Abstract

At the cortical level, the central auditory neural system (CANS) includes primary and secondary areas. So far, much research has focused on recording fronto-central auditory evoked potentials/responses (P1-N1-P2), originating mainly from the primary auditory areas, to explore the neural processing in the auditory cortex. However, less is known about the secondary auditory areas. This review aimed to investigate and compare fronto-central and T-complex responses in populations at risk of auditory dysfunction, such as individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders. After searching the electronic databases (PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Ovid), ten studies encompassing six neurodevelopmental disorders were included for the analysis. All experimental populations had atypical T-complexes, manifesting as an absence of evoked responses, shorter latency, and/or smaller amplitude. Moreover, in two experimental groups, dyslexia and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), abnormal T-complex responses were observed despite the presence of normal fronto-central responses. The presence of abnormal T-complex responses in combination with normal fronto-central responses in the same population, using the same experiment, may highlight the advantage of the T-complex for indexing deficits in distinct auditory processes or regions, which the fronto-central response may not track.

1. Introduction

Listening difficulties are commonly reported in children with neurodevelopmental disorders. In many cases, these challenges are not fully explained by disordered transduction in the cochlea or abnormal early processing along the auditory brainstem pathway. It is therefore likely that these listening challenges are associated with how auditory information is processed in the cortex. Auditory information enters the cortex through primary auditory areas and then projects to secondary and tertiary auditory areas [1,2]. The primary auditory cortex (PAC) is the first cortical region involved in acoustical processing and receives inputs from the thalamus and the medial geniculate body (MGB) [3,4]. The PAC can be segmented into three regions; from anterior to posterior, these regions consist of the planum polare (PP), Heschl’s gyrus (HG), and the planum temporale (PT) (Figure 1). HG is located on the supratemporal plane, extending diagonally from the superior temporal gyrus (STG) [5,6]. The STG encompasses the secondary auditory areas and anatomically interfaces with the lower-level auditory areas and higher-level structures contributing to language, music, and other forms of auditory processing [7]. The STG plays a special role in the neural analysis of speech sounds and phonological processing [8,9].

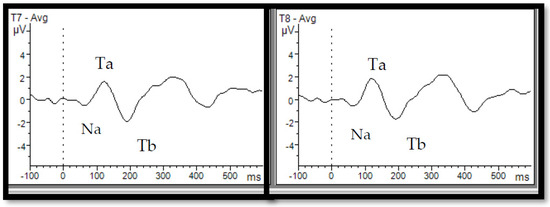

Figure 1.

Auditory evoked potentials from the temporal lobe and T-complex. T-complex waveforms—consisting of successive Na, Ta, and Tb peaks—were recorded at the left (T7) and right (T8) temporal sites in adults in response to a 1 kHz tone. This figure was derived from data collected at our Electrophysiology Lab, University of Ottawa, and has not been published before.

Impairments in the central auditory system may lead to poor listening abilities, mostly labeled as auditory processing disorder (APD) [10]. This disorder affects around 5–7% of children [11,12,13,14]. APD and other neurodevelopmental disorders such as language impairment (LI), attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and autism share a common characteristic: developmental delays, which can impair personal, social, academic, or occupational functioning [15]. Moreover, various developmental disorders may overlap with each other [16]. Multiple studies have shown that LI, ADHD, and autism are often comorbid with APD [16,17,18,19]. Hence, evaluating auditory processing, along with language, attention, and other cognitive abilities, in these populations is highly recommended [20]. Over the years, auditory evoked potentials (AEPs) have been utilized to explore impairments in the auditory cortex in these populations [21,22,23,24,25].

AEPs are series of changes in electrical brain activity triggered by acoustic stimulation. At the cortical level, there are two categories of AEPs: fronto-central and temporal responses [26,27]. Fronto-central responses include P1-N1-P2-N2 and are measured over fronto-central sites but arise mainly from primary auditory areas and index the acoustical processing of sound [27,28]. Numerous studies recording P1-N1-P2-N2 have indicated deficits in cortical auditory processing among individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders [22,29,30,31,32]. For instance, in a group of children with language impairments, smaller amplitudes and/or longer latencies of P1, N1, and P2 were observed compared to those of responses obtained from typically developing (TD) groups [29,33].

The T-complex, or temporal auditory response, is another AEP that corresponds to fronto-central responses in terms of timing but is recorded over temporal sites and consists of the Na-Ta-Tb sequence (Figure 1) [26,34,35]. Both fronto-central and temporal responses are sensitive to physical modulations of stimuli such as changes in intensity, interstimulus interval (ISI), and stimulus onset asynchrony (SOA) in children and adults [36,37,38,39]. For instance, consistent with fronto-central responses, the T-complex’s amplitude increases with a longer SOA [40]. Despite sharing similar time windows, there are some differences between T-complex and fronto-central responses. In fact, P1-N1-P2 has a frontal topography, represents activity mainly in the primary auditory areas [41,42,43], and features a tangential dipole orientation [26,41,42]. In contrast, the T-complex has a temporal topography and reflects the activity of lateral temporal structures within the posterior lateral superior temporal gyrus, with a radial dipole orientation [26,35,41]. Maturational studies also suggest that the T-complex matures earlier than the fronto-central response (about 4–5 years old vs. 8–9 years old) and remains stable with increasing age [35,44,45]. Considering the developmental trajectory, it is thought that the T-complex relates to the more complex processing of sound and better correlates with speech and language processing as compared to fronto-central responses [40,44,46].

Multiple studies have demonstrated the effectiveness and reliability of the T-complex in assessing auditory processing at the cortical level [21,45,47]. The evaluation of fronto-central and T-complex waveforms in individuals with auditory dysfunction is promising, as it can yield information regarding the origin of the deficit, specifically, whether it arises from within the superior temporal plane or the posterior lateral superior temporal gyrus [47].

To the best of our knowledge, no review has investigated and compared the properties of the T-complex and fronto-central responses of different populations with auditory dysfunctions. Therefore, this review aims to compile studies measuring T-complex and fronto-central responses in populations with neurodevelopmental disorders. Specifically, the first objective is to report and document the properties of T-complex responses in populations with neurodevelopmental disorders. The second objective is to explore the similarities and differences between the T-complex and fronto-central responses.

2. Methods

A scoping review was carried out in order to incorporate multiple types of studies with disparate methodologies [48]. Two reviewers (ZA and AK) were involved in the review process [49]. The second reviewer (AK) analyzed only articles included by the first reviewer, using a liberal accelerated approach. If a disagreement arose, a third reviewer was tasked with its resolution (FDL) [49].

In order to avoid missing any related articles, key words were selected in a manner designed to provide as many as studies as possible on the T-complex, with no preference for age or population characteristics. Then, the studies matched with the target population (neurodevelopmental disorder) were identified during the screening steps based on the inclusion criteria. The search terms relating to the T-complex included auditory or speech-evoked potential or response, electroencephalography (EEG) assessment, electrophysiological indices, neural encoding, cortical processing, neural activity, event-related potential (ERP) response, neural response, mismatch negativity, speech signal, oscillatory EEG response, CAEP, auditory neural integrity, event-related potential, auditory measure, electrophysiological measure, and electroencephalography.

Databases, including PubMed, the Web of Science, Scopus, and Ovid, were searched separately, and results were compiled in the Covidence database, where search strategies were dated and organized. Conference papers, master’s dissertations, and doctoral theses (gray literature) were searched through ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global, Google Scholar, and Theses Canada.

This review included literature published until 2023. The method for screening and finding the related studies followed the PRISMA process [50]. In the initial screening, reviewer 1 (ZA) retained or rejected articles based only on title analysis. Both reviewers (ZA and AK) completed the second and third screenings; in these steps, the eligibility was based on abstract and full-text analyses, respectively. The exclusion and inclusion criteria are described in Appendix A. According to the goals of this review, only studies with participants with neurodevelopmental disorders were included. Also, because using a translator was not feasible for this study, only articles in English were selected.

3. Results

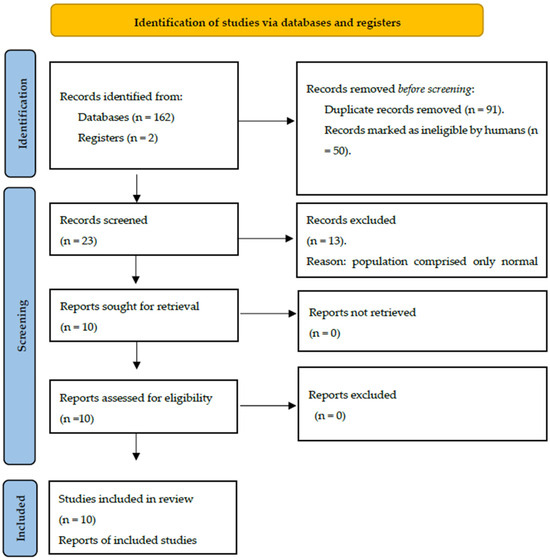

From the databases, a total of 164 articles were identified. Following the initial screening step and removal of duplicates (n = 91), 73 articles remained. Among the 73 articles, 23 articles were included based on title evaluation (Bishop et al., 2012; Bruneau et al., 2003; Bruneau et al., 1999; Bruneau et al., 2015; Cacace et al., 1988; Carrillo-de-la-Peña, 1999; Čeponien et al., 1998; Clunies-Ross et al., 2015; Clunies-Ross et al., 2018; Gomes et al., 2012; Groen et al., 2008; J. A. Hämäläinen et al., 2011; Ponton et al., 2002; Shafer et al., 2011; Silva et al., 2020; Rinker et al., 2021; Taylor et al., 2003; Tonnquist-Uhlén, 1996; Tonnquist-Uhlen et al., 2003; Wolpaw & Penry, 1975, 1977; Wagner et al., 2016; Woldorff & Hillyard, 1991) [18,21,23,26,29,35,36,37,39,40,45,46,47,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60]. As a result of abstract screening, 13 studies were excluded, as they did not include abnormal populations among their participants (Bruneau et al., 2015; Cacace et al., 1988; Carrillo-de-la-Peña, 1999; Čeponien et al., 1998; Clunies-Ross et al., 2015; Clunies-Ross et al., 2018; Ponton et al., 2002; Silva et al., 2020; Tonnquist-Uhlen et al., 2003; Wolpaw & Penry, 1975, 1977; Wagner et al., 2016; Woldorff & Hillyard, 1991) [26,35,36,37,40,45,46,47,51,52,56,59,60]. The remaining ten articles underwent a thorough full-text screening, and all of them met the eligibility criteria and were consequently included in this study. The PRISMA flow diagram is presented in Figure 2. The data, encompassing information about experimental and control groups, event-related potentials (ERPs) of interest, and the results, have been succinctly summarized in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Flow chart for the scoping review process [50].

Table 1.

(A) Summary of included studies. (B) Summary of results.

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.1.1. Type of Disorder

Four studies were found to assess LI using the T-complex [23,29,55,57]. A further study assessed ADHD [53]; two assessed dyslexia [39,58]; one assessed Down syndrome (DS) [54]; and two assessed autism [18,21]. These neurodevelopmental disorders often have comorbidity with APD, potentially sharing symptoms related to auditory dysfunction [16,61]. Notably, there was no study investigating the T-complex in children diagnosed with auditory processing disorder.

3.1.2. Age

Only one study examined the T-complex in adults, while the remaining studies focused on child participants. One study included both children (aged 7–12 years) and teenagers (aged 13–16 years) [29]. The age range varied from the youngest participant at 4 years old to the oldest teenager at 16 years old [29]. However, among the included studies, one study was conducted on adults aged between 18 and 45 years old (average age was 25 years old).

3.1.3. Stimuli

Different stimuli were used in the included studies. Four studies used simple tone stimuli [18,21,33,53]; two studies used speech and tone stimuli [29,54]; two studies used speech stimuli [44,57]; one study used simple tones with varying rise times [39]; and another study used a complex tone, which was developed by combining 12 pure tones [58]

3.1.4. Recorded ERPs

Among the studies, only two investigated all three T-complex components (Na-Ta-Tb) [39,57]. Ta and Tb were investigated in two studies [23,54]. In other investigations, only one peak was of interest. For instance, Ta was the sole component examined in two studies [29,53], while some studies reported only the pattern of Tb [18,21]. Additionally, Na was explored in three studies [39,57,58].

Responses recorded over fronto-central sites were reported in five studies. One reported on P1 [53]; four studies reported on N1 (also called N1b) [21,23,39,58]; and one reported on P2 [39].

3.1.5. Findings

Overall, the review of findings revealed abnormal T-complex responses in children with neurodevelopmental disorders. This pattern signifies neural auditory dysfunction localized in the temporal lobe across multiple neurodevelopmental disorders. Most critically, compared to the T-complex, only two studies reported atypical fronto-central responses in children with neurodevelopment disorders [21,23]. Smaller amplitudes of N1 and longer latencies of N1 were observed in children with autism [21] and LI [23] compared to those in TD, respectively. The details of the results of each study are presented in Table 1.

Regarding the T-complex, it seems that both the latency (longer and/or shorter) [21,23,54,57,58] and amplitude (smaller and/or larger) [18,29,53,55,57,58] of the T-complex showed atypical patterns. Interestingly, specific deviations were observed in various components of the T-complex across different disorders. For instance, an atypical Tb was observed in the dyslexia group, despite a normal Na and Ta [39]. Na and Tb were abnormal in another study on dyslexia [58]. The Ta component was most affected in populations with language impairment [29,55,57] and ADHD [53]. Studies on autism and DS indicated atypical Tb components [21,54]. Furthermore, findings indicated discrepancies between T-complex and fronto-central responses in studies investigating dyslexia [39,58], language impairment [23], ADHD [53], and autism [21]. There were abnormal patterns of the T-complex, despite normal fronto-central responses [39,58].

4. Discussion

This study reviewed the evidence of changes in T-complex and fronto-central responses in neurodevelopmental disorders. Subsequently, the findings on Na, Ta, and Tb patterns were elaborated on, as well as the different patterns observed between the T-complex and the fronto-central responses.

4.1. Na Pattern

Na represents the early stage of the acoustical processing of sounds [28,40,47]. In children with dyslexia, Na was larger but occurred at a similar latency compared to that in controls. This heightened response in the dyslexic population may suggest that individuals with dyslexia require greater brain activation and effort for the same early perceptual processing of auditory stimuli compared to the control group [58]. Alternatively, enhanced auditory evoked responses could be related to a failure of inhibition. Older adults normally have larger auditory evoked potentials compared to younger adults [62,63]. This age-related increased in the amplitude of the AEPs has been interpreted as a decline in the inhibitory system [64,65]. Top-down inhibition exerts a modulatory effect on sensory processing by suppressing irrelevant information from further processing [66,67]. A decreased capacity for inhibition may lead to reduced listening abilities [63,68]. This explanation may justify the larger auditory responses in children with dyslexia, as studies consistently have documented inhibitory impairments in this clinical group [69,70].

While Taylor et al. (2003) reported an effect of dyslexia on Na amplitude [58], other studies have not replicated this result [39]. Differences in stimuli complexity and experimental design may contribute to variations in the observed results across these studies. Taylor’s study employed an active paradigm involving complex stimuli composed of 12 pure tones, while Hämäläinen’s study utilized a passive paradigm featuring a single pure tone (500 Hz) with varying linear rise times [39,58]. It is therefore possible that the impact of dyslexia on Na is related to attending to complex stimuli in the study of Taylor et al., 2003. Moreover, in the study of Hämäläinen et al., 2011, despite no group effect on Na recorded in the passive condition, there was a significant effect of dyslexia on the behavioral task of discriminating stimuli with high and low rise times. In other words, the dyslexia group performed worse than the normal group when required to attend to the sound [39]. These results may suggest that the deficits lie in top-down effects, underlying neural pathways from higher centers to the auditory areas of the brain. More research and more specific study designs are warranted to differentiate between bottom-up and top-down processing in these populations.

4.2. Ta Pattern

The Ta component represents acoustical discrimination [28,47]. The Ta component had a smaller amplitude and longer latency in individuals with LI compared to the healthy control group [23]. A smaller Ta was consistent with three subsequent studies focusing on the same disorder [29,55,57]. Furthermore, Shafer et al. (2011) reported that the peak-to-peak amplitudes, including Na-Ta and Ta-Tb, were smaller in individuals with LI compared to healthy controls [55]. This suggests auditory discrimination impairments in people with LI. This deficit could lead to phonological processing disorders in this population [23,29]. Interestingly, the atypical pattern in people with LI was observed only with speech stimuli and not with tones, highlighting the impaired verbal processing in children with language disorders [29,57]. Similar to LI, the ADHD population exhibited a reduced Ta [53]. The atypical appearance of Ta, which indicates impaired auditory processing in the CANS, may suggest that auditory processing disorder can co-exist with ADHD [16,53,71,72].

Accordingly, reduced Ta amplitudes could reflect auditory dysfunction in ADHD and LI populations and suggest a robust association between language impairment and altered T-complex responses, particularly in the Ta component.

4.3. Tb Pattern

Tb is the third component of the T-complex and indexes auditory processing in secondary auditory areas [26,28,40]. Taylor et al. (2003) reported that the dyslexia group had a shorter latency of Tb compared to healthy controls [58]. This faster brain response may reflect the superficial and inappropriate processing of sound in the dyslexic population [58]. Moreover, this abnormally short latency of Tb was observed only in the right hemisphere [58]. Such findings align with neuroimaging studies reporting greater right- than left-hemisphere activity in dyslexia, which leads to faster but less accurate processing [73,74].

In children with autism, Tb was smaller and delayed compared to that in healthy controls, and the differences in Tb indexed the magnitude of the auditory impairments [18,23]. The prolonged latency of Tb may reflect slower transmission in synaptic connections of the secondary auditory areas, which may be in line with studies showing reduced blood flow in the temporal areas of this population [75,76]. Additionally, children with autism exhibited atypical inter-hemispheric differences as the intensity was modulated. Specifically, the amplitude of Tb increased more prominently in the right hemisphere than in the left hemisphere, indicating rightward lateralization. This is in contradistinction to the healthy controls, who exhibited a leftward dominance with increasing intensity [21]. This difference may reflect dysfunction in the left hemisphere and might imply the reorganization and retuning of the left and right hemispheres for amplitude processing in autism, indicating a right-hemisphere compensation for left-hemisphere dysfunction [21]. These results align with behavioral and electroencephalography (EEG) studies demonstrating a rightward lateralization of auditory processing in the autistic population [77,78].

People with Down syndrome (DS) also exhibit atypical the lateralization of auditory neural processing [54]. Specifically, Tb is delayed in people with DS. This delay is attributed to myelination deficits in this population [54]. The results also highlighted the absence of a contralateral effect on Tb. Typically, the contralateral neural pathway leads to a shorter or larger Tb response, particularly when sound is presented to the right ear, and neural activity is recorded over the left hemisphere (right ear–left hemisphere advantage of Tb) [26,36,40]. In DS, the benefit of contralateral over ipsilateral recording was not observed for Tb. These results suggest a more distributed lateralization of neural function in people with Down syndrome [54].

Lateralization is a key feature of auditory processing. Multiple studies using different techniques, including behavioral observations, functional MRI, and magnetoencephalography (MEG), have documented hemispheric lateralization at higher and lower levels of the cortex [79,80,81,82]. In other words, the functional lateralization of the brain is not limited to high-level cognitive processes like language; it starts from the lower-level neural processing of acoustical features (e.g., frequency, duration, interval, and intensity) [82,83,84]. Moreover, converging evidence illustrates that the left and right auditory cortices are asymmetrically linked to temporal and spectral processing, with the right hemisphere more sensitive to spectral features and the left to temporal features [85,86,87]. Tb may reflect the asymmetric lateralized auditory function at the level of secondary areas. Moreover, atypical development may lead to the abnormal lateralization of temporal and/or spectral processing generated in the secondary auditory cortex, which has been observed in people with autism and DS.

4.4. Discrepancy Between Patterns of T-Complex and Fronto-Central Responses

The second goal of this review was to compare the T-complex and fronto-central responses in children with developmental disorders. Three articles reported abnormal T-complex responses despite normal fronto-central responses [39,53,58]. Contrary to typically reduced amplitudes of P1 and N1 with a longer latency rise time, dyslexia did not show the latency effect on Tb amplitude [39]. Another study also demonstrated group effects on the amplitude of Na and the latency of Tb; the fronto-central response (N1b, a subcomponent of N1) did not show differences between TD and dyslexia groups [58]. In the case of ADHD, abnormal Ta responses were reported despite the normal P1 response [53]. The typical results of fronto-central responses have been similarly documented in individuals with APD [88,89]. However, in the aforementioned studies, only fronto-central responses are reported, so there is no such comparison between T-complex and fronto-central responses to confirm the current findings.

Among the included studies, two other studies indicated that the T-complex showed more sensitivity in tracking auditory dysfunction than the fronto-central response [21,23]. In LI, although similar to N1, the Tb latency was longer, and the latency difference recorded for Tb was higher than that for N1 (the difference for Tb was almost 20 ms; the difference for N1 was 5–10 ms) [23]. Moreover, in people with autism, N1b was smaller than in the standard group, but Tb was both smaller and more delayed compared to that in healthy controls [21]. Accordingly, Tb may be more sensitive to auditory impairments than the fronto-central response in LI and autism groups [21,23].

The divergent patterns observed between T-complex and fronto-central responses may serve to differentiate the origins of auditory deficits. The predominant generation of the T-complex occurs in the secondary auditory areas in the posterior and lateral parts of the superior temporal gyrus (Brodman 42 and 22) [35,42], while P1-N1-P2-N2 originates from the primary auditory areas in Heschl’s gyrus (Brodman 41) and the associated areas [35,90,91]. Therefore, an abnormal T-complex signifies the involvement of the secondary and associated auditory areas in a specific disorder. Additionally, different origins and patterns may suggest that the T-complex manifests different auditory processes that are distinct from those reflected in fronto-central responses. For instance, Tb could index abnormal processing related to varying rise time and intensity, even in the presence of normal fronto-central responses, as well as reflecting the hemispheric lateralization of auditory processing at secondary auditory areas.

4.5. Limitations and Future Direction

Although T-complex differences were related to auditory dysfunction in all experimental groups, the patterns of all components of the T-complex were not reported. Some studies investigated only one component. It is unclear if other components would show the same pattern. For instance, the study of Shafer in 2011 investigated only Ta. Na and Tb were the only components of interest in the studies of Hämäläinen et al., 2011, and Bruneau et al., 1999, respectively. More research investigating all T-complex components is warranted to confirm the results.

Also, fewer than half of the studies reported and compared both fronto-central and temporal responses. It is not clear whether the conflicting results between these two AEPs could be confirmed in other disorders. Moreover, no study has investigated and compared these responses in APD. Similar to the results of fronto-central responses in dyslexia and ADHD discussed in this review, the literature has indicated that AEPs recorded at fronto-central sites did not consistently track auditory impairments in APD groups. One reason may lie in the fact that the related studies on APD have not assessed the T-complex. Hence, researching the effect of APD on the T-complex and comparing it with the fronto-central response using different methodologies may advance the knowledge about the origins of the dysfunction in APD and introduce a consistent biomarker for APD.

5. Conclusions

This study revealed that the T-complex can index auditory processing impairments at the cortical level in various neurodevelopmental disorders, even when there is a normal pattern of the fronto-central response. These opposite patterns may emphasize the different generators between T-complex and fronto-central responses.

Also, these findings may suggest that the neural generators of the T-complex contribute to distinct auditory processes that differ from those indexed by the fronto-central response and neural generators. Atypical T-complex patterns in all investigated experimental groups may also highlight the potential of the T-complex as a sensitive biomarker for identifying auditory processing abnormalities across a range of neurodevelopmental conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.A. and F.D.-L., methodology, Z.A. and F.D.-L., validation, formal analysis, Z.A. and F.D.-L., writing—original draft preparation, Z.A., writing—review and editing, Z.A., F.D.-L., S.K. and B.R.Z.; visualization, Z.A., S.K., B.R.Z. and A.K. supervision, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), auditory evoked potentials (AEPs), auditory processing disorder (APD), autism with intellectual disability (AUT), central auditory neural system (CANS), developmental language disorder (DLD), Down syndrome (DS), Heschl’s gyrus (HG), interstimulus interval (ISI), language impairment (LI), medial geniculate body (MGB), primary auditory cortex (PAC), planum polare (PP), planum temporale (PT), intellectual disability without autism (RET), specific language impairment (SLI), stimulus onset asynchrony (SOA), superior temporal gyrus (STG), typically developing (TD).

Appendix A. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria Applied to the Scoping Review

Table A1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table A1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population (age and condition) | Children or adults, normal and neurodevelopmental disorders such as attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, language impairment, and autism | The participants were in general health and the study did not include clinical groups |

| Evaluation | T-complex | Subcortical responses (ABR), ASSR, and other late auditory responses such as MMN, P300, and N400 |

| Publication type | Peer-reviewed journals and gray literature published after 1950 and only in English | Any unscientific papers, magazines, editorials, and manuals or text in a language other than English |

| Outcome | Peak and latency of Na-Ta-Tb or Ta-Tb | No results related to T-complex components |

Appendix B. Recorded Parameters of Stimuli and ERPs

Table A2.

The stimuli and recording features of included studies.

Table A2.

The stimuli and recording features of included studies.

| Authors | Year | Title | Type (Single or Paired, Tone, Speech, or Complex Tone (Composed of Multiple Tones)) | Intensity | Transducer | Delivery and Recording | ISI or SOA | Reference | Sample Rate | Filter | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bishop, Hardiman, and Barry | 2012 | Auditory Deficit as a Consequence Rather than Endophenotype of Specific Language Impairment: Electrophysiological Evidence | Single, 1000 Hz and /bah/ | 86.5 dB SPL | Headphone | Monaural; the study did not mention the mode of stimulation | SOA, 1 s | Mastoid right or left | 500 Hz | 0.1–70 Hz |

| 2 | Bruneau, Roux, Adrien, and Barthélémy | 1999 | Auditory associative cortex dysfunction in children with autism: evidence from late auditory evoked potentials (N1 wave ± T-complex) | Single, 750 Hz tone burst | 50, 60, 70, and 80 dB SPL | Two speakers | Binaural | ISI, from 3 to 5 s | Linked earlobes | 250 Hz | NMA |

| 3 | Bruneau, Bonnet-Brilhault, Gomot, Adrien, and Barthélémy | 2003 | Cortical auditory processing and communication in children with autism: electrophysiological/behavioral relations | Single, 750 Hz tone | 50, 60, 70, and 80 dB SPL | Two speakers | Binaural | ISI, 3 to 5 s | Linked earlobes | 250 Hz | NMA |

| 4 | Gomes, Duff, Ramos, Molholm, Foxe, and Halperin | 2012 | Auditory selective attention and processing in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. | Single, four types of two standards [1000 Hz] (low channel) and two [2000 Hz] (high channel) | 82 dB SPL | Insert earphones | Monaural; the study did not mention the mode of stimulation | SOA, 850 to 1150 ms | Tip of the nose | 0.5–70 Hz | 500 Hz |

| 5 | Groen, Alku, and Bishop | 2008 | Lateralisation of auditory processing in Down syndrome: A study of T-complex peaks Ta and Tb. | Single, vowel /a/, 576 Hz for the simple tone; the complex tone was composed of four tones of 576, 1055, 2589, and 3163 Hz | 50 dB SPL | Insert earphones | Monaural, ipsi and contra conditions | ISI, 1550 ms | left mastoid | 1000 Hz | 0.1–70 Hz. |

| 6 | Hämäläinen, Fosker, Szücs, and Goswami | 2011 | N1, P2 and T-complex of the auditory brain event-related potentials to tones with varying rise times in adults with and without dyslexia. | Single, 500 Hz with varying linear rise times: 10, 30, 60, 90, and 120 ms | 75 dB SPL | Insert headphones | Binaural | ISI, 2.5–3.5 s | Vertex | 500 Hz | 0.1–200 Hz |

| 7 | Rinker | 2021 | Language Learning Under Varied Conditions: Neural Indices of Speech Perception in Bilingual Turkish-German Children and in Monolingual Children With Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) | Single, vowel [ε] | 90 dB SPL | Headphones | Binaural | ISI, 650 ms | Left earlobe | 500 Hz | 0.1–70 Hz |

| 8 | Shafer | 2011 | Evidence of deficient central speech processing in children with specific language impairment: The T-complex | Various stimuli: “the” repetition standard /E/ standard /E/ first word in a pair of words. | 65 dB SPL, 86.5 dB SPL, 86.5 dB SPL, 70 dB SPL | Insert phone | NM | ISI, 625 ms, 550 ms, 350 ms, 2000 ms | Nose | 512 Hz | 0.05–100 Hz |

| 9 | Taylor | 2003 | Neurophysiological Measures and Developmental Dyslexia: Auditory Segregation Analysis | Five complex sounds were obtained by combining 12 pure tones. Four of the stimuli were mistuned, and their third harmonic was increased by 2, 3, 8, or 16% of original values. | 70 dB SPL | Headphones | Binaural | ISI, 1.1 s | Cz | 500 Hz | 0.1–30 Hz |

| 10 | Tonnquist-Uhlen | 1996 | Topography of Auditory Evoked Long-Latency Potentials in Children with language impairment | Single, 500 Hz | 75 dB HL | Insert phone | Monaural, ipsi and contra conditions | ISI, 1.0 s | Chin | 500 Hz | 0.1–60 Hz |

dB = decibel, SL = sound level, nHL = normal hearing level, SPL = sound pressure level, Hz = Hertz, ipsi = ipsilateral, contra = contralateral, NM = not mentioned, N = number of articles, ISI = interstimulus interval, SOA = stimulus onset asynchrony, s = second, ms = millisecond.

References

- Schreiner, C.E.; Mendelson, J.R. Functional topography of cat primary auditory cortex: Distribution of integrated excitation. J. Neurophysiol. 1990, 64, 1442–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, C.E.; Cynader, M.S. Basic functional organization of second auditory cortical field (AII) of the cat. J. Neurophysiol. 1984, 51, 1284–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, S.; Morosan, P. Architecture, connectivity, and transmitter receptors of human auditory cortex. In The Human Auditory Cortex; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 11–38. [Google Scholar]

- Talavage, T.M.; Ledden, P.J.; Benson, R.R.; Rosen, B.R.; Melcher, J.R. Frequency-dependent responses exhibited by multiple regions in human auditory cortex. Hear. Res. 2000, 150, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.J.; Crespo-Facorro, B.; Andreasen, N.C.; O’Leary, D.S.; Zhang, B.; Harris, G.; Magnotta, V.A. An MRI-based parcellation method for the temporal lobe. Neuroimage 2000, 11, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moerel, M.; De Martino, F.; Formisano, E. An anatomical and functional topography of human auditory cortical areas. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geschwind, N. The Organization of Language and the Brain: Language disorders after brain damage help in elucidating the neural basis of verbal behavior. Science 1970, 170, 940–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatorre, R.J.; Evans, A.C.; Meyer, E.; Gjedde, A. Lateralization of Phonetic and Pitch Discrimination in Speech Processing. Science 1992, 256, 846–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, J.R.; Frost, J.A.; Hammeke, T.A.; Bellgowan, P.S.; Springer, J.A.; Kaufman, J.N.; Possing, E.T. Human temporal lobe activation by speech and nonspeech sounds. Cereb. Cortex 2000, 10, 512–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, H.; Cameron, S. Separating the causes of listening difficulties in children. Ear Hear. 2021, 42, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamiou, D.E.; Musiek, F.E.; Luxon, L.M. Aetiology and clinical presentations of auditory processing disorders—A review. Arch. Dis. Child. 2001, 85, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hind, S.E.; Haines-Bazrafshan, R.; Benton, C.L.; Brassington, W.; Towle, B.; Moore, D.R. Prevalence of clinical referrals having hearing thresholds within normal limits. Int. J. Audiol. 2011, 50, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canale, A.; Dagna, F.; Favero, E.; Lacilla, M.; Montuschi, C.; Albera, R. The role of the efferent auditory system in developmental dyslexia. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2014, 78, 455–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Zoppo, C.; Sanchez, L.; Lind, C. A long-term follow-up of children and adolescents referred for assessment of auditory processing disorder. Int. J. Audiol. 2015, 54, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goethals, K. Handboek voor de classificatie van psychische stoornissen DSM-5. Tijdschr. Psychiatr. 2014, 834–835. [Google Scholar]

- de Wit, E.; van Dijk, P.; Hanekamp, S.; Visser-Bochane, M.I.; Steenbergen, B.; van der Schans, C.P.; Luinge, M.R. Same or Different: The Overlap Between Children With Auditory Processing Disorders and Children With Other Developmental Disorders: A Systematic Review. Ear Hear. 2018, 39, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliadou, V.; Bamiou, D.E.; Kaprinis, S.; Kandylis, D.; Kaprinis, G. Auditory Processing Disorders in children suspected of Learning Disabilities—A need for screening? Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2009, 73, 1029–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruneau, N.; Bonnet-Brilhault, F.; Gomot, M.; Adrien, J.L.; Barthélémy, C. Cortical auditory processing and communication in children with autism: Electrophysiological/behavioral relations. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2003, 51, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Purdy, S.C.; Newall, P.; Wheldall, K.; Beaman, R.; Dillon, H. Electrophysiological and behavioral evidence of auditory processing deficits in children with reading disorder. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2006, 117, 1130–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.; Campbell, N.; Rosen, S.; Bamiou, D.-E.; Sirimanna, T.; Grant, P.; Wakeham, K. British Society of Audiology Position Statement & Practice Guidance: Auditory Processing Disorder (APD); British Society of Audiology: Seafield, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau, N.; Roux, S.; Adrien, J.L.; Barthélémy, C. Auditory associative cortex dysfunction in children with autism: Evidence from late auditory evoked potentials (N1 wave-T complex). Clin. Neurophysiol. 1999, 110, 1927–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liasis, A.; Bamiou, D.E.; Campbell, P.; Sirimanna, T.; Boyd, S.; Towell, A. Auditory event-related potentials in the assessment of auditory processing disorders: A pilot study. Neuropediatrics 2003, 34, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonnquist-Uhlén, I. Topography of auditory evoked long-latency potentials in children with severe language impairment: The T complex. Acta Otolaryngol. 1996, 116, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koravand, A.; Jutras, B.; Lassonde, M. Abnormalities in cortical auditory responses in children with central auditory processing disorder. Neuroscience 2017, 346, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, R.O.; Kumar, P.; Singh, N.K. Subcortical and Cortical Electrophysiological Measures in Children With Speech-in-Noise Deficits Associated With Auditory Processing Disorders. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2022, 65, 4454–4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolpaw, J.R.; Penry, J.K. A temporal component of the auditory evoked response. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1975, 39, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näätänen, R.; Simpson, M.; Loveless, N.E. Stimulus deviance and evoked potentials. Biol. Psychol. 1982, 14, 53–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Roychoudhury, A.; Campanelli, L.; Shafer, V.L.; Martin, B.; Steinschneider, M. Representation of spectro-temporal features of spoken words within the P1-N1-P2 and T-complex of the auditory evoked potentials (AEP). Neurosci. Lett. 2016, 614, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D.V.; Hardiman, M.J.; Barry, J.G. Auditory deficit as a consequence rather than endophenotype of specific language impairment: Electrophysiological evidence. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Singh, S.; Arun, P.; Kaur, D.; Bajaj, M. Event-Related Potential Analysis of ADHD and Control Adults During a Sustained Attention Task. Clin. EEG Neurosci. 2019, 50, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdy, S.C.; Kelly, A.S.; Davies, M.G. Auditory brainstem response, middle latency response, and late cortical evoked potentials in children with learning disabilities. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2002, 13, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan Hassaan, M. Auditory evoked cortical potentials with competing noise in children with auditory figure ground deficit. Hear. Balance Commun. 2015, 13, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlén, I.T.; Borg, E.; Persson, H.E.; Spens, K.E. Topography of auditory evoked cortical potentials in children with severe language impairment: The N1 component. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1996, 100, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCallum, W.C.; Curry, S.H. The form and distribution of auditory evoked potentials and CNVs when stimuli and responses are lateralized. Prog. Brain Res. 1980, 54, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponton, C.; Eggermont, J.J.; Khosla, D.; Kwong, B.; Don, M. Maturation of human central auditory system activity: Separating auditory evoked potentials by dipole source modeling. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2002, 113, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacace, A.T.; Dowman, R.; Wolpaw, J.R. T complex hemispheric asymmetries: Effects of stimulus intensity. Hear. Res. 1988, 34, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clunies-Ross, K.L.; Campbell, C.; Ohan, J.L.; Anderson, M.; Reid, C.; Fox, A.M. Hemispheric asymmetries in rapid temporal processing at age 7 predict subsequent phonemic decoding 2 years later: A longitudinal event-related potential (ERP) study. Neuropsychologia 2018, 111, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, J.F. The influence of stimulus intensity, contralateral masking and handedness on the temporal N1 and the T complex components of the auditory N1 wave. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1993, 86, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hämäläinen, J.A.; Fosker, T.; Szücs, D.; Goswami, U. N1, P2 and T-complex of the auditory brain event-related potentials to tones with varying rise times in adults with and without dyslexia. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2011, 81, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneau, N.; Bidet-Caulet, A.; Roux, S.; Bonnet-Brilhault, F.; Gomot, M. Asymmetry of temporal auditory T-complex: Right ear-left hemisphere advantage in Tb timing in children. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2015, 95, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M.A.; Volkov, I.O.; Mirsky, R.; Garell, P.C.; Noh, M.D.; Granner, M.; Damasio, H.; Steinschneider, M.; Reale, R.A.; Hind, J.E.; et al. Auditory cortex on the human posterior superior temporal gyrus. J. Comp. Neurol. 2000, 416, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherg, M.; Von Cramon, D. Evoked dipole source potentials of the human auditory cortex. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1986, 65, 344–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinschneider, M.; Liégeois-Chauvel, C.; Brugge, J.F. Auditory evoked potentials and their utility in the assessment of complex sound processing. In The Auditory Cortex; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 535–559. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, D.V.; Anderson, M.; Reid, C.; Fox, A.M. Auditory development between 7 and 11 years: An event-related potential (ERP) study. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e18993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonnquist-Uhlen, I.; Ponton, C.W.; Eggermont, J.J.; Kwong, B.; Don, M. Maturation of human central auditory system activity: The T-complex. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2003, 114, 685–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clunies-Ross, K.L.; Brydges, C.R.; Nguyen, A.T.; Fox, A.M. Hemispheric asymmetries in auditory temporal integration: A study of event-related potentials. Neuropsychologia 2015, 68, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, M.; Shafer, V.L.; Haxhari, E.; Kiprovski, K.; Behrmann, K.; Griffiths, T. Stability of the Cortical Sensory Waveforms, the P1-N1-P2 Complex and T-Complex, of Auditory Evoked Potentials. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2017, 60, 2105–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-De-La-Peña, M.T. Effects of intensity and order of stimuli presentation on AEPs: An analysis of the consistency of EP augmenting/reducing in the auditory modality. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1999, 110, 924–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čeponien≐, R.; Cheour, M.; Näätänen, R. Interstimulus interval and auditory event-related potentials in children: Evidence for multiple generators. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. Potentials Sect. 1998, 108, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, H.; Duff, M.; Ramos, M.; Molholm, S.; Foxe, J.J.; Halperin, J. Auditory selective attention and processing in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2012, 123, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groen, M.A.; Alku, P.; Bishop, D.V. Lateralisation of auditory processing in Down syndrome: A study of T-complex peaks Ta and Tb. Biol. Psychol. 2008, 79, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafer, V.L.; Schwartz, R.G.; Martin, B. Evidence of deficient central speech processing in children with specific language impairment: The T-complex. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2011, 122, 1137–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, D.M.; Rothe-Neves, R.; Melges, D.B. Long-latency event-related responses to vowels: N1-P2 decomposition by two-step principal component analysis. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2020, 148, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinker, T.; Yu, Y.H.; Wagner, M.; Shafer, V.L. Language Learning Under Varied Conditions: Neural Indices of Speech Perception in Bilingual Turkish-German Children and in Monolingual Children With Developmental Language Disorder (DLD). Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 706926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.J.; Batty, M.; Chaix, Y.; Démonet, J.-F. Neurophysiological measures and developmental dyslexia: Auditory segregation analysis. Curr. Psychol. Lett. Behav. Brain Cogn. 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpaw, J.; Penry, J. Hemispheric differences in the auditory evoked response. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1977, 43, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldorff, M.G.; Hillyard, S.A. Modulation of early auditory processing during selective listening to rapidly presented tones. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2003, 79, 170–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, B.; Mealings, K. Developing the auditory processing domains questionnaire (APDQ): A differential screening tool for auditory processing disorder. Int. J. Audiol. 2018, 57, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alain, C.; Chow, R.; Lu, J.; Rabi, R.; Sharma, V.V.; Shen, D.; Anderson, N.D.; Binns, M.; Hasher, L.; Yao, D.; et al. Aging Enhances Neural Activity in Auditory, Visual, and Somatosensory Cortices: The Common Cause Revisited. J. Neurosci. 2022, 42, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoli, S.; Probst, R. Lack of standard N2 in elderly participants indicates inhibitory processing deficit. NeuroReport 2005, 16, 1933–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amenedo, E.; Díaz, F. Aging-related changes in processing of non-target and target stimuli during an auditory oddball task. Biol. Psychol. 1998, 48, 235–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindenberger, U.; Baltes, P.B. Sensory functioning and intelligence in old age: A strong connection. Psychol. Aging 1994, 9, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allman, J.; Miezin, F.; McGuinness, E. Stimulus specific responses from beyond the classical receptive field: Neurophysiological mechanisms for local-global comparisons in visual neurons. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1985, 8, 407–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dustman, R.E.; Snyder, E.W.; Schlehuber, C.J. Life-span alterations in visually evoked potentials and inhibitory function. Neurobiol. Aging 1981, 2, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceponiene, R.; Westerfield, M.; Torki, M.; Townsend, J. Modality-specificity of sensory aging in vision and audition: Evidence from event-related potentials. Brain Res. 2008, 1215, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscaldi, M.; Fischer, B.; Hartnegg, K. Voluntary saccadic control in dyslexia. Perception 2000, 29, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facoetti, A.; Paganoni, P.; Turatto, M.; Marzola, V.; Mascetti, G.G. Visual-spatial attention in developmental dyslexia. Cortex 2000, 36, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkley, R.A. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, self-regulation, and time: Toward a more comprehensive theory. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 1997, 18, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, B.F.; Ozonoff, S. Executive functions and developmental psychopathology. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1996, 37, 51–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.C.; Frisk, V.; Taylor, M.J. Neurophysiological measures of reading difficulty in very-low-birthweight children. Psychophysiology 1999, 36, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simos, P.G.; Breier, J.I.; Fletcher, J.M.; Bergman, E.; Papanicolaou, A.C. Cerebral mechanisms involved in word reading in dyslexic children: A magnetic source imaging approach. Cereb. Cortex 2000, 10, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zilbovicius, M.; Boddaert, N.; Belin, P.; Poline, J.B.; Remy, P.; Mangin, J.F.; Thivard, L.; Barthélémy, C.; Samson, Y. Temporal lobe dysfunction in childhood autism: A PET study. Positron emission tomography. Am. J. Psychiatry 2000, 157, 1988–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohnishi, T.; Matsuda, H.; Hashimoto, T.; Kunihiro, T.; Nishikawa, M.; Uema, T.; Sasaki, M. Abnormal regional cerebral blood flow in childhood autism. Brain 2000, 123 Pt 9, 1838–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prior, M.R.; Bradshaw, J.L. Hemisphere functioning in autistic children. Cortex 1979, 15, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, J.G. EEG and neurophysiological studies of early infantile autism. Biol. Psychiatry 1975, 10, 385–397. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, T.D.; Johnsrude, I.; Dean, J.L.; Green, G.G. A common neural substrate for the analysis of pitch and duration pattern in segmented sound? Neuroreport 1999, 10, 3825–3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatorre, R.J.; Evans, A.C.; Meyer, E. Neural mechanisms underlying melodic perception and memory for pitch. J. Neurosci. 1994, 14, 1908–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.L.; Peretz, I.; Zatorre, R.J. Evidence for the role of the right auditory cortex in fine pitch resolution. Neuropsychologia 2008, 46, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, H.; Kakigi, R. Hemispheric asymmetry of auditory mismatch negativity elicited by spectral and temporal deviants: A magnetoencephalographic study. Brain Topogr. 2015, 28, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.; Hjortkjær, J.; Santurette, S.; Zatorre, R.J.; Siebner, H.R.; Dau, T. Subcortical and cortical correlates of pitch discrimination: Evidence for two levels of neuroplasticity in musicians. Neuroimage 2017, 163, 398–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatorre, R.J.; Delhommeau, K.; Zarate, J.M. Modulation of Auditory Cortex Response to Pitch Variation Following Training with Microtonal Melodies. Front. Psychol. 2012, 3, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obleser, J.; Eisner, F.; Kotz, S.A. Bilateral speech comprehension reflects differential sensitivity to spectral and temporal features. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 8116–8123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamison, H.L.; Watkins, K.E.; Bishop, D.V.; Matthews, P.M. Hemispheric specialization for processing auditory nonspeech stimuli. Cereb. Cortex 2006, 16, 1266–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zatorre, R.J. Hemispheric asymmetries for music and speech: Spectrotemporal modulations and top-down influences. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1075511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox-Thomas, L.G. Use of Amplitude and Latency Characteristics of the Auditory Late Response to Predict Performance on Behavioral Measures of Auditory Processing. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mattsson, T.S.; Lind, O.; Follestad, T.; Grøndahl, K.; Wilson, W.; Nicholas, J.; Nordgård, S.; Andersson, S. Electrophysiological characteristics in children with listening difficulties, with or without auditory processing disorder. Int. J. Audiol. 2019, 58, 704–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liegeois-Chauvel, C.; Musolino, A.; Chauvel, P. Localization of the primary auditory area in man. Brain 1991, 114 Pt 1A, 139–151. [Google Scholar]

- Näätänen, R.; Picton, T. The N1 wave of the human electric and magnetic response to sound: A review and an analysis of the component structure. Psychophysiology 1987, 24, 375–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).