičius, H.; Bistrickait, R. Effect of milled electrical cable waste on mechanical properties of concrete. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2015, 21, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopu, G.N.; Sofi, A. Electrical Waste Fibers Impact on Mechanical and Durability Properties of Concrete. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2021, 9, 1854–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, I.G. A New Paradigm on Experimental Investigation of Concrete for E-Plastic Waste Management. Int. J. Eng. Trends Technol. 2014, 10, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.-F.; Huang, Y.-R.; Syu, J.-Y.; Tsai, Y.-K.; Huang, C.-H. A study on mechanical behavior of Kevlar fiber reinforced concrete under static and high-strain rate loading. Int. J. Prot. Struct. 2022, 14, 407–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siva, A.K.; Vetrivel, K.; Gull, I.G.; Murugesan, B. An experimental investigation on use of post consumed E-plastic waste in concrete. Int. J. Eng. Res.-Online 2022. Available online: http://www.ijoer.in (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Asokan, P.; Osmani, M.; Price, A. Assessing the recycling potential of glass fibre reinforced plastic waste in concrete and cement composites. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Lv, Y.; Chen, J.; Song, P.; Sun, M.; Zhang, X.; Huang, L. Effect of Glass Fiber-Reinforced Plastic Waste on the Mechanical Properties of Concrete and Evaluation of Its Feasibility for Reuse in Concrete Applications. Materials 2023, 16, 6772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgeoi, C.; Negrutiu, C.; Sosa, I. Concrete with E-Waste as a substitute for aggregate. In Proceedings of the International Conference “Tradition and Innovation 70 Years of Higher Education in Civil Engineering in Transilvania”, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 8–11 November 2023; pp. 53–54. [Google Scholar]

- Sabapathy, Y.; Sabarish, S.; Nithish, C.; Ramasamy, S.; Krishna, G. Experimental study on strength properties of aluminium fibre reinforced concrete. J. King Saud Univ.-Eng. Sci. 2021, 33, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zéhil, G.-P.; Saba, D. Exploring XLPE-concrete as a novel sustainable construction material. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings, Milan, Italy, 22–24 June 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zéhil, G.-P.; Assaad, J.J. Feasibility of concrete mixtures containing cross-linked polyethylene waste materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 226, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaif, A.; Alshannag, M. Flexural Behavior of Portland Cement Mortars Reinforced with Hybrid Blends of Recycled Waste Fibers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmokrane, B.; Chaallal, O.; Masmoudi, R. Glass fibre reinforced plastic (GFRP) rebars for concrete structures. Constr. Build. Mater. 1995, 9, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asokan, P.; Osmani, M.; Price, A. Improvement of the mechanical properties of glass fibre reinforced plastic waste powder filled concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 448–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofi, A.; Gopu, G.N. Influence of steel fibre, electrical waste copper wire fibre and electrical waste glass fibre on mechanical properties of concrete. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 513, 012023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsaei, M.; Aghayan, I.; Kazemi, K.A. Experimental investigation of using cross-linked polyethylene waste as aggregate in roller compacted concrete pavement. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 165, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, Z.A.; Jasim, M.H.; Shaker, A.A.; Nasr, M.S.; Abdulridha, S.Q.; Hashim, T.M. Experimental Investigation on Using Electrical Cable Waste as Fine Aggregate and Reinforcing Fiber in Sustainable Mortar. Ann. Chim. Sci. Des Matériaux 2023, 47, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Jia, B.; Huang, H.; Mou, Y. Experimental Study on Basic Mechanical Properties of Basalt Fiber Reinforced Concrete. Materials 2020, 13, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fareed, S.; Zahid, B.; Khan, A.-U. Mechanical properties of kevlar and jute fiber reinforced concrete. J. Sustain. Constr. Mater. Technol. 2024, 9, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, A.; Lavagna, L.; Suarez-Riera, D.; Pavese, M. Mechanical properties of mortar containing waste plastic (PVC) as aggregate partial replacement. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2020, 13, e00467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M.T.; dos Santos, W.J.; Ludwig, Z.; de Souza, N.L.D.; Stephani, R.; de Oliveira, L.F.C. Optical Fiber Waste Used as Reinforcement for Concrete with Recycled Marble Aggregate. J. Manag. Sustain. 2021, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidhish; Arunima, S. Parametric Study on Fibrous Concrete Mixture Made from E-Waste PVC Fibres. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Res. Dev. 2017, 4, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayed, S.; Al-Salloum, Y.; Almusallam, T. Performance of glass fiber reinforced plastic bars as a reinforcing material for concrete structures. Compos. Part B Eng. 2000, 31, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmokaddem, M.; Mahi, A.; Senhadji, Y.; Pekmezci, B.Y. Physical and Mechanical Properties of Concrete Containing PVC Waste as Aggregate. In International Symposium on Materials and Sustainable Development; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, S.; Duygun, N.U.R. Mechanical and Physical Performance of Concrete Including Waste Electrical Cable Rubber. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 245, 022054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channa, I.A.; Saand, A. Mechanical Behavior of Concrete Reinforced with Waste Aluminium Strips. Civ. Eng. J. 2021, 7, 1169–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-F.; Wang, H.-F.; Syu, J.-Y.; Ramanathan, G.K.; Tsai, Y.-K.; Lok, M.H. Mechanical Properties of Aramid/Carbon Hybrid Fiber-Reinforced Concrete. Materials 2021, 14, 5881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abubakar, A.; Mohammed, A.; Duna, S.; Yusuf, U.S. Relationship between Compressive, Flexural and Split Tensile Strengths of Waste Copper Wire Fiber Reinforced Concrete. Path Sci. 2022, 8, 4001–4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, F.S.; Saaidin, S.H.; Shahidan, S.; Othman, N.H.; Guntor, A.A.N. Strength of Concrete Containing Synthetic Wire Waste as Fiber Materials. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 713, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Daraji, M.; Aljalawi, N. The Effect of Kevlar Fibers on the Mechanical Properties of Lightweight Perlite Concrete. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2024, 14, 12906–12910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.; Mohammed, A.; Duna, S.; Umar, S.E.Y. Prediction of mechanical properties of waste copper wire fiber reinforced concrete using response surface methodology. World J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2022, 8, 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Suchorab, Z.; Franus, M.; Barnat-Hunek, D. Properties of Fibrous Concrete Made with Plastic Optical Fibers from E-Waste. Materials 2020, 13, 2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Weng, Y.; Li, L.; Hu, B.; Huang, X.; Zhu, Z. Recycled GFRP Aggregate Concrete Considering Aggregate Grading: Compressive Behavior and Stress–Strain Modeling. Polymers 2022, 14, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan, A.; Peterson, K.; Shvarzman, A. Recycled glass fiber reinforced polymer additions to Portland cement concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 146, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiterman, P.; Lidmila, M. The Use of Crushed Cable Waste as a Substitute of Natural Aggregate in Cement Screed. Buildings 2021, 11, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, K.D.Y.G.; Ahamed, Y.L.F.; Somarathna, H.M.C.C.; Jayasekara, D.A.B.P.M.; Mohotti, D.; Raman, S.N. Uniaxial compressive response of cement mortar with waste aluminium fibre sourced from electrical distribution cables. Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Des. 2024, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastali, M.; Dalvand, A.; Sattarifard, A. The impact resistance and mechanical properties of reinforced self-compacting concrete with recycled glass fibre reinforced polymers. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 124, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabău, M.; Bompa, D.V.; Silva, L.F. Comparative carbon emission assessments of recycled and natural aggregate concrete: Environmental influence of cement content. Geosci. Front. 2021, 12, 101235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wałach, D. Analysis of Factors Affecting the Environmental Impact of Concrete Structures. Sustainability 2021, 13, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prysmian Romania. Set of Recycled Electronic and Plastic Materials and Corresponding Technical Data Sheets Provided for Research Purposes; Internal Technical Documentation; Prysmian Romania: Slatina, Romania, 2025. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.