Abstract

Within the circular economy, repair is increasingly recognised as a crucial yet underexplored strategy that extends product lifespans and reduces waste. Service design offers approaches to support this transition by addressing technical, social, and systemic dimensions. This review aimed to synthesise how service design contributes to repair practices and identify research gaps. Following PRISMA 2020 guidelines, we systematically searched Scopus and Web of Science, applied inclusion criteria focusing on service design and repair within the circular economy, and conducted multi-step screening and snowballing. From 132 initial records, 73 studies were included (journal articles, conference papers, book chapters). Thematic synthesis identified three areas: micro-level interactions between producers, products, and users (e.g., motivations, trust, communication); meso-level tools, frameworks, and platforms enhancing accessibility and efficiency; and macro-level societal transformation through regulations, standards, and communities. Results highlight service design’s potential to foster systemic change by integrating environmental, social, and economic aspects, while also revealing notable research gaps related to the limited engagement of repairers, policymakers, and cross-level collaboration. Compared to previous studies, this review contributes a novel integrated framework linking micro-, meso-, and macro-level dimensions of repair within the circular economy, offering both conceptual insights and actionable directions for practitioners and policymakers. The study is limited by language constraints and the lack of a formal bias evaluation. All reviewed materials are publicly accessible on OSF. This research was conducted without external financial support.

1. Introduction

There is a growing scholarly interest in how design can support circular economy processes and practices [1]. As the traditional model of rapid production and consumption no longer suffices, researchers propose strategies for closing material loops and promoting resource efficiencies and product longevity, such as repair, reuse, remanufacturing, refurbishing, and recycling [2,3,4]. Although these practices are more and more recognised, repair still remains under-prioritised compared to recycling, which is considered the most popular and studied strategy [5]. While recycling requires significant energy and resources, leading to material degradation, repair might be way more effective in relation to its potentially more limited environmental impact [5]. Consequently, the integration of repair practices into the circular economy has been widely recognised as pivotal for supporting sustainability and transitioning towards more sustainable societies.

Repair is a key strategy for product longevity, minimising waste and promoting resource efficiency [6]. Several studies emphasise the importance of modularity and designing products for easy disassembly and repair [7,8]. However, it is also evident by the rise of community-based initiatives such as repair cafés that repair is also a social practice. This highlights its educational and community engagement aspects, e.g., through practices of learning and sharing, which foster a culture of repair [9].

The goal of repair is to maintain products and prolong their life cycles, which is unfortunately often met with the persistent challenges of today’s modern world and consumerism [10]. Obstacles also include the lack of societal awareness and education on repair and its benefits [11,12,13,14,15], the increasing technological complexity, and designing for planned obsolescence [16]. That is why a more holistic approach is needed in terms of understanding repair as an integrated practice that encompasses social, economic, and environmental dimensions [17].

While much literature focuses on making the design of the product more circular and sustainable, it has been acknowledged that service design might be crucial for supporting the Circular Economy. The traditional definition of service design is that by fostering a dialogue with “the material practices of design and […] the strategic and systems-oriented approaches” [18] service design ensures that (a) users (or consumers) experience a service that is usable, meaningful, and desirable, and (b) providers can deliver an offering that is efficient, distinctive, and effective [19]. For example, service design has been applied to support circular economy processes by moving beyond product-oriented solutions and providing sustainable consumption models that extend product life cycles through services like rent, repair, and maintenance [20]. However, an increasing number of studies stress how the scope of design has changed in the past decades, expanding from narrow product-focused solutions to broader, systems-oriented interventions that incorporate socio-technical elements [1,21]. In other terms, traditionally, service design was used to envision, design, implement and improve a specific service (e.g., the service provided by a repair café); lately, service design—and especially its capacity to facilitate multi-stakeholder co-creation process—is increasingly used in much broader and complex contexts, such as the definition and the deployment of business processes, environmental policies, organisational governance mechanisms, frameworks for community engagements and capacity building, etc. [22].

While abundant literature has provided considerations on the role of design in addressing the interconnected social, economic, and technical challenges for the transition to more sustainable and circular societies (e.g., starting from the classic work of [23]), systematic studies on the various ways in which service design can specifically support repair practices are sparser. We aim to cover this gap by addressing the following research question: How can service design be used to support repair practices?

Our systematic literature review (73 papers examined) has shown three thematic areas through which service design is and can be used to support repair practices (1) micro level: interaction between the producers/products and the users within a repair system (e.g., how a producer could stress the importance of repairing its products through its customer service) (2) meso level: tools, process frameworks and platforms that support repair practices (e.g., data-driven management systems could provide a more granular understanding of inventories and repair processes and, thus, support repair practices) (3) macro level: societal transformation towards repair practices (e.g., services that could support companies while transitioning from their traditional product-centric approach towards more service-centric approaches. The remainder of the review is composed as follows: our systematic research methodology is defined in Section 2. In Section 3, the above-mentioned thematic areas are presented, followed by Section 4, which highlights the most important findings for discussion, as well as implications for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Systematic Literature Review

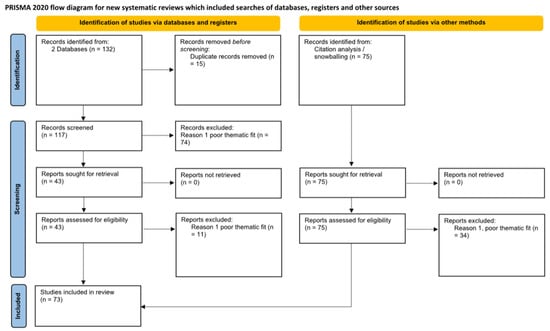

The review process adhered to the PRISMA guidelines to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and methodological rigour [24,25,26]. Thus, it was articulated into six distinct steps: developing keywords and search strings, removing duplicates, screening articles, assessing full-text eligibility, employing snowballing to locate additional studies, and conducting final analysis and categorization Figure 1. This structured methodology ensures a thorough and methodical evaluation of the literature. This literature review presents a comprehensive overview of the research published until November 2024. The PRISMA 2020 Checklist [26] (Supplementary Files S1 and S2) for this review is available in the online OSF repository (https://osf.io/w4pxg/?view_only=29a6a21ba0274e909e56e1460bdc4938, accessed on 15 October 2025).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram, which reports the number of articles examined through the chosen systematic review protocol.

2.2. Development of Keywords, Search Strings, and Identification of Relevant Articles

The two databases—Scopus and Web of Science (WoS), acknowledged as leading resources for scholarly searches, facilitated our structured keyword query, connected to service design for repair practices. They encompass a broad spectrum of research fields, including sustainability [27].

First, we tried to use combinations of the terms ‘repair’ or ‘design’; however, this provided a very large and unmanageable number of results, where most were irrelevant to the research scope. Instead, we applied a more focused keyword search string approach. Keywords were then iteratively tested and refined for relevance and specificity. They addressed repair practices, service design, and the circular economy. Some of them, including synonyms and alternative terms, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Keywords used in the search strings.

The complete search strings are located in the online repository: https://osf.io/w4pxg/?view_only=29a6a21ba0274e909e56e1460bdc4938 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

The total number of articles acquired was 132. This number was then transferred to Zotero, which makes it possible to identify duplicates, in our case, 15, leading to 117 remaining papers. They included journal articles, conference papers, and book chapters, all of which were either written in or translated into English.

2.3. Screening, Eligibility, and Snowballing

Aligned with the Prisma framework, we carried out a structured multi-step exclusion process. Records were excluded primarily for poor thematic fit. Typical cases were studies that (i) treated repair purely as a technical/material problem without a service-design perspective, (ii) addressed other circular strategies (e.g., recycling or remanufacturing) without explicit links to repair practices, or (iii) discussed after-sales services, maintenance, or usability without design/service implications for repair within the circular-economy frame. Thereafter, an additional 41 papers were added through snowballing. Starting from the final set of included “seed” papers, we conducted backward snowballing (screening the reference lists of each seed) and forward snowballing (identifying records that cite each seed). Screening proceeded at title/abstract and, where needed, full text. Records were retained only if they met our thematic scope—repair within the circular-economy frame with an explicit service/design lens—and our publication-type criteria (peer-reviewed journal articles, scholarly conference proceedings, or chapters in academic edited volumes). This final step helped track how certain concepts evolved in the literature as well as make sure important contributions are not overlooked. With this addition, the total number of articles reached 73. Across the review corpus, we included peer-reviewed journals (e.g., Journal of Cleaner Production, Journal of Business Research, Journal of Consumer Research, Sustainability) and scholarly conference proceedings (ACM DIS, Design Society/Proceedings of the Design Society, Springer LNCS) plus chapters in edited scholarly books. Records of the material reviewed can be located here: https://osf.io/w4pxg/?view_only=29a6a21ba0274e909e56e1460bdc4938 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

2.4. Thematic Areas

Aligned with the Prisma framework, we carried out a structured multi-step exclusion process. Firstly, the titles were screened, followed by the abstracts of the papers. The ones that were considered irrelevant to the focus of the review were filtered out. For instance, if a study featured repair, but not in the context of service design within the circular economy, it was excluded.

Our categorization process involved the following steps [28,29]:

- Open coding phase: The authors independently reviewed the full text of each article and assigned preliminary, freely generated labels to capture the key concepts emerging from the data.

- Grouping: These individual codes were then organised into broader, higher-order headings that reflected recurring patterns and themes.

- Categorization: Finally, all authors met to compare, discuss, and consolidate their individual coding results. Through iterative discussions, discrepancies were examined and resolved by consensus to ensure shared understanding and consistency. While formal inter-rater reliability testing was not conducted, the process of first coding independently and then jointly reviewing and reconciling the outcomes strengthened the credibility and reliability of the analysis by accounting for multiple perspectives and reducing individual bias.

Our final categories are:

- 1.

- Interaction between the producers/products and the users within a repair system (also connected to users’ perceptions and behaviour). It entails research studying the repair micro-level interactions. This category has to do, for example, with how companies can communicate to the users the importance of repairing some of their products;

- 2.

- Tools, process frameworks, and platforms for repair practices. The focus is on the repair infrastructure. An example would be an online platform where people can schedule repairs, order spare parts, or watch tutorials for DIY fixes;

- 3.

- Societal transformation towards repair practices (regulations, norms, standards, culture, communities). Macro-level aspects, such as policies or industry standards that influence repair practices, such as laws supporting the ‘Right to Repair’, which ensure customers’ access to tools, spare parts, and repair information [30,31]. This category acknowledges that services are framed by societal norms, regulations, and historical contexts.

It is important to note that these are not rigid categories. Instead, they are more suggestive interpretive devices. Some papers could, for example, fall within more than one category. As such, in the rest of the paper, we will use the term ‘thematic areas’ rather than ‘categories’.

2.5. Limitations

Database coverage, indexing lags, and language constraints may have led to selection bias. Although we used multiple databases and snowballing (backward/forward), relevant work in languages other than English or in region-specific venues may be missing, which can particularly affect findings on cultural factors, informal repair economies, or local policy experiments. Chances are that sources like Google Scholar or the ACM Digital Library might have provided further relevant work, including grey literature. In addition, the time window emphasised recent work (2020–2024), strengthening topicality but risking temporal bias. Earlier foundational contributions that did not use contemporary terminology (e.g., “service design,” “PSS,” “circular economy”) may have been under-captured even if their insights are still applicable.

3. Results

3.1. Interaction Between the Producers/Products and the Users Within a Repair System (Also Connected to Users’ Perceptions and Behaviour)

Consumer behaviour plays a vital role in sustainable practices, such as repair, as consumers decide whether and how they will interact with a service or a product. Therefore, their behaviour has a big impact on companies’ strategies [32], shaping the demand for sustainable products. Ref. [1] argue that designing for product repair and maintenance is not enough, as consumers also need motivation to care for their products.

Extensive literature highlights user-side barriers and motivations for repair, including emotional attachment, care, confidence, and trust in repair services. According to [32], consumers’ decisions are influenced by intrinsic and extrinsic motivations as linked to different product categories, with electronics, fashion, and household appliances being the most studied sectors [32]. Some of the main motivators or demotivators for engaging in circular strategies, depending on the context, are financial and environmental benefits [11,12,32,33,34,35]. Ref. [32] argue that these benefits should be communicated persuasively by the producers, e.g., also paying attention to brand communication as a way to promote transparency and trust [2,11,13].

Companies should establish services that communicate that repair goes beyond merely fixing an object and highlight it as a means of preserving and enhancing symbolic, economic, and functional value [36,37]. For this, storytelling through case studies, success stories, calls to action, and product demonstrations can be critical [11]. When service providers manage expectations and communicate clearly about how an item’s physical properties might affect repair outcomes, customers respond positively [36]. Thus, service providers need to be transparent about repair challenges but also empathetic toward customers’ attachment to their items, accommodating their needs [37]. In contrast, poor customer service or unsuccessful repairs reduce trust [2].

Involving customers in repair processes and workshops can encourage material care and empathy [11]. Nostalgia is an emotional driver for repair among both customers [13,16] and repair volunteers [38]. This fosters positive brand perception and could be leveraged in services that foster communication strategies to build trust [13]. Consumers who previously had positive repair experiences and trusted the service provider are more likely to repair again [35]. Emotional factors such as guilt and pride are key drivers of repair, yet customers often neglect functionality [2], reflecting a lack of material care.

Perceived product quality is an integral part of repair, prompting users to either dispose of or repair their products [13,38,39,40,41,42]. Manufacturers could use this information to evoke customers’ perceptions of the product quality [13]. Consumers are motivated to repair products when they perceive high value or have paid a significant amount of money [32,37,43]. Cheap products are less likely to be repaired, even by repair workers in volunteer cafes [38]. However, this is not always the case for fashion consumers. Ref. [44] highlight the issue of overconsumption in fashion, rooted in consumer behaviour. Young consumers, driven by fashion trends to gain social acceptance, often engage in impulse purchasing and rely on attire for their identity and self-expression. Paradoxically, as sustainability awareness rises, some repair their fast-fashion garments due to attachment, despite lower quality. This shows the need to challenge market norms by fostering emotional attachment to garments instead of trends.

Consumers who have developed recycling habits are more inclined towards repair [44]. However, the vast focus on recycling over repair highlights the need to raise awareness about repair’s impact and benefits. Producers should develop more services that address common barriers to repair, including a lack of knowledge, education, and information about sustainable practices, circularity, or repair steps [11,12,13,14,15]. Simple designs and flexible materials enhance resourcefulness, while complexity discourages it [15,45]. If clear information about repairability is not provided, people are less likely to attempt repair [33,46].

Being part of a community and feeling socially accepted are vital for consumers to adopt strategies such as repair [32,37,44]. Ref. [38] highlight the social aspects as emotional drivers of repair, also among volunteers. Repair cafes, in turn, while promoting anti-consumerism and fostering community, are not always financially accessible, mainly attracting individuals driven by their beliefs and able to afford repair [43]. As previously pointed out, product cost, quality, lack of transparency, and trust can act as significant demotivators for consumers [11,12,32]. For this purpose, financial and environmental benefits, along with persuasive communication, play essential roles in driving repair [32,44].

Repair fosters creativity, as highlighted by [11], through stakeholder involvement, feedback, and user-centric approaches. Looking at repair as an act of creativity drives consumers to repurpose objects [39].

Electronics are currently the fastest-growing category of waste globally, partly due to their increasing complexity, which often leads to hibernation [10,16,32,47]. IoT devices are a major part of this problem due to their lack of repairability and consumer attachment to the products. In contrast, gaming devices foster deep emotional connections through shared experiences, seamless design, and meaningful interactions, driving repair attempts [16]. According to [16], understanding this connection can help inspire design for emotional durability in IoT products as well.

3.2. Tools, Process Frameworks, and Platforms for Repair Practices

Repair is not a new concept; it was once the norm, and it is now being revisited as a valuable process for design and innovation [48,49]. Studies show how service design can play a critical role in improving and rethinking how these systems and practices function [49]. Refs. [49,50] note that integrated Product-Service Systems can be used to shift the focus to addressing human needs through user-centred design, enhance asset utilisation, and reduce operational inefficiencies. They suggest that repair and maintenance can help companies gain a competitive advantage and sustain economic efficiency.

Ref. [51] stresses how interactive platforms or workshops providing clear and engaging information work well to inspire product care in users. Much of the literature on repair processes, frameworks, and platforms comes from studies on electronics, which also highlight the challenges brought by technological complexity [52]. Methods like push notifications or changing a product’s appearance or functionality to signal the need for maintenance or repair can be used to raise awareness. These knowledge-sharing platforms may communicate economic aspects, and highlighting the positive effects of repair—such as a product’s renewed functionality, longer lifespan, or reduced environmental impact—can motivate users to take action [51,53,54]. Social connection is another key strategy, fostering shared ownership through community repair events or collaborative platforms [51]. Offering flexible services that provide all necessary tools and guidance for repair, as well as allowing users to personalise or modify their products creatively, encourages long-term engagement and care [37,48]. To align repairability goals with user demands, it is crucial to involve users in the design process [55].

Ref. [11] argue that technology plays a vital role in facilitating innovation and transparency, as well as influencing behavioural change, through customisation and enhanced service efficiency. They also highlight the importance of collaboration across the value chain through a seamless process for creating value and promoting sustainability. They point out how partnering with a ‘disassembly-ready’ company might be a valuable and innovative strategy. Moreover, there is a need for consumer involvement in the growth at the end of a product’s lifecycle. According to [56], the shift from offering products to product-service systems, however, comes with many challenges, such as high labour costs, long-term risks, and insufficient revenue to cover expenses. That is why resistance to these service-based models is often observed in sales teams, customers, and organisational culture. Recurring themes in the literature related to these challenges include cost and speed optimisation [57], as well as service efficiency in repair.

Ref. [58] propose a bi-objective model (addressing two conflicting objectives) for post-sales and repair service networks, aiming to enhance customer satisfaction by minimising both delays and costs. Furthermore, an effective solution to the problem of cost, besides tax reduction, would be the introduction of financial incentive systems such as cash refunds or repair vouchers [12].

Ref. [59] look at the competition between manufacturers and repair providers, proposing a mathematical framework (game theory) for optimising repairability, costs, and economic feasibility. Ref. [60] emphasise efficiency by improving the design manuals for repair professionals. They note that making manuals more readable, including clearer graphics, improved organisation, and standardised terminology, can increase safety, prevent inefficiencies, accidents, and delays, as well as boost user satisfaction.

The emphasis on repairability and efficiency links directly to the need for better service planning and resource management in repair systems. Ref. [61] highlight that poor planning of repair centre locations, as well as resource allocation, can lead to delays and higher costs. For this purpose, they address these inefficiencies through a mathematical (location-allocation) model, which considers transportation costs and service coverage. Another planning tool is suggested by [62], who point out barriers in ship repair planning, such as poor scheduling, lack of coordination between shipyards and shipowners, and ineffective communication. These obstacles lead to delays, increased costs, and lost opportunities for operational improvement. They propose a web-based application that connects shipyards and shipowners, supporting scheduling, project management, and real-time progress reporting. Similar concerns about managing repair requests are raised by [63], who offer mathematical algorithms for service optimisation. In addition to resource allocation and service planning challenges, geographical location also significantly affects repair accessibility: urban areas offer more repair options, whereas rural regions often depend on self-repair [64]. This underscores the importance of solutions that bridge this gap.

To further promote effective repair practices, consumer trust and operational efficiency can be fostered by providing standardised tools and accessible toolkits to support both consumers and (semi-)professional repairers [12,43]. These should go beyond plain text, but in the form of multimedia, such as audio or video support [65]. Thus, Ref. [47] argue that, in order to foster trust in users, repairers need to be experienced and honest about the cost and to keep the consumer’s items safe. Furthermore, users need to access services where they can easily receive support from manufacturers, to raise the chances of repair instead of replacement [65]. Products are getting more and more difficult to repair. According to [43], some are designed for recycling rather than reassembly or are excessively miniaturised. In contrast, products designed for disassembly minimise repair time and associated costs [46]. According to [36], tools need to be updated to address the evolving repair needs of today’s less repairable items, while a tidy and organised environment within repair facilities demonstrates professionalism and care. Ref. [40] discuss product information management and suggest developing ‘Design for Repair’ practices supported by robust data management systems to provide stakeholders with technical and logistical information on product usage.

Ref. [66] note that in the service business, harvesting parts for reuse and repair is not as common as in the production of devices. They propose a framework for the systematic assessment of harvesting processes, using equipment from the medical sector to validate and demonstrate how it can be applied to other industries with similar high-value and regulation-intensive contexts. Ref. [67] also review medical diagnostic equipment and offer a design for reverse logistics operations to minimise costs and save repair services time. Aside from what has already been mentioned, Refs. [68,69] discuss proposals for efficient maintenance, balancing costs, repair capacity, and inventory levels in the context of supply chains for systems that need repairs, such as aircraft engines and automobiles. An example of two efficient repair systems is presented by [70], who address issues in a telephone repair network process through two components: ‘Mechanized Loop Testing’, implemented to diagnose and test telecommunication lines, and the ‘Automated Repair Service Bureau’, which combines the ‘MLT’ tool with human performance design techniques to enhance telecommunication repair services [71,72].

Furthermore, Ref. [73] propose the ReSOLVE (Regenerate, Share, Optimise, Loop, Virtualise, and Exchange) framework for reducing costs and enhancing corporate social responsibility, meant to set an example for other businesses to adopt similar circular practices. This example of innovating in the realm of the circular economy incorporates strategies like renewable energy, repair services, modular design, recovery mechanisms, virtual platforms, and 3D printing.

Lastly, according to [74], the layout of a repair touchpoint is important, as it can become a space for workshops and events, community skill and knowledge sharing, object exchange and education, thus addressing many barriers to repair. That is why these spaces need to be thoughtfully designed, offering repair stations equipped with tools to empower self-repair, bookcrossing spaces, and flexible and movable furniture that adapts to different activities. Such hybrid spaces combine socialising and learning, ensuring a dynamic environment in which users are actively involved. Aesthetics and branding, including elevated second-hand objects, can help reinforce the values of repair and sustainability.

3.3. Societal Transformation Towards Repair Practices (Regulations, Norms, Standards, Culture, Communities)

As concluded from the previous sections, achieving sustainable systems and fostering a shift towards a repair culture requires more than just improving specific interactions between producers and users [50,75]. Instead, systemic changes are necessary, including the establishment of appropriate laws, infrastructure, and efforts to support repair practices [50,75,76]. Studies suggest drawing inspiration and expertise from fields such as business, design, consumer behaviour, and system innovation [17]. The literature highlights the importance of strategic planning, balancing financial and social aspects [11], and aligning consumer needs with business motivations [75].

Ref. [77] underscores the need for a methodological framework to adopt product-service systems, emphasising the evaluation of their economic, environmental, and social impacts with a life-cycle perspective. Companies must be supported in navigating structural and strategic shifts, such as altering production and marketing strategies. Ref. [78] proposes paradigm E, which integrates repair knowledge into a broader circular strategy encompassing ecology, the environment, energy, economy, empowerment, education, and excellence. This approach aims to embed environmental sustainability into manufacturing and achieve sustainable growth. Shifting from eco-design to circular economy design means keeping products and materials in use longer through repair, remanufacture, or recycling [79]. Service design plays a crucial role by promoting worker empowerment, integrating environmental responsibility, and prioritising customer-centric design and education.

Ref. [31] point out key obstacles to the repair of consumer electronics, including restrictive intellectual property laws and misleading warranty practices. Refs. [30,31] suggest achieving this through policy reform campaigns and design principles that emphasise repairability and disassembly, as well as by fostering intellectual property and contract laws to prioritise repair, extending warranty periods, and enforcing consumer rights [31]. Ethical responsibility, beyond profit concerns, should be encouraged among companies [12]. Mandatory regulations simplifying repair processes would not only benefit customers but also encourage businesses to integrate repair services into their strategies, serving as a competitive advantage for companies that align their brand image with ethical legislation [2,11,80]. However, greenwashing presents a notable obstacle in fostering genuine change [11].

At a cultural level, the constant pursuit of newness in modern design could be challenged by repair, turning flaws into opportunities with the help of creativity [81]. Repair should be seen as more than a functional activity; it should encompass care for objects, materials, and people [17]. This could be achieved when designers, educators, and policymakers prioritise it and provide communities with the necessary skills and systems for it to move to the forefront of sustainable living [10]. Materiality is often overlooked in services, as previously mentioned, particularly by fashion-sensitive individuals who value the trendy aspects of garments over the garments themselves. This neglect stems from a consumption-driven ethos prioritising the user over the material [36]. Consumers place emotional and symbolic value on products without demonstrating care for the material, whereas fostering an ethos of repair involves respect, empathy, care, and responsibility toward materials, treating them as stakeholders in service processes. Brands can promote sustainability by collaborating with repair service providers, offering guarantees for repairable products, and training employees in material empathy, instead of focusing entirely on consumption journeys [36]. They can also show a willingness to attempt repairs instead of offering replacements or compensation. Thus, employees who demonstrate material empathy should be prioritised in hiring to set an example and foster an ethos of repair. Training employees to adapt to heterogeneity and rewarding them for their creativity can facilitate innovation within repair systems and organisations [36].

Repair has the potential to rebuild not only relationships with objects but also social bonds, as well as create a sense of community and shared purpose by fostering care, engagement, knowledge sharing, and empowerment [17,47,82,83]. Local governments must recognise these “commoning” practices as vital to the circular economy and view individuals beyond the narrow lens of consumerism [55]. Furthermore, Ref. [84] state that a cultural shift towards repair requires focusing on people and communities rather than just technological innovations. Humans need to be actively involved in the co-creation of sustainable systems, prioritising relational repair and connecting with others, places, and nature through community hubs and initiatives that address their unique needs.

Ref. [85] criticise the current understanding of design for repair that focuses on physical durability and short-term consumer needs. According to the authors, the Right to Repair movement addresses only a fraction of the problem of product obsolescence by oversimplifying it and shifting the responsibility to consumers rather than to global corporate systems: “all this must be considered: the context of globalised mass-manufacturing, the complexity of global supply chains, and the general expectations of high-throughput production and constant releases of new models, alongside the pressure for low production costs and low labour costs, the social influences on user behaviour—these elements together produce patterns of swift product discard.” (p. 29 [85]) suggest that some ways in which designers could effectively approach this problem are through designing for unfinished products and resilience, with a long-term vision, incorporating extended producer responsibility and creating systems of shared ownership and social interdependence. Design should prioritise durability and repairability while minimising reliance on high-tech solutions [79]. This implies the incorporation of social innovation, service design, and theories of change.

Wealthier economies often prioritise convenience and new purchases, while less-developed economies adopt repair out of necessity [86]. Effective strategies for repair-focused systems must consider economic and human factors, including cultural and behavioural influences, to make the circular economy more accessible and sustainable for all. Community resilience can be built by involving diverse and vulnerable groups, such as at-risk youth, creating accessible repair spaces, and addressing both social exclusion and environmental challenges [87]. This can foster confidence, collaboration, and stronger social ties among people while reducing waste. Furthermore, repair events can promote community learning and sustainability, while stricter design regulations are also necessary [88]. Repair holds social significance, as environmental impacts disproportionately affect marginalised communities. Historical examples, such as the preserved man from the Italian Alps who practised self-repair, underscore the necessity of repair in times of scarcity [5]. According to Ref. [89], encouraging self-repair is crucial because it empowers users to take immediate action to fix their products, making repair more accessible, cost-effective, and routine, ultimately fostering a broader culture of maintenance, responsibility, and sustainability.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Role of Service Design to Support Repair Practices: Key Topics

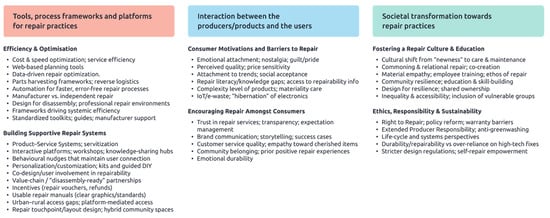

This systematic review highlights the different ways in which service design can support repair practices within the circular economy, through the lenses of three thematic areas: interaction between the producers/products and the users, tools, process frameworks, and platforms for repair practices and societal transformation towards repair practices. As illustrated in Figure 2, the keywords and concepts both guided and emerged from the development of the three analytical areas, reflecting the iterative and interpretive nature of the categorization process. Thus, the figure represents the main subthemes and underlying notions that structure each area.

Figure 2.

Visual summary of the key words and concepts that both informed and resulted from the formation of the three analytical areas, illustrating the reciprocal relationship between coding and thematic development.

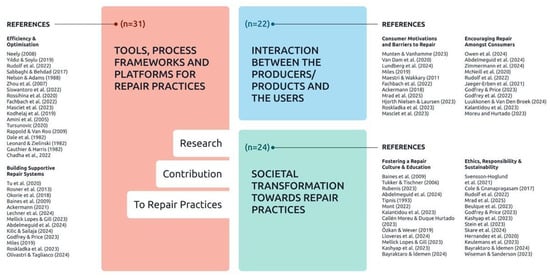

Apart from addressing repair practices from multiple perspectives, these thematic areas also demonstrate interconnectedness, which is vital in fostering a sustainable repair ecosystem, as shown in Figure 3, which also shows key topics that emerged from these thematic areas.

Figure 3.

Diagram showing how papers are related to key topics; note that some papers are linked to more than one topic. It summarises studies represented in references: [1,2,5,6,8,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,20,21,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89].

Key topics that emerged from the ‘interaction between the producers/products and the users’ were consumer behaviour and motivations, as well as suggestions to encourage repair amongst consumers. Insights from 22 studies explore emotional attachment, consumer confidence, perception, and the creative and adaptive aspects of repair. These aspects align with tools, process frameworks, and platforms for repair practices. For example, behavioural insights can inform the design of intuitive IoT-enabled devices, accessible product information systems, and supply chain integrations that simplify repair. Furthermore, they can be used to build trust and enhance engagement in repair practices. Societal transformation towards repair practices also plays a significant role in influencing consumer behaviour. The connected studies point out how community engagement, promoting social equity, and enhancing ethics and resilience within repair networks can foster repair culture. Thus, education and communication strategies are effective in raising awareness of sustainable repair practices and their benefits.

Moreover, the ‘tools, process frameworks and platforms for repair practices’ area focuses primarily on improving efficiency and optimisation within repair systems, as well as building supportive repair systems. 31 studies stress the importance of cost and operational efficiency, resource optimisation, and enhancing accessibility and convenience in repair services. For example, the development of automation tools, digital platforms, and human–computer interaction systems helps run repair processes smoothly by ensuring their accessibility and effectiveness. Thus, as previously mentioned, the integration of behaviour-driven design for product longevity helps align technology with consumer preferences, making infrastructure responsive to societal needs.

Lastly, the main topics that ‘societal transformation towards repair practices’ encompasses are fostering a repair culture and education, ethics, responsibility, and sustainability. 24 contributions study the right to repair and extended producer responsibility, as well as address premature obsolescence. These tackle the barriers to repair by not only making products repairable but also facilitating entire systems and incentives for repair. When combined with infrastructural interventions, it can facilitate the development of supportive repair systems and community-based networks.

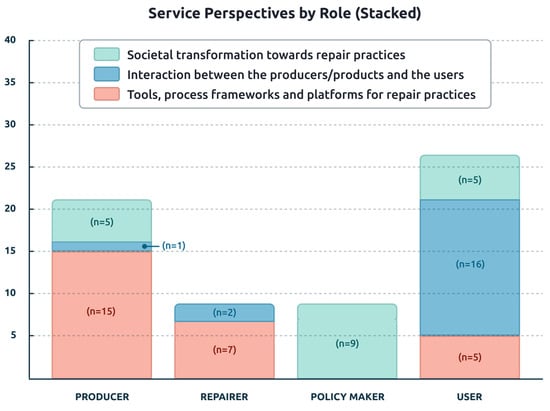

Across the three thematic areas, tools and process frameworks, interactions within the repair system, and societal transformations, we divided them according to the main stakeholder studied: producer, repairer, policymaker, or user, see Figure 4. This was done to identify gaps, areas for improvement, and potential opportunities for future research. The aggregated data helped us understand missing links and see the distribution of studied themes across stakeholders.

Figure 4.

Service Perspectives by Role: The diagram shows how some stakeholders are underrepresented.

Overall, these three thematic areas can also be understood across micro, meso, and macro levels, which are interlinked as follows: user–producer interactions (micro) inform the design of repair tools and systems (meso), which in turn operate within and are shaped by broader policies and cultural norms (macro). The graph, therefore, raises questions about some of the challenges the stakeholders might face across these levels, such as limited collaboration, unclear responsibilities, and practical barriers in integrating service design into established repair systems.

What may be evident is how some stakeholders are only studied within some thematic areas. Some are natural, such as the role of the policymaker, which is only studied within research on larger societal transformations. Authors urge policymakers to strengthen repair, highlighting the need for supportive regulations, financial incentives, inclusive infrastructures, education, and cross-sector collaboration that ensure repair is economically viable, socially equitable, and culturally embedded. One could, however, ask research questions about how and whether policymakers are informed by micro repair interactions, or what directs the system-level changes and repair policies? This issue also relates to the graph of repairers, which shows that their role in the larger societal transformations towards repair practices is not studied. While studies show repairers hold the knowledge and repair experience of products, repair practices, consumers’ motivation/barriers, etc. Ref. [38], that may be key to informing regulations, norms, and standards, however, their role in shaping this is either missing in practice or not studied by research. This gap could be relevant and interesting to explore, e.g., whether or how repairer knowledge informs regulations, norms, and standards. Also, the graph highlights that the producer aspects are heavily researched within studies on tools and frameworks. This may indicate a willingness and need from businesses for operational ways forward to identify repair solutions. However, it also raises questions of how producers may take a greater involvement in, for example, shaping the micro-interaction of repair.

The synergy of all these deeply intertwined thematic areas and topics highlights the importance of a holistic approach to service design, where all three dimensions work together to overcome current challenges in the circular economy. That way, repair can be looked at not only as a technical process but also as a social and cultural practice within the broader framework of sustainability. While few studies explicitly articulate implications for service designers, the review reveals that they might play a crucial role in connecting user motivations, systemic tools, and societal transformation. Thus, it calls for designing repair services that build trust, emotional attachment, and transparency. It further stresses the importance of developing data-driven and participatory platforms that make repair accessible and efficient, and integrating these into wider infrastructures that normalise repair as part of everyday life. In doing so, service designers are urged to move beyond product-centric interventions and take on a strategic role in shaping the behavioural, operational, and cultural conditions that enable repair-driven circularity.

4.2. Avenues for Future Research

We see multiple avenues for future research as this review is limited by language restrictions and by the fact that the findings rely on existing literature, leaving gaps in empirical validation and stakeholder perspectives, particularly from repairers and policymakers.

Our analysis reveals critical gaps in the roles and contributions of different stakeholders (producers, repairers, policymakers, and users) within the broader system of repair practices. Producers, for instance, are shown to play a dominant role in developing tools, processes, and frameworks for repair practices, but their efforts and involvement in societal transformation appear to be limited. This raises questions about whether producers are sufficiently addressing their responsibilities in influencing cultural norms and regulatory shifts. Future investigation should consider whether the tools and frameworks designed by producers are accessible and inclusive or if proprietary restrictions create barriers to repairability. Additionally, it is essential to assess the impact of legislation, such as right-to-repair laws, on producers and examine if it can encourage more active engagement in societal transformation.

Repairers, who are key in enabling repairability, are underrepresented across all dimensions, particularly in areas related to societal transformation and the development of tools and frameworks. This limited visibility implies systemic issues, such as missing institutional support. Research could explore whether repairers have the necessary skills, resources, and networks to execute and fulfil their tasks and roles effectively. Moreover, building partnerships between producers and repairers to co-develop tools and establish repair standards that reflect real-world repair needs is a promising avenue. Mechanisms to amplify the voice of repairers in cultural and policy discussions surrounding repairability also need further attention.

Users play a major role in driving societal transformation, influencing and advocating for repair practices and shaping cultural norms. However, their contributions to tools and frameworks are minimal, likely due to the technical expertise and resources required to engage in this field. Their role in bridging the gap between other stakeholders raises questions about the communication and effectiveness in facilitating meaningful interactions within the repair system. Further research should identify barriers that users face in accessing repair tools and resources, such as affordability, technical complexity, and availability, in order to improve self-repair by the users and propose strategies to address these challenges. Understanding how users’ perceptions of repairability influence their decision-making regarding repair helps to explore opportunities for education and awareness campaigns, which are key areas for exploration.

Policymakers, while primarily engaged in societal transformation through the creation of regulations, norms, and standards, have limited influence in facilitating tools and frameworks or promoting collaboration between stakeholders. This raises concerns about whether current policies properly address the practical challenges of repairability. A deeper evaluation of existing repair-related policies and their effectiveness in promoting sustainable repair systems is essential. Additionally, research should dive into how policymakers can facilitate collaboration between producers, repairers, and users through grants, public–private partnerships, or other mechanisms. Comparing global and local approaches to repair policies may also provide valuable insights into whether a unified global framework and standards for repairability are feasible.

Lastly, societal transformation towards repair practices remains largely driven by users and policymakers while producers and repairers make limited contributions. This imbalance suggests a lack of collective effort to normalise repairability as a cultural and societal value. Producers could be encouraged to promote repair discussions into corporate social responsibility initiatives. The role of repair communities, such as repair cafés, in driving cultural change also deserves closer examination, especially regarding how these groups can collaborate with producers and policymakers.

These gaps persist due to uneven engagement, differing priorities, and limited communication across stakeholder groups, which hinder coordinated and scalable repair solutions. Therefore, to advance this field, future research could examine producers through business-model analysis, repairers through field-based observation, policymakers through policy evaluation, and finally, users through behavioural and participatory research. Thus, interdisciplinary and participatory approaches can empirically validate stakeholder interactions and co-develop implementable repair strategies across design, policy, and practice.

5. Conclusions

This review highlights how service design can strengthen repair practices across micro, meso, and macro levels by connecting user experience, system efficiency, and societal transformation. Repair should be supported not only by design innovation but also by coherent policy frameworks that promote accessibility, transparency, and collaboration among stakeholders. Policymakers can leverage service design principles to co-create repair-friendly infrastructures, incentives, and regulations that align with citizens’ needs. Integrating these perspectives can accelerate the transition toward a culture of repair and circularity. Future research should test such cross-sector collaborations to ensure their practical and policy impact.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://osf.io/w4pxg/?view_only=29a6a21ba0274e909e56e1460bdc4938 (accessed on 15 October 2025), File S1: PRISMA & Key Categories (Excel spreadsheet); File S2: PRISMA 2020 Checklist (Word document).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.A., L.S. and L.N.L.; methodology, V.A., L.S. and L.N.L.; software, V.A.; validation, V.A., L.S. and L.N.L.; formal analysis, V.A. and L.S.; investigation, V.A. and L.S.; resources, V.A. and L.S.; data curation, V.A.; writing—original draft preparation, V.A., L.S. and L.N.L.; writing—review and editing, V.A., L.S. and L.N.L.; visualisation, V.A.; supervision, L.S. and L.N.L.; project administration, V.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are openly available in the OSF repository at https://osf.io/w4pxg/?view_only=29a6a21ba0274e909e56e1460bdc4938 (accessed on 15 October 2025). These materials include the dataset “PRISMA & Key Categories from Literature Review,” which contain the search strategy, coding framework, and extracted data used in the analysis, and the PRISMA 2020 checklist.

Acknowledgments

A previous, preliminary and incomplete version of this review was presented at the PLATE conference (Aalborg, Denmark) in July 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Van Dam, K.; Simeone, L.; Keskin, D.; Baldassarre, B.; Niero, M.; Morelli, N. Circular Economy in Industrial Design Research: A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrad, M.; Semaan, R.W.; Christodoulides, G.; Prandelli, E. Give Me a Second Life! Extending the Life-Span of Luxury Products through Repair. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 82, 104055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frahm, L.B.; Boks, C.; Laursen, L.N. It’s Intertwined! Barriers and Motivations for Second-Hand Product Consumption. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2024, 5, 653–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, C.; Wang, F.; Huisman, J.; Den Hollander, M. Products That Go Round: Exploring Product Life Extension through Design. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 69, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keulemans, G.; Jansen, T.; Cahill, L. Luxury and Scarcity: Exploring Anachronisms in the Market for Transformative Repair. In Design/Repair; Kalantidou, E., Keulemans, G., Mellick Lopes, A., Rubenis, N., Gill, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 41–64. ISBN 978-3-031-46861-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kalantidou, E.; Keulemans, G.; Mellick Lopes, A.; Rubenis, N.; Gill, A. Introduction. In Design/Repair; Kalantidou, E., Keulemans, G., Mellick Lopes, A., Rubenis, N., Gill, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–10. ISBN 978-3-031-46861-2. [Google Scholar]

- De Fazio, F.; Bakker, C.; Flipsen, B.; Balkenende, R. The Disassembly Map: A New Method to Enhance Design for Product Repairability. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 320, 128552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amend, C.; Revellio, F.; Tenner, I.; Schaltegger, S. The Potential of Modular Product Design on Repair Behavior and User Experience–Evidence from the Smartphone Industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 367, 132770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Velden, M. ‘Fixing the World One Thing at a Time’: Community Repair and a Sustainable Circular Economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 304, 127151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantidou, E.; Keulemans, G.; Mellick Lopes, A.; Rubenis, N.; Gill, A. Roundtable: A Discussion About Design/Repair. In Design/Repair; Kalantidou, E., Keulemans, G., Mellick Lopes, A., Rubenis, N., Gill, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 265–295. ISBN 978-3-031-46861-2. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelmeguid, A.; Afy-Shararah, M.; Salonitis, K. Towards Circular Fashion: Management Strategies Promoting Circular Behaviour along the Value Chain. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 48, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolf, S.; Blömeke, S.; Niemeyer, J.F.; Lawrenz, S.; Sharma, P.; Hemminghaus, S.; Mennenga, M.; Schmidt, K.; Rausch, A.; Spengler, T.S.; et al. Extending the Life Cycle of EEE—Findings from a Repair Study in Germany: Repair Challenges and Recommendations for Action. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munten, P.; Vanhamme, J. To Reduce Waste, Have It Repaired! The Quality Signaling Effect of Product Repairability. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 156, 113457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luukkonen, R.; Van Den Broek, K.L. Exploring the Drivers behind Visiting Repair Cafés: Insights from Mental Models. Clean. Prod. Lett. 2024, 7, 100070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, D.M.; Price, L.L.; Lusch, R.F. Repair, Consumption, and Sustainability: Fixing Fragile Objects and Maintaining Consumer Practices. J. Consum. Res. 2022, 49, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, V.; Stead, M.; Coulton, P. Fostering IoT Repair Through Care: Learning from Emotional Durable Gaming Practices and Communities. In Proceedings of the Designing Interactive Systems Conference, Copenhagen Denmark, 1–5 July 2024; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 102–105. [Google Scholar]

- Rubenis, N. From Roadside Detritus to Communities Painting Pet Portraits: Some Things I Have Learnt About Repair. In Design/Repair; Kalantidou, E., Keulemans, G., Mellick Lopes, A., Rubenis, N., Gill, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 241–262. ISBN 978-3-031-46861-2. [Google Scholar]

- Penin, L. An Introduction to Service Design; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Polaine, A.; Løvlie, L.; Reason, B. Service Design: From Insight to Implementation; Rosenfeld Media, LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tukker, A. Product Services for a Resource-Efficient and Circular Economy—A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 97, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceschin, F.; Gaziulusoy, I. Evolution of Design for Sustainability: From Product Design to Design for System Innovations and Transitions. Des. Stud. 2016, 47, 118–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, N.; De Götzen, A.; Simeone, L. Service Design Capabilities; Springer Series in Design and Innovation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 10, ISBN 978-3-030-56281-6. [Google Scholar]

- Papanek, V.J. Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1971; ISBN 978-0-394-47036-8. [Google Scholar]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pati, D.; Lorusso, L.N. How to Write a Systematic Review of the Literature. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2018, 11, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, H.A.M.; Andersen, P.H.; De Boer, L. Stakeholder Collaboration in Sustainable Neighborhood Projects—A Review and Research Agenda. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 68, 102776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, I. Qualitative Data Analysis: A User Friendly Guide for Social Scientists; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2003; ISBN 978-0-203-41249-7. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The Qualitative Content Analysis Process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, C.; Gnanapragasam, A. Community Repair: Enabling Repair as Part of the Movement Towards a Circular Economy; Nottingham Trent University: Nottingham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson-Hoglund, S.; Richter, J.L.; Maitre-Ekern, E.; Russell, J.D.; Pihlajarinne, T.; Dalhammar, C. Barriers, Enablers and Market Governance: A Review of the Policy Landscape for Repair of Consumer Electronics in the EU and the U.S. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 288, 125488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, R.; Inês, A.; Dalmarco, G.; Moreira, A.C. The Role of Consumers in the Adoption of R-Strategies: A Review and Research Agenda. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2024, 13, 100193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fachbach, I.; Lechner, G.; Reimann, M. Drivers of the Consumers’ Intention to Use Repair Services, Repair Networks and to Self-Repair. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 346, 130969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzioğlu, N. Repair Motivation and Barriers Model: Investigating User Perspectives Related to Product Repair towards a Circular Economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 289, 125644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arredondo-Soto, K.C.; Jiménez-Zaragoza, A.; Miranda-Ackerman, M.A.; Blanco-Fernández, J.; García-Lechuga, A.; Hernández-Escobedo, G.; García-Alcaraz, J.L. Design and Repair Strategies Based on Product–Service System and Remanufacturing for Value Preservation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, D.M.; Price, L.L. How an Ethos of Repair Shapes Material Sustainability in Services. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2023, 53, 439–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, L.; Mugge, R.; Schoormans, J. Consumers’ Perspective on Product Care: An Exploratory Study of Motivators, Ability Factors, and Triggers. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjorth Nielsen, A.S.A.; Laursen, L.N. Love at first sight: Immediate emotional attachment of volunteers in repair cafés. In Proceedings of the 5th PLATE Conference, Espoo, Finland, 31 May–2 June 2023; Aalto University School of Art & Design: Helsinki, Finland, 2023; pp. 417–423, ISBN 978-952-64-1367-9. [Google Scholar]

- Maestri, L.; Wakkary, R. Understanding Repair as a Creative Process of Everyday Design. In Proceedings of the 8th ACM Conference on Creativity and Cognition, Atlanta, GA, USA, 3 November 2011; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Roskladka, N.; Bressanelli, G.; Miragliotta, G.; Saccani, N. A Review on Design for Repair Practices and Product Information Management. In Advances in Production Management Systems. Production Management Systems for Responsible Manufacturing, Service, and Logistics Futures; Alfnes, E., Romsdal, A., Strandhagen, J.O., Von Cieminski, G., Romero, D., Eds.; IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 692, pp. 319–334. ISBN 978-3-031-43687-1. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger-Erben, M.; Frick, V.; Hipp, T. Why Do Users (Not) Repair Their Devices? A Study of the Predictors of Repair Practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 286, 125382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roskladka, N.; Jaegler, A.; Miragliotta, G. From “Right to Repair” to “Willingness to Repair”: Exploring Consumer’s Perspective to Product Lifecycle Extension. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 432, 139705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masclet, C.; Mazudie, J.L.; Boujut, J.-F. Barriers and opportunities to repair in repair cafes. Proc. Des. Soc. 2023, 3, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, L.S.; Hamlin, R.P.; McQueen, R.H.; Degenstein, L.; Garrett, T.C.; Dunn, L.; Wakes, S. Fashion Sensitive Young Consumers and Fashion Garment Repair: Emotional Connections to Garments as a Sustainability Strategy. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, P.; Vainio, A.; Viholainen, N.; Korsunova, A. Consumers and Self-Repair: What Do They Repair, What Skills Do They Have and What Are They Willing to Learn? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 206, 107647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, N.F.; Jaeger-Erben, M. Product Lifetimes and the Environment. In Proceedings of the 3rd PLATE Conference, Berlin, Germany, 18–20 September 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callén Moreu, B.; Duque Hurtado, M. “We Not Only Repair Our Devices, But Also Our Relationship with Them”: Repair-Led Designing at the Restart Parties in Barcelona. In Design/Repair; Kalantidou, E., Keulemans, G., Mellick Lopes, A., Rubenis, N., Gill, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 91–120. ISBN 978-3-031-46861-2. [Google Scholar]

- Rosner, D.K.; Jackson, S.J.; Hertz, G.; Houston, L.; Rangaswamy, N. Reclaiming Repair: Maintenance and Mending as Methods for Design. In Proceedings of the CHI ’13 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Paris, France, 27 April 2013; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 3311–3314. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, H.; Roy, R.; Seliger, G. Industrial Product-Service Systems—IPS 2. CIRP Ann. 2010, 59, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, T.S.; Lightfoot, H.W.; Benedettini, O.; Kay, J.M. The Servitization of Manufacturing: A Review of Literature and Reflection on Future Challenges. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2009, 20, 547–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, L. Design for Product Care—Development of Design Strategies and a Toolkit for Sustainable Consumer Behaviour. J. Sustain. Res. 2021, 3, e210013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjorth Nielsen, A.S.A.; Laursen, L.N.; Tollestrup, C. Can you fix it? An investigation of critical repair steps and barriers across product types. In Proceedings of the 5th PLATE Conference, Espoo, Finland, 31 May–2 June 2023; Niinimäki, K., Cura, K., Eds.; Aalto University: Helsinki, Finland, 2023. ISBN 978-952-64-1367-9. [Google Scholar]

- Lechner, G.; Kraßnig, V.; Güsser-Fachbach, I. How Can Repair Businesses Improve Their Service? Consumer Priorities Concerning Operational Aspects of Repair Services. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 204, 107501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadha, C.; James, K.; Jasiuk, I.M.; Patterson, A.E. Patterson Extending the Operating Life of Thermoplastic Components via On-Demand Patching and Repair Using Fused Filament Fabrication. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2022, 6, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellick Lopes, A.; Gill, A. Commoning Repair: Framing a Community Response to Transitioning Waste Economies. In Design/Repair; Kalantidou, E., Keulemans, G., Mellick Lopes, A., Rubenis, N., Gill, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 183–212. ISBN 978-3-031-46861-2. [Google Scholar]

- Neely, A. Exploring the Financial Consequences of the Servitization of Manufacturing. Oper. Manag. Res. 2008, 1, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okorie, O.; Salonitis, K.; Charnley, F.; Turner, C. A Systems Dynamics Enabled Real-Time Efficiency for Fuel Cell Data-Driven Remanufacturing. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2018, 2, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, G.B.; Soylu, B. A Multiobjective Post-Sales Guarantee and Repair Services Network Design Problem. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 216, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbaghi, M.; Behdad, S. Design for Repair: A Game Between Manufacturer and Independent Repair Service Provider. In Proceedings of the Volume 2A: 43rd Design Automation Conference, Cleveland, OH, USA, 6 August 2017; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2017; p. V02AT03A037. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, B.C.; Adams, W.P. An Evaluation of Service and Repair Manual Design. SAE Trans. 1988, 97, 881329. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G.; Cao, Z.; Xu, Q. A Simple Location-Allocation Model on Reverse Logistics for Repair Service System Design. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Operations and Supply Chain Management in China (ICOSCM 2007), Bangkok, Thailand, 18–20 May 2007; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Siswantoro, N.; Prastowo, H.; Nugroho, H.R.; Zaman, M.B.; Pitana, T.; Priyanta, D. A Preliminary Web-Based Intermediary Application Design for Ship Repair Planning Services; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2022; Volume 1081. [Google Scholar]

- Rossihina, L.V.; Kalach, A.V.; Akulov, A.Y.; Sysoeva, T.P.; Kravchenko, A.S. Algorithm Design for Optimization of Service Requests for Repair. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 548, 032004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güsser-Fachbach, I.; Lechner, G.; Ramos, T.B.; Reimann, M. Repair Service Convenience in a Circular Economy: The Perspective of Customers and Repair Companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 415, 137763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, D.; Sailaja, N. User-Centred Repair: From Current Practices to Future Design. In Distributed, Ambient and Pervasive Interactions; Streitz, N.A., Konomi, S., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 14718, pp. 52–71. ISBN 978-3-031-59987-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kodhelaj, I.; Chituc, C.-M.; Beunders, E.; Janssen, D. Designing and Deploying a Business Process for Product Recovery and Repair at a Servicing Organization: A Case Study and Framework Proposal. Comput. Ind. 2019, 105, 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, M.; Retzlaff-Roberts, D.; Bienstock, C. Designing a Reverse Logistics Operation for Short Cycle Time Repair Services. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2005, 96, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tursunovic, R.S. Improvement of Operational and Repair Technology of Machine Design in Technical Service by Developing Innovative Constructive Technical Solutions; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; Volume 519. [Google Scholar]

- Rappold, J.A.; Van Roo, B.D. Designing Multi-Echelon Service Parts Networks with Finite Repair Capacity. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2009, 199, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, O.B.; Robinson, T.W.; Theriot, E.J. Automated Repair Service Bureau: Mechanized Loop Testing Design. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1982, 61, 1235–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, G.H.; Zielinski, J.E. Automated Repair Service Bureau: Human Performance Design Techniques. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1982, 61, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, R.F.; Harris, W.A. Automated Repair Service Bureau: Two Examples of Human Performance Analysis and Design in Planning the ARSB. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1982, 61, 1301–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.-C.; Chan, H.-C.; Chen, C.-H. Establishing Circular Model and Management Benefits of Enterprise from the Circular Economy Standpoint: A Case Study of Chyhjiun Jewelry in Taiwan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivastri, C.; Tagliasco, G. Servizi per Il Riuso e Il Riparo. L’allestimento Tra Touchpoints e Infrastrutture Relazionali|Services for Reuse and Repair. The Arrangement Between Touchpoints and Relational Infrastructures. Agathón 2024, 15, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukker, A.; Tischner, U. Product-Services as a Research Field: Past, Present and Future. Reflections from a Decade of Research. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 1552–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajuly, K.; Green, J.; Richter, J.; Johnson, M.; Rückschloss, J.; Peeters, J.; Kuehr, R.; Fitzpatrick, C. Product Repair in a Circular Economy: Exploring Public Repair Behavior from a Systems Perspective. J. Ind. Ecol. 2024, 28, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mont, O.K. Clarifying the Concept of Product–Service System. J. Clean. Prod. 2002, 10, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipnis, V.A. Evolving Issues in Product Life Cycle Design. (How to Design Products That Are Environmentally Safe to Manufacture/Assemble, Distribute, Use, Service/Repair, Discard/Collect, Disassemble, Recycle/Recover, and Dispose?). CIRP Ann.—Manuf. Technol. 1993, 42, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, L.; Sanderson, J. Design-Led Repair: Insights, Anecdotes and Reflections from Australian Repairers. In Design/Repair; Kalantidou, E., Keulemans, G., Mellick Lopes, A., Rubenis, N., Gill, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 67–90. ISBN 978-3-031-46861-2. [Google Scholar]

- Beulque, R.; Micheaux, H.; Ntsondé, J.; Aggeri, F.; Steux, C. Sufficiency-Based Circular Business Models: An Established Retailers’ Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 429, 139431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.T.; Coeckelbergh, M. Maintenance and Philosophy of Technology: Keeping Things Going, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2024; ISBN 978-1-003-31621-3. [Google Scholar]

- Özkan, N.; Wever, R. Integrating Repair into Product Design Education: Insights on Repair, Design and Sustainability. In Proceedings of the Insider Knowledge—Proceedings of the Design Research Society Learn X Design Conference, Ankara, Turkey, 9 July 2019; Design Research Society: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lloveras, J.; Pansera, M.; Smith, A. On ‘the Politics of Repair Beyond Repair’: Radical Democracy and the Right to Repair Movement. J. Bus. Ethics 2024, 196, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, K.; Svejkar, D.; Tonkinwise, C. Relational Repair: Co-Designing an Approach to Place-Based Circularity with an Ethic of Care. In Design/Repair; Kalantidou, E., Keulemans, G., Mellick Lopes, A., Rubenis, N., Gill, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 149–180. ISBN 978-3-031-46861-2. [Google Scholar]

- Adams Stein, J. Conflicting Interpretations of ‘Design’ and ‘Premature Product Obsolescence’: Australia’s Right to Repair Inquiry 2020–2021. In Design/Repair; Kalantidou, E., Keulemans, G., Mellick Lopes, A., Rubenis, N., Gill, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 13–39. ISBN 978-3-031-46861-2. [Google Scholar]

- Skare, M.; Gavurova, B.; Rigelsky, M. Income Inequality and Circular Materials Use: An Analysis of European Union Economies and Implications for Circular Economy Development. Manag. Decis. 2024, 62, 2641–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantidou, E.; Brennan, T. Community Resilience by Repair: Skilling At-Risk Youth for Social Impact and Environmental Sustainability. In Design/Repair; Kalantidou, E., Keulemans, G., Mellick Lopes, A., Rubenis, N., Gill, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 213–240. ISBN 978-3-031-46861-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, R.J.; Miranda, C.; Goñi, J. Empowering Sustainable Consumption by Giving Back to Consumers the ‘Right to Repair’. Sustainability 2020, 12, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayraktaroğlu, S.; İdemen, E. Redefining Repair as a Value Co-Creation Process for Circular Economy: Facilitated Do-It-Yourself Repair. Int. J. Des. 2024, 18, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).