Abstract

Scapholunate (SL) ligament injuries, if not properly treated, can compromise wrist biomechanics, leading to instability, scapholunate advanced collapse (SLAC) and progressive osteoarthritis. Depending on the severity of the injury, current repair techniques include either arthroscopic or open surgical approaches; however, the limited vascularization of the region often represents an obstacle to optimal ligament healing. This study aims to assess the feasibility of using a vascularized fascial flap based on the 1,2 intercompartmental supraretinacular artery (1,2 ICSRA) for biological augmentation of the scapholunate ligament. Five previously injected cadaveric upper limbs were dissected and flap dimensions, including length, width, and pedicle length, were measured using a millimeter-calibrated ruler by two independent operators. All flaps provided sufficient coverage, and the vascular pedicle length allowed tension-free positioning without vascular kinking. These findings demonstrate that a 1,2 ICSRA-based fascial flap is anatomically feasible for scapholunate ligament augmentation. It should be noted that this is a purely cadaveric study, and the technique has not yet been tested in vivo. The results suggest potential surgical applications, providing a vascularized biological option that may enhance ligament healing in future clinical studies.

1. Introduction

The scapholunate (SL) joint plays a crucial role in maintaining wrist stability and function. The scapholunate interosseous ligament (SLIL) is the primary intrinsic stabilizer of this joint, serving a key role in load transmission and carpal kinematics [1]. Injury to the SLIL leads to significant alterations in wrist biomechanics [2,3].

The most common traumatic mechanism involves a fall on an outstretched hand with the wrist in ulnar deviation, producing shear and torsional forces across the scapholunate interval [4]. Clinically, patients typically present with poorly localized periscaphoid pain, often accompanied by palpable clunks or “clicks” over the dorsal SL interval. Complete disruption of the SLIL, together with failure of the secondary stabilizers, results in scapholunate dissociation (SLD), characterized by a permanent malalignment of the carpal bones and structural wrist instability. Over time, this pathological condition inevitably progresses to scapholunate advanced collapse (SLAC) deformity and post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Surgical repair may be ineffective, particularly in complete tears, due to the poor local vascularization that can impair or delay ligament healing. Vascularization arises primarily from terminal branches of the radial artery and from vessels passing through the radioscapholunate ligament [5]. Although several repair techniques described in the literature primarily focus on restoring the structural continuity of the scapholunate ligament, no studies have combined mechanical reconstruction with a biological support such as a vascularized graft. Therefore, the aim of this anatomical study was to describe and evaluate a novel technique using a vascularized fascial flap based on the 1,2 intercompartmental supraretinacular artery (1,2 ICSRA) to provide local biological augmentation for scapholunate ligament repair.

2. Materials and Methods

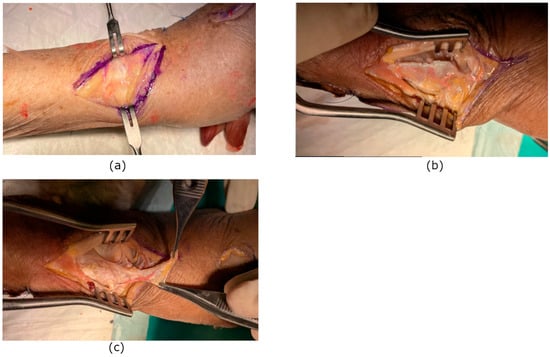

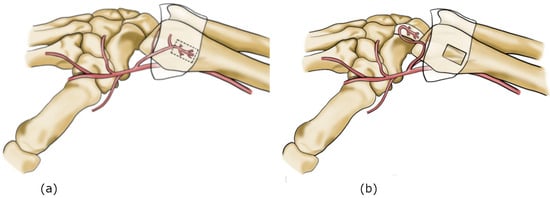

The anatomical dissections were performed during the 14th Course of Anatomical Dissection and Surgical Anatomy of the Upper Limb, held in Cremona (Italy) from 13–16 January 2025. The study was conducted on five fresh-frozen cadaveric upper limbs previously arterially injected with colored latex to enhance vascular visualization. The sample size was determined by the organizational setting of the anatomical dissection course, in which one upper limb was assigned to each pair of participants (for a total of seven upper limbs). Of these, only five specimens were suitable for inclusion, as the remaining limbs were anatomically compromised by previous surgical approaches and therefore excluded from analysis. None of the specimens showed evidence of previous trauma, deformity, or prior surgical procedures involving the wrist. A dorsoradial incision was made, centered over the radiocarpal joint between the first and second extensor compartments. The superficial sensory branches of the radial nerve were identified and carefully protected throughout the dissection. After opening the first and second extensor compartments, the 1,2 intercompartmental supraretinacular artery (1,2 ICSRA) was identified along its course between the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis tendons (first compartment) and the extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis tendons (second compartment). A vascularized fascial flap based on the 1,2 ICSRA was then carefully elevated from the bony plane, maintaining the integrity of the vascular pedicle (Figure 1). After performing a capsulotomy to adequately expose the scapholunate interval and completing a standard scapholunate repair, the vascularized fascial flap was mobilized on its 1,2 intercompartmental supraretinacular artery pedicle and gently rotated toward the dorsal scapholunate interval. The flap was then positioned as an onlay augmentation over the SL ligament, with the synovialized surface oriented toward the joint to minimize friction and promote biological integration. Fixation of the flap in vivo would be performed as an adjunct to the primary ligament repair and would be intended to maintain intimate contact between the fascial graft and the scapholunate ligament remnants. This could be achieved using absorbable sutures placed between the margins of the flap and the residual ligament tissue when adequate remnants are present. In cases in which sufficient ligamentous tissue is not available for secure suturing, suture anchors placed in the dorsal aspect of the scaphoid and lunate could be considered to achieve stable fixation, although this was not evaluated in the present cadaveric study. Care would be taken to avoid tension on the vascular pedicle and to preserve flap perfusion throughout positioning and fixation.

Figure 1.

(a) Dorsoradial skin incision centered over the radiocarpal joint between the first and second extensor compartments. (b) Flap incision. (c) Vascular pedicle isolation and transposition.

The dimensions of the flap, including its length and width, as well as pedicle length, were measured using a millimeter-calibrated ruler by two independent operators. Flap length and width referred exclusively to the fascial graft component, excluding the vascular pedicle. Pedicle length was defined as the distance from the proximal origin of the 1,2 intercompartmental supraretinacular artery to the distal end of the vascular pedicle at the base of the flap. The feasibility of transposing the flap into the scapholunate interval was evaluated, assessing its reach, orientation, and the possibility of fixation to the scaphoid and lunate without vascular kinking, compromise or excessive tension. For this study, feasibility was defined using quantitative anatomical criteria. A minimum pedicle length of 14 mm was required to allow safe reach of the implantation site, and feasibility further depended on the ability to achieve at least 110° of pedicle rotation without excessive tension in order to properly orient the graft toward the recipient site. All dissections were performed under 3.5× loupe magnification and documented with high-resolution photographs. No metallic anchors were used, as none were available during the dissection. This study has some methodological limitations. The small number of specimens limits the generalizability of the findings, and no biomechanical testing was performed to compare the strength of the reconstructed ligament with that of the native or non-augmented repair. Therefore, the present results should be interpreted as preliminary anatomical observations that may serve as a basis for future biomechanical and clinical investigations. The aim of this anatomical study was to assess the feasibility of harvesting and transposing a vascularized fascial flap based on the 1,2 ICSRA for potential biological augmentation of scapholunate ligament reconstruction (Figure 2). It was conducted in accordance with Italian regulations on body donation for scientific research; ethics committee approval was not required.

Figure 2.

(a) 1,2 ICSRA vascular anatomy. (b) 1,2 ICSRA harvest and insetting on SL interval.

3. Results

The 1,2 intercompartmental supraretinacular artery (1,2 ICSRA) was consistently identified in all five specimens. The artery originated from the radial artery between the first and second extensor compartments and followed a predictable course over the distal radius. The vascularized fascial flap based on the 1,2 ICSRA was successfully elevated in all cases while maintaining the vascular pedicle intact. The mean pedicle length was 20 mm (range: 14–26 mm), the mean graft width was 8.5 mm (range: 5–12 mm), and the mean graft length was 23 mm (range: 17–29 mm) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Anatomical measurements of the vascularized fascial flap. The table summarizes the mean, minimum, and maximum values for pedicle length, flap width, and flap length obtained from five cadaveric upper limbs.

Interobserver reliability was assessed for pedicle length, graft width, and graft length measurements using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC, two-way random effects model, absolute agreement). For all three parameters, measurements obtained by the two independent observers were identical across all specimens, resulting in an ICC of 1.00 for pedicle length, graft width, and graft length. These findings indicate perfect agreement between observers for all anatomical measurements evaluated in this study. While perfect ICC values may appear unusual, they accurately reflect the absence of measurement discrepancies in this dataset and should be interpreted in the context of the limited sample size. Future studies with larger cohorts and repeated measurements may provide a more granular estimate of measurement variability. The harvested flap demonstrated sufficient mobility to be transposed into the scapholunate interval without vascular compromise or excessive tension. The orientation and reach of the flap allowed adequate coverage of the ligament area, suggesting its potential applicability as a biological augmentation in scapholunate ligament repair. No major anatomical variations or complications were encountered during the dissections.

4. Discussion

The scapholunate ligament is one of the most important stabilizing structures of the carpus and plays a key role in maintaining wrist stability. When injured and not properly treated, it disrupts normal wrist biomechanics and may progressively lead to Scapholunate Advanced Collapse (SLAC), resulting in radiocarpal osteoarthritis, pain, and functional limitation. Several repair techniques have been described in the literature, depending on the type and severity of the lesion, including arthroscopic repair, percutaneous pinning, direct ligament suture, or reconstruction with tendon or composite grafts.

However, repair of the scapholunate ligament remains challenging due to several factors:

- The ligament is composed not only of a fibrous component but also of a cartilaginous one, characterized by limited vascularization [6].

- It anchors onto the scaphoid and lunate bones, both known for their relatively tenuous and variable vascular supply, especially at their proximal poles, which are more vulnerable to ischemia [7,8].

- The vascularization of the scapholunate ligament relies primarily on small terminal branches of the radial artery that pass through the radioscapholunate ligament [5].

Local augmentation techniques previously described in the literature include the use of the dorsal intercarpal ligament, three-ligament tenodesis, composite grafts (such as the bone–retinaculum–bone technique), and many others [9,10,11]. In the former, local augmentation is obtained from the dorsal intercarpal ligament, which is partially incised to create a ligamentous flap that is then used to stabilize the scaphoid and lunate, typically fixed to the lunate through transosseous sutures. An alternative technique is the three-ligament tenodesis (3LT), which uses a distally based strip of the flexor carpi radialis tendon passed through a scaphoid tunnel, fixed to the lunate via a dorsal trough and anchor suture, tensioned through the dorsal radiotriquetral ligament, and temporarily stabilized with K-wires across the scapholunate and scaphocapitate joints. The bone–retinaculum–bone technique, on the other hand, involves excision of a longitudinal portion of Lister’s tubercle in order to harvest a segment of bone covered by retinaculum; after removal of the central bony portion with a rongeur, a composite graft is obtained that can be interposed between the scaphoid and lunate. To date, no technique involving a vascularized flap for scapholunate ligament augmentation has been described, and existing approaches primarily focus on restoring anatomical continuity and structural stability, with limited consideration of biological or vascular support. The purpose of the present study is to explore the anatomical feasibility of a vascularized fascial flap as a potential augmentation option, rather than to demonstrate clinical effectiveness. The proposed technique is based on the hypothesis that combining mechanical support with vascularized tissue may, in theory, create a more favorable biological environment for healing. During the 14th Course of Anatomical Dissection and Surgical Anatomy of the Upper Limb, held in Cremona (Italy) from 13–16 January 2025, five latex-injected cadaveric forearms were dissected to assess the feasibility of transferring a vascularized fascial flap based on the 1,2 intercompartmental supraretinacular artery (1,2 ICSRA) into the scapholunate space. From an anatomical standpoint, this cadaveric investigation demonstrated that the flap can be reliably harvested and transposed without compromising its vascular pedicle. The course of the 1,2 ICSRA was consistent, and the flap dimensions were suitable for coverage of the scapholunate interval. These findings confirm anatomical feasibility and define the vascular anatomy and potential arc of rotation of the flap, but do not provide evidence of functional or clinical benefit. To translate these anatomical findings into potential clinical applications, the next steps could include biomechanical testing in cadaveric wrist models to quantify the contribution of the flap to scapholunate stability, followed by pilot studies in appropriate animal models to assess in vivo vascular reliability, tissue integration, and healing potential. If successful, small-scale pilot clinical cohorts could then be considered to evaluate safety, technical feasibility, and preliminary functional outcomes. From a clinical perspective, although not yet tested in vivo, this anatomical study suggests that the proposed flap could offer dual benefits: mechanical reinforcement through the fascial graft and biological enhancement via its intrinsic vascular supply. This combination might improve ligament healing and potentially reduce postoperative recovery time. Vascularized grafts, although technically more demanding and requiring greater surgical expertise, may promote faster and more reliable integration compared with conventional avascular techniques [12,13]. Moreover, the use of a fascial flap offers an additional advantage: it is harvested from the extensor retinaculum, which physiologically accommodates the extensor tendons and has a multilayered structure. The retinaculum is composed of three distinct layers: an outer layer of loose connective tissue, a middle layer of collagen and elastic fibers with fibroblasts, and an inner gliding layer. The innermost layer, in direct contact with the tendons, withstands considerable tensile and shear stresses. Accordingly, it exhibits histological features of chondroid metaplasia and contains hyaluronic acid-secreting cells [14]. These properties suggest a possible “like-with-like” reconstruction, although their clinical relevance remains to be demonstrated. Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. The investigation was conducted exclusively on cadaveric specimens, and the technique has not yet been tested in living subjects. As such, the findings should be interpreted as preliminary anatomical observations that require further validation. In addition, the relatively small number of specimens limits the generalizability of the results. While cadaveric models are appropriate for anatomical feasibility studies, they cannot fully reproduce in vivo conditions, particularly with regard to vascular dynamics, tissue elasticity, and biological healing responses. Biomechanical testing was not performed, and fixation testing could not be carried out because suture anchors were not available. Consequently, the mechanical contribution of the flap and the strength of ligament integration under physiological loads could not be quantitatively assessed and remain to be clarified in future studies. Finally, the absence of a comparative anatomical control group precludes direct comparison with alternative reconstructive techniques.

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

This cadaveric study demonstrates the anatomical feasibility of a vascularized fascial flap based on the 1,2 inter-compartmental supraretinacular artery (1,2 ICSRA) as a potential option for augmentation in scapholunate ligament repair. While the technique appears technically achievable in an anatomical setting, its clinical effectiveness and functional impact cannot be inferred from the present data and remain to be established through further investigation. This approach offers a dual advantage:

- Biological benefit: The vascular supply of the flap provides a potential advantage over techniques lacking vascular support, promoting biological healing of the ligament and potentially accelerating postoperative recovery. The use of vascularized fascia may enhance the reparative process, which is typically slow in scapholunate ligament healing.

- Histological compatibility: The use of a fascial flap allows for a “like-with-like” reconstruction by employing the synovialized portion of the extensor retinaculum, which exhibits chondroid metaplasia and is therefore more suitable than other augmentation techniques relying solely on fibrous ligamentous tissue, such as the dorsal intercarpal ligament. The clinical relevance of this histological compatibility, however, has not been demonstrated and should be interpreted as a theoretical consideration rather than a proven benefit.

The harvested flap showed adequate dimensions and mobility to cover the scapholunate ligament area without tension or vascular compromise. However, as this study was conducted exclusively on cadaveric specimens, further biomechanical and clinical investigations are needed to confirm the in vivo feasibility, safety, and potential benefits of this technique in reducing recovery time and enhancing ligament regeneration. Future studies should focus on translating these anatomical findings into clinical practice. Biomechanical testing is needed to evaluate the stability provided by the vascularized fascial flap compared with conventional repairs. In vivo investigations will be essential to assess flap viability, integration with native ligament tissue, and potential complications. Long-term clinical trials should evaluate functional outcomes, ligament healing, and prevention of degenerative changes. Comparative studies with existing augmentation techniques will help define the specific advantages and limitations of this vascularized approach.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P. and D.R.; methodology A.P. and D.R.; validation E.P.; formal analysis A.P.; investigation E.P. and S.O.; resources Y.P.; data curation Y.P. and D.R.; writing—original draft preparation E.P.; writing—review and editing S.O. and Y.P.; visualization Y.P.; supervision A.P. and S.G.; project administration A.P. and S.G.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. The study was conducted in accordance with Italian regulations on body donation for scientific research; ethics committee approval was not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SLAC | Scapho-Lunate Advanced Collapse |

| ICSRA | Inter-Compartmental Supra-Retinacular Artery |

| SL | Scapholunate |

| SLIL | Scapholunate Interosseus Ligament |

| SLD | Scapholunate Dissociation |

References

- Linscheid, R.L.; Dobyns, J.H.; Beabout, J.W.; Bryan, R.S. Traumatic instability of the wrist. Diagnosis, classification, and pathomechanics. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1972, 54, 1612–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, F.W.; Sutton, L.G.; Allison, M.A.; Gilula, L.A.; Short, W.H.; Wollstein, R. Scaphoid and Lunate Translation in the Intact Wrist and Following Ligament Resection: A Cadaver Study. J. Hand Surg. 2011, 36, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Short, W.H.; Werner, F.W.; Green, J.K.; Masaoka, S. Biomechanical evaluation of the ligamentous stabilizers of the scaphoid and lunate: Part II. J. Hand Surg. 2005, 30, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, C.E.; Wolfe, S.W. Scapholunate Instability: Current Concepts in Diagnosis and Management. J. Hand Surg. 2008, 33, 998–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, J.K. Treatment of scapholunate ligament injury: Current concepts. EFORT Open Rev. 2017, 2, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chato-Astrain, J.; Roda, O.; Carriel, V.; Hita-Contreras, F.; Sánchez-Montesinos, I.; Alaminos, M.; Hernández-Cortés, P. Histological characterization of the human scapholunate ligament. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2024, 87, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelberman, R.H.; Bauman, T.D.; Menon, J.; Akeson, W.H. The vascularity of the lunate bone and Kienböck’s disease. J. Hand Surg. 1980, 5, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelberman, R.H.; Menon, J. The vascularity of the scaphoid bone. J. Hand Surg. 1980, 5, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, K.; Terrono, A.L. Dorsal intercarpal augmentation ligamentoplasty for scapholunate dissociation. Tech. Hand Up. Extrem. Surg. 2003, 7, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Elias, M.; Lluch, A.L.; Stanley, J.K. Three-Ligament Tenodesis for the Treatment of Scapholunate Dissociation: Indications and Surgical Technique. J. Hand Surg. 2006, 31, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, J.M.; Weiss, A.P. Bone-retinaculum-bone reconstruction of scapholunate ligament injuries. Orthop. Clin. N. Am. 2001, 32, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandinelli, D.; Pagnotta, A.; Piperno, A.; Marsiolo, M.; Aulisa, A.G.; Falciglia, F. Surgical Treatment of Scaphoid Non-Union in Adolescents: A Modified Vascularized Bone Graft Technique. Children 2025, 12, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagnotta, A.; Taglieri, E.; Molayem, I.; Sadun, R. Posterior Interosseous Artery Distal Radius Graft for Ulnar Nonunion Treatment. J. Hand Surg. 2012, 37, 2605–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, D.M.; Katzman, B.M.; Mesa, J.A.; Lipton, J.F.; Caligiuri, D.A. Histology of the extensor retinaculum of the wrist and the ankle. J. Hand Surg. Am. 1999, 24, 799–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.